User login

Reply to “In Reference to 'Improving the Safety of Opioid Use for Acute Noncancer Pain in Hospitalized Adults: A Consensus Statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine'”

Hall et al. draw attention to the important question of whether some patients may benefit from a naloxone prescription when discharged from the hospital with a short-term opioid prescription for acute pain. Although all members of the working group agreed that naloxone is appropriate in some cases, we were hesitant to recommend this as a standard practice for several reasons.

First, the intent of our Consensus Statement1 was to synthesize and summarize the areas of consensus in existing guidelines; none of the existing guidelines included in our systematic review make a recommendation for naloxone prescription in the setting of short-term opioid use for acute pain.2 We believe that this may relate to the fact that the risk factors for overdose and the threshold of risk above which naloxone would be beneficial have yet to be defined for this population and are likely to differ from those defined in patients using opioids chronically.

Additionally, if practitioners follow the recommendations to limit prescribing for acute pain to the minimum dose and duration of an opioid that was presumably administered in the hospital with an observed response, then the risk of overdose and the potential benefit of naloxone will decrease. Furthermore, emerging data from randomized controlled trials demonstrating noninferiority of nonopioid analgesics in the management of acute pain suggest that we should not so readily presume opioids to be the necessary or the best option.3-5 Data questioning the benefits of opioids over other safer therapies have particularly important implications for patients in whom the risks are felt to be high enough to warrant consideration of naloxone.

Disclosures

Dr. Herzig reports receiving compensation from the Society of Hospital Medicine for her editorial role in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (unrelated to the present work). None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Herzig is funded by a grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mosher is supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and the Office of Research and Development and Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation Center (CIN 13-412). The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. Herzig SJ, Calcaterra SL, Mosher HJ, et al. Safe opioid prescribing for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a systematic review of existing guidelines.. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):256-262. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2979. PubMed

3. Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661-1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16190. PubMed

4. Graudins A, Meek R, Parkinson J, Egerton-Warburton D, Meyer A. A randomised controlled trial of paracetamol and ibuprofen with or without codeine or oxycodone as initial analgesia for adults with moderate pain from limb injury. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(6):666-672. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12672 PubMed

5. Holdgate A, Pollock T. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004137.pub3 PubMed

Hall et al. draw attention to the important question of whether some patients may benefit from a naloxone prescription when discharged from the hospital with a short-term opioid prescription for acute pain. Although all members of the working group agreed that naloxone is appropriate in some cases, we were hesitant to recommend this as a standard practice for several reasons.

First, the intent of our Consensus Statement1 was to synthesize and summarize the areas of consensus in existing guidelines; none of the existing guidelines included in our systematic review make a recommendation for naloxone prescription in the setting of short-term opioid use for acute pain.2 We believe that this may relate to the fact that the risk factors for overdose and the threshold of risk above which naloxone would be beneficial have yet to be defined for this population and are likely to differ from those defined in patients using opioids chronically.

Additionally, if practitioners follow the recommendations to limit prescribing for acute pain to the minimum dose and duration of an opioid that was presumably administered in the hospital with an observed response, then the risk of overdose and the potential benefit of naloxone will decrease. Furthermore, emerging data from randomized controlled trials demonstrating noninferiority of nonopioid analgesics in the management of acute pain suggest that we should not so readily presume opioids to be the necessary or the best option.3-5 Data questioning the benefits of opioids over other safer therapies have particularly important implications for patients in whom the risks are felt to be high enough to warrant consideration of naloxone.

Disclosures

Dr. Herzig reports receiving compensation from the Society of Hospital Medicine for her editorial role in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (unrelated to the present work). None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Herzig is funded by a grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mosher is supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and the Office of Research and Development and Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation Center (CIN 13-412). The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

Hall et al. draw attention to the important question of whether some patients may benefit from a naloxone prescription when discharged from the hospital with a short-term opioid prescription for acute pain. Although all members of the working group agreed that naloxone is appropriate in some cases, we were hesitant to recommend this as a standard practice for several reasons.

First, the intent of our Consensus Statement1 was to synthesize and summarize the areas of consensus in existing guidelines; none of the existing guidelines included in our systematic review make a recommendation for naloxone prescription in the setting of short-term opioid use for acute pain.2 We believe that this may relate to the fact that the risk factors for overdose and the threshold of risk above which naloxone would be beneficial have yet to be defined for this population and are likely to differ from those defined in patients using opioids chronically.

Additionally, if practitioners follow the recommendations to limit prescribing for acute pain to the minimum dose and duration of an opioid that was presumably administered in the hospital with an observed response, then the risk of overdose and the potential benefit of naloxone will decrease. Furthermore, emerging data from randomized controlled trials demonstrating noninferiority of nonopioid analgesics in the management of acute pain suggest that we should not so readily presume opioids to be the necessary or the best option.3-5 Data questioning the benefits of opioids over other safer therapies have particularly important implications for patients in whom the risks are felt to be high enough to warrant consideration of naloxone.

Disclosures

Dr. Herzig reports receiving compensation from the Society of Hospital Medicine for her editorial role in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (unrelated to the present work). None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Herzig is funded by a grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mosher is supported in part by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and the Office of Research and Development and Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation Center (CIN 13-412). The views expressed in this manuscript do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. Herzig SJ, Calcaterra SL, Mosher HJ, et al. Safe opioid prescribing for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a systematic review of existing guidelines.. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):256-262. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2979. PubMed

3. Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661-1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16190. PubMed

4. Graudins A, Meek R, Parkinson J, Egerton-Warburton D, Meyer A. A randomised controlled trial of paracetamol and ibuprofen with or without codeine or oxycodone as initial analgesia for adults with moderate pain from limb injury. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(6):666-672. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12672 PubMed

5. Holdgate A, Pollock T. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004137.pub3 PubMed

1. Herzig SJ, Mosher HJ, Calcaterra SL, Jena AB, Nuckols TK. Improving the safety of opioid use for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a consensus statement from the Society of Hospital Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):263-271. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2980. PubMed

2. Herzig SJ, Calcaterra SL, Mosher HJ, et al. Safe opioid prescribing for acute noncancer pain in hospitalized adults: a systematic review of existing guidelines.. J Hosp Med. 2018;13(4):256-262. doi: 10.12788/jhm.2979. PubMed

3. Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a single dose of oral opioid and nonopioid analgesics on acute extremity pain in the emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661-1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.16190. PubMed

4. Graudins A, Meek R, Parkinson J, Egerton-Warburton D, Meyer A. A randomised controlled trial of paracetamol and ibuprofen with or without codeine or oxycodone as initial analgesia for adults with moderate pain from limb injury. Emerg Med Australas. 2016;28(6):666-672. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12672 PubMed

5. Holdgate A, Pollock T. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) versus opioids for acute renal colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005:CD004137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004137.pub3 PubMed

Safe Opioid Prescribing for Acute Noncancer Pain in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review of Existing Guidelines

Pain is prevalent among hospitalized patients, occurring in 52%-71% of patients in cross-sectional surveys.1-3 Opioid administration is also common, with more than half of nonsurgical patients in United States (US) hospitals receiving at least one dose of opioid during hospitalization.4 Studies have also begun to define the degree to which hospital prescribing contributes to long-term use. Among opioid-naïve patients admitted to the hospital, 15%-25% fill an opioid prescription in the week after hospital discharge,5,6 43% of such patients fill another opioid prescription 90 days postdischarge,6 and 15% meet the criteria for long-term use at one year.7 With about 37 million discharges from US hospitals each year,8 these estimates suggest that hospitalization contributes to initiation of long-term opioid use in millions of adults each year.

