User login

Barriers and Job Satisfaction Among Dermatology Hospitalists

Consultative dermatologists, or dermatology hospitalists (DHs), perform a critical role in the care of inpatients with skin disease, providing efficient diagnosis and management of patients with complex skin conditions as well as education of patients and trainees in the hospital setting.1 In 2013, 27% of the US population was seen by a physician for a skin disease.2 In 2014, there were nearly 650,000 hospital admissions principally for skin disease.3 Input by dermatologists facilitates accurate diagnosis and management of inpatients with skin disease,4 including a substantial number of cutaneous malignancies diagnosed in the inpatient setting.5 Several studies have highlighted the generally low level of diagnostic concordance between referring services and dermatology consultants,4,6 with dermatology consultants frequently noting diagnoses not considered by referring services,7 reinforcing the importance of having access to dermatologists in the hospital setting.

The care of skin disease in the inpatient setting has become increasingly complex. The Society for Dermatology Hospitalists (SDH) was created in 2009 to address this complexity, with the goal to “strive to develop the highest standards of clinical care of hospitalized patients with skin disease.”8 A recent survey found that 50% of DHs spend between 41 to 52 weeks per year on service.9 Despite this degree of commitment, there are considerable barriers that prevent the majority of dermatologists from efficiently providing inpatient consultative care. The inpatient and outpatient provision of dermatology care varies greatly, including the variety of ethical situations encountered and the diversity of skin conditions treated.10-12 Additionally, the transition between inpatient and outpatient care can be challenging for providers.13

The goal of this study was to evaluate the overall job satisfaction of DHs and further describe potential barriers to inpatient dermatology consultations.

Methods

An anonymous 31-question electronic survey was sent via email to all current members of the SDH from November 20 to December 10, 2018. The study was reviewed and determined to be exempt from federal human subjects regulations by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division (Seattle, Washington)(STUDY00005832).

Results

At the time of survey distribution, the SDH had 145 members, including attending-level dermatologists and resident members. Thirty-seven self-identified DHs (46% [17/37] women; 54% [20/37] men) completed the survey. The majority of respondents were junior faculty, with 46% (17/37) assistant professors, 5% (2/37) acting instructors, 32% (12/37) associate professors, and 16% (6/37) professors. All regions of the United States were represented.

Time Dedicated to Providing Inpatient Dermatology Consultations

The majority of those surveyed were satisfied or very satisfied (68% [25/37]) with the amount of time allotted for inpatient dermatology consultations, while 14% (5/37) were unsatisfied or very unsatisfied. Of those surveyed, 46% (17/37) reported that 21% to 50% of their time is dedicated to inpatient dermatology consultations. The majority (57% [21/37]) reported that their outpatient clinic efforts are reduced when providing dermatology inpatient consultations.

Regarding travel to the inpatient practice site, 60% (22/37) rated their travel time/effort as very easy, with 38% (14/37) reporting that the sites at which they provide inpatient dermatology consultations and their main outpatient clinics are the same physical location; 38% (14/37) reported travel times of less than 15 minutes between clinical practice sites.

Eighty-nine percent (33/37) of respondents said they are able to spend more time teaching trainees when providing inpatient dermatology consultations compared to their time spent in clinic. Similarly, 70% (26/37) said they are able to spend more time learning about patients and their conditions when providing inpatient dermatology consultations. Respondents also reported additional time expenditures because of inpatient dermatology consultations, primarily additional teaching requirements (49% [18/37]), additional electronic medical record training (35% [13/37]), and credentialing requirements (24% [9/37]).

Infrastructure for Providing Inpatient Dermatology Consultations

For many respondents (30% [11/37]), only 2 faculty dermatologists regularly provide inpatient dermatology consultations at their institutions. Four respondents reported having at least 5 faculty dermatologists who regularly provide inpatient dermatology consultations; excluding these, the average number of DHs was 2.42 faculty per institution.

Most respondents (57% [21/37]) reported their institutions support inpatient dermatology services by providing salary support for residents to cover services. Other methods of support included dedicated office spaces (30% [11/37]), free hospital parking while providing inpatient consultations (24% [9/37]), and administrative support (11% [4/37]).

Consultation Composition

Respondents indicated that requests for DH consultations most often come from medical services, including medical intensive care, internal medicine, and family medicine (95% [35/37]); the emergency department (95% [35/37]); surgical services (92% [34/37]); and hematology/oncology (89% [33/37]). Fewer DHs reported receiving consultation requests from pediatrics (70% [26/37]).

Many respondents (49% [18/37]) reported consulting for patients with skin disorders that they considered to be life-threatening or potentially life-threatening either very frequently (daily) or frequently (several times weekly), with only 16% (6/37) responding that they see such patients about once per month.

Compensation for Inpatient Dermatology Consultation

The most commonly reported compensation models for DHs were fixed salary plus productivity or performance incentives and fixed salary only models (49% [18/37] and 32% [12/37], respectively), with relative value unit (RVU) models and other models less frequently reported (16% [6/37] and 3% [1/37], respectively). Only 46% (17/37) of respondents were satisfied or very satisfied with their institutions’ compensation models; the remainder (54% [20/37]) were either neutral, unsatisfied, or very unsatisfied regarding their institutions’ compensation models. Overall compensation satisfaction was higher, with 60% (22/37) of DHs reporting they were satisfied or very satisfied with their salaries and 41% (15/37) reporting they were either neutral or not satisfied. The majority (60% [2/37]) of respondents felt that fixed salary plus productivity or performance incentives models would be the ideal compensation model for DHs.

Of the DHs whose compensations models were RVU based (6/37 [16%]), 67% (4/6) said they receive incentive pay upon meeting their RVU targets. No respondents reported that they were expected to generate an equivalent number of RVUs when performing inpatient consultations as compared to an outpatient session. Only 32% (12/37) of respondents reported keeping the revenue/RVUs generated by inpatient dermatology consultations; most (57% [21/37]) noted that their dermatology divisions/departments keep the revenue/RVUs, followed by university hospitals (27% [10/37]), schools of medicine (11% [4/37]), and departments of medicine (3% [1/37]). The remainder of respondents (22% [8/37]) were unsure who keeps the revenue/RVUs generated by inpatient dermatology consultations.

Most respondents (70% [26/37]) reported that the revenue (or RVU equivalent) generated by inpatient dermatology consultations does not fully support their salary for the time spent as consultants. Rather, these DHs noted sources of additional financial support, primarily the DHs themselves (69% [18/26]), followed by dermatology divisions/departments (50% [13/26]), departments of medicine (23% [6/26]), university hospitals (23% [6/26]), and schools of medicine (12% [3/26]).

Job Fulfillment Among DHs

Most respondents said they choose to provide inpatient dermatology consultations due to their interest in complex medical dermatology and their desire to work with other medical teams and specialties (92% [34/37] and 76% [28/37], respectively). Seventy percent (26/37) said they choose to provide inpatient consultations to be able to teach medical students and residents as well as to take advantage of the added opportunities to practice in a variety of settings beyond their outpatient clinics (57% [21/37]). Only 3% (1/37) of respondents reported that they provide inpatient dermatology consultations because they are “required to do so.”

Most DHs (84% [31/37]) said they feel their institutions as well as their dermatology divisions/departments value having access to inpatient dermatology services, though some did not feel this way (16% [6/37] neutral or strongly disagree). Nearly all respondents (97% [36/37]) felt they provide a critical service when performing inpatient dermatology consultations. All respondents (100%) said they found providing inpatient dermatology consultations fulfilling, and 65% (24/37) said they prefer providing inpatient dermatology consultations to spending time in clinic. Of the DHs who were surveyed, 68% (25/37) said they were satisfied with the balance of outpatient and inpatient services in their clinical practice and 30% (11/37) said they were not.

Comment

Factors such as patient care, hospital infrastructure, and procedural support have all been cited by DHs as crucial aspects of their contributions to the care of hospitalized pa

Dermatology is primarily an outpatient specialty, and our study highlighted several important challenges for providers performing inpatient dermatology consultations. A major issue is time expenditures, including additional teaching requirements, additional electronic medical record training, and credentialing requirements. Travel time to inpatient hospital sites does not appear to be one of these hindering factors; nearly 60% of respondents rated their travel time/effort as very easy, with approximately 75% of respondents’ consultation locations being either at the same physical location as their main outpatient clinic or less than 15 minutes away. Maintaining easy travel between outpatient and inpatient settings is important to the success of the DH.

Our data suggest that compensation of DHs is a potential limitation to providing inpatient dermatology care. Our survey reinforced that providers who do inpatient dermatology consultations generally do not generate the revenue necessary to cover these efforts. More than 40% of DH respondents said they either feel neutral about or unsatisfied with their overall salary, and more than half said they feel similarly regarding their institutions’ compensation models. Most respondents said that a fixed salary model plus productivity or performance incentives is the ideal compensation model for those providing inpatient dermatology consultations, though only half said they actually are compensated according to this model. This discrepancy highlights the disconnect between the current accepted compensation models and the DH’s ideal model and provides direction for dermatology chairs and division heads as to what compensation model is preferable to support the success of DHs at their institutions.

Despite the barriers and compensation constraints we identified, DHs report high job satisfaction, which we hypothesize could combat burnout. In our study, all DHs surveyed say they find providing inpatient dermatology consultations fulfilling, and most were satisfied with the amount of time allotted for consultations. Some of the possible reasons why DHs may find their work fulfilling include increased time for teaching trainees and learning about patients and their conditions while consulting, as well as a preference for providing inpatient dermatology consultations to spending time in clinic. Most DHs said they choose to provide inpatient dermatology consultation rather than do so as a requirement, primarily due to their interest in complex medical dermatology and their desire to work with other medical teams/specialties; thankfully, only a small percentage said they provide these consultations because they are required to do so.

This study was conducted to analyze job satisfaction among DHs who provided inpatient dermatology consultations and determine common barriers and obstacles to their job satisfaction. Limitations to our study included the small sample size and the possibly limited representation of the intended population, as only the members of the SDH were surveyed, potentially excluding providers who regularly perform inpatient dermatology consultations but are not members of the SDH. Further limitations included recall bias and the qualitative nature of the survey instrument.

