User login

Choosing the Best Formalin-Resistant Ink for Biopsy Specimen Labeling

Choosing the Best Formalin-Resistant Ink for Biopsy Specimen Labeling

Practice Gap

Many dermatology practices utilize pens and markers to label biopsy specimen containers, but the ink may have variable susceptibility to fading and smearing when exposed to moisture before processing. Specimen containers often are placed in plastic bags for transport. If formalin accidentally spills into the bag during this time, the labels may be exposed to moisture for hours, overnight, or even over a weekend. Effective labeling with formalin-resistant ink is crucial for maintaining the clarity of anatomic location and planning treatment, especially when multiple samples are obtained.

The Technique

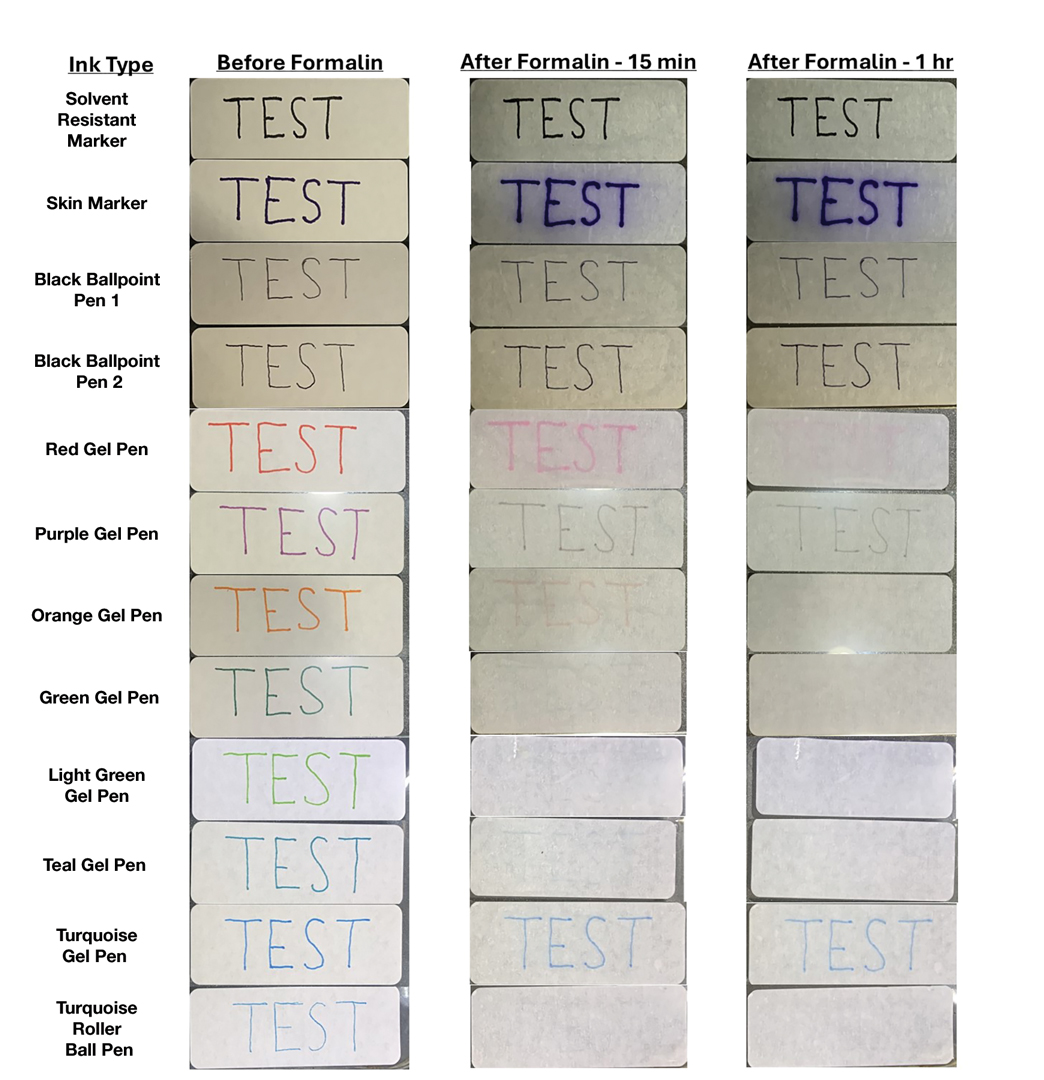

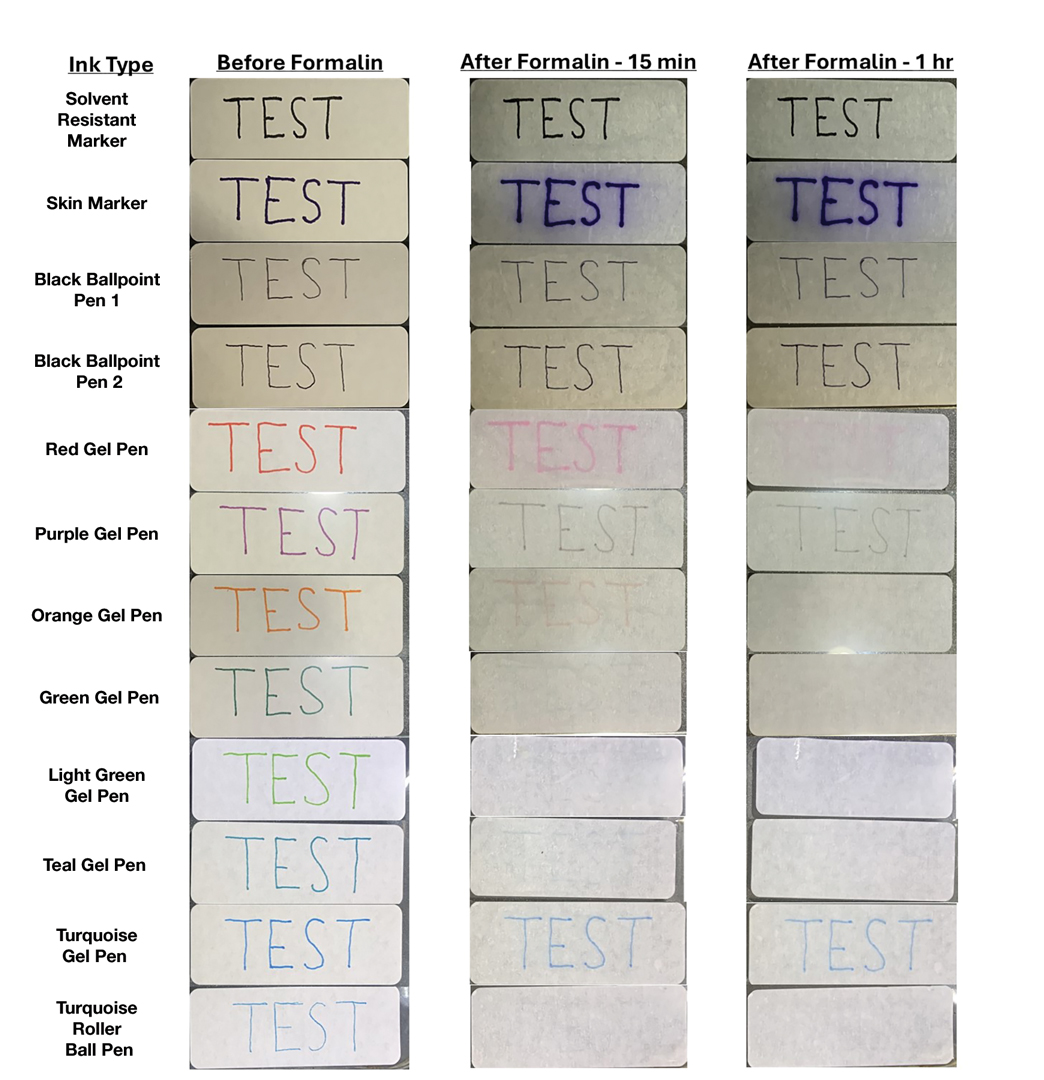

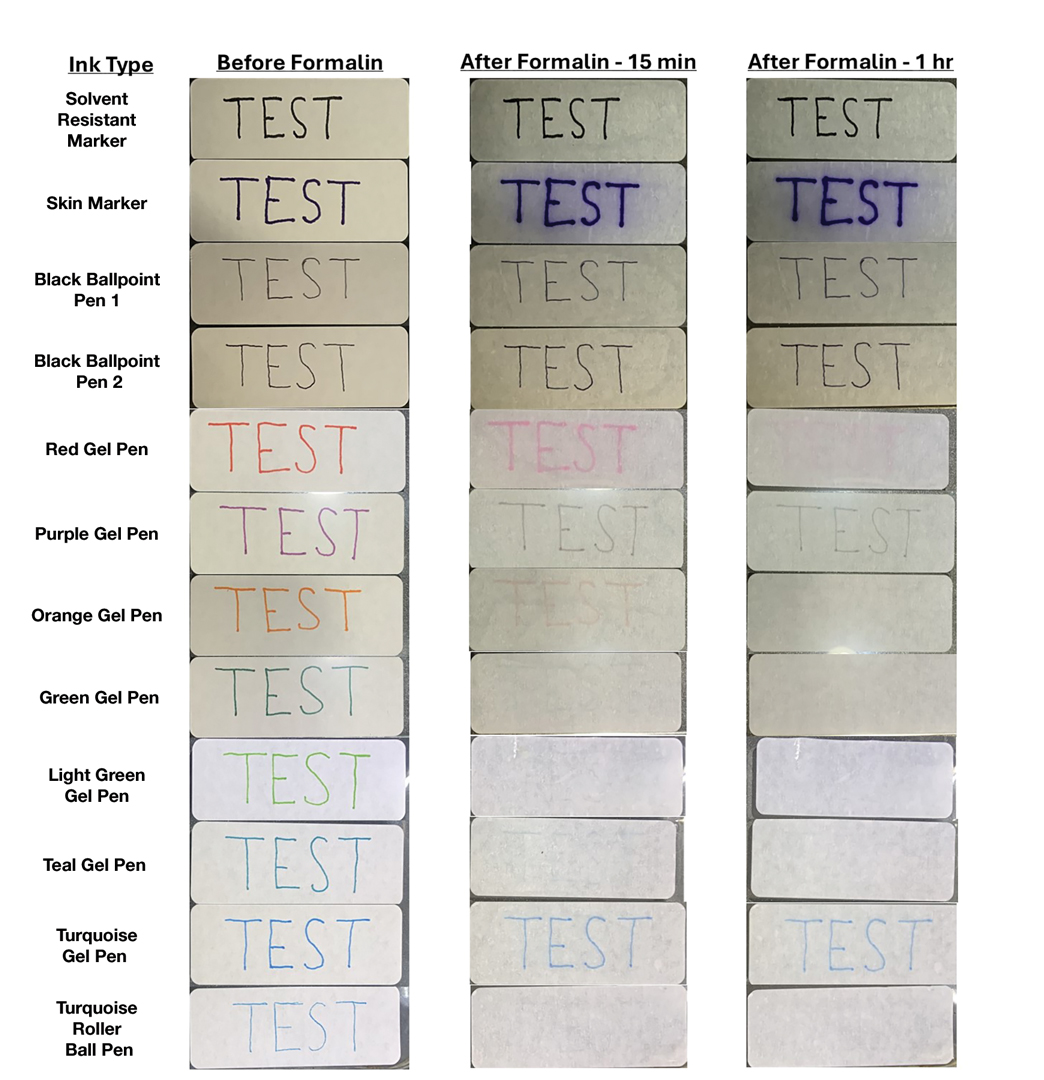

We tested 12 pens and markers commonly used when labeling specimen containers to determine their susceptibility to fading due to accidental formalin exposure (Figure). Various inks were allowed to dry on sample specimen labels for 5 minutes before a thin layer of 10% buffered formalin was evenly distributed over the dried ink. Photographs of the labels were taken at baseline as well as 15 minutes, 1 hour, 3 hours, and 24 hours after formalin exposure.

Fading was observed in both the skin marker and gel panes after 15 minutes and peaked after 1 hour. Gel pens were most susceptible to fading on exposure to formalin, and the level of fading varied by ink color, with certain colors disappearing almost entirely (Figure). The solvent-resistant marker had a robust defense to formalin, as did both ballpoint pens.

Practice Implications

