User login

Strategies of Female Teaching Attending Physicians to Navigate Gender-Based Challenges: An Exploratory Qualitative Study

The demographic composition of physicians has shifted dramatically in the last five decades. The number of women matriculating into medical school rose from 6% in the 1960s1 to 52% in 20192; women accounted for 39% of full-time faculty in 2015.3 Despite this evolution of the physician gender array, many challenges remain.4 Women represented only 35% of all associate professors and 22% of full professors in 2015.3 Women experience gender-based discrimination, hostility, and unconscious bias as medical trainees5-9 and as attending physicians10-13 with significant deleterious effects including burnout and suicidal thoughts.14 While types of gender-based challenges are well described in the literature, strategies to navigate and respond to these challenges are less understood.

The approaches and techniques of exemplary teaching attending physicians (hereafter referred to as “attendings”) have previously been reported from groups of predominantly male attendings.15-18 Because of gender-based challenges female physicians face that lead them to reduce their effort or leave the medical field,19 there is concern that prior scholarship in effective teaching may not adequately capture the approaches and techniques of female attendings. To our knowledge, no studies have specifically examined female attendings. Therefore, we sought to explore the lived experiences of six female attendings with particular emphasis on how they navigate and respond to gender-based challenges in clinical environments.

METHODS

Study Design and Sampling

This was a multisite study using an exploratory qualitative approach to inquiry. We aimed to examine techniques, approaches, and attitudes of outstanding general medicine teaching attendings among groups previously not well represented (ie, women and self-identified underrepresented minorities [URMs] in medicine). URM was defined by the Association of American Medical Colleges as “those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population.”20 A modified snowball sampling approach21 was employed to identify attendings as delineated below.

To maintain quality while guaranteeing diversity in geography and population, potential institutions in which to observe attendings were determined by first creating the following lists: The top 20 hospitals in the U.S. News & World Report’s 2017-2018 Best Hospitals Honor Roll,22 top-rated institutions by Doximity in each geographic region and among rural training sites,23 and four historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) with medical schools. Institutions visited during a previous similar study16 were excluded. Next, the list was narrowed to 25 by randomly selecting five in each main geographic region and five rural institutions. These were combined with all four HBCUs to create a final list of 29 institutions.

Next, division of hospital medicine chiefs (and/or general medicine chiefs) and internal medicine residency directors at each of these 29 institutions were asked to nominate exemplary attendings, particularly those who identified as women and URMs. Twelve attendings who were themselves observed in a previous study16 were also asked for nominations. Finally, recommendations were sought from leaders of relevant American Medical Association member groups.24

Using this sampling method, 43 physicians were identified. An internet search was conducted to identify individual characteristics including medical education, training, clinical and research interests, and educational awards. These characteristics were considered and discussed by the research team. Preference was given to those attendings nominated by more than one individual (n = 3), those who had received teaching awards, and those with interests involving women in medicine. Research team members narrowed the list to seven attendings who were contacted via email and invited to participate. One did not respond, while six agreed to participate. The six attendings identified current team members who would be rounding on the visit date. Attendings were asked to recommend 6-10 former learners; we contacted these former learners and invited them to participate. Former learners were included to understand lasting effects from their attendings.

Data Collection

Observations

All 1-day site visits were conducted by two research team members, a physician (NH) and a qualitative research specialist (MQ). In four visits, an additional author accompanied the research team. In order to ensure consistency and diversity in perspectives, all authors attended at least one visit. These occurred between April 16 and August 28, 2018. Each visit began with direct observation of attendings (n = 6) and current learners (n = 24) during inpatient general medicine teaching rounds. Each researcher unobtrusively recorded their observations via handwritten, open field notes, paying particular attention to group interactions, teaching approach, conversations within and peripheral to the team, and patient–team interactions. After each visit, researchers met to compare and combine field notes.

Interviews and Focus Groups

Researchers then conducted individual, semistructured interviews with attendings and focus groups with current (n = 21) and former (n = 17) learners. Focus groups with learners varied in size from two to five participants. Former learners were occasionally not available for on-site focus groups and were interviewed separately by telephone after the visit. The interview guide for attendings (Appendix 1) was adapted from the prior study16 but expanded with questions related to experiences, challenges, and approaches of female and URM physicians. A separate guide was used to facilitate focus groups with learners (Appendix 1

This study was determined to be exempt by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All participants were informed that their participation was completely voluntary and that they could terminate their involvement at any time.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a content analysis approach.25 Inductive coding was used to identify codes derived from the data. Two team members (MQ and MH) independently coded the first transcript to develop a codebook, then met to compare and discuss codes. Codes and definitions were entered into the codebook. These team members continued coding five additional transcripts, meeting to compare codes, discussing any discrepancies until agreement was reached, adding new codes identified, and ensuring consistent code application. They reviewed prior transcripts and recoded if necessary. Once no new codes were identified, one team member coded the remaining transcripts. The same codebook was used to code field note documents using the same iterative process. After all qualitative data were coded and verified, they were entered into NVivo 10. Code reports were generated and reviewed by three team members to identify themes and check for coding consistency.

Role of the Funding Source

This study received no external funding.

