User login

Online Entry-Level Education: The Jury Is Still Out!

I consider my role as an editorialist to be to inform, persuade, or—sometimes—just comment on current issues that affect PAs and NPs. There have been many opportunities in recent years to address “hot” topics, and this is certainly one of them: the rise of distance entry-level education for health professions students.

The catalyst for this discussion? Earlier this year, Yale University announced it was launching an online entry-level PA program.1 Within minutes of that announcement, there was a conflagration of criticism from the profession, alumni, and the general public. Most of the backlash centered on concerns about adequate delivery of such intense content—including how to instill or enhance professional behaviors and attitudes, or teach hands-on procedures, objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs), and physical exam techniques—from a distance.

In our professions, we tend to be fairly conservative when it comes to change—particularly in terms of innovations in our education programs. But as e-learning, simulations, and distance education modalities become ever more prevalent across the spectrum of higher learning, we require an improved understanding of how these methods will transform entry-level education for health care providers.

Until recently, there has been minimal data on the impact of these technologic advances and teaching methods in health professions education, although this is changing.2 We do have a research gap when it comes to the effect of learning style on NP and PA students’ perceptions of online instruction (despite the rapidly increasing use of it). We also have not firmly established how this delivery method affects professional development (ie, how effectively it prepares clinicians to provide care to patients). None of this has prevented the proliferation of these concepts.

While many were stunned by the Yale venture, it should be noted that the idea is not new. Rather, such programs have steadily become part of health professions education (particularly nursing) in recent years.3 Yale itself was an early adopter of “bridge” programs; for example, someone with a Bachelor of Science in any field could enter the NP program, becoming an RN in one year and an NP in the second.

As far as “distance learning,” offering graduate degrees in a health profession to remote students dates back to at least the early 1990s, when the University of Pennsylvania offered a videoconference-based master’s in nurse-midwifery. Since then, of course, technology has advanced to a level that allows individuals to view videos and “conference” online via personal electronic devices of one kind or another—a vast improvement on the expensive and inflexible room-scale video presentations of 20 years ago.

As these technologic limitations have fallen by the wayside and alterations to our educational structure have become more feasible, more colleges and universities are exploring their options. The PA programs at the University of North Dakota and the University of Wisconsin–Madison have experimented with blended online learning environments. My own university has an interest in moving to ever-higher levels of distant interaction.

Major criticism of distance education includes the perception that it is a “watered-down” version of the “real thing.” There is also concern that educational institutions might be motivated purely by money, if the sole impetus for distance learning is to significantly increase enrollment. And some critics, while not opposed to online courses per se, do not want an NP or PA seeing patients if his/her degree was earned online—not even in part!

Perhaps the larger issue we’re struggling with is that a new paradigm of teaching is emerging: We are moving away from the traditional Socratic method to more interactive modalities, such as flipped classrooms (settings in which students collaborate via online discussion). Synchronous classes can be delivered seminar-style, with each student able to hear the others and instructors able to share content and even give control of a class to a student for questions or presentations. Asynchronous courses offer opportunities for students to study on their own time and at their own pace. Many suggest that more comprehensive learning, including the development of critical thinking skills, occurs in programs of this design than in traditional education programs.4

I think there is little argument that the educational content (didactics) of a program can be successfully delivered through a nonresidential venue. The concern, rightly so, in health professional education is how to adequately deliver the practical and cocurricular experiences at a distance. Some of us may have a difficult time understanding how this new method of teaching can create the kind of clinicians that are needed, particularly in the relatively short period in which PAs and NPs are prepared for their roles.

Proponents insist that these programs can be successful, as long as they are accredited by the appropriate agency and demonstrate high educational standards (comparable to traditional programs). Programs also need to provide clinical experiences in which the students observe and actually work with patients in order to develop skills in the art of history taking and physical examination, establishment of a differential diagnosis, creation of a plan of action, and appropriate decision-making with regard to available tests and treatment options. Advocates of distance learning also agree that students must be observed by peer clinicians who can confirm that they are ethical and competent to practice, have good bedside manners, and demonstrate respect for the profession and for life.

And who knows? Distance learning may create opportunities to improve access to care in remote, rural, and underserved areas, as these could become fertile training grounds for NPs and PAs (a return to our roots, in a sense). In this age of successful telemedicine, why shouldn’t “tele-education” be the next success story? Although the jury is still out on this concept, the proverbial cat has already been let out of the bag! Only time will tell what results we will see. But I think with the significant enhancement of technology, and participation of committed educators who are willing to step into the arena to ensure that competency-based education persists, we will be pleasantly surprised by the success of this venture.

I would be interested in your views. Please email me at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Monir M. Yale to offer full-time master’s program online. USA Today. www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2015/03/12/yale-full-time-online-masters-program/70163994. Accessed May 2, 2015.

2. Kushniruk AW. Advances in health education applying e-learning, simulations and distance technologies [editorial]. Knowledge Manage E-Learning Int J. 2011;3(1):1-4.

3. Robley LR, Farnsworth BJ, Flynn JB, Horne CD. This new house: building knowledge through online learning. J Prof Nurs. 2004;20(5):333-343.

4. Yang YTC, Chou HA. Beyond critical thinking skills: investigating the relationship between critical thinking skills and dispositions through different online instructional strategies. Br J Educ Technol. 2008;39(4):666-684.

I consider my role as an editorialist to be to inform, persuade, or—sometimes—just comment on current issues that affect PAs and NPs. There have been many opportunities in recent years to address “hot” topics, and this is certainly one of them: the rise of distance entry-level education for health professions students.

The catalyst for this discussion? Earlier this year, Yale University announced it was launching an online entry-level PA program.1 Within minutes of that announcement, there was a conflagration of criticism from the profession, alumni, and the general public. Most of the backlash centered on concerns about adequate delivery of such intense content—including how to instill or enhance professional behaviors and attitudes, or teach hands-on procedures, objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs), and physical exam techniques—from a distance.

In our professions, we tend to be fairly conservative when it comes to change—particularly in terms of innovations in our education programs. But as e-learning, simulations, and distance education modalities become ever more prevalent across the spectrum of higher learning, we require an improved understanding of how these methods will transform entry-level education for health care providers.

Until recently, there has been minimal data on the impact of these technologic advances and teaching methods in health professions education, although this is changing.2 We do have a research gap when it comes to the effect of learning style on NP and PA students’ perceptions of online instruction (despite the rapidly increasing use of it). We also have not firmly established how this delivery method affects professional development (ie, how effectively it prepares clinicians to provide care to patients). None of this has prevented the proliferation of these concepts.

While many were stunned by the Yale venture, it should be noted that the idea is not new. Rather, such programs have steadily become part of health professions education (particularly nursing) in recent years.3 Yale itself was an early adopter of “bridge” programs; for example, someone with a Bachelor of Science in any field could enter the NP program, becoming an RN in one year and an NP in the second.

As far as “distance learning,” offering graduate degrees in a health profession to remote students dates back to at least the early 1990s, when the University of Pennsylvania offered a videoconference-based master’s in nurse-midwifery. Since then, of course, technology has advanced to a level that allows individuals to view videos and “conference” online via personal electronic devices of one kind or another—a vast improvement on the expensive and inflexible room-scale video presentations of 20 years ago.

As these technologic limitations have fallen by the wayside and alterations to our educational structure have become more feasible, more colleges and universities are exploring their options. The PA programs at the University of North Dakota and the University of Wisconsin–Madison have experimented with blended online learning environments. My own university has an interest in moving to ever-higher levels of distant interaction.

