User login

A Validated Delirium Prediction Rule

Delirium is characterized by fluctuating disturbances in cognition and consciousness and is a common complication of hospitalization in medical and surgical patients. Studies estimate the prevalence of delirium in hospitalized patients[1] to be 14% to 56%, and up to 70% in critically ill elderly patients.[2] Estimates of total healthcare costs associated with delirium range from $38 to $152 billion per year in the United States.[3] Delirious patients are more likely to be discharged to a nursing home and have increased hospital mortality and longer lengths of stay.[4, 5, 6] Recent data suggest long‐term effects of delirium including cognitive impairments up to 1 year following the illness[7] and an increased likelihood of developing[8] or worsening dementia.[9]

It is estimated that one‐third of hospital‐acquired delirium cases could be prevented with appropriate interventions.[10] A prediction rule that easily and accurately identifies high‐risk patients upon admission could therefore have a substantial clinical impact. In addition, a prediction rule could be used to identify patients in whom new targeted interventions for delirium prevention could be investigated. A number of risk factors for delirium have been identified, including older age, preexisting cognitive dysfunction, vision and hearing impairment, severe illness, dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, overmedication, and alcohol abuse.[11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] Existing prediction rules using various combinations of these measures have been limited by their complexity,[17] do not predict incident delirium,[18, 19] or are restricted to surgical[20, 21, 22] or intensive care[23] patients and therefore are not broadly applicable to the general medical population, which is particularly susceptible to developing delirium.

We conducted this study to develop a simple, efficient, and accurate prediction rule for hospital‐acquired delirium in adult medical inpatients assessed at the time of admission. Our a priori hypothesis was that a delirium prediction rule would consist of a combination of known risk factors and most likely incorporate old age, illness severity, and preexisting cognitive dysfunction.

METHODS

Design and Setting

This was a prospective cohort study with a derivation phase from May 2010 to November 2010 at 2 hospitals at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) (Moffitt‐Long and Mount Zion Hospitals) and a validation phase from October 2011 to March 2012 at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center (SFVAMC).

Participants and Measurements

Subject identification, recruitment, and inclusion and exclusion criteria were identical for the derivation and validation cohorts. Subjects were identified by reviewing daily admission logs. All non‐intensive care unit patients aged 50 years or older admitted through the emergency department to the medicine, cardiology, or neurology services were screened for eligibility through chart review or in person within 24 hours of admission by a trained research assistant. One research assistant, a college graduate, conducted all screening for the derivation cohort, and 2 research assistants, 1 a fourth‐year medical student and the other a third‐year psychology graduate student, conducted screening for the validation cohort. In‐person screening included an assessment for delirium using the long version of the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).[24] To minimize the possibility of enrolling delirious subjects, research assistants were instructed to notify the study supervisor (V.C.D.), a board‐certified neurologist, to discuss every case in which any yes checkbox was marked on the CAM score sheet. Subjects delirious upon initial evaluation, admitted for alcohol withdrawal, admitted for comfort care, who were aphasic or who could not speak English were excluded. For all patients, or if they were unable to provide consent, their surrogates provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards at UCSF and SFVAMC.

In the derivation cohort, 1241 patients were screened, and 439 were eligible for enrollment. Of these, 180 declined, 50 were discharged prior to the first follow‐up visit, and 209 were included. In the validation cohort, 420 patients were screened, and 368 were eligible for enrollment. Of these, 144 declined, 59 were discharged prior to the first follow‐up visit, and 165 were included.

Baseline data regarding known delirium risk factors[11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] were collected from subjects in the derivation cohort. Cognitive performance was assessed with the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE),[25] forward digit span,[26] and clock draw.[27] Permission for administration of the MMSE was granted by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., and each administration was paid for. A structured interview was conducted with validated questions regarding visual and hearing impairment, pain, mobility, place of residence, and alcohol, tobacco, and drug use.[28, 29, 30, 31] A whisper test for hearing loss was performed.[32] Subjects' charts were reviewed for demographic, clinical, and laboratory data. Illness severity was assessed by asking each subject's nurse to rate their patient on a scale from not ill to mildly ill, moderately ill, severely ill, or moribund.[33] Each nurse was shown these 5 choices, but more specific definitions of what each level of illness severity meant were not provided. We chose this method to assess illness severity because this rating scale was incorporated into a previous validated and widely cited delirium prediction rule.[17] This illness severity scale has been validated as a predictor of outcomes and correlates with other measures of illness severity and comorbidity when graded by physicians.[33, 34] Nurse and physician ratings of illness severity have been shown to be comparable,[35] and therefore if the scale were incorporated into the prediction rule it would allow nurses to perform it independently. In the validation cohort, only data required to complete the baseline CAM and apply the prediction rule were collected.

Assessment of Outcomes

All subjects were assessed for delirium daily for 6 days after enrollment or until discharge, whichever came first. Follow‐up was limited to 6 days, based on the assumption that delirium occurring beyond 1 week is more likely due to events during the hospitalization as opposed to factors measurable at admission. Delirium was assessed using the short CAM, an internationally recognized and validated tool.[24] To complete the CAM during follow‐up visits, subjects and their nurses were interviewed using a written script, and an MMSE and forward digit span were performed.

Daily follow‐up assessments were performed by research assistants who were not blinded to the initial assessment but who, in the validation phase, were blinded to the prediction rule score. Some weekend follow‐ups were performed by postgraduate year 2, 3, or 4 neurology residents, or internal medicine faculty experienced in the assessment of delirium and blinded to both the initial assessment and prediction rule score. Neurology residents and internists read the CAM training manual and were educated in the administration and scoring of the CAM by 1 of the senior investigators (V.C.D.) prior to their first shift; these nonstudy personnel covered 17 of 189 days of follow‐up in the derivation cohort and 21 of 169 days of follow‐up in the validation cohort. To maximize sensitivity of delirium detection, for any change in cognition, MMSE score, or forward digit span compared to baseline, a board‐certified neurologist blinded to the initial assessment was notified to discuss the case and validate the diagnosis of delirium in person (derivation cohort) or over the phone (validation cohort). All research assistants were trained by a board‐certified neurologist (V.C.D.) in the administration and interpretation of the CAM using published methods prior to enrollment of any subjects.[36] Training included the performance of independent long‐version CAMs by the trainer and the trainee on a series of delirious and nondelirious patients until there was consistent agreement for each item on the CAM in 5 consecutive patients. In addition, a board‐certified neurologist supervised the first 5 administrations of the CAM performed by each research assistant.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size for the derivation cohort was based on the predicted ability to detect a difference in rates of delirium among those with and without cognitive impairment, the strongest risk factor for delirium. Using a [2] test with an of 0.05 and of 0.80, we estimated we would need to enroll 260 subjects, assuming a prevalence of cognitive dysfunction in our cohort of 10% and an estimated rate of delirium of 24% and 6% among those with and without cognitive dysfunction respectively.[14, 16, 17, 20] We were unable to reach enrollment targets because of a short funding period and slower than expected recruitment.

To construct the prediction rule in the derivation cohort, all variables were dichotomized. Age was dichotomized at 80 years because old age is a known risk factor for delirium, and only 1 of 46 subjects between the ages of 70 and 80 years became delirious in the derivation cohort. Components of the MMSE were dichotomized as correct/emncorrect, with a correct response requiring perfect performance based on expert consensus. For 3 subjects who would not attempt to spell world backward (2 in the derivation and 1 in the validation cohort), their score on serial 7s was used instead. The total MMSE score was not used because our objective was to develop a prediction rule using elements that could be assessed quickly in the fast‐paced environment of the hospital. Illness severity was dichotomized at moderate or worse/mild or better because there were only 15 subjects in the severe illness category, and the majority of delirium (22 outcomes) occurred in the moderate illness category. High blood urea nitrogen:creatinine ratio was defined as >18.[37]

The association between predictor variables and occurrence of delirium was analyzed using univariate logistic regression. A forward stepwise logistic regression was then performed using the variables associated with the outcome at a significance level of P<0.05 in univariate analysis. Variables were eligible for addition to the multivariable model if they were associated with the outcome at a significance level of <0.05. The 4 independent predictors thus identified were combined into a prediction rule by assigning each predictor 1 point if present. The performance of the prediction rule was assessed by using Cuzick's nonparametric test for a trend across groups ordered by score.[38]

The prediction rule was tested in the validation cohort using the nonparametric test for trend. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were compared between the derivation and validation cohorts. All statistical analysis was performed using Stata software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The derivation cohort consisted of elderly patients (mean age, 68.0811.96 years; interquartile range, 5096 years), and included more males than females (54.1% vs 45.9%). Subjects were predominantly white (73.7%) and lived at home (90%) (Table 1). The mean admission MMSE score was 27.0 (standard deviation [SD], 3.4; range, 730). Median follow‐up was 2 days (interquartile range, 13). Delirium developed in 12% (n=25) of the cohort.

