User login

Concurrent Atopic Dermatitis and Psoriasis Vulgaris: Implications for Targeted Biologic Therapy

Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory skin condition associated with notable elevation in helper T cell (TH) production of TH1/TH17-mediated inflammatory cytokines, including IL-17A.1 Upon binding of IL-17A to IL-17 receptors in the skin, an inflammatory cascade is triggered, resulting in the classic clinical appearance of psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis often is managed by suppressing TH1/TH17-mediated inflammation using targeted immune therapy such as secukinumab, an IL-17A inhibitor.2 Atopic dermatitis (AD), another chronic inflammatory dermatosis, is associated with substantial elevation in TH2-mediated inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4.3 Dupilumab, which interacts with IL-4R, disrupts the IL-4 and IL-13 signaling pathways and demonstrates considerable efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe AD.4

A case series has shown that suppression of the TH1/TH17-mediated inflammation of psoriasis may paradoxically result in the development of TH2-mediated AD.5 Similarly, a recent case report described a patient who developed psoriasis following treatment of AD with dupilumab.6 Herein, we describe a patient with a history of psoriasis that was well controlled with secukinumab who developed severe refractory erythrodermic AD that resolved with dupilumab treatment. Following clearance of AD with dupilumab, he exhibited psoriasis recurrence.

Case Report

A 39-year-old man with a lifelong history of psoriasis was admitted to the hospital for management of severe erythroderma. Four years prior, secukinumab was initiated for treatment of psoriasis, resulting in excellent clinical response. He discontinued secukinumab after 2 years of treatment because of insurance coverage issues and managed his condition with only topical corticosteroids. He restarted secukinumab 10 months before admission because of a psoriasis flare. Shortly after resuming secukinumab, he developed a severe exfoliative erythroderma that was not responsive to corticosteroids, etanercept, methotrexate, or ustekinumab.

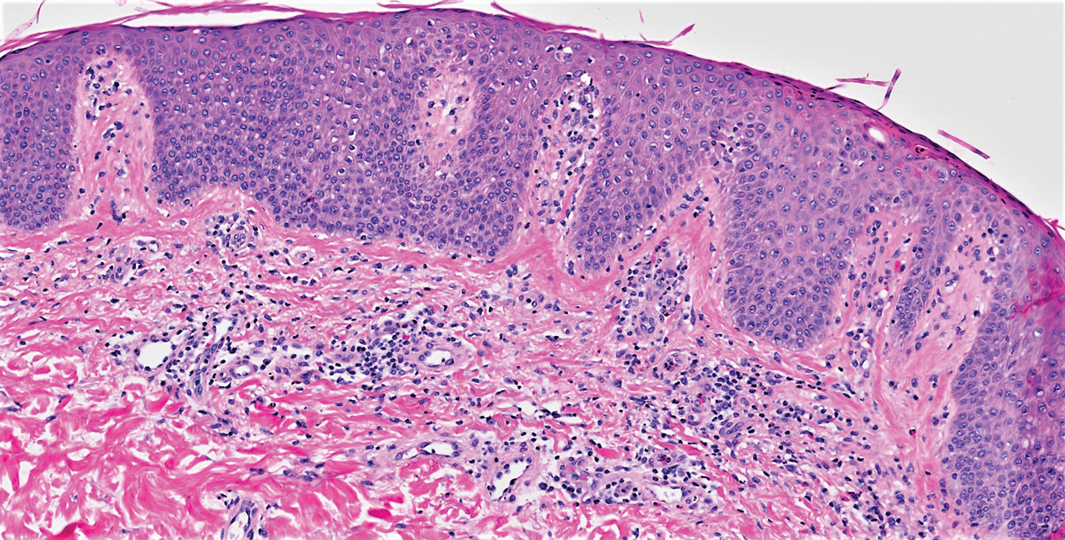

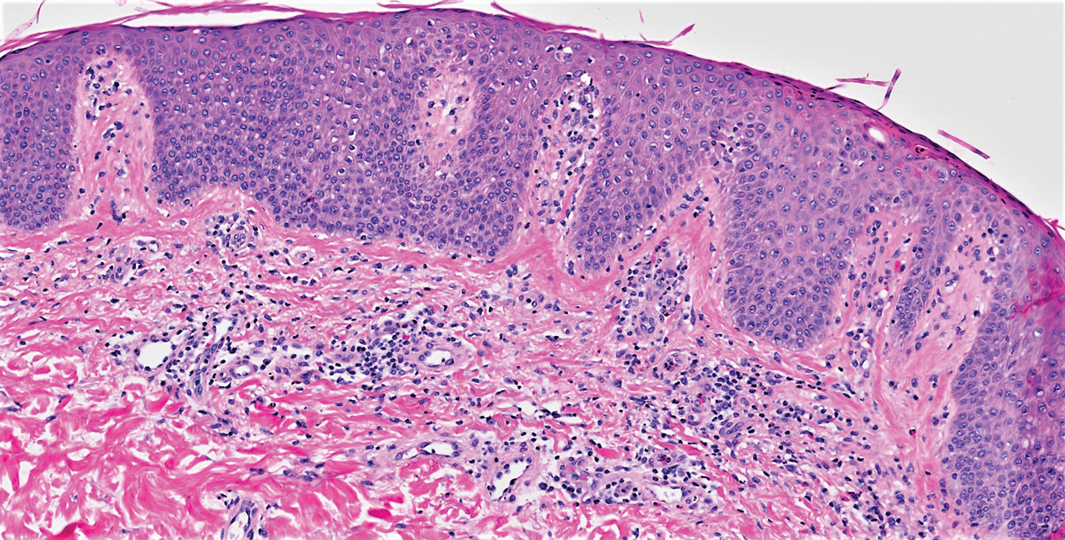

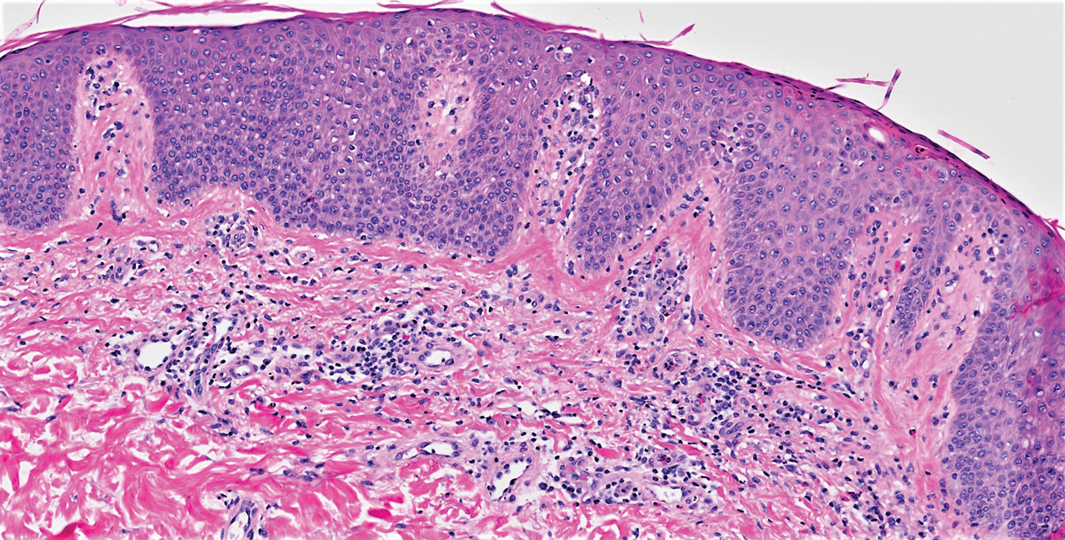

On initial presentation, physical examination revealed diffuse erythema and scaling with associated edema of the face, trunk, and extremities (Figure 1). A biopsy from the patient’s right arm demonstrated a superficial perivascular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and scattered eosinophils consistent with spongiotic dermatitis (Figure 2). Cyclosporine 225 mg twice daily and topical corticosteroids were started.

Over the next several months, the patient had several admissions secondary to recurrent skin abscesses in the setting of refractory erythroderma. He underwent trials of infliximab, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, guselkumab, and acitretin with minimal improvement. He underwent an extensive laboratory and radiologic workup, which was notable for cyclical peripheral eosinophilia and elevated IgE levels correlating with the erythroderma flares. A second biopsy was obtained and continued to demonstrate changes consistent with AD.

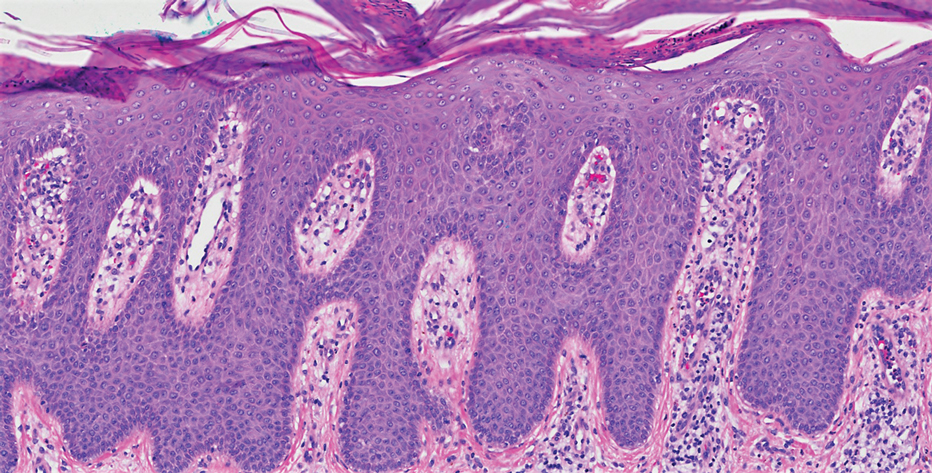

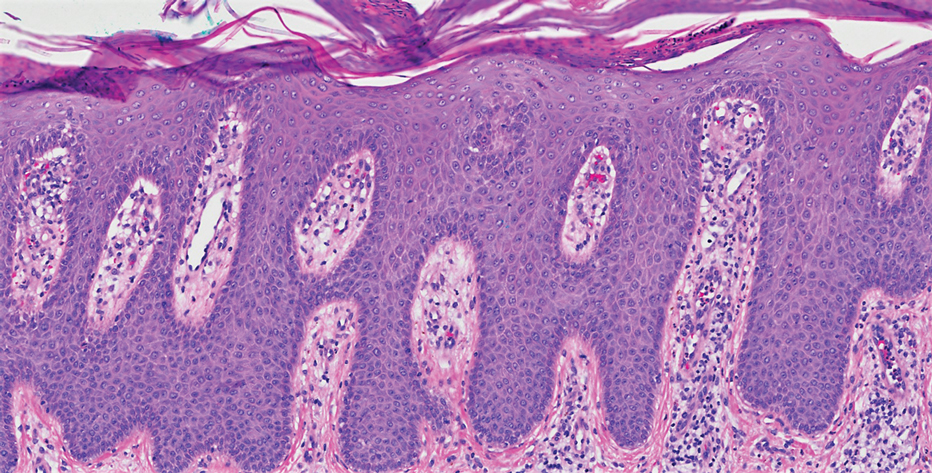

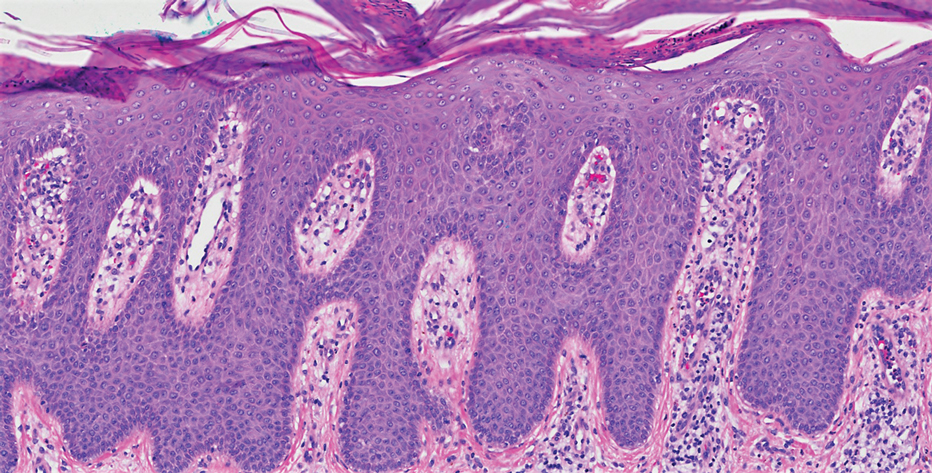

Four months after the initial hospitalization, all psoriasis medications were stopped, and the patient was started on dupilumab 300 mg/2 mL every 2 weeks and an 8-week oral prednisone taper. This combination led to notable clinical improvement and resolution of peripheral eosinophilia. Several months after disease remission, he began to develop worsening erythema and pruritus on the trunk and extremities, followed by the development of new psoriatic lesions (Figure 3) with a biopsy consistent with psoriasis (Figure 4). The patient was continued on dupilumab, but cyclosporine was added. The patient self-discontinued dupilumab owing to injection-site discomfort and has been slowly weaning off oral cyclosporine with 1 to 2 remaining eczematous plaques and 1 to 2 psoriatic plaques managed by topical corticosteroids.

