User login

Senators prep for Supreme Court strike down of federal subsidies

WASHINGTON – As the Supreme Court prepares to rule this summer on King v. Burwell, Republican Senators are offering plans should the court strike down subsidies to those who have bought health insurance via the federal exchange.

“I suspect that President Obama will create some kind of executive order to allow states to turn [federally run exchanges] into state exchanges, but the law says you can’t establish a state exchange past a certain date. That throws it back to Congress,” Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.) said at a press conference.

If there isn’t a way forward already in sight, Sen. Johnson said that he thinks the House Republican leadership will do nothing and tell President Obama, “This is a problem of your own making.”

To avoid that kind of posturing – as well as to convince the Supreme Court that a pro-King ruling would not be harmful to patients – Sen. Johnson said, “We need to have a plan in place.”

His bill, S. 1016, the Preserving Freedom and Choice in Health Care Act, at press time had 31 cosponsors, more than the handful of similar bill introduced in the Senate.

“I’m trying to keep this as simple as possible so it has the greatest chance of success,” Sen. Johnson said. “Let’s maintain the status quo, let’s not throw this whole health insurance market into chaos.”

Should the Supreme Court strike down King v. Burwell, S. 1016 would continue through August 2017 subsidies for patients who currently have insurance bought through a federal exchange – temporarily codifying the status quo and the Obama administration’s interpretation of the Affordable Care Act.

The bill also would repeal both the ACA’s individual mandate to have health insurance and its employer mandate to provide health insurance, as well as the essential health benefits package, which Rep. Johnson said is the reason why the ACA makes health insurance expensive.

“A 60-year-old guy like me has to buy an insurance plan that has maternity coverage. When the government mandates that, it establishes a base price, and it’s going to be higher than if you have an insurance marketplace that doesn’t have all that mandated coverage,” he said. “The way this has all been implemented, if you don’t get the subsidies, you’re paying a lot, and you don’t particularly like Obamacare.”

Time is ticking down for a contingency plan: The Supreme Court is expected to rule the first week of June.

“This may not be the final product,” Sen. Johnson said of his bill, which has yet to be scored by the Congressional Budget Office. “There may be some tweaks and some additions to it over the next week or so, and then whatever comes out of that process is what I think leadership will get behind.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – As the Supreme Court prepares to rule this summer on King v. Burwell, Republican Senators are offering plans should the court strike down subsidies to those who have bought health insurance via the federal exchange.

“I suspect that President Obama will create some kind of executive order to allow states to turn [federally run exchanges] into state exchanges, but the law says you can’t establish a state exchange past a certain date. That throws it back to Congress,” Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.) said at a press conference.

If there isn’t a way forward already in sight, Sen. Johnson said that he thinks the House Republican leadership will do nothing and tell President Obama, “This is a problem of your own making.”

To avoid that kind of posturing – as well as to convince the Supreme Court that a pro-King ruling would not be harmful to patients – Sen. Johnson said, “We need to have a plan in place.”

His bill, S. 1016, the Preserving Freedom and Choice in Health Care Act, at press time had 31 cosponsors, more than the handful of similar bill introduced in the Senate.

“I’m trying to keep this as simple as possible so it has the greatest chance of success,” Sen. Johnson said. “Let’s maintain the status quo, let’s not throw this whole health insurance market into chaos.”

Should the Supreme Court strike down King v. Burwell, S. 1016 would continue through August 2017 subsidies for patients who currently have insurance bought through a federal exchange – temporarily codifying the status quo and the Obama administration’s interpretation of the Affordable Care Act.

The bill also would repeal both the ACA’s individual mandate to have health insurance and its employer mandate to provide health insurance, as well as the essential health benefits package, which Rep. Johnson said is the reason why the ACA makes health insurance expensive.

“A 60-year-old guy like me has to buy an insurance plan that has maternity coverage. When the government mandates that, it establishes a base price, and it’s going to be higher than if you have an insurance marketplace that doesn’t have all that mandated coverage,” he said. “The way this has all been implemented, if you don’t get the subsidies, you’re paying a lot, and you don’t particularly like Obamacare.”

Time is ticking down for a contingency plan: The Supreme Court is expected to rule the first week of June.

“This may not be the final product,” Sen. Johnson said of his bill, which has yet to be scored by the Congressional Budget Office. “There may be some tweaks and some additions to it over the next week or so, and then whatever comes out of that process is what I think leadership will get behind.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

WASHINGTON – As the Supreme Court prepares to rule this summer on King v. Burwell, Republican Senators are offering plans should the court strike down subsidies to those who have bought health insurance via the federal exchange.

“I suspect that President Obama will create some kind of executive order to allow states to turn [federally run exchanges] into state exchanges, but the law says you can’t establish a state exchange past a certain date. That throws it back to Congress,” Sen. Ron Johnson (R-Wisc.) said at a press conference.

If there isn’t a way forward already in sight, Sen. Johnson said that he thinks the House Republican leadership will do nothing and tell President Obama, “This is a problem of your own making.”

To avoid that kind of posturing – as well as to convince the Supreme Court that a pro-King ruling would not be harmful to patients – Sen. Johnson said, “We need to have a plan in place.”

His bill, S. 1016, the Preserving Freedom and Choice in Health Care Act, at press time had 31 cosponsors, more than the handful of similar bill introduced in the Senate.

“I’m trying to keep this as simple as possible so it has the greatest chance of success,” Sen. Johnson said. “Let’s maintain the status quo, let’s not throw this whole health insurance market into chaos.”

Should the Supreme Court strike down King v. Burwell, S. 1016 would continue through August 2017 subsidies for patients who currently have insurance bought through a federal exchange – temporarily codifying the status quo and the Obama administration’s interpretation of the Affordable Care Act.

The bill also would repeal both the ACA’s individual mandate to have health insurance and its employer mandate to provide health insurance, as well as the essential health benefits package, which Rep. Johnson said is the reason why the ACA makes health insurance expensive.

“A 60-year-old guy like me has to buy an insurance plan that has maternity coverage. When the government mandates that, it establishes a base price, and it’s going to be higher than if you have an insurance marketplace that doesn’t have all that mandated coverage,” he said. “The way this has all been implemented, if you don’t get the subsidies, you’re paying a lot, and you don’t particularly like Obamacare.”

Time is ticking down for a contingency plan: The Supreme Court is expected to rule the first week of June.

“This may not be the final product,” Sen. Johnson said of his bill, which has yet to be scored by the Congressional Budget Office. “There may be some tweaks and some additions to it over the next week or so, and then whatever comes out of that process is what I think leadership will get behind.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

ICSR: Could a pediatric psychosis screen be on the horizon?

COLORADO SPRINGS – Results from a large, diverse community cohort study of genotyped youth could lead the way to early identification of those most likely to develop psychosis.

Data from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort study are now being analyzed in hopes that patterns emerging from an assessment of 9,421 Philadelphia-area children and young people aged 8-21 years will help researchers identify biomarkers that can be used to identify trajectories of mental illness before the point of clinical diagnosis.

The hope is that this will lead to the creation of a psychosis screening tool, Dr. Raquel E. Gur, one of the lead authors of the study and the Karl and Linda Rickels Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview at the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research.

Speaking about the difficulties of telling a family that their child is at risk for psychosis, she added: “It’s complex. The parents are often terrified, but it’s a reality. So what can we do to intervene early?” Earlier intervention can lead to better outcomes, she said.

Study participants were recruited from nearly 14,000 previously identified and genotyped children with varying levels of health and a range of medical conditions who were seen at pediatric facilities in Philadelphia and the surrounding region. The mean age of those studied was 14.2 years; 56% were white. Black children and young people represented a third of all study participants, and girls comprised slightly more than half.

