User login

An On-Treatment Analysis of the MARQUIS Study: Interventions to Improve Inpatient Medication Reconciliation

Unintentional medication discrepancies in the hospital setting are common and contribute to adverse drug events, resulting in patient harm.1 Discrepancies can be resolved by implementing high-quality medication reconciliation, but there are insufficient data to guide hospitals as to which interventions are most effective at improving medication reconciliation processes and reducing harm.2 We recently reported that implementation of a best practices toolkit reduced total medication discrepancies in the Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS).3 This report describes the effect of individual toolkit components on rates of medication discrepancies with the potential for patient harm.

METHODS

Detailed descriptions of the intervention toolkit and study design of MARQUIS are published.4,5 Briefly, MARQUIS was a pragmatic, mentored, quality improvement (QI) study in which five hospitals in the United States implemented interventions from a best practices toolkit to improve medication reconciliation on noncritical care medical and surgical units from September 2011 to July 2014. We used a mentored implementation approach, in which each site identified the leaders of their local quality improvement team (ie, mentees) who received mentorship from a trained physician with QI and medication safety experience.6 Mentors conducted monthly calls with their mentees and two site visits. Sites adapted and implemented one or more components from the MARQUIS toolkit, a compilation of evidence-based best practices in medication reconciliation.5,7

The primary outcome was unintentional medication discrepancies in admission and discharge orders with the potential for causing harm, as previously described.4 Trained study pharmacists at each site took “gold standard” medication histories on a random sample of up to 22 patients per month. These medications were then compared with admission and discharge medication orders, and all unintentional discrepancies were identified. The discrepancies were then adjudicated by physicians blinded to the treatment arm, who confirmed whether discrepancies were unintentional and carried the potential for patient harm.

We employed a modification of a stepped wedge methodology to measure the incremental effect of implementing nine different intervention components, introduced at different sites over the course of the study, on the number of potentially harmful discrepancies per patient. These analyses were restricted to the postimplementation period on hospital units that implemented at least one intervention. All interventions conducted at each site were categorized by component, including dates of implementation. Each intervention component could be applied more than once per site (eg, when involving a new group of providers) or implemented on a new hospital unit or service, in which case, all dates were included in the analysis. We conducted a multivariable Poisson regression (with time divided into months) adjusted for patient factors, season, and site, with the number of potentially harmful discrepancies as the dependent variable, and the total number of gold standard medications as a model offset. The model was designed to analyze changes in the y-intercept each time an intervention component was either implemented or spread and assumed the change in the y-intercept was the same for each of these events for any given component. The model also assumes that combinations of interventions had independent additive effects.

RESULTS

Across the five participating sites, 1,648 patients were enrolled from September 2011 to July 2014. This number included 613 patients during the preimplementation period and 1,035 patients during the postimplementation period, of which 791 were on intervention units and comprised the study population. Table 1 displays the intervention components implemented by site. Sites implemented between one and seven components. The most frequently implemented intervention component was training existing staff to take the best possible medication histories (BPMHs), implemented at four sites. The regression results are displayed in Table 2. Three interventions were associated with significant decreases in potentially harmful discrepancy rates: (1) clearly defining roles and responsibilities and communicating this with clinical staff (hazard ratio [HR] 0.53, 95% CI: 0.32–0.87); (2) training existing staff to perform discharge medication reconciliation and patient counseling (HR 0.64, 95% CI: 0.46–0.89); and (3) hiring additional staff to perform discharge medication reconciliation and patient counseling (HR 0.48, 95% CI: 0.31–0.77). Two interventions were associated with significant increases in potentially harmful discrepancy rates: training existing staff to take BPMHs (HR 1.38, 95% CI: 1.21–1.57) and implementing a new electronic health record (EHR; HR 2.21, 95% CI: 1.64–2.97).

DISCUSSION

We noted that three intervention components were associated with decreased rates of unintentional medication discrepancies with potential for harm, whereas two were associated with increased rates. The components with a beneficial effect were not surprising. A prior qualitative study demonstrated the confusion related to clinicians’ roles and responsibilities during medication reconciliation; therefore, clear delineations should reduce rework and improve the medication reconciliation process.8 Other studies have shown the benefits of pharmacist involvement in the inpatient setting, particularly in reducing errors at discharge.9 However, we did not anticipate that training staff to take BPMHs would be detrimental. Possible reasons for this finding that are based on direct observations by mentors at site visits or noted during monthly calls include (1) training personnel on this task without certification of competency may not sufficiently improve their skills, leading instead to diffusion of responsibility; (2) training personnel without sufficient time to perform the task well (eg, frontline nurses with many other responsibilities) may be counterproductive compared with training a few personnel with time dedicated to this task; and (3) training existing personnel in history-taking may have been used to delay the necessary hiring of more staff to take BPMHs. Future studies could address several of these shortcomings in both the design and implementation of medication history-training intervention components.

Several reasons may explain the association we found between implementing a new EHR and increased rates of discrepancies. Based on mentors’ experiences, we suspect it is because sitewide EHR implementation requires significant resources, time, and effort. Therefore, sitewide EHR implementation pulls attention away from a focus on medication safety

Our study has several limitations. We conducted an on-treatment analysis, which may be confounded by characteristics of sites that chose to implement different intervention components; however, we adjusted for sites in the analysis. Some results are based on a limited number of sites implementing an intervention component (eg, defining roles and responsibilities). Although this was a longitudinal study, and we adjusted for seasonal effects, it is possible that temporal trends and cointerventions confounded our results. The adjudication of discrepancies for the potential for harm was somewhat subjective, although we used a rigorous process to ensure the reliability of adjudication, as in prior studies.3,14 As in the main analysis of the MARQUIS study, this analysis did not measure intervention fidelity.

Based on these analyses and the literature base, we recommend that hospitals focus first on hiring and training dedicated staff (usually pharmacists) to assist with medication reconciliation at discharge.7 Hospitals should also be aware of potential increases in medication discrepancies when implementing a large vendor EHR across their institution. Further work is needed on the best ways to mitigate these adverse effects, at both the design and local site levels. Finally, the effect of medication history training on discrepancies warrants further study.

