User login

Applying Robust Process Improvement Techniques to the Voluntary Inpatient Psychiatry Admission Process

From the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Ms. Newman), and Wake Forest Baptist Health, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine (Dr. Kramer), Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Background: Adults voluntarily admitted to inpatient behavioral health units can ask to sign a Request to Discharge (RTD) form if they would like to be discharged before the treatment team agrees that discharge is appropriate. This gives the team 72 hours to determine whether the patient is safe to discharge or to involuntarily commit the patient to the unit. At 1 medical center, patients who were offered voluntary admission often lacked complete understanding of the “72-hour rule” and the early discharge procedure.

- Methods: Robust Process Improvement® techniques were implemented to improve the admission process. Flow charts, standardized scripts, and pocket cards were distributed to relevant staff. The Request for Voluntary Admission form was revised to emphasize the “72-hour rule” and the process for requesting a RTD form.

- Results: The unit’s average overall Press Ganey score improved from 77.1 to 81.6 (P = 0.003), while the average discharge score improved from 83.0 to 87.5 (P = 0.023) following implementation of the new process.

- Conclusion: Incorporating strategies such as an opportunity to “teach back” important information about the voluntary admission process (ie, what the 72-hour rule is, what the request to discharge form is, and the possibility of involuntary commitment) allows clinicians to assess capacity while simultaneously giving patients realistic expectations of the admission. These changes can lead to improvement in patient satisfaction.

Keywords: behavioral health; communication; patient satisfaction.

Communication is paramount within medical teams to improve outcomes and strengthen rapport with patients, particularly with psychiatric patients in acute crisis. Studies

While some forms of communication are required to protect the safety of patients and others around them, other forms are required to build strong relationships with patients. However, these 2 goals do not have to be mutually exclusive in the psychiatric hospital environment. Hospitals aim to improve patient satisfaction while simultaneously providing effective communication about treatment. Studies have indicated that communication during graduate medical training may decline due to “emotional and physical brutality” associated with residency training programs.4 To ameliorate this and emphasize communication education, accredited psychiatry residency programs require residents to use structured communication tools to achieve a level 2 in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestone project for the category of patient safety and health care team.5 These standardized processes allow all patients to receive the same important information related to their care while minimizing human error. Such communication skills aim to improve health care outcomes and satisfaction for patients while also training better physicians.

For legal and ethical reasons, the adult inpatient behavioral health units at major hospitals are highly regulated. In most states, a patient who is admitted to an adult inpatient behavioral health unit on a voluntary basis can ask to sign a request to discharge (RTD) form if he or she would like to be discharged from the hospital before the treatment team sees fit.6 In most jurisdictions, this action gives the treatment team 72 hours to determine whether the patient is safe to discharge. Within that time frame, the physician must either discharge the patient, or, if it is not safe to do so, involuntarily commit him or her to the unit. In most jurisdictions, this process is commonly referred to as the “72-hour rule.”

In North Carolina, state legislation Chapter 122C, Article 5, Part 2(b) specifies: “In 24-hour facilities the application shall acknowledge that the applicant may be held by the facility for a period of 72 hours after any written request for release that the applicant may make, and shall acknowledge that the 24-hour facility may have the legal right to petition for involuntary commitment of the applicant during that period. At the time of application, the facility shall tell the applicant about procedures for discharge.”7 This requirement can be somewhat confusing for both medical team members and patients alike.

As formerly practiced on the behavioral health unit described in this report, patients offered voluntary admission status to the inpatient behavioral unit often lacked complete understanding of the 72-hour rule and the process for requesting early discharge from the facility. We hypothesized that this led to the observed patient frustration and hostility, lack of trust in the treatment team, poor attendance and participation in group therapy activities, medication refusal, and overall decreased patient satisfaction. To address this issue, this pilot project was conducted to improve the voluntary admission process on the adult inpatient unit of a major academic medical center in North Carolina.

In April 2008, The Joint Commission’s Center for Transforming Healthcare embarked on an enterprise-wide initiative called Robust Process Improvement (RPI). RPI was developed as a blended approach in applying Six Sigma, Lean, and Change Management techniques to improve medical processes and procedures. RPI techniques were applied in this study to better define the problems related to inpatient behavioral health unit admission and discharge by collecting data, obtaining staff involvement, creating a solution, and monitoring for lasting benefit.

Methods

This quality improvement project took place at an 885-bed tertiary care academic medical center with Level 1 Trauma Center designation. Institutional Review Board approval was not required because this was performed as a quality improvement project rather than an experimental clinical trial and was not designed to create new generalizable knowledge.

The techniques used to improve outcomes on the inpatient behavioral health unit included Active Listening, Elevator Speech, Statistics, Cause and Effect Diagrams, development of a Communication Plan, Brainstorming, and Standard Work. Through interviews with physician assistants, nurses, and resident physicians conducted over a 1-month period, it became clear that there was confusion among patients surrounding the voluntary admission process, the process for requesting discharge, and the possibility of a voluntary admission being converted to an involuntary one. Active listening was used to better understand the opportunities for improvement from multiple perspectives through varying stages of the admission—from the consent process in the emergency department, admission to the unit, throughout the hospital stay, to the time of discharge. The following elevator speech was used to highlight the areas of confusion and the importance of implementing change with the team involved in implementing the new admission procedures:

Our project is about improving patient understanding of the voluntary admission process to the Adult Psychiatry Unit and the 72-hour rule. This is important because the present process leads to patient misunderstanding, discontent on the unit, resistance to provided therapies, and low Press Ganey satisfaction scores. Success will look like reduced patient confusion about the 72-hour rule, increased group participation, decreased patient-staff conflict, and improved Press Ganey scores. What we are asking from you is to use a standardized, scripted informed consent process, flow chart, and pocket card during the voluntary admission process.

Additionally, brainstorming sessions were conducted with physician assistants, nurses, and residents to discuss options to improve the process and elicit a list of barriers.

Data Gathering

Several metrics were tracked to further understand the issue. Overall Press Ganey scores, in addition to admission and discharge subsection scores, were tracked for the 8 months prior to implementing the quality improvement procedures (March 2017-October 2017). Additionally, the treatment team members answered survey questions related to perceived patient understanding at the beginning of training sessions in the 5-week period immediately prior to implementing the quality improvement procedures. This survey was administered using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (frequently), and included the following questions:

- How often do you have to explain: (a) Request for Voluntary Admission form, (b) 72-Hour Rule, (c) Request to Discharge form?

- How often is there confusion about the 72-hour rule and RTD form once admitted to the adult inpatient psychiatric unit?

- How often do you need to re-explain the 72-hour rule and RTD form once admitted to the adult inpatient psychiatric unit?

In-depth interviews were conducted with 4 resident physicians, 4 physician assistants, and 3 nurses to identify specific shortcomings of the admission procedure. A key finding from these interviews was that some patients tended not to understand that the treatment team had 72 hours to respond to the RTD application. Instead, several patients had indicated that they thought that they could immediately discharge themselves since they were on the unit “voluntarily” or that they could categorically discharge themselves after 72 hours of being admitted. This feedback was crucial in determining the next steps that could be taken to minimize confusion.

Process Changes

In preparation for this quality improvement project, the language and layout of the Request for Voluntary Admission form was revised and approved internally by the hospital’s Forms Committee to emphasize the 72-hour rule and the process for completing a RTD form. Additionally, these interviews indicated that it was difficult to track patients who were admitted voluntarily versus involuntarily. To rectify this problem, a field was added to the electronic medical record system to include current psychiatric admission status, allowing the selection to be either “Voluntary” or “Involuntary.” This new field in the electronic medical record system gives nurses the ability to easily update legal status daily as appropriate, which minimizes the risk of information not being effectively communicated at shift changes, while also allowing various members of the treatment team to be updated on the admission status of each patient.

