User login

Improving High-Risk Osteoporosis Medication Adherence and Safety With an Automated Dashboard

Improving High-Risk Osteoporosis Medication Adherence and Safety With an Automated Dashboard

Osteoporotic fragility fractures constitute a significant public health concern, with 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men aged > 50 years sustaining an osteoporotic fracture.1 Osteoporotic fractures are costly and associated with reduced quality of life and impaired survival.2-6 Many interventions including fall mitigation, calcium, vitamin D supplementation, and osteoporosis—specific medications reduce fracture risk.7 New medications for treating osteoporosis, including anabolic therapies, are costly and require clinical oversight to ensure safe delivery. This includes laboratory monitoring, timing of in-clinic dosing and provision of sequence therapy.8,9 COVID-19 introduced numerous barriers to osteoporosis care, raising concerns for medication interruption and patients lost to follow-up, which made monitoring these high risk and costly medications even more important.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was an early adopter of using the electronic health record to analyze and implement system-wide processes for population management and quality improvement.10 This enabled the creation of clinical dashboards to display key performance indicator data that support quality improvement and patient care initiatives.11-15 The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) has a dedicated osteoporosis clinic focused on preventing and treating veterans at high risk for fracture. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, particularly those requiring timed sequential therapy to prevent bone mineral density loss and rebound osteoporotic fractures, close monitoring and follow-up is required. The COVID-19 pandemic made clear the need for proactive osteoporosis management. This article describes the creation and use of an automated clinic dashboard to identify and contact veterans with osteoporosis-related care needs, such as prescription refills, laboratory tests, and clinical visits.

Methods

An automated dashboard was created in partnership with VA pharmacy clinical informatics to display the osteoporosis medication prescription (including last refill), monitoring laboratory test values and most recent osteoporosis clinic visit for each clinic patient. Data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse were extracted. The resulting tables were used to create a patient cohort with ≥ 1 active medication for alendronate, zoledronic acid, the parathyroid hormone analogues (PTH) teriparatide or abaloparatide, denosumab, or romosozumab. Notably, alendronate was the only oral bisphosphonate prescribed in the clinic. These data were formatted and displayed using Microsoft SQL Server Reporting Services. The secure and encrypted dashboard alerts the clinic staff when prescriptions, appointments, or laboratory tests, such as estimated glomerular filtration rate, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, calcium, and PTH are overdue or out of reference range. The dashboard tracked the most recent clinic visit or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan if performed within the VA. Overdue laboratory test alerts for bisphosphonates were flagged if delayed 12 months and 6 months for all other medications.

On March 20, 2021, the VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic was staffed by 1 endocrinologist, 1 geriatrician, 1 rheumatologist, and 1 registered nurse (RN) coordinator. Overdue or out-of-range alerts were reviewed weekly by the RN coordinator, who addressed alerts. For any overdue laboratory work or prescription refills, the RN coordinator alerted the primary osteoporosis physician via the electronic health record for updated orders. Patients were contacted by phone to schedule a clinic visit, complete ordered laboratory work, or discuss osteoporosis medication refills based on the need identified by the dashboard. A letter was mailed to the patient requesting they contact the osteoporosis clinic for patients who could not be reached by phone after 2 attempts. If 3 attempts (2 phone calls and a letter) were unsuccessful, the osteoporosis physician was alerted so they could either call the patient, alert the primary referring clinician, or discontinue the osteoporosis medication.