Given our findings, dermatology practices should avoid using gel pens to label specimen containers. Solvent-resistant markers performed as expected; however, ballpoint pens appeared to withstand formalin exposure to a similar degree and often are more readily available. Labeling biopsy specimens with an appropriate ink ensures that each sample is clearly identified with the appropriate anatomic location and any other relevant patient information.

Practice Gap

Many dermatology practices utilize pens and markers to label biopsy specimen containers, but the ink may have variable susceptibility to fading and smearing when exposed to moisture before processing. Specimen containers often are placed in plastic bags for transport. If formalin accidentally spills into the bag during this time, the labels may be exposed to moisture for hours, overnight, or even over a weekend. Effective labeling with formalin-resistant ink is crucial for maintaining the clarity of anatomic location and planning treatment, especially when multiple samples are obtained.

The Technique

We tested 12 pens and markers commonly used when labeling specimen containers to determine their susceptibility to fading due to accidental formalin exposure (Figure). Various inks were allowed to dry on sample specimen labels for 5 minutes before a thin layer of 10% buffered formalin was evenly distributed over the dried ink. Photographs of the labels were taken at baseline as well as 15 minutes, 1 hour, 3 hours, and 24 hours after formalin exposure.

Fading was observed in both the skin marker and gel panes after 15 minutes and peaked after 1 hour. Gel pens were most susceptible to fading on exposure to formalin, and the level of fading varied by ink color, with certain colors disappearing almost entirely (Figure). The solvent-resistant marker had a robust defense to formalin, as did both ballpoint pens.

Practice Implications

