User login

Standardized attending rounds to improve the patient experience: A pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial

Patient experience has recently received heightened attention given evidence supporting an association between patient experience and quality of care,1 and the coupling of patient satisfaction to reimbursement rates for Medicare patients.2 Patient experience is often assessed through surveys of patient satisfaction, which correlates with patient perceptions of nurse and physician communication.3 Teaching hospitals introduce variables that may impact communication, including the involvement of multiple levels of care providers and competing patient care vs. educational priorities. Patients admitted to teaching services express decreased satisfaction with coordination and overall care compared with patients on nonteaching services.4

Clinical supervision of trainees on teaching services is primarily achieved through attending rounds (AR), where patients’ clinical presentations and management are discussed with an attending physician. Poor communication during AR may negatively affect the patient experience through inefficient care coordination among the inter-professional care team or through implementation of interventions without patients’ knowledge or input.5-11 Although patient engagement in rounds has been associated with higher patient satisfaction with rounds,12-19 AR and case presentations often occur at a distance from the patient’s bedside.20,21 Furthermore, AR vary in the time allotted per patient and the extent of participation of nurses and other allied health professionals. Standardized bedside rounding processes have been shown to improve efficiency, decrease daily resident work hours,22 and improve nurse-physician teamwork.23

Despite these benefits, recent prospective studies of bedside AR interventions have not improved patient satisfaction with rounds. One involved the implementation of interprofessional patient-centered bedside rounds on a nonteaching service,24 while the other evaluated the impact of integrating athletic principles into multidisciplinary work rounds.25 Work at our institution had sought to develop AR practice recommendations to foster an optimal patient experience, while maintaining provider workflow efficiency, facilitating interdisciplinary communication, and advancing trainee education.26 Using these AR recommendations, we conducted a prospective randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of implementing a standardized bedside AR model on patient satisfaction with rounds. We also assessed attending physician and trainee satisfaction with rounds, and perceived and actual AR duration.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

This trial was conducted on the internal medicine teaching service of the University of California San Francisco Medical Center from September 3, 2013 to November 27, 2013. The service is comprised of 8 teams, with a total average daily census of 80 to 90 patients. Teams are comprised of an attending physician, a senior resident (in the second or third year of residency training), 2 interns, and a third- and/or fourth-year medical student.

This trial, which was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research (UCSF CHR) and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01931553), was classified under Quality Improvement and did not require informed consent of patients or providers.

Intervention Description

We conducted a cluster randomized trial to evaluate the impact of a bundled set of 5 AR practice recommendations, adapted from published work,26 on patient experience, as well as on attending and trainee satisfaction: 1) huddling to establish the rounding schedule and priorities; 2) conducting bedside rounds; 3) integrating bedside nurses; 4) completing real-time order entry using bedside computers; 5) updating the whiteboard in each patient’s room with care plan information.

At the beginning of each month, study investigators (Nader Najafi and Bradley Monash) led a 1.5-hour workshop to train attending physicians and trainees allocated to the intervention arm on the recommended AR practices. Participants also received informational handouts to be referenced during AR. Attending physicians and trainees randomized to the control arm continued usual rounding practices. Control teams were notified that there would be observers on rounds but were not informed of the study aims.

Randomization and Team Assignments

The medicine service was divided into 2 arms, each comprised of 4 teams. Using a coin flip, Cluster 1 (Teams A, B, C and D) was randomized to the intervention, and Cluster 2 (Teams E, F, G and H) was randomized to the control. This design was pragmatically chosen to ensure that 1 team from each arm would admit patients daily. Allocation concealment of attending physicians and trainees was not possible given the nature of the intervention. Patients were blinded to study arm allocation.

MEASURES AND OUTCOMES

Adherence to Practice Recommendations

Thirty premedical students served as volunteer AR auditors. Each auditor received orientation and training in data collection techniques during a single 2-hour workshop. The auditors, blinded to study arm allocation, independently observed morning AR during weekdays and recorded the completion of the following elements as a dichotomous (yes/no) outcome: pre-rounds huddle, participation of nurse in AR, real-time order entry, and whiteboard use. They recorded the duration of AR per day for each team (minutes) and the rounding model for each patient rounding encounter during AR (bedside, hallway, or card flip).23 Bedside rounds were defined as presentation and discussion of the patient care plan in the presence of the patient. Hallway rounds were defined as presentation and discussion of the patient care plan partially outside the patient’s room and partially in the presence of the patient. Card-flip rounds were defined as presentation and discussion of the patient care plan entirely outside of the patient’s room without the team seeing the patient together. Two auditors simultaneously observed a random subset of patient-rounding encounters to evaluate inter-rater reliability, and the concordance between auditor observations was good (Pearson correlation = 0.66).27

Patient-Related Outcomes

The primary outcome was patient satisfaction with AR, assessed using a survey adapted from published work.12,14,28,29 Patients were approached to complete the questionnaire after they had experienced at least 1 AR. Patients were excluded if they were non-English-speaking, unavailable (eg, off the unit for testing or treatment), in isolation, or had impaired mental status. For patients admitted multiple times during the study period, only the first questionnaire was used. Survey questions included patient involvement in decision-making, quality of communication between patient and medicine team, and the perception that the medicine team cared about the patient. Patients were asked to state their level of agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale. We obtained data on patient demographics from administrative datasets.

Healthcare Provider Outcomes

Attending physicians and trainees on service for at least 7 consecutive days were sent an electronic survey, adapted from published work.25,30 Questions assessed satisfaction with AR, perceived value of bedside rounds, and extent of patient and nursing involvement.Level of agreement with each item was captured on a continuous scale; 0 = strongly disagree to 100 = strongly agree, or from 0 (far too little) to 100 (far too much), with 50 equating to “about right.” Attending physicians and trainees were also asked to estimate the average duration of AR (in minutes).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were blinded to study arm allocation and followed intention-to-treat principles. One attending physician crossed over from intervention to control arm; patient surveys associated with this attending (n = 4) were excluded to avoid contamination. No trainees crossed over.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who completed the survey are reported (Appendix). To compare patient satisfaction scores, we used a random-effects regression model to account for correlation among responses within teams within randomized clusters, defining teams by attending physician. As this correlation was negligible and not statistically significant, we did not adjust ordinary linear regression models for clustering. Given observed differences in patient characteristics, we adjusted for a number of covariates (eg, age, gender, insurance payer, race, marital status, trial group arm).

We conducted simple linear regression for attending and trainee satisfaction comparisons between arms, adjusting only for trainee type (eg, resident, intern, and medical student).

We compared the frequency with which intervention and control teams adhered to the 5 recommended AR practices using chi-square tests. We used independent Student’s t tests to compare total duration of AR by teams within each arm, as well as mean time spent per patient.

This trial had a fixed number of arms (n = 2), each of fixed size (n = 600), based on the average monthly inpatient census on the medicine service. This fixed sample size, with 80% power and α = 0.05, will be able to detect a 0.16 difference in patient satisfaction scores between groups.

All analyses were conducted using SAS® v 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

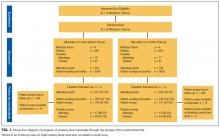

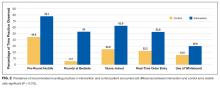

We observed 241 AR involving 1855 patient rounding encounters in the intervention arm and 264 AR involving 1903 patient rounding encounters in the control arm (response rates shown in Figure 1).

Patient Satisfaction and Clinical Outcomes

Five hundred ninety-five patients were allocated to the intervention arm and 605 were allocated to the control arm (Figure 1). Mean age, gender, race, marital status, primary language, and insurance provider did not differ between intervention and control arms (Table 1).

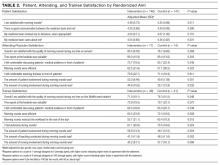

Patients in the intervention arm reported significantly higher satisfaction with AR and felt more cared for by their medicine team (Table 2).