Comment

We present a patient with psoriasis that was well controlled on secukinumab who developed severe AD following treatment with secukinumab. The AD resolved following treatment with dupilumab and a tapering dose of prednisone. However, after several months of treatment with dupilumab alone, he began to develop psoriatic lesions again. This case supports findings in a case series describing the development of AD in patients with psoriasis treated with IL-17 inhibitors5 and a recent case report describing a patient with AD who developed psoriasis following treatment with an IL-4/IL-13 inhibitor.6

Recognized adverse effects demonstrate biologic medications’ contributions to both normal as well as aberrant immunologic responses. For example, IL-17 plays an essential role in innate and adaptive immune responses against infections at mucosal and cutaneous interfaces, as demonstrated by chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in patients with genetic defects in IL-17–related pathways.7 Similarly, in patients taking IL-17 antagonists, an increase in the incidence of Candida infections has been observed.8 In patients with concurrent psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), treatment with IL-17 inhibitors is contraindicated due to the risk of exacerbating the IBD. This observation is somewhat paradoxical, as increased IL-17 release by TH17 cells is implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD.9 Interestingly, it is now thought that IL-17 may play a protective role in T-cell–driven intestinal inflammation through induction of protective intestinal epithelial gene expression and increased mucosal defense against gut microbes, explaining the worsening of IBD in patients on IL-17 inhibitors.10 These adverse effects illustrate the complicated and varied roles biologic medications play in immunologic response.

Given that TH1 and TH2 exert opposing immune mechanisms, it is uncommon for psoriasis and AD to coexist in a single patient. However, patients who exhibit concurrent findings may represent a unique population in which psoriasis and AD coexist, perhaps because of an underlying genetic predisposition. Moreover, targeted treatment of pathways unique to these disease processes may result in paradoxical flaring of the nontargeted pathway. It also is possible that inhibition of a specific T-cell pathway in a subset of patients will result in an immunologic imbalance, favoring increased activity of the opposing pathway in the absence of coexisting disease. In the case presented here, the findings may be explained by secukinumab’s inhibition of TH1/TH17-mediated inflammation, which resulted in a shift to a TH2-mediated inflammatory response manifesting as AD, as well as dupilumab’s inhibition of TH2-mediated inflammation, which caused a shift back to TH1-mediated inflammatory pathways. Additionally, for patients with changing morphologies exacerbated by biologic medications, alternative diagnoses, such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, may be considered.

Conclusion

We report an unusual case of secukinumab-induced AD in a patient with psoriasis that resolved following several months of treatment with dupilumab and a tapering dose of prednisone. Subsequently, this same patient developed re-emergence of psoriatic lesions with continued use of dupilumab, which was eventually discontinued by the patient despite appropriate disease control. In addition to illustrating the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of 2 common inflammatory dermatologic conditions, this case highlights how pharmacologic interventions targeted at specific immunologic pathways may have unintended consequences. Further investigation into the effects of targeted biologics on the TH1/TH2 immune axis is warranted to better understand the mechanism and possible implications of the phenotypic switching presented in this case.

- Diani M, Altomare G, Reali E. T helper cell subsets in clinical manifestations of psoriasis. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:7692024.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326-338.

- van der Heijden FL, Wierenga EA, Bos JD, et al. High frequency of IL-4-producing CD4+ allergen-specific T lymphocytes in atopic dermatitis lesional skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:389-394.

- Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130-139.

- Lai FYX, Higgins E, Smith CH, et al. Morphologic switch from psoriasiform to eczematous dermatitis after anti-IL-17 therapy: a case series. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1082-1084.

- Varma A, Levitt J. Dupilumab-induced phenotype switching from atopic dermatitis to psoriasis. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:217-218.

- Ling Y, Puel A. IL-17 and infections. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105(suppl 1):34-40.

- Saunte DM, Mrowietz U, Puig L, et al. Candida infections in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors and their practical management. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:47-62.

- Hölttä V, Klemetti P, Sipponen T, et al. IL-23/IL-17 immunity as a hallmark of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1175-1184.

- Smith MK, Pai J, Panaccione R, et al. Crohn’s-like disease in a patient exposed to anti-interleukin-17 blockade (ixekizumab) for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:162.

Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory skin condition associated with notable elevation in helper T cell (TH) production of TH1/TH17-mediated inflammatory cytokines, including IL-17A.1 Upon binding of IL-17A to IL-17 receptors in the skin, an inflammatory cascade is triggered, resulting in the classic clinical appearance of psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis often is managed by suppressing TH1/TH17-mediated inflammation using targeted immune therapy such as secukinumab, an IL-17A inhibitor.2 Atopic dermatitis (AD), another chronic inflammatory dermatosis, is associated with substantial elevation in TH2-mediated inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4.3 Dupilumab, which interacts with IL-4R, disrupts the IL-4 and IL-13 signaling pathways and demonstrates considerable efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe AD.4

A case series has shown that suppression of the TH1/TH17-mediated inflammation of psoriasis may paradoxically result in the development of TH2-mediated AD.5 Similarly, a recent case report described a patient who developed psoriasis following treatment of AD with dupilumab.6 Herein, we describe a patient with a history of psoriasis that was well controlled with secukinumab who developed severe refractory erythrodermic AD that resolved with dupilumab treatment. Following clearance of AD with dupilumab, he exhibited psoriasis recurrence.

Case Report

A 39-year-old man with a lifelong history of psoriasis was admitted to the hospital for management of severe erythroderma. Four years prior, secukinumab was initiated for treatment of psoriasis, resulting in excellent clinical response. He discontinued secukinumab after 2 years of treatment because of insurance coverage issues and managed his condition with only topical corticosteroids. He restarted secukinumab 10 months before admission because of a psoriasis flare. Shortly after resuming secukinumab, he developed a severe exfoliative erythroderma that was not responsive to corticosteroids, etanercept, methotrexate, or ustekinumab.

On initial presentation, physical examination revealed diffuse erythema and scaling with associated edema of the face, trunk, and extremities (Figure 1). A biopsy from the patient’s right arm demonstrated a superficial perivascular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and scattered eosinophils consistent with spongiotic dermatitis (Figure 2). Cyclosporine 225 mg twice daily and topical corticosteroids were started.

Over the next several months, the patient had several admissions secondary to recurrent skin abscesses in the setting of refractory erythroderma. He underwent trials of infliximab, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, guselkumab, and acitretin with minimal improvement. He underwent an extensive laboratory and radiologic workup, which was notable for cyclical peripheral eosinophilia and elevated IgE levels correlating with the erythroderma flares. A second biopsy was obtained and continued to demonstrate changes consistent with AD.

Four months after the initial hospitalization, all psoriasis medications were stopped, and the patient was started on dupilumab 300 mg/2 mL every 2 weeks and an 8-week oral prednisone taper. This combination led to notable clinical improvement and resolution of peripheral eosinophilia. Several months after disease remission, he began to develop worsening erythema and pruritus on the trunk and extremities, followed by the development of new psoriatic lesions (Figure 3) with a biopsy consistent with psoriasis (Figure 4). The patient was continued on dupilumab, but cyclosporine was added. The patient self-discontinued dupilumab owing to injection-site discomfort and has been slowly weaning off oral cyclosporine with 1 to 2 remaining eczematous plaques and 1 to 2 psoriatic plaques managed by topical corticosteroids.

Comment

We present a patient with psoriasis that was well controlled on secukinumab who developed severe AD following treatment with secukinumab. The AD resolved following treatment with dupilumab and a tapering dose of prednisone. However, after several months of treatment with dupilumab alone, he began to develop psoriatic lesions again. This case supports findings in a case series describing the development of AD in patients with psoriasis treated with IL-17 inhibitors5 and a recent case report describing a patient with AD who developed psoriasis following treatment with an IL-4/IL-13 inhibitor.6

Recognized adverse effects demonstrate biologic medications’ contributions to both normal as well as aberrant immunologic responses. For example, IL-17 plays an essential role in innate and adaptive immune responses against infections at mucosal and cutaneous interfaces, as demonstrated by chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in patients with genetic defects in IL-17–related pathways.7 Similarly, in patients taking IL-17 antagonists, an increase in the incidence of Candida infections has been observed.8 In patients with concurrent psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), treatment with IL-17 inhibitors is contraindicated due to the risk of exacerbating the IBD. This observation is somewhat paradoxical, as increased IL-17 release by TH17 cells is implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD.9 Interestingly, it is now thought that IL-17 may play a protective role in T-cell–driven intestinal inflammation through induction of protective intestinal epithelial gene expression and increased mucosal defense against gut microbes, explaining the worsening of IBD in patients on IL-17 inhibitors.10 These adverse effects illustrate the complicated and varied roles biologic medications play in immunologic response.

Given that TH1 and TH2 exert opposing immune mechanisms, it is uncommon for psoriasis and AD to coexist in a single patient. However, patients who exhibit concurrent findings may represent a unique population in which psoriasis and AD coexist, perhaps because of an underlying genetic predisposition. Moreover, targeted treatment of pathways unique to these disease processes may result in paradoxical flaring of the nontargeted pathway. It also is possible that inhibition of a specific T-cell pathway in a subset of patients will result in an immunologic imbalance, favoring increased activity of the opposing pathway in the absence of coexisting disease. In the case presented here, the findings may be explained by secukinumab’s inhibition of TH1/TH17-mediated inflammation, which resulted in a shift to a TH2-mediated inflammatory response manifesting as AD, as well as dupilumab’s inhibition of TH2-mediated inflammation, which caused a shift back to TH1-mediated inflammatory pathways. Additionally, for patients with changing morphologies exacerbated by biologic medications, alternative diagnoses, such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, may be considered.

Conclusion

We report an unusual case of secukinumab-induced AD in a patient with psoriasis that resolved following several months of treatment with dupilumab and a tapering dose of prednisone. Subsequently, this same patient developed re-emergence of psoriatic lesions with continued use of dupilumab, which was eventually discontinued by the patient despite appropriate disease control. In addition to illustrating the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of 2 common inflammatory dermatologic conditions, this case highlights how pharmacologic interventions targeted at specific immunologic pathways may have unintended consequences. Further investigation into the effects of targeted biologics on the TH1/TH2 immune axis is warranted to better understand the mechanism and possible implications of the phenotypic switching presented in this case.

Psoriasis vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory skin condition associated with notable elevation in helper T cell (TH) production of TH1/TH17-mediated inflammatory cytokines, including IL-17A.1 Upon binding of IL-17A to IL-17 receptors in the skin, an inflammatory cascade is triggered, resulting in the classic clinical appearance of psoriasis. Moderate to severe psoriasis often is managed by suppressing TH1/TH17-mediated inflammation using targeted immune therapy such as secukinumab, an IL-17A inhibitor.2 Atopic dermatitis (AD), another chronic inflammatory dermatosis, is associated with substantial elevation in TH2-mediated inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-4.3 Dupilumab, which interacts with IL-4R, disrupts the IL-4 and IL-13 signaling pathways and demonstrates considerable efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe AD.4

A case series has shown that suppression of the TH1/TH17-mediated inflammation of psoriasis may paradoxically result in the development of TH2-mediated AD.5 Similarly, a recent case report described a patient who developed psoriasis following treatment of AD with dupilumab.6 Herein, we describe a patient with a history of psoriasis that was well controlled with secukinumab who developed severe refractory erythrodermic AD that resolved with dupilumab treatment. Following clearance of AD with dupilumab, he exhibited psoriasis recurrence.

Case Report

A 39-year-old man with a lifelong history of psoriasis was admitted to the hospital for management of severe erythroderma. Four years prior, secukinumab was initiated for treatment of psoriasis, resulting in excellent clinical response. He discontinued secukinumab after 2 years of treatment because of insurance coverage issues and managed his condition with only topical corticosteroids. He restarted secukinumab 10 months before admission because of a psoriasis flare. Shortly after resuming secukinumab, he developed a severe exfoliative erythroderma that was not responsive to corticosteroids, etanercept, methotrexate, or ustekinumab.

On initial presentation, physical examination revealed diffuse erythema and scaling with associated edema of the face, trunk, and extremities (Figure 1). A biopsy from the patient’s right arm demonstrated a superficial perivascular inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes, histiocytes, and scattered eosinophils consistent with spongiotic dermatitis (Figure 2). Cyclosporine 225 mg twice daily and topical corticosteroids were started.

Over the next several months, the patient had several admissions secondary to recurrent skin abscesses in the setting of refractory erythroderma. He underwent trials of infliximab, corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, guselkumab, and acitretin with minimal improvement. He underwent an extensive laboratory and radiologic workup, which was notable for cyclical peripheral eosinophilia and elevated IgE levels correlating with the erythroderma flares. A second biopsy was obtained and continued to demonstrate changes consistent with AD.

Four months after the initial hospitalization, all psoriasis medications were stopped, and the patient was started on dupilumab 300 mg/2 mL every 2 weeks and an 8-week oral prednisone taper. This combination led to notable clinical improvement and resolution of peripheral eosinophilia. Several months after disease remission, he began to develop worsening erythema and pruritus on the trunk and extremities, followed by the development of new psoriatic lesions (Figure 3) with a biopsy consistent with psoriasis (Figure 4). The patient was continued on dupilumab, but cyclosporine was added. The patient self-discontinued dupilumab owing to injection-site discomfort and has been slowly weaning off oral cyclosporine with 1 to 2 remaining eczematous plaques and 1 to 2 psoriatic plaques managed by topical corticosteroids.

