User login

Antibiotic Stewardship in Acne: Practical Tips From Dr. Lorraine L. Rosamilia

What clinical signs suggest antimicrobial resistance is affecting acne treatment response, and how can dermatologists identify them early?

DR. ROSAMILIA: Antibiotic resistance is a difficult phenomenon to define clinically for acne due to many pathogenic contributors, namely the increase in sebum production stoked by hormonal changes, which further provokes Cutibacterium acnes biofilms, follicular plugs, and various inflammatory cascades. The sequence and primacy of these steps are enigmatic in each patient, therefore the role and extent of true antimicrobial therapy are debatable. Acne is more complex than other conditions that utilize antimicrobials, such as tinea corporis. In acne, lack of treatment response may be due to various factors, including long-term adherence challenges (such as inconsistent home dosing and trending complex over-the-counter [OTC] regimens), hormonal fluctuation, and confounders such as gram-negative or pityrosporum folliculitis. Therefore, determining if resistant bacteria are “causal” in acne recalcitrance or exacerbation is vague. In older patients (or younger patients with chronic conditions), proof of bacterial resistance from wound, pulmonary, or gastrointestinal studies might be available, but a typical acne patient would not present with these data.

Do you routinely rotate patients off oral antibiotics after a fixed treatment period, or is it symptom based? How do you balance the risk for disease recurrence with resistance concerns?

DR. ROSAMILIA: For my patients, the typical “triple threat” for moderate acne—oral antibiotics, topical benzoyl peroxide, and topical retinoids—still is tried and true. I typically prescribe 6 weeks of low-dose antibiotic therapy (doxycycline 50 mg daily) and arrange a telemedicine visit at 4 to 6 weeks to assess progress and adherence. Subsequently, I might substitute topical for oral antibiotics, with long-term plans to discontinue all antibiotics. In females, I might add spironolactone and/or oral contraceptive pills, and for recalcitrant or progressive acne, I would discuss isotretinoin. If the patient’s acne is under good control without antibiotics but they still experience intermittent deeper papules, I consider adding burst therapy of low-dose doxycycline for 1 week as needed, or for instance, during sports seasons. I try to maintain the lowest possible dosage of doxycycline while toeing the line between short-term antibacterial and longer-term anti-inflammatory control. In fact, I typically recommend that patients take it with their morning meal to absorb slightly less than the full 50-mg dosage, mitigate adverse effects, and increase adherence. All of these regimens include a benzoyl peroxide wash for its many anti-acne properties and in the context of this discussion to mitigate C acnes on acne-prone skin without creating antibiotic resistance.

Do you see a future for point-of-care microbiome or resistance testing in acne management?

DR. ROSAMILIA: I think we should be receptive to the evolution of these tests, and depending on the patient’s insurance coverage, efficient collection methods, and applicability to all patients, we someday may approach antimicrobial pharmacotherapy in a more personalized way. The microbiome is a broad topic with protean approaches to testing and prebiotic/probiotic supplementation, so openminded but cautious and well-studied utilization is key.

What language do you find effective when setting expectations for acne treatment that avoids overreliance on antibiotics?

DR. ROSAMILIA: I find it important to first determine the patient’s prior therapies. Many patients with acne present to dermatology after taking a full dosage of various antibiotics for broad amounts of time, and they may have experienced acne exacerbation (or at least perception of such) when the refills ran out. Also, I ask them to outline their past and current OTC regimens, which provides context for where and how the patient gets their information and advice. I like providing the patient’s next steps in written form, even telling them to tape the instructions to their bathroom mirror. It is just as vital to take time at the first office visit to explain the expected time to improvement and why acne is a multifactorial condition for which antibiotics are only part of the approach with benzoyl peroxide and retinoids.

What are your top practical tips for incoming dermatologists to practice antibiotic stewardship in acne management?

DR. ROSAMILIA: The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines recommend 3 to 4 months as the maximum threshold for systemic antibiotics for moderate to severe acne, with tetracyclines having the best evidence for efficacy and safety. The AAD recommends never utilizing these as monotherapy and always including concomitant benzoyl peroxide to avoid bacterial resistance and topicals such as retinoids to provide a bridge to a maintenance phase without antibiotics. Starting there gives trainees structure within which to build their own acne management approach and style for their patient population. Some dermatologists might prescribe middle to high antibiotic dosages at first followed by a taper or initiate low antibiotic dosages with a standard 3- to 4-month follow-up, or a bit of a hybrid of these, as outlined in my approach. As mentioned, standardized testing for resistance to guide our dosing is not mainstream. There are countless ways to apply these guardrails, consider a place for hormonal or future isotretinoin therapy, and include the many varieties of OTC and prescription acne topicals to round out a personalized regimen for each patient based on their schedule, medication intolerances, skin type, fertility plans, and lifestyle.

What’s the single most impactful change a busy dermatology clinic could make right now to reduce antibiotic overuse in acne care?

DR. ROSAMILIA: I think telemedicine or in-person check-ins at the 1- or 2-month mark are vital to the assessment of the patient’s and/or family’s understanding of the treatment schedule, their ability to procure the prescription and OTC products successfully, and their consistency in using them. This is a good opportunity to remind them that our goal is to see true acne improvement; take fewer medications, not more; and create a reality where their acne regimen is intuitive and safe.

What clinical signs suggest antimicrobial resistance is affecting acne treatment response, and how can dermatologists identify them early?

DR. ROSAMILIA: Antibiotic resistance is a difficult phenomenon to define clinically for acne due to many pathogenic contributors, namely the increase in sebum production stoked by hormonal changes, which further provokes Cutibacterium acnes biofilms, follicular plugs, and various inflammatory cascades. The sequence and primacy of these steps are enigmatic in each patient, therefore the role and extent of true antimicrobial therapy are debatable. Acne is more complex than other conditions that utilize antimicrobials, such as tinea corporis. In acne, lack of treatment response may be due to various factors, including long-term adherence challenges (such as inconsistent home dosing and trending complex over-the-counter [OTC] regimens), hormonal fluctuation, and confounders such as gram-negative or pityrosporum folliculitis. Therefore, determining if resistant bacteria are “causal” in acne recalcitrance or exacerbation is vague. In older patients (or younger patients with chronic conditions), proof of bacterial resistance from wound, pulmonary, or gastrointestinal studies might be available, but a typical acne patient would not present with these data.

Do you routinely rotate patients off oral antibiotics after a fixed treatment period, or is it symptom based? How do you balance the risk for disease recurrence with resistance concerns?

DR. ROSAMILIA: For my patients, the typical “triple threat” for moderate acne—oral antibiotics, topical benzoyl peroxide, and topical retinoids—still is tried and true. I typically prescribe 6 weeks of low-dose antibiotic therapy (doxycycline 50 mg daily) and arrange a telemedicine visit at 4 to 6 weeks to assess progress and adherence. Subsequently, I might substitute topical for oral antibiotics, with long-term plans to discontinue all antibiotics. In females, I might add spironolactone and/or oral contraceptive pills, and for recalcitrant or progressive acne, I would discuss isotretinoin. If the patient’s acne is under good control without antibiotics but they still experience intermittent deeper papules, I consider adding burst therapy of low-dose doxycycline for 1 week as needed, or for instance, during sports seasons. I try to maintain the lowest possible dosage of doxycycline while toeing the line between short-term antibacterial and longer-term anti-inflammatory control. In fact, I typically recommend that patients take it with their morning meal to absorb slightly less than the full 50-mg dosage, mitigate adverse effects, and increase adherence. All of these regimens include a benzoyl peroxide wash for its many anti-acne properties and in the context of this discussion to mitigate C acnes on acne-prone skin without creating antibiotic resistance.

Do you see a future for point-of-care microbiome or resistance testing in acne management?

DR. ROSAMILIA: I think we should be receptive to the evolution of these tests, and depending on the patient’s insurance coverage, efficient collection methods, and applicability to all patients, we someday may approach antimicrobial pharmacotherapy in a more personalized way. The microbiome is a broad topic with protean approaches to testing and prebiotic/probiotic supplementation, so openminded but cautious and well-studied utilization is key.

What language do you find effective when setting expectations for acne treatment that avoids overreliance on antibiotics?

DR. ROSAMILIA: I find it important to first determine the patient’s prior therapies. Many patients with acne present to dermatology after taking a full dosage of various antibiotics for broad amounts of time, and they may have experienced acne exacerbation (or at least perception of such) when the refills ran out. Also, I ask them to outline their past and current OTC regimens, which provides context for where and how the patient gets their information and advice. I like providing the patient’s next steps in written form, even telling them to tape the instructions to their bathroom mirror. It is just as vital to take time at the first office visit to explain the expected time to improvement and why acne is a multifactorial condition for which antibiotics are only part of the approach with benzoyl peroxide and retinoids.

What are your top practical tips for incoming dermatologists to practice antibiotic stewardship in acne management?

DR. ROSAMILIA: The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines recommend 3 to 4 months as the maximum threshold for systemic antibiotics for moderate to severe acne, with tetracyclines having the best evidence for efficacy and safety. The AAD recommends never utilizing these as monotherapy and always including concomitant benzoyl peroxide to avoid bacterial resistance and topicals such as retinoids to provide a bridge to a maintenance phase without antibiotics. Starting there gives trainees structure within which to build their own acne management approach and style for their patient population. Some dermatologists might prescribe middle to high antibiotic dosages at first followed by a taper or initiate low antibiotic dosages with a standard 3- to 4-month follow-up, or a bit of a hybrid of these, as outlined in my approach. As mentioned, standardized testing for resistance to guide our dosing is not mainstream. There are countless ways to apply these guardrails, consider a place for hormonal or future isotretinoin therapy, and include the many varieties of OTC and prescription acne topicals to round out a personalized regimen for each patient based on their schedule, medication intolerances, skin type, fertility plans, and lifestyle.

What’s the single most impactful change a busy dermatology clinic could make right now to reduce antibiotic overuse in acne care?

DR. ROSAMILIA: I think telemedicine or in-person check-ins at the 1- or 2-month mark are vital to the assessment of the patient’s and/or family’s understanding of the treatment schedule, their ability to procure the prescription and OTC products successfully, and their consistency in using them. This is a good opportunity to remind them that our goal is to see true acne improvement; take fewer medications, not more; and create a reality where their acne regimen is intuitive and safe.

What clinical signs suggest antimicrobial resistance is affecting acne treatment response, and how can dermatologists identify them early?

DR. ROSAMILIA: Antibiotic resistance is a difficult phenomenon to define clinically for acne due to many pathogenic contributors, namely the increase in sebum production stoked by hormonal changes, which further provokes Cutibacterium acnes biofilms, follicular plugs, and various inflammatory cascades. The sequence and primacy of these steps are enigmatic in each patient, therefore the role and extent of true antimicrobial therapy are debatable. Acne is more complex than other conditions that utilize antimicrobials, such as tinea corporis. In acne, lack of treatment response may be due to various factors, including long-term adherence challenges (such as inconsistent home dosing and trending complex over-the-counter [OTC] regimens), hormonal fluctuation, and confounders such as gram-negative or pityrosporum folliculitis. Therefore, determining if resistant bacteria are “causal” in acne recalcitrance or exacerbation is vague. In older patients (or younger patients with chronic conditions), proof of bacterial resistance from wound, pulmonary, or gastrointestinal studies might be available, but a typical acne patient would not present with these data.

Do you routinely rotate patients off oral antibiotics after a fixed treatment period, or is it symptom based? How do you balance the risk for disease recurrence with resistance concerns?

DR. ROSAMILIA: For my patients, the typical “triple threat” for moderate acne—oral antibiotics, topical benzoyl peroxide, and topical retinoids—still is tried and true. I typically prescribe 6 weeks of low-dose antibiotic therapy (doxycycline 50 mg daily) and arrange a telemedicine visit at 4 to 6 weeks to assess progress and adherence. Subsequently, I might substitute topical for oral antibiotics, with long-term plans to discontinue all antibiotics. In females, I might add spironolactone and/or oral contraceptive pills, and for recalcitrant or progressive acne, I would discuss isotretinoin. If the patient’s acne is under good control without antibiotics but they still experience intermittent deeper papules, I consider adding burst therapy of low-dose doxycycline for 1 week as needed, or for instance, during sports seasons. I try to maintain the lowest possible dosage of doxycycline while toeing the line between short-term antibacterial and longer-term anti-inflammatory control. In fact, I typically recommend that patients take it with their morning meal to absorb slightly less than the full 50-mg dosage, mitigate adverse effects, and increase adherence. All of these regimens include a benzoyl peroxide wash for its many anti-acne properties and in the context of this discussion to mitigate C acnes on acne-prone skin without creating antibiotic resistance.

Do you see a future for point-of-care microbiome or resistance testing in acne management?

DR. ROSAMILIA: I think we should be receptive to the evolution of these tests, and depending on the patient’s insurance coverage, efficient collection methods, and applicability to all patients, we someday may approach antimicrobial pharmacotherapy in a more personalized way. The microbiome is a broad topic with protean approaches to testing and prebiotic/probiotic supplementation, so openminded but cautious and well-studied utilization is key.

What language do you find effective when setting expectations for acne treatment that avoids overreliance on antibiotics?

DR. ROSAMILIA: I find it important to first determine the patient’s prior therapies. Many patients with acne present to dermatology after taking a full dosage of various antibiotics for broad amounts of time, and they may have experienced acne exacerbation (or at least perception of such) when the refills ran out. Also, I ask them to outline their past and current OTC regimens, which provides context for where and how the patient gets their information and advice. I like providing the patient’s next steps in written form, even telling them to tape the instructions to their bathroom mirror. It is just as vital to take time at the first office visit to explain the expected time to improvement and why acne is a multifactorial condition for which antibiotics are only part of the approach with benzoyl peroxide and retinoids.

What are your top practical tips for incoming dermatologists to practice antibiotic stewardship in acne management?

DR. ROSAMILIA: The American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines recommend 3 to 4 months as the maximum threshold for systemic antibiotics for moderate to severe acne, with tetracyclines having the best evidence for efficacy and safety. The AAD recommends never utilizing these as monotherapy and always including concomitant benzoyl peroxide to avoid bacterial resistance and topicals such as retinoids to provide a bridge to a maintenance phase without antibiotics. Starting there gives trainees structure within which to build their own acne management approach and style for their patient population. Some dermatologists might prescribe middle to high antibiotic dosages at first followed by a taper or initiate low antibiotic dosages with a standard 3- to 4-month follow-up, or a bit of a hybrid of these, as outlined in my approach. As mentioned, standardized testing for resistance to guide our dosing is not mainstream. There are countless ways to apply these guardrails, consider a place for hormonal or future isotretinoin therapy, and include the many varieties of OTC and prescription acne topicals to round out a personalized regimen for each patient based on their schedule, medication intolerances, skin type, fertility plans, and lifestyle.

