User login

Numeracy, Health Literacy, Cognition, and 30-Day Readmissions among Patients with Heart Failure

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.

Subjective health literacy was assessed by using the 3-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS).23 Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy. Objective health literacy was assessed with the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (sTOFHLA).24,25 Scores may be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36).

We assessed cognition by using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ).26 The SPMSQ, which describes a person’s capacity for memory, structured thought, and orientation, has been validated and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.27 Scores of 0 were considered to reflect intact cognition, and scores of 1 or more were considered to reflect any cognitive impairment, a scoring approach employed by other authors.28 We used this approach, rather than the traditional scoring system developed by Pfeiffer et al.26 (1975), because it would be the most sensitive to detect any cognitive impairment in the VICS cohort, which excluded those with severe cognition impairment, dementia, and delirium.

Covariates

During the hospitalization, participants completed an in-person interviewer-administered baseline assessment composed of demographic information, including age, self-reported race (white and nonwhite), educational attainment, home status (married, not married and living with someone, not married and living alone), and household income.

Clinical and diagnostic characteristics abstracted from the medical record included a medical history of HF, HF subtype (classified by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]), coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and comorbidity burden as summarized by the van Walraven-Elixhauser score.29,30 Depressive symptoms were assessed during the 2 weeks prior to the hospitalization by using the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire.31 Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptoms. Laboratory values included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin (g/dl), sodium (mg/L), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/ml) from the last laboratory draw before discharge. Smoking status was also assessed (current and former/nonsmokers).

Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay in days, number of prior admissions in the last year, and transfer to the intensive care unit during the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Pearson χ2 test were used to determine the association between patient characteristics and levels of numeracy, literacy, and cognition separately. The unadjusted relationship between patient characteristics and 30-day readmission was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank sums tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. In addition, a correlation matrix was performed to assess the correlations between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition (supplementary Figure 1).

To examine the association between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition and 30-day readmissions, a series of multivariable Poisson (log-linear) regression models were fit.32 Like other studies, numeracy, health literacy, and cognition were examined as categorical and continuous measures in models.33 Each model was modified with a sandwich estimator for robust standard errors. Log-linear models were chosen over logistic regression models for ease of interpretation because (exponentiated) parameters correspond to risk ratios (RRs) as opposed to odds ratios. Furthermore, the fitting challenges associated with log-linear models when predicted probabilities are near 0 or 1 were not present in these analyses. Redundancy analyses were conducted to ensure that independent variables were not highly correlated with a linear combination of the other independent variables. To avoid case-wise deletion of records with missing covariates, we employed multiple imputation with 10 imputation samples by using predictive mean matching.34,35 All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).36

RESULTS

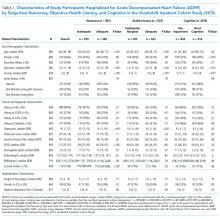

Overall, 883 patients were included in this analysis (supplementary Figure 2). Of the 883 participants, 46% were female and 76% were white (Table 1). Their median age was 60 years (interdecile range [IDR] 39-78) and the median educational attainment was 13.5 years (IDR 11-18).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of numeracy alongside literacy and cognition on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF. Overall, we found that 33.9% of participants had inadequate numeracy skills, and 24.6% had inadequate or marginal health literacy. In unadjusted and adjusted models, numeracy was not associated with 30-day readmission. Although (objective) low health literacy was associated with 30-day readmission in unadjusted models, it was not in adjusted models. Additionally, though 53% of participants had any cognitive impairment, readmission did not differ significantly by this factor. Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may be greater determinants of 30-day readmissions among patients hospitalized for ADHF.

Only 1 other study has examined the effect of numeracy on readmission risk among patients hospitalized for HF. In this multicenter prospective study, McNaughton et al.37 found low numeracy to be associated with higher odds of recidivism to the emergency department (ED) or hospital within 30 days. Our findings may differ from theirs for a few reasons. First, their study had a significantly higher percentage of individuals with low numeracy (55%) compared with ours (33.9%). This may be because they did not exclude individuals with severe cognitive impairment, and their patient population was of lower socioeconomic status (SES) than ours. Low SES is associated with higher 30-day readmissions among HF patients1,10 throughout the literature, and low numeracy is associated with low SES in other diseases.13,38,39 Finally, they studied recidivism, which was defined as any unplanned return to the ED or hospital within 30 days of the index ED visit for acute HF. We only focused on 30-day readmissions, which also may explain why our results differed.

We found that health literacy was not associated with 30-day readmissions, which is consistent with the literature. Although an association between health literacy and mortality exists among adults with HF, several studies have not found an association between health literacy and 30- and 90-day readmission among adults hospitalized for HF.8,9,40 Although we found an association between objective health literacy and 30-day readmission in unadjusted analyses, we did not find one in the multivariable model. This, along with our numeracy finding, suggests that numeracy and literacy may not be driving the 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF.

