User login

A rarely discussed aspect of the opioid crisis

Your article, “A patient-centered approach to tapering opioids” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:548-556) by Davis et al is the most thoughtful article I have seen on opioids. The patient-centered ap-proach takes this article to a place that is rarely discussed in the opioid crisis.

If we could really understand and treat chronic psychic and physical pain better, we might begin to have a real impact on this crisis. I completely agree that evidence-based intensive trauma treatment is generally unavailable in the United States. I have been working with women in a residential chemical dependency treatment program for the past 15 years and more than 90% of them were sexually abused. Trauma can lead to all forms of addiction, and trauma induced hyperalgesia is not the same as nociceptive pain.

We have so many unaddressed mental health issues in our country and your article emphasized the importance of understanding people and their mental health issues rather than taking a formulaic approach and replacing one opioid with another. It is clear to me that we will not win this battle with medication-assisted treatment alone.

Richard Usatine, MD

San Antonio, TX

Associate Editor, The Journal of Family Practice

Your article, “A patient-centered approach to tapering opioids” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:548-556) by Davis et al is the most thoughtful article I have seen on opioids. The patient-centered ap-proach takes this article to a place that is rarely discussed in the opioid crisis.

If we could really understand and treat chronic psychic and physical pain better, we might begin to have a real impact on this crisis. I completely agree that evidence-based intensive trauma treatment is generally unavailable in the United States. I have been working with women in a residential chemical dependency treatment program for the past 15 years and more than 90% of them were sexually abused. Trauma can lead to all forms of addiction, and trauma induced hyperalgesia is not the same as nociceptive pain.

We have so many unaddressed mental health issues in our country and your article emphasized the importance of understanding people and their mental health issues rather than taking a formulaic approach and replacing one opioid with another. It is clear to me that we will not win this battle with medication-assisted treatment alone.

Richard Usatine, MD

San Antonio, TX

Associate Editor, The Journal of Family Practice

Your article, “A patient-centered approach to tapering opioids” (J Fam Pract. 2019;68:548-556) by Davis et al is the most thoughtful article I have seen on opioids. The patient-centered ap-proach takes this article to a place that is rarely discussed in the opioid crisis.

If we could really understand and treat chronic psychic and physical pain better, we might begin to have a real impact on this crisis. I completely agree that evidence-based intensive trauma treatment is generally unavailable in the United States. I have been working with women in a residential chemical dependency treatment program for the past 15 years and more than 90% of them were sexually abused. Trauma can lead to all forms of addiction, and trauma induced hyperalgesia is not the same as nociceptive pain.

We have so many unaddressed mental health issues in our country and your article emphasized the importance of understanding people and their mental health issues rather than taking a formulaic approach and replacing one opioid with another. It is clear to me that we will not win this battle with medication-assisted treatment alone.

Richard Usatine, MD

San Antonio, TX

Associate Editor, The Journal of Family Practice

Facial swelling in an adolescent

A 16-year-old boy sought care at a rural hospital in Panama for facial swelling that began 3 months earlier. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a volunteer effort. The patient had difficulty opening his left eye. He denied fever and chills, and said he felt well—other than his inability to see out of his left eye. He denied any changes to his vision when he held the swollen eyelids open. The patient lived on a ranch far outside of town, and he walked down a mountain road alone for 6 hours with one eye swollen shut to present for treatment. The patient was not taking any medications and had not received any health care since his last vaccine several years ago. On physical exam, his vital signs were normal, and the swelling under his left eye was somewhat tender and slightly warm to the touch. There were no lesions on his trunk and the remainder of the exam was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nodulocystic acne

The family physician (FP) diagnosed severe inflammatory nodulocystic acne in this patient. He initially was concerned about possible cellulitis or an abscess, but his clinical experience suggested the swelling was secondary to severe inflammation and not a bacterial infection. The FP noted that the patient was afebrile and lacked systemic symptoms. In addition, the presence of open and closed comedones on the face, as well as the patient’s age and sex, supported the diagnosis of acne. No tests were performed; the diagnosis was made clinically.

A case of acne, or a bacterial infection?

The FP considered acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and a bacterial infection as other possible causes of the patient’s facial swelling.

Acne conglobata is a form of severe inflammatory cystic acne that affects the face, chest, and back. It is characterized by nodules, cysts, large open comedones, and interconnecting sinuses.1,2 Although this case of acne was severe, the young man did not have large open comedones or interconnecting sinus tracts. In addition, his trunk was unaffected.

Acne fulminans is a type of severe cystic acne with systemic symptoms, which is mainly seen in adolescent males. It may have a sudden onset and is characterized by ulcerated, nodular, and painful acne that bleeds, crusts, and results in severe scarring. Patients may present with fever, joint pain, and weight loss.1,2 Our patient did not have systemic symptoms despite the severe facial swelling.

Bacterial infections of the skin usually are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) or Streptococcus pyogenes and can lead to cellulitis and/or abscess formation.3 This process was considered as a complication of the severe acne, but the clinical picture was consistent with severe inflammation rather than a bacterial superinfection.

Continue to: Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

The FP knew that the severe inflammation and swelling needed to be treated with a systemic steroid, so he started the patient on prednisone 60 mg orally once daily at the time of presentation. Additionally, the FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg bid to treat the inflammation and to cover a possible superinfection.

Doxycycline is the oral antibiotic of choice for inflammatory acne.2 It also is a good antibiotic for cutaneous methicillin-resistant S aureus infection.3 Although it is not the treatment of choice for a nonpurulent cellulitis, it is a good option for cellulitis with purulence.3

With the working diagnosis of severe inflammatory acne, it was expected that the prednisone and doxycycline would be effective. Treating with antibiotics alone (for fear of causing immunosuppression with steroids) would have likely been less effective. Since the patient lived 6 hours from the hospital by foot and was alone, he was admitted overnight for observation (with parental permission obtained over the phone).

The patient’s condition improved overnight. Marked improvement in the swelling and inflammation was noted the following morning (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The patient was pleased with the results and was discharged to return home (transportation provided by the hospital) with directions on how to continue the oral prednisone and doxycycline. He was given 1 month of doxycycline to continue (100 mg bid) and enough oral prednisone to take 40 mg/d for 1 week and 20 mg/d for another week. He was given a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks to assess his acne and his ability to tolerate the medications.

He was warned to avoid the sun as much as possible, as doxycycline is photosensitizing, and to use a large hat and sunscreen when the sun could not be avoided. (Another option would have been to prescribe minocycline 100 mg bid because it is equally effective for acne with a lower risk for photosensitization.2)

Continue to: Access to medical care was limited

Access to medical care was limited. Although this patient was a good candidate for oral isotretinoin treatment, he did not have access to this medication in rural Panama. Managing his acne was challenging because of the severity of the case and the patient’s sun exposure in this tropical country. Access to the full range of topical anti-acne treatments also is limited in rural Panama, but fortunately his response to the initial oral medications was good.

The future plan at the follow-up visit consisted of continuing the doxycycline, stopping the prednisone, and adding topical benzoyl peroxide. The purpose of the benzoyl peroxide was to prevent bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Usatine, MD, Skin Clinic, 903 W Martin Ave, Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected]

1. Usatine R, Bambekova P, Shiu V. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:717-724.

2. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:E10-E52.

A 16-year-old boy sought care at a rural hospital in Panama for facial swelling that began 3 months earlier. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a volunteer effort. The patient had difficulty opening his left eye. He denied fever and chills, and said he felt well—other than his inability to see out of his left eye. He denied any changes to his vision when he held the swollen eyelids open. The patient lived on a ranch far outside of town, and he walked down a mountain road alone for 6 hours with one eye swollen shut to present for treatment. The patient was not taking any medications and had not received any health care since his last vaccine several years ago. On physical exam, his vital signs were normal, and the swelling under his left eye was somewhat tender and slightly warm to the touch. There were no lesions on his trunk and the remainder of the exam was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nodulocystic acne

The family physician (FP) diagnosed severe inflammatory nodulocystic acne in this patient. He initially was concerned about possible cellulitis or an abscess, but his clinical experience suggested the swelling was secondary to severe inflammation and not a bacterial infection. The FP noted that the patient was afebrile and lacked systemic symptoms. In addition, the presence of open and closed comedones on the face, as well as the patient’s age and sex, supported the diagnosis of acne. No tests were performed; the diagnosis was made clinically.

A case of acne, or a bacterial infection?

The FP considered acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and a bacterial infection as other possible causes of the patient’s facial swelling.

Acne conglobata is a form of severe inflammatory cystic acne that affects the face, chest, and back. It is characterized by nodules, cysts, large open comedones, and interconnecting sinuses.1,2 Although this case of acne was severe, the young man did not have large open comedones or interconnecting sinus tracts. In addition, his trunk was unaffected.

Acne fulminans is a type of severe cystic acne with systemic symptoms, which is mainly seen in adolescent males. It may have a sudden onset and is characterized by ulcerated, nodular, and painful acne that bleeds, crusts, and results in severe scarring. Patients may present with fever, joint pain, and weight loss.1,2 Our patient did not have systemic symptoms despite the severe facial swelling.

Bacterial infections of the skin usually are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) or Streptococcus pyogenes and can lead to cellulitis and/or abscess formation.3 This process was considered as a complication of the severe acne, but the clinical picture was consistent with severe inflammation rather than a bacterial superinfection.

Continue to: Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

The FP knew that the severe inflammation and swelling needed to be treated with a systemic steroid, so he started the patient on prednisone 60 mg orally once daily at the time of presentation. Additionally, the FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg bid to treat the inflammation and to cover a possible superinfection.

Doxycycline is the oral antibiotic of choice for inflammatory acne.2 It also is a good antibiotic for cutaneous methicillin-resistant S aureus infection.3 Although it is not the treatment of choice for a nonpurulent cellulitis, it is a good option for cellulitis with purulence.3

With the working diagnosis of severe inflammatory acne, it was expected that the prednisone and doxycycline would be effective. Treating with antibiotics alone (for fear of causing immunosuppression with steroids) would have likely been less effective. Since the patient lived 6 hours from the hospital by foot and was alone, he was admitted overnight for observation (with parental permission obtained over the phone).

The patient’s condition improved overnight. Marked improvement in the swelling and inflammation was noted the following morning (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The patient was pleased with the results and was discharged to return home (transportation provided by the hospital) with directions on how to continue the oral prednisone and doxycycline. He was given 1 month of doxycycline to continue (100 mg bid) and enough oral prednisone to take 40 mg/d for 1 week and 20 mg/d for another week. He was given a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks to assess his acne and his ability to tolerate the medications.

He was warned to avoid the sun as much as possible, as doxycycline is photosensitizing, and to use a large hat and sunscreen when the sun could not be avoided. (Another option would have been to prescribe minocycline 100 mg bid because it is equally effective for acne with a lower risk for photosensitization.2)

Continue to: Access to medical care was limited

Access to medical care was limited. Although this patient was a good candidate for oral isotretinoin treatment, he did not have access to this medication in rural Panama. Managing his acne was challenging because of the severity of the case and the patient’s sun exposure in this tropical country. Access to the full range of topical anti-acne treatments also is limited in rural Panama, but fortunately his response to the initial oral medications was good.

