User login

VIDEO: Tips for performing contained power morcellation

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag has advanced in the last several years in an effort to achieve safe tissue removal for minimally invasive procedures such as myomectomy, laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy, or total hysterectomy of a large uterus.

Tissue extraction using contained power morcellation has become favored over contained morcellation using a scalpel – not only because the latter approach is cumbersome but because of the risk of bag puncture and subsequent organ injury. Surgeons have experimented with various sizes and types of retrieval bags and with various techniques for contained power morcellation.

The PneumoLiner carries the same restrictions as do other laparoscopic power morcellation systems – namely that it should not be used in surgery in which the tissue to be morcellated is known or suspected to contain malignancy, and that it should not be used in women who are peri- or postmenopausal. Moreover, to further enhance safety, physicians must have successfully completed the FDA-required validated training program run by Advanced Surgical Concepts and Olympus in order to use the device.

The FDA reviewed the PneumoLiner through a regulatory process known as the de novo classification process. This regulatory process is for first of its kind, low- to moderate-risk medical devices. The PneumoLiner was tested in laboratory conditions to ensure that it could withstand stress force in excess of the normal forces of surgery, and was found to be impervious to substances similar in molecular size to tissues, cells, and body fluids. There could be no cellular migration or leakage.

As surgeons were advancing the idea of inflated bag morcellation, one promising adaptation was to puncture the inflated bag to place accessory ports. However, recent research has shown that contained morcellation involving intentional bag puncture with a trocar may result in tissue or fluid leakage.

Spillage was noted in 7 of 76 cases (9.2%) in a multicenter prospective cohort of women who underwent hysterectomy or myomectomy using a contained power morcellation technique that involved perforation of the containment bag with a balloon-tipped lateral trocar. Investigators had injected blue dye into the bag prior to morcellation and examined the abdomen and pelvis after removing the bag for signs of spillage of dye, fluid, or tissue. In all cases, the containment bags were intact (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;214[2]:257.e1-6).

The authors prematurely closed this study and recommended against this puncture technique. For complete containment, it appears to be important that we morcellate using a bag that has a single opening and is not punctured with accessory trocars.

The technique

The PneumoLiner comes loaded in an insertion tube for placement. It has a plunger to deploy the device and a retrieval lanyard that closes the bag around the specimen, enabling retrieval of the neck of the bag outside the abdomen.

Included with the PneumoLiner is a multi-instrument port that can be used during the laparoscopic procedure and then converted to the active port for morcellation. The port has an opening for the laparoscope (either a 5-mm 30-degree straight or a 5-mm articulating laparoscope) and an opening for the morcellator, as well as two small openings for insufflation and for smoke exhaustion.

Surgery may be performed using this single-port or a multiport laparoscopic or robotic approach. For morcellation, the approach converts to a single-site technique that involves only one entry point for all instruments and no perforation of the bag.

At the beginning of the procedure (or at the end of the case if preferred), a 25-mm incision is made in the umbilicus and the system’s port is inserted and trimmed. The port cap is placed, the abdomen is insufflated, and the laparoscope is inserted. If placed at the beginning of the case, this port can be used as a camera or accessory port.

Before deployment of the PneumoLiner, the uterus or target tissue is placed out of the way; I recommend the upper right quadrant. The PneumoLiner is then inserted with its directional tab pointing upward, and the system’s plunger is depressed while the sleeve is pulled back. In essence, the PneumoLiner is advanced while the sleeve is simultaneously withdrawn, laying it flat in the pelvis.

With an atraumatic grasper, the uterus is placed within the opening of the bag, and the bag is grasped at the collar and elevated up and around the specimen. When full containment of the specimen is visualized, the retrieval lanyard is withdrawn until an opening ring partially protrudes outside the port. All lateral trocars must have been withdrawn prior to inflation of the bag to prevent it from being damaged.

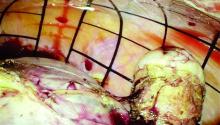

At this point, the port cap is removed and the PneumoLiner neck is withdrawn until a black grid pattern on the bag is visible. The surgeon should then ensure there are no twists in the bag before replacing the port cap and insufflating the bag to a pressure of 15 mm Hg.*

The bag must be correctly in place and fully insufflated before the laparoscope is inserted. The laparoscope must be inserted prior to the morcellator. When the morcellator is inserted, care must be taken to ensure that the morcellator probe is in place.

Once the morcellator is placed, the probe is withdrawn and a closed tenaculum is placed. With the closed tenaculum, the surgeon can manipulate tissue and gauge depth and bearings without inadvertently grabbing the bag. The black grid pattern on the bag assists with estimation of tissue fragment size; morcellation proceeds under direct vision until the tissue fragments are smaller than four printed grids.

Instrumentation is removed in a set order, with the morcellator first and the laparoscope last. The port cap is detached and the PneumoLiner is removed while allowing fumes to escape. The morcellator, camera, tenaculum, and port cap are considered contaminated at this point and should not re-enter the field.

Pearls for morcellation

- The single-site nature of the procedure can sometimes be challenging. If you’ve placed your laparoscope and are having difficulty locating the morcellator, bring your laparoscope and morcellator shaft in parallel to each other, and you’ll be able to better orient yourself.

- To enlarge your field of view after you’ve inflated the PneumoLiner and captured the tissue within the bag, level the patient a bit and move the tissue further away from the laparoscope.

- If the morcellator tube is limiting visualization of the tenaculum tip, slide the morcellator back while leaving the tenaculum in a fixed position.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Courtesy Dr. Tony Shibley and Olympus

Dr. Shibley is an ob.gyn. in private practice in the Minneapolis area. He receives royalties from Advanced Surgical Concepts and serves as a consultant for Olympus.

*Correction 3/8/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pneumoliner device in a photo caption. The pressure of the morcellation bag also was misstated.

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag has advanced in the last several years in an effort to achieve safe tissue removal for minimally invasive procedures such as myomectomy, laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy, or total hysterectomy of a large uterus.

Tissue extraction using contained power morcellation has become favored over contained morcellation using a scalpel – not only because the latter approach is cumbersome but because of the risk of bag puncture and subsequent organ injury. Surgeons have experimented with various sizes and types of retrieval bags and with various techniques for contained power morcellation.

The PneumoLiner carries the same restrictions as do other laparoscopic power morcellation systems – namely that it should not be used in surgery in which the tissue to be morcellated is known or suspected to contain malignancy, and that it should not be used in women who are peri- or postmenopausal. Moreover, to further enhance safety, physicians must have successfully completed the FDA-required validated training program run by Advanced Surgical Concepts and Olympus in order to use the device.

The FDA reviewed the PneumoLiner through a regulatory process known as the de novo classification process. This regulatory process is for first of its kind, low- to moderate-risk medical devices. The PneumoLiner was tested in laboratory conditions to ensure that it could withstand stress force in excess of the normal forces of surgery, and was found to be impervious to substances similar in molecular size to tissues, cells, and body fluids. There could be no cellular migration or leakage.

As surgeons were advancing the idea of inflated bag morcellation, one promising adaptation was to puncture the inflated bag to place accessory ports. However, recent research has shown that contained morcellation involving intentional bag puncture with a trocar may result in tissue or fluid leakage.

Spillage was noted in 7 of 76 cases (9.2%) in a multicenter prospective cohort of women who underwent hysterectomy or myomectomy using a contained power morcellation technique that involved perforation of the containment bag with a balloon-tipped lateral trocar. Investigators had injected blue dye into the bag prior to morcellation and examined the abdomen and pelvis after removing the bag for signs of spillage of dye, fluid, or tissue. In all cases, the containment bags were intact (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;214[2]:257.e1-6).

