User login

Treatment of Acne Keloidalis Nuchae in a Southern California Population

Treatment of Acne Keloidalis Nuchae in a Southern California Population

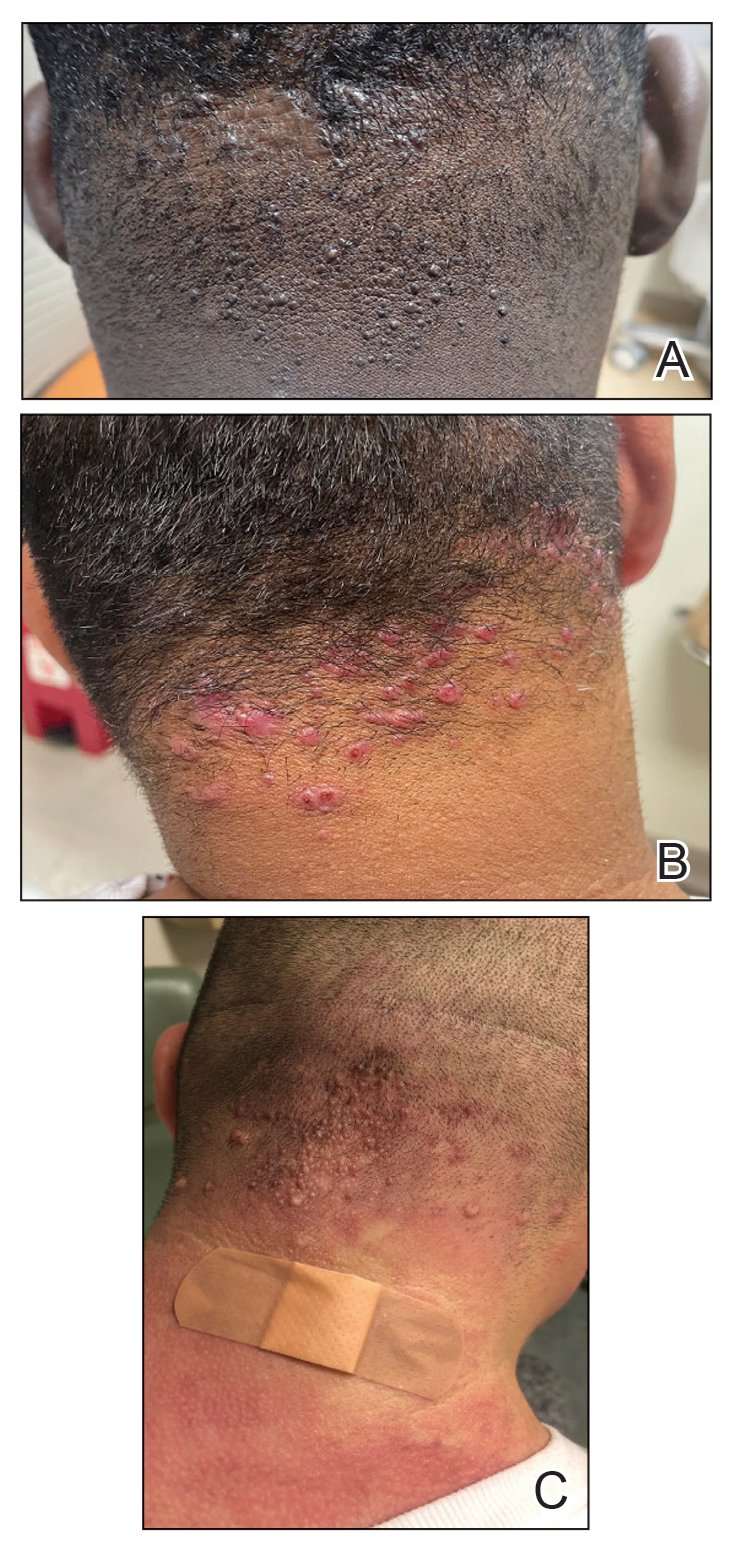

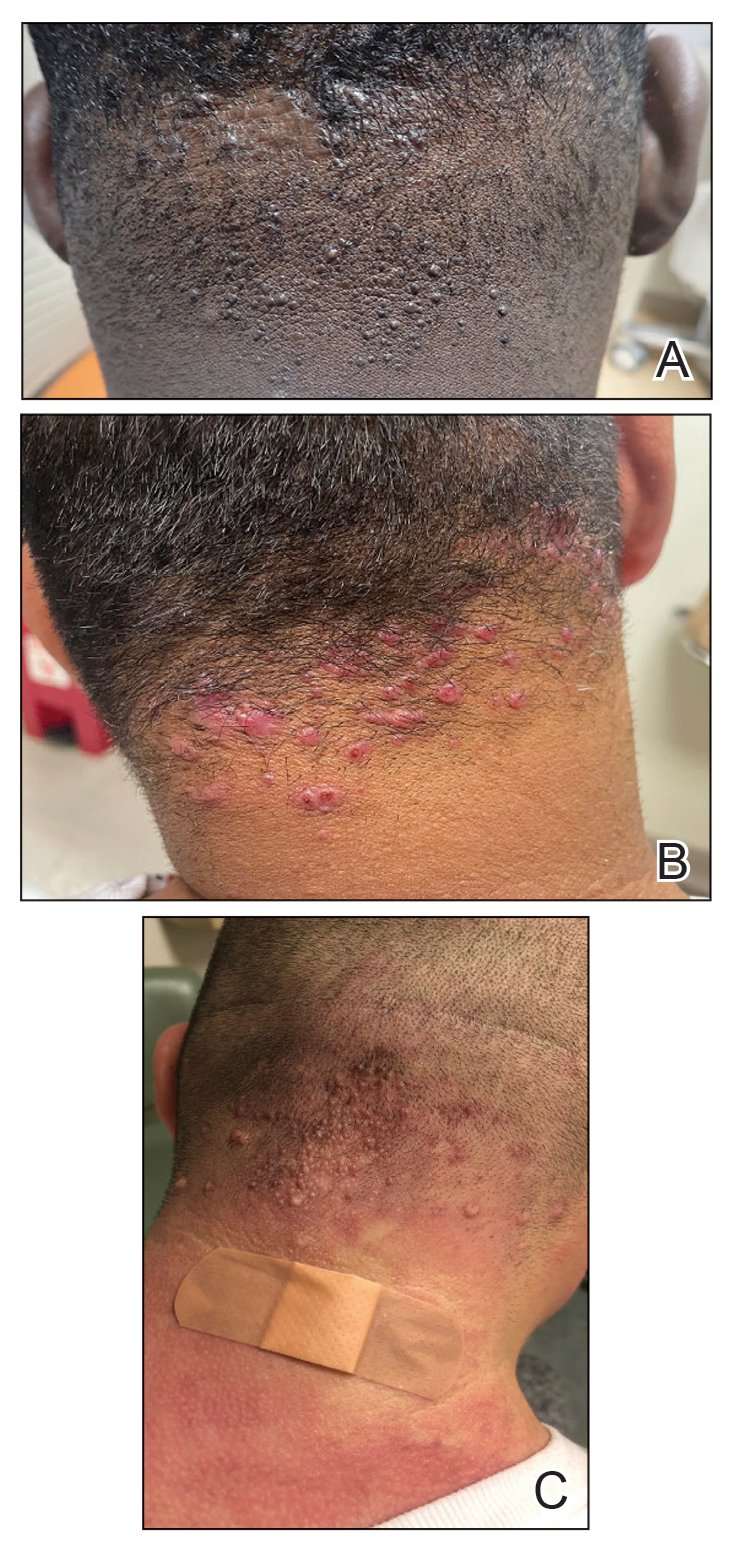

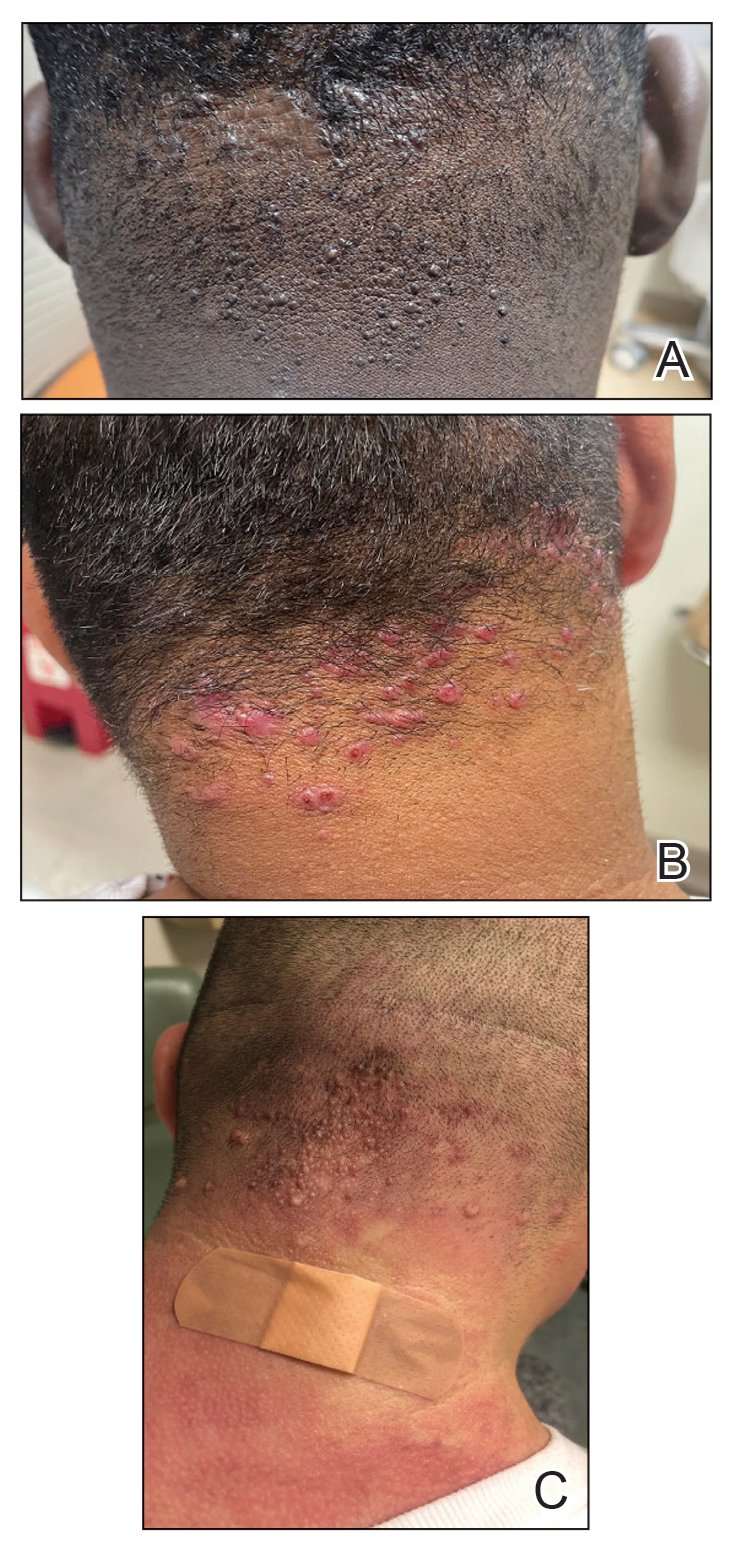

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) classically presents as chronic inflammation of the hair follicles on the occipital scalp/nape of the neck manifesting as papules and pustules that may progress to keloidlike scarring.1 Photographs depicting the typical clinical presentation of AKN are shown in the Figure. In the literature, AKN has been described as primarily occurring in postpubertal males of African descent.2 Despite its similar name, AKN is not related to acne vulgaris.3 The underlying cause of AKN is hypothesized to be multifactorial, including inflammation, infection, and trauma.2 Acne keloidalis nuchae is most common in males aged 14 to 50 years, which may indicate that increased androgens contribute to its development.3 In some cases, patients have reported developing AKN lesions after receiving a haircut or shaving, suggesting a potential role of trauma to the hair follicles and secondary infection.2 Histopathology typically shows a perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate that obscures the hair follicles with associated proximal fibrosis.4 On physical examination, dermoscopy can be used to visualize perifollicular pustules and fibrosis, which appears white, in the early stages of AKN. Patients may present with tufted hairs in more advanced stages.5 Patients with AKN often describe the lesions as pruritic and painful.2

In this study, we evaluated the most common treatment regimens used over a 6-year period by patients in the Los Angeles County hospital system in California and their efficacy on AKN lesions. Our study includes one of the largest cohorts of patients reported to date and as such demonstrates the real-world effects that current treatment regimens for AKN have on patient outcomes nationwide.