User login

Screening High-Risk Women Veterans for Breast Cancer

The number of women seeking care from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is increasing.1 In 2015, there were 2 million women veterans in the United States, which is 9.4% of the total veteran population. This group is expected to increase at an average of about 18,000 women per year for the next 10 years.2 The percentage of women veterans who are US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) users aged 45 to 64 years rose 46% from 2000 to 2015.1,3-4 It is estimated that 15% of veterans who used VA services in 2020 were women.1 Nineteen percent of women veterans are Black.1 The median age of women veterans in 2015 was 50 years.5 Breast cancer is the leading cancer affecting female veterans, and data suggest they have an increased risk of breast cancer based on unique service-related exposures.1,6-9

In the US, about 10 million women are eligible for breast cancer preventive therapy, including, but not limited to, medications, surgery, or lifestyle changes.10 Secondary prevention options include change in surveillance that can reduce their risk or identify cancer at an earlier stage when treatment is more effective. The United States Preventive Services Task Force, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and the Oncology Nursing Society recommend screening women aged ≥ 35 years to assess breast cancer risk.11-18 If a woman is at increased risk, she may be a candidate for chemoprevention, prozphylactic surgery, and possibly an enhanced screening regimen.

Urban and minority women are an understudied population. Most veterans (75%) live in urban or suburban settings.19,20 Urban veteran women constitute an important potential study population.

Chemoprevention measures have been underused because of factors involving both women and their health care providers. A large proportion of women are unaware of their higher risk status due to lack of adequate screening and risk assessment.21,22 In addition to patient lack of awareness of their high-risk status, primary care physicians are also reluctant to prescribe chemopreventive agents due to a lack of comfort or familiarity with the risks and benefits.23-26 The STAR2015, BCPT2005, IBIS2014, MAP3 2011, IBIS-I 2014, and IBIS II 2014 studies clearly demonstrate a 49 to 62% reduction in risk for women using chemoprevention such as selective estrogen receptor modulators or aromatase inhibitors, respectively.27-32 Yet only 4 to 9% of high-risk women not enrolled in a clinical trial are using chemoprevention.33-39

The possibility of developing breast cancer also may be increased because of a positive family history or being a member of a family in which there is a known susceptibility gene mutation.40 Based on these risk factors, women may be eligible for tailored follow-up and genetic counseling.41-44

Nationally, 7 to 10% of the civilian US population will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).45 The rates are remarkably higher for women veterans, with roughly 20% diagnosed with PTSD.46,47 Anxiety and PTSD have been implicated in poor adherence to medical advice.48,49

In 2014, a national VA multidisciplinary group focused on breast cancer prevention, detection, treatment, and research to address breast health in the growing population of women veterans. High-risk breast cancer screenings are not routinely carried out by the VA in primary care, women’s health, or oncology services. Furthermore, the recording of screening questionnaire results was not synchronized until a standard questionnaire was created and approved as a template by this group in the VA electronic medical record (EMR) in 2015.

Several prediction models can identify which women are at an increased risk of developing breast cancer. The most commonly used risk assessment model, the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool (BCRAT), has been refined to include women of additional ethnicities (https://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool).

This pilot project was launched to identify an effective manner to screen women veterans regarding their risk of developing breast cancer and refer them for chemoprevention education or genetic counseling as appropriate.

Methods

A high-risk breast cancer screening questionnaire based on the Gail BCRAT and including lifestyle questions was developed and included as a note template in the VA EMR. The James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Bronx, NY (JJPVAMC) and the Washington DC VA Medical Center (DCVAMC) ran a pilot study between 2015 and 2018 using this breast cancer screening questionnaire to collect data from women veterans. Quality Executive Committee and institutional review board approvals were granted respectively.

Eligibility criteria included women aged ≥ 35 years with no personal history of breast cancer. Most patients were self-referred, but participants also were recruited during VA Breast Cancer Awareness month events, health fairs, or at informational tables in the hospital lobbies. After completing the 20 multiple choice questionnaire with a study team member, either in person or over the phone, a 5-year and lifetime risk of invasive breast cancer was calculated using the Gail BCRAT. A woman is considered high risk and eligible for chemoprevention if her 5-year risk is > 1.66% or her lifetime risk is ≥ 20%. Eligibility for genetic counseling is based on the Breast Cancer Referral Screening Tool, which includes a personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer and Jewish ancestry.

All patients were notified of their average or high risk status by a clinician. Those who were deemed to be average risk received a follow-up letter in the mail with instructions (eg, to follow-up with a yearly mammogram). Those who were deemed to be high risk for developing breast cancer were asked to come in for an appointment with the study principal investigator (a VA oncologist/breast cancer specialist) to discuss prevention options, further screening, or referrals to genetic counseling. Depending on a patient’s other health factors, a woman at high risk for developing breast cancer also may be a candidate for chemoprevention with tamoxifen, raloxifene, exemestane, anastrozole, or letrozole.

Data on the participant’s lifestyle, including exercise, diet, and smoking, were evaluated to determine whether these factors had an impact on risk status.

Results

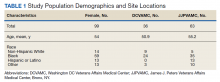

The JJP and DC VAMCs screened 103 women veterans between 2015 and 2018. Four patients were excluded for nonveteran (spousal) status, leaving 99 women veterans with a mean age of 54 years. The most common self-reported races were Black (60%), non-Hispanic White (14%), and Hispanic or Latino (13%) (Table 1).

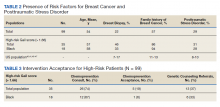

Women veterans in our study were nearly 3-times more likely than the general population were to receive a high-risk Gail Score/BCRAT (35% vs 13%, respectively).50,51 Of this subset, 46% had breast biopsies, and 86% had a positive family history. Thirty-one percent of Black women in our study were high risk, while nationally, 8.2 to 13.3% of Black women aged 50 to 59 years are considered high risk.50,51 Of the Black high-risk group with a high Gail/BCRAT score, 94% had a positive family history, and 33% had a history of breast biopsy (Table 2).

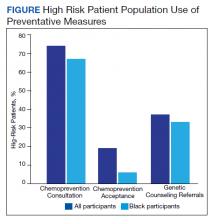

Of the 35 high-risk patients 26 (74%) patients accepted consultations for chemoprevention and 5 (19%) started chemoprevention. Of this high-risk group, 13 (37%) patients were referred for genetic counseling (Table 3).44 The prevalence of PTSD was present in 31% of high-risk women and 29% of the cohort (Figure).The lifestyle questions indicated that, among all participants, 79% had an overweight or obese body mass index; 58% exercised weekly; 51% consumed alcohol; 14% were smokers; and 21% consumed 3 to 4 servings of fruits/vegetables daily.

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women.52 The number of women with breast cancer in the VHA has more than tripled from 1995 to 2012.1 The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer in the general population is about 13%.50 This rate can be affected by risk factors including age, hormone exposure, family history, radiation exposure, and lifestyle factors, such as weight and alcohol use.6,52-56 In the United States, invasive breast cancer affects 1 in 8 women.50,52,57

Our screened population showed nearly 3 times as many women veterans were at an increased risk for breast cancer when compared with historical averages in US women. This difference may be based on a high rate of prior breast biopsies or positive family history, although a provocative study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database showed military women to have higher rates of breast cancer as well.9 Historically, Blacks are vastly understudied in clinical research with only 5% representation on a national level.5,58 The urban locations of both pilot sites (Washington, DC and Bronx, NY) allowed for the inclusion of minority patients in our study. We found that the rates of breast cancer in Black women veterans to be higher than seen nationally, possibly prompting further screening initiatives for this understudied population.

