User login

Dr. Whitcomb is chief medical officer of Remedy Partners. He is co-founder and past president of SHM. E-mail him at [email protected].

Win Whitcomb: Hospitalists Must Grin and Bear the Hospital-Acquired Conditions Program

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

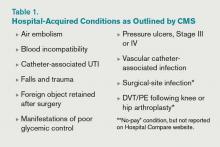

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Win Whitcomb: Hospital Readmissions Penalties Start Now

The uproar and confusion over readmissions penalties has consumed umpteen hours of senior leaders’ time (especially that of CFOs), not to mention that of front-line nurses, case managers, quality-improvement (QI) coordinators, hospitalists, and others involved in discharge planning and ensuring a safe transition for patients out of the hospital. For many, the math is fuzzy, and for most, the return on investment is even fuzzier. After all, avoided readmissions are lost revenue to those who are running a business known as an acute-care hospital.

Let me start with the conclusion: Eliminating avoidable readmissions is the right thing to do, period. But the financial downside to doing so is probably greater than any upside realized through avoidance of the penalties that began affecting hospital payments on Oct. 1—at least in the fee-for-service world we live in. At some point in the future, when most patients are under a global payment, the math might be clearer, but today, penalties probably won’t offset lost revenue from reduced readmissions added to the cost of paying lots of people to work in meetings (and at the bedside) to devise better care transitions. (Caveat: If your hospital is bursting at the seams with full occupancy, reducing readmissions and replacing them with higher-reimbursing patients, such as those undergoing elective major surgery, likely will be a net financial gain for your hospital.)

Part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) will reduce total Medicare DRG reimbursement for hospitals beginning in fiscal-year 2013 based on actual 30-day readmission rates for myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia that are in excess of risk-adjusted expected rates. The reduction is capped at 1% in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 3% in 2015 and beyond. Hospital readmission rates are based on calculated baseline rates using Medicare data from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011.

Cost of a Readmissions-Reduction Program

How much does it cost for a hospital to implement a care-transitions program—such as SHM’s Project BOOST—to reduce readmissions? Last year, I interviewed a dozen hospitals that successfully implemented SHM’s formal mentored implementation program. The result? In the first year of the program, hospitals spent about $170,000 on training and staff time devoted to the project.

Lost Revenue

Let’s look at a sample penalty calculation, then examine a scenario sizing up how revenue is lost when a hospital is successful in reducing readmissions. The ACA defines the payments for excess readmissions as:

The number of patients with the applicable condition (HF, MI, or pneumonia) multiplied by the base DRG payment made for those patients multiplied by the percentage of readmissions beyond the expected.

As an example, let’s take a hospital that treats 500 pneumonia patients (# with the applicable condition), has a base DRG payment for pneumonia of $5,000, and a readmission rate that is 4% higher than expected (in this example, the actual rate is 25% and the expected rate is 24%; 1/25=4%). The penalty is 500 X $5,000 X .04, or $100,000. We’ll assume that the readmission rate for myocardial infarction and heart failure are less than expected, so the total penalty is $100,000.

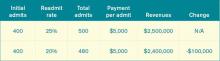

Let’s say the hospital works hard to decrease pneumonia readmissions from 25% to 20% and avoids the penalty. As outlined in Table 1, the hospital will lose $100,000 in revenue (admittedly, reducing readmissions to 20% from 25% represents a big jump, but this is for illustration purposes—we haven’t added in lost revenue from reduced readmissions for other conditions). What’s the final cost of avoiding the $100,000 readmission penalty? Lost revenue of $100,000 plus the cost of implementing the readmission reduction program of $170,000=$270,000.

Why Are We Doing This?

I see the value in care transitions and readmissions-reduction programs, such as Project BOOST, first and foremost as a way to improve patient safety; as such, if implemented effectively, they are likely worth the investment. Second, their value lies in the preparation all hospitals and health systems should be undergoing to remain market-competitive and solvent under global payment systems. Because the penalties in the HRRP might come with lost revenues and the costs of program implementation, be clear about your team’s motivation for reducing readmissions. Your CFO will see to it if I don’t.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The uproar and confusion over readmissions penalties has consumed umpteen hours of senior leaders’ time (especially that of CFOs), not to mention that of front-line nurses, case managers, quality-improvement (QI) coordinators, hospitalists, and others involved in discharge planning and ensuring a safe transition for patients out of the hospital. For many, the math is fuzzy, and for most, the return on investment is even fuzzier. After all, avoided readmissions are lost revenue to those who are running a business known as an acute-care hospital.

Let me start with the conclusion: Eliminating avoidable readmissions is the right thing to do, period. But the financial downside to doing so is probably greater than any upside realized through avoidance of the penalties that began affecting hospital payments on Oct. 1—at least in the fee-for-service world we live in. At some point in the future, when most patients are under a global payment, the math might be clearer, but today, penalties probably won’t offset lost revenue from reduced readmissions added to the cost of paying lots of people to work in meetings (and at the bedside) to devise better care transitions. (Caveat: If your hospital is bursting at the seams with full occupancy, reducing readmissions and replacing them with higher-reimbursing patients, such as those undergoing elective major surgery, likely will be a net financial gain for your hospital.)

Part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) will reduce total Medicare DRG reimbursement for hospitals beginning in fiscal-year 2013 based on actual 30-day readmission rates for myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia that are in excess of risk-adjusted expected rates. The reduction is capped at 1% in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 3% in 2015 and beyond. Hospital readmission rates are based on calculated baseline rates using Medicare data from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011.

Cost of a Readmissions-Reduction Program

How much does it cost for a hospital to implement a care-transitions program—such as SHM’s Project BOOST—to reduce readmissions? Last year, I interviewed a dozen hospitals that successfully implemented SHM’s formal mentored implementation program. The result? In the first year of the program, hospitals spent about $170,000 on training and staff time devoted to the project.