Actual and Perceived Duration of Attending Rounds

The intervention shortened the total duration of AR by 8 minutes on average (143 vs. 151 minutes, P = 0.052) and the time spent per patient by 4 minutes on average (19 vs. 23 minutes, P < 0.001). Despite this, trainees in the intervention arm perceived AR to last longer (mean estimated time: 167 min vs. 152 min, P < 0.001).

Healthcare Provider Outcomes

We observed 79 attending physicians and trainees in the intervention arm and 78 in the control arm, with survey response rates shown in Figure 1. Attending physicians in the intervention and the control arms reported high levels of satisfaction with the quality of AR (Table 2). Attending physicians in the intervention arm were more likely to report an appropriate level of patient involvement and nurse involvement.

Although trainees in the intervention and control arms reported high levels of satisfaction with the quality of AR, trainees in the intervention arm reported lower satisfaction with AR compared with control arm trainees (Table 2). Trainees in the intervention arm reported that AR involved less autonomy, efficiency, and teaching. Trainees in the intervention arm also scored patient involvement more towards the “far too much” end of the scale compared with “about right” in the control arm. However, trainees in the intervention arm perceived nurse involvement closer to “about right,” as opposed to “far too little” in the control arm.

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

Training internal medicine teams to adhere to 5 recommended AR practices increased patient satisfaction with AR and the perception that patients were more cared for by their medicine team. Despite the intervention potentially shortening the duration of AR, attending physicians and trainees perceived AR to last longer, and trainee satisfaction with AR decreased.

Teams in the intervention arm adhered to all recommended rounding practices at higher rates than the control teams. Although intervention teams rounded at the bedside 53% of the time, they were encouraged to bedside round only on patients who desired to participate in rounds, were not altered, and for whom the clinical discussion was not too sensitive to occur at the bedside. Of the recommended rounding behaviors, the lowest adherence was seen with whiteboard use.

A major component of the intervention was to move the clinical presentation to the patient’s bedside. Most patients prefer being included in rounds and partaking in trainee education.12-19,28,29,31-33 Patients may also perceive that more time is spent with them during bedside case presentations,14,28 and exposure to providers conferring on their care may enhance patient confidence in the care being delivered.12 Although a recent study of patient-centered bedside rounding on a nonteaching service did not result in increased patient satisfaction,24 teaching services may offer more opportunities for improvement in care coordination and communication.4

Other aspects of the intervention may have contributed to increased patient satisfaction with AR. The pre-rounds huddle may have helped teams prioritize which patients required more time or would benefit most from bedside rounds. The involvement of nurses in AR may have bolstered communication and team dynamics, enhancing the patient’s perception of interprofessional collaboration. Real-time order entry might have led to more efficient implementation of the care plan, and whiteboard use may have helped to keep patients abreast of the care plan.

Patients in the intervention arm felt more cared for by their medicine teams but did not report improvements in communication or in shared decision-making. Prior work highlights that limited patient engagement, activation, and shared decision-making may occur during AR.24,34 Patient-physician communication during AR is challenged by time pressures and competing priorities, including the “need” for trainees to demonstrate their medical knowledge and clinical skills. Efforts that encourage bedside rounding should include communication training with respect to patient engagement and shared decision-making.

Attending physicians reported positive attitudes toward bedside rounding, consistent with prior studies.13,21,31 However, trainees in the intervention arm expressed decreased satisfaction with AR, estimating that AR took longer and reporting too much patient involvement. Prior studies reflect similar bedside-rounding concerns, including perceived workflow inefficiencies, infringement on teaching opportunities, and time constraints.12,20,35 Trainees are under intense time pressures to complete their work, attend educational conferences, and leave the hospital to attend afternoon clinic or to comply with duty-hour restrictions. Trainees value succinctness,12,35,36 so the perception that intervention AR lasted longer likely contributed to trainee dissatisfaction.

Reduced trainee satisfaction with intervention AR may have also stemmed from the perception of decreased autonomy and less teaching, both valued by trainees.20,35,36 The intervention itself reduced trainee autonomy because usual practice at our hospital involves residents deciding where and how to round. Attending physician presence at the bedside during rounds may have further infringed on trainee autonomy if the patient looked to the attending for answers, or if the attending was seen as the AR leader. Attending physicians may mitigate the risk of compromising trainee autonomy by allowing the trainee to speak first, ensuring the trainee is positioned closer to, and at eye level with, the patient, and redirecting patient questions to the trainee as appropriate. Optimizing trainee experience with bedside AR requires preparation and training of attending physicians, who may feel inadequately prepared to lead bedside rounds and conduct bedside teaching.37 Faculty must learn how to preserve team efficiency, create a safe, nonpunitive bedside environment that fosters the trainee-patient relationship, and ensure rounds remain educational.36,38,39

The intervention reduced the average time spent on AR and time spent per patient. Studies examining the relationship between bedside rounding and duration of rounds have yielded mixed results: some have demonstrated no effect of bedside rounds on rounding time,28,40 while others report longer rounding times.37 The pre-rounds huddle and real-time order writing may have enhanced workflow efficiency.

Our study has several limitations. These results reflect the experience of a single large academic medical center and may not be generalizable to other settings. Although overall patient response to the survey was low and may not be representative of the entire patient population, response rates in the intervention and control arms were equivalent. Non-English speaking patients may have preferences that were not reflected in our survey results, and we did not otherwise quantify individual reasons for survey noncompletion. The presence of auditors on AR may have introduced observer bias. There may have been crossover effect; however, observed prevalence of individual practices remained low in the control arm. The 1.5-hour workshop may have inadequately equipped trainees with the complex skills required to lead and participate in bedside rounding, and more training, experience, and feedback may have yielded different results. For instance, residents with more exposure to bedside rounding express greater appreciation of its role in education and patient care.20 While adherence to some of the recommended practices remained low, we did not employ a full range of change-management techniques. Instead, we opted for a “low intensity” intervention (eg, single workshop, handouts) that relied on voluntary adoption by medicine teams and that we hoped other institutions could reproduce. Finally, we did not assess the relative impact of individual rounding behaviors on the measured outcomes.

In conclusion, training medicine teams to adhere to a standardized bedside AR model increased patient satisfaction with rounds. Concomitant trainee dissatisfaction may require further experience and training of attending physicians and trainees to ensure successful adoption.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients, providers, and trainees who participated in this study. We would also like to acknowledge the following volunteer auditors who observed teams daily: Arianna Abundo, Elahhe Afkhamnejad, Yolanda Banuelos, Laila Fozoun, Soe Yupar Khin, Tam Thien Le, Wing Sum Li, Yaqiao Li, Mengyao Liu, Tzyy-Harn Lo, Shynh-Herng Lo, David Lowe, Danoush Paborji, Sa Nan Park, Urmila Powale, Redha Fouad Qabazard, Monique Quiroz, John-Luke Marcelo Rivera, Manfred Roy Luna Salvador, Tobias Gowen Squier-Roper, Flora Yan Ting, Francesca Natasha T. Tizon, Emily Claire Trautner, Stephen Weiner, Alice Wilson, Kimberly Woo, Bingling J Wu, Johnny Wu, Brenda Yee. Statistical expertise was provided by Joan Hilton from the UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI), which is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Thanks also to Oralia Schatzman, Andrea Mazzini, and Erika Huie for their administrative support, and John Hillman for data-related support. Special thanks to Kirsten Kangelaris and Andrew Auerbach for their valuable feedback throughout, and to Maria Novelero and Robert Wachter for their divisional support of this project.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

1. Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):1-18. PubMed

2. Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) Fact Sheet. August 2013. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Baltimore, MD.http://www.hcahpsonline.org/files/August_2013_HCAHPS_Fact_Sheet3.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2015.

3. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:41-48. PubMed

4. Wray CM, Flores A, Padula WV, Prochaska MT, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. Measuring patient experiences on hospitalist and teaching services: Patient responses to a 30-day postdischarge questionnaire. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):99-104. PubMed

5. Bharwani AM, Harris GC, Southwick FS. Perspective: A business school view of medical interprofessional rounds: transforming rounding groups into rounding teams. Acad Med. 2012;87(12):1768-1771. PubMed

6. Chand DV. Observational study using the tools of lean six sigma to improve the efficiency of the resident rounding process. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):144-150. PubMed

7. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. PubMed

8. Weber H, Stöckli M, Nübling M, Langewitz WA. Communication during ward rounds in internal medicine. An analysis of patient-nurse-physician interactions using RIAS. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):343-348. PubMed

9. McMahon GT, Katz JT, Thorndike ME, Levy BD, Loscalzo J. Evaluation of a redesign initiative in an internal-medicine residency. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1304-1311. PubMed

10. Amoss J. Attending rounds: where do we go from here?: comment on “Attending rounds in the current era”. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1089-1090. PubMed

11. Curley C, McEachern JE, Speroff T. A firm trial of interdisciplinary rounds on the inpatient medical wards: an intervention designed using continuous quality improvement. Med Care. 1998;36(suppl 8):AS4-A12. PubMed

12. Wang-Cheng RM, Barnas GP, Sigmann P, Riendl PA, Young MJ. Bedside case presentations: why patients like them but learners don’t. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(4):284-287. PubMed

13. Chauke, HL, Pattinson RC. Ward rounds—bedside or conference room? S Afr Med J. 2006;96(5):398-400. PubMed

14. Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, Roter D, Dobs AS. The effect of bedside case presentations on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):336, 1150-1155. PubMed

15. Simons RJ, Baily RG, Zelis R, Zwillich CW. The physiologic and psychological effects of the bedside presentation. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(18):1273-1275. PubMed

16. Wise TN, Feldheim D, Mann LS, Boyle E, Rustgi VK. Patients’ reactions to house staff work rounds. Psychosomatics. 1985;26(8):669-672. PubMed

17. Linfors EW, Neelon FA. Sounding Boards. The case of bedside rounds. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(21):1230-1233. PubMed

18. Nair BR, Coughlan JL, Hensley MJ. Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching. Med Educ. 1997;31(5):341-346. PubMed

19. Romano J. Patients’ attitudes and behavior in ward round teaching. JAMA. 1941;117(9):664-667.

20. Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105-110. PubMed

21. Shoeb M, Khanna R, Fang M, et al. Internal medicine rounding practices and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):239-243. PubMed

22. Calderon AS, Blackmore CC, Williams BL, et al. Transforming ward rounds through rounding-in-flow. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):750-755. PubMed

23. Henkin S, Chon TY, Christopherson ML, Halvorsen AJ, Worden LM, Ratelle JT. Improving nurse-physician teamwork through interprofessional bedside rounding. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:201-205. PubMed

24. O’Leary KJ, Killarney A, Hansen LO, et al. Effect of patient-centred bedside rounds on hospitalised patients’ decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:921-928. PubMed

25. Southwick F, Lewis M, Treloar D, et al. Applying athletic principles to medical rounds to improve teaching and patient care. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1018-1023. PubMed

26. Najafi N, Monash B, Mourad M, et al. Improving attending rounds: Qualitative reflections from multidisciplinary providers. Hosp Pract (1995). 2015;43(3):186-190. PubMed

27. Altman DG. Practical Statistics For Medical Research. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2006.

28. Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Huang G, Smith C. The return of bedside rounds: an educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):792-798. PubMed

29. Fletcher KE, Rankey DS, Stern DT. Bedside interactions from the other side of the bedrail. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(1):58-61. PubMed

30. Gatorounds: Applying Championship Athletic Principles to Healthcare. University of Florida Health. http://gatorounds.med.ufl.edu/surveys/. Accessed March 1, 2013.

31. Gonzalo JD, Heist BS, Duffy BL, et al. The value of bedside rounds: a multicenter qualitative study. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):326-333. PubMed

32. Rogers HD, Carline JD, Paauw DS. Examination room presentations in general internal medicine clinic: patients’ and students’ perceptions. Acad Med. 2003;78(9):945-949. PubMed

33. Fletcher KE, Furney SL, Stern DT. Patients speak: what’s really important about bedside interactions with physician teams. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(2):120-127. PubMed

34. Satterfield JM, Bereknyei S, Hilton JF, et al. The prevalence of social and behavioral topics and related educational opportunities during attending rounds. Acad Med. 2014; 89(11):1548-1557. PubMed

35. Kroenke K, Simmons JO, Copley JB, Smith C. Attending rounds: a survey of physician attitudes. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5(3):229-233. PubMed

36. Castiglioni A, Shewchuk RM, Willett LL, Heudebert GR, Centor RM. A pilot study using nominal group technique to assess residents’ perceptions of successful attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1060-1065. PubMed

37. Crumlish CM, Yialamas MA, McMahon GT. Quantification of bedside teaching by an academic hospitalist group. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(5):304-307. PubMed

38. Gonzalo JD, Wolpaw DR, Lehman E, Chuang CH. Patient-centered interprofessional collaborative care: factors associated with bedside interprofessional rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1040-1047. PubMed

39. Roy B, Castiglioni A, Kraemer RR, et al. Using cognitive mapping to define key domains for successful attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1492-1498. PubMed

40. Bhansali P, Birch S, Campbell JK, et al. A time-motion study of inpatient rounds using a family-centered rounds model. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(1):31-38. PubMed

Patient experience has recently received heightened attention given evidence supporting an association between patient experience and quality of care,1 and the coupling of patient satisfaction to reimbursement rates for Medicare patients.2 Patient experience is often assessed through surveys of patient satisfaction, which correlates with patient perceptions of nurse and physician communication.3 Teaching hospitals introduce variables that may impact communication, including the involvement of multiple levels of care providers and competing patient care vs. educational priorities. Patients admitted to teaching services express decreased satisfaction with coordination and overall care compared with patients on nonteaching services.4

Clinical supervision of trainees on teaching services is primarily achieved through attending rounds (AR), where patients’ clinical presentations and management are discussed with an attending physician. Poor communication during AR may negatively affect the patient experience through inefficient care coordination among the inter-professional care team or through implementation of interventions without patients’ knowledge or input.5-11 Although patient engagement in rounds has been associated with higher patient satisfaction with rounds,12-19 AR and case presentations often occur at a distance from the patient’s bedside.20,21 Furthermore, AR vary in the time allotted per patient and the extent of participation of nurses and other allied health professionals. Standardized bedside rounding processes have been shown to improve efficiency, decrease daily resident work hours,22 and improve nurse-physician teamwork.23

Despite these benefits, recent prospective studies of bedside AR interventions have not improved patient satisfaction with rounds. One involved the implementation of interprofessional patient-centered bedside rounds on a nonteaching service,24 while the other evaluated the impact of integrating athletic principles into multidisciplinary work rounds.25 Work at our institution had sought to develop AR practice recommendations to foster an optimal patient experience, while maintaining provider workflow efficiency, facilitating interdisciplinary communication, and advancing trainee education.26 Using these AR recommendations, we conducted a prospective randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of implementing a standardized bedside AR model on patient satisfaction with rounds. We also assessed attending physician and trainee satisfaction with rounds, and perceived and actual AR duration.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

This trial was conducted on the internal medicine teaching service of the University of California San Francisco Medical Center from September 3, 2013 to November 27, 2013. The service is comprised of 8 teams, with a total average daily census of 80 to 90 patients. Teams are comprised of an attending physician, a senior resident (in the second or third year of residency training), 2 interns, and a third- and/or fourth-year medical student.

