User login

Depression As a Potential Contributing Factor in Hidradenitis Suppurativa and Associated Racial Gaps

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)—a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory disorder involving terminal hair follicles in apocrine gland–rich skin—manifests as tender inflamed nodules that transform into abscesses, sinus tracts, and scarring.1,2 The etiology of HS is multifactorial, encompassing lifestyle, microbiota, hormonal status, and genetic and environmental factors. These factors activate the immune system around the terminal hair follicles and lead to hyperkeratosis of the infundibulum of the hair follicles in intertriginous regions. This progresses to follicular occlusion, stasis, and eventual rupture. Bacterial multiplication within the plugged pilosebaceous units further boosts immune activation. Resident and migrated cells of the innate and adaptive immune system then release proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor, IL-1β, and IL-17, which further enhance immune cell influx and inflammation.3,4 This aberrant immune response propagates the production of deep-seated inflammatory nodules and abscesses.3-8

The estimated prevalence of HS is 1% worldwide.9 It is more prevalent in female and Black patients (0.30%) than White patients (0.09%) and is intermediate in prevalence in the biracial population (0.22%).10 Hidradenitis suppurativa is thought to be associated with lower socioeconomic status (SES). In a retrospective analysis of HS patients (N=375), approximately one-third of patients were Black, had advanced disease, and had a notably lower SES.11 Furthermore, HS has been reported to be associated with systemic inflammation and comorbidities such as morbid obesity (38.3%) and hypertension (39.6%) as well as other metabolic syndrome–related disorders and depression (48.1%).1

Hidradenitis suppurativa may contribute to the risk for depression through its substantial impact on health-related quality of life, which culminates in social withdrawal, unemployment, and suicidal thoughts.12 The high prevalence of depression in individuals with HS1 and its association with systemic inflammation13 increases the likelihood that a common genetic predisposition also may exist between both conditions. Because depression frequently has been discovered as a concomitant diagnosis in patients with HS, we hypothesize that a shared genetic susceptibility also may exist between the 2 disorders. Our study sought to explore data on the co-occurrence of depression with HS, including its demographics and racial data.

Methods

We conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as Google Scholar using the terms depression and hidradenitis suppurativa to obtain all research articles published from 2000 to 2022. Articles were selected based on relevance to the topic of exploration. English-language articles that directly addressed the epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, and co-occurrence of both depression and HS with numerical data were included. Articles were excluded if they did not explore the information of interest on these 2 disorders or did not contain clear statistical data of patients with the 2 concurrent medical conditions.

Results

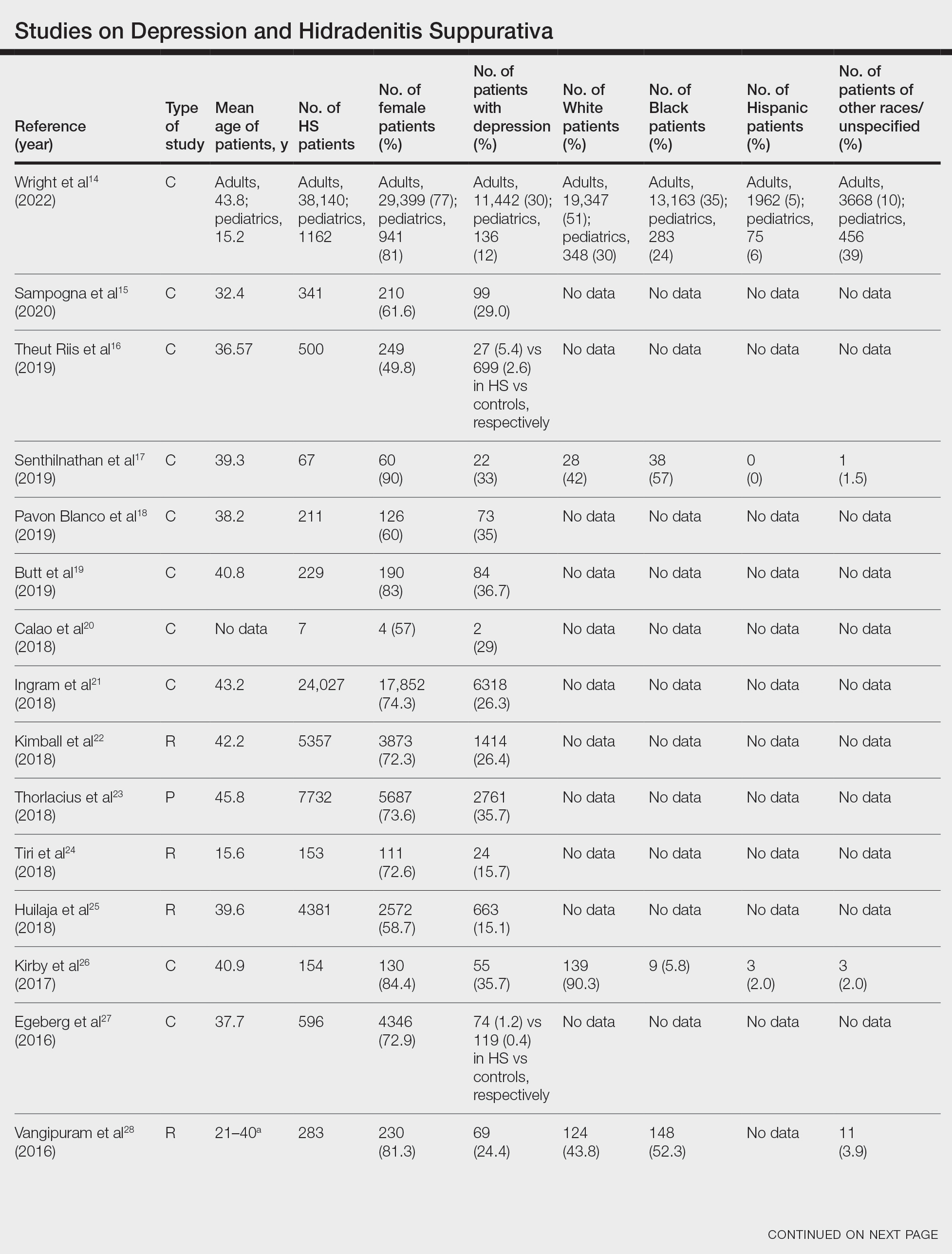

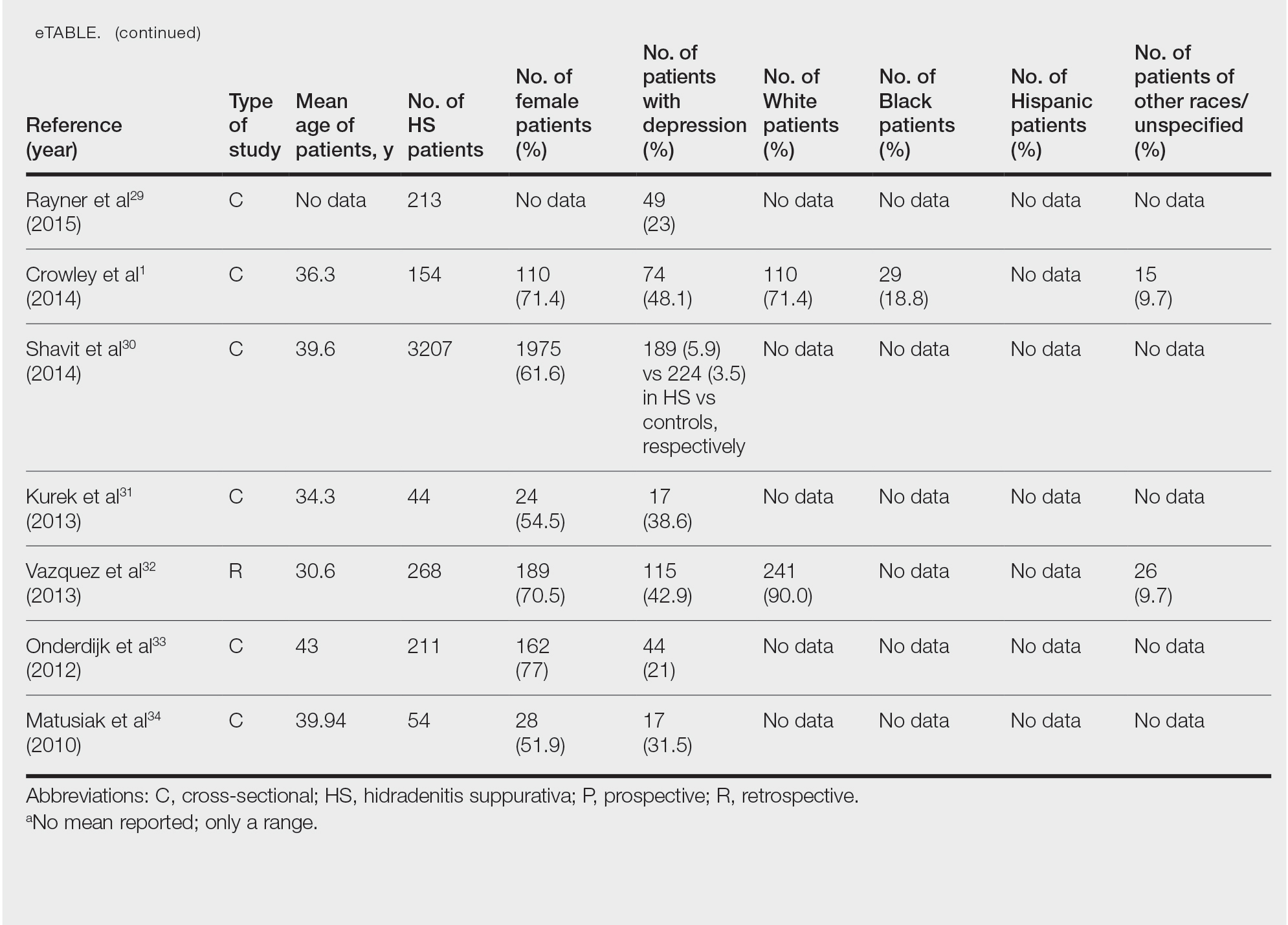

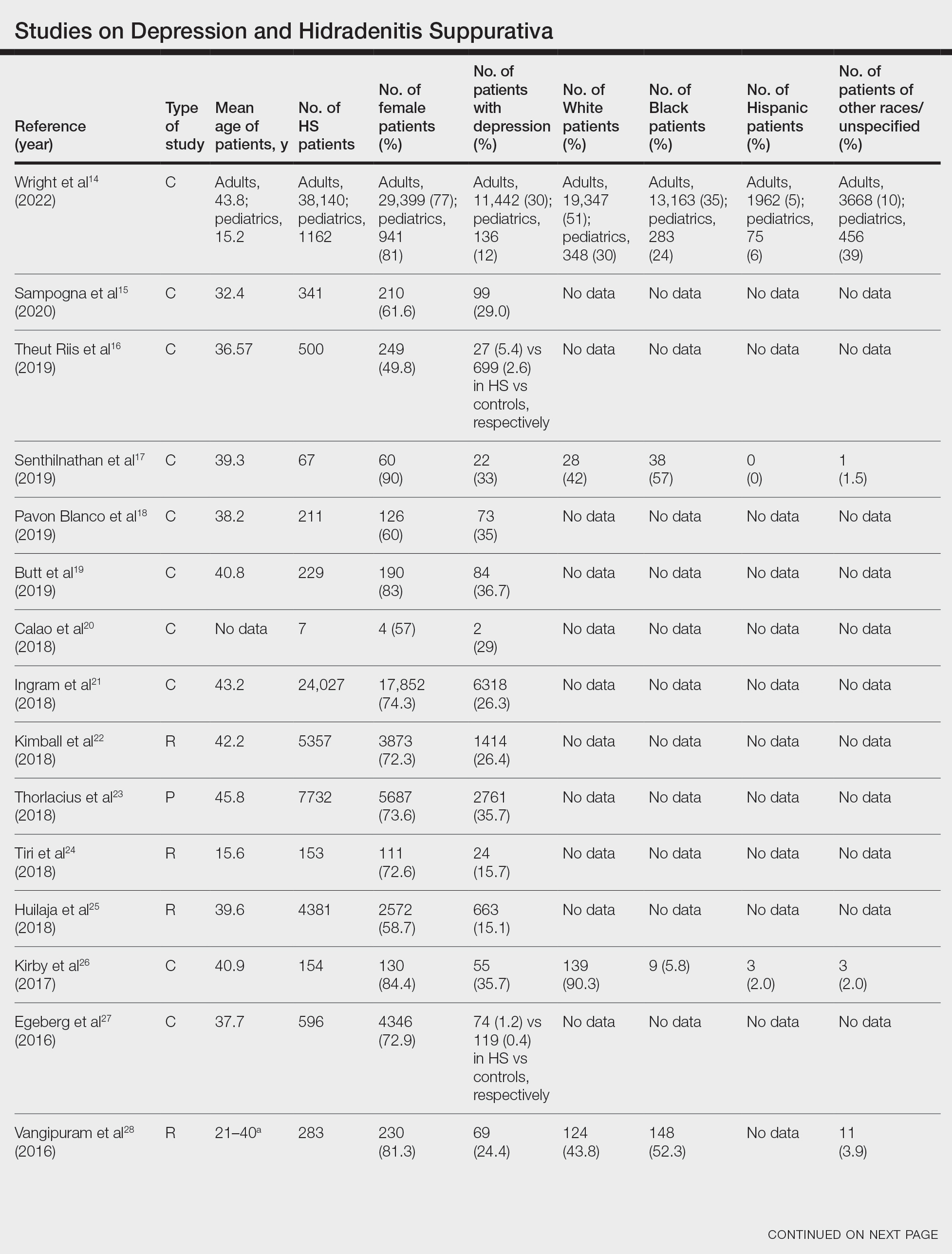

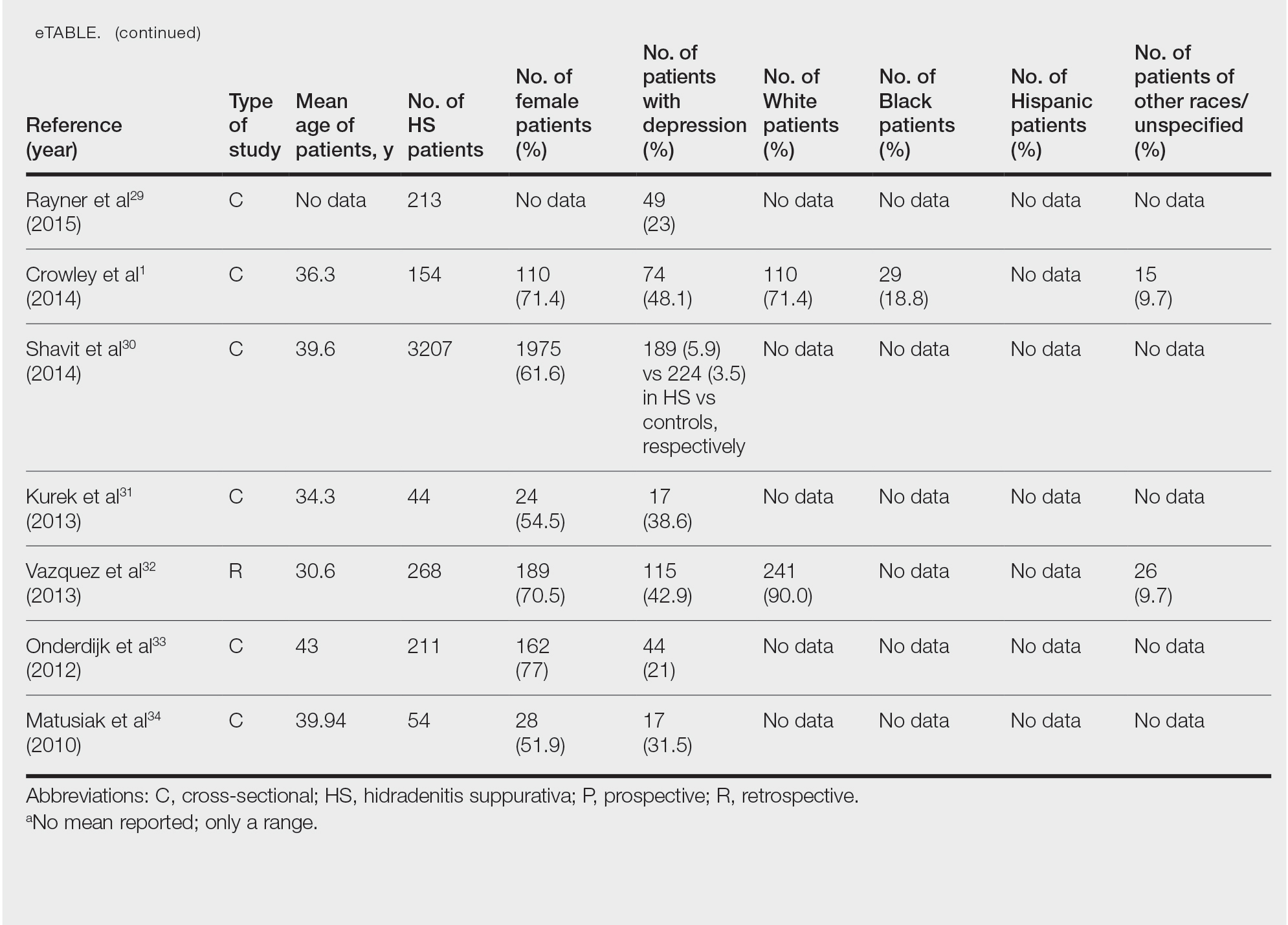

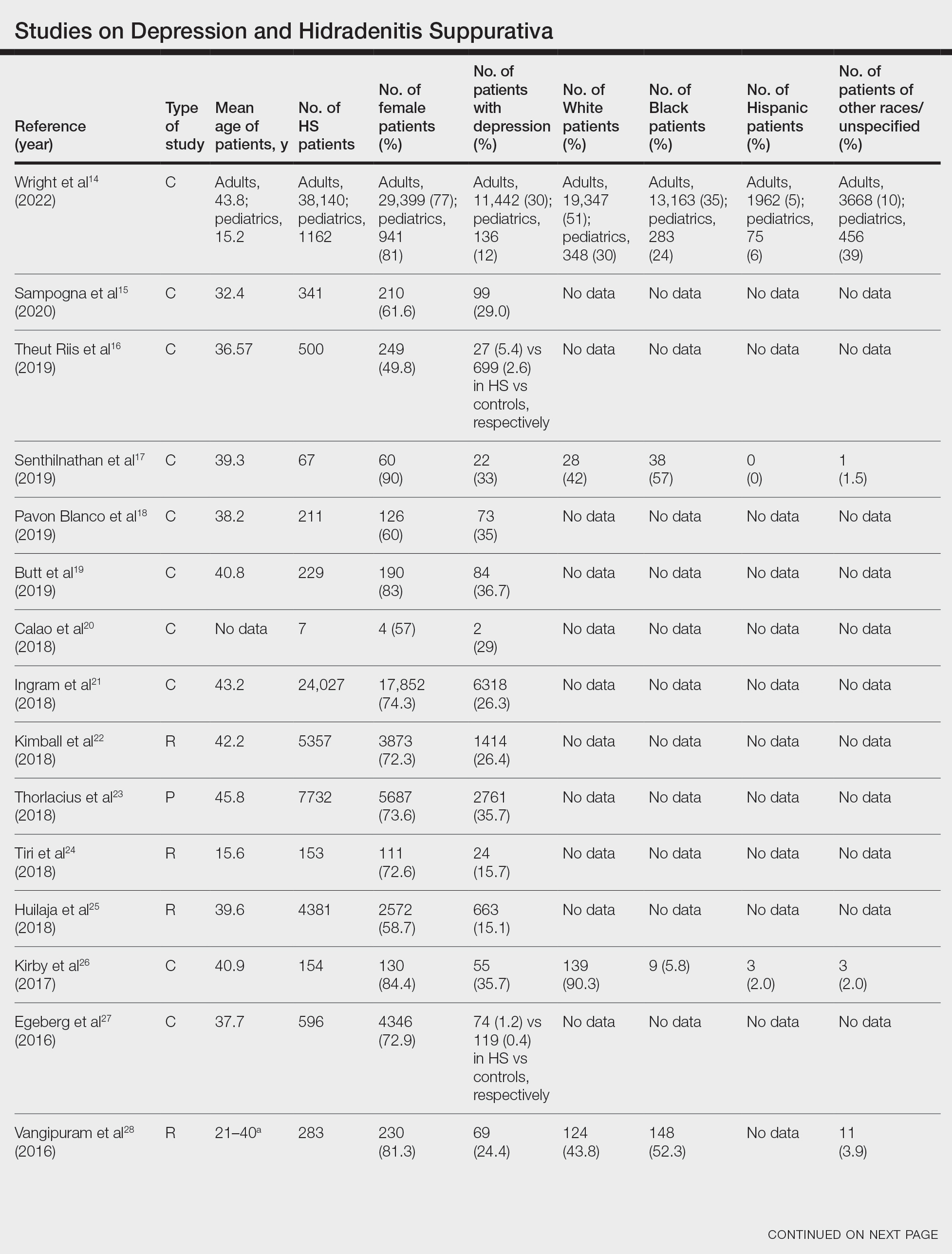

Twenty-two cross-sectional, prospective, and retrospective studies that fit the search criteria were identified and included in the analysis (eTable).1,14-34 Sixteen (72.7%) studies were cross-sectional, 5 (22.7%) were retrospective, and only 1 (4.5%) was a prospective study. Only 6 of the studies provided racial data,1,14,17,26,28,32 and of them, 4 had predominately White patients,1,14,26,32 whereas the other 2 had predominantly Black patients.17,28

Hidradenitis suppurativa was found to coexist with depression in all the studies, with a prevalence of 1.2% to 48.1%. There also was a higher prevalence of depression in HS patients than in the control patients without HS. Furthermore, a recent study by Wright and colleagues14 stratified the depression prevalence data by age and found a higher prevalence of depression in adults vs children with HS (30% vs 12%).

Comment

Major depression—a chronic and debilitating illness—is the chief cause of disability globally and in the United States alone and has a global lifetime prevalence of 17%.35 In a study of 388 patients diagnosed with depression and 404 community-matched controls who were observed for 10 years, depressed patients had a two-thirds higher likelihood of developing a serious physical illness than controls. The depression-associated elevated risk for serious physical illness persisted after controlling for confounding variables such as alcohol abuse, smoking, and level of physical activity.36 Studies also have demonstrated that HS is more prevalent in Black individuals10 and in individuals of low SES,37 who are mostly the Black and Hispanic populations that experience the highest burden of racial microaggression38 and disparities in health access and outcomes.39,40 The severity and chronicity of major depressive disorder also is higher in Black patients compared with White patients (57% vs 39%).41 Because major depression and HS are most common among Black patients who experience the highest-burden negative financial and health disparities, there may be a shared genetic disposition to both medical conditions.

Moreover, the common detrimental lifestyle choices associated with patients with depression and HS also suggest the possibility of a collective genetic susceptibility. Patients with depression also report increased consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit substances; sedentary lifestyle leading to obesity; and poor compliance with prescribed medical treatment.42 Smoking and obesity are known contributors to the pathogenesis of HS, and their modification also is known to positively impact the disease course. In a retrospective single-cohort study, 50% of obese HS patients (n=35) reported a substantial decrease in disease severity after a reduction of more than 15% in body mass index over 2 years following bariatric surgery (n=35).43 Patients with HS also have reported disease remission following extensive weight loss.44 In addition, evidence has supported smoking cessation in improving the disease course of HS.43 Because these detrimental lifestyle choices are prevalent in both patients with HS and those with depression, a co-genetic susceptibility also may exist.

