User login

Breast calcifications mimicking pulmonary nodules

On examination, her lung fields were clear, with no audible murmurs, and she had no lower-extremity edema. Her oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

BREAST CALCIFICATIONS CAN MIMIC PULMONARY NODULES

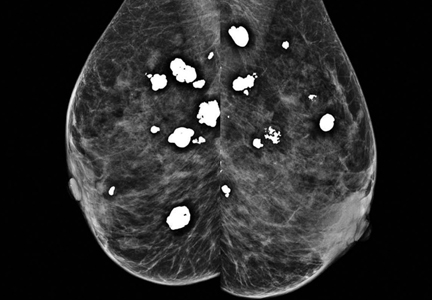

Diffuse bilateral calcifications on mammography are typically benign and represent either dermal calcification (spherical lucent- centered calcification that develops from a degenerative metaplastic process) or fibrocystic changes.1 Up to 10% of women have fibroadenomas, and 19% of fibroadenomas have microcalcifications.2–4 Therefore, given the high prevalence, calcified breast masses should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating initial chest radiographs in women.

Calcifications in the breast can overlie the lung fields and mimic pulmonary nodules. When assessing pulmonary nodules, prior imaging of the chest should always be assessed if available to determine if a lesion is new or has remained stable.

Given our patient’s age and 35-pack-year history of smoking, apparent pulmonary lesions caused concern and prompted chest CT to clarify the diagnosis. However, if the patient has no risk factors for lung malignancy, it can be safe to proceed with mammography.

By including breast calcifications in the differential diagnosis of apparent pulmonary nodules on chest radiography, the clinician can approach the case differently and inquire about a history of fibroadenomas and prior mammograms before pursuing a further workup. This can avoid unnecessary radiation exposure, the costs of CT, and apprehension in the patient raised by unwarranted concern for malignancy.

- Sitzman SB. A useful sign for distinguishing clustered skin calcifications from calcifications within the breast on mammograms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158:1407–1408.

- Anastassiades OT, Bouropoulou V, Kontogeorgos G, Rachmanides M, Gogas I. Microcalcifications in benign breast diseases. A histological and histochemical study. Pathol Res Pract 1984; 178:237–242.

- Millis RR, Davis R, Stacey AJ. The detection and significance of calcifications in the breast: a radiological and pathological study. Br J Radiol 1976; 49:12–26.

- Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:275–285.

On examination, her lung fields were clear, with no audible murmurs, and she had no lower-extremity edema. Her oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

BREAST CALCIFICATIONS CAN MIMIC PULMONARY NODULES

Diffuse bilateral calcifications on mammography are typically benign and represent either dermal calcification (spherical lucent- centered calcification that develops from a degenerative metaplastic process) or fibrocystic changes.1 Up to 10% of women have fibroadenomas, and 19% of fibroadenomas have microcalcifications.2–4 Therefore, given the high prevalence, calcified breast masses should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating initial chest radiographs in women.

Calcifications in the breast can overlie the lung fields and mimic pulmonary nodules. When assessing pulmonary nodules, prior imaging of the chest should always be assessed if available to determine if a lesion is new or has remained stable.

Given our patient’s age and 35-pack-year history of smoking, apparent pulmonary lesions caused concern and prompted chest CT to clarify the diagnosis. However, if the patient has no risk factors for lung malignancy, it can be safe to proceed with mammography.

By including breast calcifications in the differential diagnosis of apparent pulmonary nodules on chest radiography, the clinician can approach the case differently and inquire about a history of fibroadenomas and prior mammograms before pursuing a further workup. This can avoid unnecessary radiation exposure, the costs of CT, and apprehension in the patient raised by unwarranted concern for malignancy.

On examination, her lung fields were clear, with no audible murmurs, and she had no lower-extremity edema. Her oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

BREAST CALCIFICATIONS CAN MIMIC PULMONARY NODULES

Diffuse bilateral calcifications on mammography are typically benign and represent either dermal calcification (spherical lucent- centered calcification that develops from a degenerative metaplastic process) or fibrocystic changes.1 Up to 10% of women have fibroadenomas, and 19% of fibroadenomas have microcalcifications.2–4 Therefore, given the high prevalence, calcified breast masses should be considered in the differential diagnosis when evaluating initial chest radiographs in women.

Calcifications in the breast can overlie the lung fields and mimic pulmonary nodules. When assessing pulmonary nodules, prior imaging of the chest should always be assessed if available to determine if a lesion is new or has remained stable.

Given our patient’s age and 35-pack-year history of smoking, apparent pulmonary lesions caused concern and prompted chest CT to clarify the diagnosis. However, if the patient has no risk factors for lung malignancy, it can be safe to proceed with mammography.