Major criticism of distance education includes the perception that it is a “watered-down” version of the “real thing.” There is also concern that educational institutions might be motivated purely by money, if the sole impetus for distance learning is to significantly increase enrollment. And some critics, while not opposed to online courses per se, do not want an NP or PA seeing patients if his/her degree was earned online—not even in part!

Perhaps the larger issue we’re struggling with is that a new paradigm of teaching is emerging: We are moving away from the traditional Socratic method to more interactive modalities, such as flipped classrooms (settings in which students collaborate via online discussion). Synchronous classes can be delivered seminar-style, with each student able to hear the others and instructors able to share content and even give control of a class to a student for questions or presentations. Asynchronous courses offer opportunities for students to study on their own time and at their own pace. Many suggest that more comprehensive learning, including the development of critical thinking skills, occurs in programs of this design than in traditional education programs.4

I think there is little argument that the educational content (didactics) of a program can be successfully delivered through a nonresidential venue. The concern, rightly so, in health professional education is how to adequately deliver the practical and cocurricular experiences at a distance. Some of us may have a difficult time understanding how this new method of teaching can create the kind of clinicians that are needed, particularly in the relatively short period in which PAs and NPs are prepared for their roles.

Proponents insist that these programs can be successful, as long as they are accredited by the appropriate agency and demonstrate high educational standards (comparable to traditional programs). Programs also need to provide clinical experiences in which the students observe and actually work with patients in order to develop skills in the art of history taking and physical examination, establishment of a differential diagnosis, creation of a plan of action, and appropriate decision-making with regard to available tests and treatment options. Advocates of distance learning also agree that students must be observed by peer clinicians who can confirm that they are ethical and competent to practice, have good bedside manners, and demonstrate respect for the profession and for life.

And who knows? Distance learning may create opportunities to improve access to care in remote, rural, and underserved areas, as these could become fertile training grounds for NPs and PAs (a return to our roots, in a sense). In this age of successful telemedicine, why shouldn’t “tele-education” be the next success story? Although the jury is still out on this concept, the proverbial cat has already been let out of the bag! Only time will tell what results we will see. But I think with the significant enhancement of technology, and participation of committed educators who are willing to step into the arena to ensure that competency-based education persists, we will be pleasantly surprised by the success of this venture.

I would be interested in your views. Please email me at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Monir M. Yale to offer full-time master’s program online. USA Today. www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2015/03/12/yale-full-time-online-masters-program/70163994. Accessed May 2, 2015.

2. Kushniruk AW. Advances in health education applying e-learning, simulations and distance technologies [editorial]. Knowledge Manage E-Learning Int J. 2011;3(1):1-4.

3. Robley LR, Farnsworth BJ, Flynn JB, Horne CD. This new house: building knowledge through online learning. J Prof Nurs. 2004;20(5):333-343.

4. Yang YTC, Chou HA. Beyond critical thinking skills: investigating the relationship between critical thinking skills and dispositions through different online instructional strategies. Br J Educ Technol. 2008;39(4):666-684.

I consider my role as an editorialist to be to inform, persuade, or—sometimes—just comment on current issues that affect PAs and NPs. There have been many opportunities in recent years to address “hot” topics, and this is certainly one of them: the rise of distance entry-level education for health professions students.

The catalyst for this discussion? Earlier this year, Yale University announced it was launching an online entry-level PA program.1 Within minutes of that announcement, there was a conflagration of criticism from the profession, alumni, and the general public. Most of the backlash centered on concerns about adequate delivery of such intense content—including how to instill or enhance professional behaviors and attitudes, or teach hands-on procedures, objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs), and physical exam techniques—from a distance.

In our professions, we tend to be fairly conservative when it comes to change—particularly in terms of innovations in our education programs. But as e-learning, simulations, and distance education modalities become ever more prevalent across the spectrum of higher learning, we require an improved understanding of how these methods will transform entry-level education for health care providers.

Until recently, there has been minimal data on the impact of these technologic advances and teaching methods in health professions education, although this is changing.2 We do have a research gap when it comes to the effect of learning style on NP and PA students’ perceptions of online instruction (despite the rapidly increasing use of it). We also have not firmly established how this delivery method affects professional development (ie, how effectively it prepares clinicians to provide care to patients). None of this has prevented the proliferation of these concepts.

While many were stunned by the Yale venture, it should be noted that the idea is not new. Rather, such programs have steadily become part of health professions education (particularly nursing) in recent years.3 Yale itself was an early adopter of “bridge” programs; for example, someone with a Bachelor of Science in any field could enter the NP program, becoming an RN in one year and an NP in the second.

As far as “distance learning,” offering graduate degrees in a health profession to remote students dates back to at least the early 1990s, when the University of Pennsylvania offered a videoconference-based master’s in nurse-midwifery. Since then, of course, technology has advanced to a level that allows individuals to view videos and “conference” online via personal electronic devices of one kind or another—a vast improvement on the expensive and inflexible room-scale video presentations of 20 years ago.

As these technologic limitations have fallen by the wayside and alterations to our educational structure have become more feasible, more colleges and universities are exploring their options. The PA programs at the University of North Dakota and the University of Wisconsin–Madison have experimented with blended online learning environments. My own university has an interest in moving to ever-higher levels of distant interaction.

Major criticism of distance education includes the perception that it is a “watered-down” version of the “real thing.” There is also concern that educational institutions might be motivated purely by money, if the sole impetus for distance learning is to significantly increase enrollment. And some critics, while not opposed to online courses per se, do not want an NP or PA seeing patients if his/her degree was earned online—not even in part!

Perhaps the larger issue we’re struggling with is that a new paradigm of teaching is emerging: We are moving away from the traditional Socratic method to more interactive modalities, such as flipped classrooms (settings in which students collaborate via online discussion). Synchronous classes can be delivered seminar-style, with each student able to hear the others and instructors able to share content and even give control of a class to a student for questions or presentations. Asynchronous courses offer opportunities for students to study on their own time and at their own pace. Many suggest that more comprehensive learning, including the development of critical thinking skills, occurs in programs of this design than in traditional education programs.4

I think there is little argument that the educational content (didactics) of a program can be successfully delivered through a nonresidential venue. The concern, rightly so, in health professional education is how to adequately deliver the practical and cocurricular experiences at a distance. Some of us may have a difficult time understanding how this new method of teaching can create the kind of clinicians that are needed, particularly in the relatively short period in which PAs and NPs are prepared for their roles.

Proponents insist that these programs can be successful, as long as they are accredited by the appropriate agency and demonstrate high educational standards (comparable to traditional programs). Programs also need to provide clinical experiences in which the students observe and actually work with patients in order to develop skills in the art of history taking and physical examination, establishment of a differential diagnosis, creation of a plan of action, and appropriate decision-making with regard to available tests and treatment options. Advocates of distance learning also agree that students must be observed by peer clinicians who can confirm that they are ethical and competent to practice, have good bedside manners, and demonstrate respect for the profession and for life.

And who knows? Distance learning may create opportunities to improve access to care in remote, rural, and underserved areas, as these could become fertile training grounds for NPs and PAs (a return to our roots, in a sense). In this age of successful telemedicine, why shouldn’t “tele-education” be the next success story? Although the jury is still out on this concept, the proverbial cat has already been let out of the bag! Only time will tell what results we will see. But I think with the significant enhancement of technology, and participation of committed educators who are willing to step into the arena to ensure that competency-based education persists, we will be pleasantly surprised by the success of this venture.

I would be interested in your views. Please email me at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Monir M. Yale to offer full-time master’s program online. USA Today. www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2015/03/12/yale-full-time-online-masters-program/70163994. Accessed May 2, 2015.

2. Kushniruk AW. Advances in health education applying e-learning, simulations and distance technologies [editorial]. Knowledge Manage E-Learning Int J. 2011;3(1):1-4.

