User login

Does early repolarization on ECG increase the risk of cardiac death in healthy people?

No. The early repolarization pattern on electrocardiography (ECG) in asymptomatic patients is nearly always a benign incidental finding. However, in a patient with a history of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation or a family history of sudden cardiac death, the finding warrants further evaluation.

DEFINING EARLY REPOLARIZATION

The early repolarization pattern may mimic patterns seen in myocardial infarction, pericarditis, ventricular aneurysm, hyperkalemia, and hypothermia,1,3 and misinterpreting the pattern can lead to unnecessary laboratory testing, imaging, medication use, and hospital admissions. On the other hand, misinterpreting it as benign in the presence of certain features of the history or clinical presentation can delay the diagnosis and treatment of a potentially critical condition.

PREVALENCE AND MECHANISMS

The prevalence of the early repolarization pattern in the general population ranges from 5% to 15%; the wide range reflects differences in the definition, as well as variability in the pattern of early repolarization over time.4

The early repolarization pattern is more commonly seen in African American men and in young, physically active individuals.3 In one study, it was observed in 15% of cases of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death, especially in people ages 35 to 45.4 While there is evidence of a heritable basis in the general population, a family history of early repolarization is not known to increase the risk of sudden cardiac death.

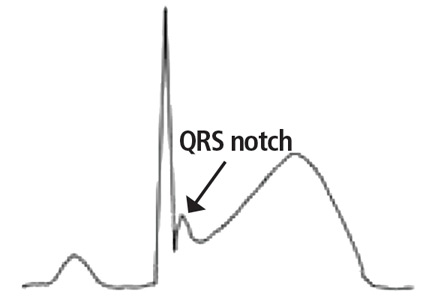

A proposed mechanism for the early repolarization pattern is an imbalance in the ion channel system, resulting in variable refractoriness of multiple myocardial regions and varying excitability in the myocardium. This can produce a voltage gradient between myocardial regions, which is believed to cause the major hallmarks of the early repolarization pattern, ie, ST-segment elevation and QRS notching or slurring.3

MANAGEMENT

The early repolarization pattern is nearly always a benign incidental finding on ECG, with no specific signs or symptoms attributed to it. High-risk features on ECG are associated with a modest increase in absolute risk of sudden cardiac death and warrant clinical correlation.

In the absence of syncope or family history of sudden cardiac death, early repolarization does not merit further workup.2

In patients with a history of unexplained syncope and a family history of sudden cardiac death, early repolarization should be considered in overall risk stratification.1 Early repolarization in a patient with previous idiopathic ventricular fibrillation warrants referral for electrophysiologic study and, if indicated, insertion of an implantable cardiac defibrillator for secondary prevention.5

- Patton KK, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz M, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology. Electrocardiographic early repolarization: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016; 133(15):1520–1529. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000388

- Macfarlane PW, Antzelevitch C, Haissaguerre M, et al. The early repolarization pattern: a consensus paper. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66(4):470–477. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.033

- Benito B, Guasch E, Rivard L, Nattel S. Clinical and mechanistic issues in early repolarization of normal variants and lethal arrhythmia syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56(15):1177–1186. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.037

- Maury P, Rollin A. Prevalence of early repolarisation/J wave patterns in the normal population. J Electrocardiol 2013; 46(5):411–416. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2013.06.014

- Mahida S, Sacher F, Berte B, et al. Evaluation of patients with early repolarization syndrome. J Atr Fibrillation 2014; 7(3):1083. doi:10.4022/jafib.1083

No. The early repolarization pattern on electrocardiography (ECG) in asymptomatic patients is nearly always a benign incidental finding. However, in a patient with a history of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation or a family history of sudden cardiac death, the finding warrants further evaluation.

DEFINING EARLY REPOLARIZATION

The early repolarization pattern may mimic patterns seen in myocardial infarction, pericarditis, ventricular aneurysm, hyperkalemia, and hypothermia,1,3 and misinterpreting the pattern can lead to unnecessary laboratory testing, imaging, medication use, and hospital admissions. On the other hand, misinterpreting it as benign in the presence of certain features of the history or clinical presentation can delay the diagnosis and treatment of a potentially critical condition.

PREVALENCE AND MECHANISMS

The prevalence of the early repolarization pattern in the general population ranges from 5% to 15%; the wide range reflects differences in the definition, as well as variability in the pattern of early repolarization over time.4

The early repolarization pattern is more commonly seen in African American men and in young, physically active individuals.3 In one study, it was observed in 15% of cases of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death, especially in people ages 35 to 45.4 While there is evidence of a heritable basis in the general population, a family history of early repolarization is not known to increase the risk of sudden cardiac death.