By including breast calcifications in the differential diagnosis of apparent pulmonary nodules on chest radiography, the clinician can approach the case differently and inquire about a history of fibroadenomas and prior mammograms before pursuing a further workup. This can avoid unnecessary radiation exposure, the costs of CT, and apprehension in the patient raised by unwarranted concern for malignancy.

- Sitzman SB. A useful sign for distinguishing clustered skin calcifications from calcifications within the breast on mammograms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158:1407–1408.

- Anastassiades OT, Bouropoulou V, Kontogeorgos G, Rachmanides M, Gogas I. Microcalcifications in benign breast diseases. A histological and histochemical study. Pathol Res Pract 1984; 178:237–242.

- Millis RR, Davis R, Stacey AJ. The detection and significance of calcifications in the breast: a radiological and pathological study. Br J Radiol 1976; 49:12–26.

- Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:275–285.

- Sitzman SB. A useful sign for distinguishing clustered skin calcifications from calcifications within the breast on mammograms. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1992; 158:1407–1408.

- Anastassiades OT, Bouropoulou V, Kontogeorgos G, Rachmanides M, Gogas I. Microcalcifications in benign breast diseases. A histological and histochemical study. Pathol Res Pract 1984; 178:237–242.

- Millis RR, Davis R, Stacey AJ. The detection and significance of calcifications in the breast: a radiological and pathological study. Br J Radiol 1976; 49:12–26.

- Santen RJ, Mansel R. Benign breast disorders. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:275–285.

An abnormal peripheral blood smear and altered mental status

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation on anticoagulation was brought to the emergency department by her husband after 1 day of altered mental status with acute onset. Her husband reported that she had been minimally arousable, and the physical examination revealed that she was stuporous and withdrew extremities only from noxious stimuli.

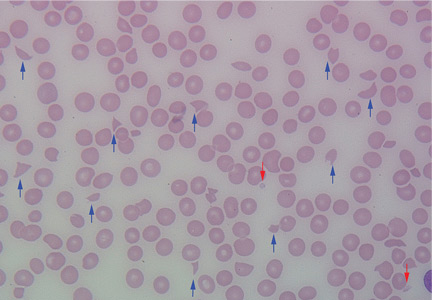

Results of initial laboratory tests revealed a creatinine level of 2.4 mg/dL (reference range 0.7–1.4), hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL (12–16), platelet count 16 × 109/L (150–400), white blood cell count of 7.7 × 109/L (3.7–11), and international normalized ratio of 2.1. A peripheral blood smear is shown in Figure 1.

Computed tomography showed evidence of chronic small vascular ischemia. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed numerous foci of restricted diffusion within the supratentorial and infratentorial areas, suggesting microembolic phenomena.

The peripheral blood smear was compatible with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, which can occur in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome, malignant hypertension, scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, eclampsia, renal allograft rejection, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and severe sepsis.1,2

In addition to hemolytic anemia, the patient also had neurologic abnormalities, renal involvement, and thrombocytopenia. The hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia were sufficient to raise our suspicion of TTP and to consider initiation of plasma exchange. Only 5% of patients with TTP demonstrate the classic pentad of clinical features,1 ie, thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, fluctuating neurologic signs, renal impairment, and fever.

In 1991, when plasma exchange was introduced for TTP, the survival rate of patients increased from 10% to 78%.1,3 Thus, the diagnosis of TTP is an urgent indication for plasma exchange. We normally do plasma exchange daily until the platelet levels improve.

Our patient received methylprednisone 125 mg intravenously every 12 hours and plasma exchange daily. After three cycles of plasma exchange, she regained normal consciousness, and her platelet count had increased to 20.5 × 109/L on the day of discharge from our hospital.

TTP is a life-threatening hematologic disorder. Evidence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia on a peripheral blood smear is vital to the suspicion of TTP. The diagnosis should be confirmed by ADAMTS13 testing, which should show decreased activity (< 10%) or increased inhibition, or both. Rapid management with plasma exchange and steroids can lead to a satisfactory outcome.

Acknowledgment: We are particularly grateful to Dr. Vivian Arguello (Director of Flow Cytometry, Department of Pathology, Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia) for her kind support with the blood smear image.

- George JN. How I treat patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: 2010. Blood 2010; 116:4060–4069.

- Sadler JE. Von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS13, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 2008; 112:11–18.

- Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 1991; 325:393–397.

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation on anticoagulation was brought to the emergency department by her husband after 1 day of altered mental status with acute onset. Her husband reported that she had been minimally arousable, and the physical examination revealed that she was stuporous and withdrew extremities only from noxious stimuli.