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of patient medical records from the Los Angeles County hospital system i2b2 (i2b2 tranSMART Foundation) clinical data warehouse over a 6-year period (January 2017–January 2023). We used the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes L73.0 (acne keloid) and L73.1 (pseudofolliculitis barbae) to conduct our search in order to identify as many patients with follicular disorders as possible to include in the study. Of the 478 total medical records we reviewed, 183 patients were included based on a diagnosis of AKN by a dermatologist.

We then collected data on patient demographics and treatments received, including whether patients had received monotherapy or combination therapy. Of the 183 patients we initially identified, 4 were excluded from the study because they had not received any treatment, and 78 were excluded because no treatment outcomes were documented. The 101 patients who were included had received either monotherapy or a combination of treatments. Treatment outcomes were categorized as either improvement in the number and appearance of papules and/or keloidlike plaques, maintenance of stable lesions (ie, well controlled), and/or resolution of lesions as documented by the treating physician. No patients had overall worsening of their disease.

Results

Of the 101 patients included in the study, 34 (33.7%) received a combination of topical, systemic, and procedural treatments; 34 (33.7%) received a combination of topical and procedural treatments; 17 (16.8%) were treated with topicals only; 13 (12.9%) were treated with a combination of topical and systemic treatments; and 3 (3.0%) were treated with monotherapy of either a topical, systemic, or procedural therapy. Systemic and/or procedural therapy combined with topicals was provided as a first-line treatment for 63 (62.4%) patients. Treatment escalation to systemic or procedural therapy for those who did not respond to topical treatment was observed in 23 (22.8%) patients. The average number of unique treatments received per patient was 3.67.

Clindamycin and clobetasol were the most prescribed topical treatments, doxycycline was the most prescribed systemic therapy, and intralesional (IL) triamcinolone was the most performed procedural therapy. The most common treatment regimens were topical clindamycin and clobetasol, topical clindamycin and clobetasol with IL triamcinolone, and topical clindamycin and clobetasol with both IL triamcinolone and doxycycline.