A proposed mechanism for the early repolarization pattern is an imbalance in the ion channel system, resulting in variable refractoriness of multiple myocardial regions and varying excitability in the myocardium. This can produce a voltage gradient between myocardial regions, which is believed to cause the major hallmarks of the early repolarization pattern, ie, ST-segment elevation and QRS notching or slurring.3

MANAGEMENT

The early repolarization pattern is nearly always a benign incidental finding on ECG, with no specific signs or symptoms attributed to it. High-risk features on ECG are associated with a modest increase in absolute risk of sudden cardiac death and warrant clinical correlation.

In the absence of syncope or family history of sudden cardiac death, early repolarization does not merit further workup.2

In patients with a history of unexplained syncope and a family history of sudden cardiac death, early repolarization should be considered in overall risk stratification.1 Early repolarization in a patient with previous idiopathic ventricular fibrillation warrants referral for electrophysiologic study and, if indicated, insertion of an implantable cardiac defibrillator for secondary prevention.5

No. The early repolarization pattern on electrocardiography (ECG) in asymptomatic patients is nearly always a benign incidental finding. However, in a patient with a history of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation or a family history of sudden cardiac death, the finding warrants further evaluation.

DEFINING EARLY REPOLARIZATION

The early repolarization pattern may mimic patterns seen in myocardial infarction, pericarditis, ventricular aneurysm, hyperkalemia, and hypothermia,1,3 and misinterpreting the pattern can lead to unnecessary laboratory testing, imaging, medication use, and hospital admissions. On the other hand, misinterpreting it as benign in the presence of certain features of the history or clinical presentation can delay the diagnosis and treatment of a potentially critical condition.

PREVALENCE AND MECHANISMS

The prevalence of the early repolarization pattern in the general population ranges from 5% to 15%; the wide range reflects differences in the definition, as well as variability in the pattern of early repolarization over time.4

The early repolarization pattern is more commonly seen in African American men and in young, physically active individuals.3 In one study, it was observed in 15% of cases of idiopathic ventricular fibrillation and sudden cardiac death, especially in people ages 35 to 45.4 While there is evidence of a heritable basis in the general population, a family history of early repolarization is not known to increase the risk of sudden cardiac death.

A proposed mechanism for the early repolarization pattern is an imbalance in the ion channel system, resulting in variable refractoriness of multiple myocardial regions and varying excitability in the myocardium. This can produce a voltage gradient between myocardial regions, which is believed to cause the major hallmarks of the early repolarization pattern, ie, ST-segment elevation and QRS notching or slurring.3

MANAGEMENT

The early repolarization pattern is nearly always a benign incidental finding on ECG, with no specific signs or symptoms attributed to it. High-risk features on ECG are associated with a modest increase in absolute risk of sudden cardiac death and warrant clinical correlation.

In the absence of syncope or family history of sudden cardiac death, early repolarization does not merit further workup.2

In patients with a history of unexplained syncope and a family history of sudden cardiac death, early repolarization should be considered in overall risk stratification.1 Early repolarization in a patient with previous idiopathic ventricular fibrillation warrants referral for electrophysiologic study and, if indicated, insertion of an implantable cardiac defibrillator for secondary prevention.5

- Patton KK, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz M, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology. Electrocardiographic early repolarization: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016; 133(15):1520–1529. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000388

- Macfarlane PW, Antzelevitch C, Haissaguerre M, et al. The early repolarization pattern: a consensus paper. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66(4):470–477. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.033

- Benito B, Guasch E, Rivard L, Nattel S. Clinical and mechanistic issues in early repolarization of normal variants and lethal arrhythmia syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56(15):1177–1186. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.037

- Maury P, Rollin A. Prevalence of early repolarisation/J wave patterns in the normal population. J Electrocardiol 2013; 46(5):411–416. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2013.06.014

- Mahida S, Sacher F, Berte B, et al. Evaluation of patients with early repolarization syndrome. J Atr Fibrillation 2014; 7(3):1083. doi:10.4022/jafib.1083

- Patton KK, Ellinor PT, Ezekowitz M, et al; American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and Council on Functional Genomics and Translational Biology. Electrocardiographic early repolarization: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016; 133(15):1520–1529. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000388

- Macfarlane PW, Antzelevitch C, Haissaguerre M, et al. The early repolarization pattern: a consensus paper. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015; 66(4):470–477. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.05.033

- Benito B, Guasch E, Rivard L, Nattel S. Clinical and mechanistic issues in early repolarization of normal variants and lethal arrhythmia syndromes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56(15):1177–1186. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2010.05.037

- Maury P, Rollin A. Prevalence of early repolarisation/J wave patterns in the normal population. J Electrocardiol 2013; 46(5):411–416. doi:10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2013.06.014

- Mahida S, Sacher F, Berte B, et al. Evaluation of patients with early repolarization syndrome. J Atr Fibrillation 2014; 7(3):1083. doi:10.4022/jafib.1083

Do all hospital inpatients need cardiac telemetry?