What’s the single most impactful change a busy dermatology clinic could make right now to reduce antibiotic overuse in acne care?

DR. ROSAMILIA: I think telemedicine or in-person check-ins at the 1- or 2-month mark are vital to the assessment of the patient’s and/or family’s understanding of the treatment schedule, their ability to procure the prescription and OTC products successfully, and their consistency in using them. This is a good opportunity to remind them that our goal is to see true acne improvement; take fewer medications, not more; and create a reality where their acne regimen is intuitive and safe.

Path of Least Resistance: Guidance for Antibiotic Stewardship in Acne

Path of Least Resistance: Guidance for Antibiotic Stewardship in Acne

Dermatologists have long relied on oral antibiotics to manage moderate to severe acne1-4; however, it is critical to reassess how these medications are used in clinical practice as concerns about antibiotic resistance grow.5 The question is not whether antibiotics are effective for acne treatment—we know they are—but how to optimize their use to balance clinical benefit with responsible prescribing. Resistance in Cutibacterium acnes has been well documented in laboratory settings, but clinical treatment failure due to resistance remains rare and difficult to quantify.6,7 Still, minimizing unnecessary exposure is good clinical practice. Whether antibiotic resistance ultimately proves to drive clinical failure or remains largely theoretical, stewardship safeguards future treatment options.

In this article, we present a practical, expert-based framework aligned with American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines to support responsible antibiotic use in acne management. Seven prescribing principles are outlined to help clinicians maintain efficacy while minimizing resistance risk. Mechanisms of resistance in C acnes and broader microbiome impacts also are discussed.

MECHANISMS OF RESISTANCE IN ACNE THERAPY

Antibiotic resistance in acne primarily involves C acnes and arises through selective pressure from prolonged or subtherapeutic antibiotic exposure. Resistance mechanisms include point mutations in ribosomal binding sites, leading to decreased binding affinity for tetracyclines and macrolides as well as efflux pump activation and biofilm formation.8,9 Over time, resistant strains may proliferate and outcompete susceptible populations, potentially contributing to reduced clinical efficacy. Importantly, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics may disrupt the skin and gut microbiota, promoting resistance among nontarget organisms.5 These concerns underscore the importance of limiting antibiotic use to appropriate indications, combining antibiotics with adjunctive nonantibiotic therapies, and avoiding monotherapy.

PRESCRIBING PRINCIPLES FOR RESPONSIBLE ORAL ANTIBIOTIC USE IN ACNE

The following principles are derived from our clinical experience and are aligned with AAD guidelines on acne treatment.10 This practical framework supports safe, effective, and streamlined prescribing.

Reserve Oral Antibiotics for Appropriate Cases

Oral antibiotics should be considered for patients with moderate to severe inflammatory acne when rapid anti-inflammatory control is needed. They are not indicated for comedonal or mild papulopustular acne. Before initiating treatment, clinicians should weigh the potential benefits against the risks associated with antibiotic exposure, including resistance and microbiome disruption.

Combine Oral Antibiotics With Topical Retinoids

Oral antibiotics should not be used as monotherapy. Topical retinoids should be initiated concurrently with oral antibiotics to maximize anti-inflammatory benefit, support transition to maintenance therapy, and reduce risk for resistance.

Consider Adding an Adjunctive Topical Antimicrobial Agent

Adjunctive topical antimicrobials can help reduce bacterial load. Benzoyl peroxide remains a first-line option due to its bactericidal activity and lack of resistance induction; however, recent product recalls involving benzene contamination may have raised safety concerns among some clinicians and patients.11,12 While no definitive harm has been established, alternative topical agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (eg, azelaic acid) may be used based on shared decision-making, tolerability, cost, access, and patient preference. Use of topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, erythromycin) as monotherapy is discouraged due to their higher resistance potential, which is consistent with AAD guidance.

Limit Treatment Duration to 12 Weeks or Less

Antibiotic use should be time limited, with discontinuation ideally within 8 to 12 weeks as clinical improvement is demonstrated. Repeated or prolonged courses should be avoided to minimize risk for resistance.

Simplify Treatment Regimens to Enhance Adherence

Regimen simplicity improves adherence, especially in adolescents. A two-agent regimen of an oral antibiotic and a topical retinoid typically is sufficient during the induction phase.13,14

Select Narrower-Spectrum Antibiotics When Feasible

Using a narrower-spectrum antibiotic may help minimize disruption to nontarget microbiota.15,16 Sarecycline has shown narrower in vitro activity within the tetracycline class,17,18 though clinical decisions should be informed by access, availability, and cost. Regardless of the agent used (eg, doxycycline, minocycline, or sarecycline), all antibiotics should be used judiciously and for the shortest effective duration.

Use Systemic Nonantibiotic Therapies When Appropriate

If there is inadequate response to oral antibiotic therapy, consider switching to systemic nonantibiotic options. Hormonal therapy may be appropriate for select female patients. Oral isotretinoin should be considered for patients with severe, recalcitrant, or scarring acne. Cycling between antibiotic classes without clear benefit is discouraged.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Oral antibiotics remain a foundational component in the management of moderate to severe acne; however, their use must be intentional, time limited, and guided by best practices to minimize the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. By adhering to the prescribing principles we have outlined here, which are rooted in clinical expertise and consistent with AAD guidelines, dermatologists can preserve antibiotic efficacy, optimize patient outcomes, and reduce long-term microbiologic risks. Stewardship is not about withholding treatment; it is about optimizing care today to protect treatment options for tomorrow.

- Bhate K, Williams H. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:474-485.

- Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:290-297.

- Grada A, Armstrong A, Bunick C, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic use for acne treatment: a retrospective, population-based study in the United States, 2014 to 2016. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:265-270.

- Perche PO, Peck GM, Robinson L, et al. Prescribing trends for acne vulgaris visits in the United States. Antibiotics. 2023;12:269.

- Karadag A, Aslan Kayıran M, Wu CY, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: changes, consequences and concerns. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:73-78.

- Eady AE, Cove JH, Layton AM. Is antibiotic resistance in cutaneous propionibacteria clinically relevant? implications of resistance for acne patients and prescribers. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:813-831.

- Eady EA, Cove J, Holland K, et al. Erythromycin resistant propionibacteria in antibiotic treated acne patients: association with therapeutic failure. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:51-57.

- Grossman TH. Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:a025387.

- Kayiran M AS, Karadag AS, Al-Khuzaei S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: mechanisms, complications and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:813-819.

- Reynolds RV, Yeung H, Cheng CE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1006-1035.

- Kucera K, Zenzola N, Hudspeth A, et al. Benzoyl peroxide drug products form benzene. Environ Health Perspect. 2024;132:037702.

- Kucera K, Zenzola N, Hudspeth A, et al. Evaluation of benzene presence and formation in benzoyl peroxide drug products. J Invest Dermatol. 2025;145:1147-1154.E11.

- Grada A, Perche P, Feldman S. Adherence and persistence to acne medications: a population-based claims database analysis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:758-764.<.li>

- Anderson KL, Dothard EH, Huang KE, et al. Frequency of primary nonadherence to acne treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:623-626.

- Grada A, Bunick CG. Spectrum of antibiotic activity and its relevance to the microbiome. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:E215357-E215357.

- Francino M. Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Front Microbiol. 2016;6:164577.

- Moura IB, Grada A, Spittal W, et al. Profiling the effects of systemic antibiotics for acne, including the narrow-spectrum antibiotic sarecycline, on the human gut microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:901911.

- Zhanel G, Critchley I, Lin L-Y, et al. Microbiological profile of sarecycline, a novel targeted spectrum tetracycline for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:1297-1318.

Dermatologists have long relied on oral antibiotics to manage moderate to severe acne1-4; however, it is critical to reassess how these medications are used in clinical practice as concerns about antibiotic resistance grow.5 The question is not whether antibiotics are effective for acne treatment—we know they are—but how to optimize their use to balance clinical benefit with responsible prescribing. Resistance in Cutibacterium acnes has been well documented in laboratory settings, but clinical treatment failure due to resistance remains rare and difficult to quantify.6,7 Still, minimizing unnecessary exposure is good clinical practice. Whether antibiotic resistance ultimately proves to drive clinical failure or remains largely theoretical, stewardship safeguards future treatment options.

In this article, we present a practical, expert-based framework aligned with American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines to support responsible antibiotic use in acne management. Seven prescribing principles are outlined to help clinicians maintain efficacy while minimizing resistance risk. Mechanisms of resistance in C acnes and broader microbiome impacts also are discussed.

MECHANISMS OF RESISTANCE IN ACNE THERAPY

Antibiotic resistance in acne primarily involves C acnes and arises through selective pressure from prolonged or subtherapeutic antibiotic exposure. Resistance mechanisms include point mutations in ribosomal binding sites, leading to decreased binding affinity for tetracyclines and macrolides as well as efflux pump activation and biofilm formation.8,9 Over time, resistant strains may proliferate and outcompete susceptible populations, potentially contributing to reduced clinical efficacy. Importantly, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics may disrupt the skin and gut microbiota, promoting resistance among nontarget organisms.5 These concerns underscore the importance of limiting antibiotic use to appropriate indications, combining antibiotics with adjunctive nonantibiotic therapies, and avoiding monotherapy.

PRESCRIBING PRINCIPLES FOR RESPONSIBLE ORAL ANTIBIOTIC USE IN ACNE

The following principles are derived from our clinical experience and are aligned with AAD guidelines on acne treatment.10 This practical framework supports safe, effective, and streamlined prescribing.

Reserve Oral Antibiotics for Appropriate Cases

Oral antibiotics should be considered for patients with moderate to severe inflammatory acne when rapid anti-inflammatory control is needed. They are not indicated for comedonal or mild papulopustular acne. Before initiating treatment, clinicians should weigh the potential benefits against the risks associated with antibiotic exposure, including resistance and microbiome disruption.

Combine Oral Antibiotics With Topical Retinoids

Oral antibiotics should not be used as monotherapy. Topical retinoids should be initiated concurrently with oral antibiotics to maximize anti-inflammatory benefit, support transition to maintenance therapy, and reduce risk for resistance.

Consider Adding an Adjunctive Topical Antimicrobial Agent

Adjunctive topical antimicrobials can help reduce bacterial load. Benzoyl peroxide remains a first-line option due to its bactericidal activity and lack of resistance induction; however, recent product recalls involving benzene contamination may have raised safety concerns among some clinicians and patients.11,12 While no definitive harm has been established, alternative topical agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (eg, azelaic acid) may be used based on shared decision-making, tolerability, cost, access, and patient preference. Use of topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, erythromycin) as monotherapy is discouraged due to their higher resistance potential, which is consistent with AAD guidance.

Limit Treatment Duration to 12 Weeks or Less

Antibiotic use should be time limited, with discontinuation ideally within 8 to 12 weeks as clinical improvement is demonstrated. Repeated or prolonged courses should be avoided to minimize risk for resistance.

Simplify Treatment Regimens to Enhance Adherence

Regimen simplicity improves adherence, especially in adolescents. A two-agent regimen of an oral antibiotic and a topical retinoid typically is sufficient during the induction phase.13,14

Select Narrower-Spectrum Antibiotics When Feasible

Using a narrower-spectrum antibiotic may help minimize disruption to nontarget microbiota.15,16 Sarecycline has shown narrower in vitro activity within the tetracycline class,17,18 though clinical decisions should be informed by access, availability, and cost. Regardless of the agent used (eg, doxycycline, minocycline, or sarecycline), all antibiotics should be used judiciously and for the shortest effective duration.

Use Systemic Nonantibiotic Therapies When Appropriate

If there is inadequate response to oral antibiotic therapy, consider switching to systemic nonantibiotic options. Hormonal therapy may be appropriate for select female patients. Oral isotretinoin should be considered for patients with severe, recalcitrant, or scarring acne. Cycling between antibiotic classes without clear benefit is discouraged.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Oral antibiotics remain a foundational component in the management of moderate to severe acne; however, their use must be intentional, time limited, and guided by best practices to minimize the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. By adhering to the prescribing principles we have outlined here, which are rooted in clinical expertise and consistent with AAD guidelines, dermatologists can preserve antibiotic efficacy, optimize patient outcomes, and reduce long-term microbiologic risks. Stewardship is not about withholding treatment; it is about optimizing care today to protect treatment options for tomorrow.

Dermatologists have long relied on oral antibiotics to manage moderate to severe acne1-4; however, it is critical to reassess how these medications are used in clinical practice as concerns about antibiotic resistance grow.5 The question is not whether antibiotics are effective for acne treatment—we know they are—but how to optimize their use to balance clinical benefit with responsible prescribing. Resistance in Cutibacterium acnes has been well documented in laboratory settings, but clinical treatment failure due to resistance remains rare and difficult to quantify.6,7 Still, minimizing unnecessary exposure is good clinical practice. Whether antibiotic resistance ultimately proves to drive clinical failure or remains largely theoretical, stewardship safeguards future treatment options.

In this article, we present a practical, expert-based framework aligned with American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) guidelines to support responsible antibiotic use in acne management. Seven prescribing principles are outlined to help clinicians maintain efficacy while minimizing resistance risk. Mechanisms of resistance in C acnes and broader microbiome impacts also are discussed.

MECHANISMS OF RESISTANCE IN ACNE THERAPY

Antibiotic resistance in acne primarily involves C acnes and arises through selective pressure from prolonged or subtherapeutic antibiotic exposure. Resistance mechanisms include point mutations in ribosomal binding sites, leading to decreased binding affinity for tetracyclines and macrolides as well as efflux pump activation and biofilm formation.8,9 Over time, resistant strains may proliferate and outcompete susceptible populations, potentially contributing to reduced clinical efficacy. Importantly, the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics may disrupt the skin and gut microbiota, promoting resistance among nontarget organisms.5 These concerns underscore the importance of limiting antibiotic use to appropriate indications, combining antibiotics with adjunctive nonantibiotic therapies, and avoiding monotherapy.

PRESCRIBING PRINCIPLES FOR RESPONSIBLE ORAL ANTIBIOTIC USE IN ACNE

The following principles are derived from our clinical experience and are aligned with AAD guidelines on acne treatment.10 This practical framework supports safe, effective, and streamlined prescribing.