Disclosures

SK has served as a consultant to Verustat, a remote health monitoring company. All other authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interests.

Funding

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant number: R18 HS019598). JLS has received funding from (1) Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals for an investigator-initiated study of opioid-related adverse drug events in postsurgical patients; (2) Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield for an honorarium and travel expenses for workshop on medication reconciliation; (3) Island Peer Review Organization for honorarium and travel expenses for workshop on medication reconciliation; and, (4) Portola Pharmaceuticals for investigator-initiated study of inpatients who decline subcutaneous medications for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. ASM was funded by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (12-168).

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01337063

1. Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(4):424-429. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.4.424.

2. Kaboli PJ, Fernandes O. Medication reconciliation: moving forward. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1069-1070. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2667. PubMed

3. Schnipper JL, Mixon A, Stein J, et al. Effects of a multifaceted medication reconciliation quality improvement intervention on patient safety: final results of the MARQUIS study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(12):954-964. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008233.

4. Salanitro AH, Kripalani S, Resnic J, et al. Rational and design of the Multicenter Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS). BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:230. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-230.

5. Mueller SK, Kripalani S, Stein J, et al. Development of a toolkit to disseminate best practices in inpatient medication reconciliation. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39(8):371-382. https://10.1016/S1553-7250(13)39051-5.

6. Maynard GA, Budnitz TL, Nickel WK, et al. 2011 John M. Eisenberg patient safety and quality awards. Mentored implementation: building leaders and achieving results through a collaborative improvement model. Innovation in patient safety and quality at the national level. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(7):301-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(12)38040-9.

7. Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1057-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246.

8. Vogelsmeier A, Pepper GA, Oderda L, Weir C. Medication reconciliation: a qualitative analysis of clinicians’ perceptions. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(4):419-430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.08.002.

9. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, Schnipper JL. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):955-964. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.9.955.

10. Plaisant C, Wu J, Hettinger AZ, Powsner S, Shneiderman B. Novel user interface design for medication reconciliation: an evaluation of Twinlist. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(2):340-349. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocu021.

11. Bassi J, Lau F, Bardal S. Use of information technology in medication reconciliation: a scoping review. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(5):885-897. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1M699.

12. Marien S, Krug B, Spinewine A. Electronic tools to support medication reconciliation: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(1):227-240. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocw068.

13. Agrawal A. Medication errors: prevention using information technology systems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(6):681-686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03427.x.

14. Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1414-1422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0687-9.

Unintentional medication discrepancies in the hospital setting are common and contribute to adverse drug events, resulting in patient harm.1 Discrepancies can be resolved by implementing high-quality medication reconciliation, but there are insufficient data to guide hospitals as to which interventions are most effective at improving medication reconciliation processes and reducing harm.2 We recently reported that implementation of a best practices toolkit reduced total medication discrepancies in the Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS).3 This report describes the effect of individual toolkit components on rates of medication discrepancies with the potential for patient harm.

METHODS

Detailed descriptions of the intervention toolkit and study design of MARQUIS are published.4,5 Briefly, MARQUIS was a pragmatic, mentored, quality improvement (QI) study in which five hospitals in the United States implemented interventions from a best practices toolkit to improve medication reconciliation on noncritical care medical and surgical units from September 2011 to July 2014. We used a mentored implementation approach, in which each site identified the leaders of their local quality improvement team (ie, mentees) who received mentorship from a trained physician with QI and medication safety experience.6 Mentors conducted monthly calls with their mentees and two site visits. Sites adapted and implemented one or more components from the MARQUIS toolkit, a compilation of evidence-based best practices in medication reconciliation.5,7

The primary outcome was unintentional medication discrepancies in admission and discharge orders with the potential for causing harm, as previously described.4 Trained study pharmacists at each site took “gold standard” medication histories on a random sample of up to 22 patients per month. These medications were then compared with admission and discharge medication orders, and all unintentional discrepancies were identified. The discrepancies were then adjudicated by physicians blinded to the treatment arm, who confirmed whether discrepancies were unintentional and carried the potential for patient harm.

We employed a modification of a stepped wedge methodology to measure the incremental effect of implementing nine different intervention components, introduced at different sites over the course of the study, on the number of potentially harmful discrepancies per patient. These analyses were restricted to the postimplementation period on hospital units that implemented at least one intervention. All interventions conducted at each site were categorized by component, including dates of implementation. Each intervention component could be applied more than once per site (eg, when involving a new group of providers) or implemented on a new hospital unit or service, in which case, all dates were included in the analysis. We conducted a multivariable Poisson regression (with time divided into months) adjusted for patient factors, season, and site, with the number of potentially harmful discrepancies as the dependent variable, and the total number of gold standard medications as a model offset. The model was designed to analyze changes in the y-intercept each time an intervention component was either implemented or spread and assumed the change in the y-intercept was the same for each of these events for any given component. The model also assumes that combinations of interventions had independent additive effects.

RESULTS

Across the five participating sites, 1,648 patients were enrolled from September 2011 to July 2014. This number included 613 patients during the preimplementation period and 1,035 patients during the postimplementation period, of which 791 were on intervention units and comprised the study population. Table 1 displays the intervention components implemented by site. Sites implemented between one and seven components. The most frequently implemented intervention component was training existing staff to take the best possible medication histories (BPMHs), implemented at four sites. The regression results are displayed in Table 2. Three interventions were associated with significant decreases in potentially harmful discrepancy rates: (1) clearly defining roles and responsibilities and communicating this with clinical staff (hazard ratio [HR] 0.53, 95% CI: 0.32–0.87); (2) training existing staff to perform discharge medication reconciliation and patient counseling (HR 0.64, 95% CI: 0.46–0.89); and (3) hiring additional staff to perform discharge medication reconciliation and patient counseling (HR 0.48, 95% CI: 0.31–0.77). Two interventions were associated with significant increases in potentially harmful discrepancy rates: training existing staff to take BPMHs (HR 1.38, 95% CI: 1.21–1.57) and implementing a new electronic health record (EHR; HR 2.21, 95% CI: 1.64–2.97).