RESULTS

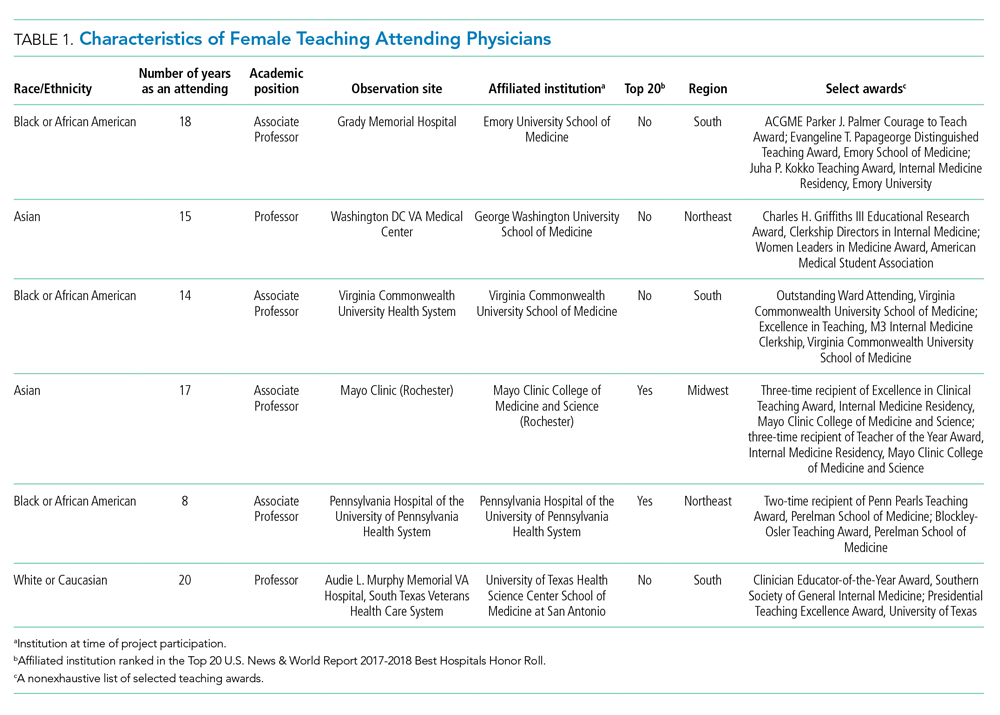

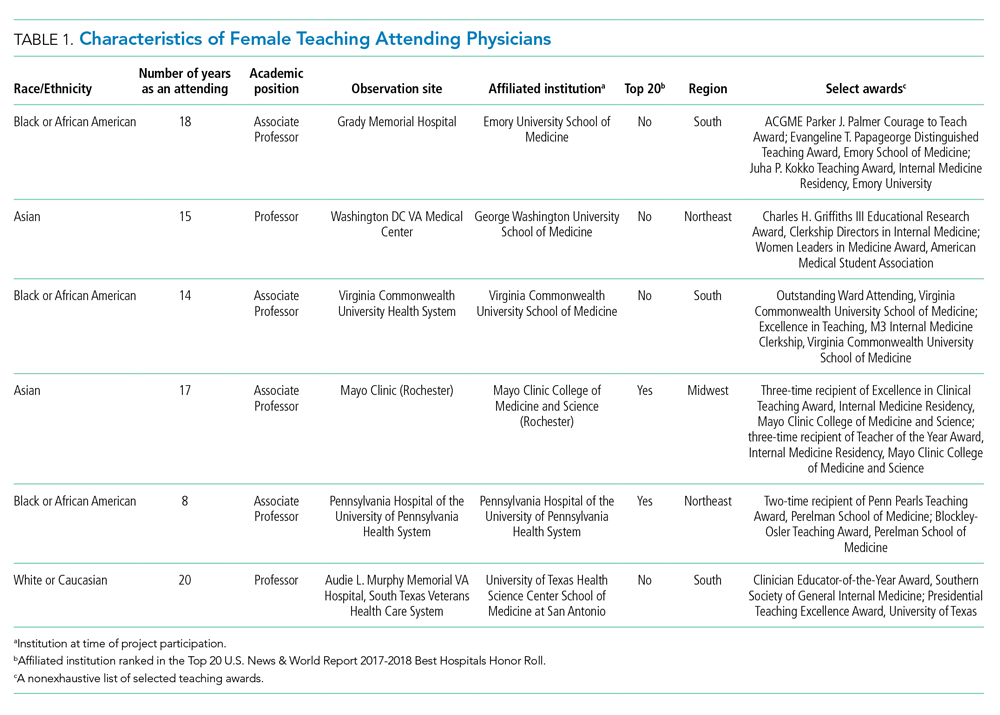

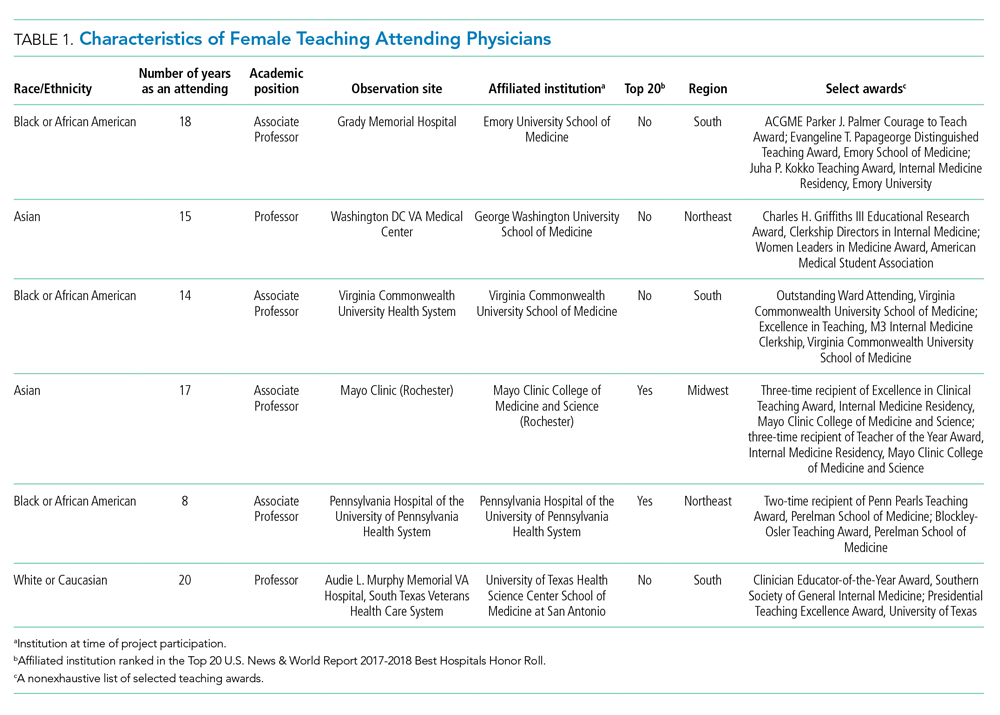

We examined six exemplary attendings through direct observation of rounds and individual interviews. We also discussed these attendings with 21 current learners and 17 former learners (Appendix 2). All attendings self-identified as female. The group was diverse in terms of race/ethnicity, with three identifying as Black or African American, two as Asian, and one as White or Caucasian. Levels of experience as an attending ranged from 8 to 20 years (mean, 15.3 years). At the time of observation, two were professors and four were associate professors. The group included all three attendings who had been nominated by more than one individual, and all six had won multiple teaching awards. The observation sites represented several areas of the United States (Table 1).

The coded interview data and field notes were categorized into three broad overlapping themes based on strategies our attendings used to respond to gender-based challenges. The following sections describe types of challenges faced by female attendings along with specific strategies they employed to actively position themselves as physician team leaders, manage gender-based stereotypes and perceptions, and identify and embrace their unique qualities. Illustrative quotations or observations that further elucidate meaning are provided.

Female Attendings Actively Position Themselves as Physician Team Leaders

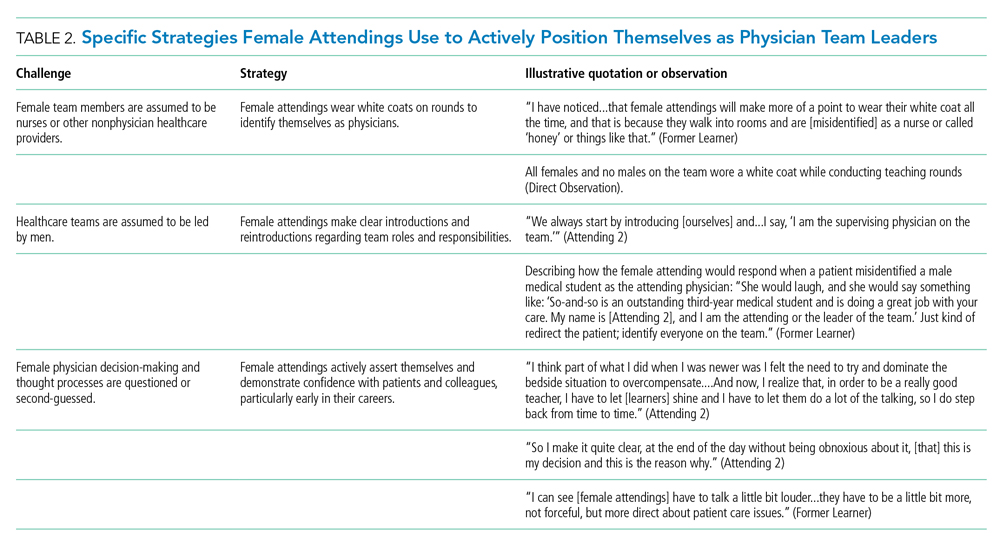

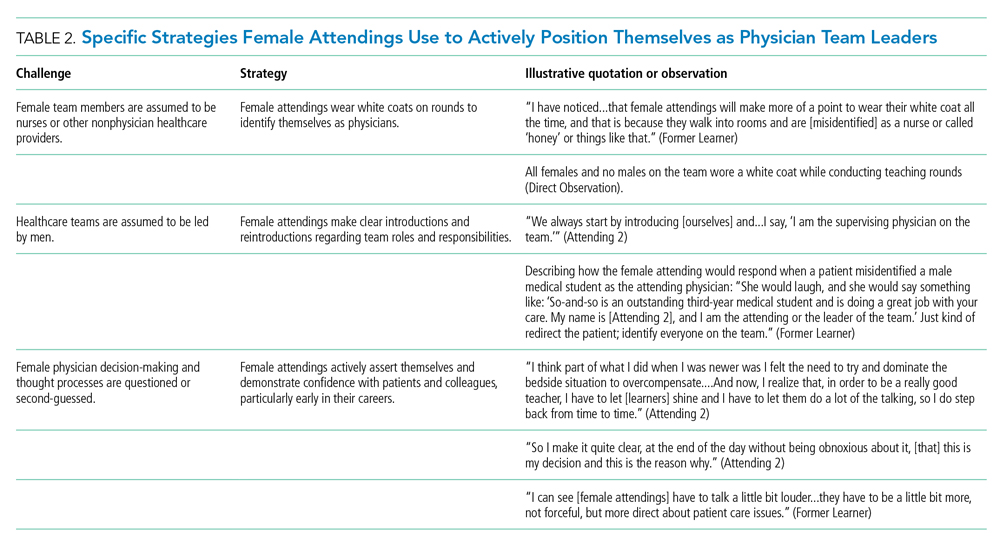

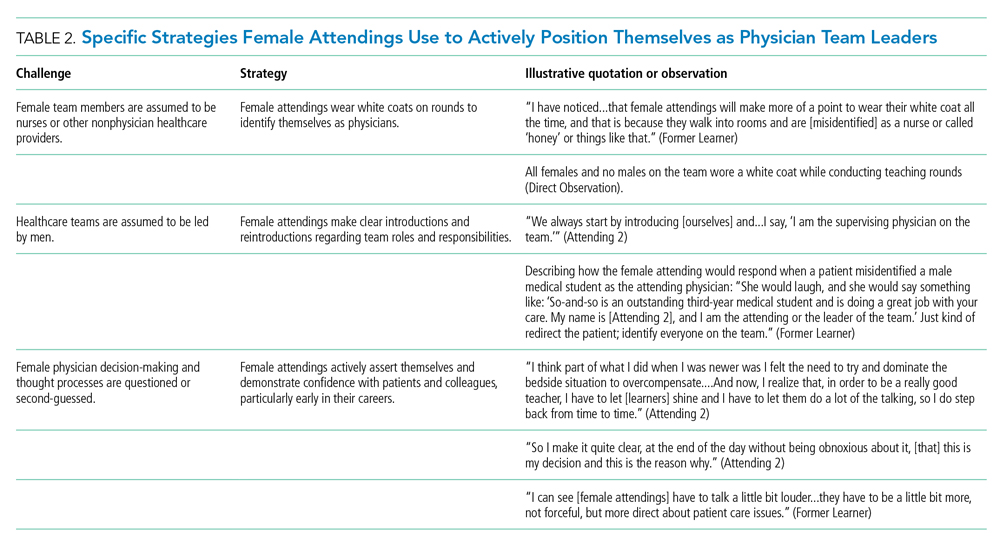

Our attendings frequently stated that they were assumed to be other healthcare provider types, such as nurses or physical therapists, and that these assumptions originated from patients, faculty, and staff (Table 2). Attending 3 commented, “I think every woman in this role has been mistaken for a different caretaker role, so lots of requests for nursing help. I’m sure I have taken more patients off of bed pans and brought more cups of water than maybe some of my male counterparts.” Some attendings responded to this challenge with the strategy of routinely wearing a white coat during rounds and patient encounters. This external visual cue was seen as a necessary reminder of the female attending role.

We found that patients and healthcare providers often believe teams are led by men, leading to a feeling of invisibility for female attendings. One current learner remarked, “If it was a new patient, more than likely, if we had a female attending, the patient’s eyes would always divert to the male physician.” This was not limited to patients. Attending 6 remembered comments from her consultants including, “‘Who is your attending? Let me talk with them,’ kind of assuming that I’m not the person making the decisions.” Female attendings would respond to this challenge by clearly introducing team members, including themselves, with roles and responsibilities. At times, this would require reintroductions and redirection if individuals still misidentified female team members.

Female attendings’ decision-making and thought processes were frequently second-guessed. This would often lead to power struggles with consultants, nurses, and learners. Attending 5 commented, “Even in residency, I felt this sometimes adversarial relationship with...female nurses where they would treat [female attendings] differently...questioning our decisions.” Female attendings would respond to this challenge by asserting themselves and demonstrating confidence with colleagues and at the bedside. This was an active process for women, as one former learner described: “[Female] attendings have to be a little bit more ‘on’—whatever ‘on’ is—more forceful, more direct....There is more slack given to a male attending.”