Given our findings, dermatology practices should avoid using gel pens to label specimen containers. Solvent-resistant markers performed as expected; however, ballpoint pens appeared to withstand formalin exposure to a similar degree and often are more readily available. Labeling biopsy specimens with an appropriate ink ensures that each sample is clearly identified with the appropriate anatomic location and any other relevant patient information.

Practice Gap

Many dermatology practices utilize pens and markers to label biopsy specimen containers, but the ink may have variable susceptibility to fading and smearing when exposed to moisture before processing. Specimen containers often are placed in plastic bags for transport. If formalin accidentally spills into the bag during this time, the labels may be exposed to moisture for hours, overnight, or even over a weekend. Effective labeling with formalin-resistant ink is crucial for maintaining the clarity of anatomic location and planning treatment, especially when multiple samples are obtained.

The Technique

We tested 12 pens and markers commonly used when labeling specimen containers to determine their susceptibility to fading due to accidental formalin exposure (Figure). Various inks were allowed to dry on sample specimen labels for 5 minutes before a thin layer of 10% buffered formalin was evenly distributed over the dried ink. Photographs of the labels were taken at baseline as well as 15 minutes, 1 hour, 3 hours, and 24 hours after formalin exposure.

Fading was observed in both the skin marker and gel panes after 15 minutes and peaked after 1 hour. Gel pens were most susceptible to fading on exposure to formalin, and the level of fading varied by ink color, with certain colors disappearing almost entirely (Figure). The solvent-resistant marker had a robust defense to formalin, as did both ballpoint pens.