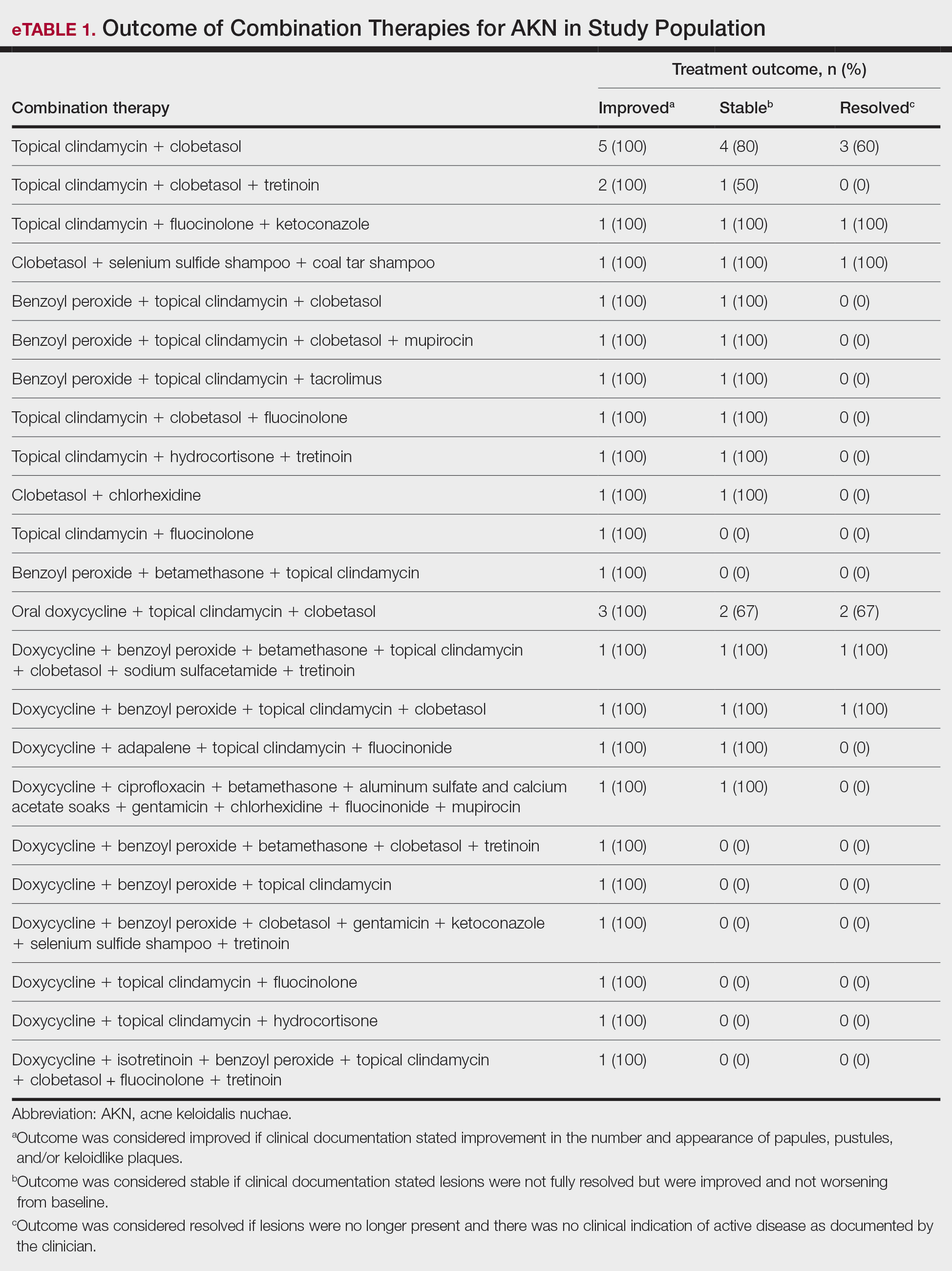

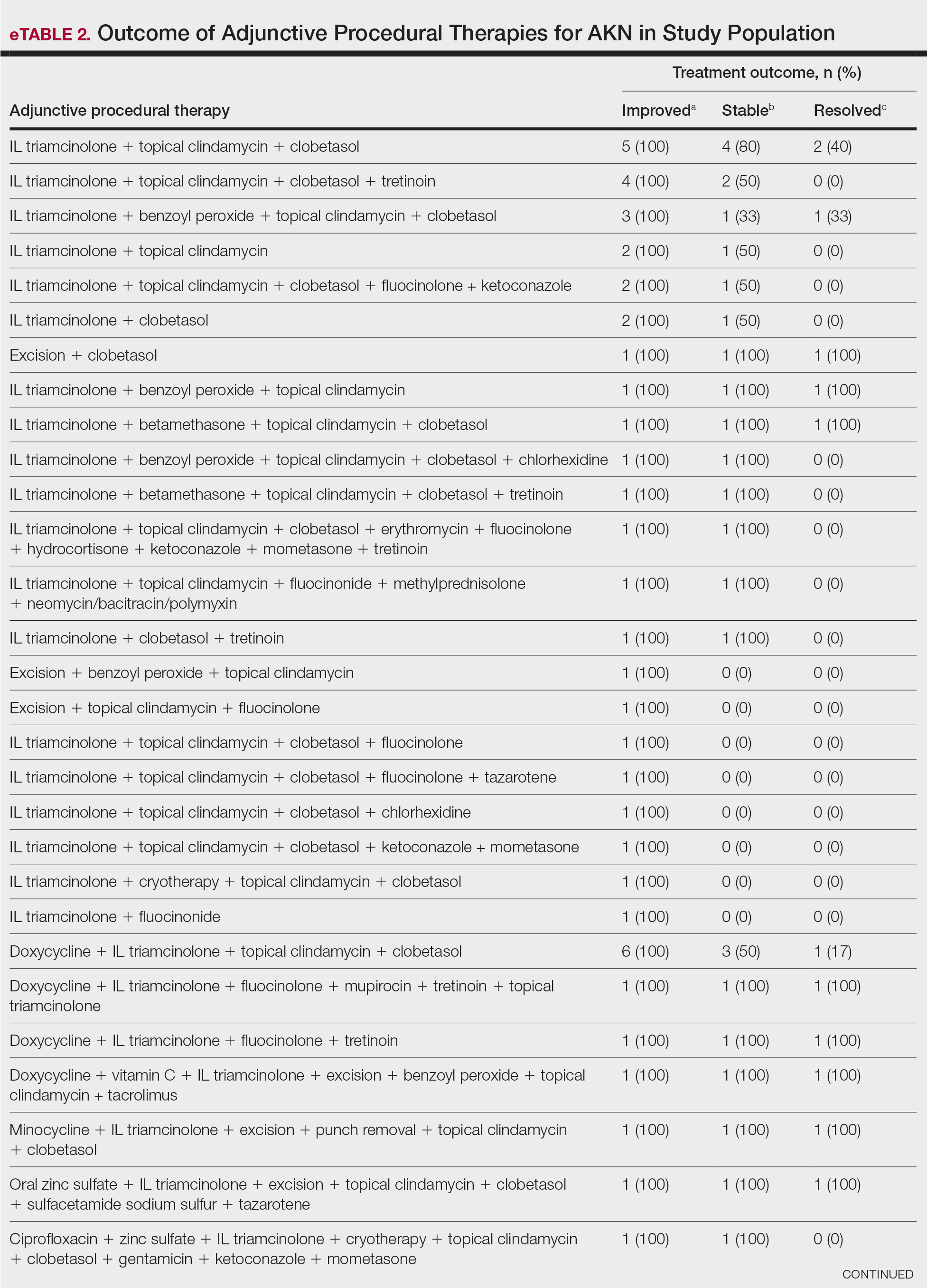

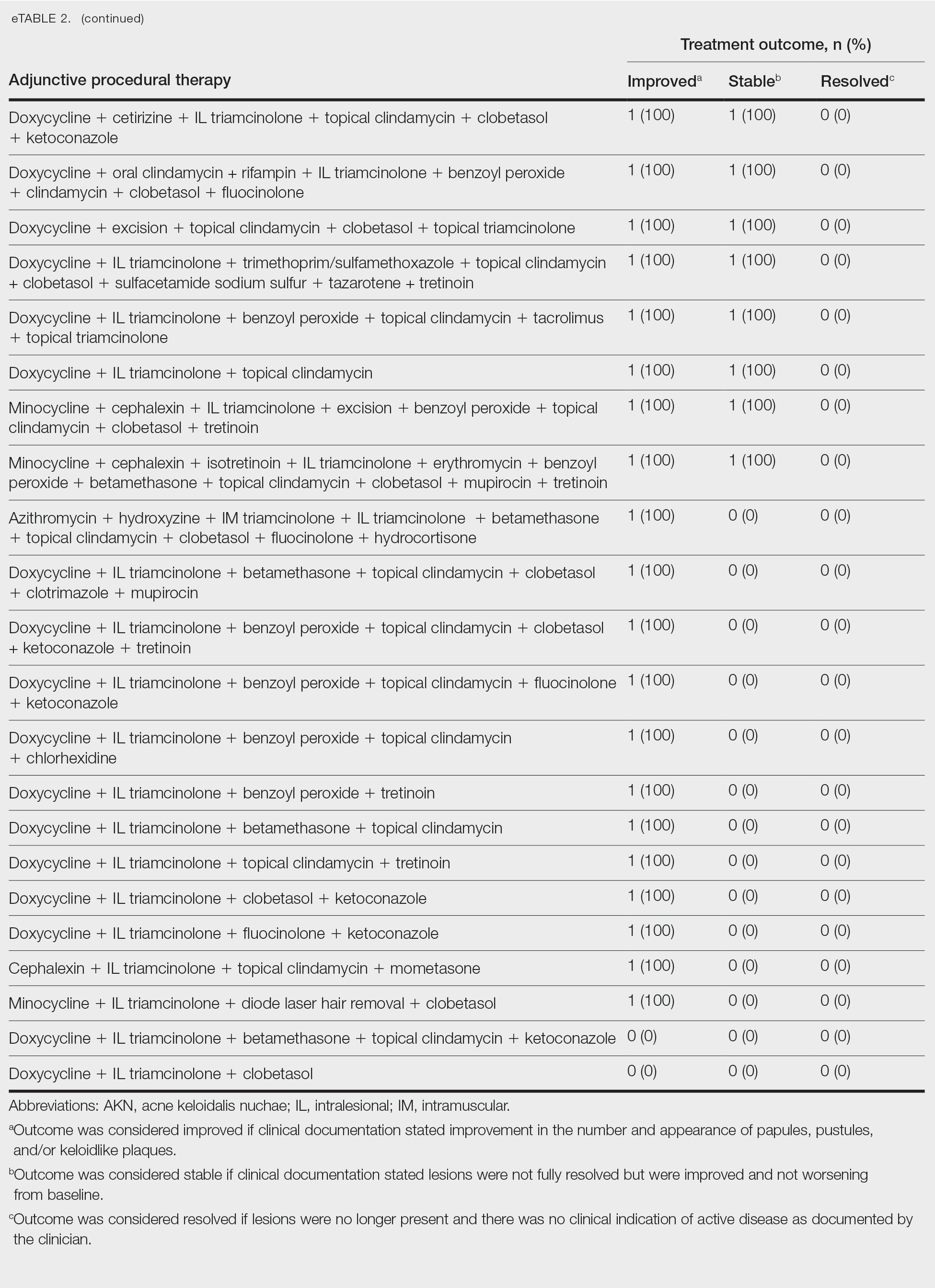

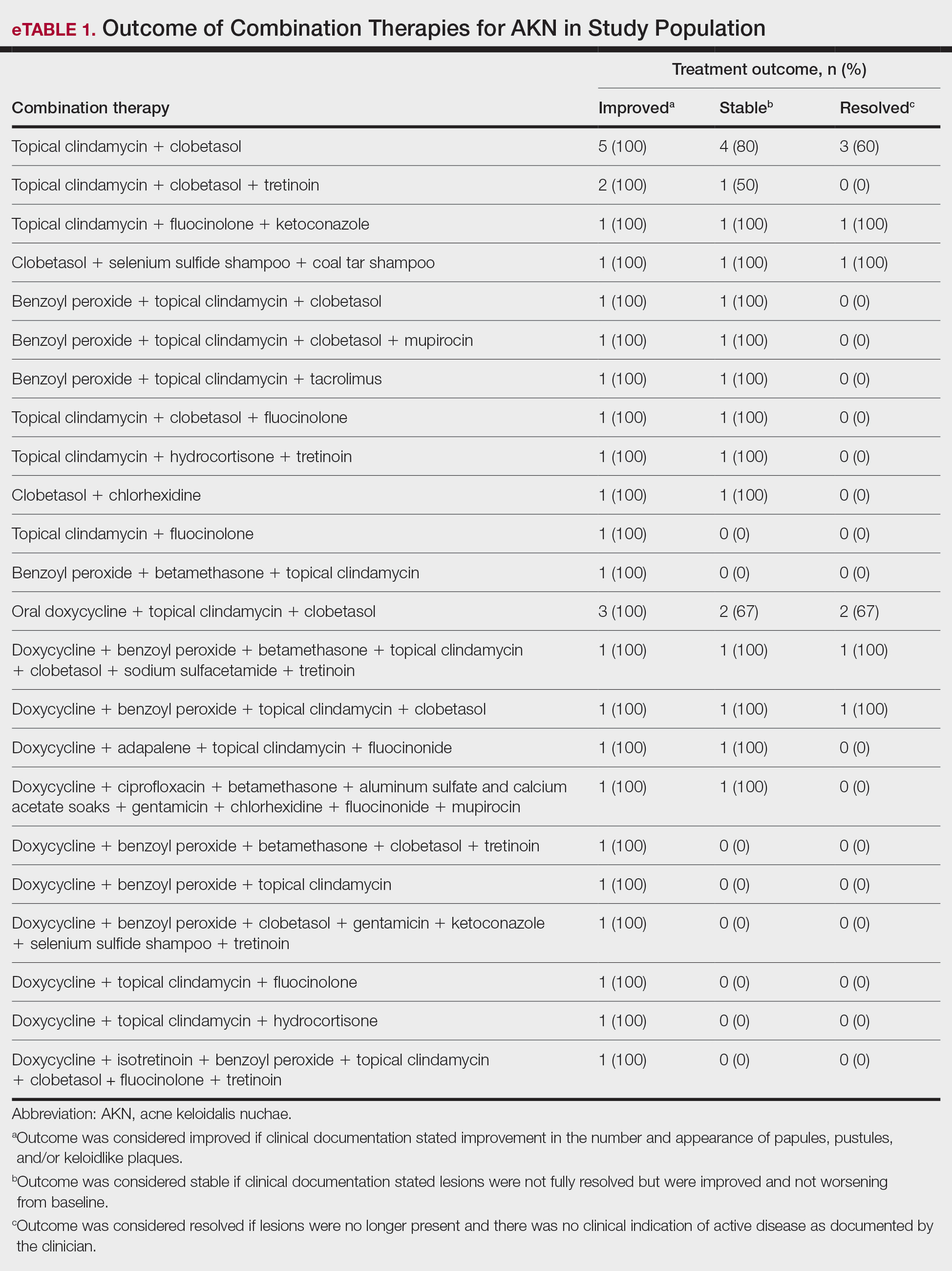

