User login

Improving Diagnostic Accuracy in Skin of Color Using an Educational Module

Dermatologic disparities disproportionately affect patients with skin of color (SOC). Two studies assessing the diagnostic accuracy of medical students have shown disparities in diagnosing common skin conditions presenting in darker skin compared to lighter skin at early stages of training.1,2 This knowledge gap could be attributed to the underrepresentation of SOC in dermatologic textbooks, journals, and educational curricula.3-6 It is important for dermatologists as well as physicians in other specialties and ancillary health care workers involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases to recognize common skin conditions presenting in SOC. We sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a focused educational module for improving diagnostic accuracy and confidence in treating SOC among interprofessional health care providers.

Methods

Interprofessional health care providers—medical students, residents/fellows, attending physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), and nurses practicing across various medical specialties—at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School and Ascension Medical Group (both in Austin, Texas) were invited to participate in an institutional review board–exempt study involving a virtual SOC educational module from February through May 2021. The 1-hour module involved a pretest, a 15-minute lecture, an immediate posttest, and a 3-month posttest. All tests included the same 40 multiple-choice questions of 20 dermatologic conditions portrayed in lighter and darker skin types from VisualDx.com, and participants were asked to identify the condition in each photograph. Questions appeared one at a time in a randomized order, and answers could not be changed once submitted.

For analysis, the dermatologic conditions were categorized into 4 groups: cancerous, infectious, inflammatory, and SOC-associated conditions. Cancerous conditions included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Infectious conditions included herpes zoster, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and verruca vulgaris. Inflammatory conditions included acne, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, lichen planus, and urticaria. Skin of color–associated conditions included hidradenitis suppurativa, acanthosis nigricans, keloid, and melasma. Two questions utilizing a 5-point Likert scale assessing confidence in diagnosing light and dark skin also were included.

The pre-recorded 15-minute video lecture was given by 2 dermatology residents (P.L.K. and C.P.), and the learning objectives covered morphologic differences in lighter skin and darker skin, comparisons of common dermatologic diseases in lighter skin and darker skin, diseases more commonly affecting patients with SOC, and treatment considerations for conditions affecting skin and hair in patients with SOC. Photographs from the diagnostic accuracy assessment were not reused in the lecture. Detailed explanations on morphology, diagnostic pearls, and treatment options for all conditions tested were provided to participants upon completion of the 3-month posttest.

Statistical Analysis—Test scores were compared between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types and from the pretest to the immediate posttest and 3-month posttest. Multiple linear regression was used to assess for intervention effects on lighter and darker skin scores controlling for provider type and specialty. All tests were 2-sided with significance at P<.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata 17.

