User login

Oral Contraceptives for Acne Treatment: US Dermatologists’ Knowledge, Comfort, and Prescribing Practices

The incidence of acne in adult females is rising,1 and treatment with combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) is becoming an increasingly important therapy for women with acne. Prior reports have indicated that OCPs were as effective as systemic antibiotics in reducing inflammatory, noninflammatory, and total facial acne lesions after 6 months of treatment.2,3 The acne management guidelines of the American Academy of Dermatology confer OCPs a grade A recommendation based on consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence.4

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 3 OCPs for the treatment of acne in adult women: norgestimate–ethinyl estradiol in 1997, norethindrone acetate–ethinyl estradiol in 2001, and drospirenone–ethinyl estradiol in 2007.5 However, the use of these OCPs is poorly understood by many dermatologists. One study showed that dermatologists prescribed OCPs in only 2% of visits with female patients aged 12 to 55 years who presented for acne treatment, which is less often than obstetrician/gynecologists (36%) and internists (11%),6 perhaps due to perceived risks or unfamiliarity with OCP formulations and guidelines among dermatologists.7 Adverse effects of OCPs include venous thromboembolism (VTE), myocardial infarction, and hypertension,8 but they generally are well tolerated.9

Even less is known about dermatologists’ use of drospirenone-containing OCPs (DCOCPs), which contain the only FDA-approved progestin that blocks androgen receptors. In prior studies, treatment with DCOCPs was associated with greater reductions in total lesion count and investigator-graded acne severity compared to early-generation OCPs.10,11 However, DCOCPs have been associated with a greater risk for VTE (4.0–6.3 times higher than OCP nonuse; 1.0–3.3 times higher than levonorgestrel-containing OCPs),12 which may explain the decline in DCOCP prescriptions among gynecologists in Germany from 23.8% of OCP prescriptions in 2007 to 11.4% in 2011.13

In this study, we surveyed US dermatologists about their knowledge, comfort, and prescribing practices pertaining to the use of OCPs. We compare OCP-prescribing to nonprescribing dermatologists, and those frequently prescribing DCOCPs to those who infrequently prescribe DCOCPs.

Methods

Survey Design

We performed a cross-sectional survey study using convenience sampling. The instrument was designed based on primary literature on OCPs in acne treatment and questionnaires assessing the use of OCPs in other specialties. Topics included prescribing practices, contraindications for OCPs defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),14 VTE risk, patient selection for hormonal acne therapy, comfort with prescribing OCP therapy, and participant demographics.

Skip logic was employed (ie, subsequent questions depended on prior answers). A pilot study surveyed 9 board-certified dermatologists at our home institution (Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York).

Data Collection

Eligible participants were board-certified US dermatologists. Data were collected and managed using an electronic data capture tool through the Weill Cornell Medical College Clinical & Translational Science Center. Surveys were distributed electronically to dermatologic society members, university alumni networks, investigators’ professional contacts, and dermatologists whose contact information was purchased from an email marketing company. Chain-referral sampling (ie, participants’ recruitment among their colleagues) was used. Surveys were distributed at a regional dermatology meeting. Responses were collected from November 2014 to April 2015. This study was approved by the institutional review board.

Statistical Analysis

For the descriptive data, all responses including pilot study participants were analyzed regardless of survey completion and were summarized using frequency counts and percentages (N=130).

For the analysis of OCP prescription predictors, the sample included all respondents answering the demographic questions and indicating if they prescribe OCPs (N=116). One respondent was excluded for answering other for current practice setting. Demographic predictors of OCP prescription were physician characteristics, geographic region, practice location population density, practice attributes, time spent on medical versus pediatric dermatology, number of weekly acne patients, and percentage of total patients who are female. Medical school graduation year was a categorical variable and was categorized as prior to 1997 (when norgestimate–ethinyl estradiol was FDA approved for acne5) versus 1997 or later. Respondents’ practice states were analyzed according to US regions—Northeast, Midwest, South, West/Pacific—and population density (persons per square mile) using US Census Bureau data.15,16

Univariate logistic regressions modeling OCP prescribing probability were performed for each demographic variable; a multivariable logistic model was constructed including all variables significant at α=.20 from univariate modeling.

To compare frequent prescribers versus infrequent prescribers of DCOCPs, we included all respondents answering whether they frequently prescribe DCOCPs and whether they believed the risk for VTE associated with DCOCPs differed from other OCPs (n=68). A univariate logistic regression was performed to model the probability of responding “Yes, they pose a greater risk” versus any of the other 3 responses by whether or not the respondent frequently prescribed DCOCPs for acne, and an unadjusted odds ratio was obtained. All P values were 2-tailed with statistical significance evaluated at α=.05. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated to assess precision of obtained estimates. Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4.

