User login

Medicare to Cut Payment For Cancer Radiotherapies

Radiation oncologists could see a nearly 15% cut to their payments under the proposed 2013 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.

About half of the planned cut is as a result of changes in the way Medicare calculates the time involved in performing intensity-modulated radiation treatment (IMRT) delivery and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) delivery. Using patient education materials published by leading medical societies, officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services determined that they were paying too much for IMRT and SBRT because these services don’t take as long to perform as had previously been calculated.

For example, the current CPT code for IMRT treatment delivery (77418) is based on an assumption that the procedure will take 60 minutes to perform. However, information from patient fact sheets showed a significantly faster procedure time. As a result, the CMS is proposing to base payment on a procedure time of 30 minutes.

For SBRT treatment delivery (CPT code 77373), the current procedure time assumption is 90 minutes. The proposed procedure time assumption is 60 minutes, based on publicly available patient education materials.

The CMS reviewed the procedure time assumptions associated with IMRT and SBRT as part of an overall review of potentially "misvalued" codes.

Officials at ASTRO (American Society for Radiation Oncology), which represents radiation oncologists, criticized the proposal, saying that it would curb patient access to treatment, particularly in rural communities. They pointed to the preliminary results of a member survey that showed that some radiation oncology practices may be forced to close, while others would delay the purchase of new equipment, lay off staff, or limit the new Medicare patients they treat.

The organization also took issue with the process the CMS used in evaluating the procedures.

"ASTRO believes that [the CMS] should utilize the rigorous processes and methodologies already in place and utilized for the past 20 years to set reimbursement rates," Dr. Leonard L. Gunderson, chairman of ASTRO’s Board of Directors, said in a statement.

Dr. Gunderson said that ASTRO would like to see a comprehensive review of treatment costs through the American Medical Association’s Specialty Society Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC), a panel of 31 physicians who offer advice to the CMS on how to value physician services.

Radiation oncologists could see a nearly 15% cut to their payments under the proposed 2013 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.

About half of the planned cut is as a result of changes in the way Medicare calculates the time involved in performing intensity-modulated radiation treatment (IMRT) delivery and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) delivery. Using patient education materials published by leading medical societies, officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services determined that they were paying too much for IMRT and SBRT because these services don’t take as long to perform as had previously been calculated.

For example, the current CPT code for IMRT treatment delivery (77418) is based on an assumption that the procedure will take 60 minutes to perform. However, information from patient fact sheets showed a significantly faster procedure time. As a result, the CMS is proposing to base payment on a procedure time of 30 minutes.

For SBRT treatment delivery (CPT code 77373), the current procedure time assumption is 90 minutes. The proposed procedure time assumption is 60 minutes, based on publicly available patient education materials.

The CMS reviewed the procedure time assumptions associated with IMRT and SBRT as part of an overall review of potentially "misvalued" codes.

Officials at ASTRO (American Society for Radiation Oncology), which represents radiation oncologists, criticized the proposal, saying that it would curb patient access to treatment, particularly in rural communities. They pointed to the preliminary results of a member survey that showed that some radiation oncology practices may be forced to close, while others would delay the purchase of new equipment, lay off staff, or limit the new Medicare patients they treat.

The organization also took issue with the process the CMS used in evaluating the procedures.

"ASTRO believes that [the CMS] should utilize the rigorous processes and methodologies already in place and utilized for the past 20 years to set reimbursement rates," Dr. Leonard L. Gunderson, chairman of ASTRO’s Board of Directors, said in a statement.

Dr. Gunderson said that ASTRO would like to see a comprehensive review of treatment costs through the American Medical Association’s Specialty Society Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC), a panel of 31 physicians who offer advice to the CMS on how to value physician services.

Radiation oncologists could see a nearly 15% cut to their payments under the proposed 2013 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule.

About half of the planned cut is as a result of changes in the way Medicare calculates the time involved in performing intensity-modulated radiation treatment (IMRT) delivery and stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) delivery. Using patient education materials published by leading medical societies, officials at the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services determined that they were paying too much for IMRT and SBRT because these services don’t take as long to perform as had previously been calculated.

For example, the current CPT code for IMRT treatment delivery (77418) is based on an assumption that the procedure will take 60 minutes to perform. However, information from patient fact sheets showed a significantly faster procedure time. As a result, the CMS is proposing to base payment on a procedure time of 30 minutes.

For SBRT treatment delivery (CPT code 77373), the current procedure time assumption is 90 minutes. The proposed procedure time assumption is 60 minutes, based on publicly available patient education materials.

The CMS reviewed the procedure time assumptions associated with IMRT and SBRT as part of an overall review of potentially "misvalued" codes.

Officials at ASTRO (American Society for Radiation Oncology), which represents radiation oncologists, criticized the proposal, saying that it would curb patient access to treatment, particularly in rural communities. They pointed to the preliminary results of a member survey that showed that some radiation oncology practices may be forced to close, while others would delay the purchase of new equipment, lay off staff, or limit the new Medicare patients they treat.

The organization also took issue with the process the CMS used in evaluating the procedures.

"ASTRO believes that [the CMS] should utilize the rigorous processes and methodologies already in place and utilized for the past 20 years to set reimbursement rates," Dr. Leonard L. Gunderson, chairman of ASTRO’s Board of Directors, said in a statement.

Dr. Gunderson said that ASTRO would like to see a comprehensive review of treatment costs through the American Medical Association’s Specialty Society Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC), a panel of 31 physicians who offer advice to the CMS on how to value physician services.

ACO-Like Demo Produces 'Modest' Savings

The Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration, which was the inspiration for the accountable care organization pilots currently underway, achieved only "modest" overall savings, according to an analysis published in the Sept. 12 issue of JAMA.

On average, the Physician Group Practice Demonstration (PGPD) saved the Medicare program $114 annually per beneficiary. However, the biggest savings came from low-income beneficiaries who were dually eligible for both the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Physician groups enrolled in the pilot project were able to save the Medicare program $532 on average (or 5%) for dual-eligible beneficiaries.

The average savings for beneficiaries who were eligible for Medicare only was a $59 per year, which was not statistically significant (JAMA 2012;308:1015-23).

The findings could foreshadow the performance of accountable care organizations (ACOs), since the PGPD pilot also allowed physicians to share in savings if they could lower costs while improving quality and care coordination.

The three ACO pilots now underway were included in the Affordable Care Act in part because of promising results from the PGPD. Under the PGPD, 10 physician practices could earn up to 80% of any savings to the Medicare program, provided they generated at least 2% in savings. In addition, they also had to show improvement on 32 quality measures that included preventive care and chronic care management.

Researchers at Dartmouth College analyzed Medicare administrative data from 2001 through 2009 to determine the per-beneficiary savings from the program and to see how it varied among Medicare beneficiaries and so-called dual eligibles.

While the savings for Medicare-only beneficiaries were small, the PGPD sites did well at reducing costs for dual-eligible beneficiaries, according to the study. The spending growth rate for dual-eligible beneficiaries in the PGPD sites was 9.7% compared with 15.3% for local control practices between the preintervention and postintervention periods, resulting in an average annual per beneficiary savings of $532.

The 5% decrease in Medicare spending among dual-eligibles came mostly through fewer acute care hospitalizations, procedures, and home health care services, the researchers wrote. Since the savings were similar across diagnosis groups, the researchers suggested that the savings were likely due to better overall care management, rather than disease-specific interventions.

