User login

Annular Erythematous Plaques on the Back

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Annulare

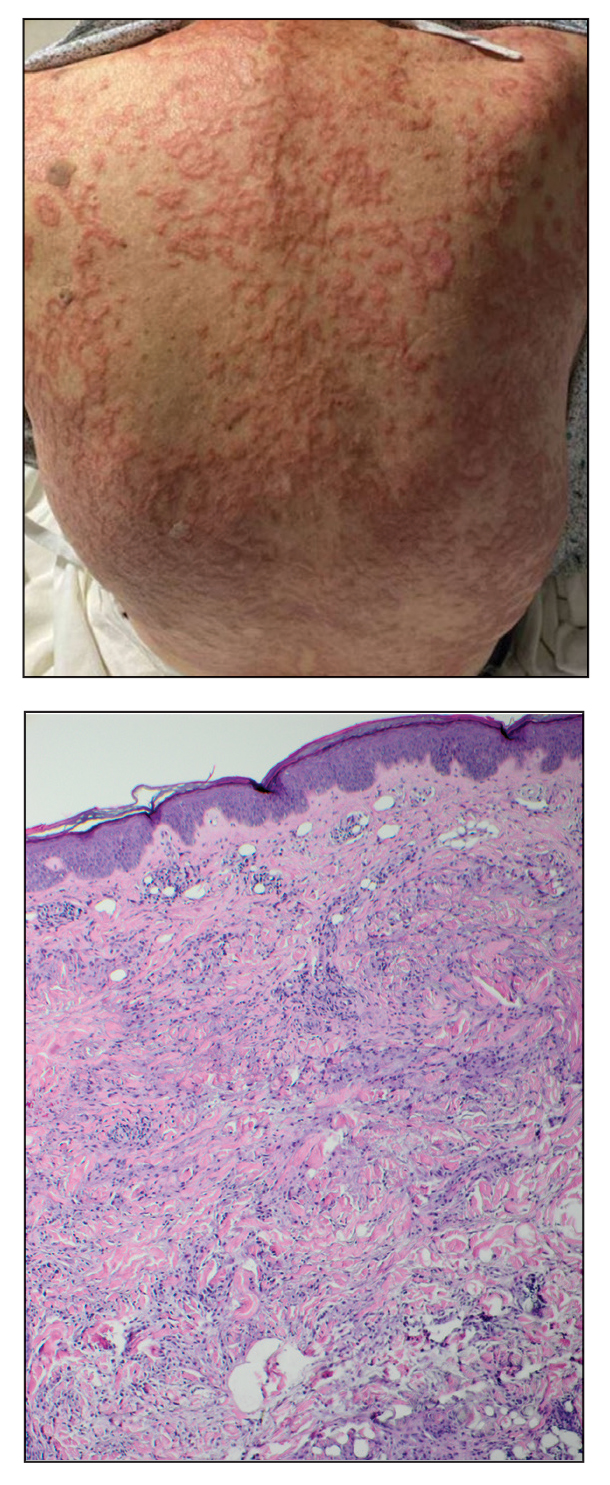

The biopsies revealed palisading granulomatous dermatitis consistent with granuloma annulare (GA). This diagnosis was supported by the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. Although the pathogenesis of GA is unclear, it is a benign, self-limiting condition. Primarily affected sites include the trunk and forearms. Generalized GA (or GA with ≥10 lesions) may warrant workup for malignancy, as it may represent a paraneoplastic process.1 Histopathology reveals granulomas comprising a dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate as well as central mucin and nuclear debris. There are a few histologic subtypes of GA, including palisading and interstitial, which refer to the distribution of the histiocytic infiltrate.2,3 This case—with palisading histiocytes lining the collection of necrobiosis and mucin (bottom quiz image)—features palisading GA. Notably, GA exhibits central rather than diffuse mucin.4

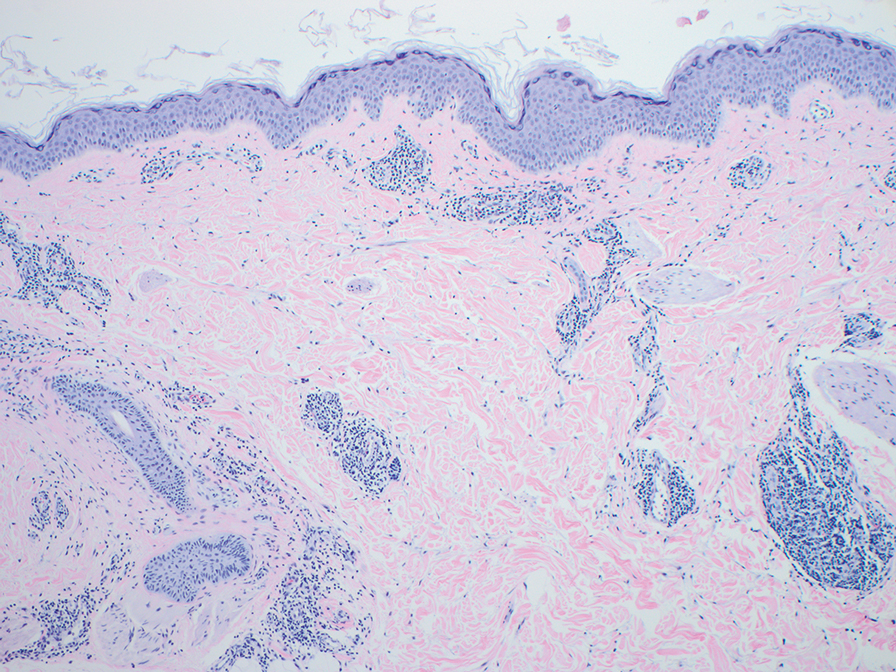

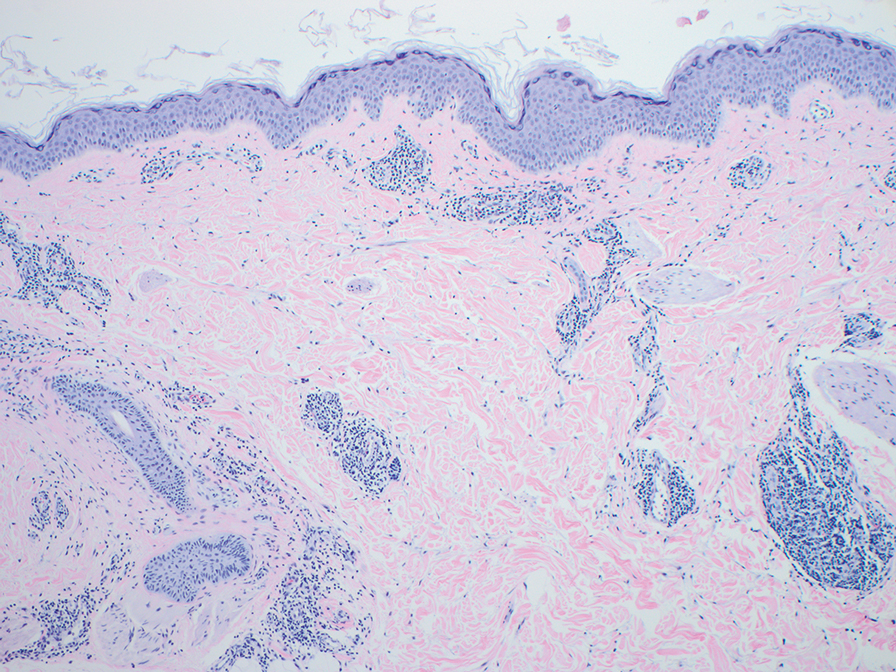

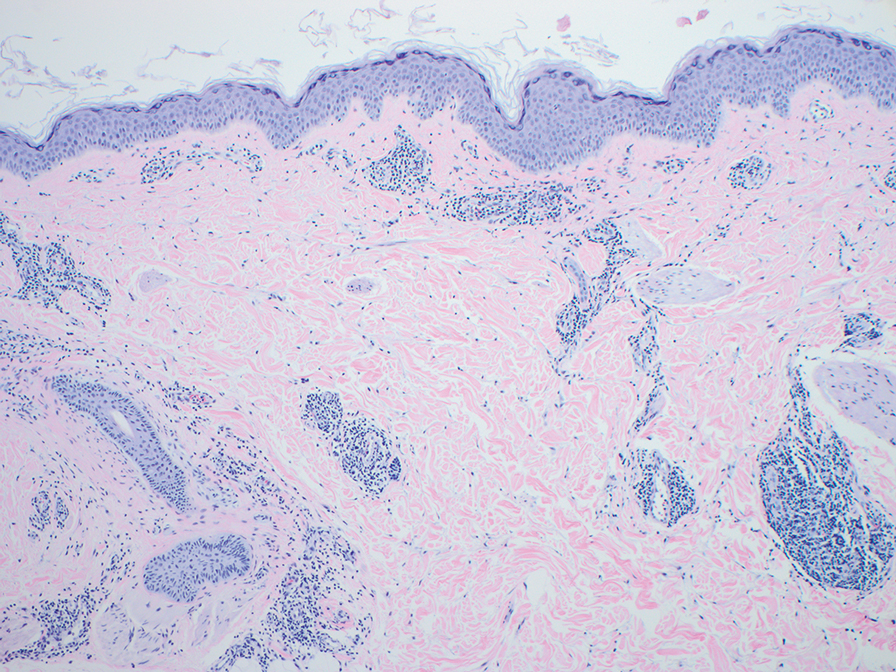

Erythema gyratum repens is a paraneoplastic arcuate erythema that manifests as erythematous figurate, gyrate, or annular plaques exhibiting a trailing scale. Clinically, erythema gyratum repens spreads rapidly—as quickly as 1 cm/d—and can be extensive (as in this case). Histopathology ruled out this diagnosis in our patient. Nonspecific findings of acanthosis, parakeratosis, and superficial spongiosis can be found in erythema gyratum repens. A superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate may be seen in figurate erythemas (Figure 1).5 Unlike GA, this infiltrate does not form granulomas, is more superficial, and does not contain mucin.

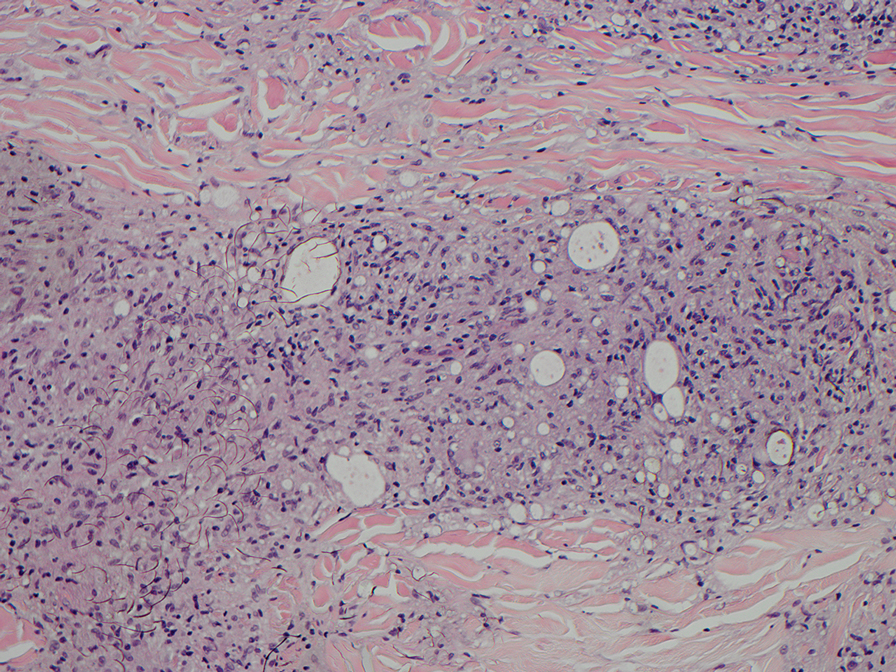

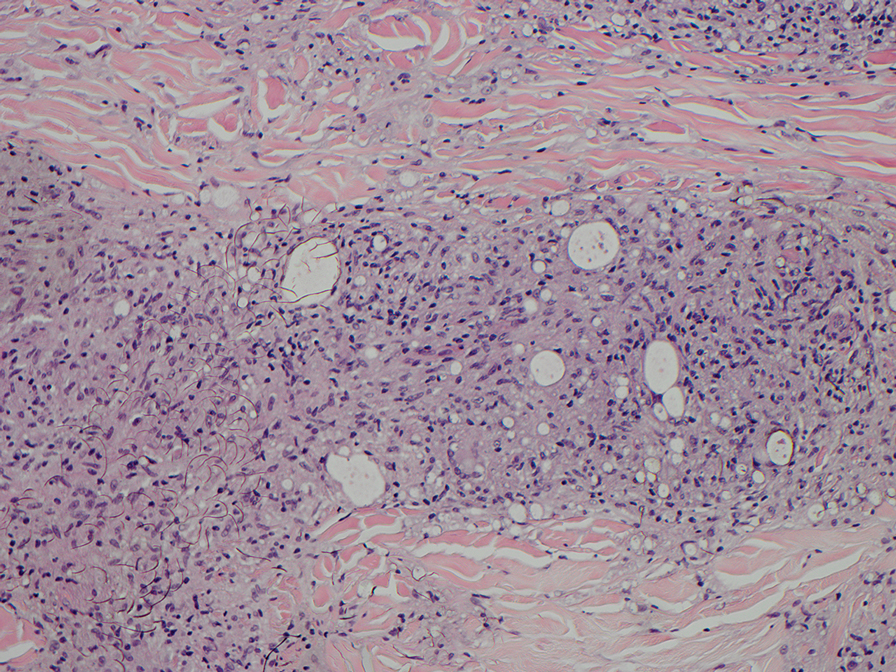

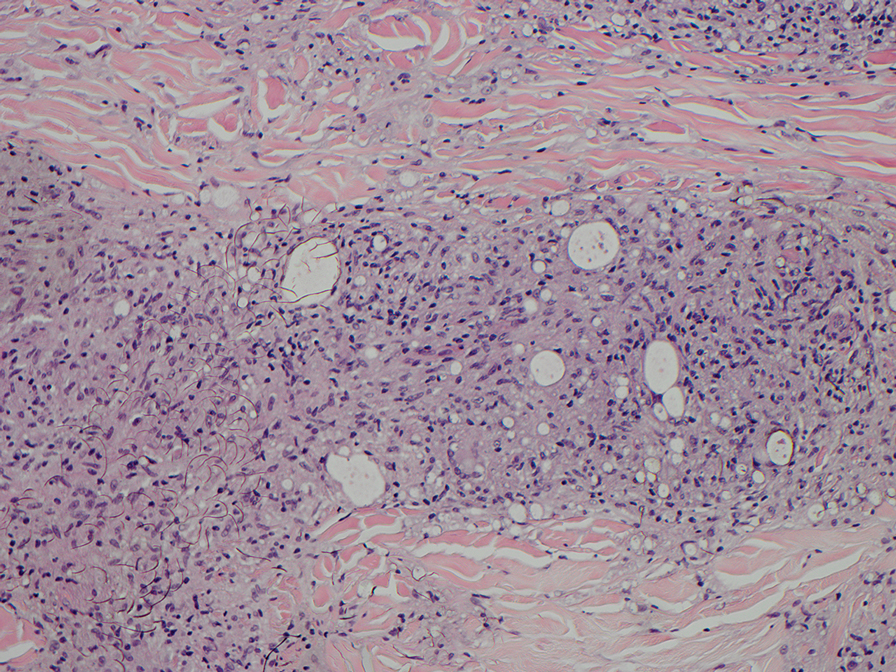

Histopathology also can help establish the diagnosis of leprosy and its specific subtype, as leprosy exists on a spectrum from tuberculoid to lepromatous, with a great deal of overlap in between.6 Lepromatous leprosy has many cutaneous clinical presentations but typically manifests as erythematous papules or nodules. It is multibacillary, and these mycobacteria form clumps known as globi that can be seen on Fite stain.7 In lepromatous leprosy, there is a characteristic dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2) above which a Grenz zone can be seen.4,8 There are no well-formed granulomas in lepromatous leprosy, unlike in tuberculoid leprosy, which is paucibacillary and creates a granulomatous response surrounding nerves and adnexal structures.6