Results

Demographics

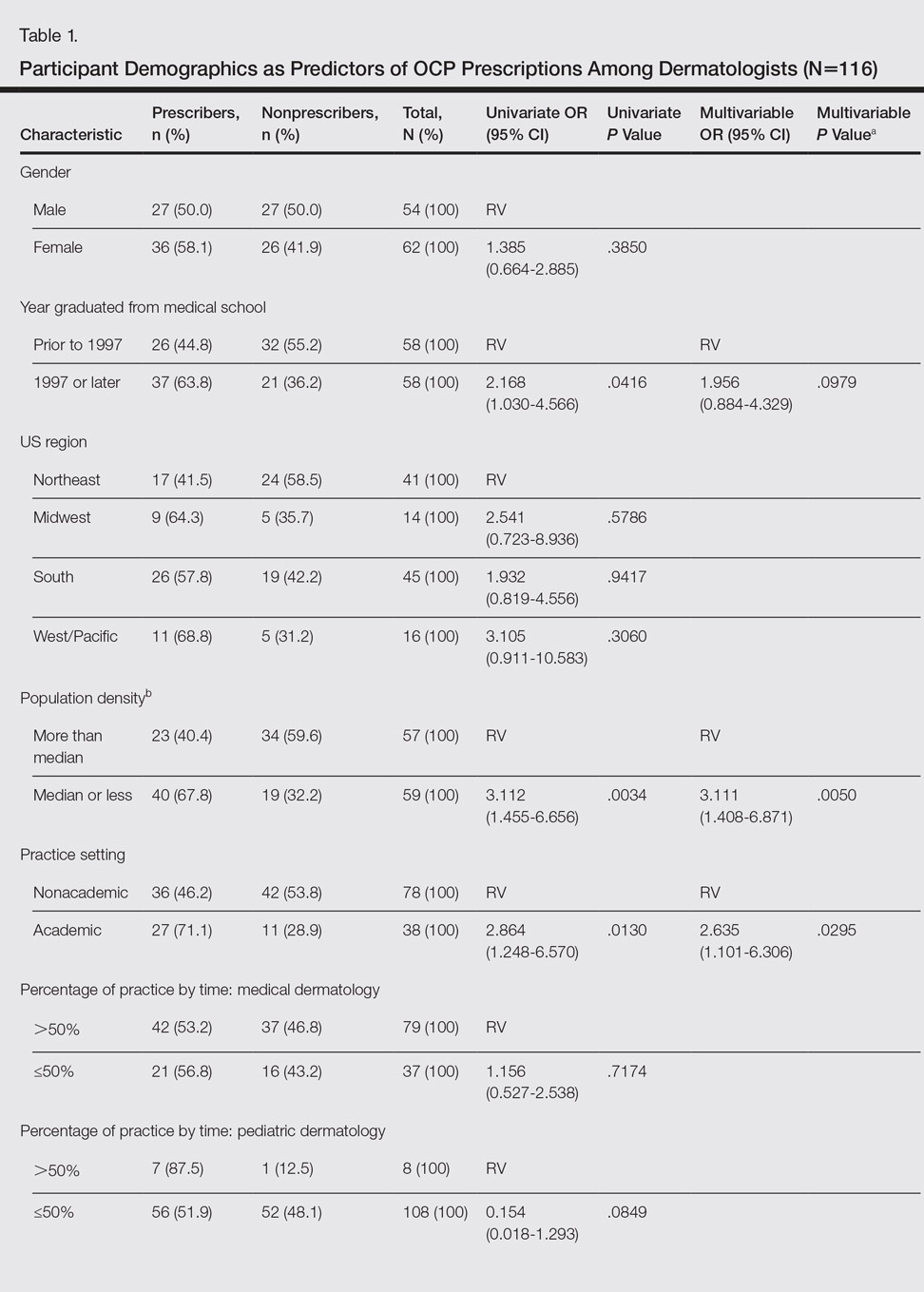

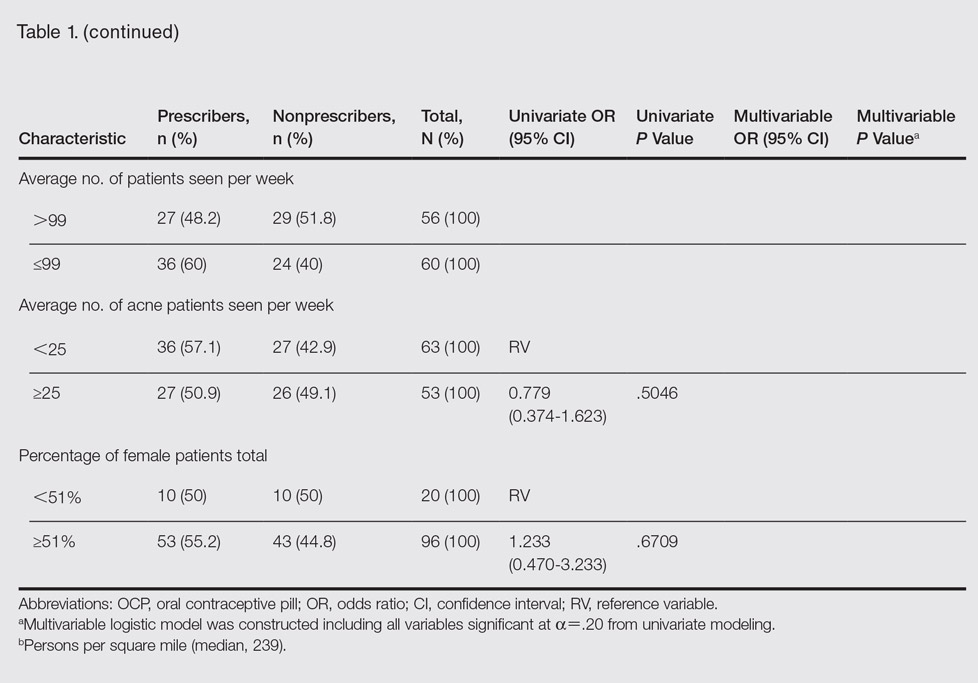

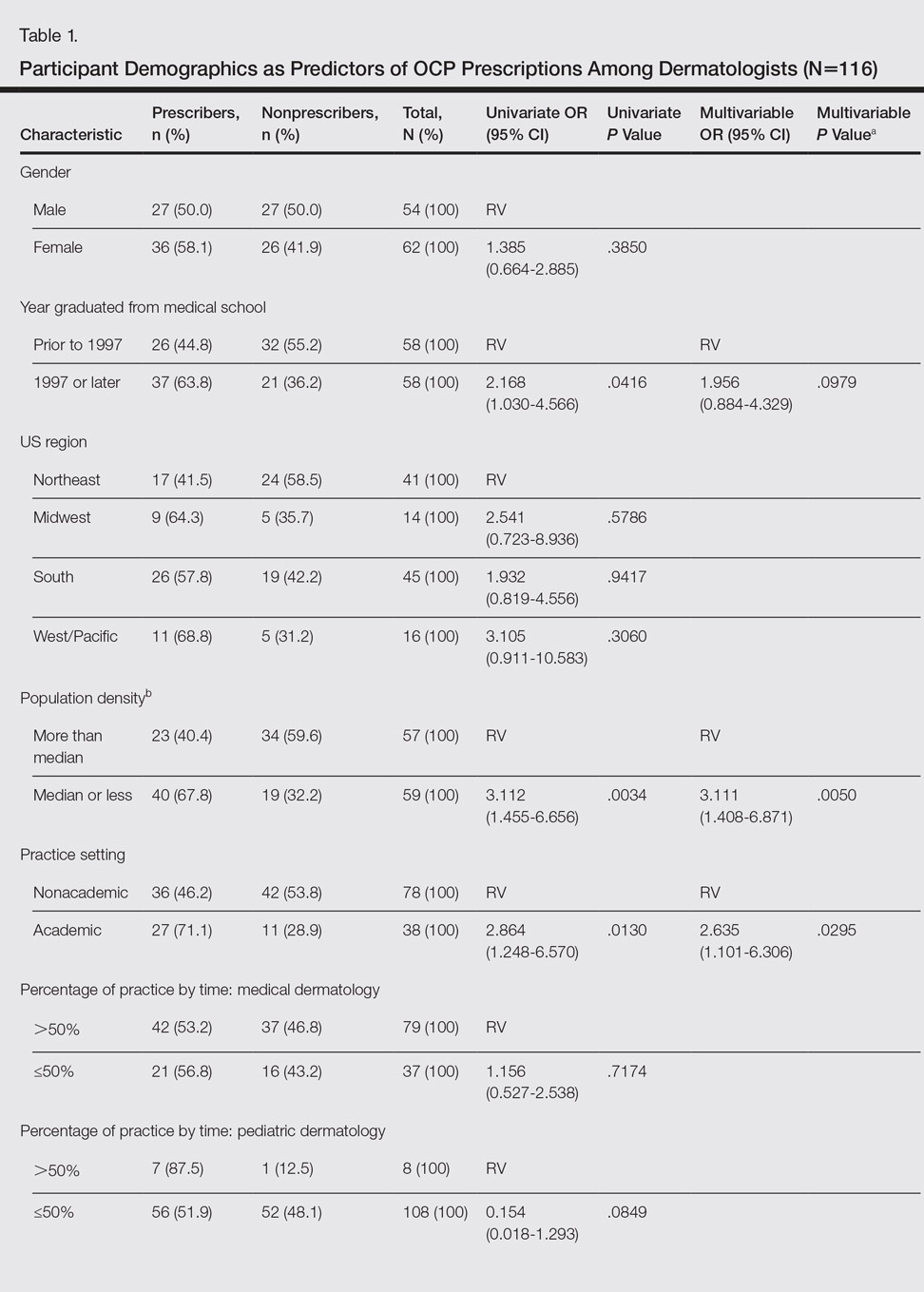

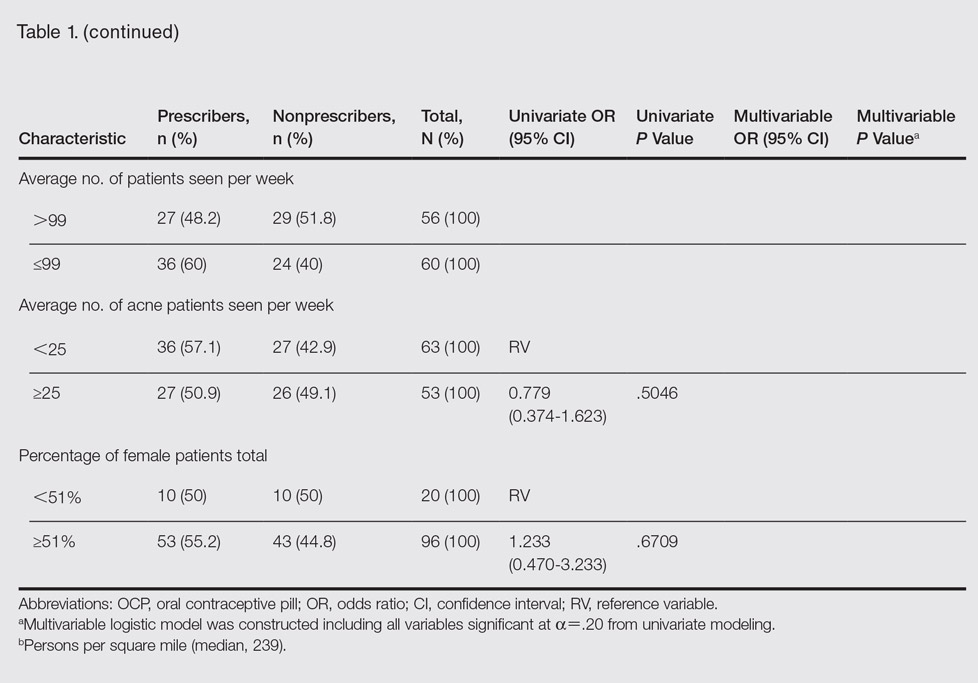

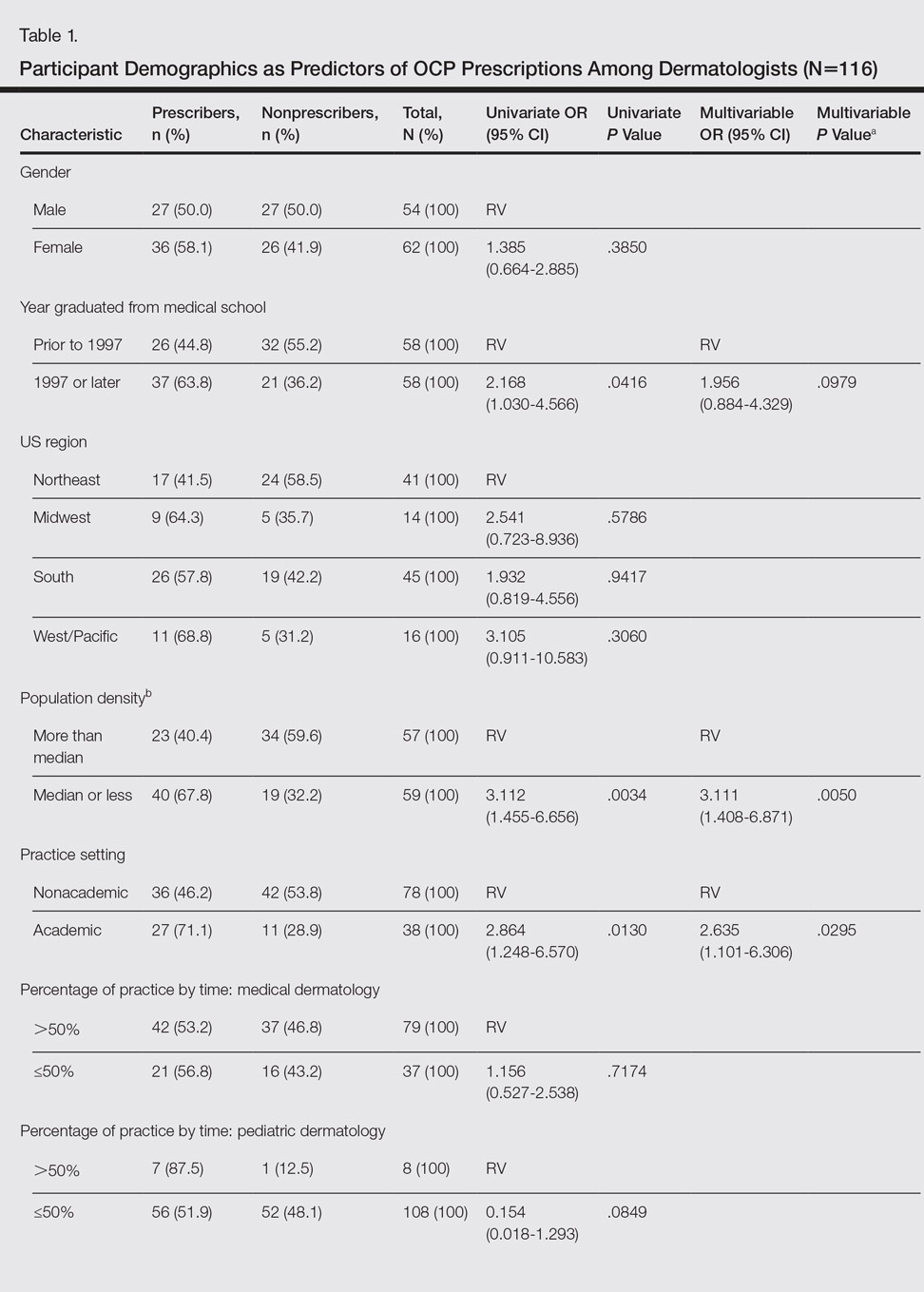

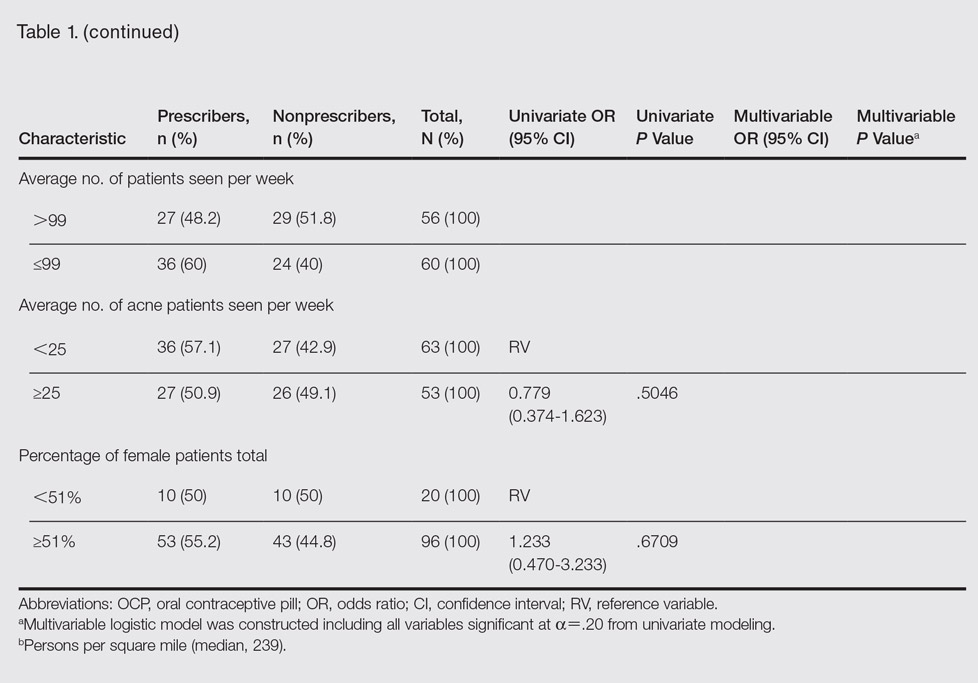

Participant demographics as predictors of OCP prescription practices are described in Table 1.

Knowledge

Oral contraceptive pills were endorsed as effective in the treatment of acne in women by 95.4% (124/130) of respondents. Among prescribers of OCPs for acne, 94.2% (65/69) believed OCPs were associated with an increased risk for VTE, no respondents thought OCPs were associated with a decreased VTE risk, 2.9% (2/69) believed OCPs did not affect VTE risk, and 2.9% (2/69) were unsure.

Among prescribers of OCPs for acne, 46.4% (32/69) believed DCOCPs posed a greater VTE risk than other OCPs. Odds of this response did not differ with frequent DCOCP prescribers versus infrequent prescribers (odds ratio, 0.731 [95% confidence interval, 0.272-1.964]; P=.5342). Participant responses on VTE risk and DCOCPs are provided in Table 2.

