User login

Modifiable Factors Associated with Quality of Bowel Preparation Among Hospitalized Patients Undergoing Colonoscopy

Inadequate bowel preparation (IBP) at the time of inpatient colonoscopy is common and associated with increased length of stay and cost of care.1 The factors that contribute to IBP can be categorized into those that are modifiable and those that are nonmodifiable. While many factors have been associated with IBP, studies have been limited by small sample size or have combined inpatient/outpatient populations, thus limiting generalizability.1-5 Moreover, most factors associated with IBP, such as socioeconomic status, male gender, increased age, and comorbidities, are nonmodifiable. No studies have explicitly focused on modifiable risk factors, such as medication use, colonoscopy timing, or assessed the potential impact of modifying these factors.

In a large, multihospital system, we examine the frequency of IBP among inpatients undergoing colonoscopy along with factors associated with IBP. We attempted to identify

METHODS

Potential Predictors of IBP

Demographic data such as patient age, gender, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), and insurance/payor status were obtained from the electronic health record (EHR). International Classification of Disease 9th and 10th revision, Clinical Modifications (ICD-9/10-CM) codes were used to obtain patient comorbidities including diabetes, coronary artery disease, heart failure, cirrhosis, gastroparesis, hypothyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, constipation, stroke, dementia, dysphagia, and nausea/vomiting. Use of opioid medications within three days before colonoscopy was extracted from the medication administration record. These variables were chosen as biologically plausible modifiers of bowel preparation or had previously been assessed in the literature.1-6 The name and volume, classified as 4 L (GoLytely®) and < 4 liters (MoviPrep®) of bowel preparation, time of day when colonoscopy was performed, solid diet the day prior to colonoscopy, type of sedation used (conscious sedation or general anesthesia), and total colonoscopy time (defined as the time from scope insertion to removal) was recorded. Hospitalization-related variables, including the number of hospitalizations in the year before the current hospitalization, the year in which the colonoscopy was performed, and the number of days from admission to colonoscopy, were also obtained from the EHR.

Outcome Measures

An internally validated natural language algorithm, using Structured Queried Language was used to search through colonoscopy reports to identify adequacy of bowel preparation. ProVation® software allows the gastroenterologist to use some terms to describe bowel preparation in a drop-down menu format. In addition to the Aronchik scale (which allows the gastroenterologist to rate bowel preparation on a five-point scale: “excellent,” “good,” “fair,” “poor,” and “inadequate”) it also allows the provider to use terms such as “adequate” or “adequate to detect polyps >5 mm” as well as “unsatisfactory.”7 Mirroring prior literature, bowel preparation quality was classified into “adequate” and “inadequate”; “good” and “excellent” on the Aronchik scale were categorized as adequate as was the term “adequate” in any form; “fair,” “poor,” or “inadequate” on the Aronchik scale were classified as inadequate as was the term “unsatisfactory.” We evaluated the hospital length of stay (LOS) as a secondary outcome measure.

Statistical Analysis

After describing the frequency of IBP, the quality of bowel preparation (adequate vs inadequate) was compared based on the predictors described above. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies with percentages and continuous variables were reported as medians with 25th-75th percentile values. The significance of the difference between the proportion or median values of those who had inadequate versus adequate bowel preparation was assessed. Two-sided chi-square analysis was used to assess the significance of differences between categorical variables and the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test was used to assess the significance of differences between continuous variables.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess factors associated with hospital predictors and outcomes, after adjusting for all the aforementioned factors and clustering the effect based on the endoscopist. To evaluate the potential impact of modifiable factors on IBP, we performed counterfactual analysis, in which the observed distribution was compared to a hypothetical population in which all the modifiable risk factors were optimal.

RESULTS

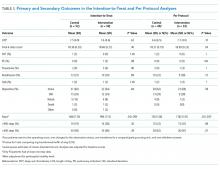

Overall, 8,819 patients were included in our study population. They had a median age of 64 [53-76] years; 50.5% were female and 51% had an IBP. Patient characteristics and rates of IBP are presented in Table 1.

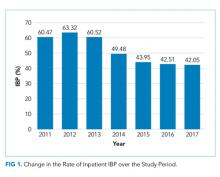

In unadjusted analyses, with regards to modifiable factors, opiate use within three days of colonoscopy was associated with a higher rate of IBP (55.4% vs 47.3%, P <.001), as was a lower volume (<4L) bowel preparation (55.3% vs 50.4%, P = .003). IBP was less frequent when colonoscopy was performed before noon vs afternoon (50.3% vs 57.4%, P < .001), and when patients were documented to receive a clear liquid diet or nil per os vs a solid diet the day prior to colonoscopy (50.3% vs 57.4%, P < .001). Overall bowel preparation quality improved over time (Figure 1). Median LOS was five [3-11] days. Patients who had IBP on their initial colonoscopy had a LOS one day longer than patients without IBP (six days vs five days, P < .001).

Multivariate Analysis

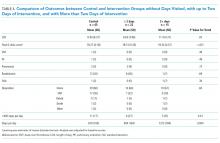

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariate analysis. The following modifiable factors were associated with IBP: opiate used within three days of the procedure (OR 1.31; 95% CI 1.8, 1.45), having the colonoscopy performed after12:00

Potential Impact of Modifiable Variables

We conducted a counterfactual analysis based on a multivariate model to assess the impact of each modifiable risk factor on the IBP rate (Figure 1). In the included study population, 44.9% received an opiate, 39.3% had a colonoscopy after 12:00

DISCUSSION

In this large, multihospital cohort, IBP was documented in half (51%) of 8,819 inpatient colonoscopies performed. Nonmodifiable patient characteristics independently associated with IBP were age, male gender, white race, Medicare and Medicaid insurance, nausea/vomiting, dysphagia, and gastroparesis. Modifiable factors included not consuming opiates within three days of colonoscopy, avoidance of a solid diet the day prior to colonoscopy and performing the colonoscopy before noon. The volume of bowel preparation consumed was not associated with IBP. In a counterfactual analysis, we found that if all three modifiable factors were optimized, the predicted rate of IBP would drop to 45%.

Many studies, including our analysis, have shown significant differences between the frequency of IBP in inpatient versus outpatient bowel preparations.8-11 Therefore, it is crucial to study IBP in these settings separately. Three single-institution studies, including a total of 898 patients, have identified risk factors for inpatient IBP. Individual studies ranged in size from 130 to 524 patients with rates of IBP ranging from 22%-57%.1-3 They found IBP to be associated with increasing age, lower income, ASA Grade >3, diabetes, coronary artery disease (CAD), nausea or vomiting, BMI >25, and chronic constipation. Modifiable factors included opiates, afternoon procedures, and runway times >6 hours.

We also found IBP to be associated with increasing age and male gender. However, we found no association with diabetes, chronic constipation, CAD or BMI. As we were able to adjust for a wider variety of variables, it is possible that we were able to account for residual confounding better than previous studies. For example, we found that having nausea/vomiting, dysphagia, and gastroparesis was associated with IBP. Gastroparesis with associated nausea and vomiting may be the mechanism by which diabetes increases the risk for IBP. Further studies are needed to assess if interventions or alternative bowel cleansing in these patients can result in improved IBP. Finally, in contrast to studies with smaller cohorts which found that lower volume bowel preps improved IBP in the right colon,4,12 we found no association between IBP based and volume of bowel preparation consumed. Our impact analysis suggests that avoidance of opiates for at least three days before colonoscopy, avoidance of solid diet on the day before colonoscopy and performing all colonoscopies before noon would

The factors mentioned above may not always be amenable to modification. For example, for patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding, postponing colonoscopy by one day for the sake of maintaining a patient on a clear diet may not be feasible. Similarly, performing colonoscopies in the morning is highly dependent on endoscopy suite availability and hospital logistics. Denying opiates to patients experiencing severe pain is not ethical. In many scenarios, however, these variables could be modified, and institutional efforts to support these practices could yield considerable savings. Future prospective studies are needed to verify the real impact of these changes.