The authors prematurely closed this study and recommended against this puncture technique. For complete containment, it appears to be important that we morcellate using a bag that has a single opening and is not punctured with accessory trocars.

The technique

The PneumoLiner comes loaded in an insertion tube for placement. It has a plunger to deploy the device and a retrieval lanyard that closes the bag around the specimen, enabling retrieval of the neck of the bag outside the abdomen.

Included with the PneumoLiner is a multi-instrument port that can be used during the laparoscopic procedure and then converted to the active port for morcellation. The port has an opening for the laparoscope (either a 5-mm 30-degree straight or a 5-mm articulating laparoscope) and an opening for the morcellator, as well as two small openings for insufflation and for smoke exhaustion.

Surgery may be performed using this single-port or a multiport laparoscopic or robotic approach. For morcellation, the approach converts to a single-site technique that involves only one entry point for all instruments and no perforation of the bag.

At the beginning of the procedure (or at the end of the case if preferred), a 25-mm incision is made in the umbilicus and the system’s port is inserted and trimmed. The port cap is placed, the abdomen is insufflated, and the laparoscope is inserted. If placed at the beginning of the case, this port can be used as a camera or accessory port.

Before deployment of the PneumoLiner, the uterus or target tissue is placed out of the way; I recommend the upper right quadrant. The PneumoLiner is then inserted with its directional tab pointing upward, and the system’s plunger is depressed while the sleeve is pulled back. In essence, the PneumoLiner is advanced while the sleeve is simultaneously withdrawn, laying it flat in the pelvis.

With an atraumatic grasper, the uterus is placed within the opening of the bag, and the bag is grasped at the collar and elevated up and around the specimen. When full containment of the specimen is visualized, the retrieval lanyard is withdrawn until an opening ring partially protrudes outside the port. All lateral trocars must have been withdrawn prior to inflation of the bag to prevent it from being damaged.

At this point, the port cap is removed and the PneumoLiner neck is withdrawn until a black grid pattern on the bag is visible. The surgeon should then ensure there are no twists in the bag before replacing the port cap and insufflating the bag to a pressure of 15 mm Hg.*

The bag must be correctly in place and fully insufflated before the laparoscope is inserted. The laparoscope must be inserted prior to the morcellator. When the morcellator is inserted, care must be taken to ensure that the morcellator probe is in place.

Once the morcellator is placed, the probe is withdrawn and a closed tenaculum is placed. With the closed tenaculum, the surgeon can manipulate tissue and gauge depth and bearings without inadvertently grabbing the bag. The black grid pattern on the bag assists with estimation of tissue fragment size; morcellation proceeds under direct vision until the tissue fragments are smaller than four printed grids.

Instrumentation is removed in a set order, with the morcellator first and the laparoscope last. The port cap is detached and the PneumoLiner is removed while allowing fumes to escape. The morcellator, camera, tenaculum, and port cap are considered contaminated at this point and should not re-enter the field.

Pearls for morcellation

- The single-site nature of the procedure can sometimes be challenging. If you’ve placed your laparoscope and are having difficulty locating the morcellator, bring your laparoscope and morcellator shaft in parallel to each other, and you’ll be able to better orient yourself.

- To enlarge your field of view after you’ve inflated the PneumoLiner and captured the tissue within the bag, level the patient a bit and move the tissue further away from the laparoscope.

- If the morcellator tube is limiting visualization of the tenaculum tip, slide the morcellator back while leaving the tenaculum in a fixed position.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Courtesy Dr. Tony Shibley and Olympus

Dr. Shibley is an ob.gyn. in private practice in the Minneapolis area. He receives royalties from Advanced Surgical Concepts and serves as a consultant for Olympus.

*Correction 3/8/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pneumoliner device in a photo caption. The pressure of the morcellation bag also was misstated.

Experience with electromechanical power morcellation in a bag has advanced in the last several years in an effort to achieve safe tissue removal for minimally invasive procedures such as myomectomy, laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy, or total hysterectomy of a large uterus.

Tissue extraction using contained power morcellation has become favored over contained morcellation using a scalpel – not only because the latter approach is cumbersome but because of the risk of bag puncture and subsequent organ injury. Surgeons have experimented with various sizes and types of retrieval bags and with various techniques for contained power morcellation.

The PneumoLiner carries the same restrictions as do other laparoscopic power morcellation systems – namely that it should not be used in surgery in which the tissue to be morcellated is known or suspected to contain malignancy, and that it should not be used in women who are peri- or postmenopausal. Moreover, to further enhance safety, physicians must have successfully completed the FDA-required validated training program run by Advanced Surgical Concepts and Olympus in order to use the device.

The FDA reviewed the PneumoLiner through a regulatory process known as the de novo classification process. This regulatory process is for first of its kind, low- to moderate-risk medical devices. The PneumoLiner was tested in laboratory conditions to ensure that it could withstand stress force in excess of the normal forces of surgery, and was found to be impervious to substances similar in molecular size to tissues, cells, and body fluids. There could be no cellular migration or leakage.

As surgeons were advancing the idea of inflated bag morcellation, one promising adaptation was to puncture the inflated bag to place accessory ports. However, recent research has shown that contained morcellation involving intentional bag puncture with a trocar may result in tissue or fluid leakage.

Spillage was noted in 7 of 76 cases (9.2%) in a multicenter prospective cohort of women who underwent hysterectomy or myomectomy using a contained power morcellation technique that involved perforation of the containment bag with a balloon-tipped lateral trocar. Investigators had injected blue dye into the bag prior to morcellation and examined the abdomen and pelvis after removing the bag for signs of spillage of dye, fluid, or tissue. In all cases, the containment bags were intact (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Feb;214[2]:257.e1-6).

The authors prematurely closed this study and recommended against this puncture technique. For complete containment, it appears to be important that we morcellate using a bag that has a single opening and is not punctured with accessory trocars.

The technique

The PneumoLiner comes loaded in an insertion tube for placement. It has a plunger to deploy the device and a retrieval lanyard that closes the bag around the specimen, enabling retrieval of the neck of the bag outside the abdomen.

Included with the PneumoLiner is a multi-instrument port that can be used during the laparoscopic procedure and then converted to the active port for morcellation. The port has an opening for the laparoscope (either a 5-mm 30-degree straight or a 5-mm articulating laparoscope) and an opening for the morcellator, as well as two small openings for insufflation and for smoke exhaustion.

Surgery may be performed using this single-port or a multiport laparoscopic or robotic approach. For morcellation, the approach converts to a single-site technique that involves only one entry point for all instruments and no perforation of the bag.

At the beginning of the procedure (or at the end of the case if preferred), a 25-mm incision is made in the umbilicus and the system’s port is inserted and trimmed. The port cap is placed, the abdomen is insufflated, and the laparoscope is inserted. If placed at the beginning of the case, this port can be used as a camera or accessory port.

Before deployment of the PneumoLiner, the uterus or target tissue is placed out of the way; I recommend the upper right quadrant. The PneumoLiner is then inserted with its directional tab pointing upward, and the system’s plunger is depressed while the sleeve is pulled back. In essence, the PneumoLiner is advanced while the sleeve is simultaneously withdrawn, laying it flat in the pelvis.

With an atraumatic grasper, the uterus is placed within the opening of the bag, and the bag is grasped at the collar and elevated up and around the specimen. When full containment of the specimen is visualized, the retrieval lanyard is withdrawn until an opening ring partially protrudes outside the port. All lateral trocars must have been withdrawn prior to inflation of the bag to prevent it from being damaged.