Reserve Oral Antibiotics for Appropriate Cases

Oral antibiotics should be considered for patients with moderate to severe inflammatory acne when rapid anti-inflammatory control is needed. They are not indicated for comedonal or mild papulopustular acne. Before initiating treatment, clinicians should weigh the potential benefits against the risks associated with antibiotic exposure, including resistance and microbiome disruption.

Combine Oral Antibiotics With Topical Retinoids

Oral antibiotics should not be used as monotherapy. Topical retinoids should be initiated concurrently with oral antibiotics to maximize anti-inflammatory benefit, support transition to maintenance therapy, and reduce risk for resistance.

Consider Adding an Adjunctive Topical Antimicrobial Agent

Adjunctive topical antimicrobials can help reduce bacterial load. Benzoyl peroxide remains a first-line option due to its bactericidal activity and lack of resistance induction; however, recent product recalls involving benzene contamination may have raised safety concerns among some clinicians and patients.11,12 While no definitive harm has been established, alternative topical agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (eg, azelaic acid) may be used based on shared decision-making, tolerability, cost, access, and patient preference. Use of topical antibiotics (eg, clindamycin, erythromycin) as monotherapy is discouraged due to their higher resistance potential, which is consistent with AAD guidance.

Limit Treatment Duration to 12 Weeks or Less

Antibiotic use should be time limited, with discontinuation ideally within 8 to 12 weeks as clinical improvement is demonstrated. Repeated or prolonged courses should be avoided to minimize risk for resistance.

Simplify Treatment Regimens to Enhance Adherence

Regimen simplicity improves adherence, especially in adolescents. A two-agent regimen of an oral antibiotic and a topical retinoid typically is sufficient during the induction phase.13,14

Select Narrower-Spectrum Antibiotics When Feasible

Using a narrower-spectrum antibiotic may help minimize disruption to nontarget microbiota.15,16 Sarecycline has shown narrower in vitro activity within the tetracycline class,17,18 though clinical decisions should be informed by access, availability, and cost. Regardless of the agent used (eg, doxycycline, minocycline, or sarecycline), all antibiotics should be used judiciously and for the shortest effective duration.

Use Systemic Nonantibiotic Therapies When Appropriate

If there is inadequate response to oral antibiotic therapy, consider switching to systemic nonantibiotic options. Hormonal therapy may be appropriate for select female patients. Oral isotretinoin should be considered for patients with severe, recalcitrant, or scarring acne. Cycling between antibiotic classes without clear benefit is discouraged.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Oral antibiotics remain a foundational component in the management of moderate to severe acne; however, their use must be intentional, time limited, and guided by best practices to minimize the emergence of antimicrobial resistance. By adhering to the prescribing principles we have outlined here, which are rooted in clinical expertise and consistent with AAD guidelines, dermatologists can preserve antibiotic efficacy, optimize patient outcomes, and reduce long-term microbiologic risks. Stewardship is not about withholding treatment; it is about optimizing care today to protect treatment options for tomorrow.

- Bhate K, Williams H. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:474-485.

- Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:290-297.

- Grada A, Armstrong A, Bunick C, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic use for acne treatment: a retrospective, population-based study in the United States, 2014 to 2016. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:265-270.

- Perche PO, Peck GM, Robinson L, et al. Prescribing trends for acne vulgaris visits in the United States. Antibiotics. 2023;12:269.

- Karadag A, Aslan Kayıran M, Wu CY, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: changes, consequences and concerns. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:73-78.

- Eady AE, Cove JH, Layton AM. Is antibiotic resistance in cutaneous propionibacteria clinically relevant? implications of resistance for acne patients and prescribers. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:813-831.

- Eady EA, Cove J, Holland K, et al. Erythromycin resistant propionibacteria in antibiotic treated acne patients: association with therapeutic failure. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:51-57.

- Grossman TH. Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:a025387.

- Kayiran M AS, Karadag AS, Al-Khuzaei S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: mechanisms, complications and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:813-819.

- Reynolds RV, Yeung H, Cheng CE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1006-1035.

- Kucera K, Zenzola N, Hudspeth A, et al. Benzoyl peroxide drug products form benzene. Environ Health Perspect. 2024;132:037702.

- Kucera K, Zenzola N, Hudspeth A, et al. Evaluation of benzene presence and formation in benzoyl peroxide drug products. J Invest Dermatol. 2025;145:1147-1154.E11.

- Grada A, Perche P, Feldman S. Adherence and persistence to acne medications: a population-based claims database analysis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:758-764.<.li>

- Anderson KL, Dothard EH, Huang KE, et al. Frequency of primary nonadherence to acne treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:623-626.

- Grada A, Bunick CG. Spectrum of antibiotic activity and its relevance to the microbiome. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:E215357-E215357.

- Francino M. Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Front Microbiol. 2016;6:164577.

- Moura IB, Grada A, Spittal W, et al. Profiling the effects of systemic antibiotics for acne, including the narrow-spectrum antibiotic sarecycline, on the human gut microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:901911.

- Zhanel G, Critchley I, Lin L-Y, et al. Microbiological profile of sarecycline, a novel targeted spectrum tetracycline for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:1297-1318.

- Bhate K, Williams H. Epidemiology of acne vulgaris. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:474-485.

- Barbieri JS, Bhate K, Hartnett KP, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic prescription in dermatology, 2008 to 2016. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:290-297.

- Grada A, Armstrong A, Bunick C, et al. Trends in oral antibiotic use for acne treatment: a retrospective, population-based study in the United States, 2014 to 2016. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:265-270.

- Perche PO, Peck GM, Robinson L, et al. Prescribing trends for acne vulgaris visits in the United States. Antibiotics. 2023;12:269.

- Karadag A, Aslan Kayıran M, Wu CY, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: changes, consequences and concerns. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:73-78.

- Eady AE, Cove JH, Layton AM. Is antibiotic resistance in cutaneous propionibacteria clinically relevant? implications of resistance for acne patients and prescribers. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2003;4:813-831.

- Eady EA, Cove J, Holland K, et al. Erythromycin resistant propionibacteria in antibiotic treated acne patients: association with therapeutic failure. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:51-57.

- Grossman TH. Tetracycline antibiotics and resistance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2016;6:a025387.

- Kayiran M AS, Karadag AS, Al-Khuzaei S, et al. Antibiotic resistance in acne: mechanisms, complications and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21:813-819.

- Reynolds RV, Yeung H, Cheng CE, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1006-1035.

- Kucera K, Zenzola N, Hudspeth A, et al. Benzoyl peroxide drug products form benzene. Environ Health Perspect. 2024;132:037702.

- Kucera K, Zenzola N, Hudspeth A, et al. Evaluation of benzene presence and formation in benzoyl peroxide drug products. J Invest Dermatol. 2025;145:1147-1154.E11.

- Grada A, Perche P, Feldman S. Adherence and persistence to acne medications: a population-based claims database analysis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:758-764.<.li>

- Anderson KL, Dothard EH, Huang KE, et al. Frequency of primary nonadherence to acne treatment. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:623-626.

- Grada A, Bunick CG. Spectrum of antibiotic activity and its relevance to the microbiome. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:E215357-E215357.

- Francino M. Antibiotics and the human gut microbiome: dysbioses and accumulation of resistances. Front Microbiol. 2016;6:164577.

- Moura IB, Grada A, Spittal W, et al. Profiling the effects of systemic antibiotics for acne, including the narrow-spectrum antibiotic sarecycline, on the human gut microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:901911.

- Zhanel G, Critchley I, Lin L-Y, et al. Microbiological profile of sarecycline, a novel targeted spectrum tetracycline for the treatment of acne vulgaris. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019;63:1297-1318.

Path of Least Resistance: Guidance for Antibiotic Stewardship in Acne

Path of Least Resistance: Guidance for Antibiotic Stewardship in Acne

Practice Point

- Oral antibiotics remain a cornerstone in the treatment of moderate to severe acne, but growing concerns about antibiotic resistance necessitate more intentional prescribing.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome Risk in Acne Patients: Implications for Dermatologic Care

To the Editor:

Acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are both associated with microbial dysbiosis and chronic inflammation.1-3 While the prevalence of IBS among patients with acne has been examined previously,4,5 there has been limited focus on the risk for new-onset IBS following acne diagnosis. Current evidence suggests isotretinoin may be associated with a lower risk for IBS compared to oral antibiotics6; however, evidence supporting this association is limited outside these cohorts, highlighting the need for further investigation. In this large-scale study, we sought to investigate the incidence of new-onset IBS among patients with acne compared with healthy controls as well as to evaluate whether oral acne treatments (ie, oral antibiotics or isotretinoin) are associated with new-onset IBS in this population.

