User login

Treat depressed teens with medication and psychotherapy

Refer adolescents with moderate to severe depression for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to improve their outcomes.1-3

Strength of recommendation

B: Two well-done randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Schoeman Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression. The TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:901-913.

March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132-1143.

March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression. Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807-820.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Jason, a depressed 17-year-old, is brought in by his mother, who’s worried about his mood and lack of motivation. He reports that his mood has “sunk” over the last 2 months. His mother interjects that she suffers from depression herself and that she’s divorced and unable to compensate for the absence of Jason’s father. She also says that her 2 older sons, both of whom Jason is close to, recently moved out of state. Further questioning reveals that Jason has lost interest in school, sports, friends, and his part-time job; he’s pessimistic about the future and feels helpless and stuck. Jason avoids going out and spends hours on the Internet.

You consider prescribing a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), but you’re concerned about the potential suicide risk—a risk that’s already elevated for teens with major depressive disorder (MDD). Would a referral to a therapist be a safer choice? Is psychotherapy alone sufficient? What type of therapy is best?

Depressive disorders are common among adolescents and young adults, affecting nearly 1 in 4 by age 24.4 Most seek help from primary care physicians, who typically prescribe SSRIs.5 Yet only about one third of depressed teens achieve complete remission with medication alone.1 For the two thirds who continue to have depressive symptoms, the consequences can be severe. Depressive illness is associated with family conflict, smoking and substance abuse, impaired functioning in school and in relationships, and increased risk of suicide—the third leading cause of death in adolescents.6

Drugs, psychotherapy, or both?

The Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC), published in November 2007, encourage primary care physicians to take a more active role in detecting and managing adolescent depression.7 GLAD-PC and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommend that teens with depressive illness receive psychotherapy, either as primary treatment or in conjunction with antidepressants.7,8 Until recently, however, that recommendation lacked definitive evidence to support it.

STUDY SUMMARIES

2 studies explore combination approach

TADS (Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study)2,3 and TORDIA (Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents)1 are the only 2 randomized trials to address the role of CBT in combination with antidepressants in treating this patient population. Both show a significant benefit when CBT is added to drug therapy.

TADS: Highest improvement rates with fluoxetine and CBT

The TADS team studied 439 adolescents (ages 12 to 17 years) diagnosed with MDD. Patients were evaluated at consent, baseline, and weeks 6, 12, 18, 30, and 36. Those who were already taking antidepressants were excluded, but concurrent therapy for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder was permitted.

Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of the following 12-week treatment options:

•Fluoxetine (10-40 mg/d)

•CBT

•Fluoxetine (10-40 mg/d) + CBT

•Placebo

CBT consisted of 15 sessions over 12 weeks, each lasting 50 to 60 minutes. In addition to individual sessions, 2 parental sessions and 1 to 3 family sessions were included. Primary outcome measures were the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale (CGI-I), which is based on a clinician’s overall assessment of the patient’s improvement; and the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R), which is derived from parent and adolescent interviews.

At 12 weeks, patients receiving fluoxetine and CBT demonstrated the highest rates of improvement: Seventy-one percent (95% confidence interval [CI], 62%-80%) were “much” or “very much” improved, vs 60.6% (95% CI, 51%-70%) of those on fluoxetine alone. In comparison, 43.2% (95% CI, 34%-52%) of patients receiving CBT alone were much or very much improved at the 12-week mark, and only 34.8% (95% CI, 26%-44%) of those on placebo.

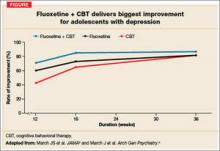

At 18 weeks, the medication/CBT combination remained superior to either psychotherapy or fluoxetine alone. By week 30, all 3 intervention groups converged, and at 36 weeks there was virtually no difference in outcomes (FIGURE).

CBT alone has protective effect. While CBT alone was not significantly better than placebo overall, it demonstrated a protective effect with regard to suicidal events (thoughts, threats, or attempts) compared to fluoxetine. Conversely, fluoxetine accelerated the rate of improvement in mood during the first 30 weeks of treatment.

TORDIA: How to help patients after failed treatment

Brent and colleagues studied 334 patients between the ages of 12 and 18 years who were diagnosed with MDD but did not respond to initial SSRI therapy. After a 4-week trial, they were reevaluated and tapered off the medication, then randomly assigned to 1 of the following treatment groups for 12 weeks:

•Switched to a new SSRI

•Switched to venlafaxine (a selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor)

•Switched to a new SSRI + CBT

•Switched to venlafaxine + CBT

All patients were reevaluated at week 12. Here, too, the CGI-I and CDRS-R were used for key outcome measures.

Adding CBT to a medication regimen was associated with an increased response rate; choice of antidepressant was not. The groups receiving CBT were significantly more likely to show improvement compared to those who were not undergoing CBT (54.8% [95% CI, 47%-62%] vs 40.5% [95% CI, 33%-48%], number needed to treat [NNT]=7).

WHAT'S NEW?

An alternative that speeds recovery

These 2 studies confirm the value of CBT in treating moderate to severe major depression in combination with antidepressant therapy. TADS provides evidence of both a faster recovery trajectory and lower likelihood of suicidal events with combined treatment. While TORDIA does not demonstrate a quicker recovery in terms of depressed mood or a lower rate of suicidal events, it suggests that for adolescents who do not respond to antidepressants, a referral to CBT will be more effective than a switch to a different drug.

CAVEATS

Approach was not tested with mild depression

Most adolescents who report depressive symptoms to primary care physicians either do not meet the full criteria for major depression or fall into the mild major depression range.9-11 Both of these studies enrolled only those with moderate to severe MDD.

There is evidence, however, that such an approach may not be necessary for teens with milder depression. Many earlier studies of psychotherapy alone vs control (wait list or observation) for patients with sub-threshold depressive disorders or mild major depression demonstrated that psychotherapy is effective in treating these less severe depressive states.7,12 GLAD-PC recommends a 4- to 8-week trial of active monitoring for patients with mild MDD before initiating psychotherapy or medication.2

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Patient perceptions, stigma

There are 3 major barriers to implementation: patient/parent resistance to psychotherapy, limited access to mental health specialists (lack of supply and insurance coverage limitations), and few quality standards for evidence-based psychotherapeutic approaches in community practice settings.13-15 Many adolescents have a negative view of therapy and feel stigmatized by a referral to a psychotherapist. They may also have a well-developed rationale as to why such treatment would not work for them.16

Physicians can help teens overcome these negative perceptions by giving them an opportunity to discuss their concerns—and by clarifying any misconceptions.17 The idea that “brain changes” cause depression has become popular in recent years,18 and may provide some relief to those who are troubled by the notion that they are somehow to blame for their depression.19 Presenting both antidepressant medication and psychotherapy as interventions that “change the way the brain manages mood” may be helpful in alleviating self-blame.

Consider nontraditional approaches

In areas with limited access to mental health specialists, nontraditional approaches may be needed. One such approach is to help patients arrange an initial interview with a psychotherapist, followed by telephone counseling sessions. For patients 18 years or older, MoodGym (http://moodgym.anu.edu.au/welcome) is also an option. This free Internet site incorporates features of standardized CBT and interpersonal therapy, and has demonstrated efficacy in RCTs of adults.20 For those between the ages of 14 and 21, CATCH-IT (http://catchit-public.bsd.uchicago.edu)21 is another Internet option. The site, which can be accessed by physicians and the general public, focuses on building competencies to reduce current and future depressive symptoms.