The results highlight the "potential benefits of the ACO model for patients with serious or complex illness, a group for whom improved quality and coordination is especially important," the researchers wrote.

The PGPD practices also had lower 30-day hospital readmission rates on average for medical reasons and lower readmissions for both medical and surgical admissions among dual-eligible beneficiaries, according to the study.

The researchers also found significant variation in how each PGPD site performed, which also could hold clues for future ACO success.

For instance, some sites were able to achieve large spending reductions, while others saw their costs increase compared to local control practices. The researchers speculated that the size of the institution could play a role, with larger systems having the advantage because they already had health information technology systems in place and generally had more resources to invest in improvements in care.

"The remarkable degree of heterogeneity across participating sites underscores the importance of timely evaluation of current payment reforms and a better understanding of the institutional factors that lead to either success or failure in effecting changes in health care practices," the researchers wrote.

The research was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, the Dartmouth Atlas Project, and the Commonwealth Fund. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, or approval of the manuscript. The study authors reported having no financial disclosures.

Results of the latest analysis show an encouraging trend in lowering costs for beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid programs. That group is critical because they account for more than $300 billion in annual costs and 40% of state Medicaid expenditures.

|

The variation among the pilot sites offers hope for continual learning about best practices and possibly improved results as physicians and researchers learn what works.

While the ACO model holds a lot of promise, it is not the only option reforming the way care is delivered. The model deserves energy, investment, discipline, and good faith; they can help. But, whether federal officials are encouraged or discouraged by the PGPD experience, a lot more innovations than ACOs alone will be needed to emerge successfully from this fraught time.

Donald M. Berwick, M.D., is a former CMS administrator and former president and CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. His remarks were made in an editorial accompanying the study by Dartmouth researchers (JAMA 2012;308:1038-9). H e reported no financial disclosures.

Results of the latest analysis show an encouraging trend in lowering costs for beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid programs. That group is critical because they account for more than $300 billion in annual costs and 40% of state Medicaid expenditures.

|

The variation among the pilot sites offers hope for continual learning about best practices and possibly improved results as physicians and researchers learn what works.

While the ACO model holds a lot of promise, it is not the only option reforming the way care is delivered. The model deserves energy, investment, discipline, and good faith; they can help. But, whether federal officials are encouraged or discouraged by the PGPD experience, a lot more innovations than ACOs alone will be needed to emerge successfully from this fraught time.

Donald M. Berwick, M.D., is a former CMS administrator and former president and CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. His remarks were made in an editorial accompanying the study by Dartmouth researchers (JAMA 2012;308:1038-9). H e reported no financial disclosures.

Results of the latest analysis show an encouraging trend in lowering costs for beneficiaries who are dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid programs. That group is critical because they account for more than $300 billion in annual costs and 40% of state Medicaid expenditures.

|

The variation among the pilot sites offers hope for continual learning about best practices and possibly improved results as physicians and researchers learn what works.

While the ACO model holds a lot of promise, it is not the only option reforming the way care is delivered. The model deserves energy, investment, discipline, and good faith; they can help. But, whether federal officials are encouraged or discouraged by the PGPD experience, a lot more innovations than ACOs alone will be needed to emerge successfully from this fraught time.

Donald M. Berwick, M.D., is a former CMS administrator and former president and CEO of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement. His remarks were made in an editorial accompanying the study by Dartmouth researchers (JAMA 2012;308:1038-9). H e reported no financial disclosures.

The Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration, which was the inspiration for the accountable care organization pilots currently underway, achieved only "modest" overall savings, according to an analysis published in the Sept. 12 issue of JAMA.

On average, the Physician Group Practice Demonstration (PGPD) saved the Medicare program $114 annually per beneficiary. However, the biggest savings came from low-income beneficiaries who were dually eligible for both the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Physician groups enrolled in the pilot project were able to save the Medicare program $532 on average (or 5%) for dual-eligible beneficiaries.

The average savings for beneficiaries who were eligible for Medicare only was a $59 per year, which was not statistically significant (JAMA 2012;308:1015-23).

The findings could foreshadow the performance of accountable care organizations (ACOs), since the PGPD pilot also allowed physicians to share in savings if they could lower costs while improving quality and care coordination.

The three ACO pilots now underway were included in the Affordable Care Act in part because of promising results from the PGPD. Under the PGPD, 10 physician practices could earn up to 80% of any savings to the Medicare program, provided they generated at least 2% in savings. In addition, they also had to show improvement on 32 quality measures that included preventive care and chronic care management.

Researchers at Dartmouth College analyzed Medicare administrative data from 2001 through 2009 to determine the per-beneficiary savings from the program and to see how it varied among Medicare beneficiaries and so-called dual eligibles.

While the savings for Medicare-only beneficiaries were small, the PGPD sites did well at reducing costs for dual-eligible beneficiaries, according to the study. The spending growth rate for dual-eligible beneficiaries in the PGPD sites was 9.7% compared with 15.3% for local control practices between the preintervention and postintervention periods, resulting in an average annual per beneficiary savings of $532.

The 5% decrease in Medicare spending among dual-eligibles came mostly through fewer acute care hospitalizations, procedures, and home health care services, the researchers wrote. Since the savings were similar across diagnosis groups, the researchers suggested that the savings were likely due to better overall care management, rather than disease-specific interventions.

The results highlight the "potential benefits of the ACO model for patients with serious or complex illness, a group for whom improved quality and coordination is especially important," the researchers wrote.

The PGPD practices also had lower 30-day hospital readmission rates on average for medical reasons and lower readmissions for both medical and surgical admissions among dual-eligible beneficiaries, according to the study.

The researchers also found significant variation in how each PGPD site performed, which also could hold clues for future ACO success.

For instance, some sites were able to achieve large spending reductions, while others saw their costs increase compared to local control practices. The researchers speculated that the size of the institution could play a role, with larger systems having the advantage because they already had health information technology systems in place and generally had more resources to invest in improvements in care.

"The remarkable degree of heterogeneity across participating sites underscores the importance of timely evaluation of current payment reforms and a better understanding of the institutional factors that lead to either success or failure in effecting changes in health care practices," the researchers wrote.

The research was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, the Dartmouth Atlas Project, and the Commonwealth Fund. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, or approval of the manuscript. The study authors reported having no financial disclosures.

The Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration, which was the inspiration for the accountable care organization pilots currently underway, achieved only "modest" overall savings, according to an analysis published in the Sept. 12 issue of JAMA.

On average, the Physician Group Practice Demonstration (PGPD) saved the Medicare program $114 annually per beneficiary. However, the biggest savings came from low-income beneficiaries who were dually eligible for both the Medicare and Medicaid programs. Physician groups enrolled in the pilot project were able to save the Medicare program $532 on average (or 5%) for dual-eligible beneficiaries.

The average savings for beneficiaries who were eligible for Medicare only was a $59 per year, which was not statistically significant (JAMA 2012;308:1015-23).

The findings could foreshadow the performance of accountable care organizations (ACOs), since the PGPD pilot also allowed physicians to share in savings if they could lower costs while improving quality and care coordination.

The three ACO pilots now underway were included in the Affordable Care Act in part because of promising results from the PGPD. Under the PGPD, 10 physician practices could earn up to 80% of any savings to the Medicare program, provided they generated at least 2% in savings. In addition, they also had to show improvement on 32 quality measures that included preventive care and chronic care management.

Researchers at Dartmouth College analyzed Medicare administrative data from 2001 through 2009 to determine the per-beneficiary savings from the program and to see how it varied among Medicare beneficiaries and so-called dual eligibles.

