User login

Predictors of County-Level Home Modification Use Across the US

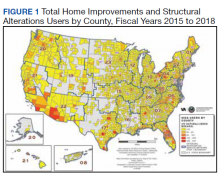

This article is part of a series of articles on the Home Improvements and Structural Alterations program (HISA), a home modification (HM) program within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). HISA is a benefit awarded to veterans with disabilities (VWDs) and is instrumental in affording physical accessibility and structural alterations to veterans’ homes.1 The overarching goals of this project are to describe and understand HISA use by VWDs. Previous work has shown geographical variation in the number of HISA prescriptions across counties in the US (Figure 1).1 The current work seeks to describe and predict the county-level rates of HISA use. Information about what predicts HISA utilization at the county level is important because it enhances understanding of program utilization at a national level. The long-term goal of the series is to provide knowledge about HM services within VHA to improve community-based independent living of VWDs by increasing awareness and utilization of HM services.

Background

A health care professional (HCP) approves a HM support award by evaluating the practicality of the support to improve the built environment of a given veteran’s disability.1,2 Previously we detailed some of the preliminary research into the HISA program, including HISA user demographic and clinical characteristics, types of HMs received, user suggestions for improvement, and geospatial analysis of HISA prescriptions concentration.1-4

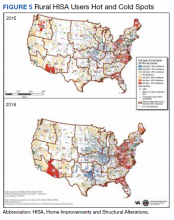

The geospatial analyses of HISA prescriptions revealed clusters of high numbers of HISA users (hot spots) and low numbers of HISA users (cold spots), indicating that HISA is either not prescribed or uniformly used across the US. The previous research prompted investigation into county-level variables that may impact HISA utilization rates. This inquiry focuses on county characteristics associated with HISA use rates, such as measures of clinical care and quality of care (eg, access to health services variables, lack of insurance, preventable hospital stays), physical environment, and sociodemographic characteristics. Clinical care and quality of care measures promote the interaction with HCPs. Moreover, access to health care is an important indicator of health outcomes.5,6 An individual’s capacity to access health services, such as a HM program, greatly impacts well-being, safety, independence, and health.2,4 Well-being, safety, independence, and health become compromised if individuals cannot access care, if needed care is lacking in their area, if HCPs are not available, or are unwilling to provide care due to lack of insurance coverage.7-12 In locations where health care services are minimal due to lack of specialists or health care facilities, the quality of (or access to) care may be compromised, resulting in preventable conditions becoming problematic.13,14 These conditions may result in unnecessary hospitalizations for conditions that could have been treated during routine care. Financial barriers to care particularly among low-income people and the uninsured have proven detrimental to health.15,16 On the other hand, preventable hospital stays are a quality of care measure (ie, a proxy for poor quality of care). HISA operates within a health care system; thus, it is imperative to include these measures impacting health.

In this study, we sought to identify county-level predictors—in particular, county-level proxies for access to care—that may be associated with county-level HISA use. We define HISA utilization rate as the percentage of a county’s VHA patients who have received a HISA award.

Methods

This study used data from the National Prosthetics Patient Database (NPPD), US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical database inpatient and outpatient datasets, VHA Support Service Center (VSSC) data cubes, and the County Health Rankings database (CHRD). First, the study cohort was identified from NPPD users who have obtained a HISA award from fiscal years (FY) 2015 to 2018. Analysis started with FY 2015 following new regulations (38 CFR § 17) governing the operations of the HISA program.2 The study cohort was matched with records from NPPD and VA inpatient and outpatient datasets to obtain information about the veterans’ demographic characteristics and their HM characteristics and costs. The number of VHA end-of-year (EOY) patients per county was extracted from the VSSC Current Enrollment Cube, which was used in calculation of the county-level HISA utilization rate.17 Finally, zip code–based locational data were used to calculate approximate drive time and distance from the HISA user’s approximate location to the facility where they received their HM prescription. Drive times and drive distances were calculated with Esri ArcGIS Pro (v2.6.3) by placing zip code centroid and VHA facilities on a nationwide road network that contains both road speeds and distances.

Calculations

Patient-level data were aggregated up to county-level variables by calculating the sum, mean, or percent per county. HISA user sample characteristics, including sex, race, rurality (urban, rural), marital status, and Class 1 vs Class 2 disability-related eligibility groups, were aggregated to the county level by calculating percentages of HISA users of the given characteristics out of total HISA users in the county. Disability-related eligibility groups (Class 1 vs Class 2 HISA users) determines the maximum lifetime award dollar amount. Specifically, those with service-connected disabilities or those with a ≥ 50% disability rating (regardless of whether or not their disability is service connected) are classified as Class 1 HISA users and are eligible to receive a maximum lifetime award of $6800. Those with a recorded disability that is not connected to their military service, and who have a disability rating of < 50% are classified as Class 2 HISA users and are eligible to receive a lifetime maximum award of $2000.

The county-level number of HISA users was used as the numerator for calculation of county-level HISA utilization rate. Counties with zero HISA users were excluded. The number of EOY VHA patients per county in FY 2018 was divided by 1000 and used as the denominator in the calculation of county-level HISA utilization rate. Thus, the outcome variable is HISA utilization rate per 1000 VHA patients in FY 2018 (HISA utilization rate).

County-Level Variables

County-level variables were downloaded from the 2020 CHRD.5,6 An explanation of the CHRD model and the factors used in this study are shown in the eAppendix (available at doi: 10.12788/fp.0279).6 County-level aggregated HISA user data and the CHRD data were matched using county Federal Information Processing Standards codes. Access to care measures collected from CHRD included percentages uninsured and ratios of population to primary care physicians, dentists, mental health professionals, and other primary care professionals. Other CHRD measures included those for quality of care (rate of preventable hospital stay) and housing quality (percent of households with high housing costs, percent of households with overcrowding, percent of households with lack of kitchen or plumbing, percent of households with severe housing cost burden, percent of homeownership). Of secondary interest was county population rurality, as previous research findings showed the annual average of HISA users who are from rural areas ranged from 30 to 35%.

Analysis Methods

SAS (v9.4), R (v4.0.2), and RStudio (v1.3.1093) were used for data preparation and analysis.18 Multiple regression analysis was used to predict county-level utilization rate from county-level variables. Sociodemographic characteristics from CHRD and HISA data were included as important control predictors in the regression model, though our focus for this paper are the access to care and housing quality predictors.

Model diagnostics (examination of model residuals, Breusch-Godfrey test, Breusch-Pagan test) revealed significant heteroskedasticity of the model; thus, robust standard errors and associated P values were computed using the R estimatr package (v0.30.2).19 Some predictor variables of interest (eg, ratio of mental health professionals) were removed during the model building process either due to problems of multicollinearity or excessive missingness that would have resulted in listwise deletion.

Results

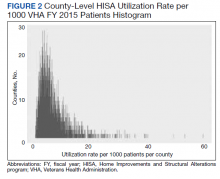

County-level HISA utilization rate per 1000 EOY VHA patients ranged from 0.09 to 59.7%, with a 6.6% mean and 5% median (Figure 2). The data were highly positively skewed. The final model included 33 total predictor variables (Table 1). The final regression model was a significantly better predictor of county-level HISA utilization rate than a null model (F[33-2184], 10.18; P < .001). The adjusted model R2 showed that the overall model accounted for approximately 23% of variance in county-level HISA utilization rate (Table 2).

Among the primary variables of interest, percent uninsured adults and rate of preventable hospital stays emerged as significant predictors of county-level HISA utilization rate. Specifically, county percentage of uninsured adults was negatively related to county-level HISA utilization rate (b = -8.99, P = .005), indicating that the higher the proportion of uninsured adults—with all other predictors held constant—the lower the HISA utilization rate. Percent uninsured adults ranged from 2.7 to 42.4% across counties, with a mean (SD) of 12.7% (5.8%) and 11.4% median.