Comment

We present a patient with psoriasis that was well controlled on secukinumab who developed severe AD following treatment with secukinumab. The AD resolved following treatment with dupilumab and a tapering dose of prednisone. However, after several months of treatment with dupilumab alone, he began to develop psoriatic lesions again. This case supports findings in a case series describing the development of AD in patients with psoriasis treated with IL-17 inhibitors5 and a recent case report describing a patient with AD who developed psoriasis following treatment with an IL-4/IL-13 inhibitor.6

Recognized adverse effects demonstrate biologic medications’ contributions to both normal as well as aberrant immunologic responses. For example, IL-17 plays an essential role in innate and adaptive immune responses against infections at mucosal and cutaneous interfaces, as demonstrated by chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis in patients with genetic defects in IL-17–related pathways.7 Similarly, in patients taking IL-17 antagonists, an increase in the incidence of Candida infections has been observed.8 In patients with concurrent psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), treatment with IL-17 inhibitors is contraindicated due to the risk of exacerbating the IBD. This observation is somewhat paradoxical, as increased IL-17 release by TH17 cells is implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD.9 Interestingly, it is now thought that IL-17 may play a protective role in T-cell–driven intestinal inflammation through induction of protective intestinal epithelial gene expression and increased mucosal defense against gut microbes, explaining the worsening of IBD in patients on IL-17 inhibitors.10 These adverse effects illustrate the complicated and varied roles biologic medications play in immunologic response.

Given that TH1 and TH2 exert opposing immune mechanisms, it is uncommon for psoriasis and AD to coexist in a single patient. However, patients who exhibit concurrent findings may represent a unique population in which psoriasis and AD coexist, perhaps because of an underlying genetic predisposition. Moreover, targeted treatment of pathways unique to these disease processes may result in paradoxical flaring of the nontargeted pathway. It also is possible that inhibition of a specific T-cell pathway in a subset of patients will result in an immunologic imbalance, favoring increased activity of the opposing pathway in the absence of coexisting disease. In the case presented here, the findings may be explained by secukinumab’s inhibition of TH1/TH17-mediated inflammation, which resulted in a shift to a TH2-mediated inflammatory response manifesting as AD, as well as dupilumab’s inhibition of TH2-mediated inflammation, which caused a shift back to TH1-mediated inflammatory pathways. Additionally, for patients with changing morphologies exacerbated by biologic medications, alternative diagnoses, such as cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, may be considered.

Conclusion

We report an unusual case of secukinumab-induced AD in a patient with psoriasis that resolved following several months of treatment with dupilumab and a tapering dose of prednisone. Subsequently, this same patient developed re-emergence of psoriatic lesions with continued use of dupilumab, which was eventually discontinued by the patient despite appropriate disease control. In addition to illustrating the underlying pathophysiologic mechanisms of 2 common inflammatory dermatologic conditions, this case highlights how pharmacologic interventions targeted at specific immunologic pathways may have unintended consequences. Further investigation into the effects of targeted biologics on the TH1/TH2 immune axis is warranted to better understand the mechanism and possible implications of the phenotypic switching presented in this case.

- Diani M, Altomare G, Reali E. T helper cell subsets in clinical manifestations of psoriasis. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:7692024.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326-338.

- van der Heijden FL, Wierenga EA, Bos JD, et al. High frequency of IL-4-producing CD4+ allergen-specific T lymphocytes in atopic dermatitis lesional skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:389-394.

- Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130-139.

- Lai FYX, Higgins E, Smith CH, et al. Morphologic switch from psoriasiform to eczematous dermatitis after anti-IL-17 therapy: a case series. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1082-1084.

- Varma A, Levitt J. Dupilumab-induced phenotype switching from atopic dermatitis to psoriasis. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:217-218.

- Ling Y, Puel A. IL-17 and infections. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105(suppl 1):34-40.

- Saunte DM, Mrowietz U, Puig L, et al. Candida infections in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors and their practical management. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:47-62.

- Hölttä V, Klemetti P, Sipponen T, et al. IL-23/IL-17 immunity as a hallmark of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1175-1184.

- Smith MK, Pai J, Panaccione R, et al. Crohn’s-like disease in a patient exposed to anti-interleukin-17 blockade (ixekizumab) for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:162.

- Diani M, Altomare G, Reali E. T helper cell subsets in clinical manifestations of psoriasis. J Immunol Res. 2016;2016:7692024.

- Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M, et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis—results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:326-338.

- van der Heijden FL, Wierenga EA, Bos JD, et al. High frequency of IL-4-producing CD4+ allergen-specific T lymphocytes in atopic dermatitis lesional skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;97:389-394.

- Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:130-139.

- Lai FYX, Higgins E, Smith CH, et al. Morphologic switch from psoriasiform to eczematous dermatitis after anti-IL-17 therapy: a case series. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:1082-1084.

- Varma A, Levitt J. Dupilumab-induced phenotype switching from atopic dermatitis to psoriasis. JAAD Case Rep. 2020;6:217-218.

- Ling Y, Puel A. IL-17 and infections. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105(suppl 1):34-40.

- Saunte DM, Mrowietz U, Puig L, et al. Candida infections in patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis treated with interleukin-17 inhibitors and their practical management. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:47-62.

- Hölttä V, Klemetti P, Sipponen T, et al. IL-23/IL-17 immunity as a hallmark of Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1175-1184.

- Smith MK, Pai J, Panaccione R, et al. Crohn’s-like disease in a patient exposed to anti-interleukin-17 blockade (ixekizumab) for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: a case report. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019;19:162.

Practice Points

- Treatment of psoriasis vulgaris, a helper T cell TH1/TH17-mediated skin condition, with secukinumab may result in phenotypic switching to TH2-mediated atopic dermatitis.

- Atopic dermatitis responds well to dupilumab but may result in phenotypic switching to psoriasis.

- Biologic therapies targeted at specific immunologic pathways may have unintended consequences on the TH1/TH2 immune axis.

Anecdote Increases Patient Willingness to Take a Biologic Medication for Psoriasis

Biologic medications are highly effective in treating moderate to severe psoriasis, yet many patients are apprehensive about taking a biologic medication for a variety of reasons, such as hearing negative information about the drug from friends or family, being nervous about injection, or seeing the drug or its side effects negatively portrayed in the media.1-3 Because biologic medications are costly, many patients may fear needing to discontinue use of the medication owing to lack of affordability, which may result in subsequent rebound of psoriasis. Because patients’ fear of a drug is inherently subjective, it can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence. By understanding what information increases patients’ confidence in their willingness to take a biologic medication, patients may be more willing to initiate use of the drug and improve treatment outcomes.

There are mixed findings about whether statistical evidence or an anecdote is more effective in persuasion.4-6 The specific context in which the persuasion takes place may be important in determining which method is superior. In most nonthreatening situations, people appear to be more easily persuaded by statistical evidence rather than an anecdote. However, in circumstances where emotional engagement is high, such as regarding one’s own health, an anecdote tends to be more persuasive compared to statistical evidence.7 The purpose of this study was to evaluate patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for the management of their psoriasis if presented with either clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or both.

Methods

Patient Inclusion Criteria

Following Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional review board approval, a prospective parallel-arm survey study was performed on eligible patients 18 years or older with a self-reported diagnosis of psoriasis. Patients were required to have a working knowledge of English and not have been previously prescribed a biologic medication for their psoriasis. If patients did not meet inclusion criteria after answering the survey eligibility screening questions, then they were unable to complete the remainder of the survey and were excluded from the analysis.

Survey Administration

A total of 222 patients were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing platform. (Amazon Mechanical Turk is a validated tool in conducting research in psychology and other social sciences and is considered as diverse as and perhaps more representative than traditional samples.8,9) Patients received a fact sheet and were taken to the survey hosted on Qualtrics, a secure web-based survey software that supports data collection for research studies. Amazon Mechanical Turk requires some amount of compensation to patients; therefore, recruited patients were compensated $0.03.

