User login

VIDEO: Reducing the duration of untreated psychosis in the community

TORONTO – Communities that emphasize early behavioral and mental health prevention and employ the resources to make early treatment and intervention possible see greatly improved mental health outcomes, according to Dr. Brian O’Donoghue, a speaker at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

“With early psychosis, when it is treated intensively and holistically, the outcomes can be much more positive for young people who are experiencing a first-episode psychosis,” Dr. O’Donoghue, a clinical research fellow with Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health near Melbourne, said in a video interview. Also discussed are how to create, develop, and run community health clinics for young people aged 15-24 years who are experiencing some form of psychosis.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

TORONTO – Communities that emphasize early behavioral and mental health prevention and employ the resources to make early treatment and intervention possible see greatly improved mental health outcomes, according to Dr. Brian O’Donoghue, a speaker at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

“With early psychosis, when it is treated intensively and holistically, the outcomes can be much more positive for young people who are experiencing a first-episode psychosis,” Dr. O’Donoghue, a clinical research fellow with Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health near Melbourne, said in a video interview. Also discussed are how to create, develop, and run community health clinics for young people aged 15-24 years who are experiencing some form of psychosis.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

TORONTO – Communities that emphasize early behavioral and mental health prevention and employ the resources to make early treatment and intervention possible see greatly improved mental health outcomes, according to Dr. Brian O’Donoghue, a speaker at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association.

“With early psychosis, when it is treated intensively and holistically, the outcomes can be much more positive for young people who are experiencing a first-episode psychosis,” Dr. O’Donoghue, a clinical research fellow with Orygen, The National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health near Melbourne, said in a video interview. Also discussed are how to create, develop, and run community health clinics for young people aged 15-24 years who are experiencing some form of psychosis.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT THE APA ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: Long-term strategies for patients and loved ones managing schizophrenia

TORONTO – Managing a diagnosis along the schizophrenia spectrum can be difficult not only for the patient, but also for the patient’s friends and loved ones. “It’s also hard on the clinician,” says Dr. Ira D. Glick, a professor emeritus of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University and a presenter at the annual American Psychiatric Association meeting. In this video, Dr. Glick outlines strategies for making life with schizophrenia less disruptive and even rewarding.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

TORONTO – Managing a diagnosis along the schizophrenia spectrum can be difficult not only for the patient, but also for the patient’s friends and loved ones. “It’s also hard on the clinician,” says Dr. Ira D. Glick, a professor emeritus of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University and a presenter at the annual American Psychiatric Association meeting. In this video, Dr. Glick outlines strategies for making life with schizophrenia less disruptive and even rewarding.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

TORONTO – Managing a diagnosis along the schizophrenia spectrum can be difficult not only for the patient, but also for the patient’s friends and loved ones. “It’s also hard on the clinician,” says Dr. Ira D. Glick, a professor emeritus of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Stanford (Calif.) University and a presenter at the annual American Psychiatric Association meeting. In this video, Dr. Glick outlines strategies for making life with schizophrenia less disruptive and even rewarding.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT THE APA ANNUAL MEETING

VIDEO: Getting first-episode psychosis treatment in the community setting ‘just right’

TORONTO – Because cardiometabolic syndrome is a primary concern in first-episode psychosis on the schizophrenia spectrum, one study explored whether prescriber education alone was enough to help ensure the correct antipsychotic medication was prescribed in the community setting.

“Prescribers are aware of the cardiometabolic effects of antipsychotics, but in the heat of the moment, it might not be in the forefront of their minds,” says study coauthor Dr. Mary F. Brunette, medical director of the Bureau of Behavioral Health at the Department of Health and Human Services in Concord, N.H., in this video interview. By measuring whether an educational intervention changed prescriber habits, Dr. Brunette, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, and her colleagues determined that there were some improvements, particularly in polypharmacy. The study also showed that although gender, age, and insurance status did influence a prescriber’s choice of antipsychotics, actual diagnosis had limited and inconsistent effects.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

TORONTO – Because cardiometabolic syndrome is a primary concern in first-episode psychosis on the schizophrenia spectrum, one study explored whether prescriber education alone was enough to help ensure the correct antipsychotic medication was prescribed in the community setting.

“Prescribers are aware of the cardiometabolic effects of antipsychotics, but in the heat of the moment, it might not be in the forefront of their minds,” says study coauthor Dr. Mary F. Brunette, medical director of the Bureau of Behavioral Health at the Department of Health and Human Services in Concord, N.H., in this video interview. By measuring whether an educational intervention changed prescriber habits, Dr. Brunette, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, and her colleagues determined that there were some improvements, particularly in polypharmacy. The study also showed that although gender, age, and insurance status did influence a prescriber’s choice of antipsychotics, actual diagnosis had limited and inconsistent effects.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

TORONTO – Because cardiometabolic syndrome is a primary concern in first-episode psychosis on the schizophrenia spectrum, one study explored whether prescriber education alone was enough to help ensure the correct antipsychotic medication was prescribed in the community setting.

“Prescribers are aware of the cardiometabolic effects of antipsychotics, but in the heat of the moment, it might not be in the forefront of their minds,” says study coauthor Dr. Mary F. Brunette, medical director of the Bureau of Behavioral Health at the Department of Health and Human Services in Concord, N.H., in this video interview. By measuring whether an educational intervention changed prescriber habits, Dr. Brunette, who presented the findings at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association, and her colleagues determined that there were some improvements, particularly in polypharmacy. The study also showed that although gender, age, and insurance status did influence a prescriber’s choice of antipsychotics, actual diagnosis had limited and inconsistent effects.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

AT THE APA ANNUAL MEETING

APA: RDoC helps psychiatry ‘use its words’

TORONTO – Five in the afternoon, after a full day of cramming one’s brain with information from multiple sessions at an annual medical meeting, is a cruel time to offer a panel discussion linking behavioral economics, Freud, and the RDoC to future treatments for mental disorders.

But, at this year’s annual American Psychiatric Association meeting, that hour found me seated in a discussion of these things and more. The Evolution of Mathematical Psychiatry: Implications for Bridging DSM-5 and Research Domain Criteria Using Behavioral Game Theory simultaneously knocked me out and brought me to my senses. Psychiatry sure is getting exciting.

After the slightly bumptious way the release of the RDoC was announced in 2013, just days before the APA’s annual meeting and the official release of the DSM-5, it’s noteworthy to see how quickly the RDoC, which is now the primary mechanism for evaluating funding at the National Institute of Mental Health, is being embraced by at least some in psychiatry.

Unlike the DSM-5, which relies on “consensus definitions” of disease, as NIMH Director Thomas Insel put it in his stinging rebuke of the APA’s signature publication, the RDoC’s emphasis is on the creation of diagnostic tools from matrices of genetics, imaging, cognitive science, and neurobiology, among other fields.

“The beauty of the RDoC is that it allows us to integrate smaller theories, such as those from Freud and math, into a larger one,” the session’s discussant, Dr. Andrew Gerber, director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute’s MRI research program, New York, told the audience.

Not everyone is happy about this change in grant making for a variety of reasons, which I would summarize in general as dismay over the amount of effort and resources it can take to not do things the way they’ve always been done. However, some researchers I have spoken with who acknowledge the spirit of the RDoC, are concerned the criteria are still too narrow, overemphasizing the brain as the master organ that controls the entire body, rather than seeing it as simply an equal player in a bidirectional highway of signaling that can originate in the gut or the immune system, for example. Indeed, such literature is growing, with Dr. Charles Raison as one of its more prominent thought leaders.

Regardless of the RDoC’s possible limitations, its effect on psychiatry could prove revolutionary. The use of “decision science” to assess anomalies in cognitive function, which is one of the domains included in the RDoC, is evidence of this.

