User login

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. E-mail him at [email protected].

Patient Satisfaction Surveys Not Accurate Measure of Hospitalists’ Performance

Feeling frustrated with your group’s patient-satisfaction performance? Wondering why your chief (fill in the blank) officer glazes over when you try to explain why your hospitalist group’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and System (HCAHPS) scores for doctor communication are in a percentile rivaling the numeric age of your children?

It is likely that the C-suite administrator overseeing your hospitalist group has a portion of their pay based on HCAHPS or other patient-satisfaction (also called patient experience) scores. And for good reason: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program that started Oct. 1, 2012, has placed your hospital’s Medicare reimbursement at risk based on its HCAHPS scores.

HVBP and Patient Satisfaction

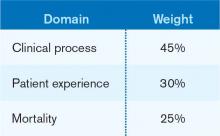

Patient satisfaction will remain an important part of HVBP in the coming years. Table 1 (below) shows the domains that will be included in fiscal years 2014 (which starts Oct. 1, 2013), 2015, and 2016. Table 2 (below) depicts the percent weighting the patient-satisfaction domain will receive through 2016. You may recall that HVBP is a program in which all hospitals place 1% to 2% (2013 through 2017, starting at 1% and increasing each year by 0.25% so that by 2017%, it is 2%) of their CMS inpatient payments in a withhold pool and, based on performance, can make back some, all, or an amount in excess of the amount placed in the withhold pool.

Source: Federal Register Vol. 78, No. 91; May 10, 2013; Proposed Rules, pp. 27609-27622.

Source: Federal Register Vol.78, No.91; May 10, 2013; Proposed Rules, pp. 27609-27622.

End In Itself

A colleague of mine recently asked, “Is an increase in patient satisfaction associated with higher quality of care and better patient safety?” The point here: It doesn’t matter. Patient satisfaction is an end in itself, and we should strive to maximize it, or at least put ourselves in the place of the patient and design care accordingly.

For Hospitalists: A Starting Point

There is a conundrum for hospitalists vis-à-vis patient satisfaction. Follow this chain of logic: The hospitals at which we work are incented to perform well on the HCAHPS domains. Hospitals pay a lot for hospitalists. Hospitalists can impact many of the HCAHPS domains. So shouldn’t hospitalists be judged according to HCAHPS scores?

Yes and no.

HCAHPS as a survey is intended to measure a patient’s overall experience of receiving care in the hospital. For example, from the “Doctor Communication” domain, we have questions like “how often did doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?” And “how often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand?”

These questions, like all in HCAHPS, are not designed to get at individual doctor performance, or even performance of a group of doctors, such as hospitalists. Instead, they are designed to measure a patient’s overall experience with the hospitalization, and “Doctor Communication” questions are designed to assess satisfaction with “doctors” collectively.

The Need for Hospitalist-Specific Satisfaction Surveys

So while HCAHPS is not designed to measure hospitalist performance with regard to patient satisfaction, it is a reasonable interim step for hospitals to judge hospitalists according to HCAHPS. However, this should be a bridge to a strategy that adopts hospitalist-specific patient-satisfaction questionnaires in the future and not an end in itself.

Why? Perhaps the biggest reason is that HCAHPS scores are neither specific nor timely enough to form the basis of improvement efforts for hospitalists. If a hospitalist receives a low score on the “Doctor Communication” domain, the scores are likely to be three to nine months old. How can we legitimately assign (and then modify) behaviors based on those scores?

Further, because the survey is not built to measure patient satisfaction specifically with hospitalists, the results are unlikely to engender meaningful and sustained behavior change. Hospitalists I talk to are generally bewildered and confused by HCAHPS scores attributed to them or their groups. Even if they understand the scores, I almost never see true quality improvement (plan-do-study-act) based on specific HCAHPS results. Instead, I see hospitalists trying to adhere to “best practices,” with no adjustments made along the way based on performance.

Nearly all the prominent patient satisfaction vendors have developed a survey instrument specifically designed for hospitalists. Each has an approach to appropriately attribute performance to the hospitalist in question, and each has a battery of questions that is designed to capture patient satisfaction with the hospitalist. Although use of these surveys involves an added financial commitment, I submit that because hospitalists have an unparalleled proximity to hospitalized patients, such an investment is worthy of consideration and has an accompanying business case, thanks to HVBP. The results of these surveys may form the basis of legitimate, targeted feedback to hospitalists, who may then adjust their approach to patient interactions. Such performance improvement should result in improved HCAHPS scores.

In sum, hospitalists should pay close attention to patient satisfaction and embrace HCAHPS. However, we should be looking beyond HCAHPS to survey instruments that fairly and accurately measure our performance. Such surveys will be more widely accepted by the hospitalists they are measuring, and will allow hospitalists to perform meaningful quality improvement based on the results. Although hospitalist-specific surveys will require an investment, the increased patient satisfaction that results should be the basis of a favorable return on that investment.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Feeling frustrated with your group’s patient-satisfaction performance? Wondering why your chief (fill in the blank) officer glazes over when you try to explain why your hospitalist group’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and System (HCAHPS) scores for doctor communication are in a percentile rivaling the numeric age of your children?

It is likely that the C-suite administrator overseeing your hospitalist group has a portion of their pay based on HCAHPS or other patient-satisfaction (also called patient experience) scores. And for good reason: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program that started Oct. 1, 2012, has placed your hospital’s Medicare reimbursement at risk based on its HCAHPS scores.

HVBP and Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction will remain an important part of HVBP in the coming years. Table 1 (below) shows the domains that will be included in fiscal years 2014 (which starts Oct. 1, 2013), 2015, and 2016. Table 2 (below) depicts the percent weighting the patient-satisfaction domain will receive through 2016. You may recall that HVBP is a program in which all hospitals place 1% to 2% (2013 through 2017, starting at 1% and increasing each year by 0.25% so that by 2017%, it is 2%) of their CMS inpatient payments in a withhold pool and, based on performance, can make back some, all, or an amount in excess of the amount placed in the withhold pool.

Source: Federal Register Vol. 78, No. 91; May 10, 2013; Proposed Rules, pp. 27609-27622.

Source: Federal Register Vol.78, No.91; May 10, 2013; Proposed Rules, pp. 27609-27622.

End In Itself

A colleague of mine recently asked, “Is an increase in patient satisfaction associated with higher quality of care and better patient safety?” The point here: It doesn’t matter. Patient satisfaction is an end in itself, and we should strive to maximize it, or at least put ourselves in the place of the patient and design care accordingly.

For Hospitalists: A Starting Point

There is a conundrum for hospitalists vis-à-vis patient satisfaction. Follow this chain of logic: The hospitals at which we work are incented to perform well on the HCAHPS domains. Hospitals pay a lot for hospitalists. Hospitalists can impact many of the HCAHPS domains. So shouldn’t hospitalists be judged according to HCAHPS scores?