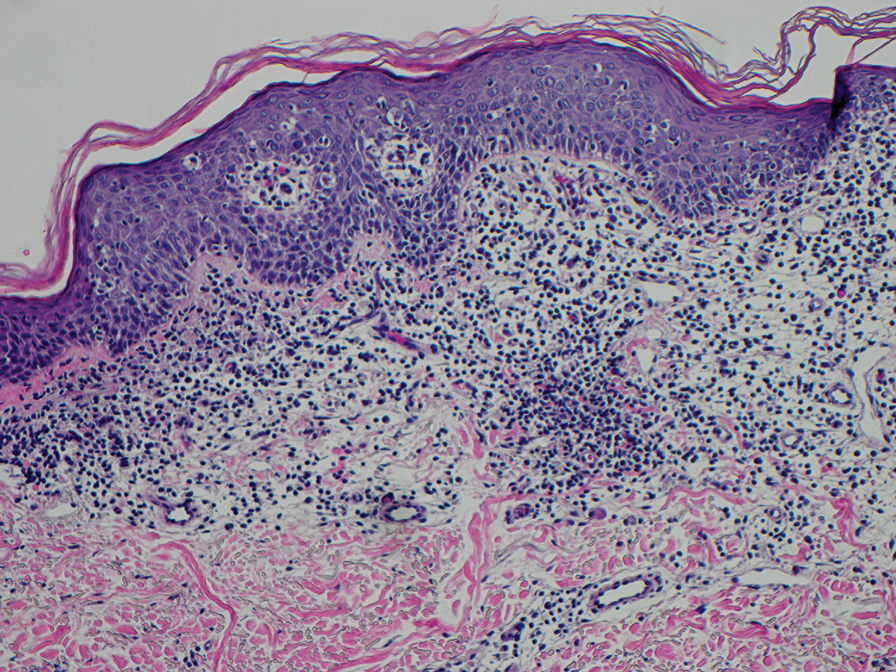

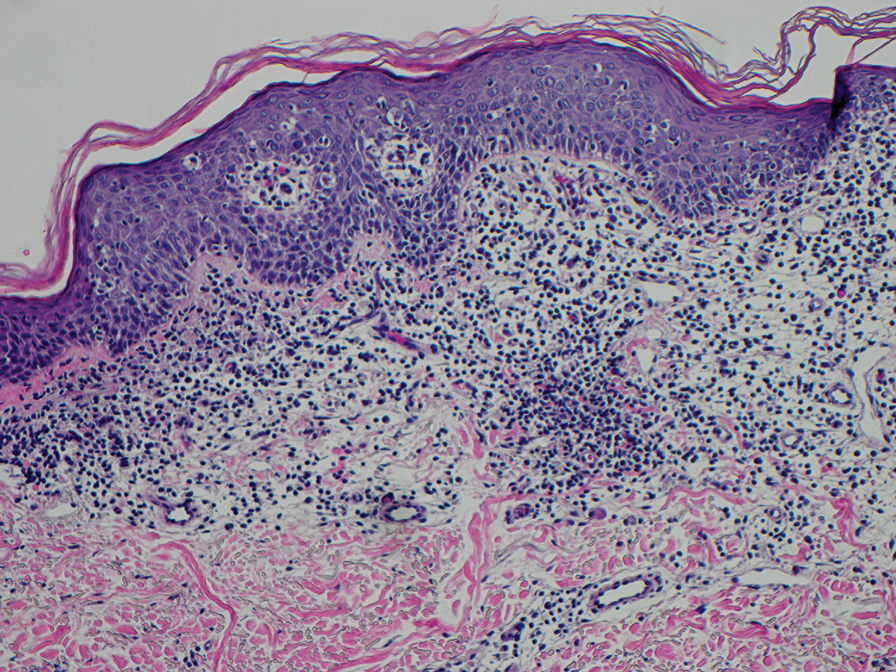

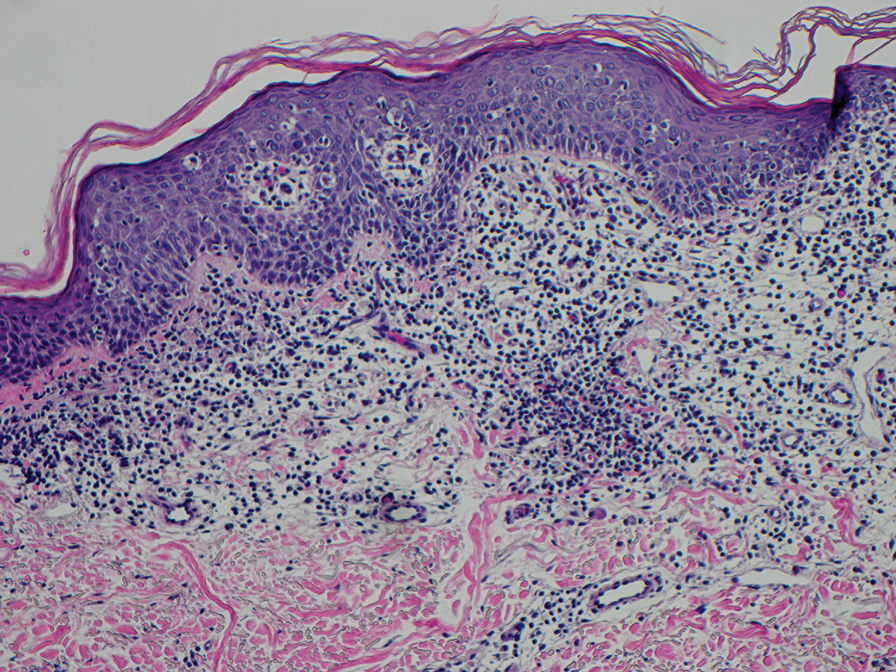

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common cutaneous lymphoma. There are patch, plaque, and tumor stages of MF, each of which exhibits various histopathologic findings.9 In early patch-stage MF, lymphocytes have perinuclear clearing, and the degree of lymphocytic infiltrate is out of proportion to the spongiosis present. Epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses often are present in the epidermis (Figure 3). In the plaque stage, there is a denser lymphoid infiltrate in a lichenoid pattern with epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses. The tumor stage shows a dense dermal lymphoid infiltrate with more atypia and typically a lack of epidermotropism. Rarely, MF can exhibit a granulomatous variant in which epithelioid histiocytes collect to form granulomas along with atypical lymphocytes.10

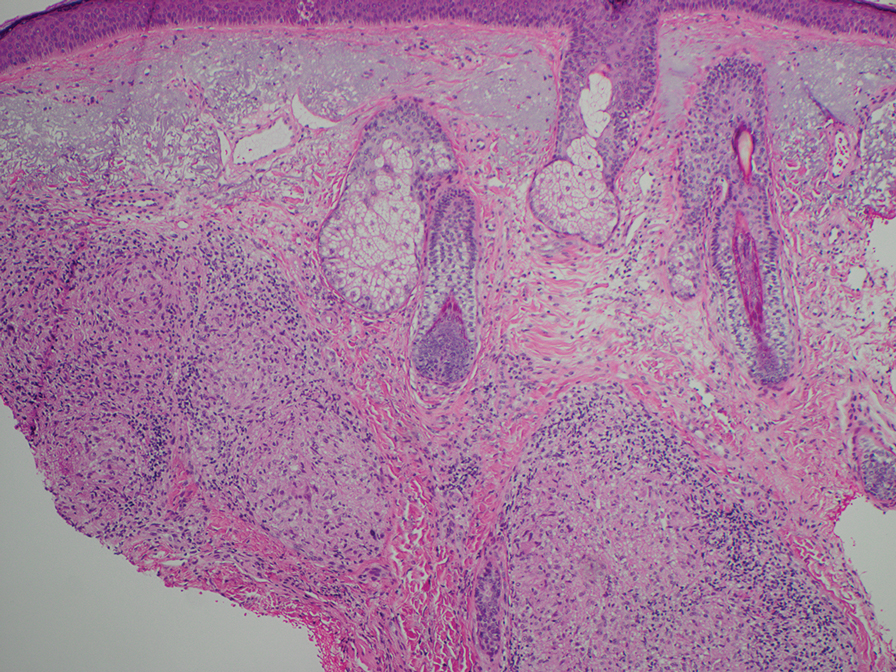

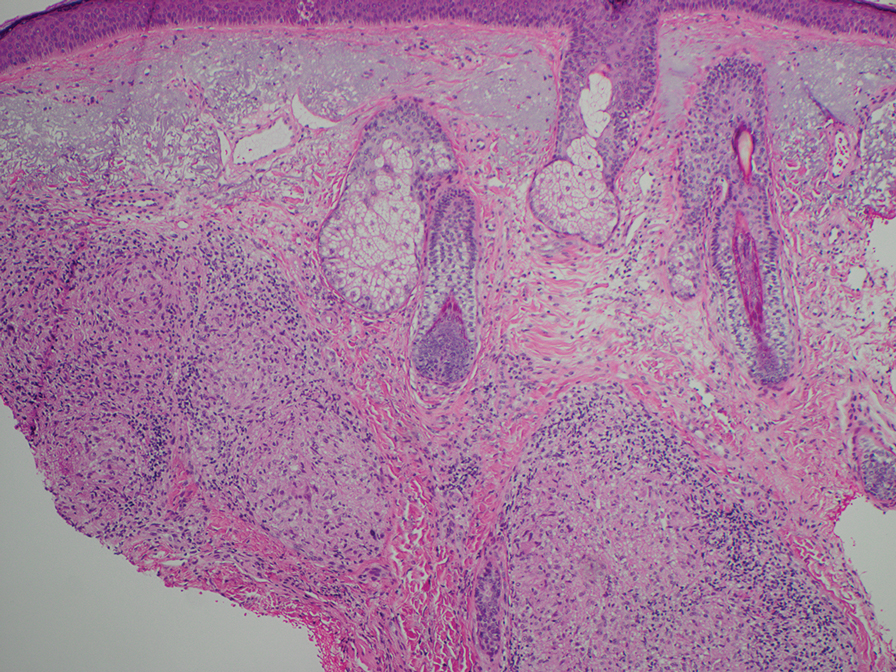

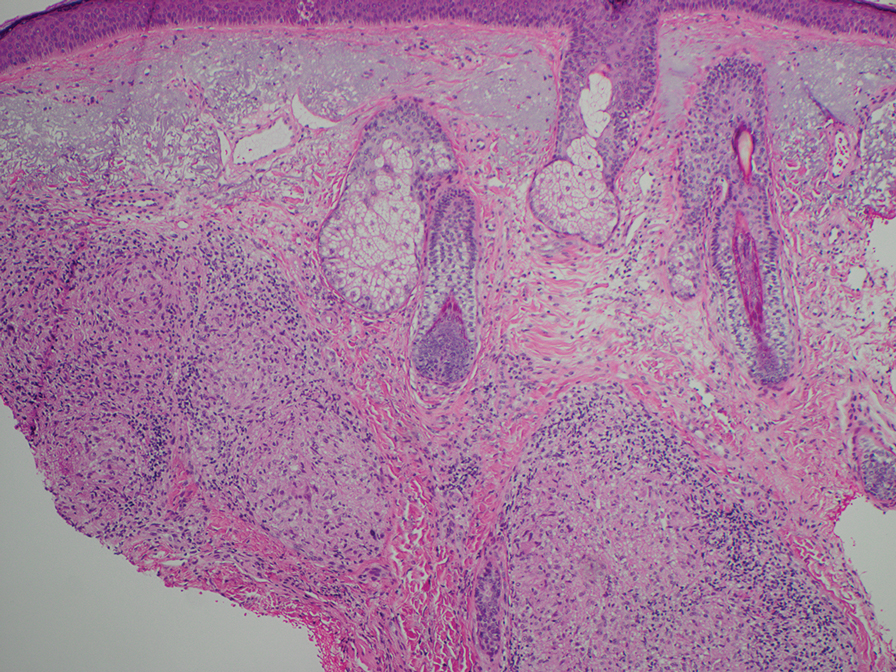

The diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis requires clinicopathologic corroboration. Histopathology demonstrates epithelioid histiocytes forming noncaseating granulomas with little to no lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4). There typically is no necrosis or necrobiosis as there is in GA. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be challenging histopathologically, and stains should be used to rule out infectious processes.4 Asteroid bodies— star-shaped eosinophilic inclusions within giant cells—may be present but are nonspecific for sarcoidosis.11 Schaumann bodies—inclusions of calcifications within giant cells—also may be present and can aid in diagnosis.12

- Kovich O, Burgin S. Generalized granuloma annulare [published online December 30, 2005]. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:23.

- Al Ameer MA, Al-Natour SH, Alsahaf HAA, et al. Eruptive granuloma annulare in an elderly man with diabetes [published online January 14, 2022]. Cureus. 2022;14:E21242. doi:10.7759/cureus.21242

- Howard A, White CR Jr. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, et al, eds. Dermatology. Mosby; 2003:1455.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Gore M, Winters ME. Erythema gyratum repens: a rare paraneoplastic rash. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:556-558. doi:10.5811/westjem.2010.11.2090

- Maymone MBC, Laughter M, Venkatesh S, et al. Leprosy: clinical aspects and diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1-14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.080

- Pedley JC, Harman DJ, Waudby H, et al. Leprosy in peripheral nerves: histopathological findings in 119 untreated patients in Nepal. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1980;43:198-204. doi:10.1136/jnnp.43.3.198

- Booth AV, Kovich OI. Lepromatous leprosy [published online January 27, 2007]. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:9.

- Robson A. The pathology of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21(2 suppl 1):9-12.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.46

- Azar HA, Lunardelli C. Collagen nature of asteroid bodies of giant cells in sarcoidosis. Am J Pathol. 1969;57:81-92.

- Sreeja C, Priyadarshini A, Premika, et al. Sarcoidosis—a review article. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2022;26:242-253. doi:10.4103 /jomfp.jomfp_373_21

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Annulare

The biopsies revealed palisading granulomatous dermatitis consistent with granuloma annulare (GA). This diagnosis was supported by the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. Although the pathogenesis of GA is unclear, it is a benign, self-limiting condition. Primarily affected sites include the trunk and forearms. Generalized GA (or GA with ≥10 lesions) may warrant workup for malignancy, as it may represent a paraneoplastic process.1 Histopathology reveals granulomas comprising a dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate as well as central mucin and nuclear debris. There are a few histologic subtypes of GA, including palisading and interstitial, which refer to the distribution of the histiocytic infiltrate.2,3 This case—with palisading histiocytes lining the collection of necrobiosis and mucin (bottom quiz image)—features palisading GA. Notably, GA exhibits central rather than diffuse mucin.4

Erythema gyratum repens is a paraneoplastic arcuate erythema that manifests as erythematous figurate, gyrate, or annular plaques exhibiting a trailing scale. Clinically, erythema gyratum repens spreads rapidly—as quickly as 1 cm/d—and can be extensive (as in this case). Histopathology ruled out this diagnosis in our patient. Nonspecific findings of acanthosis, parakeratosis, and superficial spongiosis can be found in erythema gyratum repens. A superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate may be seen in figurate erythemas (Figure 1).5 Unlike GA, this infiltrate does not form granulomas, is more superficial, and does not contain mucin.