Our pilot study’s chemoprevention utilization (19%) was double the < 10% seen in the national population.33-35 The presence of a knowledgeable breast health practitioner to recruit study participants and offer personalized counseling to women veterans is a likely factor in overcoming barriers to chemopreventive acceptance. These participants may have been motivated to seek care for their high-risk status given a strong family history and prior breast biopsies.

Interestingly, a 3-fold higher PTSD rate was seen in this pilot population (29%) when compared with PTSD rates in the general female population (7-10%) and still one-third higher than the general population of women veterans (20%).45-47 Mental health, anxiety, and PTSD have been barriers to patients who sought treatment and have been implicated in poor adherence to medical advice.48,49 Cancer screening can induce anxiety in patients, and it may be amplified in patients with PTSD. It was remarkable that although adherence with screening recommendations is decreased when PTSD is present, our patient population demonstrated a higher rate of screening adherence.

Women who are seen at the VA often use multiple clinical specialties, and their EMR can be accessed across VA medical centers nationwide. Therefore, identifying women veterans who meet screening criteria is easily attainable within the VA.

When comparing high-risk with average risk women, the lifestyle results (BMI, smoking history, exercise and consumption of fruits, vegetables and alcohol) were essentially the same. Lifestyle factors were similar to national population rates and were unlikely to impact risk levels.

Limitations

Study limitations included a high number of self-referrals and the large percentage of patients with a family history of breast cancer, making them more likely to seek screening. The higher-than-average risk of breast cancer may be driven by a high rate of breast biopsies and a strong family history. Lifestyle metrics could not be accurately compared to other national assessments of lifestyle factors due to the difference in data points that we used or the format of our questions.

Conclusions

As the number of women veterans increases and the incidence of breast cancer in women veterans rise, chemoprevention options should follow national guidelines. To our knowledge, this is the only oncology study with 60% Black women veterans. This study had a higher participation rate for Black women veterans than is typically seen in national research studies and shows the VA to be a germane source for further understanding of an understudied population that may benefit from increased screening for breast cancer.

A team-based, multidisciplinary model that meets the unique healthcare needs of women veterans results in a patient-centric delivery of care for assessing breast cancer risk status and prevention options. This model can be replicated nationally by directing primary care physicians and women’s health practitioners to a risk-assessment questionnaire and referring high-risk women for appropriate preventative care. Given that these results show chemoprevention adherence rates doubled those seen nationally, perhaps techniques used within this VA pilot study may be adapted to decrease breast cancer incidence nationally.

Since the rate of PTSD among women veterans is triple the national average, we would expect adherence rates to be lower in our patient cohort. However, the multidisciplinary approach we used in this study (eg, 1:1 consultation with oncologist; genetic counseling referrals; mental health support available), may have improved adherence rates. Perhaps the high rates of PTSD seen in the VA patient population can be a useful way to explore patient adherence rates in those with mental illness and medical conditions.

Future research with a larger cohort may lead to greater insight into the correlation between PTSD and adherence to treatment. Exploring the connection between breast cancer, epigenetics, and specific military service-related exposures could be an area of analysis among this veteran population exhibiting increased breast cancer rates. VAMCs are situated in rural, suburban, and urban locations across the United States and offers a diverse socioeconomic and ethnic patient population for inclusion in clinical investigations. Women veterans make up a small subpopulation of women in the United States, but it is worth considering VA patients as an untapped resource for research collaboration.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steven Sanchez and Marissa Vallette, PhD, Breast Health Research Group. This research project was approved by the James J. Peters VA Medical Center Quality Executive Committee and the Washington, DC VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board. This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. The past, present and future of women veterans. Published February 2017. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/women_veterans_2015_final.pdf.

2. Frayne SM, Carney DV, Bastian L, et al. The VA Women’s Health Practice-Based Research Network: amplifying women veterans’ voices in VA research. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S504-S509. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2476-3

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative, Women Veterans Health Strategic Health Care Group. Sourcebook: women veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 1: Sociodemographic characteristics and use of VHA care. Published December 2010. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2455

4. Bean-Mayberry B, Yano EM, Bayliss N, Navratil J, Weisman CS, Scholle SH. Federally funded comprehensive women’s health centers: leading innovation in women’s healthcare delivery. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16(9):1281-1290. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.0284

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics.VA utilization profile FY 2016. Published November 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/QuickFacts/VA_Utilization_Profile.PDF

6. Ekenga CC, Parks CG, Sandler DP. Chemical exposures in the workplace and breast cancer risk: a prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(7):1765-1774. doi:10.1002/ijc.29545

7. Rennix CP, Quinn MM, Amoroso PJ, Eisen EA, Wegman DH. Risk of breast cancer among enlisted Army women occupationally exposed to volatile organic compounds. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(3):157-167. doi:10.1002/ajim.20201

8. Ritz B. Cancer mortality among workers exposed to chemicals during uranium processing. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(7):556-566. doi:10.1097/00043764-199907000-00004

9. Zhu K, Devesa SS, Wu H, et al. Cancer incidence in the U.S. military population: comparison with rates from the SEER program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1740-1745. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0041

10. Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2013 Nov 10;31(32):4167]. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2327-2333. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0258

11. Greene, H. Cancer prevention, screening and early detection. In: Gobel BH, Triest-Robertson S, Vogel WH, eds. Advanced Oncology Nursing Certification Review and Resource Manual. 3rd ed. Oncology Nursing Society; 2016:1-34. https://www.ons.org/sites/default/files/publication_pdfs/2%20ADVPrac%20chapter%201.pdf

12. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Breast Cancer Risk Reduction. Version 1.2021 NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Updated March 24, 2021 Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_risk.pdf

13. US Preventive Services Task Force. Breast cancer: Medications use to reduce risk. Updated September 3, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/breast-cancer-medications-for-risk-reduction

14. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Medications to decrease the risk for breast cancer in women: recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(10):698-708. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00717

15. Boucher JE. Chemoprevention: an overview of pharmacologic agents and nursing considerations. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(3):350-353. doi:10.1188/18.CJON.350-353

16. Nichols HB, Stürmer T, Lee VS, et al. Breast cancer chemoprevention in an integrated health care setting. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2017;1:1-12. doi:10.1200/CCI.16.00059

17. Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis, Version 3.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(11):1362-1389. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2018.0083

18. Visvanathan K, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Use of pharmacologic interventions for breast cancer risk reduction: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2013 Dec 1;31(34):4383]. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2942-2962. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3122

19. Sealy-Jefferson S, Roseland ME, Cote ML, et al. rural-urban residence and stage at breast cancer diagnosis among postmenopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(2):276-283. doi:10.1089/jwh.2017.6884

20. Holder KA. Veterans in rural America: 2011-2015. Published January 25, 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/acs/acs-36.html

21. Owens WL, Gallagher TJ, Kincheloe MJ, Ruetten VL. Implementation in a large health system of a program to identify women at high risk for breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(2):85-88. doi:10.1200/JOP.2010.000107

