User login

Multiple Draining Sinus Tracts on the Thigh

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterial Infection

An injury sustained in a wet environment that results in chronic indolent abscesses, nodules, or draining sinus tracts suggests a mycobacterial infection. In our patient, a culture revealed MycobacteriuM fortuitum, which is classified in the rapid grower nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) group, along with Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus.1 The patient’s history of skin injury while cutting wet grass and the common presence of M fortuitum in the environment suggested that the organism entered the wound. The patient healed completely following surgical excision and a 2-month course of clarithromycin 1 g daily and rifampin 600 mg daily.

MycobacteriuM fortuitum was first isolated from an amphibian source in 1905 and later identified in a human with cutaneous infection in 1938. It commonly is found in soil and water.2 Skin and soft-tissue infections with M fortuitum usually are acquired from direct entry of the organism through a damaged skin barrier from trauma, medical injection, surgery, or tattoo placement.2,3

Skin lesions caused by NTM often are nonspecific and can mimic a variety of other dermatologic conditions, making clinical diagnosis challenging. As such, cutaneous manifestations of M fortuitum infection can include recurrent cutaneous abscesses, nodular lesions, chronic discharging sinuses, cellulitis, and surgical site infections.4 Although cutaneous infection with M fortuitum classically manifests with a single subcutaneous nodule at the site of trauma or surgery,5 it also can manifest as multiple draining sinus tracts, as seen in our patient. Hence, the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous NTM infection is challenging, especially when M fortuitum skin manifestations can take up to 4 to 6 weeks to develop after inoculation. Diagnosis often requires a detailed patient history, tissue cultures, and histopathology.5

In recent years, rapid detection with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques has been employed more widely. Notably, a molecular system based on multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting was shown to have a sensitivity of up to 54% for distinguishing M fortuitum from other NTM.6 More recently, a 2-step real-time PCR method has demonstrated diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for differentiating NTM from Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and identifying the causative NTM agent.7

Compared to immunocompetent individuals, those who are immunocompromised are more susceptible to less pathogenic strains of NTM, which can cause dissemination and lead to tenosynovitis, myositis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis.8-12 Nonetheless, cases of infections with NTM—including M fortuitum—are becoming harder to treat. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms and point mutations have been demonstrated in the ribosomal RNA methylase gene erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in the rrl gene related to linezolid resistance.13 Due to increasing inducible resistance to common classes of antibiotics, such as macrolides and linezolid, treatment of M fortuitum requires multidrug regimens.13,14 Drug susceptibility testing also may be required, as M fortuitum has shown low resistance to tigecycline, tetracycline, cefmetazole, imipenem, and aminoglycosides (eg, amikacin, tobramycin, neomycin, gentamycin). Surgery is an important adjunctive tool in treating M fortuitum infections; patients with a single lesion are more likely to undergo surgical treatment alone or in combination with antibiotic therapy.15 More recently, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy has been explored as an alternative to eliminate NTM, including M fortuitum.16

The differential diagnosis for skin lesions manifesting with draining fistulae and sinus tracts includes conditions with infectious (cellulitis and chromomycosis) and inflammatory (pyoderma gangrenosum [PG] and hidradenitis suppurativa [HS]) causes.

Cellulitis is a common infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that predominantly is caused by gram-positive organisms such as β-hemolytic streptococci.17 Clinical manifestations include acute skin erythema, swelling, tenderness, and warmth. The legs are the most common sites of infection, but any area of the skin can be involved.17 Cellulitis comprises 10% of all infectious disease hospitalizations and up to 11% of all dermatologic admissions.18,19 It frequently is misdiagnosed, perhaps due to the lack of a reliable confirmatory laboratory test or imaging study, in addition to the plethora of diseases that mimic cellulitis, such as stasis dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, contact dermatitis, lymphedema, eosinophilic cellulitis, and papular urticaria.20,21 The consequences of misdiagnosis include but are not limited to unnecessary hospitalizations, inappropriate antibiotic use, and delayed management of the disease; thus, there is an urgent need for a reliable standard test to confirm the diagnosis, especially among nonspecialist physicians. 20 Most patients with uncomplicated cellulitis can be treated with empiric oral antibiotics that target β-hemolytic streptococci (ie, penicillin V potassium, amoxicillin).17 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus coverage generally is unnecessary for nonpurulent cellulitis, but clinicians can consider adding amoxicillin-clavulanate, dicloxacillin, and cephalexin to the regimen. For purulent cellulitis, incision and drainage should be performed. In severe cases that manifest with sepsis, altered mental status, or hemodynamic instability, inpatient management is required.17

Chromomycosis (also known as chromoblastomycosis) is a chronic, indolent, granulomatous, suppurative mycosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue22 that is caused by traumatic inoculation of various fungi of the order Chaetothyriales and family Herpotrichiellaceae, which are present in soil, plants, and decomposing wood. Chromomycosis is prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions.23,24 Clinically, it manifests as oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic lesions around an infection site that can manifest as papules with centrifugal growth evolving into nodular, verrucous, plaque, tumoral, or atrophic forms.22 Diagnosis is made with direct microscopy using potassium hydroxide, which reveals muriform bodies. Fungal culture in Sabouraud agar also can be used to isolate the causative pathogen.22 Unfortunately, chromomycosis is difficult to treat, with low cure rates and high relapse rates. Antifungal agents combined with surgery, cryotherapy, or thermotherapy often are used, with cure rates ranging from 15% to 80%.22,25

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a reactive noninfectious inflammatory dermatosis associated with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. The exact etiology is not clearly understood, but it generally is considered an autoinflammatory disorder.26 The most common form—classical PG—occurs in approximately 85% of cases and manifests as a painful erythematous lesion that progresses to a blistered or necrotic ulcer. It primarily affects the lower legs but can occur in other body sites.27 The diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms after excluding other similar conditions; histopathology of biopsied wound tissues often are required for confirmation. Treatment of PG starts with fast-acting immunosuppressive drugs (corticosteroids and/or cyclosporine) followed by slowacting immunosuppressive drugs (biologics).26

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic recurrent disease of the hair follicle unit that develops after puberty.28 Clinically, HS manifests with painful nodules, abscesses, chronically draining fistulas, and scarring in areas of the body rich in apocrine glands.29,30 Treatment of HS is challenging due to its diverse clinical manifestations and unclear etiology. Topical therapy, systemic treatments, biologic agents, surgery, and light therapy have shown variable results.28,31

- Franco-Paredes C, Marcos LA, Henao-Martínez AF, et al. Cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;32: E00069-18. doi:10.1128/CMR.00069-18

- Brown TH. The rapidly growing mycobacteria—MycobacteriuM fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Infect Control. 1985;6:283-238. doi:10.1017/s0195941700061762

- Hooper J; Beltrami EJ; Santoro F; et al. Remember the fite: a case of cutaneous MycobacteriuM fortuitum infection. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:214-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002336

- Franco-Paredes C, Chastain DB, Allen L, et al. Overview of cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2018;5:228-232. doi:10.1007/s40475-018-0161-7

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-77. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.017

- Peixoto ADS, Montenegro LML, Lima AS, et al. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria species by multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:E20200211. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0211-2020

- Park J, Kwak N, Chae JC, et al. A two-step real-time PCR method to identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and six dominant nontuberculous mycobacterial infections from clinical specimens. Microbiol Spectr. 2023:E0160623. doi:10.1128/spectrum.01606-23

- Fowler J, Mahlen SD. Localized cutaneous infections in immunocompetent individuals due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:1106-1109. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0203-RS

- Gardini G, Gregori N, Matteelli A, et al. Mycobacterial skin infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2022;35:79-87. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000820

- Wang SH, Pancholi P. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014;16:438. doi:10.1007/s11908-014-0438-5

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Mougari F, Guglielmetti L, Raskine L, et al. Infections caused by Mycobacterium abscessus: epidemiology, diagnostic tools and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14:1139-1154. doi:10.1080/14787210.201 6.1238304

- Tu HZ, Lee HS, Chen YS, et al. High rates of antimicrobial resistance in rapidly growing mycobacterial infections in Taiwan. Pathogens. 2022;11:969. doi:10.3390/pathogens11090969

- Hashemzadeh M, Zadegan Dezfuli AA, Khosravi AD, et al. F requency of mutations in erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in rrl related to linezolid resistance in clinical isolates of MycobacteriuM fortuitum in Iran. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2023;70:167-176. doi:10.1556/030.2023.02020

- Uslan DZ, Kowalski TJ, Wengenack NL, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections due to rapidly growing mycobacteria: comparison of clinical features, treatment, and susceptibility. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1287-1292. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1287

- Miretti M, Juri L, Peralta A, et al. Photoinactivation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria using Zn-phthalocyanine loaded into liposomes. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2022;136:102247. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2022.102247

- Bystritsky RJ. Cellulitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2021;35:49-60. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2020.10.002

- Christensen K, Holman R, Steiner C, et al. Infectious disease hospitalizations in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1025-1035. doi:10.1086/605562

- Yang JJ, Maloney NJ, Bach DQ, et al. Dermatology in the emergency department: prescriptions, rates of inpatient admission, and predictors of high utilization in the United States from 1996 to 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1480-1483. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2020.07.055

- Cutler TS, Jannat-Khah DP, Kam B, et al. Prevalence of misdiagnosis of cellulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2023;18:254-261. doi:10.1002/jhm.12977

- Keller EC, Tomecki KJ, Alraies MC. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:547-52. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11121

- Brito AC, Bittencourt MJS. Chromoblastomycosis: an etiological, epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and treatment update. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:495-506. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187321

- McGinnis MR. Chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: new concepts, diagnosis, and mycology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:1-16.

- Rubin HA, Bruce S, Rosen T, et al. Evidence for percutaneous inoculation as the mode of transmission for chromoblastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:951-954.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís V, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Maverakis E, Marzano AV, Le ST, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:81. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0213-x

- George C, Deroide F, Rustin M. Pyoderma gangrenosum—a guide to diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19:224-228. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.19-3-224

- Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-1049. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26083.1

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118-122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Daxhelet M, Suppa M, White J, et al. Proposed definitions of typical lesions in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2020;236:431-438. doi:10.1159/000507348

- Amat-Samaranch V, Agut-Busquet E, Vilarrasa E, et al. New perspectives on the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211055920. doi:10.1177/20406223211055920

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterial Infection

An injury sustained in a wet environment that results in chronic indolent abscesses, nodules, or draining sinus tracts suggests a mycobacterial infection. In our patient, a culture revealed MycobacteriuM fortuitum, which is classified in the rapid grower nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) group, along with Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus.1 The patient’s history of skin injury while cutting wet grass and the common presence of M fortuitum in the environment suggested that the organism entered the wound. The patient healed completely following surgical excision and a 2-month course of clarithromycin 1 g daily and rifampin 600 mg daily.