This trial, which was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research (UCSF CHR) and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01931553), was classified under Quality Improvement and did not require informed consent of patients or providers.

Intervention Description

We conducted a cluster randomized trial to evaluate the impact of a bundled set of 5 AR practice recommendations, adapted from published work,26 on patient experience, as well as on attending and trainee satisfaction: 1) huddling to establish the rounding schedule and priorities; 2) conducting bedside rounds; 3) integrating bedside nurses; 4) completing real-time order entry using bedside computers; 5) updating the whiteboard in each patient’s room with care plan information.

At the beginning of each month, study investigators (Nader Najafi and Bradley Monash) led a 1.5-hour workshop to train attending physicians and trainees allocated to the intervention arm on the recommended AR practices. Participants also received informational handouts to be referenced during AR. Attending physicians and trainees randomized to the control arm continued usual rounding practices. Control teams were notified that there would be observers on rounds but were not informed of the study aims.

Randomization and Team Assignments

The medicine service was divided into 2 arms, each comprised of 4 teams. Using a coin flip, Cluster 1 (Teams A, B, C and D) was randomized to the intervention, and Cluster 2 (Teams E, F, G and H) was randomized to the control. This design was pragmatically chosen to ensure that 1 team from each arm would admit patients daily. Allocation concealment of attending physicians and trainees was not possible given the nature of the intervention. Patients were blinded to study arm allocation.

MEASURES AND OUTCOMES

Adherence to Practice Recommendations

Thirty premedical students served as volunteer AR auditors. Each auditor received orientation and training in data collection techniques during a single 2-hour workshop. The auditors, blinded to study arm allocation, independently observed morning AR during weekdays and recorded the completion of the following elements as a dichotomous (yes/no) outcome: pre-rounds huddle, participation of nurse in AR, real-time order entry, and whiteboard use. They recorded the duration of AR per day for each team (minutes) and the rounding model for each patient rounding encounter during AR (bedside, hallway, or card flip).23 Bedside rounds were defined as presentation and discussion of the patient care plan in the presence of the patient. Hallway rounds were defined as presentation and discussion of the patient care plan partially outside the patient’s room and partially in the presence of the patient. Card-flip rounds were defined as presentation and discussion of the patient care plan entirely outside of the patient’s room without the team seeing the patient together. Two auditors simultaneously observed a random subset of patient-rounding encounters to evaluate inter-rater reliability, and the concordance between auditor observations was good (Pearson correlation = 0.66).27

Patient-Related Outcomes

The primary outcome was patient satisfaction with AR, assessed using a survey adapted from published work.12,14,28,29 Patients were approached to complete the questionnaire after they had experienced at least 1 AR. Patients were excluded if they were non-English-speaking, unavailable (eg, off the unit for testing or treatment), in isolation, or had impaired mental status. For patients admitted multiple times during the study period, only the first questionnaire was used. Survey questions included patient involvement in decision-making, quality of communication between patient and medicine team, and the perception that the medicine team cared about the patient. Patients were asked to state their level of agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale. We obtained data on patient demographics from administrative datasets.

Healthcare Provider Outcomes

Attending physicians and trainees on service for at least 7 consecutive days were sent an electronic survey, adapted from published work.25,30 Questions assessed satisfaction with AR, perceived value of bedside rounds, and extent of patient and nursing involvement.Level of agreement with each item was captured on a continuous scale; 0 = strongly disagree to 100 = strongly agree, or from 0 (far too little) to 100 (far too much), with 50 equating to “about right.” Attending physicians and trainees were also asked to estimate the average duration of AR (in minutes).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were blinded to study arm allocation and followed intention-to-treat principles. One attending physician crossed over from intervention to control arm; patient surveys associated with this attending (n = 4) were excluded to avoid contamination. No trainees crossed over.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who completed the survey are reported (Appendix). To compare patient satisfaction scores, we used a random-effects regression model to account for correlation among responses within teams within randomized clusters, defining teams by attending physician. As this correlation was negligible and not statistically significant, we did not adjust ordinary linear regression models for clustering. Given observed differences in patient characteristics, we adjusted for a number of covariates (eg, age, gender, insurance payer, race, marital status, trial group arm).

We conducted simple linear regression for attending and trainee satisfaction comparisons between arms, adjusting only for trainee type (eg, resident, intern, and medical student).

We compared the frequency with which intervention and control teams adhered to the 5 recommended AR practices using chi-square tests. We used independent Student’s t tests to compare total duration of AR by teams within each arm, as well as mean time spent per patient.

This trial had a fixed number of arms (n = 2), each of fixed size (n = 600), based on the average monthly inpatient census on the medicine service. This fixed sample size, with 80% power and α = 0.05, will be able to detect a 0.16 difference in patient satisfaction scores between groups.

All analyses were conducted using SAS® v 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

We observed 241 AR involving 1855 patient rounding encounters in the intervention arm and 264 AR involving 1903 patient rounding encounters in the control arm (response rates shown in Figure 1).

Patient Satisfaction and Clinical Outcomes

Five hundred ninety-five patients were allocated to the intervention arm and 605 were allocated to the control arm (Figure 1). Mean age, gender, race, marital status, primary language, and insurance provider did not differ between intervention and control arms (Table 1).

Patients in the intervention arm reported significantly higher satisfaction with AR and felt more cared for by their medicine team (Table 2).

Actual and Perceived Duration of Attending Rounds

The intervention shortened the total duration of AR by 8 minutes on average (143 vs. 151 minutes, P = 0.052) and the time spent per patient by 4 minutes on average (19 vs. 23 minutes, P < 0.001). Despite this, trainees in the intervention arm perceived AR to last longer (mean estimated time: 167 min vs. 152 min, P < 0.001).

Healthcare Provider Outcomes

We observed 79 attending physicians and trainees in the intervention arm and 78 in the control arm, with survey response rates shown in Figure 1. Attending physicians in the intervention and the control arms reported high levels of satisfaction with the quality of AR (Table 2). Attending physicians in the intervention arm were more likely to report an appropriate level of patient involvement and nurse involvement.

Although trainees in the intervention and control arms reported high levels of satisfaction with the quality of AR, trainees in the intervention arm reported lower satisfaction with AR compared with control arm trainees (Table 2). Trainees in the intervention arm reported that AR involved less autonomy, efficiency, and teaching. Trainees in the intervention arm also scored patient involvement more towards the “far too much” end of the scale compared with “about right” in the control arm. However, trainees in the intervention arm perceived nurse involvement closer to “about right,” as opposed to “far too little” in the control arm.

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

Training internal medicine teams to adhere to 5 recommended AR practices increased patient satisfaction with AR and the perception that patients were more cared for by their medicine team. Despite the intervention potentially shortening the duration of AR, attending physicians and trainees perceived AR to last longer, and trainee satisfaction with AR decreased.

Teams in the intervention arm adhered to all recommended rounding practices at higher rates than the control teams. Although intervention teams rounded at the bedside 53% of the time, they were encouraged to bedside round only on patients who desired to participate in rounds, were not altered, and for whom the clinical discussion was not too sensitive to occur at the bedside. Of the recommended rounding behaviors, the lowest adherence was seen with whiteboard use.

A major component of the intervention was to move the clinical presentation to the patient’s bedside. Most patients prefer being included in rounds and partaking in trainee education.12-19,28,29,31-33 Patients may also perceive that more time is spent with them during bedside case presentations,14,28 and exposure to providers conferring on their care may enhance patient confidence in the care being delivered.12 Although a recent study of patient-centered bedside rounding on a nonteaching service did not result in increased patient satisfaction,24 teaching services may offer more opportunities for improvement in care coordination and communication.4

Other aspects of the intervention may have contributed to increased patient satisfaction with AR. The pre-rounds huddle may have helped teams prioritize which patients required more time or would benefit most from bedside rounds. The involvement of nurses in AR may have bolstered communication and team dynamics, enhancing the patient’s perception of interprofessional collaboration. Real-time order entry might have led to more efficient implementation of the care plan, and whiteboard use may have helped to keep patients abreast of the care plan.