Decision science is the exploration of the nonconscious and the conscious processes, including implicit memory, procedural memory, and even habits involved when a person makes a decision to engage in a specific behavior. There is great potential for patients to be empowered by this, since it allows them to see their condition in terms of choice rather than affliction.

Here’s what that could mean for treating people with obsessive-compulsive disorder, for example. Instead of patients not having control over their compulsions, patients are quite literally just playing a game, one that involves two players: the patient and the patient’s future self. The object of the game, according to presenter Dr. Lawrence Amsel, who directs dissemination research for trauma services at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, is for the player in the present (the patient) to avoid blame when a calamity such as the house burning down is discovered by the patient’s future self.

Since the patient living in the present cannot control whether his house actually burns down, but he can prove that he was clever enough to check 14 times that the gas was not left on, he can legitimately claim, “this horrible thing had nothing to do with me.”

This point of view employs behavioral game theory, which economists use to predict irrationalities in consumer behavior. According to Dr. Amsel, it also can be applied to understanding the physiology of the mind: “Often, when people deviate from rational behavior, there is a way to understand that.”

What is the irrationality that causes a person to repeatedly check that he has turned off the stove? What is the reason he cannot cognitively process his multiple verifications that he in fact turned the stove off? It is simply that the patient with OCD finds less value in the present moment and plenty in the future, specifically, “the future me that is in the petty, angry mode,” said Dr. Amsel.

Is this a fear of having a negative impact on one’s future, of being unable to control the outcome, and thus control what others (in this case, one’s future self) think? Such are the sorts of questions Freud or Jung might have asked 100 years ago.

In today’s mathematical terms, Dr. Amsel explained it as an equation where the expected change in risk, multiplied by the potential disaster, is greater than the cost of the behavior, or in this case, constantly checking the stove. Psychiatry can leverage this scientific equation to help patients dispense with magical thinking and to see they have control over their actions, but not the outcomes.

According to Dr. Gerber, however, Freudian psychoanalysis still is implicit in decision science, because rather than just identifying and treating symptoms, as Freud accused clinical psychiatry of doing, it helps uncover the meaning inherent in a person’s behavior and the behavior’s relevance to the patient’s direct experience, just as Freud implored his disciples to do.

“Symptoms are rational,” Dr. Gerber said.

Symptoms are the representation of what Dr. Gerber referred to as the “schema, a construct that serves as a psychological intermediary between lower-level physiologic or cognitive process, such as long-term memory or affective state, and response such as thoughts, feelings, and behavior, to a complex stimulus.”

In other words, what does obsessively checking the stove actually mean to the person?

By using math to untether psychiatry from methodical, clinical thinking and cast it slightly adrift into a nonlinear sea seems to me an epic moment in the history of the field. Rather than rely solely on a didactic DSM-5 rife with soulless jargon and acronyms such as OCD, PTSD, TBI, and ADHD, patients are reintroduced to themselves through the poetry of their own metaphors of being. This empowers them to use words and images to bridge their conscious mind to what Dr. Gerber and his copanelists referred to as the nonconscious mind (deftly differentiating it from Freud’s and Jung’s unconscious mind).

During the question and answer period, several in the audience expressed their concern that such leaping science will outpace policy and practice (I wager it will). The response from the panel was in a sense to “use your words” and to help patients contextualize their nonconscious decisions with metaphor, which the speakers pointed out can be done in practice now, without waiting for studies or policy changes, although Dr. Amsel and Dr. Gerber both noted that functional MRI studies of what happens neurobiologically in the minds of people with OCD intended to support this type of decision science are underway.

Meanwhile, a metaphor-inspired intervention in the case of the patient with OCD, according to Dr. Amsel, who specifically stressed the power of metaphors to make a situation more real to a patient, is to suggest becoming more aware (conscious) of the various constituencies “running” the patient’s cognitive processes: “Your life is being run by a committee, but you’re not invited. So we at least need to get you an invitation.”

After the session, I spoke with Dr. Gerber. We agreed there is a place for the DSM-5, what Dr. Insel referred to as, “a reliable dictionary” that helps clinicians all speak the same language. Yet, I am intrigued by how the RDoC seems to breathe life into that dictionary by inspiring these connections between the conscious and the nonconscious in cognition.

With the return of such beauty and wit to the language of the mind, I am also intrigued to consider how the RDoC might also inspire a true renaissance of the medical arts. I have often considered psychiatry not a field so much as a vast and deep sea with math and science along one shore and arts and literature on another. It is on the science shore where mental disorders are neatly contained by the nosology of the DSM-5, while on the arts and literature shore are the howls of human experience depicted in the words and pictures of those who’ve sought to give meaning to their individual experiences with the mental pain and anguish listed on the other shore.

I often have lamented the senseless distance between these shores. We need a bridge between the two, a place to stand and gaze at our reflections in the water, and a sturdy way to cross over. Could the RDoC be the bridge between having a way to define and treat, and having a way to talk ourselves out of the horror of a purely random existence?

“It’s a shame the way the RDoC has been perceived by some,” Dr. Gerber told me. “There’s a lot of good in it.”

Or, as Joyce wrote in Ulysses, “I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

TORONTO – Five in the afternoon, after a full day of cramming one’s brain with information from multiple sessions at an annual medical meeting, is a cruel time to offer a panel discussion linking behavioral economics, Freud, and the RDoC to future treatments for mental disorders.

But, at this year’s annual American Psychiatric Association meeting, that hour found me seated in a discussion of these things and more. The Evolution of Mathematical Psychiatry: Implications for Bridging DSM-5 and Research Domain Criteria Using Behavioral Game Theory simultaneously knocked me out and brought me to my senses. Psychiatry sure is getting exciting.

After the slightly bumptious way the release of the RDoC was announced in 2013, just days before the APA’s annual meeting and the official release of the DSM-5, it’s noteworthy to see how quickly the RDoC, which is now the primary mechanism for evaluating funding at the National Institute of Mental Health, is being embraced by at least some in psychiatry.

Unlike the DSM-5, which relies on “consensus definitions” of disease, as NIMH Director Thomas Insel put it in his stinging rebuke of the APA’s signature publication, the RDoC’s emphasis is on the creation of diagnostic tools from matrices of genetics, imaging, cognitive science, and neurobiology, among other fields.

“The beauty of the RDoC is that it allows us to integrate smaller theories, such as those from Freud and math, into a larger one,” the session’s discussant, Dr. Andrew Gerber, director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute’s MRI research program, New York, told the audience.

Not everyone is happy about this change in grant making for a variety of reasons, which I would summarize in general as dismay over the amount of effort and resources it can take to not do things the way they’ve always been done. However, some researchers I have spoken with who acknowledge the spirit of the RDoC, are concerned the criteria are still too narrow, overemphasizing the brain as the master organ that controls the entire body, rather than seeing it as simply an equal player in a bidirectional highway of signaling that can originate in the gut or the immune system, for example. Indeed, such literature is growing, with Dr. Charles Raison as one of its more prominent thought leaders.

Regardless of the RDoC’s possible limitations, its effect on psychiatry could prove revolutionary. The use of “decision science” to assess anomalies in cognitive function, which is one of the domains included in the RDoC, is evidence of this.

Decision science is the exploration of the nonconscious and the conscious processes, including implicit memory, procedural memory, and even habits involved when a person makes a decision to engage in a specific behavior. There is great potential for patients to be empowered by this, since it allows them to see their condition in terms of choice rather than affliction.