Further discussion is needed to contextualize the finding that colonoscopies scheduled in the afternoon are associated with improved bowel preparation quality. Previous research—albeit in the outpatient setting—has demonstrated 11.8 hours as the maximum upper time limit for the time elapsed between the end of bowel preparation to colonoscopy.14 Another study found an inverse relationship between the quality of bowel preparation and the time after completion of the bowel preparation.15 This makes sense from a physiological perspective as delaying the time between completion of bowel preparation, and the procedure allows chyme from the small intestine to reaccumulate in the colon. Anecdotally, at our institution as well as at many others, the bowel preparations are ordered to start in the evening to allow the consumption of complete bowel preparation by midnight. As a result of this practice, only patients who have their colonoscopies scheduled before noon fall within the optimal period of 11.8 hours. In the outpatient setting, the use of split preparations has led to the obliteration of the difference in the quality of bowel preparation between morning and afternoon colonoscopies.16 Prospective trials are needed to evaluate the use of split preparations to improve the quality of afternoon inpatient colonoscopies.

Few other strategies have been shown to mitigate IBP in the inpatient setting. In a small randomized controlled trial, Ergen et al. found that providing an educational booklet improved inpatient bowel preparation as measured by the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale.17 In a quasi-experimental design, Yadlapati et al. found that an automated split-dose bowel preparation resulted in decreased IBP, fewer repeated procedures, shorter LOS, and lower hospital cost.18 Our study adds to these tools by identifying three additional risk factors which could be optimized for inpatients. Because our findings are observational, they should be subjected to prospective trials. Our study also calls into question the impact of bowel preparation volume. We found no difference in the rate of IBP between low and large volume preparations. It is possible that other factors are more important than the specific preparation employed.

Interestingly, we found that IBP declined substantially in 2014 and continued to decline after that. The year was the most influential risk factor for IBP (on par with gastroparesis). The reason for this is unclear, as rates of our modifiable risk factors did not differ substantially by year. Other possibilities include improved access (including weekend access) to endoscopy coinciding with the development of a new endoscopy facility and use of integrated irrigation pump system instead of the use of manual syringes for flushing.

Our study has many strengths. It is by far the most extensive study of bowel preparation quality in inpatients to date and the only one that has included patient, procedural and bowel preparation characteristics. The study also has several significant limitations. This is a single center study, which could limit generalizability. Nonetheless, it was conducted within a health system with multiple hospitals in different parts of the United States (Ohio and Florida) and included a broad population mix with differing levels of acuity. The retrospective nature of the assessment precludes establishing causation. However, we mitigated confounding by adjusting for a wide variety of factors, and there is a plausible physiological mechanism for each of the factors we studied. Also, the retrospective nature of our study predisposes our data to omissions and misrepresentations during the documentation process. This is especially true with the use of ICD codes.19 Inaccuracies in coding are likely to bias toward the null, so observed associations may be an underestimate of the true association.

Our inability to ascertain if a patient completed the prescribed bowel preparation limited our ability to detect what may be a significant risk factor. Lastly, while clinically relevant, the Aronchik scale used to identify adequate from IBP has never been validated though it is frequently utilized and cited in the bowel preparation literature.20

CONCLUSIONS

In this large retrospective study evaluating bowel preparation quality in inpatients undergoing colonoscopy, we found that more than half of the patients have IBP and that IBP was associated with an extra day of hospitalization. Our study identifies those patients at highest risk and identifies modifiable risk factors for IBP. Specifically, we found that abstinence from opiates or solid diet before the colonoscopy, along with performing colonoscopies before noon were associated with improved outcomes. Prospective studies are needed to confirm the effects of these interventions on bowel preparation quality.

Disclosures

Carol A Burke, MD has received research funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Yadlapati R, Johnston ER, Gregory DL, Ciolino JD, Cooper A, Keswani RN. Predictors of inadequate inpatient colonoscopy preparation and its association with hospital length of stay and costs. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(11):3482-3490. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3761-2. PubMed

2. Jawa H, Mosli M, Alsamadani W, et al. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for inpatient colonoscopy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28(6):460-464. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2017.17196. PubMed

3. Mcnabb-Baltar J, Dorreen A, Dhahab HA, et al. Age is the only predictor of poor bowel preparation in the hospitalized patient. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:1-5. doi: 10.1155/2016/2139264. PubMed

4. Rotondano G, Rispo A, Bottiglieri ME, et al. Tu1503 Quality of bowel cleansing in hospitalized patients is not worse than that of outpatients undergoing colonoscopy: results of a multicenter prospective regional study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(5):AB564. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.02.949. PubMed

5. Ness R. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(6):1797-1802. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(01)02437-6. PubMed

6. Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the us multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(4):903-924. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.002. PubMed

7. Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, et al. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52(3):346-352. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108480. PubMed

8. Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers J-J, Burnand B, Vader J-P. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(3):378-384. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2. PubMed

9. Sarvepalli S, Garber A, Rizk M, et al. 923 adjusted comparison of commercial bowel preparations based on inadequacy of bowel preparation in outpatient settings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87(6):AB127. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.04.1331.

10. Hendry PO, Jenkins JT, Diament RH. The impact of poor bowel preparation on colonoscopy: a prospective single center study of 10 571 colonoscopies. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(8):745-748. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01220.x. PubMed

11. Lebwohl B, Wang TC, Neugut AI. Socioeconomic and other predictors of colonoscopy preparation quality. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(7):2014-2020. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1079-7. PubMed

12. Chorev N, Chadad B, Segal N, et al. Preparation for colonoscopy in hospitalized patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(3):835-839. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9591-5. PubMed

13. Weiss AJ. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #180. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. PubMed

14. Kojecky V, Matous J, Keil R, et al. The optimal bowel preparation intervals before colonoscopy: a randomized study comparing polyethylene glycol and low-volume solutions. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50(3):271-276. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.10.010. PubMed

15. Siddiqui AA, Yang K, Spechler SJ, et al. Duration of the interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy predicts bowel-preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3):700-706. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.047. PubMed

16. Eun CS, Han DS, Hyun YS, et al. The timing of bowel preparation is more important than the timing of colonoscopy in determining the quality of bowel cleansing. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;56(2):539-544. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1457-1. PubMed

17. Ergen WF, Pasricha T, Hubbard FJ, et al. Providing hospitalized patients with an educational booklet increases the quality of colonoscopy bowel preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(6):858-864. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.015. PubMed

18. Yadlapati R, Johnston ER, Gluskin AB, et al. An automated inpatient split-dose bowel preparation system improves colonoscopy quality and reduces repeat procedures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(8):709-714. doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000849. PubMed

19. Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, Nilasena DS, Radford MJ, Gage BF. The accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med Care. 2005;43(5):480-485. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160417.39497.a9. PubMed

20. Parmar R, Martel M, Rostom A, Barkun AN. Validated scales for colon cleansing: a systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;111(2):197-204. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.417. PubMed

Inadequate bowel preparation (IBP) at the time of inpatient colonoscopy is common and associated with increased length of stay and cost of care.1 The factors that contribute to IBP can be categorized into those that are modifiable and those that are nonmodifiable. While many factors have been associated with IBP, studies have been limited by small sample size or have combined inpatient/outpatient populations, thus limiting generalizability.1-5 Moreover, most factors associated with IBP, such as socioeconomic status, male gender, increased age, and comorbidities, are nonmodifiable. No studies have explicitly focused on modifiable risk factors, such as medication use, colonoscopy timing, or assessed the potential impact of modifying these factors.