Results

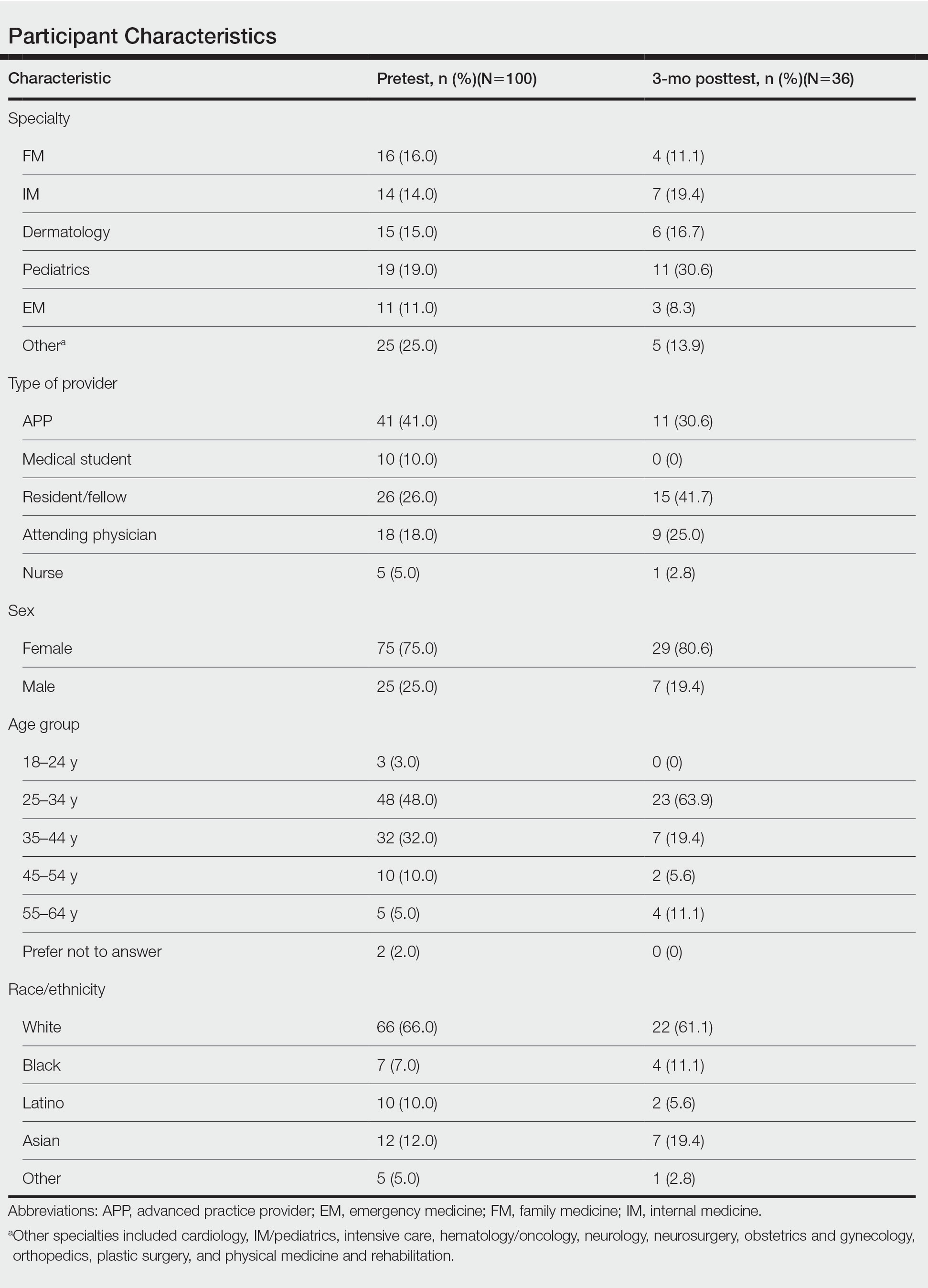

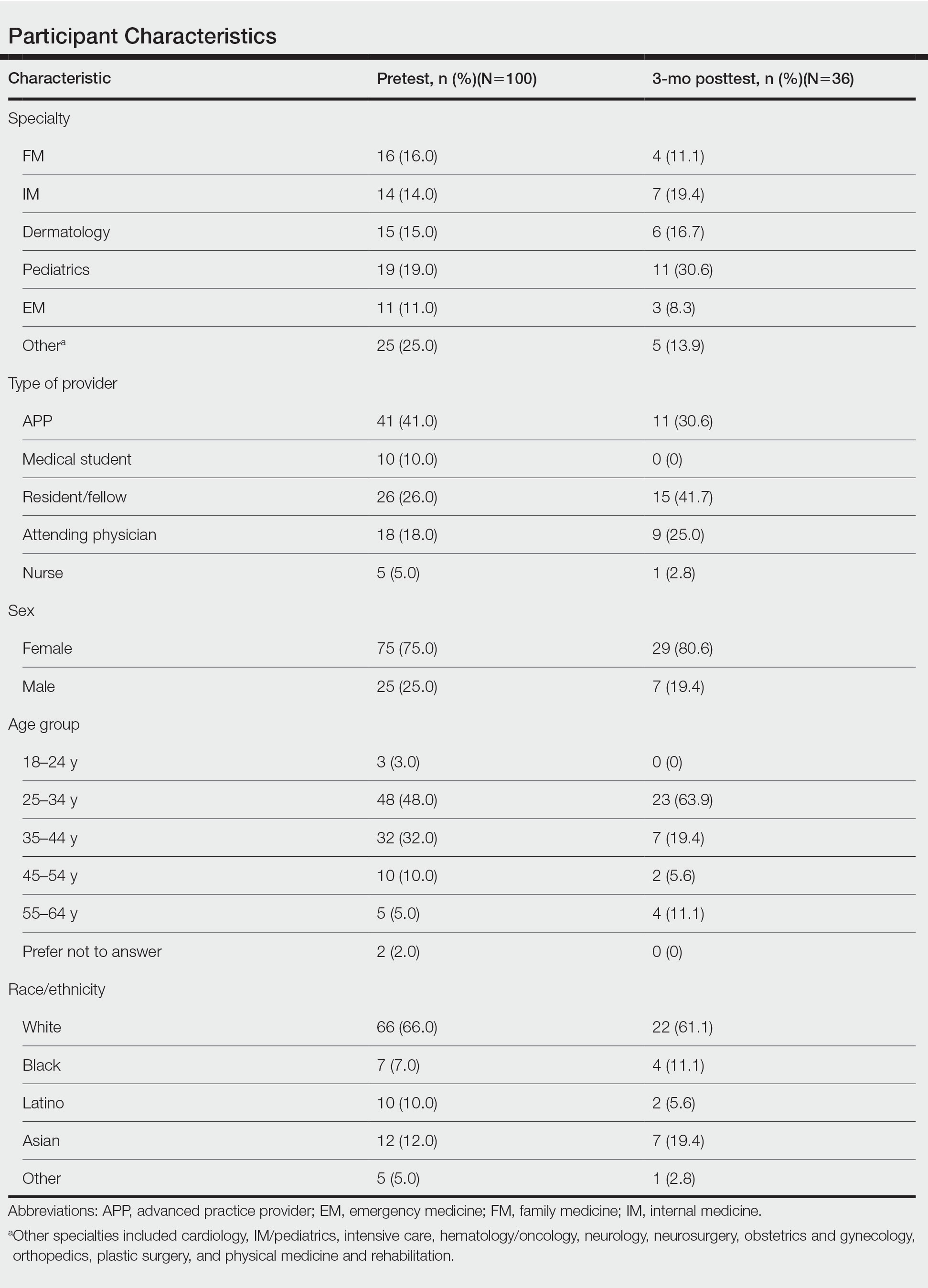

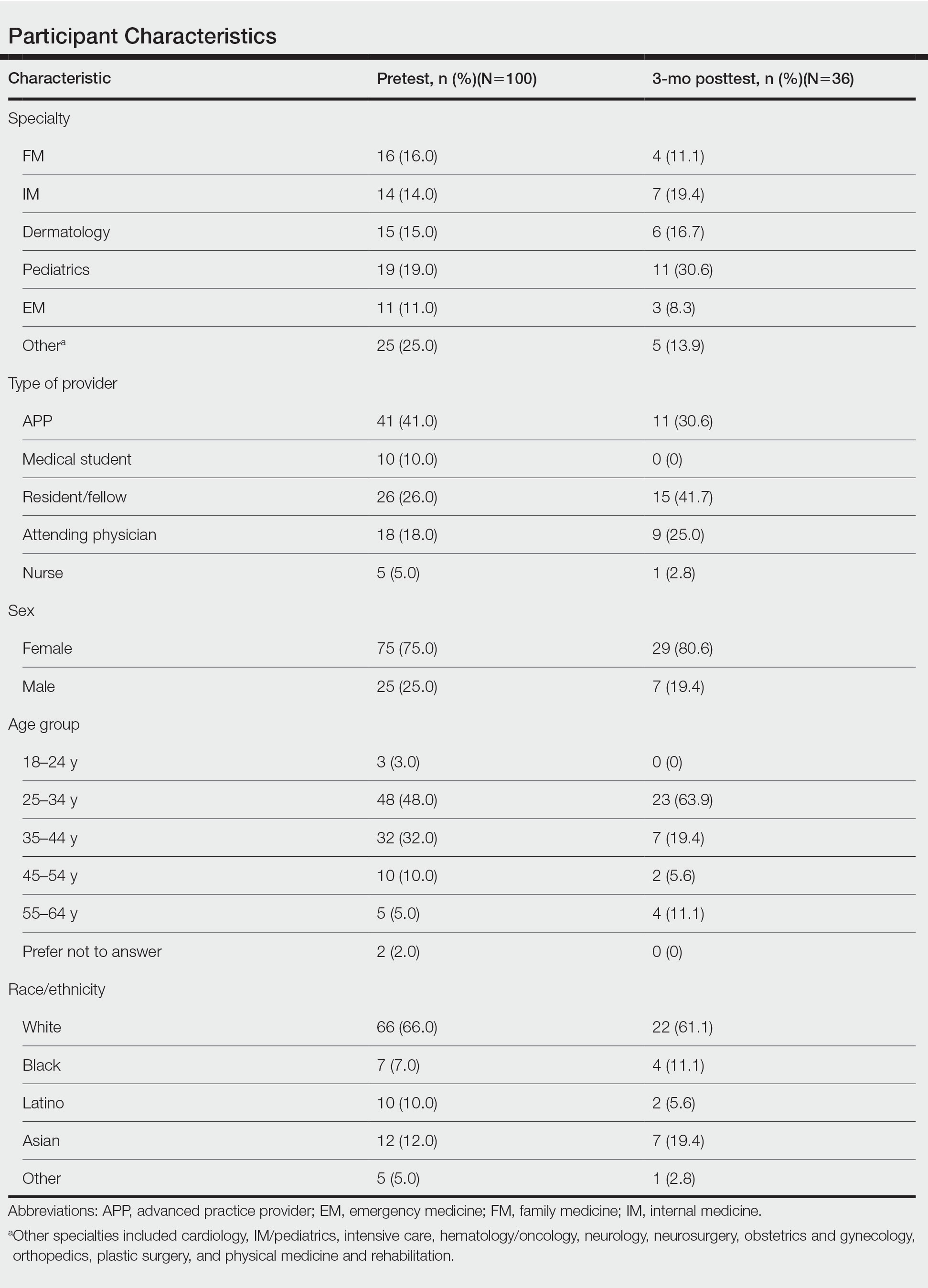

One hundred participants completed the pretest and immediate posttest, 36 of whom also completed the 3-month posttest (Table). There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the pretest and 3-month posttest groups.