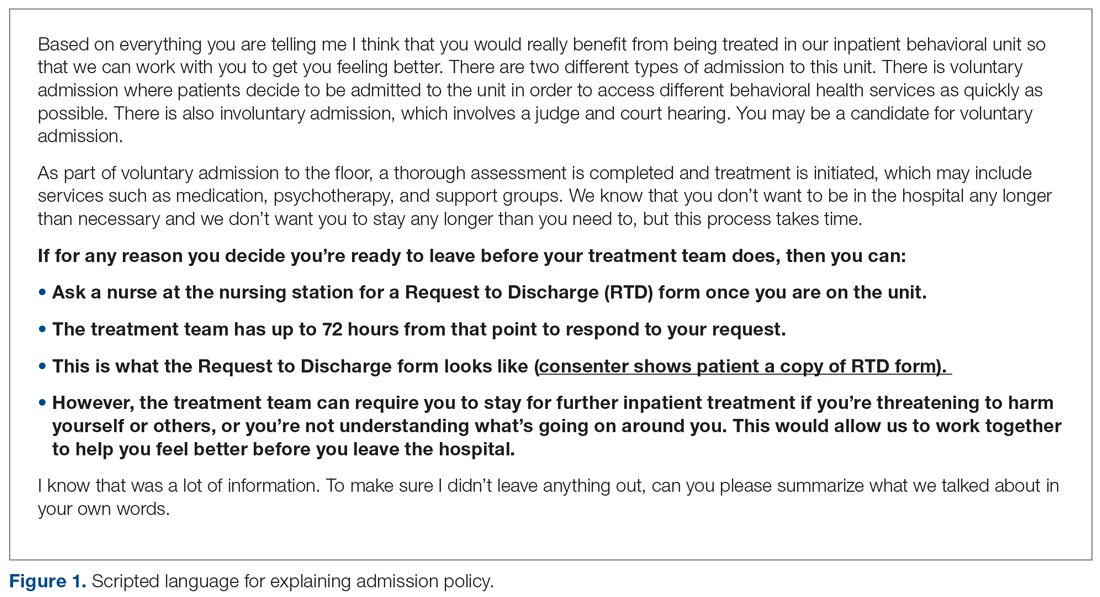

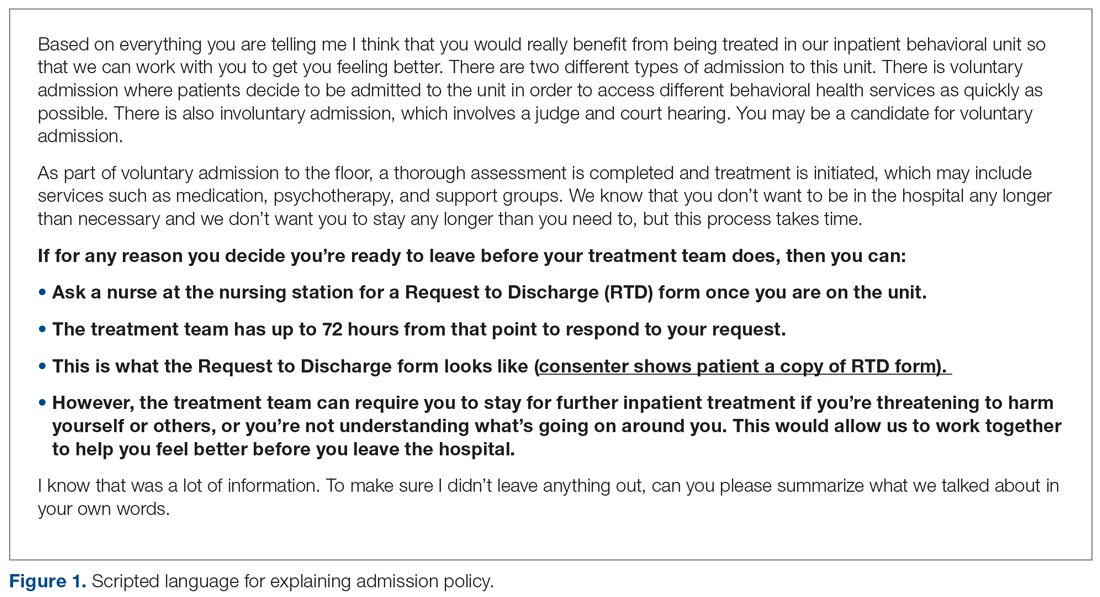

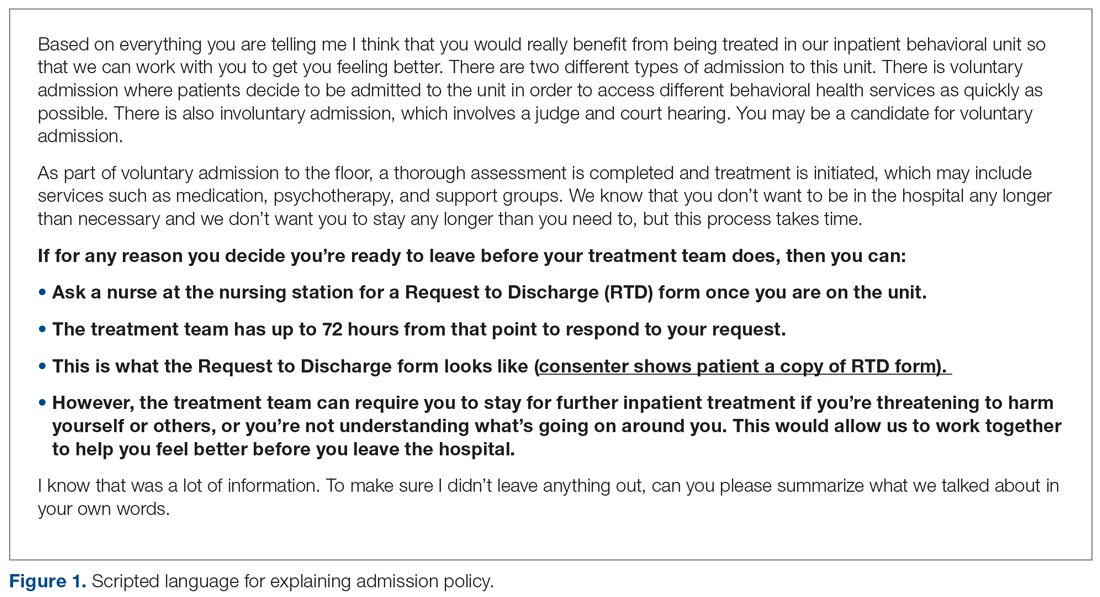

After reviewing data and obtaining staff involvement related to the problem, a new psychiatric admission and consent process was created. The new consent and admission process was characterized by a standardized procedure and scripted language to present to candidates for voluntary admission. The standardized procedure begins with the admitting staff member reading scripted consent language from a pocket card that includes 3 key points describing the voluntary admission procedure (see script in Figure 1). The first key point is to describe the 72-hour rule. Next, the staff member describes the purpose of the RTD form and shows an example to the patient. Finally, the staff member responsible for consenting describes the possibility of the patient being required to remain on the unit involuntarily in the event that he or she wants to leave before the treatment team sees fit and is deemed to be a danger to himself or herself or others.