In a large, multihospital system, we examine the frequency of IBP among inpatients undergoing colonoscopy along with factors associated with IBP. We attempted to identify

METHODS

Potential Predictors of IBP

Demographic data such as patient age, gender, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), and insurance/payor status were obtained from the electronic health record (EHR). International Classification of Disease 9th and 10th revision, Clinical Modifications (ICD-9/10-CM) codes were used to obtain patient comorbidities including diabetes, coronary artery disease, heart failure, cirrhosis, gastroparesis, hypothyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, constipation, stroke, dementia, dysphagia, and nausea/vomiting. Use of opioid medications within three days before colonoscopy was extracted from the medication administration record. These variables were chosen as biologically plausible modifiers of bowel preparation or had previously been assessed in the literature.1-6 The name and volume, classified as 4 L (GoLytely®) and < 4 liters (MoviPrep®) of bowel preparation, time of day when colonoscopy was performed, solid diet the day prior to colonoscopy, type of sedation used (conscious sedation or general anesthesia), and total colonoscopy time (defined as the time from scope insertion to removal) was recorded. Hospitalization-related variables, including the number of hospitalizations in the year before the current hospitalization, the year in which the colonoscopy was performed, and the number of days from admission to colonoscopy, were also obtained from the EHR.

Outcome Measures

An internally validated natural language algorithm, using Structured Queried Language was used to search through colonoscopy reports to identify adequacy of bowel preparation. ProVation® software allows the gastroenterologist to use some terms to describe bowel preparation in a drop-down menu format. In addition to the Aronchik scale (which allows the gastroenterologist to rate bowel preparation on a five-point scale: “excellent,” “good,” “fair,” “poor,” and “inadequate”) it also allows the provider to use terms such as “adequate” or “adequate to detect polyps >5 mm” as well as “unsatisfactory.”7 Mirroring prior literature, bowel preparation quality was classified into “adequate” and “inadequate”; “good” and “excellent” on the Aronchik scale were categorized as adequate as was the term “adequate” in any form; “fair,” “poor,” or “inadequate” on the Aronchik scale were classified as inadequate as was the term “unsatisfactory.” We evaluated the hospital length of stay (LOS) as a secondary outcome measure.

Statistical Analysis

After describing the frequency of IBP, the quality of bowel preparation (adequate vs inadequate) was compared based on the predictors described above. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies with percentages and continuous variables were reported as medians with 25th-75th percentile values. The significance of the difference between the proportion or median values of those who had inadequate versus adequate bowel preparation was assessed. Two-sided chi-square analysis was used to assess the significance of differences between categorical variables and the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test was used to assess the significance of differences between continuous variables.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess factors associated with hospital predictors and outcomes, after adjusting for all the aforementioned factors and clustering the effect based on the endoscopist. To evaluate the potential impact of modifiable factors on IBP, we performed counterfactual analysis, in which the observed distribution was compared to a hypothetical population in which all the modifiable risk factors were optimal.

RESULTS

Overall, 8,819 patients were included in our study population. They had a median age of 64 [53-76] years; 50.5% were female and 51% had an IBP. Patient characteristics and rates of IBP are presented in Table 1.

In unadjusted analyses, with regards to modifiable factors, opiate use within three days of colonoscopy was associated with a higher rate of IBP (55.4% vs 47.3%, P <.001), as was a lower volume (<4L) bowel preparation (55.3% vs 50.4%, P = .003). IBP was less frequent when colonoscopy was performed before noon vs afternoon (50.3% vs 57.4%, P < .001), and when patients were documented to receive a clear liquid diet or nil per os vs a solid diet the day prior to colonoscopy (50.3% vs 57.4%, P < .001). Overall bowel preparation quality improved over time (Figure 1). Median LOS was five [3-11] days. Patients who had IBP on their initial colonoscopy had a LOS one day longer than patients without IBP (six days vs five days, P < .001).

Multivariate Analysis

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariate analysis. The following modifiable factors were associated with IBP: opiate used within three days of the procedure (OR 1.31; 95% CI 1.8, 1.45), having the colonoscopy performed after12:00

Potential Impact of Modifiable Variables

We conducted a counterfactual analysis based on a multivariate model to assess the impact of each modifiable risk factor on the IBP rate (Figure 1). In the included study population, 44.9% received an opiate, 39.3% had a colonoscopy after 12:00

DISCUSSION

In this large, multihospital cohort, IBP was documented in half (51%) of 8,819 inpatient colonoscopies performed. Nonmodifiable patient characteristics independently associated with IBP were age, male gender, white race, Medicare and Medicaid insurance, nausea/vomiting, dysphagia, and gastroparesis. Modifiable factors included not consuming opiates within three days of colonoscopy, avoidance of a solid diet the day prior to colonoscopy and performing the colonoscopy before noon. The volume of bowel preparation consumed was not associated with IBP. In a counterfactual analysis, we found that if all three modifiable factors were optimized, the predicted rate of IBP would drop to 45%.

Many studies, including our analysis, have shown significant differences between the frequency of IBP in inpatient versus outpatient bowel preparations.8-11 Therefore, it is crucial to study IBP in these settings separately. Three single-institution studies, including a total of 898 patients, have identified risk factors for inpatient IBP. Individual studies ranged in size from 130 to 524 patients with rates of IBP ranging from 22%-57%.1-3 They found IBP to be associated with increasing age, lower income, ASA Grade >3, diabetes, coronary artery disease (CAD), nausea or vomiting, BMI >25, and chronic constipation. Modifiable factors included opiates, afternoon procedures, and runway times >6 hours.

We also found IBP to be associated with increasing age and male gender. However, we found no association with diabetes, chronic constipation, CAD or BMI. As we were able to adjust for a wider variety of variables, it is possible that we were able to account for residual confounding better than previous studies. For example, we found that having nausea/vomiting, dysphagia, and gastroparesis was associated with IBP. Gastroparesis with associated nausea and vomiting may be the mechanism by which diabetes increases the risk for IBP. Further studies are needed to assess if interventions or alternative bowel cleansing in these patients can result in improved IBP. Finally, in contrast to studies with smaller cohorts which found that lower volume bowel preps improved IBP in the right colon,4,12 we found no association between IBP based and volume of bowel preparation consumed. Our impact analysis suggests that avoidance of opiates for at least three days before colonoscopy, avoidance of solid diet on the day before colonoscopy and performing all colonoscopies before noon would

The factors mentioned above may not always be amenable to modification. For example, for patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding, postponing colonoscopy by one day for the sake of maintaining a patient on a clear diet may not be feasible. Similarly, performing colonoscopies in the morning is highly dependent on endoscopy suite availability and hospital logistics. Denying opiates to patients experiencing severe pain is not ethical. In many scenarios, however, these variables could be modified, and institutional efforts to support these practices could yield considerable savings. Future prospective studies are needed to verify the real impact of these changes.

Further discussion is needed to contextualize the finding that colonoscopies scheduled in the afternoon are associated with improved bowel preparation quality. Previous research—albeit in the outpatient setting—has demonstrated 11.8 hours as the maximum upper time limit for the time elapsed between the end of bowel preparation to colonoscopy.14 Another study found an inverse relationship between the quality of bowel preparation and the time after completion of the bowel preparation.15 This makes sense from a physiological perspective as delaying the time between completion of bowel preparation, and the procedure allows chyme from the small intestine to reaccumulate in the colon. Anecdotally, at our institution as well as at many others, the bowel preparations are ordered to start in the evening to allow the consumption of complete bowel preparation by midnight. As a result of this practice, only patients who have their colonoscopies scheduled before noon fall within the optimal period of 11.8 hours. In the outpatient setting, the use of split preparations has led to the obliteration of the difference in the quality of bowel preparation between morning and afternoon colonoscopies.16 Prospective trials are needed to evaluate the use of split preparations to improve the quality of afternoon inpatient colonoscopies.