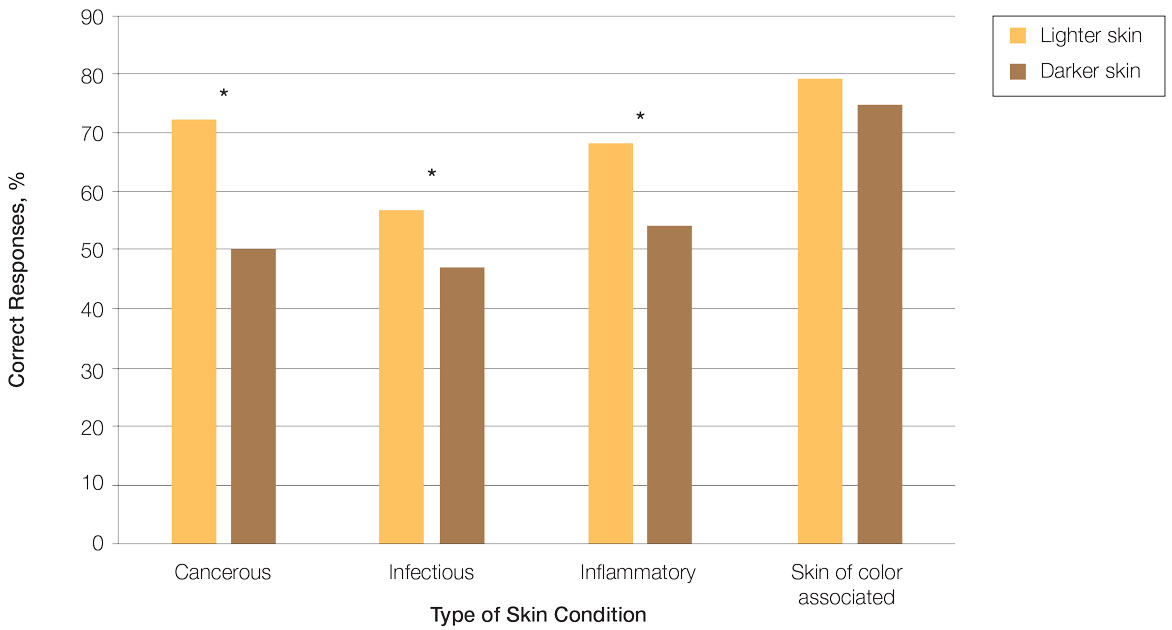

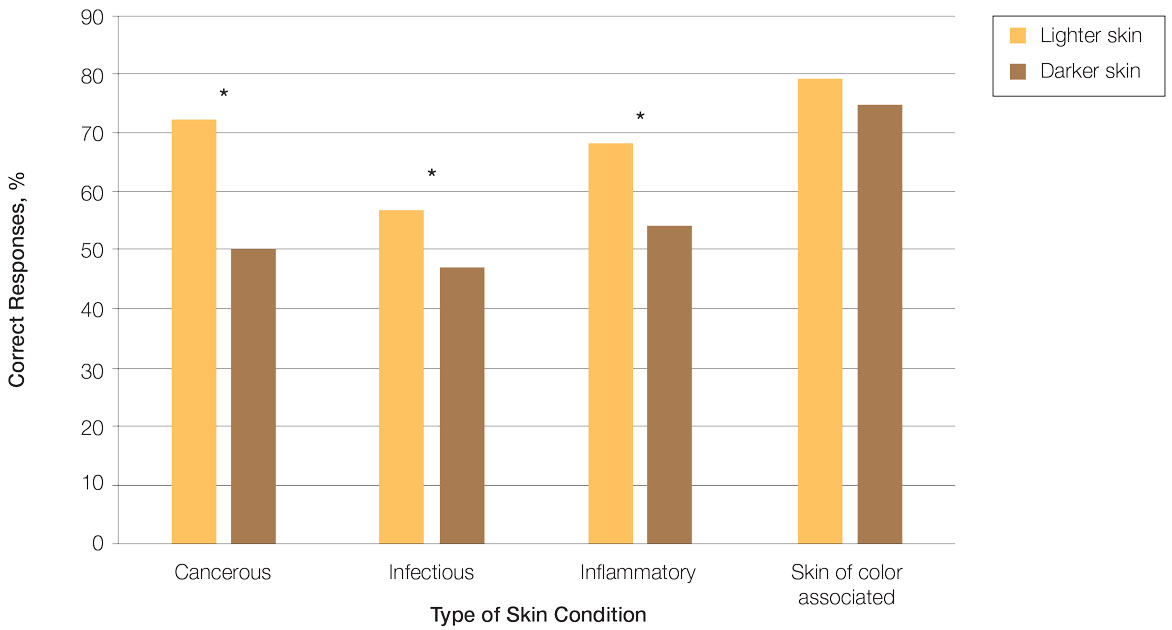

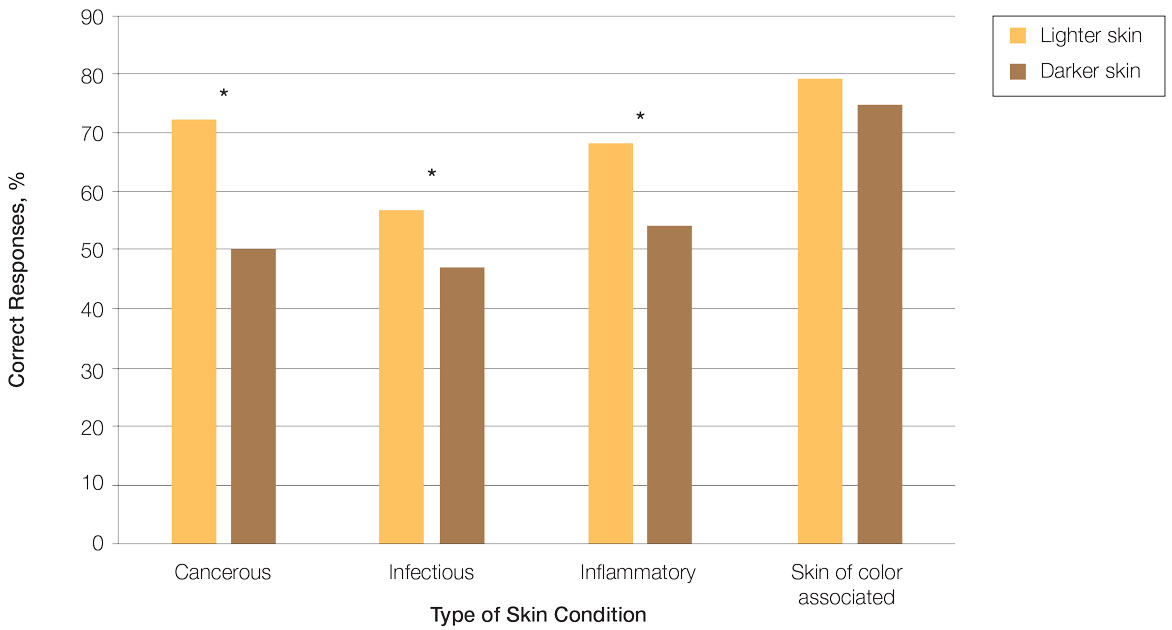

Test scores were correlated with provider type and specialty but not age, sex, or race/ethnicity. Specializing in dermatology and being a resident or attending physician were independently associated with higher test scores. Mean pretest diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores were higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with those shown in darker skin (13.6 vs 11.3 and 2.7 vs 1.9, respectively; both P<.001). Pretest diagnostic accuracy was significantly higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin for cancerous, inflammatory, and infectious conditions (72% vs 50%, 68% vs 55%, and 57% vs 47%, respectively; P<.001 for all)(Figure 1). Skin of color–associated conditions were not associated with significantly different scores for lighter skin compared with darker skin (79% vs 75%; P=.059).

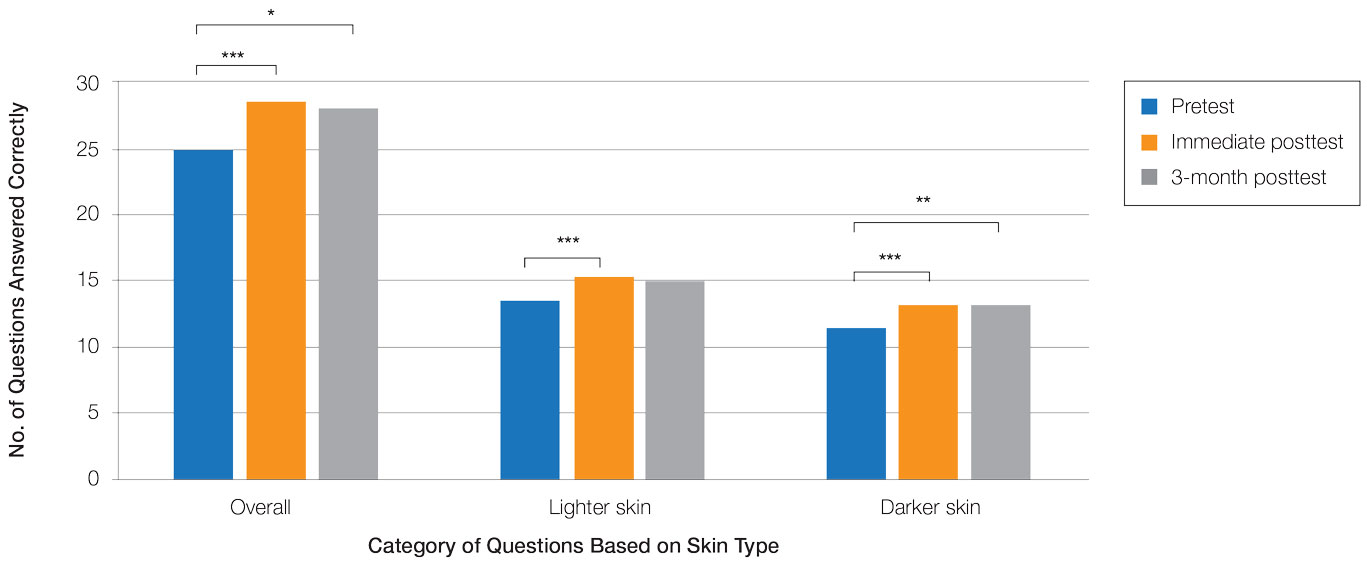

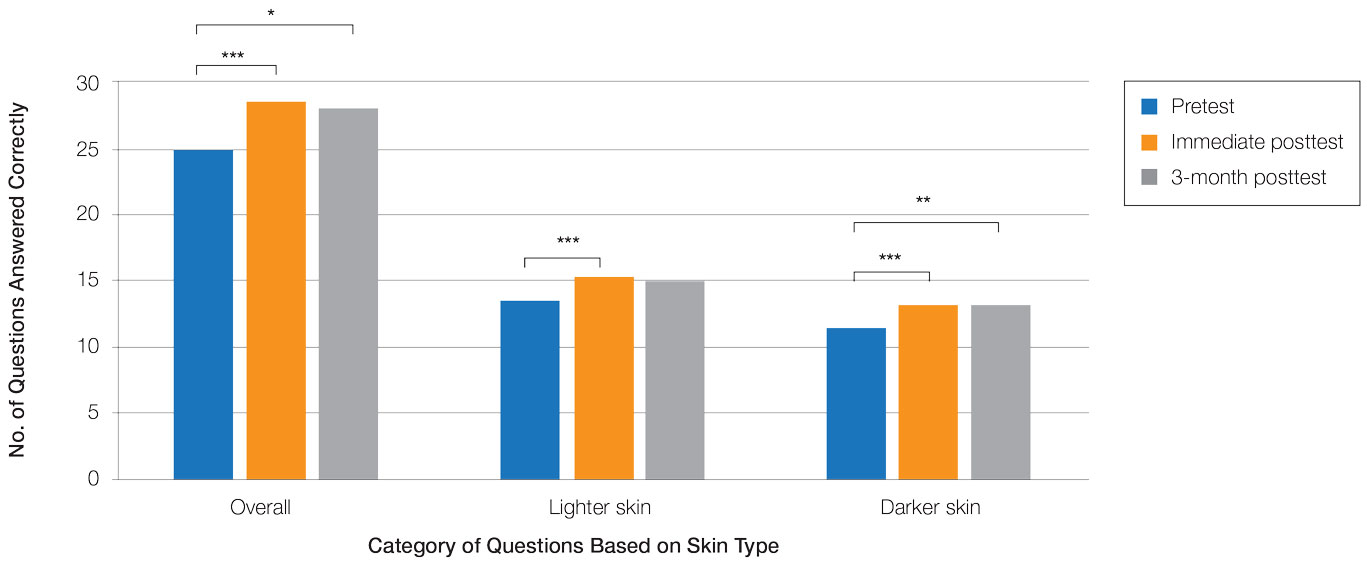

Controlling for provider type and specialty, significantly improved diagnostic accuracy was seen in immediate posttest scores compared with pretest scores for conditions shown in both lighter and darker skin types (lighter: 15.2 vs 13.6; darker: 13.3 vs 11.3; both P<.001)(Figure 2). The immediate posttest demonstrated higher mean diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 15.2 vs 13.3; confidence: 3.0 vs 2.6; both P<.001), but the disparity between scores was less than in the pretest.

Following the 3-month posttest, improvement in diagnostic accuracy was noted among both lighter and darker skin types compared with the pretest, but the difference remained significant only for conditions shown in darker skin (mean scores, 11.3 vs 13.3; P<.01). Similarly, confidence in diagnosing conditions in both lighter and darker skin improved following the immediate posttest (mean scores, 2.7 vs 3.0 and 1.9 vs 2.6; both P<.001), and this improvement remained significant for only darker skin following the 3-month posttest (mean scores, 1.9 vs 2.3; P<.001). Despite these improvements, diagnostic accuracy and confidence remained higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 14.7 vs 13.3; P<.01; confidence: 2.8 vs 2.3; P<.001), though the disparity between scores was again less than in the pretest.

Comment

Our study showed that there are diagnostic disparities between lighter and darker skin types among interprofessional health care providers. Education on SOC should extend to interprofessional health care providers and other medical specialties involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases. A focused educational module may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in SOC. Differences in diagnostic accuracy between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types were noted for the disease categories of infectious, cancerous, and inflammatory conditions, with the exception of conditions more frequently seen in patients with SOC. Learning resources for SOC-associated conditions are more likely to have greater representation of images depicting darker skin types.7 Future educational interventions may need to focus on dermatologic conditions that are not preferentially seen in patients with SOC. In our study, the pretest scores for conditions shown in darker skin were lowest among infectious and cancerous conditions. For infections, certain morphologic clues such as erythema are important for diagnosis but may be more subtle or difficult to discern in darker skin. It also is possible that providers may be less likely to suspect skin cancer in patients with SOC given that the morphologic presentation and/or anatomic site of involvement for skin cancers in SOC differs from those in lighter skin. Future educational interventions targeting disparities in diagnostic accuracy should focus on conditions that are not specifically associated with SOC.

Limitations of our study included the small number of participants, the study population came from a single institution, and a possible selection bias for providers interested in dermatology.

Conclusion

Disparities exist among interprofessional health care providers when treating conditions in patients with lighter skin compared to darker skin. An educational module for health care providers may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in patients with SOC.