In addition to current medical histories, Dr. Gur and her colleagues collected information on participants’ psychiatric and psychological histories using a comprehensive computerized tool to evaluate psychopathology domains such as mood and anxiety disorders. From this, they developed an identification matrix consisting of a strong general psychopathology factor and specific anxious-misery, fear, and behavior factors. They also developed a psychosis spectrum, embedded into the psychopathology screen, that included a general factor and three specific factors: ideas about special abilities/persecution, unusual thoughts/perceptions, and negative/disorganized symptoms. Positive threshold psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions were assessed with negative/disorganized symptoms typical of the prodromal phase of psychosis.

Dr. Gur said that, because of the absence of data on psychosis in preadolescence, one of their aims was to determine the prevalence of psychotic symptoms – similar to the prodromal symptoms typically displayed in adolescents – in the nearly 5,000 8- to 11-year-olds in the study. The results, she said, were that 3.7% reported psychotic symptoms, while an additional 12.3% reported significant positive subthreshold symptoms such as auditory disturbances and reality confusion. Of those who reported such symptoms, 2.3% reported being distressed by their negative symptoms, in part because they interfered with normal levels of functioning.

“Notably, the young participants were reporting much more than the parents were reporting,” Dr. Gur said. “This pattern shows you need to assess the children directly.”

Severe subthreshold symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, and auditory disturbances occurred at a level Dr. Gur said was consistent in studies of help-seeking individuals, although more than a third of the study participants had never discussed their distress with anyone.

“Nobody knew what these kids were going through,” she said. “We were the first mental health professionals to know. Not a school nurse, not clergy, nobody. This is a big burden for a young person.”

Even so, she said, these prodromal signs were not appearing in a vacuum. “What we commonly saw was depression, anxiety, difficulty with impulse control, substance use, and suicidal ideation. This is an important clinical period.”

Additional predictive factors for having symptoms of psychosis that Dr. Gur listed included being male and of European descent, cannabis use, reduced global functioning, and being distressed.

Being female had a high association with the anxious-misery factor and low association with the behavior factors.

The assessment’s behavior factor correlated negatively (0.21) with the overall accuracy of neurocognitive performance, particularly in executive and complex reasoning.

If it were possible to determine a child’s chronological age according to a composite score from his neurocognitive performance on the assessment, Dr. Gur said, this might mean it would be possible to determine who would benefit from intervention. Because the study looked for global psychopathologies, Dr. Gur theorized, “maybe all psychopathology is associated with cognitive performance and chronological age. It appears that having a subthreshold psychotic symptom infers vulnerability, so the expectation that somebody who is on the psychotic spectrum at age 16 would perform cognitively like a typically developing teen will not be met. This is something that can be tracked both individually and as a group. It is good clinical data that can be used to appraise child development, like height and weight.”

In the subset of study participants who underwent functional MRI, activation of working memory in the regions of the brain associated with executive function in those positively identified on the psychosis spectrum was lower than in those scored as developing normally (P < .05). Deficits in prefrontal cognitive activity also were noted in the group on the psychosis spectrum when compared with those not on the spectrum (P < .001), although no correlation was found with positive symptom severity. Also in the psychosis-spectrum group, there was elevated activity in the amygdala and other brain regions typically associated with fear, in response to being shown threatening facial expressions (P < .05). The response in the amygdala correlated with positive symptom severity (P = .01) but not with cognitive deficits.

Dr. Gur did not have any relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

COLORADO SPRINGS – Results from a large, diverse community cohort study of genotyped youth could lead the way to early identification of those most likely to develop psychosis.

Data from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort study are now being analyzed in hopes that patterns emerging from an assessment of 9,421 Philadelphia-area children and young people aged 8-21 years will help researchers identify biomarkers that can be used to identify trajectories of mental illness before the point of clinical diagnosis.

The hope is that this will lead to the creation of a psychosis screening tool, Dr. Raquel E. Gur, one of the lead authors of the study and the Karl and Linda Rickels Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview at the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research.

Speaking about the difficulties of telling a family that their child is at risk for psychosis, she added: “It’s complex. The parents are often terrified, but it’s a reality. So what can we do to intervene early?” Earlier intervention can lead to better outcomes, she said.

Study participants were recruited from nearly 14,000 previously identified and genotyped children with varying levels of health and a range of medical conditions who were seen at pediatric facilities in Philadelphia and the surrounding region. The mean age of those studied was 14.2 years; 56% were white. Black children and young people represented a third of all study participants, and girls comprised slightly more than half.

In addition to current medical histories, Dr. Gur and her colleagues collected information on participants’ psychiatric and psychological histories using a comprehensive computerized tool to evaluate psychopathology domains such as mood and anxiety disorders. From this, they developed an identification matrix consisting of a strong general psychopathology factor and specific anxious-misery, fear, and behavior factors. They also developed a psychosis spectrum, embedded into the psychopathology screen, that included a general factor and three specific factors: ideas about special abilities/persecution, unusual thoughts/perceptions, and negative/disorganized symptoms. Positive threshold psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions were assessed with negative/disorganized symptoms typical of the prodromal phase of psychosis.

Dr. Gur said that, because of the absence of data on psychosis in preadolescence, one of their aims was to determine the prevalence of psychotic symptoms – similar to the prodromal symptoms typically displayed in adolescents – in the nearly 5,000 8- to 11-year-olds in the study. The results, she said, were that 3.7% reported psychotic symptoms, while an additional 12.3% reported significant positive subthreshold symptoms such as auditory disturbances and reality confusion. Of those who reported such symptoms, 2.3% reported being distressed by their negative symptoms, in part because they interfered with normal levels of functioning.

“Notably, the young participants were reporting much more than the parents were reporting,” Dr. Gur said. “This pattern shows you need to assess the children directly.”

Severe subthreshold symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, and auditory disturbances occurred at a level Dr. Gur said was consistent in studies of help-seeking individuals, although more than a third of the study participants had never discussed their distress with anyone.

“Nobody knew what these kids were going through,” she said. “We were the first mental health professionals to know. Not a school nurse, not clergy, nobody. This is a big burden for a young person.”

Even so, she said, these prodromal signs were not appearing in a vacuum. “What we commonly saw was depression, anxiety, difficulty with impulse control, substance use, and suicidal ideation. This is an important clinical period.”

Additional predictive factors for having symptoms of psychosis that Dr. Gur listed included being male and of European descent, cannabis use, reduced global functioning, and being distressed.

Being female had a high association with the anxious-misery factor and low association with the behavior factors.

The assessment’s behavior factor correlated negatively (0.21) with the overall accuracy of neurocognitive performance, particularly in executive and complex reasoning.

If it were possible to determine a child’s chronological age according to a composite score from his neurocognitive performance on the assessment, Dr. Gur said, this might mean it would be possible to determine who would benefit from intervention. Because the study looked for global psychopathologies, Dr. Gur theorized, “maybe all psychopathology is associated with cognitive performance and chronological age. It appears that having a subthreshold psychotic symptom infers vulnerability, so the expectation that somebody who is on the psychotic spectrum at age 16 would perform cognitively like a typically developing teen will not be met. This is something that can be tracked both individually and as a group. It is good clinical data that can be used to appraise child development, like height and weight.”