Lost Revenue

Let’s look at a sample penalty calculation, then examine a scenario sizing up how revenue is lost when a hospital is successful in reducing readmissions. The ACA defines the payments for excess readmissions as:

The number of patients with the applicable condition (HF, MI, or pneumonia) multiplied by the base DRG payment made for those patients multiplied by the percentage of readmissions beyond the expected.

As an example, let’s take a hospital that treats 500 pneumonia patients (# with the applicable condition), has a base DRG payment for pneumonia of $5,000, and a readmission rate that is 4% higher than expected (in this example, the actual rate is 25% and the expected rate is 24%; 1/25=4%). The penalty is 500 X $5,000 X .04, or $100,000. We’ll assume that the readmission rate for myocardial infarction and heart failure are less than expected, so the total penalty is $100,000.

Let’s say the hospital works hard to decrease pneumonia readmissions from 25% to 20% and avoids the penalty. As outlined in Table 1, the hospital will lose $100,000 in revenue (admittedly, reducing readmissions to 20% from 25% represents a big jump, but this is for illustration purposes—we haven’t added in lost revenue from reduced readmissions for other conditions). What’s the final cost of avoiding the $100,000 readmission penalty? Lost revenue of $100,000 plus the cost of implementing the readmission reduction program of $170,000=$270,000.

Why Are We Doing This?

I see the value in care transitions and readmissions-reduction programs, such as Project BOOST, first and foremost as a way to improve patient safety; as such, if implemented effectively, they are likely worth the investment. Second, their value lies in the preparation all hospitals and health systems should be undergoing to remain market-competitive and solvent under global payment systems. Because the penalties in the HRRP might come with lost revenues and the costs of program implementation, be clear about your team’s motivation for reducing readmissions. Your CFO will see to it if I don’t.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

The uproar and confusion over readmissions penalties has consumed umpteen hours of senior leaders’ time (especially that of CFOs), not to mention that of front-line nurses, case managers, quality-improvement (QI) coordinators, hospitalists, and others involved in discharge planning and ensuring a safe transition for patients out of the hospital. For many, the math is fuzzy, and for most, the return on investment is even fuzzier. After all, avoided readmissions are lost revenue to those who are running a business known as an acute-care hospital.

Let me start with the conclusion: Eliminating avoidable readmissions is the right thing to do, period. But the financial downside to doing so is probably greater than any upside realized through avoidance of the penalties that began affecting hospital payments on Oct. 1—at least in the fee-for-service world we live in. At some point in the future, when most patients are under a global payment, the math might be clearer, but today, penalties probably won’t offset lost revenue from reduced readmissions added to the cost of paying lots of people to work in meetings (and at the bedside) to devise better care transitions. (Caveat: If your hospital is bursting at the seams with full occupancy, reducing readmissions and replacing them with higher-reimbursing patients, such as those undergoing elective major surgery, likely will be a net financial gain for your hospital.)

Part of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) will reduce total Medicare DRG reimbursement for hospitals beginning in fiscal-year 2013 based on actual 30-day readmission rates for myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure (HF), and pneumonia that are in excess of risk-adjusted expected rates. The reduction is capped at 1% in 2013, 2% in 2014, and 3% in 2015 and beyond. Hospital readmission rates are based on calculated baseline rates using Medicare data from July 1, 2008, to June 30, 2011.

Cost of a Readmissions-Reduction Program

How much does it cost for a hospital to implement a care-transitions program—such as SHM’s Project BOOST—to reduce readmissions? Last year, I interviewed a dozen hospitals that successfully implemented SHM’s formal mentored implementation program. The result? In the first year of the program, hospitals spent about $170,000 on training and staff time devoted to the project.

Lost Revenue

Let’s look at a sample penalty calculation, then examine a scenario sizing up how revenue is lost when a hospital is successful in reducing readmissions. The ACA defines the payments for excess readmissions as:

The number of patients with the applicable condition (HF, MI, or pneumonia) multiplied by the base DRG payment made for those patients multiplied by the percentage of readmissions beyond the expected.

As an example, let’s take a hospital that treats 500 pneumonia patients (# with the applicable condition), has a base DRG payment for pneumonia of $5,000, and a readmission rate that is 4% higher than expected (in this example, the actual rate is 25% and the expected rate is 24%; 1/25=4%). The penalty is 500 X $5,000 X .04, or $100,000. We’ll assume that the readmission rate for myocardial infarction and heart failure are less than expected, so the total penalty is $100,000.

Let’s say the hospital works hard to decrease pneumonia readmissions from 25% to 20% and avoids the penalty. As outlined in Table 1, the hospital will lose $100,000 in revenue (admittedly, reducing readmissions to 20% from 25% represents a big jump, but this is for illustration purposes—we haven’t added in lost revenue from reduced readmissions for other conditions). What’s the final cost of avoiding the $100,000 readmission penalty? Lost revenue of $100,000 plus the cost of implementing the readmission reduction program of $170,000=$270,000.

Why Are We Doing This?

I see the value in care transitions and readmissions-reduction programs, such as Project BOOST, first and foremost as a way to improve patient safety; as such, if implemented effectively, they are likely worth the investment. Second, their value lies in the preparation all hospitals and health systems should be undergoing to remain market-competitive and solvent under global payment systems. Because the penalties in the HRRP might come with lost revenues and the costs of program implementation, be clear about your team’s motivation for reducing readmissions. Your CFO will see to it if I don’t.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Win Whitcomb: Inflexible, Big-Box EHRs Endanger the QI Movement

In “The Lean Startup,” author Eric Ries notes that in its early stages, his gaming company would routinely issue new versions of their software application several times each day. Continuous deployment—the process Ries’ company used—leveraged such Lean principles as reduced batch size and continuous learning based on end-user feedback to achieve rapid improvements in their product.

Ries says companies that learn the quickest about what the customer wants, and can incorporate that information into products more efficiently, stand the greatest chance of succeeding. A software engineer by trade, Ries uses many examples of companies that have succeeded with this approach, none of which are from healthcare.