At this point, the port cap is removed and the PneumoLiner neck is withdrawn until a black grid pattern on the bag is visible. The surgeon should then ensure there are no twists in the bag before replacing the port cap and insufflating the bag to a pressure of 15 mm Hg.*

The bag must be correctly in place and fully insufflated before the laparoscope is inserted. The laparoscope must be inserted prior to the morcellator. When the morcellator is inserted, care must be taken to ensure that the morcellator probe is in place.

Once the morcellator is placed, the probe is withdrawn and a closed tenaculum is placed. With the closed tenaculum, the surgeon can manipulate tissue and gauge depth and bearings without inadvertently grabbing the bag. The black grid pattern on the bag assists with estimation of tissue fragment size; morcellation proceeds under direct vision until the tissue fragments are smaller than four printed grids.

Instrumentation is removed in a set order, with the morcellator first and the laparoscope last. The port cap is detached and the PneumoLiner is removed while allowing fumes to escape. The morcellator, camera, tenaculum, and port cap are considered contaminated at this point and should not re-enter the field.

Pearls for morcellation

- The single-site nature of the procedure can sometimes be challenging. If you’ve placed your laparoscope and are having difficulty locating the morcellator, bring your laparoscope and morcellator shaft in parallel to each other, and you’ll be able to better orient yourself.

- To enlarge your field of view after you’ve inflated the PneumoLiner and captured the tissue within the bag, level the patient a bit and move the tissue further away from the laparoscope.

- If the morcellator tube is limiting visualization of the tenaculum tip, slide the morcellator back while leaving the tenaculum in a fixed position.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Courtesy Dr. Tony Shibley and Olympus

Dr. Shibley is an ob.gyn. in private practice in the Minneapolis area. He receives royalties from Advanced Surgical Concepts and serves as a consultant for Olympus.

*Correction 3/8/17: An earlier version of this article misstated the name of the Pneumoliner device in a photo caption. The pressure of the morcellation bag also was misstated.

Safety techniques regarding morcellation

Power morcellation within an insufflated bag

By Tony Shibley, M.D.

Morcellating safely in laparoscopic hysterectomy or myomectomy involves not only the use of a bag, but also the creation of an artificial pneumoperitoneum inside the bag. Inflation of the bag allows us to create a safe and completely contained working environment in the abdomen, with good visualization and adequate working space.

In the past, specimen containment bags were used for morcellation, but the bags would adhere to tissue and would be easily cut or would tear or rupture. Without proper space and visualization, surgeons could not break tissue into smaller fragments without endangering the bag or the structures behind the bag. We were safely and precisely disconnecting tissue in our surgeries, but falling short with tissue removal. There were calls for more durable bags, but the problems of visualization and safe distance were not addressed. Eventually, the goal of morcellating within a bag was largely abandoned in favor of open power morcellation.

I stopped performing open power morcellation about 2 years ago and developed a new approach to enclosed morcellation. By creating an artificial pneumoperitoneum in a bag, a good working space is developed within it. This meets the needs of containment while significantly lowering the risk of tissue dissemination and also reducing the risk of bowel injury, vascular injury, and other types of morcellator-related mechanical injuries. This approach to morcellation is safer on all fronts.

My method of enclosed morcellation has been utilized in both single-port and multiport hysterectomy (total and supracervical) and myomectomy performed with either traditional laparoscopy or the robotic platform.

The morcellation process is begun after surgery is complete except for tissue removal, and the patient is hemostatic. The specimen has been placed in a location where it can be easily retrieved; I prefer the right upper quadrant.

In a single-port approach, the bag is inserted into the abdomen through an open single-port cannula at the umbilicus. I use a Steri-Drape Isolation Bag (3M), 50 cm by 50 cm, with drawstrings. (See Figure 1.) Standing across from my assistant, I tightly fan-fold the bag and wring it to purge it of air. Using an atraumatic grasper, I position the bag linearly with the opening up; it is inserted into the pelvis first, with the superior end guided upward into the mid- and then upper-abdomen.

After the bag is placed, the cannula is recapped with the multiport cap. I use the Olympus TriPort 15 (Advanced Surgical Concepts), and the abdomen is reinsufflated. A camera is inserted into one of the 5-mm ports. I use the Olympus 5-mm articulating laparoscope.

Through the other 5-mm port, I maneuver the bag to form a pocket opening by pushing the upper corners of the bag against the respective abdominal sidewalls, and the body of the bag into the pelvis. I then elevate the specimen and, with a rotational movement, I guide the specimen along the right abdominal sidewall and into the pocket opening. I then elevate the sides of the bag and ensure that the specimen is well contained. (See Figure 2.)

The drawstrings are then brought up into the port hub. The cap is removed, and the opening of the bag is pulled up through the port and out approximately 15-20 cm, as symmetrically as possible.

The port cap is then replaced within the exteriorized neck of the bag, and the bag is insufflated with traditional laparoscopic pressure of 15-18 mm, creating an artificial pneumoperitoneum. (See Figure 3.) The camera is reinserted, followed by the morcellator, into the 15-mm port of the single-site tri-port. The morcellator must be lubricated so it does not catch the bag on the way in. Morcellation is carried out under direct vision.

After the morcellation process is complete, the morcellator is removed, followed by the camera and the tri-port cap. The bag is desufflated and removed through the open cannula, and the abdomen is closed as usual.

In a multiport approach, the umbilical incision is extended to 15 mm after completion of the hysterectomy or myomectomy. The bag is inserted and placed in a manner similar to the single-port approach, except that the lateral ports may be utilized to further position the bag once it is placed about halfway in. The bag is similarly opened, the specimen contained, and the neck of the bag exteriorized. A 15-mm port is similarly lubricated and placed inside the neck of the bag and through the umbilical incision.

As the bag is insufflated, the lateral ports are backed slightly out so that they're flush with the abdominal wall, and the trocars are opened to allow the release of any residual gas in the abdomen. The laparoscope is then placed into the 15-mm umbilical trocar.

Visualization will ultimately occur from another site, however. One of the lateral 5-mm trocars is advanced at a right angle to the insufflated bag, and an introducer is placed to puncture the bag. I recommend using a blunt plastic trocar; a balloon-tip trocar also can be used. Contrary to what one might think, the bag will not leak any gas. The laparoscope is now transferred to this 5-mm lateral port, and the umbilical port is removed. A lubricated morcellator is inserted directly through the umbilical incision, and morcellation is performed under direct visualization from the side port.

These techniques for single-port or multiport enclosed power morcellation have been shown to be reproducible and successful – with all bags intact and specimens contained – in a multicenter analysis that is being prepared for publication. The largest uterus in the study was 1,481 g.

To make the approach less cumbersome, I have designed a morcellation device consisting of a specialized bag that will open automatically and assist in capturing the specimen. The device, which has closure tabs and a retrieval lanyard, has been developed with the input of other minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons and the design and engineering expertise of Advanced Surgical Concepts. It will be manufactured by the company pending Food and Drug Administration approval.

Concealed power morcellation: Our take

By Bernard Taylor, M.D.

The approach to the use of power morcellation within a bag in my practice was not specifically driven by the desire to prevent the dispersion of malignant leiomyosarcoma – an issue that is now front and center and indeed, is important – but by a broader desire to perform as complete an extraction as possible.

For years we have used isolation bags to conceal and contain small uteri, ovaries, and specimens that we debulk using a scalpel and remove through a small umbilical incision. However, this approach is cumbersome for removing larger uteri. Consequently, over the past year we refined our methods for performing power morcellation within a bag.

This procedure can be performed after traditional laparoscopy or robotic-assisted hysterectomy or myomectomy to extract the specimen from the abdomen. A surgical tissue bag is placed into the abdomen and is insufflated within the abdomen. Morcellation is carried out within the concealed "pseudopneumoperitoneum," and the bag is exteriorized from the abdomen, typically through the umbilical incision.