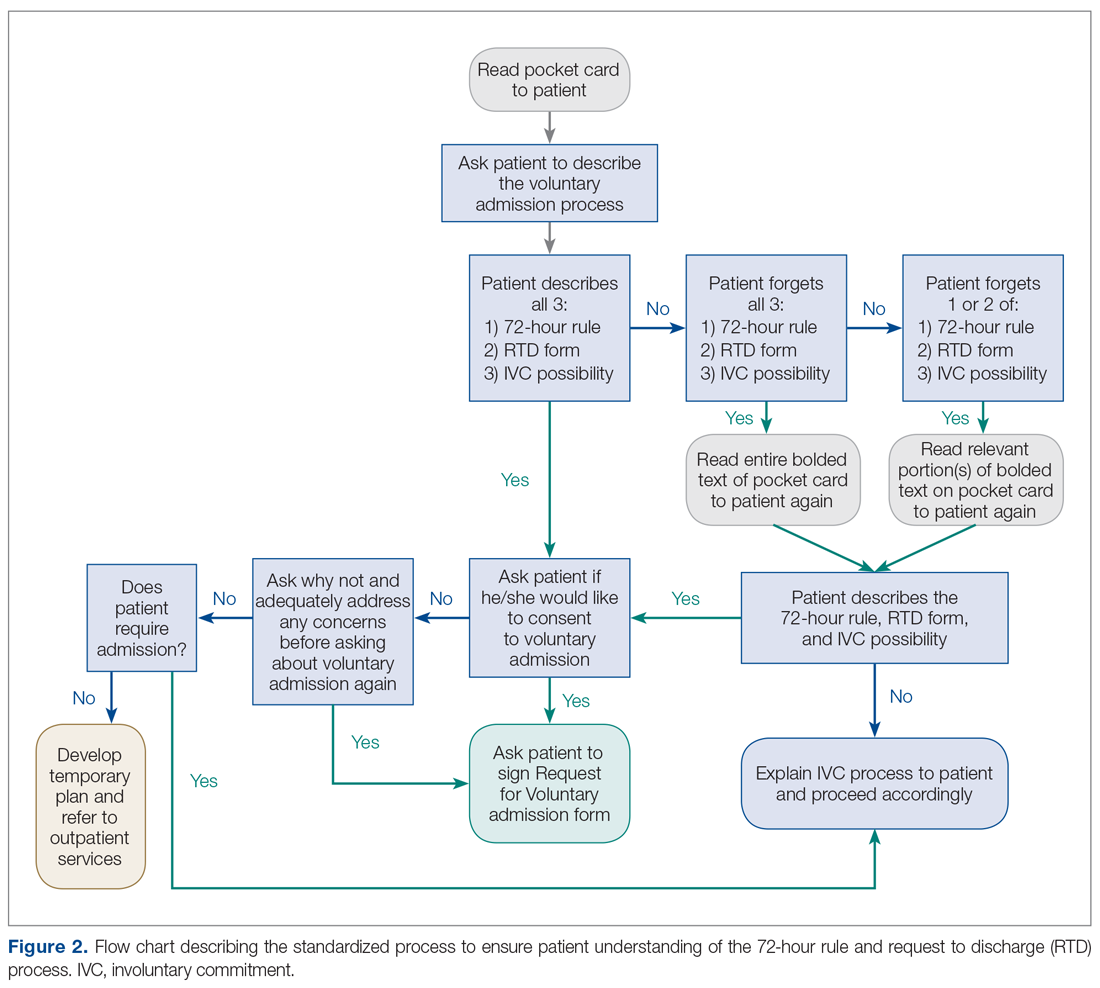

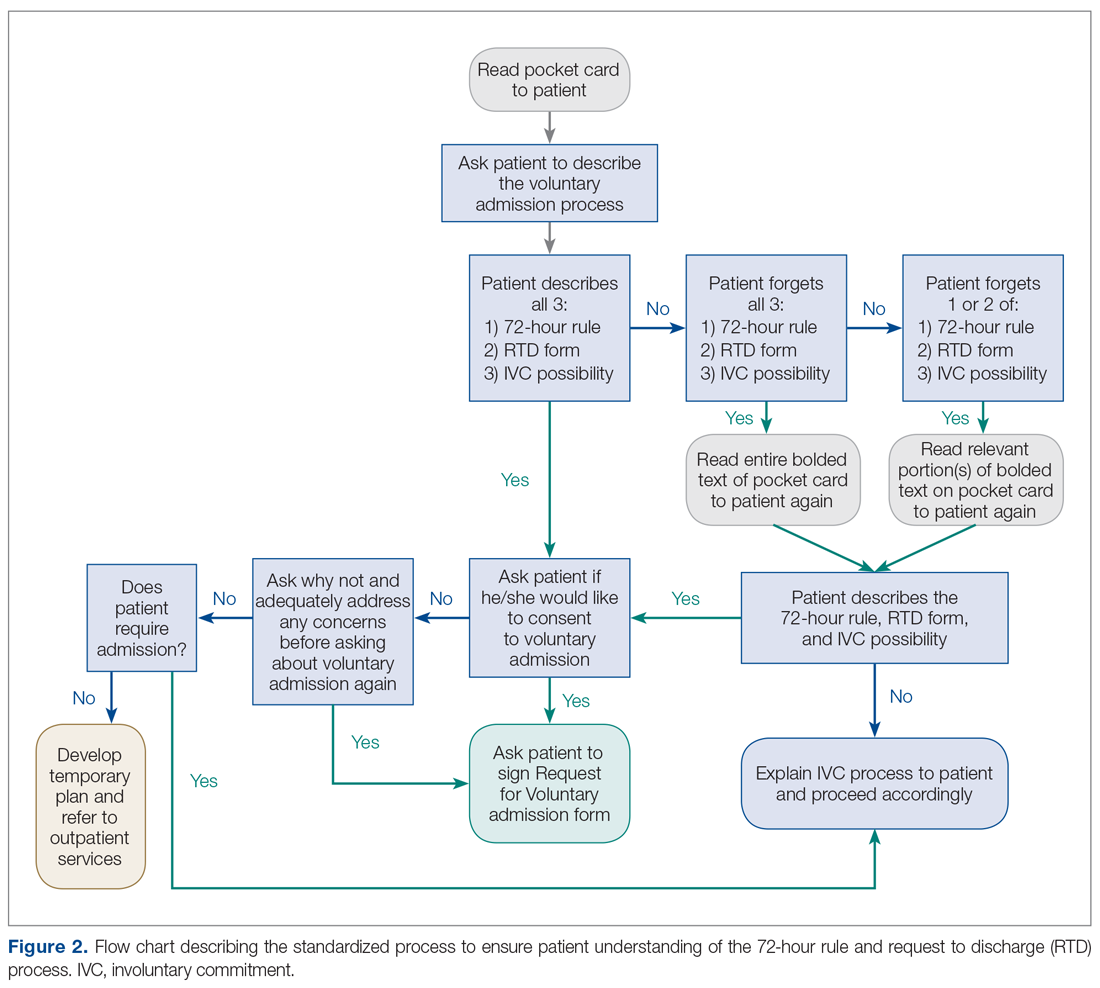

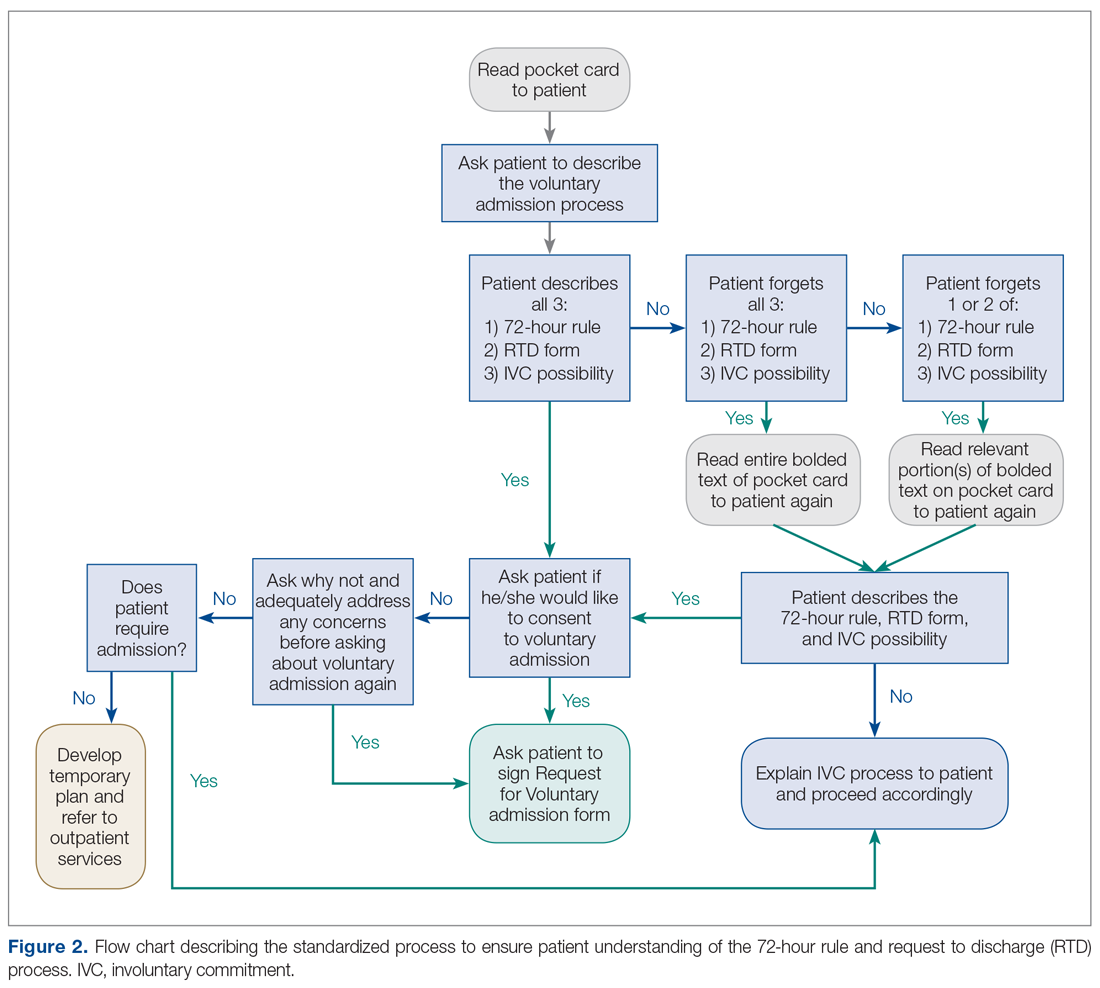

On the reverse side of the pocket card, an example of the RTD form is available to show to the patient. The subsequent teach-back procedure is summarized using the flow chart in Figure 2, and this was made available to staff who participate in the admission and discharge processes. After reading the consent script, the consenting staff member must ask the patient to recall the 3 key points. For each key point that the patient cannot recall, the relevant section of the scripted language is re-read to the patient, who is asked to explain it again. If the patient recalls the 3 key points, then he or she is deemed to have cognitive capacity and thus can become a candidate for voluntary admission.

Flow charts, scripts, and pocket cards were created and distributed to relevant physicians, physician assistants, and nurses who participate in the admission or discharge process. Additional copies of pocket cards were made available within the department. In October 2017, an attending psychiatrist and medical student trained psychiatry physician assistants, nurses, and resident physicians who participated in the admission process in the ED or patient care on the unit on how to use the new materials. The new process was first implemented on November 1, 2017.

Measurements

Press Ganey scores were compared for 8 months before and 8 months after implementing the new process to monitor changes from the patients’ perspective. Additionally, the treatment team members answered survey questions related to perceived patient understanding at the beginning of training sessions in mid-September through mid-October and again 5 weeks after the new process was implemented.