Histopathology also can help establish the diagnosis of leprosy and its specific subtype, as leprosy exists on a spectrum from tuberculoid to lepromatous, with a great deal of overlap in between.6 Lepromatous leprosy has many cutaneous clinical presentations but typically manifests as erythematous papules or nodules. It is multibacillary, and these mycobacteria form clumps known as globi that can be seen on Fite stain.7 In lepromatous leprosy, there is a characteristic dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2) above which a Grenz zone can be seen.4,8 There are no well-formed granulomas in lepromatous leprosy, unlike in tuberculoid leprosy, which is paucibacillary and creates a granulomatous response surrounding nerves and adnexal structures.6

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common cutaneous lymphoma. There are patch, plaque, and tumor stages of MF, each of which exhibits various histopathologic findings.9 In early patch-stage MF, lymphocytes have perinuclear clearing, and the degree of lymphocytic infiltrate is out of proportion to the spongiosis present. Epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses often are present in the epidermis (Figure 3). In the plaque stage, there is a denser lymphoid infiltrate in a lichenoid pattern with epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses. The tumor stage shows a dense dermal lymphoid infiltrate with more atypia and typically a lack of epidermotropism. Rarely, MF can exhibit a granulomatous variant in which epithelioid histiocytes collect to form granulomas along with atypical lymphocytes.10

The diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis requires clinicopathologic corroboration. Histopathology demonstrates epithelioid histiocytes forming noncaseating granulomas with little to no lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4). There typically is no necrosis or necrobiosis as there is in GA. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be challenging histopathologically, and stains should be used to rule out infectious processes.4 Asteroid bodies— star-shaped eosinophilic inclusions within giant cells—may be present but are nonspecific for sarcoidosis.11 Schaumann bodies—inclusions of calcifications within giant cells—also may be present and can aid in diagnosis.12

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Annulare

The biopsies revealed palisading granulomatous dermatitis consistent with granuloma annulare (GA). This diagnosis was supported by the clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. Although the pathogenesis of GA is unclear, it is a benign, self-limiting condition. Primarily affected sites include the trunk and forearms. Generalized GA (or GA with ≥10 lesions) may warrant workup for malignancy, as it may represent a paraneoplastic process.1 Histopathology reveals granulomas comprising a dermal lymphohistiocytic infiltrate as well as central mucin and nuclear debris. There are a few histologic subtypes of GA, including palisading and interstitial, which refer to the distribution of the histiocytic infiltrate.2,3 This case—with palisading histiocytes lining the collection of necrobiosis and mucin (bottom quiz image)—features palisading GA. Notably, GA exhibits central rather than diffuse mucin.4

Erythema gyratum repens is a paraneoplastic arcuate erythema that manifests as erythematous figurate, gyrate, or annular plaques exhibiting a trailing scale. Clinically, erythema gyratum repens spreads rapidly—as quickly as 1 cm/d—and can be extensive (as in this case). Histopathology ruled out this diagnosis in our patient. Nonspecific findings of acanthosis, parakeratosis, and superficial spongiosis can be found in erythema gyratum repens. A superficial and deep perivascular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate may be seen in figurate erythemas (Figure 1).5 Unlike GA, this infiltrate does not form granulomas, is more superficial, and does not contain mucin.

Histopathology also can help establish the diagnosis of leprosy and its specific subtype, as leprosy exists on a spectrum from tuberculoid to lepromatous, with a great deal of overlap in between.6 Lepromatous leprosy has many cutaneous clinical presentations but typically manifests as erythematous papules or nodules. It is multibacillary, and these mycobacteria form clumps known as globi that can be seen on Fite stain.7 In lepromatous leprosy, there is a characteristic dense lymphohistiocytic infiltrate (Figure 2) above which a Grenz zone can be seen.4,8 There are no well-formed granulomas in lepromatous leprosy, unlike in tuberculoid leprosy, which is paucibacillary and creates a granulomatous response surrounding nerves and adnexal structures.6

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common cutaneous lymphoma. There are patch, plaque, and tumor stages of MF, each of which exhibits various histopathologic findings.9 In early patch-stage MF, lymphocytes have perinuclear clearing, and the degree of lymphocytic infiltrate is out of proportion to the spongiosis present. Epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses often are present in the epidermis (Figure 3). In the plaque stage, there is a denser lymphoid infiltrate in a lichenoid pattern with epidermotropism and Pautrier microabscesses. The tumor stage shows a dense dermal lymphoid infiltrate with more atypia and typically a lack of epidermotropism. Rarely, MF can exhibit a granulomatous variant in which epithelioid histiocytes collect to form granulomas along with atypical lymphocytes.10

The diagnosis of cutaneous sarcoidosis requires clinicopathologic corroboration. Histopathology demonstrates epithelioid histiocytes forming noncaseating granulomas with little to no lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 4). There typically is no necrosis or necrobiosis as there is in GA. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be challenging histopathologically, and stains should be used to rule out infectious processes.4 Asteroid bodies— star-shaped eosinophilic inclusions within giant cells—may be present but are nonspecific for sarcoidosis.11 Schaumann bodies—inclusions of calcifications within giant cells—also may be present and can aid in diagnosis.12

- Kovich O, Burgin S. Generalized granuloma annulare [published online December 30, 2005]. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:23.

- Al Ameer MA, Al-Natour SH, Alsahaf HAA, et al. Eruptive granuloma annulare in an elderly man with diabetes [published online January 14, 2022]. Cureus. 2022;14:E21242. doi:10.7759/cureus.21242

- Howard A, White CR Jr. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, et al, eds. Dermatology. Mosby; 2003:1455.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Gore M, Winters ME. Erythema gyratum repens: a rare paraneoplastic rash. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:556-558. doi:10.5811/westjem.2010.11.2090

- Maymone MBC, Laughter M, Venkatesh S, et al. Leprosy: clinical aspects and diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1-14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.080

- Pedley JC, Harman DJ, Waudby H, et al. Leprosy in peripheral nerves: histopathological findings in 119 untreated patients in Nepal. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1980;43:198-204. doi:10.1136/jnnp.43.3.198

- Booth AV, Kovich OI. Lepromatous leprosy [published online January 27, 2007]. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:9.

- Robson A. The pathology of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21(2 suppl 1):9-12.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.46

- Azar HA, Lunardelli C. Collagen nature of asteroid bodies of giant cells in sarcoidosis. Am J Pathol. 1969;57:81-92.

- Sreeja C, Priyadarshini A, Premika, et al. Sarcoidosis—a review article. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2022;26:242-253. doi:10.4103 /jomfp.jomfp_373_21

- Kovich O, Burgin S. Generalized granuloma annulare [published online December 30, 2005]. Dermatol Online J. 2005;11:23.

- Al Ameer MA, Al-Natour SH, Alsahaf HAA, et al. Eruptive granuloma annulare in an elderly man with diabetes [published online January 14, 2022]. Cureus. 2022;14:E21242. doi:10.7759/cureus.21242

- Howard A, White CR Jr. Non-infectious granulomas. In: Bolognia JL, et al, eds. Dermatology. Mosby; 2003:1455.

- Elston DM, Ferringer T, Ko CJ, et al. Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2018.

- Gore M, Winters ME. Erythema gyratum repens: a rare paraneoplastic rash. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:556-558. doi:10.5811/westjem.2010.11.2090

- Maymone MBC, Laughter M, Venkatesh S, et al. Leprosy: clinical aspects and diagnostic techniques. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:1-14. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.080

- Pedley JC, Harman DJ, Waudby H, et al. Leprosy in peripheral nerves: histopathological findings in 119 untreated patients in Nepal. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1980;43:198-204. doi:10.1136/jnnp.43.3.198

- Booth AV, Kovich OI. Lepromatous leprosy [published online January 27, 2007]. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13:9.

- Robson A. The pathology of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21(2 suppl 1):9-12.

- Kempf W, Ostheeren-Michaelis S, Paulli M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin: a multicenter study of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Histopathology Task Force Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:1609-1617. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2008.46

- Azar HA, Lunardelli C. Collagen nature of asteroid bodies of giant cells in sarcoidosis. Am J Pathol. 1969;57:81-92.

- Sreeja C, Priyadarshini A, Premika, et al. Sarcoidosis—a review article. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2022;26:242-253. doi:10.4103 /jomfp.jomfp_373_21

An 84-year-old man presented to the clinic for evaluation of a pruritic rash on the back of 6 months’ duration that spread to the neck and chest over the past 2 months and then to the abdomen and thighs more recently. His primary care provider prescribed a 1-week course of oral steroids and steroid cream. The oral medication did not help, but the cream alleviated the pruritus. He had a medical history of coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. He also had a rash on the forearms that had waxed and waned for many years but was not associated with pruritus. He had not sought medical care for the rash and had never treated it. Physical examination revealed pink to violaceous annular plaques with central clearing and raised borders that coalesced into larger plaques on the trunk (top). Dusky, scaly, pink plaques were present on the dorsal forearms. Three punch biopsies—2 from the upper back (bottom) and 1 from the left forearm—all demonstrated consistent findings.

Alopecia Universalis Treated With Tofacitinib: The Role of JAK/STAT Inhibitors in Hair Regrowth

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease that immunopathogenetically is thought to be due to breakdown of the immune privilege of the proximal hair follicle during the anagen growth phase. Alopecia areata has been reported to have a lifetime prevalence of 1.7%.1 Recent studies have specifically identified cytotoxic CD8+ NKG2D+ T cells as being responsible for the activation of AA.2-4 Two interleukins—IL-2 and IL-15—have been implicated to be cytotoxic sensitizers allowing CD8+ T cells to secrete IFN-γ and recognize autoantigens via major histocompatibility complex class I.5,6 Janus kinases (JAKs) are enzymes that play major roles in many different molecular processes. Specifically, JAK1/3 has been determined to arbitrate IL-15 activation of receptors on CD8+ T cells.7 These cells then interact with CD4 T cells, mast cells, and other inflammatory cells to cause destruction of the hair follicle without damage to the keratinocyte and melanocyte stem cells, allowing for reversible yet relapsing hair loss.8

Treatment of AA is difficult, requiring patience and strict compliance while taking into account duration of disease, age at presentation, site involvement, patient expectations, cost and insurance coverage, prior therapies, and any comorbidities. At the time of this case, no US Food and Drug Administration–approved drug regimen existed for the treatment of AA, and, to date, no treatment is preventative.4 We present a case of a patient with alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that was refractory to intralesional triamcinolone, clobetasol, minoxidil, and UVB brush therapy yet was successfully treated with tofacitinib.