The majority of my procedures utilize a multiport approach due to the nature of my practice as a urogynecologist. After hysterectomy or myomectomy, the specimen is placed in the upper abdomen. The cuff is closed, other procedures are completed in the usual fashion, and hemostasis is reassured. In robotic procedures, we undock the robot prior to morcellation. The umbilical port is removed, and the bag is placed into the abdomen with a ring forceps or atraumatic forceps without teeth. The umbilical port is then replaced to reestablish the pneumoperitoneum for visualization.

For larger uterine specimens, I use an Isodrape isolation bag (Microtek Medical). This 18 x 18 inch bag with a drawstring opening easily accommodates uteri larger than 1,000 g. The bag is placed into the pelvis with the open end at the pelvic brim and is opened wide. I use the term "open from iliac to iliac and sacrum to bladder." Once the bag is positioned, the specimen is grasped; the patient is slowly taken out of the Trendelenburg position to allow for gravity to assist in the placement of the specimen into the bag.

The drawstrings are then grasped and taken out of the umbilical trocar with simultaneous removal of the umbilical port. At this time, the open end of the bag is exteriorized, and the specimen technically is extraperitoneal and "concealed."

To insufflate the bag at this point and create the "pseudopneumoperitoneum," a 15-mm port is lubricated and placed through the opening in the bag. The bag is then insufflated to the usual pressure (15 mm Hg). The accessory ports are opened at this time to allow for the abdominal pressure to fall and for the bag to expand and fill the abdominal cavity.

To enable visualization throughout the morcellation procedure, I use one of the previously placed lower abdomen lateral ports to place a 5-mm camera. The camera is placed after a 5-mm balloon tip trocar is introduced and advanced to perforate the bag. The balloon tip is insufflated in the usual fashion, securing the bag against the abdominal wall and preventing a gas leak.

Alternatively, I have also used a SILSport (Covidien) at the umbilicus in cases when there is a leak at the umbilical incision and the 15-mm port does not seal properly. While use of a single-port technique has been shown to be feasible for both visualization and morcellation, it can present challenges in complex cases with a larger uterus or multiple fibroids.

Either way, morcellation can take place within the concealed "pseudo-peritoneal" cavity, with the morcellator lubricated and placed either through the umbilical incision or through the Tri-Port. After morcellation is complete, the bag containing the smaller tissue fragments and blood is simply removed through the umbilicus, and closure of the abdomen is completed in the usual fashion.

I also have adopted a simplified approach to remove the smaller uteri with supracervical hysterectomy and sacral colpopexy performed laparoscopically. Despite preoperative screening with endometrial biopsy and pelvic ultrasound, several of my patients in the past have been diagnosed with either early ovarian or endometrial neoplasias on final pathology. After completing the procedure, I place the small menopausal senile uterus and adnexa into a 15-mm endoscopic bag. The bag is brought through the umbilical port, and the specimen is removed via morcellation with a scalpel or scissors.

Surgeons have asked about additional time needed to place the bag and position the specimen. Technically, specimen placement is a learned skill; once one is proficient, the case times are not any different. In fact, cases may be shorter because of the time saved by not having to retrieve uterine fragments from the abdomen and pelvis.

Theoretically, the procedure addresses concerns associated with tissue fragmentation and dissemination within the abdominal cavity. To date, there are no trials showing prevention of cancer upstaging or benign conditions such as leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata or endometriosis.

Enclosed vaginal morcellation for enlarged uteri

By Ceana H. Nezhat, M.D.

Removal of large uteri via minimally invasive surgery poses challenges to gynecologic surgeons. Limitations on the use of intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation are a step forward in terms of protecting patients from undue harm, but we also must acknowledge that minimally invasive surgery has been shown to be superior to laparotomy in the majority of cases.

While safer ways to extract large specimens without risk of spreading both benign and malignant tissue are being studied and developed, gynecologic surgeons need to find alternative minimally invasive approaches for removing large specimens.

Minimally invasive approaches to extirpate uteri and myomas have been described prior to the advent of electromechanical morcellation. A natural orifice such as the vagina for gynecologic procedures is a clear choice for removing specimens. Laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy is a combination of laparoscopy and minilaparotomy for tissue extraction (JSLS 2001;5:299-303). Another alternative is extracting myoma and other tissues through a posterior colpotomy. Rates of dyspareunia and adhesions in the cul-de-sac after tissue extraction through a colpotomy are low (J. Reprod. Med. 1993;38:534-6).

Vaginal hysterectomy was chronicled and performed by the Greek physician Soranus of Ephesus in 120 A.D. (Acta Chir. Iugosl. 2011:58:9-14), and it is still the preferred route of hysterectomy when it can be performed. Large uteri can be transvaginally morcellated and vaginally extracted; however, this technique still poses the risk, although low, of spilling fragments of uterine tissue in the abdomen.

By combining total laparoscopic hysterectomy and vaginal morcellation of enlarged uteri within an enclosed specimen bag, the risk of spilling uterine fragments is reduced, in addition to avoiding potential visceral and vascular complications associated with intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation.

Enclosed vaginal morcellation is the technique of placing the enlarged hysterectomy specimen in an endoscopic specimen retrieval bag and then transvaginally morcellating the tissue.

In the development of this technique, I have experimented with different endoscopic sacs and retractors. In my experience, the optimal laparoscopic bag is the LapSac Surgical Tissue Pouch (Cook Medical). This endoscopic, one-time use, specimen retrieval bag is flexible, durable nylon with an integral polyurethane inner coating and polypropylene drawstring (Figure 4). The bag comes in four sizes, the largest (size 8 x 10 inch, volume 1,500 mL) of which I used to assist in removing the 18-week size uterus in the accompanying video.

The other key piece of equipment for vaginal extraction of large uteri is a transvaginally-placed wound retractor. As I have previously described, the self-retaining retractor provides optimal exposure in a narrow field and minimizes trauma to surrounding tissue (J. Minim. Inv. Gynecol. 2009:16:616-7). Two wound retractors are suitable for this surgical technique: the Alexis Wound Protector/Retractor (Applied Medical) (Figure 5) and the Mobius Elastic Abdominal Retractor (Cooper Surgical) (Figure 6).

After complete laparoscopic detachment of the uterus and cervix (and adnexa), the wound retractor is placed transvaginally. One semirigid ring is pushed superiorly through the vagina and into the peritoneal cavity, where is it placed in the cul-de-sac. In this manner, a uniform, circumferential orifice is created. In narrower vaginal vaults, the ring can be compressed between the thumb and index finger to reduce its diameter and thus be introduced into the peritoneal cavity atraumatically. With the small-size retraction systems, an orifice of 2.5 to 6 cm diameter can be created.

The LapSac is folded and then inserted with ring forceps transvaginally through the wound retractor. (See Figure 7.) The bag is unfolded intraperitoneally using the integral tabs to demarcate the edges of the bag. The bag should be unfolded in the pelvis with the opening of the bag cephalad. The fundus of the hysterectomy specimen is grasped with a tenaculum and placed inside the bag. (See Figure 8.)

It is an important technical point to grab the fundus or the heaviest point of the specimen to allow weight and gravity to facilitate placing the specimen securely in the bag. If the cervix or a lighter part of the specimen is grasped, placement in the bag is more difficult and the specimen will likely slip out of the bag.

Once the entire hysterectomy specimen is in the LapSac, the bag is cinched by grasping the blue drawstrings. The opening of the bag is pulled through the vagina. The opening of the bag is externalized and the edges are attached with Allis clamps to the external edge of the wound retractor. The specimen (typically the cervix first) is grasped with a tenaculum and vaginally morcellated and cored with a scalpel (Figure 9).