3. Robley LR, Farnsworth BJ, Flynn JB, Horne CD. This new house: building knowledge through online learning. J Prof Nurs. 2004;20(5):333-343.

4. Yang YTC, Chou HA. Beyond critical thinking skills: investigating the relationship between critical thinking skills and dispositions through different online instructional strategies. Br J Educ Technol. 2008;39(4):666-684.

It's All About the Spit!

Remember eighth grade, when you were taught the correlation between pH and saliva? You learned that testing saliva provides information on whether the mouth is an acidic, basic, or neutral environment. But did you ever suspect then that saliva would become a formidable instrument for medical diagnosis, health, and research?

It’s true, friends and colleagues: Spit is the latest, greatest trend in health care! This important physiologic fluid, which contains a highly complex assortment of substances, is rapidly gaining notice as a diagnostic tool. Don’t believe it? Read on!

The oral cavity, according to Dr. Jack Dillenberg, the inaugural dean of the Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health (ASDOH), “is the gateway and window into health in our body. The signs of nutritional deficiencies, general infections, and systemic diseases that affect the entire body may first become apparent in the oral cavity via lesions or other oral problems. Saliva plays a significant role in maintaining oral health and has a strong correlation to tooth decay.”1

Yes, we’ve known for a while that an adequate amount of saliva serves as a pH buffer; when plaque pH drops below 5.5, dental caries can occur. But according to researchers at The Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Salivary Bioscience Research (yes, a research center dedicated to spit!), saliva holds a wealth of data that is easily collected and economically analyzed and may be a key to many mysteries of human biology and genetics, as well as a helpful tool to combat disease. “There’s lots of potential in exploring what’s in saliva,” according to Dr. Doug Granger, the center’s director and a psychoneuroendocrinologist (what a mouthful—pun intended!) at Arizona State University.2

Saliva in the mouth forms a thin film that protects against dental caries, erosion, attrition, abrasion, periodontal diseases, candidiasis, and abrasive mucosal lesions. Studies suggest saliva may be useful in detecting heart disease, acid reflux, and diabetes; it is already being used for rapid HIV testing.3-5 Researchers have also reported encouraging results in the use of saliva for the diagnosis of autoimmune disorders, breast cancer, oral cancers, gum disease, and cardiovascular, endocrine, and infectious diseases.6,7

Is saliva screening the new "blood test"?

So is saliva screening the new “blood test”? Blood testing, performed as an aid to diagnosis, has its drawbacks: Samples are often uncomfortable to obtain, a lab visit may be necessary, and processing takes time. Finding a reasonable alternative would be beneficial, but there are several steps to such a process.

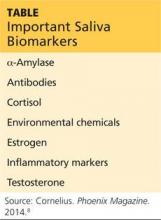

The capacity to monitor health status, disease onset and progression, and treatment outcomes through noninvasive means is a goal in health care promotion and delivery. For this to occur, three things must happen: first, specific biomarkers associated with a health or disease state must be established; second, a noninvasive manner to detect and monitor those biomarkers must be developed; and third, a mechanism to differentiate between the results is needed. Dr. Granger’s team has been studying the possibilities for several years now. Some of the key biomarkers measurable via saliva are listed in the Table below.8

Meanwhile, Dr. Tony Hashemian and colleagues at the ASDOH have developed a diagnostic tool based on pH. The purpose of their pH of Oral Health (pH2OH) initiative is to deliver new technology for pH saliva testing.9 This innovation uses a mobile phone application to capture time-sensitive data and to communicate with a server (in compliance with HIPAA regulations, of course).

Next page: Saliva-testing examination tool >>

A saliva-testing examination tool is used by the dental team to educate patients, inform preventive treatment planning, and assist with proper selection of dental materials to initiate changes in the patient’s oral hygiene. Dental teams measure saliva pH with test strips—the litmus paper we used even as kids in school. It is simply a strip of colored paper that, when soaked in sample saliva, turns a different color depending on the pH level. The color scale ranges from red (indicating a strong acidic state [pH < 3]) to dark blue or purple (indicating a strong alkaline state [pH > 11]).

The free iPhone or Android app developed by Dr. Hashemian’s team is designed to capture the pH value for a patient. The app can manually set the value, or you can take a picture of a test strip and auto-calculate the pH using color-coding analysis. Once set, the app will allow you to save the data and track improvements to oral pH over time.9

With improvements in immunology, microbiology, and biochemistry, salivary testing—in both research and clinical settings—may prove to be an applied and reliable means of recognizing oral signs of systemic illness and exposure to risk factors.10 Salivary diagnostics will be the next great breakthrough in improving the general health of the public. Stay tuned.

What are your thoughts about how “spit” could be applied clinically? Contact me at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Personal communication. February 17, 2015.

2. Walker AK. Researchers eye saliva for patient testing. Baltimore Sun. May 23, 2012.

3. Devi TJ. Saliva: a potential diagnostic tool. J Dental Med Sci. 2014;13(2):52-57.

4. Giannobile WV, Beikler T, Kinney JS, et al. Saliva as a diagnostic tool for periodontal disease: current state and future directions. Periodontol 2000. 2009;50:52-64.

5. Gopinath VK, Arzreanne AR. Saliva as a diagnostic tool for assessment of dental caries. Arch Orofacial Sci. 2006;1:57-59.

6. Streckfus CF, Bigler LR. Salivary glands and saliva: saliva as a diagnostic fluid. Oral Dis. 2002;8:69-76.

7. Lee JM, Garon E, Wong DR. Salivary diagnostics. Orthod Cranioffac Res. 2009;12:206211.

8. Cornelius K. Spit, polished. Phoenix Magazine. November 2014; 38.

9. AT Still University, Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health. pH2OH. www.ph2oh.com/apps/. Accessed March 21, 2015.

10. Lawrence HP. Salivary markers of systemic disease: noninvasive diagnosis of disease and monitoring of general health. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68(3):170-174.

Remember eighth grade, when you were taught the correlation between pH and saliva? You learned that testing saliva provides information on whether the mouth is an acidic, basic, or neutral environment. But did you ever suspect then that saliva would become a formidable instrument for medical diagnosis, health, and research?

It’s true, friends and colleagues: Spit is the latest, greatest trend in health care! This important physiologic fluid, which contains a highly complex assortment of substances, is rapidly gaining notice as a diagnostic tool. Don’t believe it? Read on!

The oral cavity, according to Dr. Jack Dillenberg, the inaugural dean of the Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health (ASDOH), “is the gateway and window into health in our body. The signs of nutritional deficiencies, general infections, and systemic diseases that affect the entire body may first become apparent in the oral cavity via lesions or other oral problems. Saliva plays a significant role in maintaining oral health and has a strong correlation to tooth decay.”1

Yes, we’ve known for a while that an adequate amount of saliva serves as a pH buffer; when plaque pH drops below 5.5, dental caries can occur. But according to researchers at The Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Salivary Bioscience Research (yes, a research center dedicated to spit!), saliva holds a wealth of data that is easily collected and economically analyzed and may be a key to many mysteries of human biology and genetics, as well as a helpful tool to combat disease. “There’s lots of potential in exploring what’s in saliva,” according to Dr. Doug Granger, the center’s director and a psychoneuroendocrinologist (what a mouthful—pun intended!) at Arizona State University.2

Saliva in the mouth forms a thin film that protects against dental caries, erosion, attrition, abrasion, periodontal diseases, candidiasis, and abrasive mucosal lesions. Studies suggest saliva may be useful in detecting heart disease, acid reflux, and diabetes; it is already being used for rapid HIV testing.3-5 Researchers have also reported encouraging results in the use of saliva for the diagnosis of autoimmune disorders, breast cancer, oral cancers, gum disease, and cardiovascular, endocrine, and infectious diseases.6,7

Is saliva screening the new "blood test"?