Results

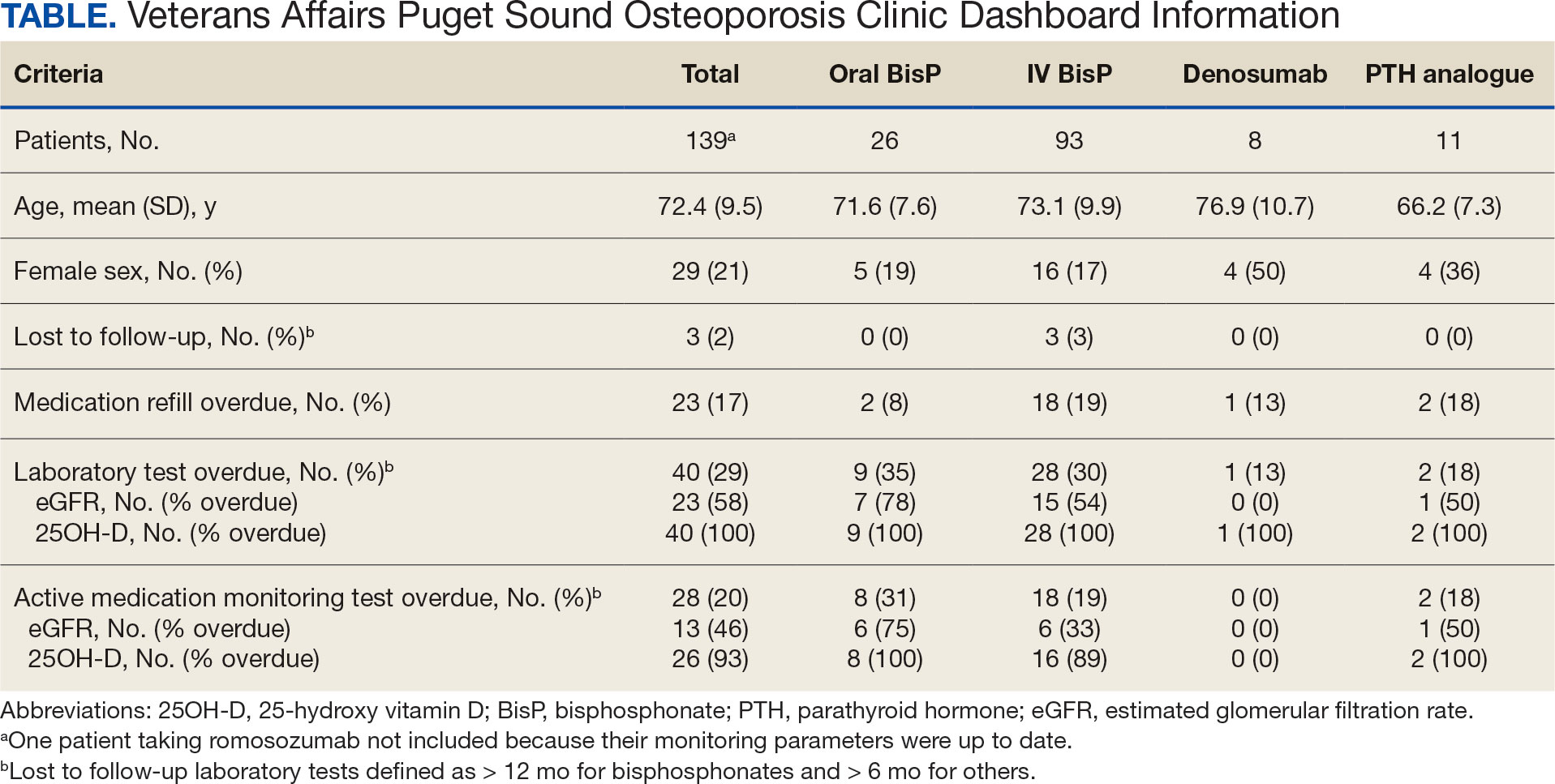

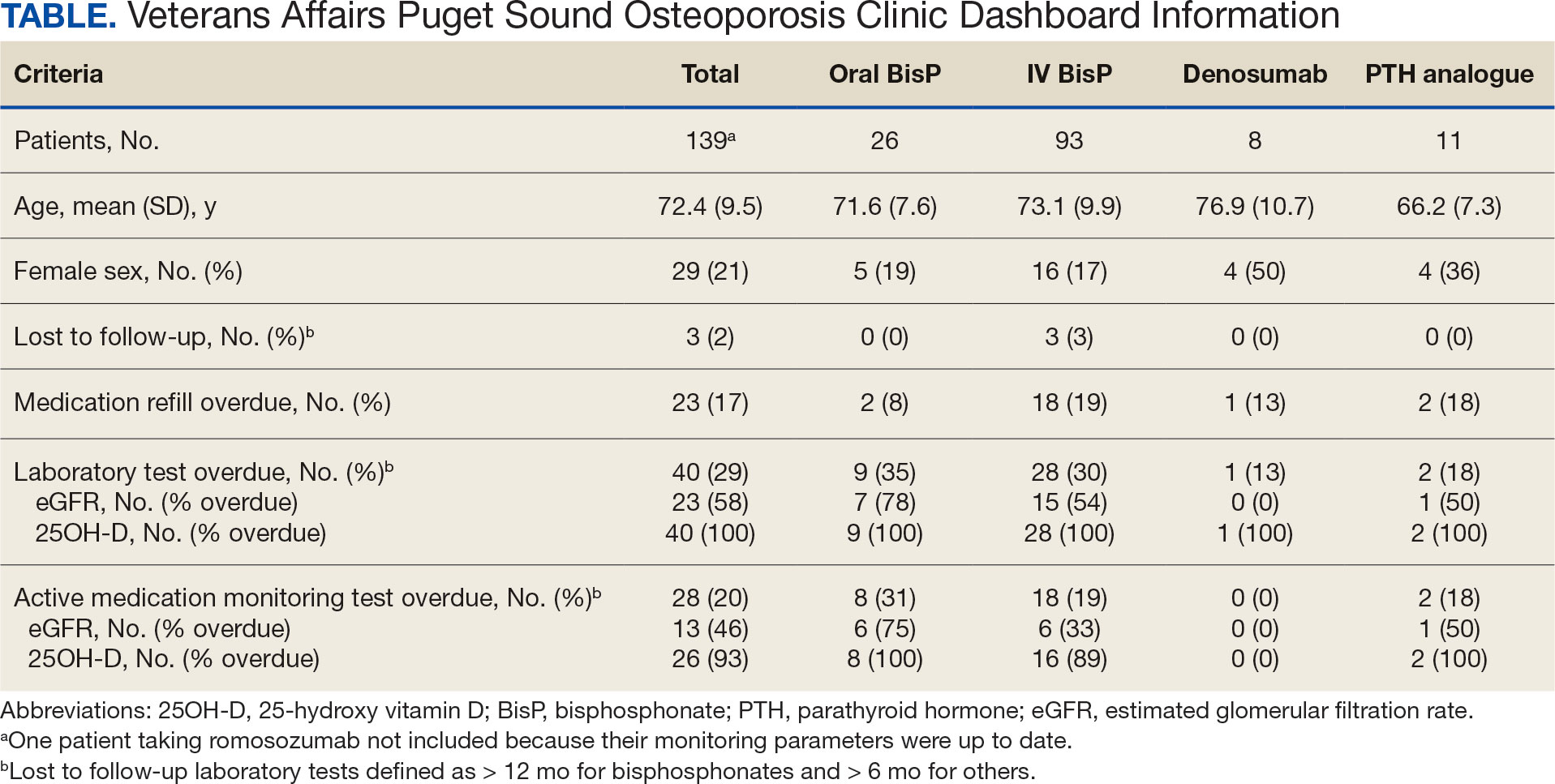

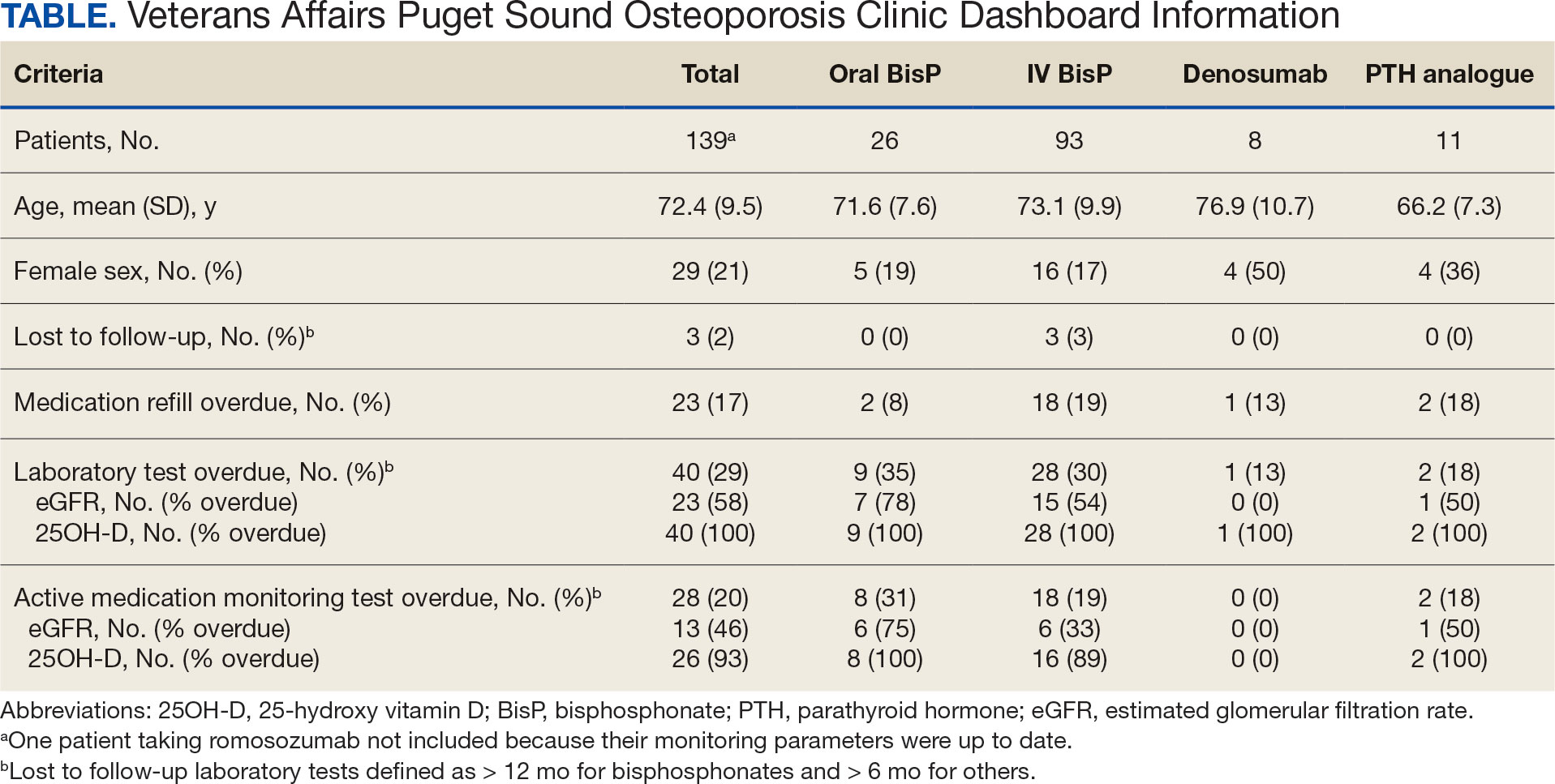

As of March 20, 2021, 139 patients were included on the dashboard. Ninety-two patients (66%) had unmet care needs and 29% were female. Ages ranged from 40 to 100 years (Table). The dashboard alerted the team to 3 patients lost to follow-up, all of whom had transferred to care outside the clinic. Twenty-three patients (17%) had overdue medications, including 2 (9%) who had not refilled oral bisphosphonate and 18 (78%) who were overdue for intravenous bisphosphonate treatment. One veteran flagged as overdue for their denosumab injection was unable to receive it due to a significant change in health status. Two veterans were overdue for a PTH analogue refill, 1 of whom had completed their course and transitioned to bisphosphonate.

The most common alert was 40 patients (29%) with overdue laboratory tests, 37 of which were receiving bisphosphonates. One patient included on the dashboard was taking romosozumab and all their monitoring parameters were up to date, thus their data were not included in the Table to prevent possible identification.

Discussion

A dashboard alerted the osteoporosis clinic team to veterans who were overdue for visits, laboratory work, and prescription renewals. Overall, 92 patients (66%) had unmet care needs identified by the dashboard, all of which were addressed with phone calls and/or letters. Most of the overdue medication refills and laboratory tests were for patients taking bisphosphonates avoiding VAPSHCS during the COVID-19 pandemic. The dashboard enabled the RN coordinator to promptly contact the patient, facilitate coordination of care requirements, and guarantee the safe and efficient delivery of osteoporosis care.

The VA has historically been a leader in the creation of clinical dashboards to support health campaigns.11,12 These dashboards have successfully improved quality metrics towards the treatment of hepatitis C virus, heart failure, and highrisk opioid prescribing.13-15 Data have shown that successful clinical dashboard implementation must be done in conjunction with protected time or staff to support care improvements.16 Additionally, the time required for clinical dashboards can limit their sustainability and feasibility.17 A study aimed at improving osteoporosis care for patients with Parkinson disease found that weekly multidisciplinary review of at-risk patients resulted in all new patients and 91% of follow-up patients receiving evidence- based osteoporosis treatments.17 However, despite the benefits, the intervention required significant time and resources. In contrast, the osteoporosis dashboard implemented at VAPSHCS was not time or resource intensive, requiring about 1 hour per week for the RN coordinator to review the dashboard and coordinate patient care needs.

