User login

The third generation of therapeutic innovation and the future of psychopharmacology

The field of psychiatric therapeutics is now experiencing its third generation of progress. No sooner had the pace of innovation in psychiatry and psychopharmacology hit the doldrums a few years ago, following the dwindling of the second generation of progress, than the current third generation of new drug development in psychopharmacology was born.

That is, the first generation of discovery of psychiatric medications in the 1960s and 1970s ushered in the first known psychotropic drugs, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, as well as major and minor tranquilizers, such as chlorpromazine and benzodiazepines, only to fizzle out in the 1980s. By the 1990s, the second generation of innovation in psychopharmacology was in full swing, with the “new” serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for depression, and the “atypical” antipsychotics for schizophrenia. However, soon after the turn of the century, pessimism for psychiatric therapeutics crept in again, and “big Pharma” abandoned their psychopharmacology programs in favor of other therapeutic areas. Surprisingly, the current “green shoots” of new ideas sprouting in our field today have not come from traditional big Pharma returning to psychiatry, but largely from small, innovative companies. These new entrepreneurial small pharmas and biotechs have found several new therapeutic targets. Furthermore, current innovation in psychopharmacology is increasingly following a paradigm shift away from DSM-5 disorders and instead to domains or symptoms of psychopathology that cut across numerous psychiatric conditions (transdiagnostic model).