Patients in the intervention arm felt more cared for by their medicine teams but did not report improvements in communication or in shared decision-making. Prior work highlights that limited patient engagement, activation, and shared decision-making may occur during AR.24,34 Patient-physician communication during AR is challenged by time pressures and competing priorities, including the “need” for trainees to demonstrate their medical knowledge and clinical skills. Efforts that encourage bedside rounding should include communication training with respect to patient engagement and shared decision-making.

Attending physicians reported positive attitudes toward bedside rounding, consistent with prior studies.13,21,31 However, trainees in the intervention arm expressed decreased satisfaction with AR, estimating that AR took longer and reporting too much patient involvement. Prior studies reflect similar bedside-rounding concerns, including perceived workflow inefficiencies, infringement on teaching opportunities, and time constraints.12,20,35 Trainees are under intense time pressures to complete their work, attend educational conferences, and leave the hospital to attend afternoon clinic or to comply with duty-hour restrictions. Trainees value succinctness,12,35,36 so the perception that intervention AR lasted longer likely contributed to trainee dissatisfaction.

Reduced trainee satisfaction with intervention AR may have also stemmed from the perception of decreased autonomy and less teaching, both valued by trainees.20,35,36 The intervention itself reduced trainee autonomy because usual practice at our hospital involves residents deciding where and how to round. Attending physician presence at the bedside during rounds may have further infringed on trainee autonomy if the patient looked to the attending for answers, or if the attending was seen as the AR leader. Attending physicians may mitigate the risk of compromising trainee autonomy by allowing the trainee to speak first, ensuring the trainee is positioned closer to, and at eye level with, the patient, and redirecting patient questions to the trainee as appropriate. Optimizing trainee experience with bedside AR requires preparation and training of attending physicians, who may feel inadequately prepared to lead bedside rounds and conduct bedside teaching.37 Faculty must learn how to preserve team efficiency, create a safe, nonpunitive bedside environment that fosters the trainee-patient relationship, and ensure rounds remain educational.36,38,39

The intervention reduced the average time spent on AR and time spent per patient. Studies examining the relationship between bedside rounding and duration of rounds have yielded mixed results: some have demonstrated no effect of bedside rounds on rounding time,28,40 while others report longer rounding times.37 The pre-rounds huddle and real-time order writing may have enhanced workflow efficiency.

Our study has several limitations. These results reflect the experience of a single large academic medical center and may not be generalizable to other settings. Although overall patient response to the survey was low and may not be representative of the entire patient population, response rates in the intervention and control arms were equivalent. Non-English speaking patients may have preferences that were not reflected in our survey results, and we did not otherwise quantify individual reasons for survey noncompletion. The presence of auditors on AR may have introduced observer bias. There may have been crossover effect; however, observed prevalence of individual practices remained low in the control arm. The 1.5-hour workshop may have inadequately equipped trainees with the complex skills required to lead and participate in bedside rounding, and more training, experience, and feedback may have yielded different results. For instance, residents with more exposure to bedside rounding express greater appreciation of its role in education and patient care.20 While adherence to some of the recommended practices remained low, we did not employ a full range of change-management techniques. Instead, we opted for a “low intensity” intervention (eg, single workshop, handouts) that relied on voluntary adoption by medicine teams and that we hoped other institutions could reproduce. Finally, we did not assess the relative impact of individual rounding behaviors on the measured outcomes.

In conclusion, training medicine teams to adhere to a standardized bedside AR model increased patient satisfaction with rounds. Concomitant trainee dissatisfaction may require further experience and training of attending physicians and trainees to ensure successful adoption.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients, providers, and trainees who participated in this study. We would also like to acknowledge the following volunteer auditors who observed teams daily: Arianna Abundo, Elahhe Afkhamnejad, Yolanda Banuelos, Laila Fozoun, Soe Yupar Khin, Tam Thien Le, Wing Sum Li, Yaqiao Li, Mengyao Liu, Tzyy-Harn Lo, Shynh-Herng Lo, David Lowe, Danoush Paborji, Sa Nan Park, Urmila Powale, Redha Fouad Qabazard, Monique Quiroz, John-Luke Marcelo Rivera, Manfred Roy Luna Salvador, Tobias Gowen Squier-Roper, Flora Yan Ting, Francesca Natasha T. Tizon, Emily Claire Trautner, Stephen Weiner, Alice Wilson, Kimberly Woo, Bingling J Wu, Johnny Wu, Brenda Yee. Statistical expertise was provided by Joan Hilton from the UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI), which is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Thanks also to Oralia Schatzman, Andrea Mazzini, and Erika Huie for their administrative support, and John Hillman for data-related support. Special thanks to Kirsten Kangelaris and Andrew Auerbach for their valuable feedback throughout, and to Maria Novelero and Robert Wachter for their divisional support of this project.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

Patient experience has recently received heightened attention given evidence supporting an association between patient experience and quality of care,1 and the coupling of patient satisfaction to reimbursement rates for Medicare patients.2 Patient experience is often assessed through surveys of patient satisfaction, which correlates with patient perceptions of nurse and physician communication.3 Teaching hospitals introduce variables that may impact communication, including the involvement of multiple levels of care providers and competing patient care vs. educational priorities. Patients admitted to teaching services express decreased satisfaction with coordination and overall care compared with patients on nonteaching services.4

Clinical supervision of trainees on teaching services is primarily achieved through attending rounds (AR), where patients’ clinical presentations and management are discussed with an attending physician. Poor communication during AR may negatively affect the patient experience through inefficient care coordination among the inter-professional care team or through implementation of interventions without patients’ knowledge or input.5-11 Although patient engagement in rounds has been associated with higher patient satisfaction with rounds,12-19 AR and case presentations often occur at a distance from the patient’s bedside.20,21 Furthermore, AR vary in the time allotted per patient and the extent of participation of nurses and other allied health professionals. Standardized bedside rounding processes have been shown to improve efficiency, decrease daily resident work hours,22 and improve nurse-physician teamwork.23

Despite these benefits, recent prospective studies of bedside AR interventions have not improved patient satisfaction with rounds. One involved the implementation of interprofessional patient-centered bedside rounds on a nonteaching service,24 while the other evaluated the impact of integrating athletic principles into multidisciplinary work rounds.25 Work at our institution had sought to develop AR practice recommendations to foster an optimal patient experience, while maintaining provider workflow efficiency, facilitating interdisciplinary communication, and advancing trainee education.26 Using these AR recommendations, we conducted a prospective randomized controlled trial to evaluate the impact of implementing a standardized bedside AR model on patient satisfaction with rounds. We also assessed attending physician and trainee satisfaction with rounds, and perceived and actual AR duration.

METHODS

Setting and Participants

This trial was conducted on the internal medicine teaching service of the University of California San Francisco Medical Center from September 3, 2013 to November 27, 2013. The service is comprised of 8 teams, with a total average daily census of 80 to 90 patients. Teams are comprised of an attending physician, a senior resident (in the second or third year of residency training), 2 interns, and a third- and/or fourth-year medical student.

This trial, which was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Committee on Human Research (UCSF CHR) and was registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01931553), was classified under Quality Improvement and did not require informed consent of patients or providers.