We examined cognition alongside numeracy and literacy because it is a prevalent condition among HF patients and because it is associated with adverse outcomes among patients with HF, including readmission.41,42 Studies have shown that HF preferentially affects certain cognitive domains,43 some of which are vital to HF self-care activities. We found that 53% of patients had any cognitive impairment, which is consistent with the literature of adults hospitalized for ADHF.44,45 Cognitive impairment was not, however, associated with 30-day readmissions. There may be a couple reasons for this. First, we measured cognitive impairment with the SPMSQ, which, although widely used and well-validated, does not assess executive function, the domain most commonly affected in HF patients with cognitive impairment.46 Second, patients with severe cognitive impairment and those with delirium were excluded from this study, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in readmission by this factor.

As in prior studies, we found that a history of DM and more hospitalizations in the prior year were independently associated with 30-day readmissions in fully adjusted models. Like other studies, in adjusted models, we found that LVEF and a history of HF were not independently associated with 30-day readmission.47-49 This, however, is not surprising because recent studies have shown that, although HF patients are at risk for multiple hospitalizations, early readmission after a hospitalization for ADHF specifically is often because of reasons unrelated to HF or a non-cardiovascular cause in general.50,51

Although a negative study, several important themes emerged. First, while we were able to assess numeracy, health literacy, and cognition, none of these measures were HF-specific. It is possible that we did not see an effect on readmission because our instruments failed to assess domains specific to HF, such as monitoring weight changes, following a low-salt diet, and interpreting blood pressure. Currently, however, no HF-specific objective numeracy measure exists. With respect to health literacy, only 1 HF-specific measure exists,52 although it was only recently developed and validated. Second, while numeracy may not be a driving influence of all-cause 30-day readmissions, it may be associated with other health behaviors and quality metrics that we did not examine here, such as self-care, medication adherence, and HF-specific readmissions. Third, it is likely that the progression of HF itself, as well as the clinical management of patients following discharge, contribute significantly to 30-day readmissions. Increased attention to predischarge processes for HF patients occurred at VUMC during the study period; close follow-up and evidence-directed therapies may have mitigated some of the expected associations. Finally, we were not able to assess numeracy of participants’ primary caregivers who may help patients at home, especially postdischarge. Though a number of studies have examined the role of family caregivers in the management of HF,53,54 none have examined numeracy levels of caregivers in the context of HF, and this may be worth doing in future studies.

Overall, our study has several strengths. The size of the cohort is large and there were high response rates during the follow-up period. Unlike other HF readmission studies, VICS accounts for readmissions to outside hospitals. Approximately 35% of all hospitalizations in VICS are to outside facilities. Thus, the ascertainment of readmissions to hospitals other than Vanderbilt is more comprehensive than if readmissions to VUMC were only considered. We were able to include a number of clinical comorbidities, laboratory and diagnostic tests from the index admission, and hospitalization characteristics in our analyses. Finally, we performed additional analyses to investigate the correlation between numeracy, literacy, and cognition; ultimately, we found that the majority of these correlations were weak, which supports our ability to study them simultaneously among VICS participants.

Nonetheless, we note some limitations. Although we captured readmissions to outside hospitals, the study took place at a single referral center in Tennessee. Though patients were diverse in age and comorbidities, they were mostly white and of higher SES. Finally, we used home status as a proxy for social support, which may underestimate the support that home care workers provide.

In conclusion, in this prospective longitudinal study of adults hospitalized with ADHF, inadequate numeracy was present in more than a third of patients, and low health literacy was present in roughly a quarter of patients. Neither numeracy nor health literacy, however, were associated with 30-day readmissions in adjusted analyses. Any cognitive impairment, although present in roughly one-half of patients, was not associated with 30-day readmission either. Our findings suggest that other influences may play a more dominant role in determining 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for ADHF than inadequate numeracy, low health literacy, or cognitive impairment as assessed here.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL109388) and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors’ funding sources did not participate in the planning, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the decision to submit for publication. Dr. Sterling is supported by T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Mixon has a VA Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award at the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs (CDA 12-168). This material was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on April 20, 2017, in Washington, DC.

Disclosure

Dr. Kripalani reports personal fees from Verustat, personal fees from SAI Interactive, and equity from Bioscape Digital, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Rothman and Dr. Wallston report personal fees from EdLogics outside of the submitted work. All of the other authors have nothing to disclose

1. Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch of Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1371-1386. PubMed

33. Bohannon AD, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Hanlon JT, Blazer DG. Relationship of race/ethnicity and blood pressure to change in cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):424-429. PubMed

38. Abdel-Kader K, Dew MA, Bhatnagar M, et al. Numeracy Skills in CKD: Correlates and Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(9):1566-1573. PubMed

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.

Subjective health literacy was assessed by using the 3-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS).23 Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy. Objective health literacy was assessed with the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (sTOFHLA).24,25 Scores may be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36).

We assessed cognition by using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ).26 The SPMSQ, which describes a person’s capacity for memory, structured thought, and orientation, has been validated and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.27 Scores of 0 were considered to reflect intact cognition, and scores of 1 or more were considered to reflect any cognitive impairment, a scoring approach employed by other authors.28 We used this approach, rather than the traditional scoring system developed by Pfeiffer et al.26 (1975), because it would be the most sensitive to detect any cognitive impairment in the VICS cohort, which excluded those with severe cognition impairment, dementia, and delirium.