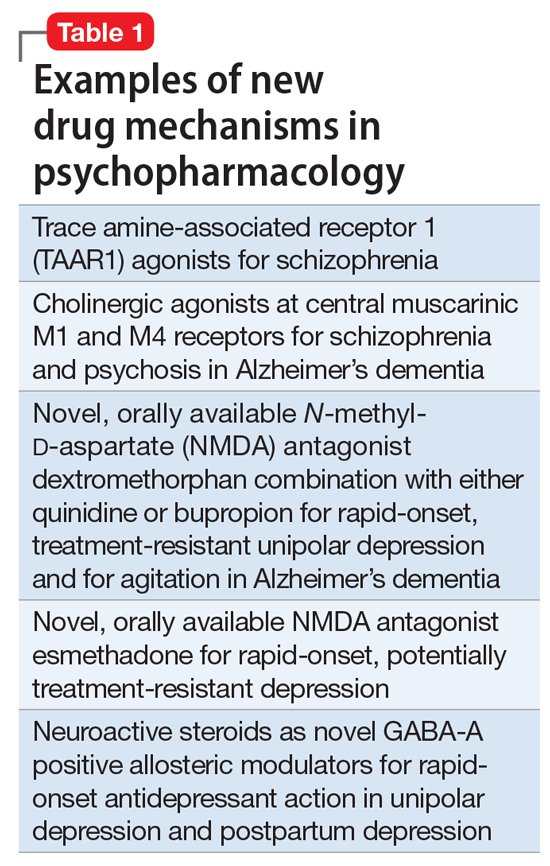

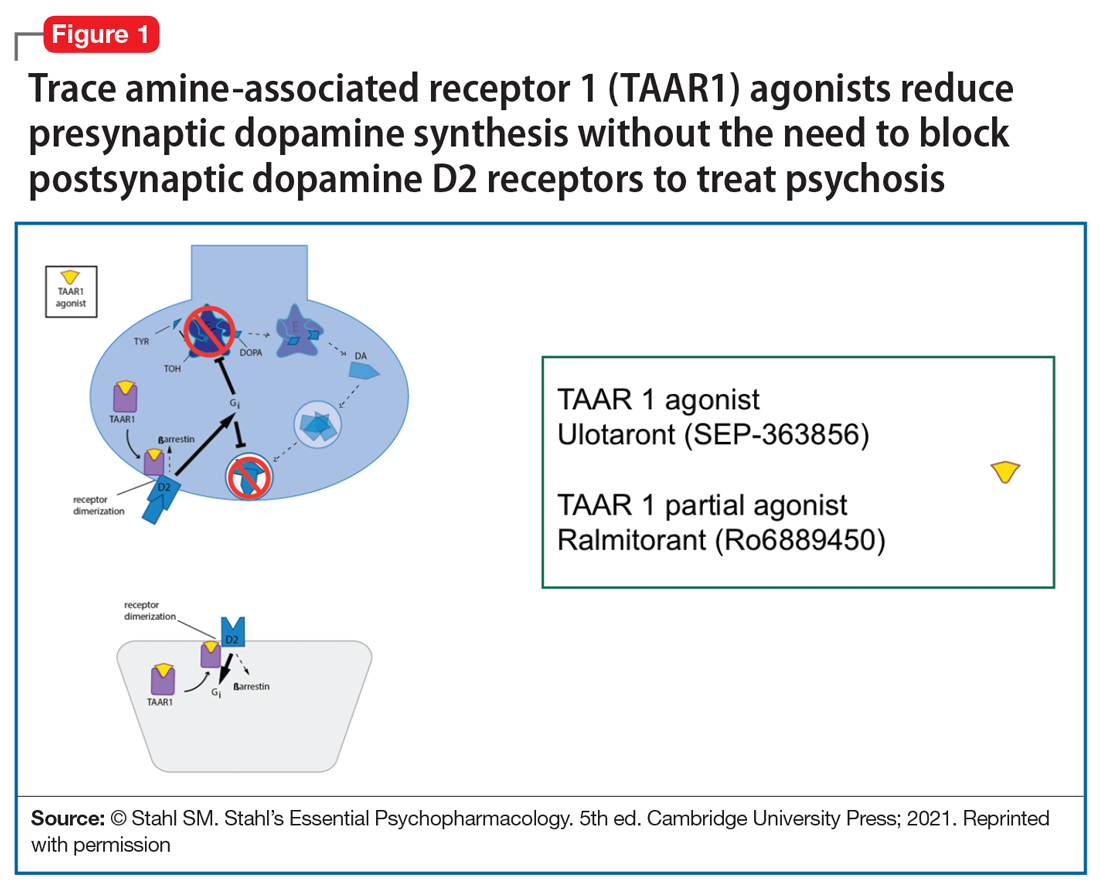

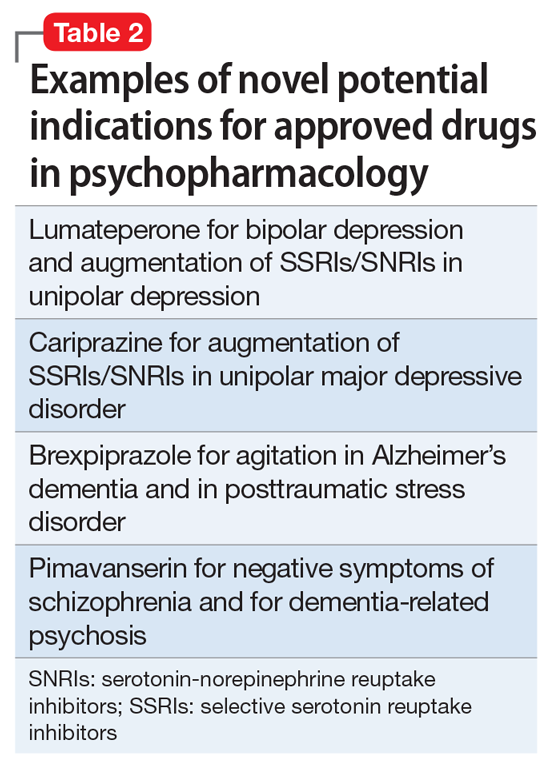

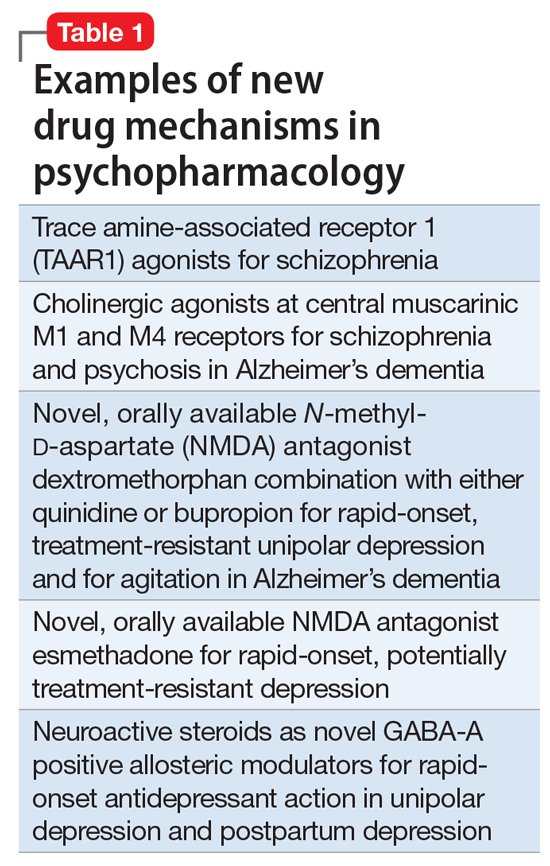

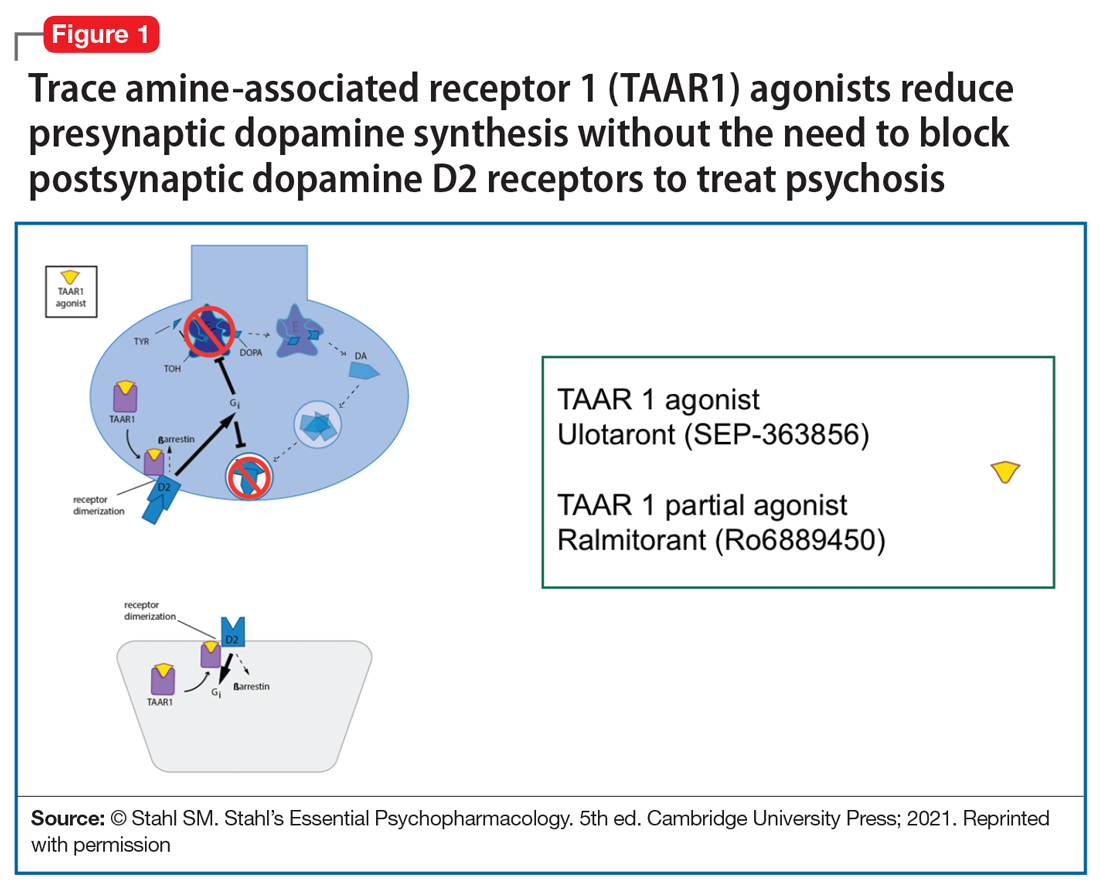

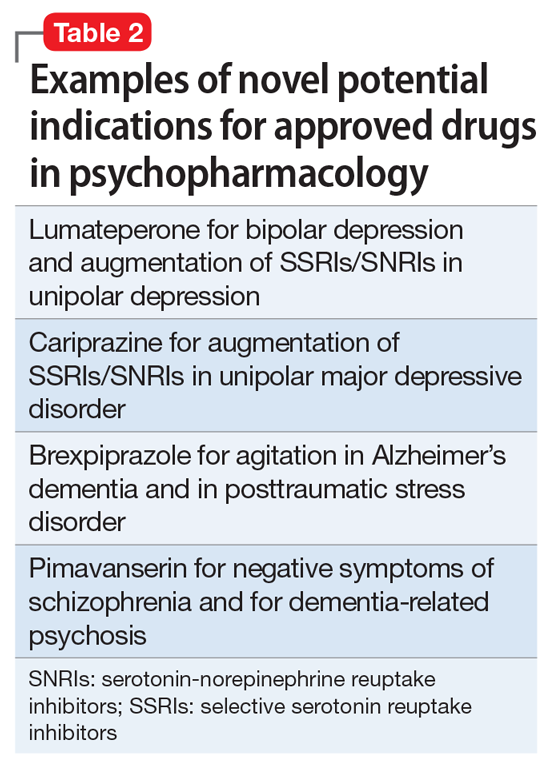

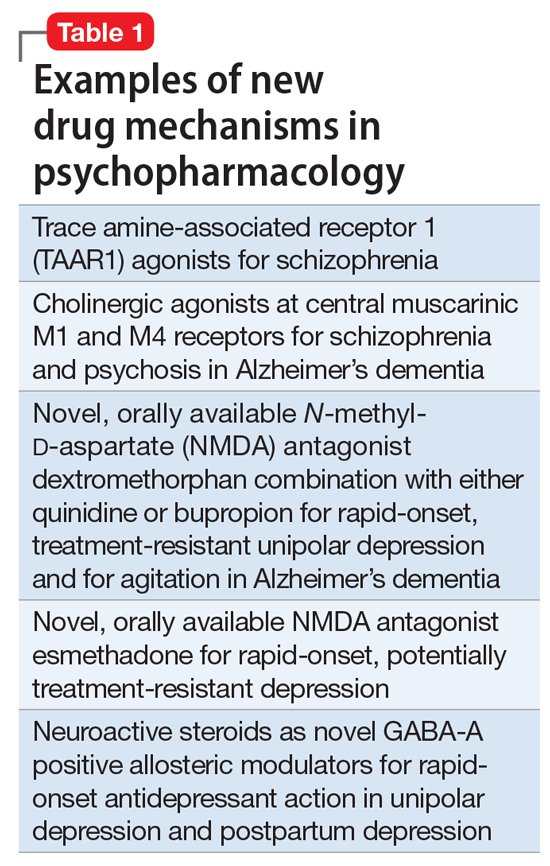

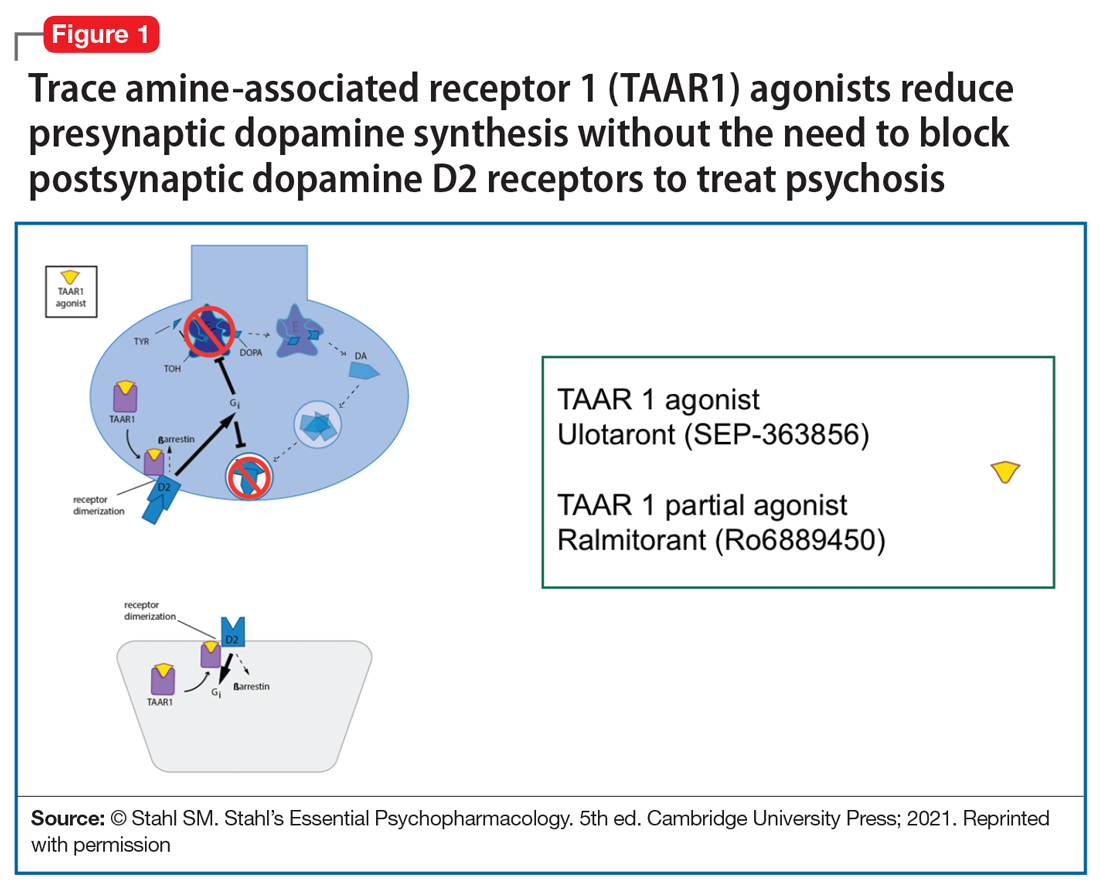

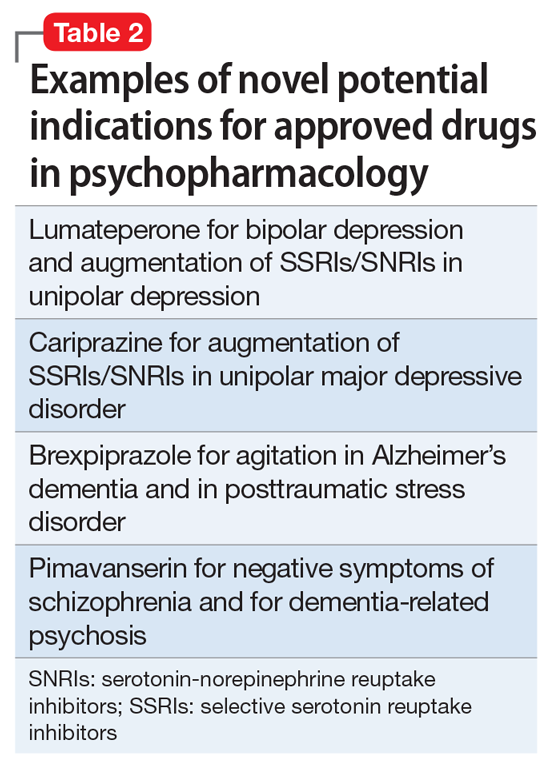

So, what are the new therapeutic mechanisms of this current third generation of innovation in psychopharmacology? Not all of these can be discussed here, but 2 examples of new approaches to psychosis deserve special mention because, for the first time in 70 years, they turn away from blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors to treat psychosis and instead stimulate receptors in other neurotransmitter systems that are linked to dopamine neurons in a network “upstream.” That is, trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) agonists target the pre-synaptic dopamine neuron, where dopamine synthesis and release are too high in psychosis, and cause dopamine synthesis to be reduced so that blockade of postsynaptic dopamine receptors is no longer necessary (Table 1 and Figure 1).1 Similarly, muscarinic cholinergic 1 and 4 receptor agonists target excitatory cholinergic neurons upstream, and turn down their stimulation of dopamine neurons, thereby reducing dopamine release so that postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors is also not necessary to treat psychosis with this mechanism (Table 1 and Figure 2).1 A similar mechanism of reducing upstream stimulation of dopamine release by serotonin has led to demonstration of antipsychotic actions of blocking this stimulation at serotonin 2A receptors (Table 2), and multiple approaches to enhancing deficient glutamate actions upstream are also under investigation for the treatment of psychosis. 1

Another major area of innovation in psychopharmacology worthy of emphasis is the rapid induction of neurogenesis that is associated with rapid reduction in the symptoms of depression, even when many conventional treatments have failed. Blockade of N-methyl-

that may hypothetically drive rapid recovery from depression.1 Proof of this concept was first shown with intravenous ketamine, and then intranasal esketamine, and now the oral NMDA antagonists dextromethorphan (combined with either bupropion or quinidine) and esmethadone (Table 1).1 Interestingly, this same mechanism may lead to a novel treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia as well.1

Continue to: Yet another mechanism...