Results of initial laboratory tests revealed a creatinine level of 2.4 mg/dL (reference range 0.7–1.4), hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL (12–16), platelet count 16 × 109/L (150–400), white blood cell count of 7.7 × 109/L (3.7–11), and international normalized ratio of 2.1. A peripheral blood smear is shown in Figure 1.

Computed tomography showed evidence of chronic small vascular ischemia. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed numerous foci of restricted diffusion within the supratentorial and infratentorial areas, suggesting microembolic phenomena.

The peripheral blood smear was compatible with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, which can occur in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome, malignant hypertension, scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, eclampsia, renal allograft rejection, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and severe sepsis.1,2

In addition to hemolytic anemia, the patient also had neurologic abnormalities, renal involvement, and thrombocytopenia. The hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia were sufficient to raise our suspicion of TTP and to consider initiation of plasma exchange. Only 5% of patients with TTP demonstrate the classic pentad of clinical features,1 ie, thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, fluctuating neurologic signs, renal impairment, and fever.

In 1991, when plasma exchange was introduced for TTP, the survival rate of patients increased from 10% to 78%.1,3 Thus, the diagnosis of TTP is an urgent indication for plasma exchange. We normally do plasma exchange daily until the platelet levels improve.

Our patient received methylprednisone 125 mg intravenously every 12 hours and plasma exchange daily. After three cycles of plasma exchange, she regained normal consciousness, and her platelet count had increased to 20.5 × 109/L on the day of discharge from our hospital.

TTP is a life-threatening hematologic disorder. Evidence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia on a peripheral blood smear is vital to the suspicion of TTP. The diagnosis should be confirmed by ADAMTS13 testing, which should show decreased activity (< 10%) or increased inhibition, or both. Rapid management with plasma exchange and steroids can lead to a satisfactory outcome.

Acknowledgment: We are particularly grateful to Dr. Vivian Arguello (Director of Flow Cytometry, Department of Pathology, Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia) for her kind support with the blood smear image.

A 72-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation on anticoagulation was brought to the emergency department by her husband after 1 day of altered mental status with acute onset. Her husband reported that she had been minimally arousable, and the physical examination revealed that she was stuporous and withdrew extremities only from noxious stimuli.

Results of initial laboratory tests revealed a creatinine level of 2.4 mg/dL (reference range 0.7–1.4), hemoglobin 12.1 g/dL (12–16), platelet count 16 × 109/L (150–400), white blood cell count of 7.7 × 109/L (3.7–11), and international normalized ratio of 2.1. A peripheral blood smear is shown in Figure 1.

Computed tomography showed evidence of chronic small vascular ischemia. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed numerous foci of restricted diffusion within the supratentorial and infratentorial areas, suggesting microembolic phenomena.

The peripheral blood smear was compatible with microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, which can occur in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome, malignant hypertension, scleroderma, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, eclampsia, renal allograft rejection, hematopoietic stem cell transplant, and severe sepsis.1,2

In addition to hemolytic anemia, the patient also had neurologic abnormalities, renal involvement, and thrombocytopenia. The hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia were sufficient to raise our suspicion of TTP and to consider initiation of plasma exchange. Only 5% of patients with TTP demonstrate the classic pentad of clinical features,1 ie, thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, fluctuating neurologic signs, renal impairment, and fever.

In 1991, when plasma exchange was introduced for TTP, the survival rate of patients increased from 10% to 78%.1,3 Thus, the diagnosis of TTP is an urgent indication for plasma exchange. We normally do plasma exchange daily until the platelet levels improve.

Our patient received methylprednisone 125 mg intravenously every 12 hours and plasma exchange daily. After three cycles of plasma exchange, she regained normal consciousness, and her platelet count had increased to 20.5 × 109/L on the day of discharge from our hospital.

TTP is a life-threatening hematologic disorder. Evidence of microangiopathic hemolytic anemia on a peripheral blood smear is vital to the suspicion of TTP. The diagnosis should be confirmed by ADAMTS13 testing, which should show decreased activity (< 10%) or increased inhibition, or both. Rapid management with plasma exchange and steroids can lead to a satisfactory outcome.

Acknowledgment: We are particularly grateful to Dr. Vivian Arguello (Director of Flow Cytometry, Department of Pathology, Einstein Medical Center, Philadelphia) for her kind support with the blood smear image.

- George JN. How I treat patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: 2010. Blood 2010; 116:4060–4069.

- Sadler JE. Von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS13, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 2008; 112:11–18.

- Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 1991; 325:393–397.

- George JN. How I treat patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: 2010. Blood 2010; 116:4060–4069.

- Sadler JE. Von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS13, and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Blood 2008; 112:11–18.

- Rock GA, Shumak KH, Buskard NA, et al. Comparison of plasma exchange with plasma infusion in the treatment of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med 1991; 325:393–397.