Covariates

During the hospitalization, participants completed an in-person interviewer-administered baseline assessment composed of demographic information, including age, self-reported race (white and nonwhite), educational attainment, home status (married, not married and living with someone, not married and living alone), and household income.

Clinical and diagnostic characteristics abstracted from the medical record included a medical history of HF, HF subtype (classified by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]), coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and comorbidity burden as summarized by the van Walraven-Elixhauser score.29,30 Depressive symptoms were assessed during the 2 weeks prior to the hospitalization by using the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire.31 Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptoms. Laboratory values included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin (g/dl), sodium (mg/L), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/ml) from the last laboratory draw before discharge. Smoking status was also assessed (current and former/nonsmokers).

Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay in days, number of prior admissions in the last year, and transfer to the intensive care unit during the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Pearson χ2 test were used to determine the association between patient characteristics and levels of numeracy, literacy, and cognition separately. The unadjusted relationship between patient characteristics and 30-day readmission was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank sums tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. In addition, a correlation matrix was performed to assess the correlations between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition (supplementary Figure 1).

To examine the association between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition and 30-day readmissions, a series of multivariable Poisson (log-linear) regression models were fit.32 Like other studies, numeracy, health literacy, and cognition were examined as categorical and continuous measures in models.33 Each model was modified with a sandwich estimator for robust standard errors. Log-linear models were chosen over logistic regression models for ease of interpretation because (exponentiated) parameters correspond to risk ratios (RRs) as opposed to odds ratios. Furthermore, the fitting challenges associated with log-linear models when predicted probabilities are near 0 or 1 were not present in these analyses. Redundancy analyses were conducted to ensure that independent variables were not highly correlated with a linear combination of the other independent variables. To avoid case-wise deletion of records with missing covariates, we employed multiple imputation with 10 imputation samples by using predictive mean matching.34,35 All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).36

RESULTS

Overall, 883 patients were included in this analysis (supplementary Figure 2). Of the 883 participants, 46% were female and 76% were white (Table 1). Their median age was 60 years (interdecile range [IDR] 39-78) and the median educational attainment was 13.5 years (IDR 11-18).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of numeracy alongside literacy and cognition on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF. Overall, we found that 33.9% of participants had inadequate numeracy skills, and 24.6% had inadequate or marginal health literacy. In unadjusted and adjusted models, numeracy was not associated with 30-day readmission. Although (objective) low health literacy was associated with 30-day readmission in unadjusted models, it was not in adjusted models. Additionally, though 53% of participants had any cognitive impairment, readmission did not differ significantly by this factor. Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may be greater determinants of 30-day readmissions among patients hospitalized for ADHF.

Only 1 other study has examined the effect of numeracy on readmission risk among patients hospitalized for HF. In this multicenter prospective study, McNaughton et al.37 found low numeracy to be associated with higher odds of recidivism to the emergency department (ED) or hospital within 30 days. Our findings may differ from theirs for a few reasons. First, their study had a significantly higher percentage of individuals with low numeracy (55%) compared with ours (33.9%). This may be because they did not exclude individuals with severe cognitive impairment, and their patient population was of lower socioeconomic status (SES) than ours. Low SES is associated with higher 30-day readmissions among HF patients1,10 throughout the literature, and low numeracy is associated with low SES in other diseases.13,38,39 Finally, they studied recidivism, which was defined as any unplanned return to the ED or hospital within 30 days of the index ED visit for acute HF. We only focused on 30-day readmissions, which also may explain why our results differed.

We found that health literacy was not associated with 30-day readmissions, which is consistent with the literature. Although an association between health literacy and mortality exists among adults with HF, several studies have not found an association between health literacy and 30- and 90-day readmission among adults hospitalized for HF.8,9,40 Although we found an association between objective health literacy and 30-day readmission in unadjusted analyses, we did not find one in the multivariable model. This, along with our numeracy finding, suggests that numeracy and literacy may not be driving the 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF.

We examined cognition alongside numeracy and literacy because it is a prevalent condition among HF patients and because it is associated with adverse outcomes among patients with HF, including readmission.41,42 Studies have shown that HF preferentially affects certain cognitive domains,43 some of which are vital to HF self-care activities. We found that 53% of patients had any cognitive impairment, which is consistent with the literature of adults hospitalized for ADHF.44,45 Cognitive impairment was not, however, associated with 30-day readmissions. There may be a couple reasons for this. First, we measured cognitive impairment with the SPMSQ, which, although widely used and well-validated, does not assess executive function, the domain most commonly affected in HF patients with cognitive impairment.46 Second, patients with severe cognitive impairment and those with delirium were excluded from this study, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in readmission by this factor.