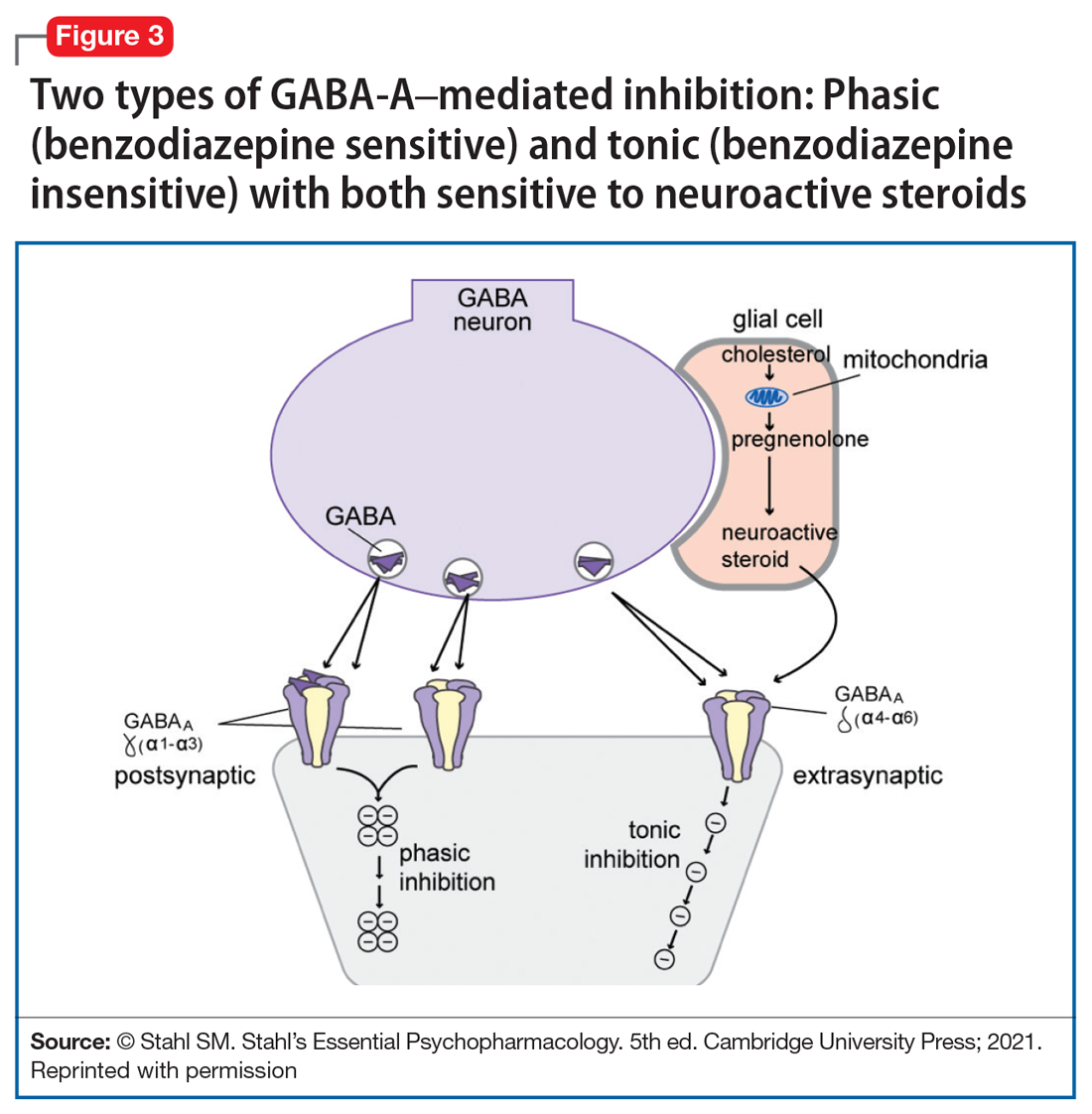

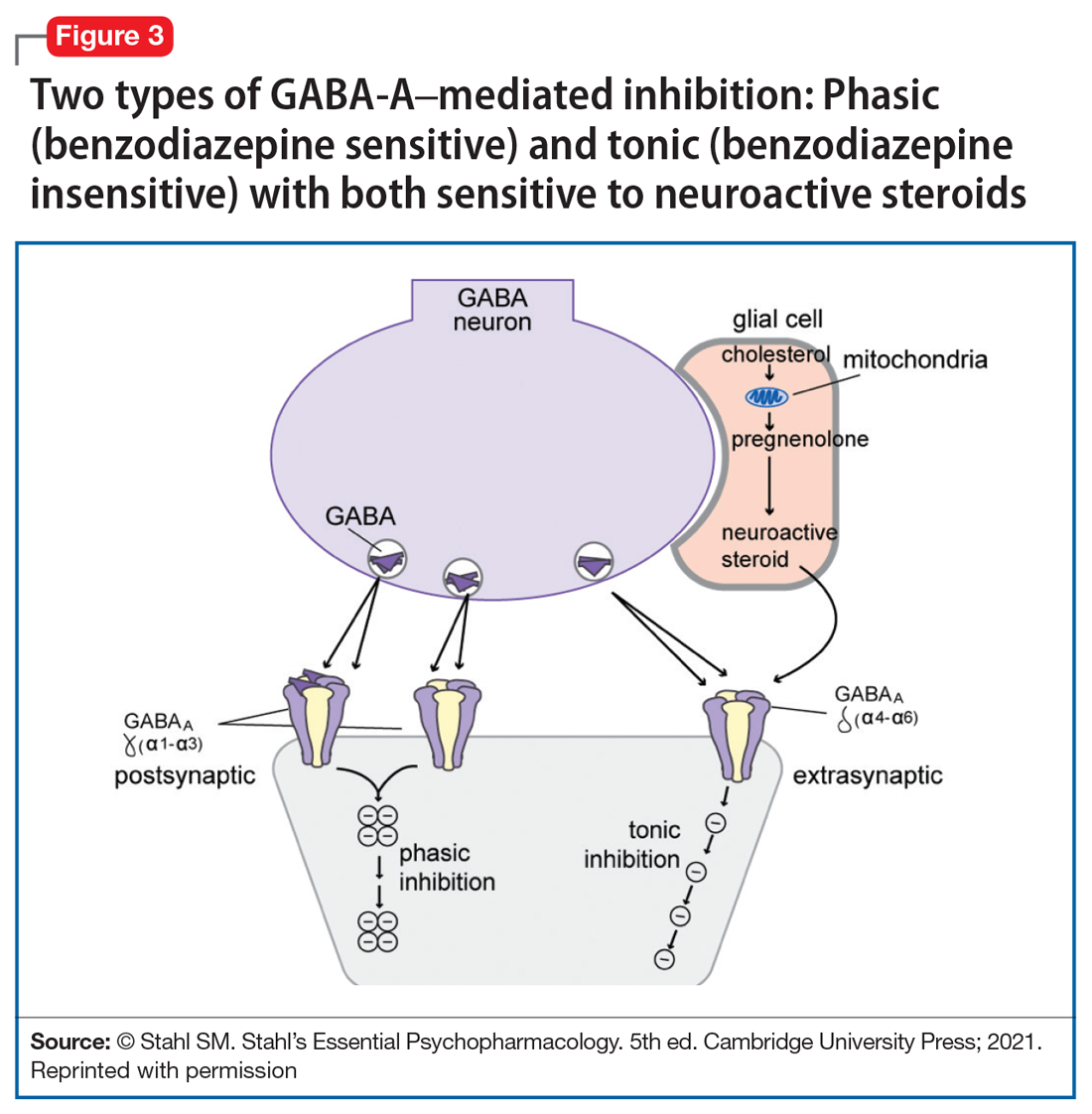

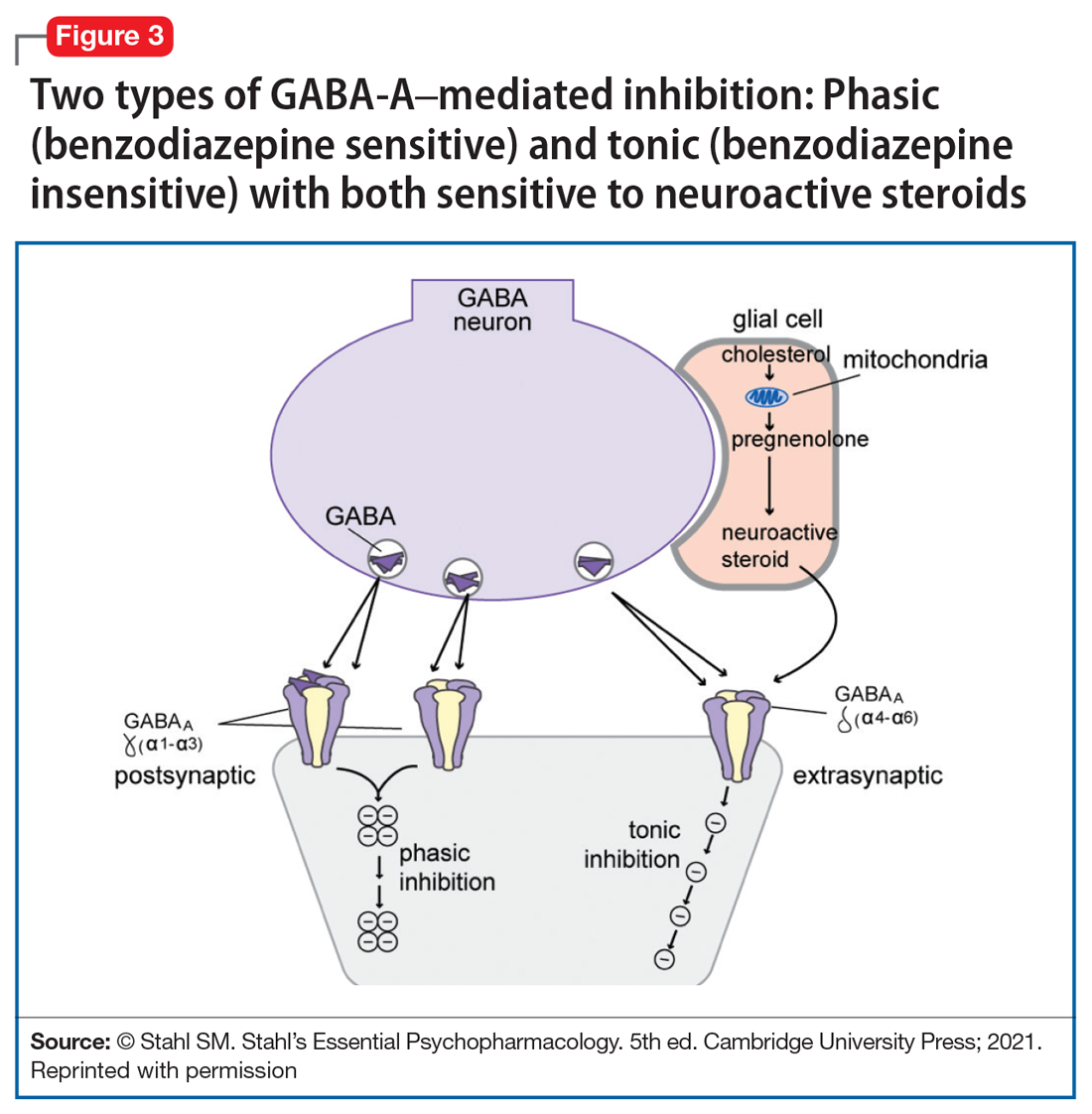

Yet another mechanism of potentially rapid onset antidepressant action is that of the novel agents known as neuroactive steroids that have a novel action at gamma aminobutyric acid A (GABA-A) receptors that are not sensitive to benzodiazepines (as well as those that are) (Table 1 and Figure 3).1 Finally, psychedelic drugs that target serotonin receptors such as psilocybin and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) seem to also have rapid onset of both neurogenesis and antidepressant action.

The future of psychopharmacology is clearly going to be amazing.

1. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

The field of psychiatric therapeutics is now experiencing its third generation of progress. No sooner had the pace of innovation in psychiatry and psychopharmacology hit the doldrums a few years ago, following the dwindling of the second generation of progress, than the current third generation of new drug development in psychopharmacology was born.

That is, the first generation of discovery of psychiatric medications in the 1960s and 1970s ushered in the first known psychotropic drugs, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, as well as major and minor tranquilizers, such as chlorpromazine and benzodiazepines, only to fizzle out in the 1980s. By the 1990s, the second generation of innovation in psychopharmacology was in full swing, with the “new” serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for depression, and the “atypical” antipsychotics for schizophrenia. However, soon after the turn of the century, pessimism for psychiatric therapeutics crept in again, and “big Pharma” abandoned their psychopharmacology programs in favor of other therapeutic areas. Surprisingly, the current “green shoots” of new ideas sprouting in our field today have not come from traditional big Pharma returning to psychiatry, but largely from small, innovative companies. These new entrepreneurial small pharmas and biotechs have found several new therapeutic targets. Furthermore, current innovation in psychopharmacology is increasingly following a paradigm shift away from DSM-5 disorders and instead to domains or symptoms of psychopathology that cut across numerous psychiatric conditions (transdiagnostic model).

So, what are the new therapeutic mechanisms of this current third generation of innovation in psychopharmacology? Not all of these can be discussed here, but 2 examples of new approaches to psychosis deserve special mention because, for the first time in 70 years, they turn away from blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors to treat psychosis and instead stimulate receptors in other neurotransmitter systems that are linked to dopamine neurons in a network “upstream.” That is, trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) agonists target the pre-synaptic dopamine neuron, where dopamine synthesis and release are too high in psychosis, and cause dopamine synthesis to be reduced so that blockade of postsynaptic dopamine receptors is no longer necessary (Table 1 and Figure 1).1 Similarly, muscarinic cholinergic 1 and 4 receptor agonists target excitatory cholinergic neurons upstream, and turn down their stimulation of dopamine neurons, thereby reducing dopamine release so that postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors is also not necessary to treat psychosis with this mechanism (Table 1 and Figure 2).1 A similar mechanism of reducing upstream stimulation of dopamine release by serotonin has led to demonstration of antipsychotic actions of blocking this stimulation at serotonin 2A receptors (Table 2), and multiple approaches to enhancing deficient glutamate actions upstream are also under investigation for the treatment of psychosis. 1