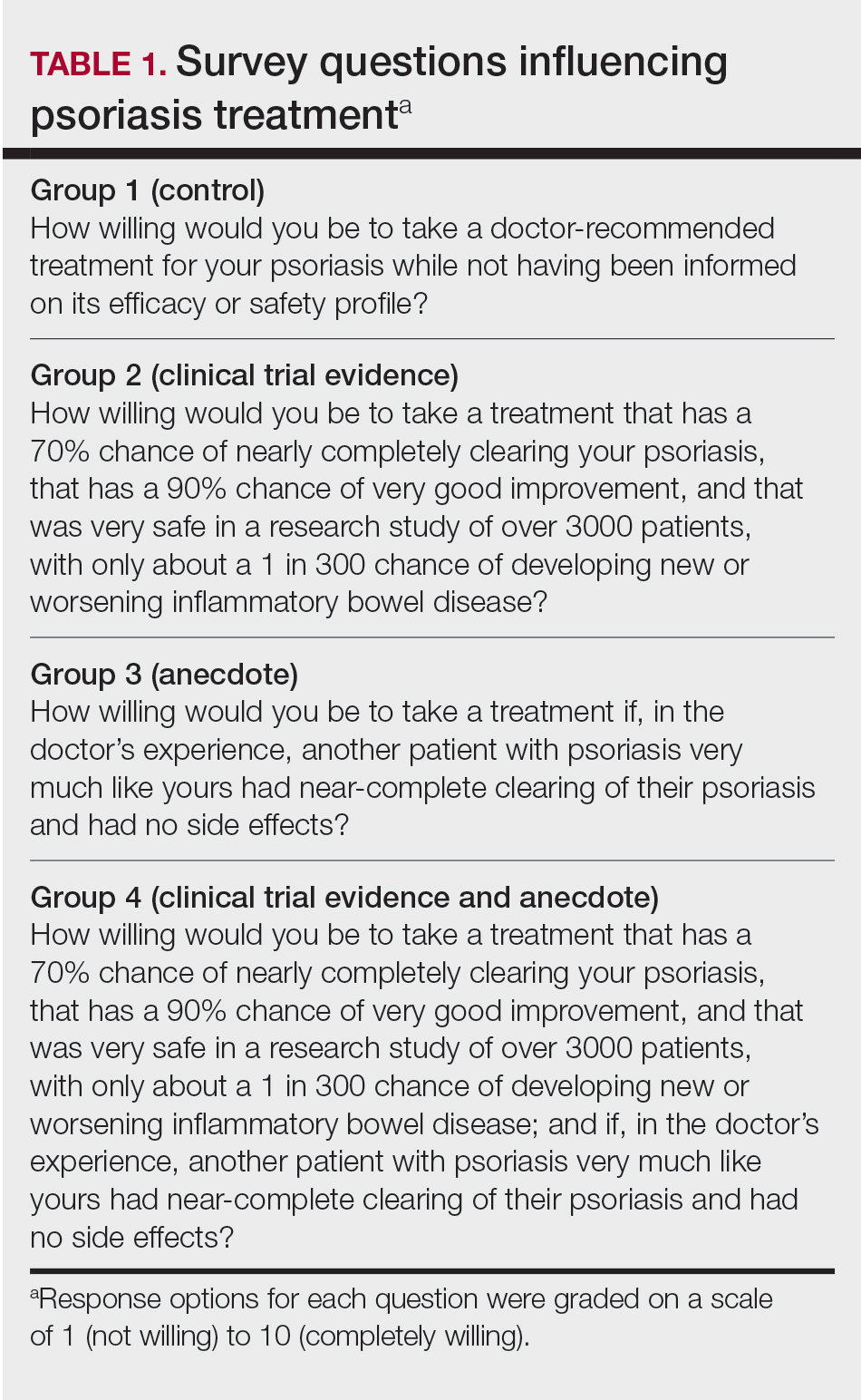

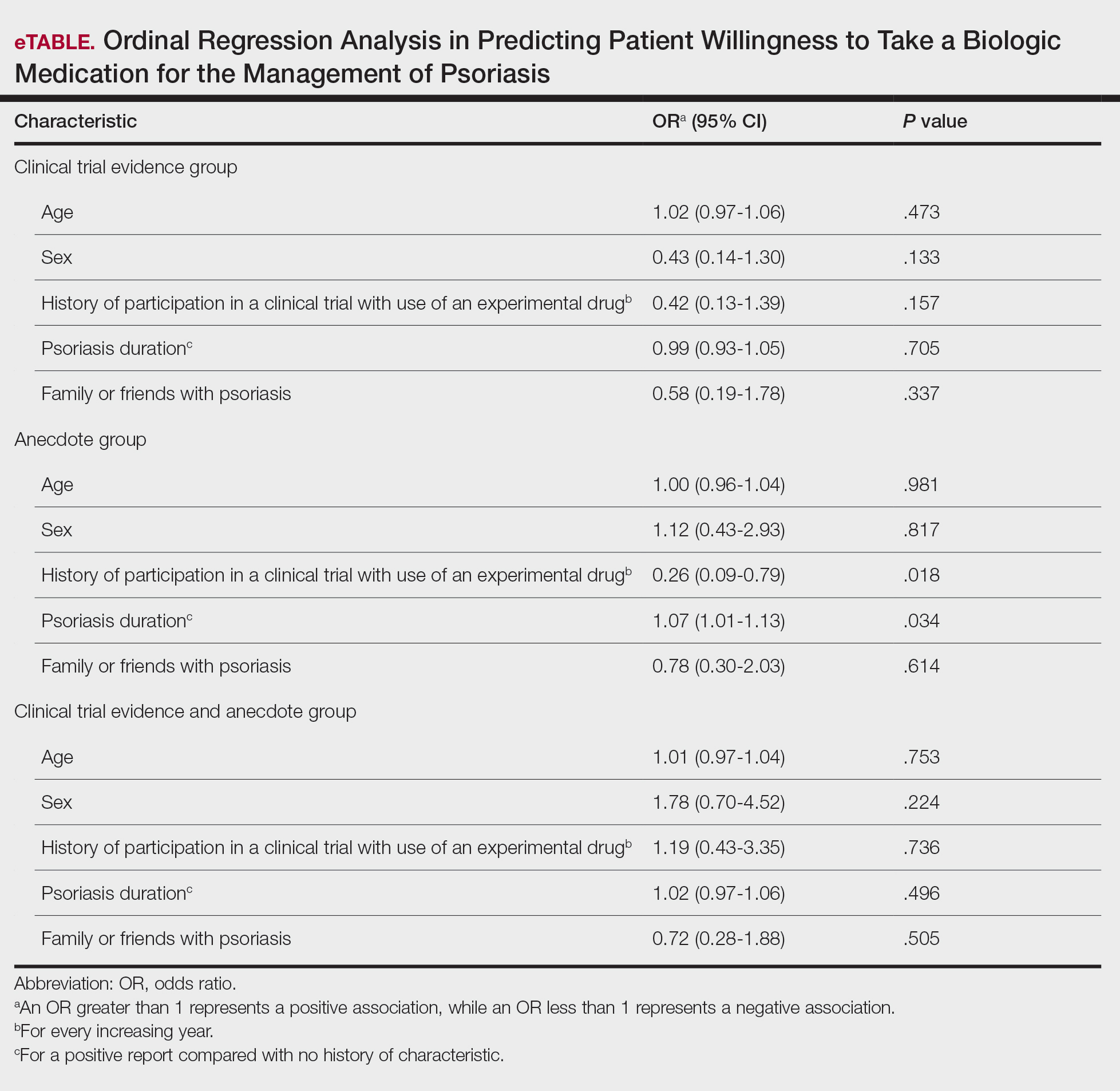

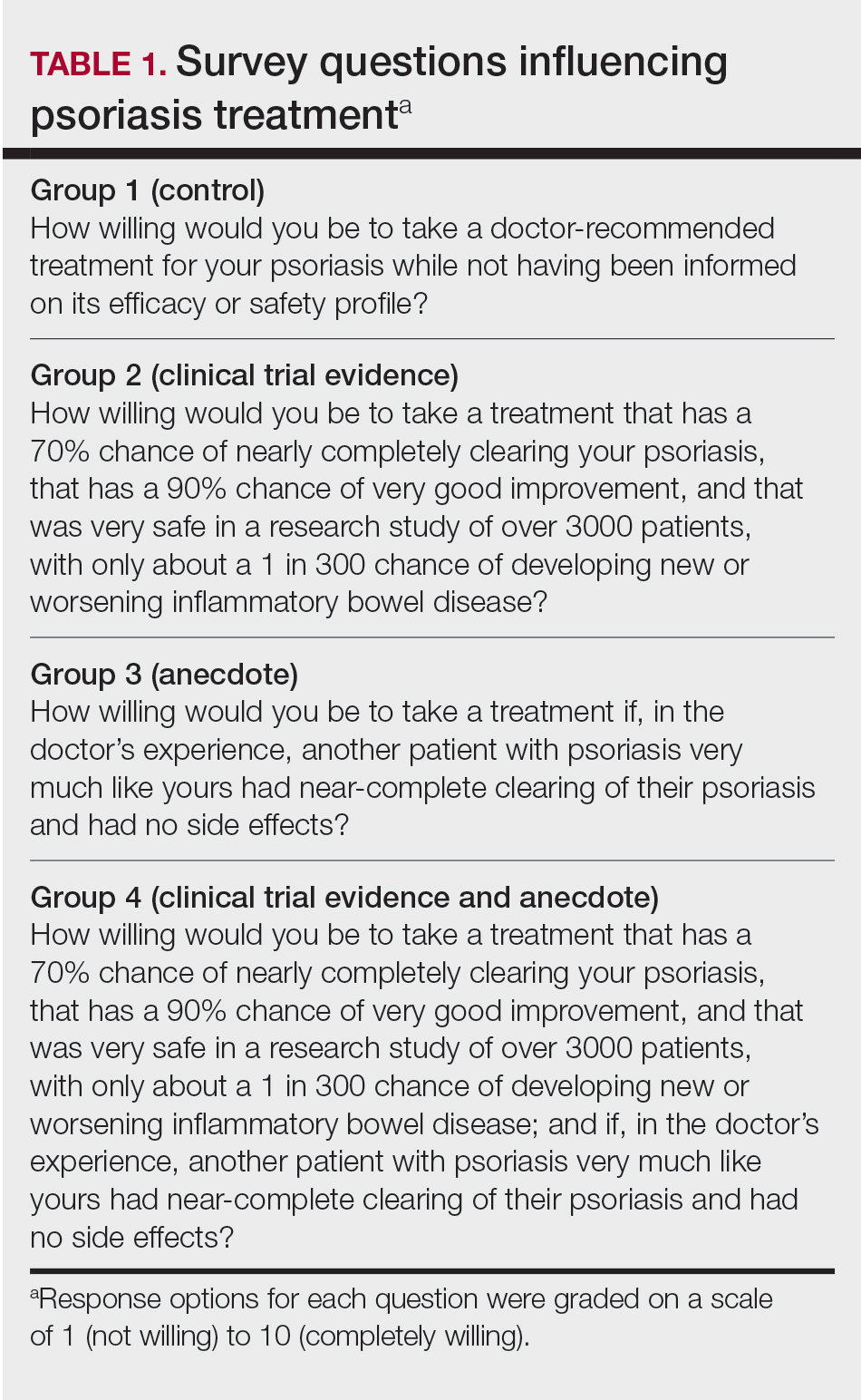

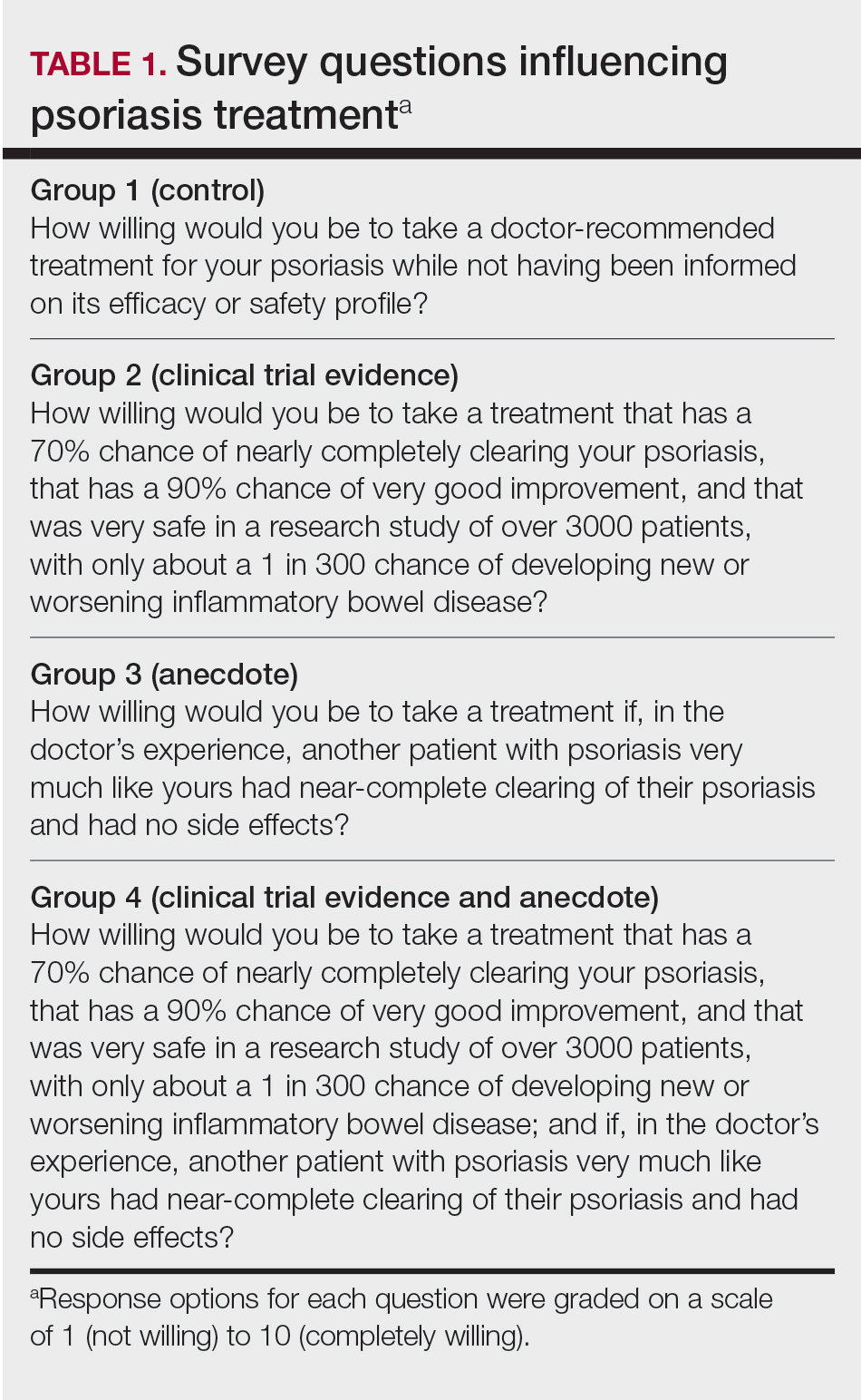

Statistical Analysis

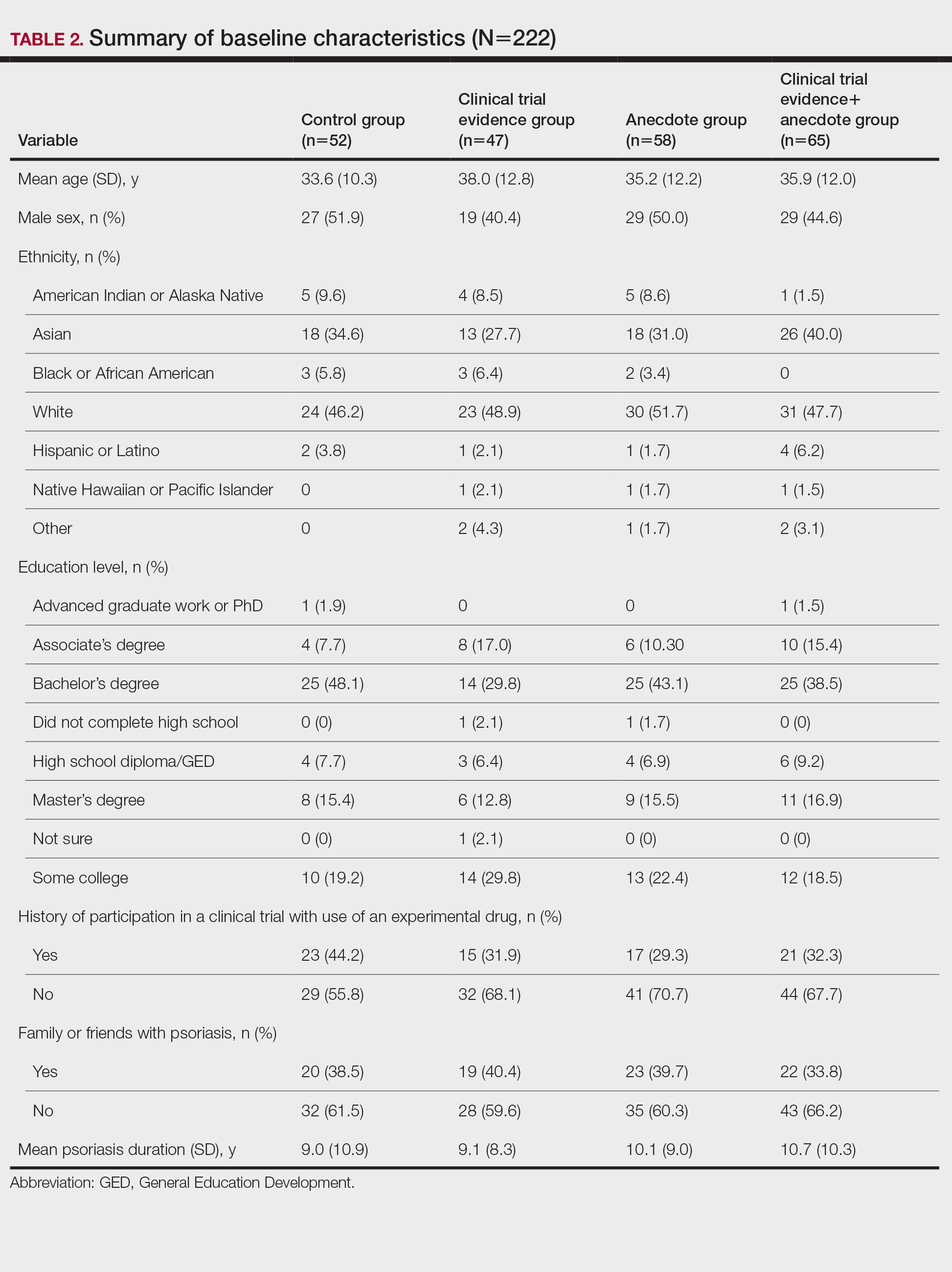

Patients were randomized using SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM) in a 1:1 ratio to assess how willing they would be to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis if presented with one of the following: (1) a control that queried patients about their willingness to take treatment without having been informed on its efficacy or safety, (2) clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, (3) an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or (4) both clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety and an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience (Table 1). Demographic information including sex, age, ethnicity, and education level was collected, in addition to other baseline characteristics such as having friends or family with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis.