Yes and no.

HCAHPS as a survey is intended to measure a patient’s overall experience of receiving care in the hospital. For example, from the “Doctor Communication” domain, we have questions like “how often did doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?” And “how often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand?”

These questions, like all in HCAHPS, are not designed to get at individual doctor performance, or even performance of a group of doctors, such as hospitalists. Instead, they are designed to measure a patient’s overall experience with the hospitalization, and “Doctor Communication” questions are designed to assess satisfaction with “doctors” collectively.

The Need for Hospitalist-Specific Satisfaction Surveys

So while HCAHPS is not designed to measure hospitalist performance with regard to patient satisfaction, it is a reasonable interim step for hospitals to judge hospitalists according to HCAHPS. However, this should be a bridge to a strategy that adopts hospitalist-specific patient-satisfaction questionnaires in the future and not an end in itself.

Why? Perhaps the biggest reason is that HCAHPS scores are neither specific nor timely enough to form the basis of improvement efforts for hospitalists. If a hospitalist receives a low score on the “Doctor Communication” domain, the scores are likely to be three to nine months old. How can we legitimately assign (and then modify) behaviors based on those scores?

Further, because the survey is not built to measure patient satisfaction specifically with hospitalists, the results are unlikely to engender meaningful and sustained behavior change. Hospitalists I talk to are generally bewildered and confused by HCAHPS scores attributed to them or their groups. Even if they understand the scores, I almost never see true quality improvement (plan-do-study-act) based on specific HCAHPS results. Instead, I see hospitalists trying to adhere to “best practices,” with no adjustments made along the way based on performance.

Nearly all the prominent patient satisfaction vendors have developed a survey instrument specifically designed for hospitalists. Each has an approach to appropriately attribute performance to the hospitalist in question, and each has a battery of questions that is designed to capture patient satisfaction with the hospitalist. Although use of these surveys involves an added financial commitment, I submit that because hospitalists have an unparalleled proximity to hospitalized patients, such an investment is worthy of consideration and has an accompanying business case, thanks to HVBP. The results of these surveys may form the basis of legitimate, targeted feedback to hospitalists, who may then adjust their approach to patient interactions. Such performance improvement should result in improved HCAHPS scores.

In sum, hospitalists should pay close attention to patient satisfaction and embrace HCAHPS. However, we should be looking beyond HCAHPS to survey instruments that fairly and accurately measure our performance. Such surveys will be more widely accepted by the hospitalists they are measuring, and will allow hospitalists to perform meaningful quality improvement based on the results. Although hospitalist-specific surveys will require an investment, the increased patient satisfaction that results should be the basis of a favorable return on that investment.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Feeling frustrated with your group’s patient-satisfaction performance? Wondering why your chief (fill in the blank) officer glazes over when you try to explain why your hospitalist group’s Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and System (HCAHPS) scores for doctor communication are in a percentile rivaling the numeric age of your children?

It is likely that the C-suite administrator overseeing your hospitalist group has a portion of their pay based on HCAHPS or other patient-satisfaction (also called patient experience) scores. And for good reason: The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Hospital Value-Based Purchasing (HVBP) program that started Oct. 1, 2012, has placed your hospital’s Medicare reimbursement at risk based on its HCAHPS scores.

HVBP and Patient Satisfaction

Patient satisfaction will remain an important part of HVBP in the coming years. Table 1 (below) shows the domains that will be included in fiscal years 2014 (which starts Oct. 1, 2013), 2015, and 2016. Table 2 (below) depicts the percent weighting the patient-satisfaction domain will receive through 2016. You may recall that HVBP is a program in which all hospitals place 1% to 2% (2013 through 2017, starting at 1% and increasing each year by 0.25% so that by 2017%, it is 2%) of their CMS inpatient payments in a withhold pool and, based on performance, can make back some, all, or an amount in excess of the amount placed in the withhold pool.

Source: Federal Register Vol. 78, No. 91; May 10, 2013; Proposed Rules, pp. 27609-27622.

Source: Federal Register Vol.78, No.91; May 10, 2013; Proposed Rules, pp. 27609-27622.

End In Itself

A colleague of mine recently asked, “Is an increase in patient satisfaction associated with higher quality of care and better patient safety?” The point here: It doesn’t matter. Patient satisfaction is an end in itself, and we should strive to maximize it, or at least put ourselves in the place of the patient and design care accordingly.

For Hospitalists: A Starting Point

There is a conundrum for hospitalists vis-à-vis patient satisfaction. Follow this chain of logic: The hospitals at which we work are incented to perform well on the HCAHPS domains. Hospitals pay a lot for hospitalists. Hospitalists can impact many of the HCAHPS domains. So shouldn’t hospitalists be judged according to HCAHPS scores?

Yes and no.

HCAHPS as a survey is intended to measure a patient’s overall experience of receiving care in the hospital. For example, from the “Doctor Communication” domain, we have questions like “how often did doctors treat you with courtesy and respect?” And “how often did doctors explain things in a way you could understand?”

These questions, like all in HCAHPS, are not designed to get at individual doctor performance, or even performance of a group of doctors, such as hospitalists. Instead, they are designed to measure a patient’s overall experience with the hospitalization, and “Doctor Communication” questions are designed to assess satisfaction with “doctors” collectively.

The Need for Hospitalist-Specific Satisfaction Surveys

So while HCAHPS is not designed to measure hospitalist performance with regard to patient satisfaction, it is a reasonable interim step for hospitals to judge hospitalists according to HCAHPS. However, this should be a bridge to a strategy that adopts hospitalist-specific patient-satisfaction questionnaires in the future and not an end in itself.

Why? Perhaps the biggest reason is that HCAHPS scores are neither specific nor timely enough to form the basis of improvement efforts for hospitalists. If a hospitalist receives a low score on the “Doctor Communication” domain, the scores are likely to be three to nine months old. How can we legitimately assign (and then modify) behaviors based on those scores?

Further, because the survey is not built to measure patient satisfaction specifically with hospitalists, the results are unlikely to engender meaningful and sustained behavior change. Hospitalists I talk to are generally bewildered and confused by HCAHPS scores attributed to them or their groups. Even if they understand the scores, I almost never see true quality improvement (plan-do-study-act) based on specific HCAHPS results. Instead, I see hospitalists trying to adhere to “best practices,” with no adjustments made along the way based on performance.

Nearly all the prominent patient satisfaction vendors have developed a survey instrument specifically designed for hospitalists. Each has an approach to appropriately attribute performance to the hospitalist in question, and each has a battery of questions that is designed to capture patient satisfaction with the hospitalist. Although use of these surveys involves an added financial commitment, I submit that because hospitalists have an unparalleled proximity to hospitalized patients, such an investment is worthy of consideration and has an accompanying business case, thanks to HVBP. The results of these surveys may form the basis of legitimate, targeted feedback to hospitalists, who may then adjust their approach to patient interactions. Such performance improvement should result in improved HCAHPS scores.