Results

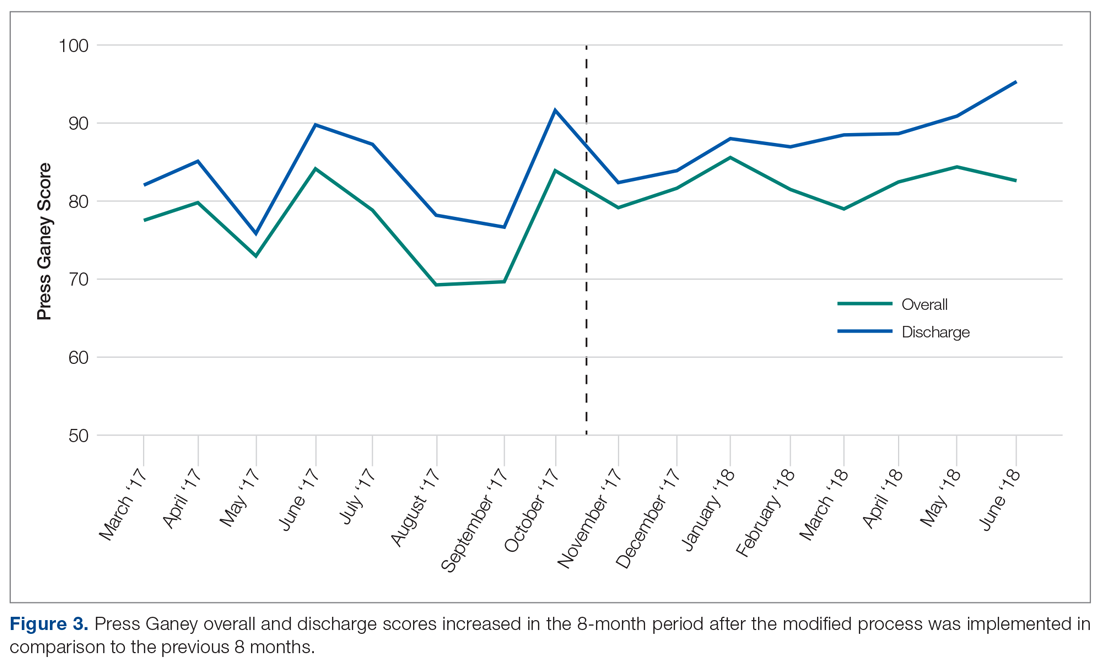

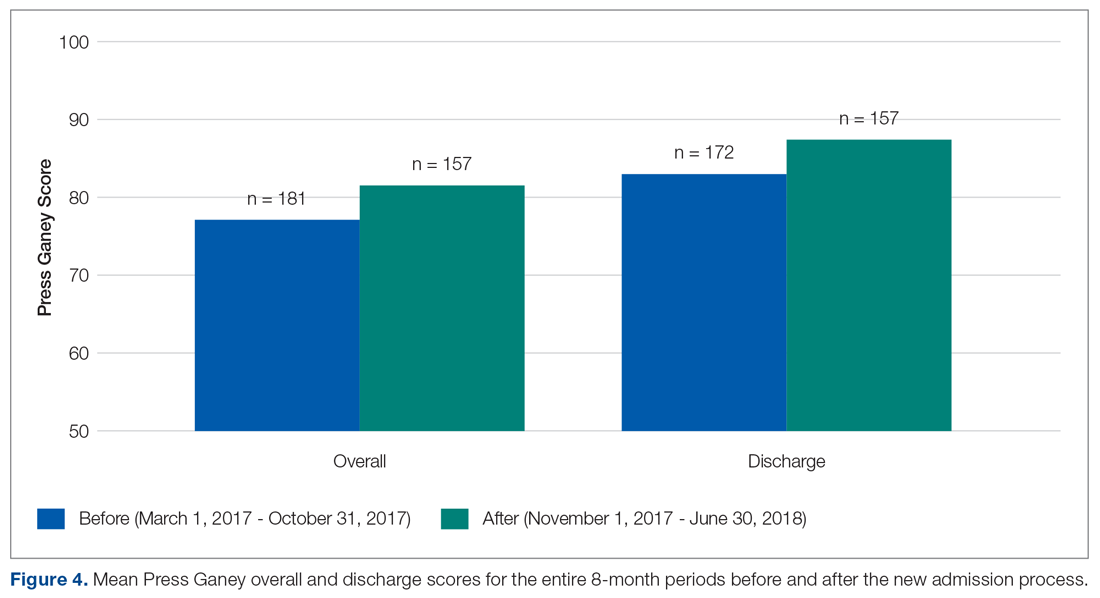

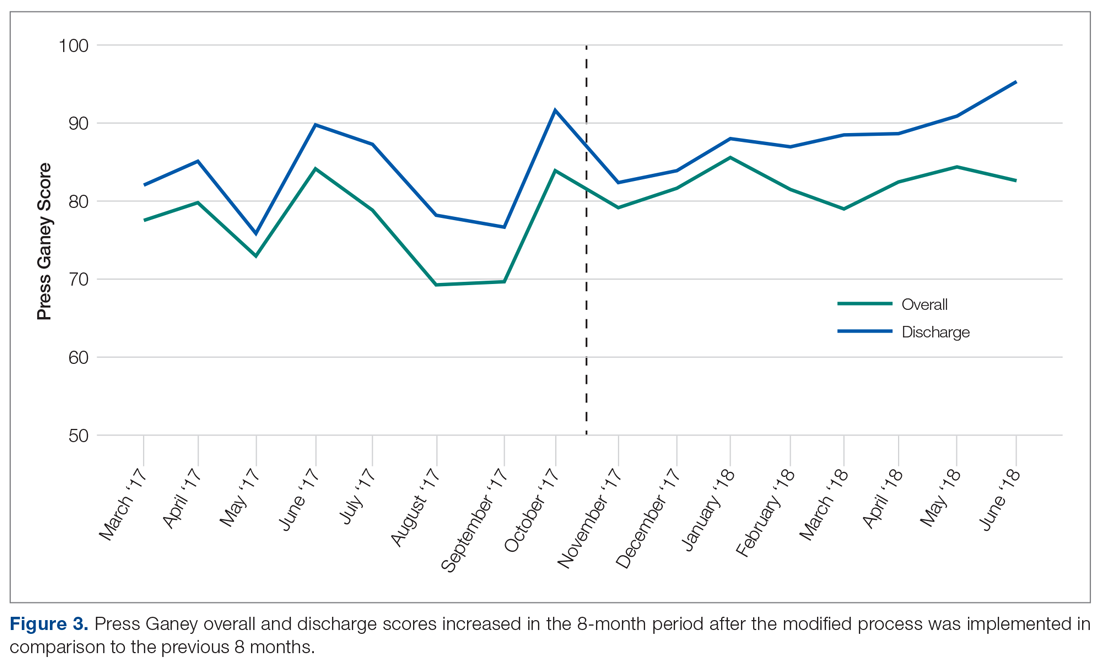

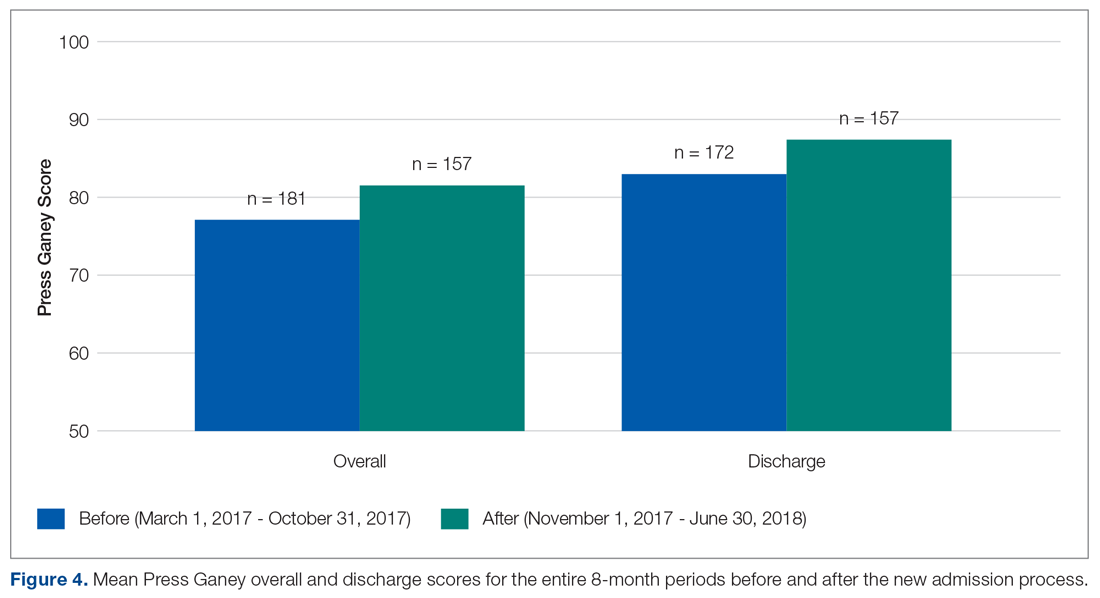

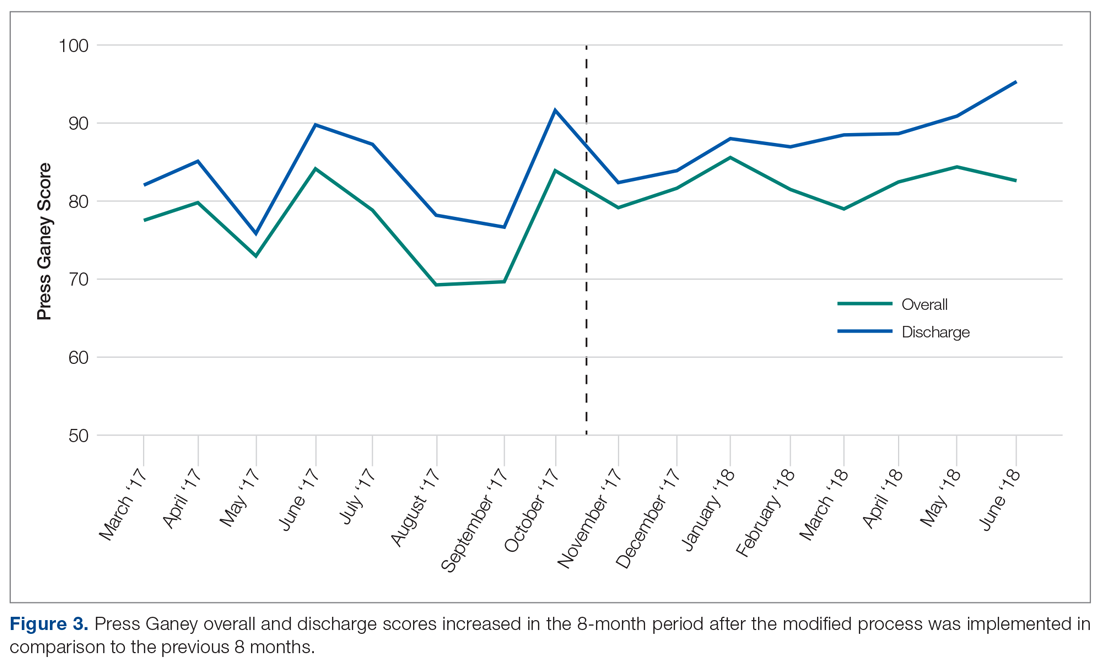

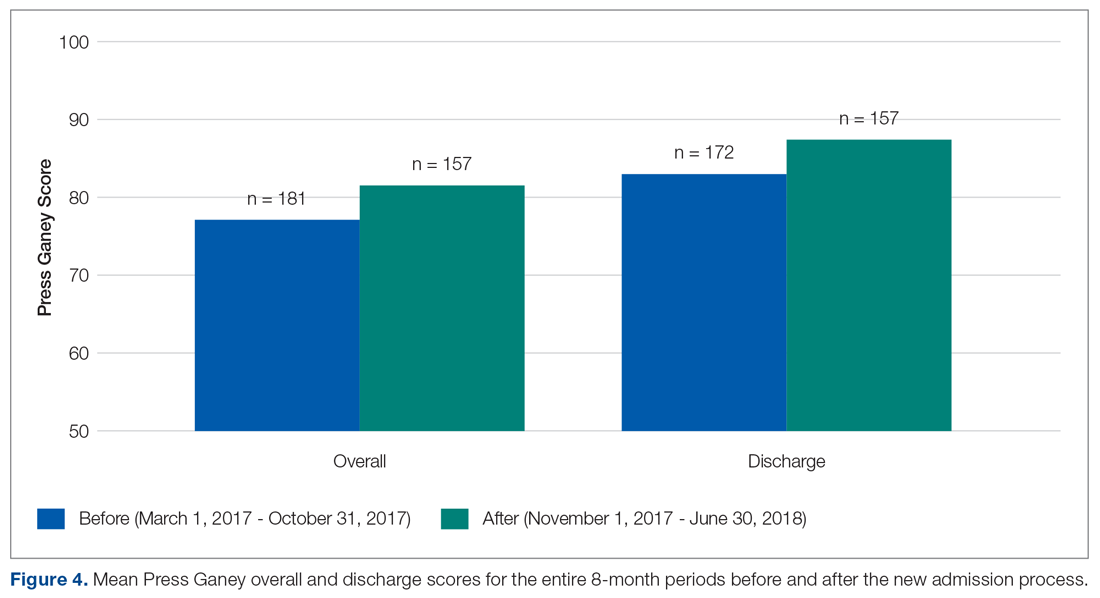

The behavioral health unit’s Press Ganey (overall and discharge) scores increased during the 8-month period following implementation of the quality improvement project (Figure 3). There was a notable upward trend of overall and discharge Press Ganey scores on a month-by-month basis from November through April. In total, 181 Press Ganey score reports were available for the 6-month period prior to the new process versus 157 score reports after (Figure 4). The average overall Press Ganey score for respondents improved from 77.1 to 81.6 (P = 0.003), while the average discharge score improved from 83.0 to 87.5 (P = 0.023).

In recent months, the behavioral health discharge satisfaction score has become one of the highest performing aspects of the department according to Press Ganey reports. From April through June 2018, the department has performed in the 98th percentile or higher in “information about patient’s rights” during admission and “discharge instructions if help is needed.”

The survey related to perceived patient satisfaction and confusion also indicated significant improvement. Survey respondents indicated that there was less confusion about the 72-hour rule and RTD form after the quality improvement procedure was implemented (P = 0.039) and that fewer attempts to re-explain these concepts were required as well (P = 0.035).

Discussion

The Press Ganey scores for this unit indicated an improvement in patient satisfaction, in particular with the discharge process. While the overall Press Ganey scores on the inpatient behavioral health unit showed a significant improvement, it remained stagnant, around 80, during the 8-month period after implementing the new standardized admission process. However, the discharge score consistently improved over the same 8 months, from 82 to 95 in the most recent month. Also, the overall and discharge scores indicated a brief spike/improvement in October, immediately preceding the implementation of the new scripted language. Given the timeline, this spike is likely related to the ongoing meetings, trainings, and awareness of the upcoming process improvement.

With hospital and health system reimbursements becoming increasingly tied with patient outcomes, quality improvement efforts to improve patient care and satisfaction are of the utmost importance. In order to develop the rapport with patients needed for a high level of cooperation and excellent outcomes on an inpatient psychiatric unit, it is essential that all patients receive specific information about what the admission entails and what the options are for being discharged from the unit. Since a voluntary admission can be converted to an involuntary admission if a patient is deemed a threat to himself or herself or others despite already signing a RTD form, it is essential that this is not only discussed prior to admission, but that these details are explicitly checked for understanding. This allows the treatment team to assess for capacity and the patient to demonstrate informed consent. Differing expectations or understanding in what the voluntary admission or discharge process entails can lead to patient frustration and hostility, lack of trust in the treatment team, poor attendance and participation in group therapy activities, and medication refusal. Altogether, this can lead to longer inpatient stays, increased costs, decreased outcomes, and decreased patient satisfaction.

These initiatives were relatively easy to implement and are backed by evidence that they ultimately increased patient satisfaction. These findings could be extended to other institutions to improve the voluntary admission process and, ultimately, the patient experience. Additionally, the methods could be applied to other patient care processes within psychiatric facilities, and to improve other aspects of the patient care experience that have room for improvement, as illustrated by the department’s Press Ganey subsection scores, or areas that the treatment team would like to focus on.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the design and evaluation of this project. The assessment of patient understanding, especially in psychiatric patients, is very difficult to quantify. The principal measure of assessing patient understanding was limited to health care professional survey results. This may have led to a slight social desirability bias. An objective assessment of understanding directly from the patients was not readily attainable in our study, but future studies could look at this metric in addition to health care professional survey results.

Additionally, the overall Press Ganey scores may be influenced by factors beyond the admission process and the applied improvement procedures. It is difficult to discern whether there were any other factors that also contributed to the overall increase. However, the discharge score was a more direct measure specifically related to the modified procedures, and the temporal association of the intervention with the increased scores suggests that the intervention was responsible.

Conclusion

Standardization of the consent process ensures that all patients receive the necessary information every time in busy clinical settings. Incorporating an opportunity to “teach back” specific important information about the voluntary admission process, specifically what the 72-hour rule is, what the RTD form is, and the possibility of involuntary commitment, allows clinicians to assess capacity, while simultaneously allowing patients to have realistic expectations of the admission. Concise, standardized answers regarding these points minimizes variation in information being dispersed and decreases the possibility of omitting important information. At a major academic medical center, easy-to-implement quality improvement techniques significantly decreased patient confusion surrounding the 72-hour rule and the RTD form, along with the frequency in which these policies needed to be re-explained on the adult inpatient psychiatric unit. These changes ultimately led to improvement in patient satisfaction, as indicated by significant improvement in both overall and discharge patient satisfaction scores.