Practice Implications

Given our findings, dermatology practices should avoid using gel pens to label specimen containers. Solvent-resistant markers performed as expected; however, ballpoint pens appeared to withstand formalin exposure to a similar degree and often are more readily available. Labeling biopsy specimens with an appropriate ink ensures that each sample is clearly identified with the appropriate anatomic location and any other relevant patient information.

Choosing the Best Formalin-Resistant Ink for Biopsy Specimen Labeling

Choosing the Best Formalin-Resistant Ink for Biopsy Specimen Labeling

Pursuit of a Research Year or Dual Degree by Dermatology Residency Applicants: A Cross-Sectional Study

To the Editor:

Securing a dermatology residency position is extraordinarily competitive. The match rate for US allopathic seniors for dermatology is 84.7%, among the lowest of all medical specialties. Matched dermatology applicants boast a mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score of 248, the second highest of all specialties.1 To gain an edge, applicants are faced with decisions regarding pursuit of dedicated research time and additional professional degrees.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine how many dermatology residency applicants pursue additional years of training and how this decision relates to USMLE scores and other metrics. This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Using Electronic Residency Application Service applicant data, all applicants to the University of Michigan Medical School (Ann Arbor, Michigan) dermatology residency program for the 2018-2019 application cycle were included.

Analysis of variance was performed to determine differences in mean USMLE Step 1 scores, Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores, and number of research experiences (eg, presentations, publications) between groups. A 2-tailed z test of independent samples was performed for individual pairwise subgroup analyses.

There were 608 (377 female, 231 male; mean age, 27.9 years) applicants from 199 different medical schools; 550 graduated with an MD degree, 40 with a DO degree, and 18 were international medical graduates (IMGs)(eg, MBBS, MBBCh, BAO, MBChB). One hundred eighty-four applicants (30.2%) pursued either a second professional degree or a dedicated research period lasting at least 12 months. Twenty-eight applicants (4.6%) obtained a master’s degree, 21 (3.5%) obtained a doctorate, and 135 (22.2%) pursued dedicated research.

Of the 40 DO applicants, 1 (2.5%) pursued dedicated research time; 0 (zero) completed a dual degree. None (zero) of the 18 IMGs pursued a dual degree or dedicated research time. When the scores of applicants who pursued additional training and the scores of applicants who did not were compared, neither mean USMLE Step 1 scores nor mean USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores were statistically different (P=.31 and P=.44, respectively). Applicants who completed medical school in 4 years had fewer research experiences (mean [SD] experiences, 13.9 [13.2]) than students with a master’s degree (18.5 [8.4]), doctorate (24.5 [17.5]), or dedicated research time (23.9 [14.9])(P<.001).