Limitations

This study setting is unique from other health care organizations or VA health care systems. Implementation of a similar dashboard in other clinical settings where patients receive medical care in multiple health care systems may differ. The VA dedicates resources to support veteran population health management, which may not be available in other health care systems.11,12 These issues may pose a barrier to implementing a similar osteoporosis dashboard in non-VA facilities. In addition, it is significant that while the dashboard can be reconfigured and adapted to track veterans across different VA facilities, certain complexities arise if essential data, such as laboratory tests and DXA imaging, are conducted outside of VA facilities. In such cases, manual entry of this information into the dashboard would be necessary. Because the dashboard was quickly developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study lacked preimplementation data on laboratory testing, medication refills, and DXA imaging, which would have enabled a comparison of adherence before and after dashboard implementation. Finally, we acknowledge the delay in publishing these findings; however, we believe sharing innovative approaches to providing care for high-risk populations is essential, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

An osteoporosis clinic dashboard served as a valuable clinical support tool to ensure safe and effective osteoporosis medication delivery at VAPSHCS. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, this dashboard plays a vital role in facilitating care coordination for patients receiving these high-risk treatments.18 Use of the dashboard supported the effective use of high-cost osteoporosis medications and is likely to improve clinical osteoporosis outcomes.

Despite the known fracture risk reduction, osteoporosis medication adherence is low.19,20 Maintaining consistent pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis is essential not only for fracture prevention but also reducing health care costs related to osteoporosis and preserving patient independence and functionality.21-24 While initially developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the dashboard remains useful. The VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic is now staffed by 2 physicians (endocrine and rheumatology) and the dashboard is still in use. The RN coordinator spends about 15 minutes per week using the dashboard and managing the 67 veterans on osteoporosis therapy. This dashboard represents a sustainable clinical tool with the capacity to minimize osteoporosis care gaps and improve outcomes.

- Johnell O, Kanis J. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(suppl 2):S3-S7. doi:10.1007/s00198-004-1702-6

- van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001;29:517-522. doi:10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00614-7

- Dennison E, Cooper C. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Horm Res. 2000;54(suppl 1):58-63. doi:10.1159/000063449

- Cooper C. Epidemiology and public health impact of osteoporosis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1993;7:459-477. doi:10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80073-1

- Dolan P, Torgerson DJ. The cost of treating osteoporotic fractures in the United Kingdom female population. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:611-617. doi:10.1007/s001980050107

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465-475. doi:10.1359/jbmr.061113

- Palacios S. Medical treatment of osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2022;25:43-49. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1951697

- Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:1595-1622. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00221

- Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1802-1822. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3045

- Lau MK, Bounthavong M, Kay CL, Harvey MA, Christopher MLD. Clinical dashboard development and use for academic detailing in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(2S):S96-S103.e3. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2018.12.006

- Mould DR, D’Haens G, Upton RN. Clinical decision support tools: the evolution of a revolution. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:405-418. doi:10.1002/cpt.334

- Kizer KW, Fonseca ML, Long LM. The veterans healthcare system: preparing for the twenty-first century. Hosp Health Serv Adm. 1997;42:283-298.

- Park A, Gonzalez R, Chartier M, et al. Screening and treating hepatitis c in the VA: achieving excellence using lean and system redesign. Fed Pract. 2018;35:24-29.

- Brownell N, Kay C, Parra D, et al. Development and optimization of the Veterans Affairs’ national heart failure dashboard for population health management. J Card Fail. 2024;30:452-459. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.08.024

- Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the opioid safety initiative on opioidrelated prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158:833-839. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837

- Twohig PA, Rivington JR, Gunzler D, Daprano J, Margolius D. Clinician dashboard views and improvement in preventative health outcome measures: a retrospective analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:475. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4327-3

- Singh I, Fletcher R, Scanlon L, Tyler M, Aithal S. A quality improvement initiative on the management of osteoporosis in older people with Parkinsonism. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5:u210921.w5756. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u210921.w5756

- Anastasilakis AD, Makras P, Yavropoulou MP, Tabacco G, Naciu AM, Palermo A. Denosumab discontinuation and the rebound phenomenon: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2021;10:152. doi:10.3390/jcm10010152

- Sharman Moser S, Yu J, Goldshtein I, et al. Cost and consequences of nonadherence with oral bisphosphonate therapy: findings from a real-world data analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:262-269. doi:10.1177/1060028015626935

- Olsen KR, Hansen C, Abrahamsen B. Association between refill compliance to oral bisphosphonate treatment, incident fractures, and health care costs--an analysis using national health databases. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2639-2647. doi:10.1007/s00198-013-2365-y

- Blouin J, Dragomir A, Fredette M, Ste-Marie LG, Fernandes JC, Perreault S. Comparison of direct health care costs related to the pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis and to the management of osteoporotic fractures among compliant and noncompliant users of alendronate and risedronate: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1571-1581. doi:10.1007/s00198-008-0818-5

- Cotté F-E, De Pouvourville G. Cost of non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates in post-menopausal osteoporosis treatment in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:151. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-151

- Cho H, Byun J-H, Song I, et al. Effect of improved medication adherence on health care costs in osteoporosis patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11470. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011470

- Li N, Cornelissen D, Silverman S, et al. An updated systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of drugs for osteoporosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39:181-209. doi:10.1007/s40273-020-00965-9