Here’s what that could mean for treating people with obsessive-compulsive disorder, for example. Instead of patients not having control over their compulsions, patients are quite literally just playing a game, one that involves two players: the patient and the patient’s future self. The object of the game, according to presenter Dr. Lawrence Amsel, who directs dissemination research for trauma services at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, is for the player in the present (the patient) to avoid blame when a calamity such as the house burning down is discovered by the patient’s future self.

Since the patient living in the present cannot control whether his house actually burns down, but he can prove that he was clever enough to check 14 times that the gas was not left on, he can legitimately claim, “this horrible thing had nothing to do with me.”

This point of view employs behavioral game theory, which economists use to predict irrationalities in consumer behavior. According to Dr. Amsel, it also can be applied to understanding the physiology of the mind: “Often, when people deviate from rational behavior, there is a way to understand that.”

What is the irrationality that causes a person to repeatedly check that he has turned off the stove? What is the reason he cannot cognitively process his multiple verifications that he in fact turned the stove off? It is simply that the patient with OCD finds less value in the present moment and plenty in the future, specifically, “the future me that is in the petty, angry mode,” said Dr. Amsel.

Is this a fear of having a negative impact on one’s future, of being unable to control the outcome, and thus control what others (in this case, one’s future self) think? Such are the sorts of questions Freud or Jung might have asked 100 years ago.

In today’s mathematical terms, Dr. Amsel explained it as an equation where the expected change in risk, multiplied by the potential disaster, is greater than the cost of the behavior, or in this case, constantly checking the stove. Psychiatry can leverage this scientific equation to help patients dispense with magical thinking and to see they have control over their actions, but not the outcomes.

According to Dr. Gerber, however, Freudian psychoanalysis still is implicit in decision science, because rather than just identifying and treating symptoms, as Freud accused clinical psychiatry of doing, it helps uncover the meaning inherent in a person’s behavior and the behavior’s relevance to the patient’s direct experience, just as Freud implored his disciples to do.

“Symptoms are rational,” Dr. Gerber said.

Symptoms are the representation of what Dr. Gerber referred to as the “schema, a construct that serves as a psychological intermediary between lower-level physiologic or cognitive process, such as long-term memory or affective state, and response such as thoughts, feelings, and behavior, to a complex stimulus.”

In other words, what does obsessively checking the stove actually mean to the person?

By using math to untether psychiatry from methodical, clinical thinking and cast it slightly adrift into a nonlinear sea seems to me an epic moment in the history of the field. Rather than rely solely on a didactic DSM-5 rife with soulless jargon and acronyms such as OCD, PTSD, TBI, and ADHD, patients are reintroduced to themselves through the poetry of their own metaphors of being. This empowers them to use words and images to bridge their conscious mind to what Dr. Gerber and his copanelists referred to as the nonconscious mind (deftly differentiating it from Freud’s and Jung’s unconscious mind).

During the question and answer period, several in the audience expressed their concern that such leaping science will outpace policy and practice (I wager it will). The response from the panel was in a sense to “use your words” and to help patients contextualize their nonconscious decisions with metaphor, which the speakers pointed out can be done in practice now, without waiting for studies or policy changes, although Dr. Amsel and Dr. Gerber both noted that functional MRI studies of what happens neurobiologically in the minds of people with OCD intended to support this type of decision science are underway.

Meanwhile, a metaphor-inspired intervention in the case of the patient with OCD, according to Dr. Amsel, who specifically stressed the power of metaphors to make a situation more real to a patient, is to suggest becoming more aware (conscious) of the various constituencies “running” the patient’s cognitive processes: “Your life is being run by a committee, but you’re not invited. So we at least need to get you an invitation.”

After the session, I spoke with Dr. Gerber. We agreed there is a place for the DSM-5, what Dr. Insel referred to as, “a reliable dictionary” that helps clinicians all speak the same language. Yet, I am intrigued by how the RDoC seems to breathe life into that dictionary by inspiring these connections between the conscious and the nonconscious in cognition.

With the return of such beauty and wit to the language of the mind, I am also intrigued to consider how the RDoC might also inspire a true renaissance of the medical arts. I have often considered psychiatry not a field so much as a vast and deep sea with math and science along one shore and arts and literature on another. It is on the science shore where mental disorders are neatly contained by the nosology of the DSM-5, while on the arts and literature shore are the howls of human experience depicted in the words and pictures of those who’ve sought to give meaning to their individual experiences with the mental pain and anguish listed on the other shore.

I often have lamented the senseless distance between these shores. We need a bridge between the two, a place to stand and gaze at our reflections in the water, and a sturdy way to cross over. Could the RDoC be the bridge between having a way to define and treat, and having a way to talk ourselves out of the horror of a purely random existence?

“It’s a shame the way the RDoC has been perceived by some,” Dr. Gerber told me. “There’s a lot of good in it.”

Or, as Joyce wrote in Ulysses, “I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

TORONTO – Five in the afternoon, after a full day of cramming one’s brain with information from multiple sessions at an annual medical meeting, is a cruel time to offer a panel discussion linking behavioral economics, Freud, and the RDoC to future treatments for mental disorders.

But, at this year’s annual American Psychiatric Association meeting, that hour found me seated in a discussion of these things and more. The Evolution of Mathematical Psychiatry: Implications for Bridging DSM-5 and Research Domain Criteria Using Behavioral Game Theory simultaneously knocked me out and brought me to my senses. Psychiatry sure is getting exciting.

After the slightly bumptious way the release of the RDoC was announced in 2013, just days before the APA’s annual meeting and the official release of the DSM-5, it’s noteworthy to see how quickly the RDoC, which is now the primary mechanism for evaluating funding at the National Institute of Mental Health, is being embraced by at least some in psychiatry.

Unlike the DSM-5, which relies on “consensus definitions” of disease, as NIMH Director Thomas Insel put it in his stinging rebuke of the APA’s signature publication, the RDoC’s emphasis is on the creation of diagnostic tools from matrices of genetics, imaging, cognitive science, and neurobiology, among other fields.

“The beauty of the RDoC is that it allows us to integrate smaller theories, such as those from Freud and math, into a larger one,” the session’s discussant, Dr. Andrew Gerber, director of the New York State Psychiatric Institute’s MRI research program, New York, told the audience.

Not everyone is happy about this change in grant making for a variety of reasons, which I would summarize in general as dismay over the amount of effort and resources it can take to not do things the way they’ve always been done. However, some researchers I have spoken with who acknowledge the spirit of the RDoC, are concerned the criteria are still too narrow, overemphasizing the brain as the master organ that controls the entire body, rather than seeing it as simply an equal player in a bidirectional highway of signaling that can originate in the gut or the immune system, for example. Indeed, such literature is growing, with Dr. Charles Raison as one of its more prominent thought leaders.

Regardless of the RDoC’s possible limitations, its effect on psychiatry could prove revolutionary. The use of “decision science” to assess anomalies in cognitive function, which is one of the domains included in the RDoC, is evidence of this.

Decision science is the exploration of the nonconscious and the conscious processes, including implicit memory, procedural memory, and even habits involved when a person makes a decision to engage in a specific behavior. There is great potential for patients to be empowered by this, since it allows them to see their condition in terms of choice rather than affliction.

Here’s what that could mean for treating people with obsessive-compulsive disorder, for example. Instead of patients not having control over their compulsions, patients are quite literally just playing a game, one that involves two players: the patient and the patient’s future self. The object of the game, according to presenter Dr. Lawrence Amsel, who directs dissemination research for trauma services at the New York State Psychiatric Institute, is for the player in the present (the patient) to avoid blame when a calamity such as the house burning down is discovered by the patient’s future self.

Since the patient living in the present cannot control whether his house actually burns down, but he can prove that he was clever enough to check 14 times that the gas was not left on, he can legitimately claim, “this horrible thing had nothing to do with me.”