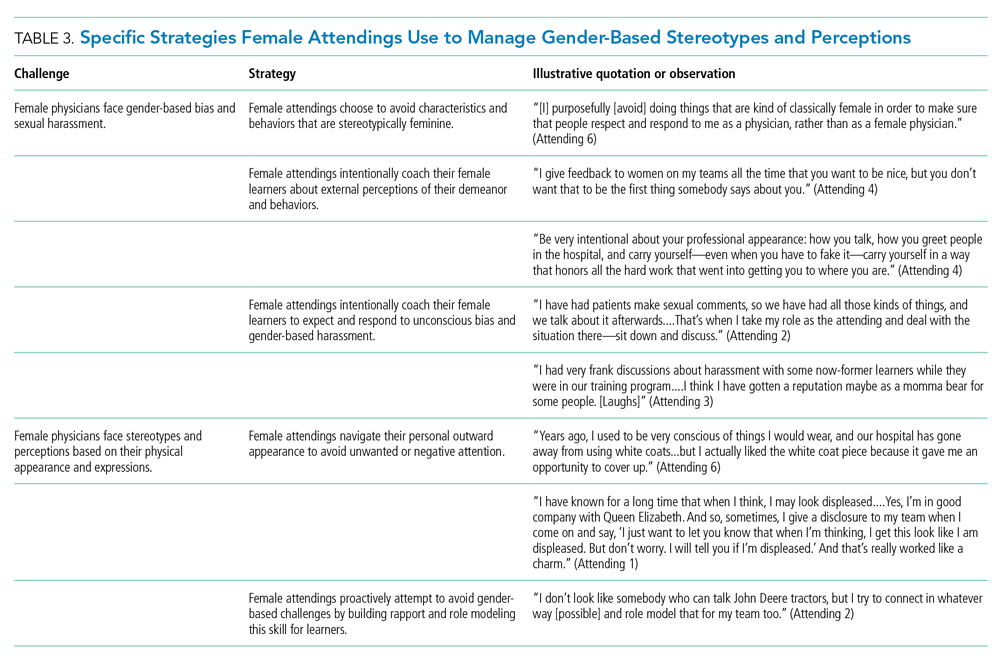

Female Attendings Consciously Work to Manage Gender-Based Stereotypes and Perceptions

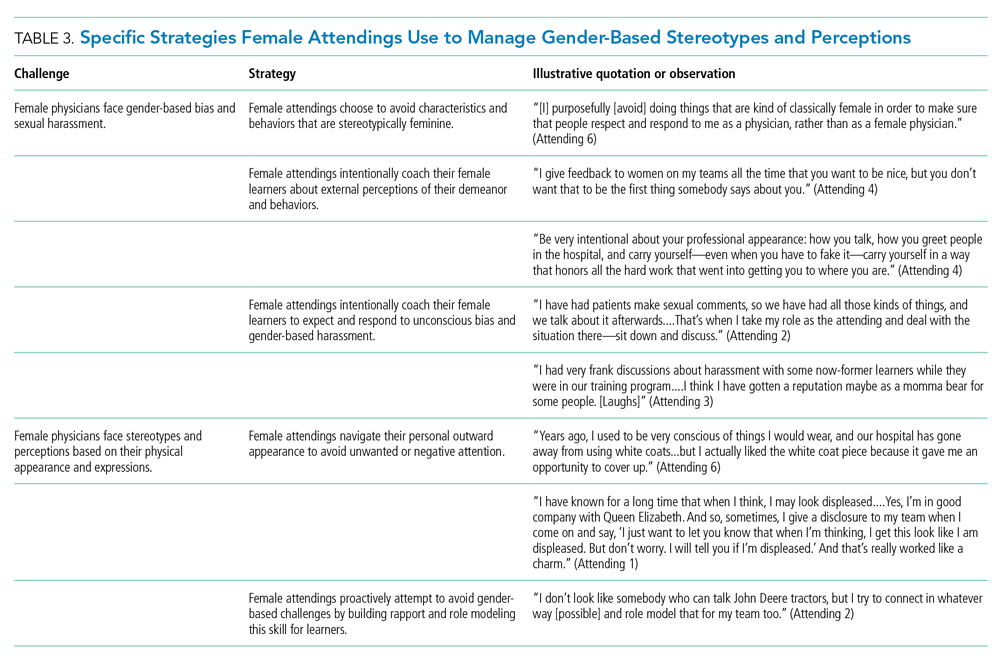

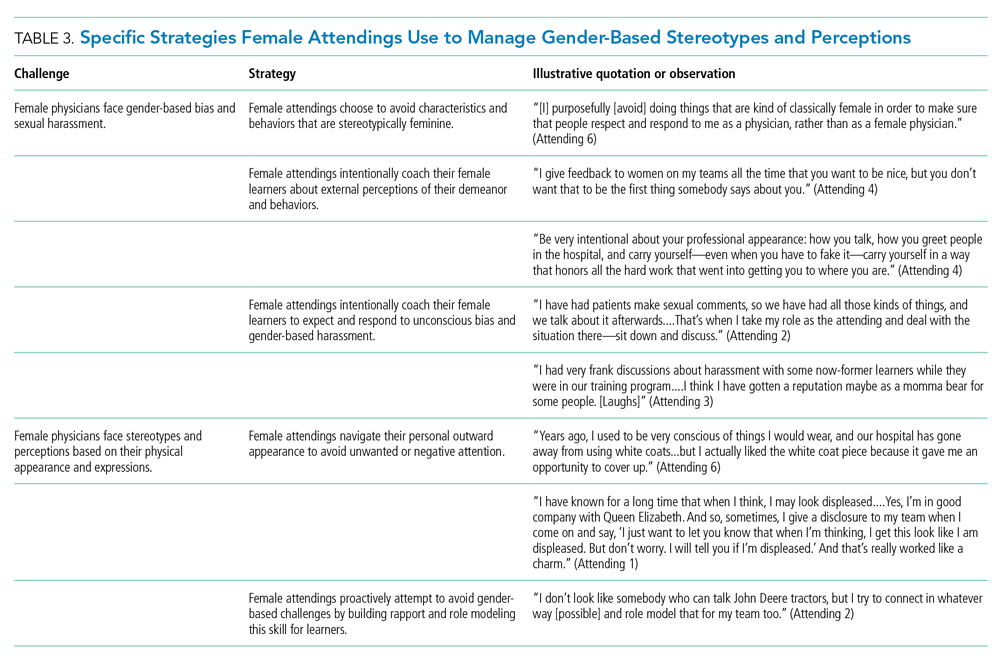

Our attendings navigated gender-based stereotypes and perceptions, ranging from subtle microaggressions to overt sexual harassment (Table 3). This required balance between extremes of being perceived as “too nice” and “too aggressive,” each of which was associated with negativity. Attending 1 remarked, “I know that other [female] faculty struggle with that a bit, with being...assertive. They are assertive, and it’s interpreted [negatively].” Attending 6 described insidiously sexist comments from patients: “‘You are too young to be a physician, you are too pretty to be a physician.’ ‘Oh, the woman doctor...rather than just ‘doctor.’” During one observation of rounds, a patient remarked to the attending, “You have cold hands. You know, I’m going to have to warm those up.” Our attendings responded to these challenges by proactively avoiding characteristics and behaviors considered to be stereotypically feminine in order to draw attention to their qualities as physicians rather than as women. During interviews, some attendings directed conversation away from themselves and instead placed emphasis on coaching female learners to navigate their own demeanors, behaviors, and responses to gender bias and harassment. This would include intentional planning of how to carry oneself, as well as feedback and debrief sessions after instances of harassment.

Our attendings grappled with how to physically portray themselves to avoid gender-based stereotypes. Attending 6 said, “Sometimes you might be taken less seriously if you pay more attention to your makeup or jewelry.” The same attending recalled “times where people would say inappropriate things based on what I was wearing—and I know that doesn’t happen with my male colleagues.” Our attendings responded to this challenge through purposeful choices of attire, personal appearance, and even external facial expressions that would avoid drawing unwanted or negative personal attention outside of the attending role.