| Derivation Cohort, N=209 | Validation Cohort, N=165 | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Gender, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 113 (54) | 157 (95) |

| Female | 96 (46) | 8 (4.8) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||

| White | 154 (74) | 125 (76) |

| African American | 34 (16) | 25 (15) |

| Asian | 21 (10.0) | 13 (7.9) |

| Native American | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Illness severity, No. (%) | ||

| Not ill | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Mildly ill | 49 (23) | 62 (38) |

| Moderately ill | 129 (62) | 86 (52) |

| Severely ill | 15 (7.2) | 17 (10) |

| Moribund | 0 | 0 |

| Living situation, No. (%) | ||

| Home | 188 (90) | 147 (89) |

| Assisted living | 11 (5.3) | 6 (3.6) |

| Hotel | 4 (1.9) | 5 (3.0) |

| SNF | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.8) |

| Homeless | 4 (1.9) | 4 (2.4) |

| Developed delirium | 25 (12) | 14 (8.5) |

Univariate analysis of the derivation study identified 10 variables significantly associated (P<0.05) with delirium (Table 2). Predictors of delirium included abnormal scores on 4 subtests of the MMSE, low score on the Mini‐Cog, living in an assisted living or skilled nursing facility, moderate to severe illness, old age, a past history of dementia, and hearing loss as assessed by the whisper test. These predictors were then entered into a stepwise logistic regression analysis that identified 4 independent predictors of delirium (Table 3).

| Variable | No. (%) Without Delirium | No. (%) With Delirium | Odds Ratio | P Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Age 80 years | 30 (16) | 13 (52) | 5.6 | <0.001 | 2.313.4 |

| Male sex | 99 (54) | 14 (56) | 1.1 | 0.84 | 0.52.5 |

| White race | 135 (73) | 19 (76) | 1.2 | 0.78 | 0.433.1 |

| Score <5 on date questions of MMSE | 37 (20) | 12 (48) | 3.7 | 0.003 | 1.68.7 |

| Score <5 on place questions of MMSE | 50 (27) | 14 (56) | 3.4 | 0.005 | 1.58.0 |

| Score <3 on MMSE recall | 89 (48) | 18 (72) | 2.7 | 0.03 | 1.16.9 |

| Score <5 on MMSE W‐O‐R‐L‐D backward | 37 (20) | 13 (52) | 4.3 | 0.001 | 1.810.2 |

| Score 0 on MMSE pentagon copy, n=203 | 53 (30) | 12 (48) | 2.2 | 0.07 | 0.935.1 |

| Score 0 on clock draw, n=203 | 70 (39) | 15 (60) | 2.3 | 0.05 | 0.985.4 |

| MiniCog score 02, n=203[27] | 46 (26) | 12 (48) | 2.7 | 0.03 | 1.16.2 |

| Self‐rated vision fair, poor, or very poor | 55 (30) | 8 (32) | 1.1 | 0.83 | 0.452.7 |

| Endorses hearing loss | 89 (48) | 12 (48) | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.432.3 |

| Uses hearing aid | 19 (10) | 2 (8) | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.173.5 |

| Fails whisper test in either ear | 39 (21) | 10 (40) | 2.5 | 0.04 | 1.05.9 |

| Prior episode of delirium per patient or informant | 70 (38) | 13 (52) | 1.8 | 0.19 | 0.764.1 |

| Dementia in past medical history | 3 (2) | 3 (12) | 8.2 | 0.01 | 1.643.3 |

| Depression in past medical history | 16 (9) | 1 (4) | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.063.5 |

| Lives in assisted living or SNF | 8 (4) | 4 (16) | 4.2 | 0.03 | 1.215.1 |

| Endorses pain | 82 (45) | 7 (28) | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.191.2 |

| Less than independent for transfers | 11 (6) | 3 (12) | 2.1 | 0.27 | 0.568.3 |

| Less than independent for mobility on a level surface | 36 (20) | 7 (28) | 1.6 | 0.33 | 0.624.1 |

| Score of 24 on CAGE questionnaire[29] | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | No outcomes | ||

| Drinks any alcohol | 84 (46) | 10 (40) | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.341.9 |

| Current smoker | 20 (11) | 2 (8) | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.164.1 |

| Uses illicit drugs | 13 (7) | 2 (8) | 1.2 | 0.83 | 0.255.6 |

| Moderately or severely ill on nursing assessment, n=194 | 121 (71) | 23 (96) | 9.3 | 0.031 | 1.270.9 |

| Fever | 8 (4) | 0 (0) | No outcomes | ||

| Serum sodium <134mmol/L | 38 (21) | 3 (12) | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.151.8 |

| WBC count>10109/L, n=208 | 57 (31) | 6 (24) | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.261.8 |

| AST>41 U/L, n=131 | 27 (23) | 2 (15) | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.132.9 |

| BUN:Cr>18, n=208 | 66 (36) | 13 (52) | 1.9 | 0.13 | 0.834.5 |

| Infection as admission diagnosis | 28 (15) | 4 (16) | 1.1 | 0.92 | 0.343.3 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value | Points Toward AWOL Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 80 years | 5.7 | 2.115.6 | 0.001 | 1 |

| Unable to correctly spell world backward | 3.5 | 1.39.6 | 0.01 | 1 |

| Not oriented to city, state, county, hospital name, and floor | 2.9 | 1.17.9 | 0.03 | 1 |

| Nursing illness severity assessment of moderately ill, severely ill, or moribund (as opposed to not ill or mildly ill) | 10.5 | 1.386.9 | 0.03 | 1 |

These 4 independent predictors were assigned 1 point each if present to create a prediction rule with a range of possible scores from 0 to 4. There was a significant trend predicting higher rates of delirium with higher scores, with no subjects who scored 0 becoming delirious, compared to 40% of those subjects scoring 3 or 4 (P for trend<0.001) (Table 4).

| Derivation Cohorta | Validation Cohort | Combined Cohorts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWOL Score | Not Delirious | Delirious | Not Delirious | Delirious | Not Delirious | Delirious |

| ||||||

| 0 | 26 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (96%) | 1 (4%) | 49 (98%) | 1 (2%) |

| 1 | 86 (95%) | 5 (5%) | 57 (97%) | 2 (3%) | 136 (96%) | 5 (4%) |

| 2 | 41 (85%) | 7 (15%) | 44 (90%) | 5 (10%) | 92 (86%) | 15 (14%) |

| 3 | 17 (74%) | 6 (26%) | 22 (79%) | 6 (21%) | 40 (80%) | 10 (20%) |

| 4 | 0 (0%) | 6 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (36%) | 7 (64%) |

| Total | 170 | 24 | 151 | 14 | 321 | 38 |

| P<0.001 | P=0.025 | P<0.001 | ||||

The validation cohort consisted of adults with a mean age of 70.7210.6 years, (interquartile range, 5194 years), who were predominantly white (75.8%) and overwhelmingly male (95.2%) (Table 1). The mean admission MMSE score was 26.75 (SD, 2.8; range, 1730). Median follow‐up was 2 days (interquartile range, 15). Delirium developed in 8.5% (n=14) of the cohort. In the validation cohort, 4% of subjects with a score of 0 became delirious, whereas 19% of those scoring 3 or 4 became delirious (P for trend 0.025) (Table 4).

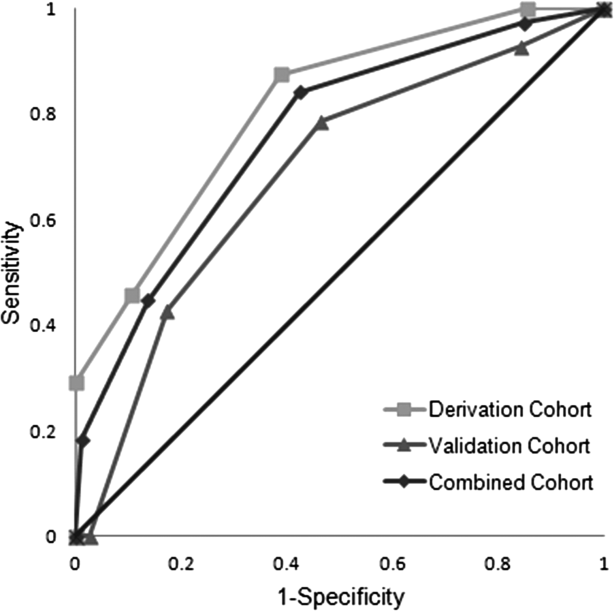

ROC curves were compared for the derivation and validation cohorts. The area under the ROC curve for the derivation cohort (0.81, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.720.90) was slightly better than that in the validation cohort (0.69, 95% CI: 0.540.83), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.14) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

We derived and validated a prediction rule to assess the risk of developing delirium in hospitalized adult medical patients. Four variables easily assessed on admission in a screen lasting less than 2 minutes were independently associated with the development of delirium. The prediction rule can be remembered with the following mnemonic: AWOL (Age80 years; unable to spell World backward; not fully Oriented to place; and moderate or severe iLlness severity).