The future plan at the follow-up visit consisted of continuing the doxycycline, stopping the prednisone, and adding topical benzoyl peroxide. The purpose of the benzoyl peroxide was to prevent bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Usatine, MD, Skin Clinic, 903 W Martin Ave, Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected]

A 16-year-old boy sought care at a rural hospital in Panama for facial swelling that began 3 months earlier. He was seen by a family physician (RU) and a team of medical students who were there as part of a volunteer effort. The patient had difficulty opening his left eye. He denied fever and chills, and said he felt well—other than his inability to see out of his left eye. He denied any changes to his vision when he held the swollen eyelids open. The patient lived on a ranch far outside of town, and he walked down a mountain road alone for 6 hours with one eye swollen shut to present for treatment. The patient was not taking any medications and had not received any health care since his last vaccine several years ago. On physical exam, his vital signs were normal, and the swelling under his left eye was somewhat tender and slightly warm to the touch. There were no lesions on his trunk and the remainder of the exam was normal.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Nodulocystic acne

The family physician (FP) diagnosed severe inflammatory nodulocystic acne in this patient. He initially was concerned about possible cellulitis or an abscess, but his clinical experience suggested the swelling was secondary to severe inflammation and not a bacterial infection. The FP noted that the patient was afebrile and lacked systemic symptoms. In addition, the presence of open and closed comedones on the face, as well as the patient’s age and sex, supported the diagnosis of acne. No tests were performed; the diagnosis was made clinically.

A case of acne, or a bacterial infection?

The FP considered acne conglobata, acne fulminans, and a bacterial infection as other possible causes of the patient’s facial swelling.

Acne conglobata is a form of severe inflammatory cystic acne that affects the face, chest, and back. It is characterized by nodules, cysts, large open comedones, and interconnecting sinuses.1,2 Although this case of acne was severe, the young man did not have large open comedones or interconnecting sinus tracts. In addition, his trunk was unaffected.

Acne fulminans is a type of severe cystic acne with systemic symptoms, which is mainly seen in adolescent males. It may have a sudden onset and is characterized by ulcerated, nodular, and painful acne that bleeds, crusts, and results in severe scarring. Patients may present with fever, joint pain, and weight loss.1,2 Our patient did not have systemic symptoms despite the severe facial swelling.

Bacterial infections of the skin usually are caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S aureus) or Streptococcus pyogenes and can lead to cellulitis and/or abscess formation.3 This process was considered as a complication of the severe acne, but the clinical picture was consistent with severe inflammation rather than a bacterial superinfection.

Continue to: Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

Treatment of choice includes prednisone and doxycycline

The FP knew that the severe inflammation and swelling needed to be treated with a systemic steroid, so he started the patient on prednisone 60 mg orally once daily at the time of presentation. Additionally, the FP prescribed doxycycline 100 mg bid to treat the inflammation and to cover a possible superinfection.

Doxycycline is the oral antibiotic of choice for inflammatory acne.2 It also is a good antibiotic for cutaneous methicillin-resistant S aureus infection.3 Although it is not the treatment of choice for a nonpurulent cellulitis, it is a good option for cellulitis with purulence.3

With the working diagnosis of severe inflammatory acne, it was expected that the prednisone and doxycycline would be effective. Treating with antibiotics alone (for fear of causing immunosuppression with steroids) would have likely been less effective. Since the patient lived 6 hours from the hospital by foot and was alone, he was admitted overnight for observation (with parental permission obtained over the phone).

The patient’s condition improved overnight. Marked improvement in the swelling and inflammation was noted the following morning (FIGURES 2A and 2B). The patient was pleased with the results and was discharged to return home (transportation provided by the hospital) with directions on how to continue the oral prednisone and doxycycline. He was given 1 month of doxycycline to continue (100 mg bid) and enough oral prednisone to take 40 mg/d for 1 week and 20 mg/d for another week. He was given a follow-up appointment for 2 weeks to assess his acne and his ability to tolerate the medications.

He was warned to avoid the sun as much as possible, as doxycycline is photosensitizing, and to use a large hat and sunscreen when the sun could not be avoided. (Another option would have been to prescribe minocycline 100 mg bid because it is equally effective for acne with a lower risk for photosensitization.2)

Continue to: Access to medical care was limited

Access to medical care was limited. Although this patient was a good candidate for oral isotretinoin treatment, he did not have access to this medication in rural Panama. Managing his acne was challenging because of the severity of the case and the patient’s sun exposure in this tropical country. Access to the full range of topical anti-acne treatments also is limited in rural Panama, but fortunately his response to the initial oral medications was good.

The future plan at the follow-up visit consisted of continuing the doxycycline, stopping the prednisone, and adding topical benzoyl peroxide. The purpose of the benzoyl peroxide was to prevent bacterial resistance to the antibiotic.2

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard Usatine, MD, Skin Clinic, 903 W Martin Ave, Historic Building, San Antonio, TX 78207; [email protected]

1. Usatine R, Bambekova P, Shiu V. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:717-724.

2. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:E10-E52.

1. Usatine R, Bambekova P, Shiu V. Acne vulgaris. In: Usatine R, Smith M, Mayeaux EJ, et al, eds. Color Atlas and Synopsis of Family Medicine. 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2019:717-724.

2. Zaenglein AL, Pathy AL, Schlosser BJ, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:945-973.

3. Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59:E10-E52.

Biopsies for skin cancer detection: Dispelling the myths

Once it’s determined that a growth requires a biopsy, there is often uncertainty about which type of biopsy to perform. Insufficient knowledge of, and/or experience with, the various biopsy modalities may deter FPs from performing skin biopsies when they are indicated. To help fill the knowledge gaps and better position FPs to tackle skin cancer in its earliest stages, this article identifies and dispels 5 of the most common myths surrounding skin biopsies for the detection of basal and squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma.

MYTH #1

A punch biopsy is always preferred for suspected melanoma because it gets full depth.

A deep shave biopsy (saucerization)—not a punch biopsy—is usually the procedure of choice when biopsying a lesion suspected to be melanoma.2 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) "Melanoma Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology" state that an excisional biopsy (elliptical, punch, or saucerization) with a 1- to 3-mm margin is the preferred method of biopsy for suspected melanoma.3 However, a punch biopsy should be performed only if a 1- to 3-mm margin all around a suspected melanoma can be obtained. Otherwise, a saucerization or elliptical excision is preferred.3