In addition, recommend self-help books. While there have been no studies of their value to adolescents, the book with the greatest evidence of efficacy in adults is “Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy,” by David D. Burns.22

For your part... Before making referrals to mental health specialists, ask therapists whether they incorporate, and have been trained in, cognitive behavioral therapy. In addition, you can remain involved by asking the psychotherapist for a written treatment plan and by encouraging adolescents (and their families) to fully adhere to it.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Purls Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number ul1rr024999 from the National Center For research resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For research resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Benjamin Van Voorhees is supported by a career development award from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NImHK-08mH072918-01A2).

1. Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:901-913.

2. March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132-1143.

3. March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807-820.

4. Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-IIIR major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7:3-14.

5. Rushton JL, Clark SJ, Freed GL. Pediatrician and family physician prescription of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E82.

6. Hankin BL. Adolescent depression: description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8:102-114.

7. Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Ghalib K, Laraque D, Stein RE . Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1313-e1326.

8. Birmaher B , Brent DA, Benson RS. Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1234-1238.

9. Yates P, Kramer T, Garralda E . Depressive symptoms amongst adolescent primary care attenders. Levels and associations. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:588-594.

10. Rushton JL, Forcier M , Schectman RM . Epidemiology of depressive symptoms in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:199-205.

11. Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL , Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:196-204.

12. Compton SN, March JS, Brent D, Albano AM, Weersing R , Curry J. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:930-959.

13. Asarnow JR, Jaycox L H, Anderson M . Depression among youth in primary care models for delivering mental health services. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;11:477-497, viii.

14. Wisdom JP, Clarke GN, Green CA. What teens want: barriers to seeking care for depression. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33:133-145.

15. Zuckerbrot R A, Cheung AH, Jensen PS, Stein RE , Laraque D. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): I. Identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1299-e1312.

16. Van Voorhees B W, Fogel J, Houston TK, Cooper LA, Wang NY, Ford DE. Beliefs and attitudes associated with the intention to not accept the diagnosis of depression among young adults. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:38-46.

17. Clever SL, Ford DE, Rubenstein LV , et al. Primary care patients’ involvement in decision-making is associated with improvement in depression. Med Care. 2006;44:398-405.

18. Lacasse JR. Consumer advertising of psychiatric medications biases the public against nonpharmacological treatment. Ethical Hum Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;7:175-179.

19. Van Voorhees B W, Cooper L A, Rost KM, et al. Primary care patients with depression are less accepting of treatment than those seen by mental health specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:991-1000.

20. Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF. Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;328:265.

21. Anderson L , Lewis G, Araya R, et al. Self-help books for depression: how can practitioners and patients make the right choice? Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:387-392.

22. Van Voorhees B W, Vanderploegbooth K, Fogel J, et al. Integrative Internet-based depression prevention for adolescents: a randomized clinical trial in primary care for vulnerability and protective factors. J Can Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry. In press.

Refer adolescents with moderate to severe depression for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to improve their outcomes.1-3

Strength of recommendation

B: Two well-done randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Schoeman Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression. The TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:901-913.

March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132-1143.

March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression. Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807-820.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Jason, a depressed 17-year-old, is brought in by his mother, who’s worried about his mood and lack of motivation. He reports that his mood has “sunk” over the last 2 months. His mother interjects that she suffers from depression herself and that she’s divorced and unable to compensate for the absence of Jason’s father. She also says that her 2 older sons, both of whom Jason is close to, recently moved out of state. Further questioning reveals that Jason has lost interest in school, sports, friends, and his part-time job; he’s pessimistic about the future and feels helpless and stuck. Jason avoids going out and spends hours on the Internet.

You consider prescribing a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), but you’re concerned about the potential suicide risk—a risk that’s already elevated for teens with major depressive disorder (MDD). Would a referral to a therapist be a safer choice? Is psychotherapy alone sufficient? What type of therapy is best?

Depressive disorders are common among adolescents and young adults, affecting nearly 1 in 4 by age 24.4 Most seek help from primary care physicians, who typically prescribe SSRIs.5 Yet only about one third of depressed teens achieve complete remission with medication alone.1 For the two thirds who continue to have depressive symptoms, the consequences can be severe. Depressive illness is associated with family conflict, smoking and substance abuse, impaired functioning in school and in relationships, and increased risk of suicide—the third leading cause of death in adolescents.6

Drugs, psychotherapy, or both?

The Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC), published in November 2007, encourage primary care physicians to take a more active role in detecting and managing adolescent depression.7 GLAD-PC and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommend that teens with depressive illness receive psychotherapy, either as primary treatment or in conjunction with antidepressants.7,8 Until recently, however, that recommendation lacked definitive evidence to support it.

STUDY SUMMARIES

2 studies explore combination approach

TADS (Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study)2,3 and TORDIA (Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents)1 are the only 2 randomized trials to address the role of CBT in combination with antidepressants in treating this patient population. Both show a significant benefit when CBT is added to drug therapy.

TADS: Highest improvement rates with fluoxetine and CBT

The TADS team studied 439 adolescents (ages 12 to 17 years) diagnosed with MDD. Patients were evaluated at consent, baseline, and weeks 6, 12, 18, 30, and 36. Those who were already taking antidepressants were excluded, but concurrent therapy for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder was permitted.

Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of the following 12-week treatment options:

•Fluoxetine (10-40 mg/d)

•CBT

•Fluoxetine (10-40 mg/d) + CBT

•Placebo

CBT consisted of 15 sessions over 12 weeks, each lasting 50 to 60 minutes. In addition to individual sessions, 2 parental sessions and 1 to 3 family sessions were included. Primary outcome measures were the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale (CGI-I), which is based on a clinician’s overall assessment of the patient’s improvement; and the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R), which is derived from parent and adolescent interviews.

At 12 weeks, patients receiving fluoxetine and CBT demonstrated the highest rates of improvement: Seventy-one percent (95% confidence interval [CI], 62%-80%) were “much” or “very much” improved, vs 60.6% (95% CI, 51%-70%) of those on fluoxetine alone. In comparison, 43.2% (95% CI, 34%-52%) of patients receiving CBT alone were much or very much improved at the 12-week mark, and only 34.8% (95% CI, 26%-44%) of those on placebo.

At 18 weeks, the medication/CBT combination remained superior to either psychotherapy or fluoxetine alone. By week 30, all 3 intervention groups converged, and at 36 weeks there was virtually no difference in outcomes (FIGURE).

CBT alone has protective effect. While CBT alone was not significantly better than placebo overall, it demonstrated a protective effect with regard to suicidal events (thoughts, threats, or attempts) compared to fluoxetine. Conversely, fluoxetine accelerated the rate of improvement in mood during the first 30 weeks of treatment.

TORDIA: How to help patients after failed treatment

Brent and colleagues studied 334 patients between the ages of 12 and 18 years who were diagnosed with MDD but did not respond to initial SSRI therapy. After a 4-week trial, they were reevaluated and tapered off the medication, then randomly assigned to 1 of the following treatment groups for 12 weeks:

•Switched to a new SSRI

•Switched to venlafaxine (a selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor)

•Switched to a new SSRI + CBT

•Switched to venlafaxine + CBT

All patients were reevaluated at week 12. Here, too, the CGI-I and CDRS-R were used for key outcome measures.

Adding CBT to a medication regimen was associated with an increased response rate; choice of antidepressant was not. The groups receiving CBT were significantly more likely to show improvement compared to those who were not undergoing CBT (54.8% [95% CI, 47%-62%] vs 40.5% [95% CI, 33%-48%], number needed to treat [NNT]=7).