Outcome measures were recorded as patients’ responses regarding their willingness to take a biologic medication on a 10-point Likert scale (1=not willing; 10=completely willing). Scores were treated as ordinal data and evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn test. Descriptive statistics were tabulated on all variables. Baseline characteristics were analyzed using a 2-tailed, unpaired t test for continuous variables and the χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Ordinal linear regression analysis was performed to determine whether reported willingness to take a biologic medication was related to patients’ demographics, including age, sex, having family or friends with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis. Answers on the ordinal scale were binarized. The data were analyzed with SPSS Statistics version 23.0.

Results

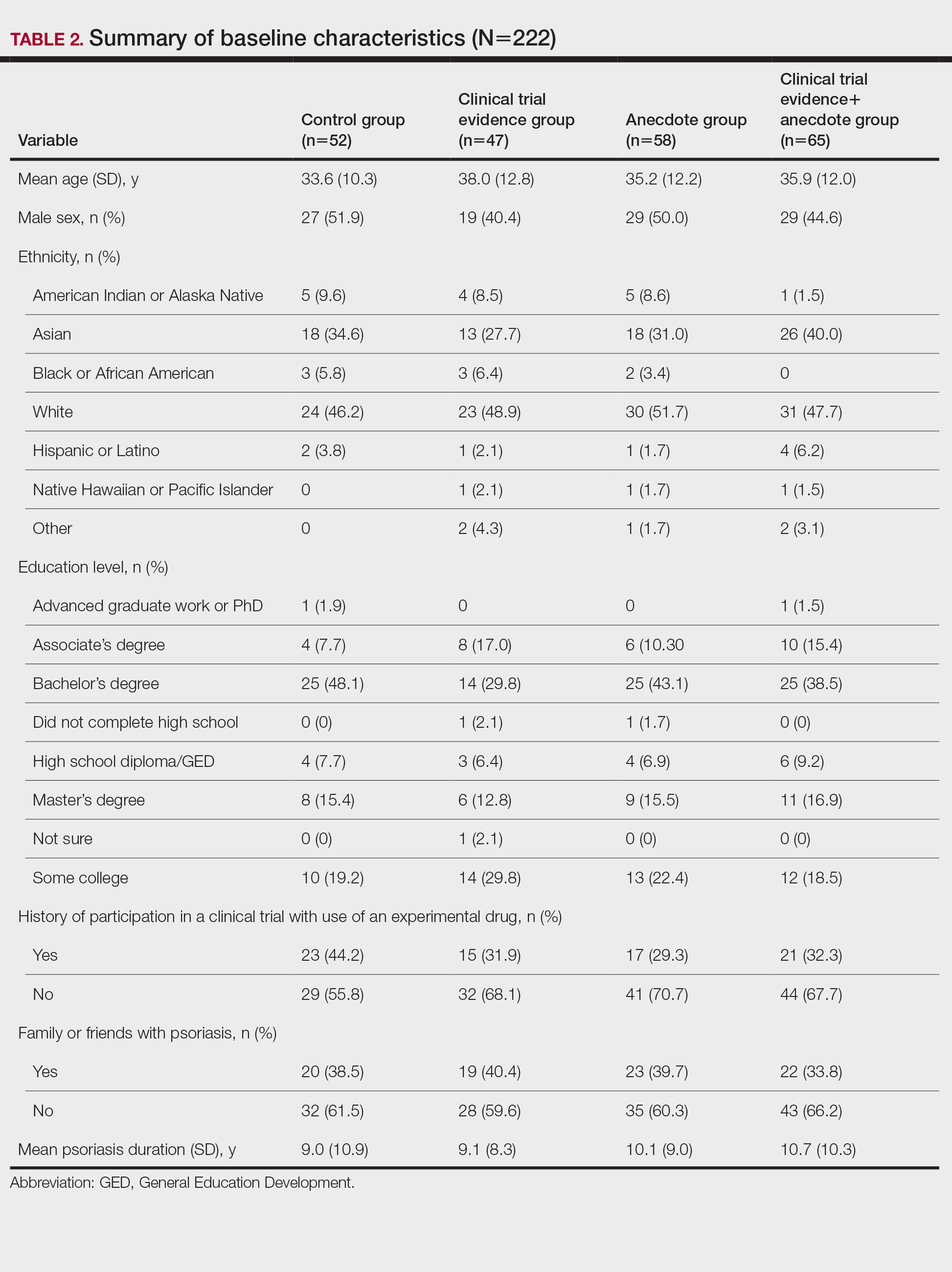

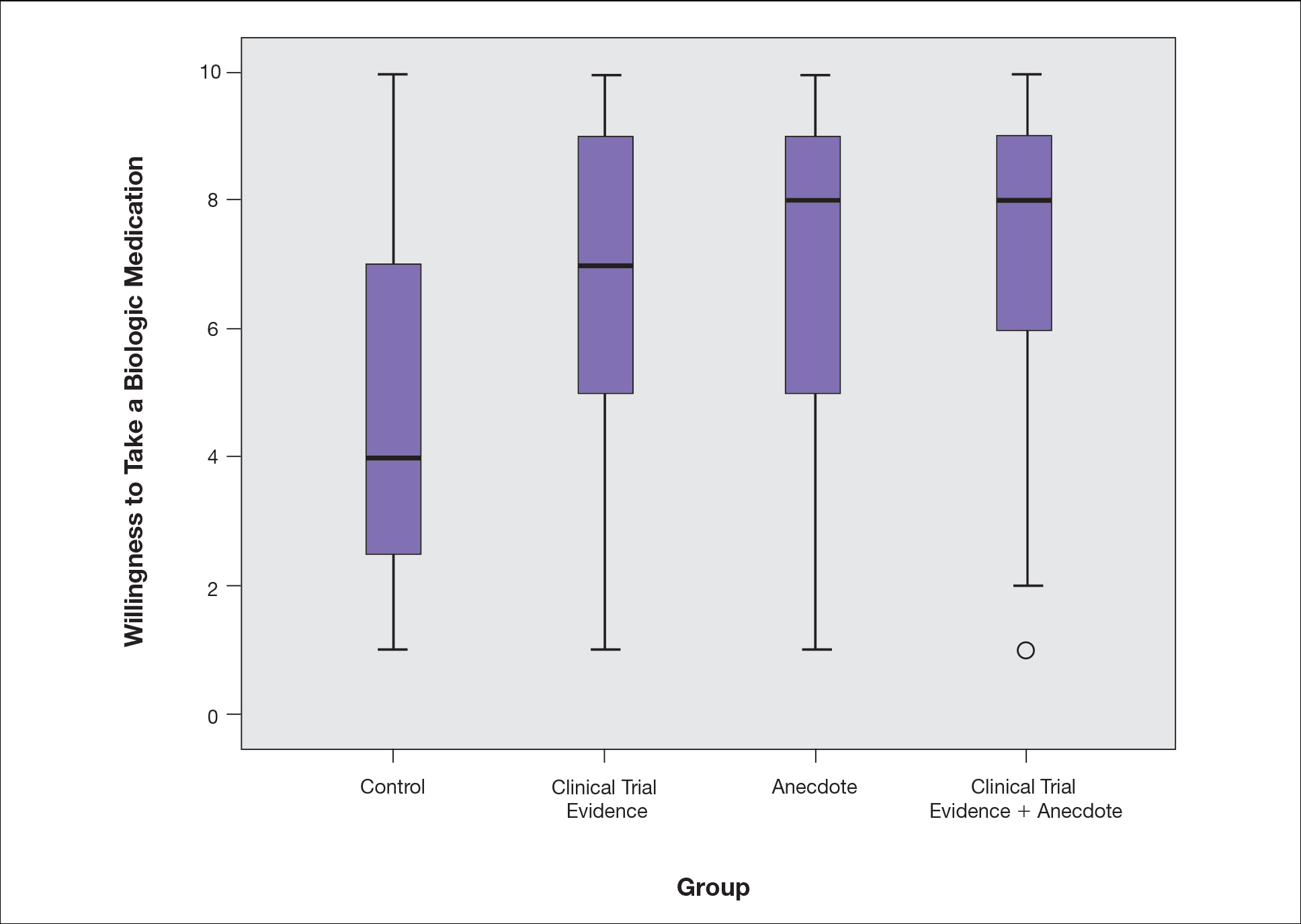

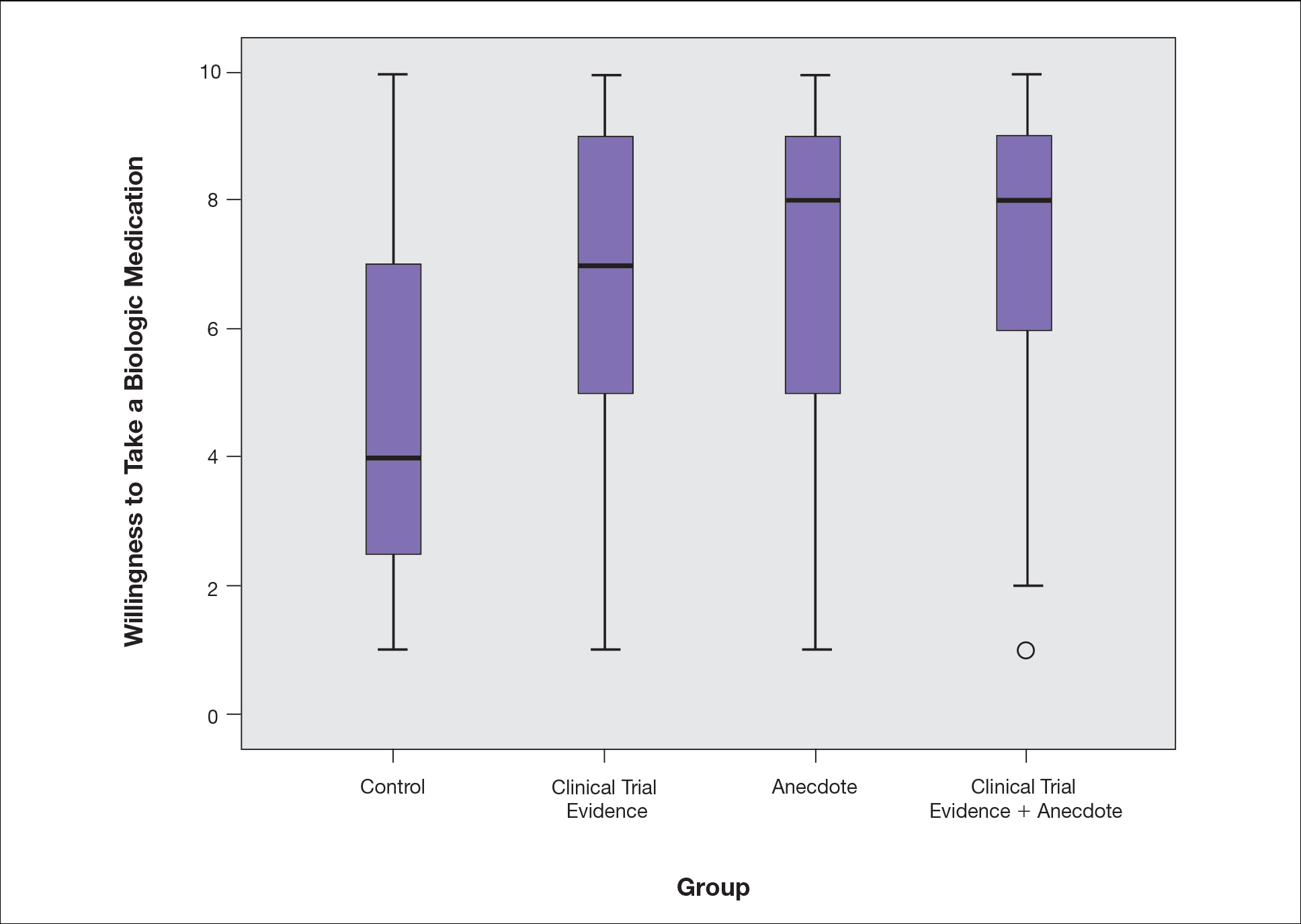

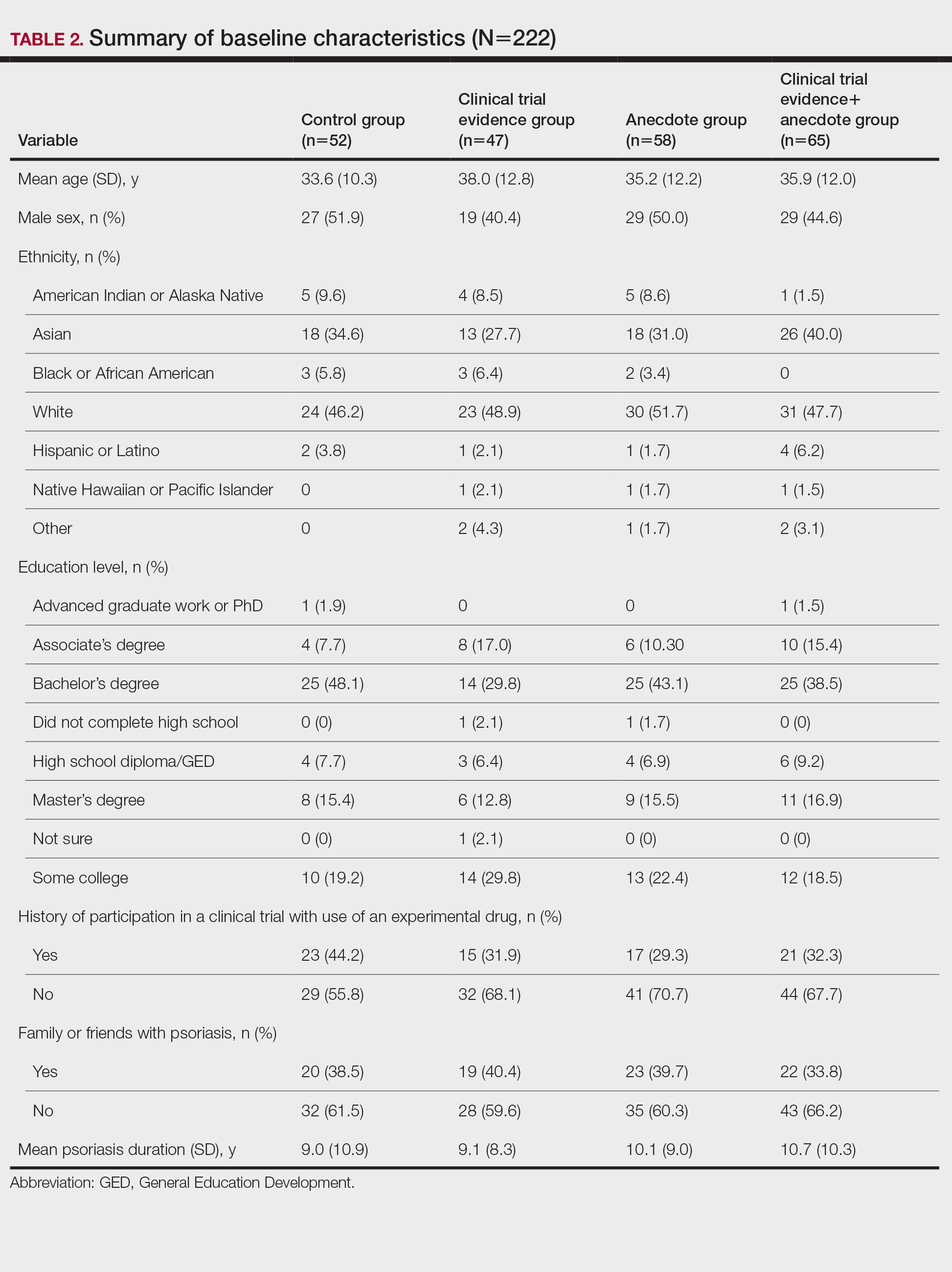

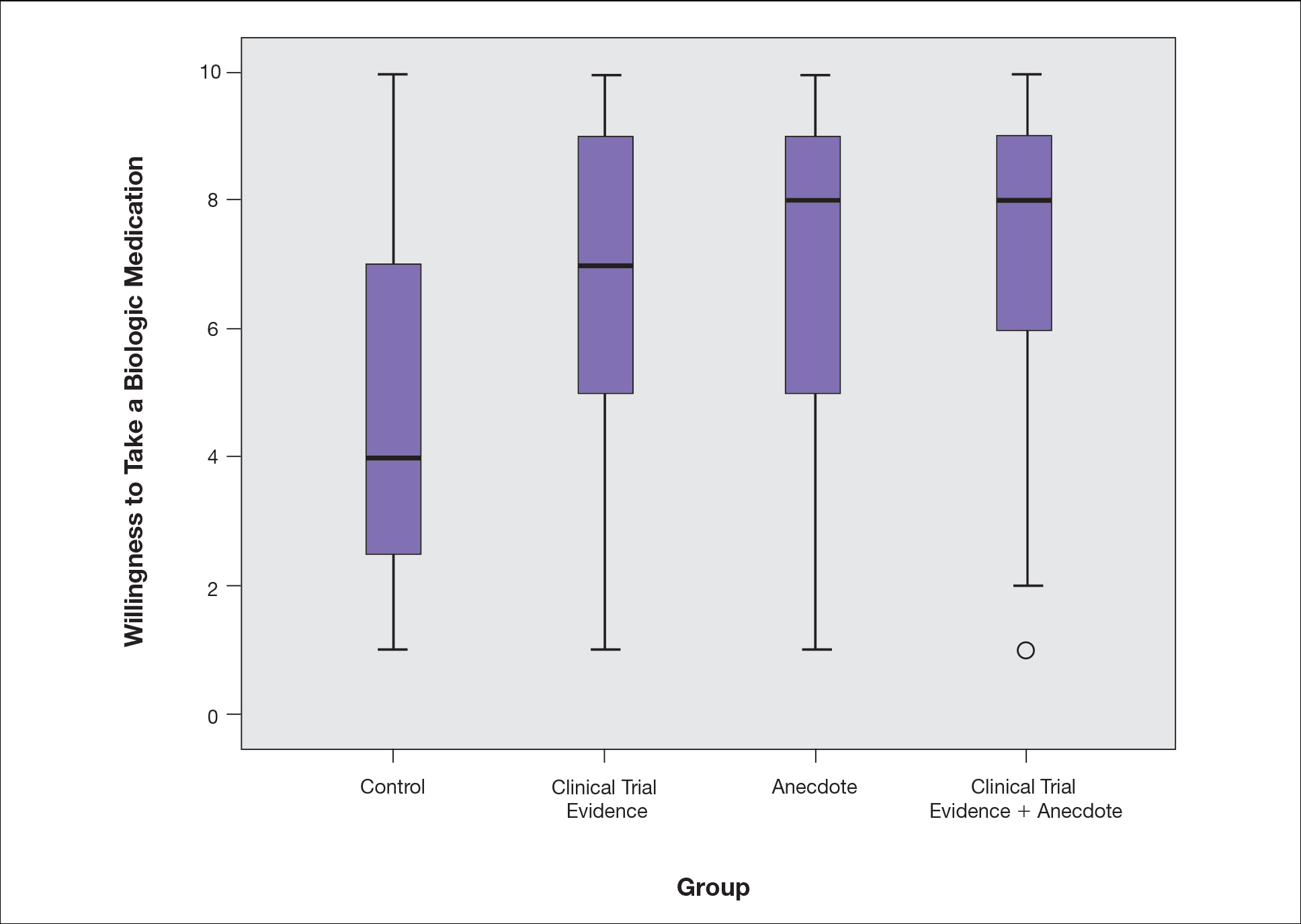

There were no statistically significant differences among the baseline characteristics of the 4 information assignment groups (Table 2). Patients in the control group not given either clinical trial evidence of a biologic medication’s efficacy and safety or anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience had the lowest reported willingness to take treatment (median, 4.0)(Figure).