Few other strategies have been shown to mitigate IBP in the inpatient setting. In a small randomized controlled trial, Ergen et al. found that providing an educational booklet improved inpatient bowel preparation as measured by the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale.17 In a quasi-experimental design, Yadlapati et al. found that an automated split-dose bowel preparation resulted in decreased IBP, fewer repeated procedures, shorter LOS, and lower hospital cost.18 Our study adds to these tools by identifying three additional risk factors which could be optimized for inpatients. Because our findings are observational, they should be subjected to prospective trials. Our study also calls into question the impact of bowel preparation volume. We found no difference in the rate of IBP between low and large volume preparations. It is possible that other factors are more important than the specific preparation employed.

Interestingly, we found that IBP declined substantially in 2014 and continued to decline after that. The year was the most influential risk factor for IBP (on par with gastroparesis). The reason for this is unclear, as rates of our modifiable risk factors did not differ substantially by year. Other possibilities include improved access (including weekend access) to endoscopy coinciding with the development of a new endoscopy facility and use of integrated irrigation pump system instead of the use of manual syringes for flushing.

Our study has many strengths. It is by far the most extensive study of bowel preparation quality in inpatients to date and the only one that has included patient, procedural and bowel preparation characteristics. The study also has several significant limitations. This is a single center study, which could limit generalizability. Nonetheless, it was conducted within a health system with multiple hospitals in different parts of the United States (Ohio and Florida) and included a broad population mix with differing levels of acuity. The retrospective nature of the assessment precludes establishing causation. However, we mitigated confounding by adjusting for a wide variety of factors, and there is a plausible physiological mechanism for each of the factors we studied. Also, the retrospective nature of our study predisposes our data to omissions and misrepresentations during the documentation process. This is especially true with the use of ICD codes.19 Inaccuracies in coding are likely to bias toward the null, so observed associations may be an underestimate of the true association.

Our inability to ascertain if a patient completed the prescribed bowel preparation limited our ability to detect what may be a significant risk factor. Lastly, while clinically relevant, the Aronchik scale used to identify adequate from IBP has never been validated though it is frequently utilized and cited in the bowel preparation literature.20

CONCLUSIONS

In this large retrospective study evaluating bowel preparation quality in inpatients undergoing colonoscopy, we found that more than half of the patients have IBP and that IBP was associated with an extra day of hospitalization. Our study identifies those patients at highest risk and identifies modifiable risk factors for IBP. Specifically, we found that abstinence from opiates or solid diet before the colonoscopy, along with performing colonoscopies before noon were associated with improved outcomes. Prospective studies are needed to confirm the effects of these interventions on bowel preparation quality.

Disclosures

Carol A Burke, MD has received research funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Inadequate bowel preparation (IBP) at the time of inpatient colonoscopy is common and associated with increased length of stay and cost of care.1 The factors that contribute to IBP can be categorized into those that are modifiable and those that are nonmodifiable. While many factors have been associated with IBP, studies have been limited by small sample size or have combined inpatient/outpatient populations, thus limiting generalizability.1-5 Moreover, most factors associated with IBP, such as socioeconomic status, male gender, increased age, and comorbidities, are nonmodifiable. No studies have explicitly focused on modifiable risk factors, such as medication use, colonoscopy timing, or assessed the potential impact of modifying these factors.

In a large, multihospital system, we examine the frequency of IBP among inpatients undergoing colonoscopy along with factors associated with IBP. We attempted to identify

METHODS

Potential Predictors of IBP

Demographic data such as patient age, gender, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), and insurance/payor status were obtained from the electronic health record (EHR). International Classification of Disease 9th and 10th revision, Clinical Modifications (ICD-9/10-CM) codes were used to obtain patient comorbidities including diabetes, coronary artery disease, heart failure, cirrhosis, gastroparesis, hypothyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, constipation, stroke, dementia, dysphagia, and nausea/vomiting. Use of opioid medications within three days before colonoscopy was extracted from the medication administration record. These variables were chosen as biologically plausible modifiers of bowel preparation or had previously been assessed in the literature.1-6 The name and volume, classified as 4 L (GoLytely®) and < 4 liters (MoviPrep®) of bowel preparation, time of day when colonoscopy was performed, solid diet the day prior to colonoscopy, type of sedation used (conscious sedation or general anesthesia), and total colonoscopy time (defined as the time from scope insertion to removal) was recorded. Hospitalization-related variables, including the number of hospitalizations in the year before the current hospitalization, the year in which the colonoscopy was performed, and the number of days from admission to colonoscopy, were also obtained from the EHR.

Outcome Measures

An internally validated natural language algorithm, using Structured Queried Language was used to search through colonoscopy reports to identify adequacy of bowel preparation. ProVation® software allows the gastroenterologist to use some terms to describe bowel preparation in a drop-down menu format. In addition to the Aronchik scale (which allows the gastroenterologist to rate bowel preparation on a five-point scale: “excellent,” “good,” “fair,” “poor,” and “inadequate”) it also allows the provider to use terms such as “adequate” or “adequate to detect polyps >5 mm” as well as “unsatisfactory.”7 Mirroring prior literature, bowel preparation quality was classified into “adequate” and “inadequate”; “good” and “excellent” on the Aronchik scale were categorized as adequate as was the term “adequate” in any form; “fair,” “poor,” or “inadequate” on the Aronchik scale were classified as inadequate as was the term “unsatisfactory.” We evaluated the hospital length of stay (LOS) as a secondary outcome measure.

Statistical Analysis

After describing the frequency of IBP, the quality of bowel preparation (adequate vs inadequate) was compared based on the predictors described above. Categorical variables were reported as frequencies with percentages and continuous variables were reported as medians with 25th-75th percentile values. The significance of the difference between the proportion or median values of those who had inadequate versus adequate bowel preparation was assessed. Two-sided chi-square analysis was used to assess the significance of differences between categorical variables and the Wilcoxon Rank-Sum test was used to assess the significance of differences between continuous variables.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess factors associated with hospital predictors and outcomes, after adjusting for all the aforementioned factors and clustering the effect based on the endoscopist. To evaluate the potential impact of modifiable factors on IBP, we performed counterfactual analysis, in which the observed distribution was compared to a hypothetical population in which all the modifiable risk factors were optimal.

RESULTS

Overall, 8,819 patients were included in our study population. They had a median age of 64 [53-76] years; 50.5% were female and 51% had an IBP. Patient characteristics and rates of IBP are presented in Table 1.

In unadjusted analyses, with regards to modifiable factors, opiate use within three days of colonoscopy was associated with a higher rate of IBP (55.4% vs 47.3%, P <.001), as was a lower volume (<4L) bowel preparation (55.3% vs 50.4%, P = .003). IBP was less frequent when colonoscopy was performed before noon vs afternoon (50.3% vs 57.4%, P < .001), and when patients were documented to receive a clear liquid diet or nil per os vs a solid diet the day prior to colonoscopy (50.3% vs 57.4%, P < .001). Overall bowel preparation quality improved over time (Figure 1). Median LOS was five [3-11] days. Patients who had IBP on their initial colonoscopy had a LOS one day longer than patients without IBP (six days vs five days, P < .001).