WHAT'S NEW?

An alternative that speeds recovery

These 2 studies confirm the value of CBT in treating moderate to severe major depression in combination with antidepressant therapy. TADS provides evidence of both a faster recovery trajectory and lower likelihood of suicidal events with combined treatment. While TORDIA does not demonstrate a quicker recovery in terms of depressed mood or a lower rate of suicidal events, it suggests that for adolescents who do not respond to antidepressants, a referral to CBT will be more effective than a switch to a different drug.

CAVEATS

Approach was not tested with mild depression

Most adolescents who report depressive symptoms to primary care physicians either do not meet the full criteria for major depression or fall into the mild major depression range.9-11 Both of these studies enrolled only those with moderate to severe MDD.

There is evidence, however, that such an approach may not be necessary for teens with milder depression. Many earlier studies of psychotherapy alone vs control (wait list or observation) for patients with sub-threshold depressive disorders or mild major depression demonstrated that psychotherapy is effective in treating these less severe depressive states.7,12 GLAD-PC recommends a 4- to 8-week trial of active monitoring for patients with mild MDD before initiating psychotherapy or medication.2

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Patient perceptions, stigma

There are 3 major barriers to implementation: patient/parent resistance to psychotherapy, limited access to mental health specialists (lack of supply and insurance coverage limitations), and few quality standards for evidence-based psychotherapeutic approaches in community practice settings.13-15 Many adolescents have a negative view of therapy and feel stigmatized by a referral to a psychotherapist. They may also have a well-developed rationale as to why such treatment would not work for them.16

Physicians can help teens overcome these negative perceptions by giving them an opportunity to discuss their concerns—and by clarifying any misconceptions.17 The idea that “brain changes” cause depression has become popular in recent years,18 and may provide some relief to those who are troubled by the notion that they are somehow to blame for their depression.19 Presenting both antidepressant medication and psychotherapy as interventions that “change the way the brain manages mood” may be helpful in alleviating self-blame.

Consider nontraditional approaches

In areas with limited access to mental health specialists, nontraditional approaches may be needed. One such approach is to help patients arrange an initial interview with a psychotherapist, followed by telephone counseling sessions. For patients 18 years or older, MoodGym (http://moodgym.anu.edu.au/welcome) is also an option. This free Internet site incorporates features of standardized CBT and interpersonal therapy, and has demonstrated efficacy in RCTs of adults.20 For those between the ages of 14 and 21, CATCH-IT (http://catchit-public.bsd.uchicago.edu)21 is another Internet option. The site, which can be accessed by physicians and the general public, focuses on building competencies to reduce current and future depressive symptoms.

In addition, recommend self-help books. While there have been no studies of their value to adolescents, the book with the greatest evidence of efficacy in adults is “Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy,” by David D. Burns.22

For your part... Before making referrals to mental health specialists, ask therapists whether they incorporate, and have been trained in, cognitive behavioral therapy. In addition, you can remain involved by asking the psychotherapist for a written treatment plan and by encouraging adolescents (and their families) to fully adhere to it.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Purls Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number ul1rr024999 from the National Center For research resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For research resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Benjamin Van Voorhees is supported by a career development award from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NImHK-08mH072918-01A2).

Refer adolescents with moderate to severe depression for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to improve their outcomes.1-3

Strength of recommendation

B: Two well-done randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Schoeman Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression. The TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:901-913.

March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132-1143.

March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression. Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807-820.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

Jason, a depressed 17-year-old, is brought in by his mother, who’s worried about his mood and lack of motivation. He reports that his mood has “sunk” over the last 2 months. His mother interjects that she suffers from depression herself and that she’s divorced and unable to compensate for the absence of Jason’s father. She also says that her 2 older sons, both of whom Jason is close to, recently moved out of state. Further questioning reveals that Jason has lost interest in school, sports, friends, and his part-time job; he’s pessimistic about the future and feels helpless and stuck. Jason avoids going out and spends hours on the Internet.

You consider prescribing a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), but you’re concerned about the potential suicide risk—a risk that’s already elevated for teens with major depressive disorder (MDD). Would a referral to a therapist be a safer choice? Is psychotherapy alone sufficient? What type of therapy is best?

Depressive disorders are common among adolescents and young adults, affecting nearly 1 in 4 by age 24.4 Most seek help from primary care physicians, who typically prescribe SSRIs.5 Yet only about one third of depressed teens achieve complete remission with medication alone.1 For the two thirds who continue to have depressive symptoms, the consequences can be severe. Depressive illness is associated with family conflict, smoking and substance abuse, impaired functioning in school and in relationships, and increased risk of suicide—the third leading cause of death in adolescents.6

Drugs, psychotherapy, or both?

The Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC), published in November 2007, encourage primary care physicians to take a more active role in detecting and managing adolescent depression.7 GLAD-PC and the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry recommend that teens with depressive illness receive psychotherapy, either as primary treatment or in conjunction with antidepressants.7,8 Until recently, however, that recommendation lacked definitive evidence to support it.

STUDY SUMMARIES

2 studies explore combination approach

TADS (Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study)2,3 and TORDIA (Treatment of Resistant Depression in Adolescents)1 are the only 2 randomized trials to address the role of CBT in combination with antidepressants in treating this patient population. Both show a significant benefit when CBT is added to drug therapy.

TADS: Highest improvement rates with fluoxetine and CBT

The TADS team studied 439 adolescents (ages 12 to 17 years) diagnosed with MDD. Patients were evaluated at consent, baseline, and weeks 6, 12, 18, 30, and 36. Those who were already taking antidepressants were excluded, but concurrent therapy for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder was permitted.

Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of the following 12-week treatment options:

•Fluoxetine (10-40 mg/d)

•CBT

•Fluoxetine (10-40 mg/d) + CBT

•Placebo

CBT consisted of 15 sessions over 12 weeks, each lasting 50 to 60 minutes. In addition to individual sessions, 2 parental sessions and 1 to 3 family sessions were included. Primary outcome measures were the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement Scale (CGI-I), which is based on a clinician’s overall assessment of the patient’s improvement; and the Children’s Depression Rating Scale-Revised (CDRS-R), which is derived from parent and adolescent interviews.

At 12 weeks, patients receiving fluoxetine and CBT demonstrated the highest rates of improvement: Seventy-one percent (95% confidence interval [CI], 62%-80%) were “much” or “very much” improved, vs 60.6% (95% CI, 51%-70%) of those on fluoxetine alone. In comparison, 43.2% (95% CI, 34%-52%) of patients receiving CBT alone were much or very much improved at the 12-week mark, and only 34.8% (95% CI, 26%-44%) of those on placebo.

At 18 weeks, the medication/CBT combination remained superior to either psychotherapy or fluoxetine alone. By week 30, all 3 intervention groups converged, and at 36 weeks there was virtually no difference in outcomes (FIGURE).

CBT alone has protective effect. While CBT alone was not significantly better than placebo overall, it demonstrated a protective effect with regard to suicidal events (thoughts, threats, or attempts) compared to fluoxetine. Conversely, fluoxetine accelerated the rate of improvement in mood during the first 30 weeks of treatment.

TORDIA: How to help patients after failed treatment

Brent and colleagues studied 334 patients between the ages of 12 and 18 years who were diagnosed with MDD but did not respond to initial SSRI therapy. After a 4-week trial, they were reevaluated and tapered off the medication, then randomly assigned to 1 of the following treatment groups for 12 weeks:

•Switched to a new SSRI

•Switched to venlafaxine (a selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor)

•Switched to a new SSRI + CBT

•Switched to venlafaxine + CBT

All patients were reevaluated at week 12. Here, too, the CGI-I and CDRS-R were used for key outcome measures.