County rate of preventable hospital stays, however, was significantly and positively related to county-level HISA utilization rate (b = .0004, P = .009), indicating that the higher the rate of preventable hospital stays—with all other predictors held constant—the higher the HISA utilization rate. The direction of this effect is the opposite of the direction of the effect of percent uninsured adults (positive rather than negative), even though both could be considered measures of access to care. The standardized β for these 2 predictors indicate that county rate of preventable hospital stays is a somewhat stronger predictor of county-level HISA utilization rate than is county percent of uninsured adults (β = .11 and β = -.09, respectively). Rate of preventable hospital stays ranged from 683 to 16,802 across counties included in this analysis, with a mean (SD) of 4,796.5 (1659.9) and a 4669 median.

Of secondary interest was county rurality. The county-level percentage of rural residents was significantly and positively related to county-level HISA utilization rate, indicating that the higher the proportion of individuals within county considered rural—all other predictors held constant—the higher the HISA utilization rate. The mean (SD) percentage of rural residents per county was 52.3% (30.2) and 52.7 % median.

Discussion

This study examined whether county-level characteristics, specifically variables for access to care, quality of care, and housing quality, were predictive of a county’s HISA utilization rate. Given that this series of work on the HISA program is (to our knowledge) the first of its kind, and given the exploratory nature of this analysis, we did not have specific predictions for the effects of any one given variable. Nevertheless, some of the results were surprising, and we believe they warrant additional study. In particular, the opposing direction of effects for access to care and quality of care variables were hard to reconcile.

The county percent of uninsured adults (an access to care variable, specifically, a proxy for poor access to care) was negatively associated with county-level HISA utilization rate, whereas the county rate of preventable hospital stays (a quality of care variable, but also potentially an access to care variable, and specifically, proxies for poor quality of care or poor access to care) was positively associated with county-level HISA utilization rate. To describe the relationships more generally, one coefficient in the regression model indicated that the poorer the access to care, the lower the HISA utilization rate (higher percent of uninsured adults predicts lower HISA utilization rate), while another coefficient in the regression model indicated the poorer the quality of and access to care, the higher the HISA utilization rate (higher rate of preventable hospital stays predicts higher HISA utilization rate). Future study is warranted to disentangle and reconcile the various community-level predictors of this service.

Housing quality measures (eg, percent of households with high housing costs, percent of households with overcrowding, percent of households with lack of kitchen or plumbing, percent of households with severe housing cost burden, and percent of homeownership) are important in the consideration of whether a HM will be performed or should be performed. For example, if a person is cost burdened by the amount of expenditure spent in housing there will be little discretionary funds to perform a HM. Individuals who do not own their home may experience complications in obtaining permission from landlords to perform a HM. County-level predictors of housing quality (percent of households with high housing costs, overcrowding, and lack of kitchen or plumbing) were not significantly associated with county-level HISA utilization rate but are also nevertheless relevant to the discussion of home modifications. Of particular interest is the percent of households with lack of kitchen or plumbing variable, which was positively related to county-level HISA utilization rate although not statistically significant. HM elements related to the kitchen (eg, heighten countertop) add to the accessibility of the home allowing for the performing of activities of daily living such as cooking. Between FY 2015 and FY 2018, we discovered 131 prescriptions for kitchen (n = 90) and plumbing (n = 41) HMs, which is a very small proportion of the 30,780 total HMs (there were 24,397 bathroom HMs). The nonsignificant coefficient for this variable may reflect the small number of veterans that obtained these HM.

Limitations

The potentially conflicting direction of effects for a significant access to care variable (percent uninsured adults) and a significant access to care and quality of care variable (preventable hospital stays) are interesting and warrant additional study, but the inability to interpret or explain this apparent inconsistency constitutes a limitation of the current data and analyses presented here. Another limitation is that this analysis uses county-level predictors for what is ultimately an individual-level outcome. It would have been ideal to have both individual- and county-level data to conduct a multilevel analysis; in particular, individual-level data within counties of individuals (both veterans and nonveterans) who did not receive a HISA award (including both those who applied and were denied, and who did not apply) would be highly valuable.

Conclusions

Our continuing research into veterans’ use of HM fills a gap in the literature about the characteristics of HISA users, the impact of county-level variables on the use of HISA, and the geographic distribution and use of HISA within the VHA. While it is important to examine the influence of broader systems on individual outcomes, there could be myriad other factors that are more proximal and more closely related to whether any one individual applies for, let alone receives, a HISA award. Indeed, a low overall adjusted model R2 indicates that there is considerable variability in county-level HISA utilization rate that was not accounted for by the current model; this further speaks to warranted additional study.

More research is needed to understand and account for geographical variation in HISA utilization rate across the US. However, this work serves as an exploratory first step at quantifying and predicting HISA utilization rate at a broad level, with the ultimate goal of increasing access to HMs for veterans with disabilities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 15521 from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Furthermore, the research was supported in part by grant K12 HD055929 from the National Institutes of Health. We want to acknowledge Cheri E. Knecht, Project Coordinator, for her assistance throughout all aspects of our research study and for her thoughtful contributions during the writing of this manuscript.

1. Semeah LM, Ahrentzen S, Jia H, Cowper-Ripley DC, Levy CE, Mann WC. The home improvements and structural alterations benefits program: veterans with disabilities and home accessibility. J Disability Policy Studies. 2017;28(1):43-51. doi:10.1177/1044207317696275

2. Semeah LM, Wang X, Cowper Ripley DC, Lee MJ, Ahonle ZJ, Ganesh SP, et al. Improving health through a home modification service for veterans. In: Fiedler BA, ed. Three Facets of Public Health and Paths to Improvements. Academic Press; 2020:381-416.

3. Semeah LM, Ahrentzen S, Cowper-Ripley DC, Santos-Roman LM, Beamish JO, Farley K. Rental housing needs and barriers from the perspective of veterans with disabilities. Housing Policy Debate. 2019;29(4):542-558. doi:10.1080/10511482.2018.1543203

4. Semeah LM, Ganesh SP, Wang X, et al. Home modification and health services utilization by rural and urban veterans with disabilities. Housing Policy Debate. 2021;31(6):862-874.doi:10.1080/10511482.2020.1858923

5. University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County health rankings model. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/about-us

6. Remington PL, Catlin BB, Gennuso KP. The County Health Rankings: rationale and methods. Popul Health Metr. 2015;13(11). doi:10.1186/s12963-015-0044-2

7. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Health-Care Utilization as a Proxy in Disability Determination. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018.

8. Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, Biswas S. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health. 2015;129(6):611-20. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.001

9. Medicaid and Chip Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Medicaid access in brief: adults’ experiences in obtaining medical care. November 2016. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/access-in-brief-adults-experiences-in-obtaining-medical-care

10. Tolbert J, Orgera, K, Damico A. Key facts about the uninsured population. November 6, 2020. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population

11. Meit M, Knudson A, Gilbert T, et al. The 2014 update of the rural-urban chartbook, 2014. October 2014. Accessed May 13, 2022. http://www.ruralhealthresearch.org

12. National Center for Health Statistics (US). Report No.: 2016-1232. Health, United States, 2015: with special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

13. Broussard DL, Mason KE, Carruth AR, Carton TW. Assessing potentially preventable hospitalizations at the county level: a comparison of measures using Medicare data and state hospital discharge data. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21(6):438-445. doi:10.1089/pop.2017.0141

14. Pezzin LE, Bogner HR, Kurichi JE, et al. Preventable hospitalizations, barriers to care, and disability. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0691 doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010691

15. Davis K, Ballreich J. Equitable access to care: how the United States ranks internationally. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1567-70. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1406707

16. Squires D, Anderson C. U.S. health care from a global perspective: spending, use of services, prices, and health in 13 countries. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2015;15:1-15.

17. VHA Service Support Center. Current enrollment cube (vssc.med.va.gov). Retrieved August 06, 2019. [Data not verified.]