Osteoporotic fragility fractures constitute a significant public health concern, with 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men aged > 50 years sustaining an osteoporotic fracture.1 Osteoporotic fractures are costly and associated with reduced quality of life and impaired survival.2-6 Many interventions including fall mitigation, calcium, vitamin D supplementation, and osteoporosis—specific medications reduce fracture risk.7 New medications for treating osteoporosis, including anabolic therapies, are costly and require clinical oversight to ensure safe delivery. This includes laboratory monitoring, timing of in-clinic dosing and provision of sequence therapy.8,9 COVID-19 introduced numerous barriers to osteoporosis care, raising concerns for medication interruption and patients lost to follow-up, which made monitoring these high risk and costly medications even more important.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was an early adopter of using the electronic health record to analyze and implement system-wide processes for population management and quality improvement.10 This enabled the creation of clinical dashboards to display key performance indicator data that support quality improvement and patient care initiatives.11-15 The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) has a dedicated osteoporosis clinic focused on preventing and treating veterans at high risk for fracture. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, particularly those requiring timed sequential therapy to prevent bone mineral density loss and rebound osteoporotic fractures, close monitoring and follow-up is required. The COVID-19 pandemic made clear the need for proactive osteoporosis management. This article describes the creation and use of an automated clinic dashboard to identify and contact veterans with osteoporosis-related care needs, such as prescription refills, laboratory tests, and clinical visits.

Methods

An automated dashboard was created in partnership with VA pharmacy clinical informatics to display the osteoporosis medication prescription (including last refill), monitoring laboratory test values and most recent osteoporosis clinic visit for each clinic patient. Data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse were extracted. The resulting tables were used to create a patient cohort with ≥ 1 active medication for alendronate, zoledronic acid, the parathyroid hormone analogues (PTH) teriparatide or abaloparatide, denosumab, or romosozumab. Notably, alendronate was the only oral bisphosphonate prescribed in the clinic. These data were formatted and displayed using Microsoft SQL Server Reporting Services. The secure and encrypted dashboard alerts the clinic staff when prescriptions, appointments, or laboratory tests, such as estimated glomerular filtration rate, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, calcium, and PTH are overdue or out of reference range. The dashboard tracked the most recent clinic visit or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan if performed within the VA. Overdue laboratory test alerts for bisphosphonates were flagged if delayed 12 months and 6 months for all other medications.

On March 20, 2021, the VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic was staffed by 1 endocrinologist, 1 geriatrician, 1 rheumatologist, and 1 registered nurse (RN) coordinator. Overdue or out-of-range alerts were reviewed weekly by the RN coordinator, who addressed alerts. For any overdue laboratory work or prescription refills, the RN coordinator alerted the primary osteoporosis physician via the electronic health record for updated orders. Patients were contacted by phone to schedule a clinic visit, complete ordered laboratory work, or discuss osteoporosis medication refills based on the need identified by the dashboard. A letter was mailed to the patient requesting they contact the osteoporosis clinic for patients who could not be reached by phone after 2 attempts. If 3 attempts (2 phone calls and a letter) were unsuccessful, the osteoporosis physician was alerted so they could either call the patient, alert the primary referring clinician, or discontinue the osteoporosis medication.

Results

As of March 20, 2021, 139 patients were included on the dashboard. Ninety-two patients (66%) had unmet care needs and 29% were female. Ages ranged from 40 to 100 years (Table). The dashboard alerted the team to 3 patients lost to follow-up, all of whom had transferred to care outside the clinic. Twenty-three patients (17%) had overdue medications, including 2 (9%) who had not refilled oral bisphosphonate and 18 (78%) who were overdue for intravenous bisphosphonate treatment. One veteran flagged as overdue for their denosumab injection was unable to receive it due to a significant change in health status. Two veterans were overdue for a PTH analogue refill, 1 of whom had completed their course and transitioned to bisphosphonate.

The most common alert was 40 patients (29%) with overdue laboratory tests, 37 of which were receiving bisphosphonates. One patient included on the dashboard was taking romosozumab and all their monitoring parameters were up to date, thus their data were not included in the Table to prevent possible identification.

Discussion

A dashboard alerted the osteoporosis clinic team to veterans who were overdue for visits, laboratory work, and prescription renewals. Overall, 92 patients (66%) had unmet care needs identified by the dashboard, all of which were addressed with phone calls and/or letters. Most of the overdue medication refills and laboratory tests were for patients taking bisphosphonates avoiding VAPSHCS during the COVID-19 pandemic. The dashboard enabled the RN coordinator to promptly contact the patient, facilitate coordination of care requirements, and guarantee the safe and efficient delivery of osteoporosis care.

The VA has historically been a leader in the creation of clinical dashboards to support health campaigns.11,12 These dashboards have successfully improved quality metrics towards the treatment of hepatitis C virus, heart failure, and highrisk opioid prescribing.13-15 Data have shown that successful clinical dashboard implementation must be done in conjunction with protected time or staff to support care improvements.16 Additionally, the time required for clinical dashboards can limit their sustainability and feasibility.17 A study aimed at improving osteoporosis care for patients with Parkinson disease found that weekly multidisciplinary review of at-risk patients resulted in all new patients and 91% of follow-up patients receiving evidence- based osteoporosis treatments.17 However, despite the benefits, the intervention required significant time and resources. In contrast, the osteoporosis dashboard implemented at VAPSHCS was not time or resource intensive, requiring about 1 hour per week for the RN coordinator to review the dashboard and coordinate patient care needs.