Metal vaginal retractors are placed within the bag to protect against sharp injury during morcellation. I prefer to amputate the cervix and adnexa separately and en bloc to preserve as much original architecture as possible so the pathologists can properly orient and examine the tissue. After completion of the morcellation, the wound retractor is removed, the cuff closed, and the procedure completed per surgeon preference.

Dr. Shibley has been in full-time practice with Ob.Gyn. Specialists, Fairview Health Services in the Minneapolis area (Edina), for 20 years. He reported that he has a financial interest in the artificial pneumoperitoneum device under development, and that he is a consultant for Olympus.

Dr. Taylor is a urogynecologist who is a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgeon practicing at the Carolinas Medical Center–Advanced Surgical Specialties for Women in Charlotte, N.C. He reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Dr. Nezhat is the current president of the AAGL, adjunct professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University and program director of minimally invasive surgery at Northside Hospital, both in Atlanta, and adjunct clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reported that he is a consultant for Karl Storz Endoscopy.

Videos of these experts' individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation within the confines of a bag, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, director of the Center for Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, can be viewed at the SurgeryU website.

Power morcellation within an insufflated bag

By Tony Shibley, M.D.

Morcellating safely in laparoscopic hysterectomy or myomectomy involves not only the use of a bag, but also the creation of an artificial pneumoperitoneum inside the bag. Inflation of the bag allows us to create a safe and completely contained working environment in the abdomen, with good visualization and adequate working space.

In the past, specimen containment bags were used for morcellation, but the bags would adhere to tissue and would be easily cut or would tear or rupture. Without proper space and visualization, surgeons could not break tissue into smaller fragments without endangering the bag or the structures behind the bag. We were safely and precisely disconnecting tissue in our surgeries, but falling short with tissue removal. There were calls for more durable bags, but the problems of visualization and safe distance were not addressed. Eventually, the goal of morcellating within a bag was largely abandoned in favor of open power morcellation.

I stopped performing open power morcellation about 2 years ago and developed a new approach to enclosed morcellation. By creating an artificial pneumoperitoneum in a bag, a good working space is developed within it. This meets the needs of containment while significantly lowering the risk of tissue dissemination and also reducing the risk of bowel injury, vascular injury, and other types of morcellator-related mechanical injuries. This approach to morcellation is safer on all fronts.

My method of enclosed morcellation has been utilized in both single-port and multiport hysterectomy (total and supracervical) and myomectomy performed with either traditional laparoscopy or the robotic platform.

The morcellation process is begun after surgery is complete except for tissue removal, and the patient is hemostatic. The specimen has been placed in a location where it can be easily retrieved; I prefer the right upper quadrant.

In a single-port approach, the bag is inserted into the abdomen through an open single-port cannula at the umbilicus. I use a Steri-Drape Isolation Bag (3M), 50 cm by 50 cm, with drawstrings. (See Figure 1.) Standing across from my assistant, I tightly fan-fold the bag and wring it to purge it of air. Using an atraumatic grasper, I position the bag linearly with the opening up; it is inserted into the pelvis first, with the superior end guided upward into the mid- and then upper-abdomen.

After the bag is placed, the cannula is recapped with the multiport cap. I use the Olympus TriPort 15 (Advanced Surgical Concepts), and the abdomen is reinsufflated. A camera is inserted into one of the 5-mm ports. I use the Olympus 5-mm articulating laparoscope.

Through the other 5-mm port, I maneuver the bag to form a pocket opening by pushing the upper corners of the bag against the respective abdominal sidewalls, and the body of the bag into the pelvis. I then elevate the specimen and, with a rotational movement, I guide the specimen along the right abdominal sidewall and into the pocket opening. I then elevate the sides of the bag and ensure that the specimen is well contained. (See Figure 2.)

The drawstrings are then brought up into the port hub. The cap is removed, and the opening of the bag is pulled up through the port and out approximately 15-20 cm, as symmetrically as possible.

The port cap is then replaced within the exteriorized neck of the bag, and the bag is insufflated with traditional laparoscopic pressure of 15-18 mm, creating an artificial pneumoperitoneum. (See Figure 3.) The camera is reinserted, followed by the morcellator, into the 15-mm port of the single-site tri-port. The morcellator must be lubricated so it does not catch the bag on the way in. Morcellation is carried out under direct vision.

After the morcellation process is complete, the morcellator is removed, followed by the camera and the tri-port cap. The bag is desufflated and removed through the open cannula, and the abdomen is closed as usual.

In a multiport approach, the umbilical incision is extended to 15 mm after completion of the hysterectomy or myomectomy. The bag is inserted and placed in a manner similar to the single-port approach, except that the lateral ports may be utilized to further position the bag once it is placed about halfway in. The bag is similarly opened, the specimen contained, and the neck of the bag exteriorized. A 15-mm port is similarly lubricated and placed inside the neck of the bag and through the umbilical incision.

As the bag is insufflated, the lateral ports are backed slightly out so that they're flush with the abdominal wall, and the trocars are opened to allow the release of any residual gas in the abdomen. The laparoscope is then placed into the 15-mm umbilical trocar.

Visualization will ultimately occur from another site, however. One of the lateral 5-mm trocars is advanced at a right angle to the insufflated bag, and an introducer is placed to puncture the bag. I recommend using a blunt plastic trocar; a balloon-tip trocar also can be used. Contrary to what one might think, the bag will not leak any gas. The laparoscope is now transferred to this 5-mm lateral port, and the umbilical port is removed. A lubricated morcellator is inserted directly through the umbilical incision, and morcellation is performed under direct visualization from the side port.

These techniques for single-port or multiport enclosed power morcellation have been shown to be reproducible and successful – with all bags intact and specimens contained – in a multicenter analysis that is being prepared for publication. The largest uterus in the study was 1,481 g.

To make the approach less cumbersome, I have designed a morcellation device consisting of a specialized bag that will open automatically and assist in capturing the specimen. The device, which has closure tabs and a retrieval lanyard, has been developed with the input of other minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons and the design and engineering expertise of Advanced Surgical Concepts. It will be manufactured by the company pending Food and Drug Administration approval.

Concealed power morcellation: Our take

By Bernard Taylor, M.D.

The approach to the use of power morcellation within a bag in my practice was not specifically driven by the desire to prevent the dispersion of malignant leiomyosarcoma – an issue that is now front and center and indeed, is important – but by a broader desire to perform as complete an extraction as possible.

For years we have used isolation bags to conceal and contain small uteri, ovaries, and specimens that we debulk using a scalpel and remove through a small umbilical incision. However, this approach is cumbersome for removing larger uteri. Consequently, over the past year we refined our methods for performing power morcellation within a bag.

This procedure can be performed after traditional laparoscopy or robotic-assisted hysterectomy or myomectomy to extract the specimen from the abdomen. A surgical tissue bag is placed into the abdomen and is insufflated within the abdomen. Morcellation is carried out within the concealed "pseudopneumoperitoneum," and the bag is exteriorized from the abdomen, typically through the umbilical incision.

The majority of my procedures utilize a multiport approach due to the nature of my practice as a urogynecologist. After hysterectomy or myomectomy, the specimen is placed in the upper abdomen. The cuff is closed, other procedures are completed in the usual fashion, and hemostasis is reassured. In robotic procedures, we undock the robot prior to morcellation. The umbilical port is removed, and the bag is placed into the abdomen with a ring forceps or atraumatic forceps without teeth. The umbilical port is then replaced to reestablish the pneumoperitoneum for visualization.