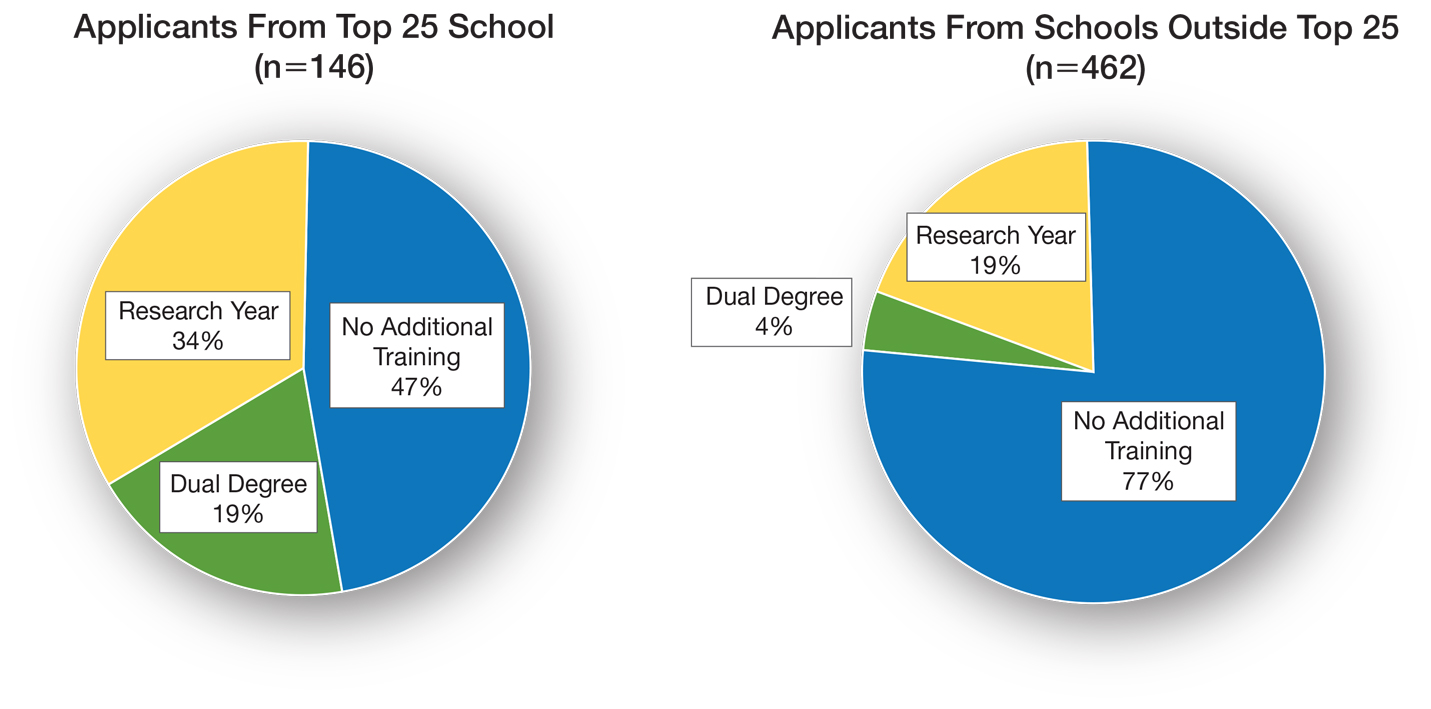

Utilizing US News & World Report rankings (2019 Best Medical Schools: Research), we determined that 146 applicants (24.0%) attended a top 25 medical school in 2019.2 Of those 146 applicants, 77 (52.7%) pursued additional training through dedicated research or a second professional degree. Only 107 of the 462 applicants (23.2%) from medical schools that were not in the top 25 as determined by the US News & World Report pursued additional training (P<.0001)(Figure).

There is sentiment among applicants that a weaker dermatology residency application can be bolstered through a dedicated research year or a second professional degree. Whether this additional training has an impact on an applicant’s chances of matching is unclear and requires further investigation. Our data showed that applicants from the top 25 medical schools were more likely to pursue additional training than graduates at other institutions. These highly ranked academic institutions might encourage students to pursue a dual degree or research fellowship. In addition, year-long research opportunities might be more available through top medical schools; these schools might be more likely to offer dual-degree programs or provide funding to support student research opportunities.

It is important to comment on the potential importance of funding to support research years; the unpaid nature of many research fellowships in dermatology tends to favor applicants from a higher socioeconomic background. In that respect, the pervasive trend of encouraging research years in dermatology might widen already apparent disparities in our field, likely impacting underrepresented minorities disproportionately.3 Importantly, students with an MD degree represent nearly all applicants who completed a dual degree or dedicated research time. This might be due to fewer opportunities available to IMGs and DO students or secondary to incentivization by MD institutions.

Our data also suggest that students who pursue additional training have academic achievement metrics similar to those who do not. Additional training might increase medical students’ debt burden, thus catering to more affluent applicants, which, in turn, might have an impact on the diversity of the dermatology residency applicant pool.

Our data come from a single institution during a single application cycle, comprising 608 applicants. Nationwide, there were 701 dermatology residency applicants for the 2018-2019 application cycle; our pool therefore represents most (86.7%) but not all applicants.

We decided to use the US News & World Report 2019 rankings to identify top medical schools. Although this ranking system is imperfect and inherently subjective, it is widely utilized by prospective applicants and administrative faculty; we deemed it the best ranking that we could utilize to identify top medical schools. Because the University of Michigan Medical School was in the top 25 of Best Medical Schools: Research, according to the US News & World Report 2019 rankings, our applicant pool might be skewed to applicants interested in a more academic, research-focused residency program.

Our study revealed that 30% (n=184) of dermatology residency applicants pursued a second professional degree or dedicated research time. There was no difference in UMLE Step 1 and Step 2 scores for those who pursued additional training compared to those who did not.

- Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. 2nd ed. National Residency Matching Program. Published July 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2020_MD-Senior_final.pdf

- 2019 Best Medical Schools: Research. US News & World Report; 2019.

- Oussedik E. Important considerations for diversity in the selection of dermatology applicants. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:948-949. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1814

To the Editor:

Securing a dermatology residency position is extraordinarily competitive. The match rate for US allopathic seniors for dermatology is 84.7%, among the lowest of all medical specialties. Matched dermatology applicants boast a mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score of 248, the second highest of all specialties.1 To gain an edge, applicants are faced with decisions regarding pursuit of dedicated research time and additional professional degrees.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine how many dermatology residency applicants pursue additional years of training and how this decision relates to USMLE scores and other metrics. This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Using Electronic Residency Application Service applicant data, all applicants to the University of Michigan Medical School (Ann Arbor, Michigan) dermatology residency program for the 2018-2019 application cycle were included.

Analysis of variance was performed to determine differences in mean USMLE Step 1 scores, Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores, and number of research experiences (eg, presentations, publications) between groups. A 2-tailed z test of independent samples was performed for individual pairwise subgroup analyses.

There were 608 (377 female, 231 male; mean age, 27.9 years) applicants from 199 different medical schools; 550 graduated with an MD degree, 40 with a DO degree, and 18 were international medical graduates (IMGs)(eg, MBBS, MBBCh, BAO, MBChB). One hundred eighty-four applicants (30.2%) pursued either a second professional degree or a dedicated research period lasting at least 12 months. Twenty-eight applicants (4.6%) obtained a master’s degree, 21 (3.5%) obtained a doctorate, and 135 (22.2%) pursued dedicated research.