In the subset of study participants who underwent functional MRI, activation of working memory in the regions of the brain associated with executive function in those positively identified on the psychosis spectrum was lower than in those scored as developing normally (P < .05). Deficits in prefrontal cognitive activity also were noted in the group on the psychosis spectrum when compared with those not on the spectrum (P < .001), although no correlation was found with positive symptom severity. Also in the psychosis-spectrum group, there was elevated activity in the amygdala and other brain regions typically associated with fear, in response to being shown threatening facial expressions (P < .05). The response in the amygdala correlated with positive symptom severity (P = .01) but not with cognitive deficits.

Dr. Gur did not have any relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

COLORADO SPRINGS – Results from a large, diverse community cohort study of genotyped youth could lead the way to early identification of those most likely to develop psychosis.

Data from the Philadelphia Neurodevelopmental Cohort study are now being analyzed in hopes that patterns emerging from an assessment of 9,421 Philadelphia-area children and young people aged 8-21 years will help researchers identify biomarkers that can be used to identify trajectories of mental illness before the point of clinical diagnosis.

The hope is that this will lead to the creation of a psychosis screening tool, Dr. Raquel E. Gur, one of the lead authors of the study and the Karl and Linda Rickels Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview at the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research.

Speaking about the difficulties of telling a family that their child is at risk for psychosis, she added: “It’s complex. The parents are often terrified, but it’s a reality. So what can we do to intervene early?” Earlier intervention can lead to better outcomes, she said.

Study participants were recruited from nearly 14,000 previously identified and genotyped children with varying levels of health and a range of medical conditions who were seen at pediatric facilities in Philadelphia and the surrounding region. The mean age of those studied was 14.2 years; 56% were white. Black children and young people represented a third of all study participants, and girls comprised slightly more than half.

In addition to current medical histories, Dr. Gur and her colleagues collected information on participants’ psychiatric and psychological histories using a comprehensive computerized tool to evaluate psychopathology domains such as mood and anxiety disorders. From this, they developed an identification matrix consisting of a strong general psychopathology factor and specific anxious-misery, fear, and behavior factors. They also developed a psychosis spectrum, embedded into the psychopathology screen, that included a general factor and three specific factors: ideas about special abilities/persecution, unusual thoughts/perceptions, and negative/disorganized symptoms. Positive threshold psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions were assessed with negative/disorganized symptoms typical of the prodromal phase of psychosis.

Dr. Gur said that, because of the absence of data on psychosis in preadolescence, one of their aims was to determine the prevalence of psychotic symptoms – similar to the prodromal symptoms typically displayed in adolescents – in the nearly 5,000 8- to 11-year-olds in the study. The results, she said, were that 3.7% reported psychotic symptoms, while an additional 12.3% reported significant positive subthreshold symptoms such as auditory disturbances and reality confusion. Of those who reported such symptoms, 2.3% reported being distressed by their negative symptoms, in part because they interfered with normal levels of functioning.

“Notably, the young participants were reporting much more than the parents were reporting,” Dr. Gur said. “This pattern shows you need to assess the children directly.”

Severe subthreshold symptoms such as delusions, hallucinations, and auditory disturbances occurred at a level Dr. Gur said was consistent in studies of help-seeking individuals, although more than a third of the study participants had never discussed their distress with anyone.

“Nobody knew what these kids were going through,” she said. “We were the first mental health professionals to know. Not a school nurse, not clergy, nobody. This is a big burden for a young person.”

Even so, she said, these prodromal signs were not appearing in a vacuum. “What we commonly saw was depression, anxiety, difficulty with impulse control, substance use, and suicidal ideation. This is an important clinical period.”

Additional predictive factors for having symptoms of psychosis that Dr. Gur listed included being male and of European descent, cannabis use, reduced global functioning, and being distressed.

Being female had a high association with the anxious-misery factor and low association with the behavior factors.

The assessment’s behavior factor correlated negatively (0.21) with the overall accuracy of neurocognitive performance, particularly in executive and complex reasoning.

If it were possible to determine a child’s chronological age according to a composite score from his neurocognitive performance on the assessment, Dr. Gur said, this might mean it would be possible to determine who would benefit from intervention. Because the study looked for global psychopathologies, Dr. Gur theorized, “maybe all psychopathology is associated with cognitive performance and chronological age. It appears that having a subthreshold psychotic symptom infers vulnerability, so the expectation that somebody who is on the psychotic spectrum at age 16 would perform cognitively like a typically developing teen will not be met. This is something that can be tracked both individually and as a group. It is good clinical data that can be used to appraise child development, like height and weight.”

In the subset of study participants who underwent functional MRI, activation of working memory in the regions of the brain associated with executive function in those positively identified on the psychosis spectrum was lower than in those scored as developing normally (P < .05). Deficits in prefrontal cognitive activity also were noted in the group on the psychosis spectrum when compared with those not on the spectrum (P < .001), although no correlation was found with positive symptom severity. Also in the psychosis-spectrum group, there was elevated activity in the amygdala and other brain regions typically associated with fear, in response to being shown threatening facial expressions (P < .05). The response in the amygdala correlated with positive symptom severity (P = .01) but not with cognitive deficits.

Dr. Gur did not have any relevant disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ICSR BIENNIAL MEETING

VIDEO: Smoking cessation efforts often enhanced by depression treatment

CHICAGO– Helping patients quit smoking, whether those with severe mental illness or comorbid depression, is an “excellent opportunity” for primary care doctors and psychiatrists to work together.

That’s according to Dr. Robert M. Anthenelli, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and director of the Pacific Treatment and Research Center there.

Depression and smoking are often comorbid in patients, and nearly half of all tobacco products consumed in the United States are done so by people with some form of a psychiatric or other substance use disorder. In this interview, recorded at the meeting, sponsored by Current Psychiatry and American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, Dr. Anthenelli discusses brain changes in tobacco use, why there is a link between smoking and mental illness, and what primary care physicians can do to help their patients who smoke. He also addresses whether complete cessation is essential to one’s well-being.

Dr. Anthenelli is a consultant to Pfizer and Arena Pharmaceuticals.

Current Psychiatry and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CHICAGO– Helping patients quit smoking, whether those with severe mental illness or comorbid depression, is an “excellent opportunity” for primary care doctors and psychiatrists to work together.

That’s according to Dr. Robert M. Anthenelli, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and director of the Pacific Treatment and Research Center there.

Depression and smoking are often comorbid in patients, and nearly half of all tobacco products consumed in the United States are done so by people with some form of a psychiatric or other substance use disorder. In this interview, recorded at the meeting, sponsored by Current Psychiatry and American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, Dr. Anthenelli discusses brain changes in tobacco use, why there is a link between smoking and mental illness, and what primary care physicians can do to help their patients who smoke. He also addresses whether complete cessation is essential to one’s well-being.

Dr. Anthenelli is a consultant to Pfizer and Arena Pharmaceuticals.

Current Psychiatry and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CHICAGO– Helping patients quit smoking, whether those with severe mental illness or comorbid depression, is an “excellent opportunity” for primary care doctors and psychiatrists to work together.

That’s according to Dr. Robert M. Anthenelli, a professor of psychiatry at the University of California, San Diego, and director of the Pacific Treatment and Research Center there.

Depression and smoking are often comorbid in patients, and nearly half of all tobacco products consumed in the United States are done so by people with some form of a psychiatric or other substance use disorder. In this interview, recorded at the meeting, sponsored by Current Psychiatry and American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, Dr. Anthenelli discusses brain changes in tobacco use, why there is a link between smoking and mental illness, and what primary care physicians can do to help their patients who smoke. He also addresses whether complete cessation is essential to one’s well-being.

Dr. Anthenelli is a consultant to Pfizer and Arena Pharmaceuticals.