Final Thoughts

There was near-unanimous agreement among the DHs we surveyed regarding the importance of the role they play in their divisions/departments, but there are clear barriers to provision of inpatient dermatology consultation, specifically relating to extraneous time expenditures and compensation. Despite these barriers, the majority of respondents said they are very satisfied with the role they play in the inpatient setting and feel that their contributions are valued by the institutions where they work. Protecting these benefits of providing dermatology hospital consultations will be critical for maintaining this high job satisfaction and balancing out the barriers to providing these consultations. Protecting the time required to provide consultations is paramount so DHs continue to gain fulfillment from teaching trainees, caring for complex patients, and maintaining their place as valuable colleagues in the hospital setting.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the members of the SDH for their participation in this survey.

- Biesbroeck LK, Shinohara MM. Inpatient consultative dermatology. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:1349-1364.

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.e2.

- Arnold JD, Yoon SJ, Kirkorian AY. The national burden of inpatient dermatology in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;80:425-432.

- Mancusi S, Festa Neto C. Inpatient dermatological consultations in a university hospital. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65:851-855.

- Tsai S, Scott JF, Keller JJ, et al. Cutaneous malignancies identified in an inpatient dermatology consultation service. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:e116-e118.

- Pereira AR, Porro AM, Seque CA, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultations in renal transplant recipients. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:900-907.

- Tracey EH, Forrestel A, Rosenbach M, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:835-836.

- Fox LP, Cotliar J, Hughey L, et al. Hospitalist dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:153-154.

- Ko LN, Kroshinsky D. Dermatology hospitalists: a multicenter survey study characterizing the infrastructure of consultative dermatology in select American hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:553-558.

- Hansra NK, Shinkai K, Fox LP. Ethical issues in inpatient consultative dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:496-500.

- El-Azhary R, Weenig RH, Gibson LE. The dermatology hospitalist: creating value by rapid clinical pathologic correlation in a patient-centered care model. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1461-1466.

- Ahronowitz I, Fox LP. Herpes zoster in hospitalized adults: practice gaps, new evidence, and remaining questions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:223-230.e3.

- Rosenbach M. The logistics of an inpatient dermatology service. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:3-8.

- Ackerman L, Kessler M. The efficient, effective community hospital inpatient dermatology consult. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:9-11.

Consultative dermatologists, or dermatology hospitalists (DHs), perform a critical role in the care of inpatients with skin disease, providing efficient diagnosis and management of patients with complex skin conditions as well as education of patients and trainees in the hospital setting.1 In 2013, 27% of the US population was seen by a physician for a skin disease.2 In 2014, there were nearly 650,000 hospital admissions principally for skin disease.3 Input by dermatologists facilitates accurate diagnosis and management of inpatients with skin disease,4 including a substantial number of cutaneous malignancies diagnosed in the inpatient setting.5 Several studies have highlighted the generally low level of diagnostic concordance between referring services and dermatology consultants,4,6 with dermatology consultants frequently noting diagnoses not considered by referring services,7 reinforcing the importance of having access to dermatologists in the hospital setting.

The care of skin disease in the inpatient setting has become increasingly complex. The Society for Dermatology Hospitalists (SDH) was created in 2009 to address this complexity, with the goal to “strive to develop the highest standards of clinical care of hospitalized patients with skin disease.”8 A recent survey found that 50% of DHs spend between 41 to 52 weeks per year on service.9 Despite this degree of commitment, there are considerable barriers that prevent the majority of dermatologists from efficiently providing inpatient consultative care. The inpatient and outpatient provision of dermatology care varies greatly, including the variety of ethical situations encountered and the diversity of skin conditions treated.10-12 Additionally, the transition between inpatient and outpatient care can be challenging for providers.13

The goal of this study was to evaluate the overall job satisfaction of DHs and further describe potential barriers to inpatient dermatology consultations.

Methods

An anonymous 31-question electronic survey was sent via email to all current members of the SDH from November 20 to December 10, 2018. The study was reviewed and determined to be exempt from federal human subjects regulations by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division (Seattle, Washington)(STUDY00005832).

Results

At the time of survey distribution, the SDH had 145 members, including attending-level dermatologists and resident members. Thirty-seven self-identified DHs (46% [17/37] women; 54% [20/37] men) completed the survey. The majority of respondents were junior faculty, with 46% (17/37) assistant professors, 5% (2/37) acting instructors, 32% (12/37) associate professors, and 16% (6/37) professors. All regions of the United States were represented.

Time Dedicated to Providing Inpatient Dermatology Consultations

The majority of those surveyed were satisfied or very satisfied (68% [25/37]) with the amount of time allotted for inpatient dermatology consultations, while 14% (5/37) were unsatisfied or very unsatisfied. Of those surveyed, 46% (17/37) reported that 21% to 50% of their time is dedicated to inpatient dermatology consultations. The majority (57% [21/37]) reported that their outpatient clinic efforts are reduced when providing dermatology inpatient consultations.

Regarding travel to the inpatient practice site, 60% (22/37) rated their travel time/effort as very easy, with 38% (14/37) reporting that the sites at which they provide inpatient dermatology consultations and their main outpatient clinics are the same physical location; 38% (14/37) reported travel times of less than 15 minutes between clinical practice sites.

Eighty-nine percent (33/37) of respondents said they are able to spend more time teaching trainees when providing inpatient dermatology consultations compared to their time spent in clinic. Similarly, 70% (26/37) said they are able to spend more time learning about patients and their conditions when providing inpatient dermatology consultations. Respondents also reported additional time expenditures because of inpatient dermatology consultations, primarily additional teaching requirements (49% [18/37]), additional electronic medical record training (35% [13/37]), and credentialing requirements (24% [9/37]).

Infrastructure for Providing Inpatient Dermatology Consultations

For many respondents (30% [11/37]), only 2 faculty dermatologists regularly provide inpatient dermatology consultations at their institutions. Four respondents reported having at least 5 faculty dermatologists who regularly provide inpatient dermatology consultations; excluding these, the average number of DHs was 2.42 faculty per institution.

Most respondents (57% [21/37]) reported their institutions support inpatient dermatology services by providing salary support for residents to cover services. Other methods of support included dedicated office spaces (30% [11/37]), free hospital parking while providing inpatient consultations (24% [9/37]), and administrative support (11% [4/37]).

Consultation Composition

Respondents indicated that requests for DH consultations most often come from medical services, including medical intensive care, internal medicine, and family medicine (95% [35/37]); the emergency department (95% [35/37]); surgical services (92% [34/37]); and hematology/oncology (89% [33/37]). Fewer DHs reported receiving consultation requests from pediatrics (70% [26/37]).

Many respondents (49% [18/37]) reported consulting for patients with skin disorders that they considered to be life-threatening or potentially life-threatening either very frequently (daily) or frequently (several times weekly), with only 16% (6/37) responding that they see such patients about once per month.

Compensation for Inpatient Dermatology Consultation

The most commonly reported compensation models for DHs were fixed salary plus productivity or performance incentives and fixed salary only models (49% [18/37] and 32% [12/37], respectively), with relative value unit (RVU) models and other models less frequently reported (16% [6/37] and 3% [1/37], respectively). Only 46% (17/37) of respondents were satisfied or very satisfied with their institutions’ compensation models; the remainder (54% [20/37]) were either neutral, unsatisfied, or very unsatisfied regarding their institutions’ compensation models. Overall compensation satisfaction was higher, with 60% (22/37) of DHs reporting they were satisfied or very satisfied with their salaries and 41% (15/37) reporting they were either neutral or not satisfied. The majority (60% [2/37]) of respondents felt that fixed salary plus productivity or performance incentives models would be the ideal compensation model for DHs.

Of the DHs whose compensations models were RVU based (6/37 [16%]), 67% (4/6) said they receive incentive pay upon meeting their RVU targets. No respondents reported that they were expected to generate an equivalent number of RVUs when performing inpatient consultations as compared to an outpatient session. Only 32% (12/37) of respondents reported keeping the revenue/RVUs generated by inpatient dermatology consultations; most (57% [21/37]) noted that their dermatology divisions/departments keep the revenue/RVUs, followed by university hospitals (27% [10/37]), schools of medicine (11% [4/37]), and departments of medicine (3% [1/37]). The remainder of respondents (22% [8/37]) were unsure who keeps the revenue/RVUs generated by inpatient dermatology consultations.

Most respondents (70% [26/37]) reported that the revenue (or RVU equivalent) generated by inpatient dermatology consultations does not fully support their salary for the time spent as consultants. Rather, these DHs noted sources of additional financial support, primarily the DHs themselves (69% [18/26]), followed by dermatology divisions/departments (50% [13/26]), departments of medicine (23% [6/26]), university hospitals (23% [6/26]), and schools of medicine (12% [3/26]).

Job Fulfillment Among DHs

Most respondents said they choose to provide inpatient dermatology consultations due to their interest in complex medical dermatology and their desire to work with other medical teams and specialties (92% [34/37] and 76% [28/37], respectively). Seventy percent (26/37) said they choose to provide inpatient consultations to be able to teach medical students and residents as well as to take advantage of the added opportunities to practice in a variety of settings beyond their outpatient clinics (57% [21/37]). Only 3% (1/37) of respondents reported that they provide inpatient dermatology consultations because they are “required to do so.”

Most DHs (84% [31/37]) said they feel their institutions as well as their dermatology divisions/departments value having access to inpatient dermatology services, though some did not feel this way (16% [6/37] neutral or strongly disagree). Nearly all respondents (97% [36/37]) felt they provide a critical service when performing inpatient dermatology consultations. All respondents (100%) said they found providing inpatient dermatology consultations fulfilling, and 65% (24/37) said they prefer providing inpatient dermatology consultations to spending time in clinic. Of the DHs who were surveyed, 68% (25/37) said they were satisfied with the balance of outpatient and inpatient services in their clinical practice and 30% (11/37) said they were not.

Comment

Factors such as patient care, hospital infrastructure, and procedural support have all been cited by DHs as crucial aspects of their contributions to the care of hospitalized pa

Dermatology is primarily an outpatient specialty, and our study highlighted several important challenges for providers performing inpatient dermatology consultations. A major issue is time expenditures, including additional teaching requirements, additional electronic medical record training, and credentialing requirements. Travel time to inpatient hospital sites does not appear to be one of these hindering factors; nearly 60% of respondents rated their travel time/effort as very easy, with approximately 75% of respondents’ consultation locations being either at the same physical location as their main outpatient clinic or less than 15 minutes away. Maintaining easy travel between outpatient and inpatient settings is important to the success of the DH.