Additionally, studies in the emergency department and hospital settings demonstrate large variations in prescribing of opioids between providers and hospitals.4,9 Variation unrelated to patient characteristics highlights areas of clinical uncertainty and the corresponding need for prescribing standards and guidance. To our knowledge, there are no existing guidelines on safe prescribing of opioids in hospitalized patients, aside from guidelines specifically focused on the perioperative, palliative care, or end-of-life settings.

Thus, in the context of the current opioid epidemic, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) sought to develop a consensus statement to assist clinicians practicing medicine in the inpatient setting in safe prescribing of opioids for acute, noncancer pain on the medical services. We define “safe” prescribing as proposed by Aronson: “a process that recommends a medicine appropriate to the patient’s condition and minimizes the risk of undue harm from it.”10 To inform development of the consensus statement, SHM convened a working group to systematically review existing guidelines on the more general management of acute pain. This article describes the methods and results of our systematic review of existing guidelines for managing acute pain. The Consensus Statement derived from these existing guidelines, applied to the hospital setting, appears in a companion article.

METHODS

Steps in the systematic review process included: 1) searching for relevant guidelines, 2) applying exclusion criteria, 3) assessing the quality of the guidelines, and 4) synthesizing guideline recommendations to identify issues potentially relevant to medical inpatients with acute pain. Details of the protocol for this systematic review were registered on PROSPERO and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=71846.

Data Sources and Search Terms

Guideline Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We defined guidelines as statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harm of alternative care options, consistent with the National Academies’ definition.11 To be eligible, guidelines had to be published in English and include recommendations on prescribing opioids for acute, noncancer pain. We excluded guidelines focused on chronic pain or palliative care, guidelines derived entirely from another guideline, and guidelines published before 2010, since such guidelines may contain outdated information.12 Because we were interested in general principles regarding safe use of opioids for managing acute pain, we excluded guidelines that focused exclusively on specific disease processes (eg, cancer, low-back pain, and sickle cell anemia). As we were specifically interested in the management of acute pain in the hospital setting, we also excluded guidelines that focused exclusively on specific nonhospital settings of care (eg, outpatient care clinics and nursing homes). We included guidelines related to care in the emergency department (ED) given the hospital-based location of care and the high degree of similarity in scope of practice and patient population, as most hospitalized adults are admitted through the ED. Finally, we excluded guidelines focusing on management in the intensive care setting (including the post-anesthesia care unit) given the inherent differences in patient population and management options between the intensive and nonintensive care areas of the hospital.

Guideline Quality Assessment

Guideline Synthesis and Analysis

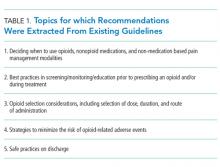

We extracted recommendations from each guideline related to the following topics: 1) deciding when to use opioids, nonopioid medications, and nonmedication-based pain management modalities, 2) best practices in screening/monitoring/education prior to prescribing an opioid and/or during treatment, 3) opioid selection considerations, including selection of dose, duration, and route of administration, 4) strategies to minimize the risk of opioid-related adverse events, and 5) safe practices on discharge.

Role of the Funding Source

The Society of Hospital Medicine provided administrative and material support for the project, but had no role in the design or execution of the scientific evaluation.

RESULTS

Guideline Quality Assessment

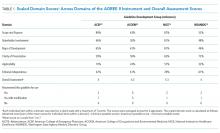

See Table 1 for the AGREE II scaled domain scores, and Appendix Table 1 for the ratings on each individual item within a domain. The range of scaled scores for each of the AGREE II domains were as follows: Scope and purpose 52%-89%, stakeholder involvement 30%-81%, rigor of development 46%-81%, clarity of presentation 59%-72%, applicability 10%-57%, and editorial independence 42%-78%. Overall guideline assessment scores ranged from 4 to 5.33 on a scale from 1 to 7. Three of the guidelines (NICE, ACOEM, and WSAMDG)16,17,19 were recommended for use without modification by 2 out of 3 guideline appraisers, and one of the guidelines (ACEP)18 was recommended for use with modification by all 3 appraisers. The guideline by NICE19 was rated the highest both overall (5.33), and on 4 of the 6 AGREE II domains.

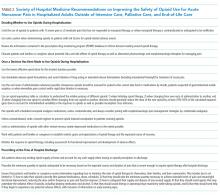

Although the guidelines each included a systematic review of the literature, the NICE19 and WSAMDG17 guidelines did not include the strength of recommendations or provide clear links between each recommendation and the underlying evidence base. When citations were present, we reviewed them to determine the type of data upon which the recommendations were based and included this information in Table 2. The majority of the recommendations in Table 2 are based on expert opinion alone, or other guidelines.

Guideline Synthesis and Analysis

Table 2 contains a synthesis of the recommendations related to each of our 5 prespecified content areas. Despite the generally low quality of the evidence supporting the recommendations, there were many areas of concordance across guidelines.

Deciding When to Use Opioids, Nonopioid Medications, and Nonmedication-Based Pain Management Modalities

Three out of 4 guidelines recommended restricting opioid use to severe pain or pain that has not responded to nonopioid therapy,16-18 2 guidelines recommended treating mild to moderate pain with nonopioid medications, including acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),16,17 and 2 guidelines recommended co-prescribing opioids with nonopioid analgesic medications to reduce total opioid requirements and improve pain control.16,17 Each of these recommendations was supported by at least one randomized controlled trial.

Best Practices in Screening/Monitoring/Education to Occur Prior to Prescribing an Opioid and/or During Treatment

Three guidelines recommended checking prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), all based on expert consensus.16-18 Only the WSAMDG guideline offered guidance as to the optimal timing to check the PDMP in this setting, specifically recommending to check before prescribing opioids.17 Two guidelines also recommended helping patients set reasonable expectations about their recovery and educating patients about the risks/side effects of opioid therapy, all based on expert consensus or other guidelines.17,19

Opioid Selection Considerations, Including Selection of Dose, Duration, and Route of Administration

Three guidelines recommended using the lowest effective dose, supported by expert consensus and observational data in the outpatient setting demonstrating that overdose risk increases with opioid dose.16-18 Three guidelines recommended using short-acting opioids and/or avoiding use of long-acting/extended-release opioids for acute pain based on expert consensus.16-18 Two guidelines recommended using as-needed rather than scheduled dosing of opioids based on expert recommendation.16, 17

Strategies to Minimize the Risk of Opioid-Related Adverse Events

Several strategies to minimize the risk of opioid-related adverse events were identified, but most were only recommended by a single guideline. Strategies recommended by more than one guideline included using a recognized opioid dose conversion guide when prescribing, reviewing, or changing opioid prescriptions (based on expert consensus);16,19 avoiding co-administration of parenteral and oral as-needed opioids, and if as-needed opioids from different routes are necessary, providing a clear indication for use of each (based on expert consensus and other guidelines);17,19 and avoiding/using caution when co-prescribing opioids with other central nervous system depressant medications16,17 (supported by observational studies demonstrating increased risk in the outpatient setting).