Furthermore, depression is characterized by a persistent inflammatory state,13,45 similar to HS.46 Elevated levels of a variety of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1, have been reported in patients with depression compared with healthy controls.13,45 Further analysis found a positive correlation and a strong association between depression and these inflammatory markers.47 Moreover, adipokines regulate inflammatory responses, and adipokines play a role in the pathogenesis of HS. Adipokine levels such as elevated omentin-1 (a recently identified adipokine) were found to be altered in patients with HS compared with controls.48 Results from clinical studies and meta-analyses of patients with depression also have demonstrated that adipokines are dysregulated in this population,49,50 which may be another potential genetic link between depression and HS.

In addition, genetic susceptibility to depression and HS may be shared because the inflammatory markers that have a strong association with depression also have been found to play an important role in HS treatment and disease severity prediction. In a retrospective cohort study of 404 patients, CRP or IL-6 levels were found to be reliable predictors of HS disease severity, which may explain why anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody regimens such as adalimumab and infliximab have clinically ameliorated disease activity in several cases of HS.51 In a study evaluating these drugs, high baseline levels of high-sensitivity CRP and IL-6 were predictive of patient response to infliximab.52 In a meta-analysis evaluating 20,791 participants, an association was found between concurrent depression and CRP. Furthermore, inflammation measured by high levels of CRP or IL-6 was observed to predict future depression.53 If the same inflammatory markers—CRP and IL-6—both play a major role in the disease activity of depression and HS, then a concurrent genetic predisposition may exist.

Conclusion

Understanding the comorbidities, etiologies, and risk factors for the development and progression of HS is an important step toward improved disease management. Available studies on comorbid depression in HS largely involve White patients, and more studies are needed in patients with skin of color, particularly the Black population, who have the highest prevalence of HS.10 Given the evidence for an association between depression and HS, we suggest a large-scale investigation of this patient population that includes a complete medical history, onset of HS in comparison to the onset of depression, and specific measures of disease progress and lifetime management of depression, which may help to increase knowledge about the role of depression in HS and encourage more research in this area. If shared genetic susceptibility is established, aggressive management of depression in patients at risk for HS may reduce disease incidence and severity as well as the psychological burden on patients.

- Crowley JJ, Mekkes JR, Zouboulis CC, et al. Association of hidradenitis suppurativa disease severity with increased risk for systemic comorbidities. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1561-1565.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115.

- Sabat R, Jemec GBE, Matusiak Ł, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6:1-20.

- Wolk K, Warszawska K, Hoeflich C, et al. Deficiency of IL-22 contributes to a chronic inflammatory disease: pathogenetic mechanisms in acne inversa. J Immunol. 2011;186:1228-1239.

- von Laffert M, Helmbold P, Wohlrab J, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa): early inflammatory events at terminal follicles and at interfollicular epidermis. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:533-537.

- Van Der Zee HH, De Ruiter L, Van Den Broecke DG, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-α and IL-1β. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1292-1298.

- Schlapbach C, Hänni T, Yawalkar N, et al. Expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:790-798.

- Kelly G, Hughes R, McGarry T, et al. Dysregulated cytokine expression in lesional and nonlesional skin in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1431-1439.

- Jemec GBE, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 Suppl 1):S4-S7.

- Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760-764.

- Soliman YS, Hoffman LK, Guzman AK, et al. African American patients with hidradenitis suppurativa have significant health care disparities: a retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:334-336.

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101.

- Beatriz Currier M, Nemeroff CB. Inflammation and mood disorders: proinflammatory cytokines and the pathogenesis of depression. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2012;9:212-220.

- Wright S, Strunk A, Garg A. Prevalence of depression among children, adolescents, and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:55-60.

- Sampogna F, Fania L, Mastroeni S, et al. Correlation between depression, quality of life and clinical severity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:1-6.

- Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

- Senthilnathan A, Kolli SS, Cardwell LA, et al. Depression in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1087-1088.

- Pavon Blanco A, Turner MA, Petrof G, et al. To what extent do disease severity and illness perceptions explain depression, anxiety and quality of life in hidradenitis suppurativa? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:338-345.

- Butt M, Sisic M, Silva C, et al. The associations of depression and coping methods on health-related quality of life for those with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1137-1139.

- Calao M, Wilson JL, Spelman L, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) prevalence, demographics and management pathways in Australia: a population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200683.

- Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, et al. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:917-924.

- Kimball AB, Sundaram M, Gauthier G, et al. The comorbidity burden of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a claims data analysis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2018;8:557.

- Thorlacius L, Cohen AD, Gislason GH, et al. Increased suicide risk in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:52-57.

- Tiri H, Jokelainen J, Timonen M, et al. Somatic and psychiatric comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:514-519.

- Huilaja L, Tiri H, Jokelainen J, et al. Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa have a high psychiatric disease burden: a Finnish nationwide registry study. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:46-51.

- Kirby JS, Butt M, Esmann S, et al. Association of resilience with depression and health-related quality of life for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1263.

- Egeberg A, Gislason GH, Hansen PR. Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:429-434.

- Vangipuram R, Vaidya T, Jandarov R, et al. Factors contributing to depression and chronic pain in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from a single-center retrospective review. Dermatology. 2016;232:692-695.

- Rayner L, Jackson K, Turner M, et al. Integrated mental health assessment in a tertiary medical dermatology service: feasibility and the prevalence of common mental disorder. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:201.

- Shavit E, Dreiher J, Freud T, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in 3207 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online June 9, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:371-376.

- Kurek A, Johanne Peters EM, Sabat R, et al. Depression is a frequent co-morbidity in patients with acne inversa. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:743-749.

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97.

- Onderdijk AJ, Van Der Zee HH, Esmann S, et al. Depression in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online February 20, 2012]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:473-478.

- Matusiak Ł, Bieniek A, Szepietowski JC. Psychophysical aspects of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:264-268.

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617-627.

- Holahan CJ, Pahl SA, Cronkite RC, et al. Depression and vulnerability to incident physical illness across 10 years. J Affect Disord. 2009;123:222-229.

- Deckers IE, Janse IC, van der Zee HH, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is associated with low socioeconomic status (SES): a cross-sectional reference study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:755-759.e1.

- Williams MT, Skinta MD, Kanter JW, et al. A qualitative study of microaggressions against African Americans on predominantly White campuses. BMC Psychol. 2020;8:1-13.

- Dunlop DD, Song J, Lyons JS, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in rates of depression among preretirement adults. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1945-1952.

- Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35:407-411.

- Williams DR, González HM, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:305-315.

- Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283:506-511.

- Kromann CB, Deckers IE, Esmann S, et al. Risk factors, clinical course and long-term prognosis in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:819-824.

- Sivanand A, Gulliver WP, Josan CK, et al. Weight loss and dietary interventions for hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg . 2020;24:64-72.

- Raedler TJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in major depressive disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:519-525.

- Rocha VZ, Libby P. Obesity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:399-409.

- Davidson KW, Schwartz JE, Kirkland SA, et al. Relation of inflammation to depression and incident coronary heart disease (from the Canadian Nova Scotia Health Survey [NSHS95] Prospective Population Study). Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:755-761.

- González-López MA, Ocejo-Viñals JG, Mata C, et al. Evaluation of serum omentin-1 and apelin concentrations in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:450-454.

- Taylor VH, Macqueen GM. The role of adipokines in understanding the associations between obesity and depression. J Obes. 2010;2010:748048.

- Setayesh L, Ebrahimi R, Pooyan S, et al. The possible mediatory role of adipokines in the association between low carbohydrate diet and depressive symptoms among overweight and obese women. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0257275 .

- Andriano TM, Benesh G, Babbush KM, et al. Serum inflammatory markers and leukocyte profiles accurately describe hidradenitis suppurativa disease severity. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1270-1275.

- Montaudié H, Seitz-Polski B, Cornille A, et al. Interleukin 6 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein are potential predictive markers of response to infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;6:156-158.

- Colasanto M, Madigan S, Korczak DJ. Depression and inflammation among children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:940-948.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)—a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory disorder involving terminal hair follicles in apocrine gland–rich skin—manifests as tender inflamed nodules that transform into abscesses, sinus tracts, and scarring.1,2 The etiology of HS is multifactorial, encompassing lifestyle, microbiota, hormonal status, and genetic and environmental factors. These factors activate the immune system around the terminal hair follicles and lead to hyperkeratosis of the infundibulum of the hair follicles in intertriginous regions. This progresses to follicular occlusion, stasis, and eventual rupture. Bacterial multiplication within the plugged pilosebaceous units further boosts immune activation. Resident and migrated cells of the innate and adaptive immune system then release proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor, IL-1β, and IL-17, which further enhance immune cell influx and inflammation.3,4 This aberrant immune response propagates the production of deep-seated inflammatory nodules and abscesses.3-8

The estimated prevalence of HS is 1% worldwide.9 It is more prevalent in female and Black patients (0.30%) than White patients (0.09%) and is intermediate in prevalence in the biracial population (0.22%).10 Hidradenitis suppurativa is thought to be associated with lower socioeconomic status (SES). In a retrospective analysis of HS patients (N=375), approximately one-third of patients were Black, had advanced disease, and had a notably lower SES.11 Furthermore, HS has been reported to be associated with systemic inflammation and comorbidities such as morbid obesity (38.3%) and hypertension (39.6%) as well as other metabolic syndrome–related disorders and depression (48.1%).1

Hidradenitis suppurativa may contribute to the risk for depression through its substantial impact on health-related quality of life, which culminates in social withdrawal, unemployment, and suicidal thoughts.12 The high prevalence of depression in individuals with HS1 and its association with systemic inflammation13 increases the likelihood that a common genetic predisposition also may exist between both conditions. Because depression frequently has been discovered as a concomitant diagnosis in patients with HS, we hypothesize that a shared genetic susceptibility also may exist between the 2 disorders. Our study sought to explore data on the co-occurrence of depression with HS, including its demographics and racial data.

Methods

We conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as Google Scholar using the terms depression and hidradenitis suppurativa to obtain all research articles published from 2000 to 2022. Articles were selected based on relevance to the topic of exploration. English-language articles that directly addressed the epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, and co-occurrence of both depression and HS with numerical data were included. Articles were excluded if they did not explore the information of interest on these 2 disorders or did not contain clear statistical data of patients with the 2 concurrent medical conditions.

Results

Twenty-two cross-sectional, prospective, and retrospective studies that fit the search criteria were identified and included in the analysis (eTable).1,14-34 Sixteen (72.7%) studies were cross-sectional, 5 (22.7%) were retrospective, and only 1 (4.5%) was a prospective study. Only 6 of the studies provided racial data,1,14,17,26,28,32 and of them, 4 had predominately White patients,1,14,26,32 whereas the other 2 had predominantly Black patients.17,28

Hidradenitis suppurativa was found to coexist with depression in all the studies, with a prevalence of 1.2% to 48.1%. There also was a higher prevalence of depression in HS patients than in the control patients without HS. Furthermore, a recent study by Wright and colleagues14 stratified the depression prevalence data by age and found a higher prevalence of depression in adults vs children with HS (30% vs 12%).

Comment

Major depression—a chronic and debilitating illness—is the chief cause of disability globally and in the United States alone and has a global lifetime prevalence of 17%.35 In a study of 388 patients diagnosed with depression and 404 community-matched controls who were observed for 10 years, depressed patients had a two-thirds higher likelihood of developing a serious physical illness than controls. The depression-associated elevated risk for serious physical illness persisted after controlling for confounding variables such as alcohol abuse, smoking, and level of physical activity.36 Studies also have demonstrated that HS is more prevalent in Black individuals10 and in individuals of low SES,37 who are mostly the Black and Hispanic populations that experience the highest burden of racial microaggression38 and disparities in health access and outcomes.39,40 The severity and chronicity of major depressive disorder also is higher in Black patients compared with White patients (57% vs 39%).41 Because major depression and HS are most common among Black patients who experience the highest-burden negative financial and health disparities, there may be a shared genetic disposition to both medical conditions.

Moreover, the common detrimental lifestyle choices associated with patients with depression and HS also suggest the possibility of a collective genetic susceptibility. Patients with depression also report increased consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit substances; sedentary lifestyle leading to obesity; and poor compliance with prescribed medical treatment.42 Smoking and obesity are known contributors to the pathogenesis of HS, and their modification also is known to positively impact the disease course. In a retrospective single-cohort study, 50% of obese HS patients (n=35) reported a substantial decrease in disease severity after a reduction of more than 15% in body mass index over 2 years following bariatric surgery (n=35).43 Patients with HS also have reported disease remission following extensive weight loss.44 In addition, evidence has supported smoking cessation in improving the disease course of HS.43 Because these detrimental lifestyle choices are prevalent in both patients with HS and those with depression, a co-genetic susceptibility also may exist.

Furthermore, depression is characterized by a persistent inflammatory state,13,45 similar to HS.46 Elevated levels of a variety of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1, have been reported in patients with depression compared with healthy controls.13,45 Further analysis found a positive correlation and a strong association between depression and these inflammatory markers.47 Moreover, adipokines regulate inflammatory responses, and adipokines play a role in the pathogenesis of HS. Adipokine levels such as elevated omentin-1 (a recently identified adipokine) were found to be altered in patients with HS compared with controls.48 Results from clinical studies and meta-analyses of patients with depression also have demonstrated that adipokines are dysregulated in this population,49,50 which may be another potential genetic link between depression and HS.

In addition, genetic susceptibility to depression and HS may be shared because the inflammatory markers that have a strong association with depression also have been found to play an important role in HS treatment and disease severity prediction. In a retrospective cohort study of 404 patients, CRP or IL-6 levels were found to be reliable predictors of HS disease severity, which may explain why anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody regimens such as adalimumab and infliximab have clinically ameliorated disease activity in several cases of HS.51 In a study evaluating these drugs, high baseline levels of high-sensitivity CRP and IL-6 were predictive of patient response to infliximab.52 In a meta-analysis evaluating 20,791 participants, an association was found between concurrent depression and CRP. Furthermore, inflammation measured by high levels of CRP or IL-6 was observed to predict future depression.53 If the same inflammatory markers—CRP and IL-6—both play a major role in the disease activity of depression and HS, then a concurrent genetic predisposition may exist.

Conclusion

Understanding the comorbidities, etiologies, and risk factors for the development and progression of HS is an important step toward improved disease management. Available studies on comorbid depression in HS largely involve White patients, and more studies are needed in patients with skin of color, particularly the Black population, who have the highest prevalence of HS.10 Given the evidence for an association between depression and HS, we suggest a large-scale investigation of this patient population that includes a complete medical history, onset of HS in comparison to the onset of depression, and specific measures of disease progress and lifetime management of depression, which may help to increase knowledge about the role of depression in HS and encourage more research in this area. If shared genetic susceptibility is established, aggressive management of depression in patients at risk for HS may reduce disease incidence and severity as well as the psychological burden on patients.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)—a chronic, relapsing, inflammatory disorder involving terminal hair follicles in apocrine gland–rich skin—manifests as tender inflamed nodules that transform into abscesses, sinus tracts, and scarring.1,2 The etiology of HS is multifactorial, encompassing lifestyle, microbiota, hormonal status, and genetic and environmental factors. These factors activate the immune system around the terminal hair follicles and lead to hyperkeratosis of the infundibulum of the hair follicles in intertriginous regions. This progresses to follicular occlusion, stasis, and eventual rupture. Bacterial multiplication within the plugged pilosebaceous units further boosts immune activation. Resident and migrated cells of the innate and adaptive immune system then release proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor, IL-1β, and IL-17, which further enhance immune cell influx and inflammation.3,4 This aberrant immune response propagates the production of deep-seated inflammatory nodules and abscesses.3-8

The estimated prevalence of HS is 1% worldwide.9 It is more prevalent in female and Black patients (0.30%) than White patients (0.09%) and is intermediate in prevalence in the biracial population (0.22%).10 Hidradenitis suppurativa is thought to be associated with lower socioeconomic status (SES). In a retrospective analysis of HS patients (N=375), approximately one-third of patients were Black, had advanced disease, and had a notably lower SES.11 Furthermore, HS has been reported to be associated with systemic inflammation and comorbidities such as morbid obesity (38.3%) and hypertension (39.6%) as well as other metabolic syndrome–related disorders and depression (48.1%).1

Hidradenitis suppurativa may contribute to the risk for depression through its substantial impact on health-related quality of life, which culminates in social withdrawal, unemployment, and suicidal thoughts.12 The high prevalence of depression in individuals with HS1 and its association with systemic inflammation13 increases the likelihood that a common genetic predisposition also may exist between both conditions. Because depression frequently has been discovered as a concomitant diagnosis in patients with HS, we hypothesize that a shared genetic susceptibility also may exist between the 2 disorders. Our study sought to explore data on the co-occurrence of depression with HS, including its demographics and racial data.

Methods

We conducted a PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE as well as Google Scholar using the terms depression and hidradenitis suppurativa to obtain all research articles published from 2000 to 2022. Articles were selected based on relevance to the topic of exploration. English-language articles that directly addressed the epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology, and co-occurrence of both depression and HS with numerical data were included. Articles were excluded if they did not explore the information of interest on these 2 disorders or did not contain clear statistical data of patients with the 2 concurrent medical conditions.

Results

Twenty-two cross-sectional, prospective, and retrospective studies that fit the search criteria were identified and included in the analysis (eTable).1,14-34 Sixteen (72.7%) studies were cross-sectional, 5 (22.7%) were retrospective, and only 1 (4.5%) was a prospective study. Only 6 of the studies provided racial data,1,14,17,26,28,32 and of them, 4 had predominately White patients,1,14,26,32 whereas the other 2 had predominantly Black patients.17,28

Hidradenitis suppurativa was found to coexist with depression in all the studies, with a prevalence of 1.2% to 48.1%. There also was a higher prevalence of depression in HS patients than in the control patients without HS. Furthermore, a recent study by Wright and colleagues14 stratified the depression prevalence data by age and found a higher prevalence of depression in adults vs children with HS (30% vs 12%).

Comment

Major depression—a chronic and debilitating illness—is the chief cause of disability globally and in the United States alone and has a global lifetime prevalence of 17%.35 In a study of 388 patients diagnosed with depression and 404 community-matched controls who were observed for 10 years, depressed patients had a two-thirds higher likelihood of developing a serious physical illness than controls. The depression-associated elevated risk for serious physical illness persisted after controlling for confounding variables such as alcohol abuse, smoking, and level of physical activity.36 Studies also have demonstrated that HS is more prevalent in Black individuals10 and in individuals of low SES,37 who are mostly the Black and Hispanic populations that experience the highest burden of racial microaggression38 and disparities in health access and outcomes.39,40 The severity and chronicity of major depressive disorder also is higher in Black patients compared with White patients (57% vs 39%).41 Because major depression and HS are most common among Black patients who experience the highest-burden negative financial and health disparities, there may be a shared genetic disposition to both medical conditions.

Moreover, the common detrimental lifestyle choices associated with patients with depression and HS also suggest the possibility of a collective genetic susceptibility. Patients with depression also report increased consumption of alcohol, tobacco, and illicit substances; sedentary lifestyle leading to obesity; and poor compliance with prescribed medical treatment.42 Smoking and obesity are known contributors to the pathogenesis of HS, and their modification also is known to positively impact the disease course. In a retrospective single-cohort study, 50% of obese HS patients (n=35) reported a substantial decrease in disease severity after a reduction of more than 15% in body mass index over 2 years following bariatric surgery (n=35).43 Patients with HS also have reported disease remission following extensive weight loss.44 In addition, evidence has supported smoking cessation in improving the disease course of HS.43 Because these detrimental lifestyle choices are prevalent in both patients with HS and those with depression, a co-genetic susceptibility also may exist.

Furthermore, depression is characterized by a persistent inflammatory state,13,45 similar to HS.46 Elevated levels of a variety of inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, and soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1, have been reported in patients with depression compared with healthy controls.13,45 Further analysis found a positive correlation and a strong association between depression and these inflammatory markers.47 Moreover, adipokines regulate inflammatory responses, and adipokines play a role in the pathogenesis of HS. Adipokine levels such as elevated omentin-1 (a recently identified adipokine) were found to be altered in patients with HS compared with controls.48 Results from clinical studies and meta-analyses of patients with depression also have demonstrated that adipokines are dysregulated in this population,49,50 which may be another potential genetic link between depression and HS.

In addition, genetic susceptibility to depression and HS may be shared because the inflammatory markers that have a strong association with depression also have been found to play an important role in HS treatment and disease severity prediction. In a retrospective cohort study of 404 patients, CRP or IL-6 levels were found to be reliable predictors of HS disease severity, which may explain why anti–tumor necrosis factor antibody regimens such as adalimumab and infliximab have clinically ameliorated disease activity in several cases of HS.51 In a study evaluating these drugs, high baseline levels of high-sensitivity CRP and IL-6 were predictive of patient response to infliximab.52 In a meta-analysis evaluating 20,791 participants, an association was found between concurrent depression and CRP. Furthermore, inflammation measured by high levels of CRP or IL-6 was observed to predict future depression.53 If the same inflammatory markers—CRP and IL-6—both play a major role in the disease activity of depression and HS, then a concurrent genetic predisposition may exist.

Conclusion

Understanding the comorbidities, etiologies, and risk factors for the development and progression of HS is an important step toward improved disease management. Available studies on comorbid depression in HS largely involve White patients, and more studies are needed in patients with skin of color, particularly the Black population, who have the highest prevalence of HS.10 Given the evidence for an association between depression and HS, we suggest a large-scale investigation of this patient population that includes a complete medical history, onset of HS in comparison to the onset of depression, and specific measures of disease progress and lifetime management of depression, which may help to increase knowledge about the role of depression in HS and encourage more research in this area. If shared genetic susceptibility is established, aggressive management of depression in patients at risk for HS may reduce disease incidence and severity as well as the psychological burden on patients.

- Crowley JJ, Mekkes JR, Zouboulis CC, et al. Association of hidradenitis suppurativa disease severity with increased risk for systemic comorbidities. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1561-1565.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115.

- Sabat R, Jemec GBE, Matusiak Ł, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6:1-20.

- Wolk K, Warszawska K, Hoeflich C, et al. Deficiency of IL-22 contributes to a chronic inflammatory disease: pathogenetic mechanisms in acne inversa. J Immunol. 2011;186:1228-1239.

- von Laffert M, Helmbold P, Wohlrab J, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa): early inflammatory events at terminal follicles and at interfollicular epidermis. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:533-537.

- Van Der Zee HH, De Ruiter L, Van Den Broecke DG, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-α and IL-1β. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1292-1298.

- Schlapbach C, Hänni T, Yawalkar N, et al. Expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:790-798.

- Kelly G, Hughes R, McGarry T, et al. Dysregulated cytokine expression in lesional and nonlesional skin in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1431-1439.

- Jemec GBE, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 Suppl 1):S4-S7.

- Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760-764.

- Soliman YS, Hoffman LK, Guzman AK, et al. African American patients with hidradenitis suppurativa have significant health care disparities: a retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:334-336.

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101.

- Beatriz Currier M, Nemeroff CB. Inflammation and mood disorders: proinflammatory cytokines and the pathogenesis of depression. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2012;9:212-220.

- Wright S, Strunk A, Garg A. Prevalence of depression among children, adolescents, and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:55-60.

- Sampogna F, Fania L, Mastroeni S, et al. Correlation between depression, quality of life and clinical severity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:1-6.

- Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

- Senthilnathan A, Kolli SS, Cardwell LA, et al. Depression in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1087-1088.

- Pavon Blanco A, Turner MA, Petrof G, et al. To what extent do disease severity and illness perceptions explain depression, anxiety and quality of life in hidradenitis suppurativa? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:338-345.

- Butt M, Sisic M, Silva C, et al. The associations of depression and coping methods on health-related quality of life for those with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1137-1139.

- Calao M, Wilson JL, Spelman L, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) prevalence, demographics and management pathways in Australia: a population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200683.

- Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, et al. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:917-924.

- Kimball AB, Sundaram M, Gauthier G, et al. The comorbidity burden of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a claims data analysis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2018;8:557.

- Thorlacius L, Cohen AD, Gislason GH, et al. Increased suicide risk in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:52-57.

- Tiri H, Jokelainen J, Timonen M, et al. Somatic and psychiatric comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:514-519.

- Huilaja L, Tiri H, Jokelainen J, et al. Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa have a high psychiatric disease burden: a Finnish nationwide registry study. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:46-51.

- Kirby JS, Butt M, Esmann S, et al. Association of resilience with depression and health-related quality of life for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1263.

- Egeberg A, Gislason GH, Hansen PR. Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:429-434.

- Vangipuram R, Vaidya T, Jandarov R, et al. Factors contributing to depression and chronic pain in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from a single-center retrospective review. Dermatology. 2016;232:692-695.

- Rayner L, Jackson K, Turner M, et al. Integrated mental health assessment in a tertiary medical dermatology service: feasibility and the prevalence of common mental disorder. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:201.

- Shavit E, Dreiher J, Freud T, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in 3207 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online June 9, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:371-376.

- Kurek A, Johanne Peters EM, Sabat R, et al. Depression is a frequent co-morbidity in patients with acne inversa. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:743-749.

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97.

- Onderdijk AJ, Van Der Zee HH, Esmann S, et al. Depression in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online February 20, 2012]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:473-478.

- Matusiak Ł, Bieniek A, Szepietowski JC. Psychophysical aspects of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:264-268.

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617-627.

- Holahan CJ, Pahl SA, Cronkite RC, et al. Depression and vulnerability to incident physical illness across 10 years. J Affect Disord. 2009;123:222-229.

- Deckers IE, Janse IC, van der Zee HH, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is associated with low socioeconomic status (SES): a cross-sectional reference study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:755-759.e1.

- Williams MT, Skinta MD, Kanter JW, et al. A qualitative study of microaggressions against African Americans on predominantly White campuses. BMC Psychol. 2020;8:1-13.

- Dunlop DD, Song J, Lyons JS, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in rates of depression among preretirement adults. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1945-1952.

- Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35:407-411.

- Williams DR, González HM, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:305-315.

- Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283:506-511.

- Kromann CB, Deckers IE, Esmann S, et al. Risk factors, clinical course and long-term prognosis in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:819-824.

- Sivanand A, Gulliver WP, Josan CK, et al. Weight loss and dietary interventions for hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg . 2020;24:64-72.

- Raedler TJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in major depressive disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:519-525.

- Rocha VZ, Libby P. Obesity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:399-409.

- Davidson KW, Schwartz JE, Kirkland SA, et al. Relation of inflammation to depression and incident coronary heart disease (from the Canadian Nova Scotia Health Survey [NSHS95] Prospective Population Study). Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:755-761.

- González-López MA, Ocejo-Viñals JG, Mata C, et al. Evaluation of serum omentin-1 and apelin concentrations in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:450-454.

- Taylor VH, Macqueen GM. The role of adipokines in understanding the associations between obesity and depression. J Obes. 2010;2010:748048.

- Setayesh L, Ebrahimi R, Pooyan S, et al. The possible mediatory role of adipokines in the association between low carbohydrate diet and depressive symptoms among overweight and obese women. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0257275 .

- Andriano TM, Benesh G, Babbush KM, et al. Serum inflammatory markers and leukocyte profiles accurately describe hidradenitis suppurativa disease severity. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1270-1275.

- Montaudié H, Seitz-Polski B, Cornille A, et al. Interleukin 6 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein are potential predictive markers of response to infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;6:156-158.

- Colasanto M, Madigan S, Korczak DJ. Depression and inflammation among children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:940-948.

- Crowley JJ, Mekkes JR, Zouboulis CC, et al. Association of hidradenitis suppurativa disease severity with increased risk for systemic comorbidities. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:1561-1565.

- Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:105-115.

- Sabat R, Jemec GBE, Matusiak Ł, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2020;6:1-20.

- Wolk K, Warszawska K, Hoeflich C, et al. Deficiency of IL-22 contributes to a chronic inflammatory disease: pathogenetic mechanisms in acne inversa. J Immunol. 2011;186:1228-1239.

- von Laffert M, Helmbold P, Wohlrab J, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (acne inversa): early inflammatory events at terminal follicles and at interfollicular epidermis. Exp Dermatol. 2010;19:533-537.

- Van Der Zee HH, De Ruiter L, Van Den Broecke DG, et al. Elevated levels of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-10 in hidradenitis suppurativa skin: a rationale for targeting TNF-α and IL-1β. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1292-1298.

- Schlapbach C, Hänni T, Yawalkar N, et al. Expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in lesions of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:790-798.

- Kelly G, Hughes R, McGarry T, et al. Dysregulated cytokine expression in lesional and nonlesional skin in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1431-1439.

- Jemec GBE, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa: epidemiology and scope of the problem. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5 Suppl 1):S4-S7.

- Garg A, Kirby JS, Lavian J, et al. Sex- and age-adjusted population analysis of prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:760-764.

- Soliman YS, Hoffman LK, Guzman AK, et al. African American patients with hidradenitis suppurativa have significant health care disparities: a retrospective study. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:334-336.

- Garg A, Malviya N, Strunk A, et al. Comorbidity screening in hidradenitis suppurativa: evidence-based recommendations from the US and Canadian Hidradenitis Suppurativa Foundations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1092-1101.

- Beatriz Currier M, Nemeroff CB. Inflammation and mood disorders: proinflammatory cytokines and the pathogenesis of depression. Antiinflamm Antiallergy Agents Med Chem. 2012;9:212-220.

- Wright S, Strunk A, Garg A. Prevalence of depression among children, adolescents, and adults with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:55-60.

- Sampogna F, Fania L, Mastroeni S, et al. Correlation between depression, quality of life and clinical severity in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2020;100:1-6.

- Theut Riis P, Pedersen OB, Sigsgaard V, et al. Prevalence of patients with self-reported hidradenitis suppurativa in a cohort of Danish blood donors: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:774-781.

- Senthilnathan A, Kolli SS, Cardwell LA, et al. Depression in hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:1087-1088.

- Pavon Blanco A, Turner MA, Petrof G, et al. To what extent do disease severity and illness perceptions explain depression, anxiety and quality of life in hidradenitis suppurativa? Br J Dermatol. 2019;180:338-345.

- Butt M, Sisic M, Silva C, et al. The associations of depression and coping methods on health-related quality of life for those with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1137-1139.

- Calao M, Wilson JL, Spelman L, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) prevalence, demographics and management pathways in Australia: a population-based cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200683.

- Ingram JR, Jenkins-Jones S, Knipe DW, et al. Population-based Clinical Practice Research Datalink study using algorithm modelling to identify the true burden of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol. 2018;178:917-924.

- Kimball AB, Sundaram M, Gauthier G, et al. The comorbidity burden of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a claims data analysis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2018;8:557.

- Thorlacius L, Cohen AD, Gislason GH, et al. Increased suicide risk in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:52-57.

- Tiri H, Jokelainen J, Timonen M, et al. Somatic and psychiatric comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:514-519.

- Huilaja L, Tiri H, Jokelainen J, et al. Patients with hidradenitis suppurativa have a high psychiatric disease burden: a Finnish nationwide registry study. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:46-51.

- Kirby JS, Butt M, Esmann S, et al. Association of resilience with depression and health-related quality of life for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:1263.

- Egeberg A, Gislason GH, Hansen PR. Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:429-434.

- Vangipuram R, Vaidya T, Jandarov R, et al. Factors contributing to depression and chronic pain in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from a single-center retrospective review. Dermatology. 2016;232:692-695.

- Rayner L, Jackson K, Turner M, et al. Integrated mental health assessment in a tertiary medical dermatology service: feasibility and the prevalence of common mental disorder. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:201.

- Shavit E, Dreiher J, Freud T, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities in 3207 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online June 9, 2014]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:371-376.

- Kurek A, Johanne Peters EM, Sabat R, et al. Depression is a frequent co-morbidity in patients with acne inversa. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:743-749.

- Vazquez BG, Alikhan A, Weaver AL, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa and associated factors: a population-based study of Olmsted County, Minnesota. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:97.

- Onderdijk AJ, Van Der Zee HH, Esmann S, et al. Depression in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa [published online February 20, 2012]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:473-478.

- Matusiak Ł, Bieniek A, Szepietowski JC. Psychophysical aspects of hidradenitis suppurativa. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:264-268.

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617-627.

- Holahan CJ, Pahl SA, Cronkite RC, et al. Depression and vulnerability to incident physical illness across 10 years. J Affect Disord. 2009;123:222-229.

- Deckers IE, Janse IC, van der Zee HH, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is associated with low socioeconomic status (SES): a cross-sectional reference study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:755-759.e1.

- Williams MT, Skinta MD, Kanter JW, et al. A qualitative study of microaggressions against African Americans on predominantly White campuses. BMC Psychol. 2020;8:1-13.

- Dunlop DD, Song J, Lyons JS, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in rates of depression among preretirement adults. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1945-1952.

- Williams DR, Priest N, Anderson NB. Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: patterns and prospects. Health Psychol. 2016;35:407-411.

- Williams DR, González HM, Neighbors H, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:305-315.

- Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283:506-511.

- Kromann CB, Deckers IE, Esmann S, et al. Risk factors, clinical course and long-term prognosis in hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional study. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171:819-824.

- Sivanand A, Gulliver WP, Josan CK, et al. Weight loss and dietary interventions for hidradenitis suppurativa: a systematic review. J Cutan Med Surg . 2020;24:64-72.

- Raedler TJ. Inflammatory mechanisms in major depressive disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2011;24:519-525.

- Rocha VZ, Libby P. Obesity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2009;6:399-409.

- Davidson KW, Schwartz JE, Kirkland SA, et al. Relation of inflammation to depression and incident coronary heart disease (from the Canadian Nova Scotia Health Survey [NSHS95] Prospective Population Study). Am J Cardiol. 2009;103:755-761.

- González-López MA, Ocejo-Viñals JG, Mata C, et al. Evaluation of serum omentin-1 and apelin concentrations in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2021;38:450-454.

- Taylor VH, Macqueen GM. The role of adipokines in understanding the associations between obesity and depression. J Obes. 2010;2010:748048.

- Setayesh L, Ebrahimi R, Pooyan S, et al. The possible mediatory role of adipokines in the association between low carbohydrate diet and depressive symptoms among overweight and obese women. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0257275 .

- Andriano TM, Benesh G, Babbush KM, et al. Serum inflammatory markers and leukocyte profiles accurately describe hidradenitis suppurativa disease severity. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:1270-1275.

- Montaudié H, Seitz-Polski B, Cornille A, et al. Interleukin 6 and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein are potential predictive markers of response to infliximab in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;6:156-158.

- Colasanto M, Madigan S, Korczak DJ. Depression and inflammation among children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2020;277:940-948.

Practice Points

- Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is known to be associated with systemic inflammation and comorbidities, including depression.

- Depression may be a potential contributing factor to HS in affected patients, and studies on HS with comorbid depression in patients with skin of color are lacking.

Adherence to Topical Treatment Can Improve Treatment-Resistant Moderate Psoriasis

High-potency topical corticosteroids are first-line treatments for psoriasis, but many patients report that they are ineffective or lose effectiveness over time.1-5 The mechanism underlying the lack or loss of activity is not well characterized but may be due to poor adherence to treatment. Adherence to topical treatment is poor in the short run and even worse in the long run.6,7 We evaluated 12 patients with psoriasis resistant to topical corticosteroids to determine if they would respond to topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote adherence to treatment.