Our data suggest that compensation of DHs is a potential limitation to providing inpatient dermatology care. Our survey reinforced that providers who do inpatient dermatology consultations generally do not generate the revenue necessary to cover these efforts. More than 40% of DH respondents said they either feel neutral about or unsatisfied with their overall salary, and more than half said they feel similarly regarding their institutions’ compensation models. Most respondents said that a fixed salary model plus productivity or performance incentives is the ideal compensation model for those providing inpatient dermatology consultations, though only half said they actually are compensated according to this model. This discrepancy highlights the disconnect between the current accepted compensation models and the DH’s ideal model and provides direction for dermatology chairs and division heads as to what compensation model is preferable to support the success of DHs at their institutions.

Despite the barriers and compensation constraints we identified, DHs report high job satisfaction, which we hypothesize could combat burnout. In our study, all DHs surveyed say they find providing inpatient dermatology consultations fulfilling, and most were satisfied with the amount of time allotted for consultations. Some of the possible reasons why DHs may find their work fulfilling include increased time for teaching trainees and learning about patients and their conditions while consulting, as well as a preference for providing inpatient dermatology consultations to spending time in clinic. Most DHs said they choose to provide inpatient dermatology consultation rather than do so as a requirement, primarily due to their interest in complex medical dermatology and their desire to work with other medical teams/specialties; thankfully, only a small percentage said they provide these consultations because they are required to do so.

This study was conducted to analyze job satisfaction among DHs who provided inpatient dermatology consultations and determine common barriers and obstacles to their job satisfaction. Limitations to our study included the small sample size and the possibly limited representation of the intended population, as only the members of the SDH were surveyed, potentially excluding providers who regularly perform inpatient dermatology consultations but are not members of the SDH. Further limitations included recall bias and the qualitative nature of the survey instrument.

Final Thoughts

There was near-unanimous agreement among the DHs we surveyed regarding the importance of the role they play in their divisions/departments, but there are clear barriers to provision of inpatient dermatology consultation, specifically relating to extraneous time expenditures and compensation. Despite these barriers, the majority of respondents said they are very satisfied with the role they play in the inpatient setting and feel that their contributions are valued by the institutions where they work. Protecting these benefits of providing dermatology hospital consultations will be critical for maintaining this high job satisfaction and balancing out the barriers to providing these consultations. Protecting the time required to provide consultations is paramount so DHs continue to gain fulfillment from teaching trainees, caring for complex patients, and maintaining their place as valuable colleagues in the hospital setting.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the members of the SDH for their participation in this survey.

Consultative dermatologists, or dermatology hospitalists (DHs), perform a critical role in the care of inpatients with skin disease, providing efficient diagnosis and management of patients with complex skin conditions as well as education of patients and trainees in the hospital setting.1 In 2013, 27% of the US population was seen by a physician for a skin disease.2 In 2014, there were nearly 650,000 hospital admissions principally for skin disease.3 Input by dermatologists facilitates accurate diagnosis and management of inpatients with skin disease,4 including a substantial number of cutaneous malignancies diagnosed in the inpatient setting.5 Several studies have highlighted the generally low level of diagnostic concordance between referring services and dermatology consultants,4,6 with dermatology consultants frequently noting diagnoses not considered by referring services,7 reinforcing the importance of having access to dermatologists in the hospital setting.

The care of skin disease in the inpatient setting has become increasingly complex. The Society for Dermatology Hospitalists (SDH) was created in 2009 to address this complexity, with the goal to “strive to develop the highest standards of clinical care of hospitalized patients with skin disease.”8 A recent survey found that 50% of DHs spend between 41 to 52 weeks per year on service.9 Despite this degree of commitment, there are considerable barriers that prevent the majority of dermatologists from efficiently providing inpatient consultative care. The inpatient and outpatient provision of dermatology care varies greatly, including the variety of ethical situations encountered and the diversity of skin conditions treated.10-12 Additionally, the transition between inpatient and outpatient care can be challenging for providers.13

The goal of this study was to evaluate the overall job satisfaction of DHs and further describe potential barriers to inpatient dermatology consultations.

Methods

An anonymous 31-question electronic survey was sent via email to all current members of the SDH from November 20 to December 10, 2018. The study was reviewed and determined to be exempt from federal human subjects regulations by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division (Seattle, Washington)(STUDY00005832).

Results

At the time of survey distribution, the SDH had 145 members, including attending-level dermatologists and resident members. Thirty-seven self-identified DHs (46% [17/37] women; 54% [20/37] men) completed the survey. The majority of respondents were junior faculty, with 46% (17/37) assistant professors, 5% (2/37) acting instructors, 32% (12/37) associate professors, and 16% (6/37) professors. All regions of the United States were represented.

Time Dedicated to Providing Inpatient Dermatology Consultations

The majority of those surveyed were satisfied or very satisfied (68% [25/37]) with the amount of time allotted for inpatient dermatology consultations, while 14% (5/37) were unsatisfied or very unsatisfied. Of those surveyed, 46% (17/37) reported that 21% to 50% of their time is dedicated to inpatient dermatology consultations. The majority (57% [21/37]) reported that their outpatient clinic efforts are reduced when providing dermatology inpatient consultations.

Regarding travel to the inpatient practice site, 60% (22/37) rated their travel time/effort as very easy, with 38% (14/37) reporting that the sites at which they provide inpatient dermatology consultations and their main outpatient clinics are the same physical location; 38% (14/37) reported travel times of less than 15 minutes between clinical practice sites.

Eighty-nine percent (33/37) of respondents said they are able to spend more time teaching trainees when providing inpatient dermatology consultations compared to their time spent in clinic. Similarly, 70% (26/37) said they are able to spend more time learning about patients and their conditions when providing inpatient dermatology consultations. Respondents also reported additional time expenditures because of inpatient dermatology consultations, primarily additional teaching requirements (49% [18/37]), additional electronic medical record training (35% [13/37]), and credentialing requirements (24% [9/37]).

Infrastructure for Providing Inpatient Dermatology Consultations

For many respondents (30% [11/37]), only 2 faculty dermatologists regularly provide inpatient dermatology consultations at their institutions. Four respondents reported having at least 5 faculty dermatologists who regularly provide inpatient dermatology consultations; excluding these, the average number of DHs was 2.42 faculty per institution.

Most respondents (57% [21/37]) reported their institutions support inpatient dermatology services by providing salary support for residents to cover services. Other methods of support included dedicated office spaces (30% [11/37]), free hospital parking while providing inpatient consultations (24% [9/37]), and administrative support (11% [4/37]).

Consultation Composition

Respondents indicated that requests for DH consultations most often come from medical services, including medical intensive care, internal medicine, and family medicine (95% [35/37]); the emergency department (95% [35/37]); surgical services (92% [34/37]); and hematology/oncology (89% [33/37]). Fewer DHs reported receiving consultation requests from pediatrics (70% [26/37]).

Many respondents (49% [18/37]) reported consulting for patients with skin disorders that they considered to be life-threatening or potentially life-threatening either very frequently (daily) or frequently (several times weekly), with only 16% (6/37) responding that they see such patients about once per month.

Compensation for Inpatient Dermatology Consultation

The most commonly reported compensation models for DHs were fixed salary plus productivity or performance incentives and fixed salary only models (49% [18/37] and 32% [12/37], respectively), with relative value unit (RVU) models and other models less frequently reported (16% [6/37] and 3% [1/37], respectively). Only 46% (17/37) of respondents were satisfied or very satisfied with their institutions’ compensation models; the remainder (54% [20/37]) were either neutral, unsatisfied, or very unsatisfied regarding their institutions’ compensation models. Overall compensation satisfaction was higher, with 60% (22/37) of DHs reporting they were satisfied or very satisfied with their salaries and 41% (15/37) reporting they were either neutral or not satisfied. The majority (60% [2/37]) of respondents felt that fixed salary plus productivity or performance incentives models would be the ideal compensation model for DHs.

Of the DHs whose compensations models were RVU based (6/37 [16%]), 67% (4/6) said they receive incentive pay upon meeting their RVU targets. No respondents reported that they were expected to generate an equivalent number of RVUs when performing inpatient consultations as compared to an outpatient session. Only 32% (12/37) of respondents reported keeping the revenue/RVUs generated by inpatient dermatology consultations; most (57% [21/37]) noted that their dermatology divisions/departments keep the revenue/RVUs, followed by university hospitals (27% [10/37]), schools of medicine (11% [4/37]), and departments of medicine (3% [1/37]). The remainder of respondents (22% [8/37]) were unsure who keeps the revenue/RVUs generated by inpatient dermatology consultations.

Most respondents (70% [26/37]) reported that the revenue (or RVU equivalent) generated by inpatient dermatology consultations does not fully support their salary for the time spent as consultants. Rather, these DHs noted sources of additional financial support, primarily the DHs themselves (69% [18/26]), followed by dermatology divisions/departments (50% [13/26]), departments of medicine (23% [6/26]), university hospitals (23% [6/26]), and schools of medicine (12% [3/26]).

Job Fulfillment Among DHs

Most respondents said they choose to provide inpatient dermatology consultations due to their interest in complex medical dermatology and their desire to work with other medical teams and specialties (92% [34/37] and 76% [28/37], respectively). Seventy percent (26/37) said they choose to provide inpatient consultations to be able to teach medical students and residents as well as to take advantage of the added opportunities to practice in a variety of settings beyond their outpatient clinics (57% [21/37]). Only 3% (1/37) of respondents reported that they provide inpatient dermatology consultations because they are “required to do so.”

Most DHs (84% [31/37]) said they feel their institutions as well as their dermatology divisions/departments value having access to inpatient dermatology services, though some did not feel this way (16% [6/37] neutral or strongly disagree). Nearly all respondents (97% [36/37]) felt they provide a critical service when performing inpatient dermatology consultations. All respondents (100%) said they found providing inpatient dermatology consultations fulfilling, and 65% (24/37) said they prefer providing inpatient dermatology consultations to spending time in clinic. Of the DHs who were surveyed, 68% (25/37) said they were satisfied with the balance of outpatient and inpatient services in their clinical practice and 30% (11/37) said they were not.

Comment

Factors such as patient care, hospital infrastructure, and procedural support have all been cited by DHs as crucial aspects of their contributions to the care of hospitalized pa

Dermatology is primarily an outpatient specialty, and our study highlighted several important challenges for providers performing inpatient dermatology consultations. A major issue is time expenditures, including additional teaching requirements, additional electronic medical record training, and credentialing requirements. Travel time to inpatient hospital sites does not appear to be one of these hindering factors; nearly 60% of respondents rated their travel time/effort as very easy, with approximately 75% of respondents’ consultation locations being either at the same physical location as their main outpatient clinic or less than 15 minutes away. Maintaining easy travel between outpatient and inpatient settings is important to the success of the DH.