Adding CBT to a medication regimen was associated with an increased response rate; choice of antidepressant was not. The groups receiving CBT were significantly more likely to show improvement compared to those who were not undergoing CBT (54.8% [95% CI, 47%-62%] vs 40.5% [95% CI, 33%-48%], number needed to treat [NNT]=7).

WHAT'S NEW?

An alternative that speeds recovery

These 2 studies confirm the value of CBT in treating moderate to severe major depression in combination with antidepressant therapy. TADS provides evidence of both a faster recovery trajectory and lower likelihood of suicidal events with combined treatment. While TORDIA does not demonstrate a quicker recovery in terms of depressed mood or a lower rate of suicidal events, it suggests that for adolescents who do not respond to antidepressants, a referral to CBT will be more effective than a switch to a different drug.

CAVEATS

Approach was not tested with mild depression

Most adolescents who report depressive symptoms to primary care physicians either do not meet the full criteria for major depression or fall into the mild major depression range.9-11 Both of these studies enrolled only those with moderate to severe MDD.

There is evidence, however, that such an approach may not be necessary for teens with milder depression. Many earlier studies of psychotherapy alone vs control (wait list or observation) for patients with sub-threshold depressive disorders or mild major depression demonstrated that psychotherapy is effective in treating these less severe depressive states.7,12 GLAD-PC recommends a 4- to 8-week trial of active monitoring for patients with mild MDD before initiating psychotherapy or medication.2

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Patient perceptions, stigma

There are 3 major barriers to implementation: patient/parent resistance to psychotherapy, limited access to mental health specialists (lack of supply and insurance coverage limitations), and few quality standards for evidence-based psychotherapeutic approaches in community practice settings.13-15 Many adolescents have a negative view of therapy and feel stigmatized by a referral to a psychotherapist. They may also have a well-developed rationale as to why such treatment would not work for them.16

Physicians can help teens overcome these negative perceptions by giving them an opportunity to discuss their concerns—and by clarifying any misconceptions.17 The idea that “brain changes” cause depression has become popular in recent years,18 and may provide some relief to those who are troubled by the notion that they are somehow to blame for their depression.19 Presenting both antidepressant medication and psychotherapy as interventions that “change the way the brain manages mood” may be helpful in alleviating self-blame.

Consider nontraditional approaches

In areas with limited access to mental health specialists, nontraditional approaches may be needed. One such approach is to help patients arrange an initial interview with a psychotherapist, followed by telephone counseling sessions. For patients 18 years or older, MoodGym (http://moodgym.anu.edu.au/welcome) is also an option. This free Internet site incorporates features of standardized CBT and interpersonal therapy, and has demonstrated efficacy in RCTs of adults.20 For those between the ages of 14 and 21, CATCH-IT (http://catchit-public.bsd.uchicago.edu)21 is another Internet option. The site, which can be accessed by physicians and the general public, focuses on building competencies to reduce current and future depressive symptoms.

In addition, recommend self-help books. While there have been no studies of their value to adolescents, the book with the greatest evidence of efficacy in adults is “Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy,” by David D. Burns.22

For your part... Before making referrals to mental health specialists, ask therapists whether they incorporate, and have been trained in, cognitive behavioral therapy. In addition, you can remain involved by asking the psychotherapist for a written treatment plan and by encouraging adolescents (and their families) to fully adhere to it.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Purls Surveillance System is supported in part by Grant Number ul1rr024999 from the National Center For research resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For research resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Benjamin Van Voorhees is supported by a career development award from the National Institutes of Mental Health (NImHK-08mH072918-01A2).

1. Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:901-913.

2. March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132-1143.

3. March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807-820.

4. Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-IIIR major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7:3-14.

5. Rushton JL, Clark SJ, Freed GL. Pediatrician and family physician prescription of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E82.

6. Hankin BL. Adolescent depression: description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8:102-114.

7. Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Ghalib K, Laraque D, Stein RE . Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1313-e1326.

8. Birmaher B , Brent DA, Benson RS. Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1234-1238.

9. Yates P, Kramer T, Garralda E . Depressive symptoms amongst adolescent primary care attenders. Levels and associations. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:588-594.

10. Rushton JL, Forcier M , Schectman RM . Epidemiology of depressive symptoms in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:199-205.

11. Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL , Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:196-204.

12. Compton SN, March JS, Brent D, Albano AM, Weersing R , Curry J. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:930-959.

13. Asarnow JR, Jaycox L H, Anderson M . Depression among youth in primary care models for delivering mental health services. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;11:477-497, viii.

14. Wisdom JP, Clarke GN, Green CA. What teens want: barriers to seeking care for depression. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33:133-145.

15. Zuckerbrot R A, Cheung AH, Jensen PS, Stein RE , Laraque D. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): I. Identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1299-e1312.

16. Van Voorhees B W, Fogel J, Houston TK, Cooper LA, Wang NY, Ford DE. Beliefs and attitudes associated with the intention to not accept the diagnosis of depression among young adults. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:38-46.

17. Clever SL, Ford DE, Rubenstein LV , et al. Primary care patients’ involvement in decision-making is associated with improvement in depression. Med Care. 2006;44:398-405.

18. Lacasse JR. Consumer advertising of psychiatric medications biases the public against nonpharmacological treatment. Ethical Hum Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;7:175-179.

19. Van Voorhees B W, Cooper L A, Rost KM, et al. Primary care patients with depression are less accepting of treatment than those seen by mental health specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:991-1000.

20. Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF. Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;328:265.

21. Anderson L , Lewis G, Araya R, et al. Self-help books for depression: how can practitioners and patients make the right choice? Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:387-392.

22. Van Voorhees B W, Vanderploegbooth K, Fogel J, et al. Integrative Internet-based depression prevention for adolescents: a randomized clinical trial in primary care for vulnerability and protective factors. J Can Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry. In press.

1. Brent D, Emslie G, Clarke G, et al. Switching to another SSRI or to venlafaxine with or without cognitive behavioral therapy for adolescents with SSRI-resistant depression: the TORDIA randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:901-913.

2. March JS, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. The Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS): long-term effectiveness and safety outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1132-1143.

3. March J, Silva S, Petrycki S, et al. Fluoxetine, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and their combination for adolescents with depression: Treatment for Adolescents With Depression Study (TADS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:807-820.

4. Kessler RC, Walters EE. Epidemiology of DSM-IIIR major depression and minor depression among adolescents and young adults in the National Comorbidity Survey. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7:3-14.

5. Rushton JL, Clark SJ, Freed GL. Pediatrician and family physician prescription of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Pediatrics. 2000;105:E82.

6. Hankin BL. Adolescent depression: description, causes, and interventions. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8:102-114.

7. Cheung AH, Zuckerbrot RA, Jensen PS, Ghalib K, Laraque D, Stein RE . Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): II. Treatment and ongoing management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1313-e1326.

8. Birmaher B , Brent DA, Benson RS. Summary of the practice parameters for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorders. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:1234-1238.

9. Yates P, Kramer T, Garralda E . Depressive symptoms amongst adolescent primary care attenders. Levels and associations. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2004;39:588-594.

10. Rushton JL, Forcier M , Schectman RM . Epidemiology of depressive symptoms in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:199-205.

11. Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL , Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30:196-204.

12. Compton SN, March JS, Brent D, Albano AM, Weersing R , Curry J. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for anxiety and depressive disorders in children and adolescents: an evidence-based medicine review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:930-959.

13. Asarnow JR, Jaycox L H, Anderson M . Depression among youth in primary care models for delivering mental health services. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2002;11:477-497, viii.

14. Wisdom JP, Clarke GN, Green CA. What teens want: barriers to seeking care for depression. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2006;33:133-145.

15. Zuckerbrot R A, Cheung AH, Jensen PS, Stein RE , Laraque D. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): I. Identification, assessment, and initial management. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e1299-e1312.

16. Van Voorhees B W, Fogel J, Houston TK, Cooper LA, Wang NY, Ford DE. Beliefs and attitudes associated with the intention to not accept the diagnosis of depression among young adults. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:38-46.

17. Clever SL, Ford DE, Rubenstein LV , et al. Primary care patients’ involvement in decision-making is associated with improvement in depression. Med Care. 2006;44:398-405.

18. Lacasse JR. Consumer advertising of psychiatric medications biases the public against nonpharmacological treatment. Ethical Hum Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;7:175-179.

19. Van Voorhees B W, Cooper L A, Rost KM, et al. Primary care patients with depression are less accepting of treatment than those seen by mental health specialists. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:991-1000.

20. Christensen H, Griffiths KM, Jorm AF. Delivering interventions for depression by using the internet: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;328:265.

21. Anderson L , Lewis G, Araya R, et al. Self-help books for depression: how can practitioners and patients make the right choice? Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55:387-392.

22. Van Voorhees B W, Vanderploegbooth K, Fogel J, et al. Integrative Internet-based depression prevention for adolescents: a randomized clinical trial in primary care for vulnerability and protective factors. J Can Acad Child Adoles Psychiatry. In press.

Copyright © 2008 Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient

A crucial arena of innovative educational programs for the care of the elderly must include the hospital setting, a place of great cost, morbidity, and mortality for a population currently occupying approximately half of US hospital beds.1 With a marked acceleration in the number of persons living to an advanced age, there is a clear imperative to address the health‐care needs of the elderly, particularly the complex and frail.24 An educational grounding that steps beyond the traditional organ‐based models of disease to a much broader patient‐centered framework of care is necessary to aid physicians in advanced clinical decision‐making in the care of older patients. Organizing the medical care of the older patient within existing systems of care and a team care management network must also be improved.

Curricular materials and methods are widely available for teaching geriatric medicine,57 but most are geared toward outpatient care and management, with few addressing the care of the hospitalized, older medical patient.810 There is even less published on curricular materials, methods, and tools for such teaching outside of specialized hospital‐based geriatric units by nongeriatrics‐trained faculty.1113 Furthermore, the evaluation of geriatrics educational programs in the hospital setting has not been done with the ultimate assessment, the linking of educational programs to demonstrated changes in clinical practice and patient care outcomes.

To address these needs, we designed and implemented the Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient (CHAMP) Faculty Development Program (FDP). CHAMP was funded by a grant from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation Aging and Quality of Life Program with a matching commitment from the University of Chicago Department of Medicine. At the core of CHAMP are principles of care for the older patient in the hospital setting, with an emphasis on identifying and providing care for the complex and frail elderly with nongeriatrician inpatient medicine faculty as the primary teachers of these materials. The overall educational goals of the CHAMP FDP are the following: (1) to train hospitalists and general internists to recognize opportunities to teach geriatric medicine topics specific to the care of the hospitalized older patient; (2) to create teaching materials, tools, and methods that can be used in the busy medical inpatient setting at the bedside; (3) to create materials and tools that facilitate teaching the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) core competencies14 during ward rounds; and (4) to increase the frequency and effectiveness with which this geriatrics content is taught in the hospital setting. This article describes the development and refinement of the CHAMP FDP and evaluation results to date.

METHODS

The CHAMP FDP was developed by a core group of geriatricians, hospitalists, general medicine faculty, and PhD educators from the Office of the Dean at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine. The core group piloted the FDP for themselves in spring 2004, and the FDP was offered to target learners annually from 2004 to 2006.

CHAMP Participants

The targeted faculty learners for the CHAMP FDP were hospitalists and general internists who attend on an inpatient medicine service for 1 to 4 months yearly. CHAMP Faculty Scholars were self‐selected from the eligible faculty of the University of Chicago. Approximately one‐third of the CHAMP Faculty Scholars held significant administrative and/or teaching positions in the Department of Medicine, residency program, or medical school. Overall, general internist and hospitalist faculty members of the University of Chicago are highly rated inpatient teachers with a 2004‐2007 average overall resident teaching rating of 3.79 (standard deviation = 0.53) on a scale of 1 to 4 (4 = outstanding). For each yearly cohort, we sought to train 8 to 10 Faculty Scholars. The Donald W. Reynolds Foundation grant funds supported the time of the Faculty Scholars to attend the CHAMP FDP 4 hours weekly for the 12 weeks of the course with release from a half‐day of outpatient clinical duties per week for the length of the FDP. Scholars also received continuing medical education credit for time spent in the FDP.

CHAMP Course Design, Structure, and Content

Design and Structure

The CHAMP FDP consists of twelve 4‐hour sessions given once weekly from September through November of each calendar year. Each session is composed of discrete teaching modules. During the first 2 hours of each session, 1 or 2 modules cover inpatient geriatric medicine content. The remaining 2 hours are devoted to modules consisting of the Stanford FDP for Medical Teachers: Improving Clinical Teaching (first 7 sessions)15, 16 and a course developed for the CHAMP FDP named Teaching on Today's Wards (remaining 5 sessions).

In addition to the overarching goals of the CHAMP FDP, each CHAMP module has specific learning objectives and an evaluation process based on the standard precepts of curriculum design.17 Further modifications of the CHAMP content and methods were strongly influenced by subsequent formal evaluative feedback on the course content, materials, and methods by the Faculty Scholars in each of the 4 FDP groups to date.

Geriatrics Content

The FDP geriatrics content and design model were developed as follows: reviewing existing published geriatrics curricular materials,5, 6, 8, 18 including high‐risk areas of geriatric hospital care;1922 drawing from the experience of the inpatient geriatric evaluation and treatment units;2325 and reviewing the Joint Commission mandates26 that have a particular impact on the care of the older hospitalized patients (eg, high‐risk medications, medication reconciliation, restraint use, and transitions of care). Final curricular materials were approved by consensus of the University of Chicago geriatrics/hospitalist core CHAMP faculty. A needs assessment surveying hospitalists at a regional Society of Hospital Medicine meeting showed a strong concordance between geriatrics topics that respondents thought they were least confident about in their knowledge, that they thought would be most useful to learn, and that we proposed for the core geriatrics topics for the CHAMP FDP, including pharmacy of aging, pressure ulcers, delirium, palliative care, decision‐making capacity, and dementia.27

Each geriatric topic is presented in 30‐ to 90‐minute teaching sessions with didactic lectures and case‐based discussions and is organized around 4 broad themes (Table 1). These lectures emphasize application of the content to bedside teaching during hospital medicine rounds. For example, the session on dementia focuses on assessing decision‐making capacity, the impact of dementia on the care of other medical illnesses and discharge decisions, dementia‐associated frailty with increased risk of hospitalization‐related adverse outcomes, and pain assessment in persons with dementia.