Another major area of innovation in psychopharmacology worthy of emphasis is the rapid induction of neurogenesis that is associated with rapid reduction in the symptoms of depression, even when many conventional treatments have failed. Blockade of N-methyl-

that may hypothetically drive rapid recovery from depression.1 Proof of this concept was first shown with intravenous ketamine, and then intranasal esketamine, and now the oral NMDA antagonists dextromethorphan (combined with either bupropion or quinidine) and esmethadone (Table 1).1 Interestingly, this same mechanism may lead to a novel treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia as well.1

Continue to: Yet another mechanism...

Yet another mechanism of potentially rapid onset antidepressant action is that of the novel agents known as neuroactive steroids that have a novel action at gamma aminobutyric acid A (GABA-A) receptors that are not sensitive to benzodiazepines (as well as those that are) (Table 1 and Figure 3).1 Finally, psychedelic drugs that target serotonin receptors such as psilocybin and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) seem to also have rapid onset of both neurogenesis and antidepressant action.

The future of psychopharmacology is clearly going to be amazing.

The field of psychiatric therapeutics is now experiencing its third generation of progress. No sooner had the pace of innovation in psychiatry and psychopharmacology hit the doldrums a few years ago, following the dwindling of the second generation of progress, than the current third generation of new drug development in psychopharmacology was born.

That is, the first generation of discovery of psychiatric medications in the 1960s and 1970s ushered in the first known psychotropic drugs, such as the tricyclic antidepressants, as well as major and minor tranquilizers, such as chlorpromazine and benzodiazepines, only to fizzle out in the 1980s. By the 1990s, the second generation of innovation in psychopharmacology was in full swing, with the “new” serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors for depression, and the “atypical” antipsychotics for schizophrenia. However, soon after the turn of the century, pessimism for psychiatric therapeutics crept in again, and “big Pharma” abandoned their psychopharmacology programs in favor of other therapeutic areas. Surprisingly, the current “green shoots” of new ideas sprouting in our field today have not come from traditional big Pharma returning to psychiatry, but largely from small, innovative companies. These new entrepreneurial small pharmas and biotechs have found several new therapeutic targets. Furthermore, current innovation in psychopharmacology is increasingly following a paradigm shift away from DSM-5 disorders and instead to domains or symptoms of psychopathology that cut across numerous psychiatric conditions (transdiagnostic model).

