User login

Pseudoglandular Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer. Pseudoglandular SCC, also known as adenoid SCC or acantholytic SCC, is an uncommon variant that was first described by Lever1 in 1947 as an adenoacanthoma of the sweat glands. Of the many variants of SCC, pseudoglandular SCC generally is considered to behave aggressively with intermediate (3%–10%) risk for metastasis.2 The metastatic potential of pseudoglandular SCC may be conferred in part by diminished expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, including desmoglein 3, epithelial cadherin, and syn-decan 1.3,4 Pseudoglandular SCC presents most often on sun-damaged skin of elderly patients, especially the face and ears, as a pink or red nodule with central ulceration and a raised indurated border. It may be mistaken clinically for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or keratoacanthoma.

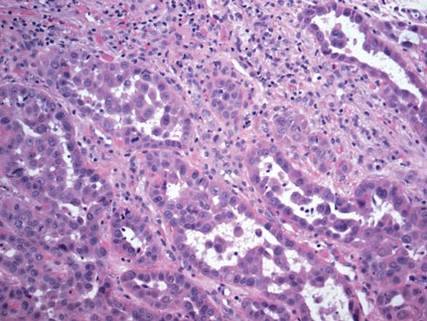

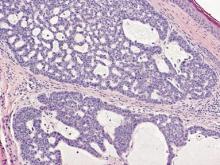

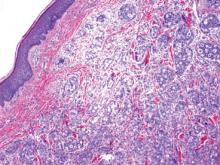

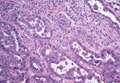

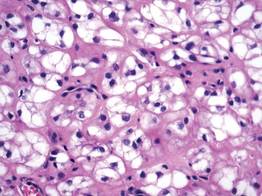

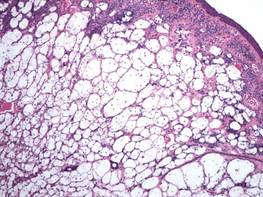

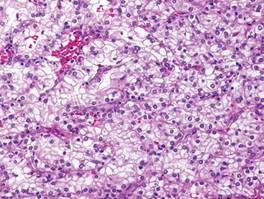

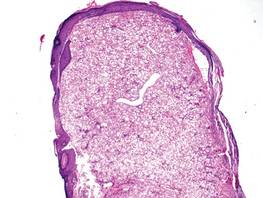

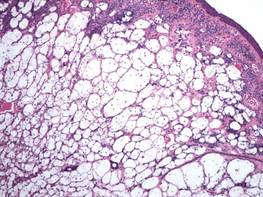

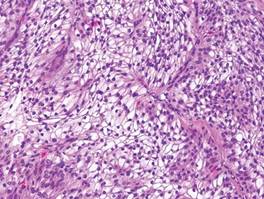

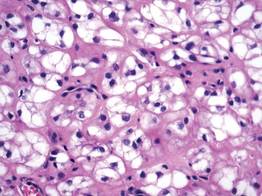

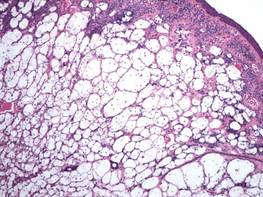

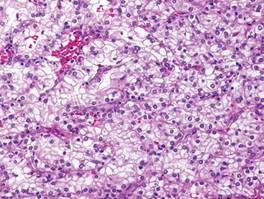

On microscopic examination, the lesion is predominantly located in the dermis and may extend to the subcutis. There usually is connection to the overlying epidermis, which often shows hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Epidermal squamous dysplasia may be present. The dermis typically contains nests of squamous cells with a variable degree of central acantholysis. The morphology on low-power magnification consists of tubules of irregular size and shape, which are present either focally or throughout the lesion (Figure 1). The tubules are typically admixed with foci of keratinization. One or more layers of cohesive cells line the tubules. Partial keratinization may be found in the lining of tubules with more than 1 cell layer. The tumor cells are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm, ovoid hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses are common. The tubular lumina are filled with acantholytic cells, either singly or in small clusters, which may demonstrate residual bridging to tubular lining cells (Figure 2). The acantholytic cells show some variability in size and may be large, multinucleated, or keratinized. The tubules may contain material that is amorphous, basophilic, periodic acid–Schiff positive, diastase sensitive, and mucicarmine negative.5 Eccrine ducts at the periphery of the tumor may show reactive dilatation and proliferation. Tumor cells show positive immunostaining for epithelial membrane antigen, 34βE12, CK5/6, and tumor protein p63.6-8 There is negative immunostaining for carcinoembryonic antigen, amylase, S-100 protein, and factor VIII.5

