User login

Telemedicine

Telepsychiatry: Ready to consider a different kind of practice?

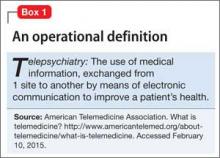

Too few psychiatrists. A growing number of patients. A new federal law, technological advances, and a generational shift in the way people communicate. Add them together and you have the perfect environment for telepsychiatry—the remote practice of psychiatry by means of telemedicine—to take root (Box 1). Although telepsychiatry has, in various forms, been around since the 1950s,1 only recently has it expanded into almost all areas of psychiatric practice.

Here are some observations from my daily work on why I see this method of delivering mental health care is poised to expand in 2015 and beyond. Does telepsychiatry make sense for you?

Lack of supply is a big driver

There are simply not enough psychiatrists where they are needed, which is the primary driver of the expansion of telepsychiatry. With 77% of counties in the United States reporting a shortage of psychiatrists2 and the “graying” of the psychiatric workforce,3 a more efficient way to make use of a psychiatrist’s time is needed. Telepsychiatry eliminates travel time and allows psychiatrists to visit distant sites virtually.

The shortage of psychiatric practitioners that we see today is only going to become worse. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 includes mental health care and substance abuse treatment among its 10 essential benefits; just as important, new rules arising from the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 limit restrictions on access to mental health care when insurance provides such coverage.4 These legislative initiatives likely will lead to increased demand for psychiatrists in all care settings—from outpatient consults to acute inpatient admissions.

Why so attractive an option?

The shortage of psychiatrists creates limitations on access to care. Fortunately, telemedicine has entered a new age, ushered in by widely available teleconferencing technology. Specialists from dermatology to surgery currently are using telemedicine; psychiatry is a good fit for telemedicine because of (1) the limited amount of “touch” required to make a psychiatric assessment, (2) significant improvements in video quality in recent years, and (3) a decrease in the stigma associated with visiting a psychiatrist.

A generation raised on the Internet is entering the health care marketplace. These consumers and clinicians are accustomed to using video for many daily activities, and they seek health information from the Web. Visiting a psychiatrist through teleconferencing isn’t strange or alienating to this generation; their comfort with technology allows them to have intimate exchanges on video.

Subspecialty particulars

The earliest adopters, not surprisingly, are in areas where the strain of shortage has been felt most, with pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatrists leading the way. In these fields, a substantial literature supports the use of telepsychiatry from a number of practice perspectives.

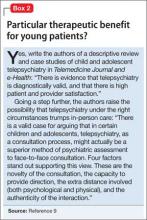

Pediatric psychiatry. The literature shows that children, families, and clinicians are, on the whole, satisfied with telepsychiatry.5 Children and adolescents who have been shown to benefit from telepsychiatry include those with depression,6 posttraumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders.7 Based on a case series, some authors have asserted that telepsychiatry might be preferable to in-person treatment (Box 2).8

Geriatric psychiatry. Research shows that geriatric patients, who are most likely to feel threatened by new technology, accept telepsychiatry visits.9 For psychiatrists treating geriatric patients, telepsychiatry can significantly lower costs by cutting commuting10 and make more accessible for patients whose age makes them unable to drive.

Correctional psychiatry. Clinicians working in correctional psychiatry have been at the forefront of experimentation with telepsychiatry. The technology is a natural fit for this setting:

• Prisons often are located in remote locations.

• Psychiatrists can be reluctant to provide on-site services because of safety concerns.

With correctional telepsychiatry, not only are patient outcomes comparable with in-person psychiatry, but the cost of delivering care can be significantly lower.11 With the U.S. Department of Justice reporting that 50% of inmates have a diagnosable mental disorder, including substance abuse,12 the need for access to a psychiatrist in the correctional system is acute.

Telepsychiatry can confidently be provided in a number of settings:

• emergency rooms

• nursing homes

• offices of primary care physicians

• in-home care.

Clinical services in these settings have been offered, studied, and reviewed.13

Can confidentiality and security be assured?

As with any new medical tool, the risk and benefits must be weighed care fully. The most obvious risk is to privacy. Telepsychiatry visits, like all patient encounters, must be secure and confidential. Given the growing suspicion among the public and professionals who use computers that all data are at risk, clinicians must take appropriate cautions and, at the same time, warn patients of the risks. Readily available videoconferencing software, such as Skype, does not provide the level of security that patients expect from health care providers.14

Other common concerns about telepsychiatry are stable access to videoconferencing and the safety from hackers of necessary hardware. Medical device companies have created hardware and software for use in telepsychiatry that provide a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant high-quality, stable, videoconferencing visit.

Do patients benefit?

Clinically, patients have fared well when they receive care through telepsychiatry. In some studies, however, clinicians have expressed some dissatisfaction with the technology13— understandable, given the value that psychiatry traditionally has put on sitting with the patient. As Knoedler15 described it, making the switch to telepsychiatry from in-person contact can engender loneliness in some physicians; not only is patient contact shifted to videoconferencing, but the psychiatrist loses the supportive environment of a busy clinical practice. Knoedler also pointed out that, on the other hand, telepsychiatry offers practitioners the opportunity to evaluate and treat people who otherwise would not have mental health care.

Obstacles—practical, knotty ones

Reimbursement and licensing. These are 2 pressing problems of telepsychiatry, although recent policy developments will help expand telepsychiatry and make it more appealing to physicians:

• Medicare reimburses for telepsychiatry in non-metropolitan areas.

• In 41 states, Medicaid has included telepsychiatry as a benefit.16

• Nine states offer a specific medical license for practicing telepsychiatry17 (in the remaining states, a full medical license must be obtained before one can provide telemedicine services).