Intervention Description

We conducted a cluster randomized trial to evaluate the impact of a bundled set of 5 AR practice recommendations, adapted from published work,26 on patient experience, as well as on attending and trainee satisfaction: 1) huddling to establish the rounding schedule and priorities; 2) conducting bedside rounds; 3) integrating bedside nurses; 4) completing real-time order entry using bedside computers; 5) updating the whiteboard in each patient’s room with care plan information.

At the beginning of each month, study investigators (Nader Najafi and Bradley Monash) led a 1.5-hour workshop to train attending physicians and trainees allocated to the intervention arm on the recommended AR practices. Participants also received informational handouts to be referenced during AR. Attending physicians and trainees randomized to the control arm continued usual rounding practices. Control teams were notified that there would be observers on rounds but were not informed of the study aims.

Randomization and Team Assignments

The medicine service was divided into 2 arms, each comprised of 4 teams. Using a coin flip, Cluster 1 (Teams A, B, C and D) was randomized to the intervention, and Cluster 2 (Teams E, F, G and H) was randomized to the control. This design was pragmatically chosen to ensure that 1 team from each arm would admit patients daily. Allocation concealment of attending physicians and trainees was not possible given the nature of the intervention. Patients were blinded to study arm allocation.

MEASURES AND OUTCOMES

Adherence to Practice Recommendations

Thirty premedical students served as volunteer AR auditors. Each auditor received orientation and training in data collection techniques during a single 2-hour workshop. The auditors, blinded to study arm allocation, independently observed morning AR during weekdays and recorded the completion of the following elements as a dichotomous (yes/no) outcome: pre-rounds huddle, participation of nurse in AR, real-time order entry, and whiteboard use. They recorded the duration of AR per day for each team (minutes) and the rounding model for each patient rounding encounter during AR (bedside, hallway, or card flip).23 Bedside rounds were defined as presentation and discussion of the patient care plan in the presence of the patient. Hallway rounds were defined as presentation and discussion of the patient care plan partially outside the patient’s room and partially in the presence of the patient. Card-flip rounds were defined as presentation and discussion of the patient care plan entirely outside of the patient’s room without the team seeing the patient together. Two auditors simultaneously observed a random subset of patient-rounding encounters to evaluate inter-rater reliability, and the concordance between auditor observations was good (Pearson correlation = 0.66).27

Patient-Related Outcomes

The primary outcome was patient satisfaction with AR, assessed using a survey adapted from published work.12,14,28,29 Patients were approached to complete the questionnaire after they had experienced at least 1 AR. Patients were excluded if they were non-English-speaking, unavailable (eg, off the unit for testing or treatment), in isolation, or had impaired mental status. For patients admitted multiple times during the study period, only the first questionnaire was used. Survey questions included patient involvement in decision-making, quality of communication between patient and medicine team, and the perception that the medicine team cared about the patient. Patients were asked to state their level of agreement with each item on a 5-point Likert scale. We obtained data on patient demographics from administrative datasets.

Healthcare Provider Outcomes

Attending physicians and trainees on service for at least 7 consecutive days were sent an electronic survey, adapted from published work.25,30 Questions assessed satisfaction with AR, perceived value of bedside rounds, and extent of patient and nursing involvement.Level of agreement with each item was captured on a continuous scale; 0 = strongly disagree to 100 = strongly agree, or from 0 (far too little) to 100 (far too much), with 50 equating to “about right.” Attending physicians and trainees were also asked to estimate the average duration of AR (in minutes).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were blinded to study arm allocation and followed intention-to-treat principles. One attending physician crossed over from intervention to control arm; patient surveys associated with this attending (n = 4) were excluded to avoid contamination. No trainees crossed over.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients who completed the survey are reported (Appendix). To compare patient satisfaction scores, we used a random-effects regression model to account for correlation among responses within teams within randomized clusters, defining teams by attending physician. As this correlation was negligible and not statistically significant, we did not adjust ordinary linear regression models for clustering. Given observed differences in patient characteristics, we adjusted for a number of covariates (eg, age, gender, insurance payer, race, marital status, trial group arm).

We conducted simple linear regression for attending and trainee satisfaction comparisons between arms, adjusting only for trainee type (eg, resident, intern, and medical student).

We compared the frequency with which intervention and control teams adhered to the 5 recommended AR practices using chi-square tests. We used independent Student’s t tests to compare total duration of AR by teams within each arm, as well as mean time spent per patient.

This trial had a fixed number of arms (n = 2), each of fixed size (n = 600), based on the average monthly inpatient census on the medicine service. This fixed sample size, with 80% power and α = 0.05, will be able to detect a 0.16 difference in patient satisfaction scores between groups.

All analyses were conducted using SAS® v 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

We observed 241 AR involving 1855 patient rounding encounters in the intervention arm and 264 AR involving 1903 patient rounding encounters in the control arm (response rates shown in Figure 1).

Patient Satisfaction and Clinical Outcomes

Five hundred ninety-five patients were allocated to the intervention arm and 605 were allocated to the control arm (Figure 1). Mean age, gender, race, marital status, primary language, and insurance provider did not differ between intervention and control arms (Table 1).

Patients in the intervention arm reported significantly higher satisfaction with AR and felt more cared for by their medicine team (Table 2).

Actual and Perceived Duration of Attending Rounds

The intervention shortened the total duration of AR by 8 minutes on average (143 vs. 151 minutes, P = 0.052) and the time spent per patient by 4 minutes on average (19 vs. 23 minutes, P < 0.001). Despite this, trainees in the intervention arm perceived AR to last longer (mean estimated time: 167 min vs. 152 min, P < 0.001).

Healthcare Provider Outcomes

We observed 79 attending physicians and trainees in the intervention arm and 78 in the control arm, with survey response rates shown in Figure 1. Attending physicians in the intervention and the control arms reported high levels of satisfaction with the quality of AR (Table 2). Attending physicians in the intervention arm were more likely to report an appropriate level of patient involvement and nurse involvement.

Although trainees in the intervention and control arms reported high levels of satisfaction with the quality of AR, trainees in the intervention arm reported lower satisfaction with AR compared with control arm trainees (Table 2). Trainees in the intervention arm reported that AR involved less autonomy, efficiency, and teaching. Trainees in the intervention arm also scored patient involvement more towards the “far too much” end of the scale compared with “about right” in the control arm. However, trainees in the intervention arm perceived nurse involvement closer to “about right,” as opposed to “far too little” in the control arm.

CONCLUSION/DISCUSSION

Training internal medicine teams to adhere to 5 recommended AR practices increased patient satisfaction with AR and the perception that patients were more cared for by their medicine team. Despite the intervention potentially shortening the duration of AR, attending physicians and trainees perceived AR to last longer, and trainee satisfaction with AR decreased.

Teams in the intervention arm adhered to all recommended rounding practices at higher rates than the control teams. Although intervention teams rounded at the bedside 53% of the time, they were encouraged to bedside round only on patients who desired to participate in rounds, were not altered, and for whom the clinical discussion was not too sensitive to occur at the bedside. Of the recommended rounding behaviors, the lowest adherence was seen with whiteboard use.

A major component of the intervention was to move the clinical presentation to the patient’s bedside. Most patients prefer being included in rounds and partaking in trainee education.12-19,28,29,31-33 Patients may also perceive that more time is spent with them during bedside case presentations,14,28 and exposure to providers conferring on their care may enhance patient confidence in the care being delivered.12 Although a recent study of patient-centered bedside rounding on a nonteaching service did not result in increased patient satisfaction,24 teaching services may offer more opportunities for improvement in care coordination and communication.4

Other aspects of the intervention may have contributed to increased patient satisfaction with AR. The pre-rounds huddle may have helped teams prioritize which patients required more time or would benefit most from bedside rounds. The involvement of nurses in AR may have bolstered communication and team dynamics, enhancing the patient’s perception of interprofessional collaboration. Real-time order entry might have led to more efficient implementation of the care plan, and whiteboard use may have helped to keep patients abreast of the care plan.