Current Psychiatry and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PSYCHIATRY UPDATE 2015

VIDEO: New directions in treating adult ADHD

CHICAGO – What are the most important side effects to be aware of when medically treating adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? What are the most common comorbidities and how should they be treated? And what is the latest in nonpharmaceutical, as well as emerging medical treatment for what Dr. Anthony L. Rostain, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, says is not a disease but a disorder?

In this video interview, recorded at Psychiatry Update 2015, sponsored by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, Dr. Rostain shares what excites him most about emerging treatments for adult ADHD and what clinicians should be most concerned about when prescribing. He also discusses how ADHD overlaps with Tourette syndrome.

Current Psychiatry and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CHICAGO – What are the most important side effects to be aware of when medically treating adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? What are the most common comorbidities and how should they be treated? And what is the latest in nonpharmaceutical, as well as emerging medical treatment for what Dr. Anthony L. Rostain, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, says is not a disease but a disorder?

In this video interview, recorded at Psychiatry Update 2015, sponsored by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, Dr. Rostain shares what excites him most about emerging treatments for adult ADHD and what clinicians should be most concerned about when prescribing. He also discusses how ADHD overlaps with Tourette syndrome.

Current Psychiatry and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

CHICAGO – What are the most important side effects to be aware of when medically treating adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? What are the most common comorbidities and how should they be treated? And what is the latest in nonpharmaceutical, as well as emerging medical treatment for what Dr. Anthony L. Rostain, a professor of psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, says is not a disease but a disorder?

In this video interview, recorded at Psychiatry Update 2015, sponsored by Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, Dr. Rostain shares what excites him most about emerging treatments for adult ADHD and what clinicians should be most concerned about when prescribing. He also discusses how ADHD overlaps with Tourette syndrome.

Current Psychiatry and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT PSYCHIATRY UPDATE 2015

Mortality, outcomes good in AAA repair in octogenarians

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ.– Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in patients 80 years and older can be performed safely and with good medium-term survival rates, a prospective single-site study has shown.

Perioperative mortality in elective and emergent AAA repair for octogenarians was 2% and 35%, respectively, with a median survival rate of 19 months in both groups.

According to these data, “Patients shouldn’t be turned down for aneurysm repair on the basis of their age alone,” Dr. Christopher M. Lamb, a vascular surgery fellow at the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, said during a presentation at this year’s Southern Association for Vascular Surgery annual meeting.

“However, whether we should be doing these procedures is a different question, and I don’t think these data allow us to answer that question properly.”Dr. Lamb and his colleagues reviewed the records of 847 consecutive patients aged 80 years or older, seen between April 2005 and February 2014 for any type of AAA repair. Cases were sorted according to whether they were elective, ruptured, or urgent but unruptured. A total of 226 patients met the study’s age criteria; there were nearly seven men for every woman, all with a median age of 83 years. Of the elective AAA repair arm of the study, 131 patients (116 men) with a median age of 82 years had an endovascular repair, while the rest underwent open surgical repair. The combined 30-day mortality rate for these patients was 2.3%, with no significant difference between either the endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or the open surgical repair (OSR) patients (1.9% vs. 4.2%; P = .458). The median survival of all elective repair patients was 19 months (interquartile range, 10-35), with no difference seen between the two groups (P = .113)Of the 65 patients (53 men) with ruptured AAA, the median age was 83 years. A third had open repair (32.3%), while the rest had EVAR. The combined 30-day mortality rate was 35.4% but was significantly higher after OSR (52.4% vs. 27.3%; P = .048). The median survival rate was 6 months (IQR, 6-42) when 30-day mortality rates were excluded. The median survival rates in patients who lived longer than 30 days was significantly higher in OSR patients (42.5 months vs. 11 months; P = .019).

Of the 23 men and 7 women with symptomatic but unruptured AAA, all but 1 had EVAR. At 30 days, there was one diverticular perforation–related postoperative death in the EVAR group, which had a median survival rate of 29 months. There being only a single patient in the OSR group obviated a comparative median survival rate analysis.

A subanalysis of the final 20 months of the study showed that 41% of octogenarians seeking any type of AAA repair at the site were rejected (48 rejections vs. 69 repairs). Those who were rejected for repair tended to be older, with a median age of 86 years vs. 83 years for patients who underwent repair (P = .0004).

Dr. Lamb noted that although the findings demonstrate acceptable overall safety rates for the entire cohort, without a control group of patients that did not have AAA repair, it would be hard to draw a definite conclusion about the utility of the findings, and that more data were warranted; however, the potential for limited long-term survival with what previous reports have suggested may include “a reduced quality of life for a good part of it, possibly raises the question that these patients should be treated conservatively, more often.”

The rejection rate data prompted the presentation’s discussant, Dr. William D. Jordan Jr., section chief of vascular surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the presentation’s discussant, to challenge the findings and asked whether a single surgeon selected the patients.

“You said there is not a selection bias in your study, but I beg to differ. Perhaps all these kinds of studies have a selection bias, and I believe they should. We should select the appropriate patients for the appropriate procedure at the appropriate time, with the appropriate expectation of outcome. Bias in this setting may be seen as good,” Dr. Jordan said.Dr. Lamb responded that the treatment algorithm at the site for all patients with a confirmed AAA of 5.5 cm or greater included CT imaging that is reviewed by a multidisciplinary team comprising vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists, who then evaluated the patients according to their physiology and anatomy, as well as their comorbidities, with the intention that whenever possible, EVAR rather than open repair would be performed.

As to whether there was a bias toward not repairing AAA in older patients, Dr. Lamb said it was incumbent on any health system to evaluate a procedure’s cost-effectiveness, but that, “the life expectancy of a vascular patient is often more limited than I think we’d like to believe ... we don’t know what the natural history of these patients’ life expectancy is. We don’t know from these data what the cause of death was, but anecdotally, we didn’t see hundreds of patients return with ruptured aneurysms after an EVAR.”

“I would truly like to see how many [of these patients] who make it out of the hospital return to normal living within 6 months,” Dr. Samuel R. Money, chair of surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., said in an interview following the presentation. “At some point, the question becomes ‘Can we afford to spend $100,000 dollars to keep a 90-year-old patient alive for 6 more months?’ Can this society sustain the cost of that?”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

This discussion is provocative and raises some interesting points. Obviously cost-effectiveness considerations are important, and our country does not have unlimited funds to spend on medical care. And perhaps there are some elderly and frail individuals who should not have their AAAs repaired electively because the risk of rupture during the patients’ remaining months or years of life is small.

This is particularly true if the patient’s AAA is less than 7 cm and his or her anatomy and condition are unsuitable for an easy repair. However, if the AAA is large and threatening, and the patient has the possibility of living several years, elective repair is justified and reasonable – especially if it can be accomplished endovascularly. As someone who is near 80 [years old], I could not feel more strongly about this, and I would maintain this view if I were near 90 and healthy.

|

Dr. Frank J. Veith |

I hold the same view even more strongly regarding a ruptured AAA. In this setting, the alternative management is nontreatment, which is uniformly fatal. The common term “palliative treatment” for such nontreatment is a misleading misnomer. No sane, reasonably healthy elderly patient would knowingly choose such nontreatment when a good alternative with well over an even chance of living a lot longer is offered. That good alternative – again especially if it can be performed endovascularly – should be offered, and our health system should pay for it and compensate by saving money on unnecessary SFA [superficial femoral artery] stents and carotid procedures.

Dr. Frank J. Veith is professor of surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic and is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

This discussion is provocative and raises some interesting points. Obviously cost-effectiveness considerations are important, and our country does not have unlimited funds to spend on medical care. And perhaps there are some elderly and frail individuals who should not have their AAAs repaired electively because the risk of rupture during the patients’ remaining months or years of life is small.