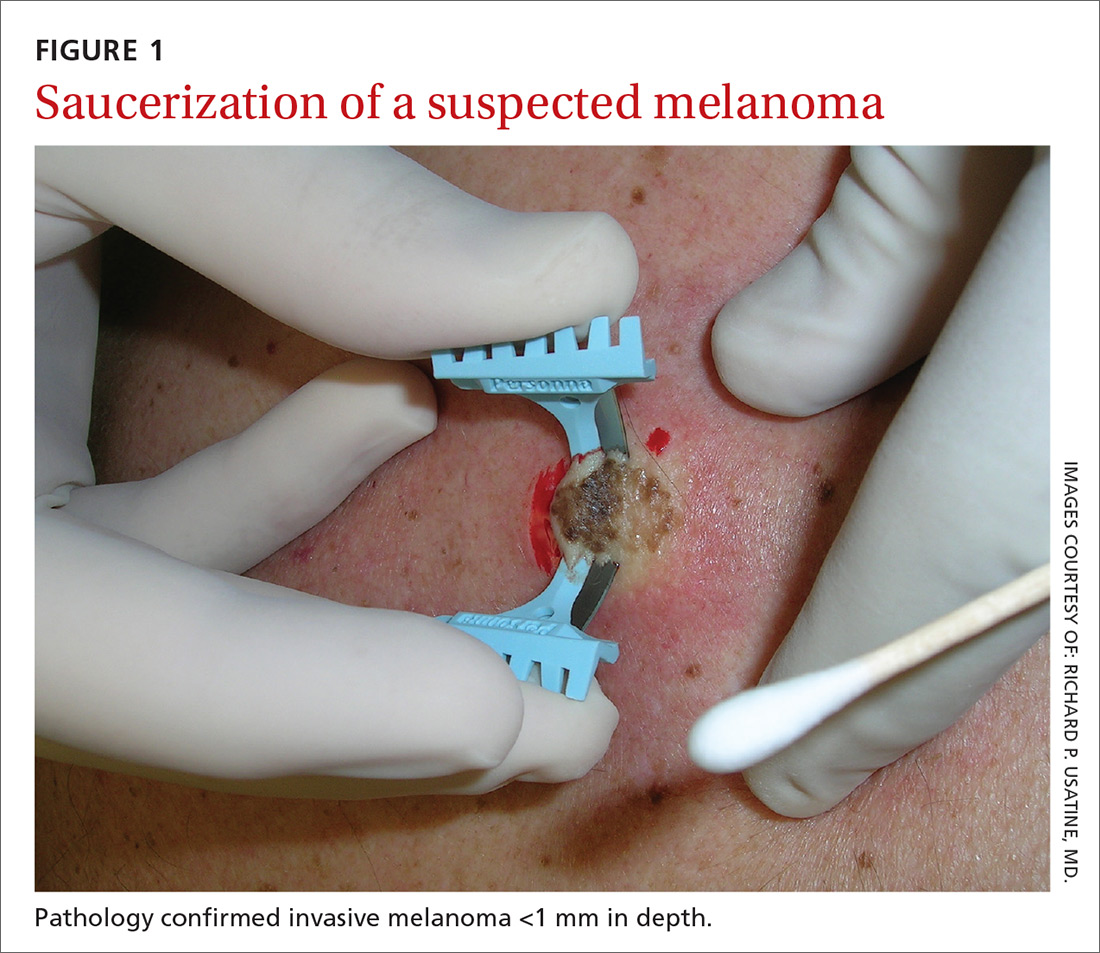

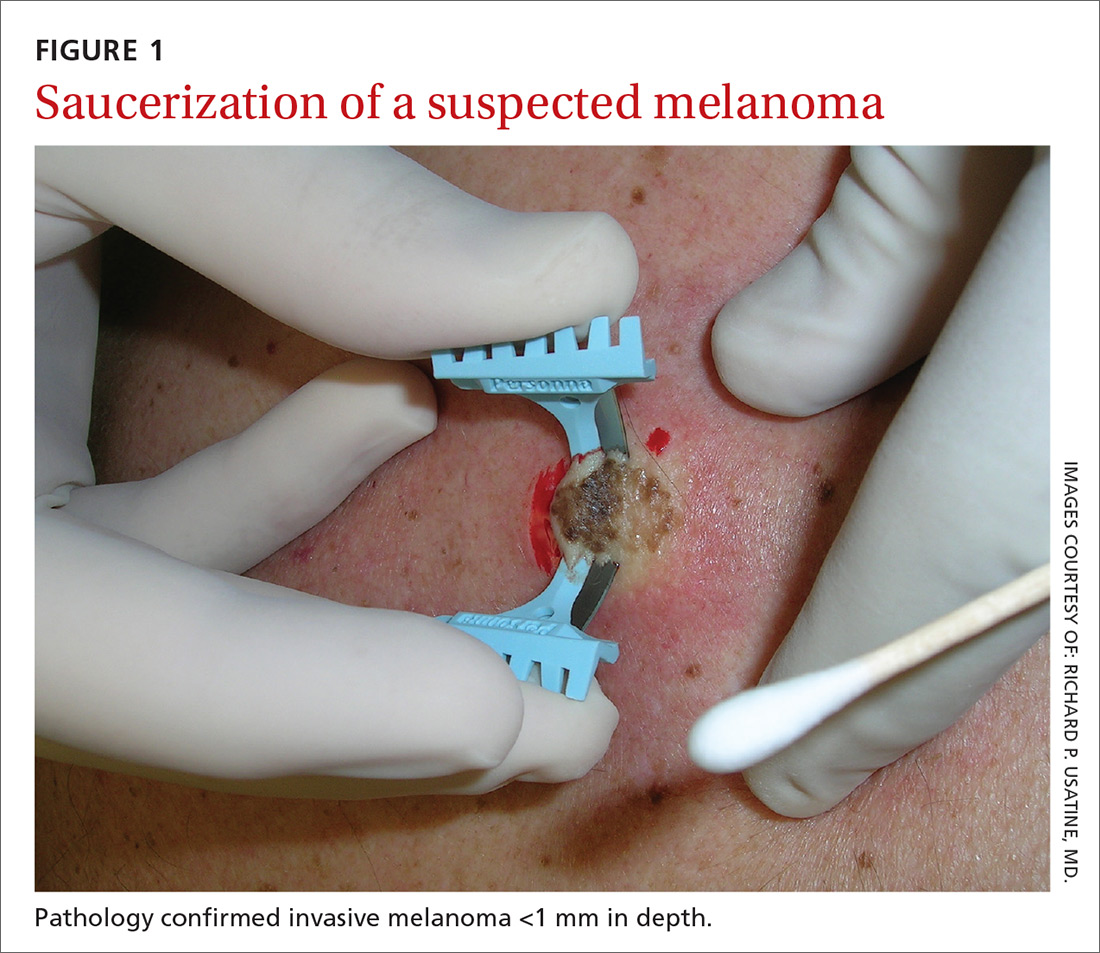

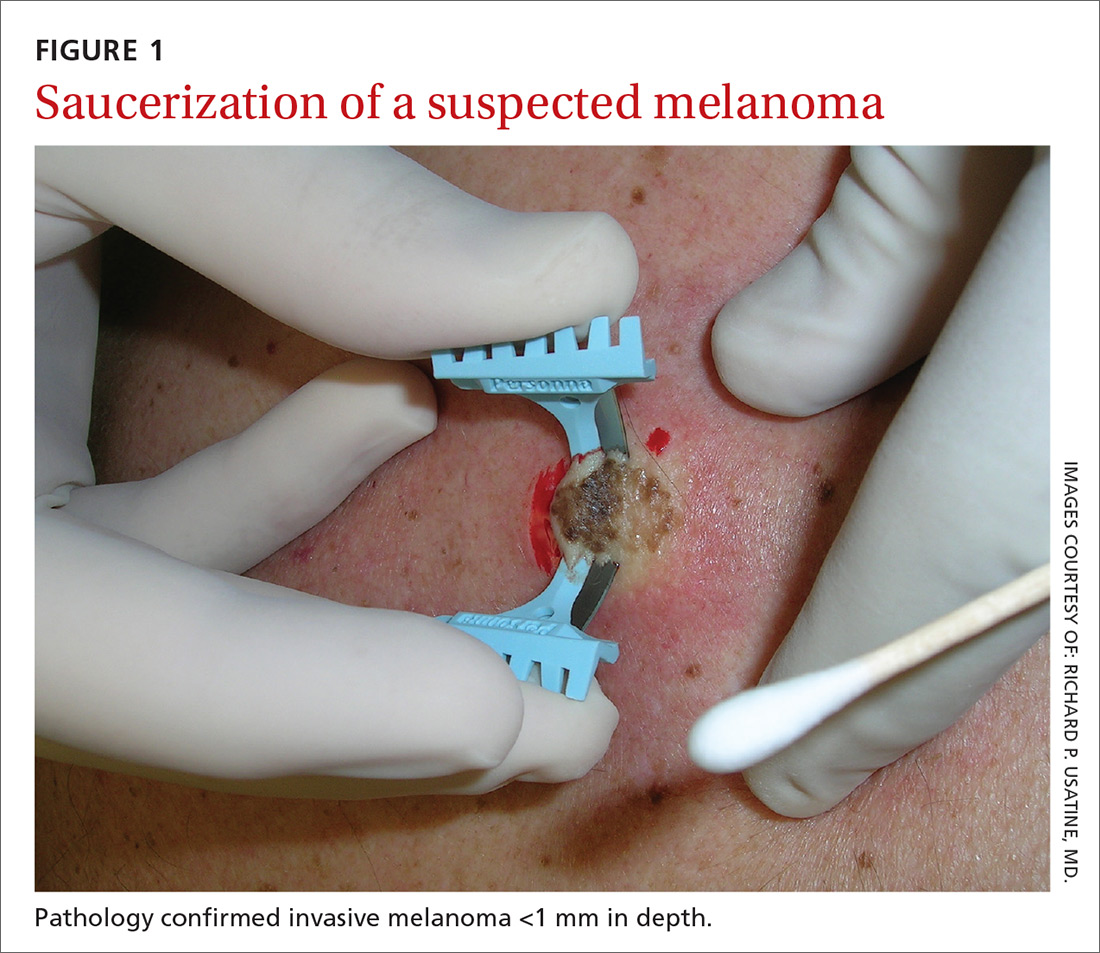

The saucerization technique generally permits optimal sampling in terms of both the breadth and depth of the growth, providing the pathologist with sufficient tissue from both the epidermis and dermis (FIGURE 1).

Why are breadth/depth important? Breadth is important because showing the pathologist the epidermis (especially the edge) of a suspected melanocytic tumor allows for detection of pagetoid spread (upward movement through the epidermis) of melanocytes and of single melanocytes at the edge of a tumor. Single melanocytes at the edge of a tumor and pagetoid spread are histologic features of melanoma that help to distinguish these lesions from nevi, which tend to have nested melanocytes.2

Depth is important because it predicts prognosis and impacts management. For tumors 0.8 mm to 1 mm deep, a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) should be considered.3,4 Although the tumor depth threshold for a SLNB is still debated, most skin cancer experts in the United States agree that a melanoma thicker than 1 mm qualifies for this procedure. Some melanomas with high-risk features (such as ulceration) qualify for an SNLB even if they are <1 mm in depth.5 An SLNB provides prognostic information, and a positive SLNB directly affects staging.

[polldaddy:9990508]

Avoid partial biopsies. For tumors that have been partially biopsied with a punch or shallow shave biopsy, evaluation of the remaining neoplasm after subsequent excision leads to tumor upstaging in 21% of patients, with 10% qualifying for an SLNB.6 Thus, the goal should always be to obtain the entire depth of the tumor with the initial biopsy.

In addition, surgical margins are determined by primary tumor depth. To ensure a depth greater than 1 mm, aim to obtain a tissue specimen that is at least as thick as a dime (1.3 mm).

Because the goal is to avoid partial sampling, a challenge exists when the suspicious growth is large. Many melanomas are broader than a centimeter. And while punch biopsies ensure a depth of 1 mm or more, they risk missing the thickest portion of the tumor.7

Partial sampling of large melanocytic tumors with punch biopsies can lead to sampling error.8 Ng et al9 found there was a significant increase in histopathologic misdiagnosis with a punch biopsy of part of a melanoma (odds ratio [OR]=16.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 10-27; P<.001) and with shallow shave biopsy (OR=2.6; 95% CI, 1.2-5.7; P=.02) compared with excisional biopsy (including saucerization).9 Punch biopsy of part of a melanoma was also associated with increased odds of misdiagnosis with an adverse outcome (OR=20; 95% CI, 10-41; P<.001).

Punch biopsies do, however, offer a reasonable alternative when the melanoma is too broad for a complete saucerization. In these cases, consider multiple 4- to 6-mm punch biopsies to reduce the risk of sampling error.

Avoid performing punch biopsies <4 mm, as the breadth of tissue is inadequate. For example, even with dermoscopy, facial lentigo maligna melanoma is often difficult to differentiate from pigmented actinic keratosis and solar lentigines. (See JFP’s Watch and Learn Video on dermoscopy.) A broad shave biopsy is the preferred method of biopsy for lentigo maligna melanoma in situ according to the NCCN.3 And there have been several reports showing that the results of shave biopsies of melanocytic lesions are cosmetically acceptable to patients.10,11

If the biopsy confirms malignancy, a larger surgery with suturing will be needed. The most important issue to keep in mind is that if partial sampling leads to a benign diagnosis of a suspicious lesion, then the remainder of the lesion must be excised and sent for pathology.

Saucerization is also the preferred biopsy type for basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Studies have shown tumor depth is the most important factor in predicting metastasis of SCC, as well as tumor relapse rate, making accurate identification of the depth of the tumor important for both management and prognosis.12,13 Determining the thickness of the SCC is important for guiding management. SCC in situ is more amenable than invasive SCC to topical therapy or electrodesiccation and curettage.

What you’ll need. FPs can perform saucerization quickly and easily in the office during a standard 15-minute visit. Of course, it is essential to have all the necessary materials available. The key materials needed are lidocaine and epinephrine, a sharp razor blade such as a DermaBlade, and something for hemostasis (aluminum chloride and/or an electrosurgical instrument). Cotton-tipped applicators to apply the aluminum chloride and needles and syringes to administer the local anesthetic are also needed. (See JFP’s Watch and Learn Video on shave biopsy.) A quick saucerization eliminates the need for the patient to return for an elliptical excision and prevents a delayed diagnosis that can occur as a result of a long wait to see a dermatologist.

As a final note, the pathology order form should be completed with information on biopsy type, clinical presentation, differential diagnosis, and whether or not the full lesion was excised.

MYTH #2

A wide excisional biopsy is required for a suspected melanoma.

While complete excision of the entire tumor does allow the pathologist to evaluate the entire growth, wide (>3 mm) margins on the initial biopsy are not necessary. In fact, there are potential disadvantages to full excisional biopsy.

For example, seborrheic keratoses and other benign growths can mimic melanoma. Neither the physician nor the patient wants to learn that a large elliptical wound was created for a growth that turned out to be a benign seborrheic keratosis. Saucerization provides the pathologist with the entire lesion, and the resulting shallow wound heals as a round scar that is most often acceptable to patients.10,11,14 In addition, excisional biopsies carry a higher risk of infection than does saucerization.