So is saliva screening the new “blood test”? Blood testing, performed as an aid to diagnosis, has its drawbacks: Samples are often uncomfortable to obtain, a lab visit may be necessary, and processing takes time. Finding a reasonable alternative would be beneficial, but there are several steps to such a process.

The capacity to monitor health status, disease onset and progression, and treatment outcomes through noninvasive means is a goal in health care promotion and delivery. For this to occur, three things must happen: first, specific biomarkers associated with a health or disease state must be established; second, a noninvasive manner to detect and monitor those biomarkers must be developed; and third, a mechanism to differentiate between the results is needed. Dr. Granger’s team has been studying the possibilities for several years now. Some of the key biomarkers measurable via saliva are listed in the Table below.8

Meanwhile, Dr. Tony Hashemian and colleagues at the ASDOH have developed a diagnostic tool based on pH. The purpose of their pH of Oral Health (pH2OH) initiative is to deliver new technology for pH saliva testing.9 This innovation uses a mobile phone application to capture time-sensitive data and to communicate with a server (in compliance with HIPAA regulations, of course).

Next page: Saliva-testing examination tool >>

A saliva-testing examination tool is used by the dental team to educate patients, inform preventive treatment planning, and assist with proper selection of dental materials to initiate changes in the patient’s oral hygiene. Dental teams measure saliva pH with test strips—the litmus paper we used even as kids in school. It is simply a strip of colored paper that, when soaked in sample saliva, turns a different color depending on the pH level. The color scale ranges from red (indicating a strong acidic state [pH < 3]) to dark blue or purple (indicating a strong alkaline state [pH > 11]).

The free iPhone or Android app developed by Dr. Hashemian’s team is designed to capture the pH value for a patient. The app can manually set the value, or you can take a picture of a test strip and auto-calculate the pH using color-coding analysis. Once set, the app will allow you to save the data and track improvements to oral pH over time.9

With improvements in immunology, microbiology, and biochemistry, salivary testing—in both research and clinical settings—may prove to be an applied and reliable means of recognizing oral signs of systemic illness and exposure to risk factors.10 Salivary diagnostics will be the next great breakthrough in improving the general health of the public. Stay tuned.

What are your thoughts about how “spit” could be applied clinically? Contact me at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Personal communication. February 17, 2015.

2. Walker AK. Researchers eye saliva for patient testing. Baltimore Sun. May 23, 2012.

3. Devi TJ. Saliva: a potential diagnostic tool. J Dental Med Sci. 2014;13(2):52-57.

4. Giannobile WV, Beikler T, Kinney JS, et al. Saliva as a diagnostic tool for periodontal disease: current state and future directions. Periodontol 2000. 2009;50:52-64.

5. Gopinath VK, Arzreanne AR. Saliva as a diagnostic tool for assessment of dental caries. Arch Orofacial Sci. 2006;1:57-59.

6. Streckfus CF, Bigler LR. Salivary glands and saliva: saliva as a diagnostic fluid. Oral Dis. 2002;8:69-76.

7. Lee JM, Garon E, Wong DR. Salivary diagnostics. Orthod Cranioffac Res. 2009;12:206211.

8. Cornelius K. Spit, polished. Phoenix Magazine. November 2014; 38.

9. AT Still University, Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health. pH2OH. www.ph2oh.com/apps/. Accessed March 21, 2015.

10. Lawrence HP. Salivary markers of systemic disease: noninvasive diagnosis of disease and monitoring of general health. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68(3):170-174.

Remember eighth grade, when you were taught the correlation between pH and saliva? You learned that testing saliva provides information on whether the mouth is an acidic, basic, or neutral environment. But did you ever suspect then that saliva would become a formidable instrument for medical diagnosis, health, and research?

It’s true, friends and colleagues: Spit is the latest, greatest trend in health care! This important physiologic fluid, which contains a highly complex assortment of substances, is rapidly gaining notice as a diagnostic tool. Don’t believe it? Read on!

The oral cavity, according to Dr. Jack Dillenberg, the inaugural dean of the Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health (ASDOH), “is the gateway and window into health in our body. The signs of nutritional deficiencies, general infections, and systemic diseases that affect the entire body may first become apparent in the oral cavity via lesions or other oral problems. Saliva plays a significant role in maintaining oral health and has a strong correlation to tooth decay.”1

Yes, we’ve known for a while that an adequate amount of saliva serves as a pH buffer; when plaque pH drops below 5.5, dental caries can occur. But according to researchers at The Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Interdisciplinary Salivary Bioscience Research (yes, a research center dedicated to spit!), saliva holds a wealth of data that is easily collected and economically analyzed and may be a key to many mysteries of human biology and genetics, as well as a helpful tool to combat disease. “There’s lots of potential in exploring what’s in saliva,” according to Dr. Doug Granger, the center’s director and a psychoneuroendocrinologist (what a mouthful—pun intended!) at Arizona State University.2

Saliva in the mouth forms a thin film that protects against dental caries, erosion, attrition, abrasion, periodontal diseases, candidiasis, and abrasive mucosal lesions. Studies suggest saliva may be useful in detecting heart disease, acid reflux, and diabetes; it is already being used for rapid HIV testing.3-5 Researchers have also reported encouraging results in the use of saliva for the diagnosis of autoimmune disorders, breast cancer, oral cancers, gum disease, and cardiovascular, endocrine, and infectious diseases.6,7

Is saliva screening the new "blood test"?

So is saliva screening the new “blood test”? Blood testing, performed as an aid to diagnosis, has its drawbacks: Samples are often uncomfortable to obtain, a lab visit may be necessary, and processing takes time. Finding a reasonable alternative would be beneficial, but there are several steps to such a process.

The capacity to monitor health status, disease onset and progression, and treatment outcomes through noninvasive means is a goal in health care promotion and delivery. For this to occur, three things must happen: first, specific biomarkers associated with a health or disease state must be established; second, a noninvasive manner to detect and monitor those biomarkers must be developed; and third, a mechanism to differentiate between the results is needed. Dr. Granger’s team has been studying the possibilities for several years now. Some of the key biomarkers measurable via saliva are listed in the Table below.8

Meanwhile, Dr. Tony Hashemian and colleagues at the ASDOH have developed a diagnostic tool based on pH. The purpose of their pH of Oral Health (pH2OH) initiative is to deliver new technology for pH saliva testing.9 This innovation uses a mobile phone application to capture time-sensitive data and to communicate with a server (in compliance with HIPAA regulations, of course).

Next page: Saliva-testing examination tool >>

A saliva-testing examination tool is used by the dental team to educate patients, inform preventive treatment planning, and assist with proper selection of dental materials to initiate changes in the patient’s oral hygiene. Dental teams measure saliva pH with test strips—the litmus paper we used even as kids in school. It is simply a strip of colored paper that, when soaked in sample saliva, turns a different color depending on the pH level. The color scale ranges from red (indicating a strong acidic state [pH < 3]) to dark blue or purple (indicating a strong alkaline state [pH > 11]).

The free iPhone or Android app developed by Dr. Hashemian’s team is designed to capture the pH value for a patient. The app can manually set the value, or you can take a picture of a test strip and auto-calculate the pH using color-coding analysis. Once set, the app will allow you to save the data and track improvements to oral pH over time.9

With improvements in immunology, microbiology, and biochemistry, salivary testing—in both research and clinical settings—may prove to be an applied and reliable means of recognizing oral signs of systemic illness and exposure to risk factors.10 Salivary diagnostics will be the next great breakthrough in improving the general health of the public. Stay tuned.