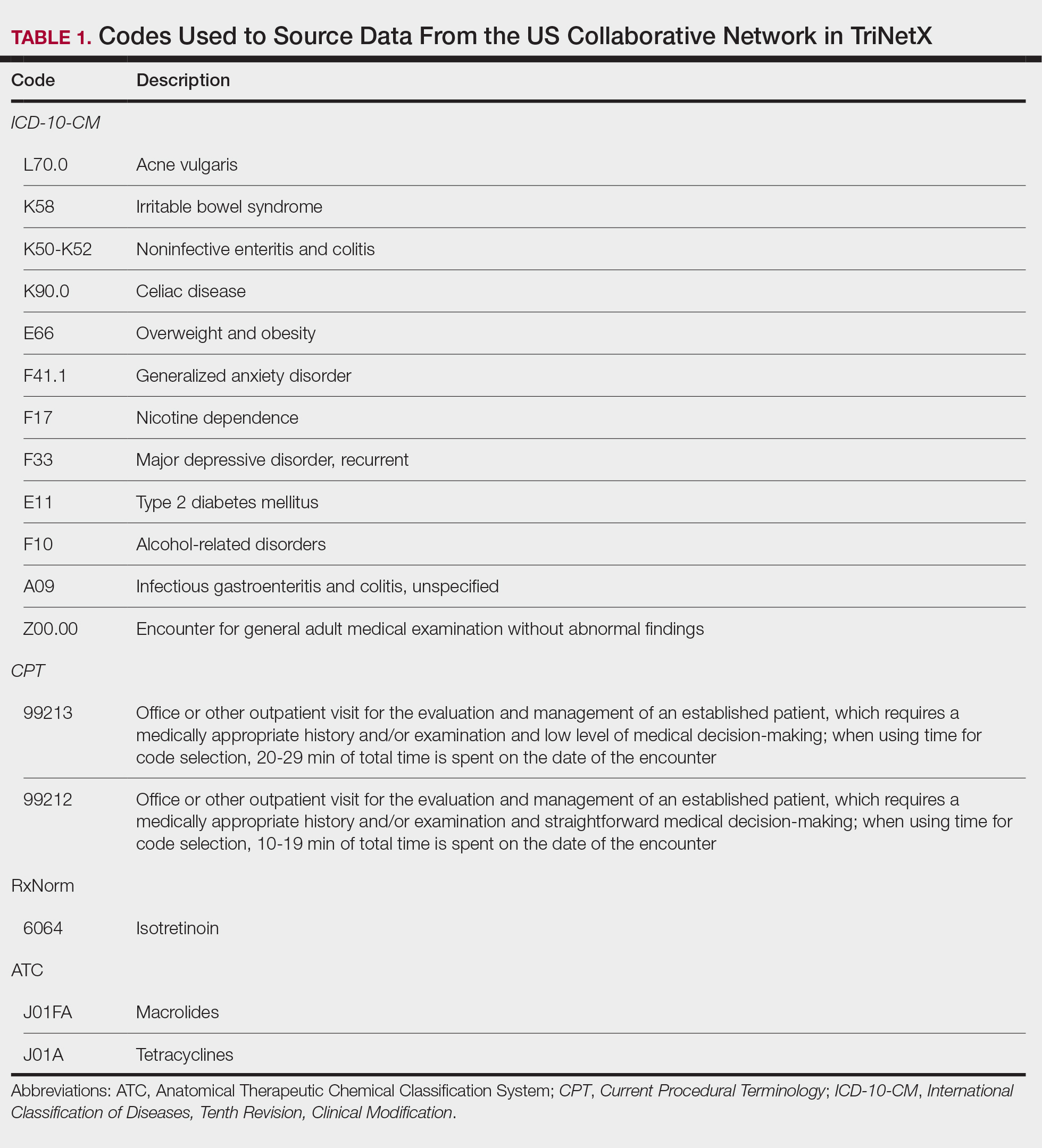

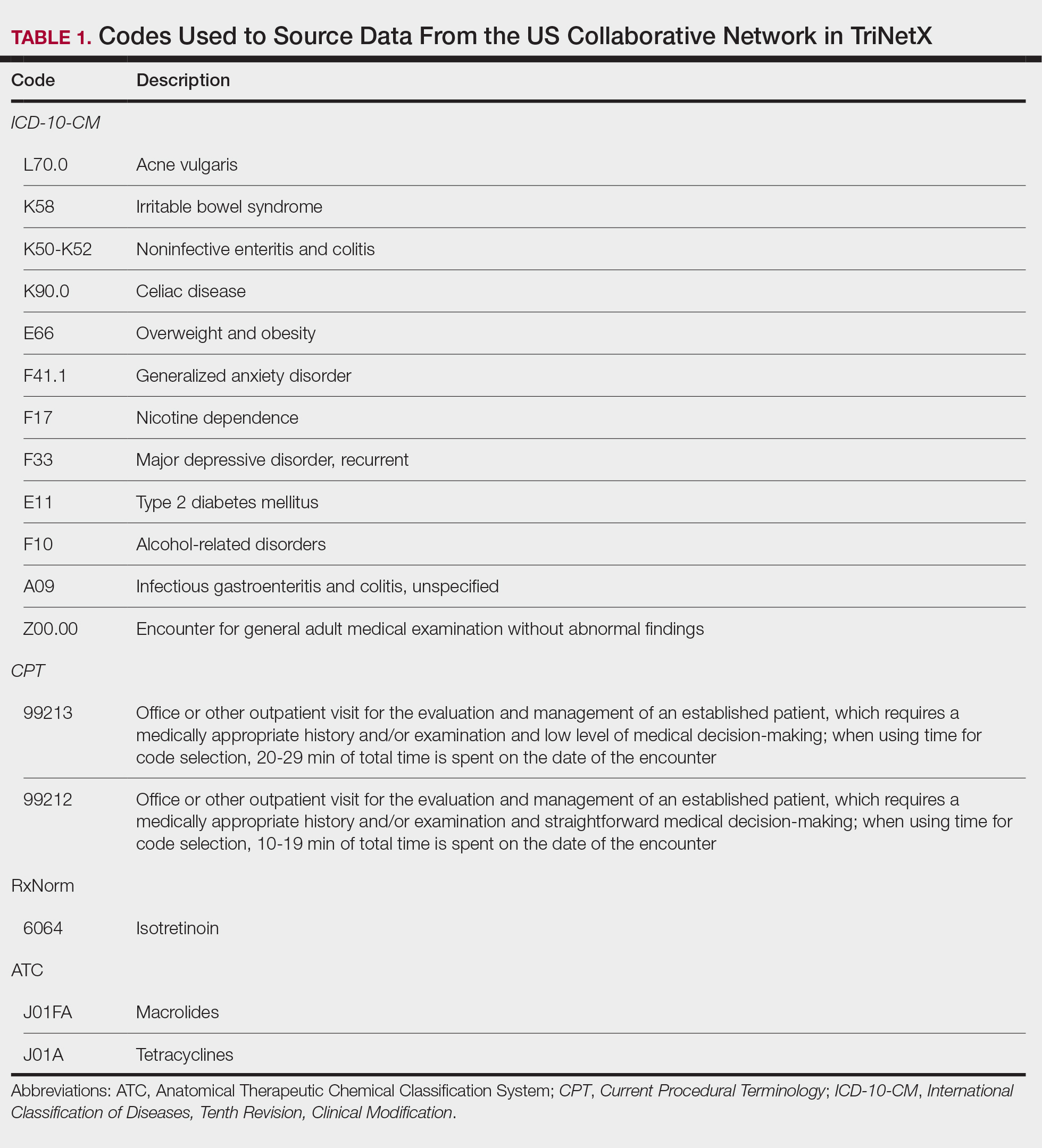

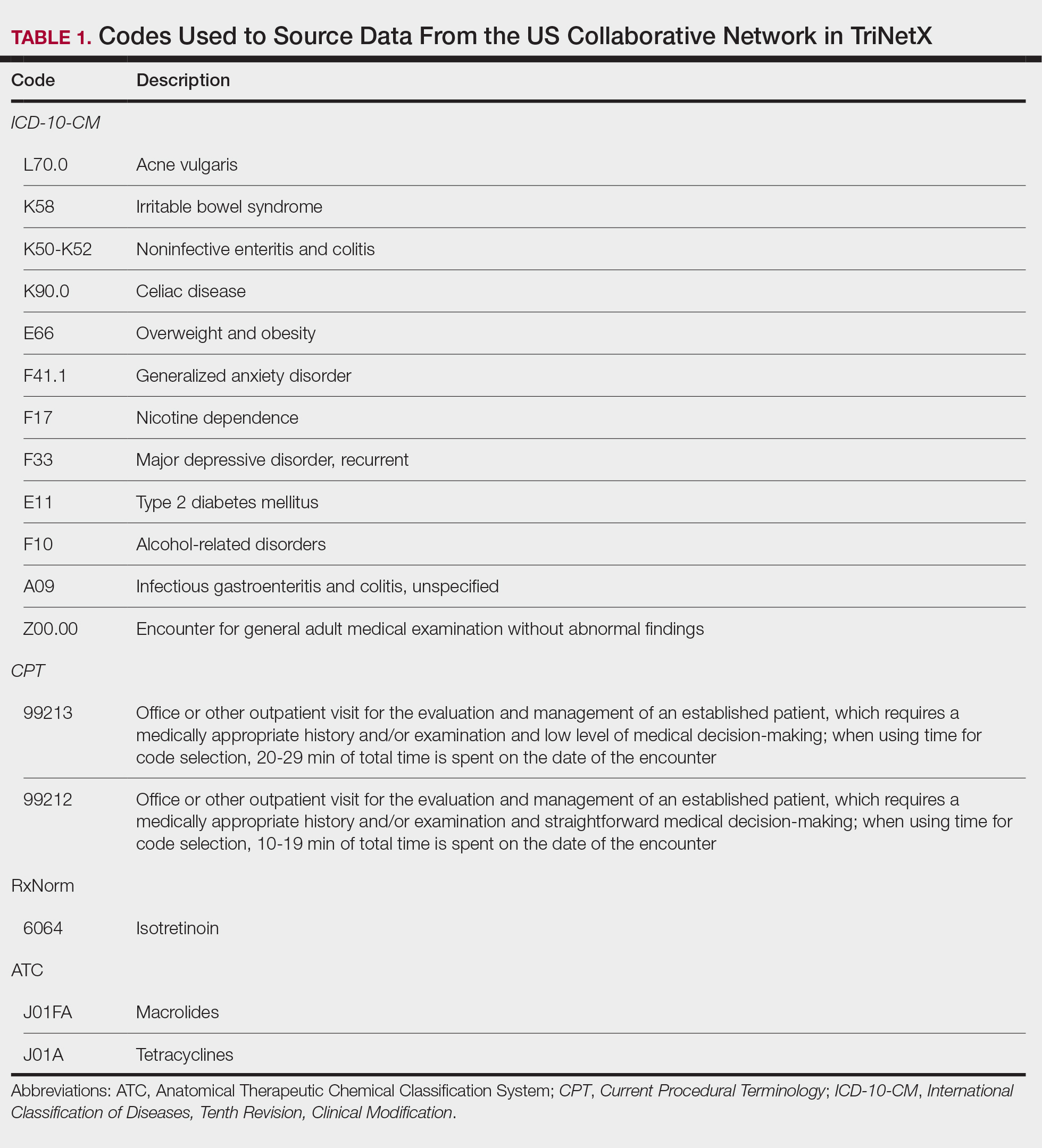

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from the US Collaborative Network in TriNetX from October 2014 to October 2024. Patients were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, Current Procedural Terminology codes, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System codes, and RxNorm codes (Table 1). These codes were selected based on prior literature review, clinical relevance, and their ability to capture diagnoses of acne and IBS as well as relevant exclusion criteria. Patients were considered eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 90 years. Individuals with a history of IBS, inflammatory bowel disease, infectious gastroenteritis, or celiac disease were excluded from our analysis.