In sum, hospitalists should pay close attention to patient satisfaction and embrace HCAHPS. However, we should be looking beyond HCAHPS to survey instruments that fairly and accurately measure our performance. Such surveys will be more widely accepted by the hospitalists they are measuring, and will allow hospitalists to perform meaningful quality improvement based on the results. Although hospitalist-specific surveys will require an investment, the increased patient satisfaction that results should be the basis of a favorable return on that investment.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Bundled-Payment Program Basics

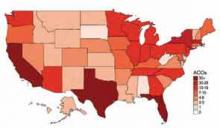

With general agreement that health-care costs in the U.S. are unsustainable, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), and the private sector are embarking on new approaches to cost containment. On the one hand, we have value-based purchasing (VBP), which rests on the existing fee-for-service system and aims for incremental change. On the other hand, we have accountable-care organizations (ACOs), which provide a global payment for a population of patients, and bundled-payment programs, which provide a single payment for an episode of care. These reimbursement models represent a fundamental change in how we pay for health care.

On a broad scale, ACOs may be further along in development than bundled-payment programs, even though pockets of bundling prototypes have existed for years. Examples include the Prometheus payment system, Geisinger’s ProvenCare, and CMS’ Acute Care Episode demonstration project, which bundled Part A (hospital) and Part B (doctors, others) payments for cardiac and orthopedic surgery procedures. Over the past two years, we have seen a dramatic uptick in bundling activity, including programs in a number of states (including Arkansas, California, and Massachusetts). Here at Baystate Health in Massachusetts, we kicked off a total-hip-replacement bundle with our subsidiary health plan in January 2011.

Perhaps most notably, bundled payments are part of the Affordable Care Act. The Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative, launched earlier this year by CMMI, is enrolling traditional Medicare patients in bundled-payment programs across the country at more than 400 health systems.

How Bundled Payments Work

Bundled-payment programs provide a single payment to hospitals, doctors, post-acute providers, and other providers (for home care, lab, medical equipment, etc.) for a defined episode of care. Most bundles encompass at least an acute hospital episode and physician payments for the episode; many include some period after hospitalization, covering rehabilitation at a facility or at home and doctors’ visits during recovery. Bundling goes beyond Medicare’s diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments, which reimburse hospitals for all elements of an inpatient hospital stay for a given diagnosis but do not include services performed by nonhospital providers.

How do the finances work in a bundled-payment program? A single price for an episode of care is determined based on historical performance, factoring in all the services one wishes to include in a bundle (e.g. hospital, doctor visits in hospital, home physical therapy, follow-up doctor visits, follow up X-ray and labs for a defined time period). If the hospital, doctors, and others in the bundle generate new efficiencies in care (e.g. due to better care coordination, less wasteful test ordering, or lower implant/device costs), the savings are then distributed to these providers. What if spending exceeds the predetermined price? In some instances, the health plan bears the financial risk; in other instances, the hospital, physicians, and other bundle providers must pay back the shortfall. Important to note is that all sharing of savings is contingent on attainment of or improvement in demonstrated quality-of-care measures relevant to the bundle. In the future, bundling will evolve from shared savings to a single prospective payment for a care episode.

For now, most bundles encompass surgical procedures, although CMMI is working with health systems on several medical bundles, including acute MI, COPD, and stroke. All of these bundles are initiated by an acute hospitalization. Other types of bundles exist, such as with chronic conditions or with post-acute care only. In Massachusetts, a pediatric asthma bundle is being implemented through Medicaid, covering that population for a year or longer. The aim is to redirect dollars that normally would pay for ED visits and inpatient care to pay for interventions that promote better control of the disease and prevent acute flare-ups that lead to hospital visits.

How Hospitalists Fit In

To date, there has been little discussion of how physicians other than the surgeons doing the procedure (most bundles are for surgeries) fit into the clinical or financial model underpinning the program. However, with most patients in surgical or medical bundles being discharged to home, we now recognize that primary-care physicians (PCPs) will be essential to the success of a bundle.

Similarly, with medically complex patients enrolling in surgical bundles, hospitalists will be essential to the pre- and perioperative care of these patients. Also, transitioning bundle patients to home or to a rehabilitation will benefit from the involvement of a hospitalist.

What You Can Do Today

Although this might seem abstract for hospitalists practicing in the here and now, there are compelling opportunities for hospitalists who get involved in bundled-payment programs. Here’s what I suggest:

Find out if your hospital or post-acute facility is participating in bundling by looking at a map of CMMI bundle programs here: http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments;

- Get a seat at the table working on the bundle; and

- Negotiate a portion of the bundle’s shared savings on the basis of 1) increased efficiency and quality resulting from hospitalist involvement and 2) hospitalist direct oversight of bundled patients in post-acute facilities (if you choose).

Post-acute care may be new for your hospitalist program. Bundling programs are an important new business case for hospitalists in this setting.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

With general agreement that health-care costs in the U.S. are unsustainable, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), and the private sector are embarking on new approaches to cost containment. On the one hand, we have value-based purchasing (VBP), which rests on the existing fee-for-service system and aims for incremental change. On the other hand, we have accountable-care organizations (ACOs), which provide a global payment for a population of patients, and bundled-payment programs, which provide a single payment for an episode of care. These reimbursement models represent a fundamental change in how we pay for health care.

On a broad scale, ACOs may be further along in development than bundled-payment programs, even though pockets of bundling prototypes have existed for years. Examples include the Prometheus payment system, Geisinger’s ProvenCare, and CMS’ Acute Care Episode demonstration project, which bundled Part A (hospital) and Part B (doctors, others) payments for cardiac and orthopedic surgery procedures. Over the past two years, we have seen a dramatic uptick in bundling activity, including programs in a number of states (including Arkansas, California, and Massachusetts). Here at Baystate Health in Massachusetts, we kicked off a total-hip-replacement bundle with our subsidiary health plan in January 2011.

Perhaps most notably, bundled payments are part of the Affordable Care Act. The Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative, launched earlier this year by CMMI, is enrolling traditional Medicare patients in bundled-payment programs across the country at more than 400 health systems.

How Bundled Payments Work

Bundled-payment programs provide a single payment to hospitals, doctors, post-acute providers, and other providers (for home care, lab, medical equipment, etc.) for a defined episode of care. Most bundles encompass at least an acute hospital episode and physician payments for the episode; many include some period after hospitalization, covering rehabilitation at a facility or at home and doctors’ visits during recovery. Bundling goes beyond Medicare’s diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments, which reimburse hospitals for all elements of an inpatient hospital stay for a given diagnosis but do not include services performed by nonhospital providers.