Corresponding author: Jennifer F. Newman, 475 Vine St., Winston-Salem, NC, 27101; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Redfern E, Brown R, Vincent C. Improving communication in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:658-661.

2. Payne CE, Stein JM, Leong T, Dressler DD. Avoiding handover fumbles: a controlled trial of a structured handover tool versus traditional handover methods. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:925-932.

3. Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:149-154.

4. DiMatteo MR. The role of the physician in the emerging health care environment. Western J Med. 1998;168:328.

5. The Psychiatry Milestone Project. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1 Suppl 1):284-304.

6. Garakani A, Shalenberg E, Burstin SC, et al. Voluntary psychiatric hospitalization and patient-driven requests for discharge: a statutory review and analysis of implications for the capacity to consent to voluntary hospitalization. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22:241-249.

7. Procedure for Admission and Discharge of Clients Act, 211 § 122C-211(2014).

From the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Ms. Newman), and Wake Forest Baptist Health, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine (Dr. Kramer), Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Background: Adults voluntarily admitted to inpatient behavioral health units can ask to sign a Request to Discharge (RTD) form if they would like to be discharged before the treatment team agrees that discharge is appropriate. This gives the team 72 hours to determine whether the patient is safe to discharge or to involuntarily commit the patient to the unit. At 1 medical center, patients who were offered voluntary admission often lacked complete understanding of the “72-hour rule” and the early discharge procedure.

- Methods: Robust Process Improvement® techniques were implemented to improve the admission process. Flow charts, standardized scripts, and pocket cards were distributed to relevant staff. The Request for Voluntary Admission form was revised to emphasize the “72-hour rule” and the process for requesting a RTD form.

- Results: The unit’s average overall Press Ganey score improved from 77.1 to 81.6 (P = 0.003), while the average discharge score improved from 83.0 to 87.5 (P = 0.023) following implementation of the new process.

- Conclusion: Incorporating strategies such as an opportunity to “teach back” important information about the voluntary admission process (ie, what the 72-hour rule is, what the request to discharge form is, and the possibility of involuntary commitment) allows clinicians to assess capacity while simultaneously giving patients realistic expectations of the admission. These changes can lead to improvement in patient satisfaction.

Keywords: behavioral health; communication; patient satisfaction.

Communication is paramount within medical teams to improve outcomes and strengthen rapport with patients, particularly with psychiatric patients in acute crisis. Studies

While some forms of communication are required to protect the safety of patients and others around them, other forms are required to build strong relationships with patients. However, these 2 goals do not have to be mutually exclusive in the psychiatric hospital environment. Hospitals aim to improve patient satisfaction while simultaneously providing effective communication about treatment. Studies have indicated that communication during graduate medical training may decline due to “emotional and physical brutality” associated with residency training programs.4 To ameliorate this and emphasize communication education, accredited psychiatry residency programs require residents to use structured communication tools to achieve a level 2 in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestone project for the category of patient safety and health care team.5 These standardized processes allow all patients to receive the same important information related to their care while minimizing human error. Such communication skills aim to improve health care outcomes and satisfaction for patients while also training better physicians.

For legal and ethical reasons, the adult inpatient behavioral health units at major hospitals are highly regulated. In most states, a patient who is admitted to an adult inpatient behavioral health unit on a voluntary basis can ask to sign a request to discharge (RTD) form if he or she would like to be discharged from the hospital before the treatment team sees fit.6 In most jurisdictions, this action gives the treatment team 72 hours to determine whether the patient is safe to discharge. Within that time frame, the physician must either discharge the patient, or, if it is not safe to do so, involuntarily commit him or her to the unit. In most jurisdictions, this process is commonly referred to as the “72-hour rule.”

In North Carolina, state legislation Chapter 122C, Article 5, Part 2(b) specifies: “In 24-hour facilities the application shall acknowledge that the applicant may be held by the facility for a period of 72 hours after any written request for release that the applicant may make, and shall acknowledge that the 24-hour facility may have the legal right to petition for involuntary commitment of the applicant during that period. At the time of application, the facility shall tell the applicant about procedures for discharge.”7 This requirement can be somewhat confusing for both medical team members and patients alike.

As formerly practiced on the behavioral health unit described in this report, patients offered voluntary admission status to the inpatient behavioral unit often lacked complete understanding of the 72-hour rule and the process for requesting early discharge from the facility. We hypothesized that this led to the observed patient frustration and hostility, lack of trust in the treatment team, poor attendance and participation in group therapy activities, medication refusal, and overall decreased patient satisfaction. To address this issue, this pilot project was conducted to improve the voluntary admission process on the adult inpatient unit of a major academic medical center in North Carolina.

In April 2008, The Joint Commission’s Center for Transforming Healthcare embarked on an enterprise-wide initiative called Robust Process Improvement (RPI). RPI was developed as a blended approach in applying Six Sigma, Lean, and Change Management techniques to improve medical processes and procedures. RPI techniques were applied in this study to better define the problems related to inpatient behavioral health unit admission and discharge by collecting data, obtaining staff involvement, creating a solution, and monitoring for lasting benefit.

Methods

This quality improvement project took place at an 885-bed tertiary care academic medical center with Level 1 Trauma Center designation. Institutional Review Board approval was not required because this was performed as a quality improvement project rather than an experimental clinical trial and was not designed to create new generalizable knowledge.

The techniques used to improve outcomes on the inpatient behavioral health unit included Active Listening, Elevator Speech, Statistics, Cause and Effect Diagrams, development of a Communication Plan, Brainstorming, and Standard Work. Through interviews with physician assistants, nurses, and resident physicians conducted over a 1-month period, it became clear that there was confusion among patients surrounding the voluntary admission process, the process for requesting discharge, and the possibility of a voluntary admission being converted to an involuntary one. Active listening was used to better understand the opportunities for improvement from multiple perspectives through varying stages of the admission—from the consent process in the emergency department, admission to the unit, throughout the hospital stay, to the time of discharge. The following elevator speech was used to highlight the areas of confusion and the importance of implementing change with the team involved in implementing the new admission procedures:

Our project is about improving patient understanding of the voluntary admission process to the Adult Psychiatry Unit and the 72-hour rule. This is important because the present process leads to patient misunderstanding, discontent on the unit, resistance to provided therapies, and low Press Ganey satisfaction scores. Success will look like reduced patient confusion about the 72-hour rule, increased group participation, decreased patient-staff conflict, and improved Press Ganey scores. What we are asking from you is to use a standardized, scripted informed consent process, flow chart, and pocket card during the voluntary admission process.

Additionally, brainstorming sessions were conducted with physician assistants, nurses, and residents to discuss options to improve the process and elicit a list of barriers.

Data Gathering

Several metrics were tracked to further understand the issue. Overall Press Ganey scores, in addition to admission and discharge subsection scores, were tracked for the 8 months prior to implementing the quality improvement procedures (March 2017-October 2017). Additionally, the treatment team members answered survey questions related to perceived patient understanding at the beginning of training sessions in the 5-week period immediately prior to implementing the quality improvement procedures. This survey was administered using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (frequently), and included the following questions:

- How often do you have to explain: (a) Request for Voluntary Admission form, (b) 72-Hour Rule, (c) Request to Discharge form?

- How often is there confusion about the 72-hour rule and RTD form once admitted to the adult inpatient psychiatric unit?

- How often do you need to re-explain the 72-hour rule and RTD form once admitted to the adult inpatient psychiatric unit?

In-depth interviews were conducted with 4 resident physicians, 4 physician assistants, and 3 nurses to identify specific shortcomings of the admission procedure. A key finding from these interviews was that some patients tended not to understand that the treatment team had 72 hours to respond to the RTD application. Instead, several patients had indicated that they thought that they could immediately discharge themselves since they were on the unit “voluntarily” or that they could categorically discharge themselves after 72 hours of being admitted. This feedback was crucial in determining the next steps that could be taken to minimize confusion.

Process Changes

In preparation for this quality improvement project, the language and layout of the Request for Voluntary Admission form was revised and approved internally by the hospital’s Forms Committee to emphasize the 72-hour rule and the process for completing a RTD form. Additionally, these interviews indicated that it was difficult to track patients who were admitted voluntarily versus involuntarily. To rectify this problem, a field was added to the electronic medical record system to include current psychiatric admission status, allowing the selection to be either “Voluntary” or “Involuntary.” This new field in the electronic medical record system gives nurses the ability to easily update legal status daily as appropriate, which minimizes the risk of information not being effectively communicated at shift changes, while also allowing various members of the treatment team to be updated on the admission status of each patient.

After reviewing data and obtaining staff involvement related to the problem, a new psychiatric admission and consent process was created. The new consent and admission process was characterized by a standardized procedure and scripted language to present to candidates for voluntary admission. The standardized procedure begins with the admitting staff member reading scripted consent language from a pocket card that includes 3 key points describing the voluntary admission procedure (see script in Figure 1). The first key point is to describe the 72-hour rule. Next, the staff member describes the purpose of the RTD form and shows an example to the patient. Finally, the staff member responsible for consenting describes the possibility of the patient being required to remain on the unit involuntarily in the event that he or she wants to leave before the treatment team sees fit and is deemed to be a danger to himself or herself or others.

On the reverse side of the pocket card, an example of the RTD form is available to show to the patient. The subsequent teach-back procedure is summarized using the flow chart in Figure 2, and this was made available to staff who participate in the admission and discharge processes. After reading the consent script, the consenting staff member must ask the patient to recall the 3 key points. For each key point that the patient cannot recall, the relevant section of the scripted language is re-read to the patient, who is asked to explain it again. If the patient recalls the 3 key points, then he or she is deemed to have cognitive capacity and thus can become a candidate for voluntary admission.

Flow charts, scripts, and pocket cards were created and distributed to relevant physicians, physician assistants, and nurses who participate in the admission or discharge process. Additional copies of pocket cards were made available within the department. In October 2017, an attending psychiatrist and medical student trained psychiatry physician assistants, nurses, and resident physicians who participated in the admission process in the ED or patient care on the unit on how to use the new materials. The new process was first implemented on November 1, 2017.

Measurements

Press Ganey scores were compared for 8 months before and 8 months after implementing the new process to monitor changes from the patients’ perspective. Additionally, the treatment team members answered survey questions related to perceived patient understanding at the beginning of training sessions in mid-September through mid-October and again 5 weeks after the new process was implemented.

Results

The behavioral health unit’s Press Ganey (overall and discharge) scores increased during the 8-month period following implementation of the quality improvement project (Figure 3). There was a notable upward trend of overall and discharge Press Ganey scores on a month-by-month basis from November through April. In total, 181 Press Ganey score reports were available for the 6-month period prior to the new process versus 157 score reports after (Figure 4). The average overall Press Ganey score for respondents improved from 77.1 to 81.6 (P = 0.003), while the average discharge score improved from 83.0 to 87.5 (P = 0.023).

In recent months, the behavioral health discharge satisfaction score has become one of the highest performing aspects of the department according to Press Ganey reports. From April through June 2018, the department has performed in the 98th percentile or higher in “information about patient’s rights” during admission and “discharge instructions if help is needed.”