Methods

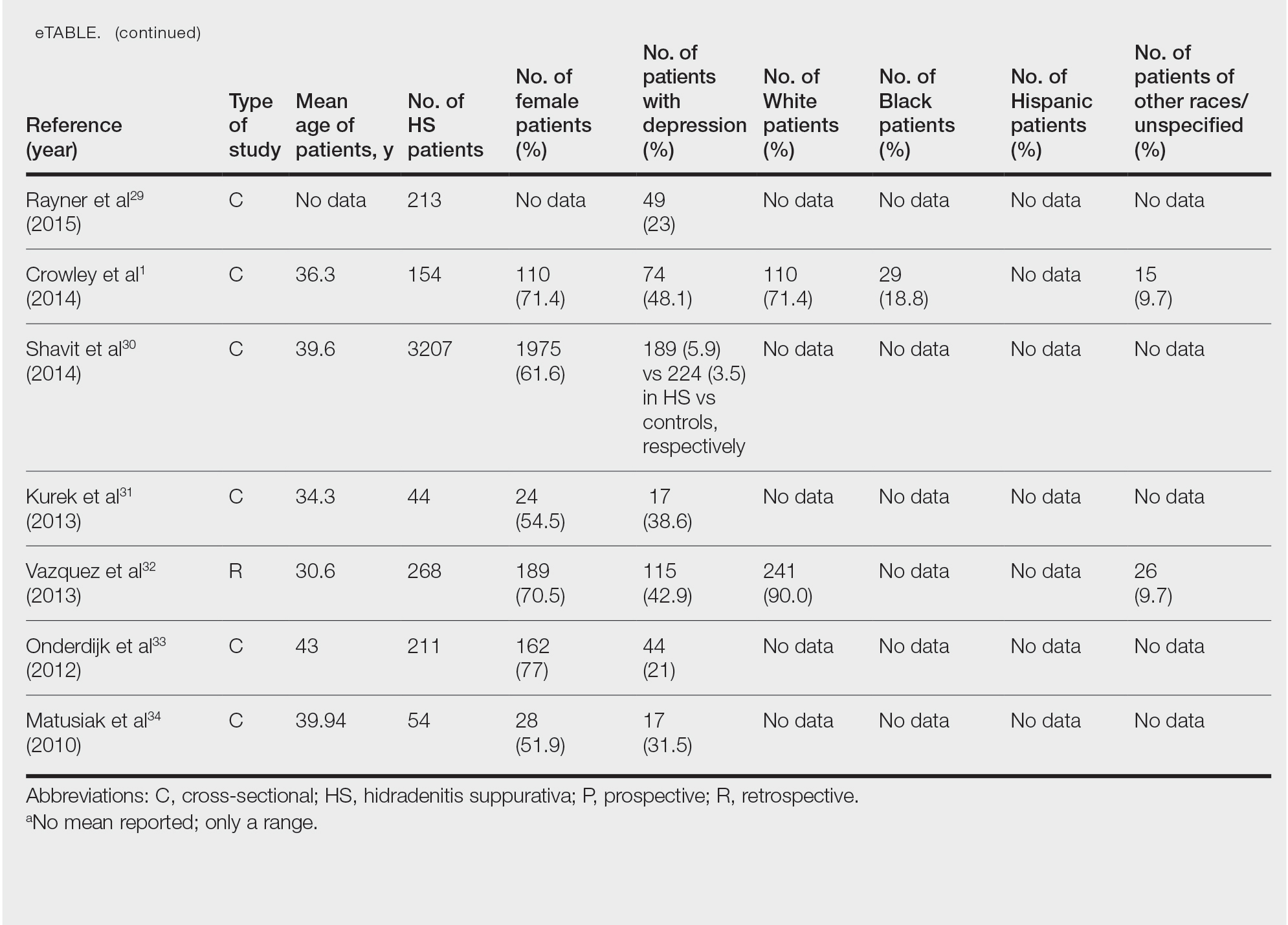

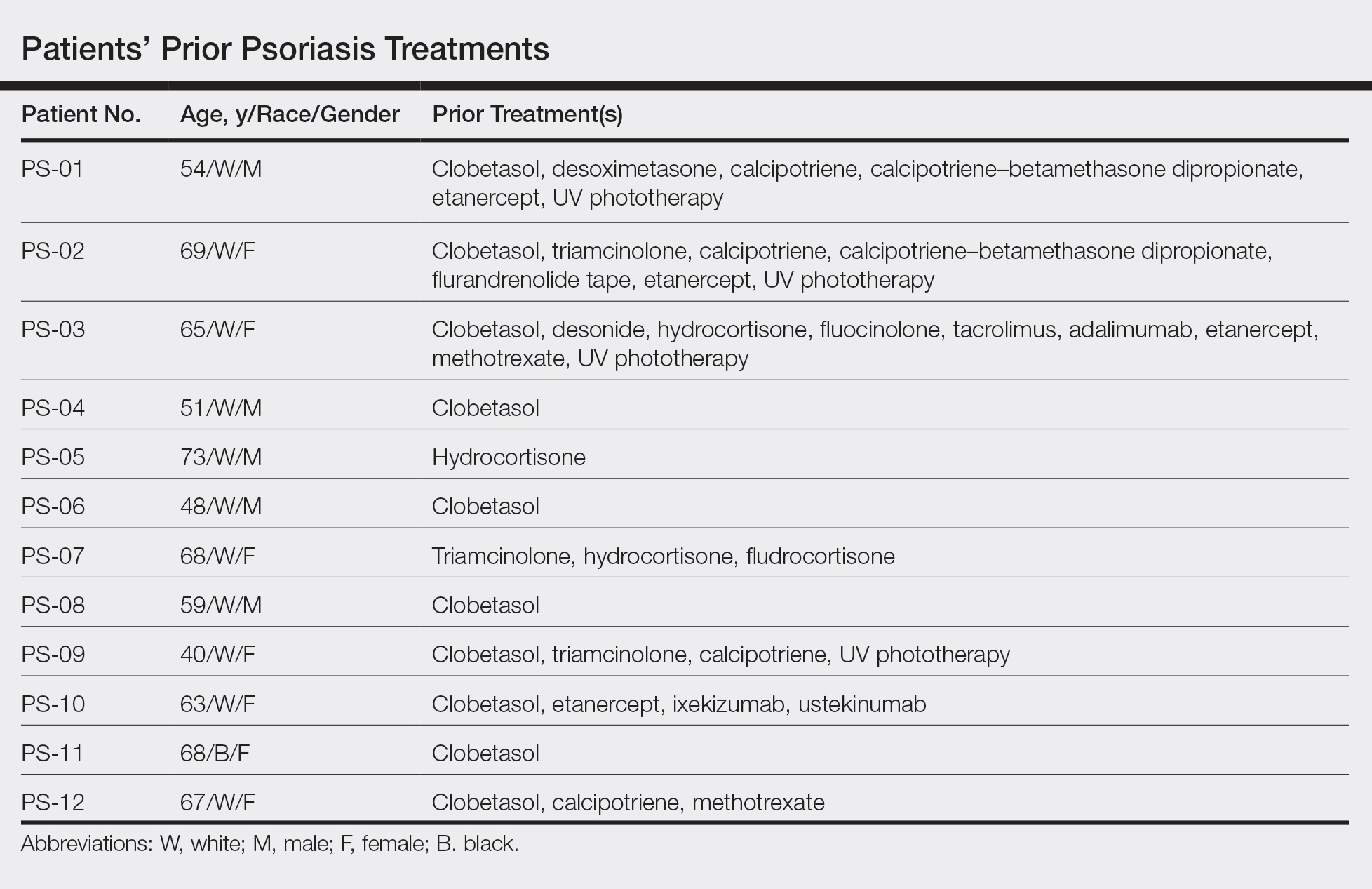

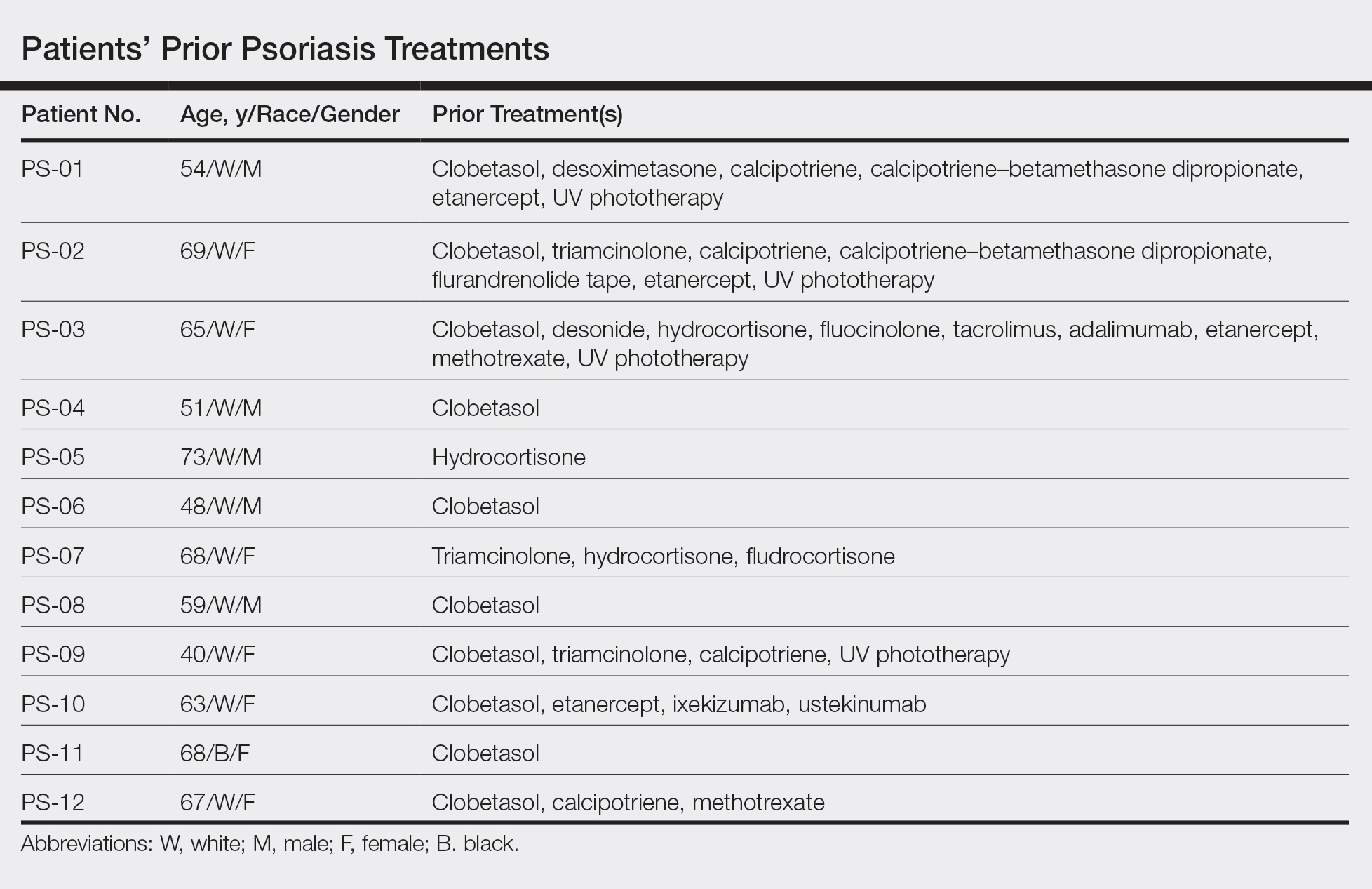

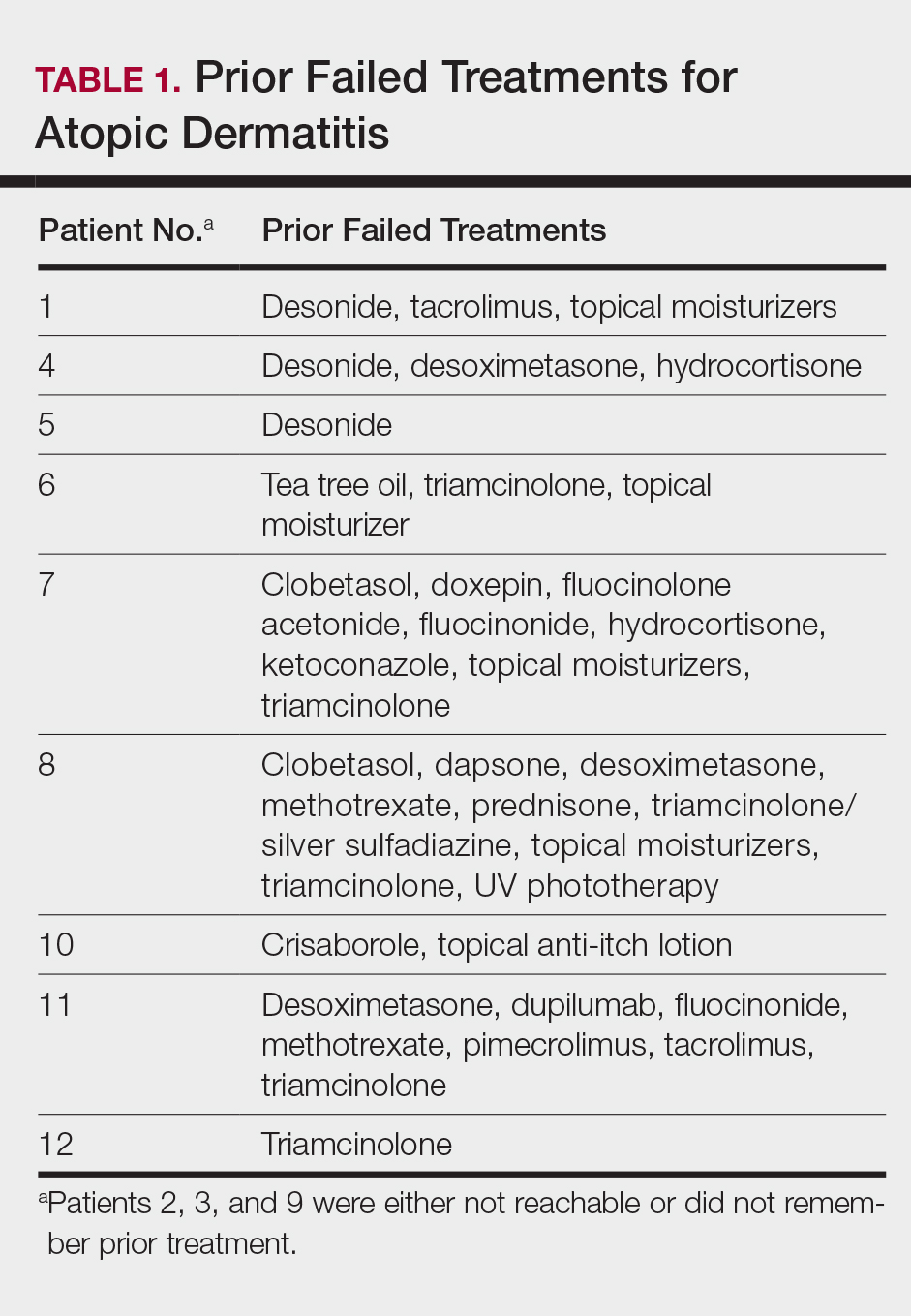

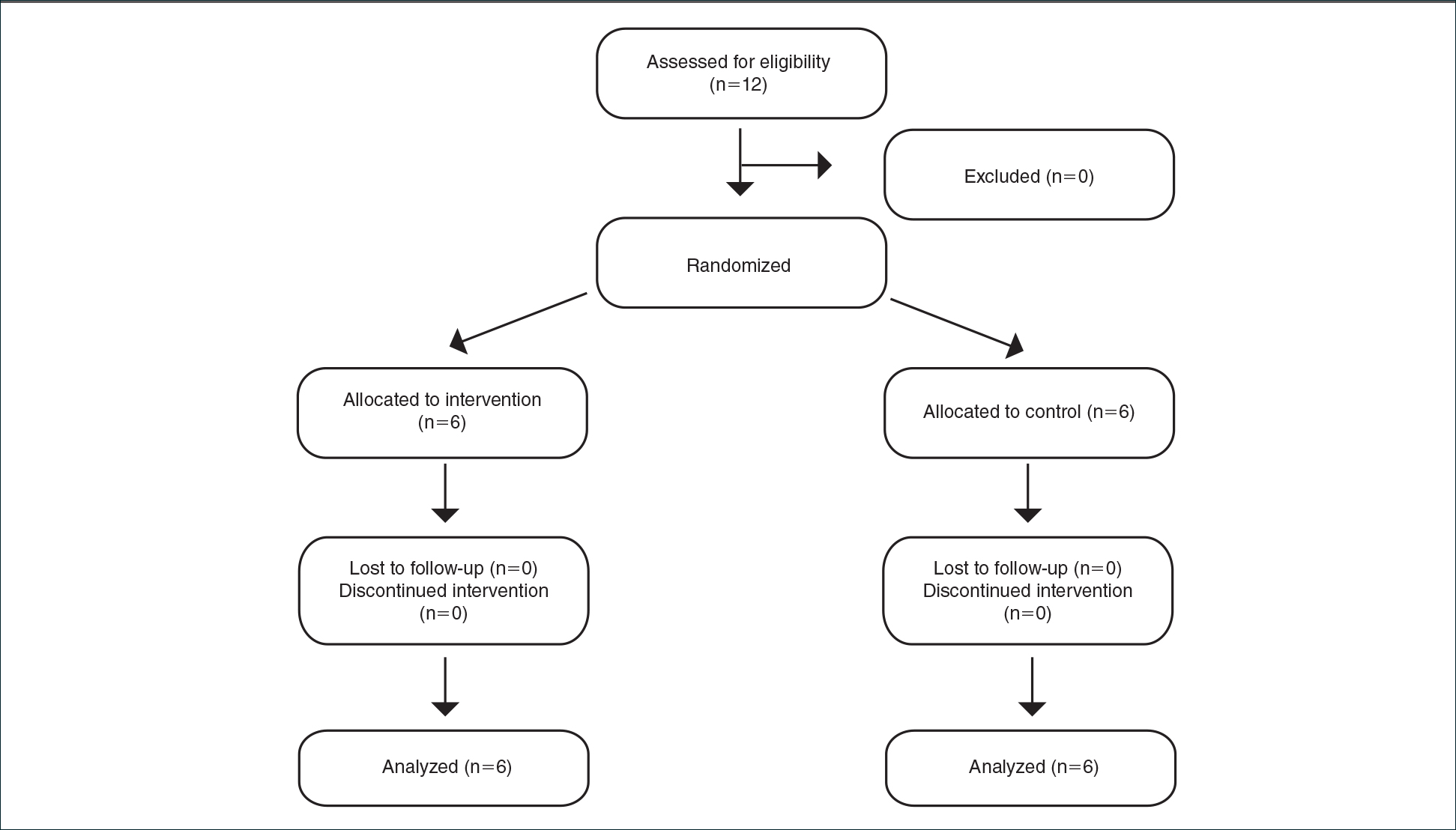

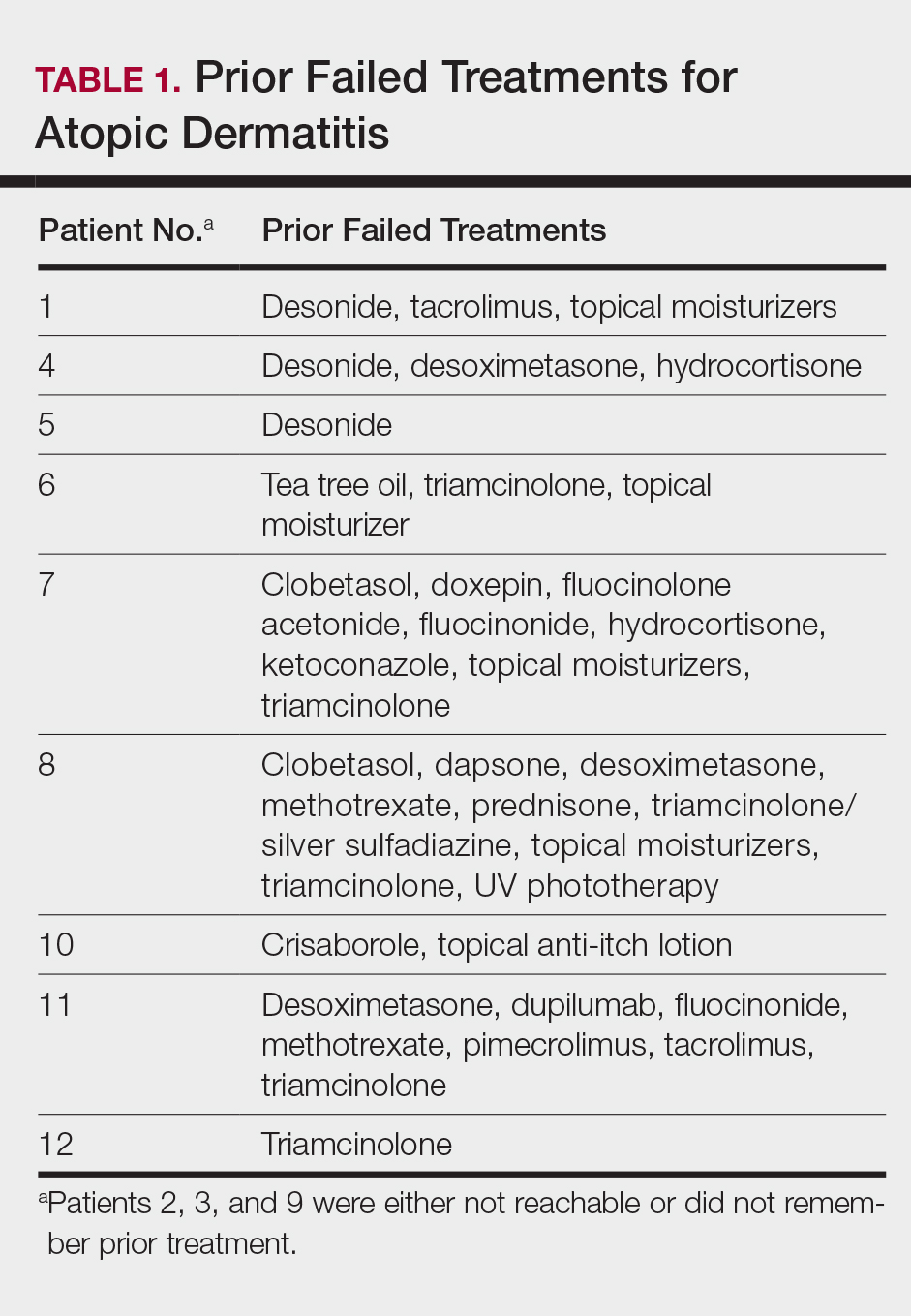

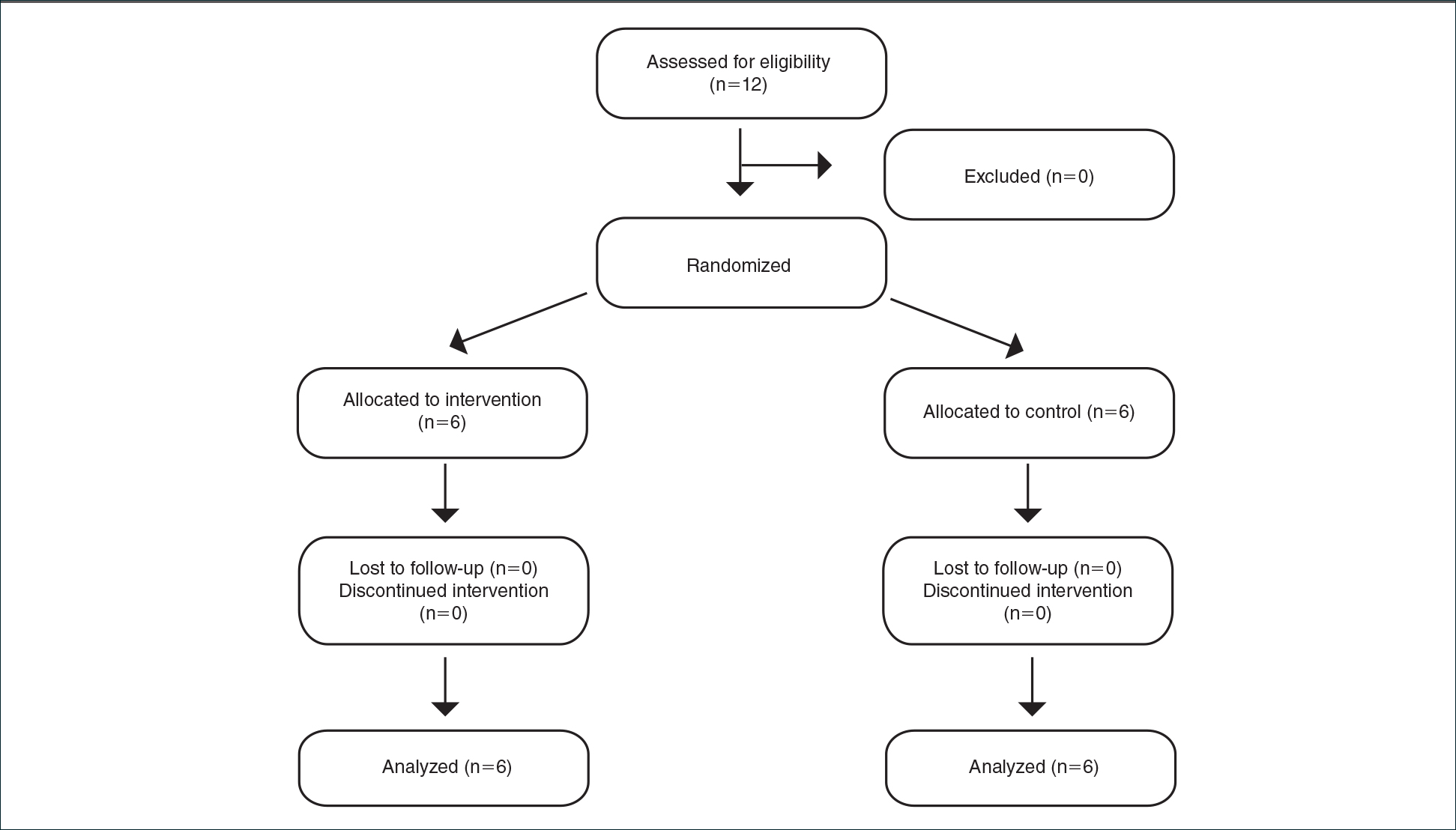

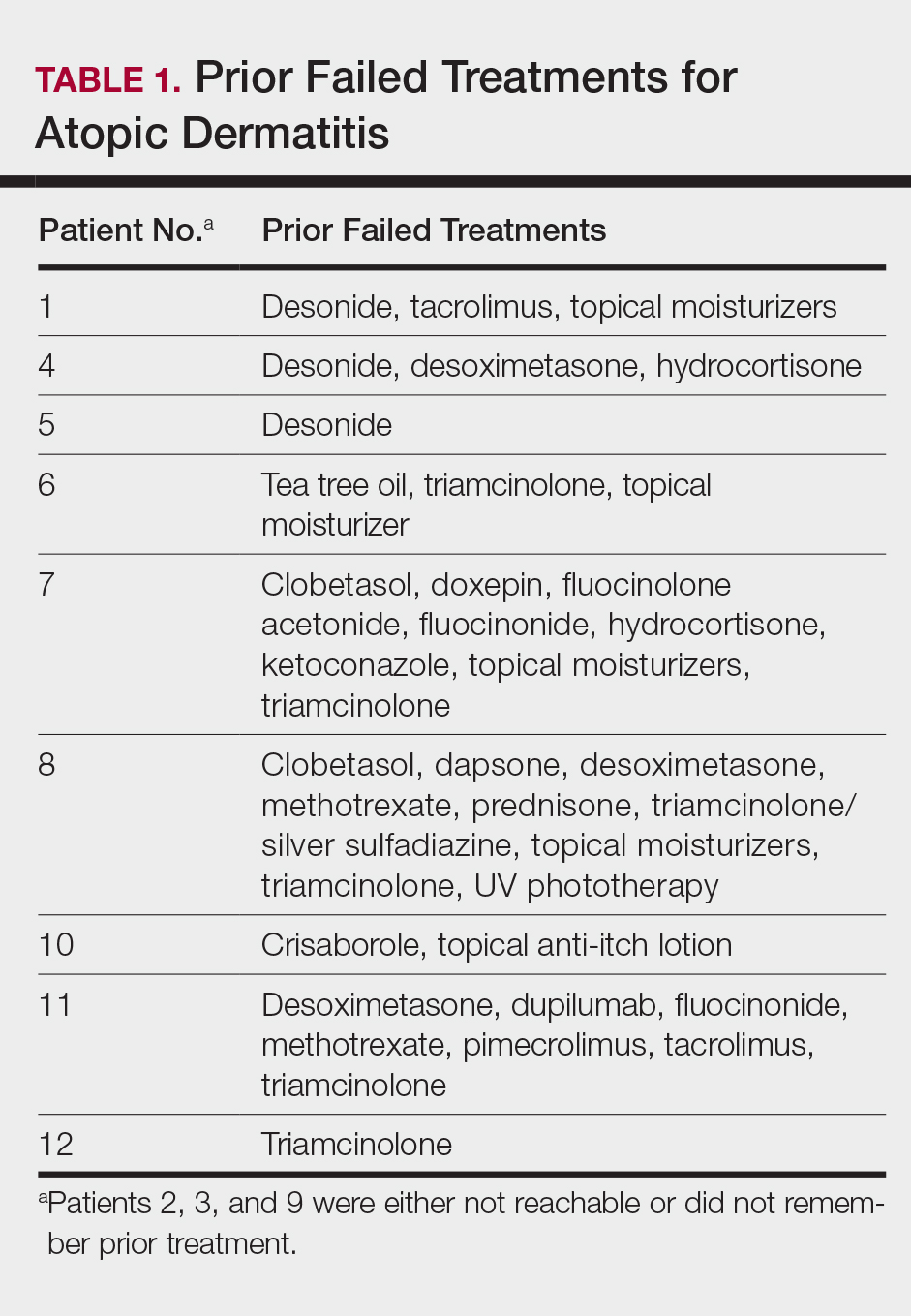

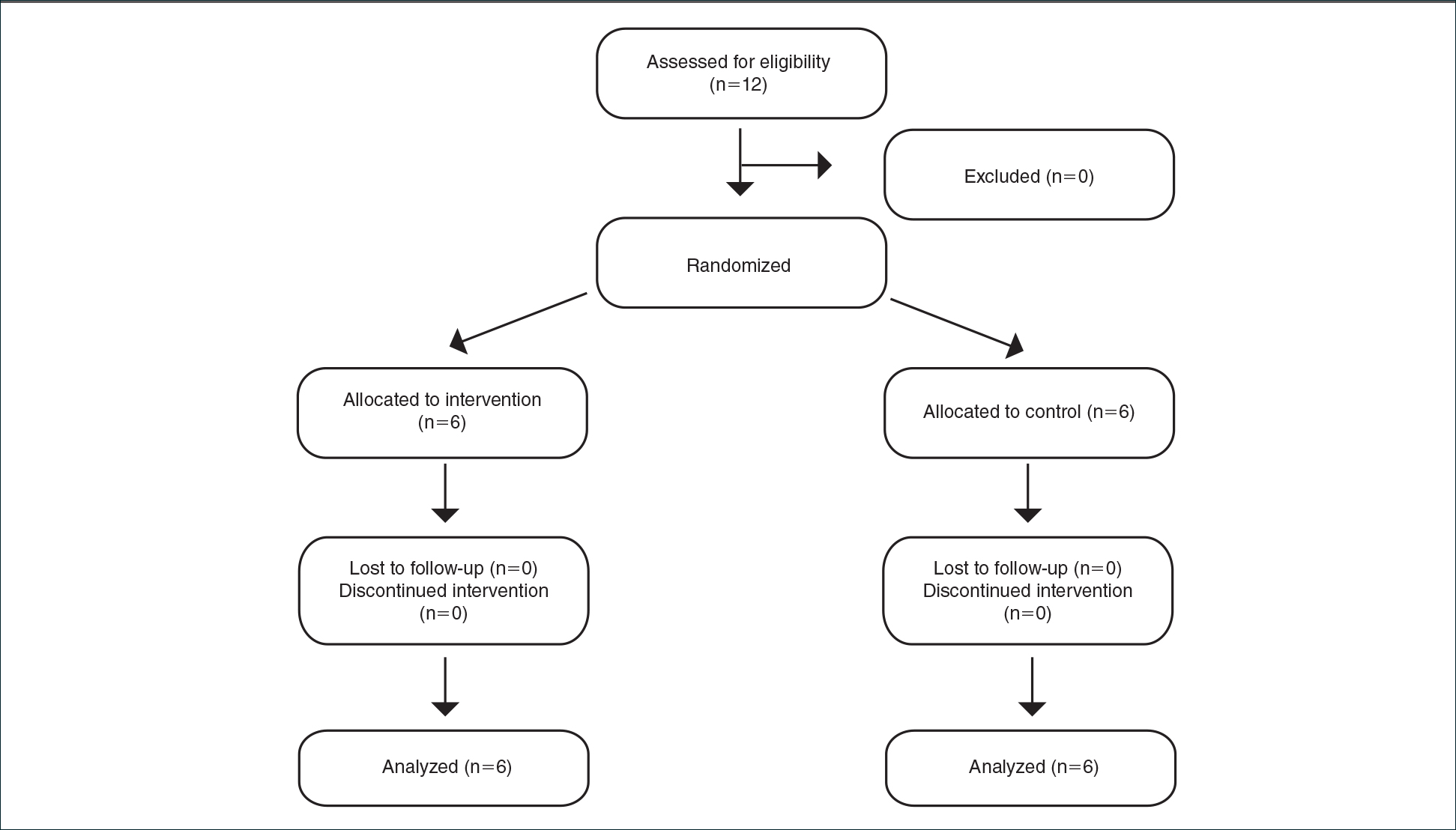

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study recruited 12 patients with plaque psoriasis that previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids and other therapies (Table). We stratified disease by body surface area: mild (<3%), moderate (3%–10%), and severe (>10%). Inclusion criteria included adult patients with plaque psoriasis amenable to topical corticosteroid therapy, ability to comply with requirements of the study, and a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment (Figure). Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, breastfeeding, had conditions that would affect adherence or potentially bias results (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), had a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and had a history of drug hypersensitivity.

All patients received desoximetasone spray 0.25% twice daily for 14 days. At the baseline visit, 6 patients were randomly selected to also receive a twice-daily reminder telephone call. Study visits occurred frequently—at baseline and on days 3, 7, and 14—to further assure good adherence to the treatment regimen.

