User login

Hospital medicine physician leaders

The right skills and time to develop them

“When you get someone who knows what quality looks like and pair that with curiosity about new ways to think about leading, you end up with the people who are able to produce dramatic innovations in the field.”1

In medicine, a physician is trained to take charge in emergent situations and make potentially lifesaving efforts. However, when it comes to leading teams of individuals, not only must successful leaders have the right skills, they also need time to dedicate to the work of leadership.

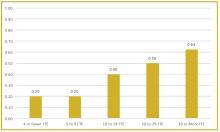

To better understand current approaches to dedicated hospital medicine group (HMG) leadership time, let’s examine the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report. The survey, upon which the Report was based, examined two aspects of leadership: 1) how much dedicated time a leader receives to manage the group; and 2) how the leader’s time is compensated. Looking closely at the data displayed in graphs from the SoHM Report (Figures 1, 2, and 3), we can see that dedicated administrative time is directly proportional to the size of the group.

In my current role as a regional medical director in the Dallas-Fort Worth market, I oversee some programs where the size is greater than 30 full-time equivalents (FTEs), and requires a full-time administrative physician leader to manage the group. Their daily administrative duties include, but are not limited to, addressing physician performance and behaviors, managing team performance metrics, dealing with consultants’ expectations, attending and leading various committee meetings at the hospital or the system level, attending and presenting performance reviews, leading and preparing for team meetings, as well as addressing and being innovative in leading new initiatives from the hospital partner system.

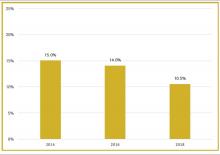

Although physician leaders are paid more for their work, the 2018 SoHM Report reveals a decline in the premium year over year. One of the reasons for the payment decline that I have encountered in various groups is that their incentives for leading the group are based on performance, as opposed to receiving a fixed stipend. Another reason is the presence of dedicated administrative support or the inclusion of a performance improvement staffer, such as an additional nurse or advanced practice provider, in the group.

Evidence suggests that organizations and patients benefit when physicians take on leadership roles. Physician leaders play critical roles in providing high-quality patient care. How can the Society of Hospital Medicine help? Management degrees and leadership workshops have become a common pathway for many physicians, including myself. SHM provides one of the most thorough and relevant experiences through the SHM Leadership Academy. The focus of the Leadership Academy is on developing a broad set of additional leadership competencies across a spectrum of experience.5 As hospitalist physicians are often expected to fulfill a broader leadership void, we must pay attention to developing the leadership skills depicted in Figure 3. Hospital medicine is an ideal “proving ground” for future physician executives and leaders, as they often share the same characteristics required for success.

The leadership paths available in my organization, Sound Physicians, were recently highlighted in a New York Times article.3 Sound Physicians employs more than 3,000 physicians across the country, and has a pipeline for doctors to advance through structured rungs of leadership – emphasizing a different mix of clinical, strategic, and business skills at each stage, from individual practitioner to the C-suite. The training includes in-person and online courses, as well as an annual conference, to help doctors develop management and leadership competencies, and learn how to apply these skills within their organizations. Since introducing its leadership development program, the company reports less turnover, higher morale, and better growth. I personally have gone through the leadership training provided by Sound Physicians, and reflecting back, it has been a transformational experience for me. Leadership is a journey, not a destination, and as physicians we should strive to learn more from the health care leaders around us.

The administrative workload for hospital-based physician leaders will increase with the arrival of value-based programs and alternative payment models promoted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Lead hospitalist duties are not limited to daily operations, but can extend to leading the strategic vision of the hospital or health system. The 2020 SoHM Report will reflect these changes, as well as provide further information about how to manage and set expectations for physician leaders, based on group size and employment model.

Dr. Patel is a regional medical director with Sound Physicians. He manages more than 100 FTE hospitalists and advanced-practice providers (APPs) within multiple health systems and hospitals in the Texas market. He also serves as a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee and as a vice president of SHM North Texas Chapter.

References

1. Angood P and Birk S. The Value of Physician Leadership. Physician Exec. 2014 May-Jun;40(3):6-20.

2. Rice JA. Expanding the Need for Physician Leaders. Executive Insight, Advance Healthcare Network, Nov 16, 2011. Available at: http://healthcare-executive-insight.advanceweb.com/Features/Articles/Expanding-the-Need-for-Physician-Leaders.aspx.