• The Joint Commission has included language in its regulations that could expedite privileging of telepsychiatrists.18

Even with such advancements, problems with licensure, credentialing, privacy, security, confidentiality, informed consent, and professional liability remain.19 I urge you to do your research on these key areas before plunging in.

Changes to models of care. The risk that telepsychiatry poses to various models of care has to be considered. Telepsychiatry is a dramatic innovation, but it should be used to support only high-quality, evidence-based care to which patients are entitled.20 With new technology—as with new medications—use must be carefully monitored and scrutinized.

Although evidence of the value of telepsychiatry is growing, many methods of long-distance practice are still in their infancy. Data must be collected and poor outcomes assessed honestly to ensure that the “more-good-than-harm” mandate is met.

Good reasons to call this shift ‘inevitable’

The future of telepsychiatry includes expansion into new areas of practice. The move to providing services to patients where they happen to be—at work or home— seems inevitable:

• In rural areas, practitioners can communicate with patients so that they are cared for in their homes, without the expense of transportation.

• Employers can invest in workplace health clinics that use telemedicine services to reduce absenteeism.

• For psychiatrists, the ability to provide services to patients across a wide region, from a single convenient location, and at lower cost is an attractive prospect.

To conclude: telepsychiatry holds potential to provide greater reimbursement and improved quality of life for psychiatrists and patients: It allows physicians to choose where they live and work, and limits the number of unreimbursed commutes, and gives patients access to psychiatric care locally, without disruptive travel and delays.

Bottom Line

The exchange of medical information from 1 site to another by means of electronic communication has great potential to improve the health of patients and to alleviate the shortage of psychiatric practitioners across regions and settings. Pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatry stand to benefit because of the nature of the patients and locations.

Related Resources

• American Telemedicine Association. Practice guidelines for video-based online mental health services. http://www. americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/standards/practice-guidelines-for-video-based-online-mental-health-services. pdf?sfvrsn=6. Published May 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

• Freudenberg N, Yellowlees PM. Telepsychiatry as part of a comprehensive care plan. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(12):964-968.

• Kornbluh R. Telepsychiatry is a tool that we must exploit. Clinical Psychiatry News. August 7, 2014. http://www. clinicalpsychiatrynews.com/home/article/telepsychiatry-is-a-tool-that-we-must-exploit/28c87bec298e0aa208309fa 9bc48dedc.html.

• University of Colorado Denver. Telemental Health Guide. http:// www.tmhguide.org.

Disclosure

Dr. Kornbluh reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Shore JH. Telepsychiatry: videoconferencing in the delivery of psychiatric care. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):256-262.

2. Konrad TR, Ellis AR, Thomas KC, et al. County-level estimates of need for mental health professionals in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1307-1314.

3. Vernon DJ, Salsberg E, Erikson C, et al. Planning the future mental health workforce: with progress on coverage, what role will psychiatrists play? Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(3):187-192.

4. Carrns A. Understanding new rules that widen mental health coverage. The New York Times. http://www. nytimes.com/2014/01/10/your-money/understanding-new-rules-that-widen-mental-health-coverage.html. Published January 9, 2014. Accessed February 10, 2015.

5. Myers KM, Valentine JM, Melzer SM. Feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability of telepsychiatry for children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(11):1493-1496.

6. Nelson EL, Barnard M, Cain S. Treating childhood depression over videoconferencing. Telemed J E Health. 2003;9(1):49-55.

7. Boydell KM, Hodgins M, Pignatiello A, et al. Using technology to deliver mental health services to children and youth: a scoping review. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(2):87-99.

8. Pakyurek M, Yellowlees P, Hilty D. The child and adolescent telepsychiatry consultation: can it be a more effective clinical process for certain patients than conventional practice? Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(3):289-292.

9. Poon P, Hui E, Dai D, et al. Cognitive intervention for community-dwelling older persons with memory problems: telemedicine versus face-to-face treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(3):285-286.

10. Rabinowitz T, Murphy KM, Amour JL, et al. Benefits of a telepsychiatry consultation service for rural nursing home residents. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(1):34-40.

11. Deslich SA, Thistlethwaite T, Coustasse A. Telepsychiatry in correctional facilities: using technology to improve access and decrease costs of mental health care in underserved populations. Perm J. 2013;17(3):80-86.

12. James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji. pdf. Updated December 14, 2006. Accessed February 10, 2015.

13. Hilty DN, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, et al. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(6):444-454.

14. Maheu MM, Mcmenamin J. Telepsychiatry: the perils of using skype. Psychiatric Times. http://www. psychiatrictimes.com/blog/telepsychiatry-perils-using-skype. Published March 28, 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

15. Knoedler DW. Telepsychiatry: first week in the trenches. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/ blogs/couch-crisis/telepsychiatry-first-week-trenches. Published January 22, 2014. Accessed February 15, 2015.

16. Secure Telehealth. Medicaid reimburses for telehealth in 41 states. http://www.securetelehealth.com/medicaid-reimbursement.html. Updated January 15, 2015. Accessed February 10, 2015.

17. Federation of State Medical Boards. Telemedicine overview: Board-by-Board approach. http://library.fsmb.org/pdf/ grpol_telemedicine_licensure.pdf. Updated June 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

18. Joint Commission Perspectives. Accepted: final revisions to telemedicine standards. http://www.jointcommission. org/assets/1/6/Revisions_telemedicine_standards.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed February 10, 2015.

19. Hyler SE, Gangure DP. Legal and ethical challenges in telepsychiatry. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(4):272-276.

20. Kornbluh RA. Staying true to the mission: adapting telepsychiatry to a new environment. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(6):482-483.