Limitations

This study setting is unique from other health care organizations or VA health care systems. Implementation of a similar dashboard in other clinical settings where patients receive medical care in multiple health care systems may differ. The VA dedicates resources to support veteran population health management, which may not be available in other health care systems.11,12 These issues may pose a barrier to implementing a similar osteoporosis dashboard in non-VA facilities. In addition, it is significant that while the dashboard can be reconfigured and adapted to track veterans across different VA facilities, certain complexities arise if essential data, such as laboratory tests and DXA imaging, are conducted outside of VA facilities. In such cases, manual entry of this information into the dashboard would be necessary. Because the dashboard was quickly developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study lacked preimplementation data on laboratory testing, medication refills, and DXA imaging, which would have enabled a comparison of adherence before and after dashboard implementation. Finally, we acknowledge the delay in publishing these findings; however, we believe sharing innovative approaches to providing care for high-risk populations is essential, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

An osteoporosis clinic dashboard served as a valuable clinical support tool to ensure safe and effective osteoporosis medication delivery at VAPSHCS. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, this dashboard plays a vital role in facilitating care coordination for patients receiving these high-risk treatments.18 Use of the dashboard supported the effective use of high-cost osteoporosis medications and is likely to improve clinical osteoporosis outcomes.

Despite the known fracture risk reduction, osteoporosis medication adherence is low.19,20 Maintaining consistent pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis is essential not only for fracture prevention but also reducing health care costs related to osteoporosis and preserving patient independence and functionality.21-24 While initially developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the dashboard remains useful. The VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic is now staffed by 2 physicians (endocrine and rheumatology) and the dashboard is still in use. The RN coordinator spends about 15 minutes per week using the dashboard and managing the 67 veterans on osteoporosis therapy. This dashboard represents a sustainable clinical tool with the capacity to minimize osteoporosis care gaps and improve outcomes.

Osteoporotic fragility fractures constitute a significant public health concern, with 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men aged > 50 years sustaining an osteoporotic fracture.1 Osteoporotic fractures are costly and associated with reduced quality of life and impaired survival.2-6 Many interventions including fall mitigation, calcium, vitamin D supplementation, and osteoporosis—specific medications reduce fracture risk.7 New medications for treating osteoporosis, including anabolic therapies, are costly and require clinical oversight to ensure safe delivery. This includes laboratory monitoring, timing of in-clinic dosing and provision of sequence therapy.8,9 COVID-19 introduced numerous barriers to osteoporosis care, raising concerns for medication interruption and patients lost to follow-up, which made monitoring these high risk and costly medications even more important.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) was an early adopter of using the electronic health record to analyze and implement system-wide processes for population management and quality improvement.10 This enabled the creation of clinical dashboards to display key performance indicator data that support quality improvement and patient care initiatives.11-15 The VA Puget Sound Health Care System (VAPSHCS) has a dedicated osteoporosis clinic focused on preventing and treating veterans at high risk for fracture. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, particularly those requiring timed sequential therapy to prevent bone mineral density loss and rebound osteoporotic fractures, close monitoring and follow-up is required. The COVID-19 pandemic made clear the need for proactive osteoporosis management. This article describes the creation and use of an automated clinic dashboard to identify and contact veterans with osteoporosis-related care needs, such as prescription refills, laboratory tests, and clinical visits.

Methods

An automated dashboard was created in partnership with VA pharmacy clinical informatics to display the osteoporosis medication prescription (including last refill), monitoring laboratory test values and most recent osteoporosis clinic visit for each clinic patient. Data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse were extracted. The resulting tables were used to create a patient cohort with ≥ 1 active medication for alendronate, zoledronic acid, the parathyroid hormone analogues (PTH) teriparatide or abaloparatide, denosumab, or romosozumab. Notably, alendronate was the only oral bisphosphonate prescribed in the clinic. These data were formatted and displayed using Microsoft SQL Server Reporting Services. The secure and encrypted dashboard alerts the clinic staff when prescriptions, appointments, or laboratory tests, such as estimated glomerular filtration rate, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, calcium, and PTH are overdue or out of reference range. The dashboard tracked the most recent clinic visit or dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan if performed within the VA. Overdue laboratory test alerts for bisphosphonates were flagged if delayed 12 months and 6 months for all other medications.

On March 20, 2021, the VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic was staffed by 1 endocrinologist, 1 geriatrician, 1 rheumatologist, and 1 registered nurse (RN) coordinator. Overdue or out-of-range alerts were reviewed weekly by the RN coordinator, who addressed alerts. For any overdue laboratory work or prescription refills, the RN coordinator alerted the primary osteoporosis physician via the electronic health record for updated orders. Patients were contacted by phone to schedule a clinic visit, complete ordered laboratory work, or discuss osteoporosis medication refills based on the need identified by the dashboard. A letter was mailed to the patient requesting they contact the osteoporosis clinic for patients who could not be reached by phone after 2 attempts. If 3 attempts (2 phone calls and a letter) were unsuccessful, the osteoporosis physician was alerted so they could either call the patient, alert the primary referring clinician, or discontinue the osteoporosis medication.

Results

As of March 20, 2021, 139 patients were included on the dashboard. Ninety-two patients (66%) had unmet care needs and 29% were female. Ages ranged from 40 to 100 years (Table). The dashboard alerted the team to 3 patients lost to follow-up, all of whom had transferred to care outside the clinic. Twenty-three patients (17%) had overdue medications, including 2 (9%) who had not refilled oral bisphosphonate and 18 (78%) who were overdue for intravenous bisphosphonate treatment. One veteran flagged as overdue for their denosumab injection was unable to receive it due to a significant change in health status. Two veterans were overdue for a PTH analogue refill, 1 of whom had completed their course and transitioned to bisphosphonate.

The most common alert was 40 patients (29%) with overdue laboratory tests, 37 of which were receiving bisphosphonates. One patient included on the dashboard was taking romosozumab and all their monitoring parameters were up to date, thus their data were not included in the Table to prevent possible identification.