3. Khullar D. Good leaders make good doctors. New York Times. 2019 Nov 21.

4. Beresford L. The State of Hospital Medicine in 2018. Hospitalist. 2019;23(1):1-11.

5. Harte B. Hospitalists can meet the demand for physician executives. Hospitalist. 2018 Nov 29.

The right skills and time to develop them

The right skills and time to develop them

“When you get someone who knows what quality looks like and pair that with curiosity about new ways to think about leading, you end up with the people who are able to produce dramatic innovations in the field.”1

In medicine, a physician is trained to take charge in emergent situations and make potentially lifesaving efforts. However, when it comes to leading teams of individuals, not only must successful leaders have the right skills, they also need time to dedicate to the work of leadership.

To better understand current approaches to dedicated hospital medicine group (HMG) leadership time, let’s examine the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report. The survey, upon which the Report was based, examined two aspects of leadership: 1) how much dedicated time a leader receives to manage the group; and 2) how the leader’s time is compensated. Looking closely at the data displayed in graphs from the SoHM Report (Figures 1, 2, and 3), we can see that dedicated administrative time is directly proportional to the size of the group.

In my current role as a regional medical director in the Dallas-Fort Worth market, I oversee some programs where the size is greater than 30 full-time equivalents (FTEs), and requires a full-time administrative physician leader to manage the group. Their daily administrative duties include, but are not limited to, addressing physician performance and behaviors, managing team performance metrics, dealing with consultants’ expectations, attending and leading various committee meetings at the hospital or the system level, attending and presenting performance reviews, leading and preparing for team meetings, as well as addressing and being innovative in leading new initiatives from the hospital partner system.

Although physician leaders are paid more for their work, the 2018 SoHM Report reveals a decline in the premium year over year. One of the reasons for the payment decline that I have encountered in various groups is that their incentives for leading the group are based on performance, as opposed to receiving a fixed stipend. Another reason is the presence of dedicated administrative support or the inclusion of a performance improvement staffer, such as an additional nurse or advanced practice provider, in the group.

Evidence suggests that organizations and patients benefit when physicians take on leadership roles. Physician leaders play critical roles in providing high-quality patient care. How can the Society of Hospital Medicine help? Management degrees and leadership workshops have become a common pathway for many physicians, including myself. SHM provides one of the most thorough and relevant experiences through the SHM Leadership Academy. The focus of the Leadership Academy is on developing a broad set of additional leadership competencies across a spectrum of experience.5 As hospitalist physicians are often expected to fulfill a broader leadership void, we must pay attention to developing the leadership skills depicted in Figure 3. Hospital medicine is an ideal “proving ground” for future physician executives and leaders, as they often share the same characteristics required for success.

The leadership paths available in my organization, Sound Physicians, were recently highlighted in a New York Times article.3 Sound Physicians employs more than 3,000 physicians across the country, and has a pipeline for doctors to advance through structured rungs of leadership – emphasizing a different mix of clinical, strategic, and business skills at each stage, from individual practitioner to the C-suite. The training includes in-person and online courses, as well as an annual conference, to help doctors develop management and leadership competencies, and learn how to apply these skills within their organizations. Since introducing its leadership development program, the company reports less turnover, higher morale, and better growth. I personally have gone through the leadership training provided by Sound Physicians, and reflecting back, it has been a transformational experience for me. Leadership is a journey, not a destination, and as physicians we should strive to learn more from the health care leaders around us.

The administrative workload for hospital-based physician leaders will increase with the arrival of value-based programs and alternative payment models promoted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Lead hospitalist duties are not limited to daily operations, but can extend to leading the strategic vision of the hospital or health system. The 2020 SoHM Report will reflect these changes, as well as provide further information about how to manage and set expectations for physician leaders, based on group size and employment model.

Dr. Patel is a regional medical director with Sound Physicians. He manages more than 100 FTE hospitalists and advanced-practice providers (APPs) within multiple health systems and hospitals in the Texas market. He also serves as a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee and as a vice president of SHM North Texas Chapter.

References

1. Angood P and Birk S. The Value of Physician Leadership. Physician Exec. 2014 May-Jun;40(3):6-20.

2. Rice JA. Expanding the Need for Physician Leaders. Executive Insight, Advance Healthcare Network, Nov 16, 2011. Available at: http://healthcare-executive-insight.advanceweb.com/Features/Articles/Expanding-the-Need-for-Physician-Leaders.aspx.

3. Khullar D. Good leaders make good doctors. New York Times. 2019 Nov 21.

4. Beresford L. The State of Hospital Medicine in 2018. Hospitalist. 2019;23(1):1-11.

5. Harte B. Hospitalists can meet the demand for physician executives. Hospitalist. 2018 Nov 29.

“When you get someone who knows what quality looks like and pair that with curiosity about new ways to think about leading, you end up with the people who are able to produce dramatic innovations in the field.”1

In medicine, a physician is trained to take charge in emergent situations and make potentially lifesaving efforts. However, when it comes to leading teams of individuals, not only must successful leaders have the right skills, they also need time to dedicate to the work of leadership.