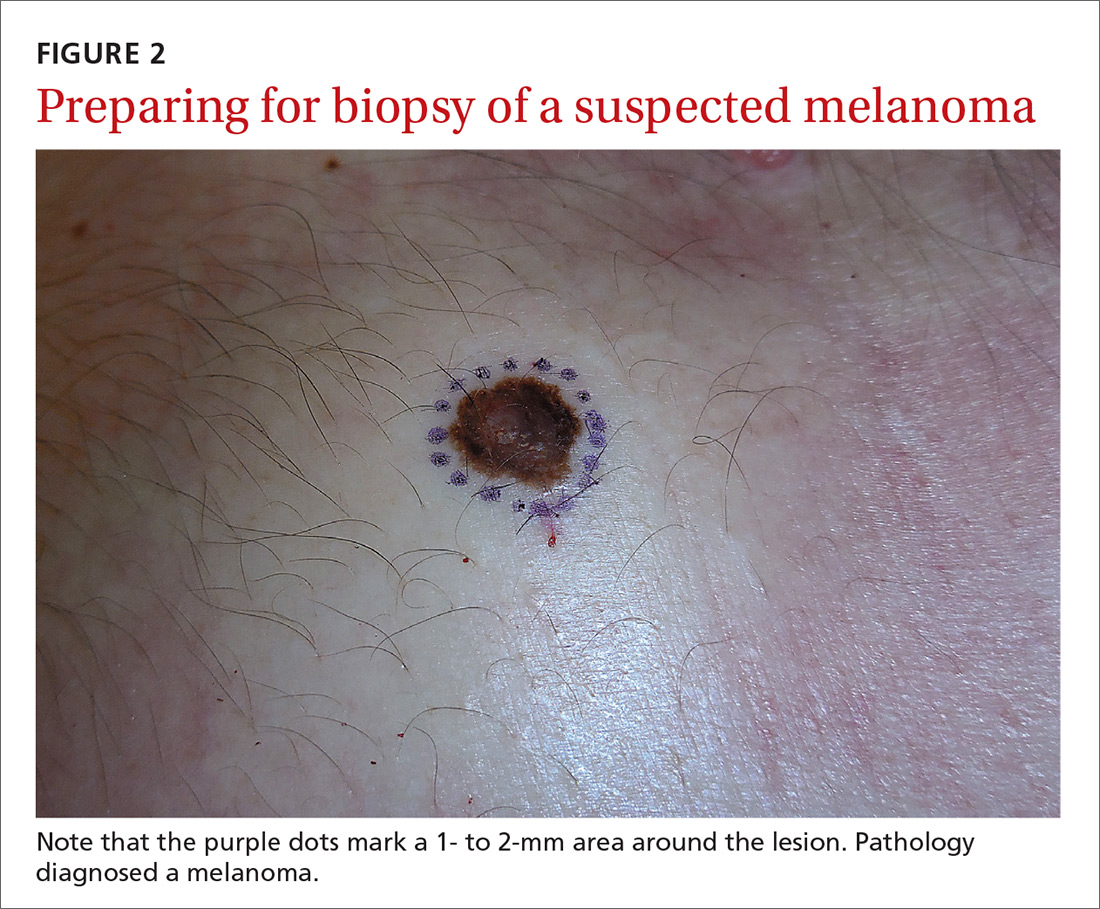

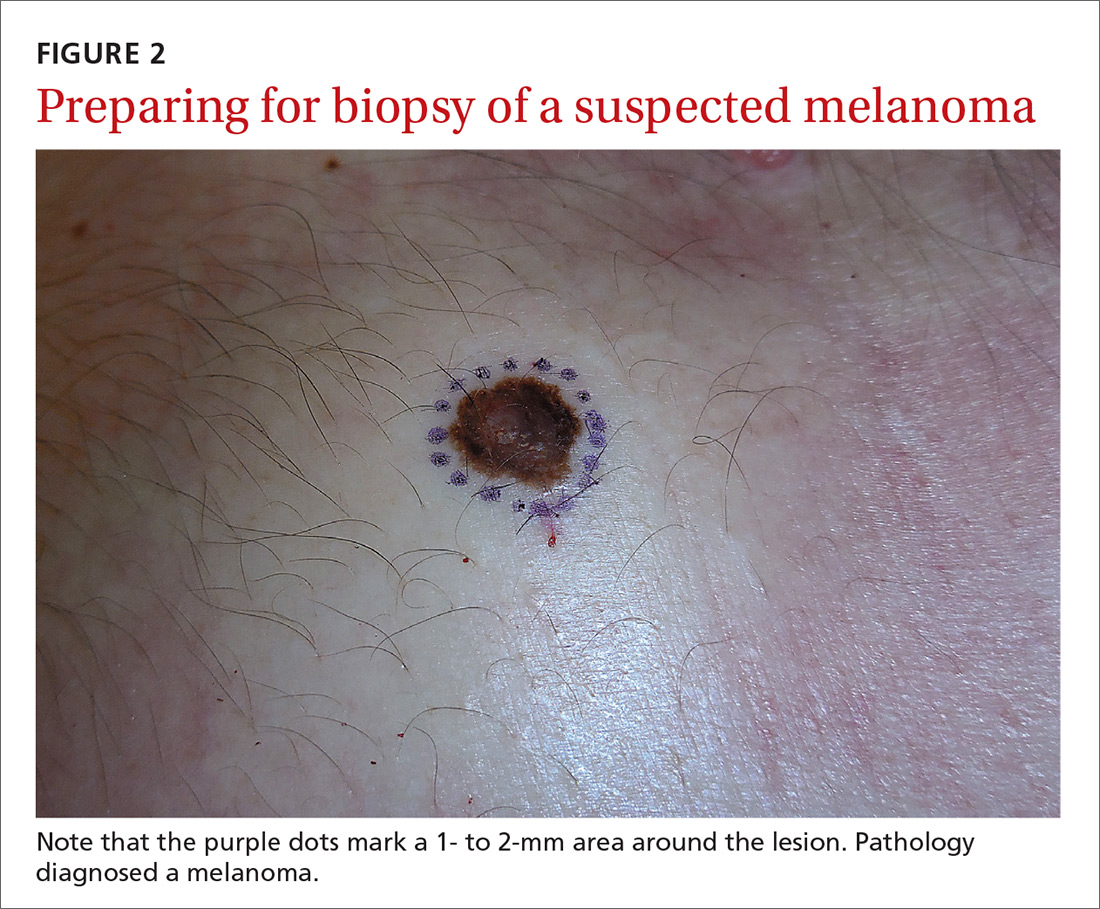

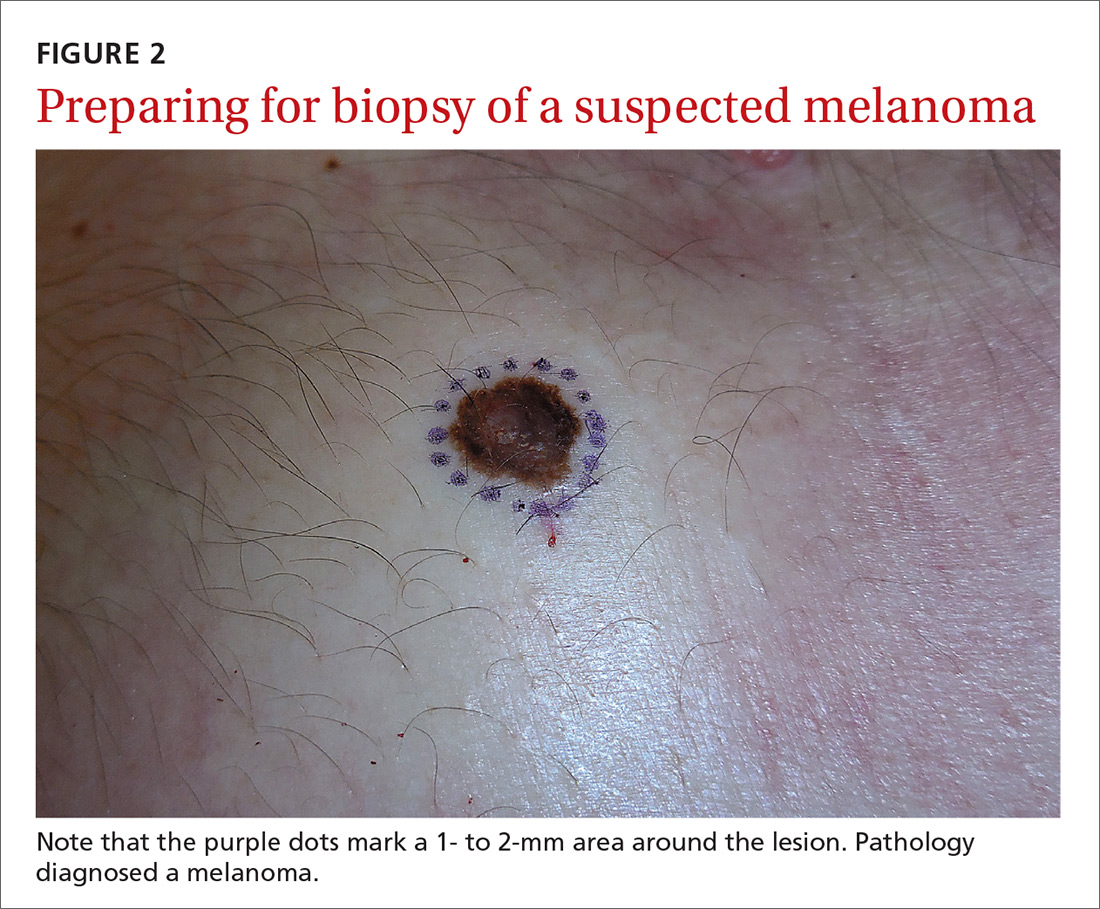

Even when the index of suspicion is high for melanoma, a wide margin is not indicated. NCCN guidelines suggest that the margins around a suspected melanoma on initial biopsy not exceed 3 mm to avoid disrupting the accuracy of an SLNB (FIGURE 2).3

In addition, time constraints (elliptical excisional biopsies can take up to one hour, especially when a layered closure is performed) and a lack of surgical training may prohibit FPs from performing excisions.

One study found that while dermatologists prefer shave biopsies (80.5%), surgeons prefer excisional biopsies (46.3%) and primary care physicians prefer punch biopsies (44%) for biopsy of a growth suspicious for melanoma.7 In fact, of the biopsies FPs perform, only 29% are of the shave variety.7

However, deep shave biopsies can be performed quickly, with the whole process taking less than 5 minutes. We advocate performing them at the time of presentation, as the evidence shows that deep shave biopsies of suspected melanoma are reliable and accurate in 97% of cases.15

MYTH #3

A partial biopsy can make the cancer spread.

There is no evidence to support that a partial biopsy has any effect on the local recurrence or metastatic potential of malignant melanoma.16 In fact, a biopsy elicits an inflammatory response that activates the patient’s immune system and often causes tumor lysis. Some tumors may even resolve after biopsy. In our clinical practice, we have had several cases of basal cell carcinoma resolve after a biopsy without additional treatment.

MYTH #4

If after performing a deep shave biopsy, tumor or pigment remains, you must leave it because a second biopsy specimen can’t be added to the first.

If pigment is visible after an initial shave or punch biopsy, it is reasonable to obtain additional tissue from the base of the biopsy site. While the deeper tissue cannot be added to the initial specimen for the purposes of Breslow’s depth, it is still helpful for the pathologist to have the sample so that he or she can analyze the tumor cells in the dermis. (Melanoma tumor depth is measured as the maximum distance between malignant cells and the top of the granular layer.17) In these situations, be sure to let the pathologist know that there are 2 specimens in the container.

In general, it is valuable to get as much of the tissue as possible at the time of the initial biopsy. One way to avoid leaving tumor at the base of the biopsy is to look at

MYTH #5

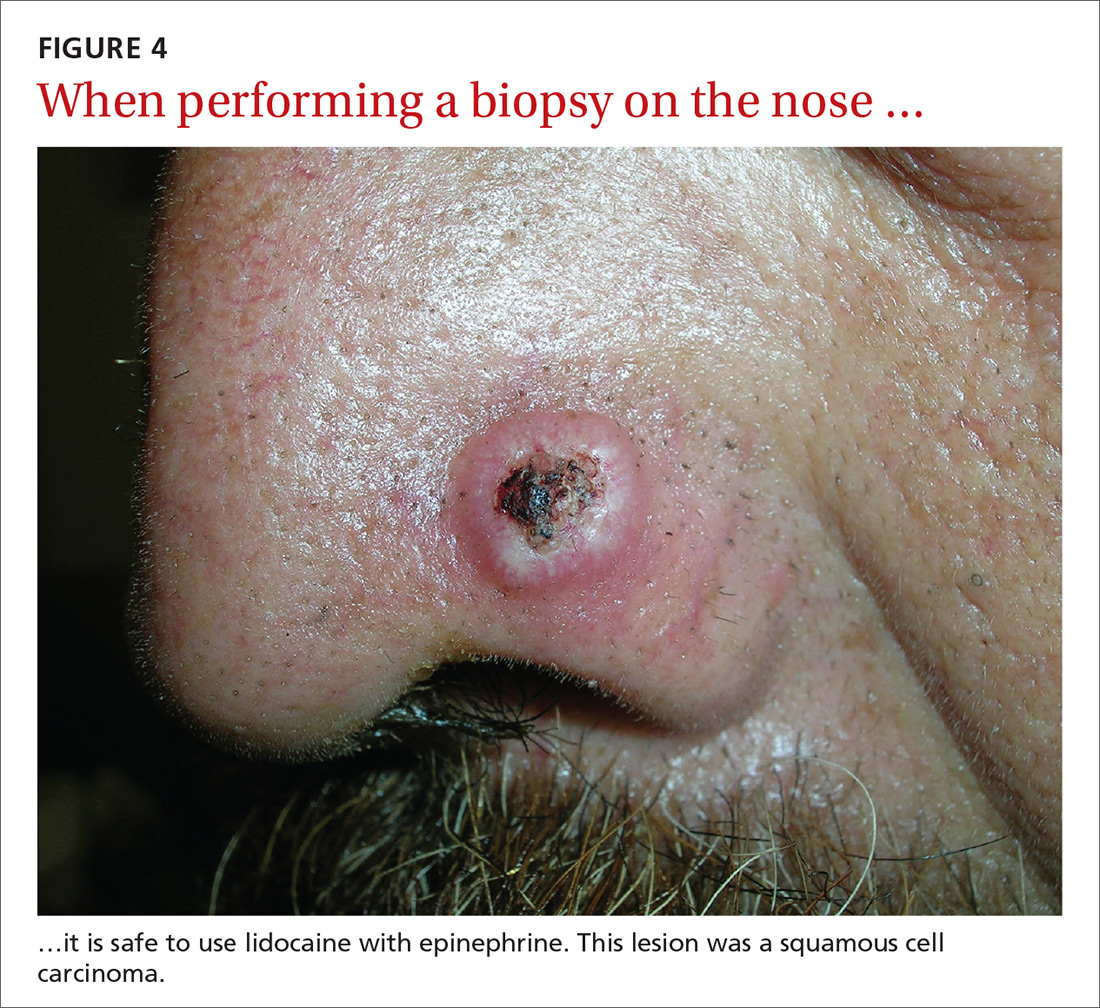

Epinephrine cannot be used for biopsies on the fingers, toes, nose, or penis.