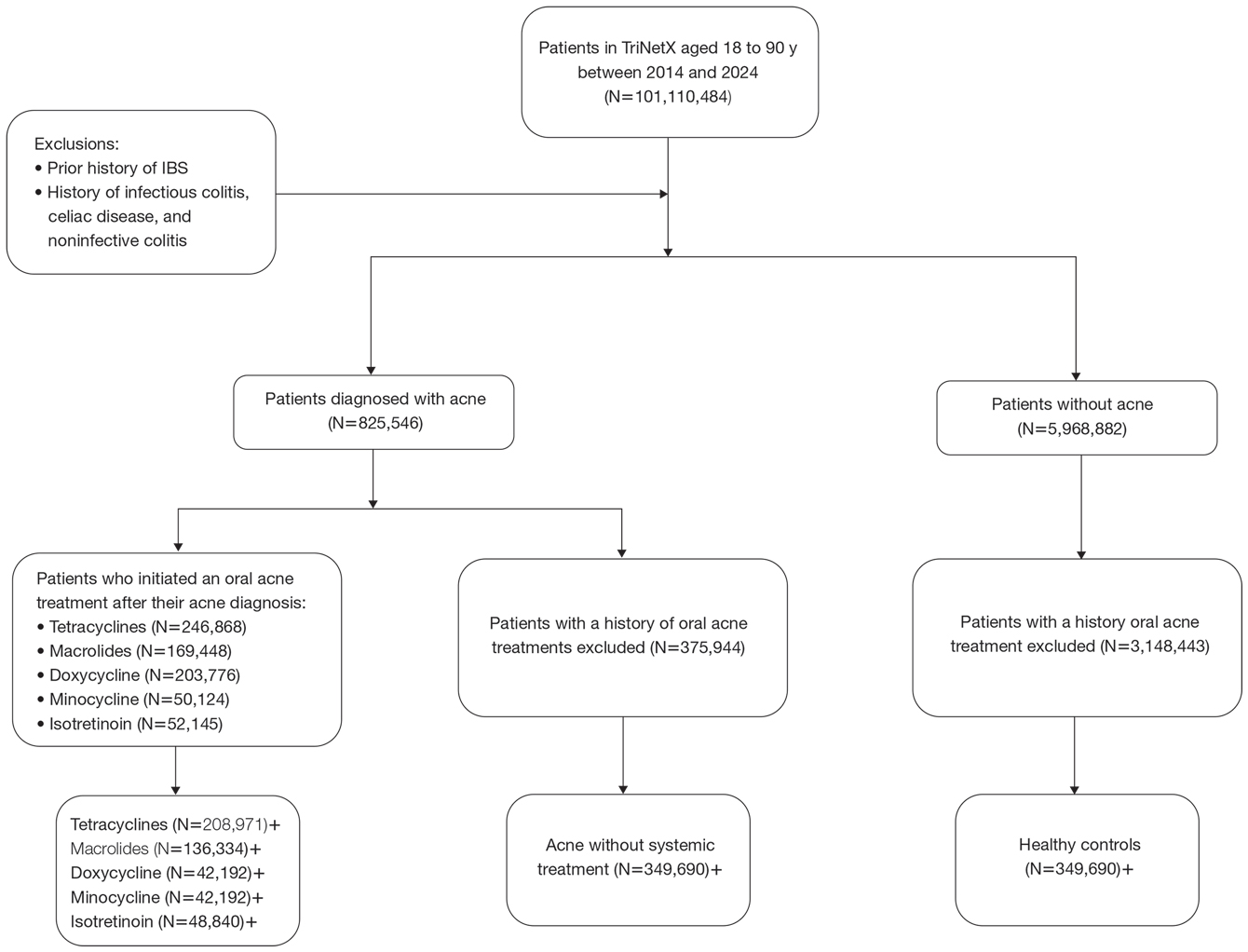

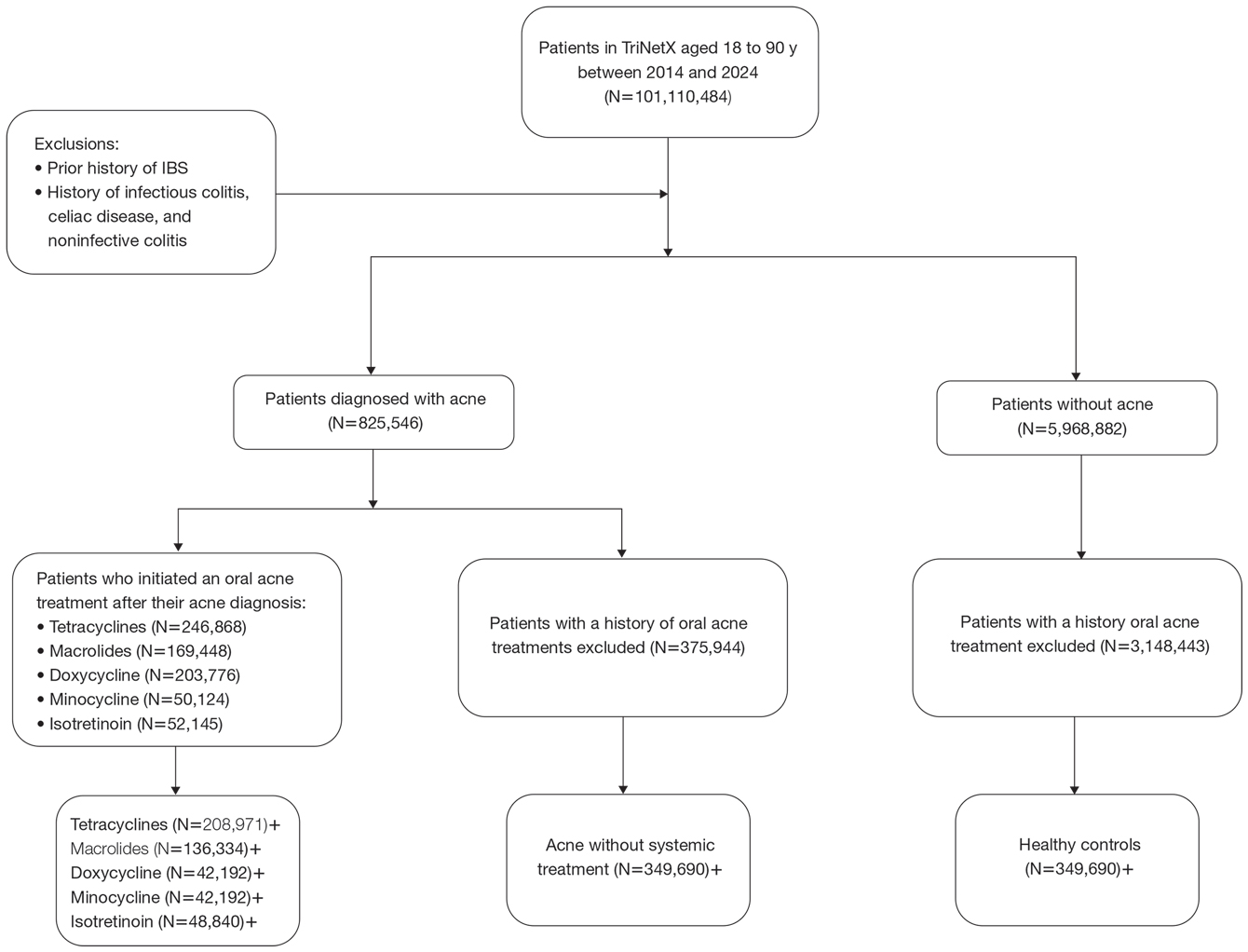

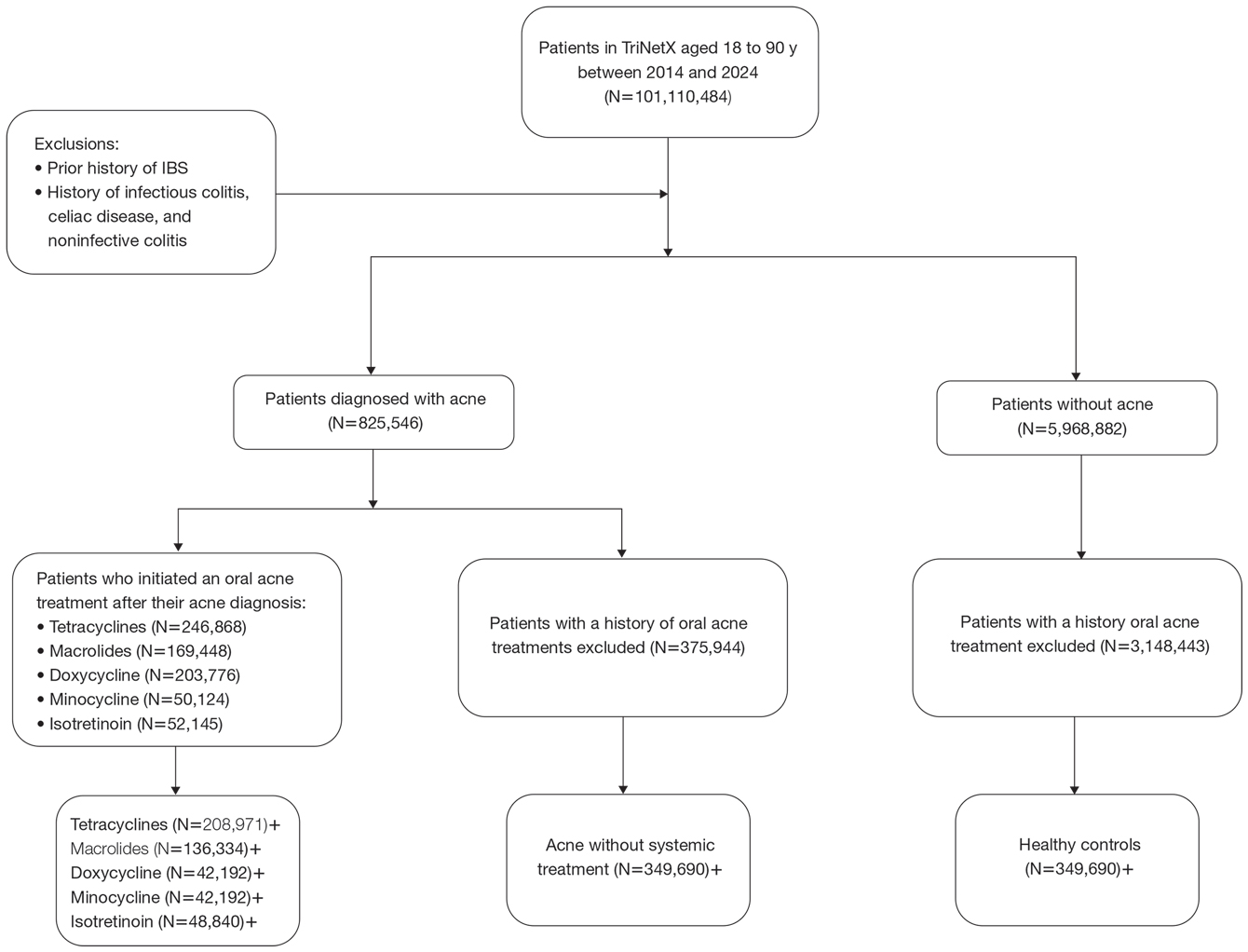

To examine potential associations between acne and IBS, 2 primary cohorts were established: patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications and healthy controls (ie, patients with no history of acne) who had no exposure to systemic acne treatments (Figure). Further, to assess the relationship between oral acne treatments (macrolides, tetracyclines, isotretinoin) and IBS, additional cohorts were created for each therapy and were compared to a cohort of patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications. To control for potential concomitant treatments, patients who had received any systemic treatment other than the specific therapy for their treatment cohort were excluded from our analysis.

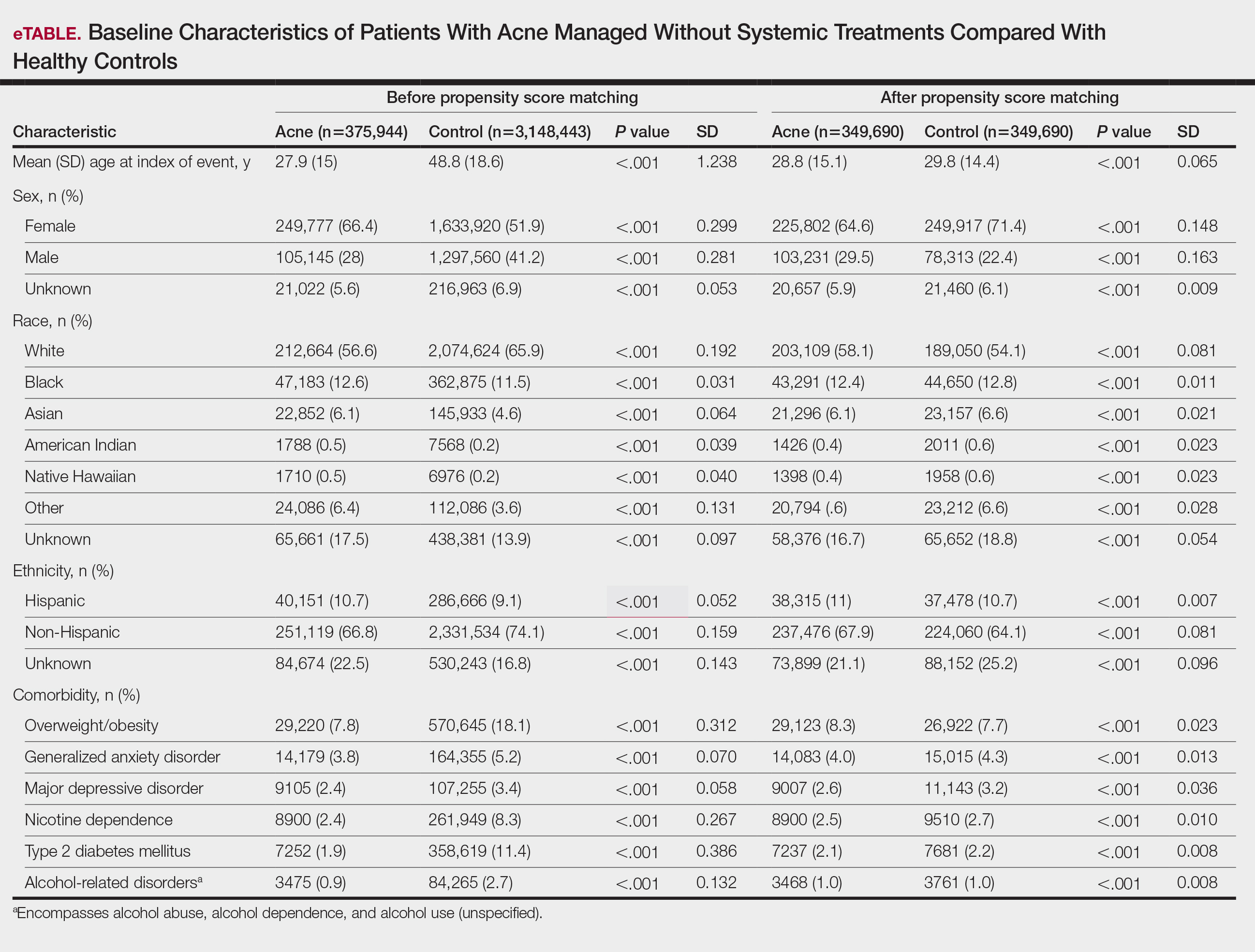

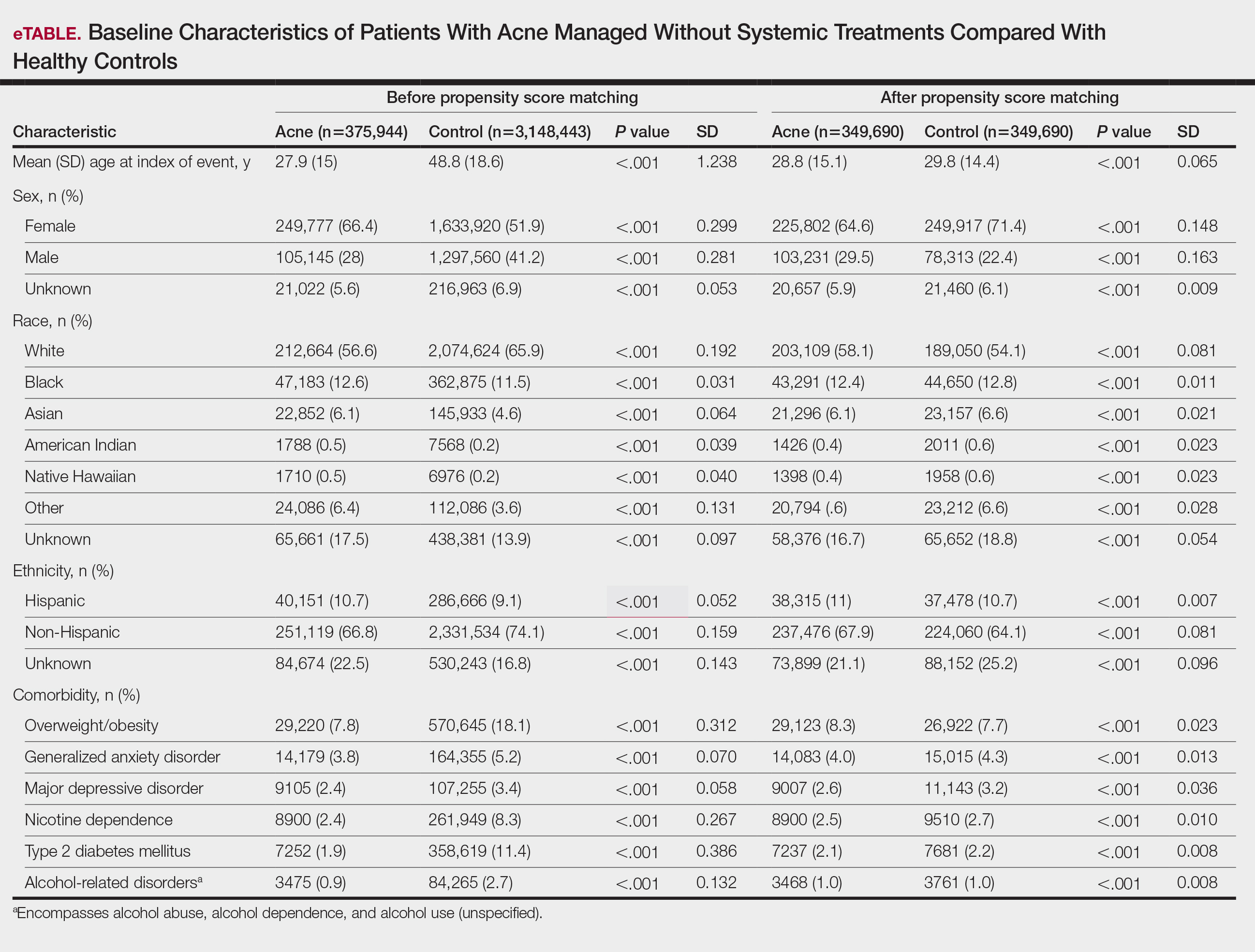

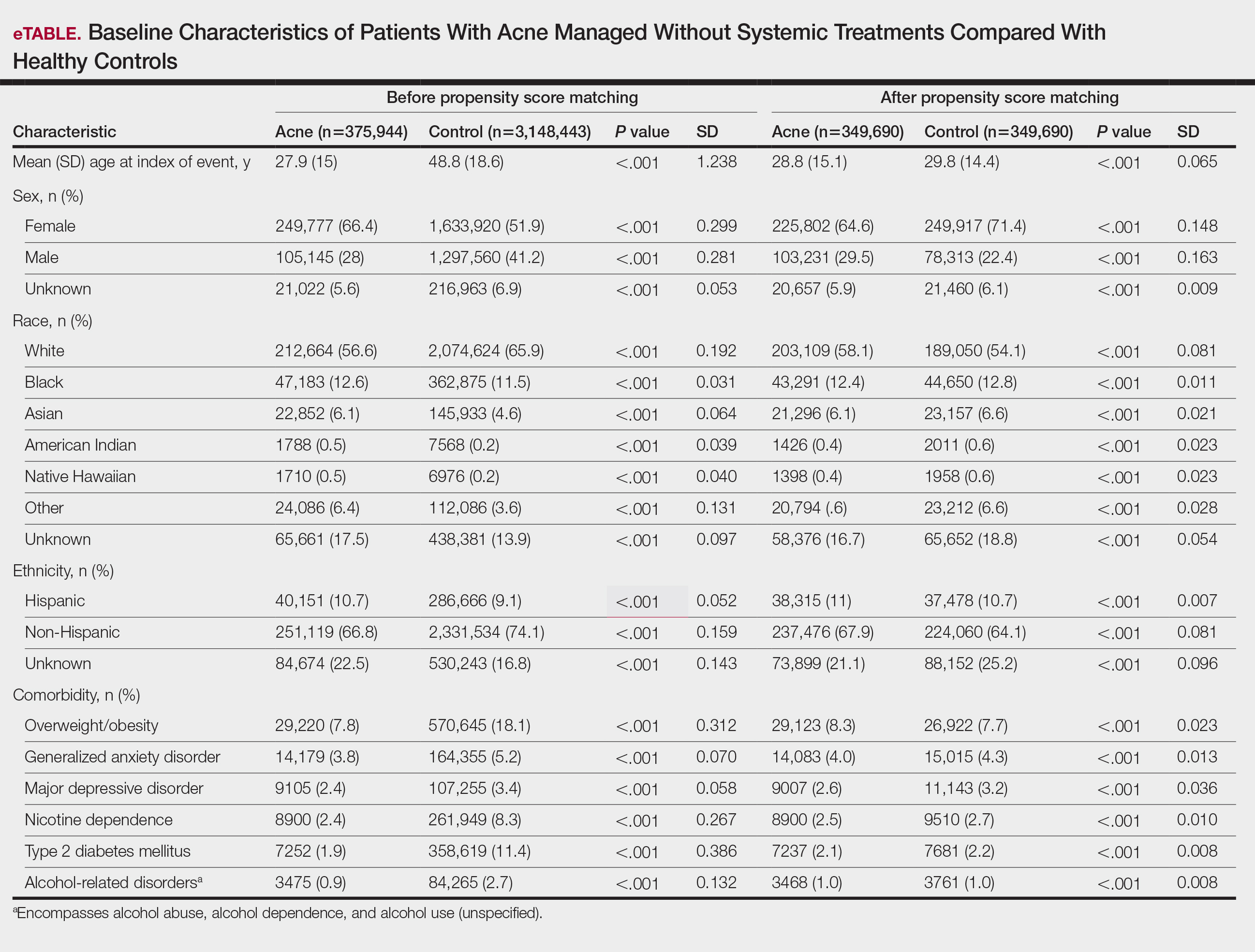

To account for potential confounders, all cohorts were 1:1 propensity score matched by demographics, tobacco and alcohol use, type 2 diabetes, obesity, anxiety, and depression (eTable). Each cohort was followed for 2 years after their index of event: the date of acne diagnosis for the acne cohort, the date of systemic treatment initiation for the treatment cohorts, and the date of the general adult encounter without abnormal findings for the control cohort. The primary outcome was the incidence of IBS, assessed by odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs.