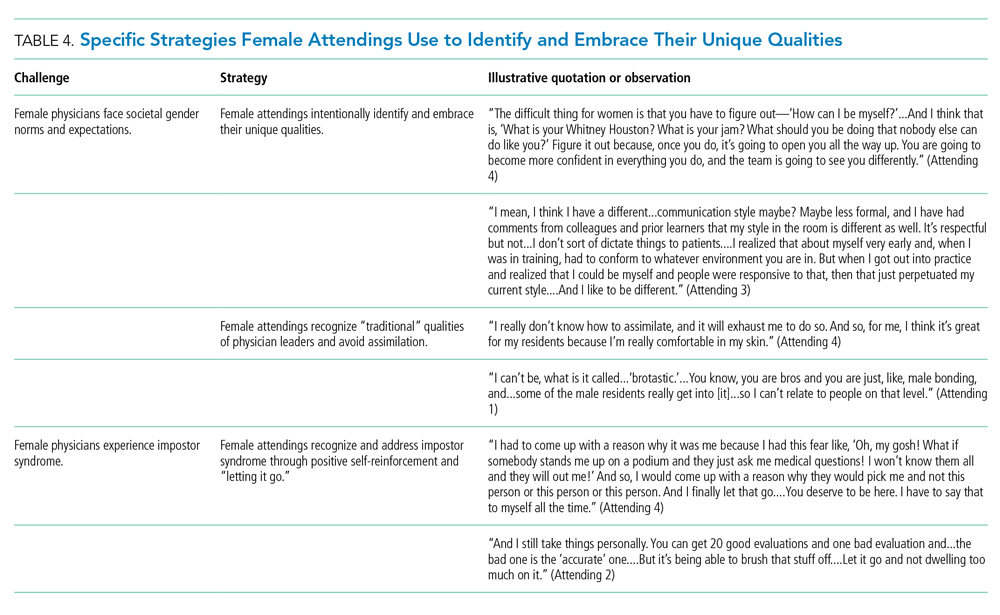

Female Attendings Intentionally Identify and Embrace Their Unique Qualities

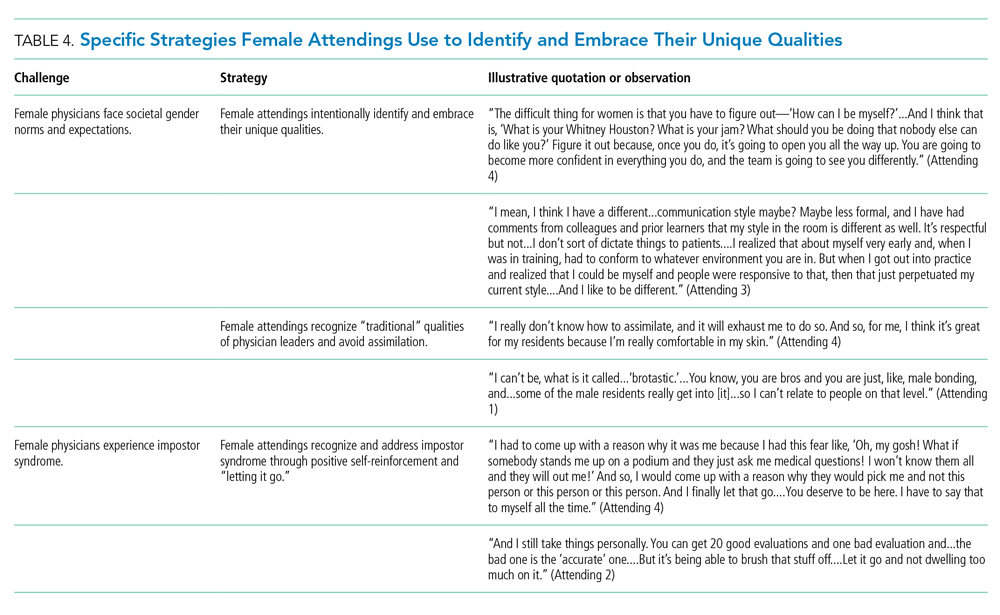

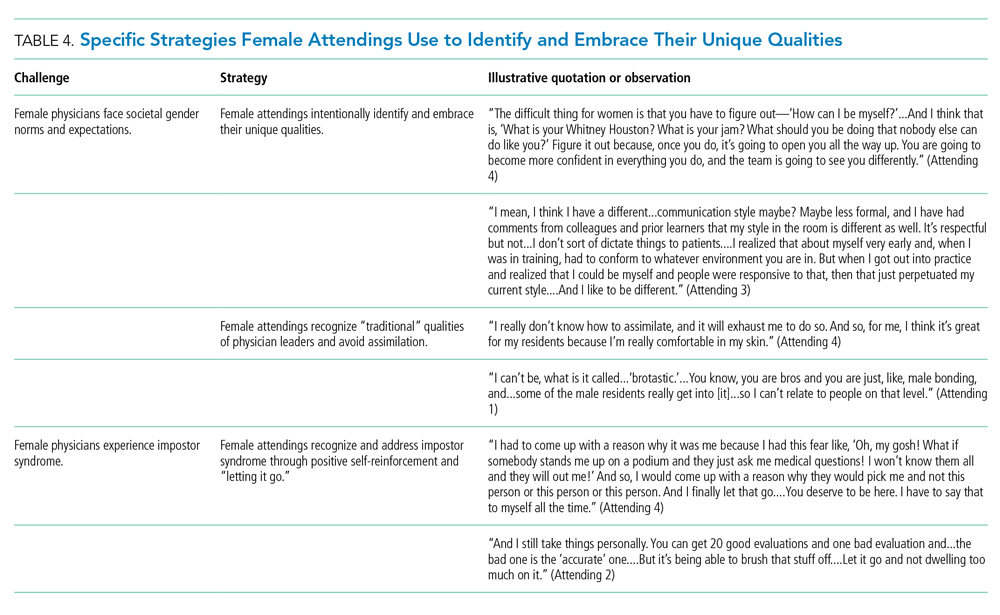

Our attendings identified societal gender norms and “traditional” masculine expectations in medicine (Table 4). Attending 4 drew attention to her institution’s healthcare leaders by remarking, “I think that women in medicine have similar challenges as women in other professional fields....Well, I guess it is different in that the pictures on the wall behind me are all White men.” Female attendings responded to this challenge by eschewing stereotypical qualities and intentionally finding and exhibiting their own unique strengths (eg, teaching approaches, areas of expertise, communication styles). By embracing their unique strengths, attendings gained confidence and felt more comfortable as physicians and educators. Advice from Attending 3 for other female physicians encapsulated this strategy: “But if [medicine] is what you love doing, then find a style that works for you, even if it’s different....Embrace being different.”

Several attendings identified patterns of thought in themselves that caused them to doubt their accomplishments and have a persistent fear of being exposed as a fraud, commonly known as impostor syndrome. Attending 2 summarized this with, “I know it’s irrational a little bit, but part of me [asks], ‘Am I getting all these opportunities because I’m female, because I’m a minority?’” Our attendings responded by recognizing impostor syndrome and addressing it through repeated positive self-reinforcing thoughts and language and by “letting go” of the doubt. Attending 4 recalled her feelings after being announced as a teaching award recipient for the fourth year in a row: “It was just like something changed in me....Maybe you are a good attending. Maybe you are doing something that is resonating with a unique class of medical students year after year.”

Our interviews also revealed strategies used by female attendings to support and advance their own careers, as well as those of other female faculty, to address the effects of impostor syndrome. Our participants noted the important role of female mentors and sponsors. One former learner mentioned, “I think some of the administration, there are definitely females that are helping promote [the attending].” During an observation, Attending 1 indicated that she was part of a network of women and junior faculty forged to promote each other’s work since “some people are good at self-promotion and some are not.” This group shares accomplishments by distributing and publicizing their accolades.

DISCUSSION

This multisite, qualitative study informs the complex ways in which exemplary female teaching attendings must navigate being women in medicine. We identified myriad challenges female attendings face originating from patients, from healthcare workers, and within themselves. Our attendings relied upon the following key strategies to mitigate such challenges: (1) they actively position themselves as physician team leaders, (2) they consciously work to manage gender-based stereotypes and perceptions, and (3) they intentionally identify and embrace their unique qualities.

Prior scholarship surrounding gender-based challenges has focused primarily on strategies to improve healthcare systems for women. Much scrutiny has been placed on elevating institutional culture,26-29 enacting clear policy surrounding sexual harassment,30 ensuring women are actively recruited and retained,31 providing resources to assist in work-life balance,26,32 and cultivating effective mentorship and social networks.11,33,34

While our findings support the importance of improving healthcare systems, they are more congruent with recent scholarship on explicit personal tactics to mitigate gender-based challenges. Researchers have suggested physicians use algorithmic responses to patient-initiated sexual harassment,35 advocate for those who experience harassment in real time,36 and engage in dedicated practice responding to harassment.37,38 Our results build on these studies by outlining strategies intended to navigate complex gender dynamics and role model approaches for learners. Interestingly, it was more common for attendings to discuss how they guide their learners and debrief after difficult situations than to discuss how they personally respond to gender-based harassment. While we are not certain why this occurred, three factors may have contributed. First, attendings mentioned that these conversations are often uncomfortable. Second, attendings appeared to accept a higher level of gender-based challenges than they would have tolerated for their learners. Lastly, although we did not gather demographic data from learners, several attendings voiced a strong desire to advocate for and equip female learners with strategies to address and navigate these challenges for themselves.

Gender stereotypes are ubiquitous and firmly rooted in long-standing belief patterns. Certain characteristics are considered masculine (eg, aggressiveness, confidence) and others feminine (eg, kindness, cooperation).10 Role congruity theory purports that stereotypes lead women to demonstrate behaviors that reflect socially accepted gender norms39 and that social approval is at risk if they behave in ways discordant with these norms.10,40 Our study provides perspectives from female physicians who walk the tightrope of forcefully asserting themselves more than their male counterparts while not being overly aggressive, since both approaches may have negative connotations.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted with a limited number of site visits, attendings, and learners. Likewise, attendings were internists with relatively advanced academic rank. This may reduce the study’s generalizability since attendings in other fields and at earlier career stages may utilize different strategies. However, we believe that if more senior-level female attendings experienced difficulties being recognized and legitimized in their roles, then one can assume that junior-level female faculty would experience these challenges even more so. Likewise, data saturation was not the goal of this exploratory study. Through intensive qualitative data collection, we sought to obtain an in-depth understanding of challenges and strategies. Second, many exemplary female attendings were overlooked by our selection methodology, particularly since women are often underrepresented in the factors we chose. The multisite design, modified snowball sampling, and purposeful randomized selection methodology were used to ensure quality and diversity. Third, attendings provided lists of their former learners, and thus, selection and recall biases may have been introduced since attendings may have more readily identified learners with whom they formed positive relationships. Finally, we cannot eliminate a potential Hawthorne effect on data collection. Researchers attempted to lessen this by standing apart from teams and remaining unobtrusive.

CONCLUSION

We identified strategies employed by exemplary female attendings to navigate gender-based challenges in their workplaces. We found that female attendings face unconscious bias, labels, power struggles, and harassment, simply because of their gender. They consciously and constantly navigate these challenges by positioning themselves to be seen and heard as team leaders, balancing aspects of their outward appearance and demeanor, embracing their differences and avoiding assimilation to masculine stereotypes of physician leaders, working to manage self-doubt, and coaching their female learners in these areas.

Acknowledgment

The authors are indebted to Suzanne Winter, MS, for assisting with coordination of study participants and site visits.

1. More ES. Restoring the Balance: Women Physicians and the Profession of Medicine, 1850-1995. Harvard University Press; 1999.

2. Table A-7.2: Applicants, first-time applicants, acceptees, and matriculants to U.S. medical schools by sex, 2010-2011 through 2019-2020. Association of American Medical Colleges. Published October 4, 2019. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-10/2019_FACTS_Table_A-7.2.pdf

3. Table 3: Distribution of full-time faculty by department, rank, and gender, 2015. Association of American Medical Colleges. Published December 31, 2015. Accessed September 14, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/download/481182/data/2015table3.pdf

4. Shrier DK, Zucker AN, Mercurio AE, Landry LJ, Rich M, Shrier LA. Generation to generation: discrimination and harassment experiences of physician mothers and their physician daughters. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16(6):883-894. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.0127

5. Osborn EH, Ernster VL, Martin JB. Women’s attitudes toward careers in academic medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Acad Med. 1992;67(1):59-62. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199201000-00012

6. Komaromy M, Bindman AB, Haber RJ, Sande MA. Sexual harassment in medical training. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(5):322-326. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199302043280507

7. Bickel J, Ruffin A. Gender-associated differences in matriculating and graduating medical students. Acad Med. 1995;70(6):552-529. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199506000-00021

8. Larsson C, Hensing G, Allebeck P. Sexual and gender-related harassment in medical education and research training: results from a Swedish survey. Med Educ. 2003;37(1):39-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01404.x

9. Cochran A, Hauschild T, Elder WB, Neumayer LA, Brasel KJ, Crandall ML. Perceived gender-based barriers to careers in academic surgery. Am J Surg. 2013;206(2):263-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.07.044

10. Heilman ME. Description and prescription: how gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. J Soc Issues. 2002;57(4):657-674. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00234

11. Amon MJ. Looking through the glass ceiling: a qualitative study of STEM women’s career narratives. Front Psychol. 2017;8:236. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00236

12. Choo EK, van Dis J, Kass D. Time’s up for medicine? only time will tell. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(17):1592-1593. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1809351

13. Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, et al. Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: a cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1033-1036. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1394

14. Hu YY, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741-1752. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1903759

15. Irby DM. How attending physicians make instructional decisions when conducting teaching rounds. Acad Med. 1992;67(10):630-638. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199210000-00002

16. Houchens N, Harrod M, Moody S, Fowler K, Saint S. Techniques and behaviors associated with exemplary inpatient general medicine teaching: an exploratory qualitative study. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):503-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2763

17. Houchens N, Harrod M, Fowler KE, Moody S, Saint S. How exemplary inpatient teaching physicians foster clinical reasoning. Am J Med. 2017;130(9):1113.e1‐1113.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.050

18. Saint S, Harrod M, Fowler KE, Houchens N. How exemplary teaching physicians interact with hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(12):974-978. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2844

19. Beckett L, Nettiksimmons J, Howell LP, Villablanca AC. Do family responsibilities and a clinical versus research faculty position affect satisfaction with career and work-life balance for medical school faculty? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(6):471-480. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.4858

20. Underrepresented in Medicine Definition. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed February 2, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

21. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2002.