Multivariate Analysis

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariate analysis. The following modifiable factors were associated with IBP: opiate used within three days of the procedure (OR 1.31; 95% CI 1.8, 1.45), having the colonoscopy performed after12:00

Potential Impact of Modifiable Variables

We conducted a counterfactual analysis based on a multivariate model to assess the impact of each modifiable risk factor on the IBP rate (Figure 1). In the included study population, 44.9% received an opiate, 39.3% had a colonoscopy after 12:00

DISCUSSION

In this large, multihospital cohort, IBP was documented in half (51%) of 8,819 inpatient colonoscopies performed. Nonmodifiable patient characteristics independently associated with IBP were age, male gender, white race, Medicare and Medicaid insurance, nausea/vomiting, dysphagia, and gastroparesis. Modifiable factors included not consuming opiates within three days of colonoscopy, avoidance of a solid diet the day prior to colonoscopy and performing the colonoscopy before noon. The volume of bowel preparation consumed was not associated with IBP. In a counterfactual analysis, we found that if all three modifiable factors were optimized, the predicted rate of IBP would drop to 45%.

Many studies, including our analysis, have shown significant differences between the frequency of IBP in inpatient versus outpatient bowel preparations.8-11 Therefore, it is crucial to study IBP in these settings separately. Three single-institution studies, including a total of 898 patients, have identified risk factors for inpatient IBP. Individual studies ranged in size from 130 to 524 patients with rates of IBP ranging from 22%-57%.1-3 They found IBP to be associated with increasing age, lower income, ASA Grade >3, diabetes, coronary artery disease (CAD), nausea or vomiting, BMI >25, and chronic constipation. Modifiable factors included opiates, afternoon procedures, and runway times >6 hours.

We also found IBP to be associated with increasing age and male gender. However, we found no association with diabetes, chronic constipation, CAD or BMI. As we were able to adjust for a wider variety of variables, it is possible that we were able to account for residual confounding better than previous studies. For example, we found that having nausea/vomiting, dysphagia, and gastroparesis was associated with IBP. Gastroparesis with associated nausea and vomiting may be the mechanism by which diabetes increases the risk for IBP. Further studies are needed to assess if interventions or alternative bowel cleansing in these patients can result in improved IBP. Finally, in contrast to studies with smaller cohorts which found that lower volume bowel preps improved IBP in the right colon,4,12 we found no association between IBP based and volume of bowel preparation consumed. Our impact analysis suggests that avoidance of opiates for at least three days before colonoscopy, avoidance of solid diet on the day before colonoscopy and performing all colonoscopies before noon would

The factors mentioned above may not always be amenable to modification. For example, for patients with active gastrointestinal bleeding, postponing colonoscopy by one day for the sake of maintaining a patient on a clear diet may not be feasible. Similarly, performing colonoscopies in the morning is highly dependent on endoscopy suite availability and hospital logistics. Denying opiates to patients experiencing severe pain is not ethical. In many scenarios, however, these variables could be modified, and institutional efforts to support these practices could yield considerable savings. Future prospective studies are needed to verify the real impact of these changes.

Further discussion is needed to contextualize the finding that colonoscopies scheduled in the afternoon are associated with improved bowel preparation quality. Previous research—albeit in the outpatient setting—has demonstrated 11.8 hours as the maximum upper time limit for the time elapsed between the end of bowel preparation to colonoscopy.14 Another study found an inverse relationship between the quality of bowel preparation and the time after completion of the bowel preparation.15 This makes sense from a physiological perspective as delaying the time between completion of bowel preparation, and the procedure allows chyme from the small intestine to reaccumulate in the colon. Anecdotally, at our institution as well as at many others, the bowel preparations are ordered to start in the evening to allow the consumption of complete bowel preparation by midnight. As a result of this practice, only patients who have their colonoscopies scheduled before noon fall within the optimal period of 11.8 hours. In the outpatient setting, the use of split preparations has led to the obliteration of the difference in the quality of bowel preparation between morning and afternoon colonoscopies.16 Prospective trials are needed to evaluate the use of split preparations to improve the quality of afternoon inpatient colonoscopies.

Few other strategies have been shown to mitigate IBP in the inpatient setting. In a small randomized controlled trial, Ergen et al. found that providing an educational booklet improved inpatient bowel preparation as measured by the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale.17 In a quasi-experimental design, Yadlapati et al. found that an automated split-dose bowel preparation resulted in decreased IBP, fewer repeated procedures, shorter LOS, and lower hospital cost.18 Our study adds to these tools by identifying three additional risk factors which could be optimized for inpatients. Because our findings are observational, they should be subjected to prospective trials. Our study also calls into question the impact of bowel preparation volume. We found no difference in the rate of IBP between low and large volume preparations. It is possible that other factors are more important than the specific preparation employed.

Interestingly, we found that IBP declined substantially in 2014 and continued to decline after that. The year was the most influential risk factor for IBP (on par with gastroparesis). The reason for this is unclear, as rates of our modifiable risk factors did not differ substantially by year. Other possibilities include improved access (including weekend access) to endoscopy coinciding with the development of a new endoscopy facility and use of integrated irrigation pump system instead of the use of manual syringes for flushing.

Our study has many strengths. It is by far the most extensive study of bowel preparation quality in inpatients to date and the only one that has included patient, procedural and bowel preparation characteristics. The study also has several significant limitations. This is a single center study, which could limit generalizability. Nonetheless, it was conducted within a health system with multiple hospitals in different parts of the United States (Ohio and Florida) and included a broad population mix with differing levels of acuity. The retrospective nature of the assessment precludes establishing causation. However, we mitigated confounding by adjusting for a wide variety of factors, and there is a plausible physiological mechanism for each of the factors we studied. Also, the retrospective nature of our study predisposes our data to omissions and misrepresentations during the documentation process. This is especially true with the use of ICD codes.19 Inaccuracies in coding are likely to bias toward the null, so observed associations may be an underestimate of the true association.

Our inability to ascertain if a patient completed the prescribed bowel preparation limited our ability to detect what may be a significant risk factor. Lastly, while clinically relevant, the Aronchik scale used to identify adequate from IBP has never been validated though it is frequently utilized and cited in the bowel preparation literature.20

CONCLUSIONS

In this large retrospective study evaluating bowel preparation quality in inpatients undergoing colonoscopy, we found that more than half of the patients have IBP and that IBP was associated with an extra day of hospitalization. Our study identifies those patients at highest risk and identifies modifiable risk factors for IBP. Specifically, we found that abstinence from opiates or solid diet before the colonoscopy, along with performing colonoscopies before noon were associated with improved outcomes. Prospective studies are needed to confirm the effects of these interventions on bowel preparation quality.

Disclosures

Carol A Burke, MD has received research funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals. Other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Yadlapati R, Johnston ER, Gregory DL, Ciolino JD, Cooper A, Keswani RN. Predictors of inadequate inpatient colonoscopy preparation and its association with hospital length of stay and costs. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(11):3482-3490. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3761-2. PubMed

2. Jawa H, Mosli M, Alsamadani W, et al. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for inpatient colonoscopy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28(6):460-464. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2017.17196. PubMed

3. Mcnabb-Baltar J, Dorreen A, Dhahab HA, et al. Age is the only predictor of poor bowel preparation in the hospitalized patient. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:1-5. doi: 10.1155/2016/2139264. PubMed

4. Rotondano G, Rispo A, Bottiglieri ME, et al. Tu1503 Quality of bowel cleansing in hospitalized patients is not worse than that of outpatients undergoing colonoscopy: results of a multicenter prospective regional study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(5):AB564. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.02.949. PubMed

5. Ness R. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(6):1797-1802. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(01)02437-6. PubMed

6. Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the us multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(4):903-924. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.002. PubMed

7. Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, et al. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52(3):346-352. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108480. PubMed

8. Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers J-J, Burnand B, Vader J-P. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(3):378-384. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2. PubMed

9. Sarvepalli S, Garber A, Rizk M, et al. 923 adjusted comparison of commercial bowel preparations based on inadequacy of bowel preparation in outpatient settings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87(6):AB127. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.04.1331.