It is estimated up to a third of hospital acquired delirium cases can be prevented.[10] Recent guidelines recommend the use of a multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium and provide evidence that such a strategy would be cost‐effective.[39] Nevertheless, such interventions are resource intense, requiring specialized nurse training and staffing[40] and have not been widely implemented. Acute care for the elderly units, where interventions to prevent delirium might logically be implemented, also require physical remodeling to provide carpeted hallways, handrails, and elevated toilet seats and door levers.[41] A method of risk stratification to identify the patients who would benefit most from resource‐intensive prevention strategies would be valuable.

The AWOL tool may provide a practical alternative to existing delirium prediction rules for adult medical inpatients. Because it can be completed by a nurse in <2 minutes, the AWOL tool may be easier to apply and disseminate than a previously described score relying on the MMSE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation scores, and measured visual acuity.[17] Two other tools, 1 based on chart abstraction[18] and the other based on clinical variables measured at admission,[19] are similarly easy to apply but only predict prevalent and not incident delirium, making them less clinically useful.

This study's strengths include its prospective cohort design and the derivation and validation being performed in different hospitals. The derivation cohort consisted of patients admitted to a tertiary care academic medical center or an affiliated hospital where routine mixed gender general medical patients are treated, whereas validation was performed at the SFVAMC, where patients are predominantly older men with a high incidence of vascular risk factors. The outcome was assessed on a daily basis, and the likelihood any cases were missed was low. Although there is some potential for bias because the outcome was assessed by a research assistant not blinded to baseline characteristics, this was mitigated by having each outcome validated by a blinded neurologist and in the validation cohort having the research assistant blinded to the AWOL score. Other strengths are the broad inclusion criteria, with both middle‐aged and elderly patients having a wide range of medical and neurological conditions, allowing for wide application of the results. Although many studies of delirium focus on patients over age 70 years, we chose to include patients aged 50 years or older because hospital‐acquired delirium still occurs in this age group (17 of 195 [8%] patients aged 5069 years became delirious in this study), and risk factors such as severe illness and cognitive dysfunction are likely to be predictors of delirium even at younger ages. Additionally, the inclusion of nurses' clinical judgment to assess illness severity using a straightforward rating scale allows bedside nurses to readily administer the prediction rule in practice.[34]

This study has several potential limitations. The number of outcomes in the derivation cohort was small compared to the number of predictors chosen for the prediction rule. This could potentially have led to overfitting the model in the derivation cohort and thus an overly optimistic estimation of the model's performance. In the validation cohort, the area under the ROC curve was lower than in the derivation cohort, and although the difference did not reach statistical significance, this may have been due to the small sample size. In addition, none of the 4 subjects with an AWOL score of 4 became delirious, potentially reflecting poor calibration of the prediction rule. However, the trend of higher rates of delirium among subjects with higher AWOL scores still reached statistical significance, and the prediction rule demonstrated good discrimination between patients at high and low risk for developing delirium.

To test whether a better prediction tool could be derived from our data, we combined the derivation and validation cohorts and repeated a stepwise multivariable logistic regression with the same variables used for derivation of the AWOL tool (with the exception of the whisper test of hearing and a past medical history of dementia, because these data were not collected in the validation cohort). This model produced the same 4 independent predictors of delirium used in the AWOL tool. We then used bootstrapping to internally validate the prediction rule, suggesting that the predictors in the AWOL tool were the best fit for the available data. However, given the small number of outcomes in our study, the AWOL tool may benefit from further validation in a larger independent cohort to more precisely calibrate the number of expected outcomes with each score.

Although the majority of medical inpatients were eligible for enrollment in our study, some populations were excluded, and our results may not generalize to these populations. Non‐English speaking patients were excluded to preserve the validity of our study instruments. In addition, patients with profound aphasia or an admission diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal were excluded. Patients discharged on the first day of their hospitalization were excluded either because they were discharged prior to screening or prior to their first follow‐up visit. Therefore, our results may only be valid in patients who remained in the hospital for over 24 hours. In addition, because we only included medical patients, our results cannot necessarily be generalized to the surgical population.

Finally, parts of the prediction rule (orientation and spelling world backward) are also components of the CAM and were used in the assessment of the outcome, and this may introduce a potential tautology: if patients are disoriented or have poor attention because they cannot spell world backward at admission, they already have fulfilled part of the criteria for delirium. However, a diagnosis of delirium using the CAM involves a comprehensive patient and caregiver interview, and in addition to poor attention, requires the presence of an acute change in mental status and disorganized thinking or altered level of consciousness. Therefore, it is possible, and common, for patients to be disoriented to place and/or unable to spell world backward, yet not be delirious, and predicting a subsequent change in cognition during the hospitalization is still clinically important. It is possible the AWOL tool works by identifying patients with impaired attention and subclinical delirium, but one could argue this makes a strong case for its validity because these patients especially should be triaged to an inpatient unit that specializes in delirium prevention. It is also possible the cognitive tasks that are part of the AWOL tool detect preexisting cognitive impairment, which is in turn a major risk factor for delirium.

Recognizing and classifying the risk of delirium during hospitalization is imperative, considering the illness' significant contribution to healthcare costs, morbidity, and mortality. The cost‐effectiveness of proven interventions to detect and prevent delirium could be magnified with focused implementation in those patients at highest risk.[39, 40, 41] Further research is required to determine whether the combination of delirium prediction rules such as those developed here and prevention strategies will result in decreased rates of delirium and economic savings for the healthcare system.

Acknowledgments

The following University of California, San Francisco neurology residents provided follow‐up of study subjects on weekends and were financially compensated: Amar Dhand, MD, DPhil; Tim West, MD; Sarah Shalev, MD; Karen DaSilva, MD; Mark Burish, MD, PhD; Maggie Waung, MD, PhD; Raquel Gardner, MD; Molly Burnett, MD; Adam Ziemann, MD, PhD; Kathryn Kvam, MD; Neel Singhal, MD, PhD; James Orengo, MD, PhD; Kelly Mills, MD; and Joanna Hellmuth, MD, MHS. The authors are grateful to Dr. Douglas Bauer for assisting with the study design.

Disclosures

Drs. Douglas, Hessler, Dhaliwal, Betjemann, Lucatorto, Johnston, Josephson, and Ms. Fukuda and Ms. Alameddine have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. This research was made possible by the Ruth E. Raskin Fund and a UCSF Dean's Research Scholarship. These funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

- , , . Occurrence and outcome of delirium in medical in‐patients: a systematic literature review. Age Ageing. 2006;35(4):350–364.

- , , , , , . Delirium in the intensive care unit: occurrence and clinical course in older patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(5):591–598.

- , , , , . One‐year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27–32.

- , , , , . Does delirium contribute to poor hospital outcomes? A three‐site epidemiologic study. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13(4):234–242.

- , , , , , . Delirium duration and mortality in lightly sedated, mechanically ventilated intensive care patients. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(12):2311–2318.

- , , , et al. Delirium epidemiology in critical care (DECCA): an international study. Crit Care. 2010;14(6):R210.

- , , , et al. Delirium as a predictor of long‐term cognitive impairment in survivors of critical illness. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(7):1513–1520.

- , , , , , . Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta‐analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443–451.

- , , , et al. Adverse outcomes after hospitalization and delirium in persons with Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(12):848–856.

- , , , et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669–676.

- , , , et al. Simple cognitive testing (Mini‐Cog) predicts in‐hospital delirium in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(2):314–316.

- , , . A prospective study of delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA. 1990;263(8):1097–1101.

- , . Precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized elderly persons. Predictive model and interrelationship with baseline vulnerability. JAMA. 1996;275(11):852–857.

- , , , , , . Risk factors for delirium at discharge: development and validation of a predictive model. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(13):1406–1413.

- , . Delirium in vascular surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2007;34(2):131–134.

- , , , , , . Delirium in hospitalized older persons: outcomes and predictors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(8):809–815.

- , , , , . A predictive model for delirium in hospitalized elderly medical patients based on admission characteristics. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(6):474–481.

- , , , , , . Validation of a medical record‐based delirium risk assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(suppl 2):S289–S294.