Our data suggest that compensation of DHs is a potential limitation to providing inpatient dermatology care. Our survey reinforced that providers who do inpatient dermatology consultations generally do not generate the revenue necessary to cover these efforts. More than 40% of DH respondents said they either feel neutral about or unsatisfied with their overall salary, and more than half said they feel similarly regarding their institutions’ compensation models. Most respondents said that a fixed salary model plus productivity or performance incentives is the ideal compensation model for those providing inpatient dermatology consultations, though only half said they actually are compensated according to this model. This discrepancy highlights the disconnect between the current accepted compensation models and the DH’s ideal model and provides direction for dermatology chairs and division heads as to what compensation model is preferable to support the success of DHs at their institutions.

Despite the barriers and compensation constraints we identified, DHs report high job satisfaction, which we hypothesize could combat burnout. In our study, all DHs surveyed say they find providing inpatient dermatology consultations fulfilling, and most were satisfied with the amount of time allotted for consultations. Some of the possible reasons why DHs may find their work fulfilling include increased time for teaching trainees and learning about patients and their conditions while consulting, as well as a preference for providing inpatient dermatology consultations to spending time in clinic. Most DHs said they choose to provide inpatient dermatology consultation rather than do so as a requirement, primarily due to their interest in complex medical dermatology and their desire to work with other medical teams/specialties; thankfully, only a small percentage said they provide these consultations because they are required to do so.

This study was conducted to analyze job satisfaction among DHs who provided inpatient dermatology consultations and determine common barriers and obstacles to their job satisfaction. Limitations to our study included the small sample size and the possibly limited representation of the intended population, as only the members of the SDH were surveyed, potentially excluding providers who regularly perform inpatient dermatology consultations but are not members of the SDH. Further limitations included recall bias and the qualitative nature of the survey instrument.

Final Thoughts

There was near-unanimous agreement among the DHs we surveyed regarding the importance of the role they play in their divisions/departments, but there are clear barriers to provision of inpatient dermatology consultation, specifically relating to extraneous time expenditures and compensation. Despite these barriers, the majority of respondents said they are very satisfied with the role they play in the inpatient setting and feel that their contributions are valued by the institutions where they work. Protecting these benefits of providing dermatology hospital consultations will be critical for maintaining this high job satisfaction and balancing out the barriers to providing these consultations. Protecting the time required to provide consultations is paramount so DHs continue to gain fulfillment from teaching trainees, caring for complex patients, and maintaining their place as valuable colleagues in the hospital setting.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the members of the SDH for their participation in this survey.

- Biesbroeck LK, Shinohara MM. Inpatient consultative dermatology. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:1349-1364.

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.e2.

- Arnold JD, Yoon SJ, Kirkorian AY. The national burden of inpatient dermatology in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;80:425-432.

- Mancusi S, Festa Neto C. Inpatient dermatological consultations in a university hospital. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65:851-855.

- Tsai S, Scott JF, Keller JJ, et al. Cutaneous malignancies identified in an inpatient dermatology consultation service. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:e116-e118.

- Pereira AR, Porro AM, Seque CA, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultations in renal transplant recipients. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:900-907.

- Tracey EH, Forrestel A, Rosenbach M, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:835-836.

- Fox LP, Cotliar J, Hughey L, et al. Hospitalist dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:153-154.

- Ko LN, Kroshinsky D. Dermatology hospitalists: a multicenter survey study characterizing the infrastructure of consultative dermatology in select American hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:553-558.

- Hansra NK, Shinkai K, Fox LP. Ethical issues in inpatient consultative dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:496-500.

- El-Azhary R, Weenig RH, Gibson LE. The dermatology hospitalist: creating value by rapid clinical pathologic correlation in a patient-centered care model. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1461-1466.

- Ahronowitz I, Fox LP. Herpes zoster in hospitalized adults: practice gaps, new evidence, and remaining questions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:223-230.e3.

- Rosenbach M. The logistics of an inpatient dermatology service. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:3-8.

- Ackerman L, Kessler M. The efficient, effective community hospital inpatient dermatology consult. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:9-11.

- Biesbroeck LK, Shinohara MM. Inpatient consultative dermatology. Med Clin North Am. 2015;99:1349-1364.

- Lim HW, Collins SAB, Resneck JS Jr, et al. The burden of skin disease in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:958-972.e2.

- Arnold JD, Yoon SJ, Kirkorian AY. The national burden of inpatient dermatology in adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;80:425-432.

- Mancusi S, Festa Neto C. Inpatient dermatological consultations in a university hospital. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65:851-855.

- Tsai S, Scott JF, Keller JJ, et al. Cutaneous malignancies identified in an inpatient dermatology consultation service. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:e116-e118.

- Pereira AR, Porro AM, Seque CA, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultations in renal transplant recipients. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2018;109:900-907.

- Tracey EH, Forrestel A, Rosenbach M, et al. Inpatient dermatology consultation in patients with hematologic malignancies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:835-836.

- Fox LP, Cotliar J, Hughey L, et al. Hospitalist dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:153-154.

- Ko LN, Kroshinsky D. Dermatology hospitalists: a multicenter survey study characterizing the infrastructure of consultative dermatology in select American hospitals. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:553-558.

- Hansra NK, Shinkai K, Fox LP. Ethical issues in inpatient consultative dermatology. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:496-500.

- El-Azhary R, Weenig RH, Gibson LE. The dermatology hospitalist: creating value by rapid clinical pathologic correlation in a patient-centered care model. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1461-1466.

- Ahronowitz I, Fox LP. Herpes zoster in hospitalized adults: practice gaps, new evidence, and remaining questions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:223-230.e3.

- Rosenbach M. The logistics of an inpatient dermatology service. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:3-8.

- Ackerman L, Kessler M. The efficient, effective community hospital inpatient dermatology consult. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2017;36:9-11.

Practice Points

• Dermatology hospitalists play a critical role in the specialized care of hospitalized patients with

skin conditions.

• Dermatology hospitalists have high job satisfaction, with opportunities to teach trainees and practice complex medical dermatology.

• Most dermatology hospitalists do not generate sufficient revenue providing inpatient dermatology consultations to fully support their salary for the time spent as consultants; alternate payment models are needed to maintain dermatology’s presence in the hospital.

Managing dermatologic changes of targeted cancer therapy

Advances in cancer therapy have improved survival, such that many cancers have been transformed from a terminal illness to a chronic disease, and the population of patients living with cancer or who are disease-free has grown. However, these patients face complex medical problems because of the systemic effects of their treatment and many endure a constellation of treatment-emergent adverse effects that require ongoing care and support.1

Primary care physicians have been called on to take a larger role in the care of these adverse effects as the growing number of treatments has meant more affected patients. In addition, an urgent, unmet need has developed for better coordination between specialists and family physicians for providing this supportive care.2

In this article, we (1) describe the most commonly encountered cancer treatment–related skin toxicities, paying particular attention to the effects of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–targeting therapies, and (2) review up-to-date management recommendations in an area of practice where established clinical guidance from the scientific literature is limited.

Biggest culprit: Targeted cancer therapies

Skin rash and dermatologic adverse effects are commonplace in patients undergoing cancer treatment; timely management can often prevent long-term skin damage.3 Dermatologic effects have been associated with various therapeutic agents, but are most commonly associated with targeted therapies—specifically, agents targeting EGFR.

Why the attention to EGFR inhibition? EGFR is overexpressed or mutated in a multitude of solid tumors; as such, agents have been developed that target this aberrant signaling pathway. EGFR is highly expressed in the skin and dermal tissue, where it plays a number of roles, including protection against ultraviolet radiation damage.4

Blockade of the EGFR molecule leads to dermal changes, however, presenting as acneiform rash, skin fissure and xerosis, and pruritus.5 In extreme instances, toxic effects can manifest as paronychia, facial hypertrichosis, and trichomegaly. These skin changes can be deforming as well as painful, and can have physiological and psychological consequences.6

In turn, a decrease in quality of life (as reported by patients suffering from skin toxicity) can affect cancer treatment adherence and efficacy,7 and severe skin changes can result in the need to reduce the dosage of anti-cancer therapies.8 Skillful evaluation and appropriate management of skin eruptions in patients undergoing cancer therapy is therefore vital to an overall satisfactory outcome.

Continue to: How common a problem?