10. Hendry PO, Jenkins JT, Diament RH. The impact of poor bowel preparation on colonoscopy: a prospective single center study of 10 571 colonoscopies. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(8):745-748. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01220.x. PubMed

11. Lebwohl B, Wang TC, Neugut AI. Socioeconomic and other predictors of colonoscopy preparation quality. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(7):2014-2020. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1079-7. PubMed

12. Chorev N, Chadad B, Segal N, et al. Preparation for colonoscopy in hospitalized patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(3):835-839. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9591-5. PubMed

13. Weiss AJ. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #180. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. PubMed

14. Kojecky V, Matous J, Keil R, et al. The optimal bowel preparation intervals before colonoscopy: a randomized study comparing polyethylene glycol and low-volume solutions. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50(3):271-276. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.10.010. PubMed

15. Siddiqui AA, Yang K, Spechler SJ, et al. Duration of the interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy predicts bowel-preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3):700-706. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.047. PubMed

16. Eun CS, Han DS, Hyun YS, et al. The timing of bowel preparation is more important than the timing of colonoscopy in determining the quality of bowel cleansing. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;56(2):539-544. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1457-1. PubMed

17. Ergen WF, Pasricha T, Hubbard FJ, et al. Providing hospitalized patients with an educational booklet increases the quality of colonoscopy bowel preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(6):858-864. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.015. PubMed

18. Yadlapati R, Johnston ER, Gluskin AB, et al. An automated inpatient split-dose bowel preparation system improves colonoscopy quality and reduces repeat procedures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(8):709-714. doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000849. PubMed

19. Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, Nilasena DS, Radford MJ, Gage BF. The accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med Care. 2005;43(5):480-485. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160417.39497.a9. PubMed

20. Parmar R, Martel M, Rostom A, Barkun AN. Validated scales for colon cleansing: a systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;111(2):197-204. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.417. PubMed

1. Yadlapati R, Johnston ER, Gregory DL, Ciolino JD, Cooper A, Keswani RN. Predictors of inadequate inpatient colonoscopy preparation and its association with hospital length of stay and costs. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60(11):3482-3490. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3761-2. PubMed

2. Jawa H, Mosli M, Alsamadani W, et al. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for inpatient colonoscopy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017;28(6):460-464. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2017.17196. PubMed

3. Mcnabb-Baltar J, Dorreen A, Dhahab HA, et al. Age is the only predictor of poor bowel preparation in the hospitalized patient. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;2016:1-5. doi: 10.1155/2016/2139264. PubMed

4. Rotondano G, Rispo A, Bottiglieri ME, et al. Tu1503 Quality of bowel cleansing in hospitalized patients is not worse than that of outpatients undergoing colonoscopy: results of a multicenter prospective regional study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(5):AB564. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.02.949. PubMed

5. Ness R. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(6):1797-1802. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9270(01)02437-6. PubMed

6. Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, et al. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the us multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(4):903-924. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.07.002. PubMed

7. Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, et al. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52(3):346-352. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108480. PubMed

8. Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers J-J, Burnand B, Vader J-P. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61(3):378-384. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02776-2. PubMed

9. Sarvepalli S, Garber A, Rizk M, et al. 923 adjusted comparison of commercial bowel preparations based on inadequacy of bowel preparation in outpatient settings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87(6):AB127. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2018.04.1331.

10. Hendry PO, Jenkins JT, Diament RH. The impact of poor bowel preparation on colonoscopy: a prospective single center study of 10 571 colonoscopies. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9(8):745-748. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.01220.x. PubMed

11. Lebwohl B, Wang TC, Neugut AI. Socioeconomic and other predictors of colonoscopy preparation quality. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55(7):2014-2020. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-1079-7. PubMed

12. Chorev N, Chadad B, Segal N, et al. Preparation for colonoscopy in hospitalized patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2007;52(3):835-839. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9591-5. PubMed

13. Weiss AJ. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #180. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2014. PubMed

14. Kojecky V, Matous J, Keil R, et al. The optimal bowel preparation intervals before colonoscopy: a randomized study comparing polyethylene glycol and low-volume solutions. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50(3):271-276. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2017.10.010. PubMed

15. Siddiqui AA, Yang K, Spechler SJ, et al. Duration of the interval between the completion of bowel preparation and the start of colonoscopy predicts bowel-preparation quality. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69(3):700-706. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.09.047. PubMed

16. Eun CS, Han DS, Hyun YS, et al. The timing of bowel preparation is more important than the timing of colonoscopy in determining the quality of bowel cleansing. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;56(2):539-544. doi: 10.1007/s10620-010-1457-1. PubMed

17. Ergen WF, Pasricha T, Hubbard FJ, et al. Providing hospitalized patients with an educational booklet increases the quality of colonoscopy bowel preparation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(6):858-864. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.11.015. PubMed

18. Yadlapati R, Johnston ER, Gluskin AB, et al. An automated inpatient split-dose bowel preparation system improves colonoscopy quality and reduces repeat procedures. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2018;52(8):709-714. doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000849. PubMed

19. Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, Nilasena DS, Radford MJ, Gage BF. The accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Med Care. 2005;43(5):480-485. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160417.39497.a9. PubMed

20. Parmar R, Martel M, Rostom A, Barkun AN. Validated scales for colon cleansing: a systematic review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;111(2):197-204. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.417. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Resuming Anticoagulation following Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding among Patients with Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation—A Microsimulation Analysis

Anticoagulation is commonly used in the management of atrial fibrillation to reduce the risk of ischemic stroke. Warfarin and other anticoagulants increase the risk of hemorrhagic complications, including upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). Following UGIB, management of anticoagulation is highly variable. Many patients permanently discontinue anticoagulation, while others continue without interruption.1-4 Among patients who resume warfarin, different cohorts have measured median times to resumption ranging from four days to 50 days.1-3 Outcomes data are sparse, and clinical guidelines offer little direction.5

Following UGIB, the balance between the risks and benefits of anticoagulation changes over time. Rebleeding risk is highest immediately after the event and declines quickly; therefore, rapid resumption of anticoagulation causes patient harm.3 Meanwhile, the risk of stroke remains constant, and delay in resumption of anticoagulation is associated with increased risk of stroke and death.1 At some point in time following the initial UGIB, the expected harm from bleeding would equal the expected harm from stroke. This time point would represent the optimal time to restart anticoagulation.

Trial data are unlikely to identify the optimal time for restarting anticoagulation. A randomized trial comparing discrete reinitiation times (eg, two weeks vs six weeks) may easily miss the optimal timing. Moreover, because the daily probability of thromboembolic events is low, large numbers of patients would be required to power such a study. In addition, a number of oral anticoagulants are now approved for prevention of thromboembolic stroke in atrial fibrillation, and each drug may have different optimal timing.

In contrast to randomized trials that would be impracticable for addressing this clinical issue, microsimulation modeling can provide granular information regarding the optimal time to restart anticoagulation. Herein, we set out to estimate the expected benefit of reinitiation of warfarin, the most commonly used oral anticoagulant,6 or apixaban, the direct oral anticoagulant with the most favorable risk profile,7 as a function of days after UGIB.

METHODS

We previously described a microsimulation model of anticoagulation among patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF; hereafter, we refer to this model as the Personalized Anticoagulation Decision-Making Assistance model, or PADMA).8,9 For this study, we extended this model to incorporate the probability of rebleeding following UGIB and include apixaban as an alternative to warfarin. This model begins with a synthetic population following UGIB, the members of which are at varying risk for thromboembolism, recurrent UGIB, and other hemorrhages. For each patient, the model simulates a number of possible events (eg, thromboembolic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, rebleeding, and other major extracranial hemorrhages) on each day of an acute period of 90 days after hemostasis. Patients who survive until the end of the acute period enter a simulation with annual, rather than daily, cycles. Our model then estimates total quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for each patient, discounted to the present. We report the average discounted QALYs produced by the model for the same population if all individuals in our input population were to resume either warfarin or apixaban on a specific day. Input parameters and ranges are summarized in Table 1, a simplified schematic of our model is shown in the Supplemental Appendix, and additional details regarding model structure and assumptions can be found in earlier work.8,9 We simulated from a health system perspective over a lifelong time horizon. All analyses were performed in version 14 of Stata (StataCorp, LLC, College Station, Texas).