While the savings for Medicare-only beneficiaries were small, the PGPD sites did well at reducing costs for dual-eligible beneficiaries, according to the study. The spending growth rate for dual-eligible beneficiaries in the PGPD sites was 9.7% compared with 15.3% for local control practices between the preintervention and postintervention periods, resulting in an average annual per beneficiary savings of $532.

The 5% decrease in Medicare spending among dual-eligibles came mostly through fewer acute care hospitalizations, procedures, and home health care services, the researchers wrote. Since the savings were similar across diagnosis groups, the researchers suggested that the savings were likely due to better overall care management, rather than disease-specific interventions.

The results highlight the "potential benefits of the ACO model for patients with serious or complex illness, a group for whom improved quality and coordination is especially important," the researchers wrote.

The PGPD practices also had lower 30-day hospital readmission rates on average for medical reasons and lower readmissions for both medical and surgical admissions among dual-eligible beneficiaries, according to the study.

The researchers also found significant variation in how each PGPD site performed, which also could hold clues for future ACO success.

For instance, some sites were able to achieve large spending reductions, while others saw their costs increase compared to local control practices. The researchers speculated that the size of the institution could play a role, with larger systems having the advantage because they already had health information technology systems in place and generally had more resources to invest in improvements in care.

"The remarkable degree of heterogeneity across participating sites underscores the importance of timely evaluation of current payment reforms and a better understanding of the institutional factors that lead to either success or failure in effecting changes in health care practices," the researchers wrote.

The research was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, the Dartmouth Atlas Project, and the Commonwealth Fund. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, or approval of the manuscript. The study authors reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Major Finding: The Physician Group Practice Demonstration resulted in overall savings to the Medicare program of $114 per beneficiary each year. Average savings were $532 per beneficiary among those dually eligible for the Medicare and Medicaid programs, while Medicare-only patients did not have statistically significant cost savings in the program.

Data Source: The researchers performed a retrospective analysis of Medicare claims data for all physician groups from 2001 through 2009.

Disclosures: The research was funded by a grant from the National Institute on Aging, the Dartmouth Atlas Project, and the Commonwealth Fund. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study, or approval of the manuscript. The study authors reported having no financial disclosures.

IOM: Technology, Incentives Can Fix Broken System

The U.S. health care system is hamstrung by high costs and inefficient care, wasting $750 billion in 2009 alone, but new technology and a better-designed payment system could help turn the system around, according to a report released Sept. 6 by the Institute of Medicine.

America’s disorganized and overly complex health care system is both too slow to adopt simple solutions like consistent provider handwashing, while also moving too quickly to implement costly and unproven new technologies and treatments, the IOM committee wrote.

The result is that for 31 of the past 40 years, health care costs have increased at a greater rate than the total U.S. economy. Health care costs also now account for about 18% of the country’s gross domestic product, according to the report.

"It would be one thing if we were getting good value for this money, but there is ample evidence, noted in the report, that there is tremendous waste in this system," Dr. Mark D. Smith, chair of the IOM committee and president and CEO of the California HealthCare Foundation in Oakland, said during a press conference to release the report.

The IOM committee estimates that about 30% of U.S. health spending in 2009 – about $750 billion – was spent on unnecessary services, excessive administrative costs, and fraud. And in 2005, 75,000 deaths might have been prevented if all states had delivered the same quality of care as the highest performing state, according to the committee.

Dr. Smith noted several examples of "wasted opportunities in American health care." For instance, less than half of elderly patients are up-to-date on clinical preventive services. These same patients also struggle to coordinate their care, seeing an average of seven physicians across four practices each year. On the hospital side, surgery patients are seen by 27 different providers during an average hospital stay. Still, one in five hospitalized patients is readmitted within 30 days of discharge.

Despite the challenges, Dr. Smith said the affordability of sophisticated computer technology and advances in the science of organizational management offer hope for moving to a system of higher quality care at lower cost.

A crucial first step, however, must be to change the payment incentives so that physicians are not paid for doing more, but instead are paid for better clinical outcomes.

"We need to have a financial environment in which providing high-value care is rewarded by payers and that reward requires that the delivery of high-value care be known to everyone," Dr. Smith said. "That’s why transparency is important, rather than reputation."

The IOM committee recommended that both private and public payers begin to reward improvement and learning through outcome-based and value-oriented payment models. They also said payments should favor team-based care that focuses on patient goals.

Health care organizations and payers also should make available more information on quality and cost, the IOM committee wrote.

Clinical decision support is another key element in improving a health care system that is overwhelmed with data, according to the IOM report. "It’s not good enough for the answer to be in a journal that you might read later on that night when the patient has already gone home," Dr. Smith said, adding that there also needs to be a way to capture clinical data for quality improvement and research purposes.

Other key elements recommended by the IOM committee include getting patients more involved in their care, establishing better communication between inpatient and outpatient physicians, and using management tools from the retail industry to change the "culture" in health care and provide more support for learning and quality improvement.

That cultural shift also includes a move from a "cost agnostic" approach to a "cost aware" approach by clinicians, Dr. Smith said.

The report was sponsored by the Blue Shield of California Foundation, Charina Endowment Fund, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The U.S. health care system is hamstrung by high costs and inefficient care, wasting $750 billion in 2009 alone, but new technology and a better-designed payment system could help turn the system around, according to a report released Sept. 6 by the Institute of Medicine.

America’s disorganized and overly complex health care system is both too slow to adopt simple solutions like consistent provider handwashing, while also moving too quickly to implement costly and unproven new technologies and treatments, the IOM committee wrote.

The result is that for 31 of the past 40 years, health care costs have increased at a greater rate than the total U.S. economy. Health care costs also now account for about 18% of the country’s gross domestic product, according to the report.

"It would be one thing if we were getting good value for this money, but there is ample evidence, noted in the report, that there is tremendous waste in this system," Dr. Mark D. Smith, chair of the IOM committee and president and CEO of the California HealthCare Foundation in Oakland, said during a press conference to release the report.

The IOM committee estimates that about 30% of U.S. health spending in 2009 – about $750 billion – was spent on unnecessary services, excessive administrative costs, and fraud. And in 2005, 75,000 deaths might have been prevented if all states had delivered the same quality of care as the highest performing state, according to the committee.

Dr. Smith noted several examples of "wasted opportunities in American health care." For instance, less than half of elderly patients are up-to-date on clinical preventive services. These same patients also struggle to coordinate their care, seeing an average of seven physicians across four practices each year. On the hospital side, surgery patients are seen by 27 different providers during an average hospital stay. Still, one in five hospitalized patients is readmitted within 30 days of discharge.

Despite the challenges, Dr. Smith said the affordability of sophisticated computer technology and advances in the science of organizational management offer hope for moving to a system of higher quality care at lower cost.

A crucial first step, however, must be to change the payment incentives so that physicians are not paid for doing more, but instead are paid for better clinical outcomes.

"We need to have a financial environment in which providing high-value care is rewarded by payers and that reward requires that the delivery of high-value care be known to everyone," Dr. Smith said. "That’s why transparency is important, rather than reputation."

The IOM committee recommended that both private and public payers begin to reward improvement and learning through outcome-based and value-oriented payment models. They also said payments should favor team-based care that focuses on patient goals.

Health care organizations and payers also should make available more information on quality and cost, the IOM committee wrote.