DISCUSSION

We noted that three intervention components were associated with decreased rates of unintentional medication discrepancies with potential for harm, whereas two were associated with increased rates. The components with a beneficial effect were not surprising. A prior qualitative study demonstrated the confusion related to clinicians’ roles and responsibilities during medication reconciliation; therefore, clear delineations should reduce rework and improve the medication reconciliation process.8 Other studies have shown the benefits of pharmacist involvement in the inpatient setting, particularly in reducing errors at discharge.9 However, we did not anticipate that training staff to take BPMHs would be detrimental. Possible reasons for this finding that are based on direct observations by mentors at site visits or noted during monthly calls include (1) training personnel on this task without certification of competency may not sufficiently improve their skills, leading instead to diffusion of responsibility; (2) training personnel without sufficient time to perform the task well (eg, frontline nurses with many other responsibilities) may be counterproductive compared with training a few personnel with time dedicated to this task; and (3) training existing personnel in history-taking may have been used to delay the necessary hiring of more staff to take BPMHs. Future studies could address several of these shortcomings in both the design and implementation of medication history-training intervention components.

Several reasons may explain the association we found between implementing a new EHR and increased rates of discrepancies. Based on mentors’ experiences, we suspect it is because sitewide EHR implementation requires significant resources, time, and effort. Therefore, sitewide EHR implementation pulls attention away from a focus on medication safety

Our study has several limitations. We conducted an on-treatment analysis, which may be confounded by characteristics of sites that chose to implement different intervention components; however, we adjusted for sites in the analysis. Some results are based on a limited number of sites implementing an intervention component (eg, defining roles and responsibilities). Although this was a longitudinal study, and we adjusted for seasonal effects, it is possible that temporal trends and cointerventions confounded our results. The adjudication of discrepancies for the potential for harm was somewhat subjective, although we used a rigorous process to ensure the reliability of adjudication, as in prior studies.3,14 As in the main analysis of the MARQUIS study, this analysis did not measure intervention fidelity.

Based on these analyses and the literature base, we recommend that hospitals focus first on hiring and training dedicated staff (usually pharmacists) to assist with medication reconciliation at discharge.7 Hospitals should also be aware of potential increases in medication discrepancies when implementing a large vendor EHR across their institution. Further work is needed on the best ways to mitigate these adverse effects, at both the design and local site levels. Finally, the effect of medication history training on discrepancies warrants further study.

Disclosures

SK has served as a consultant to Verustat, a remote health monitoring company. All other authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interests.

Funding

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant number: R18 HS019598). JLS has received funding from (1) Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals for an investigator-initiated study of opioid-related adverse drug events in postsurgical patients; (2) Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield for an honorarium and travel expenses for workshop on medication reconciliation; (3) Island Peer Review Organization for honorarium and travel expenses for workshop on medication reconciliation; and, (4) Portola Pharmaceuticals for investigator-initiated study of inpatients who decline subcutaneous medications for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. ASM was funded by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (12-168).

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01337063

Unintentional medication discrepancies in the hospital setting are common and contribute to adverse drug events, resulting in patient harm.1 Discrepancies can be resolved by implementing high-quality medication reconciliation, but there are insufficient data to guide hospitals as to which interventions are most effective at improving medication reconciliation processes and reducing harm.2 We recently reported that implementation of a best practices toolkit reduced total medication discrepancies in the Multi-Center Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS).3 This report describes the effect of individual toolkit components on rates of medication discrepancies with the potential for patient harm.

METHODS

Detailed descriptions of the intervention toolkit and study design of MARQUIS are published.4,5 Briefly, MARQUIS was a pragmatic, mentored, quality improvement (QI) study in which five hospitals in the United States implemented interventions from a best practices toolkit to improve medication reconciliation on noncritical care medical and surgical units from September 2011 to July 2014. We used a mentored implementation approach, in which each site identified the leaders of their local quality improvement team (ie, mentees) who received mentorship from a trained physician with QI and medication safety experience.6 Mentors conducted monthly calls with their mentees and two site visits. Sites adapted and implemented one or more components from the MARQUIS toolkit, a compilation of evidence-based best practices in medication reconciliation.5,7

The primary outcome was unintentional medication discrepancies in admission and discharge orders with the potential for causing harm, as previously described.4 Trained study pharmacists at each site took “gold standard” medication histories on a random sample of up to 22 patients per month. These medications were then compared with admission and discharge medication orders, and all unintentional discrepancies were identified. The discrepancies were then adjudicated by physicians blinded to the treatment arm, who confirmed whether discrepancies were unintentional and carried the potential for patient harm.

We employed a modification of a stepped wedge methodology to measure the incremental effect of implementing nine different intervention components, introduced at different sites over the course of the study, on the number of potentially harmful discrepancies per patient. These analyses were restricted to the postimplementation period on hospital units that implemented at least one intervention. All interventions conducted at each site were categorized by component, including dates of implementation. Each intervention component could be applied more than once per site (eg, when involving a new group of providers) or implemented on a new hospital unit or service, in which case, all dates were included in the analysis. We conducted a multivariable Poisson regression (with time divided into months) adjusted for patient factors, season, and site, with the number of potentially harmful discrepancies as the dependent variable, and the total number of gold standard medications as a model offset. The model was designed to analyze changes in the y-intercept each time an intervention component was either implemented or spread and assumed the change in the y-intercept was the same for each of these events for any given component. The model also assumes that combinations of interventions had independent additive effects.

RESULTS

Across the five participating sites, 1,648 patients were enrolled from September 2011 to July 2014. This number included 613 patients during the preimplementation period and 1,035 patients during the postimplementation period, of which 791 were on intervention units and comprised the study population. Table 1 displays the intervention components implemented by site. Sites implemented between one and seven components. The most frequently implemented intervention component was training existing staff to take the best possible medication histories (BPMHs), implemented at four sites. The regression results are displayed in Table 2. Three interventions were associated with significant decreases in potentially harmful discrepancy rates: (1) clearly defining roles and responsibilities and communicating this with clinical staff (hazard ratio [HR] 0.53, 95% CI: 0.32–0.87); (2) training existing staff to perform discharge medication reconciliation and patient counseling (HR 0.64, 95% CI: 0.46–0.89); and (3) hiring additional staff to perform discharge medication reconciliation and patient counseling (HR 0.48, 95% CI: 0.31–0.77). Two interventions were associated with significant increases in potentially harmful discrepancy rates: training existing staff to take BPMHs (HR 1.38, 95% CI: 1.21–1.57) and implementing a new electronic health record (EHR; HR 2.21, 95% CI: 1.64–2.97).