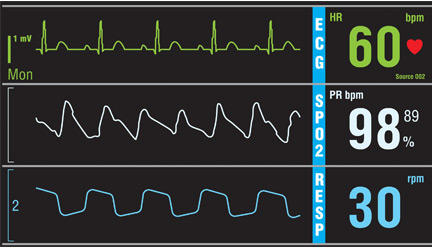

No. Continuous monitoring for changes in heart rhythm with cardiac telemetry is recommended for all patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU). But routine telemetry monitoring for patients in non-ICU beds is not recommended, as it leads to unnecessary testing and treatment, increasing the cost of care and hospital length of stay.

RISK STRATIFICATION AND INDICATIONS

Telemetry is generally recommended for patients admitted with any type of heart disease, including:

- Acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation or Q waves on 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG)

- Acute ischemia suggested by ST-segment depression or T-wave inversion on ECG

- Systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg

- Acute decompensated heart failure with bilateral rales above the lung bases

- Chest pain that is worse than or the same as that in prior angina or myocardial infarction.1,2

Indications for telemetry are less clear in patients with no history of heart disease. The American Heart Association (AHA)3 has classified admitted patients based on the presence or absence of heart disease3:

- Class I (high risk of arrhythmia): acute coronary syndrome, new arrhythmia (eg, atrial fibrillation or flutter), severe electrolyte imbalance; telemetry is warranted

- Class II (moderate risk): acute decompensated heart failure with stable hemodynamic status, a surgical or medical diagnosis with underlying paced rhythms (ie, with a pacemaker), and chronic arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation or flutter); in these cases, telemetry monitoring may be considered

- Class III (low risk): no history of cardiac disease or arrhythmias, admitted for medical or surgical reasons; in these cases, telemetry is generally not indicated3

Telemetry should also be considered in patients admitted with syncope or stroke, critical illness, or palpitations.

Syncope and stroke

Despite the wide use of telemetry for patients admitted with syncope, current evidence does not support this practice. However, the AHA recommends routine telemetry for patients admitted with idiopathic syncope when there is a high level of suspicion for underlying cardiac arrhythmias as a cause of syncope (risk class II-b).3 In 30% of patients admitted with stroke or transient ischemic attack, the cause is cardioembolic. Therefore, telemetry is indicated to rule out an underlying cardiac cause.4

Critical illness

Patients hospitalized with major trauma, acute respiratory failure, sepsis, shock, or acute pulmonary embolism or for major noncardiac surgery (especially elderly patients with coronary artery disease or at high risk of coronary events) require cardiac telemetry (risk class I-b). Patients admitted with kidney failure, significant electrolyte abnormalities, drug or substance toxicity (especially with known arrhythmogenic drugs) also require cardiac telemetry at the time of admission (risk class I-b).

Recurrent palpitations, arrhythmia

Most patients with palpitations can be evaluated in an outpatient setting.5 However, patients hospitalized for recurrent palpitations or for suspected underlying cardiac disease require telemetric monitoring (risk class II-b).3 Patients with high-degree atrioventricular block admitted after percutaneous temporary pacemaker implantation should be monitored, as should patients with a permanent pacemaker for 12 to 24 hours after implantation (risk class I-c). Also, patients hospitalized after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shock need to be monitored.3,6

Patients with a paced rhythm who do not meet the above criteria do not require routine telemetric monitoring (risk class III-c).7

TELEMETRY IS OVERUSED

Off-site telemetry monitoring can identify significant arrhythmias during hospitalization. It also saves time on nursing staff to focus on bedside patient care. However, its convenience can lower the threshold for ordering it. This can lead to overuse with a major impact on healthcare costs.

Routine use of cardiac telemetry is associated with increased hospitalization costs with little benefit.8 The use of off-site services for continuous monitoring can activate many alarms throughout the day, triggering unnecessary workups and leading to densensitization to alarms (“alarm fatigue”).9

Despite the precise indications outlined in the AHA updated practice standards for inpatient electrocardiographic monitoring,10 telemetry use is expanding to non-ICU units without evidence of benefit,8 and this overuse can result in harmful clinical outcomes and a financial burden. Telemetry monitoring of low-risk patients can cause delays in emergency department and ICU admissions and transfers8,11 of patients who may be sicker and need intensive care.