Safe Practices on Discharge

All 4 of the guidelines recommended prescribing a limited duration of opioids for the acute pain episode; however the maximum recommended duration varied widely from one week to 30 days.16-19 It is important to note that because these guidelines were not focused on hospitalization specifically, these maximum recommended durations of use reflect the entire acute pain episode (ie, not prescribing on discharge specifically). The guideline with the longest maximum recommended duration was from NICE, based in the United Kingdom, while the US-based guideline development groups uniformly recommended 1 to 2 weeks as the maximum duration of opioid use, including the period of hospitalization.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review identified only 4 existing guidelines that included recommendations on safe opioid prescribing practices for managing acute, noncancer pain, outside of the context of specific conditions, specific nonhospital settings, or the intensive care setting. Although 2 of the identified guidelines offered sparse recommendations specific to the hospital setting, we found no guidelines that focused exclusively on the period of hospitalization specifically outside of the perioperative period. Furthermore, the guideline recommendations were largely based on expert opinion. Although these factors limit the confidence with which the recommendations can be applied to the hospital setting, they nonetheless represent the best guidance currently available to standardize and improve the safety of prescribing opioids in the hospital setting.

This paucity of guidance specific to patients hospitalized in general, nonintensive care areas of the hospital is important because pain management in this setting differs in a number of ways from pain management in the ambulatory or intensive care unit settings (including the post-anesthesia care unit). First, there are differences in the monitoring strategies that are available in each of these settings (eg, variability in nurse-to-patient ratios, frequency of measuring vital signs, and availability of continuous pulse oximetry/capnography). Second, there are differences in available/feasible routes of medication administration depending on the setting of care. Finally, there are differences in the patients themselves, including severity of illness, baseline and expected functional status, pain severity, and ability to communicate.

Accordingly, to avoid substantial heterogeneity in recommendations obtained from this review, we chose to focus on guidelines most relevant to clinicians practicing medicine in nonintensive care areas of the hospital. This resulted in the exclusion of 2 guidelines intended for anesthesiologists that focused exclusively on perioperative management and included use of advanced management procedures beyond the scope of practice for general internists,20,21 and one guideline that focused on management in the intensive care unit.22 Within the set of guidelines included in this review, we did include recommendations designated for the postoperative period that we felt were relevant to the care of hospitalized patients more generally. In fact, the ACOEM guideline, which includes postoperative recommendations, specifically noted that these recommendations are mostly comparable to those for treating acute pain more generally.16

In addition to the lack of guidance specific to the setting in which most hospitalists practice, most of the recommendations in the existing guidelines are based on expert consensus. Guidelines based on expert opinion typically carry a lower strength of recommendation, and, accordingly, should be applied with some caution and accompanied by diligent tracking of outcome metrics, as these recommendations are applied to local health systems. Recommendations may have unintended consequences that are not necessarily apparent at the outset, and the specific circumstances of each patient must be considered when deciding how best to apply recommendations. Additional research will be necessary to track the impact of the recommended prescribing practices on patient outcomes, particularly given that many states have already begun instituting regulations on safe opioid prescribing despite the limited nature of the evidence. Furthermore, although several studies have identified patient- and prescribing-related risk factors for opioid-related adverse events in surgical patient populations, given the differences in patient characteristics and prescribing patterns in these settings, research to understand the risk factors in hospitalized medical patients specifically is important to inform evidence-based, safe prescribing recommendations in this setting.

Despite the largely expert consensus-based nature of the recommendations, we found substantial overlap in the recommendations between the guidelines, spanning our prespecified topics of interest related to safe prescribing. Most guidelines recommended restricting opioid use to severe pain or pain that has not responded to nonopioid therapy, checking PDMPs, using the lowest effective dose, and using short-acting opioids and/or avoiding use of long-acting/extended-release opioids for acute pain. There was less consensus on risk mitigation strategies, where the majority of recommendations were endorsed by only 1 or 2 guidelines. Finally, all 4 guidelines recommended prescribing a limited duration of opioids for the acute pain episode, with US-based guidelines recommending 1 to 2 weeks as the maximum duration of opioid use, including the period of hospitalization.

There are limitations to our evaluation. As previously noted, in order to avoid substantial heterogeneity in management recommendations, we excluded 2 guidelines intended for anesthesiologists that focused exclusively on perioperative management,20,21 and one guideline focused on management in the intensive care unit.22 Accordingly, recommendations contained in this review may or may not be applicable to those settings, and readers interested in those settings specifically are directed to those guidelines. Additionally, we decided to exclude guidelines that focused on managing acute pain in specific conditions (eg, sickle cell disease and pancreatitis) because our goal was to identify generalizable principles of safe prescribing of opioids that apply regardless of clinical condition. Despite this goal, it is important to recognize that not all of the recommendations are generalizable to all types of pain; clinicians interested in management principles specific to certain disease states are encouraged to review disease-specific informational material. Finally, although we used rigorous, pre-defined search criteria and registered our protocol on PROSPERO, it is possible that our search strategy missed relevant guidelines.

In conclusion, we identified few guidelines on safe opioid prescribing practices for managing acute, noncancer pain, outside of the context of specific conditions or nonhospital settings, and no guidelines focused on acute pain management in general, nonintensive care areas of the hospital specifically. Nevertheless, the guidelines that we identified make consistent recommendations related to our prespecified topic areas of relevance to the hospital setting, although most recommendations are based exclusively on expert opinion. Our systematic review nonetheless provides guidance in an area where guidance has thus far been limited. Future research should investigate risk factors for opioid-related adverse events in hospitalized, nonsurgical patients, and the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce their occurrence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Herzig had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Kevin Vuernick, Jenna Goldstein, Meghan Mallouk, and Chris Frost, MD, from SHM for their facilitation of this project and dedication to this purpose.