MycobacteriuM fortuitum was first isolated from an amphibian source in 1905 and later identified in a human with cutaneous infection in 1938. It commonly is found in soil and water.2 Skin and soft-tissue infections with M fortuitum usually are acquired from direct entry of the organism through a damaged skin barrier from trauma, medical injection, surgery, or tattoo placement.2,3

Skin lesions caused by NTM often are nonspecific and can mimic a variety of other dermatologic conditions, making clinical diagnosis challenging. As such, cutaneous manifestations of M fortuitum infection can include recurrent cutaneous abscesses, nodular lesions, chronic discharging sinuses, cellulitis, and surgical site infections.4 Although cutaneous infection with M fortuitum classically manifests with a single subcutaneous nodule at the site of trauma or surgery,5 it also can manifest as multiple draining sinus tracts, as seen in our patient. Hence, the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous NTM infection is challenging, especially when M fortuitum skin manifestations can take up to 4 to 6 weeks to develop after inoculation. Diagnosis often requires a detailed patient history, tissue cultures, and histopathology.5

In recent years, rapid detection with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques has been employed more widely. Notably, a molecular system based on multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting was shown to have a sensitivity of up to 54% for distinguishing M fortuitum from other NTM.6 More recently, a 2-step real-time PCR method has demonstrated diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for differentiating NTM from Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and identifying the causative NTM agent.7

Compared to immunocompetent individuals, those who are immunocompromised are more susceptible to less pathogenic strains of NTM, which can cause dissemination and lead to tenosynovitis, myositis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis.8-12 Nonetheless, cases of infections with NTM—including M fortuitum—are becoming harder to treat. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms and point mutations have been demonstrated in the ribosomal RNA methylase gene erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in the rrl gene related to linezolid resistance.13 Due to increasing inducible resistance to common classes of antibiotics, such as macrolides and linezolid, treatment of M fortuitum requires multidrug regimens.13,14 Drug susceptibility testing also may be required, as M fortuitum has shown low resistance to tigecycline, tetracycline, cefmetazole, imipenem, and aminoglycosides (eg, amikacin, tobramycin, neomycin, gentamycin). Surgery is an important adjunctive tool in treating M fortuitum infections; patients with a single lesion are more likely to undergo surgical treatment alone or in combination with antibiotic therapy.15 More recently, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy has been explored as an alternative to eliminate NTM, including M fortuitum.16

The differential diagnosis for skin lesions manifesting with draining fistulae and sinus tracts includes conditions with infectious (cellulitis and chromomycosis) and inflammatory (pyoderma gangrenosum [PG] and hidradenitis suppurativa [HS]) causes.

Cellulitis is a common infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that predominantly is caused by gram-positive organisms such as β-hemolytic streptococci.17 Clinical manifestations include acute skin erythema, swelling, tenderness, and warmth. The legs are the most common sites of infection, but any area of the skin can be involved.17 Cellulitis comprises 10% of all infectious disease hospitalizations and up to 11% of all dermatologic admissions.18,19 It frequently is misdiagnosed, perhaps due to the lack of a reliable confirmatory laboratory test or imaging study, in addition to the plethora of diseases that mimic cellulitis, such as stasis dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, contact dermatitis, lymphedema, eosinophilic cellulitis, and papular urticaria.20,21 The consequences of misdiagnosis include but are not limited to unnecessary hospitalizations, inappropriate antibiotic use, and delayed management of the disease; thus, there is an urgent need for a reliable standard test to confirm the diagnosis, especially among nonspecialist physicians. 20 Most patients with uncomplicated cellulitis can be treated with empiric oral antibiotics that target β-hemolytic streptococci (ie, penicillin V potassium, amoxicillin).17 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus coverage generally is unnecessary for nonpurulent cellulitis, but clinicians can consider adding amoxicillin-clavulanate, dicloxacillin, and cephalexin to the regimen. For purulent cellulitis, incision and drainage should be performed. In severe cases that manifest with sepsis, altered mental status, or hemodynamic instability, inpatient management is required.17

Chromomycosis (also known as chromoblastomycosis) is a chronic, indolent, granulomatous, suppurative mycosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue22 that is caused by traumatic inoculation of various fungi of the order Chaetothyriales and family Herpotrichiellaceae, which are present in soil, plants, and decomposing wood. Chromomycosis is prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions.23,24 Clinically, it manifests as oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic lesions around an infection site that can manifest as papules with centrifugal growth evolving into nodular, verrucous, plaque, tumoral, or atrophic forms.22 Diagnosis is made with direct microscopy using potassium hydroxide, which reveals muriform bodies. Fungal culture in Sabouraud agar also can be used to isolate the causative pathogen.22 Unfortunately, chromomycosis is difficult to treat, with low cure rates and high relapse rates. Antifungal agents combined with surgery, cryotherapy, or thermotherapy often are used, with cure rates ranging from 15% to 80%.22,25

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a reactive noninfectious inflammatory dermatosis associated with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. The exact etiology is not clearly understood, but it generally is considered an autoinflammatory disorder.26 The most common form—classical PG—occurs in approximately 85% of cases and manifests as a painful erythematous lesion that progresses to a blistered or necrotic ulcer. It primarily affects the lower legs but can occur in other body sites.27 The diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms after excluding other similar conditions; histopathology of biopsied wound tissues often are required for confirmation. Treatment of PG starts with fast-acting immunosuppressive drugs (corticosteroids and/or cyclosporine) followed by slowacting immunosuppressive drugs (biologics).26

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic recurrent disease of the hair follicle unit that develops after puberty.28 Clinically, HS manifests with painful nodules, abscesses, chronically draining fistulas, and scarring in areas of the body rich in apocrine glands.29,30 Treatment of HS is challenging due to its diverse clinical manifestations and unclear etiology. Topical therapy, systemic treatments, biologic agents, surgery, and light therapy have shown variable results.28,31

The Diagnosis: Mycobacterial Infection

An injury sustained in a wet environment that results in chronic indolent abscesses, nodules, or draining sinus tracts suggests a mycobacterial infection. In our patient, a culture revealed MycobacteriuM fortuitum, which is classified in the rapid grower nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) group, along with Mycobacterium chelonae and Mycobacterium abscessus.1 The patient’s history of skin injury while cutting wet grass and the common presence of M fortuitum in the environment suggested that the organism entered the wound. The patient healed completely following surgical excision and a 2-month course of clarithromycin 1 g daily and rifampin 600 mg daily.

MycobacteriuM fortuitum was first isolated from an amphibian source in 1905 and later identified in a human with cutaneous infection in 1938. It commonly is found in soil and water.2 Skin and soft-tissue infections with M fortuitum usually are acquired from direct entry of the organism through a damaged skin barrier from trauma, medical injection, surgery, or tattoo placement.2,3

Skin lesions caused by NTM often are nonspecific and can mimic a variety of other dermatologic conditions, making clinical diagnosis challenging. As such, cutaneous manifestations of M fortuitum infection can include recurrent cutaneous abscesses, nodular lesions, chronic discharging sinuses, cellulitis, and surgical site infections.4 Although cutaneous infection with M fortuitum classically manifests with a single subcutaneous nodule at the site of trauma or surgery,5 it also can manifest as multiple draining sinus tracts, as seen in our patient. Hence, the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous NTM infection is challenging, especially when M fortuitum skin manifestations can take up to 4 to 6 weeks to develop after inoculation. Diagnosis often requires a detailed patient history, tissue cultures, and histopathology.5

In recent years, rapid detection with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) techniques has been employed more widely. Notably, a molecular system based on multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting was shown to have a sensitivity of up to 54% for distinguishing M fortuitum from other NTM.6 More recently, a 2-step real-time PCR method has demonstrated diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for differentiating NTM from Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and identifying the causative NTM agent.7

Compared to immunocompetent individuals, those who are immunocompromised are more susceptible to less pathogenic strains of NTM, which can cause dissemination and lead to tenosynovitis, myositis, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis.8-12 Nonetheless, cases of infections with NTM—including M fortuitum—are becoming harder to treat. Several single nucleotide polymorphisms and point mutations have been demonstrated in the ribosomal RNA methylase gene erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in the rrl gene related to linezolid resistance.13 Due to increasing inducible resistance to common classes of antibiotics, such as macrolides and linezolid, treatment of M fortuitum requires multidrug regimens.13,14 Drug susceptibility testing also may be required, as M fortuitum has shown low resistance to tigecycline, tetracycline, cefmetazole, imipenem, and aminoglycosides (eg, amikacin, tobramycin, neomycin, gentamycin). Surgery is an important adjunctive tool in treating M fortuitum infections; patients with a single lesion are more likely to undergo surgical treatment alone or in combination with antibiotic therapy.15 More recently, antimicrobial photodynamic therapy has been explored as an alternative to eliminate NTM, including M fortuitum.16

The differential diagnosis for skin lesions manifesting with draining fistulae and sinus tracts includes conditions with infectious (cellulitis and chromomycosis) and inflammatory (pyoderma gangrenosum [PG] and hidradenitis suppurativa [HS]) causes.