DISCUSSION

We noted that three intervention components were associated with decreased rates of unintentional medication discrepancies with potential for harm, whereas two were associated with increased rates. The components with a beneficial effect were not surprising. A prior qualitative study demonstrated the confusion related to clinicians’ roles and responsibilities during medication reconciliation; therefore, clear delineations should reduce rework and improve the medication reconciliation process.8 Other studies have shown the benefits of pharmacist involvement in the inpatient setting, particularly in reducing errors at discharge.9 However, we did not anticipate that training staff to take BPMHs would be detrimental. Possible reasons for this finding that are based on direct observations by mentors at site visits or noted during monthly calls include (1) training personnel on this task without certification of competency may not sufficiently improve their skills, leading instead to diffusion of responsibility; (2) training personnel without sufficient time to perform the task well (eg, frontline nurses with many other responsibilities) may be counterproductive compared with training a few personnel with time dedicated to this task; and (3) training existing personnel in history-taking may have been used to delay the necessary hiring of more staff to take BPMHs. Future studies could address several of these shortcomings in both the design and implementation of medication history-training intervention components.

Several reasons may explain the association we found between implementing a new EHR and increased rates of discrepancies. Based on mentors’ experiences, we suspect it is because sitewide EHR implementation requires significant resources, time, and effort. Therefore, sitewide EHR implementation pulls attention away from a focus on medication safety

Our study has several limitations. We conducted an on-treatment analysis, which may be confounded by characteristics of sites that chose to implement different intervention components; however, we adjusted for sites in the analysis. Some results are based on a limited number of sites implementing an intervention component (eg, defining roles and responsibilities). Although this was a longitudinal study, and we adjusted for seasonal effects, it is possible that temporal trends and cointerventions confounded our results. The adjudication of discrepancies for the potential for harm was somewhat subjective, although we used a rigorous process to ensure the reliability of adjudication, as in prior studies.3,14 As in the main analysis of the MARQUIS study, this analysis did not measure intervention fidelity.

Based on these analyses and the literature base, we recommend that hospitals focus first on hiring and training dedicated staff (usually pharmacists) to assist with medication reconciliation at discharge.7 Hospitals should also be aware of potential increases in medication discrepancies when implementing a large vendor EHR across their institution. Further work is needed on the best ways to mitigate these adverse effects, at both the design and local site levels. Finally, the effect of medication history training on discrepancies warrants further study.

Disclosures

SK has served as a consultant to Verustat, a remote health monitoring company. All other authors have no disclosures or conflicts of interests.

Funding

This study was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant number: R18 HS019598). JLS has received funding from (1) Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals for an investigator-initiated study of opioid-related adverse drug events in postsurgical patients; (2) Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield for an honorarium and travel expenses for workshop on medication reconciliation; (3) Island Peer Review Organization for honorarium and travel expenses for workshop on medication reconciliation; and, (4) Portola Pharmaceuticals for investigator-initiated study of inpatients who decline subcutaneous medications for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. ASM was funded by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (12-168).

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01337063

1. Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(4):424-429. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.4.424.

2. Kaboli PJ, Fernandes O. Medication reconciliation: moving forward. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1069-1070. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2667. PubMed

3. Schnipper JL, Mixon A, Stein J, et al. Effects of a multifaceted medication reconciliation quality improvement intervention on patient safety: final results of the MARQUIS study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(12):954-964. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008233.

4. Salanitro AH, Kripalani S, Resnic J, et al. Rational and design of the Multicenter Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS). BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:230. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-230.

5. Mueller SK, Kripalani S, Stein J, et al. Development of a toolkit to disseminate best practices in inpatient medication reconciliation. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39(8):371-382. https://10.1016/S1553-7250(13)39051-5.

6. Maynard GA, Budnitz TL, Nickel WK, et al. 2011 John M. Eisenberg patient safety and quality awards. Mentored implementation: building leaders and achieving results through a collaborative improvement model. Innovation in patient safety and quality at the national level. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(7):301-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(12)38040-9.

7. Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1057-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246.

8. Vogelsmeier A, Pepper GA, Oderda L, Weir C. Medication reconciliation: a qualitative analysis of clinicians’ perceptions. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(4):419-430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.08.002.

9. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, Schnipper JL. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):955-964. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.9.955.

10. Plaisant C, Wu J, Hettinger AZ, Powsner S, Shneiderman B. Novel user interface design for medication reconciliation: an evaluation of Twinlist. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(2):340-349. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocu021.

11. Bassi J, Lau F, Bardal S. Use of information technology in medication reconciliation: a scoping review. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(5):885-897. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1M699.

12. Marien S, Krug B, Spinewine A. Electronic tools to support medication reconciliation: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(1):227-240. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocw068.

13. Agrawal A. Medication errors: prevention using information technology systems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(6):681-686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03427.x.

14. Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1414-1422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0687-9.

1. Cornish PL, Knowles SR, Marchesano R, et al. Unintended medication discrepancies at the time of hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(4):424-429. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.4.424.

2. Kaboli PJ, Fernandes O. Medication reconciliation: moving forward. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1069-1070. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2667. PubMed

3. Schnipper JL, Mixon A, Stein J, et al. Effects of a multifaceted medication reconciliation quality improvement intervention on patient safety: final results of the MARQUIS study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(12):954-964. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008233.

4. Salanitro AH, Kripalani S, Resnic J, et al. Rational and design of the Multicenter Medication Reconciliation Quality Improvement Study (MARQUIS). BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:230. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-230.

5. Mueller SK, Kripalani S, Stein J, et al. Development of a toolkit to disseminate best practices in inpatient medication reconciliation. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39(8):371-382. https://10.1016/S1553-7250(13)39051-5.

6. Maynard GA, Budnitz TL, Nickel WK, et al. 2011 John M. Eisenberg patient safety and quality awards. Mentored implementation: building leaders and achieving results through a collaborative improvement model. Innovation in patient safety and quality at the national level. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2012;38(7):301-310. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(12)38040-9.