- Fenton A, Elliott E, Shahbandi A, et al. Medical students’ ability to diagnose common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:957-958. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.078

- Mamo A, Szeto MD, Rietcheck H, et al. Evaluating medical student assessment of common dermatologic conditions across Fitzpatrick phototypes and skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:167-169. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.868

- Guda VA, Paek SY. Skin of color representation in commonly utilized medical student dermatology resources. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:799. doi:10.36849/JDD.5726

- Wilson BN, Sun M, Ashbaugh AG, et al. Assessment of skin of color and diversity and inclusion content of dermatologic published literature: an analysis and call to action. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:391-397. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.001

- Ibraheim MK, Gupta R, Dao H, et al. Evaluating skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: data from a national survey. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:228-233. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.11.015

- Gupta R, Ibraheim MK, Dao H Jr, et al. Assessing dermatology resident confidence in caring for patients with skin of color. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:873-878. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.08.019

- Chang MJ, Lipner SR. Analysis of skin color on the American Academy of Dermatology public education website. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1236-1237. doi:10.36849/JDD.2020.5545

Dermatologic disparities disproportionately affect patients with skin of color (SOC). Two studies assessing the diagnostic accuracy of medical students have shown disparities in diagnosing common skin conditions presenting in darker skin compared to lighter skin at early stages of training.1,2 This knowledge gap could be attributed to the underrepresentation of SOC in dermatologic textbooks, journals, and educational curricula.3-6 It is important for dermatologists as well as physicians in other specialties and ancillary health care workers involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases to recognize common skin conditions presenting in SOC. We sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a focused educational module for improving diagnostic accuracy and confidence in treating SOC among interprofessional health care providers.

Methods

Interprofessional health care providers—medical students, residents/fellows, attending physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), and nurses practicing across various medical specialties—at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School and Ascension Medical Group (both in Austin, Texas) were invited to participate in an institutional review board–exempt study involving a virtual SOC educational module from February through May 2021. The 1-hour module involved a pretest, a 15-minute lecture, an immediate posttest, and a 3-month posttest. All tests included the same 40 multiple-choice questions of 20 dermatologic conditions portrayed in lighter and darker skin types from VisualDx.com, and participants were asked to identify the condition in each photograph. Questions appeared one at a time in a randomized order, and answers could not be changed once submitted.

For analysis, the dermatologic conditions were categorized into 4 groups: cancerous, infectious, inflammatory, and SOC-associated conditions. Cancerous conditions included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Infectious conditions included herpes zoster, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and verruca vulgaris. Inflammatory conditions included acne, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, lichen planus, and urticaria. Skin of color–associated conditions included hidradenitis suppurativa, acanthosis nigricans, keloid, and melasma. Two questions utilizing a 5-point Likert scale assessing confidence in diagnosing light and dark skin also were included.

The pre-recorded 15-minute video lecture was given by 2 dermatology residents (P.L.K. and C.P.), and the learning objectives covered morphologic differences in lighter skin and darker skin, comparisons of common dermatologic diseases in lighter skin and darker skin, diseases more commonly affecting patients with SOC, and treatment considerations for conditions affecting skin and hair in patients with SOC. Photographs from the diagnostic accuracy assessment were not reused in the lecture. Detailed explanations on morphology, diagnostic pearls, and treatment options for all conditions tested were provided to participants upon completion of the 3-month posttest.

Statistical Analysis—Test scores were compared between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types and from the pretest to the immediate posttest and 3-month posttest. Multiple linear regression was used to assess for intervention effects on lighter and darker skin scores controlling for provider type and specialty. All tests were 2-sided with significance at P<.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata 17.

Results

One hundred participants completed the pretest and immediate posttest, 36 of whom also completed the 3-month posttest (Table). There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the pretest and 3-month posttest groups.

Test scores were correlated with provider type and specialty but not age, sex, or race/ethnicity. Specializing in dermatology and being a resident or attending physician were independently associated with higher test scores. Mean pretest diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores were higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with those shown in darker skin (13.6 vs 11.3 and 2.7 vs 1.9, respectively; both P<.001). Pretest diagnostic accuracy was significantly higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin for cancerous, inflammatory, and infectious conditions (72% vs 50%, 68% vs 55%, and 57% vs 47%, respectively; P<.001 for all)(Figure 1). Skin of color–associated conditions were not associated with significantly different scores for lighter skin compared with darker skin (79% vs 75%; P=.059).

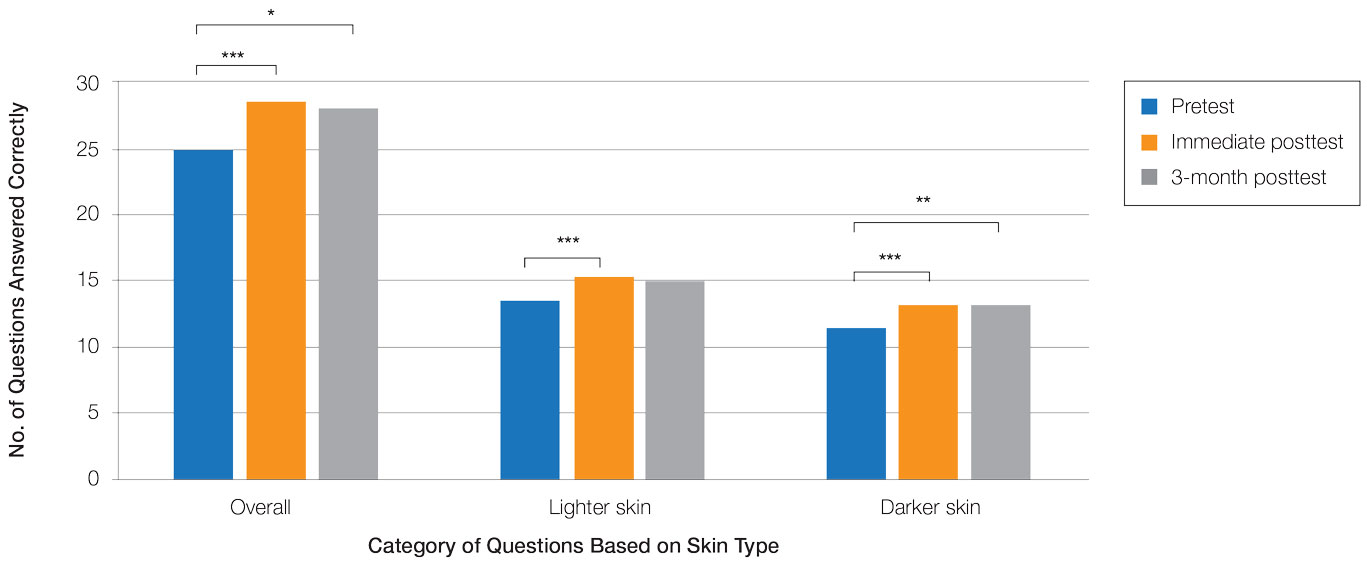

Controlling for provider type and specialty, significantly improved diagnostic accuracy was seen in immediate posttest scores compared with pretest scores for conditions shown in both lighter and darker skin types (lighter: 15.2 vs 13.6; darker: 13.3 vs 11.3; both P<.001)(Figure 2). The immediate posttest demonstrated higher mean diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 15.2 vs 13.3; confidence: 3.0 vs 2.6; both P<.001), but the disparity between scores was less than in the pretest.

Following the 3-month posttest, improvement in diagnostic accuracy was noted among both lighter and darker skin types compared with the pretest, but the difference remained significant only for conditions shown in darker skin (mean scores, 11.3 vs 13.3; P<.01). Similarly, confidence in diagnosing conditions in both lighter and darker skin improved following the immediate posttest (mean scores, 2.7 vs 3.0 and 1.9 vs 2.6; both P<.001), and this improvement remained significant for only darker skin following the 3-month posttest (mean scores, 1.9 vs 2.3; P<.001). Despite these improvements, diagnostic accuracy and confidence remained higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 14.7 vs 13.3; P<.01; confidence: 2.8 vs 2.3; P<.001), though the disparity between scores was again less than in the pretest.

Comment

Our study showed that there are diagnostic disparities between lighter and darker skin types among interprofessional health care providers. Education on SOC should extend to interprofessional health care providers and other medical specialties involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases. A focused educational module may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in SOC. Differences in diagnostic accuracy between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types were noted for the disease categories of infectious, cancerous, and inflammatory conditions, with the exception of conditions more frequently seen in patients with SOC. Learning resources for SOC-associated conditions are more likely to have greater representation of images depicting darker skin types.7 Future educational interventions may need to focus on dermatologic conditions that are not preferentially seen in patients with SOC. In our study, the pretest scores for conditions shown in darker skin were lowest among infectious and cancerous conditions. For infections, certain morphologic clues such as erythema are important for diagnosis but may be more subtle or difficult to discern in darker skin. It also is possible that providers may be less likely to suspect skin cancer in patients with SOC given that the morphologic presentation and/or anatomic site of involvement for skin cancers in SOC differs from those in lighter skin. Future educational interventions targeting disparities in diagnostic accuracy should focus on conditions that are not specifically associated with SOC.

Limitations of our study included the small number of participants, the study population came from a single institution, and a possible selection bias for providers interested in dermatology.

Conclusion

Disparities exist among interprofessional health care providers when treating conditions in patients with lighter skin compared to darker skin. An educational module for health care providers may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in patients with SOC.

Dermatologic disparities disproportionately affect patients with skin of color (SOC). Two studies assessing the diagnostic accuracy of medical students have shown disparities in diagnosing common skin conditions presenting in darker skin compared to lighter skin at early stages of training.1,2 This knowledge gap could be attributed to the underrepresentation of SOC in dermatologic textbooks, journals, and educational curricula.3-6 It is important for dermatologists as well as physicians in other specialties and ancillary health care workers involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases to recognize common skin conditions presenting in SOC. We sought to evaluate the effectiveness of a focused educational module for improving diagnostic accuracy and confidence in treating SOC among interprofessional health care providers.

Methods

Interprofessional health care providers—medical students, residents/fellows, attending physicians, advanced practice providers (APPs), and nurses practicing across various medical specialties—at The University of Texas at Austin Dell Medical School and Ascension Medical Group (both in Austin, Texas) were invited to participate in an institutional review board–exempt study involving a virtual SOC educational module from February through May 2021. The 1-hour module involved a pretest, a 15-minute lecture, an immediate posttest, and a 3-month posttest. All tests included the same 40 multiple-choice questions of 20 dermatologic conditions portrayed in lighter and darker skin types from VisualDx.com, and participants were asked to identify the condition in each photograph. Questions appeared one at a time in a randomized order, and answers could not be changed once submitted.