22. Harder B. 2019-20 Best Hospitals Honor Roll and Medical Specialties Rankings. U.S. News and World Report - Health. Accessed January 6, 2018. https://health.usnews.com/health-care/best-hospitals/articles/best-hospitals-honor-roll-and-overview

23. Internal Medicine Residency Programs. Doximity. Accessed January 6, 2018. https://residency.doximity.com/programs?residency_specialty_id=39&sort_by=reputation&location_type=region

24. Member Groups Sections. American Medical Association. Accessed January 6, 2018. https://www.ama-assn.org/member-groups-sections

25. Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

26. Edmunds LD, Ovseiko PV, Shepperd S, et al. Why do women choose or reject careers in academic medicine? A narrative review of empirical evidence. Lancet. 2016;388(10062):2948-2958. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01091-0

27. Magrane D, Helitzer D, Morahan P, et al. Systems of career influences: a conceptual model for evaluating the professional development of women in academic medicine. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(12):1244-1251. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2012.3638

28. Pololi LH, Civian JT, Brennan RT, Dottolo AL, Krupat E. Experiencing the culture of academic medicine: gender matters, a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):201-207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2207-1

29. Krupat E, Pololi L, Schnell ER, Kern DE. Changing the culture of academic medicine: the C-Change learning action network and its impact at participating medical schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1252-1258. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31829e84e0

30. Viglianti EM, Oliverio AL, Cascino TM, et al. The policy gap: a survey of patient-perpetrated sexual harassment policies for residents and fellows in prominent US hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2326-2328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05229-7

31. Hoff T, Scott S. The gendered realities and talent management imperatives of women physicians. Health Care Manage Rev. 2016;41(3):189-199. https://doi.org/10.1097/hmr.0000000000000069

32. Seemann NM, Webster F, Holden HA, et al. Women in academic surgery: why is the playing field still not level? Am J Surg. 2016;211(2):343-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.036

33. Ahmadiyeh N, Cho NL, Kellogg KC, et al. Career satisfaction of women in surgery: perceptions, factors, and strategies. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(1):23-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.08.011

34. Coleman VH, Power ML, Williams S, Carpentieri A, Schulkin J. Continuing professional development: racial and gender differences in obstetrics and gynecology residents’ perceptions of mentoring. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2005;25(4):268-277. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.40

35. Viglianti EM, Oliverio AL, Meeks LM. Sexual harassment and abuse: when the patient is the perpetrator. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):368-370. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31502-2

36. Killeen OJ, Bridges L. Solving the silence. JAMA. 2018;320(19):1979-1980. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.15686

37. Cowan AN. Inappropriate behavior by patients and their families-call it out. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1441. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4348

38. Shankar M, Albert T, Yee N, et al. Approaches for residents to address problematic patient behavior: before, during, and after the clinical encounter. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(4):371-374. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-19-00075.1

39. Eagly AH, Karau SJ. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev. 2002;109(3):573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573

40. Ellinas EH, Fouad N, Byars-Winston A. Women and the decision to leave, linger, or lean in: predictors of intent to leave and aspirations to leadership and advancement in academic medicine. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2018;27(3):324-332. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2017.6457

The demographic composition of physicians has shifted dramatically in the last five decades. The number of women matriculating into medical school rose from 6% in the 1960s1 to 52% in 20192; women accounted for 39% of full-time faculty in 2015.3 Despite this evolution of the physician gender array, many challenges remain.4 Women represented only 35% of all associate professors and 22% of full professors in 2015.3 Women experience gender-based discrimination, hostility, and unconscious bias as medical trainees5-9 and as attending physicians10-13 with significant deleterious effects including burnout and suicidal thoughts.14 While types of gender-based challenges are well described in the literature, strategies to navigate and respond to these challenges are less understood.

The approaches and techniques of exemplary teaching attending physicians (hereafter referred to as “attendings”) have previously been reported from groups of predominantly male attendings.15-18 Because of gender-based challenges female physicians face that lead them to reduce their effort or leave the medical field,19 there is concern that prior scholarship in effective teaching may not adequately capture the approaches and techniques of female attendings. To our knowledge, no studies have specifically examined female attendings. Therefore, we sought to explore the lived experiences of six female attendings with particular emphasis on how they navigate and respond to gender-based challenges in clinical environments.

METHODS

Study Design and Sampling

This was a multisite study using an exploratory qualitative approach to inquiry. We aimed to examine techniques, approaches, and attitudes of outstanding general medicine teaching attendings among groups previously not well represented (ie, women and self-identified underrepresented minorities [URMs] in medicine). URM was defined by the Association of American Medical Colleges as “those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population.”20 A modified snowball sampling approach21 was employed to identify attendings as delineated below.

To maintain quality while guaranteeing diversity in geography and population, potential institutions in which to observe attendings were determined by first creating the following lists: The top 20 hospitals in the U.S. News & World Report’s 2017-2018 Best Hospitals Honor Roll,22 top-rated institutions by Doximity in each geographic region and among rural training sites,23 and four historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) with medical schools. Institutions visited during a previous similar study16 were excluded. Next, the list was narrowed to 25 by randomly selecting five in each main geographic region and five rural institutions. These were combined with all four HBCUs to create a final list of 29 institutions.

Next, division of hospital medicine chiefs (and/or general medicine chiefs) and internal medicine residency directors at each of these 29 institutions were asked to nominate exemplary attendings, particularly those who identified as women and URMs. Twelve attendings who were themselves observed in a previous study16 were also asked for nominations. Finally, recommendations were sought from leaders of relevant American Medical Association member groups.24

Using this sampling method, 43 physicians were identified. An internet search was conducted to identify individual characteristics including medical education, training, clinical and research interests, and educational awards. These characteristics were considered and discussed by the research team. Preference was given to those attendings nominated by more than one individual (n = 3), those who had received teaching awards, and those with interests involving women in medicine. Research team members narrowed the list to seven attendings who were contacted via email and invited to participate. One did not respond, while six agreed to participate. The six attendings identified current team members who would be rounding on the visit date. Attendings were asked to recommend 6-10 former learners; we contacted these former learners and invited them to participate. Former learners were included to understand lasting effects from their attendings.

Data Collection

Observations

All 1-day site visits were conducted by two research team members, a physician (NH) and a qualitative research specialist (MQ). In four visits, an additional author accompanied the research team. In order to ensure consistency and diversity in perspectives, all authors attended at least one visit. These occurred between April 16 and August 28, 2018. Each visit began with direct observation of attendings (n = 6) and current learners (n = 24) during inpatient general medicine teaching rounds. Each researcher unobtrusively recorded their observations via handwritten, open field notes, paying particular attention to group interactions, teaching approach, conversations within and peripheral to the team, and patient–team interactions. After each visit, researchers met to compare and combine field notes.

Interviews and Focus Groups

Researchers then conducted individual, semistructured interviews with attendings and focus groups with current (n = 21) and former (n = 17) learners. Focus groups with learners varied in size from two to five participants. Former learners were occasionally not available for on-site focus groups and were interviewed separately by telephone after the visit. The interview guide for attendings (Appendix 1) was adapted from the prior study16 but expanded with questions related to experiences, challenges, and approaches of female and URM physicians. A separate guide was used to facilitate focus groups with learners (Appendix 1

This study was determined to be exempt by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All participants were informed that their participation was completely voluntary and that they could terminate their involvement at any time.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a content analysis approach.25 Inductive coding was used to identify codes derived from the data. Two team members (MQ and MH) independently coded the first transcript to develop a codebook, then met to compare and discuss codes. Codes and definitions were entered into the codebook. These team members continued coding five additional transcripts, meeting to compare codes, discussing any discrepancies until agreement was reached, adding new codes identified, and ensuring consistent code application. They reviewed prior transcripts and recoded if necessary. Once no new codes were identified, one team member coded the remaining transcripts. The same codebook was used to code field note documents using the same iterative process. After all qualitative data were coded and verified, they were entered into NVivo 10. Code reports were generated and reviewed by three team members to identify themes and check for coding consistency.

Role of the Funding Source

This study received no external funding.

RESULTS

We examined six exemplary attendings through direct observation of rounds and individual interviews. We also discussed these attendings with 21 current learners and 17 former learners (Appendix 2). All attendings self-identified as female. The group was diverse in terms of race/ethnicity, with three identifying as Black or African American, two as Asian, and one as White or Caucasian. Levels of experience as an attending ranged from 8 to 20 years (mean, 15.3 years). At the time of observation, two were professors and four were associate professors. The group included all three attendings who had been nominated by more than one individual, and all six had won multiple teaching awards. The observation sites represented several areas of the United States (Table 1).

The coded interview data and field notes were categorized into three broad overlapping themes based on strategies our attendings used to respond to gender-based challenges. The following sections describe types of challenges faced by female attendings along with specific strategies they employed to actively position themselves as physician team leaders, manage gender-based stereotypes and perceptions, and identify and embrace their unique qualities. Illustrative quotations or observations that further elucidate meaning are provided.