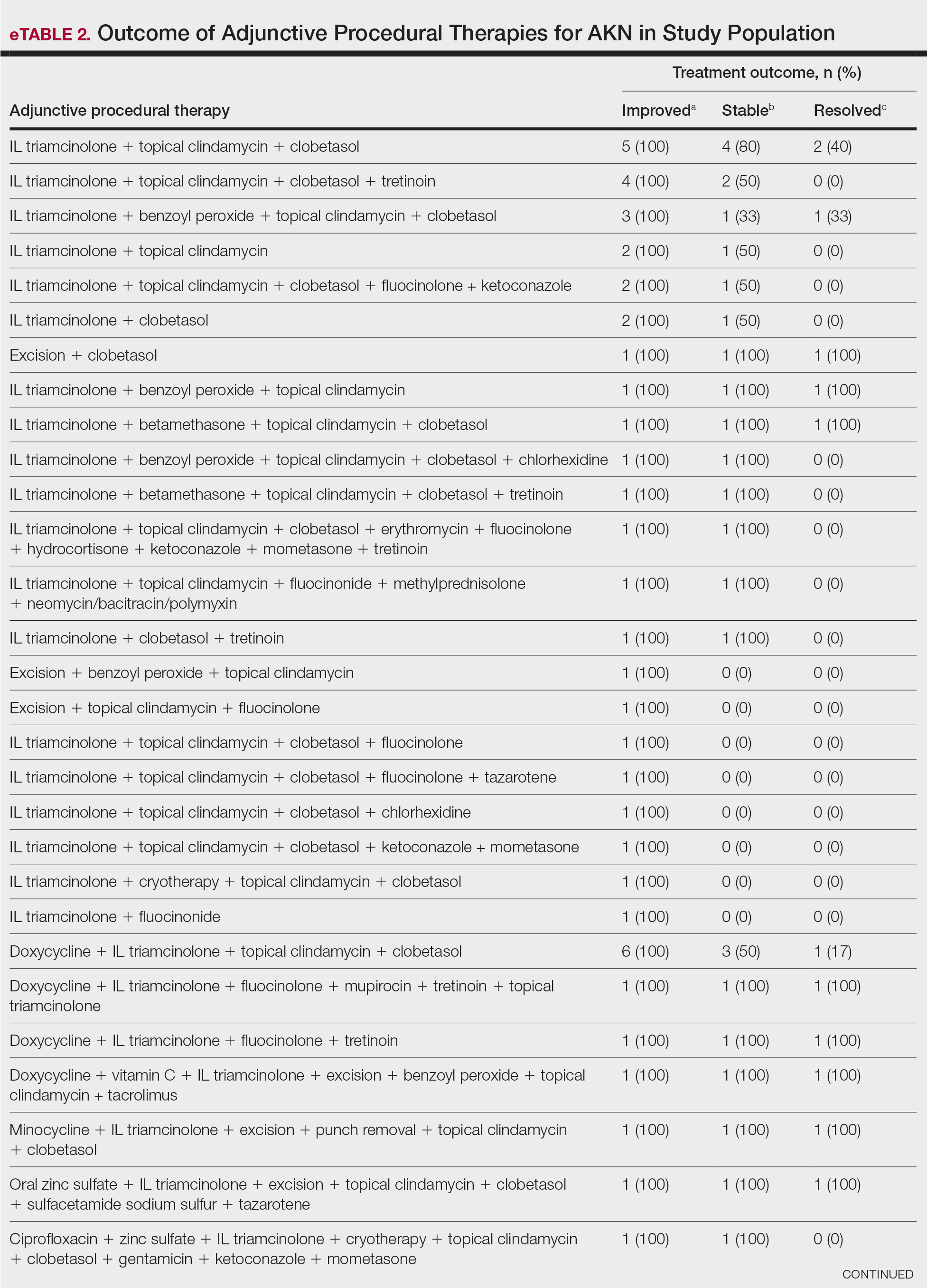

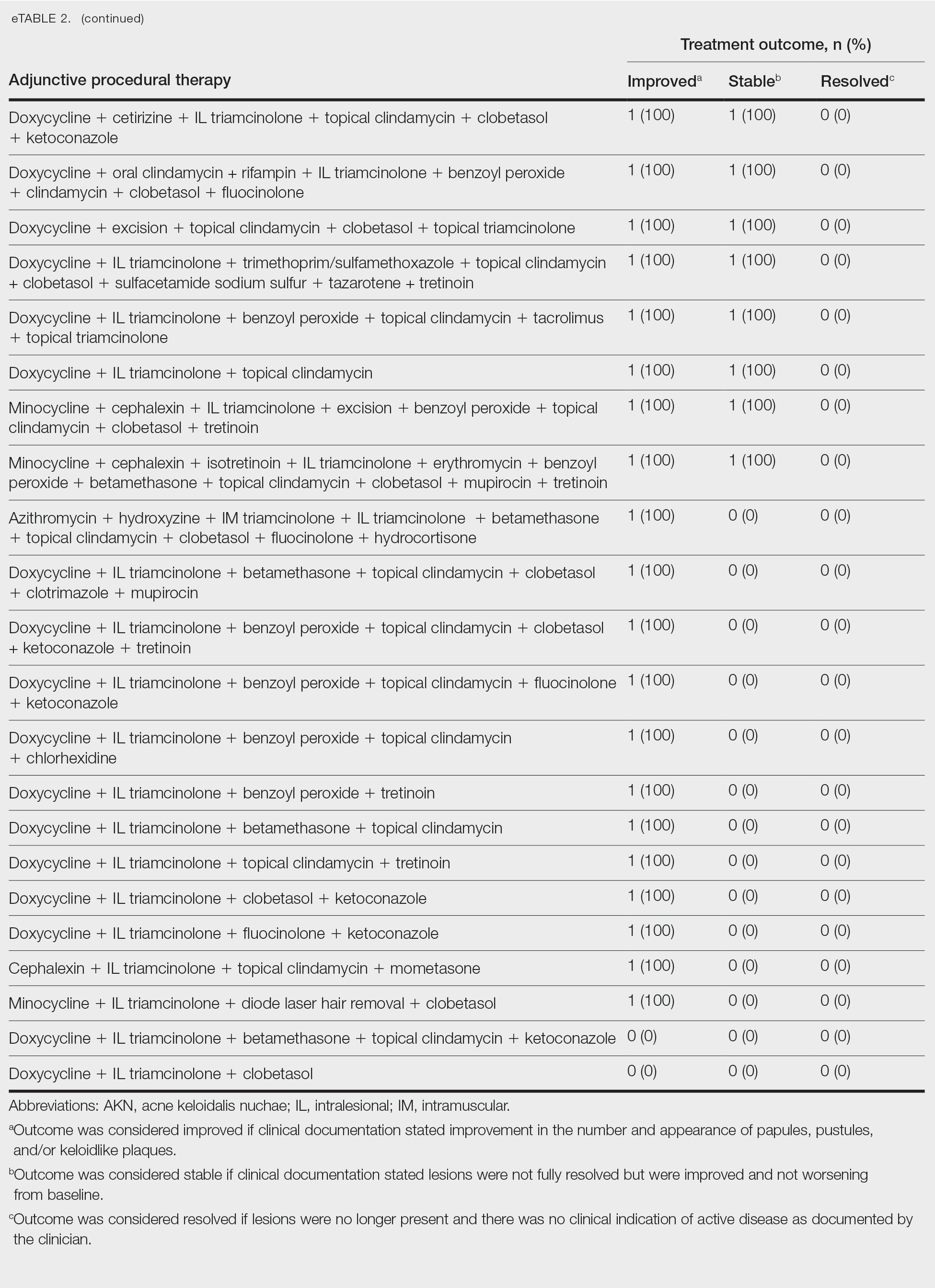

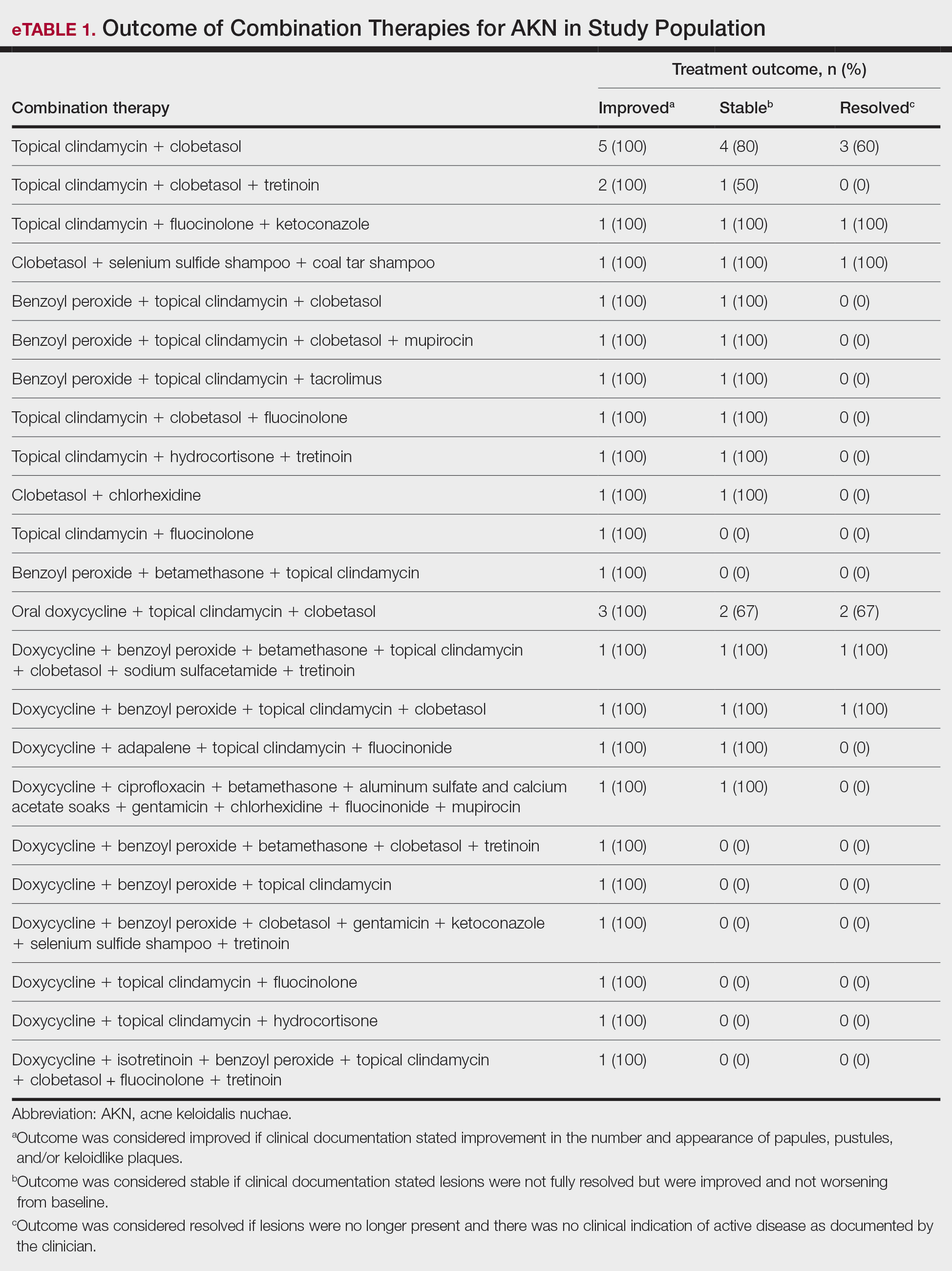

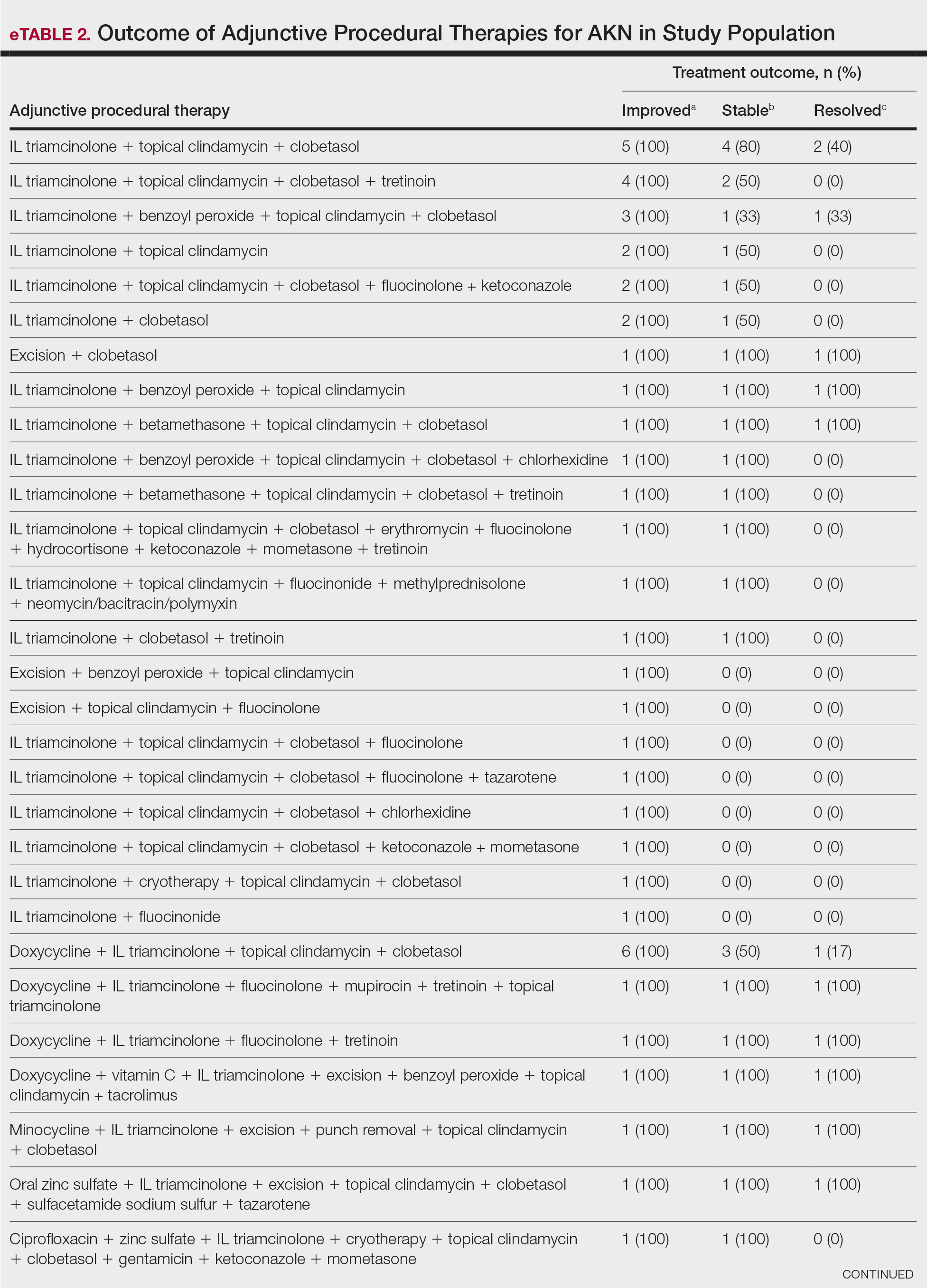

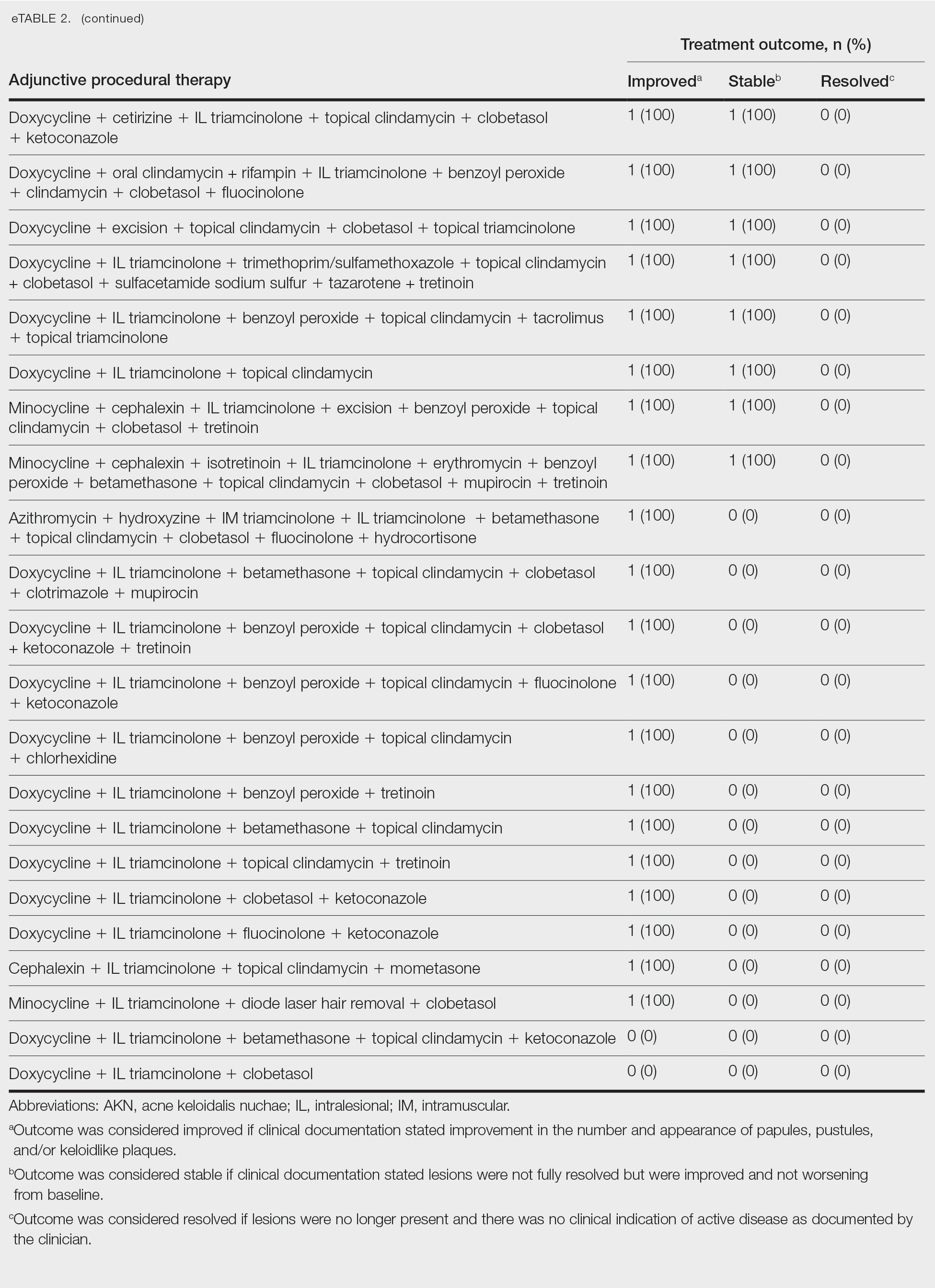

Improvement in AKN lesions was reported for the majority of patients with known treatment outcomes across all types of regimens. Ninety-eight percent (99/101) of patients had improvement in lesions, 55.5% (56/101) had well-controlled lesions, and 20.8% (21/101) achieved resolution of disease. The treatment outcomes are outlined in eTables 1 and 2.