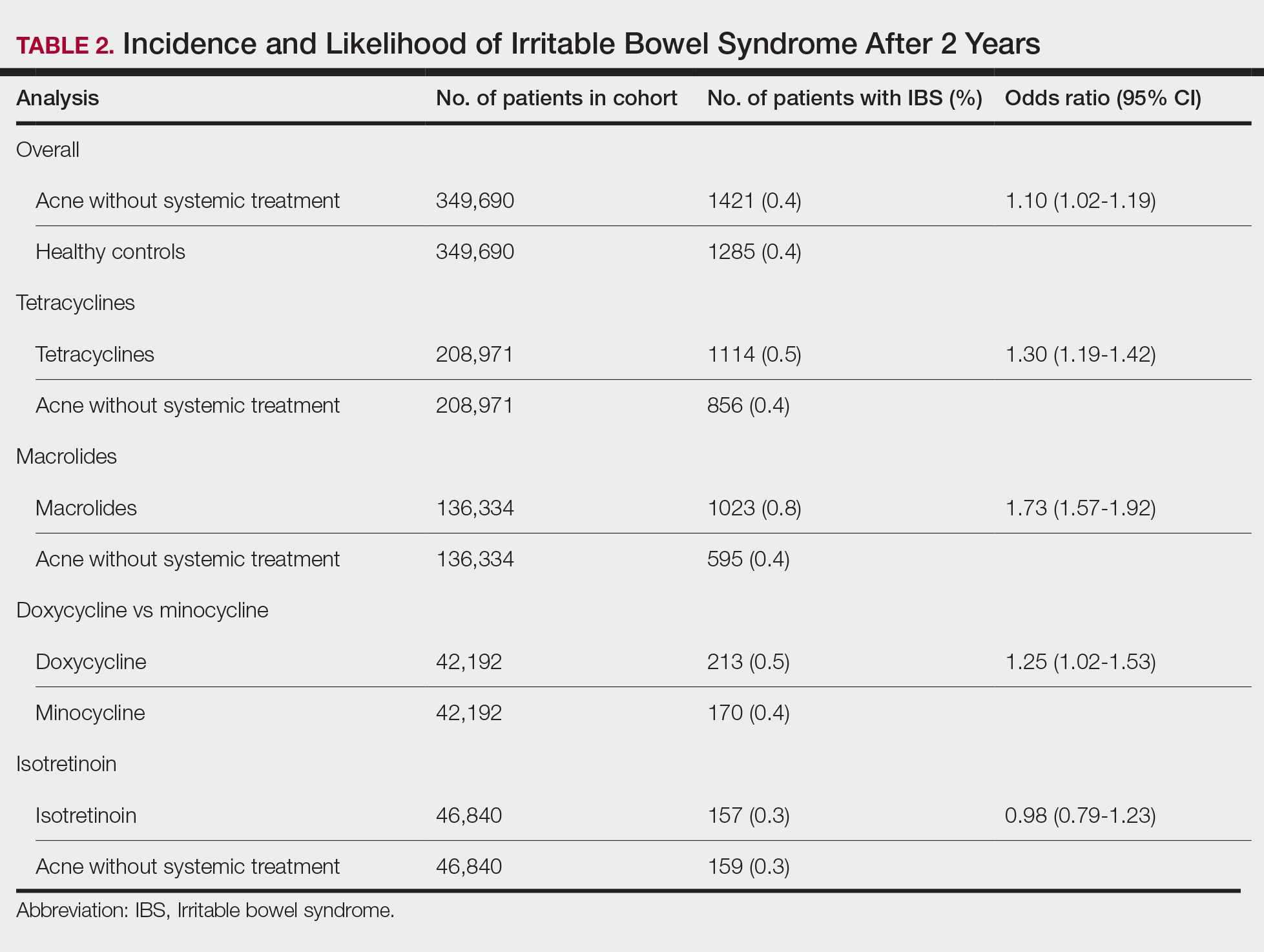

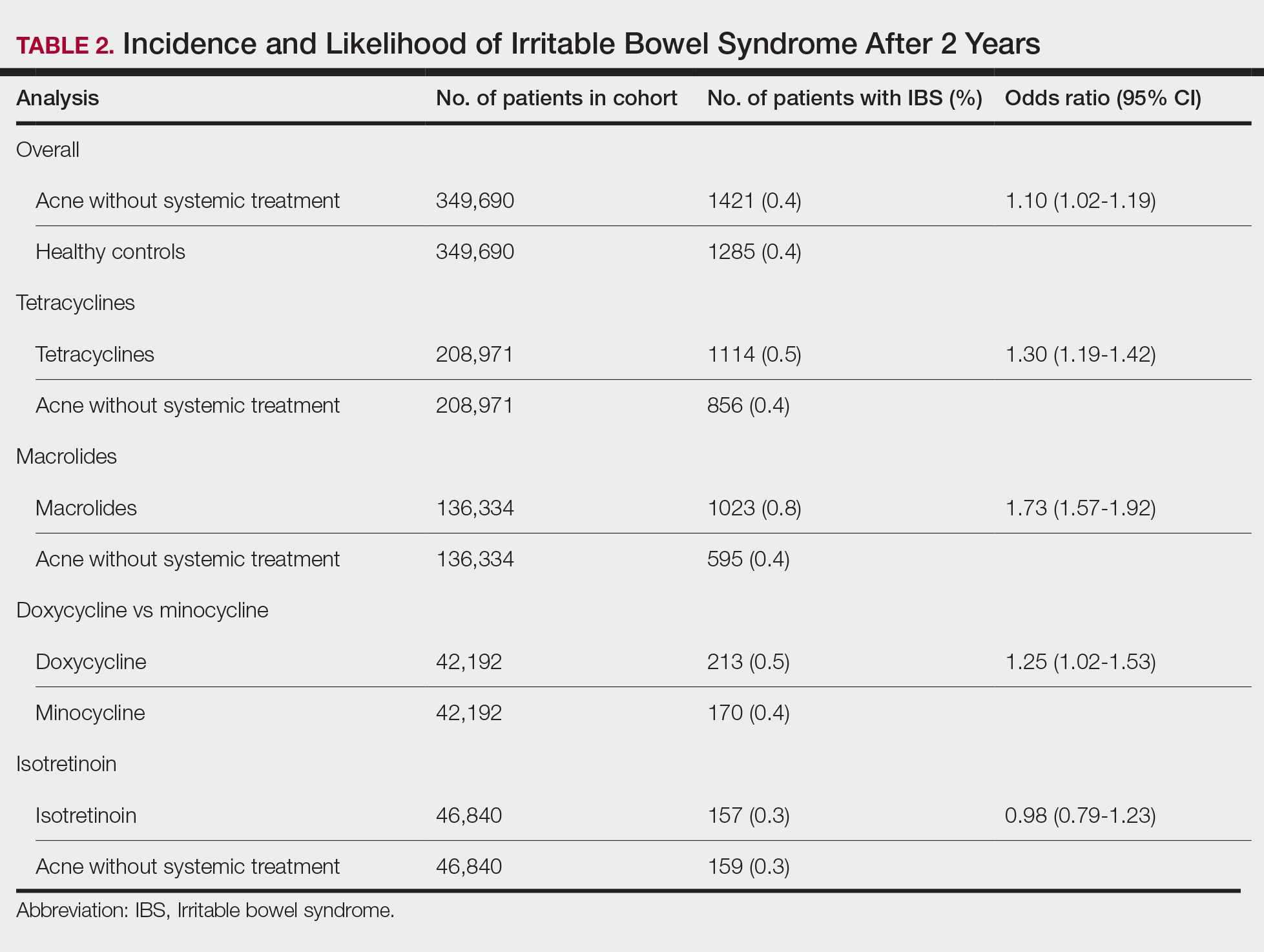

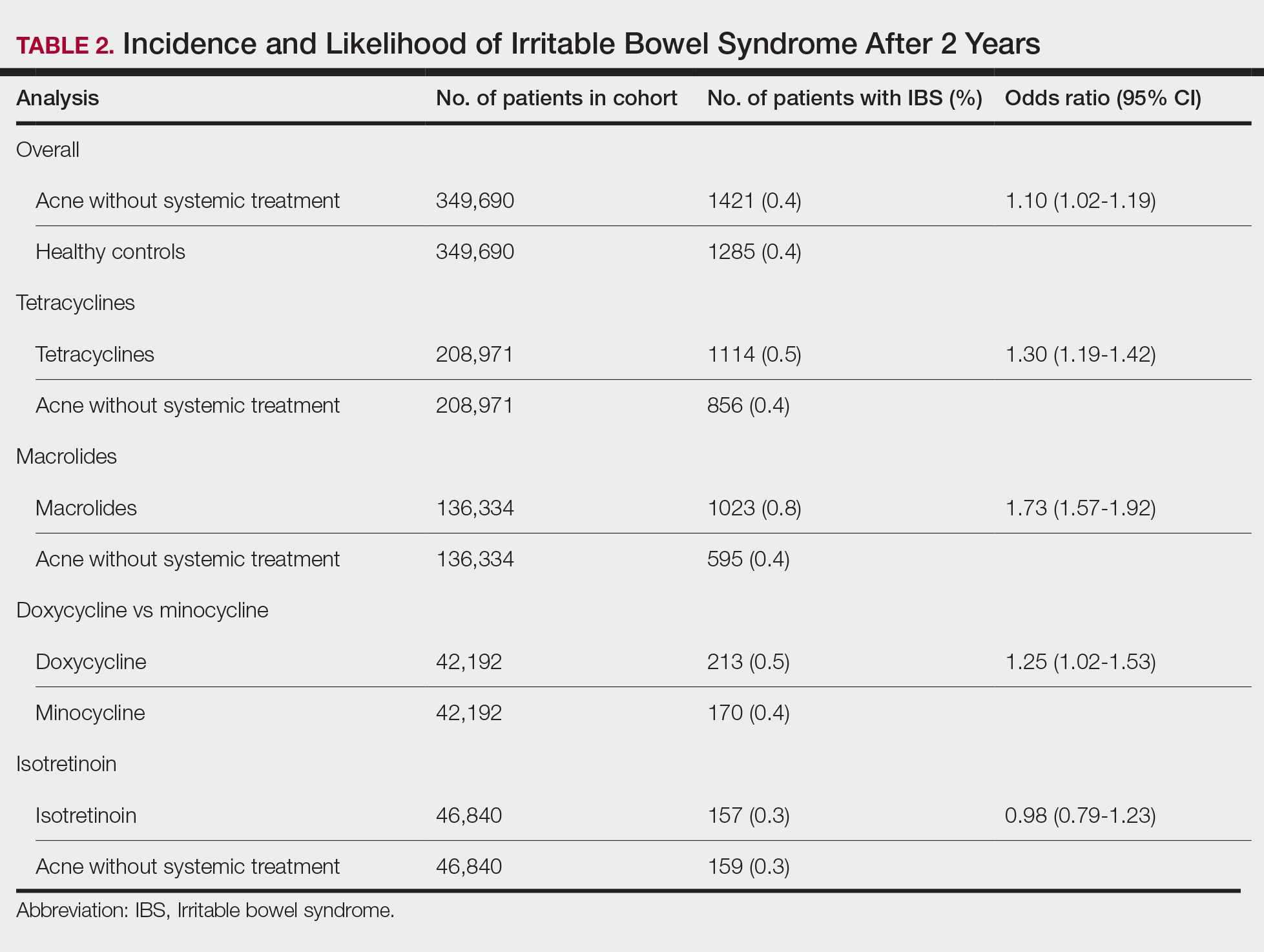

We identified 375,944 patients with acne managed without systemic treatment and 3,148,443 healthy controls who met study criteria. After the 1:1 propensity score match, each cohort included 49,690 patients (eTable). In the 2-year period after acne diagnosis, patients were more likely to develop IBS compared with controls (1421 vs 1285 [OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19])(Table 2). Patients with acne who were treated with tetracyclines (n=208,971) were 30% more likely to develop IBS than those managed without systemic medications (1114 vs 856 [OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.19-1.42]). Within the tetracycline cohort, doxycycline-treated patients were 25% more likely to develop IBS compared with those treated with minocycline (213 vs 170 [OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02-1.53]). Similarly, the use of macrolides (n=136,334) for acne treatment was significantly associated with an increased risk for IBS (1023 vs 595 [OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.57-1.92; P<.0001]) compared with controls. No statistically significant association was observed between isotretinoin and the incidence of IBS (Table 2).

In this large-scale cohort study, acne was associated with an increased likelihood of developing IBS within 2 years of an acne diagnosis compared with healthy controls. While a prior study also identified this association, it had a broader follow-up window ranging from 8 to 10 years.2 In contrast, our analysis specifically quantified the risk within the first 2 years of diagnosis. This distinction suggested potential for earlier IBS onset in patients with acne than has previously been recognized and may serve as an early clinical indicator for IBS risk in this population.

Our findings further suggested an association between oral tetracyclines and macrolides and an increased risk for IBS. This aligns with existing literature suggesting that oral antibiotic use can disrupt the gut microbiota and lead to potential gastrointestinal complications7 and reinforces the importance of careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice.

Although isotretinoin initially was surrounded by substantial controversy regarding its potential impact on gut health—particularly in inflammatory bowel disease8—our results do not support an increased risk for IBS among patients with acne who use isotretinoin. These findings challenge previous concerns and align with research suggesting that isotretinoin could be a safer alternative to antibiotic use for eligible patients who have a history of gastrointestinal disorders.6

This study highlights an important but underrecognized link between acne and IBS risk, emphasizing the need for early monitoring of gastrointestinal symptoms and careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice. Gastroenterology consultation may be advisable for patients with acne who have persistent gastrointestinal symptoms to facilitate a more integrated, patient-centered approach to care.

Limitations of this study include potential misclassification of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, selection bias, and residual confounding from unmeasured factors such as diet, lifestyle, disease severity, and treatment adherence due to the reliance on electronic health record data.

Our findings build upon prior evidence linking acne and IBS and offer important insights into the timing of this association following acne diagnosis. Future research should explore biological mechanisms underlying the gut-skin axis and evaluate targeted interventions to mitigate IBS risk in patients with acne.