In stark relief, the chief technology hospitalists interface with daily is the electronic health record (EHR), widely recognized as a system that fails to consider the end-user experience, that is unable to interoperate with other software, and is incapable of using data for quality improvement (QI). The PDSA (“plan, do, study, act”) cycle is the foundation of QI activities and relies on rapidly incorporating observations made by those performing the work to create novel workflows and processes based on learning. EHRs, by digitizing health information, theoretically provide the ideal tool for supporting QI.

The reality is that EHRs have been a colossal disappointment with regard to QI efforts. The space in and around EHR effectively represents “dead zones” for innovation and improvement. Mandl and Kohane note:

EHR companies have followed a business model whereby they control all data, rather than liberating the data for use in innovative applications in clinical care.

Conducting a Google-style search of an EHR database usually requires involvement of a clinician’s information services department and often the specialized knowledge and cooperation of the vendor’s technical teams.

Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, senior vice president of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, recently provided testimony to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology about the challenges current EHRs present to QI efforts and what features EHRs need to incorporate to better serve the needs of patients and clinicians. Dr. Maynard answered a few questions for The Hospitalist:

Q: What is it about current EHRs that make continuous improvement so difficult?

A: EHRs were built for fiscal and administrative purposes, not for quality improvement and safety. The administrative/fiscal roots of today’s IT systems lead to poor availability of clinical, quality, and safety data. In many medical centers and practices, the great majority of information available is months-old administrative data, which does not lend itself to rapid cycle improvement.

Q: Why is the PDSA cycle endangered in most systems?

A: EHRs often do not facilitate rapid-cycle, PDSA-style improvements on a small pilot scale. Most improvement teams get one shot to get the clinical decision support and data-capture tools correct after months of waiting in queue and development time. Any request for revisions and refinements is treated as a failure of the improvement team, and it is often difficult or impossible to pilot new tools in a limited setting.

Q: What features would you like to see in EHRs that would facilitate QI?

A: We need a user-friendly interface for clinicians and for data analysts/reporters. Other industries have common data formats to allow for sharing of information across disparate systems. We need the same capability for clinical information in healthcare. Also, a change in architecture of EHRs and other health IT tools that allows for not just interoperability but substitutable options is required. In the more “app”-like environment, innovation and flexibility would be the rule. An underlying architecture could have different plug-and-play modules for different functions. Some companies are overcoming the current barriers to provide wonderful, easy-to-generate and useful reports, but most are stymied by proprietary systems.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

In “The Lean Startup,” author Eric Ries notes that in its early stages, his gaming company would routinely issue new versions of their software application several times each day. Continuous deployment—the process Ries’ company used—leveraged such Lean principles as reduced batch size and continuous learning based on end-user feedback to achieve rapid improvements in their product.

Ries says companies that learn the quickest about what the customer wants, and can incorporate that information into products more efficiently, stand the greatest chance of succeeding. A software engineer by trade, Ries uses many examples of companies that have succeeded with this approach, none of which are from healthcare.

In stark relief, the chief technology hospitalists interface with daily is the electronic health record (EHR), widely recognized as a system that fails to consider the end-user experience, that is unable to interoperate with other software, and is incapable of using data for quality improvement (QI). The PDSA (“plan, do, study, act”) cycle is the foundation of QI activities and relies on rapidly incorporating observations made by those performing the work to create novel workflows and processes based on learning. EHRs, by digitizing health information, theoretically provide the ideal tool for supporting QI.

The reality is that EHRs have been a colossal disappointment with regard to QI efforts. The space in and around EHR effectively represents “dead zones” for innovation and improvement. Mandl and Kohane note:

EHR companies have followed a business model whereby they control all data, rather than liberating the data for use in innovative applications in clinical care.

Conducting a Google-style search of an EHR database usually requires involvement of a clinician’s information services department and often the specialized knowledge and cooperation of the vendor’s technical teams.

Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, senior vice president of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, recently provided testimony to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology about the challenges current EHRs present to QI efforts and what features EHRs need to incorporate to better serve the needs of patients and clinicians. Dr. Maynard answered a few questions for The Hospitalist:

Q: What is it about current EHRs that make continuous improvement so difficult?

A: EHRs were built for fiscal and administrative purposes, not for quality improvement and safety. The administrative/fiscal roots of today’s IT systems lead to poor availability of clinical, quality, and safety data. In many medical centers and practices, the great majority of information available is months-old administrative data, which does not lend itself to rapid cycle improvement.

Q: Why is the PDSA cycle endangered in most systems?

A: EHRs often do not facilitate rapid-cycle, PDSA-style improvements on a small pilot scale. Most improvement teams get one shot to get the clinical decision support and data-capture tools correct after months of waiting in queue and development time. Any request for revisions and refinements is treated as a failure of the improvement team, and it is often difficult or impossible to pilot new tools in a limited setting.

Q: What features would you like to see in EHRs that would facilitate QI?

A: We need a user-friendly interface for clinicians and for data analysts/reporters. Other industries have common data formats to allow for sharing of information across disparate systems. We need the same capability for clinical information in healthcare. Also, a change in architecture of EHRs and other health IT tools that allows for not just interoperability but substitutable options is required. In the more “app”-like environment, innovation and flexibility would be the rule. An underlying architecture could have different plug-and-play modules for different functions. Some companies are overcoming the current barriers to provide wonderful, easy-to-generate and useful reports, but most are stymied by proprietary systems.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

In “The Lean Startup,” author Eric Ries notes that in its early stages, his gaming company would routinely issue new versions of their software application several times each day. Continuous deployment—the process Ries’ company used—leveraged such Lean principles as reduced batch size and continuous learning based on end-user feedback to achieve rapid improvements in their product.

Ries says companies that learn the quickest about what the customer wants, and can incorporate that information into products more efficiently, stand the greatest chance of succeeding. A software engineer by trade, Ries uses many examples of companies that have succeeded with this approach, none of which are from healthcare.