As in prior studies, we found that a history of DM and more hospitalizations in the prior year were independently associated with 30-day readmissions in fully adjusted models. Like other studies, in adjusted models, we found that LVEF and a history of HF were not independently associated with 30-day readmission.47-49 This, however, is not surprising because recent studies have shown that, although HF patients are at risk for multiple hospitalizations, early readmission after a hospitalization for ADHF specifically is often because of reasons unrelated to HF or a non-cardiovascular cause in general.50,51

Although a negative study, several important themes emerged. First, while we were able to assess numeracy, health literacy, and cognition, none of these measures were HF-specific. It is possible that we did not see an effect on readmission because our instruments failed to assess domains specific to HF, such as monitoring weight changes, following a low-salt diet, and interpreting blood pressure. Currently, however, no HF-specific objective numeracy measure exists. With respect to health literacy, only 1 HF-specific measure exists,52 although it was only recently developed and validated. Second, while numeracy may not be a driving influence of all-cause 30-day readmissions, it may be associated with other health behaviors and quality metrics that we did not examine here, such as self-care, medication adherence, and HF-specific readmissions. Third, it is likely that the progression of HF itself, as well as the clinical management of patients following discharge, contribute significantly to 30-day readmissions. Increased attention to predischarge processes for HF patients occurred at VUMC during the study period; close follow-up and evidence-directed therapies may have mitigated some of the expected associations. Finally, we were not able to assess numeracy of participants’ primary caregivers who may help patients at home, especially postdischarge. Though a number of studies have examined the role of family caregivers in the management of HF,53,54 none have examined numeracy levels of caregivers in the context of HF, and this may be worth doing in future studies.

Overall, our study has several strengths. The size of the cohort is large and there were high response rates during the follow-up period. Unlike other HF readmission studies, VICS accounts for readmissions to outside hospitals. Approximately 35% of all hospitalizations in VICS are to outside facilities. Thus, the ascertainment of readmissions to hospitals other than Vanderbilt is more comprehensive than if readmissions to VUMC were only considered. We were able to include a number of clinical comorbidities, laboratory and diagnostic tests from the index admission, and hospitalization characteristics in our analyses. Finally, we performed additional analyses to investigate the correlation between numeracy, literacy, and cognition; ultimately, we found that the majority of these correlations were weak, which supports our ability to study them simultaneously among VICS participants.

Nonetheless, we note some limitations. Although we captured readmissions to outside hospitals, the study took place at a single referral center in Tennessee. Though patients were diverse in age and comorbidities, they were mostly white and of higher SES. Finally, we used home status as a proxy for social support, which may underestimate the support that home care workers provide.

In conclusion, in this prospective longitudinal study of adults hospitalized with ADHF, inadequate numeracy was present in more than a third of patients, and low health literacy was present in roughly a quarter of patients. Neither numeracy nor health literacy, however, were associated with 30-day readmissions in adjusted analyses. Any cognitive impairment, although present in roughly one-half of patients, was not associated with 30-day readmission either. Our findings suggest that other influences may play a more dominant role in determining 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for ADHF than inadequate numeracy, low health literacy, or cognitive impairment as assessed here.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL109388) and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors’ funding sources did not participate in the planning, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the decision to submit for publication. Dr. Sterling is supported by T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Mixon has a VA Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award at the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs (CDA 12-168). This material was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on April 20, 2017, in Washington, DC.

Disclosure

Dr. Kripalani reports personal fees from Verustat, personal fees from SAI Interactive, and equity from Bioscape Digital, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Rothman and Dr. Wallston report personal fees from EdLogics outside of the submitted work. All of the other authors have nothing to disclose

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.

Subjective health literacy was assessed by using the 3-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS).23 Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy. Objective health literacy was assessed with the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (sTOFHLA).24,25 Scores may be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36).

We assessed cognition by using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ).26 The SPMSQ, which describes a person’s capacity for memory, structured thought, and orientation, has been validated and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.27 Scores of 0 were considered to reflect intact cognition, and scores of 1 or more were considered to reflect any cognitive impairment, a scoring approach employed by other authors.28 We used this approach, rather than the traditional scoring system developed by Pfeiffer et al.26 (1975), because it would be the most sensitive to detect any cognitive impairment in the VICS cohort, which excluded those with severe cognition impairment, dementia, and delirium.

Covariates

During the hospitalization, participants completed an in-person interviewer-administered baseline assessment composed of demographic information, including age, self-reported race (white and nonwhite), educational attainment, home status (married, not married and living with someone, not married and living alone), and household income.

Clinical and diagnostic characteristics abstracted from the medical record included a medical history of HF, HF subtype (classified by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]), coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and comorbidity burden as summarized by the van Walraven-Elixhauser score.29,30 Depressive symptoms were assessed during the 2 weeks prior to the hospitalization by using the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire.31 Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptoms. Laboratory values included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin (g/dl), sodium (mg/L), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/ml) from the last laboratory draw before discharge. Smoking status was also assessed (current and former/nonsmokers).

Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay in days, number of prior admissions in the last year, and transfer to the intensive care unit during the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Pearson χ2 test were used to determine the association between patient characteristics and levels of numeracy, literacy, and cognition separately. The unadjusted relationship between patient characteristics and 30-day readmission was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank sums tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. In addition, a correlation matrix was performed to assess the correlations between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition (supplementary Figure 1).