Case Report

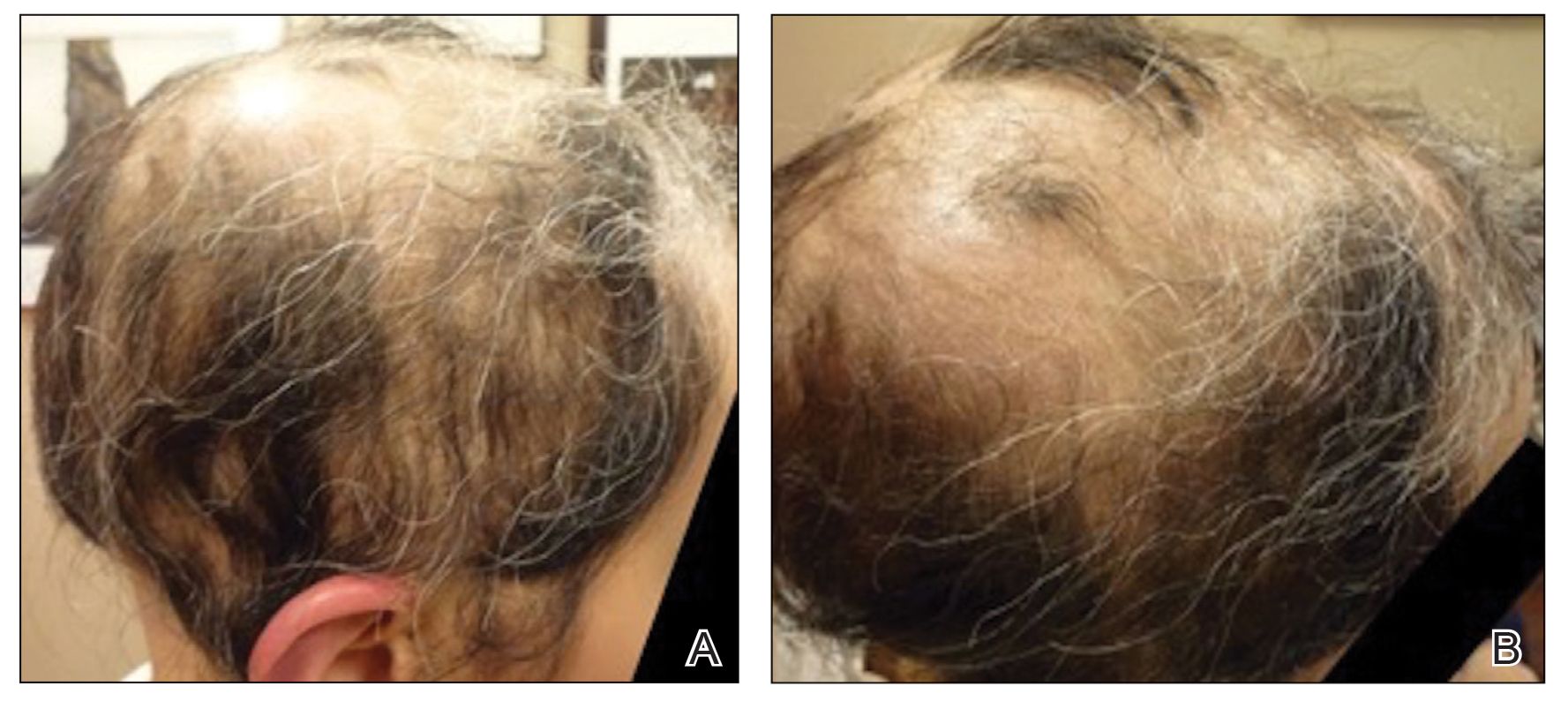

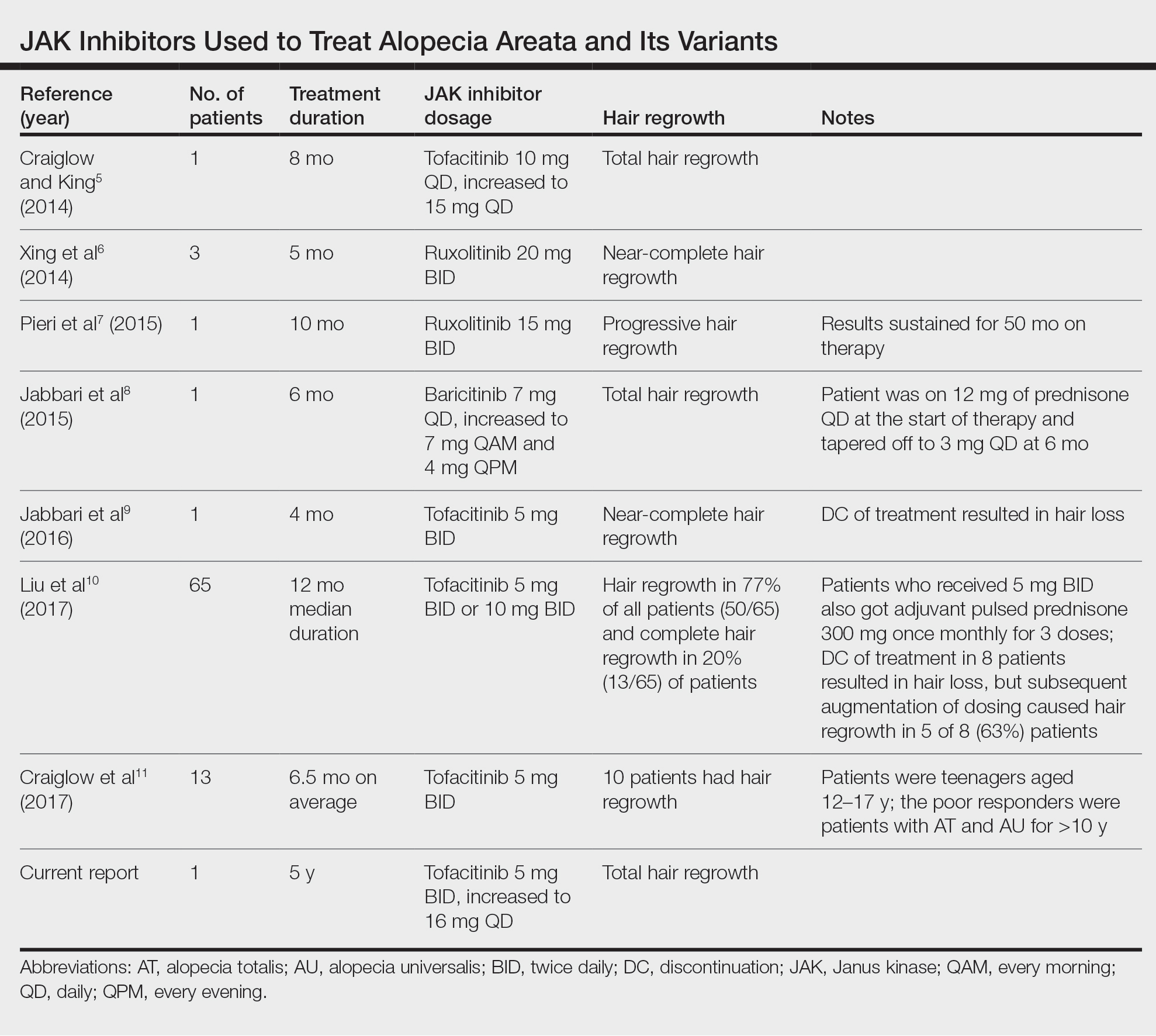

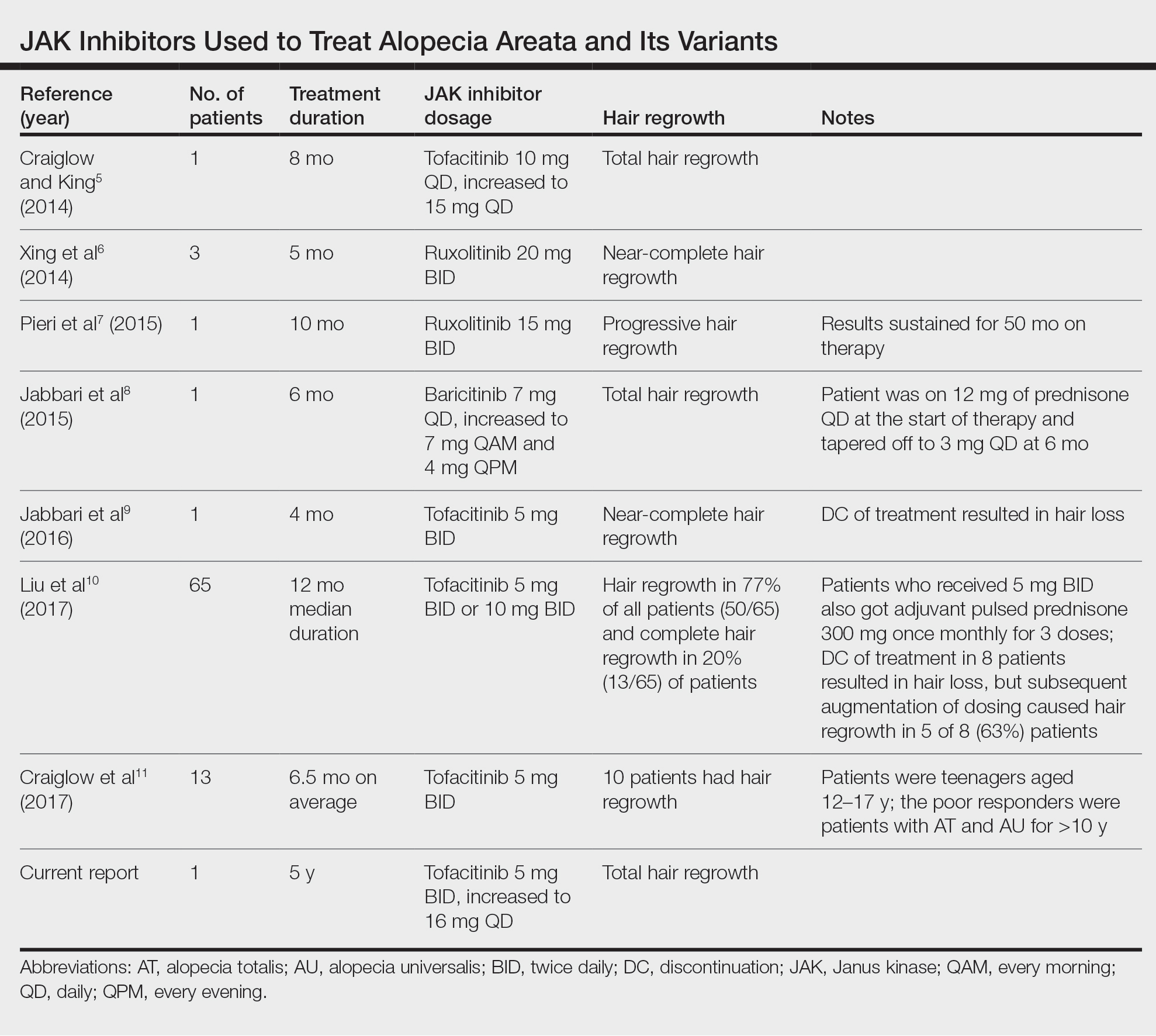

A 29-year-old otherwise-healthy woman presented to our clinic for treatment of alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that flared intermittently despite various treatments. Her medical history was unremarkable; however, she had a brother with alopecia universalis. She had no family history of any other autoimmune disorders. At the current presentation, the patient was known to have alopecia universalis with scant evidence of exclamation-point hairs on dermoscopy. Her treatment plan at this point consisted of intralesional triamcinolone to the active areas at 10 mg/mL every 4 weeks, plus clobetasol foam 0.05% at bedtime, minoxidil foam 5% at bedtime, and a UVB brush 3 times a week for 6 months before progressing to universalis type because of hair loss in the eyebrows and eyelashes. This treatment plan continued for 1 year with minimal improvement of the alopecia (Figure 1).

The patient was dissatisfied and wanted to discontinue therapy. Because these treatment options were exhausted with minimal benefit, the patient was then considered for treatment with tofacitinib. Baseline studies were performed, including purified protein derivative, complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid profile, and liver function tests, all of which were within reference range. Insurance initially denied coverage of this therapy; a prior authorization was subsequently submitted and denied. A letter of medical necessity was then proposed, and approval for tofacitinib was finally granted. The patient was started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and was monitored every 2 months with a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panels, and liver function tests. She had a platelet count of 112,000/μL (reference range, 150,000–450,000/μL) at baseline, and continued monitoring revealed a platelet count of 83,000 after 7 months of treatment. This platelet abnormality was evaluated by a hematologist and found to be within reference range; subsequent monitoring did not reveal any abnormalities.