Dermatologists prescribing OCPs for acne endorsed greater likelihood of doing so in cases of cyclical flares with menstrual cycle (94.2% [65/69]), acne unresponsive to conventional therapy (87.0% [60/69]), acne on the lower half of the face (78.3% [54/69]), diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)(76.8% [53/69]), clinical suspicion of PCOS (71.0% [49/69]), concomitant hirsutism (71.0% [49/69]), late- or adult-onset acne (66.7% [46/69]), laboratory evidence of hyperandrogenism (60.9% [42/69]), and concomitant androgenetic alopecia (49.3% [34/69]).

Among dermatologists who prescribed OCPs for acne, CDC-defined absolute contraindications identified correctly were blood pressure of 160/100 mm Hg (59.4% [41/69]) and history of migraine with focal neurologic symptoms (49.3% [34/69]). The CDC-defined relative contraindications identified correctly were history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (1.4% [1/69]), breast cancer history with 5 years of no disease (15.9% [11/69]), hyperlipidemia (42.0% [29/69]), and 36 years or older smoking fewer than 15 cigarettes per day (21.7% [15/69]).

Comfort

Dermatologist self-reported comfort levels in prescribing OCPs for acne are shown in Table 3.

Prescribing Practices

Among all respondents, acne medications prescribed often included oral antibiotics (76.9% [100/130]), isotretinoin (41.5% [54/130]), and spironolactone (40.8% [53/130]).

Overall, 55.4% (72/130) of respondents prescribed OCPs for the following uses: acne (95.8% [69/72]), concomitant treatment with teratogenic medication (48.6% [35/72]), PCOS (34.7% [25/72]), hirsutism (26.4% [19/72]), androgenetic alopecia (19.4% [14/72]), SAHA (seborrhea, acne, hirsutism, alopecia) syndrome (12.5% [9/72]), and HAIR-AN (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans) syndrome (11.1% [8/72]). For teratogenic medications, dermatologists prescribing OCPs did so with isotretinoin (77.8% [56/72]), spironolactone (73.6% [53/72]), tetracycline antibiotics (37.5% [27/72]), and other (34.7% [25/72]).

Of dermatologists prescribing OCPs for acne, frequency included often (19% [13/69]), sometimes (45% [31/69]), and rarely (36% [25/69]). The most frequently prescribed OCPs included Ortho Tri-Cyclen (Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc)(80% [55/69]), Yaz (Bayer)(64% [44/69]), and Estrostep (Warner Chilcott)(19% [13/69]). Fill-in responses included Desogen (Merck & Co, Inc)(3/69 [4%]), Alesse (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc)(3/69 [4%]), Lutera (Watson Pharma, Inc)(1/69 [1%]), Loestrin (Warner Chilcott)(1/69 [1%]), and Yasmin (Bayer)(1/69 [1%]).

In univariate regressions, graduation from medical school in 1997 or later (P=.0416), academic practice setting (P=.0130), and low-density practice setting (P=.0034) were significant predictors of prescribing OCPs. In multivariable regression, only academic practice setting (P=.0295) and low-density practice setting (P=.0050) remained significant predictors. Demographic predictors are summarized in Table 1.

Comment

Our results suggest that most dermatologists (95.4%) believe OCPs effectively treat acne; however, only 54% of respondents reported prescribing them. Academic dermatologists were more likely to prescribe OCPs than nonacademic dermatologists, possibly indicating that academic dermatologists are more familiar with the literature on the efficacy and use of OCPs. Nearly half of respondents seeing 25 or more acne patients weekly did not prescribe OCPs, suggesting a notable practice gap. Dermatologists in less dense US regions were more likely to prescribe OCPs, perhaps because dermatologists may be more likely to prescribe OCPs than refer patients in health care access–limited areas, just as primary care providers treat a broader range of conditions in low-density rural areas than urban ones.17 Exploring all dermatologists’ referral patterns for OCPs is warranted.

A strong knowledge area revealed from this study was hormonal treatment of acne in women, a vital area because appropriate patient selection is key to treatment success.8 Weaker knowledge areas included OCP contraindications and differences in VTE risk between formulations containing drospirenone and those not containing drospirenone. Only half the sample identified CDC-defined absolute contraindications, suggesting an education target for dermatologists to ensure patient safety. In contrast, respondents were conservative about relative contraindications, with most identifying deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, remote breast cancer history, and light smoking at 36 years or older as absolute contraindications. These results could reflect weighing the risk of relative contraindications against the benefit in acne, resulting in appropriately more conservative management than overall guidelines suggest. If so, it may suggest that dermatologists are adapting overall guidelines appropriately for use of OCPs in skin conditions.

Nearly all respondents knew that OCPs are associated with an increased risk for VTE. Approximately half understood that DCOCPs are associated with a greater VTE risk than other OCPs, with no difference between frequent and infrequent prescribers. Comparing these results to the findings on OCP prescribing overall, some dermatologists’ risk-benefit calculation for VTE differs from other specialties because DCOCPs have superior efficacy in acne, whereas DCOCPs have similar contraceptive efficacy to other OCPs.18 The fact that more dermatologists believed VTE to be an absolute contraindication than hypertension suggests dermatologists have a heightened awareness of VTE risk but prescribe DCOCPs for acne despite it.

Most OCP prescribers felt very comfortable selecting good candidates for OCPs (55.5%) and counseling on treatment initiation (45.8%) and side effects (48.6%). Only 22.2%, by contrast, were very comfortable managing side effects. This finding likely reflects the notion that VTEs are not most appropriately managed by a dermatologist. Exploring if a greater comfort level in managing side effects would make dermatologists more likely to prescribe OCPs is worthwhile. Additionally, exploring why many dermatologists do not prescribe OCPs despite believing they are effective for acne is warranted.

Study limitations included the use of convenience sampling. Additionally, our study did not investigate dermatologists’ reasons for not prescribing OCPs.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that dermatologists believe OCPs effectively treat acne in women and that most dermatologists prescribing OCPs do so for acne treatment. Academic practice setting was associated with higher odds of prescribing OCPs than a nonacademic setting, but the number of weekly acne patients did not impact the likelihood of prescribing OCPs, which suggests a treatment gap warranting education efforts for dermatologists in nonacademic settings seeing many acne patients. Our study also suggests that awareness of the increased risk for VTE associated with DCOCPs is not associated with lower likelihood of prescribing DCOCPs, suggesting dermatologists may find greater treatment efficacy to be worth the higher risk.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Department of Dermatology at the Weill Cornell College of Medicine (New York, New York) for providing funding to complete this study. We also acknowledge Paul Christos, DrPH, MS (New York, New York), and Xuming Sun, MS (New York, New York), for their assistance with the survey design. We also are indebted to numerous dermatologic professional societies for allowing the survey to be distributed to their membership.

- Kim GK, Michaels BB. Post-adolescent acne in women: more common and more clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:708-713.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. July 11, 2012:CD004425.

- Koo EB, Petersen TD, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:450-459.

- Strauss JS, Krowchuk DP, Leyden JJ, et al; American Academy of Dermatology/American Academy of Dermatology Association. Guidelines of care for acne vulgaris management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:651-663.

- Harper JC. Should dermatologists prescribe hormonal contraceptives for acne? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:452-457.

- Landis ET, Levender MM, Davis SA, et al. Isotretinoin and oral contraceptive use in female acne patients varies by physician specialty: analysis of data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:272-277.

- Lam C, Zaenglein AL. Contraceptive use in acne. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:502-515.

- Katsambas AD, Dessinioti C. Hormonal therapy for acne: why not as first line therapy? facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:17-23.

- Dragoman MV. The combined oral contraceptive pill—recent developments, risks and benefits. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:825-834.