To better understand current approaches to dedicated hospital medicine group (HMG) leadership time, let’s examine the 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) Report. The survey, upon which the Report was based, examined two aspects of leadership: 1) how much dedicated time a leader receives to manage the group; and 2) how the leader’s time is compensated. Looking closely at the data displayed in graphs from the SoHM Report (Figures 1, 2, and 3), we can see that dedicated administrative time is directly proportional to the size of the group.

In my current role as a regional medical director in the Dallas-Fort Worth market, I oversee some programs where the size is greater than 30 full-time equivalents (FTEs), and requires a full-time administrative physician leader to manage the group. Their daily administrative duties include, but are not limited to, addressing physician performance and behaviors, managing team performance metrics, dealing with consultants’ expectations, attending and leading various committee meetings at the hospital or the system level, attending and presenting performance reviews, leading and preparing for team meetings, as well as addressing and being innovative in leading new initiatives from the hospital partner system.

Although physician leaders are paid more for their work, the 2018 SoHM Report reveals a decline in the premium year over year. One of the reasons for the payment decline that I have encountered in various groups is that their incentives for leading the group are based on performance, as opposed to receiving a fixed stipend. Another reason is the presence of dedicated administrative support or the inclusion of a performance improvement staffer, such as an additional nurse or advanced practice provider, in the group.

Evidence suggests that organizations and patients benefit when physicians take on leadership roles. Physician leaders play critical roles in providing high-quality patient care. How can the Society of Hospital Medicine help? Management degrees and leadership workshops have become a common pathway for many physicians, including myself. SHM provides one of the most thorough and relevant experiences through the SHM Leadership Academy. The focus of the Leadership Academy is on developing a broad set of additional leadership competencies across a spectrum of experience.5 As hospitalist physicians are often expected to fulfill a broader leadership void, we must pay attention to developing the leadership skills depicted in Figure 3. Hospital medicine is an ideal “proving ground” for future physician executives and leaders, as they often share the same characteristics required for success.

The leadership paths available in my organization, Sound Physicians, were recently highlighted in a New York Times article.3 Sound Physicians employs more than 3,000 physicians across the country, and has a pipeline for doctors to advance through structured rungs of leadership – emphasizing a different mix of clinical, strategic, and business skills at each stage, from individual practitioner to the C-suite. The training includes in-person and online courses, as well as an annual conference, to help doctors develop management and leadership competencies, and learn how to apply these skills within their organizations. Since introducing its leadership development program, the company reports less turnover, higher morale, and better growth. I personally have gone through the leadership training provided by Sound Physicians, and reflecting back, it has been a transformational experience for me. Leadership is a journey, not a destination, and as physicians we should strive to learn more from the health care leaders around us.

The administrative workload for hospital-based physician leaders will increase with the arrival of value-based programs and alternative payment models promoted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Lead hospitalist duties are not limited to daily operations, but can extend to leading the strategic vision of the hospital or health system. The 2020 SoHM Report will reflect these changes, as well as provide further information about how to manage and set expectations for physician leaders, based on group size and employment model.

Dr. Patel is a regional medical director with Sound Physicians. He manages more than 100 FTE hospitalists and advanced-practice providers (APPs) within multiple health systems and hospitals in the Texas market. He also serves as a member of the SHM Practice Analysis Committee and as a vice president of SHM North Texas Chapter.

References

1. Angood P and Birk S. The Value of Physician Leadership. Physician Exec. 2014 May-Jun;40(3):6-20.

2. Rice JA. Expanding the Need for Physician Leaders. Executive Insight, Advance Healthcare Network, Nov 16, 2011. Available at: http://healthcare-executive-insight.advanceweb.com/Features/Articles/Expanding-the-Need-for-Physician-Leaders.aspx.

3. Khullar D. Good leaders make good doctors. New York Times. 2019 Nov 21.

4. Beresford L. The State of Hospital Medicine in 2018. Hospitalist. 2019;23(1):1-11.

5. Harte B. Hospitalists can meet the demand for physician executives. Hospitalist. 2018 Nov 29.

What is the best way to manage GERD symptoms in the elderly?