This point of view employs behavioral game theory, which economists use to predict irrationalities in consumer behavior. According to Dr. Amsel, it also can be applied to understanding the physiology of the mind: “Often, when people deviate from rational behavior, there is a way to understand that.”

What is the irrationality that causes a person to repeatedly check that he has turned off the stove? What is the reason he cannot cognitively process his multiple verifications that he in fact turned the stove off? It is simply that the patient with OCD finds less value in the present moment and plenty in the future, specifically, “the future me that is in the petty, angry mode,” said Dr. Amsel.

Is this a fear of having a negative impact on one’s future, of being unable to control the outcome, and thus control what others (in this case, one’s future self) think? Such are the sorts of questions Freud or Jung might have asked 100 years ago.

In today’s mathematical terms, Dr. Amsel explained it as an equation where the expected change in risk, multiplied by the potential disaster, is greater than the cost of the behavior, or in this case, constantly checking the stove. Psychiatry can leverage this scientific equation to help patients dispense with magical thinking and to see they have control over their actions, but not the outcomes.

According to Dr. Gerber, however, Freudian psychoanalysis still is implicit in decision science, because rather than just identifying and treating symptoms, as Freud accused clinical psychiatry of doing, it helps uncover the meaning inherent in a person’s behavior and the behavior’s relevance to the patient’s direct experience, just as Freud implored his disciples to do.

“Symptoms are rational,” Dr. Gerber said.

Symptoms are the representation of what Dr. Gerber referred to as the “schema, a construct that serves as a psychological intermediary between lower-level physiologic or cognitive process, such as long-term memory or affective state, and response such as thoughts, feelings, and behavior, to a complex stimulus.”

In other words, what does obsessively checking the stove actually mean to the person?

By using math to untether psychiatry from methodical, clinical thinking and cast it slightly adrift into a nonlinear sea seems to me an epic moment in the history of the field. Rather than rely solely on a didactic DSM-5 rife with soulless jargon and acronyms such as OCD, PTSD, TBI, and ADHD, patients are reintroduced to themselves through the poetry of their own metaphors of being. This empowers them to use words and images to bridge their conscious mind to what Dr. Gerber and his copanelists referred to as the nonconscious mind (deftly differentiating it from Freud’s and Jung’s unconscious mind).

During the question and answer period, several in the audience expressed their concern that such leaping science will outpace policy and practice (I wager it will). The response from the panel was in a sense to “use your words” and to help patients contextualize their nonconscious decisions with metaphor, which the speakers pointed out can be done in practice now, without waiting for studies or policy changes, although Dr. Amsel and Dr. Gerber both noted that functional MRI studies of what happens neurobiologically in the minds of people with OCD intended to support this type of decision science are underway.

Meanwhile, a metaphor-inspired intervention in the case of the patient with OCD, according to Dr. Amsel, who specifically stressed the power of metaphors to make a situation more real to a patient, is to suggest becoming more aware (conscious) of the various constituencies “running” the patient’s cognitive processes: “Your life is being run by a committee, but you’re not invited. So we at least need to get you an invitation.”

After the session, I spoke with Dr. Gerber. We agreed there is a place for the DSM-5, what Dr. Insel referred to as, “a reliable dictionary” that helps clinicians all speak the same language. Yet, I am intrigued by how the RDoC seems to breathe life into that dictionary by inspiring these connections between the conscious and the nonconscious in cognition.

With the return of such beauty and wit to the language of the mind, I am also intrigued to consider how the RDoC might also inspire a true renaissance of the medical arts. I have often considered psychiatry not a field so much as a vast and deep sea with math and science along one shore and arts and literature on another. It is on the science shore where mental disorders are neatly contained by the nosology of the DSM-5, while on the arts and literature shore are the howls of human experience depicted in the words and pictures of those who’ve sought to give meaning to their individual experiences with the mental pain and anguish listed on the other shore.

I often have lamented the senseless distance between these shores. We need a bridge between the two, a place to stand and gaze at our reflections in the water, and a sturdy way to cross over. Could the RDoC be the bridge between having a way to define and treat, and having a way to talk ourselves out of the horror of a purely random existence?

“It’s a shame the way the RDoC has been perceived by some,” Dr. Gerber told me. “There’s a lot of good in it.”

Or, as Joyce wrote in Ulysses, “I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.”

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

APA: DSM-5 leaves one-third of soldiers with subthreshold PTSD in limbo, expert says

TORONTO – The most effective ways to diagnose and treat posttraumatic stress disorder in military populations is at issue after the results of a recent study showed that a third of soldiers who previously would have qualified for the diagnosis do not under updated criteria. The matter is far from settled, however, and continues to be a matter of debate.

Data from a randomized, controlled study published last year (Lancet Psychiatry 2014;1:269-77)* and presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association indicate that about a third of soldiers who would have received a clinical diagnosis of PTSD under the DSM-IV criteria do not meet the standard under the DSM-5, released in 2013.

The DSM-5 definition added criteria denoting a person’s efforts to avoid any person, place, or thing that causes them to remember details or feelings experienced during a specific traumatic event. According to former Army psychiatrist Col. (Ret.) Charles W. Hoge, this kind of emotional suppression is exactly what military, law enforcement, and first responder personnel are trained to do in order to accomplish their duties. Indeed, his study indicated that most of the soldiers who did not meet the clinical threshold for PTSD failed criterion C, the section that addresses avoidance.

“The reason to change a definition is to improve clinical utility or improve specificity, but what we’ve done is just shifted the deck chairs,” said Dr. Hoge during his presentation at the meeting.

Not so, said Dr. Matthew J. Friedman, who served on the DSM-5 Work Group that addressed PTSD, and recently retired as executive director of the Veterans Affairs’ National Center for PTSD. In an interview, Dr. Friedman disagreed with framing the findings in terms of clinical utility, particularly if the diagnostic criteria are seen as “easily and reliably utilized by different clinicians.” In that case, Dr. Friedman said in the DSM-5 field trials conducted prior to the manual’s release, the proposed PTSD criteria proved to be among the “best.”

Rather than view the findings merely as a shuffling of seats, Dr. Friedman suggested the findings could lead to a deeper line of inquiry around whether there is in fact a response bias in military personnel who might be less likely to “endorse avoidance symptoms. If the study had been done by a structured interview with a trained clinician instead of by self-report, would the results have looked the same?”

In addition to increasing the number of criteria for PTSD from 17 to 20 symptoms, including the avoidant criteria, the DSM-5 reworded 8 symptoms, and further specified symptom clusters from three groups to four, with the addition of alterations in cognitions and mood to the third cluster, and alterations in arousal and reactivity becoming the fourth. The DSM-5 also reclassified the disorder from one of anxiety to one of trauma and stress.

Dr. Hoge, currently a researcher at the Center for Psychiatry and Neuroscience at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md., and his colleagues conducted a head-to-head comparison of the number of PTSD diagnoses obtained according to criteria in either the DSM-IV or the DSM-5. They surveyed 1,822 infantry soldiers for a single brigade combat team, more than half of whom had been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. Each survey included items from both the DSM-IV’s PTSD Check List, specific for “stressful experiences,” as well as the PCL-5 from the DSM-5. The questions from each were separated in the same survey by several other health-related items. Two versions of the survey were created and distributed randomly across the cohort; one version of the study listed the DSM-IV PCL-S questions first, the other survey had the PCL-5 version first.

The demographic and health outcomes in each group were essentially identical: Respondents were almost entirely male, aged 18-25 years, and roughly half of each group was married. Nearly one-fifth of each group was found by the survey to have moderate to severe general anxiety disorder.