- Thorneycroft IH, Gollnick H, Schellschmidt I. Superiority of a combined contraceptive containing drospirenone to a triphasic preparation containing norgestimate in acne treatment. Cutis. 2004;74:123-130.

- Mansour D, Verhoeven C, Sommer W, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a monophasic combined oral contraceptive containing nomegestrol acetate and 17β-oestradiol in a 24/4 regimen, in comparison to an oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol and drospirenone in a 21/7 regimen. Eur J Contracept Reproduct Health Care. 2011;16:430-443.

- Wu CQ, Grandi SM, Filion KB, et al. Drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive pills and the risk of venous and arterial thrombosis: a systematic review. BJOG. 2013;120:801-810.

- Ziller M, Rashed AN, Ziller V, et al. The prescribing of contraceptives for adolescents in German gynecologic practices in 2007 and 2011: a retrospective database analysis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:261-264.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1-86.

- United States Census Bureau. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. New York, NY: United States Department of Commerce; 2010.

- Resident Population Data—Population Density, 1910 to 2010. U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. http ://www.census.gov/2010census/data/apportionment-dens-text.php. Accessed January 9, 2017.

- Reschovsky A, Zahner SJ. Forecasting the revenues of local public health departments in the shadows of the “Great Recession.” J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22:120-128.

- Klipping C, Duijkers I, Fortier MP, et al. Contraceptive efficacy and tolerability of ethinylestradiol 20 μg/drospirenone 3 mg in a flexible extended regimen: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38:73-83.

The incidence of acne in adult females is rising,1 and treatment with combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) is becoming an increasingly important therapy for women with acne. Prior reports have indicated that OCPs were as effective as systemic antibiotics in reducing inflammatory, noninflammatory, and total facial acne lesions after 6 months of treatment.2,3 The acne management guidelines of the American Academy of Dermatology confer OCPs a grade A recommendation based on consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence.4

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 3 OCPs for the treatment of acne in adult women: norgestimate–ethinyl estradiol in 1997, norethindrone acetate–ethinyl estradiol in 2001, and drospirenone–ethinyl estradiol in 2007.5 However, the use of these OCPs is poorly understood by many dermatologists. One study showed that dermatologists prescribed OCPs in only 2% of visits with female patients aged 12 to 55 years who presented for acne treatment, which is less often than obstetrician/gynecologists (36%) and internists (11%),6 perhaps due to perceived risks or unfamiliarity with OCP formulations and guidelines among dermatologists.7 Adverse effects of OCPs include venous thromboembolism (VTE), myocardial infarction, and hypertension,8 but they generally are well tolerated.9

Even less is known about dermatologists’ use of drospirenone-containing OCPs (DCOCPs), which contain the only FDA-approved progestin that blocks androgen receptors. In prior studies, treatment with DCOCPs was associated with greater reductions in total lesion count and investigator-graded acne severity compared to early-generation OCPs.10,11 However, DCOCPs have been associated with a greater risk for VTE (4.0–6.3 times higher than OCP nonuse; 1.0–3.3 times higher than levonorgestrel-containing OCPs),12 which may explain the decline in DCOCP prescriptions among gynecologists in Germany from 23.8% of OCP prescriptions in 2007 to 11.4% in 2011.13

In this study, we surveyed US dermatologists about their knowledge, comfort, and prescribing practices pertaining to the use of OCPs. We compare OCP-prescribing to nonprescribing dermatologists, and those frequently prescribing DCOCPs to those who infrequently prescribe DCOCPs.

Methods

Survey Design

We performed a cross-sectional survey study using convenience sampling. The instrument was designed based on primary literature on OCPs in acne treatment and questionnaires assessing the use of OCPs in other specialties. Topics included prescribing practices, contraindications for OCPs defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),14 VTE risk, patient selection for hormonal acne therapy, comfort with prescribing OCP therapy, and participant demographics.

Skip logic was employed (ie, subsequent questions depended on prior answers). A pilot study surveyed 9 board-certified dermatologists at our home institution (Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York).

Data Collection

Eligible participants were board-certified US dermatologists. Data were collected and managed using an electronic data capture tool through the Weill Cornell Medical College Clinical & Translational Science Center. Surveys were distributed electronically to dermatologic society members, university alumni networks, investigators’ professional contacts, and dermatologists whose contact information was purchased from an email marketing company. Chain-referral sampling (ie, participants’ recruitment among their colleagues) was used. Surveys were distributed at a regional dermatology meeting. Responses were collected from November 2014 to April 2015. This study was approved by the institutional review board.

Statistical Analysis

For the descriptive data, all responses including pilot study participants were analyzed regardless of survey completion and were summarized using frequency counts and percentages (N=130).

For the analysis of OCP prescription predictors, the sample included all respondents answering the demographic questions and indicating if they prescribe OCPs (N=116). One respondent was excluded for answering other for current practice setting. Demographic predictors of OCP prescription were physician characteristics, geographic region, practice location population density, practice attributes, time spent on medical versus pediatric dermatology, number of weekly acne patients, and percentage of total patients who are female. Medical school graduation year was a categorical variable and was categorized as prior to 1997 (when norgestimate–ethinyl estradiol was FDA approved for acne5) versus 1997 or later. Respondents’ practice states were analyzed according to US regions—Northeast, Midwest, South, West/Pacific—and population density (persons per square mile) using US Census Bureau data.15,16

Univariate logistic regressions modeling OCP prescribing probability were performed for each demographic variable; a multivariable logistic model was constructed including all variables significant at α=.20 from univariate modeling.

To compare frequent prescribers versus infrequent prescribers of DCOCPs, we included all respondents answering whether they frequently prescribe DCOCPs and whether they believed the risk for VTE associated with DCOCPs differed from other OCPs (n=68). A univariate logistic regression was performed to model the probability of responding “Yes, they pose a greater risk” versus any of the other 3 responses by whether or not the respondent frequently prescribed DCOCPs for acne, and an unadjusted odds ratio was obtained. All P values were 2-tailed with statistical significance evaluated at α=.05. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated to assess precision of obtained estimates. Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4.

Results

Demographics

Participant demographics as predictors of OCP prescription practices are described in Table 1.

Knowledge

Oral contraceptive pills were endorsed as effective in the treatment of acne in women by 95.4% (124/130) of respondents. Among prescribers of OCPs for acne, 94.2% (65/69) believed OCPs were associated with an increased risk for VTE, no respondents thought OCPs were associated with a decreased VTE risk, 2.9% (2/69) believed OCPs did not affect VTE risk, and 2.9% (2/69) were unsure.

Among prescribers of OCPs for acne, 46.4% (32/69) believed DCOCPs posed a greater VTE risk than other OCPs. Odds of this response did not differ with frequent DCOCP prescribers versus infrequent prescribers (odds ratio, 0.731 [95% confidence interval, 0.272-1.964]; P=.5342). Participant responses on VTE risk and DCOCPs are provided in Table 2.

Dermatologists prescribing OCPs for acne endorsed greater likelihood of doing so in cases of cyclical flares with menstrual cycle (94.2% [65/69]), acne unresponsive to conventional therapy (87.0% [60/69]), acne on the lower half of the face (78.3% [54/69]), diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)(76.8% [53/69]), clinical suspicion of PCOS (71.0% [49/69]), concomitant hirsutism (71.0% [49/69]), late- or adult-onset acne (66.7% [46/69]), laboratory evidence of hyperandrogenism (60.9% [42/69]), and concomitant androgenetic alopecia (49.3% [34/69]).

Among dermatologists who prescribed OCPs for acne, CDC-defined absolute contraindications identified correctly were blood pressure of 160/100 mm Hg (59.4% [41/69]) and history of migraine with focal neurologic symptoms (49.3% [34/69]). The CDC-defined relative contraindications identified correctly were history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (1.4% [1/69]), breast cancer history with 5 years of no disease (15.9% [11/69]), hyperlipidemia (42.0% [29/69]), and 36 years or older smoking fewer than 15 cigarettes per day (21.7% [15/69]).