18. Bunn A, Korpela M. R: A language and environment for statistical computing: an introduction to dplR. January 29, 2021. Accessed May 13, 2022. http://r.meteo.uni.wroc.pl/web/packages/dplR/vignettes/intro-dplR.pdf

19. Sheppard BH, Hartwick J, Warshaw PR. The theory of reasoned action: a meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. J Consumer Research. 1988;15(3):325-343. doi:10.1086/209170

This article is part of a series of articles on the Home Improvements and Structural Alterations program (HISA), a home modification (HM) program within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). HISA is a benefit awarded to veterans with disabilities (VWDs) and is instrumental in affording physical accessibility and structural alterations to veterans’ homes.1 The overarching goals of this project are to describe and understand HISA use by VWDs. Previous work has shown geographical variation in the number of HISA prescriptions across counties in the US (Figure 1).1 The current work seeks to describe and predict the county-level rates of HISA use. Information about what predicts HISA utilization at the county level is important because it enhances understanding of program utilization at a national level. The long-term goal of the series is to provide knowledge about HM services within VHA to improve community-based independent living of VWDs by increasing awareness and utilization of HM services.

Background

A health care professional (HCP) approves a HM support award by evaluating the practicality of the support to improve the built environment of a given veteran’s disability.1,2 Previously we detailed some of the preliminary research into the HISA program, including HISA user demographic and clinical characteristics, types of HMs received, user suggestions for improvement, and geospatial analysis of HISA prescriptions concentration.1-4

The geospatial analyses of HISA prescriptions revealed clusters of high numbers of HISA users (hot spots) and low numbers of HISA users (cold spots), indicating that HISA is either not prescribed or uniformly used across the US. The previous research prompted investigation into county-level variables that may impact HISA utilization rates. This inquiry focuses on county characteristics associated with HISA use rates, such as measures of clinical care and quality of care (eg, access to health services variables, lack of insurance, preventable hospital stays), physical environment, and sociodemographic characteristics. Clinical care and quality of care measures promote the interaction with HCPs. Moreover, access to health care is an important indicator of health outcomes.5,6 An individual’s capacity to access health services, such as a HM program, greatly impacts well-being, safety, independence, and health.2,4 Well-being, safety, independence, and health become compromised if individuals cannot access care, if needed care is lacking in their area, if HCPs are not available, or are unwilling to provide care due to lack of insurance coverage.7-12 In locations where health care services are minimal due to lack of specialists or health care facilities, the quality of (or access to) care may be compromised, resulting in preventable conditions becoming problematic.13,14 These conditions may result in unnecessary hospitalizations for conditions that could have been treated during routine care. Financial barriers to care particularly among low-income people and the uninsured have proven detrimental to health.15,16 On the other hand, preventable hospital stays are a quality of care measure (ie, a proxy for poor quality of care). HISA operates within a health care system; thus, it is imperative to include these measures impacting health.

In this study, we sought to identify county-level predictors—in particular, county-level proxies for access to care—that may be associated with county-level HISA use. We define HISA utilization rate as the percentage of a county’s VHA patients who have received a HISA award.

Methods

This study used data from the National Prosthetics Patient Database (NPPD), US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical database inpatient and outpatient datasets, VHA Support Service Center (VSSC) data cubes, and the County Health Rankings database (CHRD). First, the study cohort was identified from NPPD users who have obtained a HISA award from fiscal years (FY) 2015 to 2018. Analysis started with FY 2015 following new regulations (38 CFR § 17) governing the operations of the HISA program.2 The study cohort was matched with records from NPPD and VA inpatient and outpatient datasets to obtain information about the veterans’ demographic characteristics and their HM characteristics and costs. The number of VHA end-of-year (EOY) patients per county was extracted from the VSSC Current Enrollment Cube, which was used in calculation of the county-level HISA utilization rate.17 Finally, zip code–based locational data were used to calculate approximate drive time and distance from the HISA user’s approximate location to the facility where they received their HM prescription. Drive times and drive distances were calculated with Esri ArcGIS Pro (v2.6.3) by placing zip code centroid and VHA facilities on a nationwide road network that contains both road speeds and distances.

Calculations

Patient-level data were aggregated up to county-level variables by calculating the sum, mean, or percent per county. HISA user sample characteristics, including sex, race, rurality (urban, rural), marital status, and Class 1 vs Class 2 disability-related eligibility groups, were aggregated to the county level by calculating percentages of HISA users of the given characteristics out of total HISA users in the county. Disability-related eligibility groups (Class 1 vs Class 2 HISA users) determines the maximum lifetime award dollar amount. Specifically, those with service-connected disabilities or those with a ≥ 50% disability rating (regardless of whether or not their disability is service connected) are classified as Class 1 HISA users and are eligible to receive a maximum lifetime award of $6800. Those with a recorded disability that is not connected to their military service, and who have a disability rating of < 50% are classified as Class 2 HISA users and are eligible to receive a lifetime maximum award of $2000.

The county-level number of HISA users was used as the numerator for calculation of county-level HISA utilization rate. Counties with zero HISA users were excluded. The number of EOY VHA patients per county in FY 2018 was divided by 1000 and used as the denominator in the calculation of county-level HISA utilization rate. Thus, the outcome variable is HISA utilization rate per 1000 VHA patients in FY 2018 (HISA utilization rate).

County-Level Variables

County-level variables were downloaded from the 2020 CHRD.5,6 An explanation of the CHRD model and the factors used in this study are shown in the eAppendix (available at doi: 10.12788/fp.0279).6 County-level aggregated HISA user data and the CHRD data were matched using county Federal Information Processing Standards codes. Access to care measures collected from CHRD included percentages uninsured and ratios of population to primary care physicians, dentists, mental health professionals, and other primary care professionals. Other CHRD measures included those for quality of care (rate of preventable hospital stay) and housing quality (percent of households with high housing costs, percent of households with overcrowding, percent of households with lack of kitchen or plumbing, percent of households with severe housing cost burden, percent of homeownership). Of secondary interest was county population rurality, as previous research findings showed the annual average of HISA users who are from rural areas ranged from 30 to 35%.

Analysis Methods

SAS (v9.4), R (v4.0.2), and RStudio (v1.3.1093) were used for data preparation and analysis.18 Multiple regression analysis was used to predict county-level utilization rate from county-level variables. Sociodemographic characteristics from CHRD and HISA data were included as important control predictors in the regression model, though our focus for this paper are the access to care and housing quality predictors.

Model diagnostics (examination of model residuals, Breusch-Godfrey test, Breusch-Pagan test) revealed significant heteroskedasticity of the model; thus, robust standard errors and associated P values were computed using the R estimatr package (v0.30.2).19 Some predictor variables of interest (eg, ratio of mental health professionals) were removed during the model building process either due to problems of multicollinearity or excessive missingness that would have resulted in listwise deletion.

Results

County-level HISA utilization rate per 1000 EOY VHA patients ranged from 0.09 to 59.7%, with a 6.6% mean and 5% median (Figure 2). The data were highly positively skewed. The final model included 33 total predictor variables (Table 1). The final regression model was a significantly better predictor of county-level HISA utilization rate than a null model (F[33-2184], 10.18; P < .001). The adjusted model R2 showed that the overall model accounted for approximately 23% of variance in county-level HISA utilization rate (Table 2).

Among the primary variables of interest, percent uninsured adults and rate of preventable hospital stays emerged as significant predictors of county-level HISA utilization rate. Specifically, county percentage of uninsured adults was negatively related to county-level HISA utilization rate (b = -8.99, P = .005), indicating that the higher the proportion of uninsured adults—with all other predictors held constant—the lower the HISA utilization rate. Percent uninsured adults ranged from 2.7 to 42.4% across counties, with a mean (SD) of 12.7% (5.8%) and 11.4% median.