The survey related to perceived patient satisfaction and confusion also indicated significant improvement. Survey respondents indicated that there was less confusion about the 72-hour rule and RTD form after the quality improvement procedure was implemented (P = 0.039) and that fewer attempts to re-explain these concepts were required as well (P = 0.035).

Discussion

The Press Ganey scores for this unit indicated an improvement in patient satisfaction, in particular with the discharge process. While the overall Press Ganey scores on the inpatient behavioral health unit showed a significant improvement, it remained stagnant, around 80, during the 8-month period after implementing the new standardized admission process. However, the discharge score consistently improved over the same 8 months, from 82 to 95 in the most recent month. Also, the overall and discharge scores indicated a brief spike/improvement in October, immediately preceding the implementation of the new scripted language. Given the timeline, this spike is likely related to the ongoing meetings, trainings, and awareness of the upcoming process improvement.

With hospital and health system reimbursements becoming increasingly tied with patient outcomes, quality improvement efforts to improve patient care and satisfaction are of the utmost importance. In order to develop the rapport with patients needed for a high level of cooperation and excellent outcomes on an inpatient psychiatric unit, it is essential that all patients receive specific information about what the admission entails and what the options are for being discharged from the unit. Since a voluntary admission can be converted to an involuntary admission if a patient is deemed a threat to himself or herself or others despite already signing a RTD form, it is essential that this is not only discussed prior to admission, but that these details are explicitly checked for understanding. This allows the treatment team to assess for capacity and the patient to demonstrate informed consent. Differing expectations or understanding in what the voluntary admission or discharge process entails can lead to patient frustration and hostility, lack of trust in the treatment team, poor attendance and participation in group therapy activities, and medication refusal. Altogether, this can lead to longer inpatient stays, increased costs, decreased outcomes, and decreased patient satisfaction.

These initiatives were relatively easy to implement and are backed by evidence that they ultimately increased patient satisfaction. These findings could be extended to other institutions to improve the voluntary admission process and, ultimately, the patient experience. Additionally, the methods could be applied to other patient care processes within psychiatric facilities, and to improve other aspects of the patient care experience that have room for improvement, as illustrated by the department’s Press Ganey subsection scores, or areas that the treatment team would like to focus on.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the design and evaluation of this project. The assessment of patient understanding, especially in psychiatric patients, is very difficult to quantify. The principal measure of assessing patient understanding was limited to health care professional survey results. This may have led to a slight social desirability bias. An objective assessment of understanding directly from the patients was not readily attainable in our study, but future studies could look at this metric in addition to health care professional survey results.

Additionally, the overall Press Ganey scores may be influenced by factors beyond the admission process and the applied improvement procedures. It is difficult to discern whether there were any other factors that also contributed to the overall increase. However, the discharge score was a more direct measure specifically related to the modified procedures, and the temporal association of the intervention with the increased scores suggests that the intervention was responsible.

Conclusion

Standardization of the consent process ensures that all patients receive the necessary information every time in busy clinical settings. Incorporating an opportunity to “teach back” specific important information about the voluntary admission process, specifically what the 72-hour rule is, what the RTD form is, and the possibility of involuntary commitment, allows clinicians to assess capacity, while simultaneously allowing patients to have realistic expectations of the admission. Concise, standardized answers regarding these points minimizes variation in information being dispersed and decreases the possibility of omitting important information. At a major academic medical center, easy-to-implement quality improvement techniques significantly decreased patient confusion surrounding the 72-hour rule and the RTD form, along with the frequency in which these policies needed to be re-explained on the adult inpatient psychiatric unit. These changes ultimately led to improvement in patient satisfaction, as indicated by significant improvement in both overall and discharge patient satisfaction scores.

Corresponding author: Jennifer F. Newman, 475 Vine St., Winston-Salem, NC, 27101; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Wake Forest School of Medicine (Ms. Newman), and Wake Forest Baptist Health, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Medicine (Dr. Kramer), Winston-Salem, NC.

Abstract

- Background: Adults voluntarily admitted to inpatient behavioral health units can ask to sign a Request to Discharge (RTD) form if they would like to be discharged before the treatment team agrees that discharge is appropriate. This gives the team 72 hours to determine whether the patient is safe to discharge or to involuntarily commit the patient to the unit. At 1 medical center, patients who were offered voluntary admission often lacked complete understanding of the “72-hour rule” and the early discharge procedure.

- Methods: Robust Process Improvement® techniques were implemented to improve the admission process. Flow charts, standardized scripts, and pocket cards were distributed to relevant staff. The Request for Voluntary Admission form was revised to emphasize the “72-hour rule” and the process for requesting a RTD form.

- Results: The unit’s average overall Press Ganey score improved from 77.1 to 81.6 (P = 0.003), while the average discharge score improved from 83.0 to 87.5 (P = 0.023) following implementation of the new process.

- Conclusion: Incorporating strategies such as an opportunity to “teach back” important information about the voluntary admission process (ie, what the 72-hour rule is, what the request to discharge form is, and the possibility of involuntary commitment) allows clinicians to assess capacity while simultaneously giving patients realistic expectations of the admission. These changes can lead to improvement in patient satisfaction.

Keywords: behavioral health; communication; patient satisfaction.

Communication is paramount within medical teams to improve outcomes and strengthen rapport with patients, particularly with psychiatric patients in acute crisis. Studies

While some forms of communication are required to protect the safety of patients and others around them, other forms are required to build strong relationships with patients. However, these 2 goals do not have to be mutually exclusive in the psychiatric hospital environment. Hospitals aim to improve patient satisfaction while simultaneously providing effective communication about treatment. Studies have indicated that communication during graduate medical training may decline due to “emotional and physical brutality” associated with residency training programs.4 To ameliorate this and emphasize communication education, accredited psychiatry residency programs require residents to use structured communication tools to achieve a level 2 in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education milestone project for the category of patient safety and health care team.5 These standardized processes allow all patients to receive the same important information related to their care while minimizing human error. Such communication skills aim to improve health care outcomes and satisfaction for patients while also training better physicians.

For legal and ethical reasons, the adult inpatient behavioral health units at major hospitals are highly regulated. In most states, a patient who is admitted to an adult inpatient behavioral health unit on a voluntary basis can ask to sign a request to discharge (RTD) form if he or she would like to be discharged from the hospital before the treatment team sees fit.6 In most jurisdictions, this action gives the treatment team 72 hours to determine whether the patient is safe to discharge. Within that time frame, the physician must either discharge the patient, or, if it is not safe to do so, involuntarily commit him or her to the unit. In most jurisdictions, this process is commonly referred to as the “72-hour rule.”

In North Carolina, state legislation Chapter 122C, Article 5, Part 2(b) specifies: “In 24-hour facilities the application shall acknowledge that the applicant may be held by the facility for a period of 72 hours after any written request for release that the applicant may make, and shall acknowledge that the 24-hour facility may have the legal right to petition for involuntary commitment of the applicant during that period. At the time of application, the facility shall tell the applicant about procedures for discharge.”7 This requirement can be somewhat confusing for both medical team members and patients alike.

As formerly practiced on the behavioral health unit described in this report, patients offered voluntary admission status to the inpatient behavioral unit often lacked complete understanding of the 72-hour rule and the process for requesting early discharge from the facility. We hypothesized that this led to the observed patient frustration and hostility, lack of trust in the treatment team, poor attendance and participation in group therapy activities, medication refusal, and overall decreased patient satisfaction. To address this issue, this pilot project was conducted to improve the voluntary admission process on the adult inpatient unit of a major academic medical center in North Carolina.

In April 2008, The Joint Commission’s Center for Transforming Healthcare embarked on an enterprise-wide initiative called Robust Process Improvement (RPI). RPI was developed as a blended approach in applying Six Sigma, Lean, and Change Management techniques to improve medical processes and procedures. RPI techniques were applied in this study to better define the problems related to inpatient behavioral health unit admission and discharge by collecting data, obtaining staff involvement, creating a solution, and monitoring for lasting benefit.

Methods

This quality improvement project took place at an 885-bed tertiary care academic medical center with Level 1 Trauma Center designation. Institutional Review Board approval was not required because this was performed as a quality improvement project rather than an experimental clinical trial and was not designed to create new generalizable knowledge.

The techniques used to improve outcomes on the inpatient behavioral health unit included Active Listening, Elevator Speech, Statistics, Cause and Effect Diagrams, development of a Communication Plan, Brainstorming, and Standard Work. Through interviews with physician assistants, nurses, and resident physicians conducted over a 1-month period, it became clear that there was confusion among patients surrounding the voluntary admission process, the process for requesting discharge, and the possibility of a voluntary admission being converted to an involuntary one. Active listening was used to better understand the opportunities for improvement from multiple perspectives through varying stages of the admission—from the consent process in the emergency department, admission to the unit, throughout the hospital stay, to the time of discharge. The following elevator speech was used to highlight the areas of confusion and the importance of implementing change with the team involved in implementing the new admission procedures:

Our project is about improving patient understanding of the voluntary admission process to the Adult Psychiatry Unit and the 72-hour rule. This is important because the present process leads to patient misunderstanding, discontent on the unit, resistance to provided therapies, and low Press Ganey satisfaction scores. Success will look like reduced patient confusion about the 72-hour rule, increased group participation, decreased patient-staff conflict, and improved Press Ganey scores. What we are asking from you is to use a standardized, scripted informed consent process, flow chart, and pocket card during the voluntary admission process.

Additionally, brainstorming sessions were conducted with physician assistants, nurses, and residents to discuss options to improve the process and elicit a list of barriers.

Data Gathering

Several metrics were tracked to further understand the issue. Overall Press Ganey scores, in addition to admission and discharge subsection scores, were tracked for the 8 months prior to implementing the quality improvement procedures (March 2017-October 2017). Additionally, the treatment team members answered survey questions related to perceived patient understanding at the beginning of training sessions in the 5-week period immediately prior to implementing the quality improvement procedures. This survey was administered using a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (frequently), and included the following questions:

- How often do you have to explain: (a) Request for Voluntary Admission form, (b) 72-Hour Rule, (c) Request to Discharge form?

- How often is there confusion about the 72-hour rule and RTD form once admitted to the adult inpatient psychiatric unit?

- How often do you need to re-explain the 72-hour rule and RTD form once admitted to the adult inpatient psychiatric unit?

In-depth interviews were conducted with 4 resident physicians, 4 physician assistants, and 3 nurses to identify specific shortcomings of the admission procedure. A key finding from these interviews was that some patients tended not to understand that the treatment team had 72 hours to respond to the RTD application. Instead, several patients had indicated that they thought that they could immediately discharge themselves since they were on the unit “voluntarily” or that they could categorically discharge themselves after 72 hours of being admitted. This feedback was crucial in determining the next steps that could be taken to minimize confusion.