Menees S, Chey W. The gut microbiome and irritable bowel syndrome. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1029. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14592.1

Yu-Wen C, Chun-Ying W, Yi-Ju C. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with acne vulgaris: a population-based retrospective study. JAAD Int. 2025;18:62-68. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2024.08.022

Deng Y, Wang H, Zhou J, et al. Patients with acne vulgaris have a distinct gut microbiota in comparison with healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:783-790. doi:10.2340/00015555-2968

Demirbas¸ A, Elmas ÖF. The relationship between acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:316-320. doi:10.1111/jocd.13481

Daye M, Cihan FG, Is¸ık B, et al. Evaluation of bowel habits in patients with acne vulgaris. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14903. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14903

Kridin K, Ludwig RJ. Isotretinoin and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: a large-scale global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:824-830. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.12.015

Villarreal AA, Aberger FJ, Benrud R, et al. Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the development of irritable bowel syndrome. WMJ. 2012;111:17-20.

Yu C-L, Chou P-Y, Liang C-S, et al. Isotretinoin exposure and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:721-730. doi:10.1007/s40257-023-00765-9

To the Editor:

Acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are both associated with microbial dysbiosis and chronic inflammation.1-3 While the prevalence of IBS among patients with acne has been examined previously,4,5 there has been limited focus on the risk for new-onset IBS following acne diagnosis. Current evidence suggests isotretinoin may be associated with a lower risk for IBS compared to oral antibiotics6; however, evidence supporting this association is limited outside these cohorts, highlighting the need for further investigation. In this large-scale study, we sought to investigate the incidence of new-onset IBS among patients with acne compared with healthy controls as well as to evaluate whether oral acne treatments (ie, oral antibiotics or isotretinoin) are associated with new-onset IBS in this population.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from the US Collaborative Network in TriNetX from October 2014 to October 2024. Patients were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, Current Procedural Terminology codes, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System codes, and RxNorm codes (Table 1). These codes were selected based on prior literature review, clinical relevance, and their ability to capture diagnoses of acne and IBS as well as relevant exclusion criteria. Patients were considered eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 90 years. Individuals with a history of IBS, inflammatory bowel disease, infectious gastroenteritis, or celiac disease were excluded from our analysis.

To examine potential associations between acne and IBS, 2 primary cohorts were established: patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications and healthy controls (ie, patients with no history of acne) who had no exposure to systemic acne treatments (Figure). Further, to assess the relationship between oral acne treatments (macrolides, tetracyclines, isotretinoin) and IBS, additional cohorts were created for each therapy and were compared to a cohort of patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications. To control for potential concomitant treatments, patients who had received any systemic treatment other than the specific therapy for their treatment cohort were excluded from our analysis.

To account for potential confounders, all cohorts were 1:1 propensity score matched by demographics, tobacco and alcohol use, type 2 diabetes, obesity, anxiety, and depression (eTable). Each cohort was followed for 2 years after their index of event: the date of acne diagnosis for the acne cohort, the date of systemic treatment initiation for the treatment cohorts, and the date of the general adult encounter without abnormal findings for the control cohort. The primary outcome was the incidence of IBS, assessed by odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs.

We identified 375,944 patients with acne managed without systemic treatment and 3,148,443 healthy controls who met study criteria. After the 1:1 propensity score match, each cohort included 49,690 patients (eTable). In the 2-year period after acne diagnosis, patients were more likely to develop IBS compared with controls (1421 vs 1285 [OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19])(Table 2). Patients with acne who were treated with tetracyclines (n=208,971) were 30% more likely to develop IBS than those managed without systemic medications (1114 vs 856 [OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.19-1.42]). Within the tetracycline cohort, doxycycline-treated patients were 25% more likely to develop IBS compared with those treated with minocycline (213 vs 170 [OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02-1.53]). Similarly, the use of macrolides (n=136,334) for acne treatment was significantly associated with an increased risk for IBS (1023 vs 595 [OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.57-1.92; P<.0001]) compared with controls. No statistically significant association was observed between isotretinoin and the incidence of IBS (Table 2).

In this large-scale cohort study, acne was associated with an increased likelihood of developing IBS within 2 years of an acne diagnosis compared with healthy controls. While a prior study also identified this association, it had a broader follow-up window ranging from 8 to 10 years.2 In contrast, our analysis specifically quantified the risk within the first 2 years of diagnosis. This distinction suggested potential for earlier IBS onset in patients with acne than has previously been recognized and may serve as an early clinical indicator for IBS risk in this population.

Our findings further suggested an association between oral tetracyclines and macrolides and an increased risk for IBS. This aligns with existing literature suggesting that oral antibiotic use can disrupt the gut microbiota and lead to potential gastrointestinal complications7 and reinforces the importance of careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice.

Although isotretinoin initially was surrounded by substantial controversy regarding its potential impact on gut health—particularly in inflammatory bowel disease8—our results do not support an increased risk for IBS among patients with acne who use isotretinoin. These findings challenge previous concerns and align with research suggesting that isotretinoin could be a safer alternative to antibiotic use for eligible patients who have a history of gastrointestinal disorders.6

This study highlights an important but underrecognized link between acne and IBS risk, emphasizing the need for early monitoring of gastrointestinal symptoms and careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice. Gastroenterology consultation may be advisable for patients with acne who have persistent gastrointestinal symptoms to facilitate a more integrated, patient-centered approach to care.

Limitations of this study include potential misclassification of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, selection bias, and residual confounding from unmeasured factors such as diet, lifestyle, disease severity, and treatment adherence due to the reliance on electronic health record data.

Our findings build upon prior evidence linking acne and IBS and offer important insights into the timing of this association following acne diagnosis. Future research should explore biological mechanisms underlying the gut-skin axis and evaluate targeted interventions to mitigate IBS risk in patients with acne.

To the Editor:

Acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are both associated with microbial dysbiosis and chronic inflammation.1-3 While the prevalence of IBS among patients with acne has been examined previously,4,5 there has been limited focus on the risk for new-onset IBS following acne diagnosis. Current evidence suggests isotretinoin may be associated with a lower risk for IBS compared to oral antibiotics6; however, evidence supporting this association is limited outside these cohorts, highlighting the need for further investigation. In this large-scale study, we sought to investigate the incidence of new-onset IBS among patients with acne compared with healthy controls as well as to evaluate whether oral acne treatments (ie, oral antibiotics or isotretinoin) are associated with new-onset IBS in this population.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted using data from the US Collaborative Network in TriNetX from October 2014 to October 2024. Patients were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, Current Procedural Terminology codes, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System codes, and RxNorm codes (Table 1). These codes were selected based on prior literature review, clinical relevance, and their ability to capture diagnoses of acne and IBS as well as relevant exclusion criteria. Patients were considered eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 90 years. Individuals with a history of IBS, inflammatory bowel disease, infectious gastroenteritis, or celiac disease were excluded from our analysis.

To examine potential associations between acne and IBS, 2 primary cohorts were established: patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications and healthy controls (ie, patients with no history of acne) who had no exposure to systemic acne treatments (Figure). Further, to assess the relationship between oral acne treatments (macrolides, tetracyclines, isotretinoin) and IBS, additional cohorts were created for each therapy and were compared to a cohort of patients with acne who were managed without systemic medications. To control for potential concomitant treatments, patients who had received any systemic treatment other than the specific therapy for their treatment cohort were excluded from our analysis.

To account for potential confounders, all cohorts were 1:1 propensity score matched by demographics, tobacco and alcohol use, type 2 diabetes, obesity, anxiety, and depression (eTable). Each cohort was followed for 2 years after their index of event: the date of acne diagnosis for the acne cohort, the date of systemic treatment initiation for the treatment cohorts, and the date of the general adult encounter without abnormal findings for the control cohort. The primary outcome was the incidence of IBS, assessed by odds ratio (OR) and 95% CIs.

We identified 375,944 patients with acne managed without systemic treatment and 3,148,443 healthy controls who met study criteria. After the 1:1 propensity score match, each cohort included 49,690 patients (eTable). In the 2-year period after acne diagnosis, patients were more likely to develop IBS compared with controls (1421 vs 1285 [OR, 1.10; 95% CI, 1.02-1.19])(Table 2). Patients with acne who were treated with tetracyclines (n=208,971) were 30% more likely to develop IBS than those managed without systemic medications (1114 vs 856 [OR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.19-1.42]). Within the tetracycline cohort, doxycycline-treated patients were 25% more likely to develop IBS compared with those treated with minocycline (213 vs 170 [OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.02-1.53]). Similarly, the use of macrolides (n=136,334) for acne treatment was significantly associated with an increased risk for IBS (1023 vs 595 [OR, 1.73; 95% CI, 1.57-1.92; P<.0001]) compared with controls. No statistically significant association was observed between isotretinoin and the incidence of IBS (Table 2).

In this large-scale cohort study, acne was associated with an increased likelihood of developing IBS within 2 years of an acne diagnosis compared with healthy controls. While a prior study also identified this association, it had a broader follow-up window ranging from 8 to 10 years.2 In contrast, our analysis specifically quantified the risk within the first 2 years of diagnosis. This distinction suggested potential for earlier IBS onset in patients with acne than has previously been recognized and may serve as an early clinical indicator for IBS risk in this population.

Our findings further suggested an association between oral tetracyclines and macrolides and an increased risk for IBS. This aligns with existing literature suggesting that oral antibiotic use can disrupt the gut microbiota and lead to potential gastrointestinal complications7 and reinforces the importance of careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice.

Although isotretinoin initially was surrounded by substantial controversy regarding its potential impact on gut health—particularly in inflammatory bowel disease8—our results do not support an increased risk for IBS among patients with acne who use isotretinoin. These findings challenge previous concerns and align with research suggesting that isotretinoin could be a safer alternative to antibiotic use for eligible patients who have a history of gastrointestinal disorders.6

This study highlights an important but underrecognized link between acne and IBS risk, emphasizing the need for early monitoring of gastrointestinal symptoms and careful antibiotic stewardship in dermatologic practice. Gastroenterology consultation may be advisable for patients with acne who have persistent gastrointestinal symptoms to facilitate a more integrated, patient-centered approach to care.

Limitations of this study include potential misclassification of International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification codes, selection bias, and residual confounding from unmeasured factors such as diet, lifestyle, disease severity, and treatment adherence due to the reliance on electronic health record data.

Our findings build upon prior evidence linking acne and IBS and offer important insights into the timing of this association following acne diagnosis. Future research should explore biological mechanisms underlying the gut-skin axis and evaluate targeted interventions to mitigate IBS risk in patients with acne.

Menees S, Chey W. The gut microbiome and irritable bowel syndrome. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1029. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14592.1

Yu-Wen C, Chun-Ying W, Yi-Ju C. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with acne vulgaris: a population-based retrospective study. JAAD Int. 2025;18:62-68. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2024.08.022

Deng Y, Wang H, Zhou J, et al. Patients with acne vulgaris have a distinct gut microbiota in comparison with healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:783-790. doi:10.2340/00015555-2968

Demirbas¸ A, Elmas ÖF. The relationship between acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:316-320. doi:10.1111/jocd.13481

Daye M, Cihan FG, Is¸ık B, et al. Evaluation of bowel habits in patients with acne vulgaris. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14903. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14903

Kridin K, Ludwig RJ. Isotretinoin and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: a large-scale global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:824-830. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.12.015

Villarreal AA, Aberger FJ, Benrud R, et al. Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the development of irritable bowel syndrome. WMJ. 2012;111:17-20.

Yu C-L, Chou P-Y, Liang C-S, et al. Isotretinoin exposure and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:721-730. doi:10.1007/s40257-023-00765-9

Menees S, Chey W. The gut microbiome and irritable bowel syndrome. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1029. doi:10.12688/f1000research.14592.1

Yu-Wen C, Chun-Ying W, Yi-Ju C. Gastrointestinal comorbidities in patients with acne vulgaris: a population-based retrospective study. JAAD Int. 2025;18:62-68. doi:10.1016/j.jdin.2024.08.022

Deng Y, Wang H, Zhou J, et al. Patients with acne vulgaris have a distinct gut microbiota in comparison with healthy controls. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:783-790. doi:10.2340/00015555-2968

Demirbas¸ A, Elmas ÖF. The relationship between acne vulgaris and irritable bowel syndrome: a preliminary study. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:316-320. doi:10.1111/jocd.13481

Daye M, Cihan FG, Is¸ık B, et al. Evaluation of bowel habits in patients with acne vulgaris. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e14903. doi:10.1111/ijcp.14903

Kridin K, Ludwig RJ. Isotretinoin and the risk of inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome: a large-scale global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:824-830. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2022.12.015

Villarreal AA, Aberger FJ, Benrud R, et al. Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics and the development of irritable bowel syndrome. WMJ. 2012;111:17-20.