Of the 40 DO applicants, 1 (2.5%) pursued dedicated research time; 0 (zero) completed a dual degree. None (zero) of the 18 IMGs pursued a dual degree or dedicated research time. When the scores of applicants who pursued additional training and the scores of applicants who did not were compared, neither mean USMLE Step 1 scores nor mean USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores were statistically different (P=.31 and P=.44, respectively). Applicants who completed medical school in 4 years had fewer research experiences (mean [SD] experiences, 13.9 [13.2]) than students with a master’s degree (18.5 [8.4]), doctorate (24.5 [17.5]), or dedicated research time (23.9 [14.9])(P<.001).

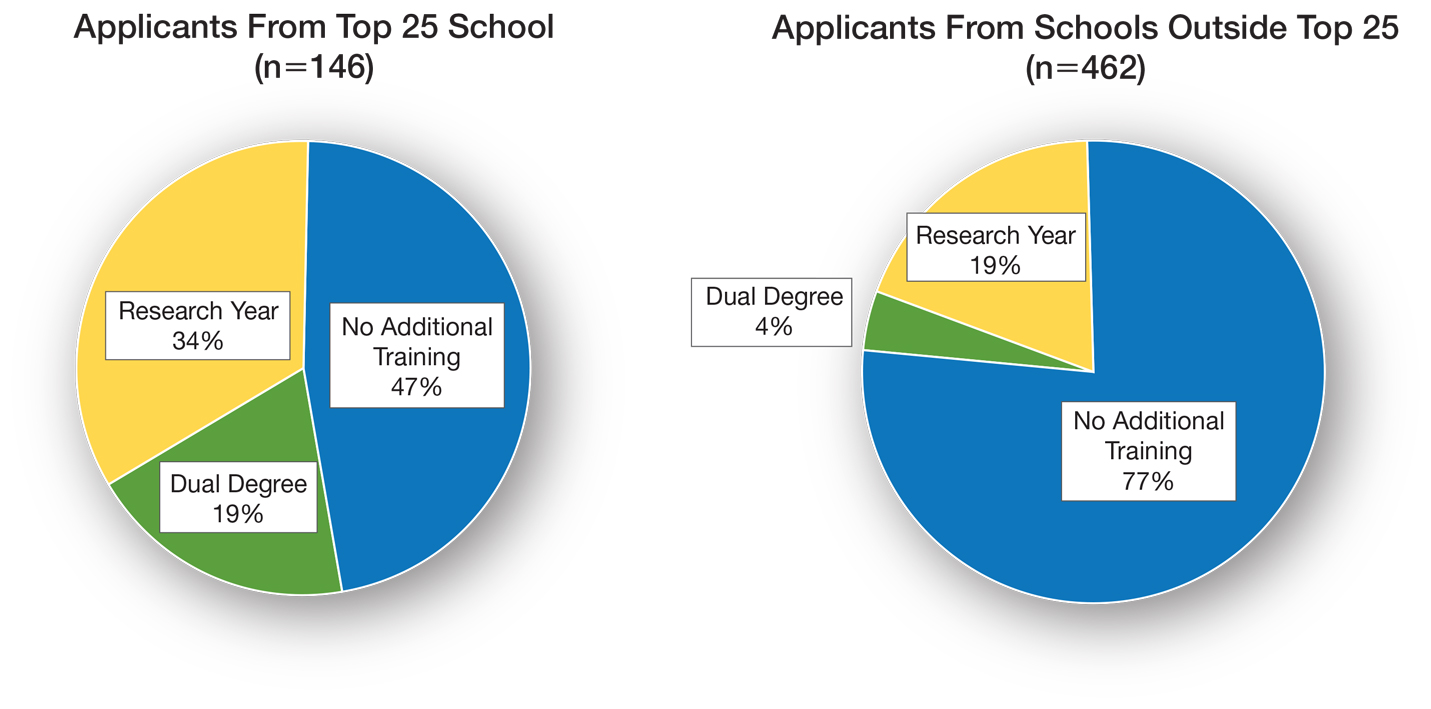

Utilizing US News & World Report rankings (2019 Best Medical Schools: Research), we determined that 146 applicants (24.0%) attended a top 25 medical school in 2019.2 Of those 146 applicants, 77 (52.7%) pursued additional training through dedicated research or a second professional degree. Only 107 of the 462 applicants (23.2%) from medical schools that were not in the top 25 as determined by the US News & World Report pursued additional training (P<.0001)(Figure).

There is sentiment among applicants that a weaker dermatology residency application can be bolstered through a dedicated research year or a second professional degree. Whether this additional training has an impact on an applicant’s chances of matching is unclear and requires further investigation. Our data showed that applicants from the top 25 medical schools were more likely to pursue additional training than graduates at other institutions. These highly ranked academic institutions might encourage students to pursue a dual degree or research fellowship. In addition, year-long research opportunities might be more available through top medical schools; these schools might be more likely to offer dual-degree programs or provide funding to support student research opportunities.

It is important to comment on the potential importance of funding to support research years; the unpaid nature of many research fellowships in dermatology tends to favor applicants from a higher socioeconomic background. In that respect, the pervasive trend of encouraging research years in dermatology might widen already apparent disparities in our field, likely impacting underrepresented minorities disproportionately.3 Importantly, students with an MD degree represent nearly all applicants who completed a dual degree or dedicated research time. This might be due to fewer opportunities available to IMGs and DO students or secondary to incentivization by MD institutions.