In stark relief, the chief technology hospitalists interface with daily is the electronic health record (EHR), widely recognized as a system that fails to consider the end-user experience, that is unable to interoperate with other software, and is incapable of using data for quality improvement (QI). The PDSA (“plan, do, study, act”) cycle is the foundation of QI activities and relies on rapidly incorporating observations made by those performing the work to create novel workflows and processes based on learning. EHRs, by digitizing health information, theoretically provide the ideal tool for supporting QI.

The reality is that EHRs have been a colossal disappointment with regard to QI efforts. The space in and around EHR effectively represents “dead zones” for innovation and improvement. Mandl and Kohane note:

EHR companies have followed a business model whereby they control all data, rather than liberating the data for use in innovative applications in clinical care.

Conducting a Google-style search of an EHR database usually requires involvement of a clinician’s information services department and often the specialized knowledge and cooperation of the vendor’s technical teams.

Greg Maynard, MD, MSc, SFHM, senior vice president of SHM’s Center for Hospital Innovation and Improvement, recently provided testimony to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology about the challenges current EHRs present to QI efforts and what features EHRs need to incorporate to better serve the needs of patients and clinicians. Dr. Maynard answered a few questions for The Hospitalist:

Q: What is it about current EHRs that make continuous improvement so difficult?

A: EHRs were built for fiscal and administrative purposes, not for quality improvement and safety. The administrative/fiscal roots of today’s IT systems lead to poor availability of clinical, quality, and safety data. In many medical centers and practices, the great majority of information available is months-old administrative data, which does not lend itself to rapid cycle improvement.

Q: Why is the PDSA cycle endangered in most systems?

A: EHRs often do not facilitate rapid-cycle, PDSA-style improvements on a small pilot scale. Most improvement teams get one shot to get the clinical decision support and data-capture tools correct after months of waiting in queue and development time. Any request for revisions and refinements is treated as a failure of the improvement team, and it is often difficult or impossible to pilot new tools in a limited setting.

Q: What features would you like to see in EHRs that would facilitate QI?

A: We need a user-friendly interface for clinicians and for data analysts/reporters. Other industries have common data formats to allow for sharing of information across disparate systems. We need the same capability for clinical information in healthcare. Also, a change in architecture of EHRs and other health IT tools that allows for not just interoperability but substitutable options is required. In the more “app”-like environment, innovation and flexibility would be the rule. An underlying architecture could have different plug-and-play modules for different functions. Some companies are overcoming the current barriers to provide wonderful, easy-to-generate and useful reports, but most are stymied by proprietary systems.

Reference

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Win Whitcomb: Spotlight on Medical Necessity

EDITOR’S NOTE: An incorrect version of Win Whitcomb’s “On the Horizon” column was published in the July issue of The Hospitalist. We deeply regret the error. The correct version of Dr. Whitcomb’s column appears this month, with proper attribution given to hospitalist Brad Flansbaum, DO, SFHM, who contributed to the column.

Assigning the appropriate status to patients (“inpatient” or “observation”) has emerged as a front-and-center issue for hospitalists. Also known as “medical necessity,” many HM groups have been called upon to help solve the “status” problem for their institutions. With nearly 1 in 5 hospitalized patients on observation status in U.S. hospitals, appropriately assigning status is now a dominant, system-level challenge for hospitalists.

This month, we asked two experts to shed light on the nature of this beast, with a focus on the impact on the patient. Brad Flansbaum, DO, SFHM, hospitalist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, and Patrick Conway, MD, FAAP, MSC, SFHM, chief medical officer at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), were kind enough to participate in the interview. We start with Dr. Flansbaum.

Dr. Whitcomb: It appears that patients are caught in the middle of the observation status challenge, at least as it relates to footing the bill. Explain the patient perspective of being unwittingly placed on observation status.

Dr. Flansbaum: Recall your last credit card statement. On it is the hotel charge from your last out-of-town CME excursion. Below the total charge, which you were expecting, is a separate line item for a $75 “recreational fee.” You call the hotel, and they inform you that, because you used the hotel gym and pool—accessed with your room key, they levied the fee. No signs, alerts, or postings denoted the policy, so you expected inclusive use of the facilities as a price of your visit. Capture the emotion of the moment, when you see that bill, feel your heart race, and think to yourself, “Get me the manager!”

WW: Why has assigning appropriate status captured the attention of hospitals?

BF: Out of vigilance for penalties and fraud from recovery audit contractor (RAC) investigations, as well attentiveness to unnecessary readmissions, hospitals increasingly are categorizing patients under observation, rather than inpatient, status to avoid conflict with regulators. Beneficiaries are in the crosshairs because of this designation change, and much in the same way of our hotel charge, our patients experience sticker shock when they receive their bill. It is leading to confusion among providers and consternation within the Medicare recipient community.

WW: Why is there so much confusion around appropriate patient status?

BF: The dilemma stems from Medicare payment, and the key distinction between inpatient coverage (Part A) and outpatient coverage, including pharmaceuticals (Parts B and D). When a patient receives their discharge notification—without an “official” inpatient designation, sometimes staying greater than 24 to 48 hours in the ED or in a specially defined observation unit, beneficiary charges are different. This could result in discrete—and sometimes jolting—enrollee copayments and deductibles for drugs and services.

WW: I’ve heard observation status is having a big, adverse impact on patients who go to skilled nursing facilities. Why?

BF: If a patient requires a skilled nursing facility stay (the “three-day stay” inpatient requirement), Medicare will not pay because the patient never registered “official” hospital time. Patients and caregivers are not prepared for the unexpected bills, and consequently, tempers are rising. The rules for Medicare Advantage enrollees (Part C—commercial payers receive a fixed sum from CMS, and oversee parts A, B, and D for an individual beneficiary), which comprise 25% of the program, differ from conventional Medicare. However, commercial plans often shadow traditional, fee-for-service in their policies and, consequently, no exemplar of success in this realm exits.