|

| Theme 1: Identify the frail/vulnerable elder |

| Identification and assessment of the vulnerable hospitalized older patient |

| Dementia in hospitalized older medical patients: Recognition of and screening for dementia, assessment of medical decision‐making capacity, implications for the treatment of nondementia illness, pain assessment, and improvement of the posthospitalization transition of care |

| Theme 2: Recognize and avoid hazards of hospitalization |

| Delirium: Diagnosis, treatment, risk stratification, and prevention |

| Falls: Assessment and prevention |

| Foley catheters: Scope of the problem, appropriate indications, and management |

| Deconditioning: Scope of the problem and prevention |

| Adverse drug reactions and medication errors: Principles of drug review |

| Pressure ulcers: Assessment, treatment, and prevention |

| Theme 3: Palliate and address end‐of‐life issues |

| Pain control: General principles and use of opiates |

| Symptom management in advanced disease: Nausea |

| Difficult conversations and advance directives |

| Hospice and palliative care and changing goals of care |

| Theme 4: Improve transitions of care |

| The ideal hospital discharge: Core components and determining destination |

| Destinations of posthospital care: Nursing homes for skilled rehabilitation and long‐term care |

The CHAMP materials created for teaching each topic at the bedside included topic‐specific teaching triggers, clinical teaching questions, and summary teaching points. The bedside teaching materials and other teaching tools, such as pocket cards with teaching triggers and clinical content (see the example in the appendix), commonly used geriatric measures (eg, the Confusion Assessment Method for delirium),28 and sample forms for teaching aspects of practice‐based learning and improvement and systems‐based practice, were available to Faculty Scholars electronically on the University of Chicago Course Management System (the CHALK E‐learning Web site). The CHAMP materials are now published at the University of Chicago Web site (

Teaching Content

The material referring to the process of teaching has been organized under 4 components in the CHAMP FDP.

The Stanford FDP for Medical Teachers15, 16

This established teaching skills course uses case scenarios and practice sessions to hone skills in key elements of teaching: learning climate, control of session, communication of goals, promotion of understanding and retention, evaluation, feedback, and promotion of self‐directed learning. This portion of the FDP was taught by a University of Chicago General Medicine faculty member trained and certified to teach the course at Stanford.

Teaching on Today's Wards

The Teaching on Today's Wards component was developed specifically for CHAMP to address the following: (1) to improve bedside teaching in the specific setting of the inpatient wards; (2) to increase the amount of geriatric medicine content taught by nongeriatrics faculty during bedside rounds; and (3) to teach the specific ACGME core competencies of professionalism, communication, practice‐based learning and improvement, and systems‐based practice during ward rounds (Table 2).

| ACGME Core Competency | Addressed in CHAMP Curriculum |

|---|---|

| |

| Knowledge/patient care | All geriatric lectures (see Table 1) |

| Professionalism | Geriatric lectures |

| 1. Advance directives and difficult conversations | |

| 2. Dementia: Decision‐making capacity | |

| Teaching on Today's Wards exercises and games | |

| 1. Process mapping | |

| 2. I Hope I Get a Good Team game | |

| 3. Deciding What To Teach/Missed Teaching Opportunities game | |

| Communication | Geriatric lectures |

| 1. Advance directives and difficult conversations | |

| 2. Dementia: Decision‐making capacity | |

| 3. Destinations for posthospital care: Nursing homes | |

| Teaching on Today's Wards exercises and games | |

| 1. Process mapping | |

| 2. Deciding What To Teach/Missed Teaching Opportunities game | |

| Systems‐based practice | Geriatric lectures |

| 1. Frailty: Screening | |

| 2. Delirium: Screening and prevention | |

| 3. Deconditioning: Prevention | |

| 4. Falls: Prevention | |

| 5. Pressure ulcers: Prevention | |

| 6. Drugs and aging: Drug review | |

| 7. Foley catheter: Indications for use | |

| 8. Ideal hospital discharge | |

| Teaching on Today's Wards exercises and games | |

| 1. Process mapping | |

| 2. Deciding What To Teach/Missed Teaching Opportunities game | |

| 3. Quality improvement projects | |

| Practice‐based learning and improvement | Teaching on Today's Wards exercises and games |

| 1. Case audit | |

| 2. Census audit | |

| 3. Process mapping | |

Session one of Teaching on Today's Wards takes the Faculty Scholars through an exploration of their teaching process on a postcall day using process mapping.29, 30 This technique, similar to constructing a flow chart, involves outlining the series of steps involved in one's actual (not ideal) process of postcall teaching. Faculty Scholars then explore how to recognize opportunities and add geriatric topics and the ACGME core competencies to their teaching on the basis of their own teaching process, skill sets, and clinical experience.

Session two explores goal setting, team dynamics, and the incorporation of more geriatrics teaching into the Faculty Scholar's teaching agenda through a series of interactive card game exercises facilitated in small group discussion. Card game 1, I Hope I Get a Good Team, allows learners to practice goal setting for their inpatient team using a hypothetical game card team based on the learning level, individuals' strengths and weaknesses, and individuals' roles in the team hierarchy. Card game 2, Deciding What To Teach/Missed Opportunities, helps learners develop a teaching agenda on any set of patients that incorporates the CHAMP geriatric topics and the ACGME core competencies.

Sessions three and four teach learners about the systems‐based practice and practice‐based learning and improvement competencies, including an introduction to quality improvement. These interactive sessions introduce Faculty Scholars to the plan‐do‐study‐act method,31 using the example of census and case audits32 to provide an objective and structured method of assessing care. These audits provide a structure for the medical team to review its actual care and management practices and for faculty to teach quality improvement. Examples of census audits developed by CHAMP faculty, including deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis, Foley catheter use, and use of proton pump inhibitors, provide models for the faculty learners to create their own audits.

The fifth session focuses on developing skills for life‐long learning. Based on previous work on medical education and evidence‐based medicine,33, 34 these sessions provide learners with a framework to identify and address knowledge gaps, obtain effective consultation, ask pertinent questions of learners, and self‐assess their teaching skills.

Observed Structured Teaching Exercises

Observed structured teaching exercises allow the deliberate practice of teaching new curricular materials and skills and have been shown to improve teaching skills for both faculty and resident teachers using standardized students in a simulated teaching environment.3537 The observed structured teaching exercises developed for CHAMP allow the Faculty Scholars to practice teaching geriatrics content using the one‐minute preceptor teaching method.38

Commitment to Change (CTC) Contracts

CTC contracts provide a method for sustaining CHAMP teaching. At the end of the FDP, we ask Faculty Scholars to sign a CTC contract,39, 40 selecting at least 1 geriatric topic and 1 topic from Teaching on Today's Wards to teach in future inpatient teaching attending months. Over the year(s) following the FDP, the CHAMP project director frequently contacts the Faculty Scholars via e‐mail and phone interviews before, during, and after each month of inpatient service. The CTC contract is formally reviewed and revised annually with each CHAMP Faculty Scholar by the CHAMP project director and a core CHAMP faculty member.

Evaluation

A comprehensive multilevel evaluation scheme was developed based on the work of Kirkpatrick,41 including participant experience and teaching and subsequent clinical outcomes. This article reports only on the knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral self‐report data collected from participants, and remaining data will be presented in future articles.