Comfort

Dermatologist self-reported comfort levels in prescribing OCPs for acne are shown in Table 3.

Prescribing Practices

Among all respondents, acne medications prescribed often included oral antibiotics (76.9% [100/130]), isotretinoin (41.5% [54/130]), and spironolactone (40.8% [53/130]).

Overall, 55.4% (72/130) of respondents prescribed OCPs for the following uses: acne (95.8% [69/72]), concomitant treatment with teratogenic medication (48.6% [35/72]), PCOS (34.7% [25/72]), hirsutism (26.4% [19/72]), androgenetic alopecia (19.4% [14/72]), SAHA (seborrhea, acne, hirsutism, alopecia) syndrome (12.5% [9/72]), and HAIR-AN (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans) syndrome (11.1% [8/72]). For teratogenic medications, dermatologists prescribing OCPs did so with isotretinoin (77.8% [56/72]), spironolactone (73.6% [53/72]), tetracycline antibiotics (37.5% [27/72]), and other (34.7% [25/72]).

Of dermatologists prescribing OCPs for acne, frequency included often (19% [13/69]), sometimes (45% [31/69]), and rarely (36% [25/69]). The most frequently prescribed OCPs included Ortho Tri-Cyclen (Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc)(80% [55/69]), Yaz (Bayer)(64% [44/69]), and Estrostep (Warner Chilcott)(19% [13/69]). Fill-in responses included Desogen (Merck & Co, Inc)(3/69 [4%]), Alesse (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc)(3/69 [4%]), Lutera (Watson Pharma, Inc)(1/69 [1%]), Loestrin (Warner Chilcott)(1/69 [1%]), and Yasmin (Bayer)(1/69 [1%]).

In univariate regressions, graduation from medical school in 1997 or later (P=.0416), academic practice setting (P=.0130), and low-density practice setting (P=.0034) were significant predictors of prescribing OCPs. In multivariable regression, only academic practice setting (P=.0295) and low-density practice setting (P=.0050) remained significant predictors. Demographic predictors are summarized in Table 1.

Comment

Our results suggest that most dermatologists (95.4%) believe OCPs effectively treat acne; however, only 54% of respondents reported prescribing them. Academic dermatologists were more likely to prescribe OCPs than nonacademic dermatologists, possibly indicating that academic dermatologists are more familiar with the literature on the efficacy and use of OCPs. Nearly half of respondents seeing 25 or more acne patients weekly did not prescribe OCPs, suggesting a notable practice gap. Dermatologists in less dense US regions were more likely to prescribe OCPs, perhaps because dermatologists may be more likely to prescribe OCPs than refer patients in health care access–limited areas, just as primary care providers treat a broader range of conditions in low-density rural areas than urban ones.17 Exploring all dermatologists’ referral patterns for OCPs is warranted.

A strong knowledge area revealed from this study was hormonal treatment of acne in women, a vital area because appropriate patient selection is key to treatment success.8 Weaker knowledge areas included OCP contraindications and differences in VTE risk between formulations containing drospirenone and those not containing drospirenone. Only half the sample identified CDC-defined absolute contraindications, suggesting an education target for dermatologists to ensure patient safety. In contrast, respondents were conservative about relative contraindications, with most identifying deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, remote breast cancer history, and light smoking at 36 years or older as absolute contraindications. These results could reflect weighing the risk of relative contraindications against the benefit in acne, resulting in appropriately more conservative management than overall guidelines suggest. If so, it may suggest that dermatologists are adapting overall guidelines appropriately for use of OCPs in skin conditions.

Nearly all respondents knew that OCPs are associated with an increased risk for VTE. Approximately half understood that DCOCPs are associated with a greater VTE risk than other OCPs, with no difference between frequent and infrequent prescribers. Comparing these results to the findings on OCP prescribing overall, some dermatologists’ risk-benefit calculation for VTE differs from other specialties because DCOCPs have superior efficacy in acne, whereas DCOCPs have similar contraceptive efficacy to other OCPs.18 The fact that more dermatologists believed VTE to be an absolute contraindication than hypertension suggests dermatologists have a heightened awareness of VTE risk but prescribe DCOCPs for acne despite it.

Most OCP prescribers felt very comfortable selecting good candidates for OCPs (55.5%) and counseling on treatment initiation (45.8%) and side effects (48.6%). Only 22.2%, by contrast, were very comfortable managing side effects. This finding likely reflects the notion that VTEs are not most appropriately managed by a dermatologist. Exploring if a greater comfort level in managing side effects would make dermatologists more likely to prescribe OCPs is worthwhile. Additionally, exploring why many dermatologists do not prescribe OCPs despite believing they are effective for acne is warranted.

Study limitations included the use of convenience sampling. Additionally, our study did not investigate dermatologists’ reasons for not prescribing OCPs.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that dermatologists believe OCPs effectively treat acne in women and that most dermatologists prescribing OCPs do so for acne treatment. Academic practice setting was associated with higher odds of prescribing OCPs than a nonacademic setting, but the number of weekly acne patients did not impact the likelihood of prescribing OCPs, which suggests a treatment gap warranting education efforts for dermatologists in nonacademic settings seeing many acne patients. Our study also suggests that awareness of the increased risk for VTE associated with DCOCPs is not associated with lower likelihood of prescribing DCOCPs, suggesting dermatologists may find greater treatment efficacy to be worth the higher risk.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Department of Dermatology at the Weill Cornell College of Medicine (New York, New York) for providing funding to complete this study. We also acknowledge Paul Christos, DrPH, MS (New York, New York), and Xuming Sun, MS (New York, New York), for their assistance with the survey design. We also are indebted to numerous dermatologic professional societies for allowing the survey to be distributed to their membership.

The incidence of acne in adult females is rising,1 and treatment with combined oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) is becoming an increasingly important therapy for women with acne. Prior reports have indicated that OCPs were as effective as systemic antibiotics in reducing inflammatory, noninflammatory, and total facial acne lesions after 6 months of treatment.2,3 The acne management guidelines of the American Academy of Dermatology confer OCPs a grade A recommendation based on consistent and good-quality patient-oriented evidence.4

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved 3 OCPs for the treatment of acne in adult women: norgestimate–ethinyl estradiol in 1997, norethindrone acetate–ethinyl estradiol in 2001, and drospirenone–ethinyl estradiol in 2007.5 However, the use of these OCPs is poorly understood by many dermatologists. One study showed that dermatologists prescribed OCPs in only 2% of visits with female patients aged 12 to 55 years who presented for acne treatment, which is less often than obstetrician/gynecologists (36%) and internists (11%),6 perhaps due to perceived risks or unfamiliarity with OCP formulations and guidelines among dermatologists.7 Adverse effects of OCPs include venous thromboembolism (VTE), myocardial infarction, and hypertension,8 but they generally are well tolerated.9

Even less is known about dermatologists’ use of drospirenone-containing OCPs (DCOCPs), which contain the only FDA-approved progestin that blocks androgen receptors. In prior studies, treatment with DCOCPs was associated with greater reductions in total lesion count and investigator-graded acne severity compared to early-generation OCPs.10,11 However, DCOCPs have been associated with a greater risk for VTE (4.0–6.3 times higher than OCP nonuse; 1.0–3.3 times higher than levonorgestrel-containing OCPs),12 which may explain the decline in DCOCP prescriptions among gynecologists in Germany from 23.8% of OCP prescriptions in 2007 to 11.4% in 2011.13

In this study, we surveyed US dermatologists about their knowledge, comfort, and prescribing practices pertaining to the use of OCPs. We compare OCP-prescribing to nonprescribing dermatologists, and those frequently prescribing DCOCPs to those who infrequently prescribe DCOCPs.