Female Attendings Actively Position Themselves as Physician Team Leaders

Our attendings frequently stated that they were assumed to be other healthcare provider types, such as nurses or physical therapists, and that these assumptions originated from patients, faculty, and staff (Table 2). Attending 3 commented, “I think every woman in this role has been mistaken for a different caretaker role, so lots of requests for nursing help. I’m sure I have taken more patients off of bed pans and brought more cups of water than maybe some of my male counterparts.” Some attendings responded to this challenge with the strategy of routinely wearing a white coat during rounds and patient encounters. This external visual cue was seen as a necessary reminder of the female attending role.

We found that patients and healthcare providers often believe teams are led by men, leading to a feeling of invisibility for female attendings. One current learner remarked, “If it was a new patient, more than likely, if we had a female attending, the patient’s eyes would always divert to the male physician.” This was not limited to patients. Attending 6 remembered comments from her consultants including, “‘Who is your attending? Let me talk with them,’ kind of assuming that I’m not the person making the decisions.” Female attendings would respond to this challenge by clearly introducing team members, including themselves, with roles and responsibilities. At times, this would require reintroductions and redirection if individuals still misidentified female team members.

Female attendings’ decision-making and thought processes were frequently second-guessed. This would often lead to power struggles with consultants, nurses, and learners. Attending 5 commented, “Even in residency, I felt this sometimes adversarial relationship with...female nurses where they would treat [female attendings] differently...questioning our decisions.” Female attendings would respond to this challenge by asserting themselves and demonstrating confidence with colleagues and at the bedside. This was an active process for women, as one former learner described: “[Female] attendings have to be a little bit more ‘on’—whatever ‘on’ is—more forceful, more direct....There is more slack given to a male attending.”

Female Attendings Consciously Work to Manage Gender-Based Stereotypes and Perceptions

Our attendings navigated gender-based stereotypes and perceptions, ranging from subtle microaggressions to overt sexual harassment (Table 3). This required balance between extremes of being perceived as “too nice” and “too aggressive,” each of which was associated with negativity. Attending 1 remarked, “I know that other [female] faculty struggle with that a bit, with being...assertive. They are assertive, and it’s interpreted [negatively].” Attending 6 described insidiously sexist comments from patients: “‘You are too young to be a physician, you are too pretty to be a physician.’ ‘Oh, the woman doctor...rather than just ‘doctor.’” During one observation of rounds, a patient remarked to the attending, “You have cold hands. You know, I’m going to have to warm those up.” Our attendings responded to these challenges by proactively avoiding characteristics and behaviors considered to be stereotypically feminine in order to draw attention to their qualities as physicians rather than as women. During interviews, some attendings directed conversation away from themselves and instead placed emphasis on coaching female learners to navigate their own demeanors, behaviors, and responses to gender bias and harassment. This would include intentional planning of how to carry oneself, as well as feedback and debrief sessions after instances of harassment.

Our attendings grappled with how to physically portray themselves to avoid gender-based stereotypes. Attending 6 said, “Sometimes you might be taken less seriously if you pay more attention to your makeup or jewelry.” The same attending recalled “times where people would say inappropriate things based on what I was wearing—and I know that doesn’t happen with my male colleagues.” Our attendings responded to this challenge through purposeful choices of attire, personal appearance, and even external facial expressions that would avoid drawing unwanted or negative personal attention outside of the attending role.

Female Attendings Intentionally Identify and Embrace Their Unique Qualities

Our attendings identified societal gender norms and “traditional” masculine expectations in medicine (Table 4). Attending 4 drew attention to her institution’s healthcare leaders by remarking, “I think that women in medicine have similar challenges as women in other professional fields....Well, I guess it is different in that the pictures on the wall behind me are all White men.” Female attendings responded to this challenge by eschewing stereotypical qualities and intentionally finding and exhibiting their own unique strengths (eg, teaching approaches, areas of expertise, communication styles). By embracing their unique strengths, attendings gained confidence and felt more comfortable as physicians and educators. Advice from Attending 3 for other female physicians encapsulated this strategy: “But if [medicine] is what you love doing, then find a style that works for you, even if it’s different....Embrace being different.”

Several attendings identified patterns of thought in themselves that caused them to doubt their accomplishments and have a persistent fear of being exposed as a fraud, commonly known as impostor syndrome. Attending 2 summarized this with, “I know it’s irrational a little bit, but part of me [asks], ‘Am I getting all these opportunities because I’m female, because I’m a minority?’” Our attendings responded by recognizing impostor syndrome and addressing it through repeated positive self-reinforcing thoughts and language and by “letting go” of the doubt. Attending 4 recalled her feelings after being announced as a teaching award recipient for the fourth year in a row: “It was just like something changed in me....Maybe you are a good attending. Maybe you are doing something that is resonating with a unique class of medical students year after year.”

Our interviews also revealed strategies used by female attendings to support and advance their own careers, as well as those of other female faculty, to address the effects of impostor syndrome. Our participants noted the important role of female mentors and sponsors. One former learner mentioned, “I think some of the administration, there are definitely females that are helping promote [the attending].” During an observation, Attending 1 indicated that she was part of a network of women and junior faculty forged to promote each other’s work since “some people are good at self-promotion and some are not.” This group shares accomplishments by distributing and publicizing their accolades.

DISCUSSION

This multisite, qualitative study informs the complex ways in which exemplary female teaching attendings must navigate being women in medicine. We identified myriad challenges female attendings face originating from patients, from healthcare workers, and within themselves. Our attendings relied upon the following key strategies to mitigate such challenges: (1) they actively position themselves as physician team leaders, (2) they consciously work to manage gender-based stereotypes and perceptions, and (3) they intentionally identify and embrace their unique qualities.

Prior scholarship surrounding gender-based challenges has focused primarily on strategies to improve healthcare systems for women. Much scrutiny has been placed on elevating institutional culture,26-29 enacting clear policy surrounding sexual harassment,30 ensuring women are actively recruited and retained,31 providing resources to assist in work-life balance,26,32 and cultivating effective mentorship and social networks.11,33,34

While our findings support the importance of improving healthcare systems, they are more congruent with recent scholarship on explicit personal tactics to mitigate gender-based challenges. Researchers have suggested physicians use algorithmic responses to patient-initiated sexual harassment,35 advocate for those who experience harassment in real time,36 and engage in dedicated practice responding to harassment.37,38 Our results build on these studies by outlining strategies intended to navigate complex gender dynamics and role model approaches for learners. Interestingly, it was more common for attendings to discuss how they guide their learners and debrief after difficult situations than to discuss how they personally respond to gender-based harassment. While we are not certain why this occurred, three factors may have contributed. First, attendings mentioned that these conversations are often uncomfortable. Second, attendings appeared to accept a higher level of gender-based challenges than they would have tolerated for their learners. Lastly, although we did not gather demographic data from learners, several attendings voiced a strong desire to advocate for and equip female learners with strategies to address and navigate these challenges for themselves.

Gender stereotypes are ubiquitous and firmly rooted in long-standing belief patterns. Certain characteristics are considered masculine (eg, aggressiveness, confidence) and others feminine (eg, kindness, cooperation).10 Role congruity theory purports that stereotypes lead women to demonstrate behaviors that reflect socially accepted gender norms39 and that social approval is at risk if they behave in ways discordant with these norms.10,40 Our study provides perspectives from female physicians who walk the tightrope of forcefully asserting themselves more than their male counterparts while not being overly aggressive, since both approaches may have negative connotations.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted with a limited number of site visits, attendings, and learners. Likewise, attendings were internists with relatively advanced academic rank. This may reduce the study’s generalizability since attendings in other fields and at earlier career stages may utilize different strategies. However, we believe that if more senior-level female attendings experienced difficulties being recognized and legitimized in their roles, then one can assume that junior-level female faculty would experience these challenges even more so. Likewise, data saturation was not the goal of this exploratory study. Through intensive qualitative data collection, we sought to obtain an in-depth understanding of challenges and strategies. Second, many exemplary female attendings were overlooked by our selection methodology, particularly since women are often underrepresented in the factors we chose. The multisite design, modified snowball sampling, and purposeful randomized selection methodology were used to ensure quality and diversity. Third, attendings provided lists of their former learners, and thus, selection and recall biases may have been introduced since attendings may have more readily identified learners with whom they formed positive relationships. Finally, we cannot eliminate a potential Hawthorne effect on data collection. Researchers attempted to lessen this by standing apart from teams and remaining unobtrusive.

CONCLUSION

We identified strategies employed by exemplary female attendings to navigate gender-based challenges in their workplaces. We found that female attendings face unconscious bias, labels, power struggles, and harassment, simply because of their gender. They consciously and constantly navigate these challenges by positioning themselves to be seen and heard as team leaders, balancing aspects of their outward appearance and demeanor, embracing their differences and avoiding assimilation to masculine stereotypes of physician leaders, working to manage self-doubt, and coaching their female learners in these areas.

Acknowledgment

The authors are indebted to Suzanne Winter, MS, for assisting with coordination of study participants and site visits.

The demographic composition of physicians has shifted dramatically in the last five decades. The number of women matriculating into medical school rose from 6% in the 1960s1 to 52% in 20192; women accounted for 39% of full-time faculty in 2015.3 Despite this evolution of the physician gender array, many challenges remain.4 Women represented only 35% of all associate professors and 22% of full professors in 2015.3 Women experience gender-based discrimination, hostility, and unconscious bias as medical trainees5-9 and as attending physicians10-13 with significant deleterious effects including burnout and suicidal thoughts.14 While types of gender-based challenges are well described in the literature, strategies to navigate and respond to these challenges are less understood.

The approaches and techniques of exemplary teaching attending physicians (hereafter referred to as “attendings”) have previously been reported from groups of predominantly male attendings.15-18 Because of gender-based challenges female physicians face that lead them to reduce their effort or leave the medical field,19 there is concern that prior scholarship in effective teaching may not adequately capture the approaches and techniques of female attendings. To our knowledge, no studies have specifically examined female attendings. Therefore, we sought to explore the lived experiences of six female attendings with particular emphasis on how they navigate and respond to gender-based challenges in clinical environments.