Cellulitis is a common infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that predominantly is caused by gram-positive organisms such as β-hemolytic streptococci.17 Clinical manifestations include acute skin erythema, swelling, tenderness, and warmth. The legs are the most common sites of infection, but any area of the skin can be involved.17 Cellulitis comprises 10% of all infectious disease hospitalizations and up to 11% of all dermatologic admissions.18,19 It frequently is misdiagnosed, perhaps due to the lack of a reliable confirmatory laboratory test or imaging study, in addition to the plethora of diseases that mimic cellulitis, such as stasis dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, contact dermatitis, lymphedema, eosinophilic cellulitis, and papular urticaria.20,21 The consequences of misdiagnosis include but are not limited to unnecessary hospitalizations, inappropriate antibiotic use, and delayed management of the disease; thus, there is an urgent need for a reliable standard test to confirm the diagnosis, especially among nonspecialist physicians. 20 Most patients with uncomplicated cellulitis can be treated with empiric oral antibiotics that target β-hemolytic streptococci (ie, penicillin V potassium, amoxicillin).17 Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus coverage generally is unnecessary for nonpurulent cellulitis, but clinicians can consider adding amoxicillin-clavulanate, dicloxacillin, and cephalexin to the regimen. For purulent cellulitis, incision and drainage should be performed. In severe cases that manifest with sepsis, altered mental status, or hemodynamic instability, inpatient management is required.17

Chromomycosis (also known as chromoblastomycosis) is a chronic, indolent, granulomatous, suppurative mycosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue22 that is caused by traumatic inoculation of various fungi of the order Chaetothyriales and family Herpotrichiellaceae, which are present in soil, plants, and decomposing wood. Chromomycosis is prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions.23,24 Clinically, it manifests as oligosymptomatic or asymptomatic lesions around an infection site that can manifest as papules with centrifugal growth evolving into nodular, verrucous, plaque, tumoral, or atrophic forms.22 Diagnosis is made with direct microscopy using potassium hydroxide, which reveals muriform bodies. Fungal culture in Sabouraud agar also can be used to isolate the causative pathogen.22 Unfortunately, chromomycosis is difficult to treat, with low cure rates and high relapse rates. Antifungal agents combined with surgery, cryotherapy, or thermotherapy often are used, with cure rates ranging from 15% to 80%.22,25

Pyoderma gangrenosum is a reactive noninfectious inflammatory dermatosis associated with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. The exact etiology is not clearly understood, but it generally is considered an autoinflammatory disorder.26 The most common form—classical PG—occurs in approximately 85% of cases and manifests as a painful erythematous lesion that progresses to a blistered or necrotic ulcer. It primarily affects the lower legs but can occur in other body sites.27 The diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms after excluding other similar conditions; histopathology of biopsied wound tissues often are required for confirmation. Treatment of PG starts with fast-acting immunosuppressive drugs (corticosteroids and/or cyclosporine) followed by slowacting immunosuppressive drugs (biologics).26

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic recurrent disease of the hair follicle unit that develops after puberty.28 Clinically, HS manifests with painful nodules, abscesses, chronically draining fistulas, and scarring in areas of the body rich in apocrine glands.29,30 Treatment of HS is challenging due to its diverse clinical manifestations and unclear etiology. Topical therapy, systemic treatments, biologic agents, surgery, and light therapy have shown variable results.28,31

- Franco-Paredes C, Marcos LA, Henao-Martínez AF, et al. Cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;32: E00069-18. doi:10.1128/CMR.00069-18

- Brown TH. The rapidly growing mycobacteria—MycobacteriuM fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Infect Control. 1985;6:283-238. doi:10.1017/s0195941700061762

- Hooper J; Beltrami EJ; Santoro F; et al. Remember the fite: a case of cutaneous MycobacteriuM fortuitum infection. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:214-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002336

- Franco-Paredes C, Chastain DB, Allen L, et al. Overview of cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2018;5:228-232. doi:10.1007/s40475-018-0161-7

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-77. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.017

- Peixoto ADS, Montenegro LML, Lima AS, et al. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria species by multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:E20200211. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0211-2020

- Park J, Kwak N, Chae JC, et al. A two-step real-time PCR method to identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and six dominant nontuberculous mycobacterial infections from clinical specimens. Microbiol Spectr. 2023:E0160623. doi:10.1128/spectrum.01606-23

- Fowler J, Mahlen SD. Localized cutaneous infections in immunocompetent individuals due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:1106-1109. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0203-RS

- Gardini G, Gregori N, Matteelli A, et al. Mycobacterial skin infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2022;35:79-87. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000820

- Wang SH, Pancholi P. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014;16:438. doi:10.1007/s11908-014-0438-5

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Mougari F, Guglielmetti L, Raskine L, et al. Infections caused by Mycobacterium abscessus: epidemiology, diagnostic tools and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14:1139-1154. doi:10.1080/14787210.201 6.1238304

- Tu HZ, Lee HS, Chen YS, et al. High rates of antimicrobial resistance in rapidly growing mycobacterial infections in Taiwan. Pathogens. 2022;11:969. doi:10.3390/pathogens11090969

- Hashemzadeh M, Zadegan Dezfuli AA, Khosravi AD, et al. F requency of mutations in erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in rrl related to linezolid resistance in clinical isolates of MycobacteriuM fortuitum in Iran. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2023;70:167-176. doi:10.1556/030.2023.02020

- Uslan DZ, Kowalski TJ, Wengenack NL, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections due to rapidly growing mycobacteria: comparison of clinical features, treatment, and susceptibility. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1287-1292. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1287

- Miretti M, Juri L, Peralta A, et al. Photoinactivation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria using Zn-phthalocyanine loaded into liposomes. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2022;136:102247. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2022.102247

- Bystritsky RJ. Cellulitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2021;35:49-60. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2020.10.002

- Christensen K, Holman R, Steiner C, et al. Infectious disease hospitalizations in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1025-1035. doi:10.1086/605562

- Yang JJ, Maloney NJ, Bach DQ, et al. Dermatology in the emergency department: prescriptions, rates of inpatient admission, and predictors of high utilization in the United States from 1996 to 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1480-1483. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2020.07.055

- Cutler TS, Jannat-Khah DP, Kam B, et al. Prevalence of misdiagnosis of cellulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2023;18:254-261. doi:10.1002/jhm.12977

- Keller EC, Tomecki KJ, Alraies MC. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:547-52. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11121

- Brito AC, Bittencourt MJS. Chromoblastomycosis: an etiological, epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and treatment update. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:495-506. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187321

- McGinnis MR. Chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: new concepts, diagnosis, and mycology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:1-16.

- Rubin HA, Bruce S, Rosen T, et al. Evidence for percutaneous inoculation as the mode of transmission for chromoblastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:951-954.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís V, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Maverakis E, Marzano AV, Le ST, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:81. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0213-x

- George C, Deroide F, Rustin M. Pyoderma gangrenosum—a guide to diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19:224-228. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.19-3-224

- Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-1049. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26083.1

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118-122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Daxhelet M, Suppa M, White J, et al. Proposed definitions of typical lesions in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2020;236:431-438. doi:10.1159/000507348

- Amat-Samaranch V, Agut-Busquet E, Vilarrasa E, et al. New perspectives on the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211055920. doi:10.1177/20406223211055920

- Franco-Paredes C, Marcos LA, Henao-Martínez AF, et al. Cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2018;32: E00069-18. doi:10.1128/CMR.00069-18

- Brown TH. The rapidly growing mycobacteria—MycobacteriuM fortuitum and Mycobacterium chelonae. Infect Control. 1985;6:283-238. doi:10.1017/s0195941700061762

- Hooper J; Beltrami EJ; Santoro F; et al. Remember the fite: a case of cutaneous MycobacteriuM fortuitum infection. Am J Dermatopathol. 2023;45:214-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000002336

- Franco-Paredes C, Chastain DB, Allen L, et al. Overview of cutaneous mycobacterial infections. Curr Trop Med Rep. 2018;5:228-232. doi:10.1007/s40475-018-0161-7

- Gonzalez-Santiago TM, Drage LA. Nontuberculous mycobacteria: skin and soft tissue infections. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:563-77. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.017

- Peixoto ADS, Montenegro LML, Lima AS, et al. Identification of nontuberculous mycobacteria species by multiplex real-time PCR with high-resolution melting. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2020;53:E20200211. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0211-2020

- Park J, Kwak N, Chae JC, et al. A two-step real-time PCR method to identify Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections and six dominant nontuberculous mycobacterial infections from clinical specimens. Microbiol Spectr. 2023:E0160623. doi:10.1128/spectrum.01606-23

- Fowler J, Mahlen SD. Localized cutaneous infections in immunocompetent individuals due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2014;138:1106-1109. doi:10.5858/arpa.2012-0203-RS

- Gardini G, Gregori N, Matteelli A, et al. Mycobacterial skin infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2022;35:79-87. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000820

- Wang SH, Pancholi P. Mycobacterial skin and soft tissue infection. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2014;16:438. doi:10.1007/s11908-014-0438-5

- Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367-416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST

- Mougari F, Guglielmetti L, Raskine L, et al. Infections caused by Mycobacterium abscessus: epidemiology, diagnostic tools and treatment. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2016;14:1139-1154. doi:10.1080/14787210.201 6.1238304

- Tu HZ, Lee HS, Chen YS, et al. High rates of antimicrobial resistance in rapidly growing mycobacterial infections in Taiwan. Pathogens. 2022;11:969. doi:10.3390/pathogens11090969

- Hashemzadeh M, Zadegan Dezfuli AA, Khosravi AD, et al. F requency of mutations in erm(39) related to clarithromycin resistance and in rrl related to linezolid resistance in clinical isolates of MycobacteriuM fortuitum in Iran. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2023;70:167-176. doi:10.1556/030.2023.02020

- Uslan DZ, Kowalski TJ, Wengenack NL, et al. Skin and soft tissue infections due to rapidly growing mycobacteria: comparison of clinical features, treatment, and susceptibility. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1287-1292. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.10.1287

- Miretti M, Juri L, Peralta A, et al. Photoinactivation of non-tuberculous mycobacteria using Zn-phthalocyanine loaded into liposomes. Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2022;136:102247. doi:10.1016/j.tube.2022.102247

- Bystritsky RJ. Cellulitis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2021;35:49-60. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2020.10.002

- Christensen K, Holman R, Steiner C, et al. Infectious disease hospitalizations in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:1025-1035. doi:10.1086/605562

- Yang JJ, Maloney NJ, Bach DQ, et al. Dermatology in the emergency department: prescriptions, rates of inpatient admission, and predictors of high utilization in the United States from 1996 to 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1480-1483. doi:10.1016/J.JAAD.2020.07.055

- Cutler TS, Jannat-Khah DP, Kam B, et al. Prevalence of misdiagnosis of cellulitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hosp Med. 2023;18:254-261. doi:10.1002/jhm.12977

- Keller EC, Tomecki KJ, Alraies MC. Distinguishing cellulitis from its mimics. Cleve Clin J Med. 2012;79:547-52. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11121

- Brito AC, Bittencourt MJS. Chromoblastomycosis: an etiological, epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic, and treatment update. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:495-506. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20187321

- McGinnis MR. Chromoblastomycosis and phaeohyphomycosis: new concepts, diagnosis, and mycology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1983;8:1-16.