Disclosures: Dr. Herzig received compensation from the Society of Hospital Medicine for her editorial role at the Journal of Hospital Medicine (unrelated to the present work). Dr. Jena received consulting fees from Pfizer, Inc., Hill Rom Services, Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and Precision Health Economics (all unrelated to the present work). None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) provided administrative assistance and material support, but had no role in or influence on the scientific conduct of the study. Dr. Herzig was funded by grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mosher was supported, in part, by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and Office of Research and Development and Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation Center (CIN 13-412). None of the funding agencies had involvement in any aspect of the study, including design, conduct, or reporting of the study

1. Melotti RM, Samolsky-Dekel BG, Ricchi E, et al. Pain prevalence and predictors among inpatients in a major Italian teaching hospital. A baseline survey towards a pain free hospital. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(5):485-495. PubMed

2. Sawyer J, Haslam L, Robinson S, Daines P, Stilos K. Pain prevalence study in a large Canadian teaching hospital. Pain Manag Nurs. 2008;9(3):104-112. PubMed

3. Strohbuecker B, Mayer H, Evers GC, Sabatowski R. Pain prevalence in hospitalized patients in a German university teaching hospital. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(5):498-506. PubMed

4. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in US hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81. PubMed

5. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;31(5):478-485. PubMed

6. Jena AB, Goldman D, Karaca-Mandic P. Hospital prescribing of opioids to medicare neneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):990-997. PubMed

7. Mosher HJ, Hofmeyer B, Hadlandsmyth K, Richardson KK, Lund BC. Predictors of long-term opioid use after opioid initiation at discharge from medical and surgical hospitalizations. JHM. Accepted for Publication November 11, 2017. PubMed

8. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #180. 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2015. PubMed

9. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):663-673. PubMed

10. Aronson JK. Balanced prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(6):629-632. PubMed

11. IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

12. Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, et al. Validity of the agency for healthcare research and quality clinical practice guidelines: How quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA. 2001;286(12):1461-1467. PubMed

13. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-E842. PubMed

14. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 1: performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):1045-1052. PubMed

15. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):E472-E478. PubMed

16. Hegmann KT, Weiss MS, Bowden K, et al. ACOEM practice guidelines: opioids for treatment of acute, subacute, chronic, and postoperative pain. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(12):e143-e159. PubMed

17. Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group. Interagency Guideline on Prescribing Opioids for Pain. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/2015AMDGOpioidGuideline.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2017.

18. Cantrill SV, Brown MD, Carlisle RJ, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the prescribing of opioids for adult patients in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(4):499-525. PubMed

19. National Institute for Healthcare Excellence. Controlled drugs: Safe use and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng46/chapter/Recommendations. Accessed December 5, 2017.

20. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(2):248-273. PubMed

21. Apfelbaum JL, Silverstein JH, Chung FF, et al. Practice guidelines for postanesthetic care: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Postanesthetic Care. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):291-307. PubMed

22. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263-306. PubMed

Pain is prevalent among hospitalized patients, occurring in 52%-71% of patients in cross-sectional surveys.1-3 Opioid administration is also common, with more than half of nonsurgical patients in United States (US) hospitals receiving at least one dose of opioid during hospitalization.4 Studies have also begun to define the degree to which hospital prescribing contributes to long-term use. Among opioid-naïve patients admitted to the hospital, 15%-25% fill an opioid prescription in the week after hospital discharge,5,6 43% of such patients fill another opioid prescription 90 days postdischarge,6 and 15% meet the criteria for long-term use at one year.7 With about 37 million discharges from US hospitals each year,8 these estimates suggest that hospitalization contributes to initiation of long-term opioid use in millions of adults each year.

Additionally, studies in the emergency department and hospital settings demonstrate large variations in prescribing of opioids between providers and hospitals.4,9 Variation unrelated to patient characteristics highlights areas of clinical uncertainty and the corresponding need for prescribing standards and guidance. To our knowledge, there are no existing guidelines on safe prescribing of opioids in hospitalized patients, aside from guidelines specifically focused on the perioperative, palliative care, or end-of-life settings.

Thus, in the context of the current opioid epidemic, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) sought to develop a consensus statement to assist clinicians practicing medicine in the inpatient setting in safe prescribing of opioids for acute, noncancer pain on the medical services. We define “safe” prescribing as proposed by Aronson: “a process that recommends a medicine appropriate to the patient’s condition and minimizes the risk of undue harm from it.”10 To inform development of the consensus statement, SHM convened a working group to systematically review existing guidelines on the more general management of acute pain. This article describes the methods and results of our systematic review of existing guidelines for managing acute pain. The Consensus Statement derived from these existing guidelines, applied to the hospital setting, appears in a companion article.

METHODS

Steps in the systematic review process included: 1) searching for relevant guidelines, 2) applying exclusion criteria, 3) assessing the quality of the guidelines, and 4) synthesizing guideline recommendations to identify issues potentially relevant to medical inpatients with acute pain. Details of the protocol for this systematic review were registered on PROSPERO and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=71846.

Data Sources and Search Terms

Guideline Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We defined guidelines as statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harm of alternative care options, consistent with the National Academies’ definition.11 To be eligible, guidelines had to be published in English and include recommendations on prescribing opioids for acute, noncancer pain. We excluded guidelines focused on chronic pain or palliative care, guidelines derived entirely from another guideline, and guidelines published before 2010, since such guidelines may contain outdated information.12 Because we were interested in general principles regarding safe use of opioids for managing acute pain, we excluded guidelines that focused exclusively on specific disease processes (eg, cancer, low-back pain, and sickle cell anemia). As we were specifically interested in the management of acute pain in the hospital setting, we also excluded guidelines that focused exclusively on specific nonhospital settings of care (eg, outpatient care clinics and nursing homes). We included guidelines related to care in the emergency department (ED) given the hospital-based location of care and the high degree of similarity in scope of practice and patient population, as most hospitalized adults are admitted through the ED. Finally, we excluded guidelines focusing on management in the intensive care setting (including the post-anesthesia care unit) given the inherent differences in patient population and management options between the intensive and nonintensive care areas of the hospital.

Guideline Quality Assessment

Guideline Synthesis and Analysis

We extracted recommendations from each guideline related to the following topics: 1) deciding when to use opioids, nonopioid medications, and nonmedication-based pain management modalities, 2) best practices in screening/monitoring/education prior to prescribing an opioid and/or during treatment, 3) opioid selection considerations, including selection of dose, duration, and route of administration, 4) strategies to minimize the risk of opioid-related adverse events, and 5) safe practices on discharge.

Role of the Funding Source

The Society of Hospital Medicine provided administrative and material support for the project, but had no role in the design or execution of the scientific evaluation.

RESULTS

Guideline Quality Assessment

See Table 1 for the AGREE II scaled domain scores, and Appendix Table 1 for the ratings on each individual item within a domain. The range of scaled scores for each of the AGREE II domains were as follows: Scope and purpose 52%-89%, stakeholder involvement 30%-81%, rigor of development 46%-81%, clarity of presentation 59%-72%, applicability 10%-57%, and editorial independence 42%-78%. Overall guideline assessment scores ranged from 4 to 5.33 on a scale from 1 to 7. Three of the guidelines (NICE, ACOEM, and WSAMDG)16,17,19 were recommended for use without modification by 2 out of 3 guideline appraisers, and one of the guidelines (ACEP)18 was recommended for use with modification by all 3 appraisers. The guideline by NICE19 was rated the highest both overall (5.33), and on 4 of the 6 AGREE II domains.