|

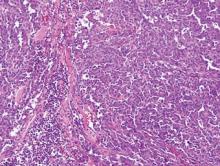

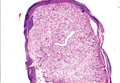

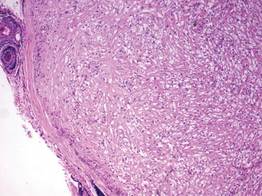

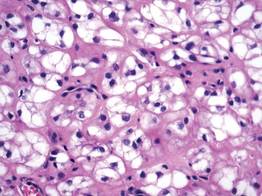

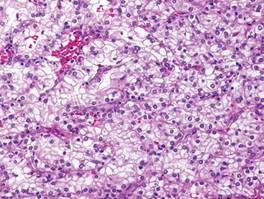

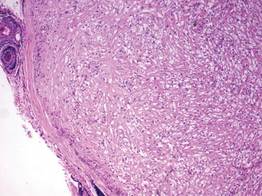

The differential diagnosis includes adenoid BCC, angiosarcoma, eccrine carcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin. In adenoid BCC, excess stromal mucin imparts pseudoglandular architecture (Figure 3). However, features of conventional BCC, including peripheral nuclear palisading and retraction artifact often are present as well.

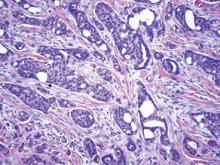

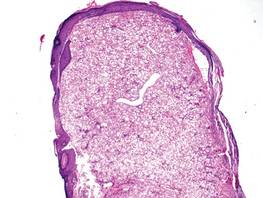

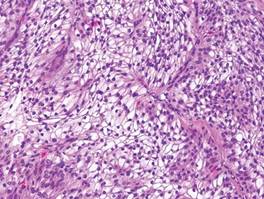

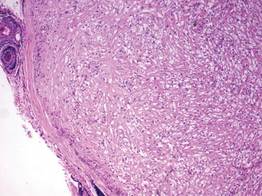

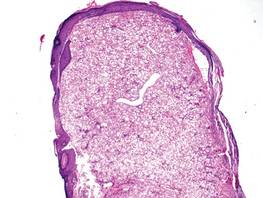

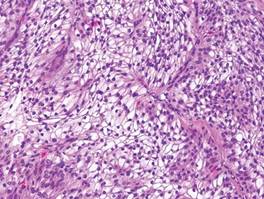

Angiosarcoma shows slitlike vascular spaces lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells (Figure 4). Further, there is positive immunostaining for vascular markers CD31 and CD34.

In eccrine carcinoma, there are invasive ductal structures lined by either a single or double layer of cells that may contain luminal material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 5).9 The tumor cells show positive immunostaining for cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and S-100 protein.10

Pseudoglandular SCC is susceptible to misdiagnosis as adenocarcinoma by sampling error if biopsies do not capture areas with typical features of SCC, including dysplastic squamous epithelium and keratinization. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin is more likely to present with multiple nodules in older individuals. Lack of epidermal connection of the tumor and minimal to no acantholytic dyskeratosis further support cutaneous metastasis (Figure 6). Review of the patient’s clinical history might be helpful if adenocarcinoma was previously diagnosed. Immunohistochemical evaluation may aid in the prediction of the primary site in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin.11

1. Lever WF. Adenocanthoma of sweat glands; carcinoma of sweat glands with glandular and epidermal elements: report of four cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1947;56:157-171.

2. Bonerandi JJ, Beauvillain C, Caquant L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 5):1-51.

3. Griffin JR, Wriston CC, Peters MS, et al. Decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma compared with invasive well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:442-447.

4. Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The expression of syndecan-1 is preferentially reduced compared with that of E-cadherin in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:83-89.

5. Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:114-121.

6. Sajin M, Hodorogea Prisăcaru A, Luchian MC, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma: pathological study of nine cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:279-283.

7. Gray Y, Robidoux HJ, Farrell DS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma detected by high-molecular-weight cytokeratin immunostaining mimicking atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:799-802.

8. Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

9. Plaza JA, Prieto VG. Neoplastic Lesions of the Skin. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2014.

10. Swanson PE, Cherwitz DL, Neumann MP, et al. Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma: an histologic and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:65-86.

11. Dennis JL, Hvidsten TR, Wit EC, et al. Markers of adenocarcinoma characteristic of the site of origin: development of a diagnostic algorithm. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3766-3772.

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer. Pseudoglandular SCC, also known as adenoid SCC or acantholytic SCC, is an uncommon variant that was first described by Lever1 in 1947 as an adenoacanthoma of the sweat glands. Of the many variants of SCC, pseudoglandular SCC generally is considered to behave aggressively with intermediate (3%–10%) risk for metastasis.2 The metastatic potential of pseudoglandular SCC may be conferred in part by diminished expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, including desmoglein 3, epithelial cadherin, and syn-decan 1.3,4 Pseudoglandular SCC presents most often on sun-damaged skin of elderly patients, especially the face and ears, as a pink or red nodule with central ulceration and a raised indurated border. It may be mistaken clinically for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or keratoacanthoma.

On microscopic examination, the lesion is predominantly located in the dermis and may extend to the subcutis. There usually is connection to the overlying epidermis, which often shows hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Epidermal squamous dysplasia may be present. The dermis typically contains nests of squamous cells with a variable degree of central acantholysis. The morphology on low-power magnification consists of tubules of irregular size and shape, which are present either focally or throughout the lesion (Figure 1). The tubules are typically admixed with foci of keratinization. One or more layers of cohesive cells line the tubules. Partial keratinization may be found in the lining of tubules with more than 1 cell layer. The tumor cells are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm, ovoid hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses are common. The tubular lumina are filled with acantholytic cells, either singly or in small clusters, which may demonstrate residual bridging to tubular lining cells (Figure 2). The acantholytic cells show some variability in size and may be large, multinucleated, or keratinized. The tubules may contain material that is amorphous, basophilic, periodic acid–Schiff positive, diastase sensitive, and mucicarmine negative.5 Eccrine ducts at the periphery of the tumor may show reactive dilatation and proliferation. Tumor cells show positive immunostaining for epithelial membrane antigen, 34βE12, CK5/6, and tumor protein p63.6-8 There is negative immunostaining for carcinoembryonic antigen, amylase, S-100 protein, and factor VIII.5

|

The differential diagnosis includes adenoid BCC, angiosarcoma, eccrine carcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin. In adenoid BCC, excess stromal mucin imparts pseudoglandular architecture (Figure 3). However, features of conventional BCC, including peripheral nuclear palisading and retraction artifact often are present as well.

Angiosarcoma shows slitlike vascular spaces lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells (Figure 4). Further, there is positive immunostaining for vascular markers CD31 and CD34.

In eccrine carcinoma, there are invasive ductal structures lined by either a single or double layer of cells that may contain luminal material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 5).9 The tumor cells show positive immunostaining for cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and S-100 protein.10

Pseudoglandular SCC is susceptible to misdiagnosis as adenocarcinoma by sampling error if biopsies do not capture areas with typical features of SCC, including dysplastic squamous epithelium and keratinization. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin is more likely to present with multiple nodules in older individuals. Lack of epidermal connection of the tumor and minimal to no acantholytic dyskeratosis further support cutaneous metastasis (Figure 6). Review of the patient’s clinical history might be helpful if adenocarcinoma was previously diagnosed. Immunohistochemical evaluation may aid in the prediction of the primary site in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin.11

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer. Pseudoglandular SCC, also known as adenoid SCC or acantholytic SCC, is an uncommon variant that was first described by Lever1 in 1947 as an adenoacanthoma of the sweat glands. Of the many variants of SCC, pseudoglandular SCC generally is considered to behave aggressively with intermediate (3%–10%) risk for metastasis.2 The metastatic potential of pseudoglandular SCC may be conferred in part by diminished expression of intercellular adhesion molecules, including desmoglein 3, epithelial cadherin, and syn-decan 1.3,4 Pseudoglandular SCC presents most often on sun-damaged skin of elderly patients, especially the face and ears, as a pink or red nodule with central ulceration and a raised indurated border. It may be mistaken clinically for basal cell carcinoma (BCC) or keratoacanthoma.