In a prospective observational study,12 only 11 (6%) of 182 patients admitted to a general medical floor met AHA class I criteria for telemetry; very few patients developed a significant telemetry event such as atrial fibrillation or flutter that necessitated a change in management. Most overprescribers of telemetry monitoring reason that it will catch arrhythmias early.12 In fact, in a study of patients in a cardiac unit, telemetry detected just 50% of in-house cardiac arrest cases, with a potential survival benefit of only 0.02%.13

Another study showed that only 0.01% of all telemetry alarms represented a real emergency. Only 37.2% of emergency alarms were classified as clinically important, and only 48.3% of these led to a change in management within 1 hour.14

Moreover, in a report of trauma patients with abnormal results on ECG at the time of admission, telemetry had negligible clinical benefit.15 And in a study of 414 patients, only 4% of those admitted with chest pain and normal initial ECG had cardiac interventions.16

Another study8 showed that hospital intervention to restrict the use of telemetry guided by AHA recommendations resulted in a 43% reduction in telemetry orders, a 47% reduction in telemetry duration, and a 70% reduction in the mean daily number of patients monitored, with no changes in hospital census or rates of code blue, death, or rapid response team activation.8

The financial cost can be seen in the backup of patients in the emergency department. A study showed that 91% of patients being admitted for chest pain were delayed by more than 3 hours while waiting for monitored beds. This translated into an annual cost of $168,300 to the hospital.17 Adherence to guidelines for appropriate use of telemetry can significantly decrease costs. Applying a simple algorithm for telemetry use was shown8 to decrease daily non-ICU cardiac telemetry costs from $18,971 to $5,772.

CURRENT GUIDELINES ARE LIMITED

The current American College of Cardiology and AHA guidelines are based mostly on expert opinion rather than randomized clinical trials, while most telemetry trials have been performed on patients with a cardiac or possible cardiac diagnosis.3 Current guidelines need to be updated, and more studies are needed to specify the optimal duration of cardiac monitoring in indicated cases. Many noncardiac conditions raise a legitimate concern of dysrhythmia, an indication for cardiac monitoring, but precise recommendations for telemetry for such conditions are lacking.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Raising awareness of the clinical and financial burdens associated with unwise telemetry utilization is critical. We suggest use of a pop-up notification in the electronic medical record to remind the provider of the existing telemetry order and to specify the duration of telemetry monitoring when placing the initial order. The goal is to identify patients in true need of a telemetry bed, to decrease unnecessary testing, and to reduce hospitalization costs.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991; 18(6):1431–1433. pmid:1939942

- Goldman L, Cook EF, Johnson PA, Brand DA, Rouan GW, Lee TH. Prediction of the need for intensive care in patients who come to emergency departments with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med 1996; 334(23):1498–1504. doi:10.1056/NEJM199606063342303

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al; American Heart Association; Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation 2004;110(17):2721–2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59

- Ustrell X, Pellise A. Cardiac workup of ischemic stroke. Curr Cardiol Rev 2010; 6(3):175-183. doi:10.2174/157340310791658721

- Olson JA, Fouts AM, Padanilam BJ, Prystowsky EN. Utility of mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry for the diagnosis of palpitations, presyncope, syncope, and the assessment of therapy efficacy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2007; 18(5):473–477. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00779.x

- Chen EH, Hollander JE. When do patients need admission to a telemetry bed? J Emerg Med 2007; 33(1):53–60. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.01.017

- Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, et al; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Update to practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 136(19):e273–e344. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000527

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174(11):1852–1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491

- Cantillon DJ, Loy M, Burkle A, et al. Association between off-site central monitoring using standardized cardiac telemetry and clinical outcomes among non–critically ill patients. JAMA 2016; 316(5):519–524. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.10258

- Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, et al. Update to practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 136(19):e273–e344. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000527

- Atzema C, Schull MJ, Borgundvaag B, Slaughter GR, Lee CK. ALARMED: adverse events in low-risk patients with chest pain receiving continuous electrocardiographic monitoring in the emergency department. A pilot study. Am J Emerg Med 2006; 24(1):62–67. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.015

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(17):1349–1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163

- Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and cardiac arrest outcomes in 8,932 telemetry ward patients. Acad Emerg Med 2000; 7(6):647–652. pmid:10905643

- Kansara P, Jackson K, Dressler R, et al. Potential of missing life-threatening arrhythmias after limiting the use of cardiac telemetry. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175(8):1416–1418. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2387

- Nagy KK, Krosner SM, Roberts RR, Joseph KT, Smith RF, Barrett J. Determining which patients require evaluation for blunt cardiac injury following blunt chest trauma. World J Surg 2001; 25(1):108–111. pmid:11213149

- Snider A, Papaleo M, Beldner S, et al. Is telemetry monitoring necessary in low-risk suspected acute chest pain syndromes? Chest 2002; 122(2):517–523. pmid:12171825

- Bayley MD, Schwartz JS, Shofer FS, et al. The financial burden of emergency department congestion and hospital crowding for chest pain patients awaiting admission. Ann Emerg Med 2005; 45(2):110–117. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.09.010

No. Continuous monitoring for changes in heart rhythm with cardiac telemetry is recommended for all patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU). But routine telemetry monitoring for patients in non-ICU beds is not recommended, as it leads to unnecessary testing and treatment, increasing the cost of care and hospital length of stay.