Clinical decision support is another key element in improving a health care system that is overwhelmed with data, according to the IOM report. "It’s not good enough for the answer to be in a journal that you might read later on that night when the patient has already gone home," Dr. Smith said, adding that there also needs to be a way to capture clinical data for quality improvement and research purposes.

Other key elements recommended by the IOM committee include getting patients more involved in their care, establishing better communication between inpatient and outpatient physicians, and using management tools from the retail industry to change the "culture" in health care and provide more support for learning and quality improvement.

That cultural shift also includes a move from a "cost agnostic" approach to a "cost aware" approach by clinicians, Dr. Smith said.

The report was sponsored by the Blue Shield of California Foundation, Charina Endowment Fund, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

The U.S. health care system is hamstrung by high costs and inefficient care, wasting $750 billion in 2009 alone, but new technology and a better-designed payment system could help turn the system around, according to a report released Sept. 6 by the Institute of Medicine.

America’s disorganized and overly complex health care system is both too slow to adopt simple solutions like consistent provider handwashing, while also moving too quickly to implement costly and unproven new technologies and treatments, the IOM committee wrote.

The result is that for 31 of the past 40 years, health care costs have increased at a greater rate than the total U.S. economy. Health care costs also now account for about 18% of the country’s gross domestic product, according to the report.

"It would be one thing if we were getting good value for this money, but there is ample evidence, noted in the report, that there is tremendous waste in this system," Dr. Mark D. Smith, chair of the IOM committee and president and CEO of the California HealthCare Foundation in Oakland, said during a press conference to release the report.

The IOM committee estimates that about 30% of U.S. health spending in 2009 – about $750 billion – was spent on unnecessary services, excessive administrative costs, and fraud. And in 2005, 75,000 deaths might have been prevented if all states had delivered the same quality of care as the highest performing state, according to the committee.

Dr. Smith noted several examples of "wasted opportunities in American health care." For instance, less than half of elderly patients are up-to-date on clinical preventive services. These same patients also struggle to coordinate their care, seeing an average of seven physicians across four practices each year. On the hospital side, surgery patients are seen by 27 different providers during an average hospital stay. Still, one in five hospitalized patients is readmitted within 30 days of discharge.

Despite the challenges, Dr. Smith said the affordability of sophisticated computer technology and advances in the science of organizational management offer hope for moving to a system of higher quality care at lower cost.

A crucial first step, however, must be to change the payment incentives so that physicians are not paid for doing more, but instead are paid for better clinical outcomes.

"We need to have a financial environment in which providing high-value care is rewarded by payers and that reward requires that the delivery of high-value care be known to everyone," Dr. Smith said. "That’s why transparency is important, rather than reputation."

The IOM committee recommended that both private and public payers begin to reward improvement and learning through outcome-based and value-oriented payment models. They also said payments should favor team-based care that focuses on patient goals.

Health care organizations and payers also should make available more information on quality and cost, the IOM committee wrote.

Clinical decision support is another key element in improving a health care system that is overwhelmed with data, according to the IOM report. "It’s not good enough for the answer to be in a journal that you might read later on that night when the patient has already gone home," Dr. Smith said, adding that there also needs to be a way to capture clinical data for quality improvement and research purposes.

Other key elements recommended by the IOM committee include getting patients more involved in their care, establishing better communication between inpatient and outpatient physicians, and using management tools from the retail industry to change the "culture" in health care and provide more support for learning and quality improvement.

That cultural shift also includes a move from a "cost agnostic" approach to a "cost aware" approach by clinicians, Dr. Smith said.

The report was sponsored by the Blue Shield of California Foundation, Charina Endowment Fund, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Arkansas Project to Share Savings With Doctors

Want to be paid extra for providing appropriate, cost-effective medical care? Doctors in Arkansas are about to find out what that’s all about as the state’s Medicaid program – along with two private insurance companies – kicks off a gainsharing program.

Under Arkansas’s Health Care Payment Improvement Initiative, health care payers have asked physicians and hospitals to keep costs for five high-volume episodes of care while still meeting quality standards. The episodes of care are perinatal care, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, upper respiratory infection, hip and knee replacement, and heart failure.

If providers succeed, they can share in the money saved by the insurers. If they don’t, they’ll need to return some of the excess fees.

"If you provide a service and you can do it with quality standards and good outcomes and do it less expensively than the other guy, we’re going to give you a bonus. The better doctors should do well," said Dr. William E. Golden, medical director of the Arkansas Medicaid program.

Other states, especially rural ones, will be watching how things play out in Arkansas, Dr. Golden said. "Everybody is going in this direction. We’ve just bitten off more of the apple faster than most."

The shift from simply paying for services provided to a cost-and-quality approach was undertaken in part to put the state’s Medicaid program on firmer financial footing ahead of the coming expansion in 2014 under the Affordable Care Act.

Right now, Arkansas’ Medicaid program is one of the few in the country that is actually solvent. But it won’t stay that way unless there are fundamental changes to how health care providers get paid, said Dr. Golden, also professor of medicine and public health at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock. By rethinking the way Medicaid pays for care, officials are hoping to avoid across the board cuts in providers’ pay or limits in beneficiaries’ eligibility, he said.

The program began in July with physicians getting report cards showing them how their 2011 performance might stack up under the new system. That past performance won’t count toward payment, but should give physicians an idea of whether they need to rethink some of their practices.

This fall, Medicaid will start collecting data; actual adjustments to pay won’t come for about a year.

The private payers involved in the gainsharing project – Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield and Arkansas QualChoice – will start their data collection in January 2013.

All together, about 1 million Arkansans will be affected by the program, Dr. Golden estimated.

Physicians have greeted the program with skepticism, mostly due to initial, confusing reports about what would be involved. When the program was first announced in 2011, it was billed as a bundling initiative that would have awarded a single payment to a group of physicians and would have let them figure out how to divide it.

Those bundling discussions left everyone "terrified," Dr. Golden said. So Medicaid officials and their private sector partners agreed to move to a hybrid, accountable care program.

Dr. Lonnie Robinson, a family physician in Mountain Home, Ark., said he had some significant concerns back when the program called for bundling payments. "That sounded like a recipe for strife and a food fight," he said.

Dr. Robinson said he doesn’t expect any major changes in his day-to-day operations, unless significant data entry is involved. Right now, most data will be taken from claims, though physicians may be asked to submit additional information for the attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, hip and knee replacement, and congestive heart failure episodes.

For primary care, the upper respiratory infection episodes are likely to have the biggest impact, Dr. Robinson said. He said he’s excited about the program’s emphasis on not prescribing antibiotics unnecessarily.

"That’s something I’ve been preaching to my patients since I’ve been in practice," Dr. Robinson said. "Now I have the backup of the payer to say not only do I not think it’s indicated, they don’t really want to pay for it."

But from a financial perspective, this program won’t touch too many doctors, he said.

"I feel that most physicians who are practicing mainstream medicine are probably not going to be affected by this," Dr. Robinson said. "It’s going to be people that are on the fringe as far as high cost per episode that are probably going to have to make some adjustments."

David Wroten, executive vice president of the Arkansas Medical Society, agreed that most physicians aren’t at risk for penalties. With upper respiratory infections, the physicians who could be in trouble are those who are routinely prescribe antibiotics, or routinely order labs and x-rays, or inappropriately upcode for the office visit.

"This is going to spotlight those folks," Mr. Wroten said.

He expressed concern about the perinatal episode of care. Some physicians have a higher cesarean delivery rate, which drives up their costs, but there is no evidence to show that it’s unnecessary, Mr. Wroten said.