Although the guidelines each included a systematic review of the literature, the NICE19 and WSAMDG17 guidelines did not include the strength of recommendations or provide clear links between each recommendation and the underlying evidence base. When citations were present, we reviewed them to determine the type of data upon which the recommendations were based and included this information in Table 2. The majority of the recommendations in Table 2 are based on expert opinion alone, or other guidelines.

Guideline Synthesis and Analysis

Table 2 contains a synthesis of the recommendations related to each of our 5 prespecified content areas. Despite the generally low quality of the evidence supporting the recommendations, there were many areas of concordance across guidelines.

Deciding When to Use Opioids, Nonopioid Medications, and Nonmedication-Based Pain Management Modalities

Three out of 4 guidelines recommended restricting opioid use to severe pain or pain that has not responded to nonopioid therapy,16-18 2 guidelines recommended treating mild to moderate pain with nonopioid medications, including acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),16,17 and 2 guidelines recommended co-prescribing opioids with nonopioid analgesic medications to reduce total opioid requirements and improve pain control.16,17 Each of these recommendations was supported by at least one randomized controlled trial.

Best Practices in Screening/Monitoring/Education to Occur Prior to Prescribing an Opioid and/or During Treatment

Three guidelines recommended checking prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), all based on expert consensus.16-18 Only the WSAMDG guideline offered guidance as to the optimal timing to check the PDMP in this setting, specifically recommending to check before prescribing opioids.17 Two guidelines also recommended helping patients set reasonable expectations about their recovery and educating patients about the risks/side effects of opioid therapy, all based on expert consensus or other guidelines.17,19

Opioid Selection Considerations, Including Selection of Dose, Duration, and Route of Administration

Three guidelines recommended using the lowest effective dose, supported by expert consensus and observational data in the outpatient setting demonstrating that overdose risk increases with opioid dose.16-18 Three guidelines recommended using short-acting opioids and/or avoiding use of long-acting/extended-release opioids for acute pain based on expert consensus.16-18 Two guidelines recommended using as-needed rather than scheduled dosing of opioids based on expert recommendation.16, 17

Strategies to Minimize the Risk of Opioid-Related Adverse Events

Several strategies to minimize the risk of opioid-related adverse events were identified, but most were only recommended by a single guideline. Strategies recommended by more than one guideline included using a recognized opioid dose conversion guide when prescribing, reviewing, or changing opioid prescriptions (based on expert consensus);16,19 avoiding co-administration of parenteral and oral as-needed opioids, and if as-needed opioids from different routes are necessary, providing a clear indication for use of each (based on expert consensus and other guidelines);17,19 and avoiding/using caution when co-prescribing opioids with other central nervous system depressant medications16,17 (supported by observational studies demonstrating increased risk in the outpatient setting).

Safe Practices on Discharge

All 4 of the guidelines recommended prescribing a limited duration of opioids for the acute pain episode; however the maximum recommended duration varied widely from one week to 30 days.16-19 It is important to note that because these guidelines were not focused on hospitalization specifically, these maximum recommended durations of use reflect the entire acute pain episode (ie, not prescribing on discharge specifically). The guideline with the longest maximum recommended duration was from NICE, based in the United Kingdom, while the US-based guideline development groups uniformly recommended 1 to 2 weeks as the maximum duration of opioid use, including the period of hospitalization.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review identified only 4 existing guidelines that included recommendations on safe opioid prescribing practices for managing acute, noncancer pain, outside of the context of specific conditions, specific nonhospital settings, or the intensive care setting. Although 2 of the identified guidelines offered sparse recommendations specific to the hospital setting, we found no guidelines that focused exclusively on the period of hospitalization specifically outside of the perioperative period. Furthermore, the guideline recommendations were largely based on expert opinion. Although these factors limit the confidence with which the recommendations can be applied to the hospital setting, they nonetheless represent the best guidance currently available to standardize and improve the safety of prescribing opioids in the hospital setting.

This paucity of guidance specific to patients hospitalized in general, nonintensive care areas of the hospital is important because pain management in this setting differs in a number of ways from pain management in the ambulatory or intensive care unit settings (including the post-anesthesia care unit). First, there are differences in the monitoring strategies that are available in each of these settings (eg, variability in nurse-to-patient ratios, frequency of measuring vital signs, and availability of continuous pulse oximetry/capnography). Second, there are differences in available/feasible routes of medication administration depending on the setting of care. Finally, there are differences in the patients themselves, including severity of illness, baseline and expected functional status, pain severity, and ability to communicate.

Accordingly, to avoid substantial heterogeneity in recommendations obtained from this review, we chose to focus on guidelines most relevant to clinicians practicing medicine in nonintensive care areas of the hospital. This resulted in the exclusion of 2 guidelines intended for anesthesiologists that focused exclusively on perioperative management and included use of advanced management procedures beyond the scope of practice for general internists,20,21 and one guideline that focused on management in the intensive care unit.22 Within the set of guidelines included in this review, we did include recommendations designated for the postoperative period that we felt were relevant to the care of hospitalized patients more generally. In fact, the ACOEM guideline, which includes postoperative recommendations, specifically noted that these recommendations are mostly comparable to those for treating acute pain more generally.16

In addition to the lack of guidance specific to the setting in which most hospitalists practice, most of the recommendations in the existing guidelines are based on expert consensus. Guidelines based on expert opinion typically carry a lower strength of recommendation, and, accordingly, should be applied with some caution and accompanied by diligent tracking of outcome metrics, as these recommendations are applied to local health systems. Recommendations may have unintended consequences that are not necessarily apparent at the outset, and the specific circumstances of each patient must be considered when deciding how best to apply recommendations. Additional research will be necessary to track the impact of the recommended prescribing practices on patient outcomes, particularly given that many states have already begun instituting regulations on safe opioid prescribing despite the limited nature of the evidence. Furthermore, although several studies have identified patient- and prescribing-related risk factors for opioid-related adverse events in surgical patient populations, given the differences in patient characteristics and prescribing patterns in these settings, research to understand the risk factors in hospitalized medical patients specifically is important to inform evidence-based, safe prescribing recommendations in this setting.

Despite the largely expert consensus-based nature of the recommendations, we found substantial overlap in the recommendations between the guidelines, spanning our prespecified topics of interest related to safe prescribing. Most guidelines recommended restricting opioid use to severe pain or pain that has not responded to nonopioid therapy, checking PDMPs, using the lowest effective dose, and using short-acting opioids and/or avoiding use of long-acting/extended-release opioids for acute pain. There was less consensus on risk mitigation strategies, where the majority of recommendations were endorsed by only 1 or 2 guidelines. Finally, all 4 guidelines recommended prescribing a limited duration of opioids for the acute pain episode, with US-based guidelines recommending 1 to 2 weeks as the maximum duration of opioid use, including the period of hospitalization.