No evidence supports one method over another in managing uncomplicated gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for patients aged >65 years. For those with endoscopically documented esophagitis, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) relieve symptoms faster than histamine H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, extrapolation from randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). Treating elderly patients with pantoprazole (Protonix) after resolution of acute esophagitis results in fewer relapses than with placebo (SOR: B, double-blind RCT). Limited evidence suggests that such maintenance therapy for prior esophagitis with either H2RAs or PPIs, at half- and full-dose strength,1 decreases the frequency of relapse (SOR: B, extrapolation from uncontrolled clinical trial).

Laparoscopic antireflux surgery for treating symptomatic GERD among elderly patients without paraesophageal hernia reduces esophageal acidity, with no apparent increase in postoperative morbidity or mortality compared with younger patients (SOR: C, nonequivalent before-after study). Upper endoscopy is recommended for elderly patients with alarm symptoms, new-onset GERD, or longstanding disease (SOR: C, expert consensus; see TABLE).

Elderly patients are at risk for more severe complications from GERD, and their relative discomfort from the disease process is often less than from comparable pathology for younger patients (SOR: C, expert consensus). Based on safety profiles and success in the general patient population, PPIs as a class are considered first-line treatment for GERD and esophagitis for the elderly (SOR: C, expert consensus).

Teasing out serious disease from routine GERD is a challenge in the elderly

Peter Danis, MD

St. John’s Mercy Medical Center, St. Louis, Mo

Who really needs the invasive workup and expensive medicine, and who needs the simple approach? Elderly patients can attribute symptoms to “just indigestion” when there are other more serious diseases present (ie, angina, severe esophagitis, stricture, cancer). The physician may need a more detailed and patient approach to get the “real” story. Lifestyle changes and over-the-counter medications will resolve the majority of GERD symptoms. If the simple things don’t work or there are warning signs/symptoms, then a further workup is needed. The older patient may then be willing to pay the cost of the long term PPI when they know that there is significant pathology and the potential for long term symptom relief.

Evidence summary

Aggregated data from 2 randomized reflux esophagitis trials conducted in the United Kingdom were analyzed with respect to patient age. Comparison of symptom relief and esophageal lesion healing showed that elderly patients treated with omeprazole (Prilosec) fared better than those treated with either cimetidine (Tagamet) or ranitidine (Zantac).2 The pooled data involved 555 patients with endoscopically proven reflux esophagitis, 154 of whom were over the age of 65. After 8 weeks, rates of esophageal healing among the elderly were 70% for those receiving omeprazole and 29% for those receiving H2RAs (41% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 26–55), while the rate of asymptomatic elderly patients was 79% for the omeprazole group and 51% for the H2RA group (28% difference; 95% CI, 12–44).3 Patients treated with omeprazole healed faster than those taking H2RAs, as shown by endoscopy, and more of them experienced symptom relief.

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial of GERD maintenance therapy started with an initial open phase in which elderly patients with GERD and documented esophagitis were treated and then had documented resolution of esophagitis by endoscopy after 6 months. The researchers then randomized 105 of these elderly patients to receive treatment with either low-dose (20 mg/d) pantoprazole or placebo for 6 months. Endoscopy was performed after 12 months for all patients, unless indicated sooner. Intention-to-treat analysis showed a disease-free rate of 79.6% (95% CI, 68.3–90.9) in the treatment group, compared with 30.4% (95% CI, 18.3–42.4) in the placebo group (number needed to treat [NNT]=2). Symptom reports concerning the same patients also suggest a marked drop in symptoms that correlated with healing.4

A prospective, nonequivalence, before-after study compared efficacy of, and complications from, laparoscopic surgery for symptomatic GERD between younger and older (≥65 years) patients. The investigators examined postoperative morbidity and mortality for 359 patients referred for laparoscopic surgery, either a partial or Nissen (full) fundoplication. They excluded those requiring more extensive surgery or repair of paraesophageal hernia. The 42 elderly patients had a higher mean American Society of Anesthesiologists score compared with the younger patients, reflecting higher preoperative comorbidity, but were similar with regard to weight and gender.

Before surgery, investigators performed 24-hour ambulatory pH monitoring. Preoperative exposure times to a pH below 4 (TpH <4) were similar for the younger and older patients (median 14.2% and 13.9%, respectively). Postoperative complication rates were similar for both groups. No deaths occurred. Minor postoperative complications involved 7% of the elderly patients and 6% of the younger group. The 24-hour pH monitoring scores showed improvement at 6 weeks after surgery for both groups, with the median TpH <4 at 1.1% (95% CL, 0.5) in the elderly vs a median of 1.8% (95% CL, 1.9) in the younger patients. At 1 year postoperatively, the values were also similar between the two groups; the median TpH <4 (95% CL) were 1.4% (1.5) in the elderly group and 1.2% (0.6) in the younger patient group.