7. Mueller SK, Sponsler KC, Kripalani S, Schnipper JL. Hospital-based medication reconciliation practices: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(14):1057-1069. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2246.

8. Vogelsmeier A, Pepper GA, Oderda L, Weir C. Medication reconciliation: a qualitative analysis of clinicians’ perceptions. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2013;9(4):419-430. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2012.08.002.

9. Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, Schnipper JL. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):955-964. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.166.9.955.

10. Plaisant C, Wu J, Hettinger AZ, Powsner S, Shneiderman B. Novel user interface design for medication reconciliation: an evaluation of Twinlist. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2015;22(2):340-349. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocu021.

11. Bassi J, Lau F, Bardal S. Use of information technology in medication reconciliation: a scoping review. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44(5):885-897. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1M699.

12. Marien S, Krug B, Spinewine A. Electronic tools to support medication reconciliation: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(1):227-240. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocw068.

13. Agrawal A. Medication errors: prevention using information technology systems. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(6):681-686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2125.2009.03427.x.

14. Pippins JR, Gandhi TK, Hamann C, et al. Classifying and predicting errors of inpatient medication reconciliation. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1414-1422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0687-9.

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine

Numeracy, Health Literacy, Cognition, and 30-Day Readmissions among Patients with Heart Failure

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.

Subjective health literacy was assessed by using the 3-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS).23 Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy. Objective health literacy was assessed with the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (sTOFHLA).24,25 Scores may be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36).

We assessed cognition by using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ).26 The SPMSQ, which describes a person’s capacity for memory, structured thought, and orientation, has been validated and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.27 Scores of 0 were considered to reflect intact cognition, and scores of 1 or more were considered to reflect any cognitive impairment, a scoring approach employed by other authors.28 We used this approach, rather than the traditional scoring system developed by Pfeiffer et al.26 (1975), because it would be the most sensitive to detect any cognitive impairment in the VICS cohort, which excluded those with severe cognition impairment, dementia, and delirium.

Covariates

During the hospitalization, participants completed an in-person interviewer-administered baseline assessment composed of demographic information, including age, self-reported race (white and nonwhite), educational attainment, home status (married, not married and living with someone, not married and living alone), and household income.

Clinical and diagnostic characteristics abstracted from the medical record included a medical history of HF, HF subtype (classified by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]), coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and comorbidity burden as summarized by the van Walraven-Elixhauser score.29,30 Depressive symptoms were assessed during the 2 weeks prior to the hospitalization by using the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire.31 Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptoms. Laboratory values included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin (g/dl), sodium (mg/L), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/ml) from the last laboratory draw before discharge. Smoking status was also assessed (current and former/nonsmokers).

Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay in days, number of prior admissions in the last year, and transfer to the intensive care unit during the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Pearson χ2 test were used to determine the association between patient characteristics and levels of numeracy, literacy, and cognition separately. The unadjusted relationship between patient characteristics and 30-day readmission was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank sums tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. In addition, a correlation matrix was performed to assess the correlations between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition (supplementary Figure 1).

To examine the association between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition and 30-day readmissions, a series of multivariable Poisson (log-linear) regression models were fit.32 Like other studies, numeracy, health literacy, and cognition were examined as categorical and continuous measures in models.33 Each model was modified with a sandwich estimator for robust standard errors. Log-linear models were chosen over logistic regression models for ease of interpretation because (exponentiated) parameters correspond to risk ratios (RRs) as opposed to odds ratios. Furthermore, the fitting challenges associated with log-linear models when predicted probabilities are near 0 or 1 were not present in these analyses. Redundancy analyses were conducted to ensure that independent variables were not highly correlated with a linear combination of the other independent variables. To avoid case-wise deletion of records with missing covariates, we employed multiple imputation with 10 imputation samples by using predictive mean matching.34,35 All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).36

RESULTS

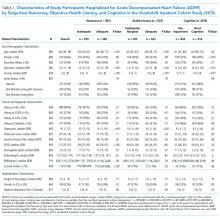

Overall, 883 patients were included in this analysis (supplementary Figure 2). Of the 883 participants, 46% were female and 76% were white (Table 1). Their median age was 60 years (interdecile range [IDR] 39-78) and the median educational attainment was 13.5 years (IDR 11-18).

DISCUSSION

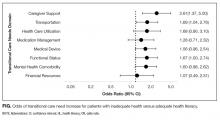

This is the first study to examine the effect of numeracy alongside literacy and cognition on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF. Overall, we found that 33.9% of participants had inadequate numeracy skills, and 24.6% had inadequate or marginal health literacy. In unadjusted and adjusted models, numeracy was not associated with 30-day readmission. Although (objective) low health literacy was associated with 30-day readmission in unadjusted models, it was not in adjusted models. Additionally, though 53% of participants had any cognitive impairment, readmission did not differ significantly by this factor. Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may be greater determinants of 30-day readmissions among patients hospitalized for ADHF.

Only 1 other study has examined the effect of numeracy on readmission risk among patients hospitalized for HF. In this multicenter prospective study, McNaughton et al.37 found low numeracy to be associated with higher odds of recidivism to the emergency department (ED) or hospital within 30 days. Our findings may differ from theirs for a few reasons. First, their study had a significantly higher percentage of individuals with low numeracy (55%) compared with ours (33.9%). This may be because they did not exclude individuals with severe cognitive impairment, and their patient population was of lower socioeconomic status (SES) than ours. Low SES is associated with higher 30-day readmissions among HF patients1,10 throughout the literature, and low numeracy is associated with low SES in other diseases.13,38,39 Finally, they studied recidivism, which was defined as any unplanned return to the ED or hospital within 30 days of the index ED visit for acute HF. We only focused on 30-day readmissions, which also may explain why our results differed.

We found that health literacy was not associated with 30-day readmissions, which is consistent with the literature. Although an association between health literacy and mortality exists among adults with HF, several studies have not found an association between health literacy and 30- and 90-day readmission among adults hospitalized for HF.8,9,40 Although we found an association between objective health literacy and 30-day readmission in unadjusted analyses, we did not find one in the multivariable model. This, along with our numeracy finding, suggests that numeracy and literacy may not be driving the 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF.