What are your thoughts about how “spit” could be applied clinically? Contact me at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Personal communication. February 17, 2015.

2. Walker AK. Researchers eye saliva for patient testing. Baltimore Sun. May 23, 2012.

3. Devi TJ. Saliva: a potential diagnostic tool. J Dental Med Sci. 2014;13(2):52-57.

4. Giannobile WV, Beikler T, Kinney JS, et al. Saliva as a diagnostic tool for periodontal disease: current state and future directions. Periodontol 2000. 2009;50:52-64.

5. Gopinath VK, Arzreanne AR. Saliva as a diagnostic tool for assessment of dental caries. Arch Orofacial Sci. 2006;1:57-59.

6. Streckfus CF, Bigler LR. Salivary glands and saliva: saliva as a diagnostic fluid. Oral Dis. 2002;8:69-76.

7. Lee JM, Garon E, Wong DR. Salivary diagnostics. Orthod Cranioffac Res. 2009;12:206211.

8. Cornelius K. Spit, polished. Phoenix Magazine. November 2014; 38.

9. AT Still University, Arizona School of Dentistry and Oral Health. pH2OH. www.ph2oh.com/apps/. Accessed March 21, 2015.

10. Lawrence HP. Salivary markers of systemic disease: noninvasive diagnosis of disease and monitoring of general health. J Can Dent Assoc. 2002;68(3):170-174.

The Complexities of Competency

Rarely do I post online as a knee-jerk reaction! But recently, a topic hit me right in the middle of the forehead. I received an email from a colleague who asked:

“Is there any study looking at how long a PA or NP needs after completing his/her training to be fully competent? I’m at a hospital board meeting and one member is suggesting ‘midlevels’ need three more years of training, at the expense of the institution hiring them.”

I must admit that I was at a loss as to how to respond! (Not least because I dislike the term midlevel.) Lately, competency has been a hot topic as hospitals and large health care organizations hire more new graduates and want to know how long it will take for them to get up to speed within the institution. Competence is thus defined as how long it takes these PAs/NPs to become fully functional in a particular setting. It’s a narrow, specific question rather than a broad, philosophical one—but it begs the competency question, does it not?

Let’s start with the definition of competency. I had to laugh when I consulted Merriam-Webster, which says competency is “the quality or state of being functionally adequate.” Now, that is what I strive to be … “adequate”!

I prefer Norman’s definition of professional competence: “The habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served. Competence builds on a foundation of basic clinical skills, scientific knowledge, and moral development.”1

He goes on to say that competence has multiple functions: cognitive (using acquired knowledge to solve real-life problems); integrative (using biomedical and psychosocial data in clinical reasoning); relational (communicating effectively with patients and colleagues); and affective/moral (the willingness, patience, and emotional awareness to use these skills judiciously and humanely). I was particularly struck by a final comment that competence is “developmental, impermanent, and context-dependent.”1 Competence is certainly developmental in the context of lifelong learning. If it is indeed impermanent (temporary, transient, transitory, passing, fleeting), then it must be evaluated frequently. There is no argument that it is context-dependent, whether by level of care, specialty knowledge required, or institution.

Clearly, competence is complex. While the PA and NP professions have developed and published clinical competencies in the past decade (which mirror and parallel those of our physician colleagues), how do we actually demonstrate them?

Continue for competency definitions >>

Patricia Benner developed one of the best-known competency definitions in 1982 with her Novice to Expert model, which applied the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition to nursing. It has been widely used as a tool to determine “expertise.”2,3 Her model describes the five levels of expertise as

• Novice: A beginner with little to no experience. Novices face the inability to use discretionary judgment and require significant supervision.

• Advanced beginner: Able to demonstrate marginally acceptable performance based on some real-life experience.

• Competent: Has usually been on the job for two to three years. At this level, the clinician has a sense of mastery and the ability to cope with and manage many aspects of patient care.

• Proficient: Able to grasp clinical solutions quicker and able to hone in on accurate regions of the problem faster.

• Expert: No longer relies on analytics to connect to understanding of the problem but has an intuitive grasp and is able to zero in on all aspects of the problem at hand without any wasteful or unfruitful possibilities.3

Benner maintains that knowledge accrues over time in clinical practice and is developed through dialogue in relationship and situational contexts.4 Of note, clinical experience is not the mere passage of time or longevity within a clinical experience but rather the actual level of clinical interaction. The clinician, therefore, may move forward or backward, depending on the situation.

In 2011, Chuck defined six levels of competency, postulating that for each we find ways to scale the learning curve. It is where we are on the curve that determines our competence in a skill set. His six levels include

• Naïve/Newcomer: Exhibits little observable knowledge, skill, or sincere interest

• Intermediate: Has received minimal but not sufficient training to exhibit a core set of knowledge, skills, or interest

• Proficient: Has completed sufficient training (usually through a set of required classes) to reliably reproduce a core set of knowledge and skills, but requires further training when confronted with situations in which it needs to be applied

• Confident: Has above-average knowledge and skills and demonstrates appropriate confidence in adapting to new situations that challenge those skills

• Master: Demonstrates consistent excellence in knowledge and skills and can appropriately seek affirmation and criticism to independently develop additional skills

• Expert: Has received external validation of superior quality knowledge and skills and is considered an innovator, leader, or authority in a specific area.5

In the Chuck model, levels 1 and 2 would be prematriculants and students. You can see variations of this learning curve in different situations, whether it is a new clinician in the emergency department (ED) or an experienced clinician moving to a new practice.

So when is a clinician (specifically, a PA or NP) fully competent to see patients? This question is undoubtedly being asked more than we realize, and both professions should develop a serious answer to it. Are we doing enough research to make an objective argument in response? No matter how we answer, I think it is important to note that our respective professions have excellent patient care outcomes, even when taking into account the particular clinician level (novice through expert).

This is a challenging topic because what we do requires factual knowledge and the consistent, appropriate application of that knowledge. We know how to measure factual knowledge, more or less, but assuredly we don’t know how to measure the latter (possibly the more important part). In my opinion, we need a pragmatic approach to determine whether a clinician is competent and continues to be so.

One method is to do what is known as a 360 survey. Here’s how it might work: All coworkers of a particular clinician would be surveyed on the perceived elements of clinical competence, including knowledge, application of knowledge, efficiency, ability to make decisions, and attitude toward patients. Every person in the department—say, the ED—could anonymously complete the survey. (This would include nurses, techs, other PAs/NPs, housekeeping, on-call members of the medical staff—literally everybody, although not all of them will be capable of making some of these determinations.) Then the ED director would let the clinician review and discuss the feedback. Everyone in the department would know he or she would be similarly evaluated.6

This is the most brutal, yet fair and efficient, way to assess competency in its broadest sense. Will all opinions be factually substantiated? No! But what better technique do we have, at least for now?

But wait! Perhaps competence is not the end game. Perhaps competence is really a minimum standard. Competence (albeit novice) is measured by completion of the PA or NP curricula (meeting the course objectives) and passage of board/licensure exams, just as, essentially, physician competence is.

Most, if not all, would agree that mastery is achieved by the acquisition of knowledge coupled with sound practice and experience. Mastery or expertise, some say, is what we should focus on, the achievement of which is quite individual. All clinicians can move toward mastery, but not all will actually achieve it. Therefore, how can we mandate a minimum standard, beyond competence, for PAs and NPs but not for other providers?

So, after all the rhetorical ranting about when a PA or NP becomes fully competent, the answer is … It depends! There are too many moving parts. I would suggest that competency is the starting point and mastery (expertise) is a journey.

What do you think? Share your thoughts with me via [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Norman GR. Defining competence: a methodological review. In: Neufeld VR, Norman GR, eds. Assessing Clinical Competence. New York, NY: Springer; 1985:15-35.