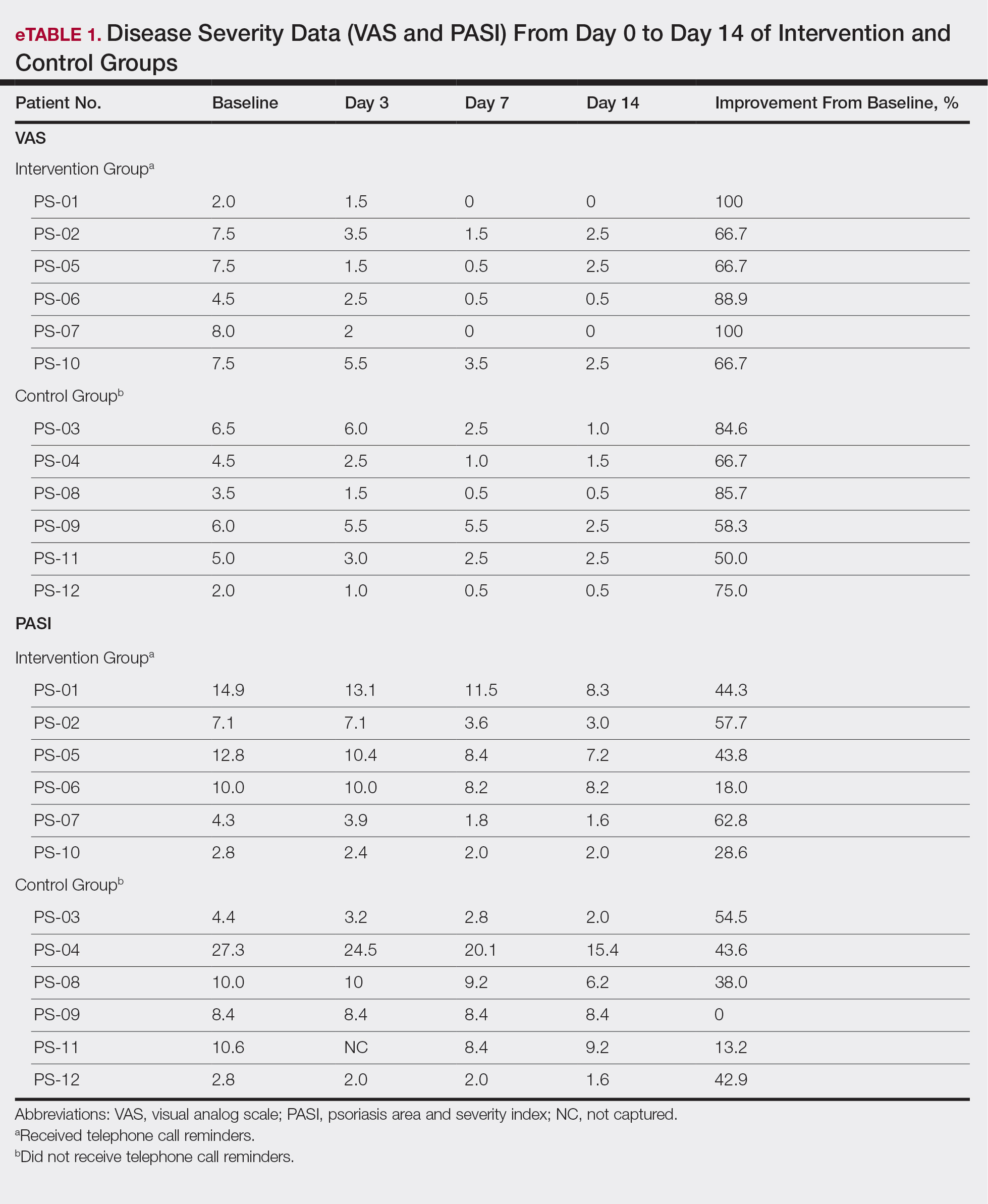

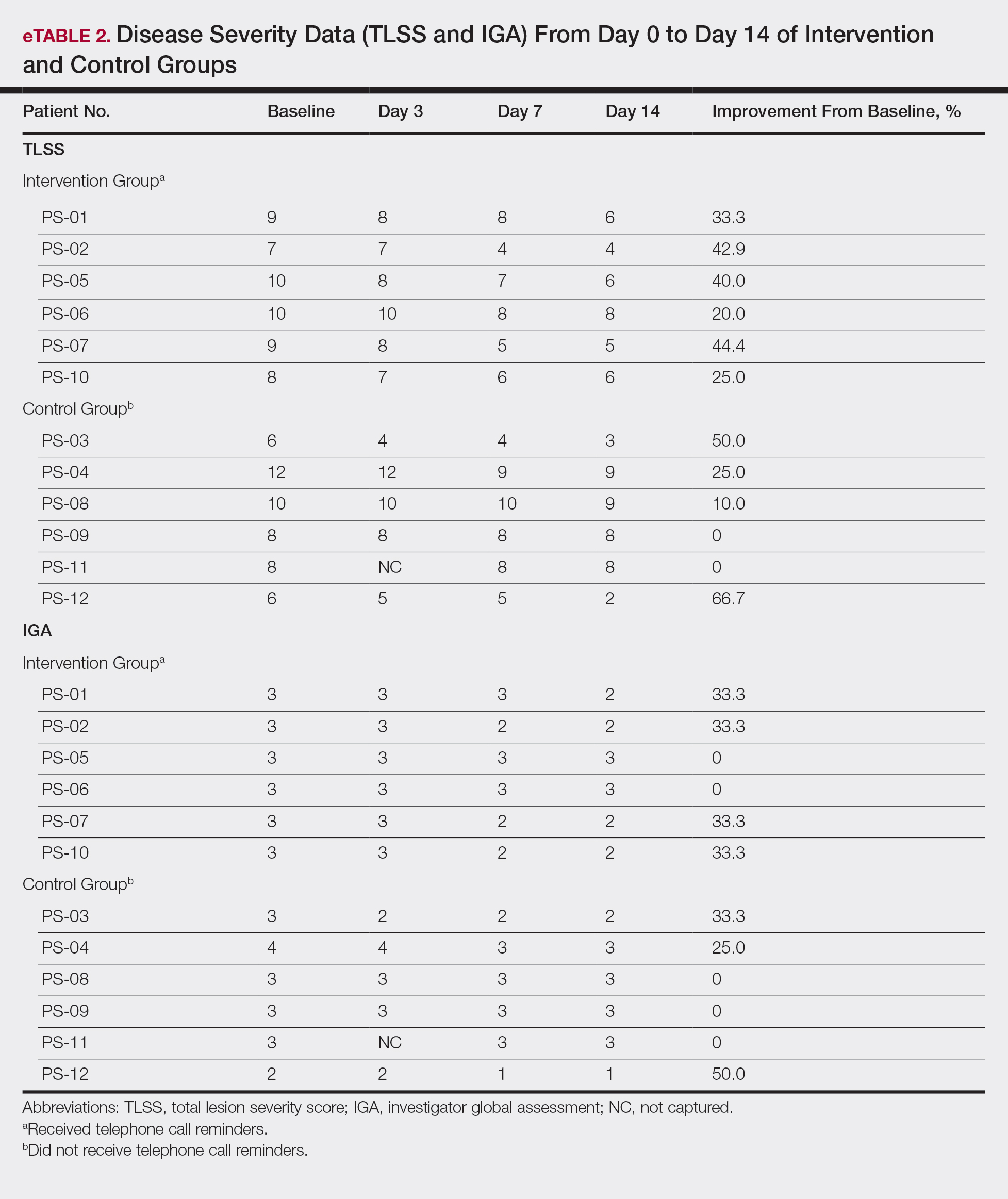

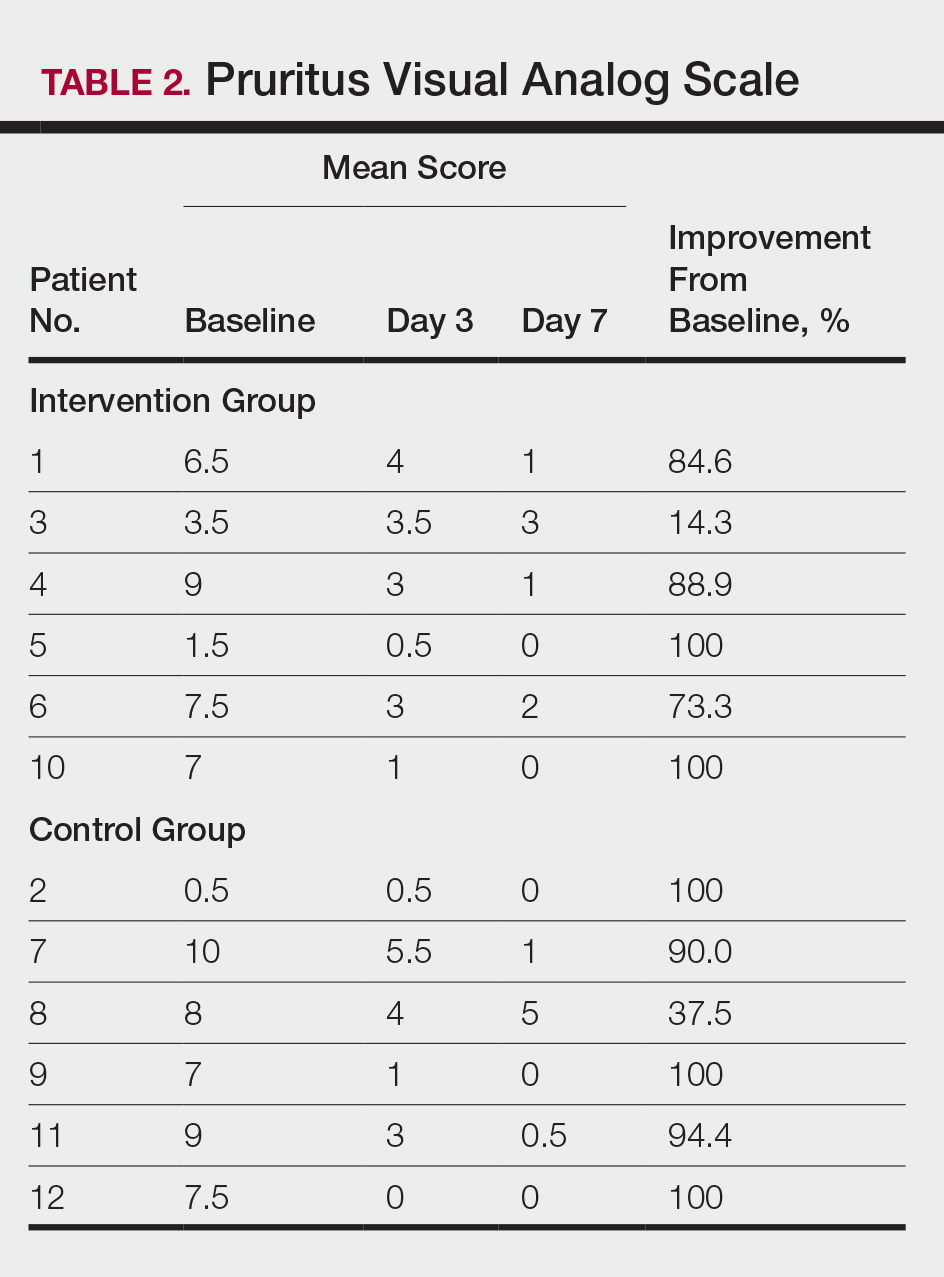

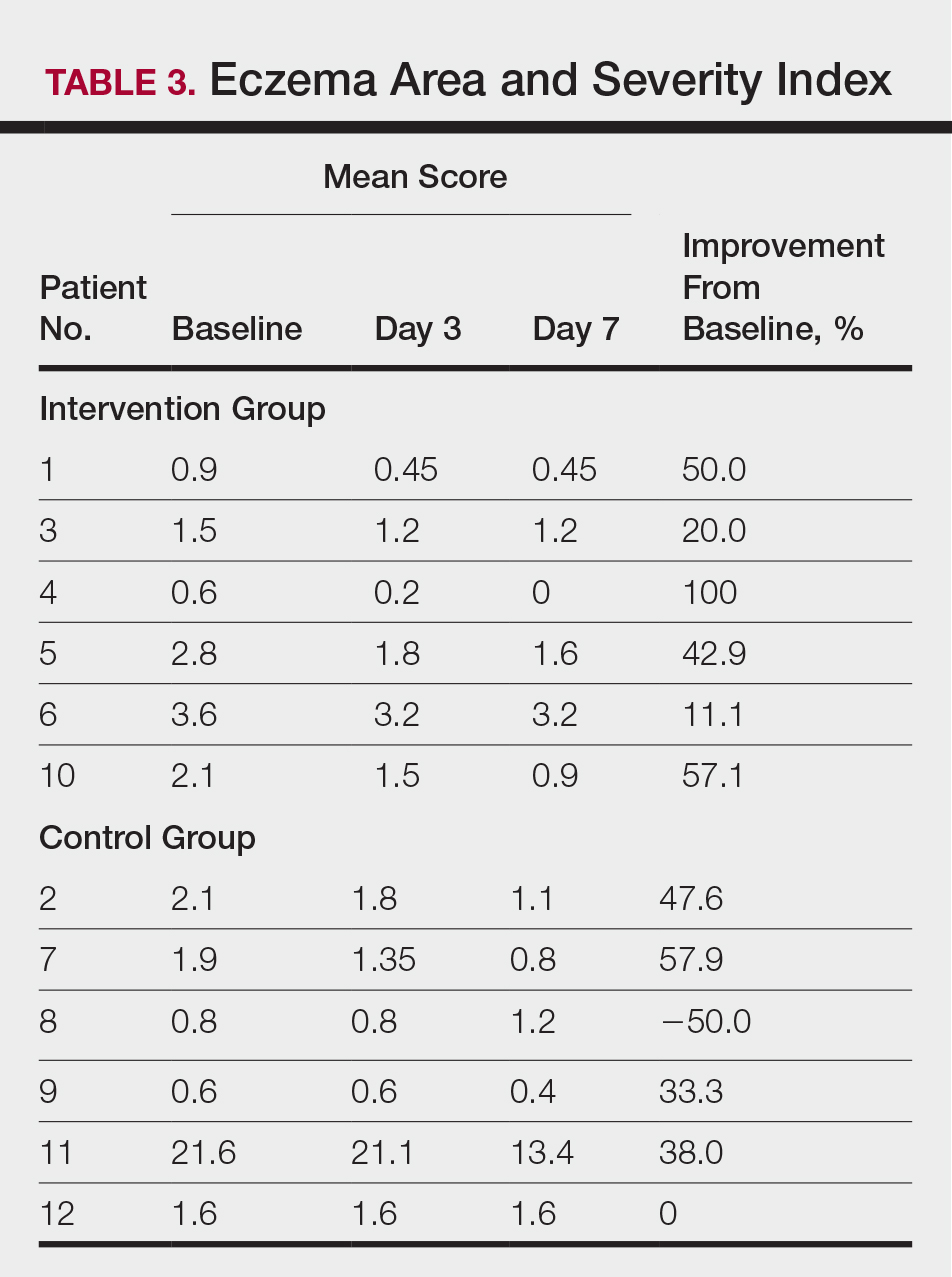

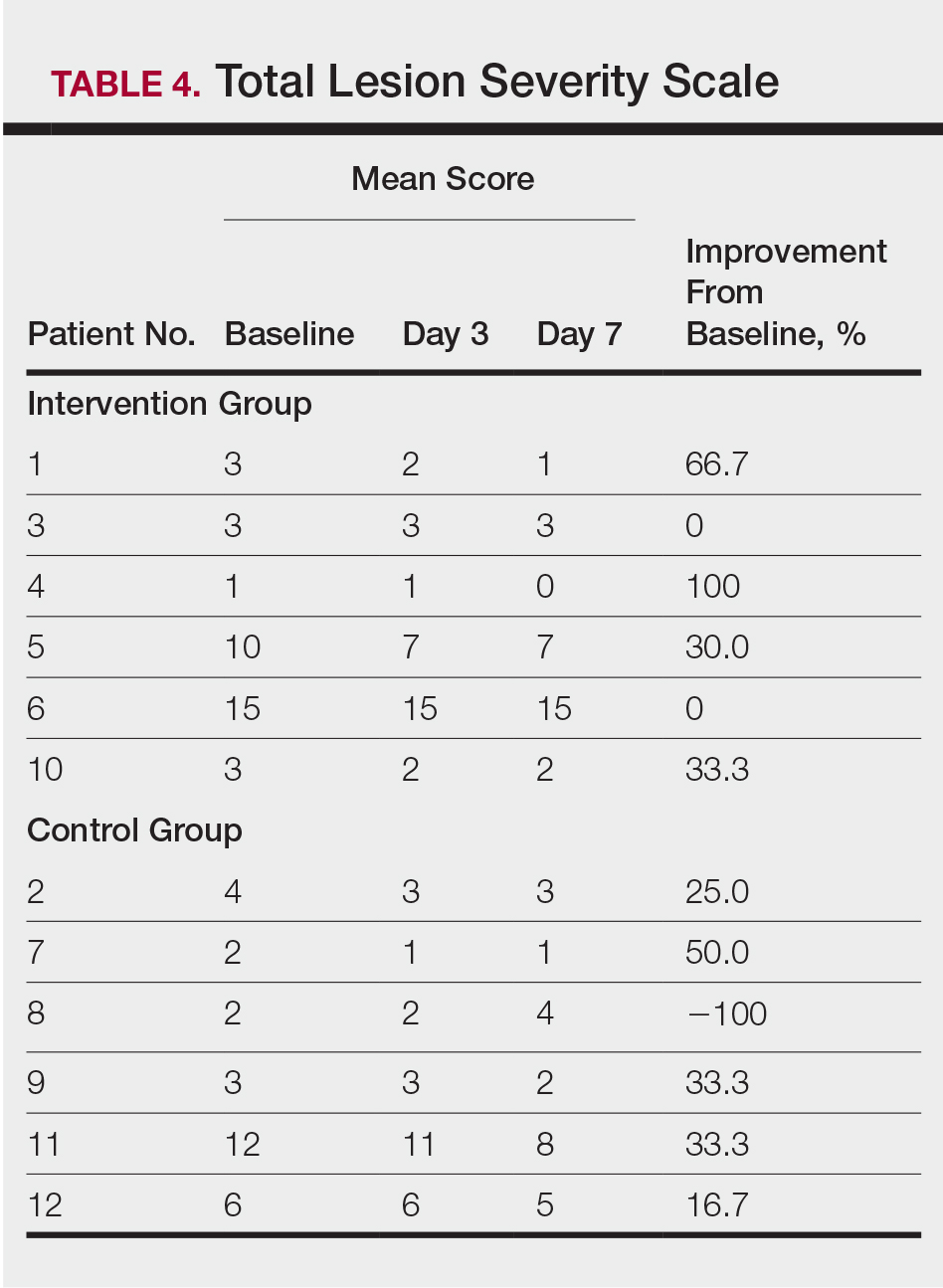

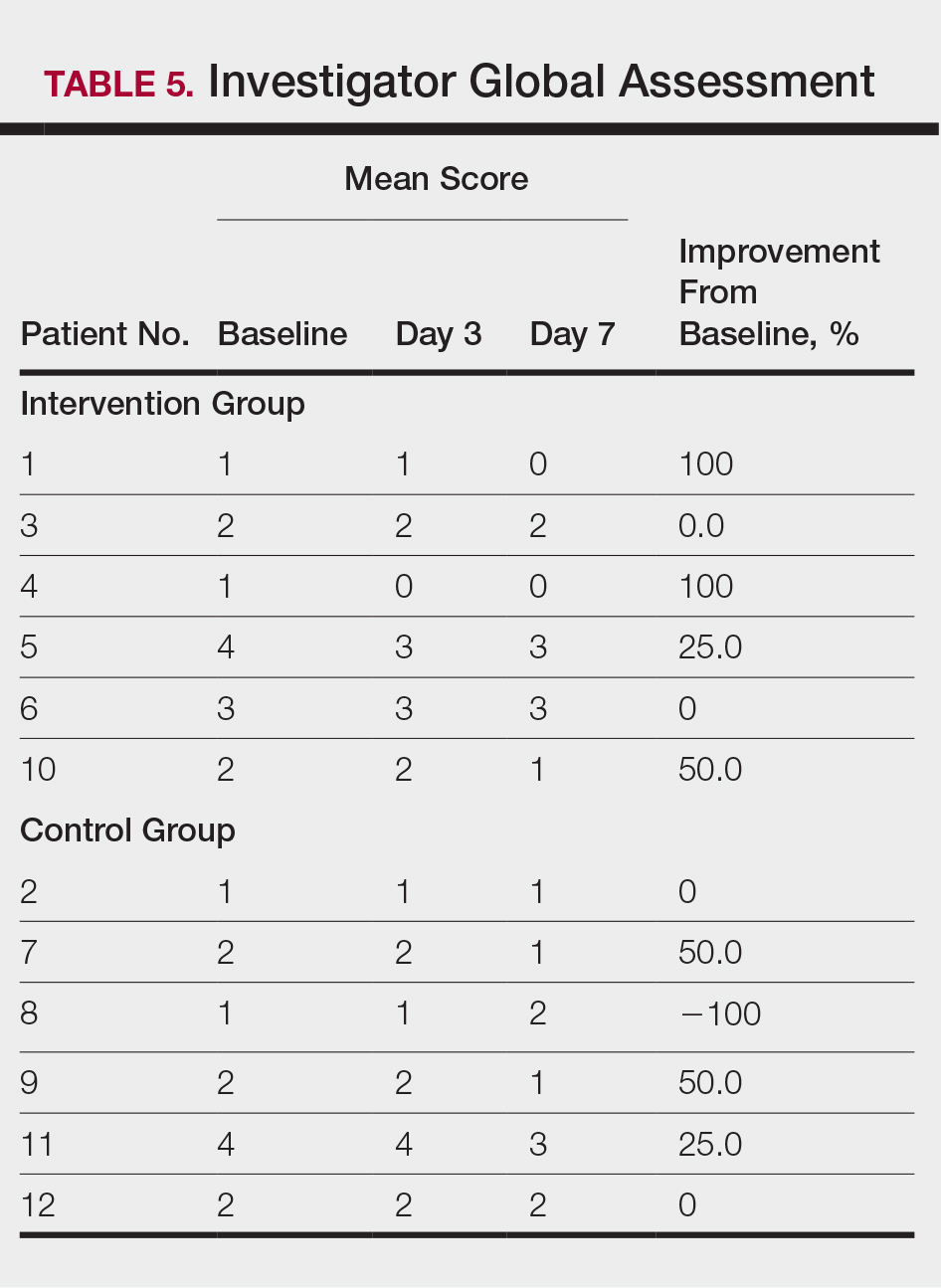

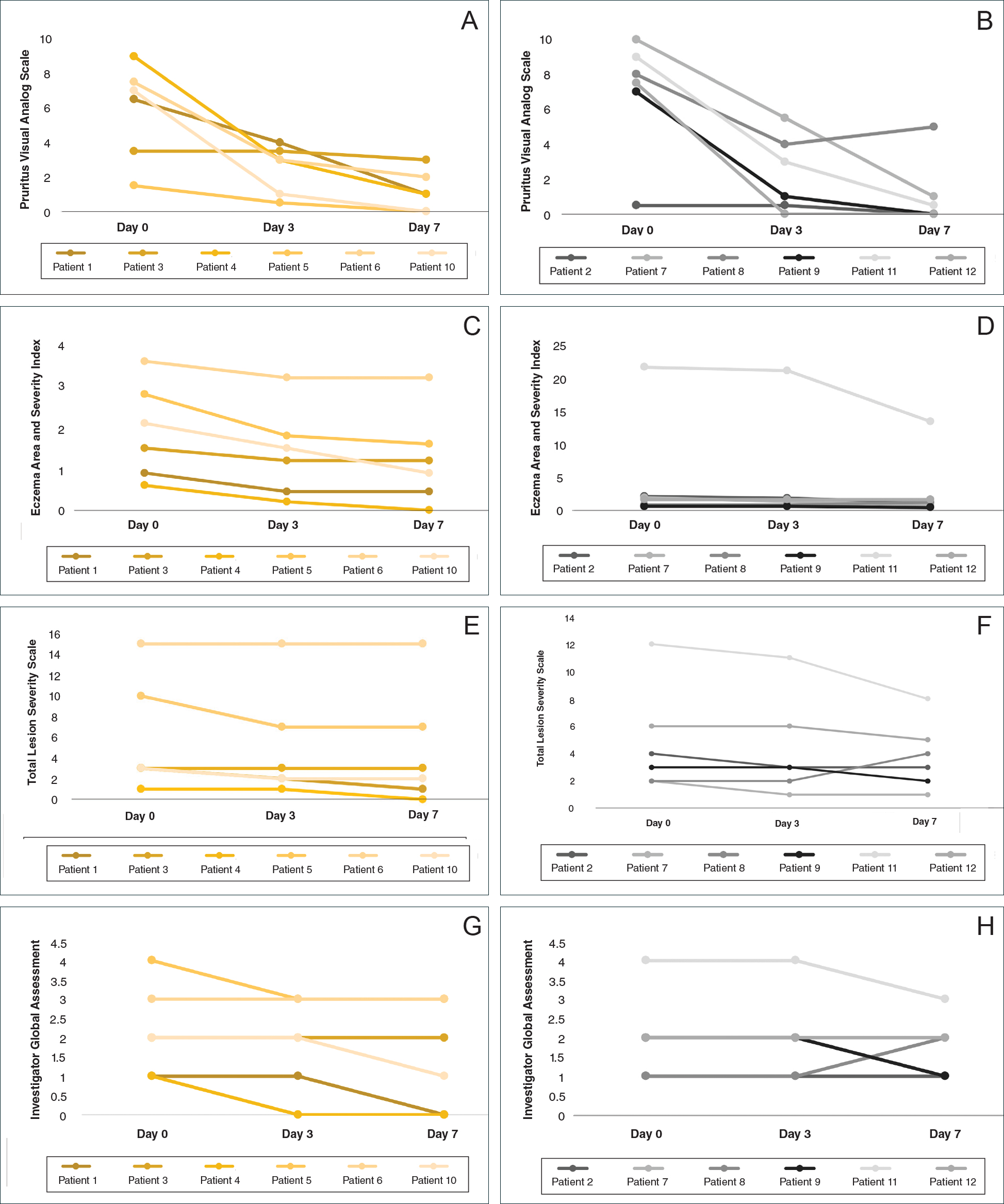

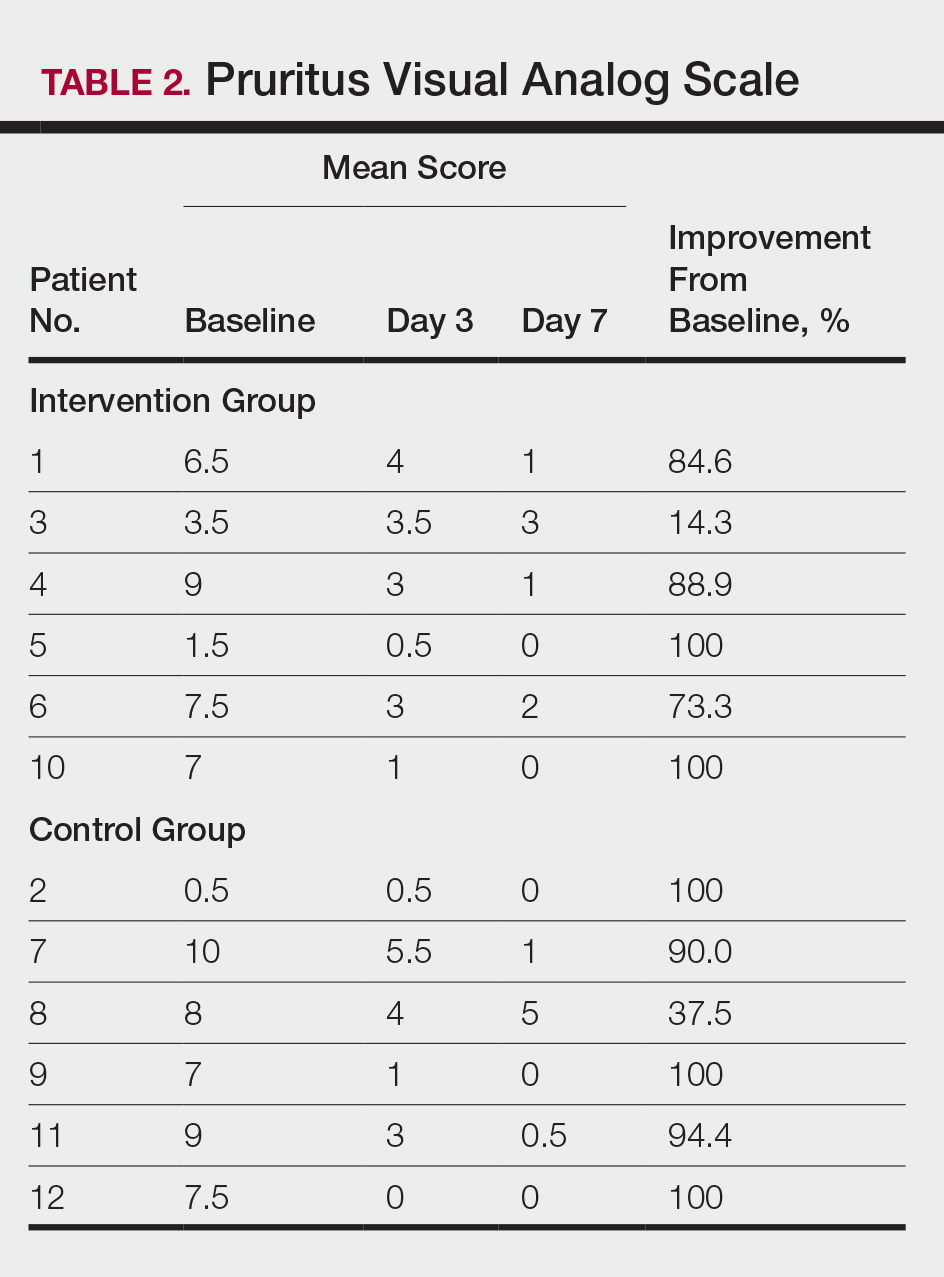

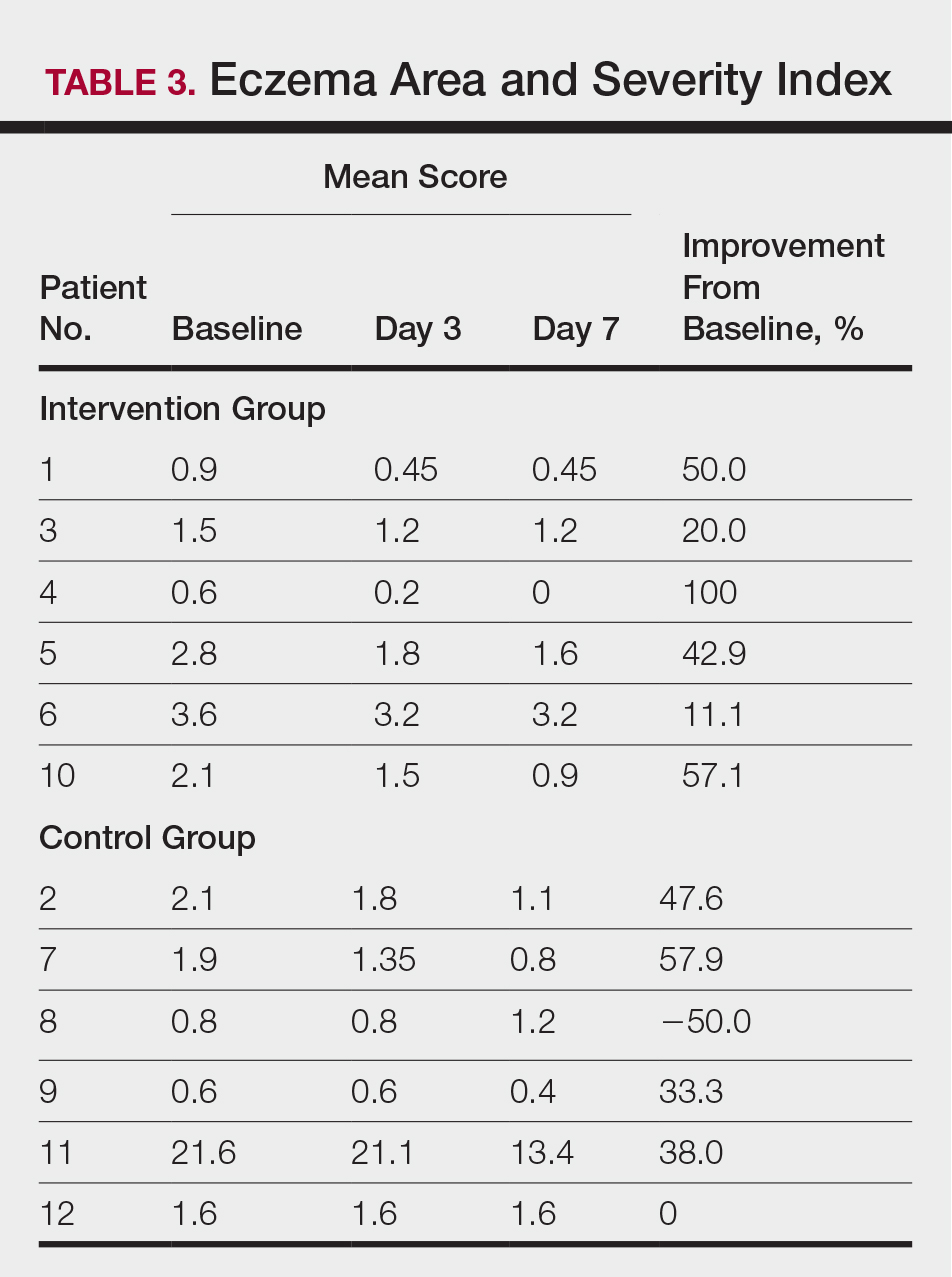