There are limitations to our evaluation. As previously noted, in order to avoid substantial heterogeneity in management recommendations, we excluded 2 guidelines intended for anesthesiologists that focused exclusively on perioperative management,20,21 and one guideline focused on management in the intensive care unit.22 Accordingly, recommendations contained in this review may or may not be applicable to those settings, and readers interested in those settings specifically are directed to those guidelines. Additionally, we decided to exclude guidelines that focused on managing acute pain in specific conditions (eg, sickle cell disease and pancreatitis) because our goal was to identify generalizable principles of safe prescribing of opioids that apply regardless of clinical condition. Despite this goal, it is important to recognize that not all of the recommendations are generalizable to all types of pain; clinicians interested in management principles specific to certain disease states are encouraged to review disease-specific informational material. Finally, although we used rigorous, pre-defined search criteria and registered our protocol on PROSPERO, it is possible that our search strategy missed relevant guidelines.

In conclusion, we identified few guidelines on safe opioid prescribing practices for managing acute, noncancer pain, outside of the context of specific conditions or nonhospital settings, and no guidelines focused on acute pain management in general, nonintensive care areas of the hospital specifically. Nevertheless, the guidelines that we identified make consistent recommendations related to our prespecified topic areas of relevance to the hospital setting, although most recommendations are based exclusively on expert opinion. Our systematic review nonetheless provides guidance in an area where guidance has thus far been limited. Future research should investigate risk factors for opioid-related adverse events in hospitalized, nonsurgical patients, and the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce their occurrence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Herzig had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Kevin Vuernick, Jenna Goldstein, Meghan Mallouk, and Chris Frost, MD, from SHM for their facilitation of this project and dedication to this purpose.

Disclosures: Dr. Herzig received compensation from the Society of Hospital Medicine for her editorial role at the Journal of Hospital Medicine (unrelated to the present work). Dr. Jena received consulting fees from Pfizer, Inc., Hill Rom Services, Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and Precision Health Economics (all unrelated to the present work). None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) provided administrative assistance and material support, but had no role in or influence on the scientific conduct of the study. Dr. Herzig was funded by grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mosher was supported, in part, by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and Office of Research and Development and Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation Center (CIN 13-412). None of the funding agencies had involvement in any aspect of the study, including design, conduct, or reporting of the study

Pain is prevalent among hospitalized patients, occurring in 52%-71% of patients in cross-sectional surveys.1-3 Opioid administration is also common, with more than half of nonsurgical patients in United States (US) hospitals receiving at least one dose of opioid during hospitalization.4 Studies have also begun to define the degree to which hospital prescribing contributes to long-term use. Among opioid-naïve patients admitted to the hospital, 15%-25% fill an opioid prescription in the week after hospital discharge,5,6 43% of such patients fill another opioid prescription 90 days postdischarge,6 and 15% meet the criteria for long-term use at one year.7 With about 37 million discharges from US hospitals each year,8 these estimates suggest that hospitalization contributes to initiation of long-term opioid use in millions of adults each year.

Additionally, studies in the emergency department and hospital settings demonstrate large variations in prescribing of opioids between providers and hospitals.4,9 Variation unrelated to patient characteristics highlights areas of clinical uncertainty and the corresponding need for prescribing standards and guidance. To our knowledge, there are no existing guidelines on safe prescribing of opioids in hospitalized patients, aside from guidelines specifically focused on the perioperative, palliative care, or end-of-life settings.

Thus, in the context of the current opioid epidemic, the Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) sought to develop a consensus statement to assist clinicians practicing medicine in the inpatient setting in safe prescribing of opioids for acute, noncancer pain on the medical services. We define “safe” prescribing as proposed by Aronson: “a process that recommends a medicine appropriate to the patient’s condition and minimizes the risk of undue harm from it.”10 To inform development of the consensus statement, SHM convened a working group to systematically review existing guidelines on the more general management of acute pain. This article describes the methods and results of our systematic review of existing guidelines for managing acute pain. The Consensus Statement derived from these existing guidelines, applied to the hospital setting, appears in a companion article.

METHODS

Steps in the systematic review process included: 1) searching for relevant guidelines, 2) applying exclusion criteria, 3) assessing the quality of the guidelines, and 4) synthesizing guideline recommendations to identify issues potentially relevant to medical inpatients with acute pain. Details of the protocol for this systematic review were registered on PROSPERO and can be accessed at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?RecordID=71846.

Data Sources and Search Terms

Guideline Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

We defined guidelines as statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harm of alternative care options, consistent with the National Academies’ definition.11 To be eligible, guidelines had to be published in English and include recommendations on prescribing opioids for acute, noncancer pain. We excluded guidelines focused on chronic pain or palliative care, guidelines derived entirely from another guideline, and guidelines published before 2010, since such guidelines may contain outdated information.12 Because we were interested in general principles regarding safe use of opioids for managing acute pain, we excluded guidelines that focused exclusively on specific disease processes (eg, cancer, low-back pain, and sickle cell anemia). As we were specifically interested in the management of acute pain in the hospital setting, we also excluded guidelines that focused exclusively on specific nonhospital settings of care (eg, outpatient care clinics and nursing homes). We included guidelines related to care in the emergency department (ED) given the hospital-based location of care and the high degree of similarity in scope of practice and patient population, as most hospitalized adults are admitted through the ED. Finally, we excluded guidelines focusing on management in the intensive care setting (including the post-anesthesia care unit) given the inherent differences in patient population and management options between the intensive and nonintensive care areas of the hospital.

Guideline Quality Assessment

Guideline Synthesis and Analysis

We extracted recommendations from each guideline related to the following topics: 1) deciding when to use opioids, nonopioid medications, and nonmedication-based pain management modalities, 2) best practices in screening/monitoring/education prior to prescribing an opioid and/or during treatment, 3) opioid selection considerations, including selection of dose, duration, and route of administration, 4) strategies to minimize the risk of opioid-related adverse events, and 5) safe practices on discharge.

Role of the Funding Source

The Society of Hospital Medicine provided administrative and material support for the project, but had no role in the design or execution of the scientific evaluation.

RESULTS

Guideline Quality Assessment

See Table 1 for the AGREE II scaled domain scores, and Appendix Table 1 for the ratings on each individual item within a domain. The range of scaled scores for each of the AGREE II domains were as follows: Scope and purpose 52%-89%, stakeholder involvement 30%-81%, rigor of development 46%-81%, clarity of presentation 59%-72%, applicability 10%-57%, and editorial independence 42%-78%. Overall guideline assessment scores ranged from 4 to 5.33 on a scale from 1 to 7. Three of the guidelines (NICE, ACOEM, and WSAMDG)16,17,19 were recommended for use without modification by 2 out of 3 guideline appraisers, and one of the guidelines (ACEP)18 was recommended for use with modification by all 3 appraisers. The guideline by NICE19 was rated the highest both overall (5.33), and on 4 of the 6 AGREE II domains.