This is particularly true if the patient’s AAA is less than 7 cm and his or her anatomy and condition are unsuitable for an easy repair. However, if the AAA is large and threatening, and the patient has the possibility of living several years, elective repair is justified and reasonable – especially if it can be accomplished endovascularly. As someone who is near 80 [years old], I could not feel more strongly about this, and I would maintain this view if I were near 90 and healthy.

|

Dr. Frank J. Veith |

I hold the same view even more strongly regarding a ruptured AAA. In this setting, the alternative management is nontreatment, which is uniformly fatal. The common term “palliative treatment” for such nontreatment is a misleading misnomer. No sane, reasonably healthy elderly patient would knowingly choose such nontreatment when a good alternative with well over an even chance of living a lot longer is offered. That good alternative – again especially if it can be performed endovascularly – should be offered, and our health system should pay for it and compensate by saving money on unnecessary SFA [superficial femoral artery] stents and carotid procedures.

Dr. Frank J. Veith is professor of surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic and is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

This discussion is provocative and raises some interesting points. Obviously cost-effectiveness considerations are important, and our country does not have unlimited funds to spend on medical care. And perhaps there are some elderly and frail individuals who should not have their AAAs repaired electively because the risk of rupture during the patients’ remaining months or years of life is small.

This is particularly true if the patient’s AAA is less than 7 cm and his or her anatomy and condition are unsuitable for an easy repair. However, if the AAA is large and threatening, and the patient has the possibility of living several years, elective repair is justified and reasonable – especially if it can be accomplished endovascularly. As someone who is near 80 [years old], I could not feel more strongly about this, and I would maintain this view if I were near 90 and healthy.

|

Dr. Frank J. Veith |

I hold the same view even more strongly regarding a ruptured AAA. In this setting, the alternative management is nontreatment, which is uniformly fatal. The common term “palliative treatment” for such nontreatment is a misleading misnomer. No sane, reasonably healthy elderly patient would knowingly choose such nontreatment when a good alternative with well over an even chance of living a lot longer is offered. That good alternative – again especially if it can be performed endovascularly – should be offered, and our health system should pay for it and compensate by saving money on unnecessary SFA [superficial femoral artery] stents and carotid procedures.

Dr. Frank J. Veith is professor of surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic and is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ.– Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in patients 80 years and older can be performed safely and with good medium-term survival rates, a prospective single-site study has shown.

Perioperative mortality in elective and emergent AAA repair for octogenarians was 2% and 35%, respectively, with a median survival rate of 19 months in both groups.

According to these data, “Patients shouldn’t be turned down for aneurysm repair on the basis of their age alone,” Dr. Christopher M. Lamb, a vascular surgery fellow at the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, said during a presentation at this year’s Southern Association for Vascular Surgery annual meeting.

“However, whether we should be doing these procedures is a different question, and I don’t think these data allow us to answer that question properly.”Dr. Lamb and his colleagues reviewed the records of 847 consecutive patients aged 80 years or older, seen between April 2005 and February 2014 for any type of AAA repair. Cases were sorted according to whether they were elective, ruptured, or urgent but unruptured. A total of 226 patients met the study’s age criteria; there were nearly seven men for every woman, all with a median age of 83 years. Of the elective AAA repair arm of the study, 131 patients (116 men) with a median age of 82 years had an endovascular repair, while the rest underwent open surgical repair. The combined 30-day mortality rate for these patients was 2.3%, with no significant difference between either the endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or the open surgical repair (OSR) patients (1.9% vs. 4.2%; P = .458). The median survival of all elective repair patients was 19 months (interquartile range, 10-35), with no difference seen between the two groups (P = .113)Of the 65 patients (53 men) with ruptured AAA, the median age was 83 years. A third had open repair (32.3%), while the rest had EVAR. The combined 30-day mortality rate was 35.4% but was significantly higher after OSR (52.4% vs. 27.3%; P = .048). The median survival rate was 6 months (IQR, 6-42) when 30-day mortality rates were excluded. The median survival rates in patients who lived longer than 30 days was significantly higher in OSR patients (42.5 months vs. 11 months; P = .019).

Of the 23 men and 7 women with symptomatic but unruptured AAA, all but 1 had EVAR. At 30 days, there was one diverticular perforation–related postoperative death in the EVAR group, which had a median survival rate of 29 months. There being only a single patient in the OSR group obviated a comparative median survival rate analysis.

A subanalysis of the final 20 months of the study showed that 41% of octogenarians seeking any type of AAA repair at the site were rejected (48 rejections vs. 69 repairs). Those who were rejected for repair tended to be older, with a median age of 86 years vs. 83 years for patients who underwent repair (P = .0004).

Dr. Lamb noted that although the findings demonstrate acceptable overall safety rates for the entire cohort, without a control group of patients that did not have AAA repair, it would be hard to draw a definite conclusion about the utility of the findings, and that more data were warranted; however, the potential for limited long-term survival with what previous reports have suggested may include “a reduced quality of life for a good part of it, possibly raises the question that these patients should be treated conservatively, more often.”

The rejection rate data prompted the presentation’s discussant, Dr. William D. Jordan Jr., section chief of vascular surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the presentation’s discussant, to challenge the findings and asked whether a single surgeon selected the patients.

“You said there is not a selection bias in your study, but I beg to differ. Perhaps all these kinds of studies have a selection bias, and I believe they should. We should select the appropriate patients for the appropriate procedure at the appropriate time, with the appropriate expectation of outcome. Bias in this setting may be seen as good,” Dr. Jordan said.Dr. Lamb responded that the treatment algorithm at the site for all patients with a confirmed AAA of 5.5 cm or greater included CT imaging that is reviewed by a multidisciplinary team comprising vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists, who then evaluated the patients according to their physiology and anatomy, as well as their comorbidities, with the intention that whenever possible, EVAR rather than open repair would be performed.

As to whether there was a bias toward not repairing AAA in older patients, Dr. Lamb said it was incumbent on any health system to evaluate a procedure’s cost-effectiveness, but that, “the life expectancy of a vascular patient is often more limited than I think we’d like to believe ... we don’t know what the natural history of these patients’ life expectancy is. We don’t know from these data what the cause of death was, but anecdotally, we didn’t see hundreds of patients return with ruptured aneurysms after an EVAR.”

“I would truly like to see how many [of these patients] who make it out of the hospital return to normal living within 6 months,” Dr. Samuel R. Money, chair of surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., said in an interview following the presentation. “At some point, the question becomes ‘Can we afford to spend $100,000 dollars to keep a 90-year-old patient alive for 6 more months?’ Can this society sustain the cost of that?”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

SCOTTSDALE, ARIZ.– Abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in patients 80 years and older can be performed safely and with good medium-term survival rates, a prospective single-site study has shown.

Perioperative mortality in elective and emergent AAA repair for octogenarians was 2% and 35%, respectively, with a median survival rate of 19 months in both groups.

According to these data, “Patients shouldn’t be turned down for aneurysm repair on the basis of their age alone,” Dr. Christopher M. Lamb, a vascular surgery fellow at the University of California Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, said during a presentation at this year’s Southern Association for Vascular Surgery annual meeting.