Too few psychiatrists. A growing number of patients. A new federal law, technological advances, and a generational shift in the way people communicate. Add them together and you have the perfect environment for telepsychiatry—the remote practice of psychiatry by means of telemedicine—to take root (Box 1). Although telepsychiatry has, in various forms, been around since the 1950s,1 only recently has it expanded into almost all areas of psychiatric practice.

Here are some observations from my daily work on why I see this method of delivering mental health care is poised to expand in 2015 and beyond. Does telepsychiatry make sense for you?

Lack of supply is a big driver

There are simply not enough psychiatrists where they are needed, which is the primary driver of the expansion of telepsychiatry. With 77% of counties in the United States reporting a shortage of psychiatrists2 and the “graying” of the psychiatric workforce,3 a more efficient way to make use of a psychiatrist’s time is needed. Telepsychiatry eliminates travel time and allows psychiatrists to visit distant sites virtually.

The shortage of psychiatric practitioners that we see today is only going to become worse. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 includes mental health care and substance abuse treatment among its 10 essential benefits; just as important, new rules arising from the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 limit restrictions on access to mental health care when insurance provides such coverage.4 These legislative initiatives likely will lead to increased demand for psychiatrists in all care settings—from outpatient consults to acute inpatient admissions.

Why so attractive an option?

The shortage of psychiatrists creates limitations on access to care. Fortunately, telemedicine has entered a new age, ushered in by widely available teleconferencing technology. Specialists from dermatology to surgery currently are using telemedicine; psychiatry is a good fit for telemedicine because of (1) the limited amount of “touch” required to make a psychiatric assessment, (2) significant improvements in video quality in recent years, and (3) a decrease in the stigma associated with visiting a psychiatrist.

A generation raised on the Internet is entering the health care marketplace. These consumers and clinicians are accustomed to using video for many daily activities, and they seek health information from the Web. Visiting a psychiatrist through teleconferencing isn’t strange or alienating to this generation; their comfort with technology allows them to have intimate exchanges on video.

Subspecialty particulars

The earliest adopters, not surprisingly, are in areas where the strain of shortage has been felt most, with pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatrists leading the way. In these fields, a substantial literature supports the use of telepsychiatry from a number of practice perspectives.

Pediatric psychiatry. The literature shows that children, families, and clinicians are, on the whole, satisfied with telepsychiatry.5 Children and adolescents who have been shown to benefit from telepsychiatry include those with depression,6 posttraumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders.7 Based on a case series, some authors have asserted that telepsychiatry might be preferable to in-person treatment (Box 2).8

Geriatric psychiatry. Research shows that geriatric patients, who are most likely to feel threatened by new technology, accept telepsychiatry visits.9 For psychiatrists treating geriatric patients, telepsychiatry can significantly lower costs by cutting commuting10 and make more accessible for patients whose age makes them unable to drive.

Correctional psychiatry. Clinicians working in correctional psychiatry have been at the forefront of experimentation with telepsychiatry. The technology is a natural fit for this setting:

• Prisons often are located in remote locations.

• Psychiatrists can be reluctant to provide on-site services because of safety concerns.

With correctional telepsychiatry, not only are patient outcomes comparable with in-person psychiatry, but the cost of delivering care can be significantly lower.11 With the U.S. Department of Justice reporting that 50% of inmates have a diagnosable mental disorder, including substance abuse,12 the need for access to a psychiatrist in the correctional system is acute.

Telepsychiatry can confidently be provided in a number of settings:

• emergency rooms

• nursing homes

• offices of primary care physicians

• in-home care.

Clinical services in these settings have been offered, studied, and reviewed.13

Can confidentiality and security be assured?

As with any new medical tool, the risk and benefits must be weighed care fully. The most obvious risk is to privacy. Telepsychiatry visits, like all patient encounters, must be secure and confidential. Given the growing suspicion among the public and professionals who use computers that all data are at risk, clinicians must take appropriate cautions and, at the same time, warn patients of the risks. Readily available videoconferencing software, such as Skype, does not provide the level of security that patients expect from health care providers.14

Other common concerns about telepsychiatry are stable access to videoconferencing and the safety from hackers of necessary hardware. Medical device companies have created hardware and software for use in telepsychiatry that provide a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant high-quality, stable, videoconferencing visit.

Do patients benefit?

Clinically, patients have fared well when they receive care through telepsychiatry. In some studies, however, clinicians have expressed some dissatisfaction with the technology13— understandable, given the value that psychiatry traditionally has put on sitting with the patient. As Knoedler15 described it, making the switch to telepsychiatry from in-person contact can engender loneliness in some physicians; not only is patient contact shifted to videoconferencing, but the psychiatrist loses the supportive environment of a busy clinical practice. Knoedler also pointed out that, on the other hand, telepsychiatry offers practitioners the opportunity to evaluate and treat people who otherwise would not have mental health care.

Obstacles—practical, knotty ones

Reimbursement and licensing. These are 2 pressing problems of telepsychiatry, although recent policy developments will help expand telepsychiatry and make it more appealing to physicians:

• Medicare reimburses for telepsychiatry in non-metropolitan areas.

• In 41 states, Medicaid has included telepsychiatry as a benefit.16

• Nine states offer a specific medical license for practicing telepsychiatry17 (in the remaining states, a full medical license must be obtained before one can provide telemedicine services).

• The Joint Commission has included language in its regulations that could expedite privileging of telepsychiatrists.18

Even with such advancements, problems with licensure, credentialing, privacy, security, confidentiality, informed consent, and professional liability remain.19 I urge you to do your research on these key areas before plunging in.