How do the finances work in a bundled-payment program? A single price for an episode of care is determined based on historical performance, factoring in all the services one wishes to include in a bundle (e.g. hospital, doctor visits in hospital, home physical therapy, follow-up doctor visits, follow up X-ray and labs for a defined time period). If the hospital, doctors, and others in the bundle generate new efficiencies in care (e.g. due to better care coordination, less wasteful test ordering, or lower implant/device costs), the savings are then distributed to these providers. What if spending exceeds the predetermined price? In some instances, the health plan bears the financial risk; in other instances, the hospital, physicians, and other bundle providers must pay back the shortfall. Important to note is that all sharing of savings is contingent on attainment of or improvement in demonstrated quality-of-care measures relevant to the bundle. In the future, bundling will evolve from shared savings to a single prospective payment for a care episode.

For now, most bundles encompass surgical procedures, although CMMI is working with health systems on several medical bundles, including acute MI, COPD, and stroke. All of these bundles are initiated by an acute hospitalization. Other types of bundles exist, such as with chronic conditions or with post-acute care only. In Massachusetts, a pediatric asthma bundle is being implemented through Medicaid, covering that population for a year or longer. The aim is to redirect dollars that normally would pay for ED visits and inpatient care to pay for interventions that promote better control of the disease and prevent acute flare-ups that lead to hospital visits.

How Hospitalists Fit In

To date, there has been little discussion of how physicians other than the surgeons doing the procedure (most bundles are for surgeries) fit into the clinical or financial model underpinning the program. However, with most patients in surgical or medical bundles being discharged to home, we now recognize that primary-care physicians (PCPs) will be essential to the success of a bundle.

Similarly, with medically complex patients enrolling in surgical bundles, hospitalists will be essential to the pre- and perioperative care of these patients. Also, transitioning bundle patients to home or to a rehabilitation will benefit from the involvement of a hospitalist.

What You Can Do Today

Although this might seem abstract for hospitalists practicing in the here and now, there are compelling opportunities for hospitalists who get involved in bundled-payment programs. Here’s what I suggest:

Find out if your hospital or post-acute facility is participating in bundling by looking at a map of CMMI bundle programs here: http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments;

- Get a seat at the table working on the bundle; and

- Negotiate a portion of the bundle’s shared savings on the basis of 1) increased efficiency and quality resulting from hospitalist involvement and 2) hospitalist direct oversight of bundled patients in post-acute facilities (if you choose).

Post-acute care may be new for your hospitalist program. Bundling programs are an important new business case for hospitalists in this setting.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

With general agreement that health-care costs in the U.S. are unsustainable, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI), and the private sector are embarking on new approaches to cost containment. On the one hand, we have value-based purchasing (VBP), which rests on the existing fee-for-service system and aims for incremental change. On the other hand, we have accountable-care organizations (ACOs), which provide a global payment for a population of patients, and bundled-payment programs, which provide a single payment for an episode of care. These reimbursement models represent a fundamental change in how we pay for health care.

On a broad scale, ACOs may be further along in development than bundled-payment programs, even though pockets of bundling prototypes have existed for years. Examples include the Prometheus payment system, Geisinger’s ProvenCare, and CMS’ Acute Care Episode demonstration project, which bundled Part A (hospital) and Part B (doctors, others) payments for cardiac and orthopedic surgery procedures. Over the past two years, we have seen a dramatic uptick in bundling activity, including programs in a number of states (including Arkansas, California, and Massachusetts). Here at Baystate Health in Massachusetts, we kicked off a total-hip-replacement bundle with our subsidiary health plan in January 2011.

Perhaps most notably, bundled payments are part of the Affordable Care Act. The Bundled Payments for Care Improvement initiative, launched earlier this year by CMMI, is enrolling traditional Medicare patients in bundled-payment programs across the country at more than 400 health systems.

How Bundled Payments Work

Bundled-payment programs provide a single payment to hospitals, doctors, post-acute providers, and other providers (for home care, lab, medical equipment, etc.) for a defined episode of care. Most bundles encompass at least an acute hospital episode and physician payments for the episode; many include some period after hospitalization, covering rehabilitation at a facility or at home and doctors’ visits during recovery. Bundling goes beyond Medicare’s diagnosis-related group (DRG) payments, which reimburse hospitals for all elements of an inpatient hospital stay for a given diagnosis but do not include services performed by nonhospital providers.

How do the finances work in a bundled-payment program? A single price for an episode of care is determined based on historical performance, factoring in all the services one wishes to include in a bundle (e.g. hospital, doctor visits in hospital, home physical therapy, follow-up doctor visits, follow up X-ray and labs for a defined time period). If the hospital, doctors, and others in the bundle generate new efficiencies in care (e.g. due to better care coordination, less wasteful test ordering, or lower implant/device costs), the savings are then distributed to these providers. What if spending exceeds the predetermined price? In some instances, the health plan bears the financial risk; in other instances, the hospital, physicians, and other bundle providers must pay back the shortfall. Important to note is that all sharing of savings is contingent on attainment of or improvement in demonstrated quality-of-care measures relevant to the bundle. In the future, bundling will evolve from shared savings to a single prospective payment for a care episode.

For now, most bundles encompass surgical procedures, although CMMI is working with health systems on several medical bundles, including acute MI, COPD, and stroke. All of these bundles are initiated by an acute hospitalization. Other types of bundles exist, such as with chronic conditions or with post-acute care only. In Massachusetts, a pediatric asthma bundle is being implemented through Medicaid, covering that population for a year or longer. The aim is to redirect dollars that normally would pay for ED visits and inpatient care to pay for interventions that promote better control of the disease and prevent acute flare-ups that lead to hospital visits.

How Hospitalists Fit In

To date, there has been little discussion of how physicians other than the surgeons doing the procedure (most bundles are for surgeries) fit into the clinical or financial model underpinning the program. However, with most patients in surgical or medical bundles being discharged to home, we now recognize that primary-care physicians (PCPs) will be essential to the success of a bundle.

Similarly, with medically complex patients enrolling in surgical bundles, hospitalists will be essential to the pre- and perioperative care of these patients. Also, transitioning bundle patients to home or to a rehabilitation will benefit from the involvement of a hospitalist.

What You Can Do Today

Although this might seem abstract for hospitalists practicing in the here and now, there are compelling opportunities for hospitalists who get involved in bundled-payment programs. Here’s what I suggest:

Find out if your hospital or post-acute facility is participating in bundling by looking at a map of CMMI bundle programs here: http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments;

- Get a seat at the table working on the bundle; and

- Negotiate a portion of the bundle’s shared savings on the basis of 1) increased efficiency and quality resulting from hospitalist involvement and 2) hospitalist direct oversight of bundled patients in post-acute facilities (if you choose).

Post-acute care may be new for your hospitalist program. Bundling programs are an important new business case for hospitalists in this setting.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Commemorating Round-the-Clock Hospital Medicine Programs

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?