2. Pivot X, Viguier J, Touboul C, et al. Breast cancer screening controversy: too much or not enough?. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24 Suppl:S73-S76. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000145

23. Bidassie B, Kovach A, Vallette MA, et al. Breast Cancer risk assessment and chemoprevention use among veterans affairs primary care providers: a national online survey. Mil Med. 2020;185(3-4):512-518. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz291

24. Brewster AM, Davidson NE, McCaskill-Stevens W. Chemoprevention for breast cancer: overcoming barriers to treatment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2012;85-90. doi:10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.152

25. Meyskens FL Jr, Curt GA, Brenner DE, et al. Regulatory approval of cancer risk-reducing (chemopreventive) drugs: moving what we have learned into the clinic. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(3):311-323. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0014

26. Tice JA, Kerlikowske K. Screening and prevention of breast cancer in primary care. Prim Care. 2009;36(3):533-558. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2009.04.003

27. Vogel VG. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer chemoprevention. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12(13):1874-1887. doi:10.2174/138945011798184164

28. Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial [published correction appears in JAMA. 2006 Dec 27;296(24):2926] [published correction appears in JAMA. 2007 Sep 5;298(9):973]. JAMA. 2006;295(23):2727-2741. doi:10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074

29. Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3230-3235. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-4715-9

30. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, et al. Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): an international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2014 Mar 22;383(9922):1040] [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017 Mar 11;389(10073):1010]. Lancet. 2014;383(9922):1041-1048. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62292-8

31. Bozovic-Spasojevic I, Azambuja E, McCaskill-Stevens W, Dinh P, Cardoso F. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(5):329-339. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.07.005

32. Gabriel EM, Jatoi I. Breast cancer chemoprevention. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12(2):223-228. doi:10.1586/era.11.206

33. Crew KD, Albain KS, Hershman DL, Unger JM, Lo SS. How do we increase uptake of tamoxifen and other anti-estrogens for breast cancer prevention?. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2017;3:20. Published 2017 May 19. doi:10.1038/s41523-017-0021-y

34. Ropka ME, Keim J, Philbrick JT. Patient decisions about breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):3090-3095. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.8077

35. Smith SG, Sestak I, Forster A, et al. Factors affecting uptake and adherence to breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(4):575-590. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdv590

36. Grann VR, Patel PR, Jacobson JS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of screening and prevention strategies among BRCA1/2-affected mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011 Feb;125(3):837-847. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1043-4

37. Goss PE, Ingle JN, Alés-Martínez JE, et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2011 Oct 6;365(14):1361]. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2381-2391. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1103507

38. Kmietowicz Z. Five in six women reject drugs that could reduce their risk of breast cancer. BMJ. 2015;351:h6650. Published 2015 Dec 8. doi:10.1136/bmj.h6650

39. Nelson HD, Fu R, Griffin JC, Nygren P, Smith ME, Humphrey L. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of medications to reduce risk for primary breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):703-235. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00147

40. Dahabreh IJ, Wieland LS, Adam GP, Halladay C, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Core needle and open surgery biopsy for diagnosis of breast lesions: an update to the 2009 report. Published September 2014. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK246878

41. National Cancer Institute. Genetics of breast and ovarian cancer (PDQ)—health profession version. Updated February 12, 2021. Accessed April 12, 2021. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/genetics/breast-and-ovarian/HealthProfessional

42. US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences The sister study. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://sisterstudy.niehs.nih.gov/english/NIEHS.htm

43. Tutt A, Ashworth A. Can genetic testing guide treatment in breast cancer?. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(18):2774-2780. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.009

44. Katz SJ, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, et al. Gaps in receipt of clinically indicated genetic counseling after diagnosis of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(12):1218-1224. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.76.2369

45. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. How common is PTSD in adults? Updated October 17, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp

46. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. How common is PTSD in women? Updated October 16, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_women.asp

47. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. How common is PTSD in veterans? Updated September 24, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp

48. Lindberg NM, Wellisch D. Anxiety and compliance among women at high risk for breast cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23(4):298-303. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2304_9

49. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101

50. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR appendix: breast cancer rates among black women and white women. Updated October 13, 2016. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/trends_invasive.htm

51. Richardson LC, Henley SJ, Miller JW, Massetti G, Thomas CC. Patterns and trends in age-specific black-white differences in breast cancer incidence and mortality - United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(40):1093-1098. Published 2016 Oct 14. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6540a1

52. Brody JG, Moysich KB, Humblet O, Attfield KR, Beehler GP, Rudel RA. Environmental pollutants and breast cancer: epidemiologic studies. Cancer. 2007;109(12 Suppl):2667-2711. doi:10.1002/cncr.22655

53. Brophy JT, Keith MM, Watterson A, et al. Breast cancer risk in relation to occupations with exposure to carcinogens and endocrine disruptors: a Canadian case-control study. Environ Health. 2012;11:87. Published 2012 Nov 19. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-11-87

54. Labrèche F, Goldberg MS, Valois MF, Nadon L. Postmenopausal breast cancer and occupational exposures. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(4):263-269. doi:10.1136/oem.2009.049817

55. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Interagency Breast Cancer & Environmental Research Coordinating Committee. Breast cancer and the environment: prioritizing prevention. Updated March 8, 2013. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/about/boards/ibcercc/index.cfm

56. Gail MH, Costantino JP, Pee D, et al. Projecting individualized absolute invasive breast cancer risk in African American women [published correction appears in J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Aug 6;100(15):1118] [published correction appears in J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Mar 5;100(5):373]. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(23):1782-1792. doi:10.1093/jnci/djm223

57. Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):537-546. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x

58. Braunstein JB, Sherber NS, Schulman SP, Ding EL, Powe NR. Race, medical researcher distrust, perceived harm, and willingness to participate in cardiovascular prevention trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008;87(1):1-9. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3181625d78

The number of women seeking care from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is increasing.1 In 2015, there were 2 million women veterans in the United States, which is 9.4% of the total veteran population. This group is expected to increase at an average of about 18,000 women per year for the next 10 years.2 The percentage of women veterans who are US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) users aged 45 to 64 years rose 46% from 2000 to 2015.1,3-4 It is estimated that 15% of veterans who used VA services in 2020 were women.1 Nineteen percent of women veterans are Black.1 The median age of women veterans in 2015 was 50 years.5 Breast cancer is the leading cancer affecting female veterans, and data suggest they have an increased risk of breast cancer based on unique service-related exposures.1,6-9

In the US, about 10 million women are eligible for breast cancer preventive therapy, including, but not limited to, medications, surgery, or lifestyle changes.10 Secondary prevention options include change in surveillance that can reduce their risk or identify cancer at an earlier stage when treatment is more effective. The United States Preventive Services Task Force, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and the Oncology Nursing Society recommend screening women aged ≥ 35 years to assess breast cancer risk.11-18 If a woman is at increased risk, she may be a candidate for chemoprevention, prozphylactic surgery, and possibly an enhanced screening regimen.

Urban and minority women are an understudied population. Most veterans (75%) live in urban or suburban settings.19,20 Urban veteran women constitute an important potential study population.