For analysis, the dermatologic conditions were categorized into 4 groups: cancerous, infectious, inflammatory, and SOC-associated conditions. Cancerous conditions included basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Infectious conditions included herpes zoster, tinea corporis, tinea versicolor, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, and verruca vulgaris. Inflammatory conditions included acne, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, lichen planus, and urticaria. Skin of color–associated conditions included hidradenitis suppurativa, acanthosis nigricans, keloid, and melasma. Two questions utilizing a 5-point Likert scale assessing confidence in diagnosing light and dark skin also were included.

The pre-recorded 15-minute video lecture was given by 2 dermatology residents (P.L.K. and C.P.), and the learning objectives covered morphologic differences in lighter skin and darker skin, comparisons of common dermatologic diseases in lighter skin and darker skin, diseases more commonly affecting patients with SOC, and treatment considerations for conditions affecting skin and hair in patients with SOC. Photographs from the diagnostic accuracy assessment were not reused in the lecture. Detailed explanations on morphology, diagnostic pearls, and treatment options for all conditions tested were provided to participants upon completion of the 3-month posttest.

Statistical Analysis—Test scores were compared between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types and from the pretest to the immediate posttest and 3-month posttest. Multiple linear regression was used to assess for intervention effects on lighter and darker skin scores controlling for provider type and specialty. All tests were 2-sided with significance at P<.05. Analyses were conducted using Stata 17.

Results

One hundred participants completed the pretest and immediate posttest, 36 of whom also completed the 3-month posttest (Table). There was no significant difference in baseline characteristics between the pretest and 3-month posttest groups.

Test scores were correlated with provider type and specialty but not age, sex, or race/ethnicity. Specializing in dermatology and being a resident or attending physician were independently associated with higher test scores. Mean pretest diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores were higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with those shown in darker skin (13.6 vs 11.3 and 2.7 vs 1.9, respectively; both P<.001). Pretest diagnostic accuracy was significantly higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin for cancerous, inflammatory, and infectious conditions (72% vs 50%, 68% vs 55%, and 57% vs 47%, respectively; P<.001 for all)(Figure 1). Skin of color–associated conditions were not associated with significantly different scores for lighter skin compared with darker skin (79% vs 75%; P=.059).

Controlling for provider type and specialty, significantly improved diagnostic accuracy was seen in immediate posttest scores compared with pretest scores for conditions shown in both lighter and darker skin types (lighter: 15.2 vs 13.6; darker: 13.3 vs 11.3; both P<.001)(Figure 2). The immediate posttest demonstrated higher mean diagnostic accuracy and confidence scores for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 15.2 vs 13.3; confidence: 3.0 vs 2.6; both P<.001), but the disparity between scores was less than in the pretest.

Following the 3-month posttest, improvement in diagnostic accuracy was noted among both lighter and darker skin types compared with the pretest, but the difference remained significant only for conditions shown in darker skin (mean scores, 11.3 vs 13.3; P<.01). Similarly, confidence in diagnosing conditions in both lighter and darker skin improved following the immediate posttest (mean scores, 2.7 vs 3.0 and 1.9 vs 2.6; both P<.001), and this improvement remained significant for only darker skin following the 3-month posttest (mean scores, 1.9 vs 2.3; P<.001). Despite these improvements, diagnostic accuracy and confidence remained higher for skin conditions shown in lighter skin compared with darker skin (diagnostic accuracy: 14.7 vs 13.3; P<.01; confidence: 2.8 vs 2.3; P<.001), though the disparity between scores was again less than in the pretest.

Comment

Our study showed that there are diagnostic disparities between lighter and darker skin types among interprofessional health care providers. Education on SOC should extend to interprofessional health care providers and other medical specialties involved in treating or triaging dermatologic diseases. A focused educational module may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in SOC. Differences in diagnostic accuracy between conditions shown in lighter and darker skin types were noted for the disease categories of infectious, cancerous, and inflammatory conditions, with the exception of conditions more frequently seen in patients with SOC. Learning resources for SOC-associated conditions are more likely to have greater representation of images depicting darker skin types.7 Future educational interventions may need to focus on dermatologic conditions that are not preferentially seen in patients with SOC. In our study, the pretest scores for conditions shown in darker skin were lowest among infectious and cancerous conditions. For infections, certain morphologic clues such as erythema are important for diagnosis but may be more subtle or difficult to discern in darker skin. It also is possible that providers may be less likely to suspect skin cancer in patients with SOC given that the morphologic presentation and/or anatomic site of involvement for skin cancers in SOC differs from those in lighter skin. Future educational interventions targeting disparities in diagnostic accuracy should focus on conditions that are not specifically associated with SOC.

Limitations of our study included the small number of participants, the study population came from a single institution, and a possible selection bias for providers interested in dermatology.

Conclusion

Disparities exist among interprofessional health care providers when treating conditions in patients with lighter skin compared to darker skin. An educational module for health care providers may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in patients with SOC.

- Fenton A, Elliott E, Shahbandi A, et al. Medical students’ ability to diagnose common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:957-958. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.078

- Mamo A, Szeto MD, Rietcheck H, et al. Evaluating medical student assessment of common dermatologic conditions across Fitzpatrick phototypes and skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:167-169. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.868

- Guda VA, Paek SY. Skin of color representation in commonly utilized medical student dermatology resources. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:799. doi:10.36849/JDD.5726

- Wilson BN, Sun M, Ashbaugh AG, et al. Assessment of skin of color and diversity and inclusion content of dermatologic published literature: an analysis and call to action. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:391-397. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.001

- Ibraheim MK, Gupta R, Dao H, et al. Evaluating skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: data from a national survey. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:228-233. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.11.015

- Gupta R, Ibraheim MK, Dao H Jr, et al. Assessing dermatology resident confidence in caring for patients with skin of color. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:873-878. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.08.019

- Chang MJ, Lipner SR. Analysis of skin color on the American Academy of Dermatology public education website. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1236-1237. doi:10.36849/JDD.2020.5545

- Fenton A, Elliott E, Shahbandi A, et al. Medical students’ ability to diagnose common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:957-958. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.078

- Mamo A, Szeto MD, Rietcheck H, et al. Evaluating medical student assessment of common dermatologic conditions across Fitzpatrick phototypes and skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;87:167-169. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.06.868

- Guda VA, Paek SY. Skin of color representation in commonly utilized medical student dermatology resources. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:799. doi:10.36849/JDD.5726

- Wilson BN, Sun M, Ashbaugh AG, et al. Assessment of skin of color and diversity and inclusion content of dermatologic published literature: an analysis and call to action. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2021;7:391-397. doi:10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.04.001

- Ibraheim MK, Gupta R, Dao H, et al. Evaluating skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: data from a national survey. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:228-233. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.11.015

- Gupta R, Ibraheim MK, Dao H Jr, et al. Assessing dermatology resident confidence in caring for patients with skin of color. Clin Dermatol. 2021;39:873-878. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2021.08.019

- Chang MJ, Lipner SR. Analysis of skin color on the American Academy of Dermatology public education website. J Drugs Dermatol. 2020;19:1236-1237. doi:10.36849/JDD.2020.5545

Practice Points

- Disparities exist among interprofessional health care providers when diagnosing conditions in patients with lighter and darker skin, specifically for infectious, cancerous, or inflammatory conditions vs conditions that are preferentially seen in patients with skin of color (SOC).

- A focused educational module for health care providers may provide long-term improvements in diagnostic accuracy and confidence for conditions presenting in patients with SOC.

Elbow nodules

A 42-year-old woman came to our clinic to have lumps on her right elbow removed. She said the lumps did not bother her, but on further questioning, admitted that her fingers turned white when they were exposed to the cold. She had frequent heartburn, but denied fatigue, weight loss, dysphagia, diarrhea, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, muscle weakness, or digital pain.

On physical exam, there were multiple small, firm subcutaneous nodules—some with a white surface protruding through the skin of her right elbow (FIGURE 1A). The nodules were slightly tender to palpation. On further examination we noted tight, smooth skin on her fingers (FIGURE 1B). Her right thumb was fixed in an extended position (FIGURE 2). There were also small blood vessels on her hands and pitted scars on her fingertips.

FIGURE 1

Elbow nodules and clubbing of the fingers

The 42-year-old patient sought care at the clinic to have slightly tender nodules removed from her right elbow. The patient also had tight skin and clubbing of the fingers.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 2

Thumb fixed in an extended position

The patient had tight skin on her fingers and a pitted scar on her thumb, which was fixed in an extended position.

Diagnosis: CREST syndrome

Our patient had CREST syndrome, a variant of limited systemic scleroderma. CREST syndrome is characterized by Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias.

Systemic scleroderma is a chronic auto-immune disease involving sclerotic, vascular, and inflammatory changes of the skin and internal organs. There are 19 new cases per million adults per year, with an estimated annual prevalence of 276 cases per million adults in the United States.1 Scleroderma occurs in women 4.6 times more often than in men; the mean age at diagnosis is 45 years.1 Although the pathogenesis of scleroderma remains unclear, interactions among leukocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts are likely to be central in this disease.2

According to the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines,3 a diagnosis of systemic scleroderma can be made with either 1 major criterion or 2 minor criteria present. The major criterion is symmetric thickening, tightening, and induration of the skin proximal to the metatarsal-phalangeal or metacarpal-phalangeal joints. This may affect the whole extremity, trunk, neck, and face. The minor criteria include sclerodactyly, digital pitting scars or a loss of substance from the finger pads, and bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis.

Two forms of scleroderma. To improve sensitivity for milder forms of disease, the condition is often divided into diffuse systemic scleroderma (dSSc) or limited systemic scleroderma (lSSc) (TABLE 1), with CREST syndrome being a variant of the limited form.4 Patients with dSSc usually have a rapid diffuse involvement of the trunk, hands, feet, and face with early internal organ involvement. Patients with lSSc, however, usually have slow skin involvement limited to hands, feet, and face, and delayed systemic involvement, if any.