The prevalence rates of PTSD in both survey groups were nearly identical: 12.9% vs. 12.2%, respectively; however, 30% of those surveyed who previously would have met the criteria for PTSD in the DSM-IV did not meet the DSM-5 criteria. Meanwhile, 28% of those who met DSM-5 criteria would not have met the DSM-IV criteria.

Dr. Friedman said the method used in Dr. Hoge’s study did not specifically explore the effect of the A criteria that identify the level of actual exposure to a traumatic event and a person’s immediate reaction to it. The DSM-IV stipulated in criterion A2 that a person experience “fear, helplessness, or horror” directly after a traumatic event. “One of the things that we found is that many soldiers who have all of the PTSD symptoms were ineligible for a PTSD diagnosis because they did not meet the A2 criterion.”

Dr. Friedman did not say whether this necessarily was the result of one’s crisis response training but noted that based on an evidence review, his work group dropped the criterion, and that now many people previously considered subclinical receive a PTSD diagnosis. “Had the A criteria been included in [Dr. Hoge’s] exploration, then a soldier who would not have met the A criteria in DSM-VI would make it in DSM-5, so it becomes a different ball game,” said Dr. Friedman, senior adviser at the National Center for PTSD, and professor of psychiatry and of pharmacology and toxicology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H.

In the study, Dr. Hoge and his coauthors wrote, “there is good evidence lending support to removal of the criterion A2,” yet during his presentation, he emphasized that just as service members learn to override fear, hopelessness, or horror, “they also learn to override avoidance symptoms as part of their training.” He concluded that because the prevalence rates are virtually the same between the fourth and fifth editions of the DSM, but for different reasons, there is no clinical utility in the new criteria. “Technically, [these soldiers] don’t meet the new definition, but clearly, they are individuals who need trauma-focused therapy and would have met the previous definition.”

Former Army psychiatrist Col. (Ret.) Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, meanwhile, said in an interview that Dr. Hoge and Dr. Friedman are “both world-renowned researchers in the field of PTSD and other related injuries of war.”

“All of us are struggling with the right way to diagnose PTSD, especially after almost 14 years of war and hundreds of thousands of wounded service members,” Dr. Ritchie said. “In addition, PTSD is not a simple, uniform diagnosis. It probably is many overlapping diagnoses.”

She has warned clinicians to proceed with caution, since how military personnel are diagnosed can have serious implications for their careers and benefits.

Currently, the VA and the Department of Defense support the status quo for any personnel previously diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria, but how subclinical cases should be handled is still at issue. The DSM-5 recommendation for subthreshold symptoms is to consider them an adjustment disorder.

Dr. Hoge rejected this as unhelpful, noting that a failure to adjust or adapt in the military setting has a “pejorative connotation.”

Dr. Friedman and the National Center for PTSD currently recommend using 308.89 from the DSM-5, which is “other specified trauma and stressor-related disorder.” Using “chronic adjustment disorder” is not appropriate, said Dr. Friedman, “because it has a 6-month time limit.” Dr. Friedman also noted that 308.89 in the DSM-5 is the same as the DSM-IV anxiety not otherwise specified, which prior to the DSM-5 was what was used for subthreshold PTSD. According to Dr. Hoge, however, 308.89 is linked in military electronic health records to “adjustment reaction with aggression antisocial behavior/destructiveness” and “aggressor identified syndrome,” both of which could have similar deleterious effects to a soldier as an “adjustment disorder.”

The current U.S. Army Medical Command policy allows physicians to continue diagnosing PTSD according to DSM-IV standards or to apply an unspecified anxiety code (ICD-9 300.00) for any subthreshold PTSD patients.

The fractious approach to diagnosis, according to Dr. Hoge, might be simplified by implementation later this year of the ICD-10, although he said early indications of the ICD-11 in Europe do not show better specificity when compared with the DSM-IV. He noted that the ICD-11 is simpler and has fewer symptom criteria. Here in the United States, he said, “We are not going in the right direction.”

Dr. Hoge said his presentation was based on his own findings and does not represent the opinions or policies of the U.S. Army.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

*Correction, 6/2/2014: An earlier version of this article misattributed a reference to Lancet Psychiatry.

TORONTO – The most effective ways to diagnose and treat posttraumatic stress disorder in military populations is at issue after the results of a recent study showed that a third of soldiers who previously would have qualified for the diagnosis do not under updated criteria. The matter is far from settled, however, and continues to be a matter of debate.

Data from a randomized, controlled study published last year (Lancet Psychiatry 2014;1:269-77)* and presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association indicate that about a third of soldiers who would have received a clinical diagnosis of PTSD under the DSM-IV criteria do not meet the standard under the DSM-5, released in 2013.

The DSM-5 definition added criteria denoting a person’s efforts to avoid any person, place, or thing that causes them to remember details or feelings experienced during a specific traumatic event. According to former Army psychiatrist Col. (Ret.) Charles W. Hoge, this kind of emotional suppression is exactly what military, law enforcement, and first responder personnel are trained to do in order to accomplish their duties. Indeed, his study indicated that most of the soldiers who did not meet the clinical threshold for PTSD failed criterion C, the section that addresses avoidance.

“The reason to change a definition is to improve clinical utility or improve specificity, but what we’ve done is just shifted the deck chairs,” said Dr. Hoge during his presentation at the meeting.

Not so, said Dr. Matthew J. Friedman, who served on the DSM-5 Work Group that addressed PTSD, and recently retired as executive director of the Veterans Affairs’ National Center for PTSD. In an interview, Dr. Friedman disagreed with framing the findings in terms of clinical utility, particularly if the diagnostic criteria are seen as “easily and reliably utilized by different clinicians.” In that case, Dr. Friedman said in the DSM-5 field trials conducted prior to the manual’s release, the proposed PTSD criteria proved to be among the “best.”

Rather than view the findings merely as a shuffling of seats, Dr. Friedman suggested the findings could lead to a deeper line of inquiry around whether there is in fact a response bias in military personnel who might be less likely to “endorse avoidance symptoms. If the study had been done by a structured interview with a trained clinician instead of by self-report, would the results have looked the same?”

In addition to increasing the number of criteria for PTSD from 17 to 20 symptoms, including the avoidant criteria, the DSM-5 reworded 8 symptoms, and further specified symptom clusters from three groups to four, with the addition of alterations in cognitions and mood to the third cluster, and alterations in arousal and reactivity becoming the fourth. The DSM-5 also reclassified the disorder from one of anxiety to one of trauma and stress.

Dr. Hoge, currently a researcher at the Center for Psychiatry and Neuroscience at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md., and his colleagues conducted a head-to-head comparison of the number of PTSD diagnoses obtained according to criteria in either the DSM-IV or the DSM-5. They surveyed 1,822 infantry soldiers for a single brigade combat team, more than half of whom had been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. Each survey included items from both the DSM-IV’s PTSD Check List, specific for “stressful experiences,” as well as the PCL-5 from the DSM-5. The questions from each were separated in the same survey by several other health-related items. Two versions of the survey were created and distributed randomly across the cohort; one version of the study listed the DSM-IV PCL-S questions first, the other survey had the PCL-5 version first.

The demographic and health outcomes in each group were essentially identical: Respondents were almost entirely male, aged 18-25 years, and roughly half of each group was married. Nearly one-fifth of each group was found by the survey to have moderate to severe general anxiety disorder.

The prevalence rates of PTSD in both survey groups were nearly identical: 12.9% vs. 12.2%, respectively; however, 30% of those surveyed who previously would have met the criteria for PTSD in the DSM-IV did not meet the DSM-5 criteria. Meanwhile, 28% of those who met DSM-5 criteria would not have met the DSM-IV criteria.