Yu C-L, Chou P-Y, Liang C-S, et al. Isotretinoin exposure and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24:721-730. doi:10.1007/s40257-023-00765-9

Spironolactone for Acne: Practical Strategies for Optimal Clinical Outcomes

Spironolactone for Acne: Practical Strategies for Optimal Clinical Outcomes

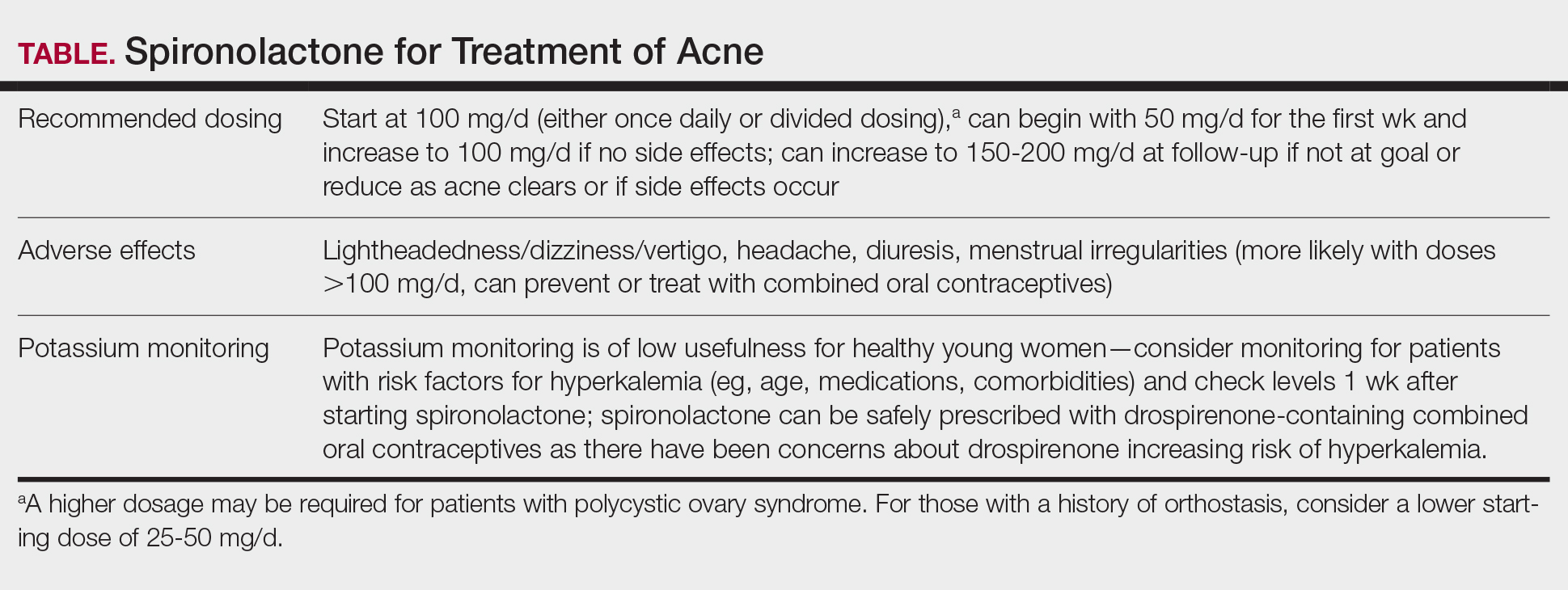

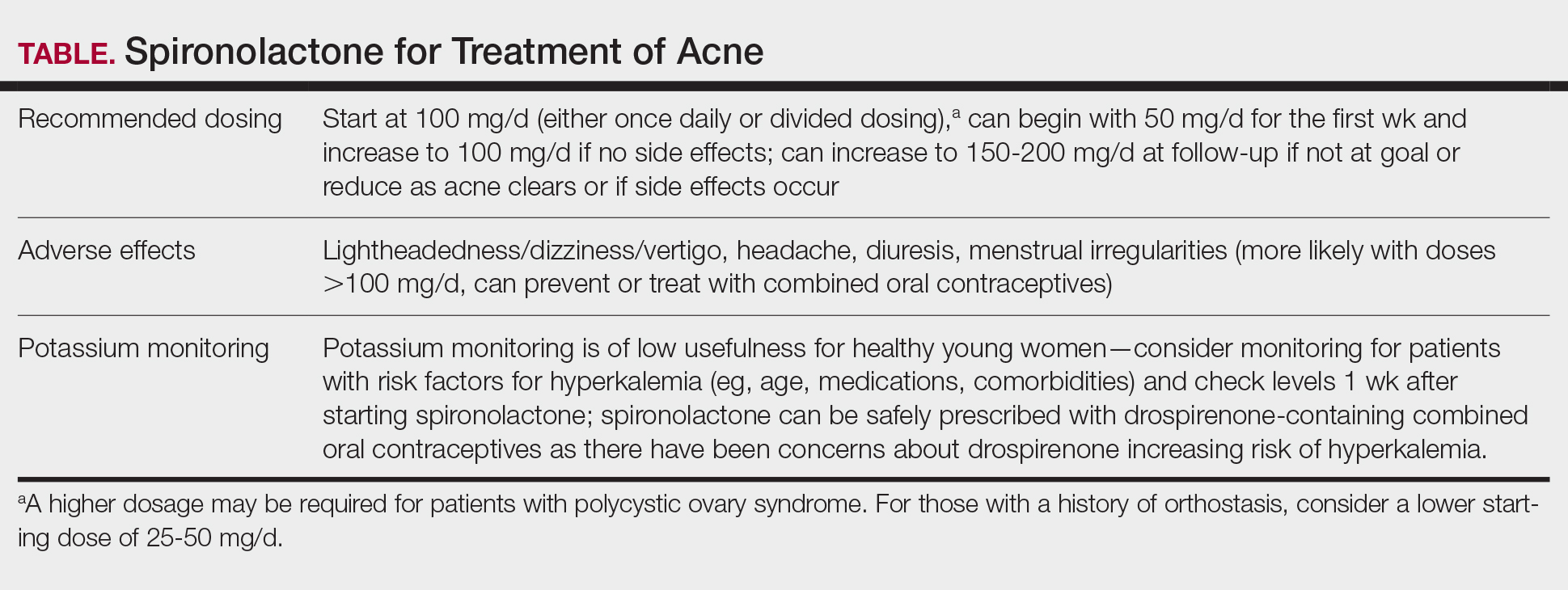

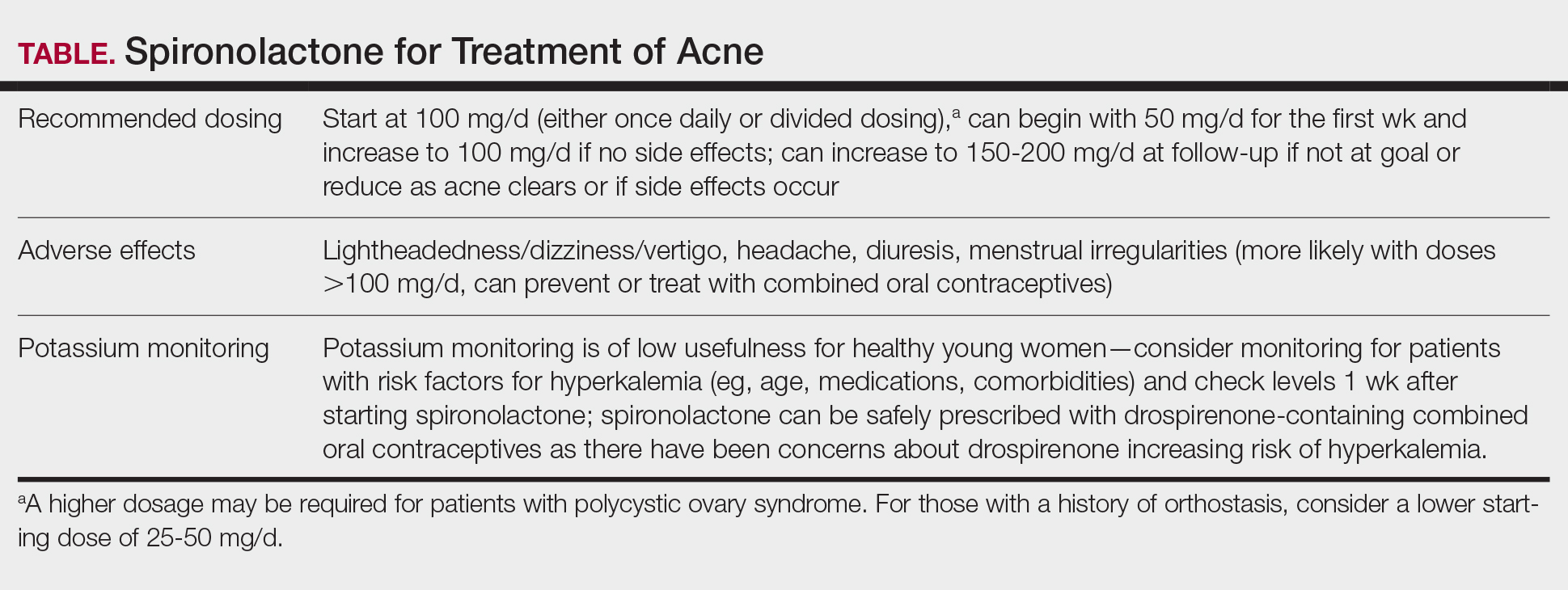

Spironolactone is increasingly used off label for acne treatment and is now being prescribed for women with acne at a frequency similar to oral antibiotics.1,2 In this article, we provide an overview of spironolactone use for acne treatment and discuss recent clinical trials and practical strategies for patient selection, dosing, adverse effect management, and monitoring (Table).

History and Mechanism of Action

Because sebaceous gland activity is an important component of acne pathogenesis and is regulated by androgens,3 there has long been interest in identifying treatment strategies that can target the role of hormones in activating the sebaceous gland. In the 1980s, it became apparent that spironolactone, originally developed as a potassium-sparing diuretic, also might possess antiandrogenic properties that could be useful in the treatment of acne.4 Spironolactone has been found to decrease testosterone production, inhibit testosterone and dihydrotestosterone binding to androgen receptors,5-8 and block 5α-reductase receptors of the sebaceous glands of skin.9

In 1984, Goodfellow et al10 conducted a trial in which 36 male and female patients with severe acne were randomized to placebo or spironolactone doses ranging from 50 to 200 mg/d. They found that spironolactone resulted in dose-dependent reductions of sebum production as well as improvement in patient- and clinician-reported assessments of acne. In 1986, another placebo-controlled crossover trial by Muhlemann et al11 provided further support for the effectiveness of spironolactone for acne. This trial randomized 21 women to placebo or spironolactone 200 mg/d and found that spironolactone was associated with statistically significant (P<.001) improvements in acne lesion counts.

Recent Observational Studies and Trials

Following these early trials, several large case series have been published describing the successful use of spironolactone for acne, including a 2020 retrospective case series from the Mayo Clinic describing 395 patients.12 The investigators found that almost 66% of patients had a complete response and almost 85% had a complete response or a partial response greater than 50%. They also found that the median time to initial response and maximal response were 3 and 5 months, respectively, and that efficacy was observed across acne subtypes, including for nodulocystic acne.12 In addition, a 2021 case series describing 403 patients treated with spironolactone found that approximately 80% had reduction or complete clearance of acne, with improvements observed for both facial and truncal acne. In this cohort, doses of 100 to 150 mg/d typically were the most successful.13 A case series of 80 adolescent females also highlighted the efficacy of spironolactone in younger populations.14

Adding to these observational data, the multicenter, phase 3, double-blind Spironolactone for Adult Female Acne (SAFA) trial included 410 women (mean age, 29.2 years) who were randomized to receive either placebo or intervention (spironolactone 50 mg/d until week 6 and 100 mg/d until week 24).15 At 24 weeks, greater improvement in quality of life and participant self-assessed improvement were observed in the spironolactone group. In addition, at 12 weeks, rates of success were higher in the spironolactone group using the Investigator Global Assessment score (adjusted odds ratio 5.18 [95% CI, 2.18- 12.28]). Those randomized to receive spironolactone also had lower rates of oral antibiotic use at 52 weeks than the placebo group did (5.8% vs 13.5%, respectively).

In the SAFA trial, spironolactone was well tolerated; the most common adverse effects relative to placebo were lightheadedness (19% for spironolactone vs 12% for placebo) and headache (20% for spironolactone vs 12% for placebo). Notably, more than 95% of patients were able to increase from 50 mg/d to 100 mg/d at week 6, with greater than 90% tolerating 100 mg/d. As observational data suggest that spironolactone takes 3 to 5 months to reach peak efficacy, these findings provide further support that starting at a dose of at least 100 mg/d is likely optimal for most patients.16

A Potential Alternative to Oral Antibiotics

Oral antibiotics such as tetracyclines have long played a central role in the treatment of acne and remain a first-line treatment option.17 In addition, many of these antibiotic courses exceed 6 months in duration.1 In fact, dermatologists prescribe more antibiotics per capita than any other specialty1,18-20; however, this can be associated with the development of antibiotic resistance,21,22 as well as other antibiotic-associated complications, including inflammatory bowel disease,23 pharyngitis,24 Clostridium difficile infections, and cancer.25-29

In addition to these concerns, many patients may prefer nonantibiotic alternatives to oral antibiotics, with more than 75% preferring a nonantibiotic option if available. For female patients with acne, antiandrogens such as spironolactone have been suggested as a potential alternative.30 A 10-year retrospective study of female patients with acne found that those who had ever received hormonal therapy (ie, spironolactone or a combined oral contraceptive) received fewer cumulative days of oral antibiotics than those who did not (226 days vs 302 days, respectively).31 In addition, while oral antibiotics were the most common initial therapy prescribed for patients, as they progressed through their treatment course, more patients ended up on hormonal therapy than oral antibiotics. This study suggests that hormonal therapy such as spironolactone could represent an alternative to the use of systemic antibiotics.31

Further supporting the role of spironolactone as an alternative to oral antibiotics, a 2018 analysis of claims data found that spironolactone may have similar effectiveness to oral antibiotics for the treatment of acne.32 After adjusting for age and topical retinoid and oral contraceptive use, this study found that there was no significant difference in the odds of being prescribed a different systemic treatment within 1 year (ie, treatment failure) among those starting spironolactone vs those starting oral tetracycline-class antibiotics as their initial therapy for acne.

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial (Female Acne Spironolactone vs doxyCycline Efficacy [FASCE]) also evaluated the comparative effectiveness of doxycycline 100 mg/d for 3 months followed by an oral placebo for 3 months vs spironolactone 150 mg/d for 6 months among 133 adult women with acne. This study found that spironolactone had statistically significantly greater rates of Investigator Global Assessment treatment success after 6 months (odds ratio 2.87 [95% CI, 1.38-5.99; P=.007]).33 Since spironolactone historically has been prescribed less often than oral antibiotics for women with acne, these findings support spironolactone as an underutilized treatment alternative. The ongoing Spironolactone versus Doxycycline for Acne: A Comparative Effectiveness, Noninferiority Evaluation trial—a 16-week, blinded trial comparing 100 mg/d doses of both drugs—should provide additional evidence regarding the relative role of spironolactone and oral antibiotics in the management of acne.34

Ultimately, the decision to use spironolactone or other treatments such as oral antibiotics should be based on shared decision making between clinician and patient. Spironolactone has a relatively slow onset of efficacy, and other options such as oral antibiotics might be preferred by those looking for more immediate results; however, as women with acne often have activity that persists into adulthood, spironolactone might be preferable as a long-term maintenance therapy to avoid complications of prolonged antibiotic use.35 Comorbidities also will influence the optimal choice of therapy (eg, spironolactone might be preferred in someone with inflammatory bowel disease, and oral antibiotics might be preferred in someone with orthostatic hypotension).

Patient Selection

Acne occurring along the lower face or jawline in adult women sometimes is referred to as hormonal acne, but this dogma is not particularly evidence based. An observational study of 374 patients found that almost 90% of adult women had acne involving multiple facial zones with a spectrum of facial acne severity similar to that in adolescents.36 Only a small subset of these patients (11.2%) had acne localized solely to the mandibular area. In addition, acne along the lower face is not predictive of hyperandrogenism (eg, polycystic ovary syndrome).37 Antiandrogen therapies such as spironolactone and clascoterone are effective in both men and women with acne10,38 and in adolescents and adults, suggesting that hormones play a fundamental role in all acne and that addressing this mechanism can be useful broadly. Therefore, hormonal therapies such as spironolactone should not be restricted to only adult women with acne along the lower face.