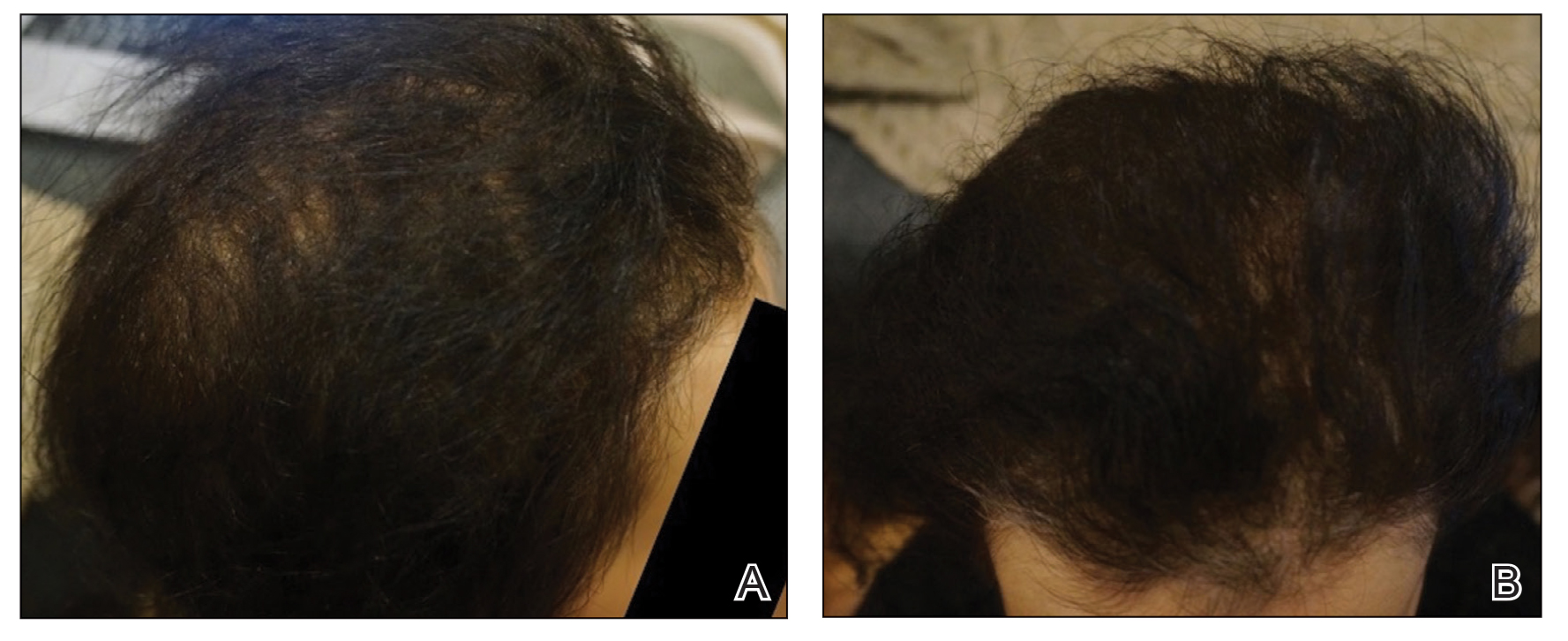

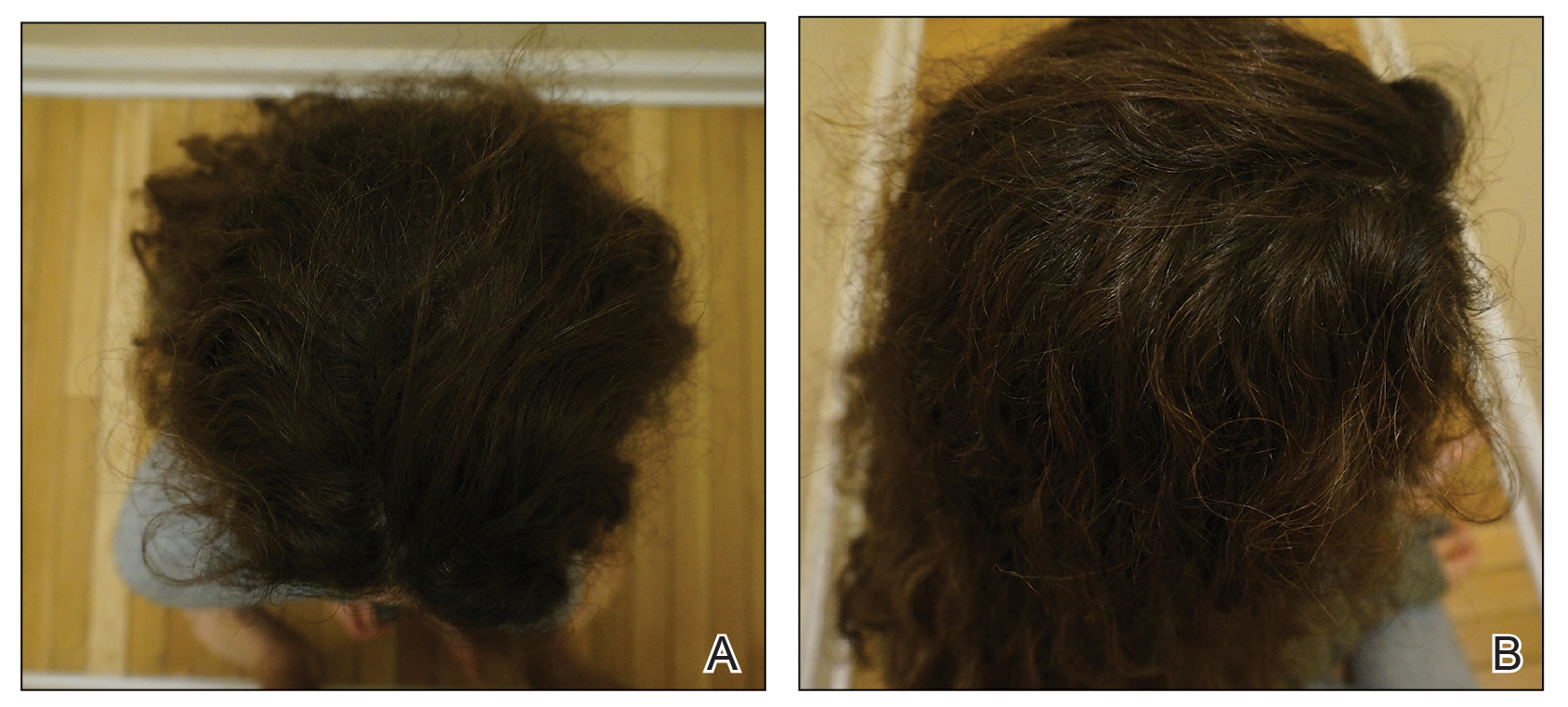

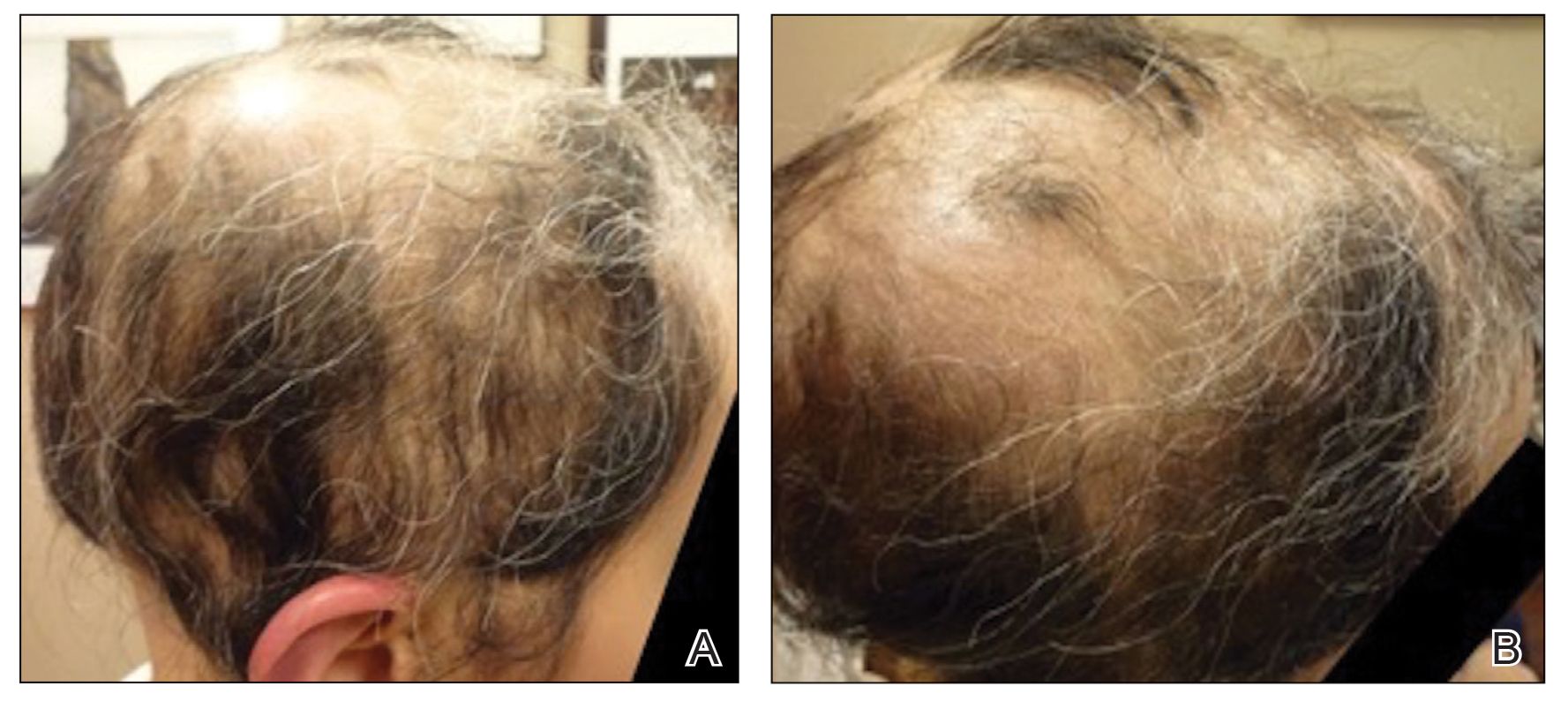

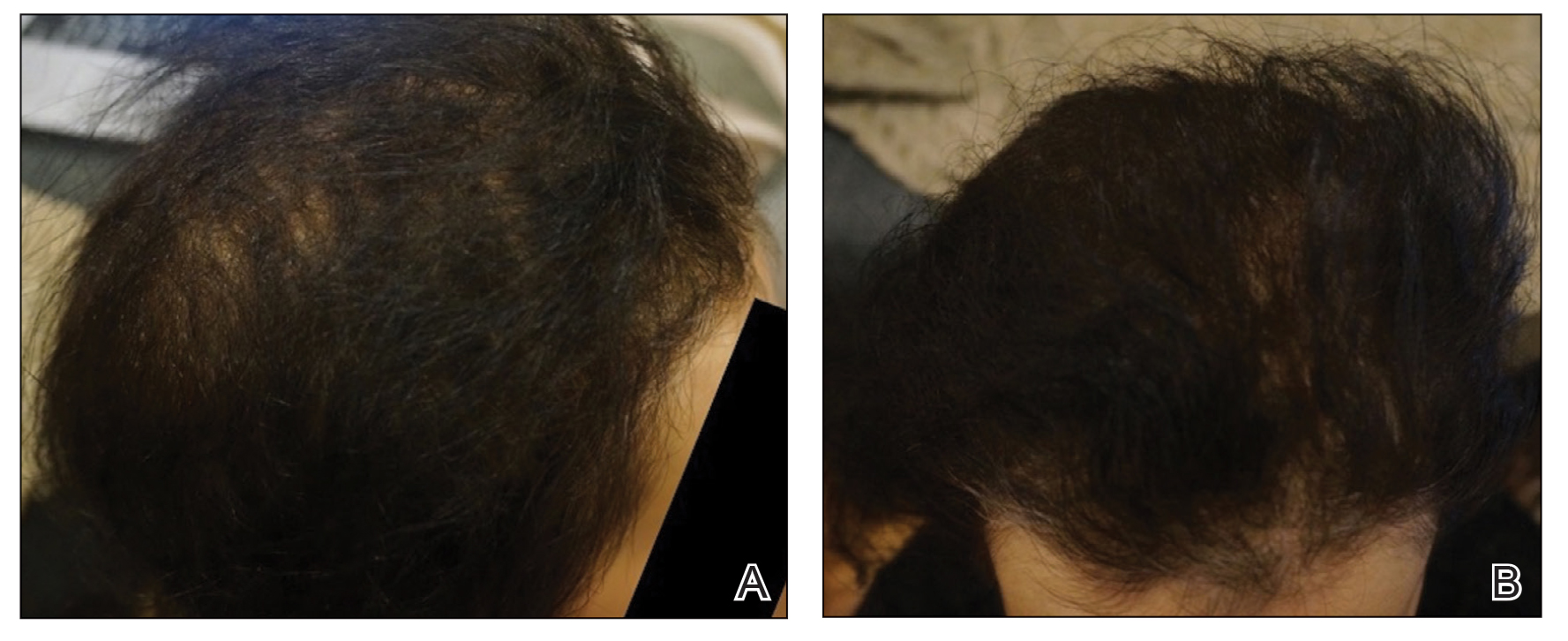

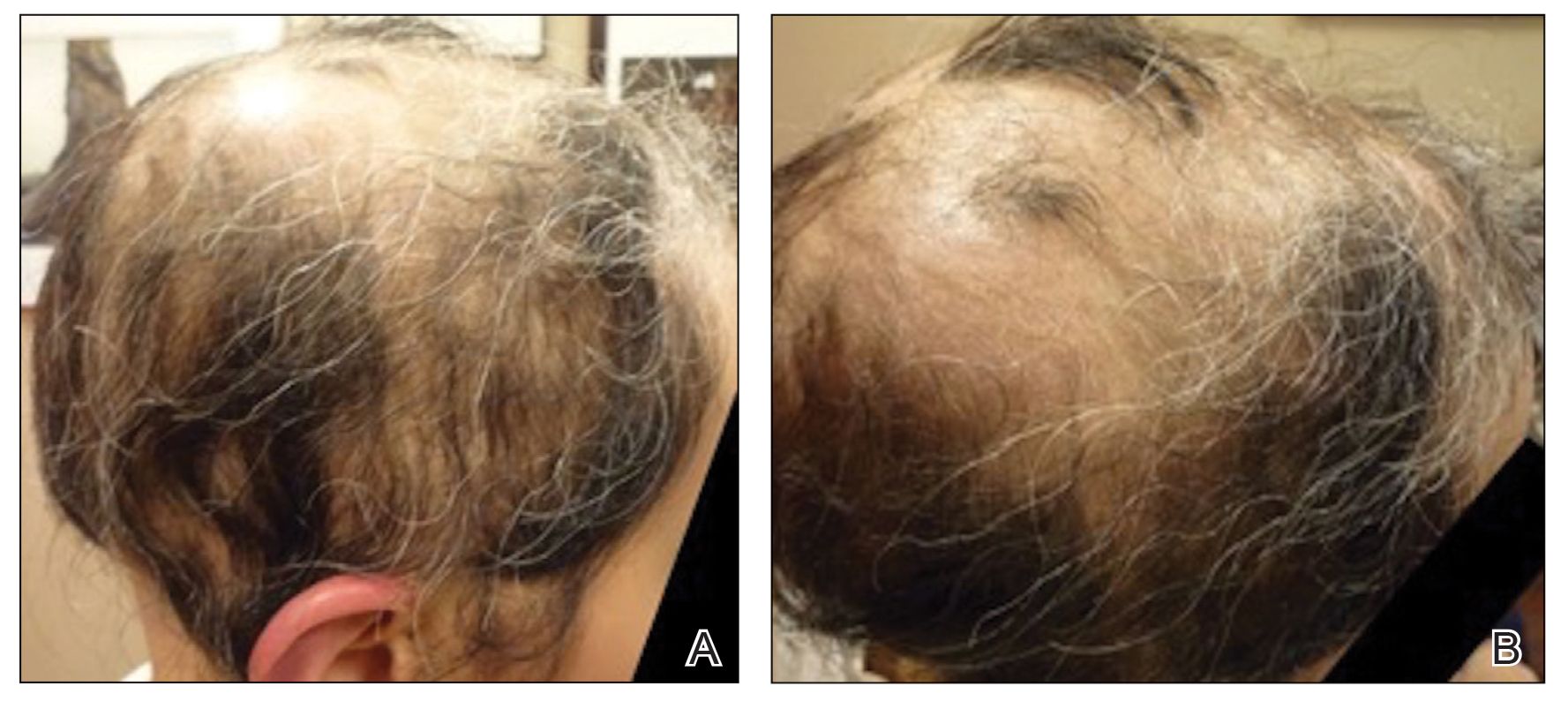

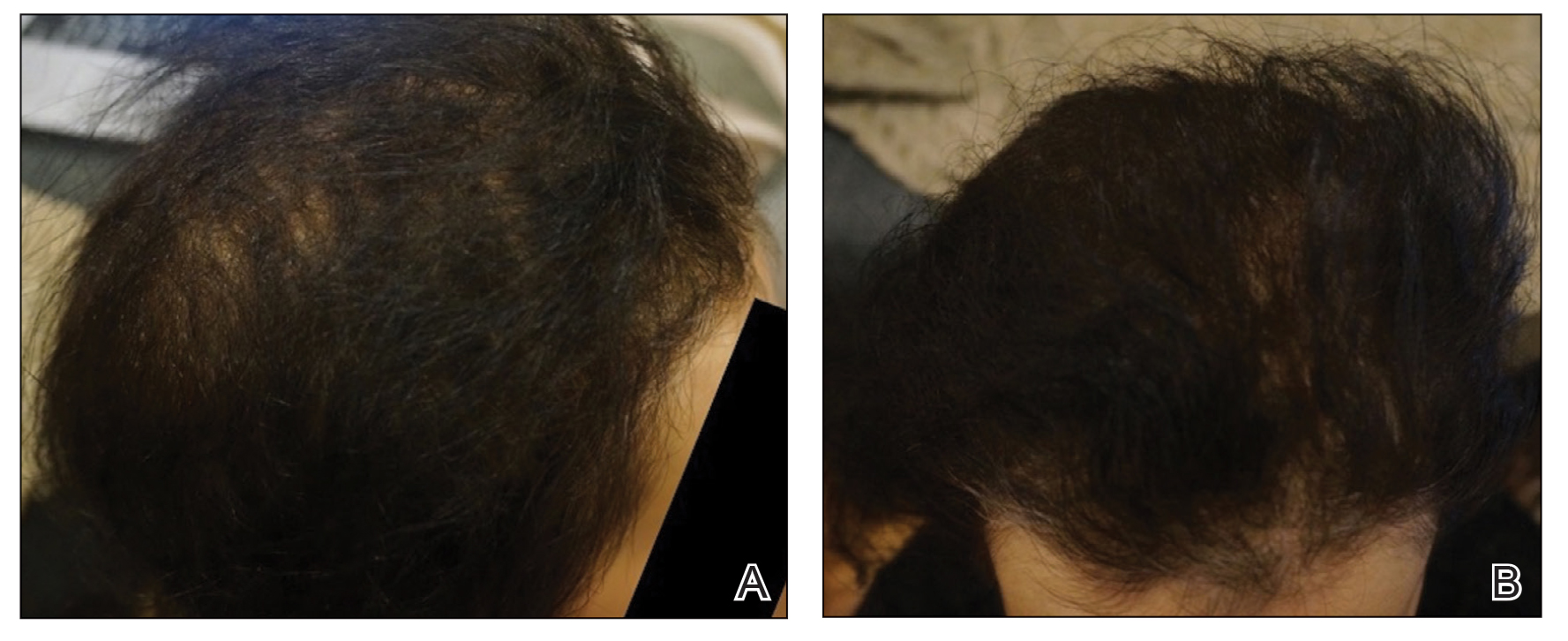

Initial hair growth on the scalp was diffuse with thin, white to light brown hairs in areas of hair loss at months 1 and 2, with progressive hair growth over months 3 to 7. Eyebrow hair growth was noted beginning at month 6. One year later, only hair regrowth occurred without any adverse events (Figure 2). After 5 years of treatment, the patient had a full head of thick hair (Figure 3). The tofacitinib dosage was 5 mg twice daily at initiation, and after 1 year increased to 10 mg twice daily. Her medical insurance subsequently changed and the regimen was adjusted to an 11-mg tablet and 5-mg tablet daily. She remained on this regimen with success.