To examine the association between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition and 30-day readmissions, a series of multivariable Poisson (log-linear) regression models were fit.32 Like other studies, numeracy, health literacy, and cognition were examined as categorical and continuous measures in models.33 Each model was modified with a sandwich estimator for robust standard errors. Log-linear models were chosen over logistic regression models for ease of interpretation because (exponentiated) parameters correspond to risk ratios (RRs) as opposed to odds ratios. Furthermore, the fitting challenges associated with log-linear models when predicted probabilities are near 0 or 1 were not present in these analyses. Redundancy analyses were conducted to ensure that independent variables were not highly correlated with a linear combination of the other independent variables. To avoid case-wise deletion of records with missing covariates, we employed multiple imputation with 10 imputation samples by using predictive mean matching.34,35 All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).36

RESULTS

Overall, 883 patients were included in this analysis (supplementary Figure 2). Of the 883 participants, 46% were female and 76% were white (Table 1). Their median age was 60 years (interdecile range [IDR] 39-78) and the median educational attainment was 13.5 years (IDR 11-18).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of numeracy alongside literacy and cognition on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF. Overall, we found that 33.9% of participants had inadequate numeracy skills, and 24.6% had inadequate or marginal health literacy. In unadjusted and adjusted models, numeracy was not associated with 30-day readmission. Although (objective) low health literacy was associated with 30-day readmission in unadjusted models, it was not in adjusted models. Additionally, though 53% of participants had any cognitive impairment, readmission did not differ significantly by this factor. Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may be greater determinants of 30-day readmissions among patients hospitalized for ADHF.

Only 1 other study has examined the effect of numeracy on readmission risk among patients hospitalized for HF. In this multicenter prospective study, McNaughton et al.37 found low numeracy to be associated with higher odds of recidivism to the emergency department (ED) or hospital within 30 days. Our findings may differ from theirs for a few reasons. First, their study had a significantly higher percentage of individuals with low numeracy (55%) compared with ours (33.9%). This may be because they did not exclude individuals with severe cognitive impairment, and their patient population was of lower socioeconomic status (SES) than ours. Low SES is associated with higher 30-day readmissions among HF patients1,10 throughout the literature, and low numeracy is associated with low SES in other diseases.13,38,39 Finally, they studied recidivism, which was defined as any unplanned return to the ED or hospital within 30 days of the index ED visit for acute HF. We only focused on 30-day readmissions, which also may explain why our results differed.

We found that health literacy was not associated with 30-day readmissions, which is consistent with the literature. Although an association between health literacy and mortality exists among adults with HF, several studies have not found an association between health literacy and 30- and 90-day readmission among adults hospitalized for HF.8,9,40 Although we found an association between objective health literacy and 30-day readmission in unadjusted analyses, we did not find one in the multivariable model. This, along with our numeracy finding, suggests that numeracy and literacy may not be driving the 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF.

We examined cognition alongside numeracy and literacy because it is a prevalent condition among HF patients and because it is associated with adverse outcomes among patients with HF, including readmission.41,42 Studies have shown that HF preferentially affects certain cognitive domains,43 some of which are vital to HF self-care activities. We found that 53% of patients had any cognitive impairment, which is consistent with the literature of adults hospitalized for ADHF.44,45 Cognitive impairment was not, however, associated with 30-day readmissions. There may be a couple reasons for this. First, we measured cognitive impairment with the SPMSQ, which, although widely used and well-validated, does not assess executive function, the domain most commonly affected in HF patients with cognitive impairment.46 Second, patients with severe cognitive impairment and those with delirium were excluded from this study, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in readmission by this factor.

As in prior studies, we found that a history of DM and more hospitalizations in the prior year were independently associated with 30-day readmissions in fully adjusted models. Like other studies, in adjusted models, we found that LVEF and a history of HF were not independently associated with 30-day readmission.47-49 This, however, is not surprising because recent studies have shown that, although HF patients are at risk for multiple hospitalizations, early readmission after a hospitalization for ADHF specifically is often because of reasons unrelated to HF or a non-cardiovascular cause in general.50,51

Although a negative study, several important themes emerged. First, while we were able to assess numeracy, health literacy, and cognition, none of these measures were HF-specific. It is possible that we did not see an effect on readmission because our instruments failed to assess domains specific to HF, such as monitoring weight changes, following a low-salt diet, and interpreting blood pressure. Currently, however, no HF-specific objective numeracy measure exists. With respect to health literacy, only 1 HF-specific measure exists,52 although it was only recently developed and validated. Second, while numeracy may not be a driving influence of all-cause 30-day readmissions, it may be associated with other health behaviors and quality metrics that we did not examine here, such as self-care, medication adherence, and HF-specific readmissions. Third, it is likely that the progression of HF itself, as well as the clinical management of patients following discharge, contribute significantly to 30-day readmissions. Increased attention to predischarge processes for HF patients occurred at VUMC during the study period; close follow-up and evidence-directed therapies may have mitigated some of the expected associations. Finally, we were not able to assess numeracy of participants’ primary caregivers who may help patients at home, especially postdischarge. Though a number of studies have examined the role of family caregivers in the management of HF,53,54 none have examined numeracy levels of caregivers in the context of HF, and this may be worth doing in future studies.