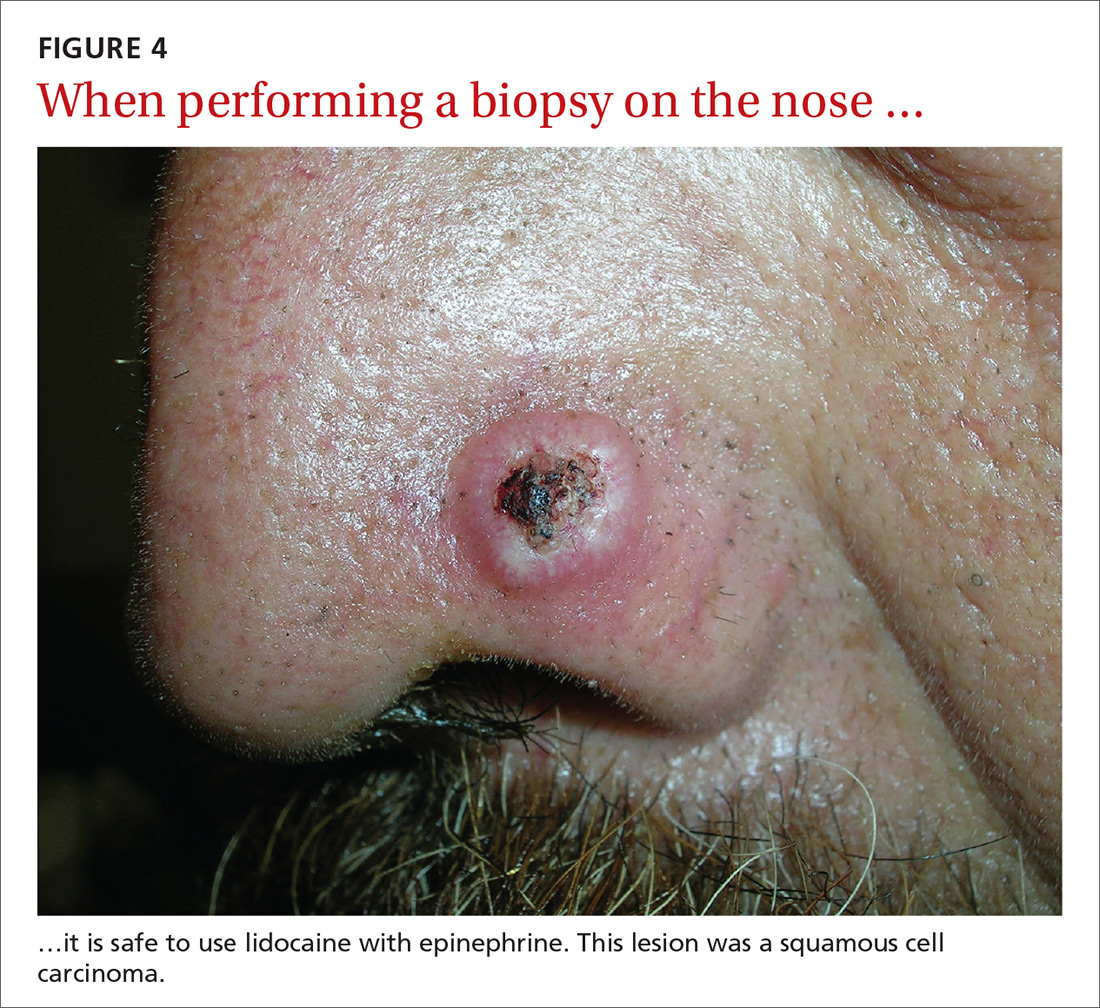

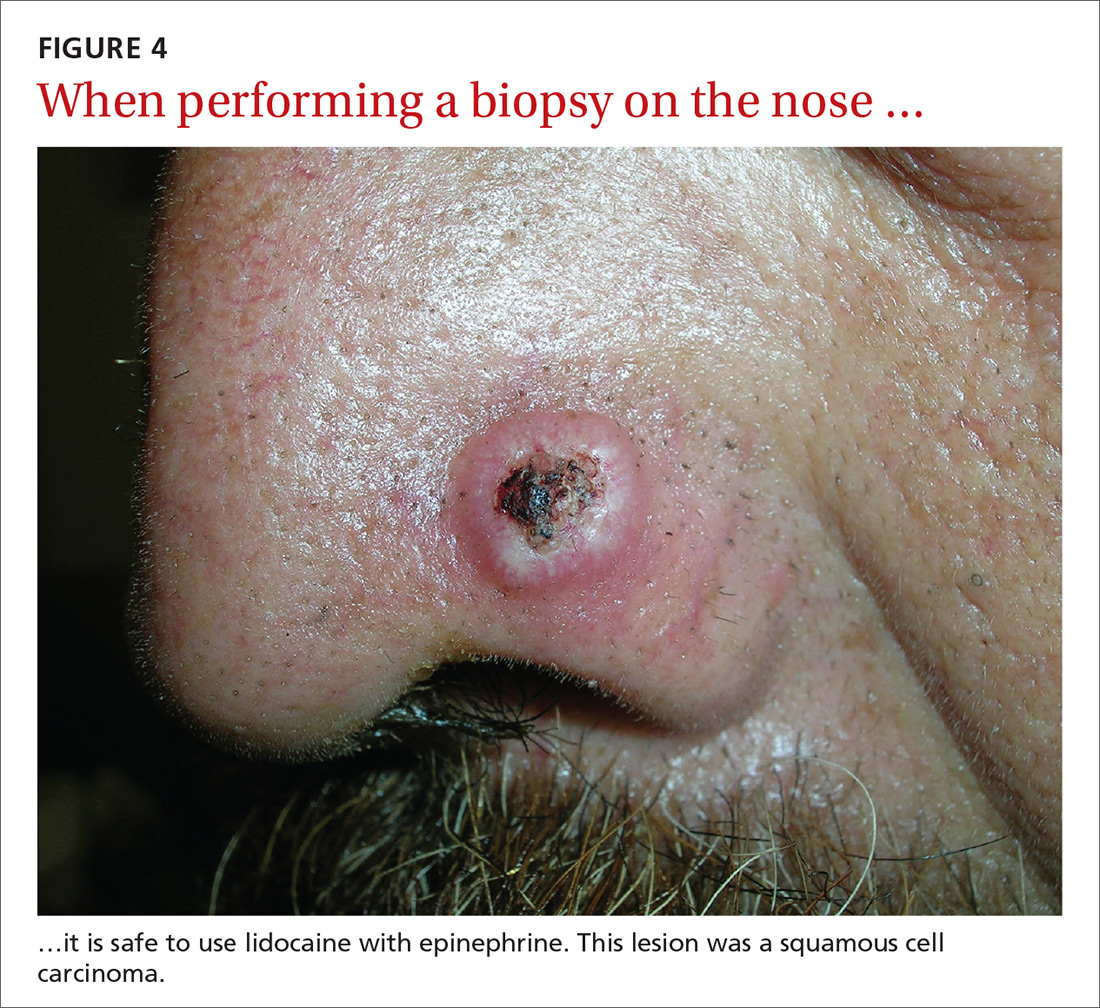

Lidocaine with epinephrine is safe to use in areas with end-arteries, such as the fingers, toes, nose (FIGURE 4), and penis. There is no evidence to support the notion that local anesthesia with vasoconstriction can cause necrosis in these areas, and no case of necrosis has been reported since the introduction of commercial lidocaine with epinephrine in 1948.18

In addition to an absence of complications, epinephrine supplementation results in a relatively bloodless operating field and longer effectiveness of local anesthesia, as a study of more than 10,000 ear and nose surgeries using epinephrine-supplemented local anesthetics showed.19 The relative absence of blood in the operating field significantly reduces the duration of surgery and increases the healing rate because less electrocautery is needed.19

Similarly, the addition of epinephrine in digital blocks minimizes the need for tourniquets and large volumes of anesthetic and provides better and longer pain control during procedures.20 This topic was addressed by Prabhakar et al in a Cochrane Review in 2015.21 While digital surgeries are common, there were only 4 randomized controlled studies addressing the use of epinephrine in digital blocks. In these studies, there were no reports of adverse events, such as ischemia distal to the injection site. Evidence suggests that epinephrine in digital blocks can even be used safely in patients with vascular disease.22

And while the use of epinephrine with lidocaine in sites with end-arteries is beneficial for hemostasis and does not seem to pose a risk of ischemia, it is prudent to use the smallest volume of epinephrine (with lidocaine) needed to achieve anesthesia for the site.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth V. Seiverling, MD, 300 Southborough Drive, Suite 201, South Portland, ME 04106; [email protected].

1. Kerr OA, Tidman MJ, Walker JJ, et al. The profile of dermatological problems in primary care. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:380-383.

2. Hosler GA, Patterson JW. Lentigines, nevi, and melanomas. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Elsevier; 2015:32,837-901.

3. Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Bichakjian CK, et al. Melanoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:250-275.

4. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer International Publishing; 2017;8:563-585.

5. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Implementation of AJCC 8th Edition Cancer Staging System. Available at: https://cancerstaging.org/About/news/Pages/Implementation-of-AJCC-8th-Edition-Cancer-Staging-System.aspx. Accessed April 2, 2018.

6. Karimipour DJ, Schwartz JL, Wang TS, et al. Microstaging accuracy after subtotal incisional biopsy of cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:798-802.

7. Kaiser S, Vassell R, Pinckney RG, et al. Clinical impact of biopsy method on the quality of surgical management in melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:775-779.

8. Montgomery BD, Sadler GM. Punch biopsy of pigmented lesions is potentially hazardous. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:24.

9. Ng JC, Swain S, Dowling JP, et al. The impact of partial biopsy on histopathologic diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: experience of an Australian tertiary referral service. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:234-239.

10. Gambichler T, Senger E, Rapp S, et al. Deep shave excision of macular melanocytic nevi with the razor blade biopsy technique. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:662-666.

11. Ferrandiz L, Moreno-Ramirez D, Camacho FM. Shave excision of common acquired melanocytic nevi: cosmetic outcome, recurrences, and complications. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(9 Pt 1):1112-1115.

12. D'souza G, Carey TE, William WN Jr, et al. Epidemiology of head and neck squamous cell cancer among HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:603-610.

13. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010.

14. Elston DM, Stratman EJ, Miller SJ, et al. Skin biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1-16.

15. Zager JS, Hochwald SN, Marzban SS, et al. Shave biopsy is a safe and accurate method for the initial evaluation of melanoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:454-460.