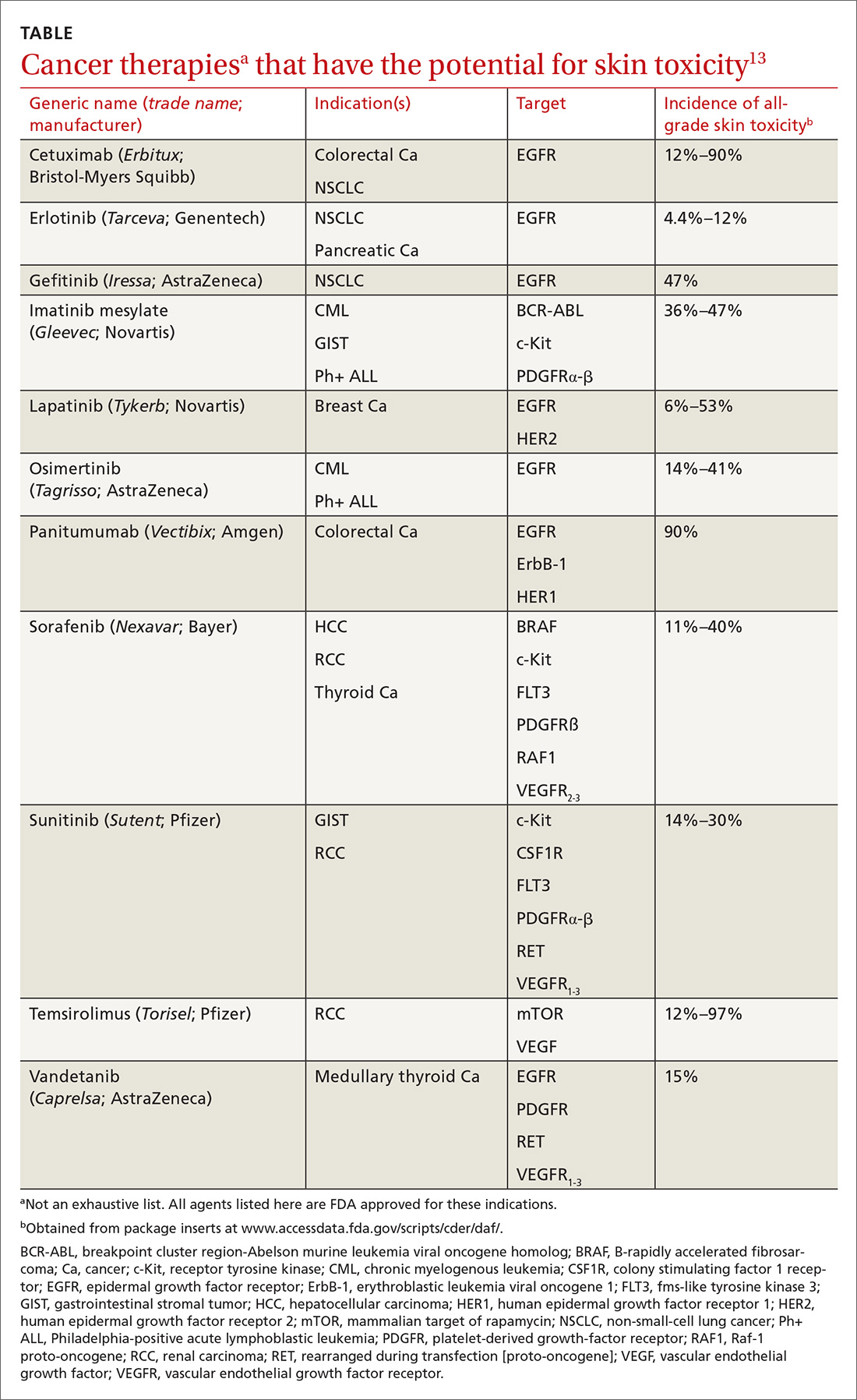

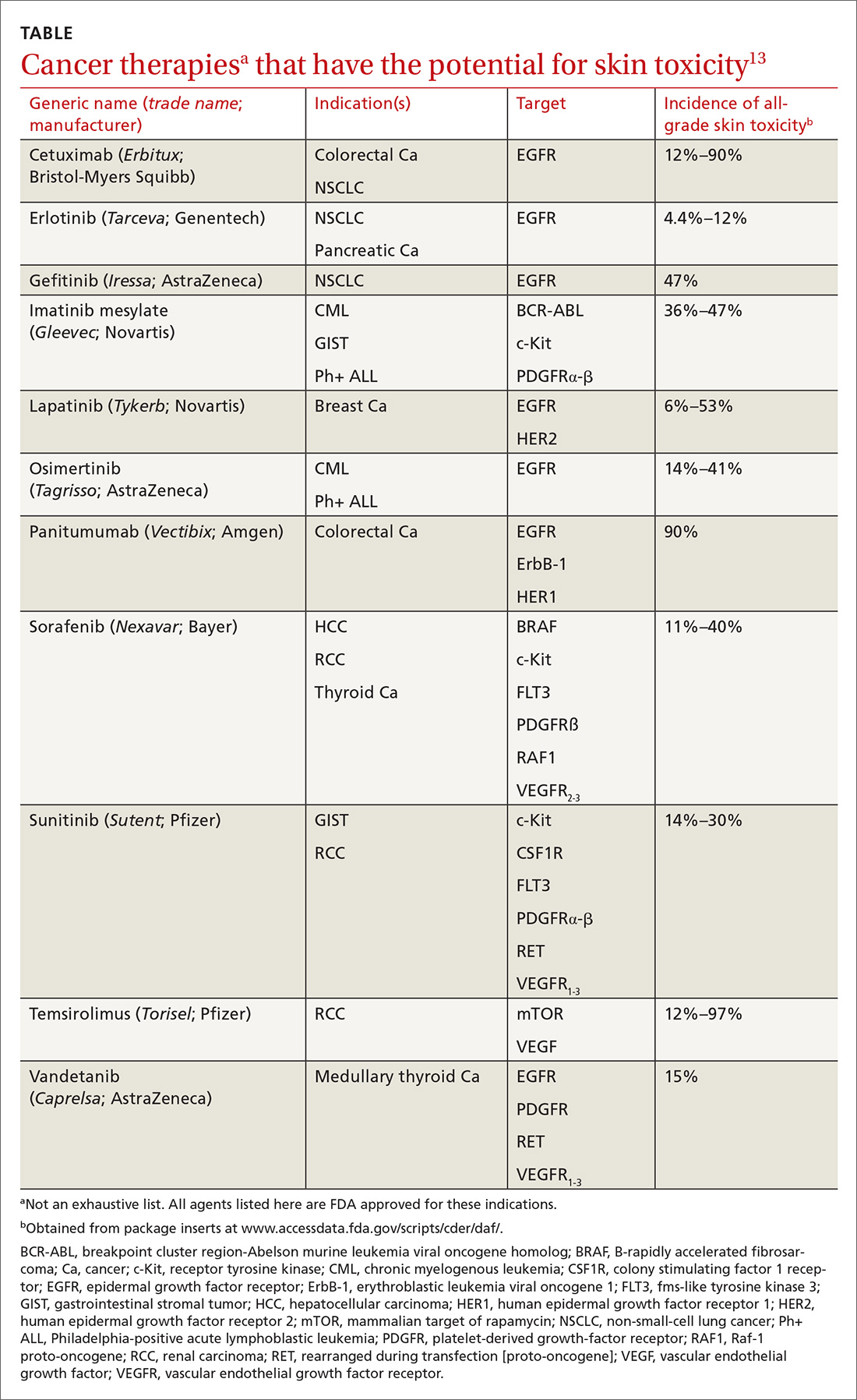

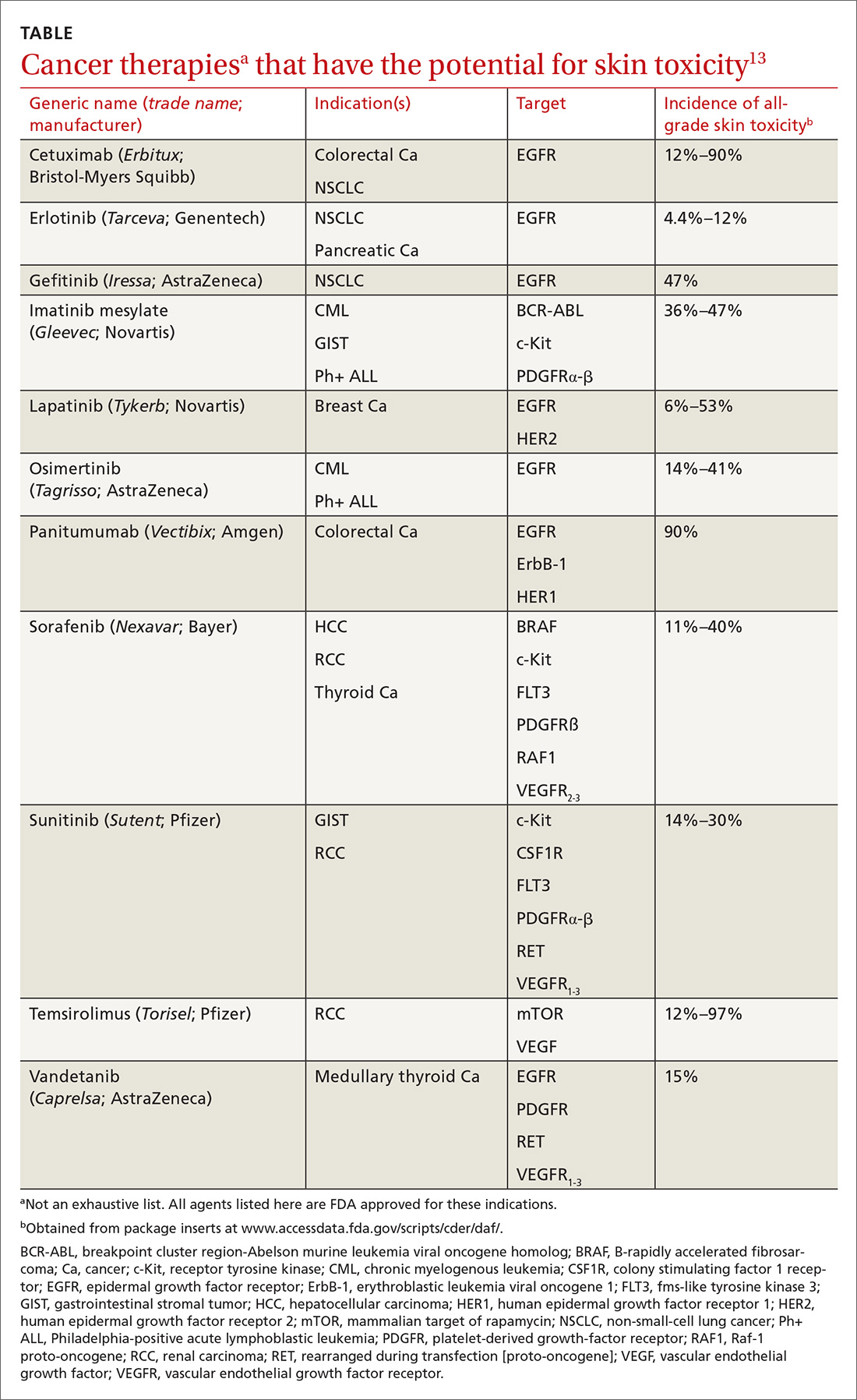

How common a problem? The incidence of EGFR inhibitor (EGFRI)–related rash is noteworthy: Overall incidence ranges from 45% to 100% of treated patients, with 10% experiencing Grade 3 to 4 changes (covering > 30% of body surface, restricting activities of daily living, severe itching).9 Monoclonal antibody therapies that target EGFR, such as cetuximab, have a reported 90% risk of skin rash, with 10% also being of Grade 3 to 4.10 Risk factors for rash include skin phototype, male gender, and younger age.11,12 Common cancer therapies with known skin effects are listed in the TABLE.13