Discussion

A dashboard alerted the osteoporosis clinic team to veterans who were overdue for visits, laboratory work, and prescription renewals. Overall, 92 patients (66%) had unmet care needs identified by the dashboard, all of which were addressed with phone calls and/or letters. Most of the overdue medication refills and laboratory tests were for patients taking bisphosphonates avoiding VAPSHCS during the COVID-19 pandemic. The dashboard enabled the RN coordinator to promptly contact the patient, facilitate coordination of care requirements, and guarantee the safe and efficient delivery of osteoporosis care.

The VA has historically been a leader in the creation of clinical dashboards to support health campaigns.11,12 These dashboards have successfully improved quality metrics towards the treatment of hepatitis C virus, heart failure, and highrisk opioid prescribing.13-15 Data have shown that successful clinical dashboard implementation must be done in conjunction with protected time or staff to support care improvements.16 Additionally, the time required for clinical dashboards can limit their sustainability and feasibility.17 A study aimed at improving osteoporosis care for patients with Parkinson disease found that weekly multidisciplinary review of at-risk patients resulted in all new patients and 91% of follow-up patients receiving evidence- based osteoporosis treatments.17 However, despite the benefits, the intervention required significant time and resources. In contrast, the osteoporosis dashboard implemented at VAPSHCS was not time or resource intensive, requiring about 1 hour per week for the RN coordinator to review the dashboard and coordinate patient care needs.

Limitations

This study setting is unique from other health care organizations or VA health care systems. Implementation of a similar dashboard in other clinical settings where patients receive medical care in multiple health care systems may differ. The VA dedicates resources to support veteran population health management, which may not be available in other health care systems.11,12 These issues may pose a barrier to implementing a similar osteoporosis dashboard in non-VA facilities. In addition, it is significant that while the dashboard can be reconfigured and adapted to track veterans across different VA facilities, certain complexities arise if essential data, such as laboratory tests and DXA imaging, are conducted outside of VA facilities. In such cases, manual entry of this information into the dashboard would be necessary. Because the dashboard was quickly developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study lacked preimplementation data on laboratory testing, medication refills, and DXA imaging, which would have enabled a comparison of adherence before and after dashboard implementation. Finally, we acknowledge the delay in publishing these findings; however, we believe sharing innovative approaches to providing care for high-risk populations is essential, as demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

An osteoporosis clinic dashboard served as a valuable clinical support tool to ensure safe and effective osteoporosis medication delivery at VAPSHCS. Considering the growing utilization of osteoporosis medications, this dashboard plays a vital role in facilitating care coordination for patients receiving these high-risk treatments.18 Use of the dashboard supported the effective use of high-cost osteoporosis medications and is likely to improve clinical osteoporosis outcomes.

Despite the known fracture risk reduction, osteoporosis medication adherence is low.19,20 Maintaining consistent pharmacotherapy for osteoporosis is essential not only for fracture prevention but also reducing health care costs related to osteoporosis and preserving patient independence and functionality.21-24 While initially developed in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the dashboard remains useful. The VAPSHCS osteoporosis clinic is now staffed by 2 physicians (endocrine and rheumatology) and the dashboard is still in use. The RN coordinator spends about 15 minutes per week using the dashboard and managing the 67 veterans on osteoporosis therapy. This dashboard represents a sustainable clinical tool with the capacity to minimize osteoporosis care gaps and improve outcomes.

- Johnell O, Kanis J. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(suppl 2):S3-S7. doi:10.1007/s00198-004-1702-6

- van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001;29:517-522. doi:10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00614-7

- Dennison E, Cooper C. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Horm Res. 2000;54(suppl 1):58-63. doi:10.1159/000063449

- Cooper C. Epidemiology and public health impact of osteoporosis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1993;7:459-477. doi:10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80073-1

- Dolan P, Torgerson DJ. The cost of treating osteoporotic fractures in the United Kingdom female population. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:611-617. doi:10.1007/s001980050107

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465-475. doi:10.1359/jbmr.061113

- Palacios S. Medical treatment of osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2022;25:43-49. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1951697

- Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:1595-1622. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00221

- Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1802-1822. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3045

- Lau MK, Bounthavong M, Kay CL, Harvey MA, Christopher MLD. Clinical dashboard development and use for academic detailing in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(2S):S96-S103.e3. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2018.12.006

- Mould DR, D’Haens G, Upton RN. Clinical decision support tools: the evolution of a revolution. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:405-418. doi:10.1002/cpt.334

- Kizer KW, Fonseca ML, Long LM. The veterans healthcare system: preparing for the twenty-first century. Hosp Health Serv Adm. 1997;42:283-298.

- Park A, Gonzalez R, Chartier M, et al. Screening and treating hepatitis c in the VA: achieving excellence using lean and system redesign. Fed Pract. 2018;35:24-29.

- Brownell N, Kay C, Parra D, et al. Development and optimization of the Veterans Affairs’ national heart failure dashboard for population health management. J Card Fail. 2024;30:452-459. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.08.024

- Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the opioid safety initiative on opioidrelated prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158:833-839. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837

- Twohig PA, Rivington JR, Gunzler D, Daprano J, Margolius D. Clinician dashboard views and improvement in preventative health outcome measures: a retrospective analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:475. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4327-3

- Singh I, Fletcher R, Scanlon L, Tyler M, Aithal S. A quality improvement initiative on the management of osteoporosis in older people with Parkinsonism. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5:u210921.w5756. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u210921.w5756

- Anastasilakis AD, Makras P, Yavropoulou MP, Tabacco G, Naciu AM, Palermo A. Denosumab discontinuation and the rebound phenomenon: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2021;10:152. doi:10.3390/jcm10010152