If CREST syndrome is suspected, it is important to look for its cardinal features. Cutaneous calcinosis usually presents over the bony prominences of knees, elbows, spine, and iliac crests, and may be painful. Patients may complain of Raynaud’s phenomenon with triphasic color changes, ie, pallor, cyanosis, and rubor, occurring months to years before sclerosis. Ulcerations at fingertips from Raynaud’s may be evident as pitted scars on physical exam. There is also a nonpitting edema of hands and feet that later progresses into sclerodactyly with tapering of fingers (our patient actually had clubbing). Patients may complain of stiffness of the hands and feet as the sclerosis progresses.

As a result of the edema and fibrosis of the face, patients may lose facial lines and comment that they look younger. Often, they will indicate that they have noticed the appearance of small blood vessels on their face, mouth, or hands. Patients may also complain of gastrointestinal problems such as esophageal reflux, diarrhea, or dysphagia.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of systemic scleroderma4-6

| Diffuse systemic scleroderma | Limited systemic scleroderma (Includes CREST syndrome) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Fatigue and weight loss or gain | None |

| Vascular | Mild to moderate Raynaud’s phenomenon | Moderate to severe Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Cutaneous | Sclerosis to trunk, arms, and face; rapid progression | Sclerosis to hands or toes and face; slow progression; calcinosis is prominent |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgias and deformities, muscle weakness, and tendon friction rubs | Arthralgias |

| Gastrointestinal | GERD, esophageal dysmotility, and malabsorption are common; all may be severe | Mild to moderate GERD and esophageal dysmotility are common; malabsorption is less common |

| Renal | Severe hypertension, and renal infarcts in renal crisis are common | Rare |

| Pulmonary | Pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease are common | Uncommon |

| Cardiac | Cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias are common | Uncommon |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | ||

Differential includes morphea and scleromyxedema

A thorough history, physical exam, lab work, and possibly biopsy will help differentiate systemic scleroderma from the possible diagnoses with sclerosis listed below:

- Morphea features a localized, patchy distribution of skin fibrosis. There is no systemic involvement or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

- Mixed connective tissue disease has features of other autoimmune diseases, along with those of scleroderma.

- Eosinophilic fasciitis involves the fascia and muscle on biopsy. There is sparing of the hands.

- Scleromyxedema represents the skin thickening seen in patients with a gammopathy. Raynaud’s phenomenon may also be present.

- Scleredema is associated with diabetes. Skin changes are found mostly on the neck, shoulders, and upper arms. On rare occasions, there is visceral involvement. Raynaud’s phenomenon is not present.

In addition, the differential includes chronic graft-vs-host disease; lichen sclerosis et atrophicus; amyloidosis; porphyria cutanea et tardia; primary Raynaud’s phenomenon; and polyvinyl chloride, bleomycin, or pentazocyine exposure.

Nailfold capillary abnormalities help with the diagnosis

As noted earlier, diagnosing systemic scleroderma hinges on taking a good history, doing a thorough physical exam, applying the ACR diagnostic criteria, and ordering lab work. The sensitivity of the ACR criteria increases from 67% to 99% with the addition of nailfold capillary abnormalities (telangiectasias), identified using a dermatoscope.5

The initial lab work that you should consider includes an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test, complete blood count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. If the ANA is positive, anticentromere antibody (ACA) and DNA topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody tests should be ordered to see if scleroderma is likely limited or diffuse. ACA will be present in 21% of dSSc and 71% of lSSc cases, whereas Scl-70 will be present in 33% of dSSc and 18% of lSSc cases.6

If the diagnosis is still unclear, do a punch biopsy. Histology in the early phase will show mild cellular infiltrates around dermal blood vessels and at the dermal subcutaneous inter-phase, while the later phase will show thickening of dermis with broadening of collagen fibers and hyalinization of blood vessel walls.6 If lung, kidney, heart, or gastrointestinal involvement is suspected based on symptoms or physical exam, you’ll need to do an organ function work-up.

Treatment focuses on organ-specific problems

Currently, there are no guidelines for the treatment of scleroderma, given that the exact pathogenesis remains unclear and the disease course varies from patient to patient. Pharmacologic therapy is focused on symptoms and organ-specific problems (TABLE 2). Prazosin 1 to 3 mg TID is moderately effective in treating Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to scleroderma7 (SOR: A). Losartan has been reported to reduce the frequency and severity of Raynaud’s phenomenon compared with a low dose of nifedepine,8 in a nonblinded randomized controlled trial (SOR: B). For interstitial lung disease, cyclophosphamide has been found to modestly reduce dyspnea while improving lung function, but it requires close monitoring9 (SOR: A). Bosentan is approved for symptomatic pulmonary hypertension and has been shown to decrease the occurrence of digital ulcers secondary to Raynaud’s phenomenon10 (SOR: A). (Bosentan is available in the United States under a special restricted distribution program called the Tracleer Access Program.)

Nonpharmacologic treatments should also be considered in the management of scleroderma. Advise patients that Raynaud’s phenomenon may be improved by avoiding exposure to the cold and by not smoking (SOR: C). Cutaneous ulcers can be protected with an occlusive dressing and treated with antibiotics if infected (SOR: C). To remove painful calcinotic nodules or release contractures secondary to sclerosis that may limit movement, you may want to consider surgery for your patient11 (SOR: C). If aesthetically unappealing, telangiectasias may be removed with electrosurgery or laser therapy (SOR: C).

Prognosis for scleroderma varies, depending on whether it is diffuse or limited. One large study found that patients with lSSc had a 10-year survival rate of 71%, compared with 21% for patients with dSSc (SOR: B).4 Patients with systemic sclerosis should be monitored for interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, and cardiomyopathy (SOR: C). Prognosis worsens with renal, pulmonary, or cardiac involvement; pulmonary disease is the leading cause of death in dSSc.1

TABLE 2

Medical treatment of systemic scleroderma5-9

| Organ-specific problem/symptom | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Nifedipine, verapamil, losartan, iloprost, prazosin, bosentan* |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Bosentan,* iloprost, captopril, enalapril, sildenafil |

| Interstitial lung disease | Cyclophosphamide, prednisone |

| Cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias | Antiarrhythmics, diuretics, digoxin, pacemaker, transplant |

| Renal failure or crisis | Captopril, kidney dialysis, transplant |

| Skin fibrosis | Methotrexate, cyclosporine, D-penicillamine |

| Arthralgias | Ibuprofen, acetaminophen |

| GERD, gastroparesis, diarrhea | H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics, antibiotics |

| Pruritus | Antihistamines, low-dose topical steroids |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | |

| *Restricted access in the United States. | |

Our patient has a change of heart

Our patient had all the cardinal features of CREST syndrome on history and physical exam. She had an ANA of 1:640 with speckled pattern and ACA and Scl-70 were negative, demonstrating that diagnosis must be made in clinical context and not just based on lab markers. We treated her GERD with lifestyle changes and a proton pump inhibitor. We explained the risks and benefits of cutting out her calcinosis nodules and she chose not to have surgery.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Diaz, MD, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, Mail #7816, San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected]

1. Mayes MD, Lacey JV, Jr, Beebe-Deemer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2246-2255.

2. Hasegawa M, Sato S. The roles of chemokines in leukocyte recruitment in systemic sclerosis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3637-3647.

3. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581-590.

4. Barnett AJ, Miller MH, Littlejohn GO. A survival study of patients with scleroderma diagnosed over 30 years (1953-1983): the value of a simple cutaneous classification in the early stages of disease. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:276-283.

5. Hudson M, Taillerfer S, Steele R, et al. Improving sensitivity of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:754-757.

6. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

7. Harding SE, Tingey PC, Pope J, et al. Prazosin for Raynaud’s phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998;(2):CD000956.-

8. Dziadzio M, Denton CP, Smith R, et al. Losartan therapy for Raynaud’s phenomenon and scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2646-2655.

9. Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements P, et al. For the Scleroderma Lung Study Research Group. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655-2666.

10. Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelial receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3884-3995.

11. Melone CP, Jr, McLoughlin JC, Beldner S. Surgical management of the hand in scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:514-520.

A 42-year-old woman came to our clinic to have lumps on her right elbow removed. She said the lumps did not bother her, but on further questioning, admitted that her fingers turned white when they were exposed to the cold. She had frequent heartburn, but denied fatigue, weight loss, dysphagia, diarrhea, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, muscle weakness, or digital pain.

On physical exam, there were multiple small, firm subcutaneous nodules—some with a white surface protruding through the skin of her right elbow (FIGURE 1A). The nodules were slightly tender to palpation. On further examination we noted tight, smooth skin on her fingers (FIGURE 1B). Her right thumb was fixed in an extended position (FIGURE 2). There were also small blood vessels on her hands and pitted scars on her fingertips.

FIGURE 1

Elbow nodules and clubbing of the fingers

The 42-year-old patient sought care at the clinic to have slightly tender nodules removed from her right elbow. The patient also had tight skin and clubbing of the fingers.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 2

Thumb fixed in an extended position

The patient had tight skin on her fingers and a pitted scar on her thumb, which was fixed in an extended position.

Diagnosis: CREST syndrome

Our patient had CREST syndrome, a variant of limited systemic scleroderma. CREST syndrome is characterized by Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias.

Systemic scleroderma is a chronic auto-immune disease involving sclerotic, vascular, and inflammatory changes of the skin and internal organs. There are 19 new cases per million adults per year, with an estimated annual prevalence of 276 cases per million adults in the United States.1 Scleroderma occurs in women 4.6 times more often than in men; the mean age at diagnosis is 45 years.1 Although the pathogenesis of scleroderma remains unclear, interactions among leukocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts are likely to be central in this disease.2

According to the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines,3 a diagnosis of systemic scleroderma can be made with either 1 major criterion or 2 minor criteria present. The major criterion is symmetric thickening, tightening, and induration of the skin proximal to the metatarsal-phalangeal or metacarpal-phalangeal joints. This may affect the whole extremity, trunk, neck, and face. The minor criteria include sclerodactyly, digital pitting scars or a loss of substance from the finger pads, and bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis.