- Rubin HA, Bruce S, Rosen T, et al. Evidence for percutaneous inoculation as the mode of transmission for chromoblastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:951-954.

- Bonifaz A, Paredes-Solís V, Saúl A. Treating chromoblastomycosis with systemic antifungals. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:247-254.

- Maverakis E, Marzano AV, Le ST, et al. Pyoderma gangrenosum. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:81. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0213-x

- George C, Deroide F, Rustin M. Pyoderma gangrenosum—a guide to diagnosis and management. Clin Med (Lond). 2019;19:224-228. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.19-3-224

- Narla S, Lyons AB, Hamzavi IH. The most recent advances in understanding and managing hidradenitis suppurativa. F1000Res. 2020;9:F1000 Faculty Rev-1049. doi:10.12688/f1000research.26083.1

- Garg A, Lavian J, Lin G, et al. Incidence of hidradenitis suppurativa in the United States: a sex- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:118-122. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.02.005

- Daxhelet M, Suppa M, White J, et al. Proposed definitions of typical lesions in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology. 2020;236:431-438. doi:10.1159/000507348

- Amat-Samaranch V, Agut-Busquet E, Vilarrasa E, et al. New perspectives on the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2021;12:20406223211055920. doi:10.1177/20406223211055920

A 40-year-old woman presented with multiple draining sinus tracts on the right thigh following an injury sustained weeks earlier while mowing wet grass.

Extensive Multidrug-Resistant Dermatophytosis From Trichophyton indotineae

To the Editor:

Historically, commonly available antifungal medications have been effective for treating dermatophytosis (tinea). However, recent tinea outbreaks caused by Trichophyton indotineae—a dermatophyte often resistant to terbinafine and sometimes to other antifungals—have been reported in South Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Australia.1-5

Three confirmed cases of T indotineae dermatophytosis in the United States were reported in 2023 in New York3,6; a fourth confirmed case was reported in 2024 in Pennsylvania.7 Post hoc laboratory testing of fungal isolates in New York in 2022 and 2023 identified an additional 11 cases.8 We present a case of extensive multidrug-resistant tinea caused by T indotineae in a man in California.

An otherwise healthy 65-year-old man who had traveled to Europe in the past 3 months presented to his primary care physician with a widespread pruritic rash (Figure 1). He was treated with 2 weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d and topical medicines, including clotrimazole cream 1%, fluocinonide ointment 0.05%, and clobetasol ointment 0.05% without improvement. Subsequently, 2 weeks of oral griseofulvin microsize 500 mg/d also proved ineffective. An antibody test was negative for HIV. His hemoglobin A1c was 6.2% (reference range, ≤5.6%). The patient was referred to dermatology.