A: The reasons were primarily economic. No. 1, the hospital was losing market share because local physicians would prefer to admit to the teaching hospital [a nearby competitor], where they were not required to come in during the middle of the night. No. 2, the cost of a hospitalization managed by a hospitalist was less expensive than either a hospital stay managed by house staff or managed over the telephone by a private attending at home.

Q: What was the most difficult operational challenge for the program?

A: Effective and timely communication with the community physicians was the most difficult operational challenge. Access to outpatient medical treatment immediately prior to a hospitalization and timely communication to the community physician were both challenges that we never adequately solved in the early days. I understand that these issues can still be problematic.

Q: How was it received by patients?

A: Overall, patients were very happy with the system. In the old system, with a typical four-physician practice, a patient had only a 1 in 4 chance of being admitted by the doctor who was familiar with the case. The fact that the hospitalist was available in the hospital made the improvement in quality apparent to most patients.

Q: How did you get the medical staff to buy into the program?

A: I personally visited every private physician who participated. Physicians were given the option of not participating, or of part-time participation—for example, on weekends or holidays only. The word spread. Physicians came up to me and told me that the program enabled them to continue practicing for another five years. Physicians’ spouses thanked me.

Q: Are you surprised HM as a field has grown so quickly?

A: I am not really that surprised. It is a better way to organize health care. I am surprised that it did not occur sooner. We talked about instituting this system for 10 years before 1993.

Q: What big challenges remain for hospital medicine? What are some solutions?

A: I believe that the biggest global challenge for hospital medicine remains communication with community-based providers, both before the hospitalization as well as during hospitalization and immediately after discharge. In the era of the EMR, the Internet, and the iPhone and Android, this should be easier. HIPAA has not helped.

The other growing challenge will become apparent as hospitalists age in the profession: Disruption of the diurnal sleep cycle becomes increasingly problematic for many physicians after the age of 50 and can easily lead to burnout. The early hospitalists were all in their 30s. The attractive lifestyle choice for the 30-year-old can lead to burnout for the 55-year-old. The emergency-medicine literature has noted a similar problem of shift work/sleep fragmentation.

Final Thoughts

I believe Dr. Holbrook’s assessments on the future of our specialty are on target. As HM continues to mature, we need to continue to focus on how we communicate with providers outside the four walls of the hospital and how to address barriers to making HM a sustainable career.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

(Editor's note: Updated July 12, 2013.)

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?

A: The reasons were primarily economic. No. 1, the hospital was losing market share because local physicians would prefer to admit to the teaching hospital [a nearby competitor], where they were not required to come in during the middle of the night. No. 2, the cost of a hospitalization managed by a hospitalist was less expensive than either a hospital stay managed by house staff or managed over the telephone by a private attending at home.

Q: What was the most difficult operational challenge for the program?

A: Effective and timely communication with the community physicians was the most difficult operational challenge. Access to outpatient medical treatment immediately prior to a hospitalization and timely communication to the community physician were both challenges that we never adequately solved in the early days. I understand that these issues can still be problematic.

Q: How was it received by patients?

A: Overall, patients were very happy with the system. In the old system, with a typical four-physician practice, a patient had only a 1 in 4 chance of being admitted by the doctor who was familiar with the case. The fact that the hospitalist was available in the hospital made the improvement in quality apparent to most patients.

Q: How did you get the medical staff to buy into the program?

A: I personally visited every private physician who participated. Physicians were given the option of not participating, or of part-time participation—for example, on weekends or holidays only. The word spread. Physicians came up to me and told me that the program enabled them to continue practicing for another five years. Physicians’ spouses thanked me.

Q: Are you surprised HM as a field has grown so quickly?

A: I am not really that surprised. It is a better way to organize health care. I am surprised that it did not occur sooner. We talked about instituting this system for 10 years before 1993.

Q: What big challenges remain for hospital medicine? What are some solutions?

A: I believe that the biggest global challenge for hospital medicine remains communication with community-based providers, both before the hospitalization as well as during hospitalization and immediately after discharge. In the era of the EMR, the Internet, and the iPhone and Android, this should be easier. HIPAA has not helped.

The other growing challenge will become apparent as hospitalists age in the profession: Disruption of the diurnal sleep cycle becomes increasingly problematic for many physicians after the age of 50 and can easily lead to burnout. The early hospitalists were all in their 30s. The attractive lifestyle choice for the 30-year-old can lead to burnout for the 55-year-old. The emergency-medicine literature has noted a similar problem of shift work/sleep fragmentation.

Final Thoughts

I believe Dr. Holbrook’s assessments on the future of our specialty are on target. As HM continues to mature, we need to continue to focus on how we communicate with providers outside the four walls of the hospital and how to address barriers to making HM a sustainable career.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

(Editor's note: Updated July 12, 2013.)

The steam engine. The telephone. Television. ATMs. The Internet. Smartphones. The 24/7 hospitalist program.

Perhaps the single most important innovation along the road to where we are now in HM has been the development of the hospital-sponsored, 24/7, on-site hospitalist program. And the father of this invention may be the most significant figure in HM you’ve never heard of: John Holbrook, MD, FACEP. An emergency-medicine physician since the mid-1970s, Dr. Holbrook did something in July 1993 that was considered off the wall, yet proved to be revolutionary: From nothing, he launched a 24/7 hospitalist program staffed with board-eligible and board-certified internists at Mercy Hospital in Springfield, Mass. The inpatient physicians (this was before the word “hospitalist” came to be) were employed by a subsidiary of the hospital and worked in place of community primary-care physicians (PCPs), taking care of hospitalized patients who did not have a PCP, or whose PCP chose not to come to the hospital.

Of great significance, from the beginning, and perhaps by unintentional design, these physicians were agents of change and improvement for the hospital itself.

To be sure, in places like Southern California, 24/7, on-site hospitalist programs were in place in the late 1980s. Some claim those programs may have been the birthplace of the hospitalist model. However, such programs came to be in order to help medical groups manage full capitated risk delegated to them from HMOs on a population of patients, and were not supported by the hospital, per se. This is distinct from hospitalist programs—such as Mercy’s—sponsored by hospitals (whether employed or contracted) in predominantly fee-for-service markets, which then comprised the lion’s share of the U.S. market.

I had the extraordinary good fortune to happen along in July 1994, get hired by Dr. Holbrook, and soon after begin serving as medical director for the Mercy program, which I would do for the next decade. To this day, Dr. Holbrook is a mentor and trusted advisor to me. I caught up with him in recognition of the 20th anniversary of the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service.

Question: What gave you the idea to launch what was, at the time, considered such an unconventional program?

Answer: Before the specialty of emergency medicine, a patient’s private physician would be called in most cases when a patient present in the ED: 25 or 50 doctors might be called over 24 hours, each to see one patient each. The inefficiency and disruption caused by this system was a natural and logical stimulus to develop the specialty of emergency medicine. I saw hospitalist medicine as an exact analogy.