Two forms of scleroderma. To improve sensitivity for milder forms of disease, the condition is often divided into diffuse systemic scleroderma (dSSc) or limited systemic scleroderma (lSSc) (TABLE 1), with CREST syndrome being a variant of the limited form.4 Patients with dSSc usually have a rapid diffuse involvement of the trunk, hands, feet, and face with early internal organ involvement. Patients with lSSc, however, usually have slow skin involvement limited to hands, feet, and face, and delayed systemic involvement, if any.

If CREST syndrome is suspected, it is important to look for its cardinal features. Cutaneous calcinosis usually presents over the bony prominences of knees, elbows, spine, and iliac crests, and may be painful. Patients may complain of Raynaud’s phenomenon with triphasic color changes, ie, pallor, cyanosis, and rubor, occurring months to years before sclerosis. Ulcerations at fingertips from Raynaud’s may be evident as pitted scars on physical exam. There is also a nonpitting edema of hands and feet that later progresses into sclerodactyly with tapering of fingers (our patient actually had clubbing). Patients may complain of stiffness of the hands and feet as the sclerosis progresses.

As a result of the edema and fibrosis of the face, patients may lose facial lines and comment that they look younger. Often, they will indicate that they have noticed the appearance of small blood vessels on their face, mouth, or hands. Patients may also complain of gastrointestinal problems such as esophageal reflux, diarrhea, or dysphagia.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of systemic scleroderma4-6

| Diffuse systemic scleroderma | Limited systemic scleroderma (Includes CREST syndrome) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Fatigue and weight loss or gain | None |

| Vascular | Mild to moderate Raynaud’s phenomenon | Moderate to severe Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Cutaneous | Sclerosis to trunk, arms, and face; rapid progression | Sclerosis to hands or toes and face; slow progression; calcinosis is prominent |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgias and deformities, muscle weakness, and tendon friction rubs | Arthralgias |

| Gastrointestinal | GERD, esophageal dysmotility, and malabsorption are common; all may be severe | Mild to moderate GERD and esophageal dysmotility are common; malabsorption is less common |

| Renal | Severe hypertension, and renal infarcts in renal crisis are common | Rare |

| Pulmonary | Pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease are common | Uncommon |

| Cardiac | Cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias are common | Uncommon |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | ||

Differential includes morphea and scleromyxedema

A thorough history, physical exam, lab work, and possibly biopsy will help differentiate systemic scleroderma from the possible diagnoses with sclerosis listed below:

- Morphea features a localized, patchy distribution of skin fibrosis. There is no systemic involvement or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

- Mixed connective tissue disease has features of other autoimmune diseases, along with those of scleroderma.

- Eosinophilic fasciitis involves the fascia and muscle on biopsy. There is sparing of the hands.

- Scleromyxedema represents the skin thickening seen in patients with a gammopathy. Raynaud’s phenomenon may also be present.

- Scleredema is associated with diabetes. Skin changes are found mostly on the neck, shoulders, and upper arms. On rare occasions, there is visceral involvement. Raynaud’s phenomenon is not present.

In addition, the differential includes chronic graft-vs-host disease; lichen sclerosis et atrophicus; amyloidosis; porphyria cutanea et tardia; primary Raynaud’s phenomenon; and polyvinyl chloride, bleomycin, or pentazocyine exposure.

Nailfold capillary abnormalities help with the diagnosis

As noted earlier, diagnosing systemic scleroderma hinges on taking a good history, doing a thorough physical exam, applying the ACR diagnostic criteria, and ordering lab work. The sensitivity of the ACR criteria increases from 67% to 99% with the addition of nailfold capillary abnormalities (telangiectasias), identified using a dermatoscope.5

The initial lab work that you should consider includes an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test, complete blood count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. If the ANA is positive, anticentromere antibody (ACA) and DNA topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody tests should be ordered to see if scleroderma is likely limited or diffuse. ACA will be present in 21% of dSSc and 71% of lSSc cases, whereas Scl-70 will be present in 33% of dSSc and 18% of lSSc cases.6

If the diagnosis is still unclear, do a punch biopsy. Histology in the early phase will show mild cellular infiltrates around dermal blood vessels and at the dermal subcutaneous inter-phase, while the later phase will show thickening of dermis with broadening of collagen fibers and hyalinization of blood vessel walls.6 If lung, kidney, heart, or gastrointestinal involvement is suspected based on symptoms or physical exam, you’ll need to do an organ function work-up.

Treatment focuses on organ-specific problems

Currently, there are no guidelines for the treatment of scleroderma, given that the exact pathogenesis remains unclear and the disease course varies from patient to patient. Pharmacologic therapy is focused on symptoms and organ-specific problems (TABLE 2). Prazosin 1 to 3 mg TID is moderately effective in treating Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to scleroderma7 (SOR: A). Losartan has been reported to reduce the frequency and severity of Raynaud’s phenomenon compared with a low dose of nifedepine,8 in a nonblinded randomized controlled trial (SOR: B). For interstitial lung disease, cyclophosphamide has been found to modestly reduce dyspnea while improving lung function, but it requires close monitoring9 (SOR: A). Bosentan is approved for symptomatic pulmonary hypertension and has been shown to decrease the occurrence of digital ulcers secondary to Raynaud’s phenomenon10 (SOR: A). (Bosentan is available in the United States under a special restricted distribution program called the Tracleer Access Program.)

Nonpharmacologic treatments should also be considered in the management of scleroderma. Advise patients that Raynaud’s phenomenon may be improved by avoiding exposure to the cold and by not smoking (SOR: C). Cutaneous ulcers can be protected with an occlusive dressing and treated with antibiotics if infected (SOR: C). To remove painful calcinotic nodules or release contractures secondary to sclerosis that may limit movement, you may want to consider surgery for your patient11 (SOR: C). If aesthetically unappealing, telangiectasias may be removed with electrosurgery or laser therapy (SOR: C).

Prognosis for scleroderma varies, depending on whether it is diffuse or limited. One large study found that patients with lSSc had a 10-year survival rate of 71%, compared with 21% for patients with dSSc (SOR: B).4 Patients with systemic sclerosis should be monitored for interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, and cardiomyopathy (SOR: C). Prognosis worsens with renal, pulmonary, or cardiac involvement; pulmonary disease is the leading cause of death in dSSc.1

TABLE 2

Medical treatment of systemic scleroderma5-9

| Organ-specific problem/symptom | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Nifedipine, verapamil, losartan, iloprost, prazosin, bosentan* |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Bosentan,* iloprost, captopril, enalapril, sildenafil |

| Interstitial lung disease | Cyclophosphamide, prednisone |

| Cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias | Antiarrhythmics, diuretics, digoxin, pacemaker, transplant |

| Renal failure or crisis | Captopril, kidney dialysis, transplant |

| Skin fibrosis | Methotrexate, cyclosporine, D-penicillamine |

| Arthralgias | Ibuprofen, acetaminophen |

| GERD, gastroparesis, diarrhea | H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics, antibiotics |

| Pruritus | Antihistamines, low-dose topical steroids |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | |

| *Restricted access in the United States. | |

Our patient has a change of heart

Our patient had all the cardinal features of CREST syndrome on history and physical exam. She had an ANA of 1:640 with speckled pattern and ACA and Scl-70 were negative, demonstrating that diagnosis must be made in clinical context and not just based on lab markers. We treated her GERD with lifestyle changes and a proton pump inhibitor. We explained the risks and benefits of cutting out her calcinosis nodules and she chose not to have surgery.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Diaz, MD, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, Mail #7816, San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected]

A 42-year-old woman came to our clinic to have lumps on her right elbow removed. She said the lumps did not bother her, but on further questioning, admitted that her fingers turned white when they were exposed to the cold. She had frequent heartburn, but denied fatigue, weight loss, dysphagia, diarrhea, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, muscle weakness, or digital pain.

On physical exam, there were multiple small, firm subcutaneous nodules—some with a white surface protruding through the skin of her right elbow (FIGURE 1A). The nodules were slightly tender to palpation. On further examination we noted tight, smooth skin on her fingers (FIGURE 1B). Her right thumb was fixed in an extended position (FIGURE 2). There were also small blood vessels on her hands and pitted scars on her fingertips.

FIGURE 1

Elbow nodules and clubbing of the fingers

The 42-year-old patient sought care at the clinic to have slightly tender nodules removed from her right elbow. The patient also had tight skin and clubbing of the fingers.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

FIGURE 2

Thumb fixed in an extended position

The patient had tight skin on her fingers and a pitted scar on her thumb, which was fixed in an extended position.

Diagnosis: CREST syndrome

Our patient had CREST syndrome, a variant of limited systemic scleroderma. CREST syndrome is characterized by Calcinosis cutis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, Esophageal dysmotility, Sclerodactyly, and Telangiectasias.

Systemic scleroderma is a chronic auto-immune disease involving sclerotic, vascular, and inflammatory changes of the skin and internal organs. There are 19 new cases per million adults per year, with an estimated annual prevalence of 276 cases per million adults in the United States.1 Scleroderma occurs in women 4.6 times more often than in men; the mean age at diagnosis is 45 years.1 Although the pathogenesis of scleroderma remains unclear, interactions among leukocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts are likely to be central in this disease.2

According to the 1980 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) guidelines,3 a diagnosis of systemic scleroderma can be made with either 1 major criterion or 2 minor criteria present. The major criterion is symmetric thickening, tightening, and induration of the skin proximal to the metatarsal-phalangeal or metacarpal-phalangeal joints. This may affect the whole extremity, trunk, neck, and face. The minor criteria include sclerodactyly, digital pitting scars or a loss of substance from the finger pads, and bibasilar pulmonary fibrosis.

Two forms of scleroderma. To improve sensitivity for milder forms of disease, the condition is often divided into diffuse systemic scleroderma (dSSc) or limited systemic scleroderma (lSSc) (TABLE 1), with CREST syndrome being a variant of the limited form.4 Patients with dSSc usually have a rapid diffuse involvement of the trunk, hands, feet, and face with early internal organ involvement. Patients with lSSc, however, usually have slow skin involvement limited to hands, feet, and face, and delayed systemic involvement, if any.