Synthetic Population

To generate a population reflective of the comorbidities and age distribution of the US population with NVAF, we merged relevant variables from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES; 2011-2012), using multiple imputation to correct for missing variables.10 We then bootstrapped to national population estimates by age and sex to arrive at a hypothetical population of the United States.11 Because NHANES does not include atrial fibrillation, we applied sex- and age-specific prevalence rates from the AnTicoagulation and Risk Factors In Atrial Fibrillation study.12 We then calculated commonly used risk scores (CHA2DS2-Vasc and HAS-BLED) for each patient and limited the population to patients with a CHA2DS2-Vasc score of one or greater.13,14 The population resuming apixaban was further limited to patients whose creatinine clearance was 25 mL/min or greater in keeping with the entry criteria in the phase 3 clinical trial on which the medication’s approval was based.15

To estimate patient-specific probability of rebleeding, we generated a Rockall score for each patient.16 Although the discrimination of the Rockall score is limited for individual patients, as with all other tools used to predict rebleeding following UGIB, the Rockall score has demonstrated reasonable calibration across a threefold risk gradient.17-19 International consensus guidelines recommend the Rockall score as one of two risk prediction tools for clinical use in the management of patients with UGIB.20 In addition, because the Rockall score includes some demographic components (five of a possible 11 points), our estimates of rebleeding risk are covariant with other patient-specific risks. We assumed that the endoscopic components of the Rockall score were present in our cohort at the same frequency as in the original derivation and are independent of known patient risk factors.16 For example, 441 out of 4,025 patients in the original Rockall derivation cohort presented with a systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg. We assumed that an independent and random 10.96% of the cohort would present with shock, which confers two points in the Rockall score.

The population was replicated 60 times, with identical copies of the population resuming anticoagulation on each of days 1-60 (where day zero represents hemostasis). Intermediate data regarding our simulated population can be found in the Supplemental Appendix and in prior work.

Event Type, Severity, and Mortality

Each patient in our simulation could sustain several discrete and independent events: ischemic stroke, intracranial hemorrhage, recurrent UGIB, or extracranial major hemorrhage other than recurrent UGIB. As in prior analyses using the PADMA model, we did not consider minor hemorrhagic events.8

The probability of each event was conditional on the corresponding risk scoring system. Patient-specific probability of ischemic stroke was conditional on CHA2DS2-Vasc score.21,22 Patient-specific probability of intracranial hemorrhage was conditional on HAS-BLED score, with the proportions of intracranial hemorrhage of each considered subtype (intracerebral, subarachnoid, or subdural) bootstrapped from previously-published data.21-24 Patient-specific probability of rebleeding was conditional on Rockall score from the combined Rockall and Vreeburg validation cohorts.17 Patient-specific probability of extracranial major hemorrhage was conditional on HAS-BLED score.21 To avoid double-counting of UGIB, we subtracted the baseline risk of UGIB from the overall rate of extracranial major hemorrhages using previously-published data regarding relative frequency and a bootstrapping approach.25

Probability of Rebleeding Over Time

To estimate the decrease in rebleeding risk over time, we searched the Medline database for systematic reviews of recurrent bleeding following UGIB using the strategy detailed in the Supplemental Appendix. Using the interval rates of rebleeding we identified, we calculated implied daily rates of rebleeding at the midpoint of each interval. For example, 39.5% of rebleeding events occurred within three days of hemostasis, implying a daily rate of approximately 13.2% on day two (32 of 81 events over a three-day period). We repeated this process to estimate daily rates at the midpoint of each reported time interval and fitted an exponential decay function.26 Our exponential fitted these datapoints quite well, but we lacked sufficient data to test other survival functions (eg, Gompertz, lognormal, etc.). Our fitted exponential can be expressed as:

P rebleeding = b 0 *exp(b 1 *day)

where b0 = 0.1843 (SE: 0.0136) and b1 = –0.1563 (SE: 0.0188). For example, a mean of 3.9% of rebleeding episodes will occur on day 10 (0.1843 *exp(–0.1563 *10)).

Relative Risks of Events with Anticoagulation

For patients resuming warfarin, the probabilities of each event were adjusted based on patient-specific daily INR. All INRs were assumed to be 1.0 until the day of warfarin reinitiation, after which interpolated trajectories of postinitiation INR measurements were sampled for each patient from an earlier study of clinical warfarin initiation.27 Relative risks of ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic events were calculated based on each day’s INR.

For patients taking apixaban, we assumed that the medication would reach full therapeutic effect one day after reinitiation. Based on available evidence, we applied the relative risks of each event with apixaban compared with warfarin.25

Future Disability and Mortality

Each event in our simulation resulted in hospitalization. Length of stay was sampled for each diagnosis.28 The disutility of hospitalization was estimated based on length of stay.8 Inpatient mortality and future disability were predicted for each event as previously described.8 We assumed that recurrent episodes of UGIB conferred morbidity and mortality identical to extracranial major hemorrhages more broadly.29,30

Disutilities

We used a multiplicative model for disutility with baseline utilities conditional on age and sex.31 Each day after resumption of anticoagulation carried a disutility of 0.012 for warfarin or 0.002 for apixaban, which we assumed to be equivalent to aspirin in disutility.32 Long-term disutility and life expectancy were conditional on modified Rankin Score (mRS).33,34 We discounted all QALYs to day zero using standard exponential discounting and a discount rate centered at 3%. We then computed the average discounted QALYs among the cohort of patients that resumed anticoagulation on each day following the index UGIB.

Sensitivity Analyses and Metamodel

To assess sensitivity to continuously varying input parameters, such as discount rate, the proportion of extracranial major hemorrhages that are upper GI bleeds, and inpatient mortality from extracranial major hemorrhage, we constructed a metamodel (a regression model of our microsimulation results).35 We tested for interactions among input parameters and dropped parameters that were not statistically significant predictors of discounted QALYs from our metamodel. We then tested for interactions between each parameter and day resuming anticoagulation to determine which factors may impact the optimal day of reinitiation. Finally, we used predicted marginal effects from our metamodel to assess the change in optimal day across the ranges of each input parameter when other parameters were held at their medians.

RESULTS

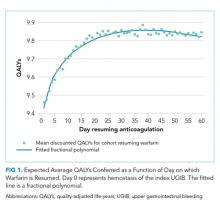

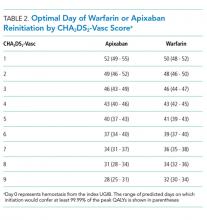

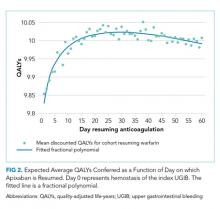

Resuming warfarin on day zero produced the fewest QALYs. With delay in reinitiation of anticoagulation, expected QALYs increased, peaked, and then declined for all scenarios. In our base-case simulation of warfarin, peak utility was achieved by resumption 41 days after the index UGIB. Resumption between days 32 and 51 produced greater than 99.9% of peak utility. In our base-case simulation of apixaban, peak utility was achieved by resumption 32 days after the index UGIB. Resumption between days 21 and 47 produced greater than 99.9% of peak utility. Results for warfarin and apixaban are shown in Figures 1 and 2, respectively.