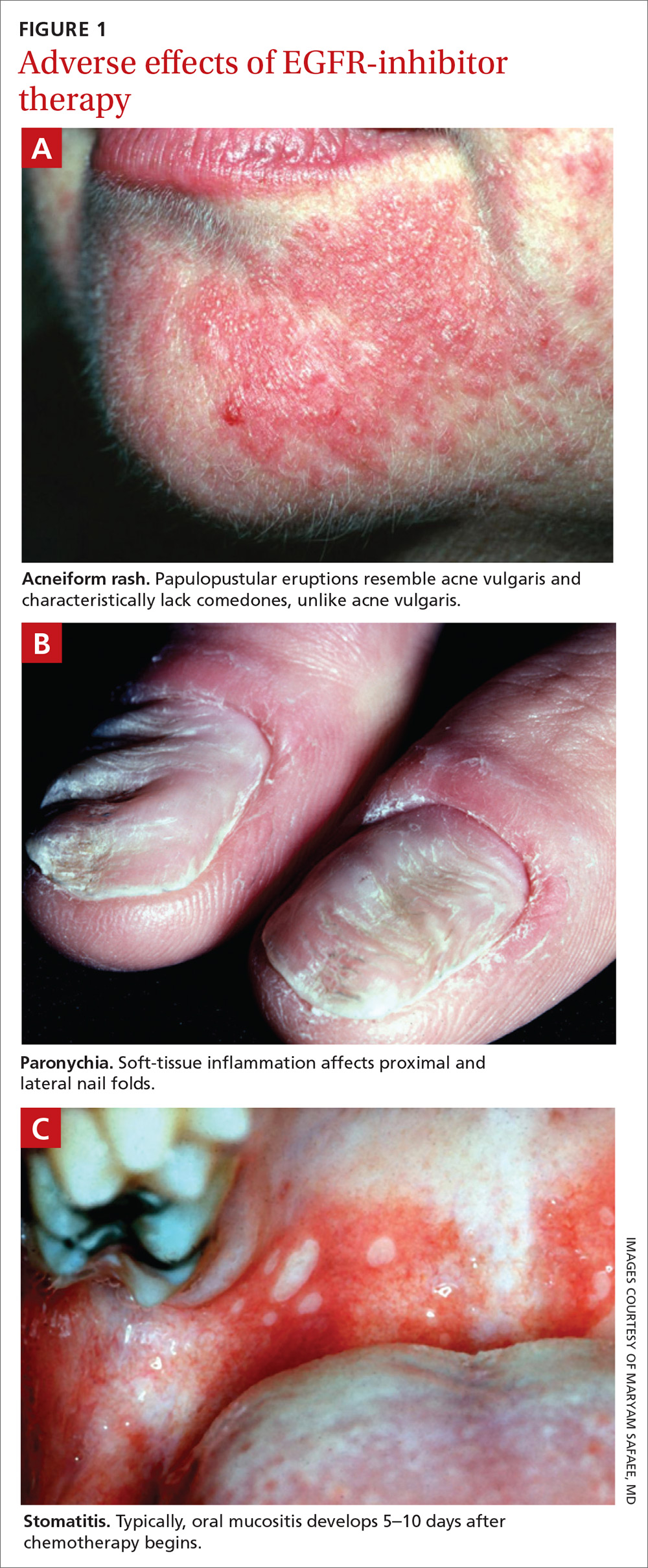

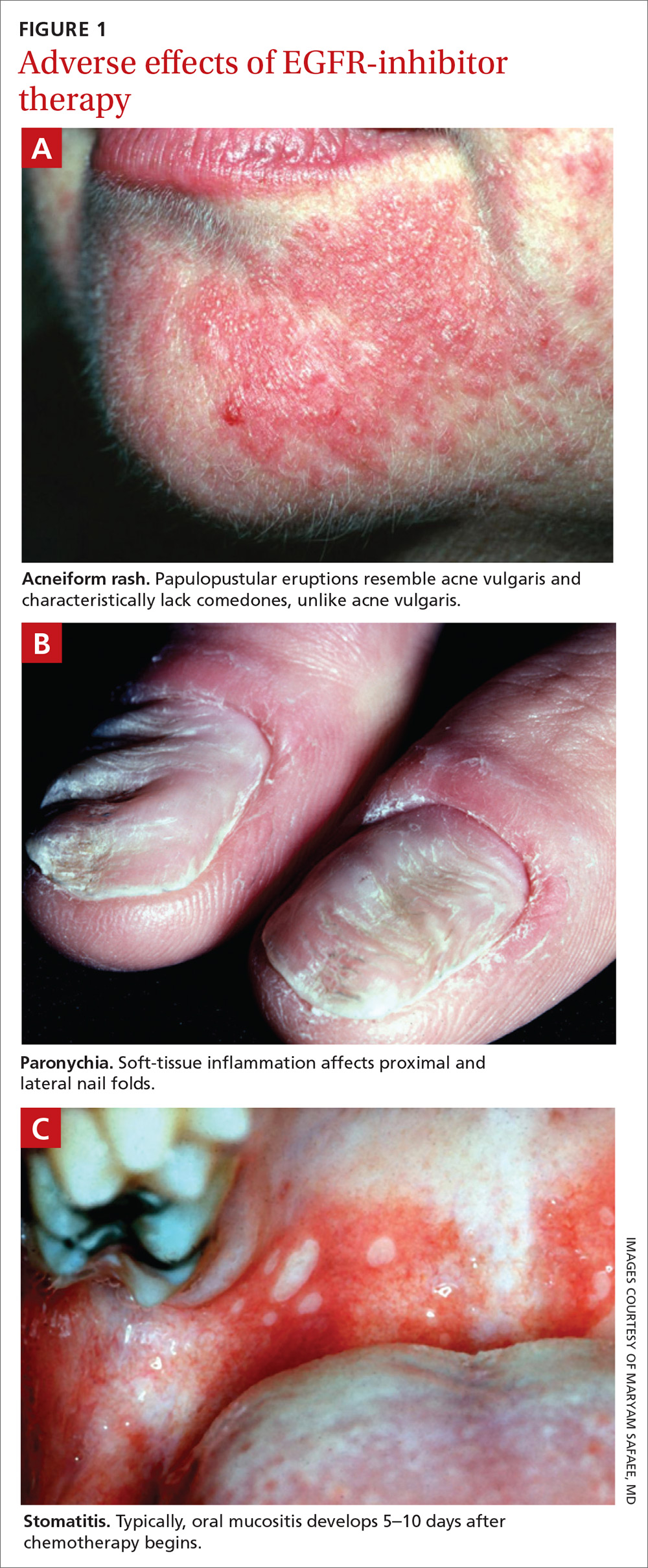

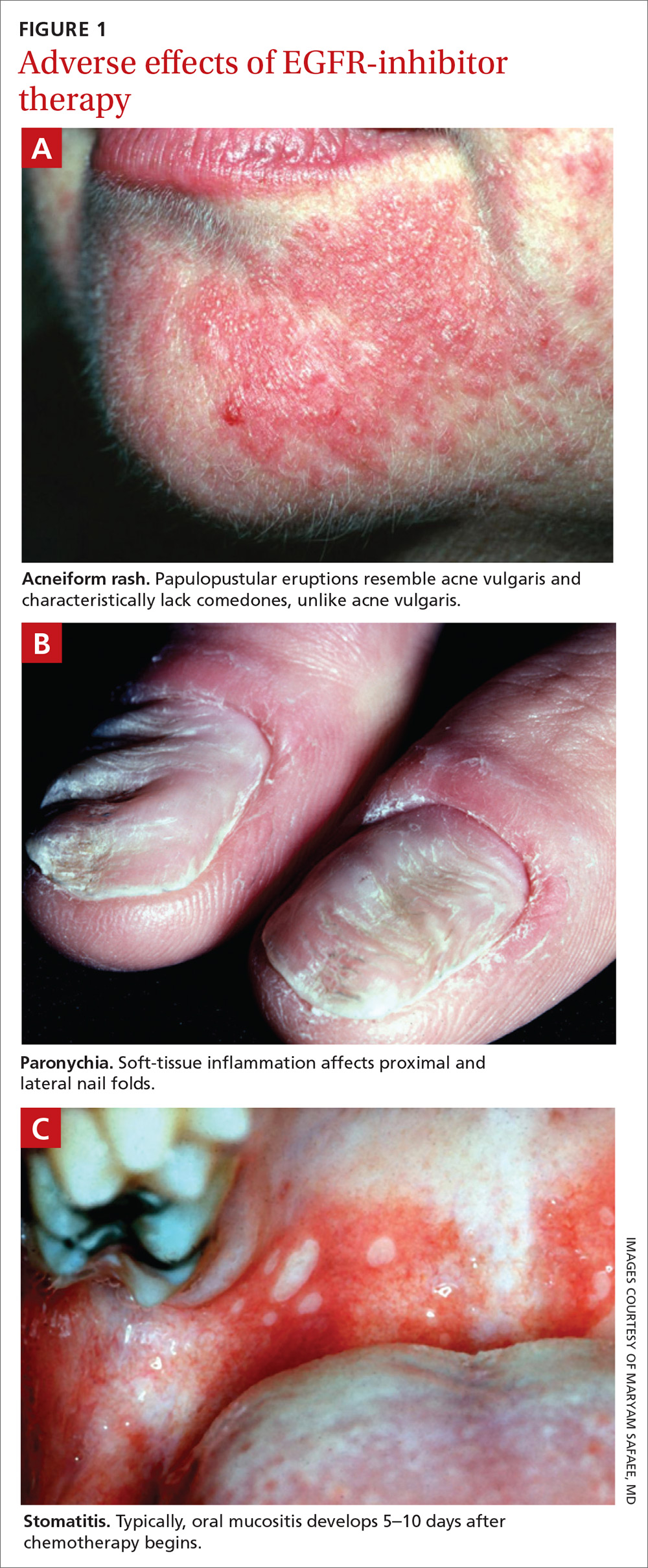

What should you look for? The most common clinical manifestation of dermatologic toxicity is an acneiform, or papulopustular, rash marked by eruptions characterized as “acne-like” pustules with monotonous lesion morphology (Figure 1a). A hallmark of these lesions that can be used to help distinguish them from acne vulgaris is the absence of comedones on eruptions.

The timeline of the rash has been well characterized and is another tool that you can use to guide management:

- During Week 1 of cancer treatment, the patient often experiences sensory disturbances, with erythema and edema.14

- Throughout Weeks 2 and 3, erythematous skin evolves into papulopustular eruptions.

- By Week 4, eruptions typically crust over and leave persistently dry skin for weeks.15,16

Of note, the rash is dosage related; we recommend scrupulous vigilance when a patient is receiving a high dosage of a targeted therapy agent.

Controlling a rash

Treatment of EGFRI-associated skin changes stems from recommendations from a number of individual investigators and studies; however, few consensus guidelines exist to guide practice. Understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanism of skin changes has evolved, but preventive and treatment modalities remain unchanged—and limited.