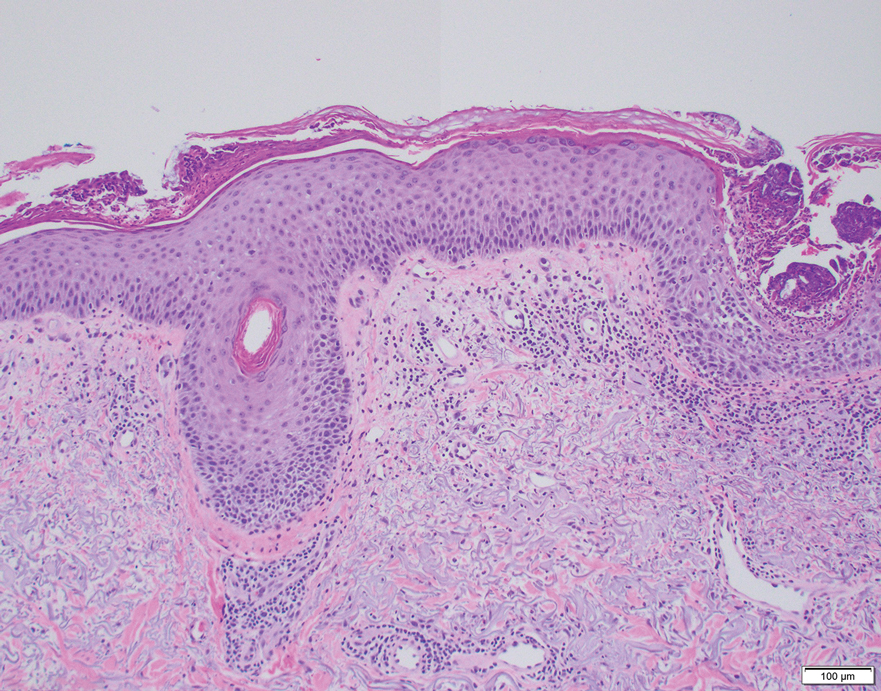

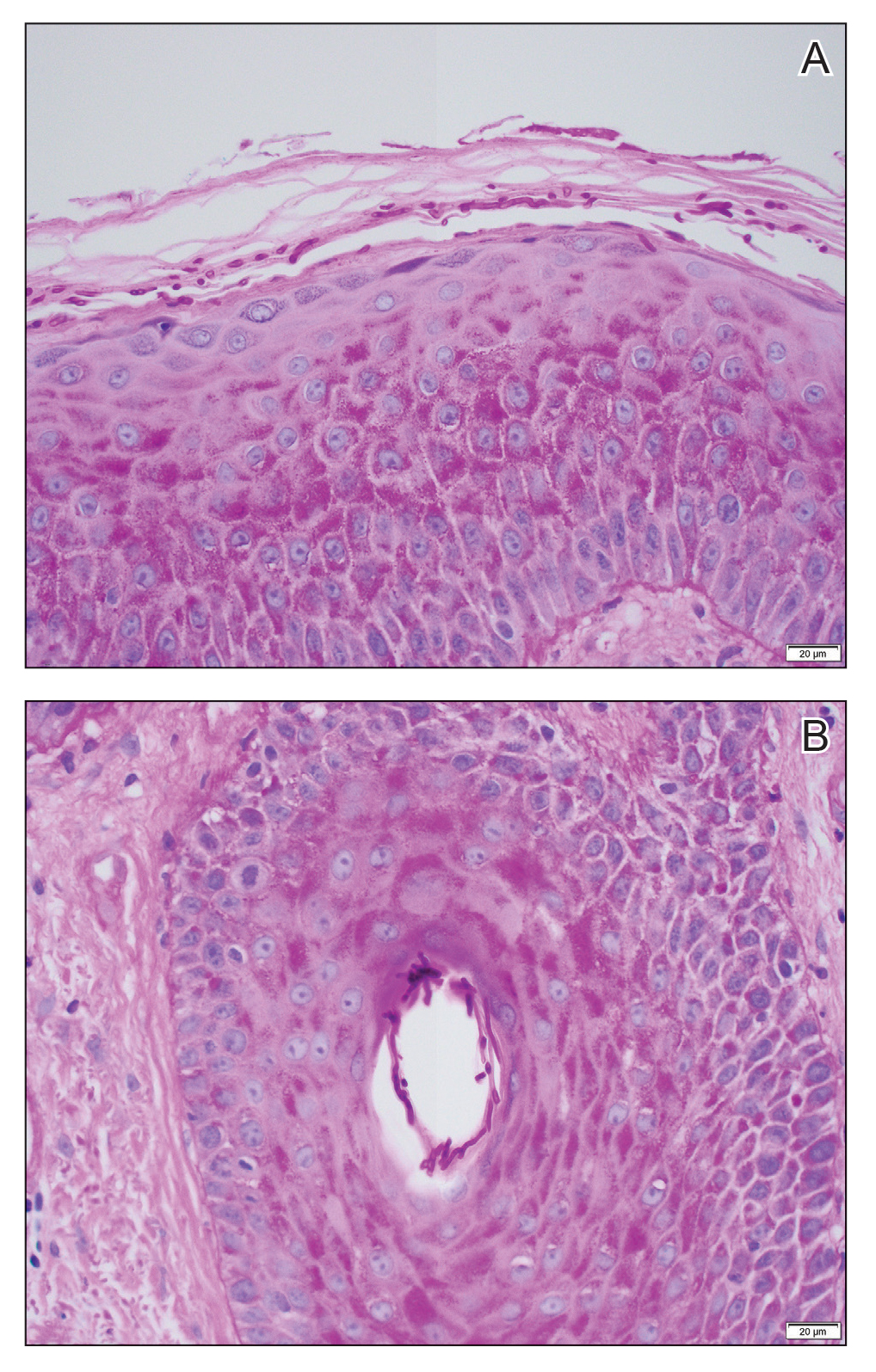

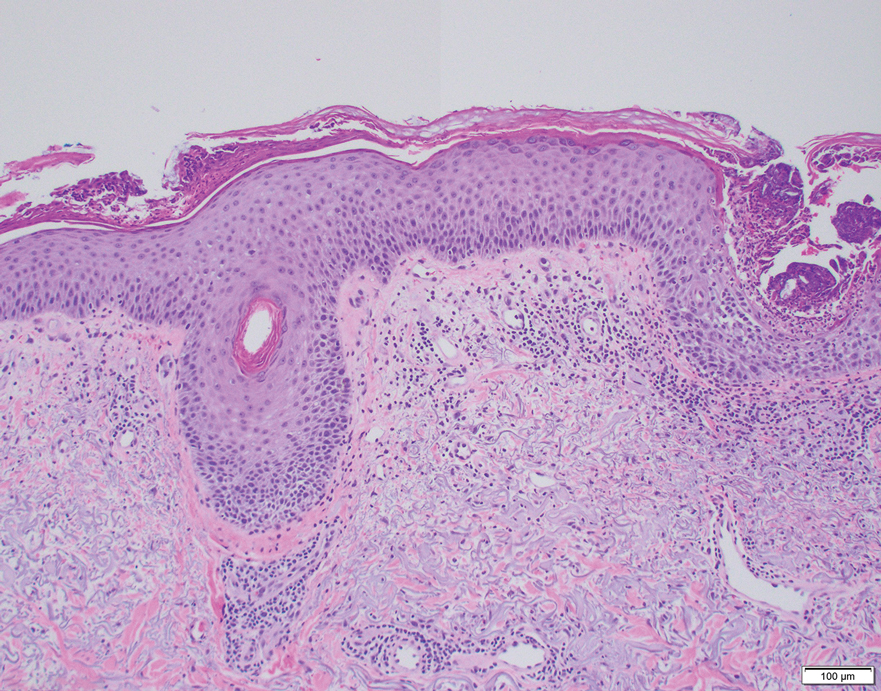

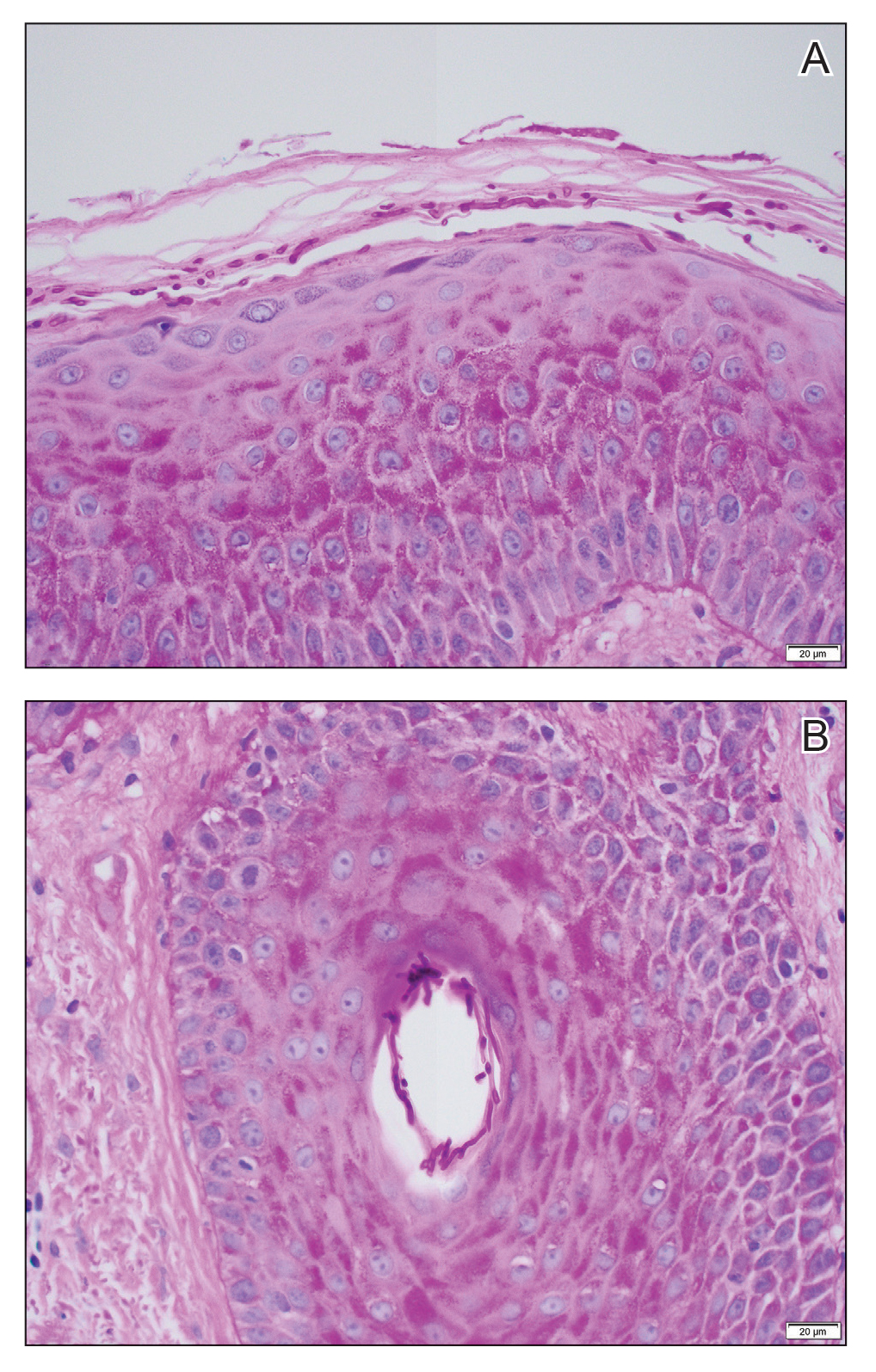

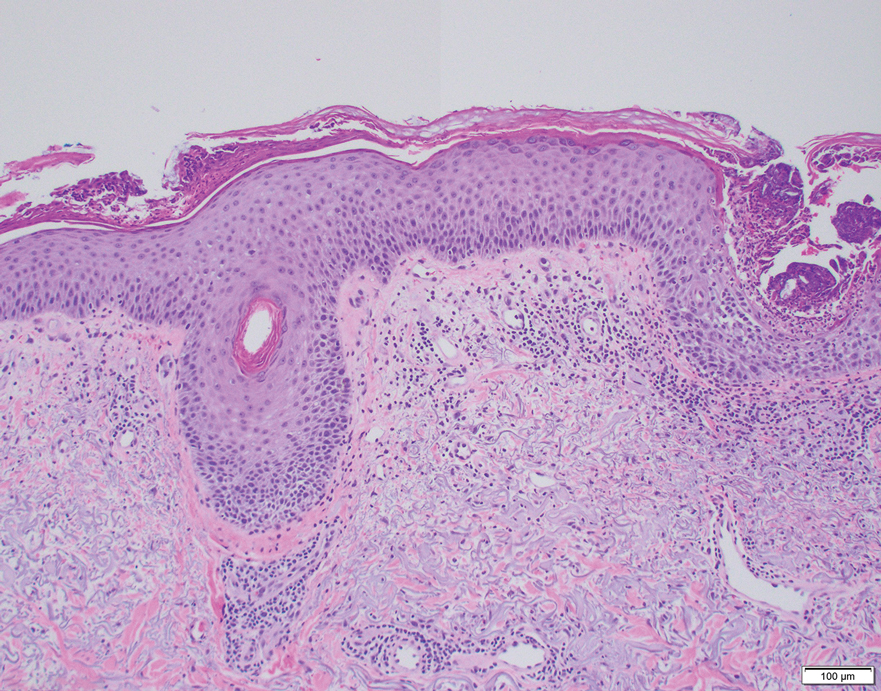

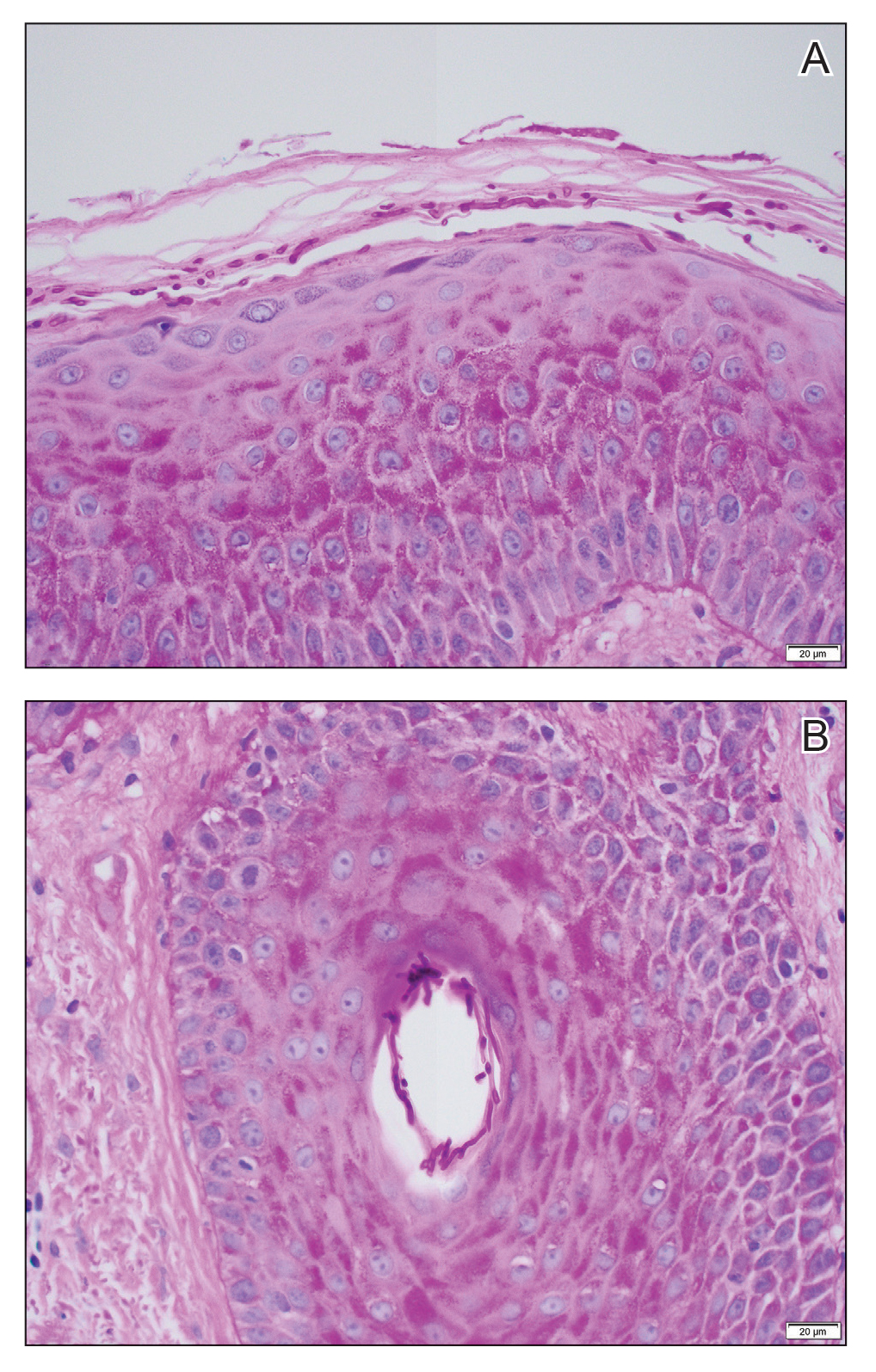

Erythematous plaques—many scaly throughout and some annular with central clearing—were present on the arms, legs, and torso as well as in the groin. Honey crust was present on some plaques on the leg. A potassium hydroxide preparation showed abundant fungal hyphae. Material for fungal and bacterial cultures was collected. The patient was treated again with oral terbinafine 250 mg/d, an oral prednisone taper starting at 60 mg/d for a presumed id reaction, and various oral antihistamines for pruritus; all were ineffective. A bacterial culture showed only mixed skin flora. Oral fluconazole 200 mg/d was prescribed. A skin biopsy specimen showed compact orthokeratosis and parakeratosis of the stratum corneum with few neutrophils and focal pustule formation (Figure 2). Superficial perivascular inflammation, including lymphocytes, histiocytes, and few neutrophils, was present. A periodic acid–Schiff stain showed fungal hyphae in the stratum corneum and a hair follicle (Figure 3). After approximately 2 weeks, mold was identified in the fungal culture. Approximately 2 weeks thereafter, the organism was reported as Trichophyton species.