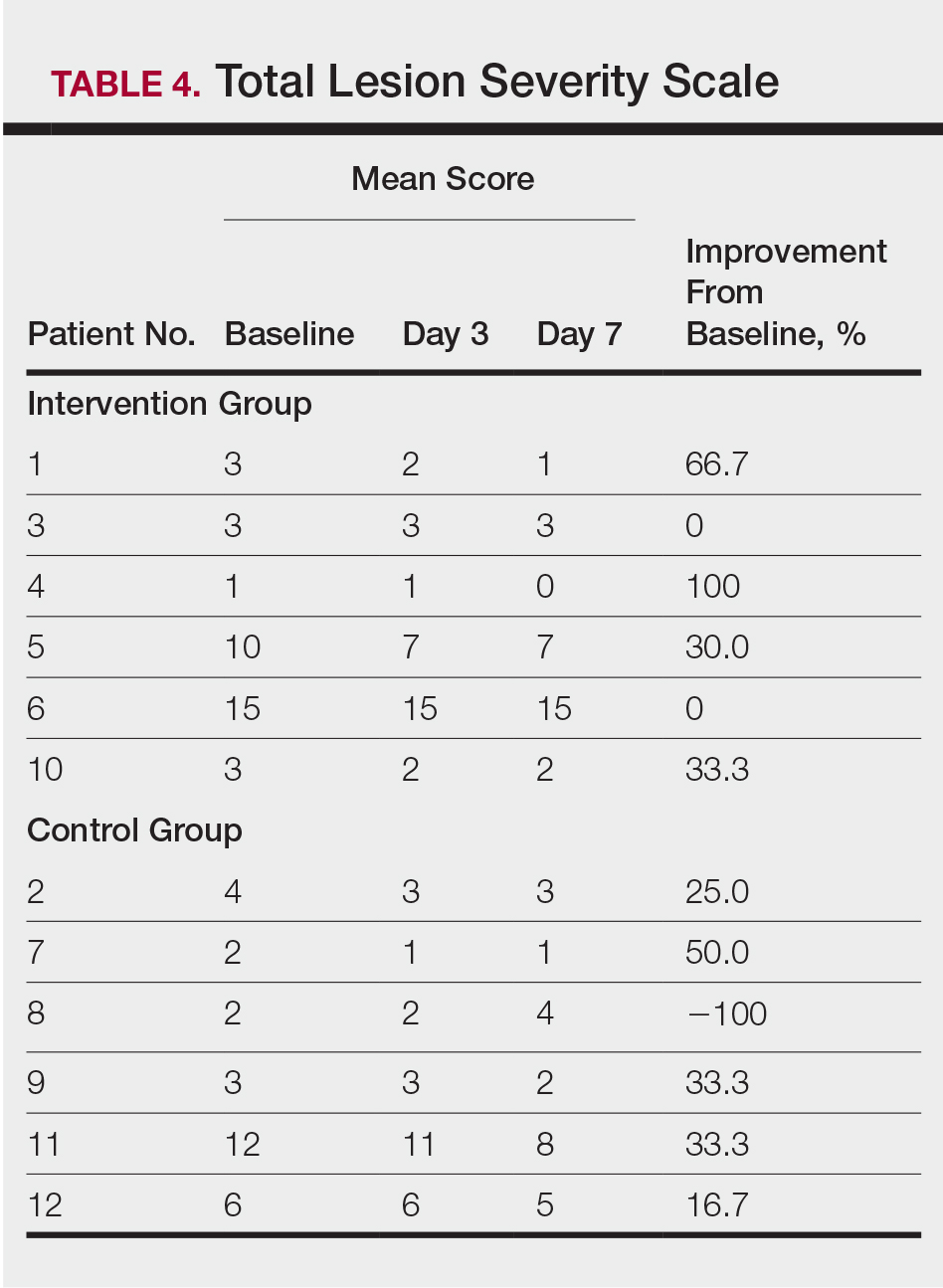

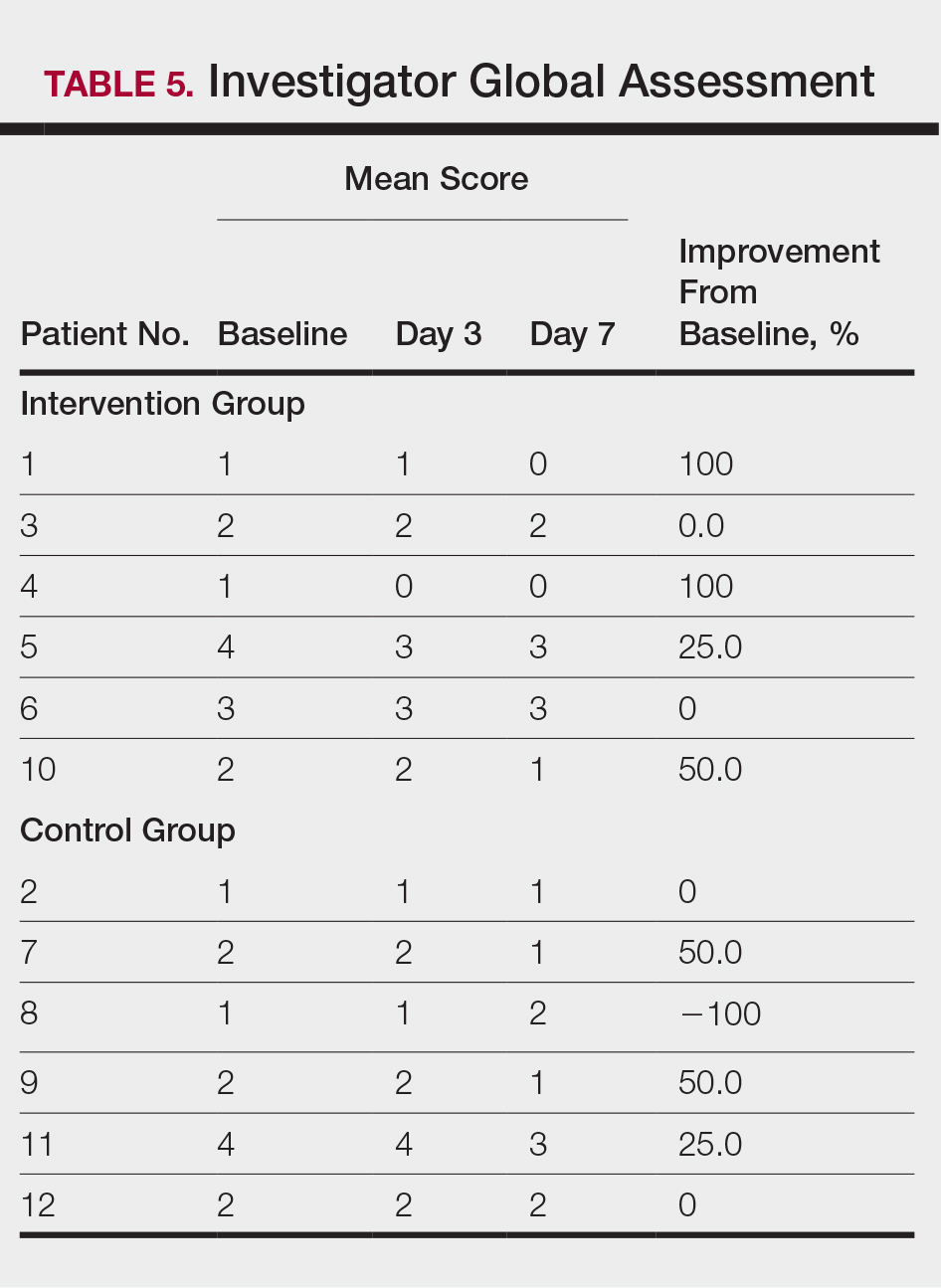

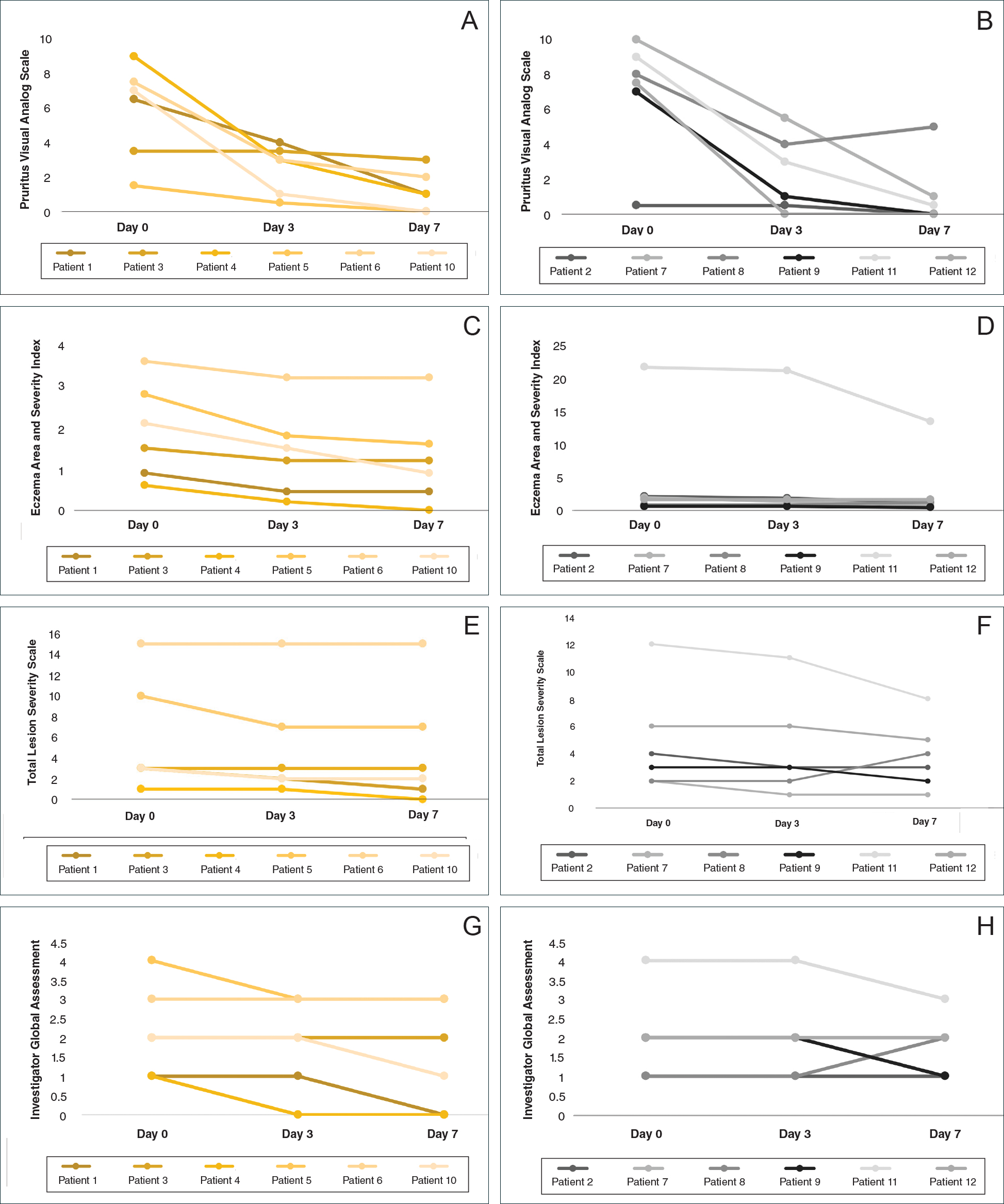

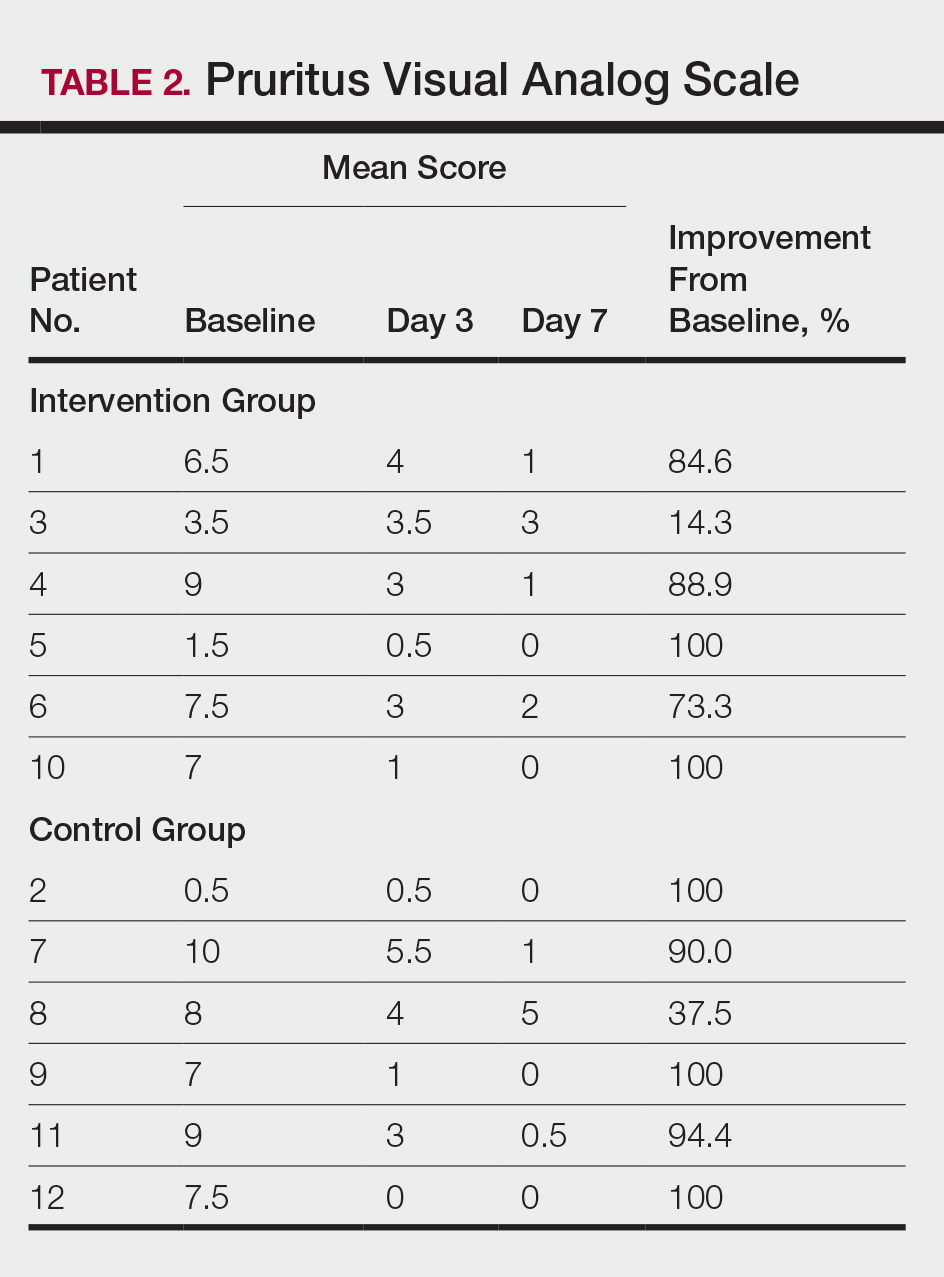

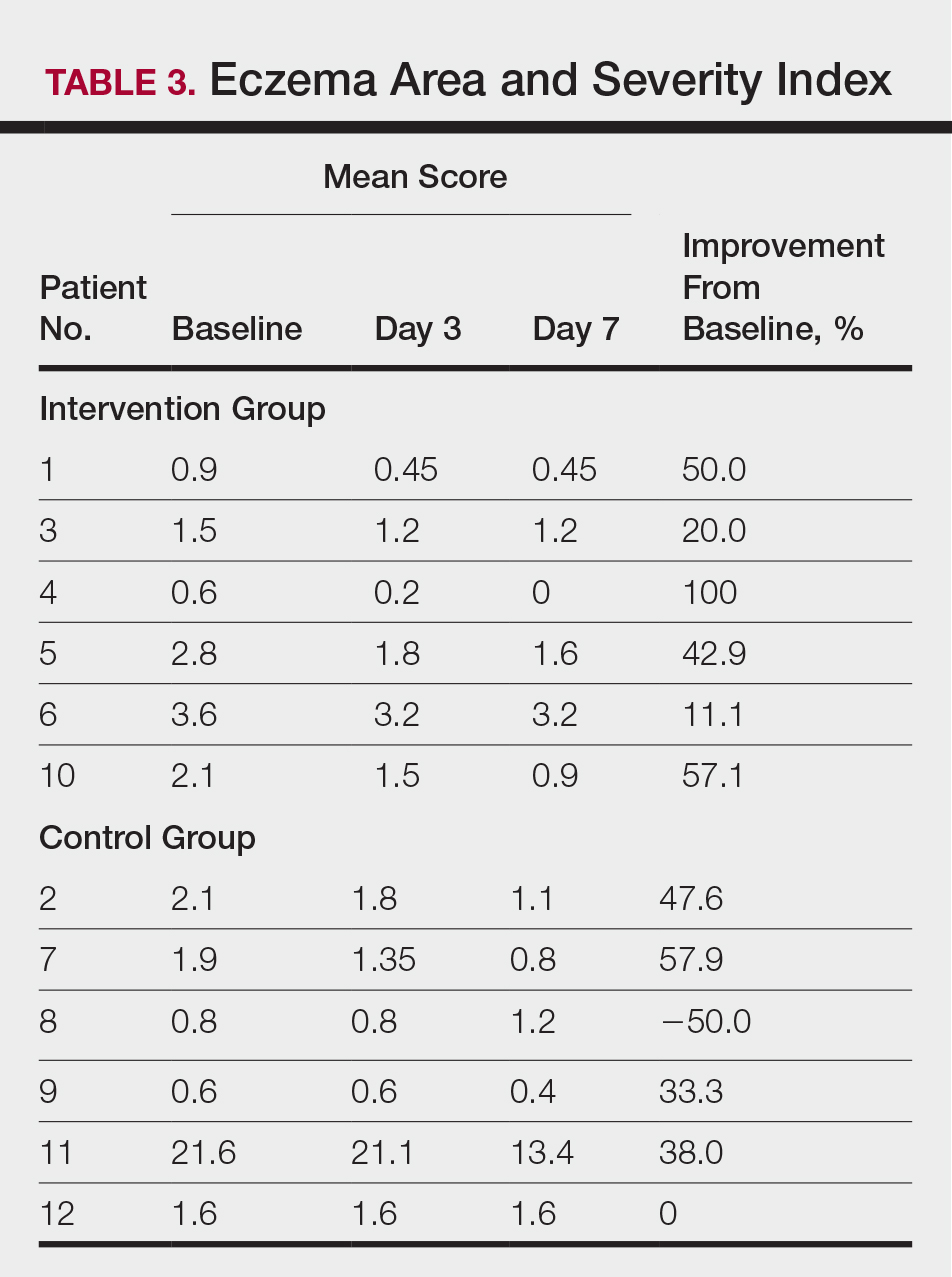

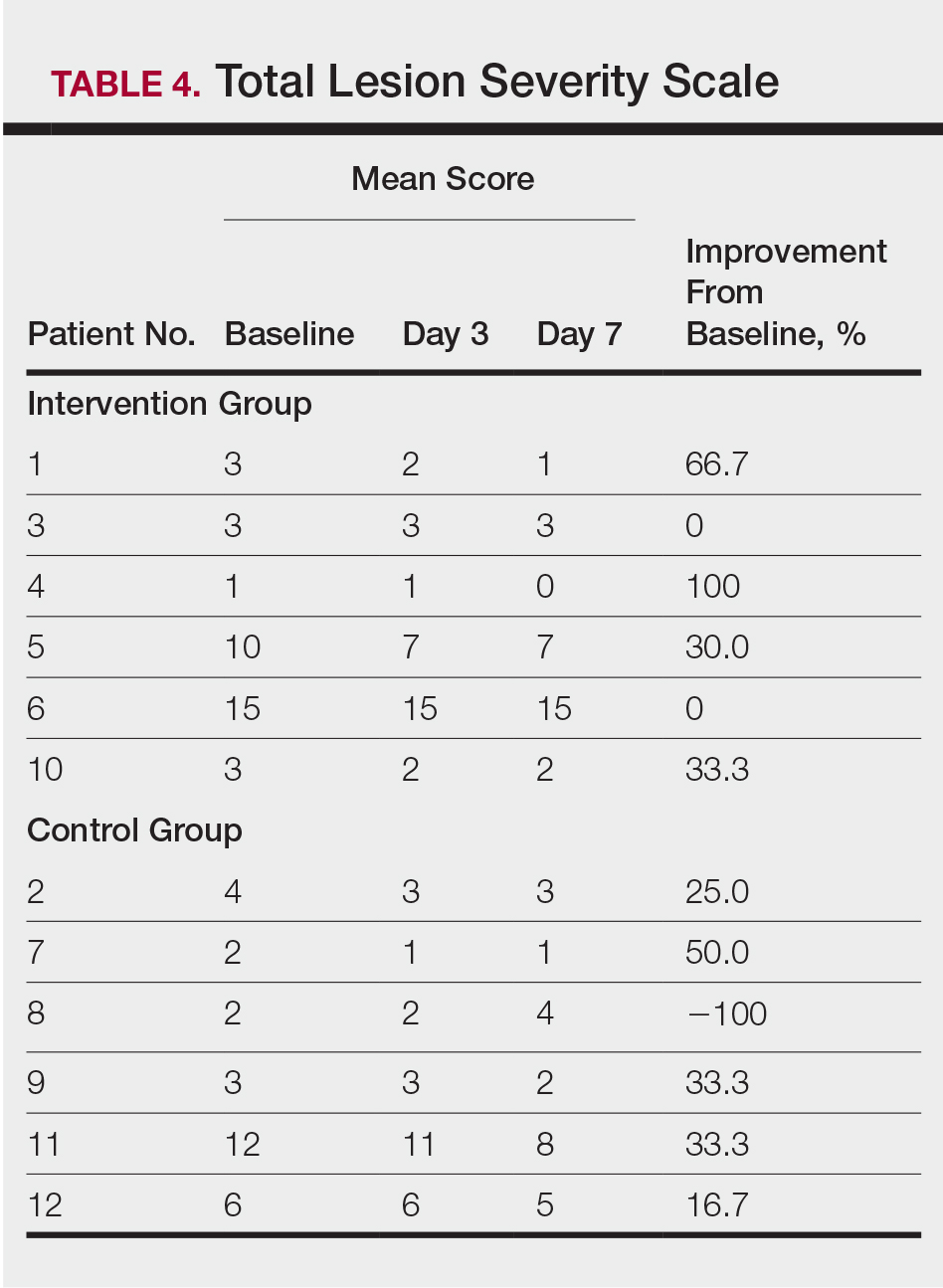

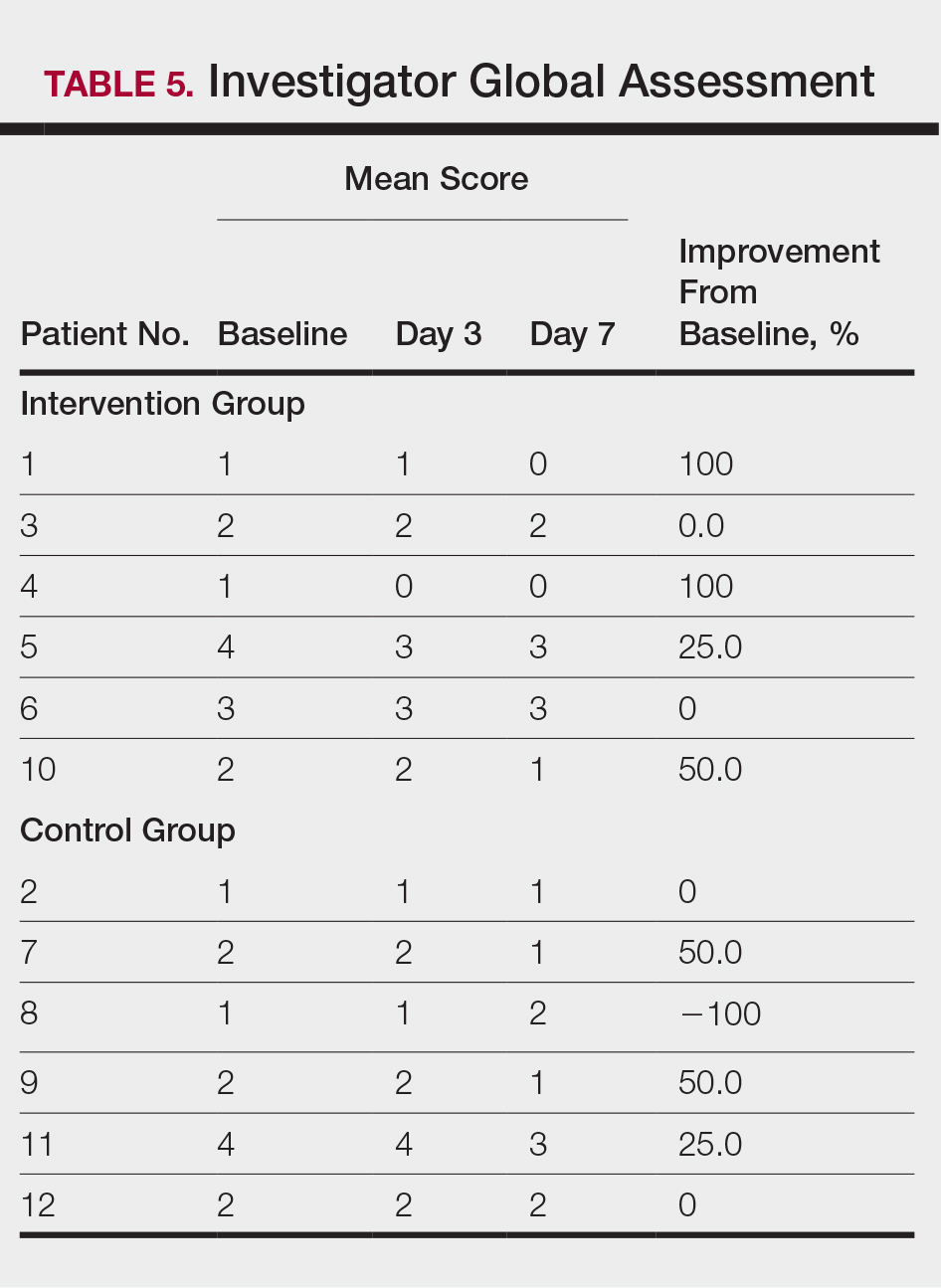

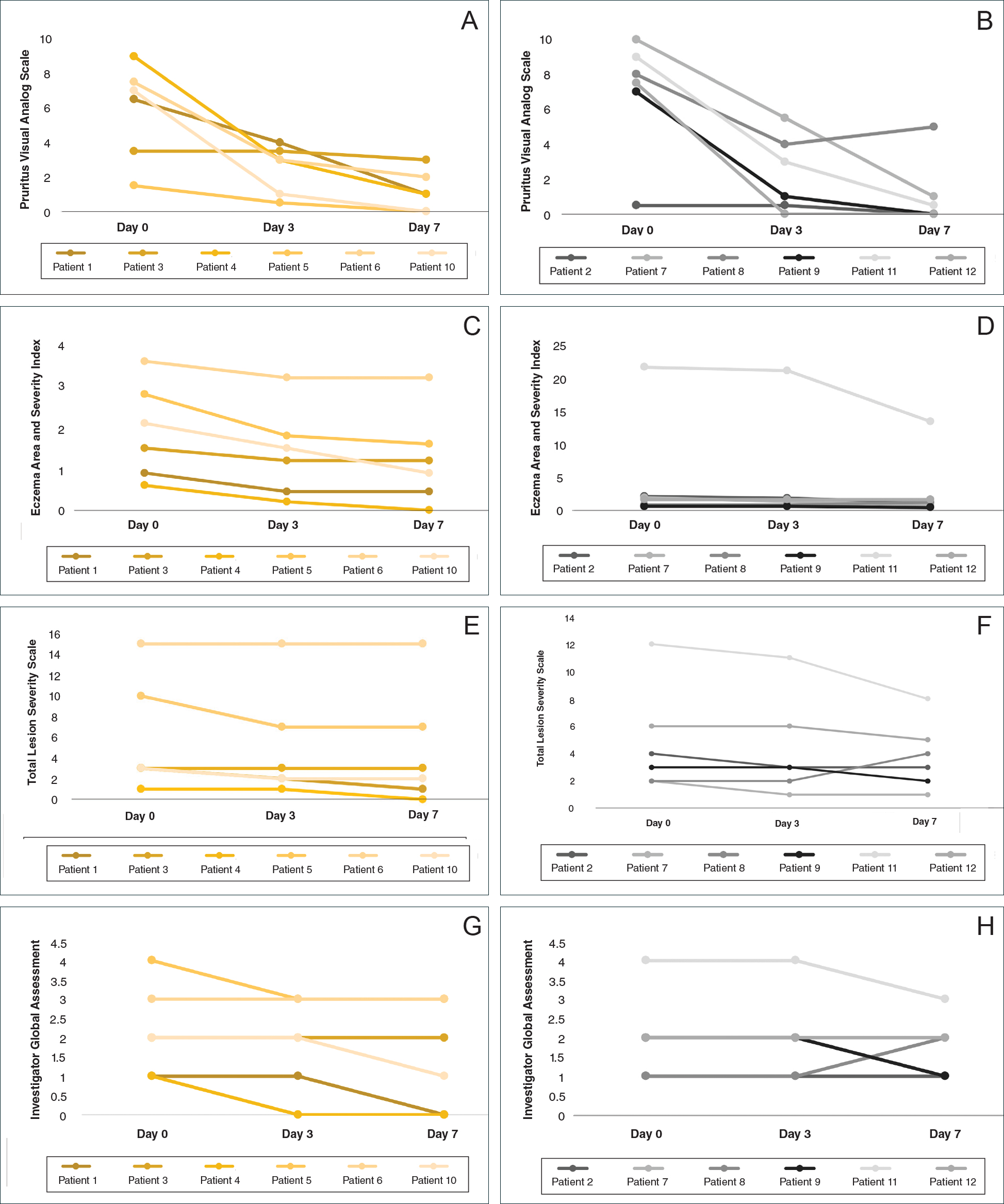

During visits, disease severity was scored using the visual analog scale for pruritus, psoriasis area and severity index (PASI), total lesion severity score (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

The study was designed to assess the number of topical treatment–resistant patients who would improve with topical treatment but was not designed or powered to test if the telephone call reminders increased adherence.