Overall, our study has several strengths. The size of the cohort is large and there were high response rates during the follow-up period. Unlike other HF readmission studies, VICS accounts for readmissions to outside hospitals. Approximately 35% of all hospitalizations in VICS are to outside facilities. Thus, the ascertainment of readmissions to hospitals other than Vanderbilt is more comprehensive than if readmissions to VUMC were only considered. We were able to include a number of clinical comorbidities, laboratory and diagnostic tests from the index admission, and hospitalization characteristics in our analyses. Finally, we performed additional analyses to investigate the correlation between numeracy, literacy, and cognition; ultimately, we found that the majority of these correlations were weak, which supports our ability to study them simultaneously among VICS participants.

Nonetheless, we note some limitations. Although we captured readmissions to outside hospitals, the study took place at a single referral center in Tennessee. Though patients were diverse in age and comorbidities, they were mostly white and of higher SES. Finally, we used home status as a proxy for social support, which may underestimate the support that home care workers provide.

In conclusion, in this prospective longitudinal study of adults hospitalized with ADHF, inadequate numeracy was present in more than a third of patients, and low health literacy was present in roughly a quarter of patients. Neither numeracy nor health literacy, however, were associated with 30-day readmissions in adjusted analyses. Any cognitive impairment, although present in roughly one-half of patients, was not associated with 30-day readmission either. Our findings suggest that other influences may play a more dominant role in determining 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for ADHF than inadequate numeracy, low health literacy, or cognitive impairment as assessed here.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL109388) and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors’ funding sources did not participate in the planning, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the decision to submit for publication. Dr. Sterling is supported by T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Mixon has a VA Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award at the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs (CDA 12-168). This material was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on April 20, 2017, in Washington, DC.

Disclosure

Dr. Kripalani reports personal fees from Verustat, personal fees from SAI Interactive, and equity from Bioscape Digital, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Rothman and Dr. Wallston report personal fees from EdLogics outside of the submitted work. All of the other authors have nothing to disclose

1. Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch of Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1371-1386. PubMed

33. Bohannon AD, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Hanlon JT, Blazer DG. Relationship of race/ethnicity and blood pressure to change in cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):424-429. PubMed

38. Abdel-Kader K, Dew MA, Bhatnagar M, et al. Numeracy Skills in CKD: Correlates and Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(9):1566-1573. PubMed

1. Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch of Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1371-1386. PubMed

33. Bohannon AD, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Hanlon JT, Blazer DG. Relationship of race/ethnicity and blood pressure to change in cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):424-429. PubMed

38. Abdel-Kader K, Dew MA, Bhatnagar M, et al. Numeracy Skills in CKD: Correlates and Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(9):1566-1573. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Making the most of the time we have

Mr P was my last patient of the day, as usual. A busy executive, he always scheduled visits late to minimize waiting. When he had first come to see me 6 months ago, he had felt pretty bad. We discovered he had uncontrolled diabetes. He had suspected as much but waited to seek medical attention until the exhaustion interfered with work.

He gladly took the medicines I recommended. He and the diabetes educator strategized, but anything that required extra time was off the table. They focused on how to make better fast-food choices than his favorite baconcheese Whoppers.

I was therefore a bit surprised when he announced at this visit that he wanted to start an exercise program. “Mr P,” I said, “you work from 7 AM to 8 PM and commute 45 minutes. When will you exercise?” He said seriously, “After I get home.” I shook my head as I ordered a stress test before letting him loose on his exercise bike. Clearly, he wanted to do what I recommended, but I wondered, when?

A few months later, Mr P returned, sheepishly admitting he hadn’t started exercising. Although his blood pressure and sugars were under excellent control, he felt tired and had gained weight on the medication. Although I feel frustrated when patients return not having followed my advice, in this case I had expected that Mr P wouldn’t exercise. I looked at the long list of diabetes self-care tasks and I realized he, and probably most of my patients, couldn’t possibly have time to accomplish it all. I also noted that some recommendations likely would improve his risk-factor profile more than others. For example, he had good sensation in his feet, so spending a lot of time on foot care at this point was not as important as increasing physical activity.

We discussed his most important diabetes-related goals. He wanted to feel better and minimize risk for heart attack or stroke. Then I asked him how much time he could realistically devote to his diabetes care. He hesitated and watched my face tentatively for a reaction as he admitted it was probably no more than 30 minutes daily. This made my job a lot easier. We spent the rest of the visit in a practical discussion about how to spend that half hour, focusing on diet and exercise. I reassured him that monitoring sugar less often was OK at this point. Mr P left the office with a bounce in his gait.

I mulled over this visit. I certainly felt a lot better than I had at the previous visit, and I knew he did too. I liked this idea of prioritizing tasks with him; if we didn’t do it this way, he would set his own priorities. Without my input, his choices might not maximize the impact on his health. But I was struck by how very little guidance there is for physicians and patients in conducting such discussions. The guidelines I knew of detailed the many elements of comprehensive care without prioritization. Although costeffectiveness analyses could potentially help, most of these focus on individual medications, and few compare numerous interventions side by side. It also struck me that, as the time requirements of self-care tasks become a rate-limiting step, “time-effectiveness” analysis might not be such a bad idea.