RISK STRATIFICATION AND INDICATIONS

Telemetry is generally recommended for patients admitted with any type of heart disease, including:

- Acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation or Q waves on 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG)

- Acute ischemia suggested by ST-segment depression or T-wave inversion on ECG

- Systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg

- Acute decompensated heart failure with bilateral rales above the lung bases

- Chest pain that is worse than or the same as that in prior angina or myocardial infarction.1,2

Indications for telemetry are less clear in patients with no history of heart disease. The American Heart Association (AHA)3 has classified admitted patients based on the presence or absence of heart disease3:

- Class I (high risk of arrhythmia): acute coronary syndrome, new arrhythmia (eg, atrial fibrillation or flutter), severe electrolyte imbalance; telemetry is warranted

- Class II (moderate risk): acute decompensated heart failure with stable hemodynamic status, a surgical or medical diagnosis with underlying paced rhythms (ie, with a pacemaker), and chronic arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation or flutter); in these cases, telemetry monitoring may be considered

- Class III (low risk): no history of cardiac disease or arrhythmias, admitted for medical or surgical reasons; in these cases, telemetry is generally not indicated3

Telemetry should also be considered in patients admitted with syncope or stroke, critical illness, or palpitations.

Syncope and stroke

Despite the wide use of telemetry for patients admitted with syncope, current evidence does not support this practice. However, the AHA recommends routine telemetry for patients admitted with idiopathic syncope when there is a high level of suspicion for underlying cardiac arrhythmias as a cause of syncope (risk class II-b).3 In 30% of patients admitted with stroke or transient ischemic attack, the cause is cardioembolic. Therefore, telemetry is indicated to rule out an underlying cardiac cause.4

Critical illness

Patients hospitalized with major trauma, acute respiratory failure, sepsis, shock, or acute pulmonary embolism or for major noncardiac surgery (especially elderly patients with coronary artery disease or at high risk of coronary events) require cardiac telemetry (risk class I-b). Patients admitted with kidney failure, significant electrolyte abnormalities, drug or substance toxicity (especially with known arrhythmogenic drugs) also require cardiac telemetry at the time of admission (risk class I-b).

Recurrent palpitations, arrhythmia

Most patients with palpitations can be evaluated in an outpatient setting.5 However, patients hospitalized for recurrent palpitations or for suspected underlying cardiac disease require telemetric monitoring (risk class II-b).3 Patients with high-degree atrioventricular block admitted after percutaneous temporary pacemaker implantation should be monitored, as should patients with a permanent pacemaker for 12 to 24 hours after implantation (risk class I-c). Also, patients hospitalized after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shock need to be monitored.3,6

Patients with a paced rhythm who do not meet the above criteria do not require routine telemetric monitoring (risk class III-c).7

TELEMETRY IS OVERUSED

Off-site telemetry monitoring can identify significant arrhythmias during hospitalization. It also saves time on nursing staff to focus on bedside patient care. However, its convenience can lower the threshold for ordering it. This can lead to overuse with a major impact on healthcare costs.

Routine use of cardiac telemetry is associated with increased hospitalization costs with little benefit.8 The use of off-site services for continuous monitoring can activate many alarms throughout the day, triggering unnecessary workups and leading to densensitization to alarms (“alarm fatigue”).9

Despite the precise indications outlined in the AHA updated practice standards for inpatient electrocardiographic monitoring,10 telemetry use is expanding to non-ICU units without evidence of benefit,8 and this overuse can result in harmful clinical outcomes and a financial burden. Telemetry monitoring of low-risk patients can cause delays in emergency department and ICU admissions and transfers8,11 of patients who may be sicker and need intensive care.

In a prospective observational study,12 only 11 (6%) of 182 patients admitted to a general medical floor met AHA class I criteria for telemetry; very few patients developed a significant telemetry event such as atrial fibrillation or flutter that necessitated a change in management. Most overprescribers of telemetry monitoring reason that it will catch arrhythmias early.12 In fact, in a study of patients in a cardiac unit, telemetry detected just 50% of in-house cardiac arrest cases, with a potential survival benefit of only 0.02%.13

Another study showed that only 0.01% of all telemetry alarms represented a real emergency. Only 37.2% of emergency alarms were classified as clinically important, and only 48.3% of these led to a change in management within 1 hour.14

Moreover, in a report of trauma patients with abnormal results on ECG at the time of admission, telemetry had negligible clinical benefit.15 And in a study of 414 patients, only 4% of those admitted with chest pain and normal initial ECG had cardiac interventions.16