WW: Why is the number of patients on observation status growing?

BF: Hospitals have significantly increased both the number of their observation stays, as well as their hourly lengths (>48 hours). Because the definition of “observation status” is vague, and even the one- to two-day window is inflating, hospitals and hospitalists often are navigating without a compass. Again, fear of fraud and penalty places hospitals and, indirectly, hospitalists—who often make judgments on admission grade—in a precarious position.

The responsibility of hospitals to notify beneficiaries of their status hinges on this murky determination milieu, which may change in real time during the stay, and makes for an unsatisfactory standard. Understandably, CMS is attempting to rectify this quandary, taking into account a hospital’s need to clarify its billing and designation practices, as well as the beneficiaries’ desire to obtain clear guidance on their responsibilities both during and after the stay. Hospitalists, of course, want direction on coding, along with an understanding of the impact their decisions will have on patients and subspecialty colleagues.

Let’s now bring in Dr. Conway, a pediatric hospitalist. I thank Dr. Flansbaum, who formulated the following questions.

BF/WW: Is it tenable to keep the current system in place? Would it help to require payors and providers to inform beneficiaries of inpatient versus observation status at time zero in a more rigorous, yet to-be-determined manner?

Dr. Conway: Current regulations only require CMS to inform beneficiaries when they are admitted as an inpatient and not when they are an outpatient receiving observation services. There are important implications for beneficiary coverage post-hospital stay, coverage of self-administered drugs, and beneficiary coinsurance from this distinction. As a hospitalist, I think it is best to inform the patient of their status, especially if it has the potential to impact beneficiary liability, including coverage of post-acute care. CMS prepared a pamphlet in 2009, “Are You a Hospital Inpatient or Outpatient? If You Have Medicare, Ask,” to educate beneficiaries on this issue. (Download a PDF of the pamphlet at www.medicare.gov/Publications/Pubs/pdf/11435.pdf.)

BF/WW: Due to the nature of how hospital care is changing, are admission decisions potentially becoming too conflicted an endeavor for inpatient caregivers?

PC: We want admission decisions to be based on clinical considerations. The decision to admit a patient should be based on the clinical judgment of the primary-care, emergency medicine, and/or HM clinician.

BF/WW: Before the U.S. healthcare system matures to a more full-out, integrated model with internalized risk, can you envision any near-term code changes that might simplify the difficulties all parties are facing, in a budget-neutral fashion?

PC: CMS is currently investigating options to clarify when it is appropriate to admit the patient as an inpatient versus keeping the patient as an outpatient receiving observation services. We understand that this issue is of concern to hospitals, hospitalists, and patients, and we are considering carefully how to simplify the rules in a way that best meets the needs of patients and providers without increasing costs to the system.

With growing attention to observation status coming from patients and provider groups (the AMA is requesting that CMS revise its coverage rules), we will no doubt be hearing more about this going forward.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

EDITOR’S NOTE: An incorrect version of Win Whitcomb’s “On the Horizon” column was published in the July issue of The Hospitalist. We deeply regret the error. The correct version of Dr. Whitcomb’s column appears this month, with proper attribution given to hospitalist Brad Flansbaum, DO, SFHM, who contributed to the column.

Assigning the appropriate status to patients (“inpatient” or “observation”) has emerged as a front-and-center issue for hospitalists. Also known as “medical necessity,” many HM groups have been called upon to help solve the “status” problem for their institutions. With nearly 1 in 5 hospitalized patients on observation status in U.S. hospitals, appropriately assigning status is now a dominant, system-level challenge for hospitalists.

This month, we asked two experts to shed light on the nature of this beast, with a focus on the impact on the patient. Brad Flansbaum, DO, SFHM, hospitalist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, and Patrick Conway, MD, FAAP, MSC, SFHM, chief medical officer at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), were kind enough to participate in the interview. We start with Dr. Flansbaum.

Dr. Whitcomb: It appears that patients are caught in the middle of the observation status challenge, at least as it relates to footing the bill. Explain the patient perspective of being unwittingly placed on observation status.

Dr. Flansbaum: Recall your last credit card statement. On it is the hotel charge from your last out-of-town CME excursion. Below the total charge, which you were expecting, is a separate line item for a $75 “recreational fee.” You call the hotel, and they inform you that, because you used the hotel gym and pool—accessed with your room key, they levied the fee. No signs, alerts, or postings denoted the policy, so you expected inclusive use of the facilities as a price of your visit. Capture the emotion of the moment, when you see that bill, feel your heart race, and think to yourself, “Get me the manager!”

WW: Why has assigning appropriate status captured the attention of hospitals?

BF: Out of vigilance for penalties and fraud from recovery audit contractor (RAC) investigations, as well attentiveness to unnecessary readmissions, hospitals increasingly are categorizing patients under observation, rather than inpatient, status to avoid conflict with regulators. Beneficiaries are in the crosshairs because of this designation change, and much in the same way of our hotel charge, our patients experience sticker shock when they receive their bill. It is leading to confusion among providers and consternation within the Medicare recipient community.

WW: Why is there so much confusion around appropriate patient status?

BF: The dilemma stems from Medicare payment, and the key distinction between inpatient coverage (Part A) and outpatient coverage, including pharmaceuticals (Parts B and D). When a patient receives their discharge notification—without an “official” inpatient designation, sometimes staying greater than 24 to 48 hours in the ED or in a specially defined observation unit, beneficiary charges are different. This could result in discrete—and sometimes jolting—enrollee copayments and deductibles for drugs and services.

WW: I’ve heard observation status is having a big, adverse impact on patients who go to skilled nursing facilities. Why?

BF: If a patient requires a skilled nursing facility stay (the “three-day stay” inpatient requirement), Medicare will not pay because the patient never registered “official” hospital time. Patients and caregivers are not prepared for the unexpected bills, and consequently, tempers are rising. The rules for Medicare Advantage enrollees (Part C—commercial payers receive a fixed sum from CMS, and oversee parts A, B, and D for an individual beneficiary), which comprise 25% of the program, differ from conventional Medicare. However, commercial plans often shadow traditional, fee-for-service in their policies and, consequently, no exemplar of success in this realm exits.