Continue to: Always counsel patients...

Always counsel patients before a rash develops (and, ideally, before chemotherapy begins) that they should report a rash early in its development, to you or their oncologist, so that timely treatment can occur. Early recognition and intervention have proven benefits and can prevent the rash and its symptoms from becoming worse17; if the rash remains uncontrolled, dosage reduction of the chemotherapeutic agent is an inevitable reality, and the clinical outcome of the primary disease might therefore not be ideal.18

Prophylaxis. Daily application of an alcohol-free emollient cream is highly recommended as a preventive measure. Patients should be counseled to avoid activities and skin products that lead to dry skin, including long and hot showers; perfumes or other alcohol-based products; and soaps marketed for treating acne, which have a profound skin-drying effect.

Cornerstones of treatment include topical moisturizers, steroids, and antihistamines for symptom control. Once an identifiable skin rash has developed, a topical steroid cream is first-line treatment. Successful control has been reported with 1% hydrocortisone lotion applied daily to the affected area.15

Second- and third-line Tx. If the rash progresses in size or severity, we recommend switching to 2% hydrocortisone valerate cream, applied twice daily. For a moderate-to-severe rash, an oral tetracycline is a valid option for its anti-inflammatory effects and, possibly, to prevent secondary infection. In the event of progression, refer the patient to an oncologist, who can consider suspending the anti-EGRF drug temporarily until the rash improves. If disease persists, consultation with a dermatologist is appropriate for consideration of systemic prednisolone.

Alleviating discomfort. Patients commonly report pruritus and mild-to-moderate pain with the rash; standard analgesic therapy is appropriate.19 Severe pain might indicate secondary infection; in that case, consider antibiotic therapy for presumed cellulitis. Moreover, because of the risk of thrombosis in the cancer population, underlying deep-vein thrombosis must always remain in the differential diagnosis of an erythematous rash.

Continue to: A short course...

A short course of systemic steroids might be beneficial for pain control; however, no data from clinical trials suggest that this is beneficial. Dermatology consultation is recommended before prescribing a systemic steroid.

Regrettably, treatment options for pruritus are limited. Antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine and hydroxyzine, can be considered, but their effectiveness is marginal.20 If a patient reports a painful rash, we recommend that you collaborate with the dermatologist and oncologist to make adjustments to the cancer treatment plan.

Retinoids: Caution is advised. Several case reports and a small investigational study describe a potential role for retinoids such as isotretinoin, a 13-cis retinoic acid, in the treatment of chemotherapy-related skin changes.21,22 Isotretinoin is available under several trade names in pill and cream formulations.

Retinoids exert their effect at the level of DNA transcription, and act as a transcription factor in keratinocytes. Their downstream signaling pathway includes EGFR signaling ligands; introduction of exogenous retinoids has been shown to deter development of EGFRI-associated skin toxicity.23 Given the lack of clinical data, retinoid-based medications should be used at the discretion of a dermatologist; thorough discussion is encouraged among the dermatologist, oncologist, and primary care physician before employing a retinoid.

Recommend a sunscreen? Given the endogenous role of EGFR in protecting skin from ultraviolet B damage, some clinicians have recommended that patients use a sunscreen. However, randomized, controlled trials have failed to demonstrate any benefit to their use with regard to incidence or severity of rash or patient-reported discomfort.24 We do not recommend routine use of sunscreen to prevent chemotherapy-induced skin changes, although sensible use during periods of prolonged sun exposure is encouraged.

Continue to: Risk of infection and the role of antibiotics

Risk of infection and the role of antibiotics

Skin damage can lead to further complications—namely, leaving the skin vulnerable to bacterial overgrowth and serious infection.14 The primary acneiform eruption is believed to be inflammatory in nature, with most cases being sterile and lacking bacterial growth.25 However, rash-associated infections are a common complication and leave the immunocompromised patient at risk of systemic infection: Harandi et al26 reported a 35% rate of secondary infection. Viral or bacterial growth (the primary pathogen is Staphylococcus aureus) within the wound can aggravate the severity of the rash, prohibit effective healing, and exacerbate the disfiguring appearance of the rash.

The use of a prophylactic antibiotic for treating a rash in this setting has been an active area of discussion and research, although no guidelines or recommendations exist that can be routinely employed. A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated that, in patients undergoing EGFR-based therapy, those who received a prophylactic antibiotic had a lower risk of developing folliculitis than those who did not (odds ratio = 0.53; 95% confidence interval, 0.39-0.72; P < .01). 27

A consensus agreement on the use of prophylactic antibiotics has yet to be reached. An emerging clinical practice entails the use of oral minocycline (100 mg/d) during the first 4 weeks of EGFRI-based therapy because studies have shown a benefit from this regimen in reducing eruptions.28

Other adverse dermatologic effects to watch for

Paronychia is common in patients undergoing EGFRI therapy but, unlike the acneiform rash that typically occurs within 1 week of treatment, paronychia can occur weeks or months after initiation of therapy. Careful examination of the nail beds is important in patients undergoing EGFRI therapy (FIGURE 1B). Paronychia can affect the nail beds of the fingers and toes—most often, the first digits.29

No evidence-based trials have been conducted to evaluate treatment options; recommendations provided are drawn from the literature and expert opinion. Patients are encouraged to apply petroleum jelly or an emollient daily both as a preventive measure and for mild cases. Patient counseling on the importance of nail hygiene and avoidance of aggressive manicures and pedicures is encouraged.30

Continue to: In the general population...

In the general population, acute and chronic paronychia entail infection with S aureus and Candida spp, respectively. To this end, there is a role for antibacterial and antifungal intervention. As is the case of the EGFRI-associated acneiform rash, inflammation in paronychia is sterile, with only rare pathogen involvement.

There is no role for topical or systemic antibiotics in the cancer population suffering from paronychia. A viable treatment option for moderate lesions is betamethasone valerate, applied 2 or 3 times daily; if there is no resolution, clobetasol cream, applied 2 or 3 times daily, can be prescribed.30 The role of tetracyclines as anti-inflammatory agents in paronychia has not been studied to the extent it has been for acneiform rash; however, studies have shown a protective effect in small patient samples.31 In severe disease, the patient can be instructed to temporarily discontinue the drug and you can provide a referral to a dermatologist.

Stomatitis is also an area of concern in this patient population (FIGURE 1c). Prior to initiating treatment, a thorough examination of the patient’s oral cavity and oropharynx should be conducted. Loose or improperly fitting dentures should be adjusted because they can prohibit effective healing after ulceration develops.

Stomatitis initially presents as erythematous or aphthous-like lesions, and can develop into acutely painful, large, continuous lesions.29 Timely management of stomatitis is beneficial to patient outcomes because it can lead to severe pain and interference in oral intake; uncontrolled disease requires interruption and dosage-reduction of cancer therapy.14,32

Patients should be encouraged to use soft-bristle toothbrushes and rinse with normal saline, not with commercial mouthwashes that typically contain alcohol. Grade 1 stomatitis (ie, pain and erythema) can be treated with triamcinolone dental paste, which can reduce inflammation caused by the ulcers. If disease progresses to Grade 2 to 3 stomatitis (erythema; ulceration; difficulty swallowing, or inability to swallow food), oral erythromycin (250-350 mg/d) or minocycline (50 mg/d) should be prescribed and the patient referred to a dermatologist.30

Continue to: Does rash correlate with cancer treatment efficacy?

Does rash correlate with cancer treatment efficacy?

Despite troubling dermatologic effects of cancer therapies, a retrospective analysis of several clinical trials has revealed another side to this coin: namely, the appearance, and the severity, of a rash correlates positively with objective tumor response.14 That correlation allows the oncologist to use a rash as a surrogate marker of treatment efficacy20 (although, notably, there remains a lack of prospective trials that would validate a rash as such a marker). Epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors are mainly prescribed in patients who harbor an activating EGFR mutation; no studies have stratified patients by EGFR mutation and incidence of rash.33

The upshot? Although there are gaps in our understanding of the relationship between a rash and overall survival, we are nevertheless presented with this paradigm: A patient who is taking an EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor and who develops a rash should be continued on that treatment for as long as can be tolerated, because the rash is presumed to be a sign that the patient is deriving the greatest clinical benefit from therapy.14,20,33

CORRESPONDENCE

Kevin Zarrabi, MD, MSc, Department of Medicine, Health Science Center T16, Room 020, Stony Brook, NY 11790-8160; [email protected]

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Ali John Zarrabi, MD, provided skillful editing of the manuscript of this article.

1. Phillips JL, Currow DC. Cancer as a chronic disease. Collegian. 2010;17:47-50.

2. Klabunde CN, Ambs A, Keating NL, et al. The role of primary care physicians in cancer care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:1029-1036.

3. Agha R, Kinahan K, Bennett CL, et al. Dermatologic challenges in cancer patients and survivors. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21:1462-1472; discussion 1473,1476,1481 passim.

4. Mitchell EP, Pérez-Soler R, Van Cutsem, et al. Clinical presentation and pathophysiology of EGFRI dermatologic toxicities. Oncology (Williston Park). 2007;21(11 suppl 5):4-9.

5. Liu S, Kurzrock R. Understanding toxicities of targeted agents: implications for anti-tumor activity and management. Semin Oncol. 2015;42:863-875.

6. Romito F, Giuliani F, Cormio C, et al. Psychological effects of cetuximab-induced cutaneous rash in advanced colorectal cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:329-334.

7. Wacker B, Nagrani T, Weinberg J, et al. Correlation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase III studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3913-3921.

8. Chou LS, Garey J, Oishi K, et al. Managing dermatologic toxicities of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Clin Lung Cancer. 2006;8(suppl 1):S15-S22.

9. Li T, Pérez-Soler R. Skin toxicities associated with epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Target Oncol. 2009;4:107-119.

10. Su X, Lacouture ME, Jia Y, et al. Risk of high-grade skin rash in cancer patients treated with cetuximab—an antibody against epidermal growth factor receptor: systemic review and meta- analysis. Oncology. 2009;77:124-133.

11. Luu M, Boone SL, Patel J, et al. Higher severity grade of erlotinib-induced rash is associated with lower skin phototype. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011;36:733-738.

12. Jatoi A, Green EM, Rowland KM Jr, et al. Clinical predictors of severe cetuximab-induced rash: observations from 933 patients enrolled in North Central Cancer Treatment Group study N0147. Oncology. 2009;77:120-123.

13. Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. US Food and Drug Administration Web site. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/. Accessed June 4, 2019.