2. Gentile DL. Applying the novice-to-expert model to infusion nursing. J Infus Nurs. 2012;35(2):101-107.

3. Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82(3):402-407.

4. Brykczynski KA. Patricia Benner: caring, clinical wisdom, and ethics in nursing practice. In: Alligood MR, ed. Nursing Theorists and Their Work. 8th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2014; 120-146.

5. Chuck E. The competency manifesto: part 3. The Student Doctor Network. www.student doctor.net/2011/04/the-competency-mani festo-part-3. Accessed November 11, 2014.

6. Lepsinger R, Luca AD. The Art and Science of 360-Degree Feedback. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

Rarely do I post online as a knee-jerk reaction! But recently, a topic hit me right in the middle of the forehead. I received an email from a colleague who asked:

“Is there any study looking at how long a PA or NP needs after completing his/her training to be fully competent? I’m at a hospital board meeting and one member is suggesting ‘midlevels’ need three more years of training, at the expense of the institution hiring them.”

I must admit that I was at a loss as to how to respond! (Not least because I dislike the term midlevel.) Lately, competency has been a hot topic as hospitals and large health care organizations hire more new graduates and want to know how long it will take for them to get up to speed within the institution. Competence is thus defined as how long it takes these PAs/NPs to become fully functional in a particular setting. It’s a narrow, specific question rather than a broad, philosophical one—but it begs the competency question, does it not?

Let’s start with the definition of competency. I had to laugh when I consulted Merriam-Webster, which says competency is “the quality or state of being functionally adequate.” Now, that is what I strive to be … “adequate”!

I prefer Norman’s definition of professional competence: “The habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served. Competence builds on a foundation of basic clinical skills, scientific knowledge, and moral development.”1

He goes on to say that competence has multiple functions: cognitive (using acquired knowledge to solve real-life problems); integrative (using biomedical and psychosocial data in clinical reasoning); relational (communicating effectively with patients and colleagues); and affective/moral (the willingness, patience, and emotional awareness to use these skills judiciously and humanely). I was particularly struck by a final comment that competence is “developmental, impermanent, and context-dependent.”1 Competence is certainly developmental in the context of lifelong learning. If it is indeed impermanent (temporary, transient, transitory, passing, fleeting), then it must be evaluated frequently. There is no argument that it is context-dependent, whether by level of care, specialty knowledge required, or institution.

Clearly, competence is complex. While the PA and NP professions have developed and published clinical competencies in the past decade (which mirror and parallel those of our physician colleagues), how do we actually demonstrate them?

Continue for competency definitions >>

Patricia Benner developed one of the best-known competency definitions in 1982 with her Novice to Expert model, which applied the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition to nursing. It has been widely used as a tool to determine “expertise.”2,3 Her model describes the five levels of expertise as

• Novice: A beginner with little to no experience. Novices face the inability to use discretionary judgment and require significant supervision.

• Advanced beginner: Able to demonstrate marginally acceptable performance based on some real-life experience.

• Competent: Has usually been on the job for two to three years. At this level, the clinician has a sense of mastery and the ability to cope with and manage many aspects of patient care.

• Proficient: Able to grasp clinical solutions quicker and able to hone in on accurate regions of the problem faster.

• Expert: No longer relies on analytics to connect to understanding of the problem but has an intuitive grasp and is able to zero in on all aspects of the problem at hand without any wasteful or unfruitful possibilities.3

Benner maintains that knowledge accrues over time in clinical practice and is developed through dialogue in relationship and situational contexts.4 Of note, clinical experience is not the mere passage of time or longevity within a clinical experience but rather the actual level of clinical interaction. The clinician, therefore, may move forward or backward, depending on the situation.

In 2011, Chuck defined six levels of competency, postulating that for each we find ways to scale the learning curve. It is where we are on the curve that determines our competence in a skill set. His six levels include

• Naïve/Newcomer: Exhibits little observable knowledge, skill, or sincere interest

• Intermediate: Has received minimal but not sufficient training to exhibit a core set of knowledge, skills, or interest

• Proficient: Has completed sufficient training (usually through a set of required classes) to reliably reproduce a core set of knowledge and skills, but requires further training when confronted with situations in which it needs to be applied

• Confident: Has above-average knowledge and skills and demonstrates appropriate confidence in adapting to new situations that challenge those skills

• Master: Demonstrates consistent excellence in knowledge and skills and can appropriately seek affirmation and criticism to independently develop additional skills

• Expert: Has received external validation of superior quality knowledge and skills and is considered an innovator, leader, or authority in a specific area.5

In the Chuck model, levels 1 and 2 would be prematriculants and students. You can see variations of this learning curve in different situations, whether it is a new clinician in the emergency department (ED) or an experienced clinician moving to a new practice.

So when is a clinician (specifically, a PA or NP) fully competent to see patients? This question is undoubtedly being asked more than we realize, and both professions should develop a serious answer to it. Are we doing enough research to make an objective argument in response? No matter how we answer, I think it is important to note that our respective professions have excellent patient care outcomes, even when taking into account the particular clinician level (novice through expert).

This is a challenging topic because what we do requires factual knowledge and the consistent, appropriate application of that knowledge. We know how to measure factual knowledge, more or less, but assuredly we don’t know how to measure the latter (possibly the more important part). In my opinion, we need a pragmatic approach to determine whether a clinician is competent and continues to be so.

One method is to do what is known as a 360 survey. Here’s how it might work: All coworkers of a particular clinician would be surveyed on the perceived elements of clinical competence, including knowledge, application of knowledge, efficiency, ability to make decisions, and attitude toward patients. Every person in the department—say, the ED—could anonymously complete the survey. (This would include nurses, techs, other PAs/NPs, housekeeping, on-call members of the medical staff—literally everybody, although not all of them will be capable of making some of these determinations.) Then the ED director would let the clinician review and discuss the feedback. Everyone in the department would know he or she would be similarly evaluated.6

This is the most brutal, yet fair and efficient, way to assess competency in its broadest sense. Will all opinions be factually substantiated? No! But what better technique do we have, at least for now?

But wait! Perhaps competence is not the end game. Perhaps competence is really a minimum standard. Competence (albeit novice) is measured by completion of the PA or NP curricula (meeting the course objectives) and passage of board/licensure exams, just as, essentially, physician competence is.

Most, if not all, would agree that mastery is achieved by the acquisition of knowledge coupled with sound practice and experience. Mastery or expertise, some say, is what we should focus on, the achievement of which is quite individual. All clinicians can move toward mastery, but not all will actually achieve it. Therefore, how can we mandate a minimum standard, beyond competence, for PAs and NPs but not for other providers?

So, after all the rhetorical ranting about when a PA or NP becomes fully competent, the answer is … It depends! There are too many moving parts. I would suggest that competency is the starting point and mastery (expertise) is a journey.

What do you think? Share your thoughts with me via [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Norman GR. Defining competence: a methodological review. In: Neufeld VR, Norman GR, eds. Assessing Clinical Competence. New York, NY: Springer; 1985:15-35.

2. Gentile DL. Applying the novice-to-expert model to infusion nursing. J Infus Nurs. 2012;35(2):101-107.

3. Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82(3):402-407.

4. Brykczynski KA. Patricia Benner: caring, clinical wisdom, and ethics in nursing practice. In: Alligood MR, ed. Nursing Theorists and Their Work. 8th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2014; 120-146.

5. Chuck E. The competency manifesto: part 3. The Student Doctor Network. www.student doctor.net/2011/04/the-competency-mani festo-part-3. Accessed November 11, 2014.