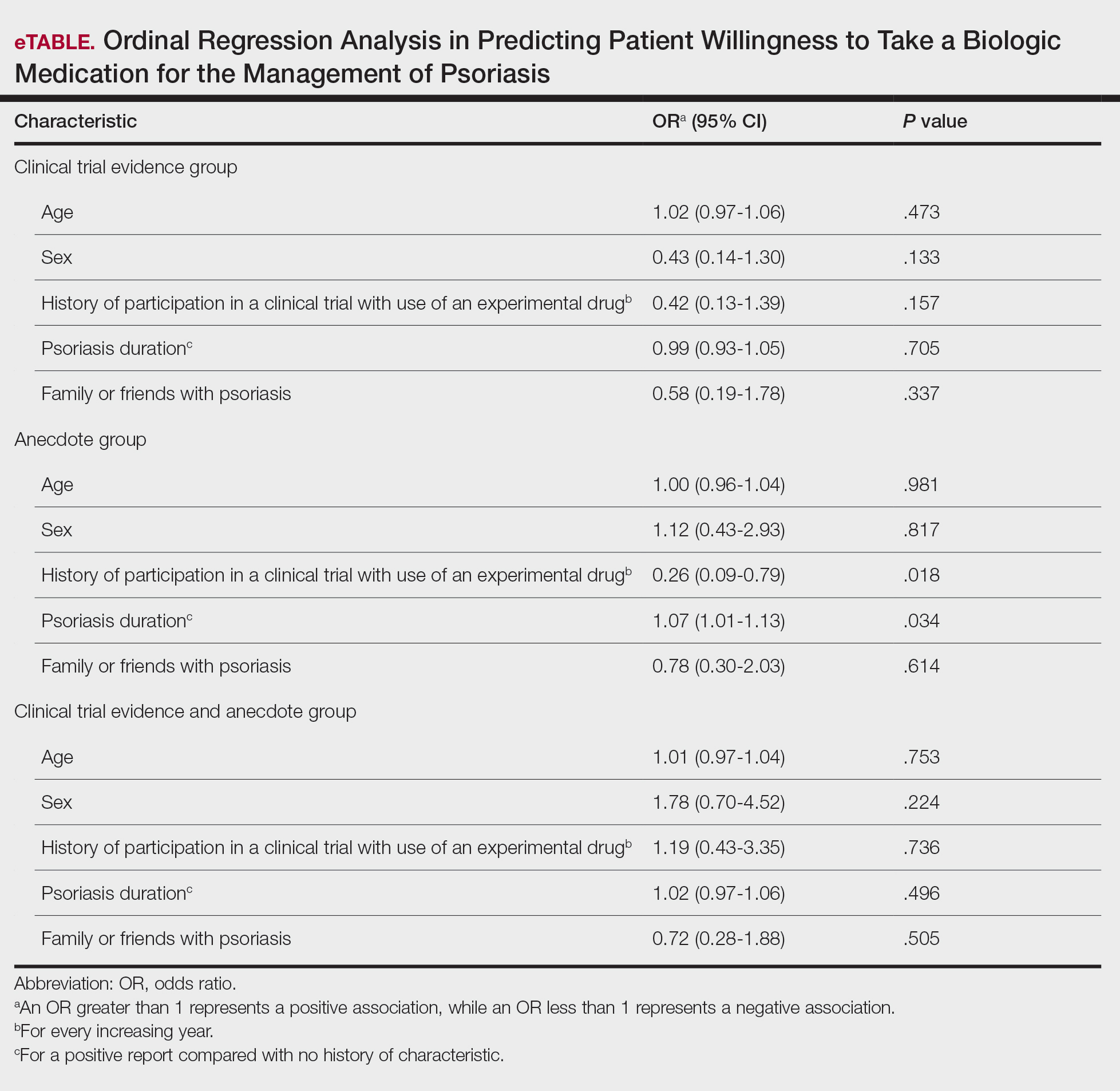

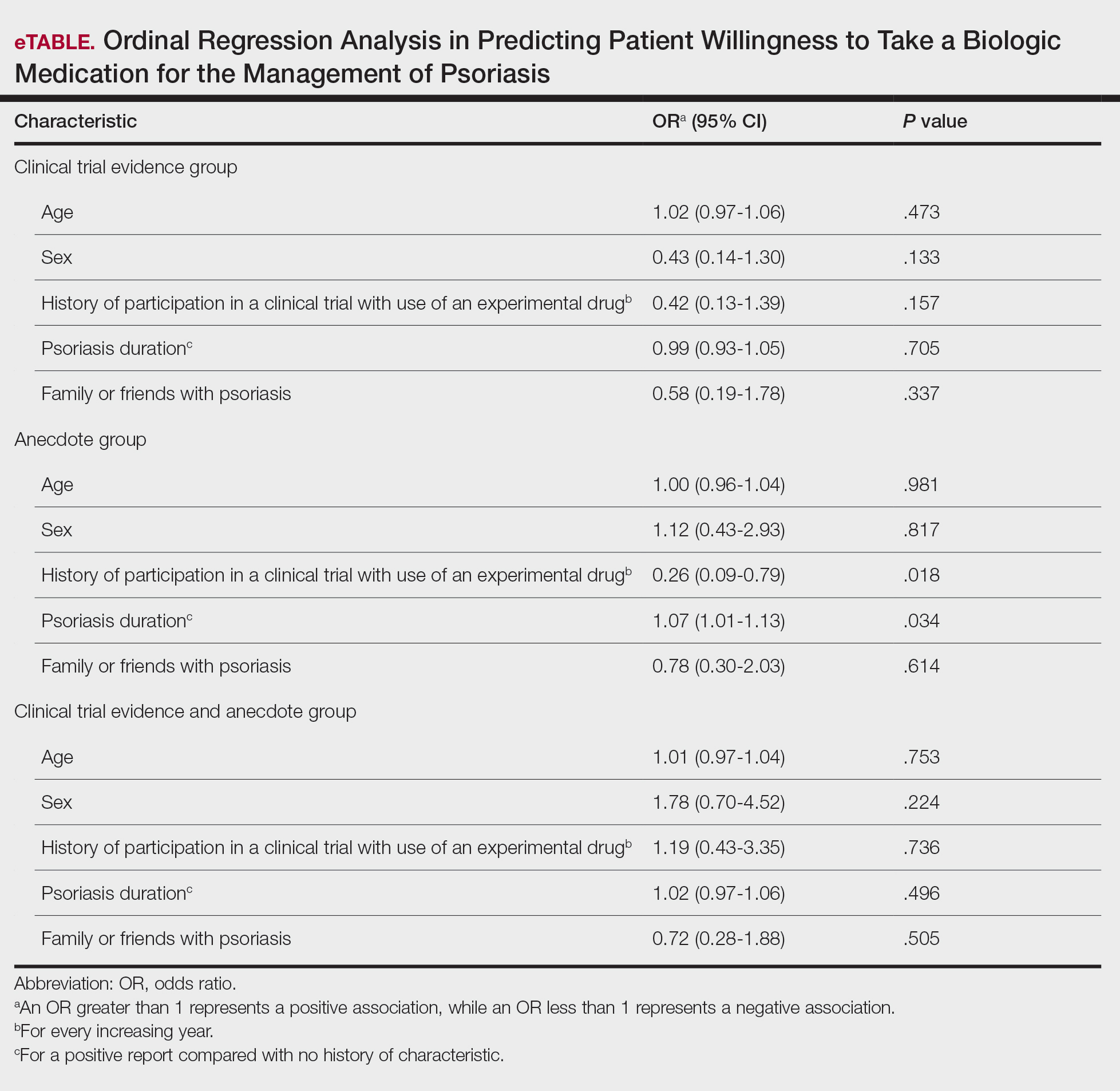

Based on regression analysis, age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis were not significantly associated with patients’ responses (eTable). The number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis (P=.034) and history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug (P=.018) were significantly associated with the willingness of patients presented with an anecdote to take a biologic medication.

Comment

Anecdotal Reassurance

The presentation of clinical trial and/or anecdotal evidence had a strong effect on patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis. Human perception of a treatment is inherently subjective, and such perceptions can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence.1 Across the population we studied, presenting a brief anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience is a quick and efficient means—and as or more effective as giving details on efficacy and safety—to help patients decide to take a treatment for their psoriasis.

Anecdotal reassurance is powerful. Both health care providers and patients have a natural tendency to focus on anecdotal experiences rather than statistical reasoning when making treatment decisions.10-12 Although negative anecdotal experiences may make patients unwilling to take a medication (or may make them overly desirous of an inappropriate treatment), clinicians can harness this psychological phenomenon to both increase patient willingness to take potentially beneficial treatments or to deter them from engaging in activities that can be harmful to their health, such as tanning and smoking.

Psoriasis Duration and Willingness to Take a Biologic Medication

In general, patient demographics did not appear to have an association with reported willingness to take a biologic medication for psoriasis. However, the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis had an effect on willingness to take a biologic medication, with patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis showing a higher willingness to take a treatment after being presented with an anecdote than patients with a shorter personal history of psoriasis. We can only speculate on the reasons why. Patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis may have tried and failed more treatments and therefore have a distrust in the validity of clinical trial evidence. These patients may feel their psoriasis is different than that of other clinical trial participants and thus may be more willing to rely on the success stories of individual patients.

Prior participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug was associated with a lower willingness to choose treatment after being presented with anecdotal reassurance. This finding may be attributable to these patients understanding the subjective nature of anecdotes and preferring more objective information in the form of randomized clinical trials in making treatment decisions. Overall, the presentation of evidence about the efficacy and safety of biologic medications in the treatment of psoriasis has a greater impact on patient decision-making than patients’ age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis.

Limitations

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. With closed-ended questions, patients were not able to explain their responses. In addition, hypothetical informational statements of a biologic’s efficacy and safety may not always imitate clinical reality. However, we believe the study is valid in exploring the power of an anecdote in influencing patients’ willingness to take biologic medications for psoriasis. Furthermore, educational level and ethnicity were excluded from the ordinal regression analysis because the assumption of parallel lines was not met.

Ethics Behind an Anecdote

An important consideration is the ethical implications of sharing an anecdote to guide patients’ perceptions of treatment and behavior. Although clinicians rely heavily on the available data to determine the best course of treatment, providing patients with comprehensive information on all risks and benefits is rarely, if ever, feasible. Moreover, even objective clinical data will inevitably be subjectively interpreted by patients. For example, describing a medication side effect as occurring in 1 in 100 patients may discourage patients from pursuing treatment, whereas describing that risk as not occurring in 99 in 100 patients may encourage patients, despite these 2 choices being mathematically identical.13 Because the subjective interpretation of data is inevitable, presenting patients with subjective information in the form of an anecdote to help them overcome fears of starting treatment and achieve their desired clinical outcomes may be one of the appropriate approaches to present what is objectively the best option, particularly if the anecdote is representative of the expected treatment response. Clinicians can harness this understanding of human psychology to better educate patients about their treatment options while fulfilling their ethical duty to act in their patients’ best interest.

Conclusion

Using an anecdote to help patients overcome fears of starting a biologic medication may be appropriate if the anecdote is reasonably representative of an expected treatment outcome. Patients should have an accurate understanding of the common risks and benefits of a medication for purposes of shared decision-making.

- Oussedik E, Cardwell LA, Patel NU, et al. An anchoring-based intervention to increase patient willingness to use injectable medication in psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:932-934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1271

- Brown KK, Rehmus WE, Kimball AB. Determining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:607-613. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.021

- Im H, Huh J. Does health information in mass media help or hurt patients? Investigation of potential negative influence of mass media health information on patients’ beliefs and medication regimen adherence. J Health Commun. 2017;22:214-222. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1261970

- Hornikx J. A review of experimental research on the relative persuasiveness of anecdotal, statistical, causal, and expert evidence. Studies Commun Sci. 2005;5:205-216.

- Allen M, Preiss RW. Comparing the persuasiveness of narrative and statistical evidence using meta-analysis. Int J Phytoremediation Commun Res Rep. 1997;14:125-131. doi:10.1080/08824099709388654

- Shen F, Sheer VC, Li R. Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: a meta-analysis. J Advert. 2015;44:105-113. doi:10.1080/00913367.2015.1018467

- Freling TH, Yang Z, Saini R, et al. When poignant stories outweigh cold hard facts: a meta-analysis of the anecdotal bias. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2020;160:51-67. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.01.006

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:3-5. doi:10.1177/1745691610393980

- Berry K, Butt M, Kirby JS. Influence of information framing on patient decisions to treat actinic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:421-426. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5245

- Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Reed M, et al. Personal, organizational, and market level influences on physicians’ practice patterns: results of a national survey of primary care physicians. Med Care. 2001;39:889-905. doi:10.1097/00005650-200108000-00014

- Borgida E, Nisbett RE. The differential impact of abstract vs. concrete information on decisions. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1977;7:258-271. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1977.tb00750.x

- Fagerlin A, Wang C, Ubel PA. Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people’s health care decisions: is a picture worth a thousand statistics? Med Decis Making. 2005;25:398-405. doi:10.1177/0272989X05278931

- Gurm HS, Litaker DG. Framing procedural risks to patients: Is 99% safe the same as a risk of 1 in 100? Acad Med. 2000;75:840-842. doi:10.1097/00001888-200008000-00018

Biologic medications are highly effective in treating moderate to severe psoriasis, yet many patients are apprehensive about taking a biologic medication for a variety of reasons, such as hearing negative information about the drug from friends or family, being nervous about injection, or seeing the drug or its side effects negatively portrayed in the media.1-3 Because biologic medications are costly, many patients may fear needing to discontinue use of the medication owing to lack of affordability, which may result in subsequent rebound of psoriasis. Because patients’ fear of a drug is inherently subjective, it can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence. By understanding what information increases patients’ confidence in their willingness to take a biologic medication, patients may be more willing to initiate use of the drug and improve treatment outcomes.

There are mixed findings about whether statistical evidence or an anecdote is more effective in persuasion.4-6 The specific context in which the persuasion takes place may be important in determining which method is superior. In most nonthreatening situations, people appear to be more easily persuaded by statistical evidence rather than an anecdote. However, in circumstances where emotional engagement is high, such as regarding one’s own health, an anecdote tends to be more persuasive compared to statistical evidence.7 The purpose of this study was to evaluate patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for the management of their psoriasis if presented with either clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or both.

Methods

Patient Inclusion Criteria

Following Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional review board approval, a prospective parallel-arm survey study was performed on eligible patients 18 years or older with a self-reported diagnosis of psoriasis. Patients were required to have a working knowledge of English and not have been previously prescribed a biologic medication for their psoriasis. If patients did not meet inclusion criteria after answering the survey eligibility screening questions, then they were unable to complete the remainder of the survey and were excluded from the analysis.

Survey Administration

A total of 222 patients were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing platform. (Amazon Mechanical Turk is a validated tool in conducting research in psychology and other social sciences and is considered as diverse as and perhaps more representative than traditional samples.8,9) Patients received a fact sheet and were taken to the survey hosted on Qualtrics, a secure web-based survey software that supports data collection for research studies. Amazon Mechanical Turk requires some amount of compensation to patients; therefore, recruited patients were compensated $0.03.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were randomized using SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM) in a 1:1 ratio to assess how willing they would be to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis if presented with one of the following: (1) a control that queried patients about their willingness to take treatment without having been informed on its efficacy or safety, (2) clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, (3) an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or (4) both clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety and an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience (Table 1). Demographic information including sex, age, ethnicity, and education level was collected, in addition to other baseline characteristics such as having friends or family with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis.

Outcome measures were recorded as patients’ responses regarding their willingness to take a biologic medication on a 10-point Likert scale (1=not willing; 10=completely willing). Scores were treated as ordinal data and evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn test. Descriptive statistics were tabulated on all variables. Baseline characteristics were analyzed using a 2-tailed, unpaired t test for continuous variables and the χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Ordinal linear regression analysis was performed to determine whether reported willingness to take a biologic medication was related to patients’ demographics, including age, sex, having family or friends with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis. Answers on the ordinal scale were binarized. The data were analyzed with SPSS Statistics version 23.0.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences among the baseline characteristics of the 4 information assignment groups (Table 2). Patients in the control group not given either clinical trial evidence of a biologic medication’s efficacy and safety or anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience had the lowest reported willingness to take treatment (median, 4.0)(Figure).

Based on regression analysis, age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis were not significantly associated with patients’ responses (eTable). The number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis (P=.034) and history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug (P=.018) were significantly associated with the willingness of patients presented with an anecdote to take a biologic medication.

Comment

Anecdotal Reassurance

The presentation of clinical trial and/or anecdotal evidence had a strong effect on patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis. Human perception of a treatment is inherently subjective, and such perceptions can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence.1 Across the population we studied, presenting a brief anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience is a quick and efficient means—and as or more effective as giving details on efficacy and safety—to help patients decide to take a treatment for their psoriasis.

Anecdotal reassurance is powerful. Both health care providers and patients have a natural tendency to focus on anecdotal experiences rather than statistical reasoning when making treatment decisions.10-12 Although negative anecdotal experiences may make patients unwilling to take a medication (or may make them overly desirous of an inappropriate treatment), clinicians can harness this psychological phenomenon to both increase patient willingness to take potentially beneficial treatments or to deter them from engaging in activities that can be harmful to their health, such as tanning and smoking.

Psoriasis Duration and Willingness to Take a Biologic Medication

In general, patient demographics did not appear to have an association with reported willingness to take a biologic medication for psoriasis. However, the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis had an effect on willingness to take a biologic medication, with patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis showing a higher willingness to take a treatment after being presented with an anecdote than patients with a shorter personal history of psoriasis. We can only speculate on the reasons why. Patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis may have tried and failed more treatments and therefore have a distrust in the validity of clinical trial evidence. These patients may feel their psoriasis is different than that of other clinical trial participants and thus may be more willing to rely on the success stories of individual patients.

Prior participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug was associated with a lower willingness to choose treatment after being presented with anecdotal reassurance. This finding may be attributable to these patients understanding the subjective nature of anecdotes and preferring more objective information in the form of randomized clinical trials in making treatment decisions. Overall, the presentation of evidence about the efficacy and safety of biologic medications in the treatment of psoriasis has a greater impact on patient decision-making than patients’ age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis.

Limitations

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. With closed-ended questions, patients were not able to explain their responses. In addition, hypothetical informational statements of a biologic’s efficacy and safety may not always imitate clinical reality. However, we believe the study is valid in exploring the power of an anecdote in influencing patients’ willingness to take biologic medications for psoriasis. Furthermore, educational level and ethnicity were excluded from the ordinal regression analysis because the assumption of parallel lines was not met.