Methods

Survey Design

We performed a cross-sectional survey study using convenience sampling. The instrument was designed based on primary literature on OCPs in acne treatment and questionnaires assessing the use of OCPs in other specialties. Topics included prescribing practices, contraindications for OCPs defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC),14 VTE risk, patient selection for hormonal acne therapy, comfort with prescribing OCP therapy, and participant demographics.

Skip logic was employed (ie, subsequent questions depended on prior answers). A pilot study surveyed 9 board-certified dermatologists at our home institution (Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, New York).

Data Collection

Eligible participants were board-certified US dermatologists. Data were collected and managed using an electronic data capture tool through the Weill Cornell Medical College Clinical & Translational Science Center. Surveys were distributed electronically to dermatologic society members, university alumni networks, investigators’ professional contacts, and dermatologists whose contact information was purchased from an email marketing company. Chain-referral sampling (ie, participants’ recruitment among their colleagues) was used. Surveys were distributed at a regional dermatology meeting. Responses were collected from November 2014 to April 2015. This study was approved by the institutional review board.

Statistical Analysis

For the descriptive data, all responses including pilot study participants were analyzed regardless of survey completion and were summarized using frequency counts and percentages (N=130).

For the analysis of OCP prescription predictors, the sample included all respondents answering the demographic questions and indicating if they prescribe OCPs (N=116). One respondent was excluded for answering other for current practice setting. Demographic predictors of OCP prescription were physician characteristics, geographic region, practice location population density, practice attributes, time spent on medical versus pediatric dermatology, number of weekly acne patients, and percentage of total patients who are female. Medical school graduation year was a categorical variable and was categorized as prior to 1997 (when norgestimate–ethinyl estradiol was FDA approved for acne5) versus 1997 or later. Respondents’ practice states were analyzed according to US regions—Northeast, Midwest, South, West/Pacific—and population density (persons per square mile) using US Census Bureau data.15,16

Univariate logistic regressions modeling OCP prescribing probability were performed for each demographic variable; a multivariable logistic model was constructed including all variables significant at α=.20 from univariate modeling.

To compare frequent prescribers versus infrequent prescribers of DCOCPs, we included all respondents answering whether they frequently prescribe DCOCPs and whether they believed the risk for VTE associated with DCOCPs differed from other OCPs (n=68). A univariate logistic regression was performed to model the probability of responding “Yes, they pose a greater risk” versus any of the other 3 responses by whether or not the respondent frequently prescribed DCOCPs for acne, and an unadjusted odds ratio was obtained. All P values were 2-tailed with statistical significance evaluated at α=.05. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals were calculated to assess precision of obtained estimates. Analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.4.

Results

Demographics

Participant demographics as predictors of OCP prescription practices are described in Table 1.

Knowledge

Oral contraceptive pills were endorsed as effective in the treatment of acne in women by 95.4% (124/130) of respondents. Among prescribers of OCPs for acne, 94.2% (65/69) believed OCPs were associated with an increased risk for VTE, no respondents thought OCPs were associated with a decreased VTE risk, 2.9% (2/69) believed OCPs did not affect VTE risk, and 2.9% (2/69) were unsure.

Among prescribers of OCPs for acne, 46.4% (32/69) believed DCOCPs posed a greater VTE risk than other OCPs. Odds of this response did not differ with frequent DCOCP prescribers versus infrequent prescribers (odds ratio, 0.731 [95% confidence interval, 0.272-1.964]; P=.5342). Participant responses on VTE risk and DCOCPs are provided in Table 2.

Dermatologists prescribing OCPs for acne endorsed greater likelihood of doing so in cases of cyclical flares with menstrual cycle (94.2% [65/69]), acne unresponsive to conventional therapy (87.0% [60/69]), acne on the lower half of the face (78.3% [54/69]), diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)(76.8% [53/69]), clinical suspicion of PCOS (71.0% [49/69]), concomitant hirsutism (71.0% [49/69]), late- or adult-onset acne (66.7% [46/69]), laboratory evidence of hyperandrogenism (60.9% [42/69]), and concomitant androgenetic alopecia (49.3% [34/69]).

Among dermatologists who prescribed OCPs for acne, CDC-defined absolute contraindications identified correctly were blood pressure of 160/100 mm Hg (59.4% [41/69]) and history of migraine with focal neurologic symptoms (49.3% [34/69]). The CDC-defined relative contraindications identified correctly were history of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism (1.4% [1/69]), breast cancer history with 5 years of no disease (15.9% [11/69]), hyperlipidemia (42.0% [29/69]), and 36 years or older smoking fewer than 15 cigarettes per day (21.7% [15/69]).

Comfort

Dermatologist self-reported comfort levels in prescribing OCPs for acne are shown in Table 3.

Prescribing Practices

Among all respondents, acne medications prescribed often included oral antibiotics (76.9% [100/130]), isotretinoin (41.5% [54/130]), and spironolactone (40.8% [53/130]).

Overall, 55.4% (72/130) of respondents prescribed OCPs for the following uses: acne (95.8% [69/72]), concomitant treatment with teratogenic medication (48.6% [35/72]), PCOS (34.7% [25/72]), hirsutism (26.4% [19/72]), androgenetic alopecia (19.4% [14/72]), SAHA (seborrhea, acne, hirsutism, alopecia) syndrome (12.5% [9/72]), and HAIR-AN (hyperandrogenism, insulin resistance, acanthosis nigricans) syndrome (11.1% [8/72]). For teratogenic medications, dermatologists prescribing OCPs did so with isotretinoin (77.8% [56/72]), spironolactone (73.6% [53/72]), tetracycline antibiotics (37.5% [27/72]), and other (34.7% [25/72]).

Of dermatologists prescribing OCPs for acne, frequency included often (19% [13/69]), sometimes (45% [31/69]), and rarely (36% [25/69]). The most frequently prescribed OCPs included Ortho Tri-Cyclen (Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc)(80% [55/69]), Yaz (Bayer)(64% [44/69]), and Estrostep (Warner Chilcott)(19% [13/69]). Fill-in responses included Desogen (Merck & Co, Inc)(3/69 [4%]), Alesse (Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Inc)(3/69 [4%]), Lutera (Watson Pharma, Inc)(1/69 [1%]), Loestrin (Warner Chilcott)(1/69 [1%]), and Yasmin (Bayer)(1/69 [1%]).

In univariate regressions, graduation from medical school in 1997 or later (P=.0416), academic practice setting (P=.0130), and low-density practice setting (P=.0034) were significant predictors of prescribing OCPs. In multivariable regression, only academic practice setting (P=.0295) and low-density practice setting (P=.0050) remained significant predictors. Demographic predictors are summarized in Table 1.

Comment

Our results suggest that most dermatologists (95.4%) believe OCPs effectively treat acne; however, only 54% of respondents reported prescribing them. Academic dermatologists were more likely to prescribe OCPs than nonacademic dermatologists, possibly indicating that academic dermatologists are more familiar with the literature on the efficacy and use of OCPs. Nearly half of respondents seeing 25 or more acne patients weekly did not prescribe OCPs, suggesting a notable practice gap. Dermatologists in less dense US regions were more likely to prescribe OCPs, perhaps because dermatologists may be more likely to prescribe OCPs than refer patients in health care access–limited areas, just as primary care providers treat a broader range of conditions in low-density rural areas than urban ones.17 Exploring all dermatologists’ referral patterns for OCPs is warranted.

A strong knowledge area revealed from this study was hormonal treatment of acne in women, a vital area because appropriate patient selection is key to treatment success.8 Weaker knowledge areas included OCP contraindications and differences in VTE risk between formulations containing drospirenone and those not containing drospirenone. Only half the sample identified CDC-defined absolute contraindications, suggesting an education target for dermatologists to ensure patient safety. In contrast, respondents were conservative about relative contraindications, with most identifying deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, remote breast cancer history, and light smoking at 36 years or older as absolute contraindications. These results could reflect weighing the risk of relative contraindications against the benefit in acne, resulting in appropriately more conservative management than overall guidelines suggest. If so, it may suggest that dermatologists are adapting overall guidelines appropriately for use of OCPs in skin conditions.