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution, however. The study design is prone to bias, the patients had relatively low symptom scores at baseline, and sicker patients may have been excluded during the referral process.5

TABLE

Warning signs and symptoms of dyspepsia and GERD that suggest complicated disease or more serious underlying process1

| Dysphagia |

| Unexplained weight loss |

| History of gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Early satiety |

| Iron deficiency anemia |

| Vomiting |

| Odynophagia (sharp substernal pain on swallowing) |

| Initial onset of heartburn-like symptoms after the age of 50 years |

| History of immunocompromised state |

| Anorexia |

Recommendations from others

The Veterans Health Affairs/Department of Defense clinical practice guidelines recommend differentiating GERD (feelings of substernal burning associated with acid regurgitation) from dyspepsia (chronic or recurrent discomfort centered in the upper abdomen), of which GERD is a subset.6 The guidelines recommend gastroenterology consultation or upper endoscopy to rule out neoplastic or pre-neoplastic lesions if alarm symptoms (TABLE) suggesting complicated GERD are present.7

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement guidelines on dyspepsia and GERD recommend that all patients aged ≥50 years with symptoms of uncomplicated dyspepsia undergo upper endoscopy non-urgently because of the increased incidence of peptic ulcer disease, pre-neoplastic lesions, malignancy, and increased morbidity out of proportion to symptoms that are more common in an older patient population. The guidelines also recommend endoscopy for patients aged ≥50 years with uncomplicated GERD and the presence of symptoms for greater than 10 years because of the increased risk of pre-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions, including Barrett’s esophagus.8

1. Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Leandro G, et al. Long-term clinical outcome of elderly patients with reflux esophagitis: a six-month to three-year follow-up study. Am J Ther 2002;9:295-300.

2. James OF, Parry-Billings K. Comparison of omeprazole and histamine H2–receptor antagonists in the treatment of elderly and young patients with reflux oesophagitis. Age Aging 1994;23:121-126.

3. Omeprazole was better than H2-antagonists in reflux esophagitis. ACP Journal Club 1994;121:65.-

4. Pilotto A, Leandro G, Franceschi M. Short and long term therapy for reflux oesophagitis in the elderly: a multicentre, placebo-controlled study with pantoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:1399-1406.

5. Trus TL, Laycock WS, Wo JM, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery in the elderly. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:351-353.

6. Bazaldua OV, Schneider FD. Evaluation and management of dyspepsia. Am Fam Physician 1999;60:1773-1784.

7. VHA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adults with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Primary Care Practice. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration, Department of Defense; 2003 March 12. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=5188&nbr=3570#s25. Accessed on February 9, 2006.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Dyspepsia and GERD. Bloomington, Minn: ICSI Guidelines; July 2004. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=5624. Accessed on February 9, 2006.

No evidence supports one method over another in managing uncomplicated gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for patients aged >65 years. For those with endoscopically documented esophagitis, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) relieve symptoms faster than histamine H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, extrapolation from randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). Treating elderly patients with pantoprazole (Protonix) after resolution of acute esophagitis results in fewer relapses than with placebo (SOR: B, double-blind RCT). Limited evidence suggests that such maintenance therapy for prior esophagitis with either H2RAs or PPIs, at half- and full-dose strength,1 decreases the frequency of relapse (SOR: B, extrapolation from uncontrolled clinical trial).

Laparoscopic antireflux surgery for treating symptomatic GERD among elderly patients without paraesophageal hernia reduces esophageal acidity, with no apparent increase in postoperative morbidity or mortality compared with younger patients (SOR: C, nonequivalent before-after study). Upper endoscopy is recommended for elderly patients with alarm symptoms, new-onset GERD, or longstanding disease (SOR: C, expert consensus; see TABLE).

Elderly patients are at risk for more severe complications from GERD, and their relative discomfort from the disease process is often less than from comparable pathology for younger patients (SOR: C, expert consensus). Based on safety profiles and success in the general patient population, PPIs as a class are considered first-line treatment for GERD and esophagitis for the elderly (SOR: C, expert consensus).

Teasing out serious disease from routine GERD is a challenge in the elderly

Peter Danis, MD

St. John’s Mercy Medical Center, St. Louis, Mo

Who really needs the invasive workup and expensive medicine, and who needs the simple approach? Elderly patients can attribute symptoms to “just indigestion” when there are other more serious diseases present (ie, angina, severe esophagitis, stricture, cancer). The physician may need a more detailed and patient approach to get the “real” story. Lifestyle changes and over-the-counter medications will resolve the majority of GERD symptoms. If the simple things don’t work or there are warning signs/symptoms, then a further workup is needed. The older patient may then be willing to pay the cost of the long term PPI when they know that there is significant pathology and the potential for long term symptom relief.