On microscopic examination, the lesion is predominantly located in the dermis and may extend to the subcutis. There usually is connection to the overlying epidermis, which often shows hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. Epidermal squamous dysplasia may be present. The dermis typically contains nests of squamous cells with a variable degree of central acantholysis. The morphology on low-power magnification consists of tubules of irregular size and shape, which are present either focally or throughout the lesion (Figure 1). The tubules are typically admixed with foci of keratinization. One or more layers of cohesive cells line the tubules. Partial keratinization may be found in the lining of tubules with more than 1 cell layer. The tumor cells are polygonal with eosinophilic cytoplasm, ovoid hyperchromatic or vesicular nuclei, and prominent nucleoli. Mitoses are common. The tubular lumina are filled with acantholytic cells, either singly or in small clusters, which may demonstrate residual bridging to tubular lining cells (Figure 2). The acantholytic cells show some variability in size and may be large, multinucleated, or keratinized. The tubules may contain material that is amorphous, basophilic, periodic acid–Schiff positive, diastase sensitive, and mucicarmine negative.5 Eccrine ducts at the periphery of the tumor may show reactive dilatation and proliferation. Tumor cells show positive immunostaining for epithelial membrane antigen, 34βE12, CK5/6, and tumor protein p63.6-8 There is negative immunostaining for carcinoembryonic antigen, amylase, S-100 protein, and factor VIII.5

|

The differential diagnosis includes adenoid BCC, angiosarcoma, eccrine carcinoma, and metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin. In adenoid BCC, excess stromal mucin imparts pseudoglandular architecture (Figure 3). However, features of conventional BCC, including peripheral nuclear palisading and retraction artifact often are present as well.

Angiosarcoma shows slitlike vascular spaces lined by hyperchromatic endothelial cells (Figure 4). Further, there is positive immunostaining for vascular markers CD31 and CD34.

In eccrine carcinoma, there are invasive ductal structures lined by either a single or double layer of cells that may contain luminal material that is periodic acid–Schiff positive and diastase resistant (Figure 5).9 The tumor cells show positive immunostaining for cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and S-100 protein.10

Pseudoglandular SCC is susceptible to misdiagnosis as adenocarcinoma by sampling error if biopsies do not capture areas with typical features of SCC, including dysplastic squamous epithelium and keratinization. Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin is more likely to present with multiple nodules in older individuals. Lack of epidermal connection of the tumor and minimal to no acantholytic dyskeratosis further support cutaneous metastasis (Figure 6). Review of the patient’s clinical history might be helpful if adenocarcinoma was previously diagnosed. Immunohistochemical evaluation may aid in the prediction of the primary site in patients with metastatic adenocarcinoma of unknown origin.11

1. Lever WF. Adenocanthoma of sweat glands; carcinoma of sweat glands with glandular and epidermal elements: report of four cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1947;56:157-171.

2. Bonerandi JJ, Beauvillain C, Caquant L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 5):1-51.

3. Griffin JR, Wriston CC, Peters MS, et al. Decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma compared with invasive well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:442-447.

4. Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The expression of syndecan-1 is preferentially reduced compared with that of E-cadherin in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:83-89.

5. Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:114-121.

6. Sajin M, Hodorogea Prisăcaru A, Luchian MC, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma: pathological study of nine cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:279-283.

7. Gray Y, Robidoux HJ, Farrell DS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma detected by high-molecular-weight cytokeratin immunostaining mimicking atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:799-802.

8. Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

9. Plaza JA, Prieto VG. Neoplastic Lesions of the Skin. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2014.

10. Swanson PE, Cherwitz DL, Neumann MP, et al. Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma: an histologic and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:65-86.