Chemoprevention measures have been underused because of factors involving both women and their health care providers. A large proportion of women are unaware of their higher risk status due to lack of adequate screening and risk assessment.21,22 In addition to patient lack of awareness of their high-risk status, primary care physicians are also reluctant to prescribe chemopreventive agents due to a lack of comfort or familiarity with the risks and benefits.23-26 The STAR2015, BCPT2005, IBIS2014, MAP3 2011, IBIS-I 2014, and IBIS II 2014 studies clearly demonstrate a 49 to 62% reduction in risk for women using chemoprevention such as selective estrogen receptor modulators or aromatase inhibitors, respectively.27-32 Yet only 4 to 9% of high-risk women not enrolled in a clinical trial are using chemoprevention.33-39

The possibility of developing breast cancer also may be increased because of a positive family history or being a member of a family in which there is a known susceptibility gene mutation.40 Based on these risk factors, women may be eligible for tailored follow-up and genetic counseling.41-44

Nationally, 7 to 10% of the civilian US population will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).45 The rates are remarkably higher for women veterans, with roughly 20% diagnosed with PTSD.46,47 Anxiety and PTSD have been implicated in poor adherence to medical advice.48,49

In 2014, a national VA multidisciplinary group focused on breast cancer prevention, detection, treatment, and research to address breast health in the growing population of women veterans. High-risk breast cancer screenings are not routinely carried out by the VA in primary care, women’s health, or oncology services. Furthermore, the recording of screening questionnaire results was not synchronized until a standard questionnaire was created and approved as a template by this group in the VA electronic medical record (EMR) in 2015.

Several prediction models can identify which women are at an increased risk of developing breast cancer. The most commonly used risk assessment model, the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool (BCRAT), has been refined to include women of additional ethnicities (https://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool).

This pilot project was launched to identify an effective manner to screen women veterans regarding their risk of developing breast cancer and refer them for chemoprevention education or genetic counseling as appropriate.

Methods

A high-risk breast cancer screening questionnaire based on the Gail BCRAT and including lifestyle questions was developed and included as a note template in the VA EMR. The James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Bronx, NY (JJPVAMC) and the Washington DC VA Medical Center (DCVAMC) ran a pilot study between 2015 and 2018 using this breast cancer screening questionnaire to collect data from women veterans. Quality Executive Committee and institutional review board approvals were granted respectively.

Eligibility criteria included women aged ≥ 35 years with no personal history of breast cancer. Most patients were self-referred, but participants also were recruited during VA Breast Cancer Awareness month events, health fairs, or at informational tables in the hospital lobbies. After completing the 20 multiple choice questionnaire with a study team member, either in person or over the phone, a 5-year and lifetime risk of invasive breast cancer was calculated using the Gail BCRAT. A woman is considered high risk and eligible for chemoprevention if her 5-year risk is > 1.66% or her lifetime risk is ≥ 20%. Eligibility for genetic counseling is based on the Breast Cancer Referral Screening Tool, which includes a personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer and Jewish ancestry.

All patients were notified of their average or high risk status by a clinician. Those who were deemed to be average risk received a follow-up letter in the mail with instructions (eg, to follow-up with a yearly mammogram). Those who were deemed to be high risk for developing breast cancer were asked to come in for an appointment with the study principal investigator (a VA oncologist/breast cancer specialist) to discuss prevention options, further screening, or referrals to genetic counseling. Depending on a patient’s other health factors, a woman at high risk for developing breast cancer also may be a candidate for chemoprevention with tamoxifen, raloxifene, exemestane, anastrozole, or letrozole.

Data on the participant’s lifestyle, including exercise, diet, and smoking, were evaluated to determine whether these factors had an impact on risk status.

Results

The JJP and DC VAMCs screened 103 women veterans between 2015 and 2018. Four patients were excluded for nonveteran (spousal) status, leaving 99 women veterans with a mean age of 54 years. The most common self-reported races were Black (60%), non-Hispanic White (14%), and Hispanic or Latino (13%) (Table 1).

Women veterans in our study were nearly 3-times more likely than the general population were to receive a high-risk Gail Score/BCRAT (35% vs 13%, respectively).50,51 Of this subset, 46% had breast biopsies, and 86% had a positive family history. Thirty-one percent of Black women in our study were high risk, while nationally, 8.2 to 13.3% of Black women aged 50 to 59 years are considered high risk.50,51 Of the Black high-risk group with a high Gail/BCRAT score, 94% had a positive family history, and 33% had a history of breast biopsy (Table 2).

Of the 35 high-risk patients 26 (74%) patients accepted consultations for chemoprevention and 5 (19%) started chemoprevention. Of this high-risk group, 13 (37%) patients were referred for genetic counseling (Table 3).44 The prevalence of PTSD was present in 31% of high-risk women and 29% of the cohort (Figure).The lifestyle questions indicated that, among all participants, 79% had an overweight or obese body mass index; 58% exercised weekly; 51% consumed alcohol; 14% were smokers; and 21% consumed 3 to 4 servings of fruits/vegetables daily.

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women.52 The number of women with breast cancer in the VHA has more than tripled from 1995 to 2012.1 The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer in the general population is about 13%.50 This rate can be affected by risk factors including age, hormone exposure, family history, radiation exposure, and lifestyle factors, such as weight and alcohol use.6,52-56 In the United States, invasive breast cancer affects 1 in 8 women.50,52,57

Our screened population showed nearly 3 times as many women veterans were at an increased risk for breast cancer when compared with historical averages in US women. This difference may be based on a high rate of prior breast biopsies or positive family history, although a provocative study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database showed military women to have higher rates of breast cancer as well.9 Historically, Blacks are vastly understudied in clinical research with only 5% representation on a national level.5,58 The urban locations of both pilot sites (Washington, DC and Bronx, NY) allowed for the inclusion of minority patients in our study. We found that the rates of breast cancer in Black women veterans to be higher than seen nationally, possibly prompting further screening initiatives for this understudied population.

Our pilot study’s chemoprevention utilization (19%) was double the < 10% seen in the national population.33-35 The presence of a knowledgeable breast health practitioner to recruit study participants and offer personalized counseling to women veterans is a likely factor in overcoming barriers to chemopreventive acceptance. These participants may have been motivated to seek care for their high-risk status given a strong family history and prior breast biopsies.

Interestingly, a 3-fold higher PTSD rate was seen in this pilot population (29%) when compared with PTSD rates in the general female population (7-10%) and still one-third higher than the general population of women veterans (20%).45-47 Mental health, anxiety, and PTSD have been barriers to patients who sought treatment and have been implicated in poor adherence to medical advice.48,49 Cancer screening can induce anxiety in patients, and it may be amplified in patients with PTSD. It was remarkable that although adherence with screening recommendations is decreased when PTSD is present, our patient population demonstrated a higher rate of screening adherence.

Women who are seen at the VA often use multiple clinical specialties, and their EMR can be accessed across VA medical centers nationwide. Therefore, identifying women veterans who meet screening criteria is easily attainable within the VA.

When comparing high-risk with average risk women, the lifestyle results (BMI, smoking history, exercise and consumption of fruits, vegetables and alcohol) were essentially the same. Lifestyle factors were similar to national population rates and were unlikely to impact risk levels.

Limitations

Study limitations included a high number of self-referrals and the large percentage of patients with a family history of breast cancer, making them more likely to seek screening. The higher-than-average risk of breast cancer may be driven by a high rate of breast biopsies and a strong family history. Lifestyle metrics could not be accurately compared to other national assessments of lifestyle factors due to the difference in data points that we used or the format of our questions.