Although the guidelines each included a systematic review of the literature, the NICE19 and WSAMDG17 guidelines did not include the strength of recommendations or provide clear links between each recommendation and the underlying evidence base. When citations were present, we reviewed them to determine the type of data upon which the recommendations were based and included this information in Table 2. The majority of the recommendations in Table 2 are based on expert opinion alone, or other guidelines.

Guideline Synthesis and Analysis

Table 2 contains a synthesis of the recommendations related to each of our 5 prespecified content areas. Despite the generally low quality of the evidence supporting the recommendations, there were many areas of concordance across guidelines.

Deciding When to Use Opioids, Nonopioid Medications, and Nonmedication-Based Pain Management Modalities

Three out of 4 guidelines recommended restricting opioid use to severe pain or pain that has not responded to nonopioid therapy,16-18 2 guidelines recommended treating mild to moderate pain with nonopioid medications, including acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),16,17 and 2 guidelines recommended co-prescribing opioids with nonopioid analgesic medications to reduce total opioid requirements and improve pain control.16,17 Each of these recommendations was supported by at least one randomized controlled trial.

Best Practices in Screening/Monitoring/Education to Occur Prior to Prescribing an Opioid and/or During Treatment

Three guidelines recommended checking prescription drug monitoring programs (PDMPs), all based on expert consensus.16-18 Only the WSAMDG guideline offered guidance as to the optimal timing to check the PDMP in this setting, specifically recommending to check before prescribing opioids.17 Two guidelines also recommended helping patients set reasonable expectations about their recovery and educating patients about the risks/side effects of opioid therapy, all based on expert consensus or other guidelines.17,19

Opioid Selection Considerations, Including Selection of Dose, Duration, and Route of Administration

Three guidelines recommended using the lowest effective dose, supported by expert consensus and observational data in the outpatient setting demonstrating that overdose risk increases with opioid dose.16-18 Three guidelines recommended using short-acting opioids and/or avoiding use of long-acting/extended-release opioids for acute pain based on expert consensus.16-18 Two guidelines recommended using as-needed rather than scheduled dosing of opioids based on expert recommendation.16, 17

Strategies to Minimize the Risk of Opioid-Related Adverse Events

Several strategies to minimize the risk of opioid-related adverse events were identified, but most were only recommended by a single guideline. Strategies recommended by more than one guideline included using a recognized opioid dose conversion guide when prescribing, reviewing, or changing opioid prescriptions (based on expert consensus);16,19 avoiding co-administration of parenteral and oral as-needed opioids, and if as-needed opioids from different routes are necessary, providing a clear indication for use of each (based on expert consensus and other guidelines);17,19 and avoiding/using caution when co-prescribing opioids with other central nervous system depressant medications16,17 (supported by observational studies demonstrating increased risk in the outpatient setting).

Safe Practices on Discharge

All 4 of the guidelines recommended prescribing a limited duration of opioids for the acute pain episode; however the maximum recommended duration varied widely from one week to 30 days.16-19 It is important to note that because these guidelines were not focused on hospitalization specifically, these maximum recommended durations of use reflect the entire acute pain episode (ie, not prescribing on discharge specifically). The guideline with the longest maximum recommended duration was from NICE, based in the United Kingdom, while the US-based guideline development groups uniformly recommended 1 to 2 weeks as the maximum duration of opioid use, including the period of hospitalization.

DISCUSSION

This systematic review identified only 4 existing guidelines that included recommendations on safe opioid prescribing practices for managing acute, noncancer pain, outside of the context of specific conditions, specific nonhospital settings, or the intensive care setting. Although 2 of the identified guidelines offered sparse recommendations specific to the hospital setting, we found no guidelines that focused exclusively on the period of hospitalization specifically outside of the perioperative period. Furthermore, the guideline recommendations were largely based on expert opinion. Although these factors limit the confidence with which the recommendations can be applied to the hospital setting, they nonetheless represent the best guidance currently available to standardize and improve the safety of prescribing opioids in the hospital setting.

This paucity of guidance specific to patients hospitalized in general, nonintensive care areas of the hospital is important because pain management in this setting differs in a number of ways from pain management in the ambulatory or intensive care unit settings (including the post-anesthesia care unit). First, there are differences in the monitoring strategies that are available in each of these settings (eg, variability in nurse-to-patient ratios, frequency of measuring vital signs, and availability of continuous pulse oximetry/capnography). Second, there are differences in available/feasible routes of medication administration depending on the setting of care. Finally, there are differences in the patients themselves, including severity of illness, baseline and expected functional status, pain severity, and ability to communicate.

Accordingly, to avoid substantial heterogeneity in recommendations obtained from this review, we chose to focus on guidelines most relevant to clinicians practicing medicine in nonintensive care areas of the hospital. This resulted in the exclusion of 2 guidelines intended for anesthesiologists that focused exclusively on perioperative management and included use of advanced management procedures beyond the scope of practice for general internists,20,21 and one guideline that focused on management in the intensive care unit.22 Within the set of guidelines included in this review, we did include recommendations designated for the postoperative period that we felt were relevant to the care of hospitalized patients more generally. In fact, the ACOEM guideline, which includes postoperative recommendations, specifically noted that these recommendations are mostly comparable to those for treating acute pain more generally.16

In addition to the lack of guidance specific to the setting in which most hospitalists practice, most of the recommendations in the existing guidelines are based on expert consensus. Guidelines based on expert opinion typically carry a lower strength of recommendation, and, accordingly, should be applied with some caution and accompanied by diligent tracking of outcome metrics, as these recommendations are applied to local health systems. Recommendations may have unintended consequences that are not necessarily apparent at the outset, and the specific circumstances of each patient must be considered when deciding how best to apply recommendations. Additional research will be necessary to track the impact of the recommended prescribing practices on patient outcomes, particularly given that many states have already begun instituting regulations on safe opioid prescribing despite the limited nature of the evidence. Furthermore, although several studies have identified patient- and prescribing-related risk factors for opioid-related adverse events in surgical patient populations, given the differences in patient characteristics and prescribing patterns in these settings, research to understand the risk factors in hospitalized medical patients specifically is important to inform evidence-based, safe prescribing recommendations in this setting.

Despite the largely expert consensus-based nature of the recommendations, we found substantial overlap in the recommendations between the guidelines, spanning our prespecified topics of interest related to safe prescribing. Most guidelines recommended restricting opioid use to severe pain or pain that has not responded to nonopioid therapy, checking PDMPs, using the lowest effective dose, and using short-acting opioids and/or avoiding use of long-acting/extended-release opioids for acute pain. There was less consensus on risk mitigation strategies, where the majority of recommendations were endorsed by only 1 or 2 guidelines. Finally, all 4 guidelines recommended prescribing a limited duration of opioids for the acute pain episode, with US-based guidelines recommending 1 to 2 weeks as the maximum duration of opioid use, including the period of hospitalization.