Comment

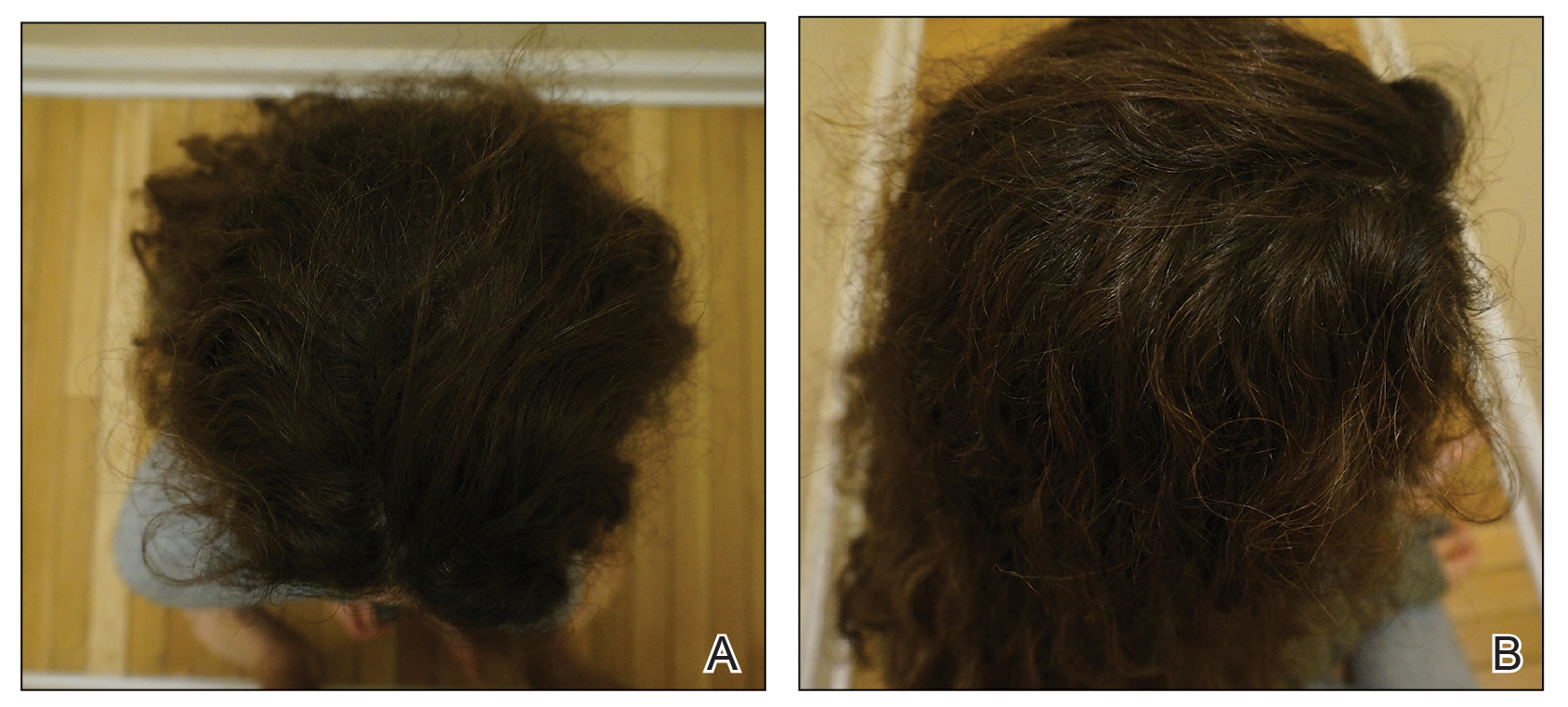

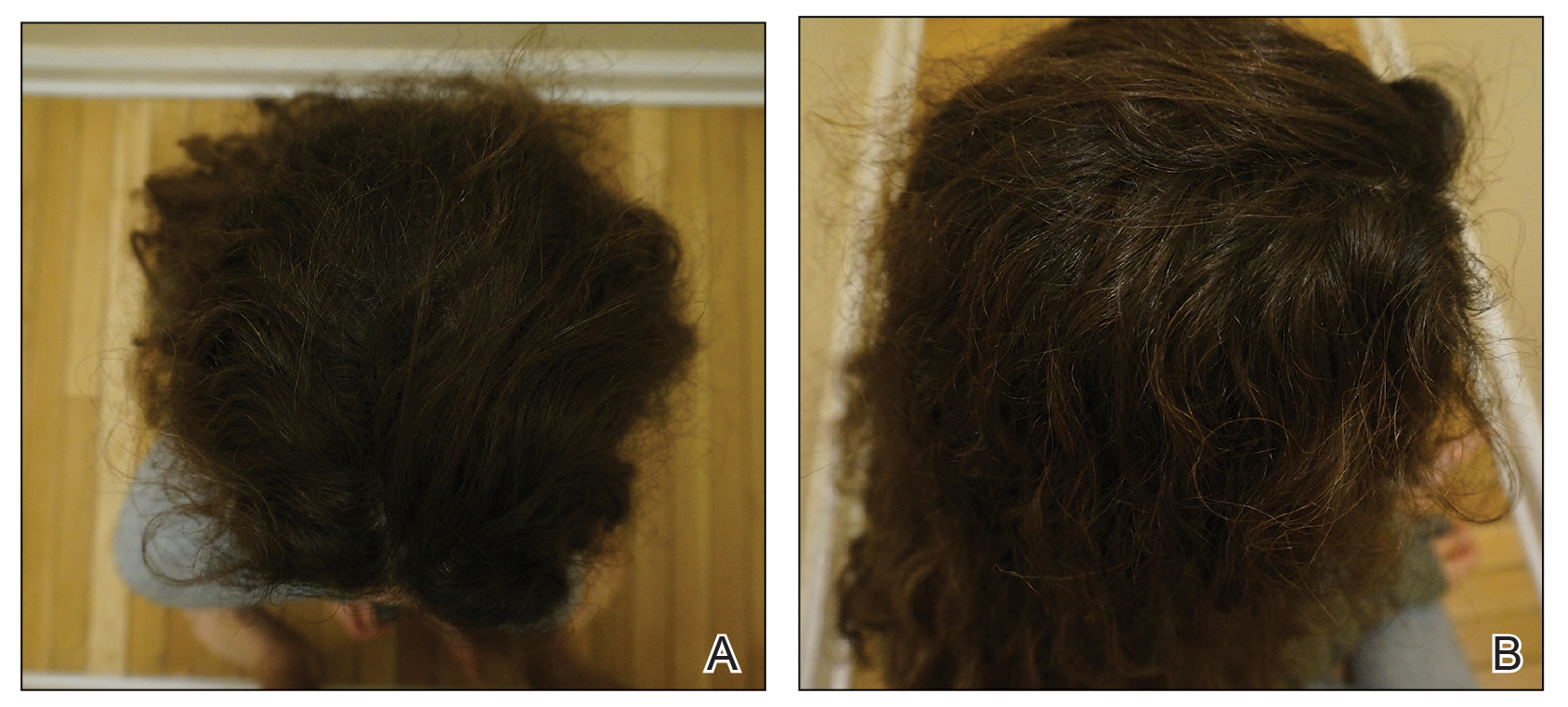

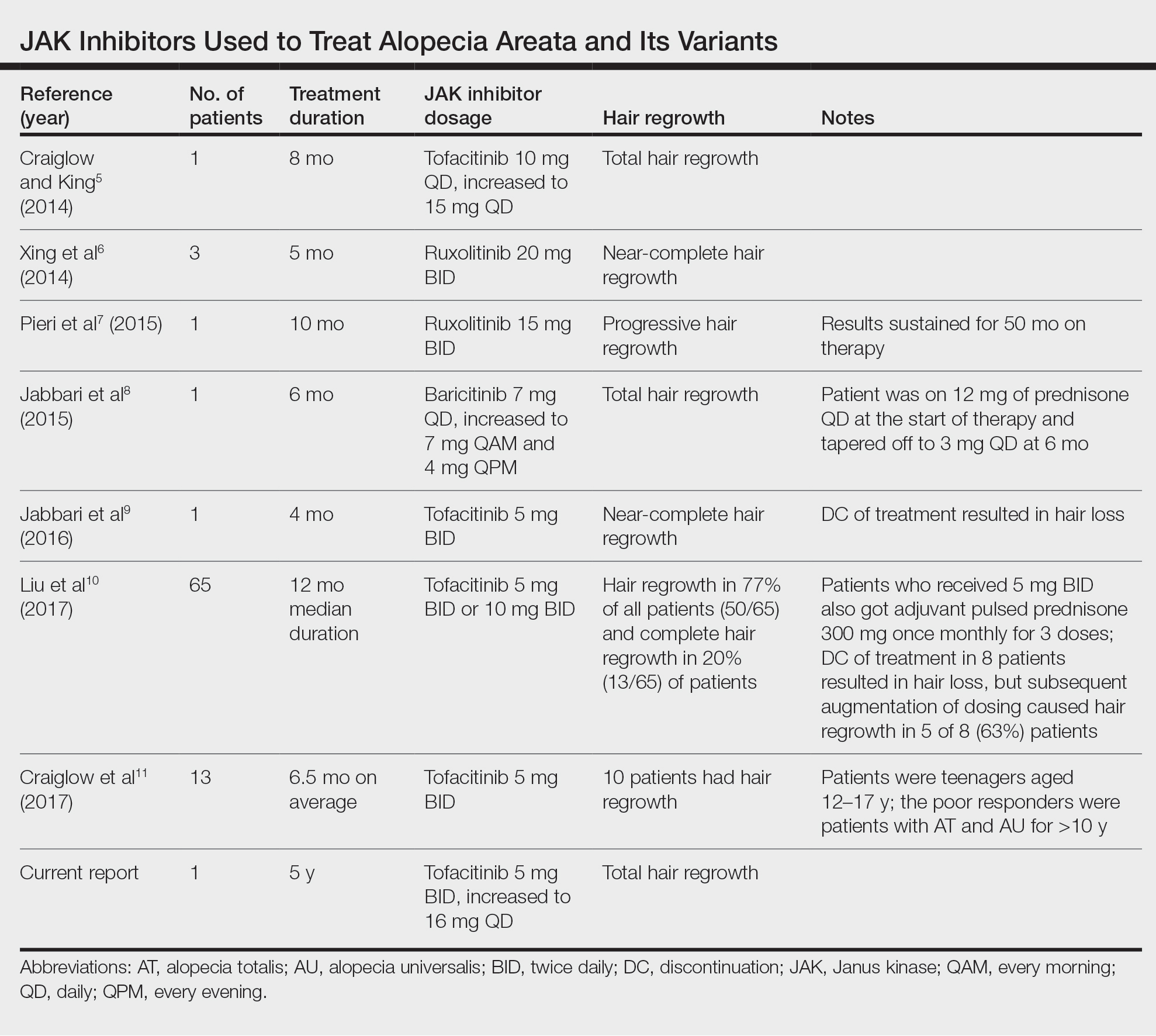

Use of JAK Inhibitors—Reports and studies have shed light on the use and efficacy of JAK inhibitors in AA (Table).5-11 Tofacitinib is a selective JAK1/3 inhibitor that predominantly inhibits JAK3 but also inhibits JAK1, albeit to a lesser degree, which interferes with the JAK/STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) cascade responsible for the production, differentiation, and function of various B cells, T cells, and natural killer cells.2 Although it was developed for the management of allograft rejection, tofacitinib has made headway in rheumatology for treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis who are unable to take or are not responding to methotrexate.2 Since 2014, tofacitinib has been introduced to the therapeutic realm for AA but is not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.3,4

In 2014, Craiglow and King5 reported use of tofacitinib with dosages beginning at 10 mg/d and increasing to 15 mg/d in a patient with alopecia universalis and psoriasis. Total hair regrowth was noted after 8 months of therapy.5 Xing et al6 described 3 patients treated with ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis, at an oral dose of 20 mg twice daily with near-complete hair regrowth after 5 months of treatment.6 Biopsies from lesions at baseline and after 3 months of therapy revealed a reduction in perifollicular T cells and in HLA class I and II expression in follicles.6 A patient in Italy with essential thrombocythemia and concurrent alopecia universalis was enrolled in a clinical trial with ruxolitinib and was treated with 15 mg twice daily. After 10 months of treatment, the patient had progressive hair regrowth that was sustained for more than 50 months of therapy.7 Baricitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, was used in a 17-year-old adolescent boy to assess efficacy of the drug in

A recent retrospective study assessing response to tofacitinib in adults with AA (>40% hair loss), alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, and stable or progressive diseases for at least 6 months determined a clinical response in 50 of 65 (77%) patients, with 13 patients exhibiting a complete response.10 Patients in this study were started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily with the addition of adjuvant pulsed prednisone (300 mg once monthly for 3 doses) with or without doubled dosing of tofacitinib if they had a halt in hair regrowth. This study demonstrated some benefit when pulsed prednisone was combined with the daily tofacitinib therapy. However, the study emphasized the importance of maintenance therapy, as 8 patients experienced hair loss with discontinuation after previously having hair regrowth; 5 (63%) of these patients experienced regrowth with augmentation of dosing or addition of adjuvant therapy.10

Another group of investigators assessed the efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg in 13 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, most with alopecia universalis (46% [6/13]); 10 of 13 (77%) patients responded to treatment with a mean duration of 6.5 months. The patients who had alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis for more than 10 years were poor responders to tofacitinib, and in fact, 1 of 13 (33%) patients in the study who did not respond to therapy had disease for 12 years.11 Therefore, starting tofacitinib either long-term or intermittently should be considered in children diagnosed early with severe AA, alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis to prevent irreversible hair loss or progressive disease12,13; however, further data are required to assess efficacy and long-term benefits of this type of regimen.

Safety Profile—Widespread use of a medication is determined not only by its efficacy profile but also its safety profile. With any medication that exhibits immunosuppressive effects, adverse events must be considered and thoroughly discussed with patients and their primary care physicians. A prospective, open-label, single-arm trial examined the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily in the treatment of AA and its more severe forms over 3 months.12 Of the 66 patients who completed the trial, 64% (42/66) exhibited a positive response to tofacitinib. Relapse was noted in 8.5 weeks after discontinuation of tofacitinib, reiterating the potential need for a maintenance regimen. In this study, 25.8% (17/66) of patients experienced infections as adverse events including (in decreasing order) upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, herpes zoster, conjunctivitis, bronchitis, mononucleosis, and paronychia. No reports of new or recurrent malignancy were noted. Other more constitutional adverse events were noted including headaches, abdominal pain, acne, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, pruritus, hot flashes, cough, folliculitis, weight gain, dry eyes, and amenorrhea. One patient with a pre-existing liver condition experienced transaminitis that resolved with weight loss. There also were noted increases in low- and high-density lipoprotein levels.12 Our patient with baseline thrombocytopenia had mild drops in platelet count that subsequently stabilized and did not result in any bleeding abnormalities.

Duration of Therapy—Tofacitinib has demonstrated some preliminary success in the management of AA, but the appropriate duration of treatment requires further investigation. Our patient has been on tofacitinib for more than 5 years. She started at a total dosage of 10 mg/d, which increased to 16 mg/d. Initial dosing with maintenance regimens needs to be established for further widespread use to maximize benefit and minimize harm.

At what point do we decide to continue or stop treatment in patients who do not respond as expected or plateau? This is another critical question; our patient had periods of slowed growth and plateauing, but knowing the risks and benefits, she continued the medication and eventually experienced improved regrowth again.

Conclusion

Throughout the literature and in our patient, tofacitinib has demonstrated efficacy in treating AA. When other conventional therapies have failed, use of tofacitinib should be considered.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmstead County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628-633.

- Borazan NH, Furst DE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, nonopioid analgesics, & drugs used in gout. In: Katzung BG, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 13th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2015:618-642.

- Shapiro J. Current treatment of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S42-S44.

- Shapiro J. Dermatologic therapy: alopecia areata update. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:301.

- Craiglow BG, King BA. Killing two birds with one stone: oral tofacitinib reverses alopecia universalis in a patient with plaque psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2988-2990.

- Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med. 2014;20:1043-1049.

- Pieri L, Guglielmelli P, Vannucchi AM. Ruxolitinib-induced reversal of alopecia universalis in a patient with essential thrombocythemia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:82-83.

- Jabbari A, Dai Z, Xing L, et al. Reversal of alopecia areata following treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. EbioMedicine. 2015;2:351-355.

- Jabbari A, Nguyen N, Cerise JE, et al. Treatment of an alopecia areata patient with tofacitinib results in regrowth of hair and changes in serum and skin biomarkers. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:642-643.

- Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: a study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:22-28.

- Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:29-32.

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:E89776.

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Emerging drugs for alopecia areata: JAK inhibitors. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2018;23:77-81.

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease that immunopathogenetically is thought to be due to breakdown of the immune privilege of the proximal hair follicle during the anagen growth phase. Alopecia areata has been reported to have a lifetime prevalence of 1.7%.1 Recent studies have specifically identified cytotoxic CD8+ NKG2D+ T cells as being responsible for the activation of AA.2-4 Two interleukins—IL-2 and IL-15—have been implicated to be cytotoxic sensitizers allowing CD8+ T cells to secrete IFN-γ and recognize autoantigens via major histocompatibility complex class I.5,6 Janus kinases (JAKs) are enzymes that play major roles in many different molecular processes. Specifically, JAK1/3 has been determined to arbitrate IL-15 activation of receptors on CD8+ T cells.7 These cells then interact with CD4 T cells, mast cells, and other inflammatory cells to cause destruction of the hair follicle without damage to the keratinocyte and melanocyte stem cells, allowing for reversible yet relapsing hair loss.8

Treatment of AA is difficult, requiring patience and strict compliance while taking into account duration of disease, age at presentation, site involvement, patient expectations, cost and insurance coverage, prior therapies, and any comorbidities. At the time of this case, no US Food and Drug Administration–approved drug regimen existed for the treatment of AA, and, to date, no treatment is preventative.4 We present a case of a patient with alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that was refractory to intralesional triamcinolone, clobetasol, minoxidil, and UVB brush therapy yet was successfully treated with tofacitinib.

Case Report

A 29-year-old otherwise-healthy woman presented to our clinic for treatment of alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that flared intermittently despite various treatments. Her medical history was unremarkable; however, she had a brother with alopecia universalis. She had no family history of any other autoimmune disorders. At the current presentation, the patient was known to have alopecia universalis with scant evidence of exclamation-point hairs on dermoscopy. Her treatment plan at this point consisted of intralesional triamcinolone to the active areas at 10 mg/mL every 4 weeks, plus clobetasol foam 0.05% at bedtime, minoxidil foam 5% at bedtime, and a UVB brush 3 times a week for 6 months before progressing to universalis type because of hair loss in the eyebrows and eyelashes. This treatment plan continued for 1 year with minimal improvement of the alopecia (Figure 1).

The patient was dissatisfied and wanted to discontinue therapy. Because these treatment options were exhausted with minimal benefit, the patient was then considered for treatment with tofacitinib. Baseline studies were performed, including purified protein derivative, complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid profile, and liver function tests, all of which were within reference range. Insurance initially denied coverage of this therapy; a prior authorization was subsequently submitted and denied. A letter of medical necessity was then proposed, and approval for tofacitinib was finally granted. The patient was started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and was monitored every 2 months with a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panels, and liver function tests. She had a platelet count of 112,000/μL (reference range, 150,000–450,000/μL) at baseline, and continued monitoring revealed a platelet count of 83,000 after 7 months of treatment. This platelet abnormality was evaluated by a hematologist and found to be within reference range; subsequent monitoring did not reveal any abnormalities.

Initial hair growth on the scalp was diffuse with thin, white to light brown hairs in areas of hair loss at months 1 and 2, with progressive hair growth over months 3 to 7. Eyebrow hair growth was noted beginning at month 6. One year later, only hair regrowth occurred without any adverse events (Figure 2). After 5 years of treatment, the patient had a full head of thick hair (Figure 3). The tofacitinib dosage was 5 mg twice daily at initiation, and after 1 year increased to 10 mg twice daily. Her medical insurance subsequently changed and the regimen was adjusted to an 11-mg tablet and 5-mg tablet daily. She remained on this regimen with success.

Comment

Use of JAK Inhibitors—Reports and studies have shed light on the use and efficacy of JAK inhibitors in AA (Table).5-11 Tofacitinib is a selective JAK1/3 inhibitor that predominantly inhibits JAK3 but also inhibits JAK1, albeit to a lesser degree, which interferes with the JAK/STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) cascade responsible for the production, differentiation, and function of various B cells, T cells, and natural killer cells.2 Although it was developed for the management of allograft rejection, tofacitinib has made headway in rheumatology for treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis who are unable to take or are not responding to methotrexate.2 Since 2014, tofacitinib has been introduced to the therapeutic realm for AA but is not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.3,4

In 2014, Craiglow and King5 reported use of tofacitinib with dosages beginning at 10 mg/d and increasing to 15 mg/d in a patient with alopecia universalis and psoriasis. Total hair regrowth was noted after 8 months of therapy.5 Xing et al6 described 3 patients treated with ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis, at an oral dose of 20 mg twice daily with near-complete hair regrowth after 5 months of treatment.6 Biopsies from lesions at baseline and after 3 months of therapy revealed a reduction in perifollicular T cells and in HLA class I and II expression in follicles.6 A patient in Italy with essential thrombocythemia and concurrent alopecia universalis was enrolled in a clinical trial with ruxolitinib and was treated with 15 mg twice daily. After 10 months of treatment, the patient had progressive hair regrowth that was sustained for more than 50 months of therapy.7 Baricitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, was used in a 17-year-old adolescent boy to assess efficacy of the drug in

A recent retrospective study assessing response to tofacitinib in adults with AA (>40% hair loss), alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, and stable or progressive diseases for at least 6 months determined a clinical response in 50 of 65 (77%) patients, with 13 patients exhibiting a complete response.10 Patients in this study were started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily with the addition of adjuvant pulsed prednisone (300 mg once monthly for 3 doses) with or without doubled dosing of tofacitinib if they had a halt in hair regrowth. This study demonstrated some benefit when pulsed prednisone was combined with the daily tofacitinib therapy. However, the study emphasized the importance of maintenance therapy, as 8 patients experienced hair loss with discontinuation after previously having hair regrowth; 5 (63%) of these patients experienced regrowth with augmentation of dosing or addition of adjuvant therapy.10

Another group of investigators assessed the efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg in 13 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, most with alopecia universalis (46% [6/13]); 10 of 13 (77%) patients responded to treatment with a mean duration of 6.5 months. The patients who had alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis for more than 10 years were poor responders to tofacitinib, and in fact, 1 of 13 (33%) patients in the study who did not respond to therapy had disease for 12 years.11 Therefore, starting tofacitinib either long-term or intermittently should be considered in children diagnosed early with severe AA, alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis to prevent irreversible hair loss or progressive disease12,13; however, further data are required to assess efficacy and long-term benefits of this type of regimen.