County rate of preventable hospital stays, however, was significantly and positively related to county-level HISA utilization rate (b = .0004, P = .009), indicating that the higher the rate of preventable hospital stays—with all other predictors held constant—the higher the HISA utilization rate. The direction of this effect is the opposite of the direction of the effect of percent uninsured adults (positive rather than negative), even though both could be considered measures of access to care. The standardized β for these 2 predictors indicate that county rate of preventable hospital stays is a somewhat stronger predictor of county-level HISA utilization rate than is county percent of uninsured adults (β = .11 and β = -.09, respectively). Rate of preventable hospital stays ranged from 683 to 16,802 across counties included in this analysis, with a mean (SD) of 4,796.5 (1659.9) and a 4669 median.

Of secondary interest was county rurality. The county-level percentage of rural residents was significantly and positively related to county-level HISA utilization rate, indicating that the higher the proportion of individuals within county considered rural—all other predictors held constant—the higher the HISA utilization rate. The mean (SD) percentage of rural residents per county was 52.3% (30.2) and 52.7 % median.

Discussion

This study examined whether county-level characteristics, specifically variables for access to care, quality of care, and housing quality, were predictive of a county’s HISA utilization rate. Given that this series of work on the HISA program is (to our knowledge) the first of its kind, and given the exploratory nature of this analysis, we did not have specific predictions for the effects of any one given variable. Nevertheless, some of the results were surprising, and we believe they warrant additional study. In particular, the opposing direction of effects for access to care and quality of care variables were hard to reconcile.

The county percent of uninsured adults (an access to care variable, specifically, a proxy for poor access to care) was negatively associated with county-level HISA utilization rate, whereas the county rate of preventable hospital stays (a quality of care variable, but also potentially an access to care variable, and specifically, proxies for poor quality of care or poor access to care) was positively associated with county-level HISA utilization rate. To describe the relationships more generally, one coefficient in the regression model indicated that the poorer the access to care, the lower the HISA utilization rate (higher percent of uninsured adults predicts lower HISA utilization rate), while another coefficient in the regression model indicated the poorer the quality of and access to care, the higher the HISA utilization rate (higher rate of preventable hospital stays predicts higher HISA utilization rate). Future study is warranted to disentangle and reconcile the various community-level predictors of this service.

Housing quality measures (eg, percent of households with high housing costs, percent of households with overcrowding, percent of households with lack of kitchen or plumbing, percent of households with severe housing cost burden, and percent of homeownership) are important in the consideration of whether a HM will be performed or should be performed. For example, if a person is cost burdened by the amount of expenditure spent in housing there will be little discretionary funds to perform a HM. Individuals who do not own their home may experience complications in obtaining permission from landlords to perform a HM. County-level predictors of housing quality (percent of households with high housing costs, overcrowding, and lack of kitchen or plumbing) were not significantly associated with county-level HISA utilization rate but are also nevertheless relevant to the discussion of home modifications. Of particular interest is the percent of households with lack of kitchen or plumbing variable, which was positively related to county-level HISA utilization rate although not statistically significant. HM elements related to the kitchen (eg, heighten countertop) add to the accessibility of the home allowing for the performing of activities of daily living such as cooking. Between FY 2015 and FY 2018, we discovered 131 prescriptions for kitchen (n = 90) and plumbing (n = 41) HMs, which is a very small proportion of the 30,780 total HMs (there were 24,397 bathroom HMs). The nonsignificant coefficient for this variable may reflect the small number of veterans that obtained these HM.

Limitations

The potentially conflicting direction of effects for a significant access to care variable (percent uninsured adults) and a significant access to care and quality of care variable (preventable hospital stays) are interesting and warrant additional study, but the inability to interpret or explain this apparent inconsistency constitutes a limitation of the current data and analyses presented here. Another limitation is that this analysis uses county-level predictors for what is ultimately an individual-level outcome. It would have been ideal to have both individual- and county-level data to conduct a multilevel analysis; in particular, individual-level data within counties of individuals (both veterans and nonveterans) who did not receive a HISA award (including both those who applied and were denied, and who did not apply) would be highly valuable.

Conclusions

Our continuing research into veterans’ use of HM fills a gap in the literature about the characteristics of HISA users, the impact of county-level variables on the use of HISA, and the geographic distribution and use of HISA within the VHA. While it is important to examine the influence of broader systems on individual outcomes, there could be myriad other factors that are more proximal and more closely related to whether any one individual applies for, let alone receives, a HISA award. Indeed, a low overall adjusted model R2 indicates that there is considerable variability in county-level HISA utilization rate that was not accounted for by the current model; this further speaks to warranted additional study.

More research is needed to understand and account for geographical variation in HISA utilization rate across the US. However, this work serves as an exploratory first step at quantifying and predicting HISA utilization rate at a broad level, with the ultimate goal of increasing access to HMs for veterans with disabilities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 15521 from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Furthermore, the research was supported in part by grant K12 HD055929 from the National Institutes of Health. We want to acknowledge Cheri E. Knecht, Project Coordinator, for her assistance throughout all aspects of our research study and for her thoughtful contributions during the writing of this manuscript.

This article is part of a series of articles on the Home Improvements and Structural Alterations program (HISA), a home modification (HM) program within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). HISA is a benefit awarded to veterans with disabilities (VWDs) and is instrumental in affording physical accessibility and structural alterations to veterans’ homes.1 The overarching goals of this project are to describe and understand HISA use by VWDs. Previous work has shown geographical variation in the number of HISA prescriptions across counties in the US (Figure 1).1 The current work seeks to describe and predict the county-level rates of HISA use. Information about what predicts HISA utilization at the county level is important because it enhances understanding of program utilization at a national level. The long-term goal of the series is to provide knowledge about HM services within VHA to improve community-based independent living of VWDs by increasing awareness and utilization of HM services.

Background

A health care professional (HCP) approves a HM support award by evaluating the practicality of the support to improve the built environment of a given veteran’s disability.1,2 Previously we detailed some of the preliminary research into the HISA program, including HISA user demographic and clinical characteristics, types of HMs received, user suggestions for improvement, and geospatial analysis of HISA prescriptions concentration.1-4

The geospatial analyses of HISA prescriptions revealed clusters of high numbers of HISA users (hot spots) and low numbers of HISA users (cold spots), indicating that HISA is either not prescribed or uniformly used across the US. The previous research prompted investigation into county-level variables that may impact HISA utilization rates. This inquiry focuses on county characteristics associated with HISA use rates, such as measures of clinical care and quality of care (eg, access to health services variables, lack of insurance, preventable hospital stays), physical environment, and sociodemographic characteristics. Clinical care and quality of care measures promote the interaction with HCPs. Moreover, access to health care is an important indicator of health outcomes.5,6 An individual’s capacity to access health services, such as a HM program, greatly impacts well-being, safety, independence, and health.2,4 Well-being, safety, independence, and health become compromised if individuals cannot access care, if needed care is lacking in their area, if HCPs are not available, or are unwilling to provide care due to lack of insurance coverage.7-12 In locations where health care services are minimal due to lack of specialists or health care facilities, the quality of (or access to) care may be compromised, resulting in preventable conditions becoming problematic.13,14 These conditions may result in unnecessary hospitalizations for conditions that could have been treated during routine care. Financial barriers to care particularly among low-income people and the uninsured have proven detrimental to health.15,16 On the other hand, preventable hospital stays are a quality of care measure (ie, a proxy for poor quality of care). HISA operates within a health care system; thus, it is imperative to include these measures impacting health.

In this study, we sought to identify county-level predictors—in particular, county-level proxies for access to care—that may be associated with county-level HISA use. We define HISA utilization rate as the percentage of a county’s VHA patients who have received a HISA award.