Patients in the intervention arm felt more cared for by their medicine teams but did not report improvements in communication or in shared decision-making. Prior work highlights that limited patient engagement, activation, and shared decision-making may occur during AR.24,34 Patient-physician communication during AR is challenged by time pressures and competing priorities, including the “need” for trainees to demonstrate their medical knowledge and clinical skills. Efforts that encourage bedside rounding should include communication training with respect to patient engagement and shared decision-making.

Attending physicians reported positive attitudes toward bedside rounding, consistent with prior studies.13,21,31 However, trainees in the intervention arm expressed decreased satisfaction with AR, estimating that AR took longer and reporting too much patient involvement. Prior studies reflect similar bedside-rounding concerns, including perceived workflow inefficiencies, infringement on teaching opportunities, and time constraints.12,20,35 Trainees are under intense time pressures to complete their work, attend educational conferences, and leave the hospital to attend afternoon clinic or to comply with duty-hour restrictions. Trainees value succinctness,12,35,36 so the perception that intervention AR lasted longer likely contributed to trainee dissatisfaction.

Reduced trainee satisfaction with intervention AR may have also stemmed from the perception of decreased autonomy and less teaching, both valued by trainees.20,35,36 The intervention itself reduced trainee autonomy because usual practice at our hospital involves residents deciding where and how to round. Attending physician presence at the bedside during rounds may have further infringed on trainee autonomy if the patient looked to the attending for answers, or if the attending was seen as the AR leader. Attending physicians may mitigate the risk of compromising trainee autonomy by allowing the trainee to speak first, ensuring the trainee is positioned closer to, and at eye level with, the patient, and redirecting patient questions to the trainee as appropriate. Optimizing trainee experience with bedside AR requires preparation and training of attending physicians, who may feel inadequately prepared to lead bedside rounds and conduct bedside teaching.37 Faculty must learn how to preserve team efficiency, create a safe, nonpunitive bedside environment that fosters the trainee-patient relationship, and ensure rounds remain educational.36,38,39

The intervention reduced the average time spent on AR and time spent per patient. Studies examining the relationship between bedside rounding and duration of rounds have yielded mixed results: some have demonstrated no effect of bedside rounds on rounding time,28,40 while others report longer rounding times.37 The pre-rounds huddle and real-time order writing may have enhanced workflow efficiency.

Our study has several limitations. These results reflect the experience of a single large academic medical center and may not be generalizable to other settings. Although overall patient response to the survey was low and may not be representative of the entire patient population, response rates in the intervention and control arms were equivalent. Non-English speaking patients may have preferences that were not reflected in our survey results, and we did not otherwise quantify individual reasons for survey noncompletion. The presence of auditors on AR may have introduced observer bias. There may have been crossover effect; however, observed prevalence of individual practices remained low in the control arm. The 1.5-hour workshop may have inadequately equipped trainees with the complex skills required to lead and participate in bedside rounding, and more training, experience, and feedback may have yielded different results. For instance, residents with more exposure to bedside rounding express greater appreciation of its role in education and patient care.20 While adherence to some of the recommended practices remained low, we did not employ a full range of change-management techniques. Instead, we opted for a “low intensity” intervention (eg, single workshop, handouts) that relied on voluntary adoption by medicine teams and that we hoped other institutions could reproduce. Finally, we did not assess the relative impact of individual rounding behaviors on the measured outcomes.

In conclusion, training medicine teams to adhere to a standardized bedside AR model increased patient satisfaction with rounds. Concomitant trainee dissatisfaction may require further experience and training of attending physicians and trainees to ensure successful adoption.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients, providers, and trainees who participated in this study. We would also like to acknowledge the following volunteer auditors who observed teams daily: Arianna Abundo, Elahhe Afkhamnejad, Yolanda Banuelos, Laila Fozoun, Soe Yupar Khin, Tam Thien Le, Wing Sum Li, Yaqiao Li, Mengyao Liu, Tzyy-Harn Lo, Shynh-Herng Lo, David Lowe, Danoush Paborji, Sa Nan Park, Urmila Powale, Redha Fouad Qabazard, Monique Quiroz, John-Luke Marcelo Rivera, Manfred Roy Luna Salvador, Tobias Gowen Squier-Roper, Flora Yan Ting, Francesca Natasha T. Tizon, Emily Claire Trautner, Stephen Weiner, Alice Wilson, Kimberly Woo, Bingling J Wu, Johnny Wu, Brenda Yee. Statistical expertise was provided by Joan Hilton from the UCSF Clinical and Translational Science Institute (CTSI), which is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through UCSF-CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR000004. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Thanks also to Oralia Schatzman, Andrea Mazzini, and Erika Huie for their administrative support, and John Hillman for data-related support. Special thanks to Kirsten Kangelaris and Andrew Auerbach for their valuable feedback throughout, and to Maria Novelero and Robert Wachter for their divisional support of this project.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial conflicts of interest.

1. Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):1-18. PubMed

2. Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) Fact Sheet. August 2013. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Baltimore, MD.http://www.hcahpsonline.org/files/August_2013_HCAHPS_Fact_Sheet3.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2015.

3. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:41-48. PubMed

4. Wray CM, Flores A, Padula WV, Prochaska MT, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. Measuring patient experiences on hospitalist and teaching services: Patient responses to a 30-day postdischarge questionnaire. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):99-104. PubMed

5. Bharwani AM, Harris GC, Southwick FS. Perspective: A business school view of medical interprofessional rounds: transforming rounding groups into rounding teams. Acad Med. 2012;87(12):1768-1771. PubMed

6. Chand DV. Observational study using the tools of lean six sigma to improve the efficiency of the resident rounding process. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):144-150. PubMed

7. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. PubMed

8. Weber H, Stöckli M, Nübling M, Langewitz WA. Communication during ward rounds in internal medicine. An analysis of patient-nurse-physician interactions using RIAS. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):343-348. PubMed

9. McMahon GT, Katz JT, Thorndike ME, Levy BD, Loscalzo J. Evaluation of a redesign initiative in an internal-medicine residency. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1304-1311. PubMed

10. Amoss J. Attending rounds: where do we go from here?: comment on “Attending rounds in the current era”. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1089-1090. PubMed

11. Curley C, McEachern JE, Speroff T. A firm trial of interdisciplinary rounds on the inpatient medical wards: an intervention designed using continuous quality improvement. Med Care. 1998;36(suppl 8):AS4-A12. PubMed

12. Wang-Cheng RM, Barnas GP, Sigmann P, Riendl PA, Young MJ. Bedside case presentations: why patients like them but learners don’t. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(4):284-287. PubMed

13. Chauke, HL, Pattinson RC. Ward rounds—bedside or conference room? S Afr Med J. 2006;96(5):398-400. PubMed

14. Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, Roter D, Dobs AS. The effect of bedside case presentations on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):336, 1150-1155. PubMed

15. Simons RJ, Baily RG, Zelis R, Zwillich CW. The physiologic and psychological effects of the bedside presentation. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(18):1273-1275. PubMed

16. Wise TN, Feldheim D, Mann LS, Boyle E, Rustgi VK. Patients’ reactions to house staff work rounds. Psychosomatics. 1985;26(8):669-672. PubMed

17. Linfors EW, Neelon FA. Sounding Boards. The case of bedside rounds. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(21):1230-1233. PubMed

18. Nair BR, Coughlan JL, Hensley MJ. Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching. Med Educ. 1997;31(5):341-346. PubMed

19. Romano J. Patients’ attitudes and behavior in ward round teaching. JAMA. 1941;117(9):664-667.

20. Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105-110. PubMed

21. Shoeb M, Khanna R, Fang M, et al. Internal medicine rounding practices and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):239-243. PubMed