6. Lepsinger R, Luca AD. The Art and Science of 360-Degree Feedback. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

Rarely do I post online as a knee-jerk reaction! But recently, a topic hit me right in the middle of the forehead. I received an email from a colleague who asked:

“Is there any study looking at how long a PA or NP needs after completing his/her training to be fully competent? I’m at a hospital board meeting and one member is suggesting ‘midlevels’ need three more years of training, at the expense of the institution hiring them.”

I must admit that I was at a loss as to how to respond! (Not least because I dislike the term midlevel.) Lately, competency has been a hot topic as hospitals and large health care organizations hire more new graduates and want to know how long it will take for them to get up to speed within the institution. Competence is thus defined as how long it takes these PAs/NPs to become fully functional in a particular setting. It’s a narrow, specific question rather than a broad, philosophical one—but it begs the competency question, does it not?

Let’s start with the definition of competency. I had to laugh when I consulted Merriam-Webster, which says competency is “the quality or state of being functionally adequate.” Now, that is what I strive to be … “adequate”!

I prefer Norman’s definition of professional competence: “The habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values, and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served. Competence builds on a foundation of basic clinical skills, scientific knowledge, and moral development.”1

He goes on to say that competence has multiple functions: cognitive (using acquired knowledge to solve real-life problems); integrative (using biomedical and psychosocial data in clinical reasoning); relational (communicating effectively with patients and colleagues); and affective/moral (the willingness, patience, and emotional awareness to use these skills judiciously and humanely). I was particularly struck by a final comment that competence is “developmental, impermanent, and context-dependent.”1 Competence is certainly developmental in the context of lifelong learning. If it is indeed impermanent (temporary, transient, transitory, passing, fleeting), then it must be evaluated frequently. There is no argument that it is context-dependent, whether by level of care, specialty knowledge required, or institution.

Clearly, competence is complex. While the PA and NP professions have developed and published clinical competencies in the past decade (which mirror and parallel those of our physician colleagues), how do we actually demonstrate them?

Continue for competency definitions >>

Patricia Benner developed one of the best-known competency definitions in 1982 with her Novice to Expert model, which applied the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition to nursing. It has been widely used as a tool to determine “expertise.”2,3 Her model describes the five levels of expertise as

• Novice: A beginner with little to no experience. Novices face the inability to use discretionary judgment and require significant supervision.

• Advanced beginner: Able to demonstrate marginally acceptable performance based on some real-life experience.

• Competent: Has usually been on the job for two to three years. At this level, the clinician has a sense of mastery and the ability to cope with and manage many aspects of patient care.

• Proficient: Able to grasp clinical solutions quicker and able to hone in on accurate regions of the problem faster.

• Expert: No longer relies on analytics to connect to understanding of the problem but has an intuitive grasp and is able to zero in on all aspects of the problem at hand without any wasteful or unfruitful possibilities.3

Benner maintains that knowledge accrues over time in clinical practice and is developed through dialogue in relationship and situational contexts.4 Of note, clinical experience is not the mere passage of time or longevity within a clinical experience but rather the actual level of clinical interaction. The clinician, therefore, may move forward or backward, depending on the situation.

In 2011, Chuck defined six levels of competency, postulating that for each we find ways to scale the learning curve. It is where we are on the curve that determines our competence in a skill set. His six levels include

• Naïve/Newcomer: Exhibits little observable knowledge, skill, or sincere interest

• Intermediate: Has received minimal but not sufficient training to exhibit a core set of knowledge, skills, or interest

• Proficient: Has completed sufficient training (usually through a set of required classes) to reliably reproduce a core set of knowledge and skills, but requires further training when confronted with situations in which it needs to be applied

• Confident: Has above-average knowledge and skills and demonstrates appropriate confidence in adapting to new situations that challenge those skills

• Master: Demonstrates consistent excellence in knowledge and skills and can appropriately seek affirmation and criticism to independently develop additional skills

• Expert: Has received external validation of superior quality knowledge and skills and is considered an innovator, leader, or authority in a specific area.5

In the Chuck model, levels 1 and 2 would be prematriculants and students. You can see variations of this learning curve in different situations, whether it is a new clinician in the emergency department (ED) or an experienced clinician moving to a new practice.

So when is a clinician (specifically, a PA or NP) fully competent to see patients? This question is undoubtedly being asked more than we realize, and both professions should develop a serious answer to it. Are we doing enough research to make an objective argument in response? No matter how we answer, I think it is important to note that our respective professions have excellent patient care outcomes, even when taking into account the particular clinician level (novice through expert).

This is a challenging topic because what we do requires factual knowledge and the consistent, appropriate application of that knowledge. We know how to measure factual knowledge, more or less, but assuredly we don’t know how to measure the latter (possibly the more important part). In my opinion, we need a pragmatic approach to determine whether a clinician is competent and continues to be so.

One method is to do what is known as a 360 survey. Here’s how it might work: All coworkers of a particular clinician would be surveyed on the perceived elements of clinical competence, including knowledge, application of knowledge, efficiency, ability to make decisions, and attitude toward patients. Every person in the department—say, the ED—could anonymously complete the survey. (This would include nurses, techs, other PAs/NPs, housekeeping, on-call members of the medical staff—literally everybody, although not all of them will be capable of making some of these determinations.) Then the ED director would let the clinician review and discuss the feedback. Everyone in the department would know he or she would be similarly evaluated.6

This is the most brutal, yet fair and efficient, way to assess competency in its broadest sense. Will all opinions be factually substantiated? No! But what better technique do we have, at least for now?

But wait! Perhaps competence is not the end game. Perhaps competence is really a minimum standard. Competence (albeit novice) is measured by completion of the PA or NP curricula (meeting the course objectives) and passage of board/licensure exams, just as, essentially, physician competence is.

Most, if not all, would agree that mastery is achieved by the acquisition of knowledge coupled with sound practice and experience. Mastery or expertise, some say, is what we should focus on, the achievement of which is quite individual. All clinicians can move toward mastery, but not all will actually achieve it. Therefore, how can we mandate a minimum standard, beyond competence, for PAs and NPs but not for other providers?

So, after all the rhetorical ranting about when a PA or NP becomes fully competent, the answer is … It depends! There are too many moving parts. I would suggest that competency is the starting point and mastery (expertise) is a journey.

What do you think? Share your thoughts with me via [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Norman GR. Defining competence: a methodological review. In: Neufeld VR, Norman GR, eds. Assessing Clinical Competence. New York, NY: Springer; 1985:15-35.

2. Gentile DL. Applying the novice-to-expert model to infusion nursing. J Infus Nurs. 2012;35(2):101-107.

3. Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs. 1982;82(3):402-407.

4. Brykczynski KA. Patricia Benner: caring, clinical wisdom, and ethics in nursing practice. In: Alligood MR, ed. Nursing Theorists and Their Work. 8th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2014; 120-146.

5. Chuck E. The competency manifesto: part 3. The Student Doctor Network. www.student doctor.net/2011/04/the-competency-mani festo-part-3. Accessed November 11, 2014.

6. Lepsinger R, Luca AD. The Art and Science of 360-Degree Feedback. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2009.

I’ve Been Framed!

Making a correct diagnosis is the central cognitive endeavor of every clinician, since an accurate diagnosis usually leads to appropriate treatment. As PAs and NPs, we dread missing a diagnosis: jaw pain that turns out to be angina or back pain that ends up being an aortic aneurysm. And then of course, there are preventable infections and medication errors.

Several studies in the medical literature indicate that misdiagnosis occurs in 15% to 20% of all cases; in half of these, the patient is harmed. The vast majority of misdiagnoses, about 80%, are due to cognitive errors—in other words, errors in thinking!