“However, whether we should be doing these procedures is a different question, and I don’t think these data allow us to answer that question properly.”Dr. Lamb and his colleagues reviewed the records of 847 consecutive patients aged 80 years or older, seen between April 2005 and February 2014 for any type of AAA repair. Cases were sorted according to whether they were elective, ruptured, or urgent but unruptured. A total of 226 patients met the study’s age criteria; there were nearly seven men for every woman, all with a median age of 83 years. Of the elective AAA repair arm of the study, 131 patients (116 men) with a median age of 82 years had an endovascular repair, while the rest underwent open surgical repair. The combined 30-day mortality rate for these patients was 2.3%, with no significant difference between either the endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) or the open surgical repair (OSR) patients (1.9% vs. 4.2%; P = .458). The median survival of all elective repair patients was 19 months (interquartile range, 10-35), with no difference seen between the two groups (P = .113)Of the 65 patients (53 men) with ruptured AAA, the median age was 83 years. A third had open repair (32.3%), while the rest had EVAR. The combined 30-day mortality rate was 35.4% but was significantly higher after OSR (52.4% vs. 27.3%; P = .048). The median survival rate was 6 months (IQR, 6-42) when 30-day mortality rates were excluded. The median survival rates in patients who lived longer than 30 days was significantly higher in OSR patients (42.5 months vs. 11 months; P = .019).

Of the 23 men and 7 women with symptomatic but unruptured AAA, all but 1 had EVAR. At 30 days, there was one diverticular perforation–related postoperative death in the EVAR group, which had a median survival rate of 29 months. There being only a single patient in the OSR group obviated a comparative median survival rate analysis.

A subanalysis of the final 20 months of the study showed that 41% of octogenarians seeking any type of AAA repair at the site were rejected (48 rejections vs. 69 repairs). Those who were rejected for repair tended to be older, with a median age of 86 years vs. 83 years for patients who underwent repair (P = .0004).

Dr. Lamb noted that although the findings demonstrate acceptable overall safety rates for the entire cohort, without a control group of patients that did not have AAA repair, it would be hard to draw a definite conclusion about the utility of the findings, and that more data were warranted; however, the potential for limited long-term survival with what previous reports have suggested may include “a reduced quality of life for a good part of it, possibly raises the question that these patients should be treated conservatively, more often.”

The rejection rate data prompted the presentation’s discussant, Dr. William D. Jordan Jr., section chief of vascular surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and the presentation’s discussant, to challenge the findings and asked whether a single surgeon selected the patients.

“You said there is not a selection bias in your study, but I beg to differ. Perhaps all these kinds of studies have a selection bias, and I believe they should. We should select the appropriate patients for the appropriate procedure at the appropriate time, with the appropriate expectation of outcome. Bias in this setting may be seen as good,” Dr. Jordan said.Dr. Lamb responded that the treatment algorithm at the site for all patients with a confirmed AAA of 5.5 cm or greater included CT imaging that is reviewed by a multidisciplinary team comprising vascular surgeons and interventional radiologists, who then evaluated the patients according to their physiology and anatomy, as well as their comorbidities, with the intention that whenever possible, EVAR rather than open repair would be performed.

As to whether there was a bias toward not repairing AAA in older patients, Dr. Lamb said it was incumbent on any health system to evaluate a procedure’s cost-effectiveness, but that, “the life expectancy of a vascular patient is often more limited than I think we’d like to believe ... we don’t know what the natural history of these patients’ life expectancy is. We don’t know from these data what the cause of death was, but anecdotally, we didn’t see hundreds of patients return with ruptured aneurysms after an EVAR.”

“I would truly like to see how many [of these patients] who make it out of the hospital return to normal living within 6 months,” Dr. Samuel R. Money, chair of surgery at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Ariz., said in an interview following the presentation. “At some point, the question becomes ‘Can we afford to spend $100,000 dollars to keep a 90-year-old patient alive for 6 more months?’ Can this society sustain the cost of that?”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

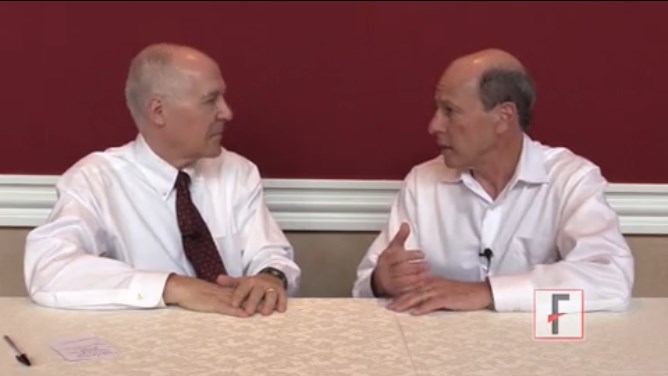

VIDEO: Interventions improve social functioning in schizophrenia

COLORADO SPRINGS – What kinds of early social interventions and cognitive remediation work to improve outcomes in schizophrenia? What’s the importance of stable medication regimens and psychoeducation for family members? Learn the answers to these questions and more in this discussion between Dr. S. Charles Schulz, head of the department of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and his colleague Michael F. Green, Ph.D., who is head of the Green Lab at the University of California, Los Angeles, which was recorded at the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

COLORADO SPRINGS – What kinds of early social interventions and cognitive remediation work to improve outcomes in schizophrenia? What’s the importance of stable medication regimens and psychoeducation for family members? Learn the answers to these questions and more in this discussion between Dr. S. Charles Schulz, head of the department of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and his colleague Michael F. Green, Ph.D., who is head of the Green Lab at the University of California, Los Angeles, which was recorded at the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

COLORADO SPRINGS – What kinds of early social interventions and cognitive remediation work to improve outcomes in schizophrenia? What’s the importance of stable medication regimens and psychoeducation for family members? Learn the answers to these questions and more in this discussion between Dr. S. Charles Schulz, head of the department of psychiatry at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, and his colleague Michael F. Green, Ph.D., who is head of the Green Lab at the University of California, Los Angeles, which was recorded at the International Congress on Schizophrenia Research.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ICSR BIENNIAL MEETING

Try exposure therapy, SSRIs for PTSD

LAS VEGAS– There is no cure for posttraumatic stress disorder, but helping its sufferers reduce symptoms, improve resistance, and achieve a better quality of life is possible.

“We have no idea what the best treatments are for PTSD,” Dr. Charles B. Nemeroff, the Leonard M. Miller Professor, and chairman of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Miami, told an audience at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

Whether to rely upon psychosocial or pharmacologic interventions, or a combination of the two, to help shift PTSD from a debilitating condition into a manageable, chronic one, it is important to understand PTSD as a brain disease. “To accurately treat PTSD, consider it within a neurobiological context,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “Ordinarily, the brain is evolved to deal with stress, but it can be compromised.”

In chronic PTSD, brain studies have shown a noted shrinkage in the hippocampus, contributing to memory impairment, similar to the reduced hippocampal volume in child-abuse victims. Additionally, cortical function in the brain is affected in PTSD, creating difficulty with exercising judgment and good decision making.

“One way to think about PTSD is that the cortex is unable to reign in the limbic system,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “The hippocampus is impaired, the amygdala is hyperactive, and there is a tremendous emotional drive, so the ‘thinking’ part of the brain can’t [overcome] the emotional, reptilian brain.”

The result is that a person remains stuck in a hyperaroused state. “We know that the neurobiological basis for PTSD involves a prolonged, vigilant response to stress [involving] a multitude of brain circuits ... and of course the sympathetic nervous system and the pituitary and adrenal systems,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Beyond brain changes, a genetic predisposition to PTSD accounts for a third of all cases, while an additional one-third are attributable to additional biological risk factors, according to Dr. Nemeroff (Nature 2011;470:492-7).

Just as with all anxiety-related disorders, women are more PTSD susceptible than are men. One of the “few things everybody agrees on,” Dr. Nemeroff said, is that early-life trauma such as neglect or abuse is a definite risk factor for PTSD, in part because early-life stress is thought to permanently program the brain regions involved in stress- and anxiety-mediation. Add to that, any adult level trauma, and they two “synergize. The more adult trauma coupled with early childhood abuse or neglect, the higher the level of PTSD.”