Furthermore, I was a little nervous about telling Mr P about the limits of what we could do. How was I going to broach this subject? How was he going to react? I worried about how much important information was currently missing. What is the comparative impact on quality of life, for example, of the meal exchange program (and the attendant time it takes to follow it), exercising, or controlling blood pressure through medications? How can I communicate the relative benefits of each of these if they are not even quantified and systematically compared?

At our next visit, Mr P was genuinely excited. He had managed to incorporate many suggestions from our last visit, although he quickly admitted to having trouble with the diet part. One of his favorite new habits was a brisk walk around the block to one of the street vendors to buy his lunch. Now we had to work on his favorite choice, a Philly cheese steak.

With some trepidation, I brought up the issue of his risks and how our efforts could not eliminate them. In fact, for many of the interventions I was recommending, I couldn’t tell him how much benefit he could expect to derive. He looked at me, puzzled. “I know that!” he exclaimed. He quickly added that he appreciated the information, even if science doesn’t yet provide all the answers.

Soon after this, I changed jobs. I ran into Mr P before I left, and he accosted me about my leaving. “How could you desert me like this?” he half-joked. We talked a bit, and then, obviously somewhat uncomfortable with what he was about to say, he blurted out, “You know, I’ll miss you. You never made me feel too guilty, though God knows I probably should. It’s refreshing to have a doctor who’s a little more realistic and understanding of my situation.”

“Thanks, Mr P. It was a pleasure working with you,” I answered. “You helped me think through some issues, and I wanted to thank you for that. I’ll miss you, too.”

Correspondence

Monika M. Safford, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, MT 643, 1717 11th Avenue South, Birmingham, AL 35294-4410. Email: [email protected].

Mr P was my last patient of the day, as usual. A busy executive, he always scheduled visits late to minimize waiting. When he had first come to see me 6 months ago, he had felt pretty bad. We discovered he had uncontrolled diabetes. He had suspected as much but waited to seek medical attention until the exhaustion interfered with work.

He gladly took the medicines I recommended. He and the diabetes educator strategized, but anything that required extra time was off the table. They focused on how to make better fast-food choices than his favorite baconcheese Whoppers.

I was therefore a bit surprised when he announced at this visit that he wanted to start an exercise program. “Mr P,” I said, “you work from 7 AM to 8 PM and commute 45 minutes. When will you exercise?” He said seriously, “After I get home.” I shook my head as I ordered a stress test before letting him loose on his exercise bike. Clearly, he wanted to do what I recommended, but I wondered, when?

A few months later, Mr P returned, sheepishly admitting he hadn’t started exercising. Although his blood pressure and sugars were under excellent control, he felt tired and had gained weight on the medication. Although I feel frustrated when patients return not having followed my advice, in this case I had expected that Mr P wouldn’t exercise. I looked at the long list of diabetes self-care tasks and I realized he, and probably most of my patients, couldn’t possibly have time to accomplish it all. I also noted that some recommendations likely would improve his risk-factor profile more than others. For example, he had good sensation in his feet, so spending a lot of time on foot care at this point was not as important as increasing physical activity.

We discussed his most important diabetes-related goals. He wanted to feel better and minimize risk for heart attack or stroke. Then I asked him how much time he could realistically devote to his diabetes care. He hesitated and watched my face tentatively for a reaction as he admitted it was probably no more than 30 minutes daily. This made my job a lot easier. We spent the rest of the visit in a practical discussion about how to spend that half hour, focusing on diet and exercise. I reassured him that monitoring sugar less often was OK at this point. Mr P left the office with a bounce in his gait.

I mulled over this visit. I certainly felt a lot better than I had at the previous visit, and I knew he did too. I liked this idea of prioritizing tasks with him; if we didn’t do it this way, he would set his own priorities. Without my input, his choices might not maximize the impact on his health. But I was struck by how very little guidance there is for physicians and patients in conducting such discussions. The guidelines I knew of detailed the many elements of comprehensive care without prioritization. Although costeffectiveness analyses could potentially help, most of these focus on individual medications, and few compare numerous interventions side by side. It also struck me that, as the time requirements of self-care tasks become a rate-limiting step, “time-effectiveness” analysis might not be such a bad idea.

Furthermore, I was a little nervous about telling Mr P about the limits of what we could do. How was I going to broach this subject? How was he going to react? I worried about how much important information was currently missing. What is the comparative impact on quality of life, for example, of the meal exchange program (and the attendant time it takes to follow it), exercising, or controlling blood pressure through medications? How can I communicate the relative benefits of each of these if they are not even quantified and systematically compared?

At our next visit, Mr P was genuinely excited. He had managed to incorporate many suggestions from our last visit, although he quickly admitted to having trouble with the diet part. One of his favorite new habits was a brisk walk around the block to one of the street vendors to buy his lunch. Now we had to work on his favorite choice, a Philly cheese steak.