14. Melosky B, Burkes R, Rayson D, et al. Management of skin rash during EGFR-targeted monoclonal antibody treatment for gastrointestinal malignancies: Canadian recommendations. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:16-26.

15. Lacouture ME, Melosky BL. Cutaneous reactions to anticancer agents targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor: a dermatology-oncology perspective. Skin Therapy Lett. 2007; 12:1-5.

16. Eaby B, Culkin A, Lacouture ME. An interdisciplinary consensus on managing skin reactions associated with human epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008; 12:283-290.

17. Hirsh V. Managing treatment-related adverse events associated with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Curr Oncol. 2011;18:126-138.

18. Reguiai Z, Bachet JB, Bachmeyer C, et al. Management of cuta- neous adverse events induced by anti-EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor): a French interdisciplinary therapeutic algo- rithm. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:1395-1404.

19. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-49.

20. Pérez-Soler R, Delord JP, Halpern A, et al. HER1/EGFR inhibitor-associated rash: future directions for management and investigation outcomes from the HER1/EGFR Inhibitor Rash Management Forum. Oncologist. 2005;10:345-356.

21. Bidoli P, Cortinovis DL, Colombo I, et al. Isotretinoin plus clindamycin seem highly effective against severe erlotinib-induced skin rash in advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:1662-1663.

22. Vezzoli P, Marzano AV, Onida F, et al. Cetuximab-induced ac - neiform eruption and the response to isotretinoin. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:84-86.

23. Rittié L, Varani J, Kang S, et al. Retinoid-induced epidermal hyperplasia is mediated by epidermal growth factor receptor activation via specific induction of its ligands heparin-binding EGF and amphiregulin in human skin in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:732-739.

24. Jatoi A, Thrower A, Sloan JA, et al. Does sunscreen prevent epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor-induced rash? Results of a placebo-controlled trial from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (N05C4). Oncologist. 2010; 15:1016-1022.

25. Lynch TJ Jr, Kim ES, Eaby B, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor-associated cutaneous toxicities: an evolving paradigm in clinical management. Oncologist. 2007;12:610-621.

26. Harandi A, Zaidi AS, Stocker AM, et al. Clinical efficacy and toxicity of anti-EGFR therapy in common cancers. J Oncol. 2009;2009:567486.

27. Petrelli F, Borgonovo K, Cabiddu M, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis for skin toxicity induced by antiepidermal growth factor receptor agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:1166-1174.

28. Scope A, Agero AL, Dusza SW, et al. Randomized double-blind trial of prophylactic oral minocycline and topical tazarotene for cetuximab-associated acne-like eruption. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5390-5396.

29. Lacouture ME, Anadkat MJ, Bensadoun RJ, et al; MASCC Skin Toxicity Study Group. Clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of EGFR inhibitor-associated dermatologic toxicities. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:1079-1095.

30. Melosky B, Leighl NB, Rothenstein J, et al. Management of egfr tki-induced dermatologic adverse events. Curr Oncol. 2015; 22:123-132.

31. Arrieta O, Vega-González MT, López-Macías D, et al. Randomized, open-label trial evaluating the preventive effect of tetracycline on afatinib induced-skin toxicities in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Lung Cancer. 2015;88:282-288.

32. Saito H, Watanabe Y, Sato K, et al. Effects of professional oral health care on reducing the risk of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2935-2940.

33. Kozuki T. Skin problems and EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46:291-298.

Advances in cancer therapy have improved survival, such that many cancers have been transformed from a terminal illness to a chronic disease, and the population of patients living with cancer or who are disease-free has grown. However, these patients face complex medical problems because of the systemic effects of their treatment and many endure a constellation of treatment-emergent adverse effects that require ongoing care and support.1

Primary care physicians have been called on to take a larger role in the care of these adverse effects as the growing number of treatments has meant more affected patients. In addition, an urgent, unmet need has developed for better coordination between specialists and family physicians for providing this supportive care.2

In this article, we (1) describe the most commonly encountered cancer treatment–related skin toxicities, paying particular attention to the effects of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)–targeting therapies, and (2) review up-to-date management recommendations in an area of practice where established clinical guidance from the scientific literature is limited.

Biggest culprit: Targeted cancer therapies

Skin rash and dermatologic adverse effects are commonplace in patients undergoing cancer treatment; timely management can often prevent long-term skin damage.3 Dermatologic effects have been associated with various therapeutic agents, but are most commonly associated with targeted therapies—specifically, agents targeting EGFR.

Why the attention to EGFR inhibition? EGFR is overexpressed or mutated in a multitude of solid tumors; as such, agents have been developed that target this aberrant signaling pathway. EGFR is highly expressed in the skin and dermal tissue, where it plays a number of roles, including protection against ultraviolet radiation damage.4

Blockade of the EGFR molecule leads to dermal changes, however, presenting as acneiform rash, skin fissure and xerosis, and pruritus.5 In extreme instances, toxic effects can manifest as paronychia, facial hypertrichosis, and trichomegaly. These skin changes can be deforming as well as painful, and can have physiological and psychological consequences.6

In turn, a decrease in quality of life (as reported by patients suffering from skin toxicity) can affect cancer treatment adherence and efficacy,7 and severe skin changes can result in the need to reduce the dosage of anti-cancer therapies.8 Skillful evaluation and appropriate management of skin eruptions in patients undergoing cancer therapy is therefore vital to an overall satisfactory outcome.

Continue to: How common a problem?

How common a problem? The incidence of EGFR inhibitor (EGFRI)–related rash is noteworthy: Overall incidence ranges from 45% to 100% of treated patients, with 10% experiencing Grade 3 to 4 changes (covering > 30% of body surface, restricting activities of daily living, severe itching).9 Monoclonal antibody therapies that target EGFR, such as cetuximab, have a reported 90% risk of skin rash, with 10% also being of Grade 3 to 4.10 Risk factors for rash include skin phototype, male gender, and younger age.11,12 Common cancer therapies with known skin effects are listed in the TABLE.13

What should you look for? The most common clinical manifestation of dermatologic toxicity is an acneiform, or papulopustular, rash marked by eruptions characterized as “acne-like” pustules with monotonous lesion morphology (Figure 1a). A hallmark of these lesions that can be used to help distinguish them from acne vulgaris is the absence of comedones on eruptions.

The timeline of the rash has been well characterized and is another tool that you can use to guide management:

- During Week 1 of cancer treatment, the patient often experiences sensory disturbances, with erythema and edema.14

- Throughout Weeks 2 and 3, erythematous skin evolves into papulopustular eruptions.

- By Week 4, eruptions typically crust over and leave persistently dry skin for weeks.15,16

Of note, the rash is dosage related; we recommend scrupulous vigilance when a patient is receiving a high dosage of a targeted therapy agent.

Controlling a rash

Treatment of EGFRI-associated skin changes stems from recommendations from a number of individual investigators and studies; however, few consensus guidelines exist to guide practice. Understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanism of skin changes has evolved, but preventive and treatment modalities remain unchanged—and limited.

Continue to: Always counsel patients...

Always counsel patients before a rash develops (and, ideally, before chemotherapy begins) that they should report a rash early in its development, to you or their oncologist, so that timely treatment can occur. Early recognition and intervention have proven benefits and can prevent the rash and its symptoms from becoming worse17; if the rash remains uncontrolled, dosage reduction of the chemotherapeutic agent is an inevitable reality, and the clinical outcome of the primary disease might therefore not be ideal.18

Prophylaxis. Daily application of an alcohol-free emollient cream is highly recommended as a preventive measure. Patients should be counseled to avoid activities and skin products that lead to dry skin, including long and hot showers; perfumes or other alcohol-based products; and soaps marketed for treating acne, which have a profound skin-drying effect.

Cornerstones of treatment include topical moisturizers, steroids, and antihistamines for symptom control. Once an identifiable skin rash has developed, a topical steroid cream is first-line treatment. Successful control has been reported with 1% hydrocortisone lotion applied daily to the affected area.15

Second- and third-line Tx. If the rash progresses in size or severity, we recommend switching to 2% hydrocortisone valerate cream, applied twice daily. For a moderate-to-severe rash, an oral tetracycline is a valid option for its anti-inflammatory effects and, possibly, to prevent secondary infection. In the event of progression, refer the patient to an oncologist, who can consider suspending the anti-EGRF drug temporarily until the rash improves. If disease persists, consultation with a dermatologist is appropriate for consideration of systemic prednisolone.

Alleviating discomfort. Patients commonly report pruritus and mild-to-moderate pain with the rash; standard analgesic therapy is appropriate.19 Severe pain might indicate secondary infection; in that case, consider antibiotic therapy for presumed cellulitis. Moreover, because of the risk of thrombosis in the cancer population, underlying deep-vein thrombosis must always remain in the differential diagnosis of an erythematous rash.

Continue to: A short course...

A short course of systemic steroids might be beneficial for pain control; however, no data from clinical trials suggest that this is beneficial. Dermatology consultation is recommended before prescribing a systemic steroid.

Regrettably, treatment options for pruritus are limited. Antihistamines, such as diphenhydramine and hydroxyzine, can be considered, but their effectiveness is marginal.20 If a patient reports a painful rash, we recommend that you collaborate with the dermatologist and oncologist to make adjustments to the cancer treatment plan.

Retinoids: Caution is advised. Several case reports and a small investigational study describe a potential role for retinoids such as isotretinoin, a 13-cis retinoic acid, in the treatment of chemotherapy-related skin changes.21,22 Isotretinoin is available under several trade names in pill and cream formulations.

Retinoids exert their effect at the level of DNA transcription, and act as a transcription factor in keratinocytes. Their downstream signaling pathway includes EGFR signaling ligands; introduction of exogenous retinoids has been shown to deter development of EGFRI-associated skin toxicity.23 Given the lack of clinical data, retinoid-based medications should be used at the discretion of a dermatologist; thorough discussion is encouraged among the dermatologist, oncologist, and primary care physician before employing a retinoid.

Recommend a sunscreen? Given the endogenous role of EGFR in protecting skin from ultraviolet B damage, some clinicians have recommended that patients use a sunscreen. However, randomized, controlled trials have failed to demonstrate any benefit to their use with regard to incidence or severity of rash or patient-reported discomfort.24 We do not recommend routine use of sunscreen to prevent chemotherapy-induced skin changes, although sensible use during periods of prolonged sun exposure is encouraged.

Continue to: Risk of infection and the role of antibiotics

Risk of infection and the role of antibiotics