If CREST syndrome is suspected, it is important to look for its cardinal features. Cutaneous calcinosis usually presents over the bony prominences of knees, elbows, spine, and iliac crests, and may be painful. Patients may complain of Raynaud’s phenomenon with triphasic color changes, ie, pallor, cyanosis, and rubor, occurring months to years before sclerosis. Ulcerations at fingertips from Raynaud’s may be evident as pitted scars on physical exam. There is also a nonpitting edema of hands and feet that later progresses into sclerodactyly with tapering of fingers (our patient actually had clubbing). Patients may complain of stiffness of the hands and feet as the sclerosis progresses.

As a result of the edema and fibrosis of the face, patients may lose facial lines and comment that they look younger. Often, they will indicate that they have noticed the appearance of small blood vessels on their face, mouth, or hands. Patients may also complain of gastrointestinal problems such as esophageal reflux, diarrhea, or dysphagia.

TABLE 1

Characteristics of systemic scleroderma4-6

| Diffuse systemic scleroderma | Limited systemic scleroderma (Includes CREST syndrome) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutional | Fatigue and weight loss or gain | None |

| Vascular | Mild to moderate Raynaud’s phenomenon | Moderate to severe Raynaud’s phenomenon |

| Cutaneous | Sclerosis to trunk, arms, and face; rapid progression | Sclerosis to hands or toes and face; slow progression; calcinosis is prominent |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgias and deformities, muscle weakness, and tendon friction rubs | Arthralgias |

| Gastrointestinal | GERD, esophageal dysmotility, and malabsorption are common; all may be severe | Mild to moderate GERD and esophageal dysmotility are common; malabsorption is less common |

| Renal | Severe hypertension, and renal infarcts in renal crisis are common | Rare |

| Pulmonary | Pulmonary hypertension and interstitial lung disease are common | Uncommon |

| Cardiac | Cardiomyopathy, heart failure, and arrhythmias are common | Uncommon |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | ||

Differential includes morphea and scleromyxedema

A thorough history, physical exam, lab work, and possibly biopsy will help differentiate systemic scleroderma from the possible diagnoses with sclerosis listed below:

- Morphea features a localized, patchy distribution of skin fibrosis. There is no systemic involvement or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

- Mixed connective tissue disease has features of other autoimmune diseases, along with those of scleroderma.

- Eosinophilic fasciitis involves the fascia and muscle on biopsy. There is sparing of the hands.

- Scleromyxedema represents the skin thickening seen in patients with a gammopathy. Raynaud’s phenomenon may also be present.

- Scleredema is associated with diabetes. Skin changes are found mostly on the neck, shoulders, and upper arms. On rare occasions, there is visceral involvement. Raynaud’s phenomenon is not present.

In addition, the differential includes chronic graft-vs-host disease; lichen sclerosis et atrophicus; amyloidosis; porphyria cutanea et tardia; primary Raynaud’s phenomenon; and polyvinyl chloride, bleomycin, or pentazocyine exposure.

Nailfold capillary abnormalities help with the diagnosis

As noted earlier, diagnosing systemic scleroderma hinges on taking a good history, doing a thorough physical exam, applying the ACR diagnostic criteria, and ordering lab work. The sensitivity of the ACR criteria increases from 67% to 99% with the addition of nailfold capillary abnormalities (telangiectasias), identified using a dermatoscope.5

The initial lab work that you should consider includes an antinuclear antibody (ANA) test, complete blood count, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. If the ANA is positive, anticentromere antibody (ACA) and DNA topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody tests should be ordered to see if scleroderma is likely limited or diffuse. ACA will be present in 21% of dSSc and 71% of lSSc cases, whereas Scl-70 will be present in 33% of dSSc and 18% of lSSc cases.6

If the diagnosis is still unclear, do a punch biopsy. Histology in the early phase will show mild cellular infiltrates around dermal blood vessels and at the dermal subcutaneous inter-phase, while the later phase will show thickening of dermis with broadening of collagen fibers and hyalinization of blood vessel walls.6 If lung, kidney, heart, or gastrointestinal involvement is suspected based on symptoms or physical exam, you’ll need to do an organ function work-up.

Treatment focuses on organ-specific problems

Currently, there are no guidelines for the treatment of scleroderma, given that the exact pathogenesis remains unclear and the disease course varies from patient to patient. Pharmacologic therapy is focused on symptoms and organ-specific problems (TABLE 2). Prazosin 1 to 3 mg TID is moderately effective in treating Raynaud’s phenomenon secondary to scleroderma7 (SOR: A). Losartan has been reported to reduce the frequency and severity of Raynaud’s phenomenon compared with a low dose of nifedepine,8 in a nonblinded randomized controlled trial (SOR: B). For interstitial lung disease, cyclophosphamide has been found to modestly reduce dyspnea while improving lung function, but it requires close monitoring9 (SOR: A). Bosentan is approved for symptomatic pulmonary hypertension and has been shown to decrease the occurrence of digital ulcers secondary to Raynaud’s phenomenon10 (SOR: A). (Bosentan is available in the United States under a special restricted distribution program called the Tracleer Access Program.)

Nonpharmacologic treatments should also be considered in the management of scleroderma. Advise patients that Raynaud’s phenomenon may be improved by avoiding exposure to the cold and by not smoking (SOR: C). Cutaneous ulcers can be protected with an occlusive dressing and treated with antibiotics if infected (SOR: C). To remove painful calcinotic nodules or release contractures secondary to sclerosis that may limit movement, you may want to consider surgery for your patient11 (SOR: C). If aesthetically unappealing, telangiectasias may be removed with electrosurgery or laser therapy (SOR: C).

Prognosis for scleroderma varies, depending on whether it is diffuse or limited. One large study found that patients with lSSc had a 10-year survival rate of 71%, compared with 21% for patients with dSSc (SOR: B).4 Patients with systemic sclerosis should be monitored for interstitial lung disease, pulmonary hypertension, renal failure, and cardiomyopathy (SOR: C). Prognosis worsens with renal, pulmonary, or cardiac involvement; pulmonary disease is the leading cause of death in dSSc.1

TABLE 2

Medical treatment of systemic scleroderma5-9

| Organ-specific problem/symptom | Treatment |

|---|---|

| Raynaud’s phenomenon | Nifedipine, verapamil, losartan, iloprost, prazosin, bosentan* |

| Pulmonary hypertension | Bosentan,* iloprost, captopril, enalapril, sildenafil |

| Interstitial lung disease | Cyclophosphamide, prednisone |

| Cardiomyopathy or arrhythmias | Antiarrhythmics, diuretics, digoxin, pacemaker, transplant |

| Renal failure or crisis | Captopril, kidney dialysis, transplant |

| Skin fibrosis | Methotrexate, cyclosporine, D-penicillamine |

| Arthralgias | Ibuprofen, acetaminophen |

| GERD, gastroparesis, diarrhea | H2 blockers, proton pump inhibitors, prokinetics, antibiotics |

| Pruritus | Antihistamines, low-dose topical steroids |

| GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease. | |

| *Restricted access in the United States. | |

Our patient has a change of heart

Our patient had all the cardinal features of CREST syndrome on history and physical exam. She had an ANA of 1:640 with speckled pattern and ACA and Scl-70 were negative, demonstrating that diagnosis must be made in clinical context and not just based on lab markers. We treated her GERD with lifestyle changes and a proton pump inhibitor. We explained the risks and benefits of cutting out her calcinosis nodules and she chose not to have surgery.

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CORRESPONDENCE

Lucia Diaz, MD, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, Mail #7816, San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected]

1. Mayes MD, Lacey JV, Jr, Beebe-Deemer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2246-2255.

2. Hasegawa M, Sato S. The roles of chemokines in leukocyte recruitment in systemic sclerosis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3637-3647.

3. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581-590.

4. Barnett AJ, Miller MH, Littlejohn GO. A survival study of patients with scleroderma diagnosed over 30 years (1953-1983): the value of a simple cutaneous classification in the early stages of disease. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:276-283.

5. Hudson M, Taillerfer S, Steele R, et al. Improving sensitivity of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:754-757.

6. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

7. Harding SE, Tingey PC, Pope J, et al. Prazosin for Raynaud’s phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998;(2):CD000956.-

8. Dziadzio M, Denton CP, Smith R, et al. Losartan therapy for Raynaud’s phenomenon and scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2646-2655.

9. Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements P, et al. For the Scleroderma Lung Study Research Group. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655-2666.

10. Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelial receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3884-3995.

11. Melone CP, Jr, McLoughlin JC, Beldner S. Surgical management of the hand in scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:514-520.

1. Mayes MD, Lacey JV, Jr, Beebe-Deemer J, et al. Prevalence, incidence, survival, and disease characteristics of systemic sclerosis in large US population. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:2246-2255.

2. Hasegawa M, Sato S. The roles of chemokines in leukocyte recruitment in systemic sclerosis. Front Biosci. 2008;13:3637-3647.

3. Preliminary criteria for the classification of systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Subcommittee for scleroderma criteria of the American Rheumatism Association Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23:581-590.

4. Barnett AJ, Miller MH, Littlejohn GO. A survival study of patients with scleroderma diagnosed over 30 years (1953-1983): the value of a simple cutaneous classification in the early stages of disease. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:276-283.

5. Hudson M, Taillerfer S, Steele R, et al. Improving sensitivity of the American College of Rheumatology classification criteria for systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:754-757.

6. Wolff K, Johnson RA, Suurmond D. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 5th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2005.

7. Harding SE, Tingey PC, Pope J, et al. Prazosin for Raynaud’s phenomenon in progressive systemic sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1998;(2):CD000956.-

8. Dziadzio M, Denton CP, Smith R, et al. Losartan therapy for Raynaud’s phenomenon and scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:2646-2655.

9. Tashkin DP, Elashoff R, Clements P, et al. For the Scleroderma Lung Study Research Group. Cyclophosphamide versus placebo in scleroderma lung disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2655-2666.

10. Korn JH, Mayes M, Matucci Cerinic M, et al. Digital ulcers in systemic sclerosis: prevention by treatment with bosentan, an oral endothelial receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3884-3995.

11. Melone CP, Jr, McLoughlin JC, Beldner S. Surgical management of the hand in scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1999;11:514-520.