- , , , et al. Derivation and validation of a clinical prediction rule for delirium in patients admitted to a medical ward: an observational study. BMJ Open. 2012;2(5) pii: e001599.

- , , , et al. A clinical prediction rule for delirium after elective noncardiac surgery. JAMA. 1994;271(2):134–139.

- , , , , , . Prediction of postoperative delirium after abdominal surgery in the elderly. J Anesth. 2009;23(1):51–56.

- , , , et al. Derivation and validation of a preoperative prediction rule for delirium after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2009;119(2):229–236.

- , , , et al. Development and validation of PRE‐DELIRIC (PREdiction of DELIRium in ICu patients) delirium prediction model for intensive care patients: observational multicentre study. BMJ. 2012;344:e420.

- , , , , , . Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948.

- , , . “Mini‐mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198.

- . Wechsler Memory Scale‐III. New York, NY: Psychological Corp.; 1997.

- , , , , . The mini‐cog: a cognitive 'vital signs' measure for dementia screening in multi‐lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15(11):1021–1027.

- , . Functional evaluation: the Barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61–65.

- , , . The CAGE questionnaire: validation of a new alcoholism screening instrument. Am J Psychiatry. 1974;131(10):1121–1123.

- , , , , , . Is the NEI‐VFQ‐25 a useful tool in identifying visual impairment in an elderly population? BMC Ophthalmol. 2006;6:24.

- , , , et al. Validation of self‐reported hearing loss. The Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(6):1371–1378.

- , , . Does this patient have hearing impairment? JAMA. 2006;295(4):416–428.

- , , , , , . Realizing the potential of clinical judgment: a real‐time strategy for predicting outcomes and cost for medical inpatients. Am J Med. 2000;109(3):189–195.

- , , , , , . Assessing illness severity: does clinical judgment work? J Chronic Dis. 1986;39(6):439–452.

- , , , , , . Prognostication in acutely admitted older patients by nurses and physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(11):1883–1889.

- . The Confusion Assessment Method (CAM): Training Manual and Coding Guide. New Haven, CT: Yale University School of Medicine; 2003.

- , , , . Acute confusional states and dementia in the elderly: the role of dehydration/volume depletion, physical illness and age. Age Ageing. 1980;9(3):137–146.

- . A Wilcoxon‐type test for trend. Stat Med. 1985;4(1):87–90.

- , , , . Synopsis of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guideline for prevention of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(11):746–751.

- , , , , . The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1697–1706.

- , , , , . A randomized trial of care in a hospital medical unit especially designed to improve the functional outcomes of acutely ill older patients. N Engl J Med. 1995;332(20):1338–1344.

Delirium is characterized by fluctuating disturbances in cognition and consciousness and is a common complication of hospitalization in medical and surgical patients. Studies estimate the prevalence of delirium in hospitalized patients[1] to be 14% to 56%, and up to 70% in critically ill elderly patients.[2] Estimates of total healthcare costs associated with delirium range from $38 to $152 billion per year in the United States.[3] Delirious patients are more likely to be discharged to a nursing home and have increased hospital mortality and longer lengths of stay.[4, 5, 6] Recent data suggest long‐term effects of delirium including cognitive impairments up to 1 year following the illness[7] and an increased likelihood of developing[8] or worsening dementia.[9]

It is estimated that one‐third of hospital‐acquired delirium cases could be prevented with appropriate interventions.[10] A prediction rule that easily and accurately identifies high‐risk patients upon admission could therefore have a substantial clinical impact. In addition, a prediction rule could be used to identify patients in whom new targeted interventions for delirium prevention could be investigated. A number of risk factors for delirium have been identified, including older age, preexisting cognitive dysfunction, vision and hearing impairment, severe illness, dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, overmedication, and alcohol abuse.[11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] Existing prediction rules using various combinations of these measures have been limited by their complexity,[17] do not predict incident delirium,[18, 19] or are restricted to surgical[20, 21, 22] or intensive care[23] patients and therefore are not broadly applicable to the general medical population, which is particularly susceptible to developing delirium.

We conducted this study to develop a simple, efficient, and accurate prediction rule for hospital‐acquired delirium in adult medical inpatients assessed at the time of admission. Our a priori hypothesis was that a delirium prediction rule would consist of a combination of known risk factors and most likely incorporate old age, illness severity, and preexisting cognitive dysfunction.

METHODS

Design and Setting

This was a prospective cohort study with a derivation phase from May 2010 to November 2010 at 2 hospitals at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) (Moffitt‐Long and Mount Zion Hospitals) and a validation phase from October 2011 to March 2012 at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center (SFVAMC).

Participants and Measurements

Subject identification, recruitment, and inclusion and exclusion criteria were identical for the derivation and validation cohorts. Subjects were identified by reviewing daily admission logs. All non‐intensive care unit patients aged 50 years or older admitted through the emergency department to the medicine, cardiology, or neurology services were screened for eligibility through chart review or in person within 24 hours of admission by a trained research assistant. One research assistant, a college graduate, conducted all screening for the derivation cohort, and 2 research assistants, 1 a fourth‐year medical student and the other a third‐year psychology graduate student, conducted screening for the validation cohort. In‐person screening included an assessment for delirium using the long version of the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).[24] To minimize the possibility of enrolling delirious subjects, research assistants were instructed to notify the study supervisor (V.C.D.), a board‐certified neurologist, to discuss every case in which any yes checkbox was marked on the CAM score sheet. Subjects delirious upon initial evaluation, admitted for alcohol withdrawal, admitted for comfort care, who were aphasic or who could not speak English were excluded. For all patients, or if they were unable to provide consent, their surrogates provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards at UCSF and SFVAMC.

In the derivation cohort, 1241 patients were screened, and 439 were eligible for enrollment. Of these, 180 declined, 50 were discharged prior to the first follow‐up visit, and 209 were included. In the validation cohort, 420 patients were screened, and 368 were eligible for enrollment. Of these, 144 declined, 59 were discharged prior to the first follow‐up visit, and 165 were included.

Baseline data regarding known delirium risk factors[11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] were collected from subjects in the derivation cohort. Cognitive performance was assessed with the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE),[25] forward digit span,[26] and clock draw.[27] Permission for administration of the MMSE was granted by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., and each administration was paid for. A structured interview was conducted with validated questions regarding visual and hearing impairment, pain, mobility, place of residence, and alcohol, tobacco, and drug use.[28, 29, 30, 31] A whisper test for hearing loss was performed.[32] Subjects' charts were reviewed for demographic, clinical, and laboratory data. Illness severity was assessed by asking each subject's nurse to rate their patient on a scale from not ill to mildly ill, moderately ill, severely ill, or moribund.[33] Each nurse was shown these 5 choices, but more specific definitions of what each level of illness severity meant were not provided. We chose this method to assess illness severity because this rating scale was incorporated into a previous validated and widely cited delirium prediction rule.[17] This illness severity scale has been validated as a predictor of outcomes and correlates with other measures of illness severity and comorbidity when graded by physicians.[33, 34] Nurse and physician ratings of illness severity have been shown to be comparable,[35] and therefore if the scale were incorporated into the prediction rule it would allow nurses to perform it independently. In the validation cohort, only data required to complete the baseline CAM and apply the prediction rule were collected.

Assessment of Outcomes

All subjects were assessed for delirium daily for 6 days after enrollment or until discharge, whichever came first. Follow‐up was limited to 6 days, based on the assumption that delirium occurring beyond 1 week is more likely due to events during the hospitalization as opposed to factors measurable at admission. Delirium was assessed using the short CAM, an internationally recognized and validated tool.[24] To complete the CAM during follow‐up visits, subjects and their nurses were interviewed using a written script, and an MMSE and forward digit span were performed.

Daily follow‐up assessments were performed by research assistants who were not blinded to the initial assessment but who, in the validation phase, were blinded to the prediction rule score. Some weekend follow‐ups were performed by postgraduate year 2, 3, or 4 neurology residents, or internal medicine faculty experienced in the assessment of delirium and blinded to both the initial assessment and prediction rule score. Neurology residents and internists read the CAM training manual and were educated in the administration and scoring of the CAM by 1 of the senior investigators (V.C.D.) prior to their first shift; these nonstudy personnel covered 17 of 189 days of follow‐up in the derivation cohort and 21 of 169 days of follow‐up in the validation cohort. To maximize sensitivity of delirium detection, for any change in cognition, MMSE score, or forward digit span compared to baseline, a board‐certified neurologist blinded to the initial assessment was notified to discuss the case and validate the diagnosis of delirium in person (derivation cohort) or over the phone (validation cohort). All research assistants were trained by a board‐certified neurologist (V.C.D.) in the administration and interpretation of the CAM using published methods prior to enrollment of any subjects.[36] Training included the performance of independent long‐version CAMs by the trainer and the trainee on a series of delirious and nondelirious patients until there was consistent agreement for each item on the CAM in 5 consecutive patients. In addition, a board‐certified neurologist supervised the first 5 administrations of the CAM performed by each research assistant.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size for the derivation cohort was based on the predicted ability to detect a difference in rates of delirium among those with and without cognitive impairment, the strongest risk factor for delirium. Using a [2] test with an of 0.05 and of 0.80, we estimated we would need to enroll 260 subjects, assuming a prevalence of cognitive dysfunction in our cohort of 10% and an estimated rate of delirium of 24% and 6% among those with and without cognitive dysfunction respectively.[14, 16, 17, 20] We were unable to reach enrollment targets because of a short funding period and slower than expected recruitment.