For larger uterine specimens, I use an Isodrape isolation bag (Microtek Medical). This 18 x 18 inch bag with a drawstring opening easily accommodates uteri larger than 1,000 g. The bag is placed into the pelvis with the open end at the pelvic brim and is opened wide. I use the term "open from iliac to iliac and sacrum to bladder." Once the bag is positioned, the specimen is grasped; the patient is slowly taken out of the Trendelenburg position to allow for gravity to assist in the placement of the specimen into the bag.

The drawstrings are then grasped and taken out of the umbilical trocar with simultaneous removal of the umbilical port. At this time, the open end of the bag is exteriorized, and the specimen technically is extraperitoneal and "concealed."

To insufflate the bag at this point and create the "pseudopneumoperitoneum," a 15-mm port is lubricated and placed through the opening in the bag. The bag is then insufflated to the usual pressure (15 mm Hg). The accessory ports are opened at this time to allow for the abdominal pressure to fall and for the bag to expand and fill the abdominal cavity.

To enable visualization throughout the morcellation procedure, I use one of the previously placed lower abdomen lateral ports to place a 5-mm camera. The camera is placed after a 5-mm balloon tip trocar is introduced and advanced to perforate the bag. The balloon tip is insufflated in the usual fashion, securing the bag against the abdominal wall and preventing a gas leak.

Alternatively, I have also used a SILSport (Covidien) at the umbilicus in cases when there is a leak at the umbilical incision and the 15-mm port does not seal properly. While use of a single-port technique has been shown to be feasible for both visualization and morcellation, it can present challenges in complex cases with a larger uterus or multiple fibroids.

Either way, morcellation can take place within the concealed "pseudo-peritoneal" cavity, with the morcellator lubricated and placed either through the umbilical incision or through the Tri-Port. After morcellation is complete, the bag containing the smaller tissue fragments and blood is simply removed through the umbilicus, and closure of the abdomen is completed in the usual fashion.

I also have adopted a simplified approach to remove the smaller uteri with supracervical hysterectomy and sacral colpopexy performed laparoscopically. Despite preoperative screening with endometrial biopsy and pelvic ultrasound, several of my patients in the past have been diagnosed with either early ovarian or endometrial neoplasias on final pathology. After completing the procedure, I place the small menopausal senile uterus and adnexa into a 15-mm endoscopic bag. The bag is brought through the umbilical port, and the specimen is removed via morcellation with a scalpel or scissors.

Surgeons have asked about additional time needed to place the bag and position the specimen. Technically, specimen placement is a learned skill; once one is proficient, the case times are not any different. In fact, cases may be shorter because of the time saved by not having to retrieve uterine fragments from the abdomen and pelvis.

Theoretically, the procedure addresses concerns associated with tissue fragmentation and dissemination within the abdominal cavity. To date, there are no trials showing prevention of cancer upstaging or benign conditions such as leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata or endometriosis.

Enclosed vaginal morcellation for enlarged uteri

By Ceana H. Nezhat, M.D.

Removal of large uteri via minimally invasive surgery poses challenges to gynecologic surgeons. Limitations on the use of intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation are a step forward in terms of protecting patients from undue harm, but we also must acknowledge that minimally invasive surgery has been shown to be superior to laparotomy in the majority of cases.

While safer ways to extract large specimens without risk of spreading both benign and malignant tissue are being studied and developed, gynecologic surgeons need to find alternative minimally invasive approaches for removing large specimens.

Minimally invasive approaches to extirpate uteri and myomas have been described prior to the advent of electromechanical morcellation. A natural orifice such as the vagina for gynecologic procedures is a clear choice for removing specimens. Laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy is a combination of laparoscopy and minilaparotomy for tissue extraction (JSLS 2001;5:299-303). Another alternative is extracting myoma and other tissues through a posterior colpotomy. Rates of dyspareunia and adhesions in the cul-de-sac after tissue extraction through a colpotomy are low (J. Reprod. Med. 1993;38:534-6).

Vaginal hysterectomy was chronicled and performed by the Greek physician Soranus of Ephesus in 120 A.D. (Acta Chir. Iugosl. 2011:58:9-14), and it is still the preferred route of hysterectomy when it can be performed. Large uteri can be transvaginally morcellated and vaginally extracted; however, this technique still poses the risk, although low, of spilling fragments of uterine tissue in the abdomen.

By combining total laparoscopic hysterectomy and vaginal morcellation of enlarged uteri within an enclosed specimen bag, the risk of spilling uterine fragments is reduced, in addition to avoiding potential visceral and vascular complications associated with intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation.

Enclosed vaginal morcellation is the technique of placing the enlarged hysterectomy specimen in an endoscopic specimen retrieval bag and then transvaginally morcellating the tissue.

In the development of this technique, I have experimented with different endoscopic sacs and retractors. In my experience, the optimal laparoscopic bag is the LapSac Surgical Tissue Pouch (Cook Medical). This endoscopic, one-time use, specimen retrieval bag is flexible, durable nylon with an integral polyurethane inner coating and polypropylene drawstring (Figure 4). The bag comes in four sizes, the largest (size 8 x 10 inch, volume 1,500 mL) of which I used to assist in removing the 18-week size uterus in the accompanying video.

The other key piece of equipment for vaginal extraction of large uteri is a transvaginally-placed wound retractor. As I have previously described, the self-retaining retractor provides optimal exposure in a narrow field and minimizes trauma to surrounding tissue (J. Minim. Inv. Gynecol. 2009:16:616-7). Two wound retractors are suitable for this surgical technique: the Alexis Wound Protector/Retractor (Applied Medical) (Figure 5) and the Mobius Elastic Abdominal Retractor (Cooper Surgical) (Figure 6).

After complete laparoscopic detachment of the uterus and cervix (and adnexa), the wound retractor is placed transvaginally. One semirigid ring is pushed superiorly through the vagina and into the peritoneal cavity, where is it placed in the cul-de-sac. In this manner, a uniform, circumferential orifice is created. In narrower vaginal vaults, the ring can be compressed between the thumb and index finger to reduce its diameter and thus be introduced into the peritoneal cavity atraumatically. With the small-size retraction systems, an orifice of 2.5 to 6 cm diameter can be created.

The LapSac is folded and then inserted with ring forceps transvaginally through the wound retractor. (See Figure 7.) The bag is unfolded intraperitoneally using the integral tabs to demarcate the edges of the bag. The bag should be unfolded in the pelvis with the opening of the bag cephalad. The fundus of the hysterectomy specimen is grasped with a tenaculum and placed inside the bag. (See Figure 8.)

It is an important technical point to grab the fundus or the heaviest point of the specimen to allow weight and gravity to facilitate placing the specimen securely in the bag. If the cervix or a lighter part of the specimen is grasped, placement in the bag is more difficult and the specimen will likely slip out of the bag.

Once the entire hysterectomy specimen is in the LapSac, the bag is cinched by grasping the blue drawstrings. The opening of the bag is pulled through the vagina. The opening of the bag is externalized and the edges are attached with Allis clamps to the external edge of the wound retractor. The specimen (typically the cervix first) is grasped with a tenaculum and vaginally morcellated and cored with a scalpel (Figure 9).

Metal vaginal retractors are placed within the bag to protect against sharp injury during morcellation. I prefer to amputate the cervix and adnexa separately and en bloc to preserve as much original architecture as possible so the pathologists can properly orient and examine the tissue. After completion of the morcellation, the wound retractor is removed, the cuff closed, and the procedure completed per surgeon preference.

Dr. Shibley has been in full-time practice with Ob.Gyn. Specialists, Fairview Health Services in the Minneapolis area (Edina), for 20 years. He reported that he has a financial interest in the artificial pneumoperitoneum device under development, and that he is a consultant for Olympus.