We examined cognition alongside numeracy and literacy because it is a prevalent condition among HF patients and because it is associated with adverse outcomes among patients with HF, including readmission.41,42 Studies have shown that HF preferentially affects certain cognitive domains,43 some of which are vital to HF self-care activities. We found that 53% of patients had any cognitive impairment, which is consistent with the literature of adults hospitalized for ADHF.44,45 Cognitive impairment was not, however, associated with 30-day readmissions. There may be a couple reasons for this. First, we measured cognitive impairment with the SPMSQ, which, although widely used and well-validated, does not assess executive function, the domain most commonly affected in HF patients with cognitive impairment.46 Second, patients with severe cognitive impairment and those with delirium were excluded from this study, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in readmission by this factor.

As in prior studies, we found that a history of DM and more hospitalizations in the prior year were independently associated with 30-day readmissions in fully adjusted models. Like other studies, in adjusted models, we found that LVEF and a history of HF were not independently associated with 30-day readmission.47-49 This, however, is not surprising because recent studies have shown that, although HF patients are at risk for multiple hospitalizations, early readmission after a hospitalization for ADHF specifically is often because of reasons unrelated to HF or a non-cardiovascular cause in general.50,51

Although a negative study, several important themes emerged. First, while we were able to assess numeracy, health literacy, and cognition, none of these measures were HF-specific. It is possible that we did not see an effect on readmission because our instruments failed to assess domains specific to HF, such as monitoring weight changes, following a low-salt diet, and interpreting blood pressure. Currently, however, no HF-specific objective numeracy measure exists. With respect to health literacy, only 1 HF-specific measure exists,52 although it was only recently developed and validated. Second, while numeracy may not be a driving influence of all-cause 30-day readmissions, it may be associated with other health behaviors and quality metrics that we did not examine here, such as self-care, medication adherence, and HF-specific readmissions. Third, it is likely that the progression of HF itself, as well as the clinical management of patients following discharge, contribute significantly to 30-day readmissions. Increased attention to predischarge processes for HF patients occurred at VUMC during the study period; close follow-up and evidence-directed therapies may have mitigated some of the expected associations. Finally, we were not able to assess numeracy of participants’ primary caregivers who may help patients at home, especially postdischarge. Though a number of studies have examined the role of family caregivers in the management of HF,53,54 none have examined numeracy levels of caregivers in the context of HF, and this may be worth doing in future studies.

Overall, our study has several strengths. The size of the cohort is large and there were high response rates during the follow-up period. Unlike other HF readmission studies, VICS accounts for readmissions to outside hospitals. Approximately 35% of all hospitalizations in VICS are to outside facilities. Thus, the ascertainment of readmissions to hospitals other than Vanderbilt is more comprehensive than if readmissions to VUMC were only considered. We were able to include a number of clinical comorbidities, laboratory and diagnostic tests from the index admission, and hospitalization characteristics in our analyses. Finally, we performed additional analyses to investigate the correlation between numeracy, literacy, and cognition; ultimately, we found that the majority of these correlations were weak, which supports our ability to study them simultaneously among VICS participants.

Nonetheless, we note some limitations. Although we captured readmissions to outside hospitals, the study took place at a single referral center in Tennessee. Though patients were diverse in age and comorbidities, they were mostly white and of higher SES. Finally, we used home status as a proxy for social support, which may underestimate the support that home care workers provide.

In conclusion, in this prospective longitudinal study of adults hospitalized with ADHF, inadequate numeracy was present in more than a third of patients, and low health literacy was present in roughly a quarter of patients. Neither numeracy nor health literacy, however, were associated with 30-day readmissions in adjusted analyses. Any cognitive impairment, although present in roughly one-half of patients, was not associated with 30-day readmission either. Our findings suggest that other influences may play a more dominant role in determining 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for ADHF than inadequate numeracy, low health literacy, or cognitive impairment as assessed here.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL109388) and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors’ funding sources did not participate in the planning, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the decision to submit for publication. Dr. Sterling is supported by T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Mixon has a VA Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award at the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs (CDA 12-168). This material was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on April 20, 2017, in Washington, DC.

Disclosure

Dr. Kripalani reports personal fees from Verustat, personal fees from SAI Interactive, and equity from Bioscape Digital, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Rothman and Dr. Wallston report personal fees from EdLogics outside of the submitted work. All of the other authors have nothing to disclose

1. Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch of Intern Med. 2008;168(13):1371-1386. PubMed

33. Bohannon AD, Fillenbaum GG, Pieper CF, Hanlon JT, Blazer DG. Relationship of race/ethnicity and blood pressure to change in cognitive function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(3):424-429. PubMed

38. Abdel-Kader K, Dew MA, Bhatnagar M, et al. Numeracy Skills in CKD: Correlates and Outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(9):1566-1573. PubMed

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.

Subjective health literacy was assessed by using the 3-item Brief Health Literacy Screen (BHLS).23 Scores range from 3 to 15, with higher scores reflecting higher literacy. Objective health literacy was assessed with the short form of the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (sTOFHLA).24,25 Scores may be categorized as inadequate (0-16), marginal (17-22), or adequate (23-36).

We assessed cognition by using the 10-item Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ).26 The SPMSQ, which describes a person’s capacity for memory, structured thought, and orientation, has been validated and has demonstrated good reliability and validity.27 Scores of 0 were considered to reflect intact cognition, and scores of 1 or more were considered to reflect any cognitive impairment, a scoring approach employed by other authors.28 We used this approach, rather than the traditional scoring system developed by Pfeiffer et al.26 (1975), because it would be the most sensitive to detect any cognitive impairment in the VICS cohort, which excluded those with severe cognition impairment, dementia, and delirium.

Covariates

During the hospitalization, participants completed an in-person interviewer-administered baseline assessment composed of demographic information, including age, self-reported race (white and nonwhite), educational attainment, home status (married, not married and living with someone, not married and living alone), and household income.