WW: Why is the number of patients on observation status growing?

BF: Hospitals have significantly increased both the number of their observation stays, as well as their hourly lengths (>48 hours). Because the definition of “observation status” is vague, and even the one- to two-day window is inflating, hospitals and hospitalists often are navigating without a compass. Again, fear of fraud and penalty places hospitals and, indirectly, hospitalists—who often make judgments on admission grade—in a precarious position.

The responsibility of hospitals to notify beneficiaries of their status hinges on this murky determination milieu, which may change in real time during the stay, and makes for an unsatisfactory standard. Understandably, CMS is attempting to rectify this quandary, taking into account a hospital’s need to clarify its billing and designation practices, as well as the beneficiaries’ desire to obtain clear guidance on their responsibilities both during and after the stay. Hospitalists, of course, want direction on coding, along with an understanding of the impact their decisions will have on patients and subspecialty colleagues.

Let’s now bring in Dr. Conway, a pediatric hospitalist. I thank Dr. Flansbaum, who formulated the following questions.

BF/WW: Is it tenable to keep the current system in place? Would it help to require payors and providers to inform beneficiaries of inpatient versus observation status at time zero in a more rigorous, yet to-be-determined manner?

Dr. Conway: Current regulations only require CMS to inform beneficiaries when they are admitted as an inpatient and not when they are an outpatient receiving observation services. There are important implications for beneficiary coverage post-hospital stay, coverage of self-administered drugs, and beneficiary coinsurance from this distinction. As a hospitalist, I think it is best to inform the patient of their status, especially if it has the potential to impact beneficiary liability, including coverage of post-acute care. CMS prepared a pamphlet in 2009, “Are You a Hospital Inpatient or Outpatient? If You Have Medicare, Ask,” to educate beneficiaries on this issue. (Download a PDF of the pamphlet at www.medicare.gov/Publications/Pubs/pdf/11435.pdf.)

BF/WW: Due to the nature of how hospital care is changing, are admission decisions potentially becoming too conflicted an endeavor for inpatient caregivers?

PC: We want admission decisions to be based on clinical considerations. The decision to admit a patient should be based on the clinical judgment of the primary-care, emergency medicine, and/or HM clinician.

BF/WW: Before the U.S. healthcare system matures to a more full-out, integrated model with internalized risk, can you envision any near-term code changes that might simplify the difficulties all parties are facing, in a budget-neutral fashion?

PC: CMS is currently investigating options to clarify when it is appropriate to admit the patient as an inpatient versus keeping the patient as an outpatient receiving observation services. We understand that this issue is of concern to hospitals, hospitalists, and patients, and we are considering carefully how to simplify the rules in a way that best meets the needs of patients and providers without increasing costs to the system.

With growing attention to observation status coming from patients and provider groups (the AMA is requesting that CMS revise its coverage rules), we will no doubt be hearing more about this going forward.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

EDITOR’S NOTE: An incorrect version of Win Whitcomb’s “On the Horizon” column was published in the July issue of The Hospitalist. We deeply regret the error. The correct version of Dr. Whitcomb’s column appears this month, with proper attribution given to hospitalist Brad Flansbaum, DO, SFHM, who contributed to the column.

Assigning the appropriate status to patients (“inpatient” or “observation”) has emerged as a front-and-center issue for hospitalists. Also known as “medical necessity,” many HM groups have been called upon to help solve the “status” problem for their institutions. With nearly 1 in 5 hospitalized patients on observation status in U.S. hospitals, appropriately assigning status is now a dominant, system-level challenge for hospitalists.

This month, we asked two experts to shed light on the nature of this beast, with a focus on the impact on the patient. Brad Flansbaum, DO, SFHM, hospitalist at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, and Patrick Conway, MD, FAAP, MSC, SFHM, chief medical officer at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), were kind enough to participate in the interview. We start with Dr. Flansbaum.

Dr. Whitcomb: It appears that patients are caught in the middle of the observation status challenge, at least as it relates to footing the bill. Explain the patient perspective of being unwittingly placed on observation status.

Dr. Flansbaum: Recall your last credit card statement. On it is the hotel charge from your last out-of-town CME excursion. Below the total charge, which you were expecting, is a separate line item for a $75 “recreational fee.” You call the hotel, and they inform you that, because you used the hotel gym and pool—accessed with your room key, they levied the fee. No signs, alerts, or postings denoted the policy, so you expected inclusive use of the facilities as a price of your visit. Capture the emotion of the moment, when you see that bill, feel your heart race, and think to yourself, “Get me the manager!”

WW: Why has assigning appropriate status captured the attention of hospitals?

BF: Out of vigilance for penalties and fraud from recovery audit contractor (RAC) investigations, as well attentiveness to unnecessary readmissions, hospitals increasingly are categorizing patients under observation, rather than inpatient, status to avoid conflict with regulators. Beneficiaries are in the crosshairs because of this designation change, and much in the same way of our hotel charge, our patients experience sticker shock when they receive their bill. It is leading to confusion among providers and consternation within the Medicare recipient community.

WW: Why is there so much confusion around appropriate patient status?

BF: The dilemma stems from Medicare payment, and the key distinction between inpatient coverage (Part A) and outpatient coverage, including pharmaceuticals (Parts B and D). When a patient receives their discharge notification—without an “official” inpatient designation, sometimes staying greater than 24 to 48 hours in the ED or in a specially defined observation unit, beneficiary charges are different. This could result in discrete—and sometimes jolting—enrollee copayments and deductibles for drugs and services.

WW: I’ve heard observation status is having a big, adverse impact on patients who go to skilled nursing facilities. Why?