16. Chanda JJ, Callen JP. Adverse effect of melanoma incision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:519-522.

17. Noroozi N, Zakerolhosseini A. Computerized measurement of melanocytic tumor depth in skin histopathological images. Micron. 2015;77:44-56.

18. Nielsen LJ, Lumholt P, Hölmich LR. [Local anaesthesia with vasoconstrictor is safe to use in areas with end-arteries in fingers, toes, noses and ears]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2014;176(44).

19. Häfner HM, Röcken M, Breuninger H. Epinephrine-supplemented local anesthetics for ear and nose surgery: clinical use without complications in more than 10,000 surgical procedures. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:195-199.

20. Krunic AL, Wang LC, Soltani K, et al. Digital anesthesia with epinephrine: an old myth revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:755-759.

21. Prabhakar H, Rath S, Kalaivani M, et al. Adrenaline with lidocaine for digital nerve blocks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD010645.

22. Ilicki J. Safety of epinephrine in digital nerve blocks: a literature review. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:799-809.

Once it’s determined that a growth requires a biopsy, there is often uncertainty about which type of biopsy to perform. Insufficient knowledge of, and/or experience with, the various biopsy modalities may deter FPs from performing skin biopsies when they are indicated. To help fill the knowledge gaps and better position FPs to tackle skin cancer in its earliest stages, this article identifies and dispels 5 of the most common myths surrounding skin biopsies for the detection of basal and squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma.

MYTH #1

A punch biopsy is always preferred for suspected melanoma because it gets full depth.

A deep shave biopsy (saucerization)—not a punch biopsy—is usually the procedure of choice when biopsying a lesion suspected to be melanoma.2 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) "Melanoma Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology" state that an excisional biopsy (elliptical, punch, or saucerization) with a 1- to 3-mm margin is the preferred method of biopsy for suspected melanoma.3 However, a punch biopsy should be performed only if a 1- to 3-mm margin all around a suspected melanoma can be obtained. Otherwise, a saucerization or elliptical excision is preferred.3

The saucerization technique generally permits optimal sampling in terms of both the breadth and depth of the growth, providing the pathologist with sufficient tissue from both the epidermis and dermis (FIGURE 1).

Why are breadth/depth important? Breadth is important because showing the pathologist the epidermis (especially the edge) of a suspected melanocytic tumor allows for detection of pagetoid spread (upward movement through the epidermis) of melanocytes and of single melanocytes at the edge of a tumor. Single melanocytes at the edge of a tumor and pagetoid spread are histologic features of melanoma that help to distinguish these lesions from nevi, which tend to have nested melanocytes.2

Depth is important because it predicts prognosis and impacts management. For tumors 0.8 mm to 1 mm deep, a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) should be considered.3,4 Although the tumor depth threshold for a SLNB is still debated, most skin cancer experts in the United States agree that a melanoma thicker than 1 mm qualifies for this procedure. Some melanomas with high-risk features (such as ulceration) qualify for an SNLB even if they are <1 mm in depth.5 An SLNB provides prognostic information, and a positive SLNB directly affects staging.

[polldaddy:9990508]

Avoid partial biopsies. For tumors that have been partially biopsied with a punch or shallow shave biopsy, evaluation of the remaining neoplasm after subsequent excision leads to tumor upstaging in 21% of patients, with 10% qualifying for an SLNB.6 Thus, the goal should always be to obtain the entire depth of the tumor with the initial biopsy.

In addition, surgical margins are determined by primary tumor depth. To ensure a depth greater than 1 mm, aim to obtain a tissue specimen that is at least as thick as a dime (1.3 mm).

Because the goal is to avoid partial sampling, a challenge exists when the suspicious growth is large. Many melanomas are broader than a centimeter. And while punch biopsies ensure a depth of 1 mm or more, they risk missing the thickest portion of the tumor.7

Partial sampling of large melanocytic tumors with punch biopsies can lead to sampling error.8 Ng et al9 found there was a significant increase in histopathologic misdiagnosis with a punch biopsy of part of a melanoma (odds ratio [OR]=16.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 10-27; P<.001) and with shallow shave biopsy (OR=2.6; 95% CI, 1.2-5.7; P=.02) compared with excisional biopsy (including saucerization).9 Punch biopsy of part of a melanoma was also associated with increased odds of misdiagnosis with an adverse outcome (OR=20; 95% CI, 10-41; P<.001).

Punch biopsies do, however, offer a reasonable alternative when the melanoma is too broad for a complete saucerization. In these cases, consider multiple 4- to 6-mm punch biopsies to reduce the risk of sampling error.

Avoid performing punch biopsies <4 mm, as the breadth of tissue is inadequate. For example, even with dermoscopy, facial lentigo maligna melanoma is often difficult to differentiate from pigmented actinic keratosis and solar lentigines. (See JFP’s Watch and Learn Video on dermoscopy.) A broad shave biopsy is the preferred method of biopsy for lentigo maligna melanoma in situ according to the NCCN.3 And there have been several reports showing that the results of shave biopsies of melanocytic lesions are cosmetically acceptable to patients.10,11

If the biopsy confirms malignancy, a larger surgery with suturing will be needed. The most important issue to keep in mind is that if partial sampling leads to a benign diagnosis of a suspicious lesion, then the remainder of the lesion must be excised and sent for pathology.

Saucerization is also the preferred biopsy type for basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Studies have shown tumor depth is the most important factor in predicting metastasis of SCC, as well as tumor relapse rate, making accurate identification of the depth of the tumor important for both management and prognosis.12,13 Determining the thickness of the SCC is important for guiding management. SCC in situ is more amenable than invasive SCC to topical therapy or electrodesiccation and curettage.

What you’ll need. FPs can perform saucerization quickly and easily in the office during a standard 15-minute visit. Of course, it is essential to have all the necessary materials available. The key materials needed are lidocaine and epinephrine, a sharp razor blade such as a DermaBlade, and something for hemostasis (aluminum chloride and/or an electrosurgical instrument). Cotton-tipped applicators to apply the aluminum chloride and needles and syringes to administer the local anesthetic are also needed. (See JFP’s Watch and Learn Video on shave biopsy.) A quick saucerization eliminates the need for the patient to return for an elliptical excision and prevents a delayed diagnosis that can occur as a result of a long wait to see a dermatologist.

As a final note, the pathology order form should be completed with information on biopsy type, clinical presentation, differential diagnosis, and whether or not the full lesion was excised.

MYTH #2

A wide excisional biopsy is required for a suspected melanoma.

While complete excision of the entire tumor does allow the pathologist to evaluate the entire growth, wide (>3 mm) margins on the initial biopsy are not necessary. In fact, there are potential disadvantages to full excisional biopsy.

For example, seborrheic keratoses and other benign growths can mimic melanoma. Neither the physician nor the patient wants to learn that a large elliptical wound was created for a growth that turned out to be a benign seborrheic keratosis. Saucerization provides the pathologist with the entire lesion, and the resulting shallow wound heals as a round scar that is most often acceptable to patients.10,11,14 In addition, excisional biopsies carry a higher risk of infection than does saucerization.

Even when the index of suspicion is high for melanoma, a wide margin is not indicated. NCCN guidelines suggest that the margins around a suspected melanoma on initial biopsy not exceed 3 mm to avoid disrupting the accuracy of an SLNB (FIGURE 2).3

In addition, time constraints (elliptical excisional biopsies can take up to one hour, especially when a layered closure is performed) and a lack of surgical training may prohibit FPs from performing excisions.

One study found that while dermatologists prefer shave biopsies (80.5%), surgeons prefer excisional biopsies (46.3%) and primary care physicians prefer punch biopsies (44%) for biopsy of a growth suspicious for melanoma.7 In fact, of the biopsies FPs perform, only 29% are of the shave variety.7

However, deep shave biopsies can be performed quickly, with the whole process taking less than 5 minutes. We advocate performing them at the time of presentation, as the evidence shows that deep shave biopsies of suspected melanoma are reliable and accurate in 97% of cases.15

MYTH #3

A partial biopsy can make the cancer spread.

There is no evidence to support that a partial biopsy has any effect on the local recurrence or metastatic potential of malignant melanoma.16 In fact, a biopsy elicits an inflammatory response that activates the patient’s immune system and often causes tumor lysis. Some tumors may even resolve after biopsy. In our clinical practice, we have had several cases of basal cell carcinoma resolve after a biopsy without additional treatment.

MYTH #4

If after performing a deep shave biopsy, tumor or pigment remains, you must leave it because a second biopsy specimen can’t be added to the first.

If pigment is visible after an initial shave or punch biopsy, it is reasonable to obtain additional tissue from the base of the biopsy site. While the deeper tissue cannot be added to the initial specimen for the purposes of Breslow’s depth, it is still helpful for the pathologist to have the sample so that he or she can analyze the tumor cells in the dermis. (Melanoma tumor depth is measured as the maximum distance between malignant cells and the top of the granular layer.17) In these situations, be sure to let the pathologist know that there are 2 specimens in the container.

In general, it is valuable to get as much of the tissue as possible at the time of the initial biopsy. One way to avoid leaving tumor at the base of the biopsy is to look at

MYTH #5

Epinephrine cannot be used for biopsies on the fingers, toes, nose, or penis.

Lidocaine with epinephrine is safe to use in areas with end-arteries, such as the fingers, toes, nose (FIGURE 4), and penis. There is no evidence to support the notion that local anesthesia with vasoconstriction can cause necrosis in these areas, and no case of necrosis has been reported since the introduction of commercial lidocaine with epinephrine in 1948.18

In addition to an absence of complications, epinephrine supplementation results in a relatively bloodless operating field and longer effectiveness of local anesthesia, as a study of more than 10,000 ear and nose surgeries using epinephrine-supplemented local anesthetics showed.19 The relative absence of blood in the operating field significantly reduces the duration of surgery and increases the healing rate because less electrocautery is needed.19

Similarly, the addition of epinephrine in digital blocks minimizes the need for tourniquets and large volumes of anesthetic and provides better and longer pain control during procedures.20 This topic was addressed by Prabhakar et al in a Cochrane Review in 2015.21 While digital surgeries are common, there were only 4 randomized controlled studies addressing the use of epinephrine in digital blocks. In these studies, there were no reports of adverse events, such as ischemia distal to the injection site. Evidence suggests that epinephrine in digital blocks can even be used safely in patients with vascular disease.22

And while the use of epinephrine with lidocaine in sites with end-arteries is beneficial for hemostasis and does not seem to pose a risk of ischemia, it is prudent to use the smallest volume of epinephrine (with lidocaine) needed to achieve anesthesia for the site.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth V. Seiverling, MD, 300 Southborough Drive, Suite 201, South Portland, ME 04106; [email protected].

Once it’s determined that a growth requires a biopsy, there is often uncertainty about which type of biopsy to perform. Insufficient knowledge of, and/or experience with, the various biopsy modalities may deter FPs from performing skin biopsies when they are indicated. To help fill the knowledge gaps and better position FPs to tackle skin cancer in its earliest stages, this article identifies and dispels 5 of the most common myths surrounding skin biopsies for the detection of basal and squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma.

MYTH #1

A punch biopsy is always preferred for suspected melanoma because it gets full depth.

A deep shave biopsy (saucerization)—not a punch biopsy—is usually the procedure of choice when biopsying a lesion suspected to be melanoma.2 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) "Melanoma Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology" state that an excisional biopsy (elliptical, punch, or saucerization) with a 1- to 3-mm margin is the preferred method of biopsy for suspected melanoma.3 However, a punch biopsy should be performed only if a 1- to 3-mm margin all around a suspected melanoma can be obtained. Otherwise, a saucerization or elliptical excision is preferred.3

The saucerization technique generally permits optimal sampling in terms of both the breadth and depth of the growth, providing the pathologist with sufficient tissue from both the epidermis and dermis (FIGURE 1).