Dr. Taylor is a urogynecologist who is a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgeon practicing at the Carolinas Medical Center–Advanced Surgical Specialties for Women in Charlotte, N.C. He reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Dr. Nezhat is the current president of the AAGL, adjunct professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University and program director of minimally invasive surgery at Northside Hospital, both in Atlanta, and adjunct clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reported that he is a consultant for Karl Storz Endoscopy.

Videos of these experts' individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation within the confines of a bag, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, director of the Center for Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, can be viewed at the SurgeryU website.

Power morcellation within an insufflated bag

By Tony Shibley, M.D.

Morcellating safely in laparoscopic hysterectomy or myomectomy involves not only the use of a bag, but also the creation of an artificial pneumoperitoneum inside the bag. Inflation of the bag allows us to create a safe and completely contained working environment in the abdomen, with good visualization and adequate working space.

In the past, specimen containment bags were used for morcellation, but the bags would adhere to tissue and would be easily cut or would tear or rupture. Without proper space and visualization, surgeons could not break tissue into smaller fragments without endangering the bag or the structures behind the bag. We were safely and precisely disconnecting tissue in our surgeries, but falling short with tissue removal. There were calls for more durable bags, but the problems of visualization and safe distance were not addressed. Eventually, the goal of morcellating within a bag was largely abandoned in favor of open power morcellation.

I stopped performing open power morcellation about 2 years ago and developed a new approach to enclosed morcellation. By creating an artificial pneumoperitoneum in a bag, a good working space is developed within it. This meets the needs of containment while significantly lowering the risk of tissue dissemination and also reducing the risk of bowel injury, vascular injury, and other types of morcellator-related mechanical injuries. This approach to morcellation is safer on all fronts.

My method of enclosed morcellation has been utilized in both single-port and multiport hysterectomy (total and supracervical) and myomectomy performed with either traditional laparoscopy or the robotic platform.

The morcellation process is begun after surgery is complete except for tissue removal, and the patient is hemostatic. The specimen has been placed in a location where it can be easily retrieved; I prefer the right upper quadrant.

In a single-port approach, the bag is inserted into the abdomen through an open single-port cannula at the umbilicus. I use a Steri-Drape Isolation Bag (3M), 50 cm by 50 cm, with drawstrings. (See Figure 1.) Standing across from my assistant, I tightly fan-fold the bag and wring it to purge it of air. Using an atraumatic grasper, I position the bag linearly with the opening up; it is inserted into the pelvis first, with the superior end guided upward into the mid- and then upper-abdomen.

After the bag is placed, the cannula is recapped with the multiport cap. I use the Olympus TriPort 15 (Advanced Surgical Concepts), and the abdomen is reinsufflated. A camera is inserted into one of the 5-mm ports. I use the Olympus 5-mm articulating laparoscope.

Through the other 5-mm port, I maneuver the bag to form a pocket opening by pushing the upper corners of the bag against the respective abdominal sidewalls, and the body of the bag into the pelvis. I then elevate the specimen and, with a rotational movement, I guide the specimen along the right abdominal sidewall and into the pocket opening. I then elevate the sides of the bag and ensure that the specimen is well contained. (See Figure 2.)

The drawstrings are then brought up into the port hub. The cap is removed, and the opening of the bag is pulled up through the port and out approximately 15-20 cm, as symmetrically as possible.

The port cap is then replaced within the exteriorized neck of the bag, and the bag is insufflated with traditional laparoscopic pressure of 15-18 mm, creating an artificial pneumoperitoneum. (See Figure 3.) The camera is reinserted, followed by the morcellator, into the 15-mm port of the single-site tri-port. The morcellator must be lubricated so it does not catch the bag on the way in. Morcellation is carried out under direct vision.

After the morcellation process is complete, the morcellator is removed, followed by the camera and the tri-port cap. The bag is desufflated and removed through the open cannula, and the abdomen is closed as usual.

In a multiport approach, the umbilical incision is extended to 15 mm after completion of the hysterectomy or myomectomy. The bag is inserted and placed in a manner similar to the single-port approach, except that the lateral ports may be utilized to further position the bag once it is placed about halfway in. The bag is similarly opened, the specimen contained, and the neck of the bag exteriorized. A 15-mm port is similarly lubricated and placed inside the neck of the bag and through the umbilical incision.

As the bag is insufflated, the lateral ports are backed slightly out so that they're flush with the abdominal wall, and the trocars are opened to allow the release of any residual gas in the abdomen. The laparoscope is then placed into the 15-mm umbilical trocar.

Visualization will ultimately occur from another site, however. One of the lateral 5-mm trocars is advanced at a right angle to the insufflated bag, and an introducer is placed to puncture the bag. I recommend using a blunt plastic trocar; a balloon-tip trocar also can be used. Contrary to what one might think, the bag will not leak any gas. The laparoscope is now transferred to this 5-mm lateral port, and the umbilical port is removed. A lubricated morcellator is inserted directly through the umbilical incision, and morcellation is performed under direct visualization from the side port.

These techniques for single-port or multiport enclosed power morcellation have been shown to be reproducible and successful – with all bags intact and specimens contained – in a multicenter analysis that is being prepared for publication. The largest uterus in the study was 1,481 g.

To make the approach less cumbersome, I have designed a morcellation device consisting of a specialized bag that will open automatically and assist in capturing the specimen. The device, which has closure tabs and a retrieval lanyard, has been developed with the input of other minimally invasive gynecologic surgeons and the design and engineering expertise of Advanced Surgical Concepts. It will be manufactured by the company pending Food and Drug Administration approval.

Concealed power morcellation: Our take

By Bernard Taylor, M.D.

The approach to the use of power morcellation within a bag in my practice was not specifically driven by the desire to prevent the dispersion of malignant leiomyosarcoma – an issue that is now front and center and indeed, is important – but by a broader desire to perform as complete an extraction as possible.

For years we have used isolation bags to conceal and contain small uteri, ovaries, and specimens that we debulk using a scalpel and remove through a small umbilical incision. However, this approach is cumbersome for removing larger uteri. Consequently, over the past year we refined our methods for performing power morcellation within a bag.

This procedure can be performed after traditional laparoscopy or robotic-assisted hysterectomy or myomectomy to extract the specimen from the abdomen. A surgical tissue bag is placed into the abdomen and is insufflated within the abdomen. Morcellation is carried out within the concealed "pseudopneumoperitoneum," and the bag is exteriorized from the abdomen, typically through the umbilical incision.

The majority of my procedures utilize a multiport approach due to the nature of my practice as a urogynecologist. After hysterectomy or myomectomy, the specimen is placed in the upper abdomen. The cuff is closed, other procedures are completed in the usual fashion, and hemostasis is reassured. In robotic procedures, we undock the robot prior to morcellation. The umbilical port is removed, and the bag is placed into the abdomen with a ring forceps or atraumatic forceps without teeth. The umbilical port is then replaced to reestablish the pneumoperitoneum for visualization.

For larger uterine specimens, I use an Isodrape isolation bag (Microtek Medical). This 18 x 18 inch bag with a drawstring opening easily accommodates uteri larger than 1,000 g. The bag is placed into the pelvis with the open end at the pelvic brim and is opened wide. I use the term "open from iliac to iliac and sacrum to bladder." Once the bag is positioned, the specimen is grasped; the patient is slowly taken out of the Trendelenburg position to allow for gravity to assist in the placement of the specimen into the bag.

The drawstrings are then grasped and taken out of the umbilical trocar with simultaneous removal of the umbilical port. At this time, the open end of the bag is exteriorized, and the specimen technically is extraperitoneal and "concealed."