Dr. Friedman said the method used in Dr. Hoge’s study did not specifically explore the effect of the A criteria that identify the level of actual exposure to a traumatic event and a person’s immediate reaction to it. The DSM-IV stipulated in criterion A2 that a person experience “fear, helplessness, or horror” directly after a traumatic event. “One of the things that we found is that many soldiers who have all of the PTSD symptoms were ineligible for a PTSD diagnosis because they did not meet the A2 criterion.”

Dr. Friedman did not say whether this necessarily was the result of one’s crisis response training but noted that based on an evidence review, his work group dropped the criterion, and that now many people previously considered subclinical receive a PTSD diagnosis. “Had the A criteria been included in [Dr. Hoge’s] exploration, then a soldier who would not have met the A criteria in DSM-VI would make it in DSM-5, so it becomes a different ball game,” said Dr. Friedman, senior adviser at the National Center for PTSD, and professor of psychiatry and of pharmacology and toxicology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H.

In the study, Dr. Hoge and his coauthors wrote, “there is good evidence lending support to removal of the criterion A2,” yet during his presentation, he emphasized that just as service members learn to override fear, hopelessness, or horror, “they also learn to override avoidance symptoms as part of their training.” He concluded that because the prevalence rates are virtually the same between the fourth and fifth editions of the DSM, but for different reasons, there is no clinical utility in the new criteria. “Technically, [these soldiers] don’t meet the new definition, but clearly, they are individuals who need trauma-focused therapy and would have met the previous definition.”

Former Army psychiatrist Col. (Ret.) Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, meanwhile, said in an interview that Dr. Hoge and Dr. Friedman are “both world-renowned researchers in the field of PTSD and other related injuries of war.”

“All of us are struggling with the right way to diagnose PTSD, especially after almost 14 years of war and hundreds of thousands of wounded service members,” Dr. Ritchie said. “In addition, PTSD is not a simple, uniform diagnosis. It probably is many overlapping diagnoses.”

She has warned clinicians to proceed with caution, since how military personnel are diagnosed can have serious implications for their careers and benefits.

Currently, the VA and the Department of Defense support the status quo for any personnel previously diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria, but how subclinical cases should be handled is still at issue. The DSM-5 recommendation for subthreshold symptoms is to consider them an adjustment disorder.

Dr. Hoge rejected this as unhelpful, noting that a failure to adjust or adapt in the military setting has a “pejorative connotation.”

Dr. Friedman and the National Center for PTSD currently recommend using 308.89 from the DSM-5, which is “other specified trauma and stressor-related disorder.” Using “chronic adjustment disorder” is not appropriate, said Dr. Friedman, “because it has a 6-month time limit.” Dr. Friedman also noted that 308.89 in the DSM-5 is the same as the DSM-IV anxiety not otherwise specified, which prior to the DSM-5 was what was used for subthreshold PTSD. According to Dr. Hoge, however, 308.89 is linked in military electronic health records to “adjustment reaction with aggression antisocial behavior/destructiveness” and “aggressor identified syndrome,” both of which could have similar deleterious effects to a soldier as an “adjustment disorder.”

The current U.S. Army Medical Command policy allows physicians to continue diagnosing PTSD according to DSM-IV standards or to apply an unspecified anxiety code (ICD-9 300.00) for any subthreshold PTSD patients.

The fractious approach to diagnosis, according to Dr. Hoge, might be simplified by implementation later this year of the ICD-10, although he said early indications of the ICD-11 in Europe do not show better specificity when compared with the DSM-IV. He noted that the ICD-11 is simpler and has fewer symptom criteria. Here in the United States, he said, “We are not going in the right direction.”

Dr. Hoge said his presentation was based on his own findings and does not represent the opinions or policies of the U.S. Army.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

*Correction, 6/2/2014: An earlier version of this article misattributed a reference to Lancet Psychiatry.

TORONTO – The most effective ways to diagnose and treat posttraumatic stress disorder in military populations is at issue after the results of a recent study showed that a third of soldiers who previously would have qualified for the diagnosis do not under updated criteria. The matter is far from settled, however, and continues to be a matter of debate.

Data from a randomized, controlled study published last year (Lancet Psychiatry 2014;1:269-77)* and presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association indicate that about a third of soldiers who would have received a clinical diagnosis of PTSD under the DSM-IV criteria do not meet the standard under the DSM-5, released in 2013.

The DSM-5 definition added criteria denoting a person’s efforts to avoid any person, place, or thing that causes them to remember details or feelings experienced during a specific traumatic event. According to former Army psychiatrist Col. (Ret.) Charles W. Hoge, this kind of emotional suppression is exactly what military, law enforcement, and first responder personnel are trained to do in order to accomplish their duties. Indeed, his study indicated that most of the soldiers who did not meet the clinical threshold for PTSD failed criterion C, the section that addresses avoidance.

“The reason to change a definition is to improve clinical utility or improve specificity, but what we’ve done is just shifted the deck chairs,” said Dr. Hoge during his presentation at the meeting.

Not so, said Dr. Matthew J. Friedman, who served on the DSM-5 Work Group that addressed PTSD, and recently retired as executive director of the Veterans Affairs’ National Center for PTSD. In an interview, Dr. Friedman disagreed with framing the findings in terms of clinical utility, particularly if the diagnostic criteria are seen as “easily and reliably utilized by different clinicians.” In that case, Dr. Friedman said in the DSM-5 field trials conducted prior to the manual’s release, the proposed PTSD criteria proved to be among the “best.”

Rather than view the findings merely as a shuffling of seats, Dr. Friedman suggested the findings could lead to a deeper line of inquiry around whether there is in fact a response bias in military personnel who might be less likely to “endorse avoidance symptoms. If the study had been done by a structured interview with a trained clinician instead of by self-report, would the results have looked the same?”

In addition to increasing the number of criteria for PTSD from 17 to 20 symptoms, including the avoidant criteria, the DSM-5 reworded 8 symptoms, and further specified symptom clusters from three groups to four, with the addition of alterations in cognitions and mood to the third cluster, and alterations in arousal and reactivity becoming the fourth. The DSM-5 also reclassified the disorder from one of anxiety to one of trauma and stress.

Dr. Hoge, currently a researcher at the Center for Psychiatry and Neuroscience at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research in Silver Spring, Md., and his colleagues conducted a head-to-head comparison of the number of PTSD diagnoses obtained according to criteria in either the DSM-IV or the DSM-5. They surveyed 1,822 infantry soldiers for a single brigade combat team, more than half of whom had been deployed to Iraq or Afghanistan. Each survey included items from both the DSM-IV’s PTSD Check List, specific for “stressful experiences,” as well as the PCL-5 from the DSM-5. The questions from each were separated in the same survey by several other health-related items. Two versions of the survey were created and distributed randomly across the cohort; one version of the study listed the DSM-IV PCL-S questions first, the other survey had the PCL-5 version first.

The demographic and health outcomes in each group were essentially identical: Respondents were almost entirely male, aged 18-25 years, and roughly half of each group was married. Nearly one-fifth of each group was found by the survey to have moderate to severe general anxiety disorder.

The prevalence rates of PTSD in both survey groups were nearly identical: 12.9% vs. 12.2%, respectively; however, 30% of those surveyed who previously would have met the criteria for PTSD in the DSM-IV did not meet the DSM-5 criteria. Meanwhile, 28% of those who met DSM-5 criteria would not have met the DSM-IV criteria.

Dr. Friedman said the method used in Dr. Hoge’s study did not specifically explore the effect of the A criteria that identify the level of actual exposure to a traumatic event and a person’s immediate reaction to it. The DSM-IV stipulated in criterion A2 that a person experience “fear, helplessness, or horror” directly after a traumatic event. “One of the things that we found is that many soldiers who have all of the PTSD symptoms were ineligible for a PTSD diagnosis because they did not meet the A2 criterion.”