Evidence summary

Aggregated data from 2 randomized reflux esophagitis trials conducted in the United Kingdom were analyzed with respect to patient age. Comparison of symptom relief and esophageal lesion healing showed that elderly patients treated with omeprazole (Prilosec) fared better than those treated with either cimetidine (Tagamet) or ranitidine (Zantac).2 The pooled data involved 555 patients with endoscopically proven reflux esophagitis, 154 of whom were over the age of 65. After 8 weeks, rates of esophageal healing among the elderly were 70% for those receiving omeprazole and 29% for those receiving H2RAs (41% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 26–55), while the rate of asymptomatic elderly patients was 79% for the omeprazole group and 51% for the H2RA group (28% difference; 95% CI, 12–44).3 Patients treated with omeprazole healed faster than those taking H2RAs, as shown by endoscopy, and more of them experienced symptom relief.

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial of GERD maintenance therapy started with an initial open phase in which elderly patients with GERD and documented esophagitis were treated and then had documented resolution of esophagitis by endoscopy after 6 months. The researchers then randomized 105 of these elderly patients to receive treatment with either low-dose (20 mg/d) pantoprazole or placebo for 6 months. Endoscopy was performed after 12 months for all patients, unless indicated sooner. Intention-to-treat analysis showed a disease-free rate of 79.6% (95% CI, 68.3–90.9) in the treatment group, compared with 30.4% (95% CI, 18.3–42.4) in the placebo group (number needed to treat [NNT]=2). Symptom reports concerning the same patients also suggest a marked drop in symptoms that correlated with healing.4

A prospective, nonequivalence, before-after study compared efficacy of, and complications from, laparoscopic surgery for symptomatic GERD between younger and older (≥65 years) patients. The investigators examined postoperative morbidity and mortality for 359 patients referred for laparoscopic surgery, either a partial or Nissen (full) fundoplication. They excluded those requiring more extensive surgery or repair of paraesophageal hernia. The 42 elderly patients had a higher mean American Society of Anesthesiologists score compared with the younger patients, reflecting higher preoperative comorbidity, but were similar with regard to weight and gender.

Before surgery, investigators performed 24-hour ambulatory pH monitoring. Preoperative exposure times to a pH below 4 (TpH <4) were similar for the younger and older patients (median 14.2% and 13.9%, respectively). Postoperative complication rates were similar for both groups. No deaths occurred. Minor postoperative complications involved 7% of the elderly patients and 6% of the younger group. The 24-hour pH monitoring scores showed improvement at 6 weeks after surgery for both groups, with the median TpH <4 at 1.1% (95% CL, 0.5) in the elderly vs a median of 1.8% (95% CL, 1.9) in the younger patients. At 1 year postoperatively, the values were also similar between the two groups; the median TpH <4 (95% CL) were 1.4% (1.5) in the elderly group and 1.2% (0.6) in the younger patient group.

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution, however. The study design is prone to bias, the patients had relatively low symptom scores at baseline, and sicker patients may have been excluded during the referral process.5

TABLE

Warning signs and symptoms of dyspepsia and GERD that suggest complicated disease or more serious underlying process1

| Dysphagia |

| Unexplained weight loss |

| History of gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Early satiety |

| Iron deficiency anemia |

| Vomiting |

| Odynophagia (sharp substernal pain on swallowing) |

| Initial onset of heartburn-like symptoms after the age of 50 years |

| History of immunocompromised state |

| Anorexia |

Recommendations from others

The Veterans Health Affairs/Department of Defense clinical practice guidelines recommend differentiating GERD (feelings of substernal burning associated with acid regurgitation) from dyspepsia (chronic or recurrent discomfort centered in the upper abdomen), of which GERD is a subset.6 The guidelines recommend gastroenterology consultation or upper endoscopy to rule out neoplastic or pre-neoplastic lesions if alarm symptoms (TABLE) suggesting complicated GERD are present.7

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement guidelines on dyspepsia and GERD recommend that all patients aged ≥50 years with symptoms of uncomplicated dyspepsia undergo upper endoscopy non-urgently because of the increased incidence of peptic ulcer disease, pre-neoplastic lesions, malignancy, and increased morbidity out of proportion to symptoms that are more common in an older patient population. The guidelines also recommend endoscopy for patients aged ≥50 years with uncomplicated GERD and the presence of symptoms for greater than 10 years because of the increased risk of pre-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions, including Barrett’s esophagus.8

No evidence supports one method over another in managing uncomplicated gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) for patients aged >65 years. For those with endoscopically documented esophagitis, proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) relieve symptoms faster than histamine H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, extrapolation from randomized controlled trials [RCTs]). Treating elderly patients with pantoprazole (Protonix) after resolution of acute esophagitis results in fewer relapses than with placebo (SOR: B, double-blind RCT). Limited evidence suggests that such maintenance therapy for prior esophagitis with either H2RAs or PPIs, at half- and full-dose strength,1 decreases the frequency of relapse (SOR: B, extrapolation from uncontrolled clinical trial).