METHODS

Study Design and Sampling

This was a multisite study using an exploratory qualitative approach to inquiry. We aimed to examine techniques, approaches, and attitudes of outstanding general medicine teaching attendings among groups previously not well represented (ie, women and self-identified underrepresented minorities [URMs] in medicine). URM was defined by the Association of American Medical Colleges as “those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population.”20 A modified snowball sampling approach21 was employed to identify attendings as delineated below.

To maintain quality while guaranteeing diversity in geography and population, potential institutions in which to observe attendings were determined by first creating the following lists: The top 20 hospitals in the U.S. News & World Report’s 2017-2018 Best Hospitals Honor Roll,22 top-rated institutions by Doximity in each geographic region and among rural training sites,23 and four historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) with medical schools. Institutions visited during a previous similar study16 were excluded. Next, the list was narrowed to 25 by randomly selecting five in each main geographic region and five rural institutions. These were combined with all four HBCUs to create a final list of 29 institutions.

Next, division of hospital medicine chiefs (and/or general medicine chiefs) and internal medicine residency directors at each of these 29 institutions were asked to nominate exemplary attendings, particularly those who identified as women and URMs. Twelve attendings who were themselves observed in a previous study16 were also asked for nominations. Finally, recommendations were sought from leaders of relevant American Medical Association member groups.24

Using this sampling method, 43 physicians were identified. An internet search was conducted to identify individual characteristics including medical education, training, clinical and research interests, and educational awards. These characteristics were considered and discussed by the research team. Preference was given to those attendings nominated by more than one individual (n = 3), those who had received teaching awards, and those with interests involving women in medicine. Research team members narrowed the list to seven attendings who were contacted via email and invited to participate. One did not respond, while six agreed to participate. The six attendings identified current team members who would be rounding on the visit date. Attendings were asked to recommend 6-10 former learners; we contacted these former learners and invited them to participate. Former learners were included to understand lasting effects from their attendings.

Data Collection

Observations

All 1-day site visits were conducted by two research team members, a physician (NH) and a qualitative research specialist (MQ). In four visits, an additional author accompanied the research team. In order to ensure consistency and diversity in perspectives, all authors attended at least one visit. These occurred between April 16 and August 28, 2018. Each visit began with direct observation of attendings (n = 6) and current learners (n = 24) during inpatient general medicine teaching rounds. Each researcher unobtrusively recorded their observations via handwritten, open field notes, paying particular attention to group interactions, teaching approach, conversations within and peripheral to the team, and patient–team interactions. After each visit, researchers met to compare and combine field notes.

Interviews and Focus Groups

Researchers then conducted individual, semistructured interviews with attendings and focus groups with current (n = 21) and former (n = 17) learners. Focus groups with learners varied in size from two to five participants. Former learners were occasionally not available for on-site focus groups and were interviewed separately by telephone after the visit. The interview guide for attendings (Appendix 1) was adapted from the prior study16 but expanded with questions related to experiences, challenges, and approaches of female and URM physicians. A separate guide was used to facilitate focus groups with learners (Appendix 1

This study was determined to be exempt by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board. All participants were informed that their participation was completely voluntary and that they could terminate their involvement at any time.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a content analysis approach.25 Inductive coding was used to identify codes derived from the data. Two team members (MQ and MH) independently coded the first transcript to develop a codebook, then met to compare and discuss codes. Codes and definitions were entered into the codebook. These team members continued coding five additional transcripts, meeting to compare codes, discussing any discrepancies until agreement was reached, adding new codes identified, and ensuring consistent code application. They reviewed prior transcripts and recoded if necessary. Once no new codes were identified, one team member coded the remaining transcripts. The same codebook was used to code field note documents using the same iterative process. After all qualitative data were coded and verified, they were entered into NVivo 10. Code reports were generated and reviewed by three team members to identify themes and check for coding consistency.

Role of the Funding Source

This study received no external funding.

RESULTS

We examined six exemplary attendings through direct observation of rounds and individual interviews. We also discussed these attendings with 21 current learners and 17 former learners (Appendix 2). All attendings self-identified as female. The group was diverse in terms of race/ethnicity, with three identifying as Black or African American, two as Asian, and one as White or Caucasian. Levels of experience as an attending ranged from 8 to 20 years (mean, 15.3 years). At the time of observation, two were professors and four were associate professors. The group included all three attendings who had been nominated by more than one individual, and all six had won multiple teaching awards. The observation sites represented several areas of the United States (Table 1).

The coded interview data and field notes were categorized into three broad overlapping themes based on strategies our attendings used to respond to gender-based challenges. The following sections describe types of challenges faced by female attendings along with specific strategies they employed to actively position themselves as physician team leaders, manage gender-based stereotypes and perceptions, and identify and embrace their unique qualities. Illustrative quotations or observations that further elucidate meaning are provided.

Female Attendings Actively Position Themselves as Physician Team Leaders

Our attendings frequently stated that they were assumed to be other healthcare provider types, such as nurses or physical therapists, and that these assumptions originated from patients, faculty, and staff (Table 2). Attending 3 commented, “I think every woman in this role has been mistaken for a different caretaker role, so lots of requests for nursing help. I’m sure I have taken more patients off of bed pans and brought more cups of water than maybe some of my male counterparts.” Some attendings responded to this challenge with the strategy of routinely wearing a white coat during rounds and patient encounters. This external visual cue was seen as a necessary reminder of the female attending role.

We found that patients and healthcare providers often believe teams are led by men, leading to a feeling of invisibility for female attendings. One current learner remarked, “If it was a new patient, more than likely, if we had a female attending, the patient’s eyes would always divert to the male physician.” This was not limited to patients. Attending 6 remembered comments from her consultants including, “‘Who is your attending? Let me talk with them,’ kind of assuming that I’m not the person making the decisions.” Female attendings would respond to this challenge by clearly introducing team members, including themselves, with roles and responsibilities. At times, this would require reintroductions and redirection if individuals still misidentified female team members.

Female attendings’ decision-making and thought processes were frequently second-guessed. This would often lead to power struggles with consultants, nurses, and learners. Attending 5 commented, “Even in residency, I felt this sometimes adversarial relationship with...female nurses where they would treat [female attendings] differently...questioning our decisions.” Female attendings would respond to this challenge by asserting themselves and demonstrating confidence with colleagues and at the bedside. This was an active process for women, as one former learner described: “[Female] attendings have to be a little bit more ‘on’—whatever ‘on’ is—more forceful, more direct....There is more slack given to a male attending.”

Female Attendings Consciously Work to Manage Gender-Based Stereotypes and Perceptions

Our attendings navigated gender-based stereotypes and perceptions, ranging from subtle microaggressions to overt sexual harassment (Table 3). This required balance between extremes of being perceived as “too nice” and “too aggressive,” each of which was associated with negativity. Attending 1 remarked, “I know that other [female] faculty struggle with that a bit, with being...assertive. They are assertive, and it’s interpreted [negatively].” Attending 6 described insidiously sexist comments from patients: “‘You are too young to be a physician, you are too pretty to be a physician.’ ‘Oh, the woman doctor...rather than just ‘doctor.’” During one observation of rounds, a patient remarked to the attending, “You have cold hands. You know, I’m going to have to warm those up.” Our attendings responded to these challenges by proactively avoiding characteristics and behaviors considered to be stereotypically feminine in order to draw attention to their qualities as physicians rather than as women. During interviews, some attendings directed conversation away from themselves and instead placed emphasis on coaching female learners to navigate their own demeanors, behaviors, and responses to gender bias and harassment. This would include intentional planning of how to carry oneself, as well as feedback and debrief sessions after instances of harassment.

Our attendings grappled with how to physically portray themselves to avoid gender-based stereotypes. Attending 6 said, “Sometimes you might be taken less seriously if you pay more attention to your makeup or jewelry.” The same attending recalled “times where people would say inappropriate things based on what I was wearing—and I know that doesn’t happen with my male colleagues.” Our attendings responded to this challenge through purposeful choices of attire, personal appearance, and even external facial expressions that would avoid drawing unwanted or negative personal attention outside of the attending role.

Female Attendings Intentionally Identify and Embrace Their Unique Qualities

Our attendings identified societal gender norms and “traditional” masculine expectations in medicine (Table 4). Attending 4 drew attention to her institution’s healthcare leaders by remarking, “I think that women in medicine have similar challenges as women in other professional fields....Well, I guess it is different in that the pictures on the wall behind me are all White men.” Female attendings responded to this challenge by eschewing stereotypical qualities and intentionally finding and exhibiting their own unique strengths (eg, teaching approaches, areas of expertise, communication styles). By embracing their unique strengths, attendings gained confidence and felt more comfortable as physicians and educators. Advice from Attending 3 for other female physicians encapsulated this strategy: “But if [medicine] is what you love doing, then find a style that works for you, even if it’s different....Embrace being different.”

Several attendings identified patterns of thought in themselves that caused them to doubt their accomplishments and have a persistent fear of being exposed as a fraud, commonly known as impostor syndrome. Attending 2 summarized this with, “I know it’s irrational a little bit, but part of me [asks], ‘Am I getting all these opportunities because I’m female, because I’m a minority?’” Our attendings responded by recognizing impostor syndrome and addressing it through repeated positive self-reinforcing thoughts and language and by “letting go” of the doubt. Attending 4 recalled her feelings after being announced as a teaching award recipient for the fourth year in a row: “It was just like something changed in me....Maybe you are a good attending. Maybe you are doing something that is resonating with a unique class of medical students year after year.”

Our interviews also revealed strategies used by female attendings to support and advance their own careers, as well as those of other female faculty, to address the effects of impostor syndrome. Our participants noted the important role of female mentors and sponsors. One former learner mentioned, “I think some of the administration, there are definitely females that are helping promote [the attending].” During an observation, Attending 1 indicated that she was part of a network of women and junior faculty forged to promote each other’s work since “some people are good at self-promotion and some are not.” This group shares accomplishments by distributing and publicizing their accolades.

DISCUSSION

This multisite, qualitative study informs the complex ways in which exemplary female teaching attendings must navigate being women in medicine. We identified myriad challenges female attendings face originating from patients, from healthcare workers, and within themselves. Our attendings relied upon the following key strategies to mitigate such challenges: (1) they actively position themselves as physician team leaders, (2) they consciously work to manage gender-based stereotypes and perceptions, and (3) they intentionally identify and embrace their unique qualities.