To construct the prediction rule in the derivation cohort, all variables were dichotomized. Age was dichotomized at 80 years because old age is a known risk factor for delirium, and only 1 of 46 subjects between the ages of 70 and 80 years became delirious in the derivation cohort. Components of the MMSE were dichotomized as correct/emncorrect, with a correct response requiring perfect performance based on expert consensus. For 3 subjects who would not attempt to spell world backward (2 in the derivation and 1 in the validation cohort), their score on serial 7s was used instead. The total MMSE score was not used because our objective was to develop a prediction rule using elements that could be assessed quickly in the fast‐paced environment of the hospital. Illness severity was dichotomized at moderate or worse/mild or better because there were only 15 subjects in the severe illness category, and the majority of delirium (22 outcomes) occurred in the moderate illness category. High blood urea nitrogen:creatinine ratio was defined as >18.[37]

The association between predictor variables and occurrence of delirium was analyzed using univariate logistic regression. A forward stepwise logistic regression was then performed using the variables associated with the outcome at a significance level of P<0.05 in univariate analysis. Variables were eligible for addition to the multivariable model if they were associated with the outcome at a significance level of <0.05. The 4 independent predictors thus identified were combined into a prediction rule by assigning each predictor 1 point if present. The performance of the prediction rule was assessed by using Cuzick's nonparametric test for a trend across groups ordered by score.[38]

The prediction rule was tested in the validation cohort using the nonparametric test for trend. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were compared between the derivation and validation cohorts. All statistical analysis was performed using Stata software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The derivation cohort consisted of elderly patients (mean age, 68.0811.96 years; interquartile range, 5096 years), and included more males than females (54.1% vs 45.9%). Subjects were predominantly white (73.7%) and lived at home (90%) (Table 1). The mean admission MMSE score was 27.0 (standard deviation [SD], 3.4; range, 730). Median follow‐up was 2 days (interquartile range, 13). Delirium developed in 12% (n=25) of the cohort.

| Derivation Cohort, N=209 | Validation Cohort, N=165 | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Gender, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 113 (54) | 157 (95) |

| Female | 96 (46) | 8 (4.8) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||

| White | 154 (74) | 125 (76) |

| African American | 34 (16) | 25 (15) |

| Asian | 21 (10.0) | 13 (7.9) |

| Native American | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Illness severity, No. (%) | ||

| Not ill | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Mildly ill | 49 (23) | 62 (38) |

| Moderately ill | 129 (62) | 86 (52) |

| Severely ill | 15 (7.2) | 17 (10) |

| Moribund | 0 | 0 |

| Living situation, No. (%) | ||

| Home | 188 (90) | 147 (89) |

| Assisted living | 11 (5.3) | 6 (3.6) |

| Hotel | 4 (1.9) | 5 (3.0) |

| SNF | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.8) |

| Homeless | 4 (1.9) | 4 (2.4) |

| Developed delirium | 25 (12) | 14 (8.5) |

Univariate analysis of the derivation study identified 10 variables significantly associated (P<0.05) with delirium (Table 2). Predictors of delirium included abnormal scores on 4 subtests of the MMSE, low score on the Mini‐Cog, living in an assisted living or skilled nursing facility, moderate to severe illness, old age, a past history of dementia, and hearing loss as assessed by the whisper test. These predictors were then entered into a stepwise logistic regression analysis that identified 4 independent predictors of delirium (Table 3).

| Variable | No. (%) Without Delirium | No. (%) With Delirium | Odds Ratio | P Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Age 80 years | 30 (16) | 13 (52) | 5.6 | <0.001 | 2.313.4 |

| Male sex | 99 (54) | 14 (56) | 1.1 | 0.84 | 0.52.5 |

| White race | 135 (73) | 19 (76) | 1.2 | 0.78 | 0.433.1 |

| Score <5 on date questions of MMSE | 37 (20) | 12 (48) | 3.7 | 0.003 | 1.68.7 |

| Score <5 on place questions of MMSE | 50 (27) | 14 (56) | 3.4 | 0.005 | 1.58.0 |

| Score <3 on MMSE recall | 89 (48) | 18 (72) | 2.7 | 0.03 | 1.16.9 |

| Score <5 on MMSE W‐O‐R‐L‐D backward | 37 (20) | 13 (52) | 4.3 | 0.001 | 1.810.2 |

| Score 0 on MMSE pentagon copy, n=203 | 53 (30) | 12 (48) | 2.2 | 0.07 | 0.935.1 |

| Score 0 on clock draw, n=203 | 70 (39) | 15 (60) | 2.3 | 0.05 | 0.985.4 |

| MiniCog score 02, n=203[27] | 46 (26) | 12 (48) | 2.7 | 0.03 | 1.16.2 |

| Self‐rated vision fair, poor, or very poor | 55 (30) | 8 (32) | 1.1 | 0.83 | 0.452.7 |

| Endorses hearing loss | 89 (48) | 12 (48) | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.432.3 |

| Uses hearing aid | 19 (10) | 2 (8) | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.173.5 |

| Fails whisper test in either ear | 39 (21) | 10 (40) | 2.5 | 0.04 | 1.05.9 |

| Prior episode of delirium per patient or informant | 70 (38) | 13 (52) | 1.8 | 0.19 | 0.764.1 |

| Dementia in past medical history | 3 (2) | 3 (12) | 8.2 | 0.01 | 1.643.3 |

| Depression in past medical history | 16 (9) | 1 (4) | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.063.5 |

| Lives in assisted living or SNF | 8 (4) | 4 (16) | 4.2 | 0.03 | 1.215.1 |

| Endorses pain | 82 (45) | 7 (28) | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.191.2 |

| Less than independent for transfers | 11 (6) | 3 (12) | 2.1 | 0.27 | 0.568.3 |

| Less than independent for mobility on a level surface | 36 (20) | 7 (28) | 1.6 | 0.33 | 0.624.1 |

| Score of 24 on CAGE questionnaire[29] | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | No outcomes | ||

| Drinks any alcohol | 84 (46) | 10 (40) | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.341.9 |

| Current smoker | 20 (11) | 2 (8) | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.164.1 |

| Uses illicit drugs | 13 (7) | 2 (8) | 1.2 | 0.83 | 0.255.6 |

| Moderately or severely ill on nursing assessment, n=194 | 121 (71) | 23 (96) | 9.3 | 0.031 | 1.270.9 |

| Fever | 8 (4) | 0 (0) | No outcomes | ||

| Serum sodium <134mmol/L | 38 (21) | 3 (12) | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.151.8 |

| WBC count>10109/L, n=208 | 57 (31) | 6 (24) | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.261.8 |

| AST>41 U/L, n=131 | 27 (23) | 2 (15) | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.132.9 |

| BUN:Cr>18, n=208 | 66 (36) | 13 (52) | 1.9 | 0.13 | 0.834.5 |

| Infection as admission diagnosis | 28 (15) | 4 (16) | 1.1 | 0.92 | 0.343.3 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value | Points Toward AWOL Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 80 years | 5.7 | 2.115.6 | 0.001 | 1 |

| Unable to correctly spell world backward | 3.5 | 1.39.6 | 0.01 | 1 |

| Not oriented to city, state, county, hospital name, and floor | 2.9 | 1.17.9 | 0.03 | 1 |

| Nursing illness severity assessment of moderately ill, severely ill, or moribund (as opposed to not ill or mildly ill) | 10.5 | 1.386.9 | 0.03 | 1 |

These 4 independent predictors were assigned 1 point each if present to create a prediction rule with a range of possible scores from 0 to 4. There was a significant trend predicting higher rates of delirium with higher scores, with no subjects who scored 0 becoming delirious, compared to 40% of those subjects scoring 3 or 4 (P for trend<0.001) (Table 4).