The optimal day of warfarin reinitiation was most sensitive to CHA2DS2-Vasc scores and varied by around 11 days between a CHA2DS2-Vasc score of one and a CHA2DS2-Vasc score of six (the 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively) when all other parameters are held at their medians. Results were comparatively insensitive to rebleeding risk. Varying Rockall score from two to seven (the 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively) added three days to optimal warfarin resumption. Varying other parameters from the 5th to the 95th percentile (including HAS-BLED score, sex, age, and discount rate) changed expected QALYs but did not change the optimal day of reinitiation of warfarin. Optimal day of reinitiation for warfarin stratified by CHA2DS2-Vasc score is shown in Table 2.

Sensitivity analyses for apixaban produced broadly similar results, but with greater sensitivity to rebleeding risk. Optimal day of reinitiation varied by 15 days over the examined range of CHA2DS2-Vasc scores (Table 2) and by six days over the range of Rockall scores (Supplemental Appendix). Other input parameters, including HAS-BLED score, age, sex, and discount rate, changed expected QALYs and were significant in our metamodel but did not affect the optimal day of reinitiation. Metamodel results for both warfarin and apixaban are included in the Supplemental Appendix.

DISCUSSION

Anticoagulation is frequently prescribed for patients with NVAF, and hemorrhagic complications are common. Although anticoagulants are withheld following hemorrhages, scant evidence to inform the optimal timing of reinitiation is available. In this microsimulation analysis, we found that the optimal time to reinitiate anticoagulation following UGIB is around 41 days for warfarin and around 32 days for apixaban. We have further demonstrated that the optimal timing of reinitiation can vary by nearly two weeks, depending on a patient’s underlying risk of stroke, and that early reinitiation is more sensitive to rebleeding risk than late reinitiation.

Prior work has shown that early reinitiation of anticoagulation leads to higher rates of recurrent hemorrhage while failure to reinitiate anticoagulation is associated with higher rates of stroke and mortality.1-4,36 Our results add to the literature in a number of important ways. First, our model not only confirms that anticoagulation should be restarted but also suggests when this action should be taken. The competing risks of bleeding and stroke have left clinicians with little guidance; we have quantified the clinical reasoning required for the decision to resume anticoagulation. Second, by including the disutility of hospitalization and long-term disability, our model more accurately represents the complex tradeoffs between recurrent hemorrhage and (potentially disabling) stroke than would a comparison of event rates. Third, our model is conditional upon patient risk factors, allowing clinicians to personalize the timing of anticoagulation resumption. Theory would suggest that patients at higher risk of ischemic stroke benefit from earlier resumption of anticoagulation, while patients at higher risk of hemorrhage benefit from delayed reinitiation. We have quantified the extent to which patient-specific risks should change timing. Fourth, we offer a means of improving expected health outcomes that requires little more than appropriate scheduling. Current practice regarding resuming anticoagulation is widely variable. Many patients never resume warfarin, and those that do resume do so after highly varied periods of time.1-5,36 We offer a means of standardizing clinical practice and improving expected patient outcomes.

Interestingly, patient-specific risk of rebleeding had little effect on our primary outcome for warfarin, and a greater effect in our simulation of apixaban. It would seem that rebleeding risk, which decreases roughly exponentially, is sufficiently low by the time period at which warfarin should be resumed that patient-specific hemorrhage risk factors have little impact. Meanwhile, at the shorter post-event intervals at which apixaban can be resumed, both stroke risk and patient-specific bleeding risk are worthy considerations.

Our model is subject to several important limitations. First, our predictions of the optimal day as a function of risk scores can only be as well-calibrated as the input scoring systems. It is intuitive that patients with higher risk of rebleeding benefit from delayed reinitiation, while patients with higher risk of thromboembolic stroke benefit from earlier reinitiation. Still, clinicians seeking to operationalize competing risks through these two scores—or, indeed, any score—should be mindful of their limited calibration and shared variance. In other words, while the optimal day of reinitiation is likely in the range we have predicted and varies to the degree demonstrated here, the optimal day we have predicted for each score is likely overly precise. However, while better-calibrated prediction models would improve the accuracy of our model, we believe ours to be the best estimate of timing given available data and this approach to be the most appropriate way to personalize anticoagulation resumption.

Our simulation of apixaban carries an additional source of potential miscalibration. In the clinical trials that led to their approval, apixaban and other direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) were compared with warfarin over longer periods of time than the acute period simulated in this work. Over a short period of time, patients treated with more rapidly therapeutic medications (in this case, apixaban) would receive more days of effective therapy compared with a slower-onset medication, such as warfarin. Therefore, the relative risks experienced by patients are likely different over the time period we have simulated compared with those measured over longer periods of time (as in phase 3 clinical trials). Our results for apixaban should be viewed as more limited than our estimates for warfarin. More broadly, simulation analyses are intended to predict overall outcomes that are difficult to measure. While other frameworks to assess model credibility exist, the fact remains that no extant datasets can directly validate our predictions.37

Our findings are limited to patients with NVAF. Anticoagulants are prescribed for a variety of indications with widely varied underlying risks and benefits. Models constructed for these conditions would likely produce different timing for resumption of anticoagulation. Unfortunately, large scale cohort studies to inform such models are lacking. Similarly, we simulated UGIB, and our results should not be generalized to populations with other types of bleeding (eg, intracranial hemorrhage). Again, cohort studies of other types of bleeding would be necessary to understand the risks of anticoagulation over time in such populations.

Higher-quality data regarding risk of rebleeding over time would improve our estimates. Our literature search identified only one systematic review that could be used to estimate the risk of recurrent UGIB over time. These data are not adequate to interrogate other forms this survival curve could take, such as Gompertz or Weibull distributions. Recurrence risk almost certainly declines over time, but how quickly it declines carries additional uncertainty.

Despite these limitations, we believe our results to be the best estimates to date of the optimal time of anticoagulation reinitiation following UGIB. Our findings could help inform clinical practice guidelines and reduce variation in care where current practice guidelines are largely silent. Given the potential ease of implementing scheduling changes, our results represent an opportunity to improve patient outcomes with little resource investment.

In conclusion, after UGIB associated with anticoagulation, our model suggests that warfarin is optimally restarted approximately six weeks following hemostasis and that apixaban is optimally restarted approximately one month following hemostasis. Modest changes to this timing based on probability of thromboembolic stroke are reasonable.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

1. Witt DM, Delate T, Garcia DA, et al. Risk of thromboembolism, recurrent hemorrhage, and death after warfarin therapy interruption for gastrointestinal tract bleeding. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1484-1491. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4261. PubMed

2. Sengupta N, Feuerstein JD, Patwardhan VR, et al. The risks of thromboembolism vs recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding after interruption of systemic anticoagulation in hospitalized inpatients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(2):328-335. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.398. PubMed

3. Qureshi W, Mittal C, Patsias I, et al. Restarting anticoagulation and outcomes after major gastrointestinal bleeding in atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(4):662-668. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.10.044. PubMed

4. Milling TJ, Spyropoulos AC. Re-initiation of dabigatran and direct factor Xa antagonists after a major bleed. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(11):19-25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2016.09.049. PubMed

5. Brotman DJ, Jaffer AK. Resuming anticoagulation in the first week following gastrointestinal tract hemorrhage. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(19):1492-1493. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.4309. PubMed

6. Barnes GD, Lucas E, Alexander GC, Goldberger ZD. National trends in ambulatory oral anticoagulant use. Am J Med. 2015;128(12):1300-5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.05.044. PubMed

7. Noseworthy PA, Yao X, Abraham NS, Sangaralingham LR, McBane RD, Shah ND. Direct comparison of dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and apixaban for effectiveness and safety in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2016;150(6):1302-1312. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.07.013. PubMed

8. Pappas MA, Barnes GD, Vijan S. Personalizing bridging anticoagulation in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation—a microsimulation analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):464-470. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3932-7. PubMed