Laparoscopic antireflux surgery for treating symptomatic GERD among elderly patients without paraesophageal hernia reduces esophageal acidity, with no apparent increase in postoperative morbidity or mortality compared with younger patients (SOR: C, nonequivalent before-after study). Upper endoscopy is recommended for elderly patients with alarm symptoms, new-onset GERD, or longstanding disease (SOR: C, expert consensus; see TABLE).

Elderly patients are at risk for more severe complications from GERD, and their relative discomfort from the disease process is often less than from comparable pathology for younger patients (SOR: C, expert consensus). Based on safety profiles and success in the general patient population, PPIs as a class are considered first-line treatment for GERD and esophagitis for the elderly (SOR: C, expert consensus).

Teasing out serious disease from routine GERD is a challenge in the elderly

Peter Danis, MD

St. John’s Mercy Medical Center, St. Louis, Mo

Who really needs the invasive workup and expensive medicine, and who needs the simple approach? Elderly patients can attribute symptoms to “just indigestion” when there are other more serious diseases present (ie, angina, severe esophagitis, stricture, cancer). The physician may need a more detailed and patient approach to get the “real” story. Lifestyle changes and over-the-counter medications will resolve the majority of GERD symptoms. If the simple things don’t work or there are warning signs/symptoms, then a further workup is needed. The older patient may then be willing to pay the cost of the long term PPI when they know that there is significant pathology and the potential for long term symptom relief.

Evidence summary

Aggregated data from 2 randomized reflux esophagitis trials conducted in the United Kingdom were analyzed with respect to patient age. Comparison of symptom relief and esophageal lesion healing showed that elderly patients treated with omeprazole (Prilosec) fared better than those treated with either cimetidine (Tagamet) or ranitidine (Zantac).2 The pooled data involved 555 patients with endoscopically proven reflux esophagitis, 154 of whom were over the age of 65. After 8 weeks, rates of esophageal healing among the elderly were 70% for those receiving omeprazole and 29% for those receiving H2RAs (41% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 26–55), while the rate of asymptomatic elderly patients was 79% for the omeprazole group and 51% for the H2RA group (28% difference; 95% CI, 12–44).3 Patients treated with omeprazole healed faster than those taking H2RAs, as shown by endoscopy, and more of them experienced symptom relief.

A multicenter, randomized, double-blind trial of GERD maintenance therapy started with an initial open phase in which elderly patients with GERD and documented esophagitis were treated and then had documented resolution of esophagitis by endoscopy after 6 months. The researchers then randomized 105 of these elderly patients to receive treatment with either low-dose (20 mg/d) pantoprazole or placebo for 6 months. Endoscopy was performed after 12 months for all patients, unless indicated sooner. Intention-to-treat analysis showed a disease-free rate of 79.6% (95% CI, 68.3–90.9) in the treatment group, compared with 30.4% (95% CI, 18.3–42.4) in the placebo group (number needed to treat [NNT]=2). Symptom reports concerning the same patients also suggest a marked drop in symptoms that correlated with healing.4

A prospective, nonequivalence, before-after study compared efficacy of, and complications from, laparoscopic surgery for symptomatic GERD between younger and older (≥65 years) patients. The investigators examined postoperative morbidity and mortality for 359 patients referred for laparoscopic surgery, either a partial or Nissen (full) fundoplication. They excluded those requiring more extensive surgery or repair of paraesophageal hernia. The 42 elderly patients had a higher mean American Society of Anesthesiologists score compared with the younger patients, reflecting higher preoperative comorbidity, but were similar with regard to weight and gender.

Before surgery, investigators performed 24-hour ambulatory pH monitoring. Preoperative exposure times to a pH below 4 (TpH <4) were similar for the younger and older patients (median 14.2% and 13.9%, respectively). Postoperative complication rates were similar for both groups. No deaths occurred. Minor postoperative complications involved 7% of the elderly patients and 6% of the younger group. The 24-hour pH monitoring scores showed improvement at 6 weeks after surgery for both groups, with the median TpH <4 at 1.1% (95% CL, 0.5) in the elderly vs a median of 1.8% (95% CL, 1.9) in the younger patients. At 1 year postoperatively, the values were also similar between the two groups; the median TpH <4 (95% CL) were 1.4% (1.5) in the elderly group and 1.2% (0.6) in the younger patient group.