Comment

Most clinicians opted for a multitherapy treatment regimen, and improvement was noted in most patients regardless of which regimen was chosen. As expected, patients who had mild or early disease generally received topical agents first, including most commonly a mid- to high-potency steroid, antibiotic, retinoid, and/or antifungal; specifically, clindamycin, clobetasol, and fluocinolone were the most common agents chosen. Patients with severe disease were more likely to receive systemic and/or procedural treatments, including oral antibiotics or IL steroid injections most commonly. Improvement was documented in the majority of patients using these treatment regimens, and some patients did achieve full resolution of disease.

Our data cannot be used to determine which treatment alone is most effective for patients with AKN, as the patients in our study had varying levels of disease activity and types of lesions, and most received combination therapy. What our data do show is that combination therapies often work well to control or improve disease, but also that current therapeutic options only rarely lead to full resolution of disease.

Limitations of our study included an inability to stratify disease, an inability to rigorously analyze specific treatment outcomes since most patients did not receive monotherapy. The strength of our study is its size, which allows us to show that many different treatment regimens currently are being employed by dermatologists to treat AKN, and most of these seem to be somewhat effective.

Conclusion

Acne keloidalis nuchae is difficult to treat due to a lack of understanding of which pathophysiologic mechanisms dominate in any given patient, a lack of good data on treatment outcomes, and the variability of ways that the disease manifests. Thus far, as shown by the patients described in this study, the most efficacious treatment regimens seem to be combination therapies that target the multifactorial causes of this disease. Physicians should continue to choose treatments based on disease severity and cutaneous manifestations, tailor their approach by accounting for patient preferences, and consider a multimodal approach to treatment.

- Maranda EL, Simmons BJ, Nguyen AH, et al. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae: a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:363-378. doi:10.1007/s13555-016-0134-5<

- Ogunbiyi A, Adedokun B. Perceived aetiological factors of folliculitis keloidalis nuchae (acne keloidalis) and treatment options among Nigerian men. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(Suppl 2):22-25. doi:10.1111/bjd.13422

- East-Innis ADC, Stylianou K, Paolino A, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae: risk factors and associated disorders – a retrospective study. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:828-832. doi:10.1111/ijd.13678

- Goette DK, Berger TG. Acne keloidalis nuchae. A transepithelial elimination disorder. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:442-444. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb00587.x

- Chouk C, Litaiem N, Jones M, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae: clinical and dermoscopic features. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222222. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222222

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) classically presents as chronic inflammation of the hair follicles on the occipital scalp/nape of the neck manifesting as papules and pustules that may progress to keloidlike scarring.1 Photographs depicting the typical clinical presentation of AKN are shown in the Figure. In the literature, AKN has been described as primarily occurring in postpubertal males of African descent.2 Despite its similar name, AKN is not related to acne vulgaris.3 The underlying cause of AKN is hypothesized to be multifactorial, including inflammation, infection, and trauma.2 Acne keloidalis nuchae is most common in males aged 14 to 50 years, which may indicate that increased androgens contribute to its development.3 In some cases, patients have reported developing AKN lesions after receiving a haircut or shaving, suggesting a potential role of trauma to the hair follicles and secondary infection.2 Histopathology typically shows a perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate that obscures the hair follicles with associated proximal fibrosis.4 On physical examination, dermoscopy can be used to visualize perifollicular pustules and fibrosis, which appears white, in the early stages of AKN. Patients may present with tufted hairs in more advanced stages.5 Patients with AKN often describe the lesions as pruritic and painful.2

In this study, we evaluated the most common treatment regimens used over a 6-year period by patients in the Los Angeles County hospital system in California and their efficacy on AKN lesions. Our study includes one of the largest cohorts of patients reported to date and as such demonstrates the real-world effects that current treatment regimens for AKN have on patient outcomes nationwide.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of patient medical records from the Los Angeles County hospital system i2b2 (i2b2 tranSMART Foundation) clinical data warehouse over a 6-year period (January 2017–January 2023). We used the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes L73.0 (acne keloid) and L73.1 (pseudofolliculitis barbae) to conduct our search in order to identify as many patients with follicular disorders as possible to include in the study. Of the 478 total medical records we reviewed, 183 patients were included based on a diagnosis of AKN by a dermatologist.

We then collected data on patient demographics and treatments received, including whether patients had received monotherapy or combination therapy. Of the 183 patients we initially identified, 4 were excluded from the study because they had not received any treatment, and 78 were excluded because no treatment outcomes were documented. The 101 patients who were included had received either monotherapy or a combination of treatments. Treatment outcomes were categorized as either improvement in the number and appearance of papules and/or keloidlike plaques, maintenance of stable lesions (ie, well controlled), and/or resolution of lesions as documented by the treating physician. No patients had overall worsening of their disease.

Results

Of the 101 patients included in the study, 34 (33.7%) received a combination of topical, systemic, and procedural treatments; 34 (33.7%) received a combination of topical and procedural treatments; 17 (16.8%) were treated with topicals only; 13 (12.9%) were treated with a combination of topical and systemic treatments; and 3 (3.0%) were treated with monotherapy of either a topical, systemic, or procedural therapy. Systemic and/or procedural therapy combined with topicals was provided as a first-line treatment for 63 (62.4%) patients. Treatment escalation to systemic or procedural therapy for those who did not respond to topical treatment was observed in 23 (22.8%) patients. The average number of unique treatments received per patient was 3.67.

Clindamycin and clobetasol were the most prescribed topical treatments, doxycycline was the most prescribed systemic therapy, and intralesional (IL) triamcinolone was the most performed procedural therapy. The most common treatment regimens were topical clindamycin and clobetasol, topical clindamycin and clobetasol with IL triamcinolone, and topical clindamycin and clobetasol with both IL triamcinolone and doxycycline.

Improvement in AKN lesions was reported for the majority of patients with known treatment outcomes across all types of regimens. Ninety-eight percent (99/101) of patients had improvement in lesions, 55.5% (56/101) had well-controlled lesions, and 20.8% (21/101) achieved resolution of disease. The treatment outcomes are outlined in eTables 1 and 2.

Comment

Most clinicians opted for a multitherapy treatment regimen, and improvement was noted in most patients regardless of which regimen was chosen. As expected, patients who had mild or early disease generally received topical agents first, including most commonly a mid- to high-potency steroid, antibiotic, retinoid, and/or antifungal; specifically, clindamycin, clobetasol, and fluocinolone were the most common agents chosen. Patients with severe disease were more likely to receive systemic and/or procedural treatments, including oral antibiotics or IL steroid injections most commonly. Improvement was documented in the majority of patients using these treatment regimens, and some patients did achieve full resolution of disease.

Our data cannot be used to determine which treatment alone is most effective for patients with AKN, as the patients in our study had varying levels of disease activity and types of lesions, and most received combination therapy. What our data do show is that combination therapies often work well to control or improve disease, but also that current therapeutic options only rarely lead to full resolution of disease.

Limitations of our study included an inability to stratify disease, an inability to rigorously analyze specific treatment outcomes since most patients did not receive monotherapy. The strength of our study is its size, which allows us to show that many different treatment regimens currently are being employed by dermatologists to treat AKN, and most of these seem to be somewhat effective.