To insufflate the bag at this point and create the "pseudopneumoperitoneum," a 15-mm port is lubricated and placed through the opening in the bag. The bag is then insufflated to the usual pressure (15 mm Hg). The accessory ports are opened at this time to allow for the abdominal pressure to fall and for the bag to expand and fill the abdominal cavity.

To enable visualization throughout the morcellation procedure, I use one of the previously placed lower abdomen lateral ports to place a 5-mm camera. The camera is placed after a 5-mm balloon tip trocar is introduced and advanced to perforate the bag. The balloon tip is insufflated in the usual fashion, securing the bag against the abdominal wall and preventing a gas leak.

Alternatively, I have also used a SILSport (Covidien) at the umbilicus in cases when there is a leak at the umbilical incision and the 15-mm port does not seal properly. While use of a single-port technique has been shown to be feasible for both visualization and morcellation, it can present challenges in complex cases with a larger uterus or multiple fibroids.

Either way, morcellation can take place within the concealed "pseudo-peritoneal" cavity, with the morcellator lubricated and placed either through the umbilical incision or through the Tri-Port. After morcellation is complete, the bag containing the smaller tissue fragments and blood is simply removed through the umbilicus, and closure of the abdomen is completed in the usual fashion.

I also have adopted a simplified approach to remove the smaller uteri with supracervical hysterectomy and sacral colpopexy performed laparoscopically. Despite preoperative screening with endometrial biopsy and pelvic ultrasound, several of my patients in the past have been diagnosed with either early ovarian or endometrial neoplasias on final pathology. After completing the procedure, I place the small menopausal senile uterus and adnexa into a 15-mm endoscopic bag. The bag is brought through the umbilical port, and the specimen is removed via morcellation with a scalpel or scissors.

Surgeons have asked about additional time needed to place the bag and position the specimen. Technically, specimen placement is a learned skill; once one is proficient, the case times are not any different. In fact, cases may be shorter because of the time saved by not having to retrieve uterine fragments from the abdomen and pelvis.

Theoretically, the procedure addresses concerns associated with tissue fragmentation and dissemination within the abdominal cavity. To date, there are no trials showing prevention of cancer upstaging or benign conditions such as leiomyomatosis peritonealis disseminata or endometriosis.

Enclosed vaginal morcellation for enlarged uteri

By Ceana H. Nezhat, M.D.

Removal of large uteri via minimally invasive surgery poses challenges to gynecologic surgeons. Limitations on the use of intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation are a step forward in terms of protecting patients from undue harm, but we also must acknowledge that minimally invasive surgery has been shown to be superior to laparotomy in the majority of cases.

While safer ways to extract large specimens without risk of spreading both benign and malignant tissue are being studied and developed, gynecologic surgeons need to find alternative minimally invasive approaches for removing large specimens.

Minimally invasive approaches to extirpate uteri and myomas have been described prior to the advent of electromechanical morcellation. A natural orifice such as the vagina for gynecologic procedures is a clear choice for removing specimens. Laparoscopic-assisted myomectomy is a combination of laparoscopy and minilaparotomy for tissue extraction (JSLS 2001;5:299-303). Another alternative is extracting myoma and other tissues through a posterior colpotomy. Rates of dyspareunia and adhesions in the cul-de-sac after tissue extraction through a colpotomy are low (J. Reprod. Med. 1993;38:534-6).

Vaginal hysterectomy was chronicled and performed by the Greek physician Soranus of Ephesus in 120 A.D. (Acta Chir. Iugosl. 2011:58:9-14), and it is still the preferred route of hysterectomy when it can be performed. Large uteri can be transvaginally morcellated and vaginally extracted; however, this technique still poses the risk, although low, of spilling fragments of uterine tissue in the abdomen.

By combining total laparoscopic hysterectomy and vaginal morcellation of enlarged uteri within an enclosed specimen bag, the risk of spilling uterine fragments is reduced, in addition to avoiding potential visceral and vascular complications associated with intraperitoneal electromechanical morcellation.

Enclosed vaginal morcellation is the technique of placing the enlarged hysterectomy specimen in an endoscopic specimen retrieval bag and then transvaginally morcellating the tissue.

In the development of this technique, I have experimented with different endoscopic sacs and retractors. In my experience, the optimal laparoscopic bag is the LapSac Surgical Tissue Pouch (Cook Medical). This endoscopic, one-time use, specimen retrieval bag is flexible, durable nylon with an integral polyurethane inner coating and polypropylene drawstring (Figure 4). The bag comes in four sizes, the largest (size 8 x 10 inch, volume 1,500 mL) of which I used to assist in removing the 18-week size uterus in the accompanying video.

The other key piece of equipment for vaginal extraction of large uteri is a transvaginally-placed wound retractor. As I have previously described, the self-retaining retractor provides optimal exposure in a narrow field and minimizes trauma to surrounding tissue (J. Minim. Inv. Gynecol. 2009:16:616-7). Two wound retractors are suitable for this surgical technique: the Alexis Wound Protector/Retractor (Applied Medical) (Figure 5) and the Mobius Elastic Abdominal Retractor (Cooper Surgical) (Figure 6).

After complete laparoscopic detachment of the uterus and cervix (and adnexa), the wound retractor is placed transvaginally. One semirigid ring is pushed superiorly through the vagina and into the peritoneal cavity, where is it placed in the cul-de-sac. In this manner, a uniform, circumferential orifice is created. In narrower vaginal vaults, the ring can be compressed between the thumb and index finger to reduce its diameter and thus be introduced into the peritoneal cavity atraumatically. With the small-size retraction systems, an orifice of 2.5 to 6 cm diameter can be created.

The LapSac is folded and then inserted with ring forceps transvaginally through the wound retractor. (See Figure 7.) The bag is unfolded intraperitoneally using the integral tabs to demarcate the edges of the bag. The bag should be unfolded in the pelvis with the opening of the bag cephalad. The fundus of the hysterectomy specimen is grasped with a tenaculum and placed inside the bag. (See Figure 8.)

It is an important technical point to grab the fundus or the heaviest point of the specimen to allow weight and gravity to facilitate placing the specimen securely in the bag. If the cervix or a lighter part of the specimen is grasped, placement in the bag is more difficult and the specimen will likely slip out of the bag.

Once the entire hysterectomy specimen is in the LapSac, the bag is cinched by grasping the blue drawstrings. The opening of the bag is pulled through the vagina. The opening of the bag is externalized and the edges are attached with Allis clamps to the external edge of the wound retractor. The specimen (typically the cervix first) is grasped with a tenaculum and vaginally morcellated and cored with a scalpel (Figure 9).

Metal vaginal retractors are placed within the bag to protect against sharp injury during morcellation. I prefer to amputate the cervix and adnexa separately and en bloc to preserve as much original architecture as possible so the pathologists can properly orient and examine the tissue. After completion of the morcellation, the wound retractor is removed, the cuff closed, and the procedure completed per surgeon preference.

Dr. Shibley has been in full-time practice with Ob.Gyn. Specialists, Fairview Health Services in the Minneapolis area (Edina), for 20 years. He reported that he has a financial interest in the artificial pneumoperitoneum device under development, and that he is a consultant for Olympus.

Dr. Taylor is a urogynecologist who is a female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgeon practicing at the Carolinas Medical Center–Advanced Surgical Specialties for Women in Charlotte, N.C. He reported that he has no disclosures relevant to this Master Class.

Dr. Nezhat is the current president of the AAGL, adjunct professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University and program director of minimally invasive surgery at Northside Hospital, both in Atlanta, and adjunct clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford (Calif.) University. He reported that he is a consultant for Karl Storz Endoscopy.

Videos of these experts' individual techniques of electromechanical power morcellation within the confines of a bag, as well as that of Dr. Douglas Brown, director of the Center for Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, can be viewed at the SurgeryU website.