Meanwhile, poor social support, especially after the occurrence of a traumatic event, is a traditional prognosticator of poor recovery from PTSD, as are a family history of mood disorders, lower I.Q. and education, and experiencing other stressors the year before or after a traumatic event.

Dr. Nemeroff said that although the goals of treatment are reduced core symptoms, improved quality of life and function, strength, and resilience against subsequent stress, “the sad fact of the matter is that we don’t have a clue what the best treatment is, because we have no predictors of treatment response for PTSD.”

The most common treatments for PTSD are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although the best data available suggest that prolonged imaginal exposure therapy is the most effective, Dr. Nemeroff said. It can be provided either virtually or in person, and includes breathing techniques, psychoeducation, and cognitive therapy. The Institute of Medicine gives exposure therapy its highest rating for scientific evidence, said Dr. Nemeroff, who is a board member of the institute.

Pharmacologic treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration for PTSD treatment include sertraline and paroxetine, although other antidepressants can be prescribed off-label to some effect.

With sertraline, there is a “pretty low bar” of efficacy, according to Dr. Nemeroff, since only a 30% improvement in symptoms was recorded in 60% of study participants for FDA approval. It’s important to remember the treatment-response in PTSD is much slower than in major depression, Dr. Nemeroff said. “It can take as much as 9 months, so don’t give up.”

Combining sertraline with prolonged exposure therapy is even more effective, he said (J. Trauma Stress 2006;19:625-38). Meanwhile, other data show what paroxetine alone performed better than placebo, but the data are mixed for the drug in combination with prolonged exposure therapy (Am. J. Psychiatry 2012;169:80-8), (J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008;69:400-5), (J. Clin. Neurosci. 2008;62:646-52), and (Am. J. Psychiatry 2001;158:1982-8).

Dr. Nemeroff said lately, he has been treating PTSD patients with venlafaxine 450 mg, which is much higher than the usual dose of about 220 mg, with “considerably good results” (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006;63:1158-65).

Improvements in memory and hippocampal volume generally are found with SSRI treatments, as well as reductions in symptom severity, according to Dr. Nemeroff.

For PTSD patients who are struggling with insomnia and other sleep-related problems, Dr. Nemeroff said prazosin has been “phenomenal,” especially in reducing nightmares (Am. J. Psychiatry 2013;170:1003-10).

One drug class to avoid using with PTSD patients is benzodiazepines, he said. “Every study has shown that benzodiazepines in PTSD do not work, and they come with a high rate of substance abuse in this population.”

*Dr. Nemeroff disclosed that he receives research and grant support from the National Institutes of Health. He also serves as a consultant for several companies, including Xhale, Takeda, SK Pharma, Shire, Roche, Lilly, Allergan, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Development America, Taisho Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck, Prismic Pharmaceuticals, and Clintara LLC. He is a stockholder in Xhale, Celgene, Seattle Genetics, Abbvie, Titan Pharmaceuticals, and OPKO Health.

In addition, he holds financial/proprietary interest in patents for method/devices for the transdermal delivery of lithium and for a method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy.

*Correction, 4/10/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated Dr. Nemeroff's disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

LAS VEGAS– There is no cure for posttraumatic stress disorder, but helping its sufferers reduce symptoms, improve resistance, and achieve a better quality of life is possible.

“We have no idea what the best treatments are for PTSD,” Dr. Charles B. Nemeroff, the Leonard M. Miller Professor, and chairman of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Miami, told an audience at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

Whether to rely upon psychosocial or pharmacologic interventions, or a combination of the two, to help shift PTSD from a debilitating condition into a manageable, chronic one, it is important to understand PTSD as a brain disease. “To accurately treat PTSD, consider it within a neurobiological context,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “Ordinarily, the brain is evolved to deal with stress, but it can be compromised.”

In chronic PTSD, brain studies have shown a noted shrinkage in the hippocampus, contributing to memory impairment, similar to the reduced hippocampal volume in child-abuse victims. Additionally, cortical function in the brain is affected in PTSD, creating difficulty with exercising judgment and good decision making.

“One way to think about PTSD is that the cortex is unable to reign in the limbic system,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “The hippocampus is impaired, the amygdala is hyperactive, and there is a tremendous emotional drive, so the ‘thinking’ part of the brain can’t [overcome] the emotional, reptilian brain.”

The result is that a person remains stuck in a hyperaroused state. “We know that the neurobiological basis for PTSD involves a prolonged, vigilant response to stress [involving] a multitude of brain circuits ... and of course the sympathetic nervous system and the pituitary and adrenal systems,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Beyond brain changes, a genetic predisposition to PTSD accounts for a third of all cases, while an additional one-third are attributable to additional biological risk factors, according to Dr. Nemeroff (Nature 2011;470:492-7).

Just as with all anxiety-related disorders, women are more PTSD susceptible than are men. One of the “few things everybody agrees on,” Dr. Nemeroff said, is that early-life trauma such as neglect or abuse is a definite risk factor for PTSD, in part because early-life stress is thought to permanently program the brain regions involved in stress- and anxiety-mediation. Add to that, any adult level trauma, and they two “synergize. The more adult trauma coupled with early childhood abuse or neglect, the higher the level of PTSD.”

Meanwhile, poor social support, especially after the occurrence of a traumatic event, is a traditional prognosticator of poor recovery from PTSD, as are a family history of mood disorders, lower I.Q. and education, and experiencing other stressors the year before or after a traumatic event.

Dr. Nemeroff said that although the goals of treatment are reduced core symptoms, improved quality of life and function, strength, and resilience against subsequent stress, “the sad fact of the matter is that we don’t have a clue what the best treatment is, because we have no predictors of treatment response for PTSD.”

The most common treatments for PTSD are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although the best data available suggest that prolonged imaginal exposure therapy is the most effective, Dr. Nemeroff said. It can be provided either virtually or in person, and includes breathing techniques, psychoeducation, and cognitive therapy. The Institute of Medicine gives exposure therapy its highest rating for scientific evidence, said Dr. Nemeroff, who is a board member of the institute.

Pharmacologic treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration for PTSD treatment include sertraline and paroxetine, although other antidepressants can be prescribed off-label to some effect.

With sertraline, there is a “pretty low bar” of efficacy, according to Dr. Nemeroff, since only a 30% improvement in symptoms was recorded in 60% of study participants for FDA approval. It’s important to remember the treatment-response in PTSD is much slower than in major depression, Dr. Nemeroff said. “It can take as much as 9 months, so don’t give up.”

Combining sertraline with prolonged exposure therapy is even more effective, he said (J. Trauma Stress 2006;19:625-38). Meanwhile, other data show what paroxetine alone performed better than placebo, but the data are mixed for the drug in combination with prolonged exposure therapy (Am. J. Psychiatry 2012;169:80-8), (J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008;69:400-5), (J. Clin. Neurosci. 2008;62:646-52), and (Am. J. Psychiatry 2001;158:1982-8).

Dr. Nemeroff said lately, he has been treating PTSD patients with venlafaxine 450 mg, which is much higher than the usual dose of about 220 mg, with “considerably good results” (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006;63:1158-65).

Improvements in memory and hippocampal volume generally are found with SSRI treatments, as well as reductions in symptom severity, according to Dr. Nemeroff.

For PTSD patients who are struggling with insomnia and other sleep-related problems, Dr. Nemeroff said prazosin has been “phenomenal,” especially in reducing nightmares (Am. J. Psychiatry 2013;170:1003-10).