Safety Profile—Widespread use of a medication is determined not only by its efficacy profile but also its safety profile. With any medication that exhibits immunosuppressive effects, adverse events must be considered and thoroughly discussed with patients and their primary care physicians. A prospective, open-label, single-arm trial examined the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily in the treatment of AA and its more severe forms over 3 months.12 Of the 66 patients who completed the trial, 64% (42/66) exhibited a positive response to tofacitinib. Relapse was noted in 8.5 weeks after discontinuation of tofacitinib, reiterating the potential need for a maintenance regimen. In this study, 25.8% (17/66) of patients experienced infections as adverse events including (in decreasing order) upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, herpes zoster, conjunctivitis, bronchitis, mononucleosis, and paronychia. No reports of new or recurrent malignancy were noted. Other more constitutional adverse events were noted including headaches, abdominal pain, acne, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, pruritus, hot flashes, cough, folliculitis, weight gain, dry eyes, and amenorrhea. One patient with a pre-existing liver condition experienced transaminitis that resolved with weight loss. There also were noted increases in low- and high-density lipoprotein levels.12 Our patient with baseline thrombocytopenia had mild drops in platelet count that subsequently stabilized and did not result in any bleeding abnormalities.

Duration of Therapy—Tofacitinib has demonstrated some preliminary success in the management of AA, but the appropriate duration of treatment requires further investigation. Our patient has been on tofacitinib for more than 5 years. She started at a total dosage of 10 mg/d, which increased to 16 mg/d. Initial dosing with maintenance regimens needs to be established for further widespread use to maximize benefit and minimize harm.

At what point do we decide to continue or stop treatment in patients who do not respond as expected or plateau? This is another critical question; our patient had periods of slowed growth and plateauing, but knowing the risks and benefits, she continued the medication and eventually experienced improved regrowth again.

Conclusion

Throughout the literature and in our patient, tofacitinib has demonstrated efficacy in treating AA. When other conventional therapies have failed, use of tofacitinib should be considered.

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease that immunopathogenetically is thought to be due to breakdown of the immune privilege of the proximal hair follicle during the anagen growth phase. Alopecia areata has been reported to have a lifetime prevalence of 1.7%.1 Recent studies have specifically identified cytotoxic CD8+ NKG2D+ T cells as being responsible for the activation of AA.2-4 Two interleukins—IL-2 and IL-15—have been implicated to be cytotoxic sensitizers allowing CD8+ T cells to secrete IFN-γ and recognize autoantigens via major histocompatibility complex class I.5,6 Janus kinases (JAKs) are enzymes that play major roles in many different molecular processes. Specifically, JAK1/3 has been determined to arbitrate IL-15 activation of receptors on CD8+ T cells.7 These cells then interact with CD4 T cells, mast cells, and other inflammatory cells to cause destruction of the hair follicle without damage to the keratinocyte and melanocyte stem cells, allowing for reversible yet relapsing hair loss.8

Treatment of AA is difficult, requiring patience and strict compliance while taking into account duration of disease, age at presentation, site involvement, patient expectations, cost and insurance coverage, prior therapies, and any comorbidities. At the time of this case, no US Food and Drug Administration–approved drug regimen existed for the treatment of AA, and, to date, no treatment is preventative.4 We present a case of a patient with alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that was refractory to intralesional triamcinolone, clobetasol, minoxidil, and UVB brush therapy yet was successfully treated with tofacitinib.

Case Report

A 29-year-old otherwise-healthy woman presented to our clinic for treatment of alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that flared intermittently despite various treatments. Her medical history was unremarkable; however, she had a brother with alopecia universalis. She had no family history of any other autoimmune disorders. At the current presentation, the patient was known to have alopecia universalis with scant evidence of exclamation-point hairs on dermoscopy. Her treatment plan at this point consisted of intralesional triamcinolone to the active areas at 10 mg/mL every 4 weeks, plus clobetasol foam 0.05% at bedtime, minoxidil foam 5% at bedtime, and a UVB brush 3 times a week for 6 months before progressing to universalis type because of hair loss in the eyebrows and eyelashes. This treatment plan continued for 1 year with minimal improvement of the alopecia (Figure 1).

The patient was dissatisfied and wanted to discontinue therapy. Because these treatment options were exhausted with minimal benefit, the patient was then considered for treatment with tofacitinib. Baseline studies were performed, including purified protein derivative, complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid profile, and liver function tests, all of which were within reference range. Insurance initially denied coverage of this therapy; a prior authorization was subsequently submitted and denied. A letter of medical necessity was then proposed, and approval for tofacitinib was finally granted. The patient was started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and was monitored every 2 months with a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panels, and liver function tests. She had a platelet count of 112,000/μL (reference range, 150,000–450,000/μL) at baseline, and continued monitoring revealed a platelet count of 83,000 after 7 months of treatment. This platelet abnormality was evaluated by a hematologist and found to be within reference range; subsequent monitoring did not reveal any abnormalities.

Initial hair growth on the scalp was diffuse with thin, white to light brown hairs in areas of hair loss at months 1 and 2, with progressive hair growth over months 3 to 7. Eyebrow hair growth was noted beginning at month 6. One year later, only hair regrowth occurred without any adverse events (Figure 2). After 5 years of treatment, the patient had a full head of thick hair (Figure 3). The tofacitinib dosage was 5 mg twice daily at initiation, and after 1 year increased to 10 mg twice daily. Her medical insurance subsequently changed and the regimen was adjusted to an 11-mg tablet and 5-mg tablet daily. She remained on this regimen with success.

Comment

Use of JAK Inhibitors—Reports and studies have shed light on the use and efficacy of JAK inhibitors in AA (Table).5-11 Tofacitinib is a selective JAK1/3 inhibitor that predominantly inhibits JAK3 but also inhibits JAK1, albeit to a lesser degree, which interferes with the JAK/STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) cascade responsible for the production, differentiation, and function of various B cells, T cells, and natural killer cells.2 Although it was developed for the management of allograft rejection, tofacitinib has made headway in rheumatology for treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis who are unable to take or are not responding to methotrexate.2 Since 2014, tofacitinib has been introduced to the therapeutic realm for AA but is not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.3,4

In 2014, Craiglow and King5 reported use of tofacitinib with dosages beginning at 10 mg/d and increasing to 15 mg/d in a patient with alopecia universalis and psoriasis. Total hair regrowth was noted after 8 months of therapy.5 Xing et al6 described 3 patients treated with ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis, at an oral dose of 20 mg twice daily with near-complete hair regrowth after 5 months of treatment.6 Biopsies from lesions at baseline and after 3 months of therapy revealed a reduction in perifollicular T cells and in HLA class I and II expression in follicles.6 A patient in Italy with essential thrombocythemia and concurrent alopecia universalis was enrolled in a clinical trial with ruxolitinib and was treated with 15 mg twice daily. After 10 months of treatment, the patient had progressive hair regrowth that was sustained for more than 50 months of therapy.7 Baricitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, was used in a 17-year-old adolescent boy to assess efficacy of the drug in

A recent retrospective study assessing response to tofacitinib in adults with AA (>40% hair loss), alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, and stable or progressive diseases for at least 6 months determined a clinical response in 50 of 65 (77%) patients, with 13 patients exhibiting a complete response.10 Patients in this study were started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily with the addition of adjuvant pulsed prednisone (300 mg once monthly for 3 doses) with or without doubled dosing of tofacitinib if they had a halt in hair regrowth. This study demonstrated some benefit when pulsed prednisone was combined with the daily tofacitinib therapy. However, the study emphasized the importance of maintenance therapy, as 8 patients experienced hair loss with discontinuation after previously having hair regrowth; 5 (63%) of these patients experienced regrowth with augmentation of dosing or addition of adjuvant therapy.10

Another group of investigators assessed the efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg in 13 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, most with alopecia universalis (46% [6/13]); 10 of 13 (77%) patients responded to treatment with a mean duration of 6.5 months. The patients who had alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis for more than 10 years were poor responders to tofacitinib, and in fact, 1 of 13 (33%) patients in the study who did not respond to therapy had disease for 12 years.11 Therefore, starting tofacitinib either long-term or intermittently should be considered in children diagnosed early with severe AA, alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis to prevent irreversible hair loss or progressive disease12,13; however, further data are required to assess efficacy and long-term benefits of this type of regimen.

Safety Profile—Widespread use of a medication is determined not only by its efficacy profile but also its safety profile. With any medication that exhibits immunosuppressive effects, adverse events must be considered and thoroughly discussed with patients and their primary care physicians. A prospective, open-label, single-arm trial examined the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily in the treatment of AA and its more severe forms over 3 months.12 Of the 66 patients who completed the trial, 64% (42/66) exhibited a positive response to tofacitinib. Relapse was noted in 8.5 weeks after discontinuation of tofacitinib, reiterating the potential need for a maintenance regimen. In this study, 25.8% (17/66) of patients experienced infections as adverse events including (in decreasing order) upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, herpes zoster, conjunctivitis, bronchitis, mononucleosis, and paronychia. No reports of new or recurrent malignancy were noted. Other more constitutional adverse events were noted including headaches, abdominal pain, acne, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, pruritus, hot flashes, cough, folliculitis, weight gain, dry eyes, and amenorrhea. One patient with a pre-existing liver condition experienced transaminitis that resolved with weight loss. There also were noted increases in low- and high-density lipoprotein levels.12 Our patient with baseline thrombocytopenia had mild drops in platelet count that subsequently stabilized and did not result in any bleeding abnormalities.

Duration of Therapy—Tofacitinib has demonstrated some preliminary success in the management of AA, but the appropriate duration of treatment requires further investigation. Our patient has been on tofacitinib for more than 5 years. She started at a total dosage of 10 mg/d, which increased to 16 mg/d. Initial dosing with maintenance regimens needs to be established for further widespread use to maximize benefit and minimize harm.

At what point do we decide to continue or stop treatment in patients who do not respond as expected or plateau? This is another critical question; our patient had periods of slowed growth and plateauing, but knowing the risks and benefits, she continued the medication and eventually experienced improved regrowth again.

Conclusion

Throughout the literature and in our patient, tofacitinib has demonstrated efficacy in treating AA. When other conventional therapies have failed, use of tofacitinib should be considered.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmstead County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628-633.

- Borazan NH, Furst DE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, nonopioid analgesics, & drugs used in gout. In: Katzung BG, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 13th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2015:618-642.

- Shapiro J. Current treatment of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S42-S44.

- Shapiro J. Dermatologic therapy: alopecia areata update. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:301.

- Craiglow BG, King BA. Killing two birds with one stone: oral tofacitinib reverses alopecia universalis in a patient with plaque psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2988-2990.

- Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med. 2014;20:1043-1049.

- Pieri L, Guglielmelli P, Vannucchi AM. Ruxolitinib-induced reversal of alopecia universalis in a patient with essential thrombocythemia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:82-83.

- Jabbari A, Dai Z, Xing L, et al. Reversal of alopecia areata following treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. EbioMedicine. 2015;2:351-355.

- Jabbari A, Nguyen N, Cerise JE, et al. Treatment of an alopecia areata patient with tofacitinib results in regrowth of hair and changes in serum and skin biomarkers. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:642-643.

- Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: a study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:22-28.

- Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:29-32.

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:E89776.

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Emerging drugs for alopecia areata: JAK inhibitors. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2018;23:77-81.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmstead County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628-633.

- Borazan NH, Furst DE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, nonopioid analgesics, & drugs used in gout. In: Katzung BG, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 13th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2015:618-642.

- Shapiro J. Current treatment of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S42-S44.

- Shapiro J. Dermatologic therapy: alopecia areata update. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:301.

- Craiglow BG, King BA. Killing two birds with one stone: oral tofacitinib reverses alopecia universalis in a patient with plaque psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2988-2990.

- Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med. 2014;20:1043-1049.

- Pieri L, Guglielmelli P, Vannucchi AM. Ruxolitinib-induced reversal of alopecia universalis in a patient with essential thrombocythemia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:82-83.

- Jabbari A, Dai Z, Xing L, et al. Reversal of alopecia areata following treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. EbioMedicine. 2015;2:351-355.

- Jabbari A, Nguyen N, Cerise JE, et al. Treatment of an alopecia areata patient with tofacitinib results in regrowth of hair and changes in serum and skin biomarkers. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:642-643.

- Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: a study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:22-28.

- Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:29-32.

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:E89776.

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Emerging drugs for alopecia areata: JAK inhibitors. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2018;23:77-81.

Practice Points

- Janus kinase inhibitors target one of the cellular pathogeneses of alopecia areata.

- Janus kinase inhibitors may be an option for patients who have exhausted other treatment modalities for alopecia.

Botanical Briefs: Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis)

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) is a member of the family Papaveraceae.1 This North American plant commonly is found in widespread distribution from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Florida and from the Great Lakes to Mississippi.2 Historically, Native Americans used bloodroot as a skin dye and as a medicine for many ailments.3

Bloodroot blooms for only a few days, starting in March, and fruits in June. The flowers comprise 8 to 10 white petals, surrounding a bed of yellow stamens (Figure). The plant thrives in wooded areas and grows to 12 inches tall. In its off-season, the plant remains dormant and can survive below-freezing temperatures.4

Chemical Constituents

Bloodroot gets its colloquial name from its red sap, which is released when the plant’s rhizome is cut. This sap contains a high concentration of alkaloids that are used for protection against predators. The rhizome itself has a rusty, red-brown color; the roots are a brighter red-orange.4

The rhizome of S canadensis contains the highest concentration of active alkaloids; the roots also contain these chemicals, though to a lesser degree; and the leaves, flowers, and fruits harvest approximately 1% of the alkaloids found in the roots.4 The concentration of alkaloids can vary from one plant to the next, depending on environmental conditions.5,6

The major alkaloids in S canadensis include both quaternary benzophenanthridine alkaloids (eg, sanguinarine, chelerythrine, sanguilutine, chelilutine, sanguirubine, chelirubine) and protopin alkaloids (eg, protopine, allocryptopine).3,7 Of these, sanguinarine and chelerythrine typically are the most potent.1 Oral ingestion or topical application of these molecules can have therapeutic and toxic effects.8

Biophysiological Effects

Bloodroot has been shown to have remarkable antimicrobial effects.9 The plant produces hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion.10 These mediators cause oxidative stress, thus inducing destruction of cellular DNA and the cell membrane.11 Although these effects can be helpful when fighting infection, they are not necessarily selective against healthy cells.12

Alkaloids of bloodroot also have cardiovascular therapeutic effects. Sanguinarine blocks angiotensin II and causes vasodilation, thus helping treat hypertension.13 It also acts as an inotrope by blocking the Na+/K+ ATPase pump. These effects in a patient who is already taking digoxin can cause notable cardiotoxicity because the 2 drugs share a mechanism of action.14

Chelerythrine blocks production of cyclooxygenase 2 and prostaglandin E2.15 This pathway modification results in anti-inflammatory effects that can help treat arthritis, edema, and other inflammatory conditions.16 Moreover, sanguinarine has demonstrated efficacy in numerous anticancer pathways,17 including downregulation of intercellular adhesion molecules, vascular cell adhesion molecules, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).18-20 Blocking VEGF is one way to inhibit angiogenesis,21 which is upregulated in tumor formation, thus sanguinarine can have an antiproliferative anticancer effect.22 Sanguinarine also upregulates molecules such as nuclear factor–κB and the protease enzymes known as caspases to cause proapoptotic effects, furthering its antitumor potential.23,24

Treatment of Dermatologic Conditions

The initial technique of Mohs micrographic surgery employed a chemopaste that utilized an extract of S canadensis to preserve tissue.25 Outside the dermatologist’s office, bloodroot is used as a topical home remedy for a variety of cutaneous conditions, including cancer, skin tags, and warts.26 Bloodroot is advertised as black salve, an alternative anticancer treatment.27,28

As useful as this natural agent sounds, it has a pitfall: The alkaloids of S canadensis are nonspecific in their cytotoxicity, damaging neoplastic and healthy tissue.29 This cytotoxic effect can cause escharification through diffuse tissue destruction and has been observed to result in formation of a keloid scar.30 The alkaloids in black salve also have been shown to cause skin erosions and cellular atypia.28,31 Therefore, the utility of this escharotic in medical treatment is limited.32 Fortuitously, oral antibiotics and wound care can help address this adverse effect.28

Bloodroot was once used as a mouth rinse and toothpaste to treat gingivitis, but this application was later associated with oral leukoplakia, a premalignant condition.33 Leukoplakia associated with S canadensis extract often is unremitting. Immediate discontinuation of the offending agent produces little regression, suggesting that cellular damage is irreversible.34

Final Thoughts

Although bloodroot demonstrates efficacy as a phytotherapeutic, it does come with notable toxicity. Physicians should warn patients of the unwanted cosmetic effects of black salve, especially oral products that incorporate sanguinarine. Adverse effects on the oropharynx can be irreversible, though the eschar associated with black salve can be treated with a topical or oral corticosteroid.29

- Vogel M, Lawson M, Sippl W, et al. Structure and mechanism of sanguinarine reductase, an enzyme of alkaloid detoxification. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18397-18406. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.088989

- Maranda EL, Wang MX, Cortizo J, et al. Flower power—the versatility of bloodroot. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:824. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5522

- Setzer WN. The phytochemistry of Cherokee aromatic medicinal plants. Medicines (Basel). 2018;5:121. doi:10.3390/medicines5040121

- Croaker A, King GJ, Pyne JH, et al. Sanguinaria canadensis: traditional medicine, phytochemical composition, biological activities and current uses. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1414. doi:10.3390/ijms17091414

- Graf TN, Levine KE, Andrews ME, et al. Variability in the yield of benzophenanthridine alkaloids in wildcrafted vs cultivated bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2007; 55:1205-1211. doi:10.1021/jf062498f

- Bennett BC, Bell CR, Boulware RT. Geographic variation in alkaloid content of Sanguinaria canadensis (Papaveraceae). Rhodora. 1990;92:57-69.