The rash did not improve; resistance to terbinafine, griseofulvin, and fluconazole was suspected clinically. The fungal isolate was sent to a reference laboratory (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio). Meanwhile, oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily and ketoconazole cream 2% were prescribed; the rash began to improve. A serum itraconazole trough level obtained 4 days after treatment initiation was 0.5 μg/mL (reference range, ≥0.6 μg/mL). The evening itraconazole dose was increased to 300 mg; a subsequent trough level was 0.8 μg/mL.

Approximately 1 month after the fungal isolate was sent to the reference laboratory, T indotineae was confirmed based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of internal transcribed spacer region sequences. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) obtained through antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) were reported for fluconazole (8 μg/mL), griseofulvin (2 μg/mL), itraconazole (≤0.03 μg/mL), posaconazole (≤0.03 μg/mL), terbinafine (≥2 μg/mL), and voriconazole (0.125 μg/mL).

Approximately 7 weeks after itraconazole and ketoconazole were started, the rash had completely resolved. Nearly 8 months later (at the time this article was written), the rash had not recurred.

We report a unique case of T indotineae in a patient residing in California. Post hoc laboratory testing of dermatophyte isolates sent to the University of Texas reference laboratory identified terbinafine-resistant T indotineae specimens from the United States and Canada dating to 2017; clinical characteristics of patients from whom those isolates were obtained were unavailable.9

Trichophyton indotineae dermatophytosis typically is more extensive, inflamed, and pruritic, as well as likely more contagious, than tinea caused by other dermatophytes.5 Previously called Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VIII when first isolated in 2017, the pathogen was renamed T indotineae in 2020 after important genetic differences were discovered between it and other T mentagrophytes species.5 The emergence of T indotineae has been attributed to concomitant use of topical steroids and antifungals,5,10 inappropriate prescribing of antifungals,5 and nonadherence to antifungal treatment.5

Likely risk factors for T indotineae infection include suboptimal hygiene, overcrowded conditions, hot and humid environments, and tight-fitting synthetic clothing.4 Transmission from family members appears common,5 especially when fomites are shared.4 A case reported in Pennsylvania likely was acquired through sexual contact.7 Travel to South Asia has been associated with acquisition of T indotineae infection,3,5-7 though our patient and some others had not traveled there.3,8 It is not clear whether immunosuppression and diabetes mellitus are associated with T indotineae infection.4,5,8 Trichophyton indotineae also can affect animals,11 though zoonotic transmission has not been reported.4

Not all T indotineae isolates are resistant to one or more antifungals; furthermore, antifungal resistance in other dermatophyte species has been reported.5 Terbinafine resistance in T indotineae is conferred by mutations in the gene encoding squalene epoxidase, which helps synthesize ergosterol—a component of the cell membrane in fungi.2,4,5,12 Although clinical cut-points for MIC obtained by AFST are not well established, T indotineae MICs for terbinafine of 0.5 μg/mL or more correlate with resistance.9 Resistance to azoles has been linked to overexpression of transporter genes, which increase azole efflux from cells, as well as to mutations in the gene encoding lanosterol 14α demethylase.4,12,13

Potassium hydroxide preparations and fungal cultures cannot differentiate T indotineae from other dermatophytes that typically cause tinea.5,14 Histopathologic findings in our case were no different than those of non–T indotineae dermatophytes. Only molecular testing using PCR assays to sequence internal transcribed spacer genes can confirm T indotineae infection. However, PCR assays and AFST are not available in many US laboratories.5 Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry has shown promise in distinguishing T indotineae from other dermatophytes, though its clinical use is limited and it cannot assess terbinafine sensitivity.15,16 Clinicians in the United States who want to test specimens from cases suspicious for T indotineae infection should contact their local or state health department or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for assistance.3,5

Systemic treatment typically is necessary for T indotineae infection.5 Combinations of oral and topical azoles have been used, as well as topical ciclopirox, amorolfine (not available in the United States), and luliconazole.1,5,17-21

Itraconazole has emerged as the treatment of choice for T indotineae tinea, typically at 200 mg/d and often for courses of more than 3 months.5 Testing for serum itraconazole trough levels, as done for our patient, typically is not recommended. Clinicians should counsel patients to take itraconazole with high-fat foods and an acidic beverage to increase bioavailability.5 Potential adverse effects of itraconazole include heart failure and numerous drug-drug interactions.5,22 Patients with T indotineae dermatophytosis should avoid sharing personal belongings and having skin-to-skin contact of affected areas with others.4

Dermatologists who suspect T indotineae infection should work with public health agencies that can assist with testing and undertake infection surveillance, prevention, and control.5,23 Challenges to diagnosing and managing T indotineae infection include lack of awareness among dermatology providers, the need for specialized laboratory testing to confirm infection, lack of established clinical cut-points for MICs from AFST, the need for longer duration of treatment vs what is needed for typical tinea, and potential challenges with insurance coverage for testing and treatment. Empiric treatment with itraconazole should be considered when terbinafine-resistant dermatophytosis is suspected or when terbinafine-resistant T indotineae infection is confirmed.

Acknowledgments—Jeremy Gold, MD; Dallas J. Smith, PharmD; and Shawn Lockhart, PhD, all of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Mycotic Diseases Branch (Atlanta, Georgia), provided helpful comments to the authors in preparing the manuscript of this article.

- Uhrlaß S, Verma SB, Gräser Y, al. Trichophyton indotineae—an emerging pathogen causing recalcitrant dermatophytoses in India and worldwide—a multidimensional perspective. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8:757. doi:10.3390/jof8070757

- Jabet A, Brun S, Normand A-C, et al. Extensive dermatophytosis caused by terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton indotineae, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:229-233. doi:10.3201/eid2801.210883

- Caplan AS, Chaturvedi S, Zhu Y, et al. Notes from the field. First reported U.S. cases of tinea caused by Trichophyton indotineae—New York City, December 2021-March 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:536-537. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7219a4

- Jabet A, Normand A-C, Brun S, et al. Trichophyton indotineae, from epidemiology to therapeutic. J Mycol Med. 2023;33:101383. doi:10.1016/j.mycmed.2023.101383

- Hill RC, Caplan AS, Elewski B, et al. Expert panel review of skin and hair dermatophytoses in an era of antifungal resistance. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25:359-389. doi:10.1007/s40257-024-00848-1

- Caplan AS, Zakhem GA, Pomeranz MK. Trichophyton mentagrophytes internal transcribed spacer genotype VIII. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1130. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2645

- Spivack S, Gold JAW, Lockhart SR, et al. Potential sexual transmission of antifungal-resistant Trichophyton indotineae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30:807-809. doi:10.3201/eid3004.240115

- Caplan AS, Todd GC, Zhu Y, et al. Clinical course, antifungal susceptibility, and genomic sequencing of Trichophyton indotineae. JAMA Dermatol. Published online May 15, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1126

- Cañete-Gibas CF, Mele J, Patterson HP, et al. Terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes and the presence of Trichophyton indotineae in North America. J Clin Microbiol. 2023;61:e0056223. doi:10.1128/jcm.00562-23

- Gupta AK, Venkataraman M, Hall DC, et al. The emergence of Trichophyton indotineae: implications for clinical practice. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:857-861.

- Oladzad V, Nasrollahi Omran A, Haghani I, et al. Multi-drug resistance Trichophyton indotineae in a stray dog. Res Vet Sci. 2024;166:105105. doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2023.105105

- Martinez-Rossi NM, Bitencourt TA, Peres NTA, et al. Dermatophyte resistance to antifungal drugs: mechanisms and prospectus. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1108. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01108

- Sacheli R, Hayette MP. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: genetic considerations, clinical presentations and alternative therapies. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;711:983. doi:10.3390/jof7110983

- Gupta AK, Cooper EA. Dermatophytosis (tinea) and other superficial fungal infections. In: Hospenthal DR, Rinaldi MG, eds. Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Mycoses. Humana Press; 2008:355-381.

- Normand A-C, Moreno-Sabater A, Jabet A, et al. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry online identification of Trichophyton indotineae using the MSI-2 application. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8:1103. doi:10.3390/jof8101103

- De Paepe R, Normand A-C, Uhrlaß S, et al. Resistance profile, terbinafine resistance screening and MALDI-TOF MS identification of the emerging pathogen Trichophyton indotineae. Mycopathologia. 2024;189:29. doi:10.1007/s11046-024-00835-4

- Rajagopalan M, Inamadar A, Mittal A, et al. Expert consensus on the management of dermatophytosis in India (ECTODERM India). BMC Dermatol. 2018;18:6. doi:10.1186/s12895-018-0073-1

- Verma SB, Panda S, Nenoff P, et al. The unprecedented epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytosis in India: III. Antifungal resistance and treatment options. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:468-482. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_303_20

- Shaw D, Singh S, Dogra S, et al. MIC and upper limit of wild-type distribution for 13 antifungal agents against a Trichophyton mentagrophytes–Trichophyton interdigitale complex of Indian origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:E01964-19. doi:10.1128/AAC.01964-19

- Burmester A, Hipler U-C, Uhrlaß S, et al. Indian Trichophyton mentagrophytes squalene epoxidase erg1 double mutants show high proportion of combined fluconazole and terbinafine resistance. Mycoses. 2020;63:1175-1180. doi:10.1111/myc.13150

- Khurana A, Agarwal A, Agrawal D, et al. Effect of different itraconazole dosing regimens on cure rates, treatment duration, safety, and relapse rates in adult patients with tinea corporis/cruris: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1269-1278. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3745

- Itraconazole capsule. DailyMed [Internet]. Updated June 3, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=2ab38a8a-3708-4b97-9f7f-8e554a15348d

- Bui TS, Katz KA. Resistant Trichophyton indotineae dermatophytosis—an emerging pandemic, now in the US. JAMA Dermatol. Published online May 15, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1125

To the Editor:

Historically, commonly available antifungal medications have been effective for treating dermatophytosis (tinea). However, recent tinea outbreaks caused by Trichophyton indotineae—a dermatophyte often resistant to terbinafine and sometimes to other antifungals—have been reported in South Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Australia.1-5

Three confirmed cases of T indotineae dermatophytosis in the United States were reported in 2023 in New York3,6; a fourth confirmed case was reported in 2024 in Pennsylvania.7 Post hoc laboratory testing of fungal isolates in New York in 2022 and 2023 identified an additional 11 cases.8 We present a case of extensive multidrug-resistant tinea caused by T indotineae in a man in California.