Conclusion

Acne keloidalis nuchae is difficult to treat due to a lack of understanding of which pathophysiologic mechanisms dominate in any given patient, a lack of good data on treatment outcomes, and the variability of ways that the disease manifests. Thus far, as shown by the patients described in this study, the most efficacious treatment regimens seem to be combination therapies that target the multifactorial causes of this disease. Physicians should continue to choose treatments based on disease severity and cutaneous manifestations, tailor their approach by accounting for patient preferences, and consider a multimodal approach to treatment.

Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) classically presents as chronic inflammation of the hair follicles on the occipital scalp/nape of the neck manifesting as papules and pustules that may progress to keloidlike scarring.1 Photographs depicting the typical clinical presentation of AKN are shown in the Figure. In the literature, AKN has been described as primarily occurring in postpubertal males of African descent.2 Despite its similar name, AKN is not related to acne vulgaris.3 The underlying cause of AKN is hypothesized to be multifactorial, including inflammation, infection, and trauma.2 Acne keloidalis nuchae is most common in males aged 14 to 50 years, which may indicate that increased androgens contribute to its development.3 In some cases, patients have reported developing AKN lesions after receiving a haircut or shaving, suggesting a potential role of trauma to the hair follicles and secondary infection.2 Histopathology typically shows a perifollicular inflammatory infiltrate that obscures the hair follicles with associated proximal fibrosis.4 On physical examination, dermoscopy can be used to visualize perifollicular pustules and fibrosis, which appears white, in the early stages of AKN. Patients may present with tufted hairs in more advanced stages.5 Patients with AKN often describe the lesions as pruritic and painful.2

In this study, we evaluated the most common treatment regimens used over a 6-year period by patients in the Los Angeles County hospital system in California and their efficacy on AKN lesions. Our study includes one of the largest cohorts of patients reported to date and as such demonstrates the real-world effects that current treatment regimens for AKN have on patient outcomes nationwide.

Methods

We performed a retrospective cross-sectional analysis of patient medical records from the Los Angeles County hospital system i2b2 (i2b2 tranSMART Foundation) clinical data warehouse over a 6-year period (January 2017–January 2023). We used the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes L73.0 (acne keloid) and L73.1 (pseudofolliculitis barbae) to conduct our search in order to identify as many patients with follicular disorders as possible to include in the study. Of the 478 total medical records we reviewed, 183 patients were included based on a diagnosis of AKN by a dermatologist.

We then collected data on patient demographics and treatments received, including whether patients had received monotherapy or combination therapy. Of the 183 patients we initially identified, 4 were excluded from the study because they had not received any treatment, and 78 were excluded because no treatment outcomes were documented. The 101 patients who were included had received either monotherapy or a combination of treatments. Treatment outcomes were categorized as either improvement in the number and appearance of papules and/or keloidlike plaques, maintenance of stable lesions (ie, well controlled), and/or resolution of lesions as documented by the treating physician. No patients had overall worsening of their disease.

Results

Of the 101 patients included in the study, 34 (33.7%) received a combination of topical, systemic, and procedural treatments; 34 (33.7%) received a combination of topical and procedural treatments; 17 (16.8%) were treated with topicals only; 13 (12.9%) were treated with a combination of topical and systemic treatments; and 3 (3.0%) were treated with monotherapy of either a topical, systemic, or procedural therapy. Systemic and/or procedural therapy combined with topicals was provided as a first-line treatment for 63 (62.4%) patients. Treatment escalation to systemic or procedural therapy for those who did not respond to topical treatment was observed in 23 (22.8%) patients. The average number of unique treatments received per patient was 3.67.

Clindamycin and clobetasol were the most prescribed topical treatments, doxycycline was the most prescribed systemic therapy, and intralesional (IL) triamcinolone was the most performed procedural therapy. The most common treatment regimens were topical clindamycin and clobetasol, topical clindamycin and clobetasol with IL triamcinolone, and topical clindamycin and clobetasol with both IL triamcinolone and doxycycline.

Improvement in AKN lesions was reported for the majority of patients with known treatment outcomes across all types of regimens. Ninety-eight percent (99/101) of patients had improvement in lesions, 55.5% (56/101) had well-controlled lesions, and 20.8% (21/101) achieved resolution of disease. The treatment outcomes are outlined in eTables 1 and 2.

Comment

Most clinicians opted for a multitherapy treatment regimen, and improvement was noted in most patients regardless of which regimen was chosen. As expected, patients who had mild or early disease generally received topical agents first, including most commonly a mid- to high-potency steroid, antibiotic, retinoid, and/or antifungal; specifically, clindamycin, clobetasol, and fluocinolone were the most common agents chosen. Patients with severe disease were more likely to receive systemic and/or procedural treatments, including oral antibiotics or IL steroid injections most commonly. Improvement was documented in the majority of patients using these treatment regimens, and some patients did achieve full resolution of disease.

Our data cannot be used to determine which treatment alone is most effective for patients with AKN, as the patients in our study had varying levels of disease activity and types of lesions, and most received combination therapy. What our data do show is that combination therapies often work well to control or improve disease, but also that current therapeutic options only rarely lead to full resolution of disease.

Limitations of our study included an inability to stratify disease, an inability to rigorously analyze specific treatment outcomes since most patients did not receive monotherapy. The strength of our study is its size, which allows us to show that many different treatment regimens currently are being employed by dermatologists to treat AKN, and most of these seem to be somewhat effective.

Conclusion

Acne keloidalis nuchae is difficult to treat due to a lack of understanding of which pathophysiologic mechanisms dominate in any given patient, a lack of good data on treatment outcomes, and the variability of ways that the disease manifests. Thus far, as shown by the patients described in this study, the most efficacious treatment regimens seem to be combination therapies that target the multifactorial causes of this disease. Physicians should continue to choose treatments based on disease severity and cutaneous manifestations, tailor their approach by accounting for patient preferences, and consider a multimodal approach to treatment.

- Maranda EL, Simmons BJ, Nguyen AH, et al. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae: a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:363-378. doi:10.1007/s13555-016-0134-5<

- Ogunbiyi A, Adedokun B. Perceived aetiological factors of folliculitis keloidalis nuchae (acne keloidalis) and treatment options among Nigerian men. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(Suppl 2):22-25. doi:10.1111/bjd.13422

- East-Innis ADC, Stylianou K, Paolino A, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae: risk factors and associated disorders – a retrospective study. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:828-832. doi:10.1111/ijd.13678

- Goette DK, Berger TG. Acne keloidalis nuchae. A transepithelial elimination disorder. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:442-444. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb00587.x

- Chouk C, Litaiem N, Jones M, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae: clinical and dermoscopic features. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222222. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222222

- Maranda EL, Simmons BJ, Nguyen AH, et al. Treatment of acne keloidalis nuchae: a systematic review of the literature. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:363-378. doi:10.1007/s13555-016-0134-5<

- Ogunbiyi A, Adedokun B. Perceived aetiological factors of folliculitis keloidalis nuchae (acne keloidalis) and treatment options among Nigerian men. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(Suppl 2):22-25. doi:10.1111/bjd.13422

- East-Innis ADC, Stylianou K, Paolino A, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae: risk factors and associated disorders – a retrospective study. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:828-832. doi:10.1111/ijd.13678

- Goette DK, Berger TG. Acne keloidalis nuchae. A transepithelial elimination disorder. Int J Dermatol. 1987;26:442-444. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1987.tb00587.x

- Chouk C, Litaiem N, Jones M, et al. Acne keloidalis nuchae: clinical and dermoscopic features. BMJ Case Rep. 2017;2017:bcr2017222222. doi:10.1136/bcr-2017-222222

Treatment of Acne Keloidalis Nuchae in a Southern California Population

Treatment of Acne Keloidalis Nuchae in a Southern California Population

PRACTICE POINTS

- Acne keloidalis nuchae (AKN) is a rare inflammatory skin disease that manifests with papules, pustules, and plaques on the occipital scalp.

- Initial treatment for patients with mild to moderate AKN disease most commonly is topical clindamycin and clobetasol; patients with moderate to severe AKN disease may require adjunctive treatment with oral doxycycline and/or intralesional triamcinolone.

- Combination therapy that targets the multifactorial pathophysiology of AKN (inflammatory, infectious, and traumatic) is most efficacious overall.

- The majority of patients experience improvement of AKN with treatment, but full resolution is less common.