Q: What were you observing in the healthcare environment that drove you to create the Mercy Inpatient Medicine Service?

A: Working for many years in the emergency department of a community hospital without a house staff, the ED docs would admit a patient at night or on the weekend and the attending physician would often plan to see the patient “in the morning.” When the patient would decompensate in the middle of the night, the ED doc would get a call to run to the floor to “Band-Aid” the situation.

Q: How did you convince the board of trustees to fund it?

A: The reasons were primarily economic. No. 1, the hospital was losing market share because local physicians would prefer to admit to the teaching hospital [a nearby competitor], where they were not required to come in during the middle of the night. No. 2, the cost of a hospitalization managed by a hospitalist was less expensive than either a hospital stay managed by house staff or managed over the telephone by a private attending at home.

Q: What was the most difficult operational challenge for the program?

A: Effective and timely communication with the community physicians was the most difficult operational challenge. Access to outpatient medical treatment immediately prior to a hospitalization and timely communication to the community physician were both challenges that we never adequately solved in the early days. I understand that these issues can still be problematic.

Q: How was it received by patients?

A: Overall, patients were very happy with the system. In the old system, with a typical four-physician practice, a patient had only a 1 in 4 chance of being admitted by the doctor who was familiar with the case. The fact that the hospitalist was available in the hospital made the improvement in quality apparent to most patients.

Q: How did you get the medical staff to buy into the program?

A: I personally visited every private physician who participated. Physicians were given the option of not participating, or of part-time participation—for example, on weekends or holidays only. The word spread. Physicians came up to me and told me that the program enabled them to continue practicing for another five years. Physicians’ spouses thanked me.

Q: Are you surprised HM as a field has grown so quickly?

A: I am not really that surprised. It is a better way to organize health care. I am surprised that it did not occur sooner. We talked about instituting this system for 10 years before 1993.

Q: What big challenges remain for hospital medicine? What are some solutions?

A: I believe that the biggest global challenge for hospital medicine remains communication with community-based providers, both before the hospitalization as well as during hospitalization and immediately after discharge. In the era of the EMR, the Internet, and the iPhone and Android, this should be easier. HIPAA has not helped.

The other growing challenge will become apparent as hospitalists age in the profession: Disruption of the diurnal sleep cycle becomes increasingly problematic for many physicians after the age of 50 and can easily lead to burnout. The early hospitalists were all in their 30s. The attractive lifestyle choice for the 30-year-old can lead to burnout for the 55-year-old. The emergency-medicine literature has noted a similar problem of shift work/sleep fragmentation.

Final Thoughts

I believe Dr. Holbrook’s assessments on the future of our specialty are on target. As HM continues to mature, we need to continue to focus on how we communicate with providers outside the four walls of the hospital and how to address barriers to making HM a sustainable career.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

(Editor's note: Updated July 12, 2013.)

Behavioral Economics Can Accelerate Adoption of Choosing Wisely Campaign

SHM has gotten behind the Choosing Wisely campaign in a big way. Earlier this year, SHM announced lists of suggested practices for adult and pediatric hospital medicine (see Table 1). To keep it on the front burner, hospitalists John Bulger and Ian Jenkins held a pre-course at HM13 devoted entirely to quality-improvement (QI) approaches to implementing and sustaining the practices outlined in the campaign. During the main meeting, they did an encore presentation, with Doug Carlson and Ricardo Quinonez presenting the elements of Choosing Wisely for pediatric hospital medicine.

The widely publicized campaign arose from an American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation grant program to “facilitate the development of innovative, emerging strategies to advance appropriate health-care decision-making and stewardship of health-care resources.” (For more information, visit www.abimfoundation.org.)

Adoption of many of the suggested Choosing Wisely practices will require a change in deeply ingrained, habitual behaviors. We assert that rational, reflective, cognitive processes might not be enough to overturn these behaviors, and that we must look to other mental systems to achieve the consistent adoption of the campaign’s suggested practices. An analogy exists in economics, where theories behind classical economics are challenged by behavioral economics.

What is behavioral economics? Classical economics asserts the individual as “homo economicus”: a person making rational, predictable decisions to advance their interests. However, due to social or professional influence, behavior often does not comport to expected ends. We succumb, sympathize, or follow the pack, diverging from the rulebook. Behavioral economics attempts to understand and compensate for these deviations.

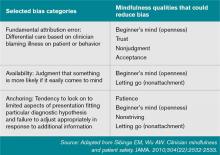

In medicine, we often yield to cognitive biases. To simplify decision-making, we generalize our observations to arrive at decisions quickly. Daniel Kahneman, winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, describes Type I thinking as fast and automatic, and Type II thinking as slow and effortful. Using Kahneman’s framework, we attempt to understand where reasoning may stray and, in turn, introduce environmental changes to achieve better outcomes.

How does this relate to Choosing Wisely? Embracing and embedding the practices of the Choosing Wisely campaign in day-to-day practice will require change in how we approach the clinical decisions we make each day. How can we create the conditions so as not to yield to the status quo?

The MINDSPACE framework

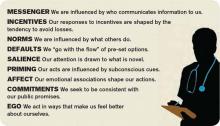

King et al in a recent Health Affairs article describe the MINDSPACE framework (see Table 2), which captures nine effects on behavior—messenger, incentives, norms, defaults, salience, priming, affect, commitments, and ego—that mostly involve automatic systems (Kahneman’s Type I), and how we can leverage them to minimize ineffective health care.1 Below, we describe Choosing Wisely’s HM components and how MINDSPACE can help promote better practice.

Messenger refers to the importance we place on the source of information conveyed to us. In the campaign, the ABIM Foundation engaged professional societies to come up with a list of specialty-specific practices. We know physicians pay more attention to messages from professional societies than, for example, insurance companies. Having the chair of medicine, the chief of hospital medicine, or the vice president of quality officially sanction the campaign’s practices at your organization leverages messengers.

Incentives, while widely used in health care, have had mixed results in terms of their utility in improving outcomes. People are loss-averse, and behavioral economics leverages that finding, which means incentives structured as penalties seem to have more powerful effects than bonuses. While the familiar pay-for-performance programs might not yield desired results, the evidence base continues to grow, and we have lots to learn. Does a 2% bonus change culture? What would really facilitate modifications in your test ordering patterns?

Norms, or what we perceive as the views of the majority, shape our behavior. How do we establish new ones? We all know the axiom “culture eats strategy for breakfast,” and, like patterned antibiotic administration, redirecting behavior requires examination of why we order items. Often, we order not because the drug combination conforms to standards, but because our training programs imbue us with less-than-ideal habits. These habits become standards, and their root causes require layered examination.