Process Changes

In preparation for this quality improvement project, the language and layout of the Request for Voluntary Admission form was revised and approved internally by the hospital’s Forms Committee to emphasize the 72-hour rule and the process for completing a RTD form. Additionally, these interviews indicated that it was difficult to track patients who were admitted voluntarily versus involuntarily. To rectify this problem, a field was added to the electronic medical record system to include current psychiatric admission status, allowing the selection to be either “Voluntary” or “Involuntary.” This new field in the electronic medical record system gives nurses the ability to easily update legal status daily as appropriate, which minimizes the risk of information not being effectively communicated at shift changes, while also allowing various members of the treatment team to be updated on the admission status of each patient.

After reviewing data and obtaining staff involvement related to the problem, a new psychiatric admission and consent process was created. The new consent and admission process was characterized by a standardized procedure and scripted language to present to candidates for voluntary admission. The standardized procedure begins with the admitting staff member reading scripted consent language from a pocket card that includes 3 key points describing the voluntary admission procedure (see script in Figure 1). The first key point is to describe the 72-hour rule. Next, the staff member describes the purpose of the RTD form and shows an example to the patient. Finally, the staff member responsible for consenting describes the possibility of the patient being required to remain on the unit involuntarily in the event that he or she wants to leave before the treatment team sees fit and is deemed to be a danger to himself or herself or others.

On the reverse side of the pocket card, an example of the RTD form is available to show to the patient. The subsequent teach-back procedure is summarized using the flow chart in Figure 2, and this was made available to staff who participate in the admission and discharge processes. After reading the consent script, the consenting staff member must ask the patient to recall the 3 key points. For each key point that the patient cannot recall, the relevant section of the scripted language is re-read to the patient, who is asked to explain it again. If the patient recalls the 3 key points, then he or she is deemed to have cognitive capacity and thus can become a candidate for voluntary admission.

Flow charts, scripts, and pocket cards were created and distributed to relevant physicians, physician assistants, and nurses who participate in the admission or discharge process. Additional copies of pocket cards were made available within the department. In October 2017, an attending psychiatrist and medical student trained psychiatry physician assistants, nurses, and resident physicians who participated in the admission process in the ED or patient care on the unit on how to use the new materials. The new process was first implemented on November 1, 2017.

Measurements

Press Ganey scores were compared for 8 months before and 8 months after implementing the new process to monitor changes from the patients’ perspective. Additionally, the treatment team members answered survey questions related to perceived patient understanding at the beginning of training sessions in mid-September through mid-October and again 5 weeks after the new process was implemented.

Results

The behavioral health unit’s Press Ganey (overall and discharge) scores increased during the 8-month period following implementation of the quality improvement project (Figure 3). There was a notable upward trend of overall and discharge Press Ganey scores on a month-by-month basis from November through April. In total, 181 Press Ganey score reports were available for the 6-month period prior to the new process versus 157 score reports after (Figure 4). The average overall Press Ganey score for respondents improved from 77.1 to 81.6 (P = 0.003), while the average discharge score improved from 83.0 to 87.5 (P = 0.023).

In recent months, the behavioral health discharge satisfaction score has become one of the highest performing aspects of the department according to Press Ganey reports. From April through June 2018, the department has performed in the 98th percentile or higher in “information about patient’s rights” during admission and “discharge instructions if help is needed.”

The survey related to perceived patient satisfaction and confusion also indicated significant improvement. Survey respondents indicated that there was less confusion about the 72-hour rule and RTD form after the quality improvement procedure was implemented (P = 0.039) and that fewer attempts to re-explain these concepts were required as well (P = 0.035).

Discussion

The Press Ganey scores for this unit indicated an improvement in patient satisfaction, in particular with the discharge process. While the overall Press Ganey scores on the inpatient behavioral health unit showed a significant improvement, it remained stagnant, around 80, during the 8-month period after implementing the new standardized admission process. However, the discharge score consistently improved over the same 8 months, from 82 to 95 in the most recent month. Also, the overall and discharge scores indicated a brief spike/improvement in October, immediately preceding the implementation of the new scripted language. Given the timeline, this spike is likely related to the ongoing meetings, trainings, and awareness of the upcoming process improvement.

With hospital and health system reimbursements becoming increasingly tied with patient outcomes, quality improvement efforts to improve patient care and satisfaction are of the utmost importance. In order to develop the rapport with patients needed for a high level of cooperation and excellent outcomes on an inpatient psychiatric unit, it is essential that all patients receive specific information about what the admission entails and what the options are for being discharged from the unit. Since a voluntary admission can be converted to an involuntary admission if a patient is deemed a threat to himself or herself or others despite already signing a RTD form, it is essential that this is not only discussed prior to admission, but that these details are explicitly checked for understanding. This allows the treatment team to assess for capacity and the patient to demonstrate informed consent. Differing expectations or understanding in what the voluntary admission or discharge process entails can lead to patient frustration and hostility, lack of trust in the treatment team, poor attendance and participation in group therapy activities, and medication refusal. Altogether, this can lead to longer inpatient stays, increased costs, decreased outcomes, and decreased patient satisfaction.

These initiatives were relatively easy to implement and are backed by evidence that they ultimately increased patient satisfaction. These findings could be extended to other institutions to improve the voluntary admission process and, ultimately, the patient experience. Additionally, the methods could be applied to other patient care processes within psychiatric facilities, and to improve other aspects of the patient care experience that have room for improvement, as illustrated by the department’s Press Ganey subsection scores, or areas that the treatment team would like to focus on.

Limitations

There are several limitations in the design and evaluation of this project. The assessment of patient understanding, especially in psychiatric patients, is very difficult to quantify. The principal measure of assessing patient understanding was limited to health care professional survey results. This may have led to a slight social desirability bias. An objective assessment of understanding directly from the patients was not readily attainable in our study, but future studies could look at this metric in addition to health care professional survey results.

Additionally, the overall Press Ganey scores may be influenced by factors beyond the admission process and the applied improvement procedures. It is difficult to discern whether there were any other factors that also contributed to the overall increase. However, the discharge score was a more direct measure specifically related to the modified procedures, and the temporal association of the intervention with the increased scores suggests that the intervention was responsible.

Conclusion

Standardization of the consent process ensures that all patients receive the necessary information every time in busy clinical settings. Incorporating an opportunity to “teach back” specific important information about the voluntary admission process, specifically what the 72-hour rule is, what the RTD form is, and the possibility of involuntary commitment, allows clinicians to assess capacity, while simultaneously allowing patients to have realistic expectations of the admission. Concise, standardized answers regarding these points minimizes variation in information being dispersed and decreases the possibility of omitting important information. At a major academic medical center, easy-to-implement quality improvement techniques significantly decreased patient confusion surrounding the 72-hour rule and the RTD form, along with the frequency in which these policies needed to be re-explained on the adult inpatient psychiatric unit. These changes ultimately led to improvement in patient satisfaction, as indicated by significant improvement in both overall and discharge patient satisfaction scores.

Corresponding author: Jennifer F. Newman, 475 Vine St., Winston-Salem, NC, 27101; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Redfern E, Brown R, Vincent C. Improving communication in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:658-661.

2. Payne CE, Stein JM, Leong T, Dressler DD. Avoiding handover fumbles: a controlled trial of a structured handover tool versus traditional handover methods. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:925-932.

3. Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:149-154.

4. DiMatteo MR. The role of the physician in the emerging health care environment. Western J Med. 1998;168:328.

5. The Psychiatry Milestone Project. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1 Suppl 1):284-304.

6. Garakani A, Shalenberg E, Burstin SC, et al. Voluntary psychiatric hospitalization and patient-driven requests for discharge: a statutory review and analysis of implications for the capacity to consent to voluntary hospitalization. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22:241-249.

7. Procedure for Admission and Discharge of Clients Act, 211 § 122C-211(2014).

1. Redfern E, Brown R, Vincent C. Improving communication in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:658-661.

2. Payne CE, Stein JM, Leong T, Dressler DD. Avoiding handover fumbles: a controlled trial of a structured handover tool versus traditional handover methods. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21:925-932.

3. Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgrad Med J. 2014;90:149-154.

4. DiMatteo MR. The role of the physician in the emerging health care environment. Western J Med. 1998;168:328.

5. The Psychiatry Milestone Project. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(1 Suppl 1):284-304.

6. Garakani A, Shalenberg E, Burstin SC, et al. Voluntary psychiatric hospitalization and patient-driven requests for discharge: a statutory review and analysis of implications for the capacity to consent to voluntary hospitalization. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2014;22:241-249.

7. Procedure for Admission and Discharge of Clients Act, 211 § 122C-211(2014).

Off-label prescribing: 7 steps for safer, more effective treatment

Have you noticed two curious patterns in off-label prescribing? Psychiatrists avoid agents approved for treating insomnia but prescribe anticonvulsants for a variety of unapproved uses.

Most of us prescribe medications for therapeutic uses not found in FDA-approved labeling. Among 200 psychiatrists surveyed, 65% said they had prescribed off label in the previous month, and only 4% had ever received a patient complaint about the practice.Malpractice Verdicts).

Box

Private insurance. Psychotropic costs are rising 20% a year, contributing to the nation’s annual 13% overall prescription drug cost increase.15 To control rising costs, some medical insurance plans consider off-label use as “unapproved and experimental” and deny coverage. Pharmacy benefit and self-insured employer plans may act similarly, although some states require insurers to cover off-label use of all approved edications.

Government programs. Medicaid does not exclude coverage of off-label prescriptions. How the new Medicare prescription drug plan (Part D) handles off-label prescribing remains unclear.

Why psychiatrists prescribe off-label

| Therapeutic reasons |

| Patient has a disorder for which no drug is labeled |

| Patient falls outside of labeled age or demographic group, such as children, older patients, and pregnant women |

| Patient fails to respond to labeled products |

| Off-label product may potentiate response to a labeled agent or minimize its adverse effects |

| Preferences |

| Manufacturers and respected peers promote use of off-label products as first- or second-line agents18 |

| Practitioner wishes to foster innovative treatments |

| Patients or families request an off-label drug instead of labeled alternatives |

| Practitioner avoids using a particular labeled drug or drug class |

Most state medical practice laws spell out the information required in the patient chart to demonstrate informed consent, defined variously as:

- what a reasonable provider would tell a patient

- what a reasonable patient would expect to hear from the provider

- what a patient would need to hear before deciding on a treatment course.

What the law says

Off-label prescribing is legal, common, necessary, and recognized in some states by statute and by U.S. Supreme Court review.

Court decisions. In a class action suit before the top court (Buckman Company vs. Plaintiff’s Legal Commission, 2001), 5,000 plaintiffs claimed damages from orthopedic screws and plates that were FDA-approved for use in long bones but not for use in the spine. A unanimous court held that such off-label use is an accepted and necessary offshoot of FDA regulatory function and does not interfere with the practice of medicine.

The courts also have determined that off-label use does not mean “experimental” and itself is not a risk. Off-label use may be consistent with the standard of care and does not categorically indicate negligence (though a practitioner who prescribes negligently—such as prescribing a drug to which a patient is known to be allergic—may be found liable).

Drug manufacturers’ risk. The courts recognize that patients receive prescription drugs from doctors, not directly from the manufacturers. The law thus provides some immunity to manufacturers if your patient is injured by a drug you prescribe off-label. The learned-intermediary rule says anufacturers must warn you adequately of a drug’s foreseeable risks, and you then assume the responsibility to warn the patient.