Changes to models of care. The risk that telepsychiatry poses to various models of care has to be considered. Telepsychiatry is a dramatic innovation, but it should be used to support only high-quality, evidence-based care to which patients are entitled.20 With new technology—as with new medications—use must be carefully monitored and scrutinized.

Although evidence of the value of telepsychiatry is growing, many methods of long-distance practice are still in their infancy. Data must be collected and poor outcomes assessed honestly to ensure that the “more-good-than-harm” mandate is met.

Good reasons to call this shift ‘inevitable’

The future of telepsychiatry includes expansion into new areas of practice. The move to providing services to patients where they happen to be—at work or home— seems inevitable:

• In rural areas, practitioners can communicate with patients so that they are cared for in their homes, without the expense of transportation.

• Employers can invest in workplace health clinics that use telemedicine services to reduce absenteeism.

• For psychiatrists, the ability to provide services to patients across a wide region, from a single convenient location, and at lower cost is an attractive prospect.

To conclude: telepsychiatry holds potential to provide greater reimbursement and improved quality of life for psychiatrists and patients: It allows physicians to choose where they live and work, and limits the number of unreimbursed commutes, and gives patients access to psychiatric care locally, without disruptive travel and delays.

Bottom Line

The exchange of medical information from 1 site to another by means of electronic communication has great potential to improve the health of patients and to alleviate the shortage of psychiatric practitioners across regions and settings. Pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatry stand to benefit because of the nature of the patients and locations.

Related Resources

• American Telemedicine Association. Practice guidelines for video-based online mental health services. http://www. americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/standards/practice-guidelines-for-video-based-online-mental-health-services. pdf?sfvrsn=6. Published May 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

• Freudenberg N, Yellowlees PM. Telepsychiatry as part of a comprehensive care plan. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(12):964-968.

• Kornbluh R. Telepsychiatry is a tool that we must exploit. Clinical Psychiatry News. August 7, 2014. http://www. clinicalpsychiatrynews.com/home/article/telepsychiatry-is-a-tool-that-we-must-exploit/28c87bec298e0aa208309fa 9bc48dedc.html.

• University of Colorado Denver. Telemental Health Guide. http:// www.tmhguide.org.

Disclosure

Dr. Kornbluh reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Too few psychiatrists. A growing number of patients. A new federal law, technological advances, and a generational shift in the way people communicate. Add them together and you have the perfect environment for telepsychiatry—the remote practice of psychiatry by means of telemedicine—to take root (Box 1). Although telepsychiatry has, in various forms, been around since the 1950s,1 only recently has it expanded into almost all areas of psychiatric practice.

Here are some observations from my daily work on why I see this method of delivering mental health care is poised to expand in 2015 and beyond. Does telepsychiatry make sense for you?

Lack of supply is a big driver

There are simply not enough psychiatrists where they are needed, which is the primary driver of the expansion of telepsychiatry. With 77% of counties in the United States reporting a shortage of psychiatrists2 and the “graying” of the psychiatric workforce,3 a more efficient way to make use of a psychiatrist’s time is needed. Telepsychiatry eliminates travel time and allows psychiatrists to visit distant sites virtually.

The shortage of psychiatric practitioners that we see today is only going to become worse. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 includes mental health care and substance abuse treatment among its 10 essential benefits; just as important, new rules arising from the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 limit restrictions on access to mental health care when insurance provides such coverage.4 These legislative initiatives likely will lead to increased demand for psychiatrists in all care settings—from outpatient consults to acute inpatient admissions.

Why so attractive an option?

The shortage of psychiatrists creates limitations on access to care. Fortunately, telemedicine has entered a new age, ushered in by widely available teleconferencing technology. Specialists from dermatology to surgery currently are using telemedicine; psychiatry is a good fit for telemedicine because of (1) the limited amount of “touch” required to make a psychiatric assessment, (2) significant improvements in video quality in recent years, and (3) a decrease in the stigma associated with visiting a psychiatrist.

A generation raised on the Internet is entering the health care marketplace. These consumers and clinicians are accustomed to using video for many daily activities, and they seek health information from the Web. Visiting a psychiatrist through teleconferencing isn’t strange or alienating to this generation; their comfort with technology allows them to have intimate exchanges on video.

Subspecialty particulars

The earliest adopters, not surprisingly, are in areas where the strain of shortage has been felt most, with pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatrists leading the way. In these fields, a substantial literature supports the use of telepsychiatry from a number of practice perspectives.

Pediatric psychiatry. The literature shows that children, families, and clinicians are, on the whole, satisfied with telepsychiatry.5 Children and adolescents who have been shown to benefit from telepsychiatry include those with depression,6 posttraumatic stress disorder, and eating disorders.7 Based on a case series, some authors have asserted that telepsychiatry might be preferable to in-person treatment (Box 2).8

Geriatric psychiatry. Research shows that geriatric patients, who are most likely to feel threatened by new technology, accept telepsychiatry visits.9 For psychiatrists treating geriatric patients, telepsychiatry can significantly lower costs by cutting commuting10 and make more accessible for patients whose age makes them unable to drive.

Correctional psychiatry. Clinicians working in correctional psychiatry have been at the forefront of experimentation with telepsychiatry. The technology is a natural fit for this setting:

• Prisons often are located in remote locations.

• Psychiatrists can be reluctant to provide on-site services because of safety concerns.

With correctional telepsychiatry, not only are patient outcomes comparable with in-person psychiatry, but the cost of delivering care can be significantly lower.11 With the U.S. Department of Justice reporting that 50% of inmates have a diagnosable mental disorder, including substance abuse,12 the need for access to a psychiatrist in the correctional system is acute.