Conclusions

As the number of women veterans increases and the incidence of breast cancer in women veterans rise, chemoprevention options should follow national guidelines. To our knowledge, this is the only oncology study with 60% Black women veterans. This study had a higher participation rate for Black women veterans than is typically seen in national research studies and shows the VA to be a germane source for further understanding of an understudied population that may benefit from increased screening for breast cancer.

A team-based, multidisciplinary model that meets the unique healthcare needs of women veterans results in a patient-centric delivery of care for assessing breast cancer risk status and prevention options. This model can be replicated nationally by directing primary care physicians and women’s health practitioners to a risk-assessment questionnaire and referring high-risk women for appropriate preventative care. Given that these results show chemoprevention adherence rates doubled those seen nationally, perhaps techniques used within this VA pilot study may be adapted to decrease breast cancer incidence nationally.

Since the rate of PTSD among women veterans is triple the national average, we would expect adherence rates to be lower in our patient cohort. However, the multidisciplinary approach we used in this study (eg, 1:1 consultation with oncologist; genetic counseling referrals; mental health support available), may have improved adherence rates. Perhaps the high rates of PTSD seen in the VA patient population can be a useful way to explore patient adherence rates in those with mental illness and medical conditions.

Future research with a larger cohort may lead to greater insight into the correlation between PTSD and adherence to treatment. Exploring the connection between breast cancer, epigenetics, and specific military service-related exposures could be an area of analysis among this veteran population exhibiting increased breast cancer rates. VAMCs are situated in rural, suburban, and urban locations across the United States and offers a diverse socioeconomic and ethnic patient population for inclusion in clinical investigations. Women veterans make up a small subpopulation of women in the United States, but it is worth considering VA patients as an untapped resource for research collaboration.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steven Sanchez and Marissa Vallette, PhD, Breast Health Research Group. This research project was approved by the James J. Peters VA Medical Center Quality Executive Committee and the Washington, DC VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board. This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

The number of women seeking care from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is increasing.1 In 2015, there were 2 million women veterans in the United States, which is 9.4% of the total veteran population. This group is expected to increase at an average of about 18,000 women per year for the next 10 years.2 The percentage of women veterans who are US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) users aged 45 to 64 years rose 46% from 2000 to 2015.1,3-4 It is estimated that 15% of veterans who used VA services in 2020 were women.1 Nineteen percent of women veterans are Black.1 The median age of women veterans in 2015 was 50 years.5 Breast cancer is the leading cancer affecting female veterans, and data suggest they have an increased risk of breast cancer based on unique service-related exposures.1,6-9

In the US, about 10 million women are eligible for breast cancer preventive therapy, including, but not limited to, medications, surgery, or lifestyle changes.10 Secondary prevention options include change in surveillance that can reduce their risk or identify cancer at an earlier stage when treatment is more effective. The United States Preventive Services Task Force, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, the American Society for Clinical Oncology, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and the Oncology Nursing Society recommend screening women aged ≥ 35 years to assess breast cancer risk.11-18 If a woman is at increased risk, she may be a candidate for chemoprevention, prozphylactic surgery, and possibly an enhanced screening regimen.

Urban and minority women are an understudied population. Most veterans (75%) live in urban or suburban settings.19,20 Urban veteran women constitute an important potential study population.

Chemoprevention measures have been underused because of factors involving both women and their health care providers. A large proportion of women are unaware of their higher risk status due to lack of adequate screening and risk assessment.21,22 In addition to patient lack of awareness of their high-risk status, primary care physicians are also reluctant to prescribe chemopreventive agents due to a lack of comfort or familiarity with the risks and benefits.23-26 The STAR2015, BCPT2005, IBIS2014, MAP3 2011, IBIS-I 2014, and IBIS II 2014 studies clearly demonstrate a 49 to 62% reduction in risk for women using chemoprevention such as selective estrogen receptor modulators or aromatase inhibitors, respectively.27-32 Yet only 4 to 9% of high-risk women not enrolled in a clinical trial are using chemoprevention.33-39

The possibility of developing breast cancer also may be increased because of a positive family history or being a member of a family in which there is a known susceptibility gene mutation.40 Based on these risk factors, women may be eligible for tailored follow-up and genetic counseling.41-44

Nationally, 7 to 10% of the civilian US population will experience posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).45 The rates are remarkably higher for women veterans, with roughly 20% diagnosed with PTSD.46,47 Anxiety and PTSD have been implicated in poor adherence to medical advice.48,49

In 2014, a national VA multidisciplinary group focused on breast cancer prevention, detection, treatment, and research to address breast health in the growing population of women veterans. High-risk breast cancer screenings are not routinely carried out by the VA in primary care, women’s health, or oncology services. Furthermore, the recording of screening questionnaire results was not synchronized until a standard questionnaire was created and approved as a template by this group in the VA electronic medical record (EMR) in 2015.

Several prediction models can identify which women are at an increased risk of developing breast cancer. The most commonly used risk assessment model, the Gail breast cancer risk assessment tool (BCRAT), has been refined to include women of additional ethnicities (https://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool).

This pilot project was launched to identify an effective manner to screen women veterans regarding their risk of developing breast cancer and refer them for chemoprevention education or genetic counseling as appropriate.

Methods

A high-risk breast cancer screening questionnaire based on the Gail BCRAT and including lifestyle questions was developed and included as a note template in the VA EMR. The James J. Peters VA Medical Center, Bronx, NY (JJPVAMC) and the Washington DC VA Medical Center (DCVAMC) ran a pilot study between 2015 and 2018 using this breast cancer screening questionnaire to collect data from women veterans. Quality Executive Committee and institutional review board approvals were granted respectively.

Eligibility criteria included women aged ≥ 35 years with no personal history of breast cancer. Most patients were self-referred, but participants also were recruited during VA Breast Cancer Awareness month events, health fairs, or at informational tables in the hospital lobbies. After completing the 20 multiple choice questionnaire with a study team member, either in person or over the phone, a 5-year and lifetime risk of invasive breast cancer was calculated using the Gail BCRAT. A woman is considered high risk and eligible for chemoprevention if her 5-year risk is > 1.66% or her lifetime risk is ≥ 20%. Eligibility for genetic counseling is based on the Breast Cancer Referral Screening Tool, which includes a personal or family history of breast or ovarian cancer and Jewish ancestry.

All patients were notified of their average or high risk status by a clinician. Those who were deemed to be average risk received a follow-up letter in the mail with instructions (eg, to follow-up with a yearly mammogram). Those who were deemed to be high risk for developing breast cancer were asked to come in for an appointment with the study principal investigator (a VA oncologist/breast cancer specialist) to discuss prevention options, further screening, or referrals to genetic counseling. Depending on a patient’s other health factors, a woman at high risk for developing breast cancer also may be a candidate for chemoprevention with tamoxifen, raloxifene, exemestane, anastrozole, or letrozole.

Data on the participant’s lifestyle, including exercise, diet, and smoking, were evaluated to determine whether these factors had an impact on risk status.

Results

The JJP and DC VAMCs screened 103 women veterans between 2015 and 2018. Four patients were excluded for nonveteran (spousal) status, leaving 99 women veterans with a mean age of 54 years. The most common self-reported races were Black (60%), non-Hispanic White (14%), and Hispanic or Latino (13%) (Table 1).