There are limitations to our evaluation. As previously noted, in order to avoid substantial heterogeneity in management recommendations, we excluded 2 guidelines intended for anesthesiologists that focused exclusively on perioperative management,20,21 and one guideline focused on management in the intensive care unit.22 Accordingly, recommendations contained in this review may or may not be applicable to those settings, and readers interested in those settings specifically are directed to those guidelines. Additionally, we decided to exclude guidelines that focused on managing acute pain in specific conditions (eg, sickle cell disease and pancreatitis) because our goal was to identify generalizable principles of safe prescribing of opioids that apply regardless of clinical condition. Despite this goal, it is important to recognize that not all of the recommendations are generalizable to all types of pain; clinicians interested in management principles specific to certain disease states are encouraged to review disease-specific informational material. Finally, although we used rigorous, pre-defined search criteria and registered our protocol on PROSPERO, it is possible that our search strategy missed relevant guidelines.

In conclusion, we identified few guidelines on safe opioid prescribing practices for managing acute, noncancer pain, outside of the context of specific conditions or nonhospital settings, and no guidelines focused on acute pain management in general, nonintensive care areas of the hospital specifically. Nevertheless, the guidelines that we identified make consistent recommendations related to our prespecified topic areas of relevance to the hospital setting, although most recommendations are based exclusively on expert opinion. Our systematic review nonetheless provides guidance in an area where guidance has thus far been limited. Future research should investigate risk factors for opioid-related adverse events in hospitalized, nonsurgical patients, and the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce their occurrence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Herzig had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank Kevin Vuernick, Jenna Goldstein, Meghan Mallouk, and Chris Frost, MD, from SHM for their facilitation of this project and dedication to this purpose.

Disclosures: Dr. Herzig received compensation from the Society of Hospital Medicine for her editorial role at the Journal of Hospital Medicine (unrelated to the present work). Dr. Jena received consulting fees from Pfizer, Inc., Hill Rom Services, Inc., Bristol Myers Squibb, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Vertex Pharmaceuticals, and Precision Health Economics (all unrelated to the present work). None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding: The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) provided administrative assistance and material support, but had no role in or influence on the scientific conduct of the study. Dr. Herzig was funded by grant number K23AG042459 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Mosher was supported, in part, by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations and Office of Research and Development and Health Services Research and Development Service (HSR&D) through the Comprehensive Access and Delivery Research and Evaluation Center (CIN 13-412). None of the funding agencies had involvement in any aspect of the study, including design, conduct, or reporting of the study

1. Melotti RM, Samolsky-Dekel BG, Ricchi E, et al. Pain prevalence and predictors among inpatients in a major Italian teaching hospital. A baseline survey towards a pain free hospital. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(5):485-495. PubMed

2. Sawyer J, Haslam L, Robinson S, Daines P, Stilos K. Pain prevalence study in a large Canadian teaching hospital. Pain Manag Nurs. 2008;9(3):104-112. PubMed

3. Strohbuecker B, Mayer H, Evers GC, Sabatowski R. Pain prevalence in hospitalized patients in a German university teaching hospital. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(5):498-506. PubMed

4. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in US hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81. PubMed

5. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;31(5):478-485. PubMed

6. Jena AB, Goldman D, Karaca-Mandic P. Hospital prescribing of opioids to medicare neneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):990-997. PubMed

7. Mosher HJ, Hofmeyer B, Hadlandsmyth K, Richardson KK, Lund BC. Predictors of long-term opioid use after opioid initiation at discharge from medical and surgical hospitalizations. JHM. Accepted for Publication November 11, 2017. PubMed

8. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #180. 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2015. PubMed

9. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):663-673. PubMed

10. Aronson JK. Balanced prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(6):629-632. PubMed

11. IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

12. Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, et al. Validity of the agency for healthcare research and quality clinical practice guidelines: How quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA. 2001;286(12):1461-1467. PubMed

13. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-E842. PubMed

14. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 1: performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):1045-1052. PubMed

15. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):E472-E478. PubMed

16. Hegmann KT, Weiss MS, Bowden K, et al. ACOEM practice guidelines: opioids for treatment of acute, subacute, chronic, and postoperative pain. J Occup Environ Med. 2014;56(12):e143-e159. PubMed

17. Washington State Agency Medical Directors’ Group. Interagency Guideline on Prescribing Opioids for Pain. http://www.agencymeddirectors.wa.gov/Files/2015AMDGOpioidGuideline.pdf. Accessed December 5, 2017.

18. Cantrill SV, Brown MD, Carlisle RJ, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the prescribing of opioids for adult patients in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(4):499-525. PubMed

19. National Institute for Healthcare Excellence. Controlled drugs: Safe use and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng46/chapter/Recommendations. Accessed December 5, 2017.

20. Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(2):248-273. PubMed

21. Apfelbaum JL, Silverstein JH, Chung FF, et al. Practice guidelines for postanesthetic care: an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Postanesthetic Care. Anesthesiology. 2013;118(2):291-307. PubMed

22. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(1):263-306. PubMed

1. Melotti RM, Samolsky-Dekel BG, Ricchi E, et al. Pain prevalence and predictors among inpatients in a major Italian teaching hospital. A baseline survey towards a pain free hospital. Eur J Pain. 2005;9(5):485-495. PubMed

2. Sawyer J, Haslam L, Robinson S, Daines P, Stilos K. Pain prevalence study in a large Canadian teaching hospital. Pain Manag Nurs. 2008;9(3):104-112. PubMed

3. Strohbuecker B, Mayer H, Evers GC, Sabatowski R. Pain prevalence in hospitalized patients in a German university teaching hospital. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(5):498-506. PubMed

4. Herzig SJ, Rothberg MB, Cheung M, Ngo LH, Marcantonio ER. Opioid utilization and opioid-related adverse events in nonsurgical patients in US hospitals. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):73-81. PubMed

5. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, Keniston A, Frank JW, Binswanger IA. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;31(5):478-485. PubMed

6. Jena AB, Goldman D, Karaca-Mandic P. Hospital prescribing of opioids to medicare neneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(7):990-997. PubMed

7. Mosher HJ, Hofmeyer B, Hadlandsmyth K, Richardson KK, Lund BC. Predictors of long-term opioid use after opioid initiation at discharge from medical and surgical hospitalizations. JHM. Accepted for Publication November 11, 2017. PubMed

8. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #180. 2014. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb180-Hospitalizations-United-States-2012.pdf. Accessed June 29, 2015. PubMed

9. Barnett ML, Olenski AR, Jena AB. Opioid-prescribing patterns of emergency physicians and risk of long-term use. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(7):663-673. PubMed

10. Aronson JK. Balanced prescribing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;62(6):629-632. PubMed

11. IOM (Institute of Medicine). 2011. Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

12. Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, et al. Validity of the agency for healthcare research and quality clinical practice guidelines: How quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA. 2001;286(12):1461-1467. PubMed

13. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182(18):E839-E842. PubMed

14. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 1: performance, usefulness and areas for improvement. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):1045-1052. PubMed

15. Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, et al. Development of the AGREE II, part 2: Assessment of validity of items and tools to support application. CMAJ. 2010;182(10):E472-E478. PubMed