| Derivation Cohorta | Validation Cohort | Combined Cohorts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWOL Score | Not Delirious | Delirious | Not Delirious | Delirious | Not Delirious | Delirious |

| ||||||

| 0 | 26 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (96%) | 1 (4%) | 49 (98%) | 1 (2%) |

| 1 | 86 (95%) | 5 (5%) | 57 (97%) | 2 (3%) | 136 (96%) | 5 (4%) |

| 2 | 41 (85%) | 7 (15%) | 44 (90%) | 5 (10%) | 92 (86%) | 15 (14%) |

| 3 | 17 (74%) | 6 (26%) | 22 (79%) | 6 (21%) | 40 (80%) | 10 (20%) |

| 4 | 0 (0%) | 6 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (36%) | 7 (64%) |

| Total | 170 | 24 | 151 | 14 | 321 | 38 |

| P<0.001 | P=0.025 | P<0.001 | ||||

The validation cohort consisted of adults with a mean age of 70.7210.6 years, (interquartile range, 5194 years), who were predominantly white (75.8%) and overwhelmingly male (95.2%) (Table 1). The mean admission MMSE score was 26.75 (SD, 2.8; range, 1730). Median follow‐up was 2 days (interquartile range, 15). Delirium developed in 8.5% (n=14) of the cohort. In the validation cohort, 4% of subjects with a score of 0 became delirious, whereas 19% of those scoring 3 or 4 became delirious (P for trend 0.025) (Table 4).

ROC curves were compared for the derivation and validation cohorts. The area under the ROC curve for the derivation cohort (0.81, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.720.90) was slightly better than that in the validation cohort (0.69, 95% CI: 0.540.83), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.14) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

We derived and validated a prediction rule to assess the risk of developing delirium in hospitalized adult medical patients. Four variables easily assessed on admission in a screen lasting less than 2 minutes were independently associated with the development of delirium. The prediction rule can be remembered with the following mnemonic: AWOL (Age80 years; unable to spell World backward; not fully Oriented to place; and moderate or severe iLlness severity).

It is estimated up to a third of hospital acquired delirium cases can be prevented.[10] Recent guidelines recommend the use of a multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium and provide evidence that such a strategy would be cost‐effective.[39] Nevertheless, such interventions are resource intense, requiring specialized nurse training and staffing[40] and have not been widely implemented. Acute care for the elderly units, where interventions to prevent delirium might logically be implemented, also require physical remodeling to provide carpeted hallways, handrails, and elevated toilet seats and door levers.[41] A method of risk stratification to identify the patients who would benefit most from resource‐intensive prevention strategies would be valuable.

The AWOL tool may provide a practical alternative to existing delirium prediction rules for adult medical inpatients. Because it can be completed by a nurse in <2 minutes, the AWOL tool may be easier to apply and disseminate than a previously described score relying on the MMSE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation scores, and measured visual acuity.[17] Two other tools, 1 based on chart abstraction[18] and the other based on clinical variables measured at admission,[19] are similarly easy to apply but only predict prevalent and not incident delirium, making them less clinically useful.

This study's strengths include its prospective cohort design and the derivation and validation being performed in different hospitals. The derivation cohort consisted of patients admitted to a tertiary care academic medical center or an affiliated hospital where routine mixed gender general medical patients are treated, whereas validation was performed at the SFVAMC, where patients are predominantly older men with a high incidence of vascular risk factors. The outcome was assessed on a daily basis, and the likelihood any cases were missed was low. Although there is some potential for bias because the outcome was assessed by a research assistant not blinded to baseline characteristics, this was mitigated by having each outcome validated by a blinded neurologist and in the validation cohort having the research assistant blinded to the AWOL score. Other strengths are the broad inclusion criteria, with both middle‐aged and elderly patients having a wide range of medical and neurological conditions, allowing for wide application of the results. Although many studies of delirium focus on patients over age 70 years, we chose to include patients aged 50 years or older because hospital‐acquired delirium still occurs in this age group (17 of 195 [8%] patients aged 5069 years became delirious in this study), and risk factors such as severe illness and cognitive dysfunction are likely to be predictors of delirium even at younger ages. Additionally, the inclusion of nurses' clinical judgment to assess illness severity using a straightforward rating scale allows bedside nurses to readily administer the prediction rule in practice.[34]

This study has several potential limitations. The number of outcomes in the derivation cohort was small compared to the number of predictors chosen for the prediction rule. This could potentially have led to overfitting the model in the derivation cohort and thus an overly optimistic estimation of the model's performance. In the validation cohort, the area under the ROC curve was lower than in the derivation cohort, and although the difference did not reach statistical significance, this may have been due to the small sample size. In addition, none of the 4 subjects with an AWOL score of 4 became delirious, potentially reflecting poor calibration of the prediction rule. However, the trend of higher rates of delirium among subjects with higher AWOL scores still reached statistical significance, and the prediction rule demonstrated good discrimination between patients at high and low risk for developing delirium.

To test whether a better prediction tool could be derived from our data, we combined the derivation and validation cohorts and repeated a stepwise multivariable logistic regression with the same variables used for derivation of the AWOL tool (with the exception of the whisper test of hearing and a past medical history of dementia, because these data were not collected in the validation cohort). This model produced the same 4 independent predictors of delirium used in the AWOL tool. We then used bootstrapping to internally validate the prediction rule, suggesting that the predictors in the AWOL tool were the best fit for the available data. However, given the small number of outcomes in our study, the AWOL tool may benefit from further validation in a larger independent cohort to more precisely calibrate the number of expected outcomes with each score.

Although the majority of medical inpatients were eligible for enrollment in our study, some populations were excluded, and our results may not generalize to these populations. Non‐English speaking patients were excluded to preserve the validity of our study instruments. In addition, patients with profound aphasia or an admission diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal were excluded. Patients discharged on the first day of their hospitalization were excluded either because they were discharged prior to screening or prior to their first follow‐up visit. Therefore, our results may only be valid in patients who remained in the hospital for over 24 hours. In addition, because we only included medical patients, our results cannot necessarily be generalized to the surgical population.

Finally, parts of the prediction rule (orientation and spelling world backward) are also components of the CAM and were used in the assessment of the outcome, and this may introduce a potential tautology: if patients are disoriented or have poor attention because they cannot spell world backward at admission, they already have fulfilled part of the criteria for delirium. However, a diagnosis of delirium using the CAM involves a comprehensive patient and caregiver interview, and in addition to poor attention, requires the presence of an acute change in mental status and disorganized thinking or altered level of consciousness. Therefore, it is possible, and common, for patients to be disoriented to place and/or unable to spell world backward, yet not be delirious, and predicting a subsequent change in cognition during the hospitalization is still clinically important. It is possible the AWOL tool works by identifying patients with impaired attention and subclinical delirium, but one could argue this makes a strong case for its validity because these patients especially should be triaged to an inpatient unit that specializes in delirium prevention. It is also possible the cognitive tasks that are part of the AWOL tool detect preexisting cognitive impairment, which is in turn a major risk factor for delirium.

Recognizing and classifying the risk of delirium during hospitalization is imperative, considering the illness' significant contribution to healthcare costs, morbidity, and mortality. The cost‐effectiveness of proven interventions to detect and prevent delirium could be magnified with focused implementation in those patients at highest risk.[39, 40, 41] Further research is required to determine whether the combination of delirium prediction rules such as those developed here and prevention strategies will result in decreased rates of delirium and economic savings for the healthcare system.

Acknowledgments

The following University of California, San Francisco neurology residents provided follow‐up of study subjects on weekends and were financially compensated: Amar Dhand, MD, DPhil; Tim West, MD; Sarah Shalev, MD; Karen DaSilva, MD; Mark Burish, MD, PhD; Maggie Waung, MD, PhD; Raquel Gardner, MD; Molly Burnett, MD; Adam Ziemann, MD, PhD; Kathryn Kvam, MD; Neel Singhal, MD, PhD; James Orengo, MD, PhD; Kelly Mills, MD; and Joanna Hellmuth, MD, MHS. The authors are grateful to Dr. Douglas Bauer for assisting with the study design.