The results of this study should be interpreted with caution, however. The study design is prone to bias, the patients had relatively low symptom scores at baseline, and sicker patients may have been excluded during the referral process.5

TABLE

Warning signs and symptoms of dyspepsia and GERD that suggest complicated disease or more serious underlying process1

| Dysphagia |

| Unexplained weight loss |

| History of gastrointestinal bleeding |

| Early satiety |

| Iron deficiency anemia |

| Vomiting |

| Odynophagia (sharp substernal pain on swallowing) |

| Initial onset of heartburn-like symptoms after the age of 50 years |

| History of immunocompromised state |

| Anorexia |

Recommendations from others

The Veterans Health Affairs/Department of Defense clinical practice guidelines recommend differentiating GERD (feelings of substernal burning associated with acid regurgitation) from dyspepsia (chronic or recurrent discomfort centered in the upper abdomen), of which GERD is a subset.6 The guidelines recommend gastroenterology consultation or upper endoscopy to rule out neoplastic or pre-neoplastic lesions if alarm symptoms (TABLE) suggesting complicated GERD are present.7

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement guidelines on dyspepsia and GERD recommend that all patients aged ≥50 years with symptoms of uncomplicated dyspepsia undergo upper endoscopy non-urgently because of the increased incidence of peptic ulcer disease, pre-neoplastic lesions, malignancy, and increased morbidity out of proportion to symptoms that are more common in an older patient population. The guidelines also recommend endoscopy for patients aged ≥50 years with uncomplicated GERD and the presence of symptoms for greater than 10 years because of the increased risk of pre-neoplastic and neoplastic lesions, including Barrett’s esophagus.8

1. Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Leandro G, et al. Long-term clinical outcome of elderly patients with reflux esophagitis: a six-month to three-year follow-up study. Am J Ther 2002;9:295-300.

2. James OF, Parry-Billings K. Comparison of omeprazole and histamine H2–receptor antagonists in the treatment of elderly and young patients with reflux oesophagitis. Age Aging 1994;23:121-126.

3. Omeprazole was better than H2-antagonists in reflux esophagitis. ACP Journal Club 1994;121:65.-

4. Pilotto A, Leandro G, Franceschi M. Short and long term therapy for reflux oesophagitis in the elderly: a multicentre, placebo-controlled study with pantoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:1399-1406.

5. Trus TL, Laycock WS, Wo JM, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery in the elderly. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:351-353.

6. Bazaldua OV, Schneider FD. Evaluation and management of dyspepsia. Am Fam Physician 1999;60:1773-1784.

7. VHA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adults with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Primary Care Practice. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration, Department of Defense; 2003 March 12. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=5188&nbr=3570#s25. Accessed on February 9, 2006.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Dyspepsia and GERD. Bloomington, Minn: ICSI Guidelines; July 2004. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=5624. Accessed on February 9, 2006.

1. Pilotto A, Franceschi M, Leandro G, et al. Long-term clinical outcome of elderly patients with reflux esophagitis: a six-month to three-year follow-up study. Am J Ther 2002;9:295-300.

2. James OF, Parry-Billings K. Comparison of omeprazole and histamine H2–receptor antagonists in the treatment of elderly and young patients with reflux oesophagitis. Age Aging 1994;23:121-126.

3. Omeprazole was better than H2-antagonists in reflux esophagitis. ACP Journal Club 1994;121:65.-

4. Pilotto A, Leandro G, Franceschi M. Short and long term therapy for reflux oesophagitis in the elderly: a multicentre, placebo-controlled study with pantoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17:1399-1406.

5. Trus TL, Laycock WS, Wo JM, et al. Laparoscopic antireflux surgery in the elderly. Am J Gastroenterol 1998;93:351-353.

6. Bazaldua OV, Schneider FD. Evaluation and management of dyspepsia. Am Fam Physician 1999;60:1773-1784.

7. VHA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Adults with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Primary Care Practice. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration, Department of Defense; 2003 March 12. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?ss=15&doc_id=5188&nbr=3570#s25. Accessed on February 9, 2006.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement (ICSI). Dyspepsia and GERD. Bloomington, Minn: ICSI Guidelines; July 2004. Available at: www.guideline.gov/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=5624. Accessed on February 9, 2006.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network