- Sharman Moser S, Yu J, Goldshtein I, et al. Cost and consequences of nonadherence with oral bisphosphonate therapy: findings from a real-world data analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:262-269. doi:10.1177/1060028015626935

- Olsen KR, Hansen C, Abrahamsen B. Association between refill compliance to oral bisphosphonate treatment, incident fractures, and health care costs--an analysis using national health databases. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2639-2647. doi:10.1007/s00198-013-2365-y

- Blouin J, Dragomir A, Fredette M, Ste-Marie LG, Fernandes JC, Perreault S. Comparison of direct health care costs related to the pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis and to the management of osteoporotic fractures among compliant and noncompliant users of alendronate and risedronate: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1571-1581. doi:10.1007/s00198-008-0818-5

- Cotté F-E, De Pouvourville G. Cost of non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates in post-menopausal osteoporosis treatment in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:151. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-151

- Cho H, Byun J-H, Song I, et al. Effect of improved medication adherence on health care costs in osteoporosis patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11470. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011470

- Li N, Cornelissen D, Silverman S, et al. An updated systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of drugs for osteoporosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39:181-209. doi:10.1007/s40273-020-00965-9

- Johnell O, Kanis J. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(suppl 2):S3-S7. doi:10.1007/s00198-004-1702-6

- van Staa TP, Dennison EM, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Epidemiology of fractures in England and Wales. Bone. 2001;29:517-522. doi:10.1016/s8756-3282(01)00614-7

- Dennison E, Cooper C. Epidemiology of osteoporotic fractures. Horm Res. 2000;54(suppl 1):58-63. doi:10.1159/000063449

- Cooper C. Epidemiology and public health impact of osteoporosis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1993;7:459-477. doi:10.1016/s0950-3579(05)80073-1

- Dolan P, Torgerson DJ. The cost of treating osteoporotic fractures in the United Kingdom female population. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8:611-617. doi:10.1007/s001980050107

- Burge R, Dawson-Hughes B, Solomon DH, Wong JB, King A, Tosteson A. Incidence and economic burden of osteoporosis-related fractures in the United States, 2005-2025. J Bone Miner Res. 2007;22:465-475. doi:10.1359/jbmr.061113

- Palacios S. Medical treatment of osteoporosis. Climacteric. 2022;25:43-49. doi:10.1080/13697137.2021.1951697

- Eastell R, Rosen CJ, Black DM, Cheung AM, Murad MH, Shoback D. Pharmacological management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an Endocrine Society* clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:1595-1622. doi:10.1210/jc.2019-00221

- Watts NB, Adler RA, Bilezikian JP, et al. Osteoporosis in men: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:1802-1822. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3045

- Lau MK, Bounthavong M, Kay CL, Harvey MA, Christopher MLD. Clinical dashboard development and use for academic detailing in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(2S):S96-S103.e3. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2018.12.006

- Mould DR, D’Haens G, Upton RN. Clinical decision support tools: the evolution of a revolution. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016;99:405-418. doi:10.1002/cpt.334

- Kizer KW, Fonseca ML, Long LM. The veterans healthcare system: preparing for the twenty-first century. Hosp Health Serv Adm. 1997;42:283-298.

- Park A, Gonzalez R, Chartier M, et al. Screening and treating hepatitis c in the VA: achieving excellence using lean and system redesign. Fed Pract. 2018;35:24-29.

- Brownell N, Kay C, Parra D, et al. Development and optimization of the Veterans Affairs’ national heart failure dashboard for population health management. J Card Fail. 2024;30:452-459. doi:10.1016/j.cardfail.2023.08.024

- Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the opioid safety initiative on opioidrelated prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158:833-839. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837

- Twohig PA, Rivington JR, Gunzler D, Daprano J, Margolius D. Clinician dashboard views and improvement in preventative health outcome measures: a retrospective analysis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:475. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4327-3

- Singh I, Fletcher R, Scanlon L, Tyler M, Aithal S. A quality improvement initiative on the management of osteoporosis in older people with Parkinsonism. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5:u210921.w5756. doi:10.1136/bmjquality.u210921.w5756

- Anastasilakis AD, Makras P, Yavropoulou MP, Tabacco G, Naciu AM, Palermo A. Denosumab discontinuation and the rebound phenomenon: a narrative review. J Clin Med. 2021;10:152. doi:10.3390/jcm10010152

- Sharman Moser S, Yu J, Goldshtein I, et al. Cost and consequences of nonadherence with oral bisphosphonate therapy: findings from a real-world data analysis. Ann Pharmacother. 2016;50:262-269. doi:10.1177/1060028015626935

- Olsen KR, Hansen C, Abrahamsen B. Association between refill compliance to oral bisphosphonate treatment, incident fractures, and health care costs--an analysis using national health databases. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2639-2647. doi:10.1007/s00198-013-2365-y

- Blouin J, Dragomir A, Fredette M, Ste-Marie LG, Fernandes JC, Perreault S. Comparison of direct health care costs related to the pharmacological treatment of osteoporosis and to the management of osteoporotic fractures among compliant and noncompliant users of alendronate and risedronate: a population-based study. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1571-1581. doi:10.1007/s00198-008-0818-5

- Cotté F-E, De Pouvourville G. Cost of non-persistence with oral bisphosphonates in post-menopausal osteoporosis treatment in France. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:151. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-151

- Cho H, Byun J-H, Song I, et al. Effect of improved medication adherence on health care costs in osteoporosis patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11470. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011470

- Li N, Cornelissen D, Silverman S, et al. An updated systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of drugs for osteoporosis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39:181-209. doi:10.1007/s40273-020-00965-9

Improving High-Risk Osteoporosis Medication Adherence and Safety With an Automated Dashboard

Improving High-Risk Osteoporosis Medication Adherence and Safety With an Automated Dashboard