Dr. Friedman did not say whether this necessarily was the result of one’s crisis response training but noted that based on an evidence review, his work group dropped the criterion, and that now many people previously considered subclinical receive a PTSD diagnosis. “Had the A criteria been included in [Dr. Hoge’s] exploration, then a soldier who would not have met the A criteria in DSM-VI would make it in DSM-5, so it becomes a different ball game,” said Dr. Friedman, senior adviser at the National Center for PTSD, and professor of psychiatry and of pharmacology and toxicology at the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H.

In the study, Dr. Hoge and his coauthors wrote, “there is good evidence lending support to removal of the criterion A2,” yet during his presentation, he emphasized that just as service members learn to override fear, hopelessness, or horror, “they also learn to override avoidance symptoms as part of their training.” He concluded that because the prevalence rates are virtually the same between the fourth and fifth editions of the DSM, but for different reasons, there is no clinical utility in the new criteria. “Technically, [these soldiers] don’t meet the new definition, but clearly, they are individuals who need trauma-focused therapy and would have met the previous definition.”

Former Army psychiatrist Col. (Ret.) Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, meanwhile, said in an interview that Dr. Hoge and Dr. Friedman are “both world-renowned researchers in the field of PTSD and other related injuries of war.”

“All of us are struggling with the right way to diagnose PTSD, especially after almost 14 years of war and hundreds of thousands of wounded service members,” Dr. Ritchie said. “In addition, PTSD is not a simple, uniform diagnosis. It probably is many overlapping diagnoses.”

She has warned clinicians to proceed with caution, since how military personnel are diagnosed can have serious implications for their careers and benefits.

Currently, the VA and the Department of Defense support the status quo for any personnel previously diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria, but how subclinical cases should be handled is still at issue. The DSM-5 recommendation for subthreshold symptoms is to consider them an adjustment disorder.

Dr. Hoge rejected this as unhelpful, noting that a failure to adjust or adapt in the military setting has a “pejorative connotation.”

Dr. Friedman and the National Center for PTSD currently recommend using 308.89 from the DSM-5, which is “other specified trauma and stressor-related disorder.” Using “chronic adjustment disorder” is not appropriate, said Dr. Friedman, “because it has a 6-month time limit.” Dr. Friedman also noted that 308.89 in the DSM-5 is the same as the DSM-IV anxiety not otherwise specified, which prior to the DSM-5 was what was used for subthreshold PTSD. According to Dr. Hoge, however, 308.89 is linked in military electronic health records to “adjustment reaction with aggression antisocial behavior/destructiveness” and “aggressor identified syndrome,” both of which could have similar deleterious effects to a soldier as an “adjustment disorder.”

The current U.S. Army Medical Command policy allows physicians to continue diagnosing PTSD according to DSM-IV standards or to apply an unspecified anxiety code (ICD-9 300.00) for any subthreshold PTSD patients.

The fractious approach to diagnosis, according to Dr. Hoge, might be simplified by implementation later this year of the ICD-10, although he said early indications of the ICD-11 in Europe do not show better specificity when compared with the DSM-IV. He noted that the ICD-11 is simpler and has fewer symptom criteria. Here in the United States, he said, “We are not going in the right direction.”

Dr. Hoge said his presentation was based on his own findings and does not represent the opinions or policies of the U.S. Army.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

*Correction, 6/2/2014: An earlier version of this article misattributed a reference to Lancet Psychiatry.

AT THE APA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: The DSM-5 definition of posttraumatic stress disorder disqualifies a third of soldiers who once qualified for the diagnosis.

Major finding: Thirty percent of soldiers who previously would have met the criteria for PTSD in the DSM-IV did not meet the DSM-5 criteria.

Data source: Randomized, controlled study of 1,822 infantry soldiers for a single brigade combat team, half of whom had been deployed in war zones.

Disclosures: Dr. Hoge said his presentation was based on his own findings and does not represent the opinions or policies of the U.S. Army.

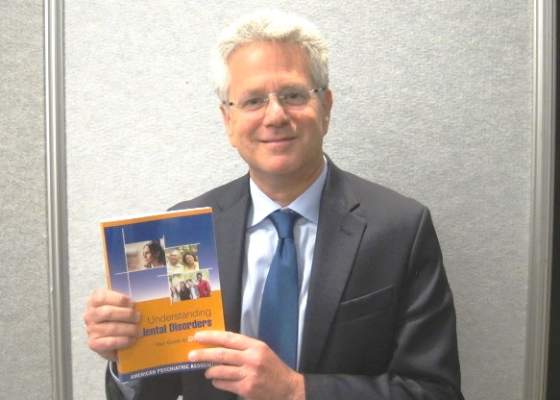

APA: Lay person’s guide to DSM-5 is good resource for primary care physicians

TORONTO – The American Psychiatric Association’s consumer guide to the DSM-5, “Understanding Mental Disorders,” debuted at the organization’s annual meeting this year.

Compared with the pricey clinical version of the manual, you get a lot for your $24.95 ($22.21 with an Amazon Prime account). At 370 pages, the guide is an easily digestible compendium; the diagnoses are grouped as they are in the primary manual, although without specifiers or subsets. Instead, there are bulleted lists of risk factors and symptoms. Treatment options are also bulleted, as are tips for remaining compliant with treatment regimens.

There are case histories written in lay person language and even blurbs that offer encouragement to those who might be, however slightly, alarmed to learn about various illnesses described. For example, in the chapter about “disorders that start in childhood” (neurodevelopmental disorders), the reader is advised that “treatment can lead to learning new ways to manage symptoms … and it can also offer hope.”

Although it’s the first book written and published by the APA specifically for the general public, when I asked the guide’s editorial adviser, Dr. Jeffrey Borenstein, if primary care doctors, who are very often the ones on the front lines of diagnosing and treating mental illness, would also benefit from having a copy at hand, he said yes. But primary care physicians apparently were not foremost in the minds of the editorial board that compiled this guide and planned its utility.

According to Dr. Borenstein, the guide is intended for the general public. In an interview, however, he singled out in particular, teachers, clergy, and others whose job it is to serve the community at large.

Now that the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act means our health care system is moving inexorably toward value-based care and that physicians risk losing money if their overall patient panel outcomes – including mental health – are poor, understanding how to diagnose and appropriately treat mental and behavioral health issues is of growing concern, particularly in primary care.

Earlier this year, I spoke with Chet Burrell, CEO of CareFirst, the Patient-Centered Medical Home division of BlueCross BlueShield. He told me that since 1 in 10 hospital admissions out of the 10,000 admissions CareFirst covers annually are behavioral health and substance abuse related, not only does that mean primary care practices are coordinating complex, postdischarge psychiatric care on as much as 10% of their patient panels, it also means that these patients have been left untreated or undertreated long enough for their illnesses to lead to an acute crisis, which is costly in one way or another to the patient, the payer, and the physician practice. “To get admitted [to the hospital] for a behavioral health or substance abuse issue, you have to be pretty sick,” Mr. Burrell said.

By connecting primary care physicians with psychiatrists in the community, however, as well as adding other structural support such as social workers or nurse practitioners, Mr. Burrell said primary care physicians in his network were beginning to see better outcomes and less financial risk.