Why are breadth/depth important? Breadth is important because showing the pathologist the epidermis (especially the edge) of a suspected melanocytic tumor allows for detection of pagetoid spread (upward movement through the epidermis) of melanocytes and of single melanocytes at the edge of a tumor. Single melanocytes at the edge of a tumor and pagetoid spread are histologic features of melanoma that help to distinguish these lesions from nevi, which tend to have nested melanocytes.2

Depth is important because it predicts prognosis and impacts management. For tumors 0.8 mm to 1 mm deep, a sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) should be considered.3,4 Although the tumor depth threshold for a SLNB is still debated, most skin cancer experts in the United States agree that a melanoma thicker than 1 mm qualifies for this procedure. Some melanomas with high-risk features (such as ulceration) qualify for an SNLB even if they are <1 mm in depth.5 An SLNB provides prognostic information, and a positive SLNB directly affects staging.

[polldaddy:9990508]

Avoid partial biopsies. For tumors that have been partially biopsied with a punch or shallow shave biopsy, evaluation of the remaining neoplasm after subsequent excision leads to tumor upstaging in 21% of patients, with 10% qualifying for an SLNB.6 Thus, the goal should always be to obtain the entire depth of the tumor with the initial biopsy.

In addition, surgical margins are determined by primary tumor depth. To ensure a depth greater than 1 mm, aim to obtain a tissue specimen that is at least as thick as a dime (1.3 mm).

Because the goal is to avoid partial sampling, a challenge exists when the suspicious growth is large. Many melanomas are broader than a centimeter. And while punch biopsies ensure a depth of 1 mm or more, they risk missing the thickest portion of the tumor.7

Partial sampling of large melanocytic tumors with punch biopsies can lead to sampling error.8 Ng et al9 found there was a significant increase in histopathologic misdiagnosis with a punch biopsy of part of a melanoma (odds ratio [OR]=16.6; 95% confidence interval [CI], 10-27; P<.001) and with shallow shave biopsy (OR=2.6; 95% CI, 1.2-5.7; P=.02) compared with excisional biopsy (including saucerization).9 Punch biopsy of part of a melanoma was also associated with increased odds of misdiagnosis with an adverse outcome (OR=20; 95% CI, 10-41; P<.001).

Punch biopsies do, however, offer a reasonable alternative when the melanoma is too broad for a complete saucerization. In these cases, consider multiple 4- to 6-mm punch biopsies to reduce the risk of sampling error.

Avoid performing punch biopsies <4 mm, as the breadth of tissue is inadequate. For example, even with dermoscopy, facial lentigo maligna melanoma is often difficult to differentiate from pigmented actinic keratosis and solar lentigines. (See JFP’s Watch and Learn Video on dermoscopy.) A broad shave biopsy is the preferred method of biopsy for lentigo maligna melanoma in situ according to the NCCN.3 And there have been several reports showing that the results of shave biopsies of melanocytic lesions are cosmetically acceptable to patients.10,11

If the biopsy confirms malignancy, a larger surgery with suturing will be needed. The most important issue to keep in mind is that if partial sampling leads to a benign diagnosis of a suspicious lesion, then the remainder of the lesion must be excised and sent for pathology.

Saucerization is also the preferred biopsy type for basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs). Studies have shown tumor depth is the most important factor in predicting metastasis of SCC, as well as tumor relapse rate, making accurate identification of the depth of the tumor important for both management and prognosis.12,13 Determining the thickness of the SCC is important for guiding management. SCC in situ is more amenable than invasive SCC to topical therapy or electrodesiccation and curettage.

What you’ll need. FPs can perform saucerization quickly and easily in the office during a standard 15-minute visit. Of course, it is essential to have all the necessary materials available. The key materials needed are lidocaine and epinephrine, a sharp razor blade such as a DermaBlade, and something for hemostasis (aluminum chloride and/or an electrosurgical instrument). Cotton-tipped applicators to apply the aluminum chloride and needles and syringes to administer the local anesthetic are also needed. (See JFP’s Watch and Learn Video on shave biopsy.) A quick saucerization eliminates the need for the patient to return for an elliptical excision and prevents a delayed diagnosis that can occur as a result of a long wait to see a dermatologist.

As a final note, the pathology order form should be completed with information on biopsy type, clinical presentation, differential diagnosis, and whether or not the full lesion was excised.

MYTH #2

A wide excisional biopsy is required for a suspected melanoma.

While complete excision of the entire tumor does allow the pathologist to evaluate the entire growth, wide (>3 mm) margins on the initial biopsy are not necessary. In fact, there are potential disadvantages to full excisional biopsy.

For example, seborrheic keratoses and other benign growths can mimic melanoma. Neither the physician nor the patient wants to learn that a large elliptical wound was created for a growth that turned out to be a benign seborrheic keratosis. Saucerization provides the pathologist with the entire lesion, and the resulting shallow wound heals as a round scar that is most often acceptable to patients.10,11,14 In addition, excisional biopsies carry a higher risk of infection than does saucerization.

Even when the index of suspicion is high for melanoma, a wide margin is not indicated. NCCN guidelines suggest that the margins around a suspected melanoma on initial biopsy not exceed 3 mm to avoid disrupting the accuracy of an SLNB (FIGURE 2).3

In addition, time constraints (elliptical excisional biopsies can take up to one hour, especially when a layered closure is performed) and a lack of surgical training may prohibit FPs from performing excisions.

One study found that while dermatologists prefer shave biopsies (80.5%), surgeons prefer excisional biopsies (46.3%) and primary care physicians prefer punch biopsies (44%) for biopsy of a growth suspicious for melanoma.7 In fact, of the biopsies FPs perform, only 29% are of the shave variety.7

However, deep shave biopsies can be performed quickly, with the whole process taking less than 5 minutes. We advocate performing them at the time of presentation, as the evidence shows that deep shave biopsies of suspected melanoma are reliable and accurate in 97% of cases.15

MYTH #3

A partial biopsy can make the cancer spread.

There is no evidence to support that a partial biopsy has any effect on the local recurrence or metastatic potential of malignant melanoma.16 In fact, a biopsy elicits an inflammatory response that activates the patient’s immune system and often causes tumor lysis. Some tumors may even resolve after biopsy. In our clinical practice, we have had several cases of basal cell carcinoma resolve after a biopsy without additional treatment.

MYTH #4

If after performing a deep shave biopsy, tumor or pigment remains, you must leave it because a second biopsy specimen can’t be added to the first.

If pigment is visible after an initial shave or punch biopsy, it is reasonable to obtain additional tissue from the base of the biopsy site. While the deeper tissue cannot be added to the initial specimen for the purposes of Breslow’s depth, it is still helpful for the pathologist to have the sample so that he or she can analyze the tumor cells in the dermis. (Melanoma tumor depth is measured as the maximum distance between malignant cells and the top of the granular layer.17) In these situations, be sure to let the pathologist know that there are 2 specimens in the container.

In general, it is valuable to get as much of the tissue as possible at the time of the initial biopsy. One way to avoid leaving tumor at the base of the biopsy is to look at

MYTH #5

Epinephrine cannot be used for biopsies on the fingers, toes, nose, or penis.

Lidocaine with epinephrine is safe to use in areas with end-arteries, such as the fingers, toes, nose (FIGURE 4), and penis. There is no evidence to support the notion that local anesthesia with vasoconstriction can cause necrosis in these areas, and no case of necrosis has been reported since the introduction of commercial lidocaine with epinephrine in 1948.18

In addition to an absence of complications, epinephrine supplementation results in a relatively bloodless operating field and longer effectiveness of local anesthesia, as a study of more than 10,000 ear and nose surgeries using epinephrine-supplemented local anesthetics showed.19 The relative absence of blood in the operating field significantly reduces the duration of surgery and increases the healing rate because less electrocautery is needed.19

Similarly, the addition of epinephrine in digital blocks minimizes the need for tourniquets and large volumes of anesthetic and provides better and longer pain control during procedures.20 This topic was addressed by Prabhakar et al in a Cochrane Review in 2015.21 While digital surgeries are common, there were only 4 randomized controlled studies addressing the use of epinephrine in digital blocks. In these studies, there were no reports of adverse events, such as ischemia distal to the injection site. Evidence suggests that epinephrine in digital blocks can even be used safely in patients with vascular disease.22

And while the use of epinephrine with lidocaine in sites with end-arteries is beneficial for hemostasis and does not seem to pose a risk of ischemia, it is prudent to use the smallest volume of epinephrine (with lidocaine) needed to achieve anesthesia for the site.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth V. Seiverling, MD, 300 Southborough Drive, Suite 201, South Portland, ME 04106; [email protected].

1. Kerr OA, Tidman MJ, Walker JJ, et al. The profile of dermatological problems in primary care. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:380-383.

2. Hosler GA, Patterson JW. Lentigines, nevi, and melanomas. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Elsevier; 2015:32,837-901.

3. Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Bichakjian CK, et al. Melanoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:250-275.

4. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer International Publishing; 2017;8:563-585.

5. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Implementation of AJCC 8th Edition Cancer Staging System. Available at: https://cancerstaging.org/About/news/Pages/Implementation-of-AJCC-8th-Edition-Cancer-Staging-System.aspx. Accessed April 2, 2018.

6. Karimipour DJ, Schwartz JL, Wang TS, et al. Microstaging accuracy after subtotal incisional biopsy of cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:798-802.

7. Kaiser S, Vassell R, Pinckney RG, et al. Clinical impact of biopsy method on the quality of surgical management in melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:775-779.

8. Montgomery BD, Sadler GM. Punch biopsy of pigmented lesions is potentially hazardous. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:24.

9. Ng JC, Swain S, Dowling JP, et al. The impact of partial biopsy on histopathologic diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: experience of an Australian tertiary referral service. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:234-239.

10. Gambichler T, Senger E, Rapp S, et al. Deep shave excision of macular melanocytic nevi with the razor blade biopsy technique. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:662-666.

11. Ferrandiz L, Moreno-Ramirez D, Camacho FM. Shave excision of common acquired melanocytic nevi: cosmetic outcome, recurrences, and complications. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(9 Pt 1):1112-1115.

12. D'souza G, Carey TE, William WN Jr, et al. Epidemiology of head and neck squamous cell cancer among HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:603-610.

13. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010.

14. Elston DM, Stratman EJ, Miller SJ, et al. Skin biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1-16.

15. Zager JS, Hochwald SN, Marzban SS, et al. Shave biopsy is a safe and accurate method for the initial evaluation of melanoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:454-460.

16. Chanda JJ, Callen JP. Adverse effect of melanoma incision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:519-522.

17. Noroozi N, Zakerolhosseini A. Computerized measurement of melanocytic tumor depth in skin histopathological images. Micron. 2015;77:44-56.

18. Nielsen LJ, Lumholt P, Hölmich LR. [Local anaesthesia with vasoconstrictor is safe to use in areas with end-arteries in fingers, toes, noses and ears]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2014;176(44).

19. Häfner HM, Röcken M, Breuninger H. Epinephrine-supplemented local anesthetics for ear and nose surgery: clinical use without complications in more than 10,000 surgical procedures. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:195-199.

20. Krunic AL, Wang LC, Soltani K, et al. Digital anesthesia with epinephrine: an old myth revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:755-759.

21. Prabhakar H, Rath S, Kalaivani M, et al. Adrenaline with lidocaine for digital nerve blocks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD010645.

22. Ilicki J. Safety of epinephrine in digital nerve blocks: a literature review. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:799-809.

1. Kerr OA, Tidman MJ, Walker JJ, et al. The profile of dermatological problems in primary care. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2010;35:380-383.