Ethics Behind an Anecdote

An important consideration is the ethical implications of sharing an anecdote to guide patients’ perceptions of treatment and behavior. Although clinicians rely heavily on the available data to determine the best course of treatment, providing patients with comprehensive information on all risks and benefits is rarely, if ever, feasible. Moreover, even objective clinical data will inevitably be subjectively interpreted by patients. For example, describing a medication side effect as occurring in 1 in 100 patients may discourage patients from pursuing treatment, whereas describing that risk as not occurring in 99 in 100 patients may encourage patients, despite these 2 choices being mathematically identical.13 Because the subjective interpretation of data is inevitable, presenting patients with subjective information in the form of an anecdote to help them overcome fears of starting treatment and achieve their desired clinical outcomes may be one of the appropriate approaches to present what is objectively the best option, particularly if the anecdote is representative of the expected treatment response. Clinicians can harness this understanding of human psychology to better educate patients about their treatment options while fulfilling their ethical duty to act in their patients’ best interest.

Conclusion

Using an anecdote to help patients overcome fears of starting a biologic medication may be appropriate if the anecdote is reasonably representative of an expected treatment outcome. Patients should have an accurate understanding of the common risks and benefits of a medication for purposes of shared decision-making.

Biologic medications are highly effective in treating moderate to severe psoriasis, yet many patients are apprehensive about taking a biologic medication for a variety of reasons, such as hearing negative information about the drug from friends or family, being nervous about injection, or seeing the drug or its side effects negatively portrayed in the media.1-3 Because biologic medications are costly, many patients may fear needing to discontinue use of the medication owing to lack of affordability, which may result in subsequent rebound of psoriasis. Because patients’ fear of a drug is inherently subjective, it can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence. By understanding what information increases patients’ confidence in their willingness to take a biologic medication, patients may be more willing to initiate use of the drug and improve treatment outcomes.

There are mixed findings about whether statistical evidence or an anecdote is more effective in persuasion.4-6 The specific context in which the persuasion takes place may be important in determining which method is superior. In most nonthreatening situations, people appear to be more easily persuaded by statistical evidence rather than an anecdote. However, in circumstances where emotional engagement is high, such as regarding one’s own health, an anecdote tends to be more persuasive compared to statistical evidence.7 The purpose of this study was to evaluate patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for the management of their psoriasis if presented with either clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or both.

Methods

Patient Inclusion Criteria

Following Wake Forest School of Medicine institutional review board approval, a prospective parallel-arm survey study was performed on eligible patients 18 years or older with a self-reported diagnosis of psoriasis. Patients were required to have a working knowledge of English and not have been previously prescribed a biologic medication for their psoriasis. If patients did not meet inclusion criteria after answering the survey eligibility screening questions, then they were unable to complete the remainder of the survey and were excluded from the analysis.

Survey Administration

A total of 222 patients were recruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online crowdsourcing platform. (Amazon Mechanical Turk is a validated tool in conducting research in psychology and other social sciences and is considered as diverse as and perhaps more representative than traditional samples.8,9) Patients received a fact sheet and were taken to the survey hosted on Qualtrics, a secure web-based survey software that supports data collection for research studies. Amazon Mechanical Turk requires some amount of compensation to patients; therefore, recruited patients were compensated $0.03.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were randomized using SPSS Statistics version 23.0 (IBM) in a 1:1 ratio to assess how willing they would be to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis if presented with one of the following: (1) a control that queried patients about their willingness to take treatment without having been informed on its efficacy or safety, (2) clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety, (3) an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience, or (4) both clinical trial evidence of the agent’s efficacy and safety and an anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience (Table 1). Demographic information including sex, age, ethnicity, and education level was collected, in addition to other baseline characteristics such as having friends or family with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis.

Outcome measures were recorded as patients’ responses regarding their willingness to take a biologic medication on a 10-point Likert scale (1=not willing; 10=completely willing). Scores were treated as ordinal data and evaluated using the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by the Dunn test. Descriptive statistics were tabulated on all variables. Baseline characteristics were analyzed using a 2-tailed, unpaired t test for continuous variables and the χ2 and Fisher exact tests for categorical variables. Ordinal linear regression analysis was performed to determine whether reported willingness to take a biologic medication was related to patients’ demographics, including age, sex, having family or friends with a history of psoriasis, history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug, and the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis. Answers on the ordinal scale were binarized. The data were analyzed with SPSS Statistics version 23.0.

Results

There were no statistically significant differences among the baseline characteristics of the 4 information assignment groups (Table 2). Patients in the control group not given either clinical trial evidence of a biologic medication’s efficacy and safety or anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience had the lowest reported willingness to take treatment (median, 4.0)(Figure).

Based on regression analysis, age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis were not significantly associated with patients’ responses (eTable). The number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis (P=.034) and history of participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug (P=.018) were significantly associated with the willingness of patients presented with an anecdote to take a biologic medication.

Comment

Anecdotal Reassurance

The presentation of clinical trial and/or anecdotal evidence had a strong effect on patients’ willingness to take a biologic medication for their psoriasis. Human perception of a treatment is inherently subjective, and such perceptions can be modified with appropriate reassurance and presentation of evidence.1 Across the population we studied, presenting a brief anecdote of a single patient’s positive experience is a quick and efficient means—and as or more effective as giving details on efficacy and safety—to help patients decide to take a treatment for their psoriasis.

Anecdotal reassurance is powerful. Both health care providers and patients have a natural tendency to focus on anecdotal experiences rather than statistical reasoning when making treatment decisions.10-12 Although negative anecdotal experiences may make patients unwilling to take a medication (or may make them overly desirous of an inappropriate treatment), clinicians can harness this psychological phenomenon to both increase patient willingness to take potentially beneficial treatments or to deter them from engaging in activities that can be harmful to their health, such as tanning and smoking.

Psoriasis Duration and Willingness to Take a Biologic Medication

In general, patient demographics did not appear to have an association with reported willingness to take a biologic medication for psoriasis. However, the number of years since clinical diagnosis of psoriasis had an effect on willingness to take a biologic medication, with patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis showing a higher willingness to take a treatment after being presented with an anecdote than patients with a shorter personal history of psoriasis. We can only speculate on the reasons why. Patients with a longer personal history of psoriasis may have tried and failed more treatments and therefore have a distrust in the validity of clinical trial evidence. These patients may feel their psoriasis is different than that of other clinical trial participants and thus may be more willing to rely on the success stories of individual patients.

Prior participation in a clinical trial with use of an experimental drug was associated with a lower willingness to choose treatment after being presented with anecdotal reassurance. This finding may be attributable to these patients understanding the subjective nature of anecdotes and preferring more objective information in the form of randomized clinical trials in making treatment decisions. Overall, the presentation of evidence about the efficacy and safety of biologic medications in the treatment of psoriasis has a greater impact on patient decision-making than patients’ age, sex, and having friends or family with a history of psoriasis.

Limitations

Limitations of the study were typical of survey-based research. With closed-ended questions, patients were not able to explain their responses. In addition, hypothetical informational statements of a biologic’s efficacy and safety may not always imitate clinical reality. However, we believe the study is valid in exploring the power of an anecdote in influencing patients’ willingness to take biologic medications for psoriasis. Furthermore, educational level and ethnicity were excluded from the ordinal regression analysis because the assumption of parallel lines was not met.

Ethics Behind an Anecdote

An important consideration is the ethical implications of sharing an anecdote to guide patients’ perceptions of treatment and behavior. Although clinicians rely heavily on the available data to determine the best course of treatment, providing patients with comprehensive information on all risks and benefits is rarely, if ever, feasible. Moreover, even objective clinical data will inevitably be subjectively interpreted by patients. For example, describing a medication side effect as occurring in 1 in 100 patients may discourage patients from pursuing treatment, whereas describing that risk as not occurring in 99 in 100 patients may encourage patients, despite these 2 choices being mathematically identical.13 Because the subjective interpretation of data is inevitable, presenting patients with subjective information in the form of an anecdote to help them overcome fears of starting treatment and achieve their desired clinical outcomes may be one of the appropriate approaches to present what is objectively the best option, particularly if the anecdote is representative of the expected treatment response. Clinicians can harness this understanding of human psychology to better educate patients about their treatment options while fulfilling their ethical duty to act in their patients’ best interest.

Conclusion

Using an anecdote to help patients overcome fears of starting a biologic medication may be appropriate if the anecdote is reasonably representative of an expected treatment outcome. Patients should have an accurate understanding of the common risks and benefits of a medication for purposes of shared decision-making.

- Oussedik E, Cardwell LA, Patel NU, et al. An anchoring-based intervention to increase patient willingness to use injectable medication in psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:932-934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1271

- Brown KK, Rehmus WE, Kimball AB. Determining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:607-613. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.021

- Im H, Huh J. Does health information in mass media help or hurt patients? Investigation of potential negative influence of mass media health information on patients’ beliefs and medication regimen adherence. J Health Commun. 2017;22:214-222. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1261970

- Hornikx J. A review of experimental research on the relative persuasiveness of anecdotal, statistical, causal, and expert evidence. Studies Commun Sci. 2005;5:205-216.

- Allen M, Preiss RW. Comparing the persuasiveness of narrative and statistical evidence using meta-analysis. Int J Phytoremediation Commun Res Rep. 1997;14:125-131. doi:10.1080/08824099709388654

- Shen F, Sheer VC, Li R. Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: a meta-analysis. J Advert. 2015;44:105-113. doi:10.1080/00913367.2015.1018467

- Freling TH, Yang Z, Saini R, et al. When poignant stories outweigh cold hard facts: a meta-analysis of the anecdotal bias. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2020;160:51-67. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.01.006

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:3-5. doi:10.1177/1745691610393980

- Berry K, Butt M, Kirby JS. Influence of information framing on patient decisions to treat actinic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:421-426. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5245

- Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Reed M, et al. Personal, organizational, and market level influences on physicians’ practice patterns: results of a national survey of primary care physicians. Med Care. 2001;39:889-905. doi:10.1097/00005650-200108000-00014

- Borgida E, Nisbett RE. The differential impact of abstract vs. concrete information on decisions. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1977;7:258-271. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1977.tb00750.x

- Fagerlin A, Wang C, Ubel PA. Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people’s health care decisions: is a picture worth a thousand statistics? Med Decis Making. 2005;25:398-405. doi:10.1177/0272989X05278931

- Gurm HS, Litaker DG. Framing procedural risks to patients: Is 99% safe the same as a risk of 1 in 100? Acad Med. 2000;75:840-842. doi:10.1097/00001888-200008000-00018

- Oussedik E, Cardwell LA, Patel NU, et al. An anchoring-based intervention to increase patient willingness to use injectable medication in psoriasis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:932-934. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1271

- Brown KK, Rehmus WE, Kimball AB. Determining the relative importance of patient motivations for nonadherence to topical corticosteroid therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:607-613. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2005.12.021

- Im H, Huh J. Does health information in mass media help or hurt patients? Investigation of potential negative influence of mass media health information on patients’ beliefs and medication regimen adherence. J Health Commun. 2017;22:214-222. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1261970

- Hornikx J. A review of experimental research on the relative persuasiveness of anecdotal, statistical, causal, and expert evidence. Studies Commun Sci. 2005;5:205-216.

- Allen M, Preiss RW. Comparing the persuasiveness of narrative and statistical evidence using meta-analysis. Int J Phytoremediation Commun Res Rep. 1997;14:125-131. doi:10.1080/08824099709388654

- Shen F, Sheer VC, Li R. Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: a meta-analysis. J Advert. 2015;44:105-113. doi:10.1080/00913367.2015.1018467

- Freling TH, Yang Z, Saini R, et al. When poignant stories outweigh cold hard facts: a meta-analysis of the anecdotal bias. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2020;160:51-67. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2020.01.006

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:3-5. doi:10.1177/1745691610393980

- Berry K, Butt M, Kirby JS. Influence of information framing on patient decisions to treat actinic keratosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:421-426. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.5245

- Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Reed M, et al. Personal, organizational, and market level influences on physicians’ practice patterns: results of a national survey of primary care physicians. Med Care. 2001;39:889-905. doi:10.1097/00005650-200108000-00014

- Borgida E, Nisbett RE. The differential impact of abstract vs. concrete information on decisions. J Appl Soc Psychol. 1977;7:258-271. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1977.tb00750.x

- Fagerlin A, Wang C, Ubel PA. Reducing the influence of anecdotal reasoning on people’s health care decisions: is a picture worth a thousand statistics? Med Decis Making. 2005;25:398-405. doi:10.1177/0272989X05278931

- Gurm HS, Litaker DG. Framing procedural risks to patients: Is 99% safe the same as a risk of 1 in 100? Acad Med. 2000;75:840-842. doi:10.1097/00001888-200008000-00018

Practice Points

- Patients often are apprehensive to start biologic medications for their psoriasis.

- Clinical trial evidence of a biologic medication’s efficacy and safety as well as anecdotes of patient experiences appear to be important factors for patients when considering taking a medication.

- The use of an anecdote—alone or in combination with clinical trial evidence—to help patients overcome fears of starting a biologic medication for their psoriasis may be an effective way to improve patients’ willingness to take treatment.