Another study8 showed that hospital intervention to restrict the use of telemetry guided by AHA recommendations resulted in a 43% reduction in telemetry orders, a 47% reduction in telemetry duration, and a 70% reduction in the mean daily number of patients monitored, with no changes in hospital census or rates of code blue, death, or rapid response team activation.8

The financial cost can be seen in the backup of patients in the emergency department. A study showed that 91% of patients being admitted for chest pain were delayed by more than 3 hours while waiting for monitored beds. This translated into an annual cost of $168,300 to the hospital.17 Adherence to guidelines for appropriate use of telemetry can significantly decrease costs. Applying a simple algorithm for telemetry use was shown8 to decrease daily non-ICU cardiac telemetry costs from $18,971 to $5,772.

CURRENT GUIDELINES ARE LIMITED

The current American College of Cardiology and AHA guidelines are based mostly on expert opinion rather than randomized clinical trials, while most telemetry trials have been performed on patients with a cardiac or possible cardiac diagnosis.3 Current guidelines need to be updated, and more studies are needed to specify the optimal duration of cardiac monitoring in indicated cases. Many noncardiac conditions raise a legitimate concern of dysrhythmia, an indication for cardiac monitoring, but precise recommendations for telemetry for such conditions are lacking.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Raising awareness of the clinical and financial burdens associated with unwise telemetry utilization is critical. We suggest use of a pop-up notification in the electronic medical record to remind the provider of the existing telemetry order and to specify the duration of telemetry monitoring when placing the initial order. The goal is to identify patients in true need of a telemetry bed, to decrease unnecessary testing, and to reduce hospitalization costs.

No. Continuous monitoring for changes in heart rhythm with cardiac telemetry is recommended for all patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU). But routine telemetry monitoring for patients in non-ICU beds is not recommended, as it leads to unnecessary testing and treatment, increasing the cost of care and hospital length of stay.

RISK STRATIFICATION AND INDICATIONS

Telemetry is generally recommended for patients admitted with any type of heart disease, including:

- Acute myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation or Q waves on 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG)

- Acute ischemia suggested by ST-segment depression or T-wave inversion on ECG

- Systolic blood pressure less than 100 mm Hg

- Acute decompensated heart failure with bilateral rales above the lung bases

- Chest pain that is worse than or the same as that in prior angina or myocardial infarction.1,2

Indications for telemetry are less clear in patients with no history of heart disease. The American Heart Association (AHA)3 has classified admitted patients based on the presence or absence of heart disease3:

- Class I (high risk of arrhythmia): acute coronary syndrome, new arrhythmia (eg, atrial fibrillation or flutter), severe electrolyte imbalance; telemetry is warranted

- Class II (moderate risk): acute decompensated heart failure with stable hemodynamic status, a surgical or medical diagnosis with underlying paced rhythms (ie, with a pacemaker), and chronic arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation or flutter); in these cases, telemetry monitoring may be considered

- Class III (low risk): no history of cardiac disease or arrhythmias, admitted for medical or surgical reasons; in these cases, telemetry is generally not indicated3

Telemetry should also be considered in patients admitted with syncope or stroke, critical illness, or palpitations.

Syncope and stroke

Despite the wide use of telemetry for patients admitted with syncope, current evidence does not support this practice. However, the AHA recommends routine telemetry for patients admitted with idiopathic syncope when there is a high level of suspicion for underlying cardiac arrhythmias as a cause of syncope (risk class II-b).3 In 30% of patients admitted with stroke or transient ischemic attack, the cause is cardioembolic. Therefore, telemetry is indicated to rule out an underlying cardiac cause.4

Critical illness

Patients hospitalized with major trauma, acute respiratory failure, sepsis, shock, or acute pulmonary embolism or for major noncardiac surgery (especially elderly patients with coronary artery disease or at high risk of coronary events) require cardiac telemetry (risk class I-b). Patients admitted with kidney failure, significant electrolyte abnormalities, drug or substance toxicity (especially with known arrhythmogenic drugs) also require cardiac telemetry at the time of admission (risk class I-b).

Recurrent palpitations, arrhythmia

Most patients with palpitations can be evaluated in an outpatient setting.5 However, patients hospitalized for recurrent palpitations or for suspected underlying cardiac disease require telemetric monitoring (risk class II-b).3 Patients with high-degree atrioventricular block admitted after percutaneous temporary pacemaker implantation should be monitored, as should patients with a permanent pacemaker for 12 to 24 hours after implantation (risk class I-c). Also, patients hospitalized after implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) shock need to be monitored.3,6

Patients with a paced rhythm who do not meet the above criteria do not require routine telemetric monitoring (risk class III-c).7

TELEMETRY IS OVERUSED

Off-site telemetry monitoring can identify significant arrhythmias during hospitalization. It also saves time on nursing staff to focus on bedside patient care. However, its convenience can lower the threshold for ordering it. This can lead to overuse with a major impact on healthcare costs.