Going forward, Medicaid and the other payers plan to expand the number of episodes of care included in the program. Episodes involved in long-term care are on their agenda, Dr. Golden said. They are also working on how they could potentially pay physicians more for providing a patient-centered medical home, he said.

Not all doctors will benefit, even if they provide a portion of the treatment for a particular episode of care in these areas. As part of the program, the payers will identify a principal accountable provider (PAP) who is the main source of care. For instance, with an upper respiratory infection, the PAP is likely to be the primary care provider. For heart failure, the PAP likely would be the hospital where the patient was first admitted.

Even though the PAP directly controls only a portion of the spending for the episode of care, he or she is responsible for the global cost of that episode. For example, for an upper respiratory infection, the episode would begin with the initial office visit and would include all follow-up care for the next 21 days. The global cost includes office visits, labs, imaging, and any prescribed medications.

The idea is that other providers who may be involved in the episode – perhaps a radiologist or a pharmacist – are passive players, according to Dr. Golden. The PAP, who acts as a quarterback for the patient’s care, is responsible for holding down the overall costs.

For most physicians, the program won’t make a difference in their bottom lines. Medicaid and the private insurers will continue to use the traditional fee-for-service system. For the five episodes of care, the payers will set thresholds for appropriate spending, ranging from "acceptable" to "commendable." Based on claims data, the payers will retrospectively review spending and identify those physicians who are outliers.

Physicians whose average costs for a particular episode of care exceed the "acceptable" cost level will have to return a portion of the extra fees, likely about half, according to Dr. Golden. However, there will be a limit on how much physicians have to pay back to ensure that the penalties aren’t excessive, he said.

Those with costs that are lower than the "commendable" level will share about half of the savings they have generated. Those in the middle won’t see any change in payment.

Very-high-cost patient events will be excluded when calculating an average cost of care, Dr. Golden said. For instance, with upper respiratory infection episodes, infants and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease could be excluded from the calculations.

Each of the participating payers will apply the program slightly differently. For example, Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield will start off with just three episodes of care: perinatal care, hip and knee replacement, and heart failure.

Want to be paid extra for providing appropriate, cost-effective medical care? Doctors in Arkansas are about to find out what that’s all about as the state’s Medicaid program – along with two private insurance companies – kicks off a gainsharing program.

Under Arkansas’s Health Care Payment Improvement Initiative, health care payers have asked physicians and hospitals to keep costs for five high-volume episodes of care while still meeting quality standards. The episodes of care are perinatal care, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, upper respiratory infection, hip and knee replacement, and heart failure.

If providers succeed, they can share in the money saved by the insurers. If they don’t, they’ll need to return some of the excess fees.

"If you provide a service and you can do it with quality standards and good outcomes and do it less expensively than the other guy, we’re going to give you a bonus. The better doctors should do well," said Dr. William E. Golden, medical director of the Arkansas Medicaid program.

Other states, especially rural ones, will be watching how things play out in Arkansas, Dr. Golden said. "Everybody is going in this direction. We’ve just bitten off more of the apple faster than most."

The shift from simply paying for services provided to a cost-and-quality approach was undertaken in part to put the state’s Medicaid program on firmer financial footing ahead of the coming expansion in 2014 under the Affordable Care Act.

Right now, Arkansas’ Medicaid program is one of the few in the country that is actually solvent. But it won’t stay that way unless there are fundamental changes to how health care providers get paid, said Dr. Golden, also professor of medicine and public health at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock. By rethinking the way Medicaid pays for care, officials are hoping to avoid across the board cuts in providers’ pay or limits in beneficiaries’ eligibility, he said.

The program began in July with physicians getting report cards showing them how their 2011 performance might stack up under the new system. That past performance won’t count toward payment, but should give physicians an idea of whether they need to rethink some of their practices.

This fall, Medicaid will start collecting data; actual adjustments to pay won’t come for about a year.

The private payers involved in the gainsharing project – Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield and Arkansas QualChoice – will start their data collection in January 2013.

All together, about 1 million Arkansans will be affected by the program, Dr. Golden estimated.

Physicians have greeted the program with skepticism, mostly due to initial, confusing reports about what would be involved. When the program was first announced in 2011, it was billed as a bundling initiative that would have awarded a single payment to a group of physicians and would have let them figure out how to divide it.

Those bundling discussions left everyone "terrified," Dr. Golden said. So Medicaid officials and their private sector partners agreed to move to a hybrid, accountable care program.

Dr. Lonnie Robinson, a family physician in Mountain Home, Ark., said he had some significant concerns back when the program called for bundling payments. "That sounded like a recipe for strife and a food fight," he said.

Dr. Robinson said he doesn’t expect any major changes in his day-to-day operations, unless significant data entry is involved. Right now, most data will be taken from claims, though physicians may be asked to submit additional information for the attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, hip and knee replacement, and congestive heart failure episodes.

For primary care, the upper respiratory infection episodes are likely to have the biggest impact, Dr. Robinson said. He said he’s excited about the program’s emphasis on not prescribing antibiotics unnecessarily.

"That’s something I’ve been preaching to my patients since I’ve been in practice," Dr. Robinson said. "Now I have the backup of the payer to say not only do I not think it’s indicated, they don’t really want to pay for it."

But from a financial perspective, this program won’t touch too many doctors, he said.

"I feel that most physicians who are practicing mainstream medicine are probably not going to be affected by this," Dr. Robinson said. "It’s going to be people that are on the fringe as far as high cost per episode that are probably going to have to make some adjustments."

David Wroten, executive vice president of the Arkansas Medical Society, agreed that most physicians aren’t at risk for penalties. With upper respiratory infections, the physicians who could be in trouble are those who are routinely prescribe antibiotics, or routinely order labs and x-rays, or inappropriately upcode for the office visit.

"This is going to spotlight those folks," Mr. Wroten said.

He expressed concern about the perinatal episode of care. Some physicians have a higher cesarean delivery rate, which drives up their costs, but there is no evidence to show that it’s unnecessary, Mr. Wroten said.

Going forward, Medicaid and the other payers plan to expand the number of episodes of care included in the program. Episodes involved in long-term care are on their agenda, Dr. Golden said. They are also working on how they could potentially pay physicians more for providing a patient-centered medical home, he said.

Not all doctors will benefit, even if they provide a portion of the treatment for a particular episode of care in these areas. As part of the program, the payers will identify a principal accountable provider (PAP) who is the main source of care. For instance, with an upper respiratory infection, the PAP is likely to be the primary care provider. For heart failure, the PAP likely would be the hospital where the patient was first admitted.

Even though the PAP directly controls only a portion of the spending for the episode of care, he or she is responsible for the global cost of that episode. For example, for an upper respiratory infection, the episode would begin with the initial office visit and would include all follow-up care for the next 21 days. The global cost includes office visits, labs, imaging, and any prescribed medications.

The idea is that other providers who may be involved in the episode – perhaps a radiologist or a pharmacist – are passive players, according to Dr. Golden. The PAP, who acts as a quarterback for the patient’s care, is responsible for holding down the overall costs.

For most physicians, the program won’t make a difference in their bottom lines. Medicaid and the private insurers will continue to use the traditional fee-for-service system. For the five episodes of care, the payers will set thresholds for appropriate spending, ranging from "acceptable" to "commendable." Based on claims data, the payers will retrospectively review spending and identify those physicians who are outliers.