One drug class to avoid using with PTSD patients is benzodiazepines, he said. “Every study has shown that benzodiazepines in PTSD do not work, and they come with a high rate of substance abuse in this population.”

*Dr. Nemeroff disclosed that he receives research and grant support from the National Institutes of Health. He also serves as a consultant for several companies, including Xhale, Takeda, SK Pharma, Shire, Roche, Lilly, Allergan, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Development America, Taisho Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck, Prismic Pharmaceuticals, and Clintara LLC. He is a stockholder in Xhale, Celgene, Seattle Genetics, Abbvie, Titan Pharmaceuticals, and OPKO Health.

In addition, he holds financial/proprietary interest in patents for method/devices for the transdermal delivery of lithium and for a method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy.

*Correction, 4/10/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated Dr. Nemeroff's disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

LAS VEGAS– There is no cure for posttraumatic stress disorder, but helping its sufferers reduce symptoms, improve resistance, and achieve a better quality of life is possible.

“We have no idea what the best treatments are for PTSD,” Dr. Charles B. Nemeroff, the Leonard M. Miller Professor, and chairman of the department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Miami, told an audience at the annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

Whether to rely upon psychosocial or pharmacologic interventions, or a combination of the two, to help shift PTSD from a debilitating condition into a manageable, chronic one, it is important to understand PTSD as a brain disease. “To accurately treat PTSD, consider it within a neurobiological context,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “Ordinarily, the brain is evolved to deal with stress, but it can be compromised.”

In chronic PTSD, brain studies have shown a noted shrinkage in the hippocampus, contributing to memory impairment, similar to the reduced hippocampal volume in child-abuse victims. Additionally, cortical function in the brain is affected in PTSD, creating difficulty with exercising judgment and good decision making.

“One way to think about PTSD is that the cortex is unable to reign in the limbic system,” Dr. Nemeroff said. “The hippocampus is impaired, the amygdala is hyperactive, and there is a tremendous emotional drive, so the ‘thinking’ part of the brain can’t [overcome] the emotional, reptilian brain.”

The result is that a person remains stuck in a hyperaroused state. “We know that the neurobiological basis for PTSD involves a prolonged, vigilant response to stress [involving] a multitude of brain circuits ... and of course the sympathetic nervous system and the pituitary and adrenal systems,” Dr. Nemeroff said.

Beyond brain changes, a genetic predisposition to PTSD accounts for a third of all cases, while an additional one-third are attributable to additional biological risk factors, according to Dr. Nemeroff (Nature 2011;470:492-7).

Just as with all anxiety-related disorders, women are more PTSD susceptible than are men. One of the “few things everybody agrees on,” Dr. Nemeroff said, is that early-life trauma such as neglect or abuse is a definite risk factor for PTSD, in part because early-life stress is thought to permanently program the brain regions involved in stress- and anxiety-mediation. Add to that, any adult level trauma, and they two “synergize. The more adult trauma coupled with early childhood abuse or neglect, the higher the level of PTSD.”

Meanwhile, poor social support, especially after the occurrence of a traumatic event, is a traditional prognosticator of poor recovery from PTSD, as are a family history of mood disorders, lower I.Q. and education, and experiencing other stressors the year before or after a traumatic event.

Dr. Nemeroff said that although the goals of treatment are reduced core symptoms, improved quality of life and function, strength, and resilience against subsequent stress, “the sad fact of the matter is that we don’t have a clue what the best treatment is, because we have no predictors of treatment response for PTSD.”

The most common treatments for PTSD are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), although the best data available suggest that prolonged imaginal exposure therapy is the most effective, Dr. Nemeroff said. It can be provided either virtually or in person, and includes breathing techniques, psychoeducation, and cognitive therapy. The Institute of Medicine gives exposure therapy its highest rating for scientific evidence, said Dr. Nemeroff, who is a board member of the institute.

Pharmacologic treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration for PTSD treatment include sertraline and paroxetine, although other antidepressants can be prescribed off-label to some effect.

With sertraline, there is a “pretty low bar” of efficacy, according to Dr. Nemeroff, since only a 30% improvement in symptoms was recorded in 60% of study participants for FDA approval. It’s important to remember the treatment-response in PTSD is much slower than in major depression, Dr. Nemeroff said. “It can take as much as 9 months, so don’t give up.”

Combining sertraline with prolonged exposure therapy is even more effective, he said (J. Trauma Stress 2006;19:625-38). Meanwhile, other data show what paroxetine alone performed better than placebo, but the data are mixed for the drug in combination with prolonged exposure therapy (Am. J. Psychiatry 2012;169:80-8), (J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008;69:400-5), (J. Clin. Neurosci. 2008;62:646-52), and (Am. J. Psychiatry 2001;158:1982-8).

Dr. Nemeroff said lately, he has been treating PTSD patients with venlafaxine 450 mg, which is much higher than the usual dose of about 220 mg, with “considerably good results” (Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2006;63:1158-65).

Improvements in memory and hippocampal volume generally are found with SSRI treatments, as well as reductions in symptom severity, according to Dr. Nemeroff.

For PTSD patients who are struggling with insomnia and other sleep-related problems, Dr. Nemeroff said prazosin has been “phenomenal,” especially in reducing nightmares (Am. J. Psychiatry 2013;170:1003-10).

One drug class to avoid using with PTSD patients is benzodiazepines, he said. “Every study has shown that benzodiazepines in PTSD do not work, and they come with a high rate of substance abuse in this population.”

*Dr. Nemeroff disclosed that he receives research and grant support from the National Institutes of Health. He also serves as a consultant for several companies, including Xhale, Takeda, SK Pharma, Shire, Roche, Lilly, Allergan, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Development America, Taisho Pharmaceutical, Lundbeck, Prismic Pharmaceuticals, and Clintara LLC. He is a stockholder in Xhale, Celgene, Seattle Genetics, Abbvie, Titan Pharmaceuticals, and OPKO Health.

In addition, he holds financial/proprietary interest in patents for method/devices for the transdermal delivery of lithium and for a method of assessing antidepressant drug therapy.

*Correction, 4/10/2015: An earlier version of this story misstated Dr. Nemeroff's disclosures.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE NPA PSYCHOPHARMOCOLOGY UPDATE

VIDEO – ‘Significant recovery’ possible in schizophrenia with cognitive interventions

COLORADO SPRINGS– Many clinicians are unaware that nonpharmacologic interventions can lead to positive results for patients with schizophrenia, according to Dr. Sophia Vinogradov and Dr. Joshua Woolley, psychiatrists from the University of California, San Francisco.

“The one message we have is that there is hope,” Dr. Woolley says in this interview, which was recorded at the biennial meeting of the 15th International Congress on Schizophrenia Research. Patients with schizophrenia can still “live a fulfilling life and have a significant recovery.”

Dr. Vinogradov and Dr. Woolley discuss how clinicians can use cognitive training techniques, cognitive-behavioral therapy, social media, and mobile technology to help ensure positive outcomes where patients see their disease not as a reason to withdraw from society but as an opportunity to engage with others who share similar struggles.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

COLORADO SPRINGS– Many clinicians are unaware that nonpharmacologic interventions can lead to positive results for patients with schizophrenia, according to Dr. Sophia Vinogradov and Dr. Joshua Woolley, psychiatrists from the University of California, San Francisco.

“The one message we have is that there is hope,” Dr. Woolley says in this interview, which was recorded at the biennial meeting of the 15th International Congress on Schizophrenia Research. Patients with schizophrenia can still “live a fulfilling life and have a significant recovery.”