Clinical and diagnostic characteristics abstracted from the medical record included a medical history of HF, HF subtype (classified by left ventricular ejection fraction [LVEF]), coronary artery disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), and comorbidity burden as summarized by the van Walraven-Elixhauser score.29,30 Depressive symptoms were assessed during the 2 weeks prior to the hospitalization by using the first 8 items of the Patient Health Questionnaire.31 Scores ranged from 0 to 24, with higher scores reflecting more severe depressive symptoms. Laboratory values included estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), hemoglobin (g/dl), sodium (mg/L), and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) (pg/ml) from the last laboratory draw before discharge. Smoking status was also assessed (current and former/nonsmokers).

Hospitalization characteristics included length of stay in days, number of prior admissions in the last year, and transfer to the intensive care unit during the index admission.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. The Kruskal-Wallis test and the Pearson χ2 test were used to determine the association between patient characteristics and levels of numeracy, literacy, and cognition separately. The unadjusted relationship between patient characteristics and 30-day readmission was assessed by using Wilcoxon rank sums tests for continuous variables and Pearson χ2 tests for categorical variables. In addition, a correlation matrix was performed to assess the correlations between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition (supplementary Figure 1).

To examine the association between numeracy, health literacy, and cognition and 30-day readmissions, a series of multivariable Poisson (log-linear) regression models were fit.32 Like other studies, numeracy, health literacy, and cognition were examined as categorical and continuous measures in models.33 Each model was modified with a sandwich estimator for robust standard errors. Log-linear models were chosen over logistic regression models for ease of interpretation because (exponentiated) parameters correspond to risk ratios (RRs) as opposed to odds ratios. Furthermore, the fitting challenges associated with log-linear models when predicted probabilities are near 0 or 1 were not present in these analyses. Redundancy analyses were conducted to ensure that independent variables were not highly correlated with a linear combination of the other independent variables. To avoid case-wise deletion of records with missing covariates, we employed multiple imputation with 10 imputation samples by using predictive mean matching.34,35 All analyses were conducted in R version 3.1.2 (The R Foundation, Vienna, Austria).36

RESULTS

Overall, 883 patients were included in this analysis (supplementary Figure 2). Of the 883 participants, 46% were female and 76% were white (Table 1). Their median age was 60 years (interdecile range [IDR] 39-78) and the median educational attainment was 13.5 years (IDR 11-18).

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to examine the effect of numeracy alongside literacy and cognition on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF. Overall, we found that 33.9% of participants had inadequate numeracy skills, and 24.6% had inadequate or marginal health literacy. In unadjusted and adjusted models, numeracy was not associated with 30-day readmission. Although (objective) low health literacy was associated with 30-day readmission in unadjusted models, it was not in adjusted models. Additionally, though 53% of participants had any cognitive impairment, readmission did not differ significantly by this factor. Taken together, these findings suggest that other factors may be greater determinants of 30-day readmissions among patients hospitalized for ADHF.

Only 1 other study has examined the effect of numeracy on readmission risk among patients hospitalized for HF. In this multicenter prospective study, McNaughton et al.37 found low numeracy to be associated with higher odds of recidivism to the emergency department (ED) or hospital within 30 days. Our findings may differ from theirs for a few reasons. First, their study had a significantly higher percentage of individuals with low numeracy (55%) compared with ours (33.9%). This may be because they did not exclude individuals with severe cognitive impairment, and their patient population was of lower socioeconomic status (SES) than ours. Low SES is associated with higher 30-day readmissions among HF patients1,10 throughout the literature, and low numeracy is associated with low SES in other diseases.13,38,39 Finally, they studied recidivism, which was defined as any unplanned return to the ED or hospital within 30 days of the index ED visit for acute HF. We only focused on 30-day readmissions, which also may explain why our results differed.

We found that health literacy was not associated with 30-day readmissions, which is consistent with the literature. Although an association between health literacy and mortality exists among adults with HF, several studies have not found an association between health literacy and 30- and 90-day readmission among adults hospitalized for HF.8,9,40 Although we found an association between objective health literacy and 30-day readmission in unadjusted analyses, we did not find one in the multivariable model. This, along with our numeracy finding, suggests that numeracy and literacy may not be driving the 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized with ADHF.

We examined cognition alongside numeracy and literacy because it is a prevalent condition among HF patients and because it is associated with adverse outcomes among patients with HF, including readmission.41,42 Studies have shown that HF preferentially affects certain cognitive domains,43 some of which are vital to HF self-care activities. We found that 53% of patients had any cognitive impairment, which is consistent with the literature of adults hospitalized for ADHF.44,45 Cognitive impairment was not, however, associated with 30-day readmissions. There may be a couple reasons for this. First, we measured cognitive impairment with the SPMSQ, which, although widely used and well-validated, does not assess executive function, the domain most commonly affected in HF patients with cognitive impairment.46 Second, patients with severe cognitive impairment and those with delirium were excluded from this study, which may have limited our ability to detect differences in readmission by this factor.

As in prior studies, we found that a history of DM and more hospitalizations in the prior year were independently associated with 30-day readmissions in fully adjusted models. Like other studies, in adjusted models, we found that LVEF and a history of HF were not independently associated with 30-day readmission.47-49 This, however, is not surprising because recent studies have shown that, although HF patients are at risk for multiple hospitalizations, early readmission after a hospitalization for ADHF specifically is often because of reasons unrelated to HF or a non-cardiovascular cause in general.50,51

Although a negative study, several important themes emerged. First, while we were able to assess numeracy, health literacy, and cognition, none of these measures were HF-specific. It is possible that we did not see an effect on readmission because our instruments failed to assess domains specific to HF, such as monitoring weight changes, following a low-salt diet, and interpreting blood pressure. Currently, however, no HF-specific objective numeracy measure exists. With respect to health literacy, only 1 HF-specific measure exists,52 although it was only recently developed and validated. Second, while numeracy may not be a driving influence of all-cause 30-day readmissions, it may be associated with other health behaviors and quality metrics that we did not examine here, such as self-care, medication adherence, and HF-specific readmissions. Third, it is likely that the progression of HF itself, as well as the clinical management of patients following discharge, contribute significantly to 30-day readmissions. Increased attention to predischarge processes for HF patients occurred at VUMC during the study period; close follow-up and evidence-directed therapies may have mitigated some of the expected associations. Finally, we were not able to assess numeracy of participants’ primary caregivers who may help patients at home, especially postdischarge. Though a number of studies have examined the role of family caregivers in the management of HF,53,54 none have examined numeracy levels of caregivers in the context of HF, and this may be worth doing in future studies.