Physicians whose average costs for a particular episode of care exceed the "acceptable" cost level will have to return a portion of the extra fees, likely about half, according to Dr. Golden. However, there will be a limit on how much physicians have to pay back to ensure that the penalties aren’t excessive, he said.

Those with costs that are lower than the "commendable" level will share about half of the savings they have generated. Those in the middle won’t see any change in payment.

Very-high-cost patient events will be excluded when calculating an average cost of care, Dr. Golden said. For instance, with upper respiratory infection episodes, infants and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease could be excluded from the calculations.

Each of the participating payers will apply the program slightly differently. For example, Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield will start off with just three episodes of care: perinatal care, hip and knee replacement, and heart failure.

Want to be paid extra for providing appropriate, cost-effective medical care? Doctors in Arkansas are about to find out what that’s all about as the state’s Medicaid program – along with two private insurance companies – kicks off a gainsharing program.

Under Arkansas’s Health Care Payment Improvement Initiative, health care payers have asked physicians and hospitals to keep costs for five high-volume episodes of care while still meeting quality standards. The episodes of care are perinatal care, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, upper respiratory infection, hip and knee replacement, and heart failure.

If providers succeed, they can share in the money saved by the insurers. If they don’t, they’ll need to return some of the excess fees.

"If you provide a service and you can do it with quality standards and good outcomes and do it less expensively than the other guy, we’re going to give you a bonus. The better doctors should do well," said Dr. William E. Golden, medical director of the Arkansas Medicaid program.

Other states, especially rural ones, will be watching how things play out in Arkansas, Dr. Golden said. "Everybody is going in this direction. We’ve just bitten off more of the apple faster than most."

The shift from simply paying for services provided to a cost-and-quality approach was undertaken in part to put the state’s Medicaid program on firmer financial footing ahead of the coming expansion in 2014 under the Affordable Care Act.

Right now, Arkansas’ Medicaid program is one of the few in the country that is actually solvent. But it won’t stay that way unless there are fundamental changes to how health care providers get paid, said Dr. Golden, also professor of medicine and public health at the University of Arkansas, Little Rock. By rethinking the way Medicaid pays for care, officials are hoping to avoid across the board cuts in providers’ pay or limits in beneficiaries’ eligibility, he said.

The program began in July with physicians getting report cards showing them how their 2011 performance might stack up under the new system. That past performance won’t count toward payment, but should give physicians an idea of whether they need to rethink some of their practices.

This fall, Medicaid will start collecting data; actual adjustments to pay won’t come for about a year.

The private payers involved in the gainsharing project – Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield and Arkansas QualChoice – will start their data collection in January 2013.

All together, about 1 million Arkansans will be affected by the program, Dr. Golden estimated.

Physicians have greeted the program with skepticism, mostly due to initial, confusing reports about what would be involved. When the program was first announced in 2011, it was billed as a bundling initiative that would have awarded a single payment to a group of physicians and would have let them figure out how to divide it.

Those bundling discussions left everyone "terrified," Dr. Golden said. So Medicaid officials and their private sector partners agreed to move to a hybrid, accountable care program.

Dr. Lonnie Robinson, a family physician in Mountain Home, Ark., said he had some significant concerns back when the program called for bundling payments. "That sounded like a recipe for strife and a food fight," he said.

Dr. Robinson said he doesn’t expect any major changes in his day-to-day operations, unless significant data entry is involved. Right now, most data will be taken from claims, though physicians may be asked to submit additional information for the attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, hip and knee replacement, and congestive heart failure episodes.

For primary care, the upper respiratory infection episodes are likely to have the biggest impact, Dr. Robinson said. He said he’s excited about the program’s emphasis on not prescribing antibiotics unnecessarily.

"That’s something I’ve been preaching to my patients since I’ve been in practice," Dr. Robinson said. "Now I have the backup of the payer to say not only do I not think it’s indicated, they don’t really want to pay for it."

But from a financial perspective, this program won’t touch too many doctors, he said.

"I feel that most physicians who are practicing mainstream medicine are probably not going to be affected by this," Dr. Robinson said. "It’s going to be people that are on the fringe as far as high cost per episode that are probably going to have to make some adjustments."

David Wroten, executive vice president of the Arkansas Medical Society, agreed that most physicians aren’t at risk for penalties. With upper respiratory infections, the physicians who could be in trouble are those who are routinely prescribe antibiotics, or routinely order labs and x-rays, or inappropriately upcode for the office visit.

"This is going to spotlight those folks," Mr. Wroten said.

He expressed concern about the perinatal episode of care. Some physicians have a higher cesarean delivery rate, which drives up their costs, but there is no evidence to show that it’s unnecessary, Mr. Wroten said.

Going forward, Medicaid and the other payers plan to expand the number of episodes of care included in the program. Episodes involved in long-term care are on their agenda, Dr. Golden said. They are also working on how they could potentially pay physicians more for providing a patient-centered medical home, he said.

Not all doctors will benefit, even if they provide a portion of the treatment for a particular episode of care in these areas. As part of the program, the payers will identify a principal accountable provider (PAP) who is the main source of care. For instance, with an upper respiratory infection, the PAP is likely to be the primary care provider. For heart failure, the PAP likely would be the hospital where the patient was first admitted.

Even though the PAP directly controls only a portion of the spending for the episode of care, he or she is responsible for the global cost of that episode. For example, for an upper respiratory infection, the episode would begin with the initial office visit and would include all follow-up care for the next 21 days. The global cost includes office visits, labs, imaging, and any prescribed medications.

The idea is that other providers who may be involved in the episode – perhaps a radiologist or a pharmacist – are passive players, according to Dr. Golden. The PAP, who acts as a quarterback for the patient’s care, is responsible for holding down the overall costs.

For most physicians, the program won’t make a difference in their bottom lines. Medicaid and the private insurers will continue to use the traditional fee-for-service system. For the five episodes of care, the payers will set thresholds for appropriate spending, ranging from "acceptable" to "commendable." Based on claims data, the payers will retrospectively review spending and identify those physicians who are outliers.

Physicians whose average costs for a particular episode of care exceed the "acceptable" cost level will have to return a portion of the extra fees, likely about half, according to Dr. Golden. However, there will be a limit on how much physicians have to pay back to ensure that the penalties aren’t excessive, he said.

Those with costs that are lower than the "commendable" level will share about half of the savings they have generated. Those in the middle won’t see any change in payment.

Very-high-cost patient events will be excluded when calculating an average cost of care, Dr. Golden said. For instance, with upper respiratory infection episodes, infants and patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease could be excluded from the calculations.

Each of the participating payers will apply the program slightly differently. For example, Arkansas Blue Cross Blue Shield will start off with just three episodes of care: perinatal care, hip and knee replacement, and heart failure.

Educator Pushes Evidence-Based Approach

Dr. Daniel D. Dressler has devoted the last several years to teaching medical students and residents to think critically about the medical literature and to embrace practicing in an evidence-based world. Dr. Dressler, who was the founding director of the hospital medicine program at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, currently serves as the university’s hospital medicine associate division director for education and oversees more than 120 hospitalists and 20 midlevel providers.

He directs the department of medicine’s evidence-based medicine curriculum and founded the evidence-based rapid fire track at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting.

In an interview, he shared his thoughts on the gaps in available evidence and the pitfalls of practicing based on anecdote.

QUESTION: Where are the gaps in evidence that impact hospitalist practice?

Dr. Dressler: Most clinical conditions have at least some evidence-based literature. Where practicing evidence-based medicine becomes more challenging is in remembering to do everything that is involved in evidence-based practice on a consistent basis, every time we see that kind of patient.