The evaluation of the FDP program includes many commonly used methods for evaluating faculty learners, including recollection and retention of course content and self‐reported behavioral changes regarding the incorporation of the material into clinical teaching and practice. The more proximal evaluation includes precourse and postcourse performance on a previously validated geriatric medicine knowledge test,4244 precourse and postcourse performance on a validated survey of attitudes regarding older persons and geriatric medicine,45 a self‐assessment survey measuring self‐reported importance of and confidence in practicing and teaching geriatric skills, and Faculty Scholars' reports of subsequent frequency of teaching on the geriatric medicine and Teaching on Today's Wards content.

Faculty Scholars' feedback regarding their reaction to and satisfaction with the CHAMP FDP includes immediate postsession evaluations of each individual CHAMP FDP session and its content.

Analyses

We calculated the overall satisfaction of the FDP by aggregating evaluations for all session modules across the 4 cohorts. Satisfaction was measured with 6 questions, which included an overall satisfaction question and were answered with 5‐point Likert scales.

Pre‐CHAMP and post‐CHAMP scores on the geriatrics knowledge test and geriatrics attitude scale were calculated for each participant and compared with paired‐sample t tests. Composite scores for the self‐reported behavior for importance of/confidence in practice and importance of/confidence in teaching were calculated for each set of responses from each participant. The average scores across all 14 geriatrics content items for importance of/confidence in practice and importance of/confidence in teaching were calculated pre‐CHAMP and post‐CHAMP and compared with a paired‐sample t test. Similarly, self‐reported behavior ratings of importance of/confidence in teaching were calculated by the averaging of responses across the 10 Teaching on Today's Wards items. Pre‐CHAMP and post‐CHAMP average scores were compared with paired‐sample t tests on SPSS version 14 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Data from the pilot sessions were included in the analyses to provide adequate power.

RESULTS

We pilot‐tested the format, materials, methods, and evaluation components of the CHAMP FDP with the CHAMP core faculty in the spring of 2004. The revised CHAMP FDP was given in the fall of 2004 to the first group of 8 faculty learners. Similar annual CHAMP FDPs have occurred since 2004, with a total of 29 Faculty Scholars by 2006. This includes approximately half of the University of Chicago general medicine faculty and the majority of the hospitalist faculty. Geriatrics fellows, a medicine chief resident, and other internal medicine subspecialists have also taken the CHAMP FDP. The average evaluations of all CHAMP sessions by all participants are shown in Table 3.

| Rating Criteria* | Average (SD) | N |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Teaching methods were appropriate for the content covered. | 4.5 0.8 | 571 |

| The module made an important contribution to my practice. | 4.4 0.9 | 566 |

| Supplemental materials were effectively used to enhance learning. | 4.0 1.6 | 433 |

| I feel prepared to teach the material covered in this module. | 4.1 1.0 | 567 |

| I feel prepared to incorporate this material into my practice. | 4.4 0.8 | 569 |

| Overall, this was a valuable educational experience. | 4.5 0.8 | 565 |

Faculty Scholars rated the FDP highly regarding preparation for teaching and incorporation of the material into their teaching and practice. Likewise, qualitative comments by the Faculty Scholars were strongly supportive of CHAMP:

Significantly more aware and confident in teaching around typical geriatric issues present in our patients.

Provided concrete, structured ideas about curriculum, learning goals, content materials and how to implement them.

The online teaching resources were something I used on an almost daily basis.

Wish we had this for outpatient.

CHAMP had a favorable impact on the Faculty Scholars across the domains of knowledge, attitudes, and perceived behavior change (Table 4). Significant differences on paired‐sample t tests found significant improvement on all but one measure (importance of teaching). After the CHAMP program, Faculty Scholars were more knowledgeable about geriatrics content (P = 0.023), had more positive attitudes to older patients (P = 0.049), and had greater confidence in their ability to care for older patients (P < 0.001) and teach geriatric medicine skills (P < 0.001) and Teaching on Today's Wards content (P < 0.001). There was a significant increase in the perceived importance of practicing the learned skills (P = 0.008) and Teaching on Today's Wards (P = 0.001). The increased importance of teaching geriatrics skills was marginally significant (P = 0.064).

| Domain | N | Average Response | SE | P Value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐CHAMP | Post‐CHAMP | |||||

| ||||||

| Knowledge | Geriatric medicine knowledge test | 21 | 62.14 | 68.05 | 2.40 | 0.023 |

| Attitudes | Geriatrics attitude scale | 26 | 56.86 | 58.38 | 0.736 | 0.049 |

| Self‐report behavior change | Importance of practice | 28 | 4.40 | 4.62 | 0.078 | 0.008 |

| Confidence in practice | 28 | 3.59 | 4.33 | 0.096 | <0.001 | |

| Importance of teaching | 27 | 4.52 | 4.66 | 0.074 | 0.064 | |

| Confidence in teaching | 27 | 3.42 | 4.47 | 0.112 | <0.001 | |

| Importance of Teaching on Today's Wards∥ | 27 | 3.92 | 4.30 | 0.093 | 0.001 | |

| Confidence in Teaching on Today's Wards∥ | 27 | 2.81 | 4.05 | 0.136 | <0.001 | |

DISCUSSION

Central to CHAMP's design are (1) the creation of teaching materials and teaching resources that specifically address the challenges of teaching the care of the hospitalized older patient in busy hospital settings, (2) the provision of methods to reinforce the newly learned geriatrics teaching skills, and (3) a multidimensional evaluation scheme. The enthusiastic response to the CHAMP FDP and the evaluation results to date support the relevance and importance of CHAMP's focus, materials, and educational methods. The ideal outcome for our CHAMP FDP graduates is more informed, confident, and frequent teaching of geriatrics topics keyed to quality improvement and systems of care through a more streamlined but personalized bedside teaching process.13, 46 The CHAMP Faculty Scholar graduates' self‐report surveys of their performance and teaching of CHAMP course geriatrics skills did reveal a significant shift in clinical behavior, teaching, and confidence. Although the strongest indicator of perceived behavior change was in the enhanced self‐confidence in practicing and teaching, the significant changes in knowledge and attitude reinforce our observations of a shift in the mindset about teaching and caring for hospitalized elderly patients. This provides strong evidence for the efficacy of the CHAMP course in positively influencing participants.

Our biggest challenge with the CHAMP FDP was providing enough ongoing support to reinforce learning with an eye on the greater goal of changing teaching behaviors and clinical outcomes. After pilot testing, we added multiple types of support and follow‐up to the FDP: observed structured teaching exercises to practice CHAMP geriatrics content and teaching skills; modification of Teaching on Today's Wards through the addition of practice‐oriented exercises, games, and tutorials; frequent contact with our Faculty Scholar graduates post‐CHAMP FDP through CTC contracts; annual Faculty Scholars reunions; and continued access for the scholars to CHAMP materials on our Web site. Maintaining face‐to‐face contact between CHAMP core faculty and Faculty Scholars once the latter have finished the FDP has been challenging, largely because of clinical and teaching obligations over geographically separate sites. To overcome this, we are working to integrate CHAMP core faculty into hospitalist and general medicine section lecture series, increasing the frequency of CHAMP reunions, renewing CTC contracts with the Faculty Scholar graduates annually, and considering the concept of CHAMP core faculty guests attending during Faculty Scholars inpatient ward rounds.47

The CHAMP FDP and our evaluations to date have several limitations. First, FDP Scholars were volunteer participants who may have been more motivated to improve their geriatric care and teaching than nonparticipants. However, FDP Scholars had only moderate levels of geriatrics knowledge, attitudes, and confidence in their teaching on baseline testing and showed marked improvements in these domains after the FDP. In addition, Scholars' FDP participation was made possible by a reduction of other clinical obligations through direct reimbursement to their sections with CHAMP funds. Other incentives for CHAMP participation could include its focus on generalizable bedside teaching skills and provision of specific techniques for teaching the ACGME core competencies and quality improvement while using geriatrics content. Although the CHAMP FDP in its 48‐hour format is not sustainable or generalizable, the FDP modules and CHAMP materials were specifically designed to be usable in small pieces that could be incorporated into existing teaching structures, grand rounds, section meetings, teacher conferences, and continuing medical education workshops. CHAMP core group members have already presented and taught CHAMP components in many venues (see Dissemination on the CHAMP Web site). The excitement generated by CHAMP at national and specialty meetings, including multiple requests for materials, speaks to widespread interest in our CHAMP model. We are pursuing the creation of a mini‐CHAMP, an abbreviated FDP with an online component. These activities as well as feedback from users of CHAMP materials from the CHAMP Web site and the Portal of Geriatric Online Education will provide important opportunities for examining the use and acceptance of CHAMP outside our institution.