Results

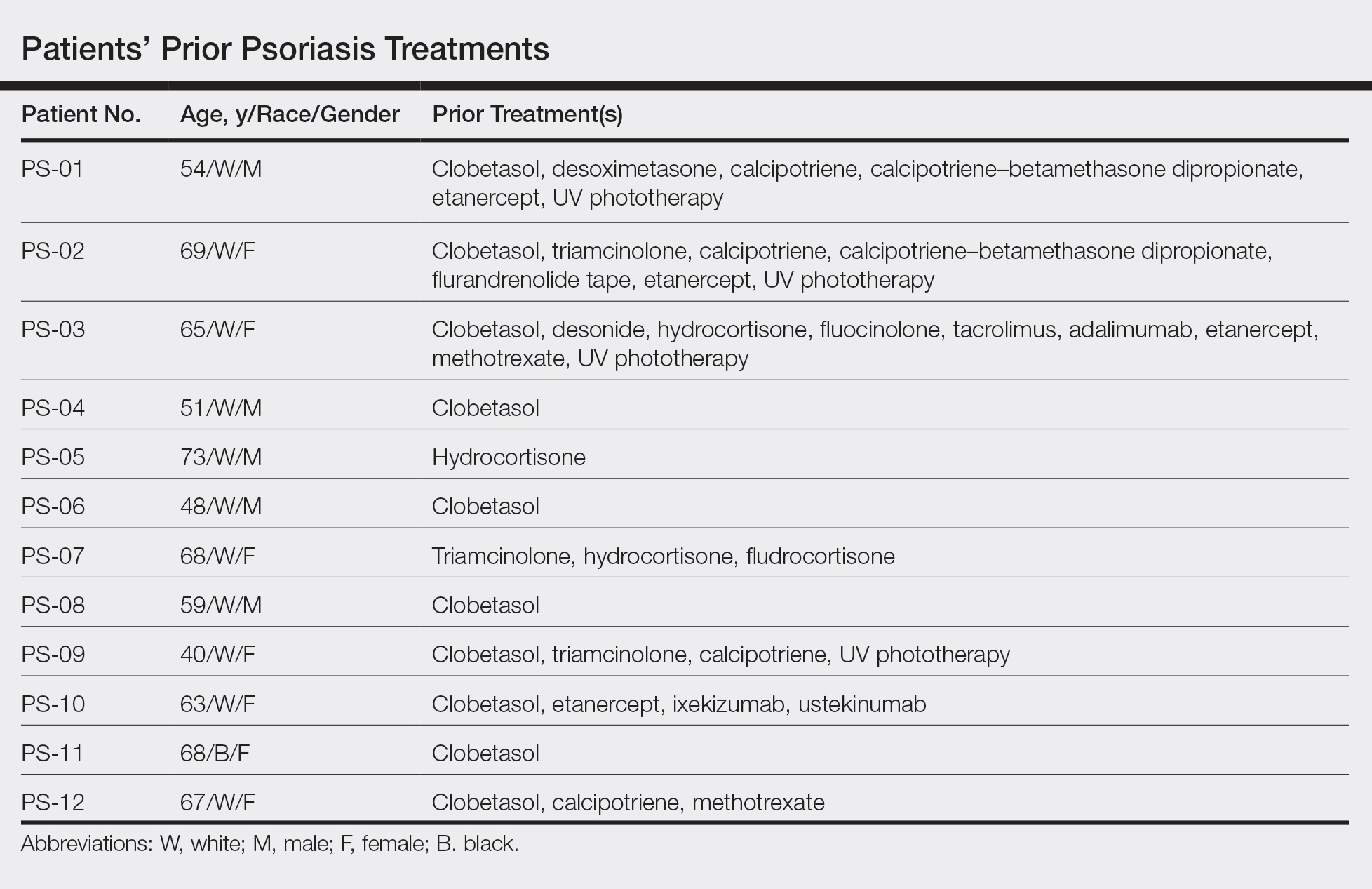

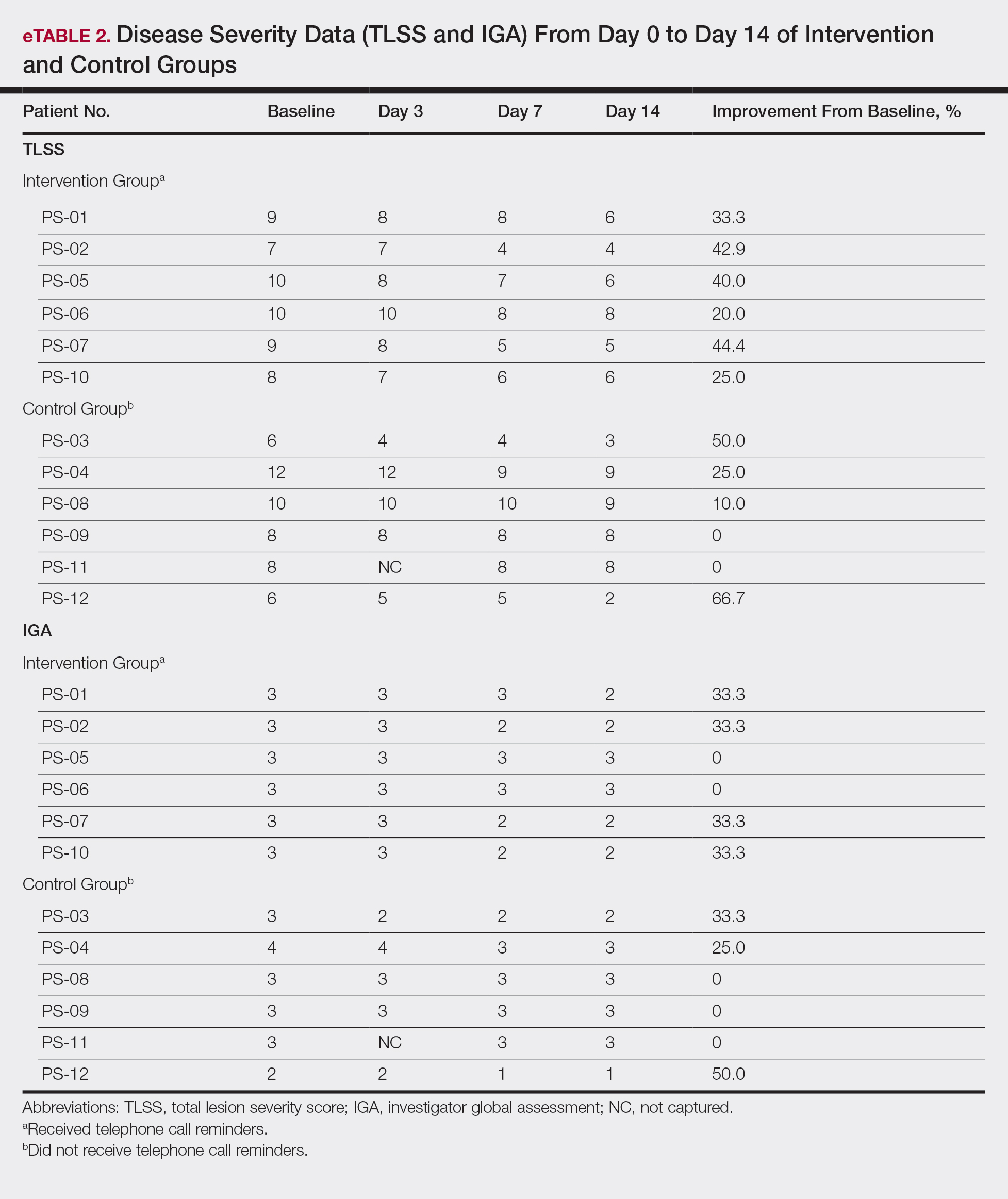

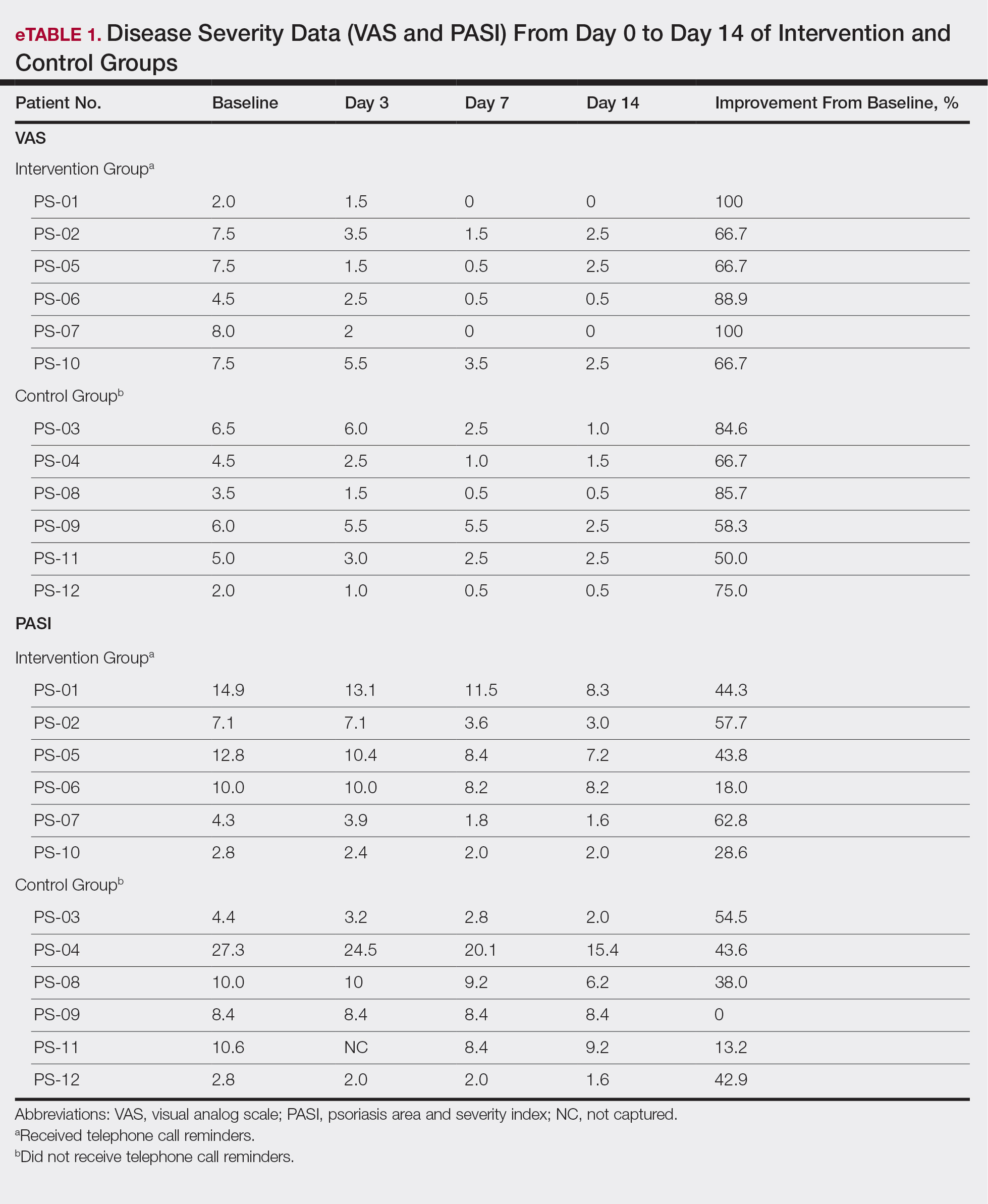

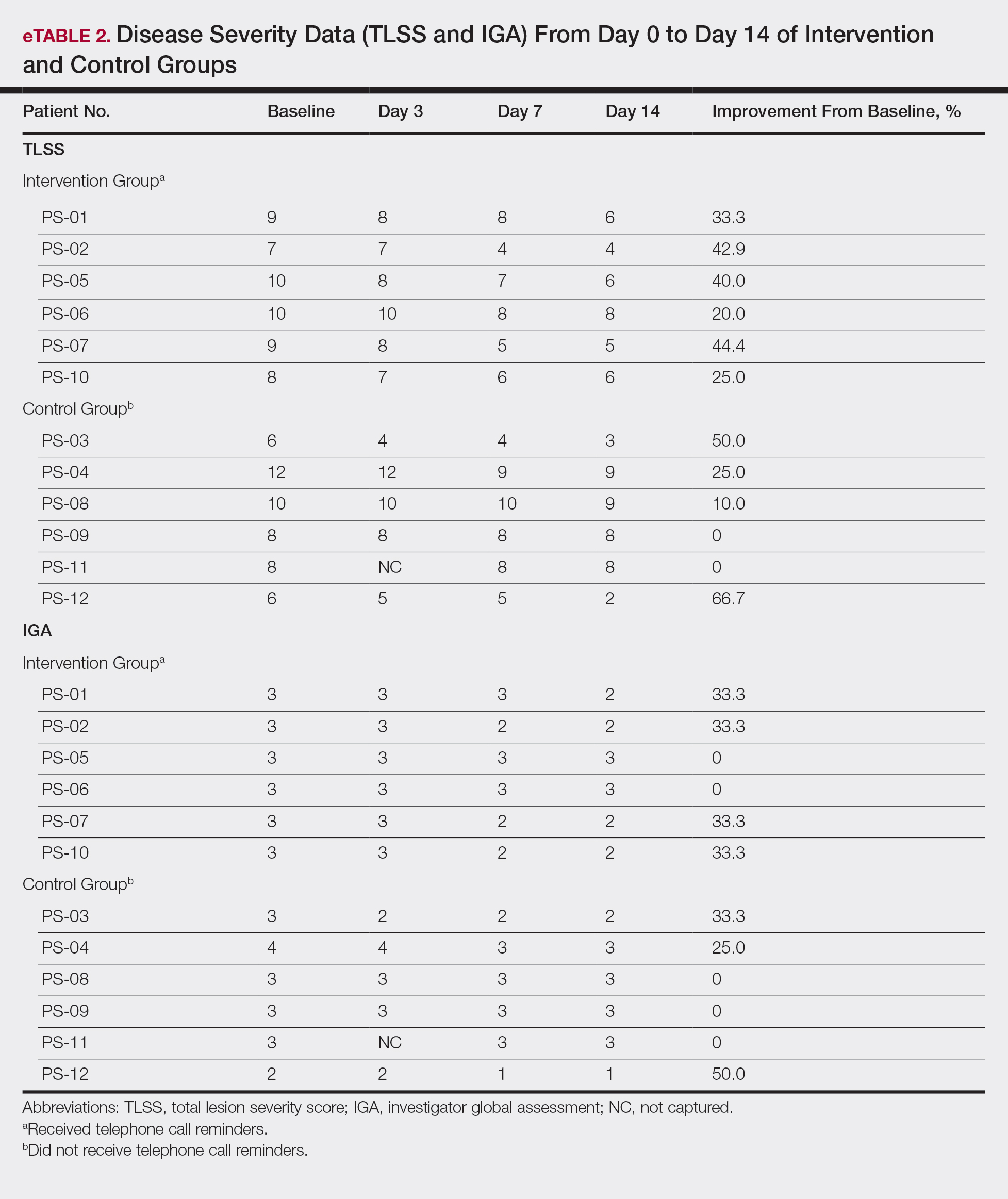

All patients completed the study; 10 of 12 patients (83.3%) had previously used topical clobetasol and it failed (Table). At the 2-week end-of-study visit, most patients improved on all measures. Patients who received telephone call reminders improved more than patients who did not. All 12 patients (100%) reported relief of itching; 11 of 12 (91.7%) had an improved PASI; 10 of 12 (83.3%) had an improved TLSS; and 7 of 12 (58.3%) had an improved IGA (eTables 1 and 2).

The percentage reduction in pruritus ranged from 66.7% to 100% and 50.0% to 85.7% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in PASI ranged from 18.0% to 62.8% and 0% to 54.5% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in TLSS and IGA was of lower magnitude but showed a similar pattern, with numerically greater improvement in the telephone call reminders group compared to the group that was not called (eTable 2). No patients showed a worse score for pruritus on the visual analog scale, PASI, TLSS, or IGA.

Discussion

Topical corticosteroids are highly effective for psoriasis in clinical trials, with clearance in 2 to 4 weeks in 60% to 80% of patients, a rapidity of response not matched by even the most potent biologic treatments.8,9 However, topical corticosteroids are not always effective in clinical practice. There may be primary inefficacy (they do not work at first) or secondary inefficacy (a previously effective treatment loses efficacy over time).10 Poor adherence can explain both phenomena. Primary adherence occurs when patients fill their prescription; secondary adherence occurs when patients follow the medication recommendations.11 Primary nonadherence is common in patients with psoriasis; in one study, 50% of psoriasis prescriptions were not filled.12 Secondary adherence also is poor and declines over time; electronic monitoring revealed adherence to topical treatments in psoriasis patients decreased from 85% initially to 51% at the end of 8 weeks.7 Given the high efficacy of topical corticosteroids in clinical trials and the poor adherence to topical treatment in patients with psoriasis, we anticipated that psoriasis that is resistant to topical corticosteroids would improve rapidly under conditions designed to promote adherence.

As expected, disease improved in almost every patient in this small cohort when they were given a potent topical corticosteroid, even though they previously reported that their psoriasis was resistant to potent topical corticosteroids. Although this study enrolled only a small cohort, it appears that the majority of patients with limited psoriasis that was reported to be resistant to topical treatment can see a response to topical treatment under conditions designed to encourage good adherence.

We believe that the good outcomes seen in our study were a result of good adherence. Although the desoximetasone spray 0.25% used in this study is a superpotent topical corticosteroid,8 the response to treatment was unlikely due to changing corticosteroid potency because 10 of 12 patients had tried another superpotent topical corticosteroid (clobetasol) and it failed. We chose a spray product for this study rather than an ointment to promote adherence; however, this choice limited the ability to assess adherence directly, as adherence-monitoring devices for spray delivery systems are not readily available.

Our study was limited by the small sample size and brief duration of treatment. However, the effect size is so large (ie, the topical treatment was so effective) that only a small sample size and brief treatment duration were needed to show that a high percentage of patients with psoriasis that had previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids can in fact respond to this treatment.

We used telephone calls as reminders in 50% of patients to further encourage adherence. The study was not designed or powered to assess the effect of the telephone call reminders, but patients receiving those calls appeared to have slightly greater reduction in disease severity. Nonetheless, twice-daily telephone call reminders are unlikely to be a wanted or practical intervention; other approaches to encourage adherence are needed.

Frequent follow-up visits were incorporated in our study design to maximize adherence. Although it might not be feasible for clinical practices to schedule follow-up visits as often as in our study, other approaches such as virtual visits and electronic interaction might provide a practical alternative. Multifaceted approaches to increasing adherence include encouraging patients to participate in the treatment plan, prescribing therapy consistent with a patient’s preferred vehicle, and extensive patient education.13 If patients do not respond as expected, poor adherence can be considered. Other potential causes of poor outcomes include error in diagnosis; resistance to the prescribed treatment; concomitant infection; irritant exposure; and, in the case of biologics, antidrug antibody formation.14,15

- Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr, Cooper JZ. New topical treatments change the pattern of treatment of psoriasis: dermatologists remain the primary providers of this care. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:41-44.

- Menter A. Topical monotherapy with clobetasol propionate spray 0.05% in the COBRA trial. Cutis. 2007;80(suppl 5):12-19.

- Saleem MD, Negus D, Feldman SR. Topical 0.25% desoximetasone spray efficacy for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: a randomized clinical trial. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018;29:32-35.

- Mraz S, Leonardi C, Colón LE, et al. Different treatment outcomes with different formulations of clobetasol propionate 0.05% for the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:354-359.

- Chiricozzi A, Pimpinelli N, Ricceri F, et al. Treatment of psoriasis with topical agents: recommendations from a Tuscany Consensus. Dermatol Ther. 2017;30:e12549.

- Carroll CL, Feldman SR, Camacho FT, et al. Adherence to topical therapy decreases during the course of an 8-week psoriasis clinical trial: commonly used methods of measuring adherence to topical therapy overestimate actual use. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:212-216.

- Alinia H, Moradi Tuchayi S, Smith JA, et al. Long-term adherence to topical psoriasis treatment can be abysmal: a 1-year randomized intervention study using objective electronic adherence monitoring. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:759-764.

- Keegan BR. Desoximetasone 0.25% spray for the relief of scaling in adults with plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:835-840.

- Beutner K, Chakrabarty A, Lemke S, et al. An intra-individual randomized safety and efficacy comparison of clobetasol propionate 0.05% spray and its vehicle in the treatment of plaque psoriasis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:357-360.

- Mehta AB, Nadkarni NJ, Patil SP, et al. Topical corticosteroids in dermatology. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:371-378.

- Blais L, Kettani FZ, Forget A, et al. Assessing adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in asthma patients using an integrated measure based on primary and secondary adherence. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;73:91-97.

- Storm A, Andersen SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Zschocke I, Mrowietz U, Karakasili E, et al. Non-adherence and measures to improve adherence in the topical treatment of psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(Suppl 2):4-9.

- Mooney E, Rademaker M, Dailey R, et al. Adverse effects of topical corticosteroids in paediatric eczema: Australasian consensus statement. Australas J Dermatol. 2015;56:241-251.

- Varada S, Tintle SJ, Gottlieb AB. Apremilast for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2014;7:239-250.

High-potency topical corticosteroids are first-line treatments for psoriasis, but many patients report that they are ineffective or lose effectiveness over time.1-5 The mechanism underlying the lack or loss of activity is not well characterized but may be due to poor adherence to treatment. Adherence to topical treatment is poor in the short run and even worse in the long run.6,7 We evaluated 12 patients with psoriasis resistant to topical corticosteroids to determine if they would respond to topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote adherence to treatment.

Methods

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study recruited 12 patients with plaque psoriasis that previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids and other therapies (Table). We stratified disease by body surface area: mild (<3%), moderate (3%–10%), and severe (>10%). Inclusion criteria included adult patients with plaque psoriasis amenable to topical corticosteroid therapy, ability to comply with requirements of the study, and a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment (Figure). Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, breastfeeding, had conditions that would affect adherence or potentially bias results (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), had a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and had a history of drug hypersensitivity.

All patients received desoximetasone spray 0.25% twice daily for 14 days. At the baseline visit, 6 patients were randomly selected to also receive a twice-daily reminder telephone call. Study visits occurred frequently—at baseline and on days 3, 7, and 14—to further assure good adherence to the treatment regimen.

During visits, disease severity was scored using the visual analog scale for pruritus, psoriasis area and severity index (PASI), total lesion severity score (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

The study was designed to assess the number of topical treatment–resistant patients who would improve with topical treatment but was not designed or powered to test if the telephone call reminders increased adherence.

Results

All patients completed the study; 10 of 12 patients (83.3%) had previously used topical clobetasol and it failed (Table). At the 2-week end-of-study visit, most patients improved on all measures. Patients who received telephone call reminders improved more than patients who did not. All 12 patients (100%) reported relief of itching; 11 of 12 (91.7%) had an improved PASI; 10 of 12 (83.3%) had an improved TLSS; and 7 of 12 (58.3%) had an improved IGA (eTables 1 and 2).

The percentage reduction in pruritus ranged from 66.7% to 100% and 50.0% to 85.7% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in PASI ranged from 18.0% to 62.8% and 0% to 54.5% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in TLSS and IGA was of lower magnitude but showed a similar pattern, with numerically greater improvement in the telephone call reminders group compared to the group that was not called (eTable 2). No patients showed a worse score for pruritus on the visual analog scale, PASI, TLSS, or IGA.

Discussion

Topical corticosteroids are highly effective for psoriasis in clinical trials, with clearance in 2 to 4 weeks in 60% to 80% of patients, a rapidity of response not matched by even the most potent biologic treatments.8,9 However, topical corticosteroids are not always effective in clinical practice. There may be primary inefficacy (they do not work at first) or secondary inefficacy (a previously effective treatment loses efficacy over time).10 Poor adherence can explain both phenomena. Primary adherence occurs when patients fill their prescription; secondary adherence occurs when patients follow the medication recommendations.11 Primary nonadherence is common in patients with psoriasis; in one study, 50% of psoriasis prescriptions were not filled.12 Secondary adherence also is poor and declines over time; electronic monitoring revealed adherence to topical treatments in psoriasis patients decreased from 85% initially to 51% at the end of 8 weeks.7 Given the high efficacy of topical corticosteroids in clinical trials and the poor adherence to topical treatment in patients with psoriasis, we anticipated that psoriasis that is resistant to topical corticosteroids would improve rapidly under conditions designed to promote adherence.

As expected, disease improved in almost every patient in this small cohort when they were given a potent topical corticosteroid, even though they previously reported that their psoriasis was resistant to potent topical corticosteroids. Although this study enrolled only a small cohort, it appears that the majority of patients with limited psoriasis that was reported to be resistant to topical treatment can see a response to topical treatment under conditions designed to encourage good adherence.

We believe that the good outcomes seen in our study were a result of good adherence. Although the desoximetasone spray 0.25% used in this study is a superpotent topical corticosteroid,8 the response to treatment was unlikely due to changing corticosteroid potency because 10 of 12 patients had tried another superpotent topical corticosteroid (clobetasol) and it failed. We chose a spray product for this study rather than an ointment to promote adherence; however, this choice limited the ability to assess adherence directly, as adherence-monitoring devices for spray delivery systems are not readily available.

Our study was limited by the small sample size and brief duration of treatment. However, the effect size is so large (ie, the topical treatment was so effective) that only a small sample size and brief treatment duration were needed to show that a high percentage of patients with psoriasis that had previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids can in fact respond to this treatment.

We used telephone calls as reminders in 50% of patients to further encourage adherence. The study was not designed or powered to assess the effect of the telephone call reminders, but patients receiving those calls appeared to have slightly greater reduction in disease severity. Nonetheless, twice-daily telephone call reminders are unlikely to be a wanted or practical intervention; other approaches to encourage adherence are needed.

Frequent follow-up visits were incorporated in our study design to maximize adherence. Although it might not be feasible for clinical practices to schedule follow-up visits as often as in our study, other approaches such as virtual visits and electronic interaction might provide a practical alternative. Multifaceted approaches to increasing adherence include encouraging patients to participate in the treatment plan, prescribing therapy consistent with a patient’s preferred vehicle, and extensive patient education.13 If patients do not respond as expected, poor adherence can be considered. Other potential causes of poor outcomes include error in diagnosis; resistance to the prescribed treatment; concomitant infection; irritant exposure; and, in the case of biologics, antidrug antibody formation.14,15

High-potency topical corticosteroids are first-line treatments for psoriasis, but many patients report that they are ineffective or lose effectiveness over time.1-5 The mechanism underlying the lack or loss of activity is not well characterized but may be due to poor adherence to treatment. Adherence to topical treatment is poor in the short run and even worse in the long run.6,7 We evaluated 12 patients with psoriasis resistant to topical corticosteroids to determine if they would respond to topical corticosteroids under conditions designed to promote adherence to treatment.

Methods

This open-label, randomized, single-center clinical study recruited 12 patients with plaque psoriasis that previously failed treatment with topical corticosteroids and other therapies (Table). We stratified disease by body surface area: mild (<3%), moderate (3%–10%), and severe (>10%). Inclusion criteria included adult patients with plaque psoriasis amenable to topical corticosteroid therapy, ability to comply with requirements of the study, and a history of failed topical corticosteroid treatment (Figure). Patients were excluded if they were pregnant, breastfeeding, had conditions that would affect adherence or potentially bias results (eg, dementia, Alzheimer disease), had a history of allergy or sensitivity to corticosteroids, and had a history of drug hypersensitivity.

All patients received desoximetasone spray 0.25% twice daily for 14 days. At the baseline visit, 6 patients were randomly selected to also receive a twice-daily reminder telephone call. Study visits occurred frequently—at baseline and on days 3, 7, and 14—to further assure good adherence to the treatment regimen.

During visits, disease severity was scored using the visual analog scale for pruritus, psoriasis area and severity index (PASI), total lesion severity score (TLSS), and investigator global assessment (IGA). Descriptive statistics were used to report the outcomes for each patient.

The study was designed to assess the number of topical treatment–resistant patients who would improve with topical treatment but was not designed or powered to test if the telephone call reminders increased adherence.

Results

All patients completed the study; 10 of 12 patients (83.3%) had previously used topical clobetasol and it failed (Table). At the 2-week end-of-study visit, most patients improved on all measures. Patients who received telephone call reminders improved more than patients who did not. All 12 patients (100%) reported relief of itching; 11 of 12 (91.7%) had an improved PASI; 10 of 12 (83.3%) had an improved TLSS; and 7 of 12 (58.3%) had an improved IGA (eTables 1 and 2).

The percentage reduction in pruritus ranged from 66.7% to 100% and 50.0% to 85.7% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in PASI ranged from 18.0% to 62.8% and 0% to 54.5% with and without telephone call reminders, respectively. Improvement in TLSS and IGA was of lower magnitude but showed a similar pattern, with numerically greater improvement in the telephone call reminders group compared to the group that was not called (eTable 2). No patients showed a worse score for pruritus on the visual analog scale, PASI, TLSS, or IGA.

Discussion