We all have limited memories and limited ability to do multiple tasks at once. So probably the biggest challenge with practicing in an evidence-based fashion is ensuring there are systems or structures in place to allow hospitalists to do those things. That’s why you see core measures around certain conditions to make sure that the evidence-based practice is happening.

The other piece where there are gaps in evidence has more to do with systems, such as transitions of care or the discharge process. What is the best way to discharge a patient to ensure they get the best follow-up care or the most efficient and effective care as they transition from place to place within the hospital? Those are areas where there are definitely gaps, though we’ve been gaining more data recently.

QUESTION: How do you incorporate evidence-based medicine into medical student and resident training?

Dr. Dressler: One of the main goals for trainees is to design well-structured clinical questions and be able to utilize available databases and literature to find the relevant information that’s available to answer those questions. Also, can they interpret that literature in a reasonable and efficient fashion? When I was learning about evidence-based medicine during my training in the late 1990s, it was more about, could we find a piece of literature and interpret it? Now there’s also a significant need to incorporate efficiency. The data suggests that if it takes you more than 2 to 3 minutes to find an answer to your question, you’re just going to stop looking.

QUESTION: Does technology make finding those answers easier?

Dr. Dressler: It is the classic double-edged sword. In some ways it is better because you have so much information at your fingertips. The other side is that resources that come to the top of search lists based on popularity aren’t necessarily the best available evidence to answer your clinical question.

QUESTION: Evidence-based medicine was once derided as cookbook medicine. How have attitudes changed over the years?

Dr. Dressler: Students and trainees are usually very open to the concept of evidence-based medicine because they don’t necessarily have any other preconceived notion of it. I understand that there are some individuals who have a perception of evidence-based medicine as "cookbook medicine."

However, evidence-based medicine is practiced not only using the randomized trials, but also incorporating any of the best available evidence, interpreting that evidence, and using it in conjunction with medical expertise, as well as patient preferences. Occasionally clinicians put too much emphasis on their own expertise. If a physician says, "The last five patients I saw with heart failure didn’t do well with a beta-blocker and I’m going to stop prescribing beta-blockers to patients with heart failure," that’s a misapplication of evidence-based medicine.

Practicing evidence-based medicine means accepting that in a clinical practice you can’t necessarily distinguish between a 2% or 3% or 5% difference in an outcome with different interventions. But those are real differences. Physicians should not be practicing based on anecdote or their experiences with the last two or three or five patients they saw. Instead, when there is robust, high-quality evidence to guide practice, physicians should utilize that randomized-controlled trial data or meta-analysis data, or even cohort or case control data, to guide and influence their daily practice for the betterment of the patients they treat.

Take us to your leader. Nominate a hospitalist whose work inspires you. E-mail suggestions to [email protected]. Read previous columns at ehospitalistnews.com.

Dr. Daniel D. Dressler has devoted the last several years to teaching medical students and residents to think critically about the medical literature and to embrace practicing in an evidence-based world. Dr. Dressler, who was the founding director of the hospital medicine program at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, currently serves as the university’s hospital medicine associate division director for education and oversees more than 120 hospitalists and 20 midlevel providers.

He directs the department of medicine’s evidence-based medicine curriculum and founded the evidence-based rapid fire track at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting.

In an interview, he shared his thoughts on the gaps in available evidence and the pitfalls of practicing based on anecdote.

QUESTION: Where are the gaps in evidence that impact hospitalist practice?

Dr. Dressler: Most clinical conditions have at least some evidence-based literature. Where practicing evidence-based medicine becomes more challenging is in remembering to do everything that is involved in evidence-based practice on a consistent basis, every time we see that kind of patient.

We all have limited memories and limited ability to do multiple tasks at once. So probably the biggest challenge with practicing in an evidence-based fashion is ensuring there are systems or structures in place to allow hospitalists to do those things. That’s why you see core measures around certain conditions to make sure that the evidence-based practice is happening.

The other piece where there are gaps in evidence has more to do with systems, such as transitions of care or the discharge process. What is the best way to discharge a patient to ensure they get the best follow-up care or the most efficient and effective care as they transition from place to place within the hospital? Those are areas where there are definitely gaps, though we’ve been gaining more data recently.

QUESTION: How do you incorporate evidence-based medicine into medical student and resident training?

Dr. Dressler: One of the main goals for trainees is to design well-structured clinical questions and be able to utilize available databases and literature to find the relevant information that’s available to answer those questions. Also, can they interpret that literature in a reasonable and efficient fashion? When I was learning about evidence-based medicine during my training in the late 1990s, it was more about, could we find a piece of literature and interpret it? Now there’s also a significant need to incorporate efficiency. The data suggests that if it takes you more than 2 to 3 minutes to find an answer to your question, you’re just going to stop looking.

QUESTION: Does technology make finding those answers easier?

Dr. Dressler: It is the classic double-edged sword. In some ways it is better because you have so much information at your fingertips. The other side is that resources that come to the top of search lists based on popularity aren’t necessarily the best available evidence to answer your clinical question.

QUESTION: Evidence-based medicine was once derided as cookbook medicine. How have attitudes changed over the years?

Dr. Dressler: Students and trainees are usually very open to the concept of evidence-based medicine because they don’t necessarily have any other preconceived notion of it. I understand that there are some individuals who have a perception of evidence-based medicine as "cookbook medicine."

However, evidence-based medicine is practiced not only using the randomized trials, but also incorporating any of the best available evidence, interpreting that evidence, and using it in conjunction with medical expertise, as well as patient preferences. Occasionally clinicians put too much emphasis on their own expertise. If a physician says, "The last five patients I saw with heart failure didn’t do well with a beta-blocker and I’m going to stop prescribing beta-blockers to patients with heart failure," that’s a misapplication of evidence-based medicine.

Practicing evidence-based medicine means accepting that in a clinical practice you can’t necessarily distinguish between a 2% or 3% or 5% difference in an outcome with different interventions. But those are real differences. Physicians should not be practicing based on anecdote or their experiences with the last two or three or five patients they saw. Instead, when there is robust, high-quality evidence to guide practice, physicians should utilize that randomized-controlled trial data or meta-analysis data, or even cohort or case control data, to guide and influence their daily practice for the betterment of the patients they treat.

Take us to your leader. Nominate a hospitalist whose work inspires you. E-mail suggestions to [email protected]. Read previous columns at ehospitalistnews.com.

Dr. Daniel D. Dressler has devoted the last several years to teaching medical students and residents to think critically about the medical literature and to embrace practicing in an evidence-based world. Dr. Dressler, who was the founding director of the hospital medicine program at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta, currently serves as the university’s hospital medicine associate division director for education and oversees more than 120 hospitalists and 20 midlevel providers.

He directs the department of medicine’s evidence-based medicine curriculum and founded the evidence-based rapid fire track at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual meeting.

In an interview, he shared his thoughts on the gaps in available evidence and the pitfalls of practicing based on anecdote.

QUESTION: Where are the gaps in evidence that impact hospitalist practice?

Dr. Dressler: Most clinical conditions have at least some evidence-based literature. Where practicing evidence-based medicine becomes more challenging is in remembering to do everything that is involved in evidence-based practice on a consistent basis, every time we see that kind of patient.

We all have limited memories and limited ability to do multiple tasks at once. So probably the biggest challenge with practicing in an evidence-based fashion is ensuring there are systems or structures in place to allow hospitalists to do those things. That’s why you see core measures around certain conditions to make sure that the evidence-based practice is happening.