BF: If a patient requires a skilled nursing facility stay (the “three-day stay” inpatient requirement), Medicare will not pay because the patient never registered “official” hospital time. Patients and caregivers are not prepared for the unexpected bills, and consequently, tempers are rising. The rules for Medicare Advantage enrollees (Part C—commercial payers receive a fixed sum from CMS, and oversee parts A, B, and D for an individual beneficiary), which comprise 25% of the program, differ from conventional Medicare. However, commercial plans often shadow traditional, fee-for-service in their policies and, consequently, no exemplar of success in this realm exits.

WW: Why is the number of patients on observation status growing?

BF: Hospitals have significantly increased both the number of their observation stays, as well as their hourly lengths (>48 hours). Because the definition of “observation status” is vague, and even the one- to two-day window is inflating, hospitals and hospitalists often are navigating without a compass. Again, fear of fraud and penalty places hospitals and, indirectly, hospitalists—who often make judgments on admission grade—in a precarious position.

The responsibility of hospitals to notify beneficiaries of their status hinges on this murky determination milieu, which may change in real time during the stay, and makes for an unsatisfactory standard. Understandably, CMS is attempting to rectify this quandary, taking into account a hospital’s need to clarify its billing and designation practices, as well as the beneficiaries’ desire to obtain clear guidance on their responsibilities both during and after the stay. Hospitalists, of course, want direction on coding, along with an understanding of the impact their decisions will have on patients and subspecialty colleagues.

Let’s now bring in Dr. Conway, a pediatric hospitalist. I thank Dr. Flansbaum, who formulated the following questions.

BF/WW: Is it tenable to keep the current system in place? Would it help to require payors and providers to inform beneficiaries of inpatient versus observation status at time zero in a more rigorous, yet to-be-determined manner?

Dr. Conway: Current regulations only require CMS to inform beneficiaries when they are admitted as an inpatient and not when they are an outpatient receiving observation services. There are important implications for beneficiary coverage post-hospital stay, coverage of self-administered drugs, and beneficiary coinsurance from this distinction. As a hospitalist, I think it is best to inform the patient of their status, especially if it has the potential to impact beneficiary liability, including coverage of post-acute care. CMS prepared a pamphlet in 2009, “Are You a Hospital Inpatient or Outpatient? If You Have Medicare, Ask,” to educate beneficiaries on this issue. (Download a PDF of the pamphlet at www.medicare.gov/Publications/Pubs/pdf/11435.pdf.)

BF/WW: Due to the nature of how hospital care is changing, are admission decisions potentially becoming too conflicted an endeavor for inpatient caregivers?

PC: We want admission decisions to be based on clinical considerations. The decision to admit a patient should be based on the clinical judgment of the primary-care, emergency medicine, and/or HM clinician.

BF/WW: Before the U.S. healthcare system matures to a more full-out, integrated model with internalized risk, can you envision any near-term code changes that might simplify the difficulties all parties are facing, in a budget-neutral fashion?

PC: CMS is currently investigating options to clarify when it is appropriate to admit the patient as an inpatient versus keeping the patient as an outpatient receiving observation services. We understand that this issue is of concern to hospitals, hospitalists, and patients, and we are considering carefully how to simplify the rules in a way that best meets the needs of patients and providers without increasing costs to the system.

With growing attention to observation status coming from patients and provider groups (the AMA is requesting that CMS revise its coverage rules), we will no doubt be hearing more about this going forward.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Win Whitcomb: Staying ... and Paying

Take a minute to recall your last credit-card statement. On it, say, is the hotel charge from your last out-of-town CME excursion. Below the total charge you were expecting is a separate line-item charge of $75 for a “recreational fee.” Puzzled, you call the hotel. They inform you that because you used the gym and pool—accessed with your room key—they levied the fee. No signs, alerts, or postings to denote such a policy, you innocently expected inclusive use of the facilities in the price of your visit.

Capture the emotion of that moment. It is likely your heart will race and you will think to yourself, “Get me the manager!”

Out of vigilance for penalties and fraud from recovery audit contractor (RAC) investigations, as well attentiveness to unnecessary readmissions, hospitals increasingly are categorizing Medicare patients under observation, rather than inpatient, status. This is to avoid conflict with regulators. Beneficiaries are in the crosshairs because of this designation change and, much in the same way as with our hotel charge, they also experience sticker shock when they get their bills. It is leading to confusion among providers, and consternation within the Medicare recipient community.

Why is this occurring? The dilemma stems from Medicare payments and the key distinction between inpatient coverage (Part A) and outpatient coverage (Parts B and D). When a patient receives their discharge notification—without an “official” inpatient designation—sometimes staying greater than 24 to 48 hours in the ED or in a specially defined observation unit can mean that beneficiary charges are different. This could result in discrete and sometimes jolting copayments and deductibles for drugs and services.

Worse, if beneficiaries require a skilled nursing facility stay (the “three-day stay” inpatient requirement), Medicare will not pay because they never registered “official” hospital time. Patients and caregivers are not prepared for the unexpected bills, and, consequently, tempers are rising.

The rules for Medicare Advantage enrollees, who make up 25% of the program, differ from conventional Medicare. However, commercial plans often shadow traditional fee-for-service in their policies, and, consequently, no exemplar of success in this realm exits.

Hospitals have increased both the number of their observation stays, as well as their hourly lengths (>48 hours). Because the definition of “observation status” is vague, and even the one- to two-day window is inflating, hospitals and hospitalists are often left to navigate without a compass. Again, fear of fraud and penalties places hospitals—and, indirectly, hospitalists, who often make judgments on admission grade—in a precarious position.

The responsibility of hospitals to notify beneficiaries of their status hinges on this murky determination milieu, which might change in real time during the stay and makes for an unsatisfactory standard. Understandably, CMS is attempting to rectify this quandary, taking into account a hospital’s need to clarify its billing and designation practices as well as beneficiaries’ desire to obtain clear guidance on their responsibilities both during and after a stay.