Our data also suggest that students who pursue additional training have academic achievement metrics similar to those who do not. Additional training might increase medical students’ debt burden, thus catering to more affluent applicants, which, in turn, might have an impact on the diversity of the dermatology residency applicant pool.

Our data come from a single institution during a single application cycle, comprising 608 applicants. Nationwide, there were 701 dermatology residency applicants for the 2018-2019 application cycle; our pool therefore represents most (86.7%) but not all applicants.

We decided to use the US News & World Report 2019 rankings to identify top medical schools. Although this ranking system is imperfect and inherently subjective, it is widely utilized by prospective applicants and administrative faculty; we deemed it the best ranking that we could utilize to identify top medical schools. Because the University of Michigan Medical School was in the top 25 of Best Medical Schools: Research, according to the US News & World Report 2019 rankings, our applicant pool might be skewed to applicants interested in a more academic, research-focused residency program.

Our study revealed that 30% (n=184) of dermatology residency applicants pursued a second professional degree or dedicated research time. There was no difference in UMLE Step 1 and Step 2 scores for those who pursued additional training compared to those who did not.

To the Editor:

Securing a dermatology residency position is extraordinarily competitive. The match rate for US allopathic seniors for dermatology is 84.7%, among the lowest of all medical specialties. Matched dermatology applicants boast a mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score of 248, the second highest of all specialties.1 To gain an edge, applicants are faced with decisions regarding pursuit of dedicated research time and additional professional degrees.

We conducted a cross-sectional study to determine how many dermatology residency applicants pursue additional years of training and how this decision relates to USMLE scores and other metrics. This study was approved by the University of Michigan institutional review board. Using Electronic Residency Application Service applicant data, all applicants to the University of Michigan Medical School (Ann Arbor, Michigan) dermatology residency program for the 2018-2019 application cycle were included.

Analysis of variance was performed to determine differences in mean USMLE Step 1 scores, Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores, and number of research experiences (eg, presentations, publications) between groups. A 2-tailed z test of independent samples was performed for individual pairwise subgroup analyses.

There were 608 (377 female, 231 male; mean age, 27.9 years) applicants from 199 different medical schools; 550 graduated with an MD degree, 40 with a DO degree, and 18 were international medical graduates (IMGs)(eg, MBBS, MBBCh, BAO, MBChB). One hundred eighty-four applicants (30.2%) pursued either a second professional degree or a dedicated research period lasting at least 12 months. Twenty-eight applicants (4.6%) obtained a master’s degree, 21 (3.5%) obtained a doctorate, and 135 (22.2%) pursued dedicated research.

Of the 40 DO applicants, 1 (2.5%) pursued dedicated research time; 0 (zero) completed a dual degree. None (zero) of the 18 IMGs pursued a dual degree or dedicated research time. When the scores of applicants who pursued additional training and the scores of applicants who did not were compared, neither mean USMLE Step 1 scores nor mean USMLE Step 2 Clinical Knowledge scores were statistically different (P=.31 and P=.44, respectively). Applicants who completed medical school in 4 years had fewer research experiences (mean [SD] experiences, 13.9 [13.2]) than students with a master’s degree (18.5 [8.4]), doctorate (24.5 [17.5]), or dedicated research time (23.9 [14.9])(P<.001).