Telepsychiatry can confidently be provided in a number of settings:

• emergency rooms

• nursing homes

• offices of primary care physicians

• in-home care.

Clinical services in these settings have been offered, studied, and reviewed.13

Can confidentiality and security be assured?

As with any new medical tool, the risk and benefits must be weighed care fully. The most obvious risk is to privacy. Telepsychiatry visits, like all patient encounters, must be secure and confidential. Given the growing suspicion among the public and professionals who use computers that all data are at risk, clinicians must take appropriate cautions and, at the same time, warn patients of the risks. Readily available videoconferencing software, such as Skype, does not provide the level of security that patients expect from health care providers.14

Other common concerns about telepsychiatry are stable access to videoconferencing and the safety from hackers of necessary hardware. Medical device companies have created hardware and software for use in telepsychiatry that provide a Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act-compliant high-quality, stable, videoconferencing visit.

Do patients benefit?

Clinically, patients have fared well when they receive care through telepsychiatry. In some studies, however, clinicians have expressed some dissatisfaction with the technology13— understandable, given the value that psychiatry traditionally has put on sitting with the patient. As Knoedler15 described it, making the switch to telepsychiatry from in-person contact can engender loneliness in some physicians; not only is patient contact shifted to videoconferencing, but the psychiatrist loses the supportive environment of a busy clinical practice. Knoedler also pointed out that, on the other hand, telepsychiatry offers practitioners the opportunity to evaluate and treat people who otherwise would not have mental health care.

Obstacles—practical, knotty ones

Reimbursement and licensing. These are 2 pressing problems of telepsychiatry, although recent policy developments will help expand telepsychiatry and make it more appealing to physicians:

• Medicare reimburses for telepsychiatry in non-metropolitan areas.

• In 41 states, Medicaid has included telepsychiatry as a benefit.16

• Nine states offer a specific medical license for practicing telepsychiatry17 (in the remaining states, a full medical license must be obtained before one can provide telemedicine services).

• The Joint Commission has included language in its regulations that could expedite privileging of telepsychiatrists.18

Even with such advancements, problems with licensure, credentialing, privacy, security, confidentiality, informed consent, and professional liability remain.19 I urge you to do your research on these key areas before plunging in.

Changes to models of care. The risk that telepsychiatry poses to various models of care has to be considered. Telepsychiatry is a dramatic innovation, but it should be used to support only high-quality, evidence-based care to which patients are entitled.20 With new technology—as with new medications—use must be carefully monitored and scrutinized.

Although evidence of the value of telepsychiatry is growing, many methods of long-distance practice are still in their infancy. Data must be collected and poor outcomes assessed honestly to ensure that the “more-good-than-harm” mandate is met.

Good reasons to call this shift ‘inevitable’

The future of telepsychiatry includes expansion into new areas of practice. The move to providing services to patients where they happen to be—at work or home— seems inevitable:

• In rural areas, practitioners can communicate with patients so that they are cared for in their homes, without the expense of transportation.

• Employers can invest in workplace health clinics that use telemedicine services to reduce absenteeism.

• For psychiatrists, the ability to provide services to patients across a wide region, from a single convenient location, and at lower cost is an attractive prospect.

To conclude: telepsychiatry holds potential to provide greater reimbursement and improved quality of life for psychiatrists and patients: It allows physicians to choose where they live and work, and limits the number of unreimbursed commutes, and gives patients access to psychiatric care locally, without disruptive travel and delays.

Bottom Line

The exchange of medical information from 1 site to another by means of electronic communication has great potential to improve the health of patients and to alleviate the shortage of psychiatric practitioners across regions and settings. Pediatric, geriatric, and correctional psychiatry stand to benefit because of the nature of the patients and locations.

Related Resources

• American Telemedicine Association. Practice guidelines for video-based online mental health services. http://www. americantelemed.org/docs/default-source/standards/practice-guidelines-for-video-based-online-mental-health-services. pdf?sfvrsn=6. Published May 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

• Freudenberg N, Yellowlees PM. Telepsychiatry as part of a comprehensive care plan. Virtual Mentor. 2014;16(12):964-968.

• Kornbluh R. Telepsychiatry is a tool that we must exploit. Clinical Psychiatry News. August 7, 2014. http://www. clinicalpsychiatrynews.com/home/article/telepsychiatry-is-a-tool-that-we-must-exploit/28c87bec298e0aa208309fa 9bc48dedc.html.

• University of Colorado Denver. Telemental Health Guide. http:// www.tmhguide.org.

Disclosure

Dr. Kornbluh reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Shore JH. Telepsychiatry: videoconferencing in the delivery of psychiatric care. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):256-262.

2. Konrad TR, Ellis AR, Thomas KC, et al. County-level estimates of need for mental health professionals in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1307-1314.

3. Vernon DJ, Salsberg E, Erikson C, et al. Planning the future mental health workforce: with progress on coverage, what role will psychiatrists play? Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(3):187-192.

4. Carrns A. Understanding new rules that widen mental health coverage. The New York Times. http://www. nytimes.com/2014/01/10/your-money/understanding-new-rules-that-widen-mental-health-coverage.html. Published January 9, 2014. Accessed February 10, 2015.

5. Myers KM, Valentine JM, Melzer SM. Feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability of telepsychiatry for children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(11):1493-1496.

6. Nelson EL, Barnard M, Cain S. Treating childhood depression over videoconferencing. Telemed J E Health. 2003;9(1):49-55.

7. Boydell KM, Hodgins M, Pignatiello A, et al. Using technology to deliver mental health services to children and youth: a scoping review. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(2):87-99.