Women veterans in our study were nearly 3-times more likely than the general population were to receive a high-risk Gail Score/BCRAT (35% vs 13%, respectively).50,51 Of this subset, 46% had breast biopsies, and 86% had a positive family history. Thirty-one percent of Black women in our study were high risk, while nationally, 8.2 to 13.3% of Black women aged 50 to 59 years are considered high risk.50,51 Of the Black high-risk group with a high Gail/BCRAT score, 94% had a positive family history, and 33% had a history of breast biopsy (Table 2).

Of the 35 high-risk patients 26 (74%) patients accepted consultations for chemoprevention and 5 (19%) started chemoprevention. Of this high-risk group, 13 (37%) patients were referred for genetic counseling (Table 3).44 The prevalence of PTSD was present in 31% of high-risk women and 29% of the cohort (Figure).The lifestyle questions indicated that, among all participants, 79% had an overweight or obese body mass index; 58% exercised weekly; 51% consumed alcohol; 14% were smokers; and 21% consumed 3 to 4 servings of fruits/vegetables daily.

Discussion

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in women.52 The number of women with breast cancer in the VHA has more than tripled from 1995 to 2012.1 The lifetime risk of developing breast cancer in the general population is about 13%.50 This rate can be affected by risk factors including age, hormone exposure, family history, radiation exposure, and lifestyle factors, such as weight and alcohol use.6,52-56 In the United States, invasive breast cancer affects 1 in 8 women.50,52,57

Our screened population showed nearly 3 times as many women veterans were at an increased risk for breast cancer when compared with historical averages in US women. This difference may be based on a high rate of prior breast biopsies or positive family history, although a provocative study using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database showed military women to have higher rates of breast cancer as well.9 Historically, Blacks are vastly understudied in clinical research with only 5% representation on a national level.5,58 The urban locations of both pilot sites (Washington, DC and Bronx, NY) allowed for the inclusion of minority patients in our study. We found that the rates of breast cancer in Black women veterans to be higher than seen nationally, possibly prompting further screening initiatives for this understudied population.

Our pilot study’s chemoprevention utilization (19%) was double the < 10% seen in the national population.33-35 The presence of a knowledgeable breast health practitioner to recruit study participants and offer personalized counseling to women veterans is a likely factor in overcoming barriers to chemopreventive acceptance. These participants may have been motivated to seek care for their high-risk status given a strong family history and prior breast biopsies.

Interestingly, a 3-fold higher PTSD rate was seen in this pilot population (29%) when compared with PTSD rates in the general female population (7-10%) and still one-third higher than the general population of women veterans (20%).45-47 Mental health, anxiety, and PTSD have been barriers to patients who sought treatment and have been implicated in poor adherence to medical advice.48,49 Cancer screening can induce anxiety in patients, and it may be amplified in patients with PTSD. It was remarkable that although adherence with screening recommendations is decreased when PTSD is present, our patient population demonstrated a higher rate of screening adherence.

Women who are seen at the VA often use multiple clinical specialties, and their EMR can be accessed across VA medical centers nationwide. Therefore, identifying women veterans who meet screening criteria is easily attainable within the VA.

When comparing high-risk with average risk women, the lifestyle results (BMI, smoking history, exercise and consumption of fruits, vegetables and alcohol) were essentially the same. Lifestyle factors were similar to national population rates and were unlikely to impact risk levels.

Limitations

Study limitations included a high number of self-referrals and the large percentage of patients with a family history of breast cancer, making them more likely to seek screening. The higher-than-average risk of breast cancer may be driven by a high rate of breast biopsies and a strong family history. Lifestyle metrics could not be accurately compared to other national assessments of lifestyle factors due to the difference in data points that we used or the format of our questions.

Conclusions

As the number of women veterans increases and the incidence of breast cancer in women veterans rise, chemoprevention options should follow national guidelines. To our knowledge, this is the only oncology study with 60% Black women veterans. This study had a higher participation rate for Black women veterans than is typically seen in national research studies and shows the VA to be a germane source for further understanding of an understudied population that may benefit from increased screening for breast cancer.

A team-based, multidisciplinary model that meets the unique healthcare needs of women veterans results in a patient-centric delivery of care for assessing breast cancer risk status and prevention options. This model can be replicated nationally by directing primary care physicians and women’s health practitioners to a risk-assessment questionnaire and referring high-risk women for appropriate preventative care. Given that these results show chemoprevention adherence rates doubled those seen nationally, perhaps techniques used within this VA pilot study may be adapted to decrease breast cancer incidence nationally.

Since the rate of PTSD among women veterans is triple the national average, we would expect adherence rates to be lower in our patient cohort. However, the multidisciplinary approach we used in this study (eg, 1:1 consultation with oncologist; genetic counseling referrals; mental health support available), may have improved adherence rates. Perhaps the high rates of PTSD seen in the VA patient population can be a useful way to explore patient adherence rates in those with mental illness and medical conditions.

Future research with a larger cohort may lead to greater insight into the correlation between PTSD and adherence to treatment. Exploring the connection between breast cancer, epigenetics, and specific military service-related exposures could be an area of analysis among this veteran population exhibiting increased breast cancer rates. VAMCs are situated in rural, suburban, and urban locations across the United States and offers a diverse socioeconomic and ethnic patient population for inclusion in clinical investigations. Women veterans make up a small subpopulation of women in the United States, but it is worth considering VA patients as an untapped resource for research collaboration.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Steven Sanchez and Marissa Vallette, PhD, Breast Health Research Group. This research project was approved by the James J. Peters VA Medical Center Quality Executive Committee and the Washington, DC VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board. This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs. This work did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. The past, present and future of women veterans. Published February 2017. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/women_veterans_2015_final.pdf.

2. Frayne SM, Carney DV, Bastian L, et al. The VA Women’s Health Practice-Based Research Network: amplifying women veterans’ voices in VA research. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S504-S509. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2476-3

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative, Women Veterans Health Strategic Health Care Group. Sourcebook: women veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 1: Sociodemographic characteristics and use of VHA care. Published December 2010. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2455

4. Bean-Mayberry B, Yano EM, Bayliss N, Navratil J, Weisman CS, Scholle SH. Federally funded comprehensive women’s health centers: leading innovation in women’s healthcare delivery. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16(9):1281-1290. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.0284

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics.VA utilization profile FY 2016. Published November 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/QuickFacts/VA_Utilization_Profile.PDF

6. Ekenga CC, Parks CG, Sandler DP. Chemical exposures in the workplace and breast cancer risk: a prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(7):1765-1774. doi:10.1002/ijc.29545

7. Rennix CP, Quinn MM, Amoroso PJ, Eisen EA, Wegman DH. Risk of breast cancer among enlisted Army women occupationally exposed to volatile organic compounds. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(3):157-167. doi:10.1002/ajim.20201

8. Ritz B. Cancer mortality among workers exposed to chemicals during uranium processing. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(7):556-566. doi:10.1097/00043764-199907000-00004

9. Zhu K, Devesa SS, Wu H, et al. Cancer incidence in the U.S. military population: comparison with rates from the SEER program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1740-1745. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0041

10. Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2013 Nov 10;31(32):4167]. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2327-2333. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0258

11. Greene, H. Cancer prevention, screening and early detection. In: Gobel BH, Triest-Robertson S, Vogel WH, eds. Advanced Oncology Nursing Certification Review and Resource Manual. 3rd ed. Oncology Nursing Society; 2016:1-34. https://www.ons.org/sites/default/files/publication_pdfs/2%20ADVPrac%20chapter%201.pdf

12. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Breast Cancer Risk Reduction. Version 1.2021 NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Updated March 24, 2021 Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_risk.pdf

13. US Preventive Services Task Force. Breast cancer: Medications use to reduce risk. Updated September 3, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/breast-cancer-medications-for-risk-reduction

14. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Medications to decrease the risk for breast cancer in women: recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(10):698-708. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00717

15. Boucher JE. Chemoprevention: an overview of pharmacologic agents and nursing considerations. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(3):350-353. doi:10.1188/18.CJON.350-353

16. Nichols HB, Stürmer T, Lee VS, et al. Breast cancer chemoprevention in an integrated health care setting. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2017;1:1-12. doi:10.1200/CCI.16.00059

17. Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis, Version 3.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(11):1362-1389. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2018.0083

18. Visvanathan K, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Use of pharmacologic interventions for breast cancer risk reduction: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2013 Dec 1;31(34):4383]. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2942-2962. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3122

19. Sealy-Jefferson S, Roseland ME, Cote ML, et al. rural-urban residence and stage at breast cancer diagnosis among postmenopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(2):276-283. doi:10.1089/jwh.2017.6884

20. Holder KA. Veterans in rural America: 2011-2015. Published January 25, 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/acs/acs-36.html

21. Owens WL, Gallagher TJ, Kincheloe MJ, Ruetten VL. Implementation in a large health system of a program to identify women at high risk for breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(2):85-88. doi:10.1200/JOP.2010.000107

2. Pivot X, Viguier J, Touboul C, et al. Breast cancer screening controversy: too much or not enough?. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24 Suppl:S73-S76. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000145

23. Bidassie B, Kovach A, Vallette MA, et al. Breast Cancer risk assessment and chemoprevention use among veterans affairs primary care providers: a national online survey. Mil Med. 2020;185(3-4):512-518. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz291

24. Brewster AM, Davidson NE, McCaskill-Stevens W. Chemoprevention for breast cancer: overcoming barriers to treatment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2012;85-90. doi:10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.152

25. Meyskens FL Jr, Curt GA, Brenner DE, et al. Regulatory approval of cancer risk-reducing (chemopreventive) drugs: moving what we have learned into the clinic. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(3):311-323. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0014

26. Tice JA, Kerlikowske K. Screening and prevention of breast cancer in primary care. Prim Care. 2009;36(3):533-558. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2009.04.003

27. Vogel VG. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer chemoprevention. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12(13):1874-1887. doi:10.2174/138945011798184164

28. Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial [published correction appears in JAMA. 2006 Dec 27;296(24):2926] [published correction appears in JAMA. 2007 Sep 5;298(9):973]. JAMA. 2006;295(23):2727-2741. doi:10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074

29. Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3230-3235. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-4715-9

30. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, et al. Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): an international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2014 Mar 22;383(9922):1040] [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017 Mar 11;389(10073):1010]. Lancet. 2014;383(9922):1041-1048. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62292-8

31. Bozovic-Spasojevic I, Azambuja E, McCaskill-Stevens W, Dinh P, Cardoso F. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(5):329-339. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.07.005

32. Gabriel EM, Jatoi I. Breast cancer chemoprevention. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12(2):223-228. doi:10.1586/era.11.206

33. Crew KD, Albain KS, Hershman DL, Unger JM, Lo SS. How do we increase uptake of tamoxifen and other anti-estrogens for breast cancer prevention?. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2017;3:20. Published 2017 May 19. doi:10.1038/s41523-017-0021-y

34. Ropka ME, Keim J, Philbrick JT. Patient decisions about breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):3090-3095. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.8077

35. Smith SG, Sestak I, Forster A, et al. Factors affecting uptake and adherence to breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(4):575-590. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdv590

36. Grann VR, Patel PR, Jacobson JS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of screening and prevention strategies among BRCA1/2-affected mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011 Feb;125(3):837-847. doi:10.1007/s10549-010-1043-4

37. Goss PE, Ingle JN, Alés-Martínez JE, et al. Exemestane for breast-cancer prevention in postmenopausal women [published correction appears in N Engl J Med. 2011 Oct 6;365(14):1361]. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(25):2381-2391. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1103507

38. Kmietowicz Z. Five in six women reject drugs that could reduce their risk of breast cancer. BMJ. 2015;351:h6650. Published 2015 Dec 8. doi:10.1136/bmj.h6650

39. Nelson HD, Fu R, Griffin JC, Nygren P, Smith ME, Humphrey L. Systematic review: comparative effectiveness of medications to reduce risk for primary breast cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):703-235. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00147

40. Dahabreh IJ, Wieland LS, Adam GP, Halladay C, Lau J, Trikalinos TA. Core needle and open surgery biopsy for diagnosis of breast lesions: an update to the 2009 report. Published September 2014. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK246878

41. National Cancer Institute. Genetics of breast and ovarian cancer (PDQ)—health profession version. Updated February 12, 2021. Accessed April 12, 2021. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/genetics/breast-and-ovarian/HealthProfessional

42. US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences The sister study. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://sisterstudy.niehs.nih.gov/english/NIEHS.htm

43. Tutt A, Ashworth A. Can genetic testing guide treatment in breast cancer?. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44(18):2774-2780. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.009

44. Katz SJ, Ward KC, Hamilton AS, et al. Gaps in receipt of clinically indicated genetic counseling after diagnosis of breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(12):1218-1224. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.76.2369

45. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. How common is PTSD in adults? Updated October 17, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_adults.asp

46. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. How common is PTSD in women? Updated October 16, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_women.asp

47. US Department of Veterans Affairs. PTSD: National Center for PTSD. How common is PTSD in veterans? Updated September 24, 2018. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/common/common_veterans.asp

48. Lindberg NM, Wellisch D. Anxiety and compliance among women at high risk for breast cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2001;23(4):298-303. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2304_9

49. DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2101-2107. doi:10.1001/archinte.160.14.2101

50. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR appendix: breast cancer rates among black women and white women. Updated October 13, 2016. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/statistics/trends_invasive.htm

51. Richardson LC, Henley SJ, Miller JW, Massetti G, Thomas CC. Patterns and trends in age-specific black-white differences in breast cancer incidence and mortality - United States, 1999-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(40):1093-1098. Published 2016 Oct 14. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6540a1

52. Brody JG, Moysich KB, Humblet O, Attfield KR, Beehler GP, Rudel RA. Environmental pollutants and breast cancer: epidemiologic studies. Cancer. 2007;109(12 Suppl):2667-2711. doi:10.1002/cncr.22655

53. Brophy JT, Keith MM, Watterson A, et al. Breast cancer risk in relation to occupations with exposure to carcinogens and endocrine disruptors: a Canadian case-control study. Environ Health. 2012;11:87. Published 2012 Nov 19. doi:10.1186/1476-069X-11-87

54. Labrèche F, Goldberg MS, Valois MF, Nadon L. Postmenopausal breast cancer and occupational exposures. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(4):263-269. doi:10.1136/oem.2009.049817

55. National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Interagency Breast Cancer & Environmental Research Coordinating Committee. Breast cancer and the environment: prioritizing prevention. Updated March 8, 2013. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.niehs.nih.gov/about/boards/ibcercc/index.cfm

56. Gail MH, Costantino JP, Pee D, et al. Projecting individualized absolute invasive breast cancer risk in African American women [published correction appears in J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Aug 6;100(15):1118] [published correction appears in J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008 Mar 5;100(5):373]. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99(23):1782-1792. doi:10.1093/jnci/djm223

57. Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, Moody-Ayers S. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):537-546. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x

58. Braunstein JB, Sherber NS, Schulman SP, Ding EL, Powe NR. Race, medical researcher distrust, perceived harm, and willingness to participate in cardiovascular prevention trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 2008;87(1):1-9. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e3181625d78

1. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. The past, present and future of women veterans. Published February 2017. Accessed April 28, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/specialreports/women_veterans_2015_final.pdf.