The courts recognize exceptions, though, and have required manufacturers to warn patients directly about vaccines given in mass immunizations, drugs withdrawn from the market, drugs advertised directly to consumers, and other risks.

- BMJ Publishing Group. Clinical evidence. Summary of what is known—and not known—about more than 200 medical disorders and 2,000 treatments. www.clinicalevidence.com.

- Cochrane Library of evidence-based clinical reviews. www.cochrane.org.

- Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Draft comparative effectiveness review of off-label use of atypical antipsychotic drugs. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/synthesize/reports/draft.cfm.

- Amitriptyline • Elavil, others

- Carbamazepine • Carbetrol; Epitol; Equetro; Tegretol

- Gabapentin • Gabarone; Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Trazodone • Desyrel; Trialodine

- Valproate • Depakote; Depakene

Dr. Kramer reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. McCall receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Takeda, and Wyeth, is an advisor to King Pharmaceuticals and Sepracor, and is a speaker for GlaxoSmtihKline, Sepracor, and Wyeth.

1. Lowe-Ponsford FL, Baldwin DS. Off-label prescribing by psychiatrists. Psychiatr Bull 2000;24(11):415-17.

2. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, et al. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA 2000;283(8):1025-30.

3. Kelly DL, Love RC, Mackowick M, et al. Atypical antipsychotic use in a state hospital inpatient adolescent population. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2004;14(1):75-85.

4. Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Sernyak M. From clinical trials to real-world practice: use of atypical antipsychotic medication nationally in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Med Care 2001;39(3):302-8.

5. Fountoulakis KN, Nimatoudis I, Iacovides A, Kaprinis G. Off-label indications for atypical antipsychotics: A systematic review. Ann Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2004;3(1):4.-

6. Pomerantz JM, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, et al. Prescriber intent, off-label usage, and early discontinuation of antidepressants: a retrospective physician survey and data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65(3):395-404.

1. Beck JM, Azari ED. FDA, off-label use, and informed consent. Food Drug Law J 1998;53:71-104.

8. Hepper F, Fellow-Smith E. Off-label prescribing in a community child and adolescent mental health service: Implications for information giving and informed consent. Clin Manag 2005;13(1):29-33.

9. O’Reilly JD, Dalal A. Off-label or out of bounds? Prescriber and marketer liability for unapproved uses of FDA-approved drugs. Ann Health Law 2003;12:295-324.

10. Ware JC, Pittard JT. Increased deep sleep after trazodone use: a double-blind placebo-controlled study in healthy young adults. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:18-22.

11. McCall WV. Use of off-label medications in the treatment of chronic insomnia. J Clin Sleep Med 2005;1(4):e494-5.

12. Chen H, Deshpande AD, Jiang R, Martin BC. An epidemiological investigation of off-label anticonvulsant drug use in the Georgia Medicaid population. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2005;14(9):629-38.

13. Mack A. Examination of the evidence for off-label use of gabapentin. J Manag Care Pharm 2003;9(6):559-68.

14. Citrome L, Levine J, Allingham B. Utilization of valproate: extent of inpatient use in the New York State Office of Mental Health. Psychiatr Q 1998;69(4):283-300.

15. De Leon O. Antiepileptic drugs for the acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2001;9(5):209-22.

16. Le Bon O, Murphy JR, Staner L, et al. Double-blind, placebocontrolled study of the efficacy of trazodone in alcohol postwithdrawal syndrome: polysomnographic and clinical evaluations. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2003;23(4):377-83.

17. Zuvekas SH. Prescription drugs and the changing patterns of treatment for mental disorders, 1996-2001. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(1):195-205.

18. Glick ID, Murray SR, Vasudevan P, et al. Treatment with atypical antipsychotics: new indications and new populations. J Psychiatr Res 2001;35(3):187-91.

Have you noticed two curious patterns in off-label prescribing? Psychiatrists avoid agents approved for treating insomnia but prescribe anticonvulsants for a variety of unapproved uses.

Most of us prescribe medications for therapeutic uses not found in FDA-approved labeling. Among 200 psychiatrists surveyed, 65% said they had prescribed off label in the previous month, and only 4% had ever received a patient complaint about the practice.Malpractice Verdicts).

Box

Private insurance. Psychotropic costs are rising 20% a year, contributing to the nation’s annual 13% overall prescription drug cost increase.15 To control rising costs, some medical insurance plans consider off-label use as “unapproved and experimental” and deny coverage. Pharmacy benefit and self-insured employer plans may act similarly, although some states require insurers to cover off-label use of all approved edications.

Government programs. Medicaid does not exclude coverage of off-label prescriptions. How the new Medicare prescription drug plan (Part D) handles off-label prescribing remains unclear.

Why psychiatrists prescribe off-label

| Therapeutic reasons |

| Patient has a disorder for which no drug is labeled |

| Patient falls outside of labeled age or demographic group, such as children, older patients, and pregnant women |

| Patient fails to respond to labeled products |

| Off-label product may potentiate response to a labeled agent or minimize its adverse effects |

| Preferences |

| Manufacturers and respected peers promote use of off-label products as first- or second-line agents18 |

| Practitioner wishes to foster innovative treatments |

| Patients or families request an off-label drug instead of labeled alternatives |

| Practitioner avoids using a particular labeled drug or drug class |

Most state medical practice laws spell out the information required in the patient chart to demonstrate informed consent, defined variously as:

- what a reasonable provider would tell a patient

- what a reasonable patient would expect to hear from the provider

- what a patient would need to hear before deciding on a treatment course.

What the law says

Off-label prescribing is legal, common, necessary, and recognized in some states by statute and by U.S. Supreme Court review.

Court decisions. In a class action suit before the top court (Buckman Company vs. Plaintiff’s Legal Commission, 2001), 5,000 plaintiffs claimed damages from orthopedic screws and plates that were FDA-approved for use in long bones but not for use in the spine. A unanimous court held that such off-label use is an accepted and necessary offshoot of FDA regulatory function and does not interfere with the practice of medicine.

The courts also have determined that off-label use does not mean “experimental” and itself is not a risk. Off-label use may be consistent with the standard of care and does not categorically indicate negligence (though a practitioner who prescribes negligently—such as prescribing a drug to which a patient is known to be allergic—may be found liable).

Drug manufacturers’ risk. The courts recognize that patients receive prescription drugs from doctors, not directly from the manufacturers. The law thus provides some immunity to manufacturers if your patient is injured by a drug you prescribe off-label. The learned-intermediary rule says anufacturers must warn you adequately of a drug’s foreseeable risks, and you then assume the responsibility to warn the patient.

The courts recognize exceptions, though, and have required manufacturers to warn patients directly about vaccines given in mass immunizations, drugs withdrawn from the market, drugs advertised directly to consumers, and other risks.

- BMJ Publishing Group. Clinical evidence. Summary of what is known—and not known—about more than 200 medical disorders and 2,000 treatments. www.clinicalevidence.com.

- Cochrane Library of evidence-based clinical reviews. www.cochrane.org.

- Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Draft comparative effectiveness review of off-label use of atypical antipsychotic drugs. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/synthesize/reports/draft.cfm.

- Amitriptyline • Elavil, others

- Carbamazepine • Carbetrol; Epitol; Equetro; Tegretol

- Gabapentin • Gabarone; Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Trazodone • Desyrel; Trialodine

- Valproate • Depakote; Depakene

Dr. Kramer reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. McCall receives research support from GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Takeda, and Wyeth, is an advisor to King Pharmaceuticals and Sepracor, and is a speaker for GlaxoSmtihKline, Sepracor, and Wyeth.

Have you noticed two curious patterns in off-label prescribing? Psychiatrists avoid agents approved for treating insomnia but prescribe anticonvulsants for a variety of unapproved uses.

Most of us prescribe medications for therapeutic uses not found in FDA-approved labeling. Among 200 psychiatrists surveyed, 65% said they had prescribed off label in the previous month, and only 4% had ever received a patient complaint about the practice.Malpractice Verdicts).

Box

Private insurance. Psychotropic costs are rising 20% a year, contributing to the nation’s annual 13% overall prescription drug cost increase.15 To control rising costs, some medical insurance plans consider off-label use as “unapproved and experimental” and deny coverage. Pharmacy benefit and self-insured employer plans may act similarly, although some states require insurers to cover off-label use of all approved edications.

Government programs. Medicaid does not exclude coverage of off-label prescriptions. How the new Medicare prescription drug plan (Part D) handles off-label prescribing remains unclear.

Why psychiatrists prescribe off-label

| Therapeutic reasons |

| Patient has a disorder for which no drug is labeled |

| Patient falls outside of labeled age or demographic group, such as children, older patients, and pregnant women |

| Patient fails to respond to labeled products |

| Off-label product may potentiate response to a labeled agent or minimize its adverse effects |

| Preferences |

| Manufacturers and respected peers promote use of off-label products as first- or second-line agents18 |

| Practitioner wishes to foster innovative treatments |

| Patients or families request an off-label drug instead of labeled alternatives |

| Practitioner avoids using a particular labeled drug or drug class |

Most state medical practice laws spell out the information required in the patient chart to demonstrate informed consent, defined variously as:

- what a reasonable provider would tell a patient

- what a reasonable patient would expect to hear from the provider

- what a patient would need to hear before deciding on a treatment course.

What the law says

Off-label prescribing is legal, common, necessary, and recognized in some states by statute and by U.S. Supreme Court review.

Court decisions. In a class action suit before the top court (Buckman Company vs. Plaintiff’s Legal Commission, 2001), 5,000 plaintiffs claimed damages from orthopedic screws and plates that were FDA-approved for use in long bones but not for use in the spine. A unanimous court held that such off-label use is an accepted and necessary offshoot of FDA regulatory function and does not interfere with the practice of medicine.

The courts also have determined that off-label use does not mean “experimental” and itself is not a risk. Off-label use may be consistent with the standard of care and does not categorically indicate negligence (though a practitioner who prescribes negligently—such as prescribing a drug to which a patient is known to be allergic—may be found liable).

Drug manufacturers’ risk. The courts recognize that patients receive prescription drugs from doctors, not directly from the manufacturers. The law thus provides some immunity to manufacturers if your patient is injured by a drug you prescribe off-label. The learned-intermediary rule says anufacturers must warn you adequately of a drug’s foreseeable risks, and you then assume the responsibility to warn the patient.

The courts recognize exceptions, though, and have required manufacturers to warn patients directly about vaccines given in mass immunizations, drugs withdrawn from the market, drugs advertised directly to consumers, and other risks.

- BMJ Publishing Group. Clinical evidence. Summary of what is known—and not known—about more than 200 medical disorders and 2,000 treatments. www.clinicalevidence.com.

- Cochrane Library of evidence-based clinical reviews. www.cochrane.org.

- Agency for Health Care Research and Quality. Draft comparative effectiveness review of off-label use of atypical antipsychotic drugs. http://effectivehealthcare.ahrq.gov/synthesize/reports/draft.cfm.

- Amitriptyline • Elavil, others

- Carbamazepine • Carbetrol; Epitol; Equetro; Tegretol

- Gabapentin • Gabarone; Neurontin

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Trazodone • Desyrel; Trialodine

- Valproate • Depakote; Depakene