8. Pakyurek M, Yellowlees P, Hilty D. The child and adolescent telepsychiatry consultation: can it be a more effective clinical process for certain patients than conventional practice? Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(3):289-292.

9. Poon P, Hui E, Dai D, et al. Cognitive intervention for community-dwelling older persons with memory problems: telemedicine versus face-to-face treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(3):285-286.

10. Rabinowitz T, Murphy KM, Amour JL, et al. Benefits of a telepsychiatry consultation service for rural nursing home residents. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(1):34-40.

11. Deslich SA, Thistlethwaite T, Coustasse A. Telepsychiatry in correctional facilities: using technology to improve access and decrease costs of mental health care in underserved populations. Perm J. 2013;17(3):80-86.

12. James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji. pdf. Updated December 14, 2006. Accessed February 10, 2015.

13. Hilty DN, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, et al. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(6):444-454.

14. Maheu MM, Mcmenamin J. Telepsychiatry: the perils of using skype. Psychiatric Times. http://www. psychiatrictimes.com/blog/telepsychiatry-perils-using-skype. Published March 28, 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

15. Knoedler DW. Telepsychiatry: first week in the trenches. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/ blogs/couch-crisis/telepsychiatry-first-week-trenches. Published January 22, 2014. Accessed February 15, 2015.

16. Secure Telehealth. Medicaid reimburses for telehealth in 41 states. http://www.securetelehealth.com/medicaid-reimbursement.html. Updated January 15, 2015. Accessed February 10, 2015.

17. Federation of State Medical Boards. Telemedicine overview: Board-by-Board approach. http://library.fsmb.org/pdf/ grpol_telemedicine_licensure.pdf. Updated June 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

18. Joint Commission Perspectives. Accepted: final revisions to telemedicine standards. http://www.jointcommission. org/assets/1/6/Revisions_telemedicine_standards.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed February 10, 2015.

19. Hyler SE, Gangure DP. Legal and ethical challenges in telepsychiatry. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(4):272-276.

20. Kornbluh RA. Staying true to the mission: adapting telepsychiatry to a new environment. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(6):482-483.

1. Shore JH. Telepsychiatry: videoconferencing in the delivery of psychiatric care. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(3):256-262.

2. Konrad TR, Ellis AR, Thomas KC, et al. County-level estimates of need for mental health professionals in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1307-1314.

3. Vernon DJ, Salsberg E, Erikson C, et al. Planning the future mental health workforce: with progress on coverage, what role will psychiatrists play? Acad Psychiatry. 2009;33(3):187-192.

4. Carrns A. Understanding new rules that widen mental health coverage. The New York Times. http://www. nytimes.com/2014/01/10/your-money/understanding-new-rules-that-widen-mental-health-coverage.html. Published January 9, 2014. Accessed February 10, 2015.

5. Myers KM, Valentine JM, Melzer SM. Feasibility, acceptability, and sustainability of telepsychiatry for children and adolescents. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(11):1493-1496.

6. Nelson EL, Barnard M, Cain S. Treating childhood depression over videoconferencing. Telemed J E Health. 2003;9(1):49-55.

7. Boydell KM, Hodgins M, Pignatiello A, et al. Using technology to deliver mental health services to children and youth: a scoping review. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(2):87-99.

8. Pakyurek M, Yellowlees P, Hilty D. The child and adolescent telepsychiatry consultation: can it be a more effective clinical process for certain patients than conventional practice? Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(3):289-292.

9. Poon P, Hui E, Dai D, et al. Cognitive intervention for community-dwelling older persons with memory problems: telemedicine versus face-to-face treatment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;20(3):285-286.

10. Rabinowitz T, Murphy KM, Amour JL, et al. Benefits of a telepsychiatry consultation service for rural nursing home residents. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16(1):34-40.

11. Deslich SA, Thistlethwaite T, Coustasse A. Telepsychiatry in correctional facilities: using technology to improve access and decrease costs of mental health care in underserved populations. Perm J. 2013;17(3):80-86.

12. James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mhppji. pdf. Updated December 14, 2006. Accessed February 10, 2015.

13. Hilty DN, Ferrer DC, Parish MB, et al. The effectiveness of telemental health: a 2013 review. Telemed J E Health. 2013;19(6):444-454.

14. Maheu MM, Mcmenamin J. Telepsychiatry: the perils of using skype. Psychiatric Times. http://www. psychiatrictimes.com/blog/telepsychiatry-perils-using-skype. Published March 28, 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

15. Knoedler DW. Telepsychiatry: first week in the trenches. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/ blogs/couch-crisis/telepsychiatry-first-week-trenches. Published January 22, 2014. Accessed February 15, 2015.

16. Secure Telehealth. Medicaid reimburses for telehealth in 41 states. http://www.securetelehealth.com/medicaid-reimbursement.html. Updated January 15, 2015. Accessed February 10, 2015.

17. Federation of State Medical Boards. Telemedicine overview: Board-by-Board approach. http://library.fsmb.org/pdf/ grpol_telemedicine_licensure.pdf. Updated June 2013. Accessed February 10, 2015.

18. Joint Commission Perspectives. Accepted: final revisions to telemedicine standards. http://www.jointcommission. org/assets/1/6/Revisions_telemedicine_standards.pdf. Published January 2012. Accessed February 10, 2015.

19. Hyler SE, Gangure DP. Legal and ethical challenges in telepsychiatry. J Psychiatr Pract. 2004;10(4):272-276.

20. Kornbluh RA. Staying true to the mission: adapting telepsychiatry to a new environment. CNS Spectr. 2014;19(6):482-483.