11. Dennis JL, Hvidsten TR, Wit EC, et al. Markers of adenocarcinoma characteristic of the site of origin: development of a diagnostic algorithm. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3766-3772.

1. Lever WF. Adenocanthoma of sweat glands; carcinoma of sweat glands with glandular and epidermal elements: report of four cases. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1947;56:157-171.

2. Bonerandi JJ, Beauvillain C, Caquant L, et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma and precursor lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25(suppl 5):1-51.

3. Griffin JR, Wriston CC, Peters MS, et al. Decreased expression of intercellular adhesion molecules in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma compared with invasive well-differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:442-447.

4. Bayer-Garner IB, Smoller BR. The expression of syndecan-1 is preferentially reduced compared with that of E-cadherin in acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:83-89.

5. Nappi O, Pettinato G, Wick MR. Adenoid (acantholytic) squamous cell carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 1989;16:114-121.

6. Sajin M, Hodorogea Prisăcaru A, Luchian MC, et al. Acantholytic squamous cell carcinoma: pathological study of nine cases with review of literature. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:279-283.

7. Gray Y, Robidoux HJ, Farrell DS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma detected by high-molecular-weight cytokeratin immunostaining mimicking atypical fibroxanthoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:799-802.

8. Kanitakis J, Chouvet B. Expression of p63 in cutaneous metastases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2007;128:753-758.

9. Plaza JA, Prieto VG. Neoplastic Lesions of the Skin. New York, NY: Demos Medical Publishing; 2014.

10. Swanson PE, Cherwitz DL, Neumann MP, et al. Eccrine sweat gland carcinoma: an histologic and immunohistochemical study of 32 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1987;14:65-86.

11. Dennis JL, Hvidsten TR, Wit EC, et al. Markers of adenocarcinoma characteristic of the site of origin: development of a diagnostic algorithm. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:3766-3772.

Clear Cell Fibrous Papule

A fibrous papule is a common benign lesion that usually presents in adults on the face, especially on the lower portion of the nose. It typically presents as a small (2–5 mm), asymptomatic, flesh-colored, dome-shaped lesion that is firm and nontender. Several histopathologic variants of fibrous papules have been described, including clear cell, granular, epithelioid, hypercellular, pleomorphic, pigmented, and inflammatory.1 Clear cell fibrous papules are exceedingly rare. On microscopic examination the epidermis may be normal or show some degree of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, erosion, ulceration, or crust. The basal layer may show an increase of melanin. The dermis is expanded by a proliferation of clear cells arranged in sheets, clusters, or as single cells (Figure 1). The clear cells show variation in size and shape. The nuclei are small and round without pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, or mitoses. The nuclei may be centrally located or eccentrically displaced by a large intracytoplasmic vacuole (Figure 2). Some clear cells may exhibit finely vacuolated cytoplasm with nuclear scalloping. The surrounding stroma usually consists of sclerotic collagen and dilated blood vessels (Figure 3). Extravasated red blood cells may be present focally. Patchy lymphocytic infiltrates may be found in the stroma at the periphery of the lesion. Periodic acid–Schiff and mucicarmine staining of the clear cells is negative. On immunohistochemistry, the clear cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and HMB-45 (human melanoma black 45).2,3 The clear cells often are positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, and NKI/C3 (anti-CD63) but also may be negative. The S-100 protein often is negative but may be focally positive.

The differential diagnosis for clear cell fibrous papules is broad but reasonably includes balloon cell nevus, clear cell hidradenoma, and cutaneous metastasis of clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Balloon cell malignant melanoma is not considered strongly in the differential diagnosis because it usually exhibits invasive growth, cytologic atypia, and mitoses, all of which are not characteristic morphologic features of clear cell fibrous papules.

A balloon cell nevus may be difficult to distinguish from a clear cell fibrous papule on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4); however, the nuclei of a balloon cell nevus tend to be more rounded and centrally located. Any junctional nesting or nests of conventional nevus cells in the dermis also help differentiate a balloon cell nevus from a clear cell fibrous papule. Diffusely positive immunostaining for S-100 protein also is indicative of a balloon cell nevus.