22. Calderon AS, Blackmore CC, Williams BL, et al. Transforming ward rounds through rounding-in-flow. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):750-755. PubMed

23. Henkin S, Chon TY, Christopherson ML, Halvorsen AJ, Worden LM, Ratelle JT. Improving nurse-physician teamwork through interprofessional bedside rounding. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:201-205. PubMed

24. O’Leary KJ, Killarney A, Hansen LO, et al. Effect of patient-centred bedside rounds on hospitalised patients’ decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:921-928. PubMed

25. Southwick F, Lewis M, Treloar D, et al. Applying athletic principles to medical rounds to improve teaching and patient care. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1018-1023. PubMed

26. Najafi N, Monash B, Mourad M, et al. Improving attending rounds: Qualitative reflections from multidisciplinary providers. Hosp Pract (1995). 2015;43(3):186-190. PubMed

27. Altman DG. Practical Statistics For Medical Research. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2006.

28. Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Huang G, Smith C. The return of bedside rounds: an educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):792-798. PubMed

29. Fletcher KE, Rankey DS, Stern DT. Bedside interactions from the other side of the bedrail. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(1):58-61. PubMed

30. Gatorounds: Applying Championship Athletic Principles to Healthcare. University of Florida Health. http://gatorounds.med.ufl.edu/surveys/. Accessed March 1, 2013.

31. Gonzalo JD, Heist BS, Duffy BL, et al. The value of bedside rounds: a multicenter qualitative study. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(4):326-333. PubMed

32. Rogers HD, Carline JD, Paauw DS. Examination room presentations in general internal medicine clinic: patients’ and students’ perceptions. Acad Med. 2003;78(9):945-949. PubMed

33. Fletcher KE, Furney SL, Stern DT. Patients speak: what’s really important about bedside interactions with physician teams. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(2):120-127. PubMed

34. Satterfield JM, Bereknyei S, Hilton JF, et al. The prevalence of social and behavioral topics and related educational opportunities during attending rounds. Acad Med. 2014; 89(11):1548-1557. PubMed

35. Kroenke K, Simmons JO, Copley JB, Smith C. Attending rounds: a survey of physician attitudes. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5(3):229-233. PubMed

36. Castiglioni A, Shewchuk RM, Willett LL, Heudebert GR, Centor RM. A pilot study using nominal group technique to assess residents’ perceptions of successful attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1060-1065. PubMed

37. Crumlish CM, Yialamas MA, McMahon GT. Quantification of bedside teaching by an academic hospitalist group. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(5):304-307. PubMed

38. Gonzalo JD, Wolpaw DR, Lehman E, Chuang CH. Patient-centered interprofessional collaborative care: factors associated with bedside interprofessional rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1040-1047. PubMed

39. Roy B, Castiglioni A, Kraemer RR, et al. Using cognitive mapping to define key domains for successful attending rounds. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1492-1498. PubMed

40. Bhansali P, Birch S, Campbell JK, et al. A time-motion study of inpatient rounds using a family-centered rounds model. Hosp Pediatr. 2013;3(1):31-38. PubMed

1. Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013;3(1):1-18. PubMed

2. Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) Fact Sheet. August 2013. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Baltimore, MD.http://www.hcahpsonline.org/files/August_2013_HCAHPS_Fact_Sheet3.pdf. Accessed December 1, 2015.

3. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17:41-48. PubMed

4. Wray CM, Flores A, Padula WV, Prochaska MT, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. Measuring patient experiences on hospitalist and teaching services: Patient responses to a 30-day postdischarge questionnaire. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(2):99-104. PubMed

5. Bharwani AM, Harris GC, Southwick FS. Perspective: A business school view of medical interprofessional rounds: transforming rounding groups into rounding teams. Acad Med. 2012;87(12):1768-1771. PubMed

6. Chand DV. Observational study using the tools of lean six sigma to improve the efficiency of the resident rounding process. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(2):144-150. PubMed

7. Stickrath C, Noble M, Prochazka A, et al. Attending rounds in the current era: what is and is not happening. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1084-1089. PubMed

8. Weber H, Stöckli M, Nübling M, Langewitz WA. Communication during ward rounds in internal medicine. An analysis of patient-nurse-physician interactions using RIAS. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67(3):343-348. PubMed

9. McMahon GT, Katz JT, Thorndike ME, Levy BD, Loscalzo J. Evaluation of a redesign initiative in an internal-medicine residency. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(14):1304-1311. PubMed

10. Amoss J. Attending rounds: where do we go from here?: comment on “Attending rounds in the current era”. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1089-1090. PubMed

11. Curley C, McEachern JE, Speroff T. A firm trial of interdisciplinary rounds on the inpatient medical wards: an intervention designed using continuous quality improvement. Med Care. 1998;36(suppl 8):AS4-A12. PubMed

12. Wang-Cheng RM, Barnas GP, Sigmann P, Riendl PA, Young MJ. Bedside case presentations: why patients like them but learners don’t. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4(4):284-287. PubMed

13. Chauke, HL, Pattinson RC. Ward rounds—bedside or conference room? S Afr Med J. 2006;96(5):398-400. PubMed

14. Lehmann LS, Brancati FL, Chen MC, Roter D, Dobs AS. The effect of bedside case presentations on patients’ perceptions of their medical care. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(16):336, 1150-1155. PubMed

15. Simons RJ, Baily RG, Zelis R, Zwillich CW. The physiologic and psychological effects of the bedside presentation. N Engl J Med. 1989;321(18):1273-1275. PubMed

16. Wise TN, Feldheim D, Mann LS, Boyle E, Rustgi VK. Patients’ reactions to house staff work rounds. Psychosomatics. 1985;26(8):669-672. PubMed

17. Linfors EW, Neelon FA. Sounding Boards. The case of bedside rounds. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(21):1230-1233. PubMed

18. Nair BR, Coughlan JL, Hensley MJ. Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching. Med Educ. 1997;31(5):341-346. PubMed

19. Romano J. Patients’ attitudes and behavior in ward round teaching. JAMA. 1941;117(9):664-667.

20. Gonzalo JD, Masters PA, Simons RJ, Chuang CH. Attending rounds and bedside case presentations: medical student and medicine resident experiences and attitudes. Teach Learn Med. 2009;21(2):105-110. PubMed

21. Shoeb M, Khanna R, Fang M, et al. Internal medicine rounding practices and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(4):239-243. PubMed

22. Calderon AS, Blackmore CC, Williams BL, et al. Transforming ward rounds through rounding-in-flow. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(4):750-755. PubMed

23. Henkin S, Chon TY, Christopherson ML, Halvorsen AJ, Worden LM, Ratelle JT. Improving nurse-physician teamwork through interprofessional bedside rounding. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2016;9:201-205. PubMed

24. O’Leary KJ, Killarney A, Hansen LO, et al. Effect of patient-centred bedside rounds on hospitalised patients’ decision control, activation and satisfaction with care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:921-928. PubMed

25. Southwick F, Lewis M, Treloar D, et al. Applying athletic principles to medical rounds to improve teaching and patient care. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1018-1023. PubMed

26. Najafi N, Monash B, Mourad M, et al. Improving attending rounds: Qualitative reflections from multidisciplinary providers. Hosp Pract (1995). 2015;43(3):186-190. PubMed

27. Altman DG. Practical Statistics For Medical Research. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall/CRC; 2006.

28. Gonzalo JD, Chuang CH, Huang G, Smith C. The return of bedside rounds: an educational intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):792-798. PubMed

29. Fletcher KE, Rankey DS, Stern DT. Bedside interactions from the other side of the bedrail. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(1):58-61. PubMed

30. Gatorounds: Applying Championship Athletic Principles to Healthcare. University of Florida Health. http://gatorounds.med.ufl.edu/surveys/. Accessed March 1, 2013.