Telepsychiatry is a tool that we must exploit

As psychiatrists, we are particularly attuned to the value of face-to-face contact with patients. After all, so much is communicated nonverbally.

Fortunately, telepsychiatry has the capacity to give us the information we need to provide effective interventions for patients with mental illness. Even patients with serious mental illness can benefit from these interventions.

Take, for example, a literature review of 390 studies using terms that included "schizophrenia" and/or "telepsychiatry," "telemedicine," or "telepsychology" (Clin. Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses 2014 [doi:10.3371/CSRP.KAFE.021513]). The review, conducted by Dr. John Kasckow of the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Health Care System, found that modalities involving the telephone, the Internet, and videoconferencing "appear to be feasible in patients with schizophrenia." Furthermore, they found that those modalities appear to improve patient outcomes, although they acknowledge that more research is needed.

A subset of patients that can benefit from telepsychiatry is those in correctional facilities. Another literature review that looked at the implementation of telepsychiatry in correctional facilities in seven states, including my own state of California, and found that the modality "may improve living conditions and safety inside correctional facilities" (Perm. J. 2013 Summer;17:80-6). This review, conducted by Stacie Anne Deslich of the Marshall University in South Charleston, W.Va., and her colleagues, also found that using telepsychiatry improved access and saved those facilities $12,000 to more than $1 million.

These researchers also called for more study, particularly a case-control examination of the cost of providing psychiatric care through telemedicine vs. face-to-face psychiatric treatment. Using telepsychiatry for this population of patients is particularly important in light of depth and breadth of untreated mental illness in correctional facilities, such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, and schizophrenia. "In addition, costs for providers traveling to distant facilities have been a deterrent to providing adequate care to inmates," Ms. Deslich wrote.

Yet another population of patients that can benefit from telepsychiatry is those with mental illness who come to emergency departments. A program implemented in Elizabeth City, N.C., connected patients in the ED with psychiatric providers who were at remote locations using telemedicine carts that were equipped with wireless technology (ED Manag. 2013;25:121-4). The program’s administrators reported that almost 30% of the patients who had involuntary commitment orders were stabilized to the extent that those orders could be rescinded and they were discharged to outpatient care. Furthermore, the researchers reported, the average length of stay for ED patients who were discharged to inpatient treatment facilities dropped by more than half, from 48 hours to 22.5 hours.

Not so surprisingly, telepsychiatry also is establishing a solid track record among young patients. A study of the perspectives of psychiatrists who provide consultation services to schools found "students were more likely to disclose clinical information via video, compared with face-to-face contact" (Telemed. J.E. Health 2013; 19;794-9). However, the psychiatrists did express concerns about technological difficulties, logistics, and information sharing.

Telepsychiatry also is gaining a foothold in other areas, such as in geriatric and consultation psychiatry. In other settings, telepsychiatry is being introduced, and evidence is still accumulating.

The primary driver of telepsychiatry is the psychiatrist shortage. In 2009, a total of 77% of U.S. counties reported a shortage. Additionally, recent increases in coverage for mental health care create a demand for more psychiatrist time. These factors, coupled with an aging psychiatry workforce, led to a growing imbalance between supply and demand that telepsychiatry can help to alleviate. Telepsychiatry can increase the efficiency of psychiatric care by allowing one psychiatrist to serve patients in multiple settings without burdensome travel. Although telepsychiatry was first used more than 30 years ago, only recently have demographic, economic, and cultural trends led to its rapid expansion.

Opportunities for telepsychiatry implementation exist across the spectrum of psychiatric care. So far, research has shown little or no difference between the outcomes yielded by traditional care and telepsychiatry. Work remains to be done, but clearly telepsychiatry is here to stay.

Dr. Kornbluh is assistant medical director for program improvement and telepsychiatry at the California Department of State Hospitals.

As psychiatrists, we are particularly attuned to the value of face-to-face contact with patients. After all, so much is communicated nonverbally.

Fortunately, telepsychiatry has the capacity to give us the information we need to provide effective interventions for patients with mental illness. Even patients with serious mental illness can benefit from these interventions.

Take, for example, a literature review of 390 studies using terms that included "schizophrenia" and/or "telepsychiatry," "telemedicine," or "telepsychology" (Clin. Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses 2014 [doi:10.3371/CSRP.KAFE.021513]). The review, conducted by Dr. John Kasckow of the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Health Care System, found that modalities involving the telephone, the Internet, and videoconferencing "appear to be feasible in patients with schizophrenia." Furthermore, they found that those modalities appear to improve patient outcomes, although they acknowledge that more research is needed.

A subset of patients that can benefit from telepsychiatry is those in correctional facilities. Another literature review that looked at the implementation of telepsychiatry in correctional facilities in seven states, including my own state of California, and found that the modality "may improve living conditions and safety inside correctional facilities" (Perm. J. 2013 Summer;17:80-6). This review, conducted by Stacie Anne Deslich of the Marshall University in South Charleston, W.Va., and her colleagues, also found that using telepsychiatry improved access and saved those facilities $12,000 to more than $1 million.

These researchers also called for more study, particularly a case-control examination of the cost of providing psychiatric care through telemedicine vs. face-to-face psychiatric treatment. Using telepsychiatry for this population of patients is particularly important in light of depth and breadth of untreated mental illness in correctional facilities, such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, and schizophrenia. "In addition, costs for providers traveling to distant facilities have been a deterrent to providing adequate care to inmates," Ms. Deslich wrote.