So, what are the new therapeutic mechanisms of this current third generation of innovation in psychopharmacology? Not all of these can be discussed here, but 2 examples of new approaches to psychosis deserve special mention because, for the first time in 70 years, they turn away from blocking postsynaptic dopamine D2 receptors to treat psychosis and instead stimulate receptors in other neurotransmitter systems that are linked to dopamine neurons in a network “upstream.” That is, trace amine-associated receptor 1 (TAAR1) agonists target the pre-synaptic dopamine neuron, where dopamine synthesis and release are too high in psychosis, and cause dopamine synthesis to be reduced so that blockade of postsynaptic dopamine receptors is no longer necessary (Table 1 and Figure 1).1 Similarly, muscarinic cholinergic 1 and 4 receptor agonists target excitatory cholinergic neurons upstream, and turn down their stimulation of dopamine neurons, thereby reducing dopamine release so that postsynaptic blockade of dopamine receptors is also not necessary to treat psychosis with this mechanism (Table 1 and Figure 2).1 A similar mechanism of reducing upstream stimulation of dopamine release by serotonin has led to demonstration of antipsychotic actions of blocking this stimulation at serotonin 2A receptors (Table 2), and multiple approaches to enhancing deficient glutamate actions upstream are also under investigation for the treatment of psychosis. 1

Another major area of innovation in psychopharmacology worthy of emphasis is the rapid induction of neurogenesis that is associated with rapid reduction in the symptoms of depression, even when many conventional treatments have failed. Blockade of N-methyl-

that may hypothetically drive rapid recovery from depression.1 Proof of this concept was first shown with intravenous ketamine, and then intranasal esketamine, and now the oral NMDA antagonists dextromethorphan (combined with either bupropion or quinidine) and esmethadone (Table 1).1 Interestingly, this same mechanism may lead to a novel treatment of agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia as well.1

Continue to: Yet another mechanism...

Yet another mechanism of potentially rapid onset antidepressant action is that of the novel agents known as neuroactive steroids that have a novel action at gamma aminobutyric acid A (GABA-A) receptors that are not sensitive to benzodiazepines (as well as those that are) (Table 1 and Figure 3).1 Finally, psychedelic drugs that target serotonin receptors such as psilocybin and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, “ecstasy”) seem to also have rapid onset of both neurogenesis and antidepressant action.

The future of psychopharmacology is clearly going to be amazing.

1. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

1. Stahl SM. Stahl’s Essential Psychopharmacology. 5th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2021.

Neuroscience-based Nomenclature: Classifying psychotropics by mechanism of action rather than indication

An important new initiative to reclassify psychiatric medications is underway. Currently, psychotropic drugs are named primarily for their clinical use, usually as a member of 1 of 6 classes: antipsychotic, anti‑depressant, mood stabilizer, stimulant, anxiolytic, and hypnotic.1,2

This naming system creates confusion because so-called antidepressants commonly are used as anxiolytics, antipsychotics increasingly are used as antidepressants, and so on.1,2

Vocabulary based on clinical indications also leads to difficulty in classifying new agents, especially those with novel mechanisms of action or clinical uses. Therefore, there is a need to make the names of psychotropic drugs more rational and scientifically based, rather than indication-based. A task force of experts from major psychopharmacology societies around the world is developing an alternative naming system that is increasingly being accepted by the major experts and journals throughout the world, called Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN).3-5

So, what is NbN?

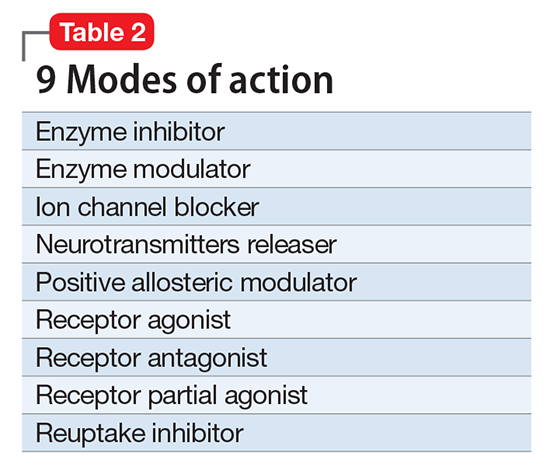

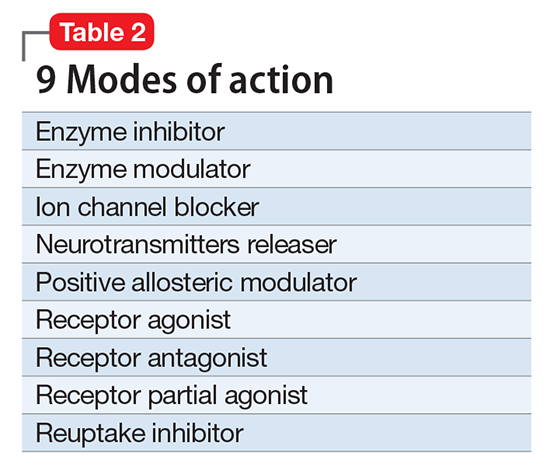

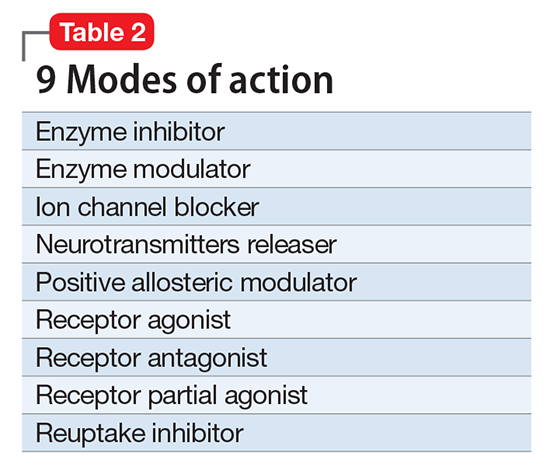

First and foremost, NbN renames the >100 known psychotropic drugs by 1 of the 11 principle pharmacological domains that include well-known terms such as serotonin dopamine, acetylcholine, and GABA (Table 1). Also included in NbN are 9 familiar modes of action, such as agonist, antagonist, reuptake inhibitor, and enzyme inhibitors (Table 2).3-5

NbN has 4 additional dimensions or layers3-5:

- The first layer enumerates the official indications as recognized by the regulatory agencies (ie, the FDA and other government organizations).

- The second layer states efficacy based on randomized controlled trials or substantial, evidence-based clinical data, as well as side effects (not the exhaustive list provided in manufacturers’ package inserts, but only the most common ones).

- The third layer is comprised of practical notes, highlighting potentially important drug interactions, metabolic issues, and specific warnings.

- The fourth section summarizes the neurobiological effects in laboratory animals and humans.

Specific dosages and titration regimens are not provided because they can vary among different countries, and NbN is intended for nomenclature and classification, not as a prescribing guide.

How does it work in practice?

Major journals in the field have begun adapting NbN for their published papers and

What is the current status?