Disclosures

Drs. Douglas, Hessler, Dhaliwal, Betjemann, Lucatorto, Johnston, Josephson, and Ms. Fukuda and Ms. Alameddine have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. This research was made possible by the Ruth E. Raskin Fund and a UCSF Dean's Research Scholarship. These funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Delirium is characterized by fluctuating disturbances in cognition and consciousness and is a common complication of hospitalization in medical and surgical patients. Studies estimate the prevalence of delirium in hospitalized patients[1] to be 14% to 56%, and up to 70% in critically ill elderly patients.[2] Estimates of total healthcare costs associated with delirium range from $38 to $152 billion per year in the United States.[3] Delirious patients are more likely to be discharged to a nursing home and have increased hospital mortality and longer lengths of stay.[4, 5, 6] Recent data suggest long‐term effects of delirium including cognitive impairments up to 1 year following the illness[7] and an increased likelihood of developing[8] or worsening dementia.[9]

It is estimated that one‐third of hospital‐acquired delirium cases could be prevented with appropriate interventions.[10] A prediction rule that easily and accurately identifies high‐risk patients upon admission could therefore have a substantial clinical impact. In addition, a prediction rule could be used to identify patients in whom new targeted interventions for delirium prevention could be investigated. A number of risk factors for delirium have been identified, including older age, preexisting cognitive dysfunction, vision and hearing impairment, severe illness, dehydration, electrolyte abnormalities, overmedication, and alcohol abuse.[11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] Existing prediction rules using various combinations of these measures have been limited by their complexity,[17] do not predict incident delirium,[18, 19] or are restricted to surgical[20, 21, 22] or intensive care[23] patients and therefore are not broadly applicable to the general medical population, which is particularly susceptible to developing delirium.

We conducted this study to develop a simple, efficient, and accurate prediction rule for hospital‐acquired delirium in adult medical inpatients assessed at the time of admission. Our a priori hypothesis was that a delirium prediction rule would consist of a combination of known risk factors and most likely incorporate old age, illness severity, and preexisting cognitive dysfunction.

METHODS

Design and Setting

This was a prospective cohort study with a derivation phase from May 2010 to November 2010 at 2 hospitals at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) (Moffitt‐Long and Mount Zion Hospitals) and a validation phase from October 2011 to March 2012 at the San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center (SFVAMC).

Participants and Measurements

Subject identification, recruitment, and inclusion and exclusion criteria were identical for the derivation and validation cohorts. Subjects were identified by reviewing daily admission logs. All non‐intensive care unit patients aged 50 years or older admitted through the emergency department to the medicine, cardiology, or neurology services were screened for eligibility through chart review or in person within 24 hours of admission by a trained research assistant. One research assistant, a college graduate, conducted all screening for the derivation cohort, and 2 research assistants, 1 a fourth‐year medical student and the other a third‐year psychology graduate student, conducted screening for the validation cohort. In‐person screening included an assessment for delirium using the long version of the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).[24] To minimize the possibility of enrolling delirious subjects, research assistants were instructed to notify the study supervisor (V.C.D.), a board‐certified neurologist, to discuss every case in which any yes checkbox was marked on the CAM score sheet. Subjects delirious upon initial evaluation, admitted for alcohol withdrawal, admitted for comfort care, who were aphasic or who could not speak English were excluded. For all patients, or if they were unable to provide consent, their surrogates provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the institutional review boards at UCSF and SFVAMC.

In the derivation cohort, 1241 patients were screened, and 439 were eligible for enrollment. Of these, 180 declined, 50 were discharged prior to the first follow‐up visit, and 209 were included. In the validation cohort, 420 patients were screened, and 368 were eligible for enrollment. Of these, 144 declined, 59 were discharged prior to the first follow‐up visit, and 165 were included.

Baseline data regarding known delirium risk factors[11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16] were collected from subjects in the derivation cohort. Cognitive performance was assessed with the Mini Mental Status Examination (MMSE),[25] forward digit span,[26] and clock draw.[27] Permission for administration of the MMSE was granted by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., and each administration was paid for. A structured interview was conducted with validated questions regarding visual and hearing impairment, pain, mobility, place of residence, and alcohol, tobacco, and drug use.[28, 29, 30, 31] A whisper test for hearing loss was performed.[32] Subjects' charts were reviewed for demographic, clinical, and laboratory data. Illness severity was assessed by asking each subject's nurse to rate their patient on a scale from not ill to mildly ill, moderately ill, severely ill, or moribund.[33] Each nurse was shown these 5 choices, but more specific definitions of what each level of illness severity meant were not provided. We chose this method to assess illness severity because this rating scale was incorporated into a previous validated and widely cited delirium prediction rule.[17] This illness severity scale has been validated as a predictor of outcomes and correlates with other measures of illness severity and comorbidity when graded by physicians.[33, 34] Nurse and physician ratings of illness severity have been shown to be comparable,[35] and therefore if the scale were incorporated into the prediction rule it would allow nurses to perform it independently. In the validation cohort, only data required to complete the baseline CAM and apply the prediction rule were collected.

Assessment of Outcomes

All subjects were assessed for delirium daily for 6 days after enrollment or until discharge, whichever came first. Follow‐up was limited to 6 days, based on the assumption that delirium occurring beyond 1 week is more likely due to events during the hospitalization as opposed to factors measurable at admission. Delirium was assessed using the short CAM, an internationally recognized and validated tool.[24] To complete the CAM during follow‐up visits, subjects and their nurses were interviewed using a written script, and an MMSE and forward digit span were performed.

Daily follow‐up assessments were performed by research assistants who were not blinded to the initial assessment but who, in the validation phase, were blinded to the prediction rule score. Some weekend follow‐ups were performed by postgraduate year 2, 3, or 4 neurology residents, or internal medicine faculty experienced in the assessment of delirium and blinded to both the initial assessment and prediction rule score. Neurology residents and internists read the CAM training manual and were educated in the administration and scoring of the CAM by 1 of the senior investigators (V.C.D.) prior to their first shift; these nonstudy personnel covered 17 of 189 days of follow‐up in the derivation cohort and 21 of 169 days of follow‐up in the validation cohort. To maximize sensitivity of delirium detection, for any change in cognition, MMSE score, or forward digit span compared to baseline, a board‐certified neurologist blinded to the initial assessment was notified to discuss the case and validate the diagnosis of delirium in person (derivation cohort) or over the phone (validation cohort). All research assistants were trained by a board‐certified neurologist (V.C.D.) in the administration and interpretation of the CAM using published methods prior to enrollment of any subjects.[36] Training included the performance of independent long‐version CAMs by the trainer and the trainee on a series of delirious and nondelirious patients until there was consistent agreement for each item on the CAM in 5 consecutive patients. In addition, a board‐certified neurologist supervised the first 5 administrations of the CAM performed by each research assistant.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size for the derivation cohort was based on the predicted ability to detect a difference in rates of delirium among those with and without cognitive impairment, the strongest risk factor for delirium. Using a [2] test with an of 0.05 and of 0.80, we estimated we would need to enroll 260 subjects, assuming a prevalence of cognitive dysfunction in our cohort of 10% and an estimated rate of delirium of 24% and 6% among those with and without cognitive dysfunction respectively.[14, 16, 17, 20] We were unable to reach enrollment targets because of a short funding period and slower than expected recruitment.

To construct the prediction rule in the derivation cohort, all variables were dichotomized. Age was dichotomized at 80 years because old age is a known risk factor for delirium, and only 1 of 46 subjects between the ages of 70 and 80 years became delirious in the derivation cohort. Components of the MMSE were dichotomized as correct/emncorrect, with a correct response requiring perfect performance based on expert consensus. For 3 subjects who would not attempt to spell world backward (2 in the derivation and 1 in the validation cohort), their score on serial 7s was used instead. The total MMSE score was not used because our objective was to develop a prediction rule using elements that could be assessed quickly in the fast‐paced environment of the hospital. Illness severity was dichotomized at moderate or worse/mild or better because there were only 15 subjects in the severe illness category, and the majority of delirium (22 outcomes) occurred in the moderate illness category. High blood urea nitrogen:creatinine ratio was defined as >18.[37]

The association between predictor variables and occurrence of delirium was analyzed using univariate logistic regression. A forward stepwise logistic regression was then performed using the variables associated with the outcome at a significance level of P<0.05 in univariate analysis. Variables were eligible for addition to the multivariable model if they were associated with the outcome at a significance level of <0.05. The 4 independent predictors thus identified were combined into a prediction rule by assigning each predictor 1 point if present. The performance of the prediction rule was assessed by using Cuzick's nonparametric test for a trend across groups ordered by score.[38]

The prediction rule was tested in the validation cohort using the nonparametric test for trend. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were compared between the derivation and validation cohorts. All statistical analysis was performed using Stata software (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

The derivation cohort consisted of elderly patients (mean age, 68.0811.96 years; interquartile range, 5096 years), and included more males than females (54.1% vs 45.9%). Subjects were predominantly white (73.7%) and lived at home (90%) (Table 1). The mean admission MMSE score was 27.0 (standard deviation [SD], 3.4; range, 730). Median follow‐up was 2 days (interquartile range, 13). Delirium developed in 12% (n=25) of the cohort.