This was recently brought home to me through an online course required by my malpractice insurance carrier. The focus was cognitive errors in diagnosis. Prior to starting, I expected it to be a no brainer. After all, every clinician knows what malpractice entails and how best to avoid it, right? We have attended CME courses and read plenty of articles on the topic.

Well, this course was different and had a rather sobering effect on me. As a result, I started to ponder the process we go through to establish a diagnosis.

For the most part, formulating a diagnosis is largely subconscious, and our ability to do it increases with experience.1 The normative model is Bayes’ theorem, an application of conditional probabilities. Clinicians use information on the prevalence of various clinical features in different disease entities to determine the probability that a particular condition is present. The theorem is considered a milestone in logical reasoning and a conquest of statistical inference, although it is still treated with suspicion by most clinicians.

What makes this method potentially impractical is the complexity of the calculations and the fact that not all required information may be readily available. Would you agree that it is impossible to search for and consider all required information or evaluate all possible hypotheses? Therefore, the search for the correct clinical diagnosis is limited to satisfactory explanations within the constraints of the clinical environment.2

Another model for clinical diagnosis is the hypothetico-deductive model. Clinicians achieve a diagnosis by generating multiple competing hypotheses from initial patient cues and collecting data to confirm or refute each. This model has been validated through empirical studies.3 Most clinicians, in my experience, use a combination of intuitive, reflective, and analytical problem solving, with some approaches given more emphasis than others.

On the next page: Categories of diagnostic errors >>

According to Graber et al4, diagnostic errors fall into three categories:

“No-Fault” Errors: The illness is silent, masked, or unusual in its presentation, or the patient misrepresents symptoms.

System-Related: This includes erroneous information in the patient record, technical and/or equipment failures, incorrect test results, poor coordination, and organizational flaws.

Cognitive: Herein lies faulty data collection, interpretation/reasoning, or incomplete knowledge on the part of the clinician. The information necessary to draw the right conclusion is available, or easily found, but the wrong conclusion is reached.4

What really intrigued me is the cognitive framing effect. This is when the diagnosis is unduly influenced by collateral information. There is considerable evidence that we make irrational or biased decisions based on how the expected outcome is framed.

Shortly after taking the malpractice course, I was working in an allergy and asthma practice and had an immunotherapy patient on my schedule who was listed as “same day/sick.” I entered the room thinking her symptoms could be related to her allergic rhinitis or extrinsic asthma or perhaps an adverse reaction to that week’s allergy shot. What I found was a 38-year-old woman with a three-day history of a 103°F fever, severe neck pain, headache, and severe malaise. Sparing all other information, suffice it to say she was sent directly to the emergency department (ED), where she was admitted.

I am also aware of a case in which a patient with shortness of breath was treated in an ED with an erroneous diagnosis of COPD with a “long-standing benign murmur.” She was in a room with nebulizers on the nightstand and a diagnosis of “COPD exacerbation” and later died of aortic stenosis. Sometimes, inaccurate prior information or collateral evidence frames a problem as pulmonary when it is really cardiac.

Essentially, clinicians may be influenced by the way in which the problem is framed. For example, perceptions of risk to the patient may be influenced by the possible outcome (eg, is the patient likely to die?), the type of clinic, or even the time of day.5 Framing may also occur when another clinician presents a case to you that is influenced by his or her own bias.

On the next page: How to avoid framing bias >>

There are some remedies to avoid framing bias:

• Acknowledge that framing bias may exist, and be on the lookout for it.

• Improve your knowledge and experience through use of simulations, improved feedback on decision outcomes, and focused CME on known pitfalls in specific diseases/scenarios.

• Improve your clinical reasoning through reflective practices. Slow down (easy for me to say) and think. Perform a metacognitive review, and recognize the traps associated with relying on rules-of-thumb.

• Provide cognitive help through technological support and algorithms (eg, through electronic medical record prompts), and ensure access to second opinions from colleagues.

• Reduce the “cognitive load” by modifying work schedules and the number of patients to be seen. Reduce distractions and interruptions in the work environment.6

With the time constraints and frenzied nature of modern health care, there is, I believe, value in stopping to reflect on our thinking, particularly when an original presumption about a diagnosis appears not to succeed in explaining the complaint or empiric therapy does not improve the patient’s symptoms. At these times, drawing on both intuitive and deliberative thinking can be fundamental in avoiding thought traps and moving us onto a better diagnostic path.

I have not meant to oversimplify an obviously complex topic, but I would love to hear from you on your opinion about this topic. Contact me at [email protected].

REFERENCES

1. Nkanginieme KEO. Clinical diagnosis as

a dynamic cognitive process: application

of Bloom’s taxonomy for educational objectives in the cognitive domain. Med Educ Online [serial online]. 1997;2:1. www.msu.edu/~dsolomon/f0000007.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2014.

2. Phua DH, Tan NC. Cognitive aspect of diagnostic errors. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2013; 42(1):33-41.

3. Charlin B, Tardif J, Boshuizen HP. Scripts and medical diagnostic knowledge: theory and applications for clinical reasoning instruction and research. Acad Med. 2000;75(2):182-190.

4. Graber ML, Franklin N, Gordoin R. Diagnostic error in internal medicine. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(13):1493-1499.

5. Croskerry P. The importance of cognitive errors in diagnosis and strategies to minimize them. Acad Med. 2003;78(8):775-780.

6. Perkocha L. Cognitive error in medical diagnosis: what we now know. Presented at University of Hawaii John A Burns School of Medicine Reunion, July 27, 2013. https://jabsom.hawaii.edu/JABSOM/departments/CME/doc/Perkocha.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2014. 5, 2014.

Making a correct diagnosis is the central cognitive endeavor of every clinician, since an accurate diagnosis usually leads to appropriate treatment. As PAs and NPs, we dread missing a diagnosis: jaw pain that turns out to be angina or back pain that ends up being an aortic aneurysm. And then of course, there are preventable infections and medication errors.

Several studies in the medical literature indicate that misdiagnosis occurs in 15% to 20% of all cases; in half of these, the patient is harmed. The vast majority of misdiagnoses, about 80%, are due to cognitive errors—in other words, errors in thinking!

This was recently brought home to me through an online course required by my malpractice insurance carrier. The focus was cognitive errors in diagnosis. Prior to starting, I expected it to be a no brainer. After all, every clinician knows what malpractice entails and how best to avoid it, right? We have attended CME courses and read plenty of articles on the topic.

Well, this course was different and had a rather sobering effect on me. As a result, I started to ponder the process we go through to establish a diagnosis.

For the most part, formulating a diagnosis is largely subconscious, and our ability to do it increases with experience.1 The normative model is Bayes’ theorem, an application of conditional probabilities. Clinicians use information on the prevalence of various clinical features in different disease entities to determine the probability that a particular condition is present. The theorem is considered a milestone in logical reasoning and a conquest of statistical inference, although it is still treated with suspicion by most clinicians.

What makes this method potentially impractical is the complexity of the calculations and the fact that not all required information may be readily available. Would you agree that it is impossible to search for and consider all required information or evaluate all possible hypotheses? Therefore, the search for the correct clinical diagnosis is limited to satisfactory explanations within the constraints of the clinical environment.2

Another model for clinical diagnosis is the hypothetico-deductive model. Clinicians achieve a diagnosis by generating multiple competing hypotheses from initial patient cues and collecting data to confirm or refute each. This model has been validated through empirical studies.3 Most clinicians, in my experience, use a combination of intuitive, reflective, and analytical problem solving, with some approaches given more emphasis than others.

On the next page: Categories of diagnostic errors >>

According to Graber et al4, diagnostic errors fall into three categories:

“No-Fault” Errors: The illness is silent, masked, or unusual in its presentation, or the patient misrepresents symptoms.