Two international organizations endorse NbN, and the chief editors of nearly 3 dozen scientific journals, including

Clinicians should start adopting the NbN for the psychotropic drugs they prescribe every day. It is more scientific and consistent with the mechanism of action than with a specific disorder because many psychotropic medications have been found to be useful in >1 psychiatric disorder.

1. Nutt DJ. Beyond psychoanaleptics - can we improve antidepressant drug nomenclature? J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(4):343-345.

2. Stahl SM. Classifying psychotropic drugs by mode of action not by target disorders. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(3):113-117.

3. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. A review of the current nomenclature for psychotropic agents and an introduction to the Neuroscience-based Nomenclature. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015; 25(12):2318-2325.

4. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. Neuroscience based nomenclature. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2014:254.

5. Neuroscience-based nomenclature. http://nbnomenclature.org. Accessed April 12, 2017.

An important new initiative to reclassify psychiatric medications is underway. Currently, psychotropic drugs are named primarily for their clinical use, usually as a member of 1 of 6 classes: antipsychotic, anti‑depressant, mood stabilizer, stimulant, anxiolytic, and hypnotic.1,2

This naming system creates confusion because so-called antidepressants commonly are used as anxiolytics, antipsychotics increasingly are used as antidepressants, and so on.1,2

Vocabulary based on clinical indications also leads to difficulty in classifying new agents, especially those with novel mechanisms of action or clinical uses. Therefore, there is a need to make the names of psychotropic drugs more rational and scientifically based, rather than indication-based. A task force of experts from major psychopharmacology societies around the world is developing an alternative naming system that is increasingly being accepted by the major experts and journals throughout the world, called Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN).3-5

So, what is NbN?

First and foremost, NbN renames the >100 known psychotropic drugs by 1 of the 11 principle pharmacological domains that include well-known terms such as serotonin dopamine, acetylcholine, and GABA (Table 1). Also included in NbN are 9 familiar modes of action, such as agonist, antagonist, reuptake inhibitor, and enzyme inhibitors (Table 2).3-5

NbN has 4 additional dimensions or layers3-5:

- The first layer enumerates the official indications as recognized by the regulatory agencies (ie, the FDA and other government organizations).

- The second layer states efficacy based on randomized controlled trials or substantial, evidence-based clinical data, as well as side effects (not the exhaustive list provided in manufacturers’ package inserts, but only the most common ones).

- The third layer is comprised of practical notes, highlighting potentially important drug interactions, metabolic issues, and specific warnings.

- The fourth section summarizes the neurobiological effects in laboratory animals and humans.

Specific dosages and titration regimens are not provided because they can vary among different countries, and NbN is intended for nomenclature and classification, not as a prescribing guide.

How does it work in practice?

Major journals in the field have begun adapting NbN for their published papers and

What is the current status?

Two international organizations endorse NbN, and the chief editors of nearly 3 dozen scientific journals, including

Clinicians should start adopting the NbN for the psychotropic drugs they prescribe every day. It is more scientific and consistent with the mechanism of action than with a specific disorder because many psychotropic medications have been found to be useful in >1 psychiatric disorder.

An important new initiative to reclassify psychiatric medications is underway. Currently, psychotropic drugs are named primarily for their clinical use, usually as a member of 1 of 6 classes: antipsychotic, anti‑depressant, mood stabilizer, stimulant, anxiolytic, and hypnotic.1,2

This naming system creates confusion because so-called antidepressants commonly are used as anxiolytics, antipsychotics increasingly are used as antidepressants, and so on.1,2

Vocabulary based on clinical indications also leads to difficulty in classifying new agents, especially those with novel mechanisms of action or clinical uses. Therefore, there is a need to make the names of psychotropic drugs more rational and scientifically based, rather than indication-based. A task force of experts from major psychopharmacology societies around the world is developing an alternative naming system that is increasingly being accepted by the major experts and journals throughout the world, called Neuroscience-based Nomenclature (NbN).3-5

So, what is NbN?

First and foremost, NbN renames the >100 known psychotropic drugs by 1 of the 11 principle pharmacological domains that include well-known terms such as serotonin dopamine, acetylcholine, and GABA (Table 1). Also included in NbN are 9 familiar modes of action, such as agonist, antagonist, reuptake inhibitor, and enzyme inhibitors (Table 2).3-5

NbN has 4 additional dimensions or layers3-5:

- The first layer enumerates the official indications as recognized by the regulatory agencies (ie, the FDA and other government organizations).

- The second layer states efficacy based on randomized controlled trials or substantial, evidence-based clinical data, as well as side effects (not the exhaustive list provided in manufacturers’ package inserts, but only the most common ones).

- The third layer is comprised of practical notes, highlighting potentially important drug interactions, metabolic issues, and specific warnings.

- The fourth section summarizes the neurobiological effects in laboratory animals and humans.

Specific dosages and titration regimens are not provided because they can vary among different countries, and NbN is intended for nomenclature and classification, not as a prescribing guide.

How does it work in practice?

Major journals in the field have begun adapting NbN for their published papers and

What is the current status?

Two international organizations endorse NbN, and the chief editors of nearly 3 dozen scientific journals, including

Clinicians should start adopting the NbN for the psychotropic drugs they prescribe every day. It is more scientific and consistent with the mechanism of action than with a specific disorder because many psychotropic medications have been found to be useful in >1 psychiatric disorder.

1. Nutt DJ. Beyond psychoanaleptics - can we improve antidepressant drug nomenclature? J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(4):343-345.

2. Stahl SM. Classifying psychotropic drugs by mode of action not by target disorders. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(3):113-117.

3. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. A review of the current nomenclature for psychotropic agents and an introduction to the Neuroscience-based Nomenclature. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015; 25(12):2318-2325.

4. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. Neuroscience based nomenclature. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2014:254.

5. Neuroscience-based nomenclature. http://nbnomenclature.org. Accessed April 12, 2017.

1. Nutt DJ. Beyond psychoanaleptics - can we improve antidepressant drug nomenclature? J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(4):343-345.

2. Stahl SM. Classifying psychotropic drugs by mode of action not by target disorders. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(3):113-117.

3. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. A review of the current nomenclature for psychotropic agents and an introduction to the Neuroscience-based Nomenclature. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015; 25(12):2318-2325.

4. Zohar J, Stahl S, Moller HJ, et al. Neuroscience based nomenclature. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2014:254.

5. Neuroscience-based nomenclature. http://nbnomenclature.org. Accessed April 12, 2017.