An otherwise healthy 65-year-old man who had traveled to Europe in the past 3 months presented to his primary care physician with a widespread pruritic rash (Figure 1). He was treated with 2 weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d and topical medicines, including clotrimazole cream 1%, fluocinonide ointment 0.05%, and clobetasol ointment 0.05% without improvement. Subsequently, 2 weeks of oral griseofulvin microsize 500 mg/d also proved ineffective. An antibody test was negative for HIV. His hemoglobin A1c was 6.2% (reference range, ≤5.6%). The patient was referred to dermatology.

Erythematous plaques—many scaly throughout and some annular with central clearing—were present on the arms, legs, and torso as well as in the groin. Honey crust was present on some plaques on the leg. A potassium hydroxide preparation showed abundant fungal hyphae. Material for fungal and bacterial cultures was collected. The patient was treated again with oral terbinafine 250 mg/d, an oral prednisone taper starting at 60 mg/d for a presumed id reaction, and various oral antihistamines for pruritus; all were ineffective. A bacterial culture showed only mixed skin flora. Oral fluconazole 200 mg/d was prescribed. A skin biopsy specimen showed compact orthokeratosis and parakeratosis of the stratum corneum with few neutrophils and focal pustule formation (Figure 2). Superficial perivascular inflammation, including lymphocytes, histiocytes, and few neutrophils, was present. A periodic acid–Schiff stain showed fungal hyphae in the stratum corneum and a hair follicle (Figure 3). After approximately 2 weeks, mold was identified in the fungal culture. Approximately 2 weeks thereafter, the organism was reported as Trichophyton species.

The rash did not improve; resistance to terbinafine, griseofulvin, and fluconazole was suspected clinically. The fungal isolate was sent to a reference laboratory (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio). Meanwhile, oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily and ketoconazole cream 2% were prescribed; the rash began to improve. A serum itraconazole trough level obtained 4 days after treatment initiation was 0.5 μg/mL (reference range, ≥0.6 μg/mL). The evening itraconazole dose was increased to 300 mg; a subsequent trough level was 0.8 μg/mL.

Approximately 1 month after the fungal isolate was sent to the reference laboratory, T indotineae was confirmed based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of internal transcribed spacer region sequences. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) obtained through antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) were reported for fluconazole (8 μg/mL), griseofulvin (2 μg/mL), itraconazole (≤0.03 μg/mL), posaconazole (≤0.03 μg/mL), terbinafine (≥2 μg/mL), and voriconazole (0.125 μg/mL).

Approximately 7 weeks after itraconazole and ketoconazole were started, the rash had completely resolved. Nearly 8 months later (at the time this article was written), the rash had not recurred.

We report a unique case of T indotineae in a patient residing in California. Post hoc laboratory testing of dermatophyte isolates sent to the University of Texas reference laboratory identified terbinafine-resistant T indotineae specimens from the United States and Canada dating to 2017; clinical characteristics of patients from whom those isolates were obtained were unavailable.9

Trichophyton indotineae dermatophytosis typically is more extensive, inflamed, and pruritic, as well as likely more contagious, than tinea caused by other dermatophytes.5 Previously called Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VIII when first isolated in 2017, the pathogen was renamed T indotineae in 2020 after important genetic differences were discovered between it and other T mentagrophytes species.5 The emergence of T indotineae has been attributed to concomitant use of topical steroids and antifungals,5,10 inappropriate prescribing of antifungals,5 and nonadherence to antifungal treatment.5

Likely risk factors for T indotineae infection include suboptimal hygiene, overcrowded conditions, hot and humid environments, and tight-fitting synthetic clothing.4 Transmission from family members appears common,5 especially when fomites are shared.4 A case reported in Pennsylvania likely was acquired through sexual contact.7 Travel to South Asia has been associated with acquisition of T indotineae infection,3,5-7 though our patient and some others had not traveled there.3,8 It is not clear whether immunosuppression and diabetes mellitus are associated with T indotineae infection.4,5,8 Trichophyton indotineae also can affect animals,11 though zoonotic transmission has not been reported.4

Not all T indotineae isolates are resistant to one or more antifungals; furthermore, antifungal resistance in other dermatophyte species has been reported.5 Terbinafine resistance in T indotineae is conferred by mutations in the gene encoding squalene epoxidase, which helps synthesize ergosterol—a component of the cell membrane in fungi.2,4,5,12 Although clinical cut-points for MIC obtained by AFST are not well established, T indotineae MICs for terbinafine of 0.5 μg/mL or more correlate with resistance.9 Resistance to azoles has been linked to overexpression of transporter genes, which increase azole efflux from cells, as well as to mutations in the gene encoding lanosterol 14α demethylase.4,12,13

Potassium hydroxide preparations and fungal cultures cannot differentiate T indotineae from other dermatophytes that typically cause tinea.5,14 Histopathologic findings in our case were no different than those of non–T indotineae dermatophytes. Only molecular testing using PCR assays to sequence internal transcribed spacer genes can confirm T indotineae infection. However, PCR assays and AFST are not available in many US laboratories.5 Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry has shown promise in distinguishing T indotineae from other dermatophytes, though its clinical use is limited and it cannot assess terbinafine sensitivity.15,16 Clinicians in the United States who want to test specimens from cases suspicious for T indotineae infection should contact their local or state health department or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for assistance.3,5

Systemic treatment typically is necessary for T indotineae infection.5 Combinations of oral and topical azoles have been used, as well as topical ciclopirox, amorolfine (not available in the United States), and luliconazole.1,5,17-21

Itraconazole has emerged as the treatment of choice for T indotineae tinea, typically at 200 mg/d and often for courses of more than 3 months.5 Testing for serum itraconazole trough levels, as done for our patient, typically is not recommended. Clinicians should counsel patients to take itraconazole with high-fat foods and an acidic beverage to increase bioavailability.5 Potential adverse effects of itraconazole include heart failure and numerous drug-drug interactions.5,22 Patients with T indotineae dermatophytosis should avoid sharing personal belongings and having skin-to-skin contact of affected areas with others.4

Dermatologists who suspect T indotineae infection should work with public health agencies that can assist with testing and undertake infection surveillance, prevention, and control.5,23 Challenges to diagnosing and managing T indotineae infection include lack of awareness among dermatology providers, the need for specialized laboratory testing to confirm infection, lack of established clinical cut-points for MICs from AFST, the need for longer duration of treatment vs what is needed for typical tinea, and potential challenges with insurance coverage for testing and treatment. Empiric treatment with itraconazole should be considered when terbinafine-resistant dermatophytosis is suspected or when terbinafine-resistant T indotineae infection is confirmed.

Acknowledgments—Jeremy Gold, MD; Dallas J. Smith, PharmD; and Shawn Lockhart, PhD, all of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Mycotic Diseases Branch (Atlanta, Georgia), provided helpful comments to the authors in preparing the manuscript of this article.

To the Editor:

Historically, commonly available antifungal medications have been effective for treating dermatophytosis (tinea). However, recent tinea outbreaks caused by Trichophyton indotineae—a dermatophyte often resistant to terbinafine and sometimes to other antifungals—have been reported in South Asia, Europe, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and Australia.1-5

Three confirmed cases of T indotineae dermatophytosis in the United States were reported in 2023 in New York3,6; a fourth confirmed case was reported in 2024 in Pennsylvania.7 Post hoc laboratory testing of fungal isolates in New York in 2022 and 2023 identified an additional 11 cases.8 We present a case of extensive multidrug-resistant tinea caused by T indotineae in a man in California.

An otherwise healthy 65-year-old man who had traveled to Europe in the past 3 months presented to his primary care physician with a widespread pruritic rash (Figure 1). He was treated with 2 weeks of oral terbinafine 250 mg/d and topical medicines, including clotrimazole cream 1%, fluocinonide ointment 0.05%, and clobetasol ointment 0.05% without improvement. Subsequently, 2 weeks of oral griseofulvin microsize 500 mg/d also proved ineffective. An antibody test was negative for HIV. His hemoglobin A1c was 6.2% (reference range, ≤5.6%). The patient was referred to dermatology.

Erythematous plaques—many scaly throughout and some annular with central clearing—were present on the arms, legs, and torso as well as in the groin. Honey crust was present on some plaques on the leg. A potassium hydroxide preparation showed abundant fungal hyphae. Material for fungal and bacterial cultures was collected. The patient was treated again with oral terbinafine 250 mg/d, an oral prednisone taper starting at 60 mg/d for a presumed id reaction, and various oral antihistamines for pruritus; all were ineffective. A bacterial culture showed only mixed skin flora. Oral fluconazole 200 mg/d was prescribed. A skin biopsy specimen showed compact orthokeratosis and parakeratosis of the stratum corneum with few neutrophils and focal pustule formation (Figure 2). Superficial perivascular inflammation, including lymphocytes, histiocytes, and few neutrophils, was present. A periodic acid–Schiff stain showed fungal hyphae in the stratum corneum and a hair follicle (Figure 3). After approximately 2 weeks, mold was identified in the fungal culture. Approximately 2 weeks thereafter, the organism was reported as Trichophyton species.

The rash did not improve; resistance to terbinafine, griseofulvin, and fluconazole was suspected clinically. The fungal isolate was sent to a reference laboratory (University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio). Meanwhile, oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily and ketoconazole cream 2% were prescribed; the rash began to improve. A serum itraconazole trough level obtained 4 days after treatment initiation was 0.5 μg/mL (reference range, ≥0.6 μg/mL). The evening itraconazole dose was increased to 300 mg; a subsequent trough level was 0.8 μg/mL.

Approximately 1 month after the fungal isolate was sent to the reference laboratory, T indotineae was confirmed based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of internal transcribed spacer region sequences. Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) obtained through antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST) were reported for fluconazole (8 μg/mL), griseofulvin (2 μg/mL), itraconazole (≤0.03 μg/mL), posaconazole (≤0.03 μg/mL), terbinafine (≥2 μg/mL), and voriconazole (0.125 μg/mL).