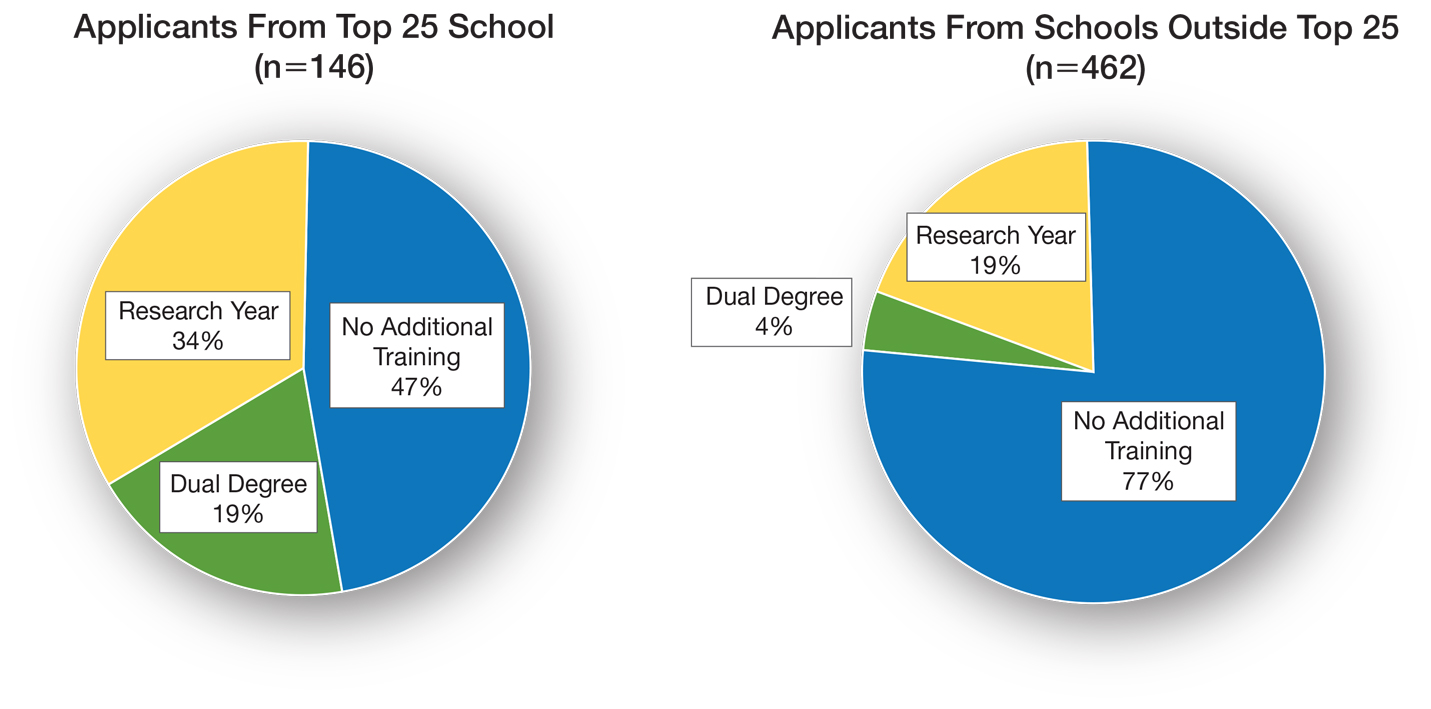

Utilizing US News & World Report rankings (2019 Best Medical Schools: Research), we determined that 146 applicants (24.0%) attended a top 25 medical school in 2019.2 Of those 146 applicants, 77 (52.7%) pursued additional training through dedicated research or a second professional degree. Only 107 of the 462 applicants (23.2%) from medical schools that were not in the top 25 as determined by the US News & World Report pursued additional training (P<.0001)(Figure).

There is sentiment among applicants that a weaker dermatology residency application can be bolstered through a dedicated research year or a second professional degree. Whether this additional training has an impact on an applicant’s chances of matching is unclear and requires further investigation. Our data showed that applicants from the top 25 medical schools were more likely to pursue additional training than graduates at other institutions. These highly ranked academic institutions might encourage students to pursue a dual degree or research fellowship. In addition, year-long research opportunities might be more available through top medical schools; these schools might be more likely to offer dual-degree programs or provide funding to support student research opportunities.

It is important to comment on the potential importance of funding to support research years; the unpaid nature of many research fellowships in dermatology tends to favor applicants from a higher socioeconomic background. In that respect, the pervasive trend of encouraging research years in dermatology might widen already apparent disparities in our field, likely impacting underrepresented minorities disproportionately.3 Importantly, students with an MD degree represent nearly all applicants who completed a dual degree or dedicated research time. This might be due to fewer opportunities available to IMGs and DO students or secondary to incentivization by MD institutions.

Our data also suggest that students who pursue additional training have academic achievement metrics similar to those who do not. Additional training might increase medical students’ debt burden, thus catering to more affluent applicants, which, in turn, might have an impact on the diversity of the dermatology residency applicant pool.

Our data come from a single institution during a single application cycle, comprising 608 applicants. Nationwide, there were 701 dermatology residency applicants for the 2018-2019 application cycle; our pool therefore represents most (86.7%) but not all applicants.

We decided to use the US News & World Report 2019 rankings to identify top medical schools. Although this ranking system is imperfect and inherently subjective, it is widely utilized by prospective applicants and administrative faculty; we deemed it the best ranking that we could utilize to identify top medical schools. Because the University of Michigan Medical School was in the top 25 of Best Medical Schools: Research, according to the US News & World Report 2019 rankings, our applicant pool might be skewed to applicants interested in a more academic, research-focused residency program.

Our study revealed that 30% (n=184) of dermatology residency applicants pursued a second professional degree or dedicated research time. There was no difference in UMLE Step 1 and Step 2 scores for those who pursued additional training compared to those who did not.

- Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. 2nd ed. National Residency Matching Program. Published July 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2020_MD-Senior_final.pdf

- 2019 Best Medical Schools: Research. US News & World Report; 2019.

- Oussedik E. Important considerations for diversity in the selection of dermatology applicants. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:948-949. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1814

- Charting outcomes in the match: U.S. allopathic seniors. 2nd ed. National Residency Matching Program. Published July 2020. Accessed January 3, 2022. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Charting-Outcomes-in-the-Match-2020_MD-Senior_final.pdf

- 2019 Best Medical Schools: Research. US News & World Report; 2019.

- Oussedik E. Important considerations for diversity in the selection of dermatology applicants. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:948-949. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.1814

PRACTICE POINTS

- In our study of dermatology residency applicants (N11=608), 30% pursued a second professional degree or dedicated research time.

- US Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 and Step 2 scores did not differ among applicants who pursued additional training and those who did not.

- Additional training might increase medical students’ debt burden, thus catering to more affluent applicants and reducing the diversity of applicant and resident pools.