Defaults suggest that we are more likely to embrace a certain behavior if we otherwise need to “opt out” to avoid the behavior. We know that, for example, automatic enrollment in retirement savings plans has dramatically increased participation in such programs. For the Choosing Wisely campaign, the suggested practices should be set up as the default option. Examples include appropriate auto-stop orders for urinary catheters, telemetry, oximetry, or the requirement for added clicks to order daily CBCs. Think about ED orders and how they become substitute defaults once patients arrive on the wards. How do you disrupt the inertia?

Salience is when an individual makes a decision based on what is novel or what their attention is drawn to. Anticipating what subspecialists might expect, what your CMO demands, or what trainees envisage in their supervising attendings all may subconsciously override best judgment and deter best practice.

Priming describes how simple cues—often detected by our subconscious—influence decisions we make. When a physician, perhaps out of concern but often due to poorly reasoned or cavalier messaging, scribes “consider test X,” we involuntarily complete the act. We assume, because of the prime, that we need to act accordingly.

Affect is when we rely on gut feelings to make decisions. Emotions guide our ordering a urinary catheter for incontinence or transfusing to a HGB of 10, even when evidence contradicts what we might know as correct. Countering these actions requires credible stops to convert our emotions to reason (think clinical decision support with teeth).

Commitments are made in advance of an undertaking, behavioral economics suggests, as a way to combat the moment when willpower fails and desired behaviors go by the wayside. By publically signing a contract, in front of your group, chair, or medical director, and going on record as having pledged something, chances of success increase.

Ego, which underpins the need for a positive self-image, can drive the kind of automatic behavior that enables one to compare favorably to others. This effect has driven much of the motivation to perform well on public reporting of hospital quality measures. But ideal reporting of results must be valid; otherwise, attribution of subpar outcomes justifies the usual refrains of “not my responsibility” or the “system needs fixing, not me.”

Conclusions

Choosing Wisely is an ambitious undertaking made up of more than 90 suggested best practices put forth by 25 medical societies. In their book “Nudge,” authors Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein describe how automatic behaviors arise from the environment or context in which choices to engage in such behaviors are presented.2 For the Choosing Wisely campaign to have staying power, we submit that institutional leaders and front-line clinicians will need to create a context where the safest, most cost-effective choices are the automatic, or nearly automatic, ones.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected]. Dr. Flansbaum is director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and an SHM Public Policy Committee member.

References

- King D, Greaves F, Vlaev I, Darzi A. Approaches based on behavioral economics could help nudge patients and providers toward lower health spending growth. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(4):661-668.

- Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press; 2008.

SHM has gotten behind the Choosing Wisely campaign in a big way. Earlier this year, SHM announced lists of suggested practices for adult and pediatric hospital medicine (see Table 1). To keep it on the front burner, hospitalists John Bulger and Ian Jenkins held a pre-course at HM13 devoted entirely to quality-improvement (QI) approaches to implementing and sustaining the practices outlined in the campaign. During the main meeting, they did an encore presentation, with Doug Carlson and Ricardo Quinonez presenting the elements of Choosing Wisely for pediatric hospital medicine.

The widely publicized campaign arose from an American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation grant program to “facilitate the development of innovative, emerging strategies to advance appropriate health-care decision-making and stewardship of health-care resources.” (For more information, visit www.abimfoundation.org.)

Adoption of many of the suggested Choosing Wisely practices will require a change in deeply ingrained, habitual behaviors. We assert that rational, reflective, cognitive processes might not be enough to overturn these behaviors, and that we must look to other mental systems to achieve the consistent adoption of the campaign’s suggested practices. An analogy exists in economics, where theories behind classical economics are challenged by behavioral economics.

What is behavioral economics? Classical economics asserts the individual as “homo economicus”: a person making rational, predictable decisions to advance their interests. However, due to social or professional influence, behavior often does not comport to expected ends. We succumb, sympathize, or follow the pack, diverging from the rulebook. Behavioral economics attempts to understand and compensate for these deviations.

In medicine, we often yield to cognitive biases. To simplify decision-making, we generalize our observations to arrive at decisions quickly. Daniel Kahneman, winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, describes Type I thinking as fast and automatic, and Type II thinking as slow and effortful. Using Kahneman’s framework, we attempt to understand where reasoning may stray and, in turn, introduce environmental changes to achieve better outcomes.

How does this relate to Choosing Wisely? Embracing and embedding the practices of the Choosing Wisely campaign in day-to-day practice will require change in how we approach the clinical decisions we make each day. How can we create the conditions so as not to yield to the status quo?

The MINDSPACE framework

King et al in a recent Health Affairs article describe the MINDSPACE framework (see Table 2), which captures nine effects on behavior—messenger, incentives, norms, defaults, salience, priming, affect, commitments, and ego—that mostly involve automatic systems (Kahneman’s Type I), and how we can leverage them to minimize ineffective health care.1 Below, we describe Choosing Wisely’s HM components and how MINDSPACE can help promote better practice.

Messenger refers to the importance we place on the source of information conveyed to us. In the campaign, the ABIM Foundation engaged professional societies to come up with a list of specialty-specific practices. We know physicians pay more attention to messages from professional societies than, for example, insurance companies. Having the chair of medicine, the chief of hospital medicine, or the vice president of quality officially sanction the campaign’s practices at your organization leverages messengers.

Incentives, while widely used in health care, have had mixed results in terms of their utility in improving outcomes. People are loss-averse, and behavioral economics leverages that finding, which means incentives structured as penalties seem to have more powerful effects than bonuses. While the familiar pay-for-performance programs might not yield desired results, the evidence base continues to grow, and we have lots to learn. Does a 2% bonus change culture? What would really facilitate modifications in your test ordering patterns?

Norms, or what we perceive as the views of the majority, shape our behavior. How do we establish new ones? We all know the axiom “culture eats strategy for breakfast,” and, like patterned antibiotic administration, redirecting behavior requires examination of why we order items. Often, we order not because the drug combination conforms to standards, but because our training programs imbue us with less-than-ideal habits. These habits become standards, and their root causes require layered examination.

Defaults suggest that we are more likely to embrace a certain behavior if we otherwise need to “opt out” to avoid the behavior. We know that, for example, automatic enrollment in retirement savings plans has dramatically increased participation in such programs. For the Choosing Wisely campaign, the suggested practices should be set up as the default option. Examples include appropriate auto-stop orders for urinary catheters, telemetry, oximetry, or the requirement for added clicks to order daily CBCs. Think about ED orders and how they become substitute defaults once patients arrive on the wards. How do you disrupt the inertia?

Salience is when an individual makes a decision based on what is novel or what their attention is drawn to. Anticipating what subspecialists might expect, what your CMO demands, or what trainees envisage in their supervising attendings all may subconsciously override best judgment and deter best practice.