Nearly all respondents knew that OCPs are associated with an increased risk for VTE. Approximately half understood that DCOCPs are associated with a greater VTE risk than other OCPs, with no difference between frequent and infrequent prescribers. Comparing these results to the findings on OCP prescribing overall, some dermatologists’ risk-benefit calculation for VTE differs from other specialties because DCOCPs have superior efficacy in acne, whereas DCOCPs have similar contraceptive efficacy to other OCPs.18 The fact that more dermatologists believed VTE to be an absolute contraindication than hypertension suggests dermatologists have a heightened awareness of VTE risk but prescribe DCOCPs for acne despite it.

Most OCP prescribers felt very comfortable selecting good candidates for OCPs (55.5%) and counseling on treatment initiation (45.8%) and side effects (48.6%). Only 22.2%, by contrast, were very comfortable managing side effects. This finding likely reflects the notion that VTEs are not most appropriately managed by a dermatologist. Exploring if a greater comfort level in managing side effects would make dermatologists more likely to prescribe OCPs is worthwhile. Additionally, exploring why many dermatologists do not prescribe OCPs despite believing they are effective for acne is warranted.

Study limitations included the use of convenience sampling. Additionally, our study did not investigate dermatologists’ reasons for not prescribing OCPs.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates that dermatologists believe OCPs effectively treat acne in women and that most dermatologists prescribing OCPs do so for acne treatment. Academic practice setting was associated with higher odds of prescribing OCPs than a nonacademic setting, but the number of weekly acne patients did not impact the likelihood of prescribing OCPs, which suggests a treatment gap warranting education efforts for dermatologists in nonacademic settings seeing many acne patients. Our study also suggests that awareness of the increased risk for VTE associated with DCOCPs is not associated with lower likelihood of prescribing DCOCPs, suggesting dermatologists may find greater treatment efficacy to be worth the higher risk.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the Department of Dermatology at the Weill Cornell College of Medicine (New York, New York) for providing funding to complete this study. We also acknowledge Paul Christos, DrPH, MS (New York, New York), and Xuming Sun, MS (New York, New York), for their assistance with the survey design. We also are indebted to numerous dermatologic professional societies for allowing the survey to be distributed to their membership.

- Kim GK, Michaels BB. Post-adolescent acne in women: more common and more clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:708-713.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. July 11, 2012:CD004425.

- Koo EB, Petersen TD, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:450-459.

- Strauss JS, Krowchuk DP, Leyden JJ, et al; American Academy of Dermatology/American Academy of Dermatology Association. Guidelines of care for acne vulgaris management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:651-663.

- Harper JC. Should dermatologists prescribe hormonal contraceptives for acne? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:452-457.

- Landis ET, Levender MM, Davis SA, et al. Isotretinoin and oral contraceptive use in female acne patients varies by physician specialty: analysis of data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:272-277.

- Lam C, Zaenglein AL. Contraceptive use in acne. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:502-515.

- Katsambas AD, Dessinioti C. Hormonal therapy for acne: why not as first line therapy? facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:17-23.

- Dragoman MV. The combined oral contraceptive pill—recent developments, risks and benefits. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:825-834.

- Thorneycroft IH, Gollnick H, Schellschmidt I. Superiority of a combined contraceptive containing drospirenone to a triphasic preparation containing norgestimate in acne treatment. Cutis. 2004;74:123-130.

- Mansour D, Verhoeven C, Sommer W, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a monophasic combined oral contraceptive containing nomegestrol acetate and 17β-oestradiol in a 24/4 regimen, in comparison to an oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol and drospirenone in a 21/7 regimen. Eur J Contracept Reproduct Health Care. 2011;16:430-443.

- Wu CQ, Grandi SM, Filion KB, et al. Drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive pills and the risk of venous and arterial thrombosis: a systematic review. BJOG. 2013;120:801-810.

- Ziller M, Rashed AN, Ziller V, et al. The prescribing of contraceptives for adolescents in German gynecologic practices in 2007 and 2011: a retrospective database analysis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:261-264.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1-86.

- United States Census Bureau. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. New York, NY: United States Department of Commerce; 2010.

- Resident Population Data—Population Density, 1910 to 2010. U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. http ://www.census.gov/2010census/data/apportionment-dens-text.php. Accessed January 9, 2017.

- Reschovsky A, Zahner SJ. Forecasting the revenues of local public health departments in the shadows of the “Great Recession.” J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22:120-128.

- Klipping C, Duijkers I, Fortier MP, et al. Contraceptive efficacy and tolerability of ethinylestradiol 20 μg/drospirenone 3 mg in a flexible extended regimen: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38:73-83.

- Kim GK, Michaels BB. Post-adolescent acne in women: more common and more clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:708-713.

- Arowojolu AO, Gallo MF, Lopez LM, et al. Combined oral contraceptive pills for treatment of acne. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. July 11, 2012:CD004425.

- Koo EB, Petersen TD, Kimball AB. Meta-analysis comparing efficacy of antibiotics versus oral contraceptives in acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:450-459.

- Strauss JS, Krowchuk DP, Leyden JJ, et al; American Academy of Dermatology/American Academy of Dermatology Association. Guidelines of care for acne vulgaris management. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:651-663.

- Harper JC. Should dermatologists prescribe hormonal contraceptives for acne? Dermatol Ther. 2009;22:452-457.

- Landis ET, Levender MM, Davis SA, et al. Isotretinoin and oral contraceptive use in female acne patients varies by physician specialty: analysis of data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. J Dermatol Treat. 2012;23:272-277.

- Lam C, Zaenglein AL. Contraceptive use in acne. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:502-515.

- Katsambas AD, Dessinioti C. Hormonal therapy for acne: why not as first line therapy? facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:17-23.

- Dragoman MV. The combined oral contraceptive pill—recent developments, risks and benefits. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;28:825-834.

- Thorneycroft IH, Gollnick H, Schellschmidt I. Superiority of a combined contraceptive containing drospirenone to a triphasic preparation containing norgestimate in acne treatment. Cutis. 2004;74:123-130.

- Mansour D, Verhoeven C, Sommer W, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a monophasic combined oral contraceptive containing nomegestrol acetate and 17β-oestradiol in a 24/4 regimen, in comparison to an oral contraceptive containing ethinylestradiol and drospirenone in a 21/7 regimen. Eur J Contracept Reproduct Health Care. 2011;16:430-443.

- Wu CQ, Grandi SM, Filion KB, et al. Drospirenone-containing oral contraceptive pills and the risk of venous and arterial thrombosis: a systematic review. BJOG. 2013;120:801-810.

- Ziller M, Rashed AN, Ziller V, et al. The prescribing of contraceptives for adolescents in German gynecologic practices in 2007 and 2011: a retrospective database analysis. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;26:261-264.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-4):1-86.

- United States Census Bureau. Census Regions and Divisions of the United States. New York, NY: United States Department of Commerce; 2010.

- Resident Population Data—Population Density, 1910 to 2010. U.S. Census Bureau; 2012. http ://www.census.gov/2010census/data/apportionment-dens-text.php. Accessed January 9, 2017.

- Reschovsky A, Zahner SJ. Forecasting the revenues of local public health departments in the shadows of the “Great Recession.” J Public Health Manag Pract. 2016;22:120-128.

- Klipping C, Duijkers I, Fortier MP, et al. Contraceptive efficacy and tolerability of ethinylestradiol 20 μg/drospirenone 3 mg in a flexible extended regimen: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled study. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2012;38:73-83.

Practice Points

- In prior reports, oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) were found to be as effective as systemic antibiotics in reducing acne lesion counts at 6 months of treatment.

- Most dermatologists have prescribed OCPs and most believed they were an effective treatment for acne in women.