2. Hosler GA, Patterson JW. Lentigines, nevi, and melanomas. In: Patterson JW, ed. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. Elsevier; 2015:32,837-901.

3. Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Bichakjian CK, et al. Melanoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:250-275.

4. Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. Springer International Publishing; 2017;8:563-585.

5. American Joint Committee on Cancer. Implementation of AJCC 8th Edition Cancer Staging System. Available at: https://cancerstaging.org/About/news/Pages/Implementation-of-AJCC-8th-Edition-Cancer-Staging-System.aspx. Accessed April 2, 2018.

6. Karimipour DJ, Schwartz JL, Wang TS, et al. Microstaging accuracy after subtotal incisional biopsy of cutaneous melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:798-802.

7. Kaiser S, Vassell R, Pinckney RG, et al. Clinical impact of biopsy method on the quality of surgical management in melanoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:775-779.

8. Montgomery BD, Sadler GM. Punch biopsy of pigmented lesions is potentially hazardous. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55:24.

9. Ng JC, Swain S, Dowling JP, et al. The impact of partial biopsy on histopathologic diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma: experience of an Australian tertiary referral service. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:234-239.

10. Gambichler T, Senger E, Rapp S, et al. Deep shave excision of macular melanocytic nevi with the razor blade biopsy technique. Dermatol Surg. 2000;26:662-666.

11. Ferrandiz L, Moreno-Ramirez D, Camacho FM. Shave excision of common acquired melanocytic nevi: cosmetic outcome, recurrences, and complications. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31(9 Pt 1):1112-1115.

12. D'souza G, Carey TE, William WN Jr, et al. Epidemiology of head and neck squamous cell cancer among HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:603-610.

13. Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Handbook. 7th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2010.

14. Elston DM, Stratman EJ, Miller SJ, et al. Skin biopsy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:1-16.

15. Zager JS, Hochwald SN, Marzban SS, et al. Shave biopsy is a safe and accurate method for the initial evaluation of melanoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:454-460.

16. Chanda JJ, Callen JP. Adverse effect of melanoma incision. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:519-522.

17. Noroozi N, Zakerolhosseini A. Computerized measurement of melanocytic tumor depth in skin histopathological images. Micron. 2015;77:44-56.

18. Nielsen LJ, Lumholt P, Hölmich LR. [Local anaesthesia with vasoconstrictor is safe to use in areas with end-arteries in fingers, toes, noses and ears]. Ugeskr Laeger. 2014;176(44).

19. Häfner HM, Röcken M, Breuninger H. Epinephrine-supplemented local anesthetics for ear and nose surgery: clinical use without complications in more than 10,000 surgical procedures. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2005;3:195-199.

20. Krunic AL, Wang LC, Soltani K, et al. Digital anesthesia with epinephrine: an old myth revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:755-759.

21. Prabhakar H, Rath S, Kalaivani M, et al. Adrenaline with lidocaine for digital nerve blocks. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD010645.

22. Ilicki J. Safety of epinephrine in digital nerve blocks: a literature review. J Emerg Med. 2015;49:799-809.

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2018;67(5):270-274.

Diffuse erythematous rash resistant to treatment

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of diffuse redness, itching, and tenderness of her skin. The patient said the eruption began 4 months earlier as localized plaques on her scalp, elbows, and beneath both breasts. Over the course of a few days, the redness became more diffuse, affecting most of her body. She also noticed swelling and skin desquamation on her lower extremities.

The patient had visited multiple urgent care clinics and underwent several courses of prednisone with initial improvement of symptoms, but experienced recurrence shortly after finishing the tapers.

On physical examination, more than 95% of the patient’s skin was bright red and tender to the touch, with associated exfoliation (FIGURES 1A-1B). Her lower extremities had pitting edema with superficial erosions that were weeping serous fluid. She was afebrile and normotensive, but had shaking chills and was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 115 bpm. There was no nail pitting, pustules, or lymphadenopathy. Lab tests revealed a low albumin level of 2.2 g/dL (normal: 3.5-5.5 g/dL), an elevated white blood cell count of 14,700 cells/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000 cells/mcL), and normocytic anemia (low hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL; normal: 12-15.5 g/dL). The patient was admitted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythroderma

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed severe erythroderma secondary to psoriasis. A punch biopsy was performed, and pathology demonstrated subacute spongiotic dermatitis with superficial neutrophilic infiltrates, consistent with psoriasis.

Erythroderma is widespread reddening of the skin associated with desquamation, typically involving more than 90% of the body’s surface area.1 In most instances, erythroderma is a clinical presentation of an existing dermatosis. The most common causative conditions include primary skin disorders (such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis), idiopathic erythroderma, and drug eruptions. Less common causes include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and contact dermatitis.1

It’s unclear why some skin diseases progress to erythroderma; the pathogenesis is complicated and involves keratinocytes and lymphocytes interacting with adhesion molecules and cytokines. Erythroderma can arise at any age and occurs in all races, but is more common in males and older adults, with a mean age of 42 to 61 years.2 The annual incidence of erythroderma is estimated to be one per 100,000 adults.3

A complete picture of the patient is essential to making the diagnosis

Diagnosis can be difficult and hinges on historical and physical exam findings, as well as lab evaluations and skin biopsies. The history should focus on current and former medications, while the physical exam should hone in on clinical manifestations of existing dermatoses. The most common extracutaneous finding is generalized lymphadenopathy, which if prominent, may warrant lymph node biopsy, with studies for evaluation of underlying lymphoma.

Tachycardia develops in 40% of patients, secondary to increased blood flow to the skin and fluid loss, with risk of high-output cardiac failure.2 Patients often have chills because their skin is not able to regulate their body temperature normally.4

The lab evaluation should include a complete blood count with differential and a comprehensive metabolic panel, as well as blood, skin, and urine cultures if infection is suspected as an inciting factor. Typical findings include mild anemia, leukocytosis, eosinophilia, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate.5 In addition, patients with chronic erythroderma commonly have low albumin.6 Unfortunately, lab studies don’t always reveal the underlying cause of the erythroderma.

Biopsies are commonly performed. However, the underlying etiology is often not clearly reflected in the result. Histology is typically nonspecific; findings frequently include hyperkeratosis, acanthosis, spongiosis, and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate. Additionally, the prominence of histologic features may vary depending on the stage of disease and the severity of inflammation. More specific findings may become evident later in the disease as the erythroderma clears, so repeated skin biopsies over time may be needed for diagnosis.7

Consider these conditions, which can lead to erythroderma

First and foremost, it is important to get a thorough history, particularly about prior skin conditions and symptoms that may indicate the presence of undiagnosed skin conditions.

Psoriasis is one of the most common causes of erythroderma. A history of pre-existing psoriasis is very helpful, but when this is not present, a biopsy can help confirm a clinical suspicion for psoriasis. It also helps to look for clues of psoriasis like nail changes or a history of plaques over the elbows and knees.

Atopic dermatitis is another common cause of erythroderma, and the history might include scaling and erythematous patches or plaques involving flexural surfaces before erythroderma occurs. Patients may have a history of atopic dermatitis from childhood and/or a history of other atopic conditions such as asthma and allergic rhinitis.

Drug eruptions occur following the administration of a new medication and can mimic a myriad of dermatoses.

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma can lead to erythroderma and be differentiated with skin biopsy; pathology may show atypical lymphocytes, and Pautrier’s microabscesses may be seen.8

Pityriasis rubra pilaris is a relatively rare condition that presents with red-orange scaling patches and thickened yellowish palms and soles.9

Tx targets underlying etiology and associated complications

When treating a patient with erythroderma, it’s important to prevent hypothermia and secondary infections. If symptoms are severe, hospitalization should be considered. Nutrition should be assessed, and any fluid or electrolyte imbalances should be corrected.

Oral antihistamines are commonly administered to suppress associated pruritus. Topical treatment usually consists of corticosteroids under occlusion with bland emollients. Depending upon the underlying disease, the following systemic medications may be started: methotrexate 7.5 to 15 mg once/week; acitretin 10 to 25 mg/d; or cyclosporine 2.5 to 5 mg/kg/d; in addition to topical treatment.4

Our patient. Pathology for our patient was indicative of psoriasis. She was started on a regimen of cyclosporine 4 to 5 mg/kg/d, diphenhydramine 25 to 50 mg as needed for itching, triamcinolone 0.1% ointment under wet wraps to her trunk and extremities, and hydrocortisone 2.5% ointment to be applied to her face daily. She was released after 5 days in the hospital. At outpatient follow-up one week later, her erythroderma was resolving. One month later, her erythroderma was resolved (FIGURE 2), although she did have psoriatic plaques on her lower legs.

CORRESPONDENCE

Richard P. Usatine, MD, University of Texas Health San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Dr., San Antonio, TX 78229; [email protected].

1. Keisham C, Sahoo B, Khurana N, et al. Clinicopathologic study of erythroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:AB85.

2. Li J, Zheng H-Y. Erythroderma: a clinical and prognostic study. Dermatology. 2012;225:154-162.

3. Sigurdsson V, Steegmans PH, van Vioten WA. The incidence of erythroderma: a survey among all dermatologists in The Netherlands. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:675-678.

4. Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Duncan K, et al. Dermatology essentials. 1st ed. Oxford, England: Elsevier Saunders; 2014.

5. Karakayli G, Beckham G, Orengo I, et al. Exfoliative dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:625-630.

6. Rothe MJ, Bialy TL, Grant-Kels JM. Erythroderma. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18:405-415.

7. Walsh NM, Prokopetz R, Tron VA, et al. Histopathology in erythroderma: review of a series of cases by multiple observers. J Cutan Pathol. 1994;21:419-423.

8. Jawed SI, Myskowski PL, Horwitz S, et al. Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome): part I. Diagnosis: clinical and histopathologic features and new molecular and biologic markers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:205.e1-e16.

9. Abdel-Azim NE, Ismail SA, Fathy E. Differentiation of pityriasis rubra pilaris from plaque psoriasis by dermoscopy. Arch Dermatol Res. 2017;309:311-314.

A 39-year-old woman presented to the emergency department for evaluation of diffuse redness, itching, and tenderness of her skin. The patient said the eruption began 4 months earlier as localized plaques on her scalp, elbows, and beneath both breasts. Over the course of a few days, the redness became more diffuse, affecting most of her body. She also noticed swelling and skin desquamation on her lower extremities.

The patient had visited multiple urgent care clinics and underwent several courses of prednisone with initial improvement of symptoms, but experienced recurrence shortly after finishing the tapers.

On physical examination, more than 95% of the patient’s skin was bright red and tender to the touch, with associated exfoliation (FIGURES 1A-1B). Her lower extremities had pitting edema with superficial erosions that were weeping serous fluid. She was afebrile and normotensive, but had shaking chills and was tachycardic, with a heart rate of 115 bpm. There was no nail pitting, pustules, or lymphadenopathy. Lab tests revealed a low albumin level of 2.2 g/dL (normal: 3.5-5.5 g/dL), an elevated white blood cell count of 14,700 cells/mcL (normal: 4500-11,000 cells/mcL), and normocytic anemia (low hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL; normal: 12-15.5 g/dL). The patient was admitted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Erythroderma

Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, we diagnosed severe erythroderma secondary to psoriasis. A punch biopsy was performed, and pathology demonstrated subacute spongiotic dermatitis with superficial neutrophilic infiltrates, consistent with psoriasis.

Erythroderma is widespread reddening of the skin associated with desquamation, typically involving more than 90% of the body’s surface area.1 In most instances, erythroderma is a clinical presentation of an existing dermatosis. The most common causative conditions include primary skin disorders (such as psoriasis or atopic dermatitis), idiopathic erythroderma, and drug eruptions. Less common causes include cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, pityriasis rubra pilaris, and contact dermatitis.1