Yet another population of patients that can benefit from telepsychiatry is those with mental illness who come to emergency departments. A program implemented in Elizabeth City, N.C., connected patients in the ED with psychiatric providers who were at remote locations using telemedicine carts that were equipped with wireless technology (ED Manag. 2013;25:121-4). The program’s administrators reported that almost 30% of the patients who had involuntary commitment orders were stabilized to the extent that those orders could be rescinded and they were discharged to outpatient care. Furthermore, the researchers reported, the average length of stay for ED patients who were discharged to inpatient treatment facilities dropped by more than half, from 48 hours to 22.5 hours.

Not so surprisingly, telepsychiatry also is establishing a solid track record among young patients. A study of the perspectives of psychiatrists who provide consultation services to schools found "students were more likely to disclose clinical information via video, compared with face-to-face contact" (Telemed. J.E. Health 2013; 19;794-9). However, the psychiatrists did express concerns about technological difficulties, logistics, and information sharing.

Telepsychiatry also is gaining a foothold in other areas, such as in geriatric and consultation psychiatry. In other settings, telepsychiatry is being introduced, and evidence is still accumulating.

The primary driver of telepsychiatry is the psychiatrist shortage. In 2009, a total of 77% of U.S. counties reported a shortage. Additionally, recent increases in coverage for mental health care create a demand for more psychiatrist time. These factors, coupled with an aging psychiatry workforce, led to a growing imbalance between supply and demand that telepsychiatry can help to alleviate. Telepsychiatry can increase the efficiency of psychiatric care by allowing one psychiatrist to serve patients in multiple settings without burdensome travel. Although telepsychiatry was first used more than 30 years ago, only recently have demographic, economic, and cultural trends led to its rapid expansion.

Opportunities for telepsychiatry implementation exist across the spectrum of psychiatric care. So far, research has shown little or no difference between the outcomes yielded by traditional care and telepsychiatry. Work remains to be done, but clearly telepsychiatry is here to stay.

Dr. Kornbluh is assistant medical director for program improvement and telepsychiatry at the California Department of State Hospitals.

As psychiatrists, we are particularly attuned to the value of face-to-face contact with patients. After all, so much is communicated nonverbally.

Fortunately, telepsychiatry has the capacity to give us the information we need to provide effective interventions for patients with mental illness. Even patients with serious mental illness can benefit from these interventions.

Take, for example, a literature review of 390 studies using terms that included "schizophrenia" and/or "telepsychiatry," "telemedicine," or "telepsychology" (Clin. Schizophr. Relat. Psychoses 2014 [doi:10.3371/CSRP.KAFE.021513]). The review, conducted by Dr. John Kasckow of the Veterans Affairs Pittsburgh Health Care System, found that modalities involving the telephone, the Internet, and videoconferencing "appear to be feasible in patients with schizophrenia." Furthermore, they found that those modalities appear to improve patient outcomes, although they acknowledge that more research is needed.

A subset of patients that can benefit from telepsychiatry is those in correctional facilities. Another literature review that looked at the implementation of telepsychiatry in correctional facilities in seven states, including my own state of California, and found that the modality "may improve living conditions and safety inside correctional facilities" (Perm. J. 2013 Summer;17:80-6). This review, conducted by Stacie Anne Deslich of the Marshall University in South Charleston, W.Va., and her colleagues, also found that using telepsychiatry improved access and saved those facilities $12,000 to more than $1 million.

These researchers also called for more study, particularly a case-control examination of the cost of providing psychiatric care through telemedicine vs. face-to-face psychiatric treatment. Using telepsychiatry for this population of patients is particularly important in light of depth and breadth of untreated mental illness in correctional facilities, such as depression, anxiety, bipolar disorders, and schizophrenia. "In addition, costs for providers traveling to distant facilities have been a deterrent to providing adequate care to inmates," Ms. Deslich wrote.

Yet another population of patients that can benefit from telepsychiatry is those with mental illness who come to emergency departments. A program implemented in Elizabeth City, N.C., connected patients in the ED with psychiatric providers who were at remote locations using telemedicine carts that were equipped with wireless technology (ED Manag. 2013;25:121-4). The program’s administrators reported that almost 30% of the patients who had involuntary commitment orders were stabilized to the extent that those orders could be rescinded and they were discharged to outpatient care. Furthermore, the researchers reported, the average length of stay for ED patients who were discharged to inpatient treatment facilities dropped by more than half, from 48 hours to 22.5 hours.

Not so surprisingly, telepsychiatry also is establishing a solid track record among young patients. A study of the perspectives of psychiatrists who provide consultation services to schools found "students were more likely to disclose clinical information via video, compared with face-to-face contact" (Telemed. J.E. Health 2013; 19;794-9). However, the psychiatrists did express concerns about technological difficulties, logistics, and information sharing.

Telepsychiatry also is gaining a foothold in other areas, such as in geriatric and consultation psychiatry. In other settings, telepsychiatry is being introduced, and evidence is still accumulating.

The primary driver of telepsychiatry is the psychiatrist shortage. In 2009, a total of 77% of U.S. counties reported a shortage. Additionally, recent increases in coverage for mental health care create a demand for more psychiatrist time. These factors, coupled with an aging psychiatry workforce, led to a growing imbalance between supply and demand that telepsychiatry can help to alleviate. Telepsychiatry can increase the efficiency of psychiatric care by allowing one psychiatrist to serve patients in multiple settings without burdensome travel. Although telepsychiatry was first used more than 30 years ago, only recently have demographic, economic, and cultural trends led to its rapid expansion.

Opportunities for telepsychiatry implementation exist across the spectrum of psychiatric care. So far, research has shown little or no difference between the outcomes yielded by traditional care and telepsychiatry. Work remains to be done, but clearly telepsychiatry is here to stay.

Dr. Kornbluh is assistant medical director for program improvement and telepsychiatry at the California Department of State Hospitals.