- Leaver CA, Yuan H, Wallen GR. Apoptotic activities of Sanguinaria canadensis: primary human keratinocytes, C-33A, and human papillomavirus HeLa cervical cancer lines. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2018;17:32-37.

- Kutchan TM. Molecular genetics of plant alkaloid biosynthesis. In: Cordell GA, ed. The Alkaloids. Vol 50. Elsevier Science Publishing Co, Inc; 1997:257-316.

- Obiang-Obounou BW, Kang O-H, Choi J-G, et al. The mechanism of action of sanguinarine against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Toxicol Sci. 2011;36:277-283. doi:10.2131/jts.36.277

- Z˙abka A, Winnicki K, Polit JT, et al. Sanguinarine-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis-like programmed cell death (AL-PCD) in root meristem cells of Allium cepa. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;112:193-206. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.01.004

- Kumar GS, Hazra S. Sanguinarine, a promising anticancer therapeutic: photochemical and nucleic acid binding properties. RSC Advances. 2014;4:56518-56531.

- Ping G, Wang Y, Shen L, et al. Highly efficient complexation of sanguinarine alkaloid by carboxylatopillar[6]arene: pKa shift, increased solubility and enhanced antibacterial activity. Chemical Commun (Camb). 2017;53:7381-7384. doi:10.1039/c7cc02799k

- Caballero-George C, Vanderheyden PM, Solis PN, et al. Biological screening of selected medicinal Panamanian plants by radioligand-binding techniques. Phytomedicine. 2001;8:59-70. doi:10.1078/0944-7113-00011

- Seifen E, Adams RJ, Riemer RK. Sanguinarine: a positive inotropic alkaloid which inhibits cardiac Na+, K+-ATPase. Eur J Pharmacol. 1979;60:373-377. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(79)90245-0

- Debprasad C, Hemanta M, Paromita B, et al. Inhibition of NO2, PGE2, TNF-α, and iNOS EXpression by Shorea robusta L.: an ethnomedicine used for anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012; 2012:254849. doi:10.1155/2012/254849

- Melov S, Ravenscroft J, Malik S, et al. Extension of life-span with superoxide dismutase/catalase mimetics. Science. 2000;289:1567-1569. doi:10.1126/science.289.5484.1567

- Basu P, Kumar GS. Sanguinarine and its role in chronic diseases. In: Gupta SC, Prasad S, Aggarwal BB, eds. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology: Anti-inflammatory Nutraceuticals and Chronic Diseases. Vol 928. Springer International Publishing; 2016:155-172.

- Alasvand M, Assadollahi V, Ambra R, et al. Antiangiogenic effect of alkaloids. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2019;2019:9475908. doi:10.1155/2019/9475908

- Basini G, Santini SE, Bussolati S, et al. The plant alkaloid sanguinarine is a potential inhibitor of follicular angiogenesis. J Reprod Dev. 2007;53:573-579. doi:10.1262/jrd.18126

- Xu J-Y, Meng Q-H, Chong Y, et al. Sanguinarine is a novel VEGF inhibitor involved in the suppression of angiogenesis and cell migration. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1:331-336. doi:10.3892/mco.2012.41

- Lu K, Bhat M, Basu S. Plants and their active compounds: natural molecules to target angiogenesis. Angiogenesis. 2016;19:287-295. doi:10.1007/s10456-016-9512-y

- Achkar IW, Mraiche F, Mohammad RM, et al. Anticancer potential of sanguinarine for various human malignancies. Future Med Chem. 2017;9:933-950. doi:10.4155/fmc-2017-0041

- Lee TK, Park C, Jeong S-J, et al. Sanguinarine induces apoptosis of human oral squamous cell carcinoma KB cells via inactivation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Drug Dev Res. 2016;77:227-240. doi:10.1002/ddr.21315

- Gaziano R, Moroni G, Buè C, et al. Antitumor effects of the benzophenanthridine alkaloid sanguinarine: evidence and perspectives. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:30-39. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v8.i1.30

- Mohs FE. Chemosurgery for skin cancer: fixed tissue and fresh tissue techniques. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:211-215.

- Affleck AG, Varma S. A case of do-it-yourself Mohs’ surgery using bloodroot obtained from the internet. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:1078-1079. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08180.x

- Eastman KL, McFarland LV, Raugi GJ. Buyer beware: a black salve caution. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:E154-E155. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2011.07.031

- Osswald SS, Elston DM, Farley MF, et al. Self-treatment of a basal cell carcinoma with “black and yellow salve.” J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:508-510. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.04.007

- Schlichte MJ, Downing CP, Ramirez-Fort M, et al. Bloodroot associated eschar. Dermatol Online J. 2015;20:13030/qt05r0r2wr.

- Wang MZ, Warshaw EM. Bloodroot. Dermatitis. 2012;23:281-283. doi:10.1097/DER.0b013e318273a4dd

- Tan JM, Peters P, Ong N, et al. Histopathological features after topical black salve application. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:75-76.

- Hou JL, Brewer JD. Black salve and bloodroot extract in dermatologic conditions. Cutis. 2015;95:309-311.

- Eversole LR, Eversole GM, Kopcik J. Sanguinaria-associated oral leukoplakia: comparison with other benign and dysplastic leukoplakic lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2000;89:455-464. doi:10.1016/s1079-2104(00)70125-9

- Mascarenhas AK, Allen CM, Moeschberger ML. The association between Viadent® use and oral leukoplakia—results of a matched case-control study. J Public Health Dent. 2002;62:158-162. doi:10.1111/j.1752-7325.2002.tb03437.x

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) is a member of the family Papaveraceae.1 This North American plant commonly is found in widespread distribution from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Florida and from the Great Lakes to Mississippi.2 Historically, Native Americans used bloodroot as a skin dye and as a medicine for many ailments.3

Bloodroot blooms for only a few days, starting in March, and fruits in June. The flowers comprise 8 to 10 white petals, surrounding a bed of yellow stamens (Figure). The plant thrives in wooded areas and grows to 12 inches tall. In its off-season, the plant remains dormant and can survive below-freezing temperatures.4

Chemical Constituents

Bloodroot gets its colloquial name from its red sap, which is released when the plant’s rhizome is cut. This sap contains a high concentration of alkaloids that are used for protection against predators. The rhizome itself has a rusty, red-brown color; the roots are a brighter red-orange.4

The rhizome of S canadensis contains the highest concentration of active alkaloids; the roots also contain these chemicals, though to a lesser degree; and the leaves, flowers, and fruits harvest approximately 1% of the alkaloids found in the roots.4 The concentration of alkaloids can vary from one plant to the next, depending on environmental conditions.5,6

The major alkaloids in S canadensis include both quaternary benzophenanthridine alkaloids (eg, sanguinarine, chelerythrine, sanguilutine, chelilutine, sanguirubine, chelirubine) and protopin alkaloids (eg, protopine, allocryptopine).3,7 Of these, sanguinarine and chelerythrine typically are the most potent.1 Oral ingestion or topical application of these molecules can have therapeutic and toxic effects.8

Biophysiological Effects

Bloodroot has been shown to have remarkable antimicrobial effects.9 The plant produces hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion.10 These mediators cause oxidative stress, thus inducing destruction of cellular DNA and the cell membrane.11 Although these effects can be helpful when fighting infection, they are not necessarily selective against healthy cells.12

Alkaloids of bloodroot also have cardiovascular therapeutic effects. Sanguinarine blocks angiotensin II and causes vasodilation, thus helping treat hypertension.13 It also acts as an inotrope by blocking the Na+/K+ ATPase pump. These effects in a patient who is already taking digoxin can cause notable cardiotoxicity because the 2 drugs share a mechanism of action.14

Chelerythrine blocks production of cyclooxygenase 2 and prostaglandin E2.15 This pathway modification results in anti-inflammatory effects that can help treat arthritis, edema, and other inflammatory conditions.16 Moreover, sanguinarine has demonstrated efficacy in numerous anticancer pathways,17 including downregulation of intercellular adhesion molecules, vascular cell adhesion molecules, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).18-20 Blocking VEGF is one way to inhibit angiogenesis,21 which is upregulated in tumor formation, thus sanguinarine can have an antiproliferative anticancer effect.22 Sanguinarine also upregulates molecules such as nuclear factor–κB and the protease enzymes known as caspases to cause proapoptotic effects, furthering its antitumor potential.23,24

Treatment of Dermatologic Conditions

The initial technique of Mohs micrographic surgery employed a chemopaste that utilized an extract of S canadensis to preserve tissue.25 Outside the dermatologist’s office, bloodroot is used as a topical home remedy for a variety of cutaneous conditions, including cancer, skin tags, and warts.26 Bloodroot is advertised as black salve, an alternative anticancer treatment.27,28

As useful as this natural agent sounds, it has a pitfall: The alkaloids of S canadensis are nonspecific in their cytotoxicity, damaging neoplastic and healthy tissue.29 This cytotoxic effect can cause escharification through diffuse tissue destruction and has been observed to result in formation of a keloid scar.30 The alkaloids in black salve also have been shown to cause skin erosions and cellular atypia.28,31 Therefore, the utility of this escharotic in medical treatment is limited.32 Fortuitously, oral antibiotics and wound care can help address this adverse effect.28

Bloodroot was once used as a mouth rinse and toothpaste to treat gingivitis, but this application was later associated with oral leukoplakia, a premalignant condition.33 Leukoplakia associated with S canadensis extract often is unremitting. Immediate discontinuation of the offending agent produces little regression, suggesting that cellular damage is irreversible.34

Final Thoughts

Although bloodroot demonstrates efficacy as a phytotherapeutic, it does come with notable toxicity. Physicians should warn patients of the unwanted cosmetic effects of black salve, especially oral products that incorporate sanguinarine. Adverse effects on the oropharynx can be irreversible, though the eschar associated with black salve can be treated with a topical or oral corticosteroid.29

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis) is a member of the family Papaveraceae.1 This North American plant commonly is found in widespread distribution from Nova Scotia, Canada, to Florida and from the Great Lakes to Mississippi.2 Historically, Native Americans used bloodroot as a skin dye and as a medicine for many ailments.3

Bloodroot blooms for only a few days, starting in March, and fruits in June. The flowers comprise 8 to 10 white petals, surrounding a bed of yellow stamens (Figure). The plant thrives in wooded areas and grows to 12 inches tall. In its off-season, the plant remains dormant and can survive below-freezing temperatures.4

Chemical Constituents

Bloodroot gets its colloquial name from its red sap, which is released when the plant’s rhizome is cut. This sap contains a high concentration of alkaloids that are used for protection against predators. The rhizome itself has a rusty, red-brown color; the roots are a brighter red-orange.4

The rhizome of S canadensis contains the highest concentration of active alkaloids; the roots also contain these chemicals, though to a lesser degree; and the leaves, flowers, and fruits harvest approximately 1% of the alkaloids found in the roots.4 The concentration of alkaloids can vary from one plant to the next, depending on environmental conditions.5,6

The major alkaloids in S canadensis include both quaternary benzophenanthridine alkaloids (eg, sanguinarine, chelerythrine, sanguilutine, chelilutine, sanguirubine, chelirubine) and protopin alkaloids (eg, protopine, allocryptopine).3,7 Of these, sanguinarine and chelerythrine typically are the most potent.1 Oral ingestion or topical application of these molecules can have therapeutic and toxic effects.8

Biophysiological Effects

Bloodroot has been shown to have remarkable antimicrobial effects.9 The plant produces hydrogen peroxide and superoxide anion.10 These mediators cause oxidative stress, thus inducing destruction of cellular DNA and the cell membrane.11 Although these effects can be helpful when fighting infection, they are not necessarily selective against healthy cells.12

Alkaloids of bloodroot also have cardiovascular therapeutic effects. Sanguinarine blocks angiotensin II and causes vasodilation, thus helping treat hypertension.13 It also acts as an inotrope by blocking the Na+/K+ ATPase pump. These effects in a patient who is already taking digoxin can cause notable cardiotoxicity because the 2 drugs share a mechanism of action.14

Chelerythrine blocks production of cyclooxygenase 2 and prostaglandin E2.15 This pathway modification results in anti-inflammatory effects that can help treat arthritis, edema, and other inflammatory conditions.16 Moreover, sanguinarine has demonstrated efficacy in numerous anticancer pathways,17 including downregulation of intercellular adhesion molecules, vascular cell adhesion molecules, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF).18-20 Blocking VEGF is one way to inhibit angiogenesis,21 which is upregulated in tumor formation, thus sanguinarine can have an antiproliferative anticancer effect.22 Sanguinarine also upregulates molecules such as nuclear factor–κB and the protease enzymes known as caspases to cause proapoptotic effects, furthering its antitumor potential.23,24

Treatment of Dermatologic Conditions

The initial technique of Mohs micrographic surgery employed a chemopaste that utilized an extract of S canadensis to preserve tissue.25 Outside the dermatologist’s office, bloodroot is used as a topical home remedy for a variety of cutaneous conditions, including cancer, skin tags, and warts.26 Bloodroot is advertised as black salve, an alternative anticancer treatment.27,28

As useful as this natural agent sounds, it has a pitfall: The alkaloids of S canadensis are nonspecific in their cytotoxicity, damaging neoplastic and healthy tissue.29 This cytotoxic effect can cause escharification through diffuse tissue destruction and has been observed to result in formation of a keloid scar.30 The alkaloids in black salve also have been shown to cause skin erosions and cellular atypia.28,31 Therefore, the utility of this escharotic in medical treatment is limited.32 Fortuitously, oral antibiotics and wound care can help address this adverse effect.28

Bloodroot was once used as a mouth rinse and toothpaste to treat gingivitis, but this application was later associated with oral leukoplakia, a premalignant condition.33 Leukoplakia associated with S canadensis extract often is unremitting. Immediate discontinuation of the offending agent produces little regression, suggesting that cellular damage is irreversible.34

Final Thoughts

Although bloodroot demonstrates efficacy as a phytotherapeutic, it does come with notable toxicity. Physicians should warn patients of the unwanted cosmetic effects of black salve, especially oral products that incorporate sanguinarine. Adverse effects on the oropharynx can be irreversible, though the eschar associated with black salve can be treated with a topical or oral corticosteroid.29

- Vogel M, Lawson M, Sippl W, et al. Structure and mechanism of sanguinarine reductase, an enzyme of alkaloid detoxification. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:18397-18406. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.088989

- Maranda EL, Wang MX, Cortizo J, et al. Flower power—the versatility of bloodroot. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:824. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.5522

- Setzer WN. The phytochemistry of Cherokee aromatic medicinal plants. Medicines (Basel). 2018;5:121. doi:10.3390/medicines5040121

- Croaker A, King GJ, Pyne JH, et al. Sanguinaria canadensis: traditional medicine, phytochemical composition, biological activities and current uses. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:1414. doi:10.3390/ijms17091414

- Graf TN, Levine KE, Andrews ME, et al. Variability in the yield of benzophenanthridine alkaloids in wildcrafted vs cultivated bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis L.) J Agric Food Chem. 2007; 55:1205-1211. doi:10.1021/jf062498f

- Bennett BC, Bell CR, Boulware RT. Geographic variation in alkaloid content of Sanguinaria canadensis (Papaveraceae). Rhodora. 1990;92:57-69.

- Leaver CA, Yuan H, Wallen GR. Apoptotic activities of Sanguinaria canadensis: primary human keratinocytes, C-33A, and human papillomavirus HeLa cervical cancer lines. Integr Med (Encinitas). 2018;17:32-37.