Approximately 7 weeks after itraconazole and ketoconazole were started, the rash had completely resolved. Nearly 8 months later (at the time this article was written), the rash had not recurred.

We report a unique case of T indotineae in a patient residing in California. Post hoc laboratory testing of dermatophyte isolates sent to the University of Texas reference laboratory identified terbinafine-resistant T indotineae specimens from the United States and Canada dating to 2017; clinical characteristics of patients from whom those isolates were obtained were unavailable.9

Trichophyton indotineae dermatophytosis typically is more extensive, inflamed, and pruritic, as well as likely more contagious, than tinea caused by other dermatophytes.5 Previously called Trichophyton mentagrophytes genotype VIII when first isolated in 2017, the pathogen was renamed T indotineae in 2020 after important genetic differences were discovered between it and other T mentagrophytes species.5 The emergence of T indotineae has been attributed to concomitant use of topical steroids and antifungals,5,10 inappropriate prescribing of antifungals,5 and nonadherence to antifungal treatment.5

Likely risk factors for T indotineae infection include suboptimal hygiene, overcrowded conditions, hot and humid environments, and tight-fitting synthetic clothing.4 Transmission from family members appears common,5 especially when fomites are shared.4 A case reported in Pennsylvania likely was acquired through sexual contact.7 Travel to South Asia has been associated with acquisition of T indotineae infection,3,5-7 though our patient and some others had not traveled there.3,8 It is not clear whether immunosuppression and diabetes mellitus are associated with T indotineae infection.4,5,8 Trichophyton indotineae also can affect animals,11 though zoonotic transmission has not been reported.4

Not all T indotineae isolates are resistant to one or more antifungals; furthermore, antifungal resistance in other dermatophyte species has been reported.5 Terbinafine resistance in T indotineae is conferred by mutations in the gene encoding squalene epoxidase, which helps synthesize ergosterol—a component of the cell membrane in fungi.2,4,5,12 Although clinical cut-points for MIC obtained by AFST are not well established, T indotineae MICs for terbinafine of 0.5 μg/mL or more correlate with resistance.9 Resistance to azoles has been linked to overexpression of transporter genes, which increase azole efflux from cells, as well as to mutations in the gene encoding lanosterol 14α demethylase.4,12,13

Potassium hydroxide preparations and fungal cultures cannot differentiate T indotineae from other dermatophytes that typically cause tinea.5,14 Histopathologic findings in our case were no different than those of non–T indotineae dermatophytes. Only molecular testing using PCR assays to sequence internal transcribed spacer genes can confirm T indotineae infection. However, PCR assays and AFST are not available in many US laboratories.5 Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry has shown promise in distinguishing T indotineae from other dermatophytes, though its clinical use is limited and it cannot assess terbinafine sensitivity.15,16 Clinicians in the United States who want to test specimens from cases suspicious for T indotineae infection should contact their local or state health department or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for assistance.3,5

Systemic treatment typically is necessary for T indotineae infection.5 Combinations of oral and topical azoles have been used, as well as topical ciclopirox, amorolfine (not available in the United States), and luliconazole.1,5,17-21

Itraconazole has emerged as the treatment of choice for T indotineae tinea, typically at 200 mg/d and often for courses of more than 3 months.5 Testing for serum itraconazole trough levels, as done for our patient, typically is not recommended. Clinicians should counsel patients to take itraconazole with high-fat foods and an acidic beverage to increase bioavailability.5 Potential adverse effects of itraconazole include heart failure and numerous drug-drug interactions.5,22 Patients with T indotineae dermatophytosis should avoid sharing personal belongings and having skin-to-skin contact of affected areas with others.4

Dermatologists who suspect T indotineae infection should work with public health agencies that can assist with testing and undertake infection surveillance, prevention, and control.5,23 Challenges to diagnosing and managing T indotineae infection include lack of awareness among dermatology providers, the need for specialized laboratory testing to confirm infection, lack of established clinical cut-points for MICs from AFST, the need for longer duration of treatment vs what is needed for typical tinea, and potential challenges with insurance coverage for testing and treatment. Empiric treatment with itraconazole should be considered when terbinafine-resistant dermatophytosis is suspected or when terbinafine-resistant T indotineae infection is confirmed.

Acknowledgments—Jeremy Gold, MD; Dallas J. Smith, PharmD; and Shawn Lockhart, PhD, all of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Mycotic Diseases Branch (Atlanta, Georgia), provided helpful comments to the authors in preparing the manuscript of this article.

- Uhrlaß S, Verma SB, Gräser Y, al. Trichophyton indotineae—an emerging pathogen causing recalcitrant dermatophytoses in India and worldwide—a multidimensional perspective. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8:757. doi:10.3390/jof8070757

- Jabet A, Brun S, Normand A-C, et al. Extensive dermatophytosis caused by terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton indotineae, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:229-233. doi:10.3201/eid2801.210883

- Caplan AS, Chaturvedi S, Zhu Y, et al. Notes from the field. First reported U.S. cases of tinea caused by Trichophyton indotineae—New York City, December 2021-March 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:536-537. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7219a4

- Jabet A, Normand A-C, Brun S, et al. Trichophyton indotineae, from epidemiology to therapeutic. J Mycol Med. 2023;33:101383. doi:10.1016/j.mycmed.2023.101383

- Hill RC, Caplan AS, Elewski B, et al. Expert panel review of skin and hair dermatophytoses in an era of antifungal resistance. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25:359-389. doi:10.1007/s40257-024-00848-1

- Caplan AS, Zakhem GA, Pomeranz MK. Trichophyton mentagrophytes internal transcribed spacer genotype VIII. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:1130. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.2645

- Spivack S, Gold JAW, Lockhart SR, et al. Potential sexual transmission of antifungal-resistant Trichophyton indotineae. Emerg Infect Dis. 2024;30:807-809. doi:10.3201/eid3004.240115

- Caplan AS, Todd GC, Zhu Y, et al. Clinical course, antifungal susceptibility, and genomic sequencing of Trichophyton indotineae. JAMA Dermatol. Published online May 15, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1126

- Cañete-Gibas CF, Mele J, Patterson HP, et al. Terbinafine-resistant dermatophytes and the presence of Trichophyton indotineae in North America. J Clin Microbiol. 2023;61:e0056223. doi:10.1128/jcm.00562-23

- Gupta AK, Venkataraman M, Hall DC, et al. The emergence of Trichophyton indotineae: implications for clinical practice. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:857-861.

- Oladzad V, Nasrollahi Omran A, Haghani I, et al. Multi-drug resistance Trichophyton indotineae in a stray dog. Res Vet Sci. 2024;166:105105. doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2023.105105

- Martinez-Rossi NM, Bitencourt TA, Peres NTA, et al. Dermatophyte resistance to antifungal drugs: mechanisms and prospectus. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1108. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01108

- Sacheli R, Hayette MP. Antifungal resistance in dermatophytes: genetic considerations, clinical presentations and alternative therapies. J Fungi (Basel). 2021;711:983. doi:10.3390/jof7110983

- Gupta AK, Cooper EA. Dermatophytosis (tinea) and other superficial fungal infections. In: Hospenthal DR, Rinaldi MG, eds. Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Mycoses. Humana Press; 2008:355-381.

- Normand A-C, Moreno-Sabater A, Jabet A, et al. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry online identification of Trichophyton indotineae using the MSI-2 application. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8:1103. doi:10.3390/jof8101103

- De Paepe R, Normand A-C, Uhrlaß S, et al. Resistance profile, terbinafine resistance screening and MALDI-TOF MS identification of the emerging pathogen Trichophyton indotineae. Mycopathologia. 2024;189:29. doi:10.1007/s11046-024-00835-4

- Rajagopalan M, Inamadar A, Mittal A, et al. Expert consensus on the management of dermatophytosis in India (ECTODERM India). BMC Dermatol. 2018;18:6. doi:10.1186/s12895-018-0073-1

- Verma SB, Panda S, Nenoff P, et al. The unprecedented epidemic-like scenario of dermatophytosis in India: III. Antifungal resistance and treatment options. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2021;87:468-482. doi:10.25259/IJDVL_303_20

- Shaw D, Singh S, Dogra S, et al. MIC and upper limit of wild-type distribution for 13 antifungal agents against a Trichophyton mentagrophytes–Trichophyton interdigitale complex of Indian origin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:E01964-19. doi:10.1128/AAC.01964-19

- Burmester A, Hipler U-C, Uhrlaß S, et al. Indian Trichophyton mentagrophytes squalene epoxidase erg1 double mutants show high proportion of combined fluconazole and terbinafine resistance. Mycoses. 2020;63:1175-1180. doi:10.1111/myc.13150

- Khurana A, Agarwal A, Agrawal D, et al. Effect of different itraconazole dosing regimens on cure rates, treatment duration, safety, and relapse rates in adult patients with tinea corporis/cruris: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:1269-1278. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2022.3745

- Itraconazole capsule. DailyMed [Internet]. Updated June 3, 2024. Accessed June 19, 2024. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/lookup.cfm?setid=2ab38a8a-3708-4b97-9f7f-8e554a15348d

- Bui TS, Katz KA. Resistant Trichophyton indotineae dermatophytosis—an emerging pandemic, now in the US. JAMA Dermatol. Published online May 15, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2024.1125

- Uhrlaß S, Verma SB, Gräser Y, al. Trichophyton indotineae—an emerging pathogen causing recalcitrant dermatophytoses in India and worldwide—a multidimensional perspective. J Fungi (Basel). 2022;8:757. doi:10.3390/jof8070757

- Jabet A, Brun S, Normand A-C, et al. Extensive dermatophytosis caused by terbinafine-resistant Trichophyton indotineae, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:229-233. doi:10.3201/eid2801.210883

- Caplan AS, Chaturvedi S, Zhu Y, et al. Notes from the field. First reported U.S. cases of tinea caused by Trichophyton indotineae—New York City, December 2021-March 2023. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2023;72:536-537. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7219a4

- Jabet A, Normand A-C, Brun S, et al. Trichophyton indotineae, from epidemiology to therapeutic. J Mycol Med. 2023;33:101383. doi:10.1016/j.mycmed.2023.101383

- Hill RC, Caplan AS, Elewski B, et al. Expert panel review of skin and hair dermatophytoses in an era of antifungal resistance. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2024;25:359-389. doi:10.1007/s40257-024-00848-1