Methods

This study used data from the National Prosthetics Patient Database (NPPD), US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) medical database inpatient and outpatient datasets, VHA Support Service Center (VSSC) data cubes, and the County Health Rankings database (CHRD). First, the study cohort was identified from NPPD users who have obtained a HISA award from fiscal years (FY) 2015 to 2018. Analysis started with FY 2015 following new regulations (38 CFR § 17) governing the operations of the HISA program.2 The study cohort was matched with records from NPPD and VA inpatient and outpatient datasets to obtain information about the veterans’ demographic characteristics and their HM characteristics and costs. The number of VHA end-of-year (EOY) patients per county was extracted from the VSSC Current Enrollment Cube, which was used in calculation of the county-level HISA utilization rate.17 Finally, zip code–based locational data were used to calculate approximate drive time and distance from the HISA user’s approximate location to the facility where they received their HM prescription. Drive times and drive distances were calculated with Esri ArcGIS Pro (v2.6.3) by placing zip code centroid and VHA facilities on a nationwide road network that contains both road speeds and distances.

Calculations

Patient-level data were aggregated up to county-level variables by calculating the sum, mean, or percent per county. HISA user sample characteristics, including sex, race, rurality (urban, rural), marital status, and Class 1 vs Class 2 disability-related eligibility groups, were aggregated to the county level by calculating percentages of HISA users of the given characteristics out of total HISA users in the county. Disability-related eligibility groups (Class 1 vs Class 2 HISA users) determines the maximum lifetime award dollar amount. Specifically, those with service-connected disabilities or those with a ≥ 50% disability rating (regardless of whether or not their disability is service connected) are classified as Class 1 HISA users and are eligible to receive a maximum lifetime award of $6800. Those with a recorded disability that is not connected to their military service, and who have a disability rating of < 50% are classified as Class 2 HISA users and are eligible to receive a lifetime maximum award of $2000.

The county-level number of HISA users was used as the numerator for calculation of county-level HISA utilization rate. Counties with zero HISA users were excluded. The number of EOY VHA patients per county in FY 2018 was divided by 1000 and used as the denominator in the calculation of county-level HISA utilization rate. Thus, the outcome variable is HISA utilization rate per 1000 VHA patients in FY 2018 (HISA utilization rate).

County-Level Variables

County-level variables were downloaded from the 2020 CHRD.5,6 An explanation of the CHRD model and the factors used in this study are shown in the eAppendix (available at doi: 10.12788/fp.0279).6 County-level aggregated HISA user data and the CHRD data were matched using county Federal Information Processing Standards codes. Access to care measures collected from CHRD included percentages uninsured and ratios of population to primary care physicians, dentists, mental health professionals, and other primary care professionals. Other CHRD measures included those for quality of care (rate of preventable hospital stay) and housing quality (percent of households with high housing costs, percent of households with overcrowding, percent of households with lack of kitchen or plumbing, percent of households with severe housing cost burden, percent of homeownership). Of secondary interest was county population rurality, as previous research findings showed the annual average of HISA users who are from rural areas ranged from 30 to 35%.

Analysis Methods

SAS (v9.4), R (v4.0.2), and RStudio (v1.3.1093) were used for data preparation and analysis.18 Multiple regression analysis was used to predict county-level utilization rate from county-level variables. Sociodemographic characteristics from CHRD and HISA data were included as important control predictors in the regression model, though our focus for this paper are the access to care and housing quality predictors.

Model diagnostics (examination of model residuals, Breusch-Godfrey test, Breusch-Pagan test) revealed significant heteroskedasticity of the model; thus, robust standard errors and associated P values were computed using the R estimatr package (v0.30.2).19 Some predictor variables of interest (eg, ratio of mental health professionals) were removed during the model building process either due to problems of multicollinearity or excessive missingness that would have resulted in listwise deletion.

Results

County-level HISA utilization rate per 1000 EOY VHA patients ranged from 0.09 to 59.7%, with a 6.6% mean and 5% median (Figure 2). The data were highly positively skewed. The final model included 33 total predictor variables (Table 1). The final regression model was a significantly better predictor of county-level HISA utilization rate than a null model (F[33-2184], 10.18; P < .001). The adjusted model R2 showed that the overall model accounted for approximately 23% of variance in county-level HISA utilization rate (Table 2).

Among the primary variables of interest, percent uninsured adults and rate of preventable hospital stays emerged as significant predictors of county-level HISA utilization rate. Specifically, county percentage of uninsured adults was negatively related to county-level HISA utilization rate (b = -8.99, P = .005), indicating that the higher the proportion of uninsured adults—with all other predictors held constant—the lower the HISA utilization rate. Percent uninsured adults ranged from 2.7 to 42.4% across counties, with a mean (SD) of 12.7% (5.8%) and 11.4% median.

County rate of preventable hospital stays, however, was significantly and positively related to county-level HISA utilization rate (b = .0004, P = .009), indicating that the higher the rate of preventable hospital stays—with all other predictors held constant—the higher the HISA utilization rate. The direction of this effect is the opposite of the direction of the effect of percent uninsured adults (positive rather than negative), even though both could be considered measures of access to care. The standardized β for these 2 predictors indicate that county rate of preventable hospital stays is a somewhat stronger predictor of county-level HISA utilization rate than is county percent of uninsured adults (β = .11 and β = -.09, respectively). Rate of preventable hospital stays ranged from 683 to 16,802 across counties included in this analysis, with a mean (SD) of 4,796.5 (1659.9) and a 4669 median.

Of secondary interest was county rurality. The county-level percentage of rural residents was significantly and positively related to county-level HISA utilization rate, indicating that the higher the proportion of individuals within county considered rural—all other predictors held constant—the higher the HISA utilization rate. The mean (SD) percentage of rural residents per county was 52.3% (30.2) and 52.7 % median.

Discussion

This study examined whether county-level characteristics, specifically variables for access to care, quality of care, and housing quality, were predictive of a county’s HISA utilization rate. Given that this series of work on the HISA program is (to our knowledge) the first of its kind, and given the exploratory nature of this analysis, we did not have specific predictions for the effects of any one given variable. Nevertheless, some of the results were surprising, and we believe they warrant additional study. In particular, the opposing direction of effects for access to care and quality of care variables were hard to reconcile.

The county percent of uninsured adults (an access to care variable, specifically, a proxy for poor access to care) was negatively associated with county-level HISA utilization rate, whereas the county rate of preventable hospital stays (a quality of care variable, but also potentially an access to care variable, and specifically, proxies for poor quality of care or poor access to care) was positively associated with county-level HISA utilization rate. To describe the relationships more generally, one coefficient in the regression model indicated that the poorer the access to care, the lower the HISA utilization rate (higher percent of uninsured adults predicts lower HISA utilization rate), while another coefficient in the regression model indicated the poorer the quality of and access to care, the higher the HISA utilization rate (higher rate of preventable hospital stays predicts higher HISA utilization rate). Future study is warranted to disentangle and reconcile the various community-level predictors of this service.

Housing quality measures (eg, percent of households with high housing costs, percent of households with overcrowding, percent of households with lack of kitchen or plumbing, percent of households with severe housing cost burden, and percent of homeownership) are important in the consideration of whether a HM will be performed or should be performed. For example, if a person is cost burdened by the amount of expenditure spent in housing there will be little discretionary funds to perform a HM. Individuals who do not own their home may experience complications in obtaining permission from landlords to perform a HM. County-level predictors of housing quality (percent of households with high housing costs, overcrowding, and lack of kitchen or plumbing) were not significantly associated with county-level HISA utilization rate but are also nevertheless relevant to the discussion of home modifications. Of particular interest is the percent of households with lack of kitchen or plumbing variable, which was positively related to county-level HISA utilization rate although not statistically significant. HM elements related to the kitchen (eg, heighten countertop) add to the accessibility of the home allowing for the performing of activities of daily living such as cooking. Between FY 2015 and FY 2018, we discovered 131 prescriptions for kitchen (n = 90) and plumbing (n = 41) HMs, which is a very small proportion of the 30,780 total HMs (there were 24,397 bathroom HMs). The nonsignificant coefficient for this variable may reflect the small number of veterans that obtained these HM.