It’s not that the APA is unaware of the growing need in the primary care realm for psychiatric expertise: At its annual meeting, the APA held a session entitled, “Educating Psychiatrists for Work in Integrated Care: Focus on Interdisciplinary Collaboration.” (I attended and tweeted pearls from each speaker @whitneymcknight if you’d like to see highlights). While attending the session, I detected two salient themes across the four presentations and concluding panel discussion. The first was that for all the increased mental and behavioral health training various medical school programs have added in the last decade, newly graduated primary care physicians are still underprepared for the amount of mental health concerns with which they will be faced in practice. The second was that psychiatrists and primary care physicians don’t know how to talk to one another effectively; one reason is that primary care physicians often feel that psychiatrists patronize them.

Psychiatrists can’t necessarily do much about the former, at least not in short order, but they can certainly do something about the latter, particularly in light of the APA’s new, forward-thinking branding campaign: “medical leadership for mind, brain, and body.”

Even if psychiatrists, whom many in other specialties “forget” are actually medical doctors, now want to claim their place at the health care table in an era when the bidirectional nature of mental and physical health is increasingly substantiated in myriad studies and is emphasized in ever more health policy–related decisions, the fact is that, at least where nonserious mental illness is concerned, the gatekeepers of access to mental health in this country are not psychiatrists but primary care doctors. As we move toward a value-based accountable care system where mental health outcomes can mean the difference between a physician receiving an upgrade or a downgrade, the demand for psychiatrists and other mental health professionals who can help ensure good, efficient patient outcomes will only expand.

Which returns us to the lay person’s guide to the DSM-5: It’s well organized. It’s easy to understand. And while it is in hard copy only, it’s handy for primary care physicians who often use the same search criteria as their patients might when turning to Dr. Google to find a quick answer to something with which they are not that familiar. It’s a pretty good bridge between primary care and psychiatry.

Dr. Borenstein had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the editor-in-chief of the APA’s Psychiatric News.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

TORONTO – The American Psychiatric Association’s consumer guide to the DSM-5, “Understanding Mental Disorders,” debuted at the organization’s annual meeting this year.

Compared with the pricey clinical version of the manual, you get a lot for your $24.95 ($22.21 with an Amazon Prime account). At 370 pages, the guide is an easily digestible compendium; the diagnoses are grouped as they are in the primary manual, although without specifiers or subsets. Instead, there are bulleted lists of risk factors and symptoms. Treatment options are also bulleted, as are tips for remaining compliant with treatment regimens.

There are case histories written in lay person language and even blurbs that offer encouragement to those who might be, however slightly, alarmed to learn about various illnesses described. For example, in the chapter about “disorders that start in childhood” (neurodevelopmental disorders), the reader is advised that “treatment can lead to learning new ways to manage symptoms … and it can also offer hope.”

Although it’s the first book written and published by the APA specifically for the general public, when I asked the guide’s editorial adviser, Dr. Jeffrey Borenstein, if primary care doctors, who are very often the ones on the front lines of diagnosing and treating mental illness, would also benefit from having a copy at hand, he said yes. But primary care physicians apparently were not foremost in the minds of the editorial board that compiled this guide and planned its utility.

According to Dr. Borenstein, the guide is intended for the general public. In an interview, however, he singled out in particular, teachers, clergy, and others whose job it is to serve the community at large.

Now that the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act means our health care system is moving inexorably toward value-based care and that physicians risk losing money if their overall patient panel outcomes – including mental health – are poor, understanding how to diagnose and appropriately treat mental and behavioral health issues is of growing concern, particularly in primary care.

Earlier this year, I spoke with Chet Burrell, CEO of CareFirst, the Patient-Centered Medical Home division of BlueCross BlueShield. He told me that since 1 in 10 hospital admissions out of the 10,000 admissions CareFirst covers annually are behavioral health and substance abuse related, not only does that mean primary care practices are coordinating complex, postdischarge psychiatric care on as much as 10% of their patient panels, it also means that these patients have been left untreated or undertreated long enough for their illnesses to lead to an acute crisis, which is costly in one way or another to the patient, the payer, and the physician practice. “To get admitted [to the hospital] for a behavioral health or substance abuse issue, you have to be pretty sick,” Mr. Burrell said.

By connecting primary care physicians with psychiatrists in the community, however, as well as adding other structural support such as social workers or nurse practitioners, Mr. Burrell said primary care physicians in his network were beginning to see better outcomes and less financial risk.

It’s not that the APA is unaware of the growing need in the primary care realm for psychiatric expertise: At its annual meeting, the APA held a session entitled, “Educating Psychiatrists for Work in Integrated Care: Focus on Interdisciplinary Collaboration.” (I attended and tweeted pearls from each speaker @whitneymcknight if you’d like to see highlights). While attending the session, I detected two salient themes across the four presentations and concluding panel discussion. The first was that for all the increased mental and behavioral health training various medical school programs have added in the last decade, newly graduated primary care physicians are still underprepared for the amount of mental health concerns with which they will be faced in practice. The second was that psychiatrists and primary care physicians don’t know how to talk to one another effectively; one reason is that primary care physicians often feel that psychiatrists patronize them.

Psychiatrists can’t necessarily do much about the former, at least not in short order, but they can certainly do something about the latter, particularly in light of the APA’s new, forward-thinking branding campaign: “medical leadership for mind, brain, and body.”

Even if psychiatrists, whom many in other specialties “forget” are actually medical doctors, now want to claim their place at the health care table in an era when the bidirectional nature of mental and physical health is increasingly substantiated in myriad studies and is emphasized in ever more health policy–related decisions, the fact is that, at least where nonserious mental illness is concerned, the gatekeepers of access to mental health in this country are not psychiatrists but primary care doctors. As we move toward a value-based accountable care system where mental health outcomes can mean the difference between a physician receiving an upgrade or a downgrade, the demand for psychiatrists and other mental health professionals who can help ensure good, efficient patient outcomes will only expand.

Which returns us to the lay person’s guide to the DSM-5: It’s well organized. It’s easy to understand. And while it is in hard copy only, it’s handy for primary care physicians who often use the same search criteria as their patients might when turning to Dr. Google to find a quick answer to something with which they are not that familiar. It’s a pretty good bridge between primary care and psychiatry.

Dr. Borenstein had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the editor-in-chief of the APA’s Psychiatric News.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

TORONTO – The American Psychiatric Association’s consumer guide to the DSM-5, “Understanding Mental Disorders,” debuted at the organization’s annual meeting this year.

Compared with the pricey clinical version of the manual, you get a lot for your $24.95 ($22.21 with an Amazon Prime account). At 370 pages, the guide is an easily digestible compendium; the diagnoses are grouped as they are in the primary manual, although without specifiers or subsets. Instead, there are bulleted lists of risk factors and symptoms. Treatment options are also bulleted, as are tips for remaining compliant with treatment regimens.

There are case histories written in lay person language and even blurbs that offer encouragement to those who might be, however slightly, alarmed to learn about various illnesses described. For example, in the chapter about “disorders that start in childhood” (neurodevelopmental disorders), the reader is advised that “treatment can lead to learning new ways to manage symptoms … and it can also offer hope.”

Although it’s the first book written and published by the APA specifically for the general public, when I asked the guide’s editorial adviser, Dr. Jeffrey Borenstein, if primary care doctors, who are very often the ones on the front lines of diagnosing and treating mental illness, would also benefit from having a copy at hand, he said yes. But primary care physicians apparently were not foremost in the minds of the editorial board that compiled this guide and planned its utility.

According to Dr. Borenstein, the guide is intended for the general public. In an interview, however, he singled out in particular, teachers, clergy, and others whose job it is to serve the community at large.

Now that the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act means our health care system is moving inexorably toward value-based care and that physicians risk losing money if their overall patient panel outcomes – including mental health – are poor, understanding how to diagnose and appropriately treat mental and behavioral health issues is of growing concern, particularly in primary care.