Another limitation of the CHAMP FDP is reliance on FDP Scholar self‐assessment in several of the evaluation components. Some studies have shown poor concordance between physicians' self‐assessment and external assessment over a range of domains.48 However, others have noted that despite these limitations, self‐assessment remains an essential tool for enabling physicians to discover the motivational discomfort of a performance gap, which may lead to changing concepts and mental models or changing work‐flow processes.49 Teaching on Today's Wards sessions in CHAMP emphasize self‐audit processes (such as process mapping and census audits) that can augment self‐assessment. We used such self‐audit processes in 1 small pilot study to date, providing summative and qualitative feedback to a group of FDP Scholars on their use of census audits.

However, the evaluation of the CHAMP FDP is enhanced by a yearly survey of all medical residents and medical students and by the linking of the teaching reported by residents and medical students to specific attendings. We have begun the analysis of resident perceptions of being taught CHAMP geriatrics topics by CHAMP faculty versus non‐CHAMP faculty. In addition, we are gathering data on patient‐level process of care and outcomes tied to the CHAMP FDP course session objectives by linking to the ongoing University of Chicago Hospitalist Project, a large clinical research project that enrolls general medicine inpatients in a study examining the quality of care and resource allocation for these patients.50 Because the ultimate goal of CHAMP is to improve the quality of care and outcomes for elderly hospitalized patients, the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project infrastructure was modified by the incorporation of the Vulnerable Elder Survey‐1351 and a process‐of‐care chart audit specifically based on the Assessing Care of the Vulnerable Elders Hospital Quality Indicators.52 Preliminary work included testing and validating these measures.53 Further evaluation of these clinical outcomes and CHAMP's efficacy and durability at the University of Chicago is ongoing and will be presented in future reports.

CONCLUSIONS

Through a collaboration of geriatricians, hospitalists, and general internists, the CHAMP FDP provides educational materials and methods keyed to bedside teaching in the fast‐paced world of the hospital. CHAMP improves faculty knowledge and attitudes and the frequency of teaching geriatrics topics and skills necessary to deliver quality care to the elderly hospitalized medical patient. Although the CHAMP FDP was developed and refined for use at a specific institution, the multitiered CHAMP FDP materials and methods have the potential for widespread use by multiple types of inpatient attendings for teaching the care of the older hospitalized medicine patient. Hospitalists in particular will require this expertise as both clinicians and teachers as their role, leadership, and influence continue to expand nationally.

Acknowledgements

The Curriculum for the Hospitalized Aging Medical Patient (CHAMP) Program was supported by funding from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation with matching funds from the University of Chicago Department of Medicine, by the Hartford Foundation Geriatrics Center for Excellence, and by a Geriatric Academic Career Award to Don Scott. Presentations on CHAMP and its materials include a number of national and international meeting venues, including meetings of the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Geriatrics Society, and the Association of Program Directors in Internal Medicine and the International Ottawa Conference.

APPENDIX

EXAMPLE OF A CHAMP POCKET CARD: FOLEY CATHETERS

| CHAMP: Foley Catheters | CHAMP: Inability to Void | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Catherine DuBeau, MD, Geriatrics, University of Chicago | Catherine DuBeau, MD, Geriatrics, University of Chicago | |

| 1. Does this patient have a catheter? Incorporate regular catheter checks on rounds as a practice‐based learning and improvement exercise. | 1. Is there a medical reason for this patient's inability to void? | |

| Two Basic Reasons | ||

| 2. Does this patient need a catheter? | Poor pump | |

| Only Four Indications | ▪ Meds: anticholinergics, Ca++ blockers, narcotics | |

| a. Inability to void | ▪ Sacral cord disease | |

| b. Urinary incontinence and | ▪ Neuropathy: DM, B12 | |

| ▪ Open sacral or perineal wound | ▪ Constipation/emmpaction | |

| ▪ Palliative care | Blocked outlet | |

| c. Urine output monitoring | ▪ Prostate disease | |

| ▪ Critical illnessfrequent/urgent monitoring needed | ▪ Suprasacral spinal cord disease (eg, MS) with detrusor‐sphincter dyssynergia | |

| ▪ Patient unable/unwilling to collect urine | ▪ Women: scarring, large cystocele | |

| d. After general or spinal anesthesia | ▪ Constipation/emmpaction | |

| 3. Why should catheter use be minimized? | Evaluation of Inability To Void | |

| a. Infection risk | ||

| ▪ Cause of 40% of nosocomial infections | Action Step | Possible Medical Reasons |

| b. Morbidity | ||

| ▪ Internal catheters | ||

| ○Associated with delirium | Review meds | ‐Cholinergics, narcotics, calcium channel blockers, ‐agonists |

| ○Urethral and meatal injury | ||

| ○Bladder and renal stones | ||

| ○Fever | Review med Hx | Diabetes with neuropathy, sacral/subsacral cord, B12, GU surgery or radiation |

| ○Polymicrobial bacteruria | ||

| ▪ External (condom) catheters | ||

| ○Penile cellulitus/necrosis | Physical exam | Womenpelvic for prolapse; all‐sacral root S2‐4anal wink and bulbocavernosus reflexes |

| ○Urinary retention | ||

| ○Bacteruria and infection | ||

| c. Foleys are uncomfortable/painful. | Postvoiding residual | This should have been done in the evaluation of the patient's inability to void and repeated after catheter removal with voiding trial. |

| d. Foleys are restrictive falls and delirium. | ||

| e. Cost | ||

- ,.2002 National Hospital Discharge Survey.Hyattsville, MD:National Center for Health Statistics;2002.Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics 342.

- ,,, et al.The critical shortage of geriatrics faculty.J Am Geriatr Soc.1993;41:560–569.

- ,,, et al.Development of geriatrics‐oriented faculty in general internal medicine.Ann Intern Med.2003;139:615–620.

- ,,.General internal medicine and geriatrics: building a foundation to improve the training of general internists in the care of older adults.Ann Intern Med.2003;139:609–614.

- ,.Curriculum recommendations for resident training in nursing home care. A collaborative effort of the Society of General Internal Medicine Task Force on Geriatric Medicine, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Geriatrics Task Force, the American Medical Directors Association, and the American Geriatrics Society Education Committee.J Am Geriatr Soc.1994;42:1200–1201.

- ,,,,.Curriculum recommendations for resident training in geriatrics interdisciplinary team care.J Am Geriatr Soc.1999;47:1145–1148.

- ,,,,.A national survey on the current status of family practice residency education in geriatric medicine.Fam Med.2003;35:35–41.