Clear cell hidradenoma consists predominantly of cells with clear cytoplasm and small dark nuclei that may closely mimic a clear cell fibrous papule (Figure 5) but often shows a second population of cells with more vesicular nuclei and dark eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cystic spaces containing hyaline material and foci of squamoid change are common, along with occasional tubular lumina that may be prominent or inconspicuous. Further, the tumor cells of clear cell hidradenoma show positive immunostaining for epithelial markers (eg, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2).

Cutaneous metastasis of ccRCC is rare and usually presents clinically as a larger lesion than a clear cell fibrous papule. The cells of ccRCC have moderate to abundant clear cytoplasm and nuclei with varying degrees of pleomorphism (Figure 6). Periodic acid–Schiff staining demonstrates intracytoplasmic glycogen. The stroma is abundantly vascular and extravasated blood cells are frequently observed. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells of ccRCC stain positively for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, CD10, and vimentin.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Chiang YY, Tsai HH, Lee WR, et al. Clear cell fibrous papule: report of a case mimicking a balloon cell nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:381-384.

- Lee AN, Stein SL, Cohen LM. Clear cell fibrous papule with NKI/C3 expression: clinical and histologic features in six cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:296-300.

A fibrous papule is a common benign lesion that usually presents in adults on the face, especially on the lower portion of the nose. It typically presents as a small (2–5 mm), asymptomatic, flesh-colored, dome-shaped lesion that is firm and nontender. Several histopathologic variants of fibrous papules have been described, including clear cell, granular, epithelioid, hypercellular, pleomorphic, pigmented, and inflammatory.1 Clear cell fibrous papules are exceedingly rare. On microscopic examination the epidermis may be normal or show some degree of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, erosion, ulceration, or crust. The basal layer may show an increase of melanin. The dermis is expanded by a proliferation of clear cells arranged in sheets, clusters, or as single cells (Figure 1). The clear cells show variation in size and shape. The nuclei are small and round without pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, or mitoses. The nuclei may be centrally located or eccentrically displaced by a large intracytoplasmic vacuole (Figure 2). Some clear cells may exhibit finely vacuolated cytoplasm with nuclear scalloping. The surrounding stroma usually consists of sclerotic collagen and dilated blood vessels (Figure 3). Extravasated red blood cells may be present focally. Patchy lymphocytic infiltrates may be found in the stroma at the periphery of the lesion. Periodic acid–Schiff and mucicarmine staining of the clear cells is negative. On immunohistochemistry, the clear cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and HMB-45 (human melanoma black 45).2,3 The clear cells often are positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, and NKI/C3 (anti-CD63) but also may be negative. The S-100 protein often is negative but may be focally positive.

The differential diagnosis for clear cell fibrous papules is broad but reasonably includes balloon cell nevus, clear cell hidradenoma, and cutaneous metastasis of clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Balloon cell malignant melanoma is not considered strongly in the differential diagnosis because it usually exhibits invasive growth, cytologic atypia, and mitoses, all of which are not characteristic morphologic features of clear cell fibrous papules.

A balloon cell nevus may be difficult to distinguish from a clear cell fibrous papule on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4); however, the nuclei of a balloon cell nevus tend to be more rounded and centrally located. Any junctional nesting or nests of conventional nevus cells in the dermis also help differentiate a balloon cell nevus from a clear cell fibrous papule. Diffusely positive immunostaining for S-100 protein also is indicative of a balloon cell nevus.

Clear cell hidradenoma consists predominantly of cells with clear cytoplasm and small dark nuclei that may closely mimic a clear cell fibrous papule (Figure 5) but often shows a second population of cells with more vesicular nuclei and dark eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cystic spaces containing hyaline material and foci of squamoid change are common, along with occasional tubular lumina that may be prominent or inconspicuous. Further, the tumor cells of clear cell hidradenoma show positive immunostaining for epithelial markers (eg, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2).

Cutaneous metastasis of ccRCC is rare and usually presents clinically as a larger lesion than a clear cell fibrous papule. The cells of ccRCC have moderate to abundant clear cytoplasm and nuclei with varying degrees of pleomorphism (Figure 6). Periodic acid–Schiff staining demonstrates intracytoplasmic glycogen. The stroma is abundantly vascular and extravasated blood cells are frequently observed. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells of ccRCC stain positively for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, CD10, and vimentin.