Priming describes how simple cues—often detected by our subconscious—influence decisions we make. When a physician, perhaps out of concern but often due to poorly reasoned or cavalier messaging, scribes “consider test X,” we involuntarily complete the act. We assume, because of the prime, that we need to act accordingly.

Affect is when we rely on gut feelings to make decisions. Emotions guide our ordering a urinary catheter for incontinence or transfusing to a HGB of 10, even when evidence contradicts what we might know as correct. Countering these actions requires credible stops to convert our emotions to reason (think clinical decision support with teeth).

Commitments are made in advance of an undertaking, behavioral economics suggests, as a way to combat the moment when willpower fails and desired behaviors go by the wayside. By publically signing a contract, in front of your group, chair, or medical director, and going on record as having pledged something, chances of success increase.

Ego, which underpins the need for a positive self-image, can drive the kind of automatic behavior that enables one to compare favorably to others. This effect has driven much of the motivation to perform well on public reporting of hospital quality measures. But ideal reporting of results must be valid; otherwise, attribution of subpar outcomes justifies the usual refrains of “not my responsibility” or the “system needs fixing, not me.”

Conclusions

Choosing Wisely is an ambitious undertaking made up of more than 90 suggested best practices put forth by 25 medical societies. In their book “Nudge,” authors Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein describe how automatic behaviors arise from the environment or context in which choices to engage in such behaviors are presented.2 For the Choosing Wisely campaign to have staying power, we submit that institutional leaders and front-line clinicians will need to create a context where the safest, most cost-effective choices are the automatic, or nearly automatic, ones.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected]. Dr. Flansbaum is director of hospitalist services at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and an SHM Public Policy Committee member.

References

- King D, Greaves F, Vlaev I, Darzi A. Approaches based on behavioral economics could help nudge patients and providers toward lower health spending growth. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(4):661-668.

- Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth and happiness. New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press; 2008.

SHM has gotten behind the Choosing Wisely campaign in a big way. Earlier this year, SHM announced lists of suggested practices for adult and pediatric hospital medicine (see Table 1). To keep it on the front burner, hospitalists John Bulger and Ian Jenkins held a pre-course at HM13 devoted entirely to quality-improvement (QI) approaches to implementing and sustaining the practices outlined in the campaign. During the main meeting, they did an encore presentation, with Doug Carlson and Ricardo Quinonez presenting the elements of Choosing Wisely for pediatric hospital medicine.

The widely publicized campaign arose from an American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) Foundation grant program to “facilitate the development of innovative, emerging strategies to advance appropriate health-care decision-making and stewardship of health-care resources.” (For more information, visit www.abimfoundation.org.)

Adoption of many of the suggested Choosing Wisely practices will require a change in deeply ingrained, habitual behaviors. We assert that rational, reflective, cognitive processes might not be enough to overturn these behaviors, and that we must look to other mental systems to achieve the consistent adoption of the campaign’s suggested practices. An analogy exists in economics, where theories behind classical economics are challenged by behavioral economics.

What is behavioral economics? Classical economics asserts the individual as “homo economicus”: a person making rational, predictable decisions to advance their interests. However, due to social or professional influence, behavior often does not comport to expected ends. We succumb, sympathize, or follow the pack, diverging from the rulebook. Behavioral economics attempts to understand and compensate for these deviations.

In medicine, we often yield to cognitive biases. To simplify decision-making, we generalize our observations to arrive at decisions quickly. Daniel Kahneman, winner of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, describes Type I thinking as fast and automatic, and Type II thinking as slow and effortful. Using Kahneman’s framework, we attempt to understand where reasoning may stray and, in turn, introduce environmental changes to achieve better outcomes.

How does this relate to Choosing Wisely? Embracing and embedding the practices of the Choosing Wisely campaign in day-to-day practice will require change in how we approach the clinical decisions we make each day. How can we create the conditions so as not to yield to the status quo?

The MINDSPACE framework

King et al in a recent Health Affairs article describe the MINDSPACE framework (see Table 2), which captures nine effects on behavior—messenger, incentives, norms, defaults, salience, priming, affect, commitments, and ego—that mostly involve automatic systems (Kahneman’s Type I), and how we can leverage them to minimize ineffective health care.1 Below, we describe Choosing Wisely’s HM components and how MINDSPACE can help promote better practice.

Messenger refers to the importance we place on the source of information conveyed to us. In the campaign, the ABIM Foundation engaged professional societies to come up with a list of specialty-specific practices. We know physicians pay more attention to messages from professional societies than, for example, insurance companies. Having the chair of medicine, the chief of hospital medicine, or the vice president of quality officially sanction the campaign’s practices at your organization leverages messengers.

Incentives, while widely used in health care, have had mixed results in terms of their utility in improving outcomes. People are loss-averse, and behavioral economics leverages that finding, which means incentives structured as penalties seem to have more powerful effects than bonuses. While the familiar pay-for-performance programs might not yield desired results, the evidence base continues to grow, and we have lots to learn. Does a 2% bonus change culture? What would really facilitate modifications in your test ordering patterns?

Norms, or what we perceive as the views of the majority, shape our behavior. How do we establish new ones? We all know the axiom “culture eats strategy for breakfast,” and, like patterned antibiotic administration, redirecting behavior requires examination of why we order items. Often, we order not because the drug combination conforms to standards, but because our training programs imbue us with less-than-ideal habits. These habits become standards, and their root causes require layered examination.

Defaults suggest that we are more likely to embrace a certain behavior if we otherwise need to “opt out” to avoid the behavior. We know that, for example, automatic enrollment in retirement savings plans has dramatically increased participation in such programs. For the Choosing Wisely campaign, the suggested practices should be set up as the default option. Examples include appropriate auto-stop orders for urinary catheters, telemetry, oximetry, or the requirement for added clicks to order daily CBCs. Think about ED orders and how they become substitute defaults once patients arrive on the wards. How do you disrupt the inertia?

Salience is when an individual makes a decision based on what is novel or what their attention is drawn to. Anticipating what subspecialists might expect, what your CMO demands, or what trainees envisage in their supervising attendings all may subconsciously override best judgment and deter best practice.

Priming describes how simple cues—often detected by our subconscious—influence decisions we make. When a physician, perhaps out of concern but often due to poorly reasoned or cavalier messaging, scribes “consider test X,” we involuntarily complete the act. We assume, because of the prime, that we need to act accordingly.

Affect is when we rely on gut feelings to make decisions. Emotions guide our ordering a urinary catheter for incontinence or transfusing to a HGB of 10, even when evidence contradicts what we might know as correct. Countering these actions requires credible stops to convert our emotions to reason (think clinical decision support with teeth).

Commitments are made in advance of an undertaking, behavioral economics suggests, as a way to combat the moment when willpower fails and desired behaviors go by the wayside. By publically signing a contract, in front of your group, chair, or medical director, and going on record as having pledged something, chances of success increase.