2. Frayne SM, Carney DV, Bastian L, et al. The VA Women’s Health Practice-Based Research Network: amplifying women veterans’ voices in VA research. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S504-S509. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2476-3

3. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative, Women Veterans Health Strategic Health Care Group. Sourcebook: women veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 1: Sociodemographic characteristics and use of VHA care. Published December 2010. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2455

4. Bean-Mayberry B, Yano EM, Bayliss N, Navratil J, Weisman CS, Scholle SH. Federally funded comprehensive women’s health centers: leading innovation in women’s healthcare delivery. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16(9):1281-1290. doi:10.1089/jwh.2006.0284

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics.VA utilization profile FY 2016. Published November 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/QuickFacts/VA_Utilization_Profile.PDF

6. Ekenga CC, Parks CG, Sandler DP. Chemical exposures in the workplace and breast cancer risk: a prospective cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2015;137(7):1765-1774. doi:10.1002/ijc.29545

7. Rennix CP, Quinn MM, Amoroso PJ, Eisen EA, Wegman DH. Risk of breast cancer among enlisted Army women occupationally exposed to volatile organic compounds. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48(3):157-167. doi:10.1002/ajim.20201

8. Ritz B. Cancer mortality among workers exposed to chemicals during uranium processing. J Occup Environ Med. 1999;41(7):556-566. doi:10.1097/00043764-199907000-00004

9. Zhu K, Devesa SS, Wu H, et al. Cancer incidence in the U.S. military population: comparison with rates from the SEER program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1740-1745. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0041

10. Freedman AN, Yu B, Gail MH, et al. Benefit/risk assessment for breast cancer chemoprevention with raloxifene or tamoxifen for women age 50 years or older [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2013 Nov 10;31(32):4167]. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(17):2327-2333. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.33.0258

11. Greene, H. Cancer prevention, screening and early detection. In: Gobel BH, Triest-Robertson S, Vogel WH, eds. Advanced Oncology Nursing Certification Review and Resource Manual. 3rd ed. Oncology Nursing Society; 2016:1-34. https://www.ons.org/sites/default/files/publication_pdfs/2%20ADVPrac%20chapter%201.pdf

12. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Breast Cancer Risk Reduction. Version 1.2021 NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Updated March 24, 2021 Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_risk.pdf

13. US Preventive Services Task Force. Breast cancer: Medications use to reduce risk. Updated September 3, 2019. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/breast-cancer-medications-for-risk-reduction

14. Moyer VA; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Medications to decrease the risk for breast cancer in women: recommendations from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(10):698-708. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-10-201311190-00717

15. Boucher JE. Chemoprevention: an overview of pharmacologic agents and nursing considerations. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2018;22(3):350-353. doi:10.1188/18.CJON.350-353

16. Nichols HB, Stürmer T, Lee VS, et al. Breast cancer chemoprevention in an integrated health care setting. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2017;1:1-12. doi:10.1200/CCI.16.00059

17. Bevers TB, Helvie M, Bonaccio E, et al. Breast cancer screening and diagnosis, Version 3.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018;16(11):1362-1389. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2018.0083

18. Visvanathan K, Hurley P, Bantug E, et al. Use of pharmacologic interventions for breast cancer risk reduction: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2013 Dec 1;31(34):4383]. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(23):2942-2962. doi:10.1200/JCO.2013.49.3122

19. Sealy-Jefferson S, Roseland ME, Cote ML, et al. rural-urban residence and stage at breast cancer diagnosis among postmenopausal women: The Women’s Health Initiative. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2019;28(2):276-283. doi:10.1089/jwh.2017.6884

20. Holder KA. Veterans in rural America: 2011-2015. Published January 25, 2017. Accessed April 12, 2021. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/acs/acs-36.html

21. Owens WL, Gallagher TJ, Kincheloe MJ, Ruetten VL. Implementation in a large health system of a program to identify women at high risk for breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(2):85-88. doi:10.1200/JOP.2010.000107

2. Pivot X, Viguier J, Touboul C, et al. Breast cancer screening controversy: too much or not enough?. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24 Suppl:S73-S76. doi:10.1097/CEJ.0000000000000145

23. Bidassie B, Kovach A, Vallette MA, et al. Breast Cancer risk assessment and chemoprevention use among veterans affairs primary care providers: a national online survey. Mil Med. 2020;185(3-4):512-518. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz291

24. Brewster AM, Davidson NE, McCaskill-Stevens W. Chemoprevention for breast cancer: overcoming barriers to treatment. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2012;85-90. doi:10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.152

25. Meyskens FL Jr, Curt GA, Brenner DE, et al. Regulatory approval of cancer risk-reducing (chemopreventive) drugs: moving what we have learned into the clinic. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(3):311-323. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0014

26. Tice JA, Kerlikowske K. Screening and prevention of breast cancer in primary care. Prim Care. 2009;36(3):533-558. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2009.04.003

27. Vogel VG. Selective estrogen receptor modulators and aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer chemoprevention. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12(13):1874-1887. doi:10.2174/138945011798184164

28. Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, et al. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes: the NSABP Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) P-2 trial [published correction appears in JAMA. 2006 Dec 27;296(24):2926] [published correction appears in JAMA. 2007 Sep 5;298(9):973]. JAMA. 2006;295(23):2727-2741. doi:10.1001/jama.295.23.joc60074

29. Pruthi S, Heisey RE, Bevers TB. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(10):3230-3235. doi:10.1245/s10434-015-4715-9

30. Cuzick J, Sestak I, Forbes JF, et al. Anastrozole for prevention of breast cancer in high-risk postmenopausal women (IBIS-II): an international, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2014 Mar 22;383(9922):1040] [published correction appears in Lancet. 2017 Mar 11;389(10073):1010]. Lancet. 2014;383(9922):1041-1048. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62292-8

31. Bozovic-Spasojevic I, Azambuja E, McCaskill-Stevens W, Dinh P, Cardoso F. Chemoprevention for breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38(5):329-339. doi:10.1016/j.ctrv.2011.07.005

32. Gabriel EM, Jatoi I. Breast cancer chemoprevention. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2012;12(2):223-228. doi:10.1586/era.11.206

33. Crew KD, Albain KS, Hershman DL, Unger JM, Lo SS. How do we increase uptake of tamoxifen and other anti-estrogens for breast cancer prevention?. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2017;3:20. Published 2017 May 19. doi:10.1038/s41523-017-0021-y

34. Ropka ME, Keim J, Philbrick JT. Patient decisions about breast cancer chemoprevention: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):3090-3095. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.8077