Hospitalists, of course, want direction on coding and an understanding of the impact their decisions will have on patients and subspecialty colleagues. To that end, Patrick Conway, MD, SFHM, chief medical officer for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS), offers some enlightenment on this matter:

Q: Is it tenable to keep the current system in place? However, as a fix, require payors and providers to inform beneficiaries of inpatient versus observation status at time zero in a more rigorous, yet-to-be determined manner?

A: Current regulations only require CMS to inform beneficiaries when they are admitted as an inpatient and not when they are an outpatient receiving observation services. There are important implications for coverage for beneficiaries post-hospital stay, coverage of self-administered drugs, and beneficiary coinsurance from this distinction. As a hospitalist, I think it is best to inform the patient of their status, especially if it has the potential to impact beneficiary liability, including coverage of post-acute care. CMS prepared a pamphlet in 2009, “Are You a Hospital Inpatient or Outpatient? If You Have Medicare, Ask!” to educate beneficiaries on this issue. The pamphlet can found at http://www.medicare.gov/Publications/Pubs/pdf/11435.pdf.

Q: Due to the nature of how hospital care is changing, are admission decisions potentially becoming too conflicted an endeavor for inpatient caregivers?

A: We want admission decisions to be based on clinical considerations. The decision to admit a patient should be based on the clinical judgment of the primary care, emergency medicine, and/or hospital medicine clinician.

Q: Before the U.S. healthcare system matures to a more integrated model with internalized risk, can you envision any near-term code changes that might simplify the difficulties all parties are facing, in a budget-neutral fashion?

A: CMS is currently investigating options to clarify when it is appropriate to admit the patient as an inpatient versus keeping the patient as an outpatient receiving observation services. We understand that this issue is of concern to hospitals, hospitalists, and patients, and we are considering carefully how to simplify the rules in a way that best meets the needs of patients and providers without increasing costs to the system.

I expect we will hear more from Medicare in the near-term on this matter. Stay tuned.

For more about the patient’s perspective on this issue, please see Brad’s blog: www.hospitalmedicine.org/pmblog.

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at [email protected].

Take a minute to recall your last credit-card statement. On it, say, is the hotel charge from your last out-of-town CME excursion. Below the total charge you were expecting is a separate line-item charge of $75 for a “recreational fee.” Puzzled, you call the hotel. They inform you that because you used the gym and pool—accessed with your room key—they levied the fee. No signs, alerts, or postings to denote such a policy, you innocently expected inclusive use of the facilities in the price of your visit.

Capture the emotion of that moment. It is likely your heart will race and you will think to yourself, “Get me the manager!”

Out of vigilance for penalties and fraud from recovery audit contractor (RAC) investigations, as well attentiveness to unnecessary readmissions, hospitals increasingly are categorizing Medicare patients under observation, rather than inpatient, status. This is to avoid conflict with regulators. Beneficiaries are in the crosshairs because of this designation change and, much in the same way as with our hotel charge, they also experience sticker shock when they get their bills. It is leading to confusion among providers, and consternation within the Medicare recipient community.

Why is this occurring? The dilemma stems from Medicare payments and the key distinction between inpatient coverage (Part A) and outpatient coverage (Parts B and D). When a patient receives their discharge notification—without an “official” inpatient designation—sometimes staying greater than 24 to 48 hours in the ED or in a specially defined observation unit can mean that beneficiary charges are different. This could result in discrete and sometimes jolting copayments and deductibles for drugs and services.

Worse, if beneficiaries require a skilled nursing facility stay (the “three-day stay” inpatient requirement), Medicare will not pay because they never registered “official” hospital time. Patients and caregivers are not prepared for the unexpected bills, and, consequently, tempers are rising.

The rules for Medicare Advantage enrollees, who make up 25% of the program, differ from conventional Medicare. However, commercial plans often shadow traditional fee-for-service in their policies, and, consequently, no exemplar of success in this realm exits.

Hospitals have increased both the number of their observation stays, as well as their hourly lengths (>48 hours). Because the definition of “observation status” is vague, and even the one- to two-day window is inflating, hospitals and hospitalists are often left to navigate without a compass. Again, fear of fraud and penalties places hospitals—and, indirectly, hospitalists, who often make judgments on admission grade—in a precarious position.

The responsibility of hospitals to notify beneficiaries of their status hinges on this murky determination milieu, which might change in real time during the stay and makes for an unsatisfactory standard. Understandably, CMS is attempting to rectify this quandary, taking into account a hospital’s need to clarify its billing and designation practices as well as beneficiaries’ desire to obtain clear guidance on their responsibilities both during and after a stay.

Hospitalists, of course, want direction on coding and an understanding of the impact their decisions will have on patients and subspecialty colleagues. To that end, Patrick Conway, MD, SFHM, chief medical officer for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid (CMS), offers some enlightenment on this matter:

Q: Is it tenable to keep the current system in place? However, as a fix, require payors and providers to inform beneficiaries of inpatient versus observation status at time zero in a more rigorous, yet-to-be determined manner?

A: Current regulations only require CMS to inform beneficiaries when they are admitted as an inpatient and not when they are an outpatient receiving observation services. There are important implications for coverage for beneficiaries post-hospital stay, coverage of self-administered drugs, and beneficiary coinsurance from this distinction. As a hospitalist, I think it is best to inform the patient of their status, especially if it has the potential to impact beneficiary liability, including coverage of post-acute care. CMS prepared a pamphlet in 2009, “Are You a Hospital Inpatient or Outpatient? If You Have Medicare, Ask!” to educate beneficiaries on this issue. The pamphlet can found at http://www.medicare.gov/Publications/Pubs/pdf/11435.pdf.

Q: Due to the nature of how hospital care is changing, are admission decisions potentially becoming too conflicted an endeavor for inpatient caregivers?

A: We want admission decisions to be based on clinical considerations. The decision to admit a patient should be based on the clinical judgment of the primary care, emergency medicine, and/or hospital medicine clinician.