The other piece where there are gaps in evidence has more to do with systems, such as transitions of care or the discharge process. What is the best way to discharge a patient to ensure they get the best follow-up care or the most efficient and effective care as they transition from place to place within the hospital? Those are areas where there are definitely gaps, though we’ve been gaining more data recently.

QUESTION: How do you incorporate evidence-based medicine into medical student and resident training?

Dr. Dressler: One of the main goals for trainees is to design well-structured clinical questions and be able to utilize available databases and literature to find the relevant information that’s available to answer those questions. Also, can they interpret that literature in a reasonable and efficient fashion? When I was learning about evidence-based medicine during my training in the late 1990s, it was more about, could we find a piece of literature and interpret it? Now there’s also a significant need to incorporate efficiency. The data suggests that if it takes you more than 2 to 3 minutes to find an answer to your question, you’re just going to stop looking.

QUESTION: Does technology make finding those answers easier?

Dr. Dressler: It is the classic double-edged sword. In some ways it is better because you have so much information at your fingertips. The other side is that resources that come to the top of search lists based on popularity aren’t necessarily the best available evidence to answer your clinical question.

QUESTION: Evidence-based medicine was once derided as cookbook medicine. How have attitudes changed over the years?

Dr. Dressler: Students and trainees are usually very open to the concept of evidence-based medicine because they don’t necessarily have any other preconceived notion of it. I understand that there are some individuals who have a perception of evidence-based medicine as "cookbook medicine."

However, evidence-based medicine is practiced not only using the randomized trials, but also incorporating any of the best available evidence, interpreting that evidence, and using it in conjunction with medical expertise, as well as patient preferences. Occasionally clinicians put too much emphasis on their own expertise. If a physician says, "The last five patients I saw with heart failure didn’t do well with a beta-blocker and I’m going to stop prescribing beta-blockers to patients with heart failure," that’s a misapplication of evidence-based medicine.

Practicing evidence-based medicine means accepting that in a clinical practice you can’t necessarily distinguish between a 2% or 3% or 5% difference in an outcome with different interventions. But those are real differences. Physicians should not be practicing based on anecdote or their experiences with the last two or three or five patients they saw. Instead, when there is robust, high-quality evidence to guide practice, physicians should utilize that randomized-controlled trial data or meta-analysis data, or even cohort or case control data, to guide and influence their daily practice for the betterment of the patients they treat.

Take us to your leader. Nominate a hospitalist whose work inspires you. E-mail suggestions to [email protected]. Read previous columns at ehospitalistnews.com.

Hospitals Partner, Experiment to Curb Readmissions

It’s a scenario with which hospitalists are quite familiar: Mrs. A is discharged from the hospital to a skilled nursing facility on a Friday night. On Saturday, she develops a deep cough and fever, but the nursing facility’s attending physician isn’t scheduled to round until Monday. So Mrs. A ends up back in the hospital.

Such a readmission could have been prevented – and now that Medicare’s readmission penalties are about to kick in, more hospitalists are investigating systems and models to help them improve their readmission rates.

Under the Affordable Care Act, Medicare will begin on Oct. 1 to penalize hospitals with excess readmission for pneumonia, heart failure, and myocardial infarction – up to 1% of their overall Medicare payments, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services recently announced. The penalty for this fiscal year (Oct. 1, 2012–Sept. 30, 2013) is based on hospital performance between July 2008 and June 2011, and is adjusted per hospital based on patient demographics, comorbidities, and frailty.

So, what’s a hospitalist to do to help lower the penalty going forward?

Focus on Skilled Nursing Facilities

Readmissions such as Mrs. A’s could be prevented if physicians had a stronger presence at the skilled nursing facility (SNF) level, according to Dr. Darius K. Joshi of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

At the University of Michigan Health System, a small team of geriatricians and nurse practitioners, led by Dr. Joshi, has been assigned to staff local SNFs 7 days a week. The goal is to discharge patients from the hospital to SNFs sooner and to keep them from being readmitted.

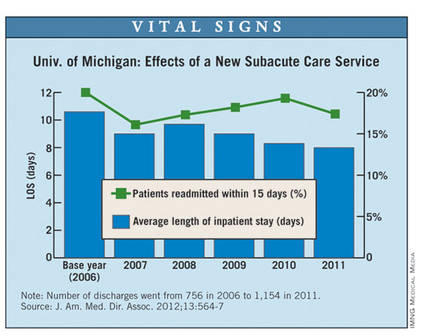

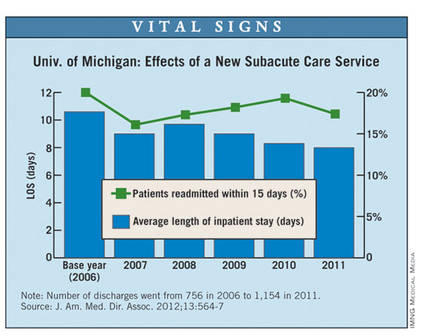

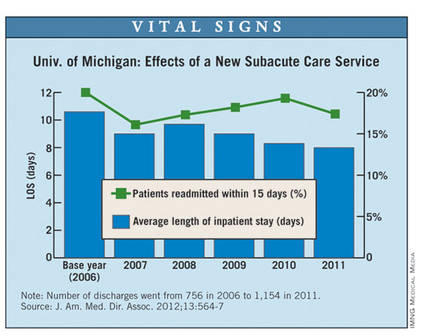

The subacute care program reduced the average hospital length of stay before transfer to an SNF from 10.6 days to 8 days between 2006 and 2011. The hospital’s 15-day readmission rates have also improved somewhat, dropping from 20% to 17% over the same period (J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2012;13:564-7).

"Being at the bedside, seeing these patients, knowing their history, having good laboratory tests available, avoids sending many of these patients back to the hospital," said Dr. Joshi of the geriatric medicine division at the University of Michigan, a former hospitalist who runs the subacute program.

Doctors and nurse practitioners practicing in the SNFs also have access to the health system’s electronic health record (EHR) system. This allows physicians at the SNF to understand the patient’s hospital care; it also transfers data on care provided at the SNF back to the hospital.

But even with this effort, the University of Michigan health system (which has invested in ways to prevent bounce-back to the hospital) will face a 0.64% cut under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program in FY 2013.

"[Readmissions are] a very, very resistant problem with our patients," Dr. Joshi explained.

Many times, families may insist that their loved ones go to the emergency department when their conditions worsen. In the case of falls, there is little alternative to returning to the hospital because most SNFs don’t have appropriate imaging equipment.

"There are limitations in what we can do, but if there’s any chance of cutting down readmissions, it needs to be with bedside presence," Dr. Joshi said.

Multidisciplinary Approach

At Sarasota (Fla.) Memorial Hospital, one focus in the fight to lower readmission rates is on heart failure.

The hospital established a heart failure center for ambulatory patients and instituted telemonitoring for nonambulatory patients who are discharged to home. A team of hospitalists, cardiologists, floor nurses, and home health care staff identifies high-risk heart failure patients, addresses their needs in the hospital, and arranges for follow-up care after discharge.

Sarasota Memorial Hospital is considered a standout when it comes to keeping readmission rates low. It was one of only two hospitals identified by CMS as having better-than-average readmission rates for all three assessed conditions.

The lion’s share of the credit for their success goes to the multidisciplinary culture of the health system, according to Dr. John Moritz, a hospitalist at Sarasota Memorial.