A fibrous papule is a common benign lesion that usually presents in adults on the face, especially on the lower portion of the nose. It typically presents as a small (2–5 mm), asymptomatic, flesh-colored, dome-shaped lesion that is firm and nontender. Several histopathologic variants of fibrous papules have been described, including clear cell, granular, epithelioid, hypercellular, pleomorphic, pigmented, and inflammatory.1 Clear cell fibrous papules are exceedingly rare. On microscopic examination the epidermis may be normal or show some degree of hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis, erosion, ulceration, or crust. The basal layer may show an increase of melanin. The dermis is expanded by a proliferation of clear cells arranged in sheets, clusters, or as single cells (Figure 1). The clear cells show variation in size and shape. The nuclei are small and round without pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, or mitoses. The nuclei may be centrally located or eccentrically displaced by a large intracytoplasmic vacuole (Figure 2). Some clear cells may exhibit finely vacuolated cytoplasm with nuclear scalloping. The surrounding stroma usually consists of sclerotic collagen and dilated blood vessels (Figure 3). Extravasated red blood cells may be present focally. Patchy lymphocytic infiltrates may be found in the stroma at the periphery of the lesion. Periodic acid–Schiff and mucicarmine staining of the clear cells is negative. On immunohistochemistry, the clear cells are diffusely positive for vimentin and negative for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, epithelial membrane antigen, carcinoembryonic antigen, and HMB-45 (human melanoma black 45).2,3 The clear cells often are positive for CD68, factor XIIIa, and NKI/C3 (anti-CD63) but also may be negative. The S-100 protein often is negative but may be focally positive.

The differential diagnosis for clear cell fibrous papules is broad but reasonably includes balloon cell nevus, clear cell hidradenoma, and cutaneous metastasis of clear cell (conventional) renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC). Balloon cell malignant melanoma is not considered strongly in the differential diagnosis because it usually exhibits invasive growth, cytologic atypia, and mitoses, all of which are not characteristic morphologic features of clear cell fibrous papules.

A balloon cell nevus may be difficult to distinguish from a clear cell fibrous papule on routine hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 4); however, the nuclei of a balloon cell nevus tend to be more rounded and centrally located. Any junctional nesting or nests of conventional nevus cells in the dermis also help differentiate a balloon cell nevus from a clear cell fibrous papule. Diffusely positive immunostaining for S-100 protein also is indicative of a balloon cell nevus.

Clear cell hidradenoma consists predominantly of cells with clear cytoplasm and small dark nuclei that may closely mimic a clear cell fibrous papule (Figure 5) but often shows a second population of cells with more vesicular nuclei and dark eosinophilic cytoplasm. Cystic spaces containing hyaline material and foci of squamoid change are common, along with occasional tubular lumina that may be prominent or inconspicuous. Further, the tumor cells of clear cell hidradenoma show positive immunostaining for epithelial markers (eg, cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2).

Cutaneous metastasis of ccRCC is rare and usually presents clinically as a larger lesion than a clear cell fibrous papule. The cells of ccRCC have moderate to abundant clear cytoplasm and nuclei with varying degrees of pleomorphism (Figure 6). Periodic acid–Schiff staining demonstrates intracytoplasmic glycogen. The stroma is abundantly vascular and extravasated blood cells are frequently observed. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells of ccRCC stain positively for cytokeratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, epithelial membrane antigen, CD10, and vimentin.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Chiang YY, Tsai HH, Lee WR, et al. Clear cell fibrous papule: report of a case mimicking a balloon cell nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:381-384.

- Lee AN, Stein SL, Cohen LM. Clear cell fibrous papule with NKI/C3 expression: clinical and histologic features in six cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:296-300.

- Bansal C, Stewart D, Li A, et al. Histologic variants of fibrous papule. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:424-428.

- Chiang YY, Tsai HH, Lee WR, et al. Clear cell fibrous papule: report of a case mimicking a balloon cell nevus. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:381-384.

- Lee AN, Stein SL, Cohen LM. Clear cell fibrous papule with NKI/C3 expression: clinical and histologic features in six cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:296-300.