Overall, our study has several strengths. The size of the cohort is large and there were high response rates during the follow-up period. Unlike other HF readmission studies, VICS accounts for readmissions to outside hospitals. Approximately 35% of all hospitalizations in VICS are to outside facilities. Thus, the ascertainment of readmissions to hospitals other than Vanderbilt is more comprehensive than if readmissions to VUMC were only considered. We were able to include a number of clinical comorbidities, laboratory and diagnostic tests from the index admission, and hospitalization characteristics in our analyses. Finally, we performed additional analyses to investigate the correlation between numeracy, literacy, and cognition; ultimately, we found that the majority of these correlations were weak, which supports our ability to study them simultaneously among VICS participants.

Nonetheless, we note some limitations. Although we captured readmissions to outside hospitals, the study took place at a single referral center in Tennessee. Though patients were diverse in age and comorbidities, they were mostly white and of higher SES. Finally, we used home status as a proxy for social support, which may underestimate the support that home care workers provide.

In conclusion, in this prospective longitudinal study of adults hospitalized with ADHF, inadequate numeracy was present in more than a third of patients, and low health literacy was present in roughly a quarter of patients. Neither numeracy nor health literacy, however, were associated with 30-day readmissions in adjusted analyses. Any cognitive impairment, although present in roughly one-half of patients, was not associated with 30-day readmission either. Our findings suggest that other influences may play a more dominant role in determining 30-day readmission rates in patients hospitalized for ADHF than inadequate numeracy, low health literacy, or cognitive impairment as assessed here.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R01 HL109388) and in part by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1 TR000445-06). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent official views of the National Institutes of Health. The authors’ funding sources did not participate in the planning, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data or in the decision to submit for publication. Dr. Sterling is supported by T32HS000066 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Dr. Mixon has a VA Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award at the Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, Department of Veterans Affairs (CDA 12-168). This material was presented at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting on April 20, 2017, in Washington, DC.

Disclosure

Dr. Kripalani reports personal fees from Verustat, personal fees from SAI Interactive, and equity from Bioscape Digital, all outside of the submitted work. Dr. Rothman and Dr. Wallston report personal fees from EdLogics outside of the submitted work. All of the other authors have nothing to disclose

Most studies to identify risk factors for readmission among patients with heart failure (HF) have focused on demographic and clinical characteristics.1,2 Although easy to extract from administrative databases, this approach fails to capture the complex psychosocial and cognitive factors that influence the ability of HF patients to manage their disease in the postdischarge period, as depicted in the framework by Meyers et al.3 (2014). To date, studies have found low health literacy, decreased social support, and cognitive impairment to be associated with health behaviors and outcomes among HF patients, including decreased self-care,4 low HF-specific knowledge,5 medication nonadherence,6 hospitalizations,7 and mortality.8-10 Less, however, is known about the effect of numeracy on HF outcomes, such as 30-day readmission.

Numeracy, or quantitative literacy, refers to the ability to access, understand, and apply numerical data to health-related decisions.11 It is estimated that 110 million people in the United States have limited numeracy skills.12 Low numeracy is a risk factor for poor glycemic control among patients with diabetes,13 medication adherence in HIV/AIDS,14 and worse blood pressure control in hypertensives.15 Much like these conditions, HF requires that patients understand, use, and act on numerical information. Maintaining a low-salt diet, monitoring weight, adjusting diuretic doses, and measuring blood pressure are tasks that HF patients are asked to perform on a daily or near-daily basis. These tasks are particularly important in the posthospitalization period and could be complicated by medication changes, which might create additional challenges for patients with inadequate numeracy. Additionally, cognitive impairment, which is a highly prevalent comorbid condition among adults with HF,16,17 might impose additional barriers for those with inadequate numeracy who do not have adequate social support. However, to date, numeracy in the context of HF has not been well described.

Herein, we examined the effects of numeracy, alongside health literacy and cognition, on 30-day readmission risk among patients hospitalized for acute decompensated HF (ADHF).

METHODS

Study Design

The Vanderbilt Inpatient Cohort Study (VICS) is a prospective observational study of patients admitted with cardiovascular disease to Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), an academic tertiary care hospital. VICS was designed to investigate the impact of social determinants of health on postdischarge health outcomes. A detailed description of the study rationale, design, and methods is described elsewhere.3

Briefly, participants completed a baseline interview while hospitalized, and follow-up phone calls were conducted within 1 week of discharge, at 30 days, and at 90 days. At 30 and 90 days postdischarge, healthcare utilization was ascertained by review of medical records and patient report. Clinical data about the index hospitalization were also abstracted. The Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Study Population

Patients hospitalized from 2011 to 2015 with a likely diagnosis of acute coronary syndrome and/or ADHF, as determined by a physician’s review of the medical record, were identified as potentially eligible. Research assistants assessed these patients for the presence of the following exclusion criteria: less than 18 years of age, non-English speaking, unstable psychiatric illness, a low likelihood of follow-up (eg, no reliable telephone number), on hospice, or otherwise too ill to complete an interview. Additionally, those with severe cognitive impairment, as assessed from the medical record (such as seeing a note describing dementia), and those with delirium, as assessed by the brief confusion assessment method, were excluded from enrollment in the study.18,19 Those who died before discharge or during the 30-day follow-up period were excluded. For this analysis, we restricted our sample to only include participants who were hospitalized for ADHF.

Outcome Measure: 30-Day Readmission

The main outcome was all-cause readmission to any hospital within 30 days of discharge, as determined by patient interview, review of electronic medical records from VUMC, and review of outside hospital records.

Main Exposures: Numeracy, Health Literacy, and Cognitive Impairment

Numeracy was assessed with a 3-item version of the Subjective Numeracy Scale (SNS-3), which quantifies the patients perceived quantitative abilities.20 Other authors have shown that the SNS-3 has a correlation coefficient of 0.88 with the full-length SNS-8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78.20-22 The SNS-3 is reported as the mean on a scale from 1 to 6, with higher scores reflecting higher numeracy.