Routine use of cardiac telemetry is associated with increased hospitalization costs with little benefit.8 The use of off-site services for continuous monitoring can activate many alarms throughout the day, triggering unnecessary workups and leading to densensitization to alarms (“alarm fatigue”).9

Despite the precise indications outlined in the AHA updated practice standards for inpatient electrocardiographic monitoring,10 telemetry use is expanding to non-ICU units without evidence of benefit,8 and this overuse can result in harmful clinical outcomes and a financial burden. Telemetry monitoring of low-risk patients can cause delays in emergency department and ICU admissions and transfers8,11 of patients who may be sicker and need intensive care.

In a prospective observational study,12 only 11 (6%) of 182 patients admitted to a general medical floor met AHA class I criteria for telemetry; very few patients developed a significant telemetry event such as atrial fibrillation or flutter that necessitated a change in management. Most overprescribers of telemetry monitoring reason that it will catch arrhythmias early.12 In fact, in a study of patients in a cardiac unit, telemetry detected just 50% of in-house cardiac arrest cases, with a potential survival benefit of only 0.02%.13

Another study showed that only 0.01% of all telemetry alarms represented a real emergency. Only 37.2% of emergency alarms were classified as clinically important, and only 48.3% of these led to a change in management within 1 hour.14

Moreover, in a report of trauma patients with abnormal results on ECG at the time of admission, telemetry had negligible clinical benefit.15 And in a study of 414 patients, only 4% of those admitted with chest pain and normal initial ECG had cardiac interventions.16

Another study8 showed that hospital intervention to restrict the use of telemetry guided by AHA recommendations resulted in a 43% reduction in telemetry orders, a 47% reduction in telemetry duration, and a 70% reduction in the mean daily number of patients monitored, with no changes in hospital census or rates of code blue, death, or rapid response team activation.8

The financial cost can be seen in the backup of patients in the emergency department. A study showed that 91% of patients being admitted for chest pain were delayed by more than 3 hours while waiting for monitored beds. This translated into an annual cost of $168,300 to the hospital.17 Adherence to guidelines for appropriate use of telemetry can significantly decrease costs. Applying a simple algorithm for telemetry use was shown8 to decrease daily non-ICU cardiac telemetry costs from $18,971 to $5,772.

CURRENT GUIDELINES ARE LIMITED

The current American College of Cardiology and AHA guidelines are based mostly on expert opinion rather than randomized clinical trials, while most telemetry trials have been performed on patients with a cardiac or possible cardiac diagnosis.3 Current guidelines need to be updated, and more studies are needed to specify the optimal duration of cardiac monitoring in indicated cases. Many noncardiac conditions raise a legitimate concern of dysrhythmia, an indication for cardiac monitoring, but precise recommendations for telemetry for such conditions are lacking.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Raising awareness of the clinical and financial burdens associated with unwise telemetry utilization is critical. We suggest use of a pop-up notification in the electronic medical record to remind the provider of the existing telemetry order and to specify the duration of telemetry monitoring when placing the initial order. The goal is to identify patients in true need of a telemetry bed, to decrease unnecessary testing, and to reduce hospitalization costs.

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991; 18(6):1431–1433. pmid:1939942

- Goldman L, Cook EF, Johnson PA, Brand DA, Rouan GW, Lee TH. Prediction of the need for intensive care in patients who come to emergency departments with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med 1996; 334(23):1498–1504. doi:10.1056/NEJM199606063342303

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al; American Heart Association; Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation 2004;110(17):2721–2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59

- Ustrell X, Pellise A. Cardiac workup of ischemic stroke. Curr Cardiol Rev 2010; 6(3):175-183. doi:10.2174/157340310791658721

- Olson JA, Fouts AM, Padanilam BJ, Prystowsky EN. Utility of mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry for the diagnosis of palpitations, presyncope, syncope, and the assessment of therapy efficacy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2007; 18(5):473–477. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00779.x

- Chen EH, Hollander JE. When do patients need admission to a telemetry bed? J Emerg Med 2007; 33(1):53–60. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.01.017

- Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, et al; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Update to practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 136(19):e273–e344. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000527

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174(11):1852–1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491

- Cantillon DJ, Loy M, Burkle A, et al. Association between off-site central monitoring using standardized cardiac telemetry and clinical outcomes among non–critically ill patients. JAMA 2016; 316(5):519–524. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.10258

- Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, et al. Update to practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 136(19):e273–e344. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000527

- Atzema C, Schull MJ, Borgundvaag B, Slaughter GR, Lee CK. ALARMED: adverse events in low-risk patients with chest pain receiving continuous electrocardiographic monitoring in the emergency department. A pilot study. Am J Emerg Med 2006; 24(1):62–67. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.015