Prior scholarship surrounding gender-based challenges has focused primarily on strategies to improve healthcare systems for women. Much scrutiny has been placed on elevating institutional culture,26-29 enacting clear policy surrounding sexual harassment,30 ensuring women are actively recruited and retained,31 providing resources to assist in work-life balance,26,32 and cultivating effective mentorship and social networks.11,33,34

While our findings support the importance of improving healthcare systems, they are more congruent with recent scholarship on explicit personal tactics to mitigate gender-based challenges. Researchers have suggested physicians use algorithmic responses to patient-initiated sexual harassment,35 advocate for those who experience harassment in real time,36 and engage in dedicated practice responding to harassment.37,38 Our results build on these studies by outlining strategies intended to navigate complex gender dynamics and role model approaches for learners. Interestingly, it was more common for attendings to discuss how they guide their learners and debrief after difficult situations than to discuss how they personally respond to gender-based harassment. While we are not certain why this occurred, three factors may have contributed. First, attendings mentioned that these conversations are often uncomfortable. Second, attendings appeared to accept a higher level of gender-based challenges than they would have tolerated for their learners. Lastly, although we did not gather demographic data from learners, several attendings voiced a strong desire to advocate for and equip female learners with strategies to address and navigate these challenges for themselves.

Gender stereotypes are ubiquitous and firmly rooted in long-standing belief patterns. Certain characteristics are considered masculine (eg, aggressiveness, confidence) and others feminine (eg, kindness, cooperation).10 Role congruity theory purports that stereotypes lead women to demonstrate behaviors that reflect socially accepted gender norms39 and that social approval is at risk if they behave in ways discordant with these norms.10,40 Our study provides perspectives from female physicians who walk the tightrope of forcefully asserting themselves more than their male counterparts while not being overly aggressive, since both approaches may have negative connotations.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted with a limited number of site visits, attendings, and learners. Likewise, attendings were internists with relatively advanced academic rank. This may reduce the study’s generalizability since attendings in other fields and at earlier career stages may utilize different strategies. However, we believe that if more senior-level female attendings experienced difficulties being recognized and legitimized in their roles, then one can assume that junior-level female faculty would experience these challenges even more so. Likewise, data saturation was not the goal of this exploratory study. Through intensive qualitative data collection, we sought to obtain an in-depth understanding of challenges and strategies. Second, many exemplary female attendings were overlooked by our selection methodology, particularly since women are often underrepresented in the factors we chose. The multisite design, modified snowball sampling, and purposeful randomized selection methodology were used to ensure quality and diversity. Third, attendings provided lists of their former learners, and thus, selection and recall biases may have been introduced since attendings may have more readily identified learners with whom they formed positive relationships. Finally, we cannot eliminate a potential Hawthorne effect on data collection. Researchers attempted to lessen this by standing apart from teams and remaining unobtrusive.

CONCLUSION

We identified strategies employed by exemplary female attendings to navigate gender-based challenges in their workplaces. We found that female attendings face unconscious bias, labels, power struggles, and harassment, simply because of their gender. They consciously and constantly navigate these challenges by positioning themselves to be seen and heard as team leaders, balancing aspects of their outward appearance and demeanor, embracing their differences and avoiding assimilation to masculine stereotypes of physician leaders, working to manage self-doubt, and coaching their female learners in these areas.

Acknowledgment

The authors are indebted to Suzanne Winter, MS, for assisting with coordination of study participants and site visits.

1. More ES. Restoring the Balance: Women Physicians and the Profession of Medicine, 1850-1995. Harvard University Press; 1999.

2. Table A-7.2: Applicants, first-time applicants, acceptees, and matriculants to U.S. medical schools by sex, 2010-2011 through 2019-2020. Association of American Medical Colleges. Published October 4, 2019. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-10/2019_FACTS_Table_A-7.2.pdf

3. Table 3: Distribution of full-time faculty by department, rank, and gender, 2015. Association of American Medical Colleges. Published December 31, 2015. Accessed September 14, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/download/481182/data/2015table3.pdf

4. Shrier DK, Zucker AN, Mercurio AE, Landry LJ, Rich M, Shrier LA. Generation to generation: discrimination and harassment experiences of physician mothers and their physician daughters. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16(6):883-894. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2006.0127

5. Osborn EH, Ernster VL, Martin JB. Women’s attitudes toward careers in academic medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. Acad Med. 1992;67(1):59-62. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199201000-00012

6. Komaromy M, Bindman AB, Haber RJ, Sande MA. Sexual harassment in medical training. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(5):322-326. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199302043280507

7. Bickel J, Ruffin A. Gender-associated differences in matriculating and graduating medical students. Acad Med. 1995;70(6):552-529. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199506000-00021

8. Larsson C, Hensing G, Allebeck P. Sexual and gender-related harassment in medical education and research training: results from a Swedish survey. Med Educ. 2003;37(1):39-50. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2923.2003.01404.x

9. Cochran A, Hauschild T, Elder WB, Neumayer LA, Brasel KJ, Crandall ML. Perceived gender-based barriers to careers in academic surgery. Am J Surg. 2013;206(2):263-268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.07.044

10. Heilman ME. Description and prescription: how gender stereotypes prevent women’s ascent up the organizational ladder. J Soc Issues. 2002;57(4):657-674. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00234

11. Amon MJ. Looking through the glass ceiling: a qualitative study of STEM women’s career narratives. Front Psychol. 2017;8:236. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00236

12. Choo EK, van Dis J, Kass D. Time’s up for medicine? only time will tell. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(17):1592-1593. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp1809351

13. Adesoye T, Mangurian C, Choo EK, et al. Perceived discrimination experienced by physician mothers and desired workplace changes: a cross-sectional survey. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):1033-1036. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1394

14. Hu YY, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(18):1741-1752. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsa1903759

15. Irby DM. How attending physicians make instructional decisions when conducting teaching rounds. Acad Med. 1992;67(10):630-638. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199210000-00002

16. Houchens N, Harrod M, Moody S, Fowler K, Saint S. Techniques and behaviors associated with exemplary inpatient general medicine teaching: an exploratory qualitative study. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):503-509. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2763

17. Houchens N, Harrod M, Fowler KE, Moody S, Saint S. How exemplary inpatient teaching physicians foster clinical reasoning. Am J Med. 2017;130(9):1113.e1‐1113.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.03.050

18. Saint S, Harrod M, Fowler KE, Houchens N. How exemplary teaching physicians interact with hospitalized patients. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(12):974-978. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2844

19. Beckett L, Nettiksimmons J, Howell LP, Villablanca AC. Do family responsibilities and a clinical versus research faculty position affect satisfaction with career and work-life balance for medical school faculty? J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(6):471-480. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.4858

20. Underrepresented in Medicine Definition. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed February 2, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/mission-areas/diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

21. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. 3rd ed. Sage Publications; 2002.

22. Harder B. 2019-20 Best Hospitals Honor Roll and Medical Specialties Rankings. U.S. News and World Report - Health. Accessed January 6, 2018. https://health.usnews.com/health-care/best-hospitals/articles/best-hospitals-honor-roll-and-overview

23. Internal Medicine Residency Programs. Doximity. Accessed January 6, 2018. https://residency.doximity.com/programs?residency_specialty_id=39&sort_by=reputation&location_type=region

24. Member Groups Sections. American Medical Association. Accessed January 6, 2018. https://www.ama-assn.org/member-groups-sections

25. Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107-115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

26. Edmunds LD, Ovseiko PV, Shepperd S, et al. Why do women choose or reject careers in academic medicine? A narrative review of empirical evidence. Lancet. 2016;388(10062):2948-2958. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01091-0

27. Magrane D, Helitzer D, Morahan P, et al. Systems of career influences: a conceptual model for evaluating the professional development of women in academic medicine. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2012;21(12):1244-1251. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2012.3638

28. Pololi LH, Civian JT, Brennan RT, Dottolo AL, Krupat E. Experiencing the culture of academic medicine: gender matters, a national study. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):201-207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2207-1

29. Krupat E, Pololi L, Schnell ER, Kern DE. Changing the culture of academic medicine: the C-Change learning action network and its impact at participating medical schools. Acad Med. 2013;88(9):1252-1258. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0b013e31829e84e0

30. Viglianti EM, Oliverio AL, Cascino TM, et al. The policy gap: a survey of patient-perpetrated sexual harassment policies for residents and fellows in prominent US hospitals. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2326-2328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05229-7

31. Hoff T, Scott S. The gendered realities and talent management imperatives of women physicians. Health Care Manage Rev. 2016;41(3):189-199. https://doi.org/10.1097/hmr.0000000000000069

32. Seemann NM, Webster F, Holden HA, et al. Women in academic surgery: why is the playing field still not level? Am J Surg. 2016;211(2):343-349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.08.036

33. Ahmadiyeh N, Cho NL, Kellogg KC, et al. Career satisfaction of women in surgery: perceptions, factors, and strategies. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(1):23-28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.08.011

34. Coleman VH, Power ML, Williams S, Carpentieri A, Schulkin J. Continuing professional development: racial and gender differences in obstetrics and gynecology residents’ perceptions of mentoring. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2005;25(4):268-277. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.40

35. Viglianti EM, Oliverio AL, Meeks LM. Sexual harassment and abuse: when the patient is the perpetrator. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):368-370. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31502-2

36. Killeen OJ, Bridges L. Solving the silence. JAMA. 2018;320(19):1979-1980. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.15686

37. Cowan AN. Inappropriate behavior by patients and their families-call it out. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1441. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4348

38. Shankar M, Albert T, Yee N, et al. Approaches for residents to address problematic patient behavior: before, during, and after the clinical encounter. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(4):371-374. https://doi.org/10.4300/jgme-d-19-00075.1

39. Eagly AH, Karau SJ. Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychol Rev. 2002;109(3):573. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.109.3.573

40. Ellinas EH, Fouad N, Byars-Winston A. Women and the decision to leave, linger, or lean in: predictors of intent to leave and aspirations to leadership and advancement in academic medicine. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2018;27(3):324-332. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2017.6457

1. More ES. Restoring the Balance: Women Physicians and the Profession of Medicine, 1850-1995. Harvard University Press; 1999.

2. Table A-7.2: Applicants, first-time applicants, acceptees, and matriculants to U.S. medical schools by sex, 2010-2011 through 2019-2020. Association of American Medical Colleges. Published October 4, 2019. Accessed December 13, 2019. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2019-10/2019_FACTS_Table_A-7.2.pdf