Limitations

The potentially conflicting direction of effects for a significant access to care variable (percent uninsured adults) and a significant access to care and quality of care variable (preventable hospital stays) are interesting and warrant additional study, but the inability to interpret or explain this apparent inconsistency constitutes a limitation of the current data and analyses presented here. Another limitation is that this analysis uses county-level predictors for what is ultimately an individual-level outcome. It would have been ideal to have both individual- and county-level data to conduct a multilevel analysis; in particular, individual-level data within counties of individuals (both veterans and nonveterans) who did not receive a HISA award (including both those who applied and were denied, and who did not apply) would be highly valuable.

Conclusions

Our continuing research into veterans’ use of HM fills a gap in the literature about the characteristics of HISA users, the impact of county-level variables on the use of HISA, and the geographic distribution and use of HISA within the VHA. While it is important to examine the influence of broader systems on individual outcomes, there could be myriad other factors that are more proximal and more closely related to whether any one individual applies for, let alone receives, a HISA award. Indeed, a low overall adjusted model R2 indicates that there is considerable variability in county-level HISA utilization rate that was not accounted for by the current model; this further speaks to warranted additional study.

More research is needed to understand and account for geographical variation in HISA utilization rate across the US. However, this work serves as an exploratory first step at quantifying and predicting HISA utilization rate at a broad level, with the ultimate goal of increasing access to HMs for veterans with disabilities.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant 15521 from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. Furthermore, the research was supported in part by grant K12 HD055929 from the National Institutes of Health. We want to acknowledge Cheri E. Knecht, Project Coordinator, for her assistance throughout all aspects of our research study and for her thoughtful contributions during the writing of this manuscript.

1. Semeah LM, Ahrentzen S, Jia H, Cowper-Ripley DC, Levy CE, Mann WC. The home improvements and structural alterations benefits program: veterans with disabilities and home accessibility. J Disability Policy Studies. 2017;28(1):43-51. doi:10.1177/1044207317696275

2. Semeah LM, Wang X, Cowper Ripley DC, Lee MJ, Ahonle ZJ, Ganesh SP, et al. Improving health through a home modification service for veterans. In: Fiedler BA, ed. Three Facets of Public Health and Paths to Improvements. Academic Press; 2020:381-416.

3. Semeah LM, Ahrentzen S, Cowper-Ripley DC, Santos-Roman LM, Beamish JO, Farley K. Rental housing needs and barriers from the perspective of veterans with disabilities. Housing Policy Debate. 2019;29(4):542-558. doi:10.1080/10511482.2018.1543203

4. Semeah LM, Ganesh SP, Wang X, et al. Home modification and health services utilization by rural and urban veterans with disabilities. Housing Policy Debate. 2021;31(6):862-874.doi:10.1080/10511482.2020.1858923

5. University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County health rankings model. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/about-us

6. Remington PL, Catlin BB, Gennuso KP. The County Health Rankings: rationale and methods. Popul Health Metr. 2015;13(11). doi:10.1186/s12963-015-0044-2

7. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Health-Care Utilization as a Proxy in Disability Determination. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018.

8. Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, Biswas S. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health. 2015;129(6):611-20. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.001

9. Medicaid and Chip Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Medicaid access in brief: adults’ experiences in obtaining medical care. November 2016. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/access-in-brief-adults-experiences-in-obtaining-medical-care

10. Tolbert J, Orgera, K, Damico A. Key facts about the uninsured population. November 6, 2020. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population

11. Meit M, Knudson A, Gilbert T, et al. The 2014 update of the rural-urban chartbook, 2014. October 2014. Accessed May 13, 2022. http://www.ruralhealthresearch.org

12. National Center for Health Statistics (US). Report No.: 2016-1232. Health, United States, 2015: with special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

13. Broussard DL, Mason KE, Carruth AR, Carton TW. Assessing potentially preventable hospitalizations at the county level: a comparison of measures using Medicare data and state hospital discharge data. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21(6):438-445. doi:10.1089/pop.2017.0141

14. Pezzin LE, Bogner HR, Kurichi JE, et al. Preventable hospitalizations, barriers to care, and disability. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0691 doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010691

15. Davis K, Ballreich J. Equitable access to care: how the United States ranks internationally. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1567-70. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1406707

16. Squires D, Anderson C. U.S. health care from a global perspective: spending, use of services, prices, and health in 13 countries. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2015;15:1-15.

17. VHA Service Support Center. Current enrollment cube (vssc.med.va.gov). Retrieved August 06, 2019. [Data not verified.]

18. Bunn A, Korpela M. R: A language and environment for statistical computing: an introduction to dplR. January 29, 2021. Accessed May 13, 2022. http://r.meteo.uni.wroc.pl/web/packages/dplR/vignettes/intro-dplR.pdf

19. Sheppard BH, Hartwick J, Warshaw PR. The theory of reasoned action: a meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. J Consumer Research. 1988;15(3):325-343. doi:10.1086/209170

1. Semeah LM, Ahrentzen S, Jia H, Cowper-Ripley DC, Levy CE, Mann WC. The home improvements and structural alterations benefits program: veterans with disabilities and home accessibility. J Disability Policy Studies. 2017;28(1):43-51. doi:10.1177/1044207317696275

2. Semeah LM, Wang X, Cowper Ripley DC, Lee MJ, Ahonle ZJ, Ganesh SP, et al. Improving health through a home modification service for veterans. In: Fiedler BA, ed. Three Facets of Public Health and Paths to Improvements. Academic Press; 2020:381-416.

3. Semeah LM, Ahrentzen S, Cowper-Ripley DC, Santos-Roman LM, Beamish JO, Farley K. Rental housing needs and barriers from the perspective of veterans with disabilities. Housing Policy Debate. 2019;29(4):542-558. doi:10.1080/10511482.2018.1543203

4. Semeah LM, Ganesh SP, Wang X, et al. Home modification and health services utilization by rural and urban veterans with disabilities. Housing Policy Debate. 2021;31(6):862-874.doi:10.1080/10511482.2020.1858923

5. University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute. County health rankings model. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/about-us

6. Remington PL, Catlin BB, Gennuso KP. The County Health Rankings: rationale and methods. Popul Health Metr. 2015;13(11). doi:10.1186/s12963-015-0044-2

7. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Health-Care Utilization as a Proxy in Disability Determination. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018.

8. Douthit N, Kiv S, Dwolatzky T, Biswas S. Exposing some important barriers to health care access in the rural USA. Public Health. 2015;129(6):611-20. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2015.04.001

9. Medicaid and Chip Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC). Medicaid access in brief: adults’ experiences in obtaining medical care. November 2016. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/access-in-brief-adults-experiences-in-obtaining-medical-care

10. Tolbert J, Orgera, K, Damico A. Key facts about the uninsured population. November 6, 2020. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population

11. Meit M, Knudson A, Gilbert T, et al. The 2014 update of the rural-urban chartbook, 2014. October 2014. Accessed May 13, 2022. http://www.ruralhealthresearch.org

12. National Center for Health Statistics (US). Report No.: 2016-1232. Health, United States, 2015: with special feature on racial and ethnic health disparities. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

13. Broussard DL, Mason KE, Carruth AR, Carton TW. Assessing potentially preventable hospitalizations at the county level: a comparison of measures using Medicare data and state hospital discharge data. Popul Health Manag. 2018;21(6):438-445. doi:10.1089/pop.2017.0141

14. Pezzin LE, Bogner HR, Kurichi JE, et al. Preventable hospitalizations, barriers to care, and disability. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0691 doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000010691

15. Davis K, Ballreich J. Equitable access to care: how the United States ranks internationally. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(17):1567-70. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1406707

16. Squires D, Anderson C. U.S. health care from a global perspective: spending, use of services, prices, and health in 13 countries. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2015;15:1-15.

17. VHA Service Support Center. Current enrollment cube (vssc.med.va.gov). Retrieved August 06, 2019. [Data not verified.]