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(17):1349–1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163

- Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and cardiac arrest outcomes in 8,932 telemetry ward patients. Acad Emerg Med 2000; 7(6):647–652. pmid:10905643

- Kansara P, Jackson K, Dressler R, et al. Potential of missing life-threatening arrhythmias after limiting the use of cardiac telemetry. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175(8):1416–1418. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2387

- Nagy KK, Krosner SM, Roberts RR, Joseph KT, Smith RF, Barrett J. Determining which patients require evaluation for blunt cardiac injury following blunt chest trauma. World J Surg 2001; 25(1):108–111. pmid:11213149

- Snider A, Papaleo M, Beldner S, et al. Is telemetry monitoring necessary in low-risk suspected acute chest pain syndromes? Chest 2002; 122(2):517–523. pmid:12171825

- Bayley MD, Schwartz JS, Shofer FS, et al. The financial burden of emergency department congestion and hospital crowding for chest pain patients awaiting admission. Ann Emerg Med 2005; 45(2):110–117. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.09.010

- Recommended guidelines for in-hospital cardiac monitoring of adults for detection of arrhythmia. Emergency Cardiac Care Committee members. J Am Coll Cardiol 1991; 18(6):1431–1433. pmid:1939942

- Goldman L, Cook EF, Johnson PA, Brand DA, Rouan GW, Lee TH. Prediction of the need for intensive care in patients who come to emergency departments with acute chest pain. N Engl J Med 1996; 334(23):1498–1504. doi:10.1056/NEJM199606063342303

- Drew BJ, Califf RM, Funk M, et al; American Heart Association; Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: an American Heart Association scientific statement from the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Clinical Cardiology, and Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the International Society of Computerized Electrocardiology and the American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. Circulation 2004;110(17):2721–2746. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000145144.56673.59

- Ustrell X, Pellise A. Cardiac workup of ischemic stroke. Curr Cardiol Rev 2010; 6(3):175-183. doi:10.2174/157340310791658721

- Olson JA, Fouts AM, Padanilam BJ, Prystowsky EN. Utility of mobile cardiac outpatient telemetry for the diagnosis of palpitations, presyncope, syncope, and the assessment of therapy efficacy. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2007; 18(5):473–477. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8167.2007.00779.x

- Chen EH, Hollander JE. When do patients need admission to a telemetry bed? J Emerg Med 2007; 33(1):53–60. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.01.017

- Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, et al; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing; Council on Clinical Cardiology; and Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Update to practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 136(19):e273–e344. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000527

- Dressler R, Dryer MM, Coletti C, Mahoney D, Doorey AJ. Altering overuse of cardiac telemetry in non-intensive care unit settings by hardwiring the use of American Heart Association guidelines. JAMA Intern Med 2014; 174(11):1852–1854. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.4491

- Cantillon DJ, Loy M, Burkle A, et al. Association between off-site central monitoring using standardized cardiac telemetry and clinical outcomes among non–critically ill patients. JAMA 2016; 316(5):519–524. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.10258

- Sandau KE, Funk M, Auerbach A, et al. Update to practice standards for electrocardiographic monitoring in hospital settings: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2017; 136(19):e273–e344. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000527

- Atzema C, Schull MJ, Borgundvaag B, Slaughter GR, Lee CK. ALARMED: adverse events in low-risk patients with chest pain receiving continuous electrocardiographic monitoring in the emergency department. A pilot study. Am J Emerg Med 2006; 24(1):62–67. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2005.05.015

- Najafi N, Auerbach A. Use and outcomes of telemetry monitoring on a medicine service. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172(17):1349–1350. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3163

- Schull MJ, Redelmeier DA. Continuous electrocardiographic monitoring and cardiac arrest outcomes in 8,932 telemetry ward patients. Acad Emerg Med 2000; 7(6):647–652. pmid:10905643

- Kansara P, Jackson K, Dressler R, et al. Potential of missing life-threatening arrhythmias after limiting the use of cardiac telemetry. JAMA Intern Med 2015; 175(8):1416–1418. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2387

- Nagy KK, Krosner SM, Roberts RR, Joseph KT, Smith RF, Barrett J. Determining which patients require evaluation for blunt cardiac injury following blunt chest trauma. World J Surg 2001; 25(1):108–111. pmid:11213149

- Snider A, Papaleo M, Beldner S, et al. Is telemetry monitoring necessary in low-risk suspected acute chest pain syndromes? Chest 2002; 122(2):517–523. pmid:12171825

- Bayley MD, Schwartz JS, Shofer FS, et al. The financial burden of emergency department congestion and hospital crowding for chest pain patients awaiting admission. Ann Emerg Med 2005; 45(2):110–117. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.09.010