| Derivation Cohort, N=209 | Validation Cohort, N=165 | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Gender, No. (%) | ||

| Male | 113 (54) | 157 (95) |

| Female | 96 (46) | 8 (4.8) |

| Race, No. (%) | ||

| White | 154 (74) | 125 (76) |

| African American | 34 (16) | 25 (15) |

| Asian | 21 (10.0) | 13 (7.9) |

| Native American | 0 | 2 (1.2) |

| Illness severity, No. (%) | ||

| Not ill | 1 (0.5) | 0 |

| Mildly ill | 49 (23) | 62 (38) |

| Moderately ill | 129 (62) | 86 (52) |

| Severely ill | 15 (7.2) | 17 (10) |

| Moribund | 0 | 0 |

| Living situation, No. (%) | ||

| Home | 188 (90) | 147 (89) |

| Assisted living | 11 (5.3) | 6 (3.6) |

| Hotel | 4 (1.9) | 5 (3.0) |

| SNF | 1 (0.5) | 3 (1.8) |

| Homeless | 4 (1.9) | 4 (2.4) |

| Developed delirium | 25 (12) | 14 (8.5) |

Univariate analysis of the derivation study identified 10 variables significantly associated (P<0.05) with delirium (Table 2). Predictors of delirium included abnormal scores on 4 subtests of the MMSE, low score on the Mini‐Cog, living in an assisted living or skilled nursing facility, moderate to severe illness, old age, a past history of dementia, and hearing loss as assessed by the whisper test. These predictors were then entered into a stepwise logistic regression analysis that identified 4 independent predictors of delirium (Table 3).

| Variable | No. (%) Without Delirium | No. (%) With Delirium | Odds Ratio | P Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Age 80 years | 30 (16) | 13 (52) | 5.6 | <0.001 | 2.313.4 |

| Male sex | 99 (54) | 14 (56) | 1.1 | 0.84 | 0.52.5 |

| White race | 135 (73) | 19 (76) | 1.2 | 0.78 | 0.433.1 |

| Score <5 on date questions of MMSE | 37 (20) | 12 (48) | 3.7 | 0.003 | 1.68.7 |

| Score <5 on place questions of MMSE | 50 (27) | 14 (56) | 3.4 | 0.005 | 1.58.0 |

| Score <3 on MMSE recall | 89 (48) | 18 (72) | 2.7 | 0.03 | 1.16.9 |

| Score <5 on MMSE W‐O‐R‐L‐D backward | 37 (20) | 13 (52) | 4.3 | 0.001 | 1.810.2 |

| Score 0 on MMSE pentagon copy, n=203 | 53 (30) | 12 (48) | 2.2 | 0.07 | 0.935.1 |

| Score 0 on clock draw, n=203 | 70 (39) | 15 (60) | 2.3 | 0.05 | 0.985.4 |

| MiniCog score 02, n=203[27] | 46 (26) | 12 (48) | 2.7 | 0.03 | 1.16.2 |

| Self‐rated vision fair, poor, or very poor | 55 (30) | 8 (32) | 1.1 | 0.83 | 0.452.7 |

| Endorses hearing loss | 89 (48) | 12 (48) | 0.99 | 0.97 | 0.432.3 |

| Uses hearing aid | 19 (10) | 2 (8) | 0.76 | 0.72 | 0.173.5 |

| Fails whisper test in either ear | 39 (21) | 10 (40) | 2.5 | 0.04 | 1.05.9 |

| Prior episode of delirium per patient or informant | 70 (38) | 13 (52) | 1.8 | 0.19 | 0.764.1 |

| Dementia in past medical history | 3 (2) | 3 (12) | 8.2 | 0.01 | 1.643.3 |

| Depression in past medical history | 16 (9) | 1 (4) | 0.44 | 0.43 | 0.063.5 |

| Lives in assisted living or SNF | 8 (4) | 4 (16) | 4.2 | 0.03 | 1.215.1 |

| Endorses pain | 82 (45) | 7 (28) | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.191.2 |

| Less than independent for transfers | 11 (6) | 3 (12) | 2.1 | 0.27 | 0.568.3 |

| Less than independent for mobility on a level surface | 36 (20) | 7 (28) | 1.6 | 0.33 | 0.624.1 |

| Score of 24 on CAGE questionnaire[29] | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | No outcomes | ||

| Drinks any alcohol | 84 (46) | 10 (40) | 0.79 | 0.60 | 0.341.9 |

| Current smoker | 20 (11) | 2 (8) | 0.71 | 0.66 | 0.164.1 |

| Uses illicit drugs | 13 (7) | 2 (8) | 1.2 | 0.83 | 0.255.6 |

| Moderately or severely ill on nursing assessment, n=194 | 121 (71) | 23 (96) | 9.3 | 0.031 | 1.270.9 |

| Fever | 8 (4) | 0 (0) | No outcomes | ||

| Serum sodium <134mmol/L | 38 (21) | 3 (12) | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.151.8 |

| WBC count>10109/L, n=208 | 57 (31) | 6 (24) | 0.70 | 0.47 | 0.261.8 |

| AST>41 U/L, n=131 | 27 (23) | 2 (15) | 0.61 | 0.54 | 0.132.9 |

| BUN:Cr>18, n=208 | 66 (36) | 13 (52) | 1.9 | 0.13 | 0.834.5 |

| Infection as admission diagnosis | 28 (15) | 4 (16) | 1.1 | 0.92 | 0.343.3 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value | Points Toward AWOL Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age 80 years | 5.7 | 2.115.6 | 0.001 | 1 |

| Unable to correctly spell world backward | 3.5 | 1.39.6 | 0.01 | 1 |

| Not oriented to city, state, county, hospital name, and floor | 2.9 | 1.17.9 | 0.03 | 1 |

| Nursing illness severity assessment of moderately ill, severely ill, or moribund (as opposed to not ill or mildly ill) | 10.5 | 1.386.9 | 0.03 | 1 |

These 4 independent predictors were assigned 1 point each if present to create a prediction rule with a range of possible scores from 0 to 4. There was a significant trend predicting higher rates of delirium with higher scores, with no subjects who scored 0 becoming delirious, compared to 40% of those subjects scoring 3 or 4 (P for trend<0.001) (Table 4).

| Derivation Cohorta | Validation Cohort | Combined Cohorts | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AWOL Score | Not Delirious | Delirious | Not Delirious | Delirious | Not Delirious | Delirious |

| ||||||

| 0 | 26 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (96%) | 1 (4%) | 49 (98%) | 1 (2%) |

| 1 | 86 (95%) | 5 (5%) | 57 (97%) | 2 (3%) | 136 (96%) | 5 (4%) |

| 2 | 41 (85%) | 7 (15%) | 44 (90%) | 5 (10%) | 92 (86%) | 15 (14%) |

| 3 | 17 (74%) | 6 (26%) | 22 (79%) | 6 (21%) | 40 (80%) | 10 (20%) |

| 4 | 0 (0%) | 6 (100%) | 4 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (36%) | 7 (64%) |

| Total | 170 | 24 | 151 | 14 | 321 | 38 |

| P<0.001 | P=0.025 | P<0.001 | ||||

The validation cohort consisted of adults with a mean age of 70.7210.6 years, (interquartile range, 5194 years), who were predominantly white (75.8%) and overwhelmingly male (95.2%) (Table 1). The mean admission MMSE score was 26.75 (SD, 2.8; range, 1730). Median follow‐up was 2 days (interquartile range, 15). Delirium developed in 8.5% (n=14) of the cohort. In the validation cohort, 4% of subjects with a score of 0 became delirious, whereas 19% of those scoring 3 or 4 became delirious (P for trend 0.025) (Table 4).

ROC curves were compared for the derivation and validation cohorts. The area under the ROC curve for the derivation cohort (0.81, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.720.90) was slightly better than that in the validation cohort (0.69, 95% CI: 0.540.83), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P=0.14) (Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

We derived and validated a prediction rule to assess the risk of developing delirium in hospitalized adult medical patients. Four variables easily assessed on admission in a screen lasting less than 2 minutes were independently associated with the development of delirium. The prediction rule can be remembered with the following mnemonic: AWOL (Age80 years; unable to spell World backward; not fully Oriented to place; and moderate or severe iLlness severity).

It is estimated up to a third of hospital acquired delirium cases can be prevented.[10] Recent guidelines recommend the use of a multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium and provide evidence that such a strategy would be cost‐effective.[39] Nevertheless, such interventions are resource intense, requiring specialized nurse training and staffing[40] and have not been widely implemented. Acute care for the elderly units, where interventions to prevent delirium might logically be implemented, also require physical remodeling to provide carpeted hallways, handrails, and elevated toilet seats and door levers.[41] A method of risk stratification to identify the patients who would benefit most from resource‐intensive prevention strategies would be valuable.