18. Bunn A, Korpela M. R: A language and environment for statistical computing: an introduction to dplR. January 29, 2021. Accessed May 13, 2022. http://r.meteo.uni.wroc.pl/web/packages/dplR/vignettes/intro-dplR.pdf

19. Sheppard BH, Hartwick J, Warshaw PR. The theory of reasoned action: a meta-analysis of past research with recommendations for modifications and future research. J Consumer Research. 1988;15(3):325-343. doi:10.1086/209170

Home Modifications for Rural Veterans With Disabilities

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) created the Home Improvements and Structural Alterations (HISA) program to help provide necessary home modifications (HMs) to veterans with disabilities (VWDs) that will facilitate the provision of medical services at home and improve home accessibility and functional independence. The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has more than 9 million veteran enrollees; of those, 2.7 million are classified as rural or highly rural.1 Rural veterans (RVs) possess higher rate of disability compared with that of urban veterans.2-5 RVs have unequal access to screening of ambulatory care sensitive conditions (eg, hypertension, diabetes mellitus).6 Furthermore, RVs are at risk of poor medical outcomes due to distance from health care facilities and specialist care, which can be a barrier to emergency care when issues arise. These barriers, among others, are associated with compromised health quality of life and health outcomes for RVs.3,6 The HISA program may be key to decreasing falls and other serious mishaps in the home. Therefore, understanding use of the HISA program by RVs is important. However, to date little information has been available regarding use of HISA benefits by RVs or characteristics of RVs who receive HISA benefits.

HISA Alterations Program

HISA was initially developed by VA to improve veterans’ transition from acute medical care to home.7,8 However, to obtain HISA grants currently, there is an average 3 to 6 months application process.7 Through the HISA program, VWDs can be prescribed the following HMs, including (but not limited to): flooring replacement, permanent ramps, roll-in showers, installation of central air-conditioning systems, improved lighting, kitchen/bathroom modifications, and home inspections. The HMs prescribed depend on an assessment of medical need by health care providers (HCPs).8

As time passed and the veteran population aged, the program now primarily helps ensure the ability to enter into essential areas and safety in the home.5 The amount of a HISA payment is based on whether a veteran’s health condition is related to military service as defined by the VHA service connection medical evaluation process. Barriers to obtaining a HISA HM can include difficulty in navigating the evaluation process and difficulty in finding a qualified contractor or builder to do the HM.7

This article aims to: (1) Detail the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of rural HISA users (RHUs); (2) report on HISA usage patterns in number, types, and cost of HMs; (3) compare use amid the diverse VA medical centers (VAMCs) and related complexity levels and Veterans Integrated Service Networks (VISNs); and (4) examine the relationship between travel time/distance and HISA utilization. The long-term goal is to provide accurate information to researchers, HM administrators, health care providers and policy makers on HISA program utilization by rural VWDs, which may help improve its use and bring awareness of its users. This study was approved by the affiliate University of Florida Institutional Review Board and VA research and development committee at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System.

Methods

Data were obtained from 3 VA sources: the National Prosthetics Patient Database (NPPD), the VHA Medical Inpatient Dataset, and the VHA Outpatient Dataset.7 The NPPD is a national administrative database that contains information on prosthetic-associated products ordered by HCPs for patients, such as portable ramps, handrails, home oxygen equipment, and orthotic and prosthetic apparatus. Data obtained from the NPPD included cost of HMs, clinical characteristics, VISN, and VAMC. VA facilities are categorized into complexity levels 1a, 1b, 1c, 2, and 3. Complexity level 1a to 1c VAMCs address medical cases that entail “heightening involvedness,” meaning a larger number of patients presented with medical concerns needing medical specialists. Complexity levels 2 and 3 have fewer resources, lower patient numbers, and less medically complex patients. Finally, the VHA Medical Inpatient and Outpatient Datasets administrated by VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure, consist of in-depth health services national data on inpatient and outpatient encounters and procedures.

The study cohort was divided into those with service-connected conditions (Class 1) or those with conditions not related to military service (Class 2). If veterans were identified in both classes, they were assigned to Class 1. The cost variable is determined by using the veterans’ classification. Class 1 veterans receive a lifetime limit of $6800, and Class 2 veterans receive a lifetime limit of $2000. A Class 2 veteran with ≥ 50% disability rating is eligible for a HISA lifetime limit of $6800. Whenever a value exceeds allowed limit of $6800 or $2000, due to data entry error or other reasons, the study team reassigned the cost value to the maximum allowed value.

Travel distance and time were derived by loading patient zip codes and HISA facility locations into the geographical information system program and using the nearest facility and find-route tools. These tools used a road network that simulates real-world driving conditions to calculate distance.

Study Variables

VWDs of any age, gender, and race/ethnicity who qualified for HISA and received HMs from fiscal year ( FY) 2015 through FY 2018 were identified (N = 30,823). Most VWDs were nonrural subjects (n = 19,970), and 43 had no Federal Information Processing System data. The final study cohort consisted of 10,810 HISA recipients. The NPPD, inpatient and outpatient data were merged by scrambled social security numbers to retrieve the following data: age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, Class (1 or 2), mean and total number of inpatient days, and type of HMs prescribed.

We also recorded rurality using the VA Rural-Urban Commuting Areas (RUCA) system, but we combined the rural and highly rural designation.1 Census tracts with a RUCA score of 10.0 are deemed highly rural, the remainder are considered rural except those with a RUCA score of 1.0 or 1.1. Travel time and distance from a veteran’s home to the VA facility that provided the HISA prescription were determined from zip codes. The current study focuses on VAMCs prescribing stations (affiliated sites of administrative parent medical facilities) where the HISA users obtained the HM, not the parent station (administrative parent medical facilities).

HISA Utilization

To characterize HISA utilization geographically and over time, the number of users were mapped by county. Areas where users were increasing (hot spots) or decreasing (cold spots) also were mapped. The maps were created using Environmental Systems Research Institute ArcGIS Pro 2.2.1 software. We chose to use natural breaks (Jenks) data classification method in a choropleth to symbolize the change over time map. We then used the Getis Ord GI* optimized hot spot analysis tool in the ArcGIS Pro spatial statistics tool set to generate the hot/cold spot maps. This tool identifies clusters of high values (hot spots) and low values (cold spots) creating a new output layer, RHUs by county, with a Z score, P value, and CI for each county. The Gi Bin field classifies statistically significant hot and cold spots. Counties sorted into the ± 3 category (bin) have a clustering characteristic (eg, with neighboring counties) that is statistically significant with a 99% CI; the ± 2 bin indicates a 95% CI for those county clustering sorted therein; ± 1 reflects a 90% CI; and 0 bin contains county features that have no statistical significant clustering with neighboring counties.

Data Analysis

Data were cleaned and analyzed using SAS 9.4 and R 3.5.3. Descriptive statistics are provided for sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and class. ANOVA and t tests were used to compare continuous variables between groups, while χ2 and Fisher exact tests were used for dichotomous and categorical outcome variables. The threshold for statistical significance for these tests was set at α = .001.

Results

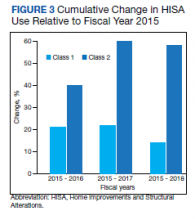

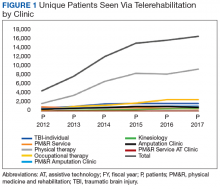

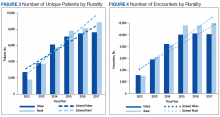

There were 10,810 RHUs from FY 2015 through FY 2018 and HISA utilization increased each year (Figure 1). Although some years may show usage decreases relative to previous fiscal years, the cumulative trends showed an increase relative to FY 2015 for both Classes of RVs (Figure 2). There was a 45.4% increase from FY 2015 to FY 2018 with a mean 13.6% yearly increase. Class 1 increased 21.0% and Class 2 increased 39.5% from FY 2015 to FY 2016 (Figure 3).