With some trepidation, I brought up the issue of his risks and how our efforts could not eliminate them. In fact, for many of the interventions I was recommending, I couldn’t tell him how much benefit he could expect to derive. He looked at me, puzzled. “I know that!” he exclaimed. He quickly added that he appreciated the information, even if science doesn’t yet provide all the answers.

Soon after this, I changed jobs. I ran into Mr P before I left, and he accosted me about my leaving. “How could you desert me like this?” he half-joked. We talked a bit, and then, obviously somewhat uncomfortable with what he was about to say, he blurted out, “You know, I’ll miss you. You never made me feel too guilty, though God knows I probably should. It’s refreshing to have a doctor who’s a little more realistic and understanding of my situation.”

“Thanks, Mr P. It was a pleasure working with you,” I answered. “You helped me think through some issues, and I wanted to thank you for that. I’ll miss you, too.”

Correspondence

Monika M. Safford, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, MT 643, 1717 11th Avenue South, Birmingham, AL 35294-4410. Email: [email protected].

Mr P was my last patient of the day, as usual. A busy executive, he always scheduled visits late to minimize waiting. When he had first come to see me 6 months ago, he had felt pretty bad. We discovered he had uncontrolled diabetes. He had suspected as much but waited to seek medical attention until the exhaustion interfered with work.

He gladly took the medicines I recommended. He and the diabetes educator strategized, but anything that required extra time was off the table. They focused on how to make better fast-food choices than his favorite baconcheese Whoppers.

I was therefore a bit surprised when he announced at this visit that he wanted to start an exercise program. “Mr P,” I said, “you work from 7 AM to 8 PM and commute 45 minutes. When will you exercise?” He said seriously, “After I get home.” I shook my head as I ordered a stress test before letting him loose on his exercise bike. Clearly, he wanted to do what I recommended, but I wondered, when?

A few months later, Mr P returned, sheepishly admitting he hadn’t started exercising. Although his blood pressure and sugars were under excellent control, he felt tired and had gained weight on the medication. Although I feel frustrated when patients return not having followed my advice, in this case I had expected that Mr P wouldn’t exercise. I looked at the long list of diabetes self-care tasks and I realized he, and probably most of my patients, couldn’t possibly have time to accomplish it all. I also noted that some recommendations likely would improve his risk-factor profile more than others. For example, he had good sensation in his feet, so spending a lot of time on foot care at this point was not as important as increasing physical activity.

We discussed his most important diabetes-related goals. He wanted to feel better and minimize risk for heart attack or stroke. Then I asked him how much time he could realistically devote to his diabetes care. He hesitated and watched my face tentatively for a reaction as he admitted it was probably no more than 30 minutes daily. This made my job a lot easier. We spent the rest of the visit in a practical discussion about how to spend that half hour, focusing on diet and exercise. I reassured him that monitoring sugar less often was OK at this point. Mr P left the office with a bounce in his gait.

I mulled over this visit. I certainly felt a lot better than I had at the previous visit, and I knew he did too. I liked this idea of prioritizing tasks with him; if we didn’t do it this way, he would set his own priorities. Without my input, his choices might not maximize the impact on his health. But I was struck by how very little guidance there is for physicians and patients in conducting such discussions. The guidelines I knew of detailed the many elements of comprehensive care without prioritization. Although costeffectiveness analyses could potentially help, most of these focus on individual medications, and few compare numerous interventions side by side. It also struck me that, as the time requirements of self-care tasks become a rate-limiting step, “time-effectiveness” analysis might not be such a bad idea.

Furthermore, I was a little nervous about telling Mr P about the limits of what we could do. How was I going to broach this subject? How was he going to react? I worried about how much important information was currently missing. What is the comparative impact on quality of life, for example, of the meal exchange program (and the attendant time it takes to follow it), exercising, or controlling blood pressure through medications? How can I communicate the relative benefits of each of these if they are not even quantified and systematically compared?

At our next visit, Mr P was genuinely excited. He had managed to incorporate many suggestions from our last visit, although he quickly admitted to having trouble with the diet part. One of his favorite new habits was a brisk walk around the block to one of the street vendors to buy his lunch. Now we had to work on his favorite choice, a Philly cheese steak.

With some trepidation, I brought up the issue of his risks and how our efforts could not eliminate them. In fact, for many of the interventions I was recommending, I couldn’t tell him how much benefit he could expect to derive. He looked at me, puzzled. “I know that!” he exclaimed. He quickly added that he appreciated the information, even if science doesn’t yet provide all the answers.

Soon after this, I changed jobs. I ran into Mr P before I left, and he accosted me about my leaving. “How could you desert me like this?” he half-joked. We talked a bit, and then, obviously somewhat uncomfortable with what he was about to say, he blurted out, “You know, I’ll miss you. You never made me feel too guilty, though God knows I probably should. It’s refreshing to have a doctor who’s a little more realistic and understanding of my situation.”

“Thanks, Mr P. It was a pleasure working with you,” I answered. “You helped me think through some issues, and I wanted to thank you for that. I’ll miss you, too.”

Correspondence

Monika M. Safford, MD, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Medicine, MT 643, 1717 11th Avenue South, Birmingham, AL 35294-4410. Email: [email protected].