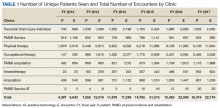

Most RHUs were male, White, and married. Class 1 and Class 2 RHUs differed significantly by age, race, marital status, and disability conditions: Class 1 RHUs were aged 6.6 years younger with a mean age of 69.1 years compared with 75.7 years for Class 2 users. For Class 1 RHUs, a plurality (29.4%) were aged 65 to 69 years; while a plurality (41.4%) of Class 2 users were aged ≥ 80 years. Musculoskeletal was the most common identified type of condition for all RHUs (Table 1).

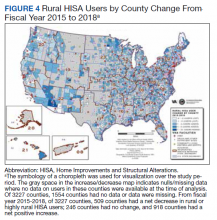

To better understand HISA utilization patterns and net RHUs per county, we used a map to detail RHUs by county and change over time (Figure 4). Additionally, we compared US counties by RHUs from FY 2015 to FY 2018 and determined how clusters of high numbers of RHUs (hot spots) and low numbers of RHUs (cold spots) shifted over this period (Figure 5). While HISA utilization grew over the study period, the net count of RHUs per county varied by 9 to 20 persons/county. The population of RHUs increased over time in the Southwest, Southeast, and over much of the East/Northeast, while in the Central and Midwest regions, number of RHUs seems to decrease in population and/or use of the system. The cold spots in the Midwest and South Central US seem to increase with a significant relationship to neighboring counties having a low number of RHUs.

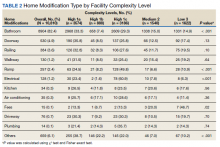

There were 11,166 HM prescribed to RHUs (Table 2). Bathroom HMs also were the dominant HM type for all facilities regardless of complexity levels (Table 3). The San Antonio, Texas, VAMC demonstrated the highest Class 1 vs Class 2 difference in HISA use (Class 1: 87.7% and Class 2: 12.3%). Except for the Des Moines VAMC, all other VAMCs showed HISA use > 60% by Class 1.

Cost Data

Air-conditioning installation ($5007) was the costliest HM overall (Table 4), closely followed by bathroom ($4978) and kitchen modifications ($4305). Bathroom renovations were the costliest HM type for both Class 1 and Class 2, closely followed by electrical repair and air-conditioning installation for Class 1 and driveway reconstruction and wooden ramp construction for Class 2.

The mean award received for HM was $4687 (Table 5). While the number of RHUs increased from FY 2015 to FY 2016, the average cost decreased, both overall ($280) and for Class 1 ($195) and Class 2 ($153). Except for a small decline in the number of Class 2 HISA recipients from FY 2017 to FY 2018, overall, the number of RHUs continuously grew from FY 2015 to FY 2018: 977 for the overall cohort, 678 for Class 1 and 299 for Class 2. Despite the obvious gain in the number of RHUs, the average costs did not notably change over time. VISN 21 had the highest mean cost, followed by VISNs 17, 6, 22, and 20.

Travel

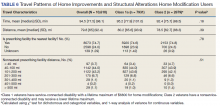

Travel time and distance to the HISA prescribing facility differed significantly between Class 1 and Class 2 HISA users. RHUs had to travel about 95 minutes from their place of residence to access the HISA benefits program. There were no statistically significant differences between Class 1 and 2 users with respect to travel time and distance traveled (Table 6).

The majority of Class 1 and Class 2 veterans accessed the HISA from their nearest facility. However, nearly one-quarter of both Class 1 and 2 RHUs (24% each) did not. Among the 2598 who accessed the nonnearest facility, 97 (3.7%) accessed a facility that is ≤ 40 miles. Many (44%) users traveled 40 to 100 miles, and another 43.2% traveled 100 to 200 miles from their residence to access a HM prescription. Some 2598 users (1.1%) traveled > 500 miles to access a facility.

Discussion

Although utilization of the HISA program has steadily increased, overall participation by subpopulations such as RHUs can still be improved significantly. Veterans aged ≤ 46 years who have a disability that is common to those receiving HISA benefits have low HISA utilization. Similarly, veterans with sensory disabilities also have low use. These subpopulations are among those in great need of attention and services.

A study by Lucas and Zelaya, using the 2016 National Health Interview Survey data with an aim to measure degree of vision problems, dual sensory impairment, and hearing trouble in male veterans aged ≥ 18 years, found that veterans were more likely to report dual sensory impairment and balance difficulties when compared with nonveterans.9 The number of female veterans is growing but had very low representation in this study.10 This emerging VHA population requires information and education on their HM benefits.

Home Modifications

The most common HM prescribed for RHUs was for the bathroom. Further investigation is warranted as to why, given the diversity of HM types that the grant covers, low prescription rates exist across most of the HM types. There may be a lack of knowledge by providers and VWD as to the range of HMs that can be awarded under the grant. It is important that HCPs and veterans receive education on HISA HM options.

Semeah and colleagues pointed out the need for an assessment of the HISA HM ordering system to ensure that multiple HMs items (eg, kitchen, air conditioning, fees, driveway, and plumbing) are listed among the forced choices shown to clinicians to select from.7 Poor housing in rural America is widespread: 63% of rural dwellings need renovations and/or repairs to be accessible to individuals with disabilities, with > 6.7 million rural homes having no or faulty plumbing or kitchens; yet in this study, prescriptions for these HMs accounted for < 1%.11,12

VISN 6 had the most HISA awards with 1364, while VISN 21 had the fewest (245). Across all VISNs, Class 1 RHUs received more prescriptions than did Class 2 RHUs. Future research may seek to examine whether prescribers are fully aware of the eligibility of HM prescription to Class 2 veterans. VISN 21 ($5354); VISN 17 ($5302); and VISN 6 ($5301) had the highest mean HM expenditures. The national mean cost for HISA HMs were $4978 for bathrooms and $4305 for kitchens; for non-HISA HMs in FY 2017, the mean costs were $6362 and $12,255, respectively. A noteworthy concern is whether the maximum grant limit awards are sufficient to perform more expensive and complex HMs, such as the kitchen or major bathroom alternations.13

Facilities categorized as 1a, 1b, or 1c provided

North Florida/Sough Georgia was the highest-prescribing VAMC with 39% more HM prescriptions than the second highest prescribing facility (Durham, NC). Unfortunately, the data presented here cannot establish causality for the large variance difference between the top facilities, and the skewed distribution of total RHUs across VAMCs.

Travel-Related Variables

HISA beneficiaries face significant travel-related challenges. Just 3.6% of RHUs could access a facility within 40 miles of their home and 43.2% traveled 100 to 200 miles from their home to access a HM prescription. Further exploration is warranted to understand how travel patterns impact access to or the uptake of HISA.

RVs already have problems with accessing care because of long travel time.14,15 The choice or necessity to travel to a farther facility for HISA prescription is problematic for RVs, especially when transportation is often reported in the literature as a barrier to resources for people living in rural communities.15-17 When patients have travel barriers, they wait longer to obtain medical services and often wait for their conditions to worsen before seeking services.15,18 Once HM is completed, telerehabilitation is an effective delivery method used for delivering health care services to people in remote places.18,19 Considering that HISA use has the potential to improve quality of life, afford comfort, facilitate the accomplishment of activities of daily living for RVs, it is important that future studies examine how existing telehealth technologies can be used to improve HISA access.

Future Directions

County-level analyses is warranted in future studies exploring potential variables associated with HISA use; for example, county-level rates of primary care physicians and other HCPs. Future research should explore how long distance travel impacts the HISA application process and HM implementation. Further research also should focus on the HISA application structure and process to identify causes of delays. The HISA application process takes a mean 6 months to complete, yet the duration of hospital stays is 1 to 3 weeks, thus it is impossible to connect HISA to hospital discharge, which was the original intent of the program. Future research can examine how telehealth services can expedite HISA obtainment and coordination of the application process. Future research also may study the possible causes of the wide variations in HM prescriptions per facility. It is also important that educational programs provide information on the array of HM items that veterans can obtain.

Conclusions