User login

Waterproof Cast Protector Keeps Wound Dressing Intact Following Nail Surgery

Waterproof Cast Protector Keeps Wound Dressing Intact Following Nail Surgery

Practice Gap

Postoperative care after nail biopsies can be challenging for patients due to the bulky dressing that must remain in place for 48 hours.1 The dressing can restrict daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, and other household tasks. A common solution is to cover the hand with a plastic bag secured with tape during water-related activities, but efficacy is variable. In one study, 23 participants tested this method by holding a paper towel with their hand covered by a plastic bag and measuring the weight of the paper towel before and after submersion of the hand in water.2 Any saturation of the paper towel was defined as failure; the failure rate was 52.2% (12/23) with motion (rotating the arm at the elbow for 30 seconds clockwise, counterclockwise, and left to right) and 60.9% (14/23) without motion. There was an average of 5.50 g of moisture accumulation without motion and 4.51 g with motion, with failure occurring most often immediately following submersion of the hand. Furthermore, the plastic bag with tape method was rated poorly by all 23 participants based on efficacy and comfort.2

In the same study, participants also reported that removal of the adhesive tape was unpleasant and irritating,2 which suggests these same complaints may apply to use of a waterproof bandage, another potential option for coverage of the wound dressing. As an alternative, we propose the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector following nail surgery that allows patients to continue their regular activities while keeping the dressing dry and intact to allow for optimal wound healing.

The Technique

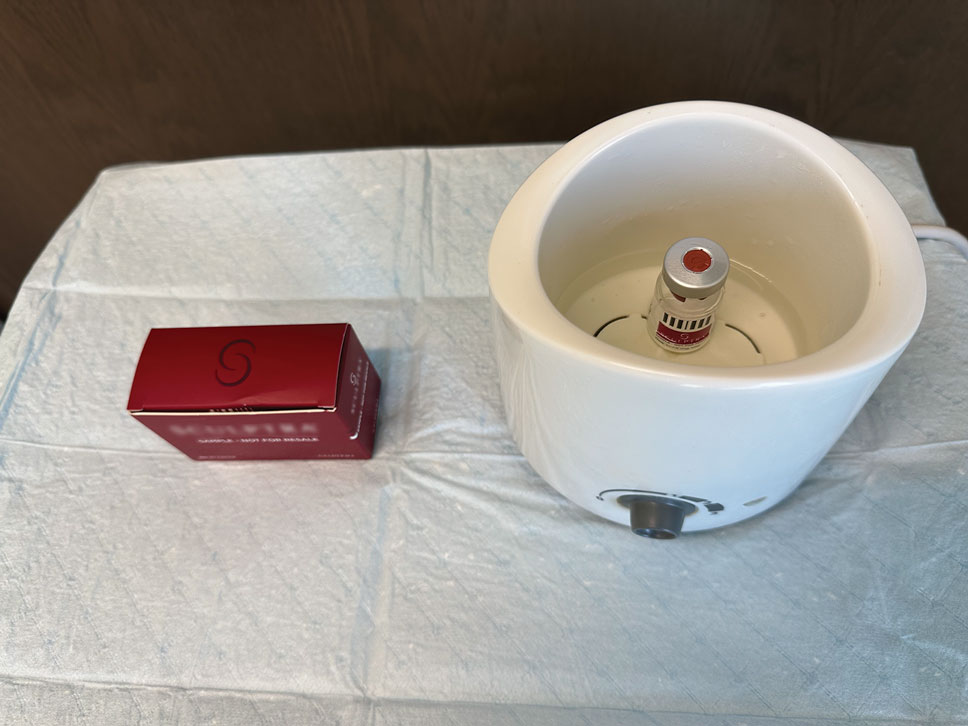

Our technique involves the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector that is sealed with a thick rubber cuff, allowing patients to perform regular daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, cleaning, and doing laundry without the wound dressing underneath becoming wet (Figure). Cast protectors made of flexible latex-free plastic are readily available and can slide on and off the arm as needed. We recommend that patients purchase the cast protector prior to undergoing surgery. There are options to fit most adults, with the opening generally accommodating arm diameters of 2 to 7 inches. These reusable cast protectors are available via popular online retailers and typically cost patients $10 to $15.

Practice Implications

In our experience, using a reusable waterproof cast protector following nail surgery is effective at keeping wound dressings dry and provides a practical solution for bathing and other activities involving water exposure. It is durable and easy to use, especially when compared to a plastic bag and waterproof tape. However, some patients find the waterproof seal uncomfortable, especially when worn for extended periods of time. According to online product feedback, limitations of the cast protector include potential leakage with prolonged immersion in water, swimming, or high-pressure water exposure. The cast protector should not be worn for more than 30 minutes, as it can restrict blood flow, and condensation from prolonged use may dampen the dressing. While we have not encountered allergic contact dermatitis associated with the use of cast protectors for this purpose in our practice, patients should be cautioned of this potential risk. While these cast protectors generally can accommodate a range of arm diameters, they may not fit all hand sizes or shapes and may reduce dexterity for motor tasks. Additionally, the patient must purchase the protector ahead of surgery.

Our technique involving the use of a waterproof arm cast protector is an affordable solution that allows patients to keep their wound dressing dry while continuing to perform regular daily activities. The cast protector also can be used following other dermatologic procedures (eg, biopsy, Mohs micrographic surgery) that involve the hand and lower arm when waterproof protection may be necessary.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. How we do it: pressure-padded dressing with self-adherent elastic wrap for wound care after nail surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:442–444. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002371

- Kwan S, Santoro A, Cheesman Q, et al. Efficacy of waterproof cast protectors and their ability to keep casts dry. J Hand Surg Am. 2023;48:803–809. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.05.006

Practice Gap

Postoperative care after nail biopsies can be challenging for patients due to the bulky dressing that must remain in place for 48 hours.1 The dressing can restrict daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, and other household tasks. A common solution is to cover the hand with a plastic bag secured with tape during water-related activities, but efficacy is variable. In one study, 23 participants tested this method by holding a paper towel with their hand covered by a plastic bag and measuring the weight of the paper towel before and after submersion of the hand in water.2 Any saturation of the paper towel was defined as failure; the failure rate was 52.2% (12/23) with motion (rotating the arm at the elbow for 30 seconds clockwise, counterclockwise, and left to right) and 60.9% (14/23) without motion. There was an average of 5.50 g of moisture accumulation without motion and 4.51 g with motion, with failure occurring most often immediately following submersion of the hand. Furthermore, the plastic bag with tape method was rated poorly by all 23 participants based on efficacy and comfort.2

In the same study, participants also reported that removal of the adhesive tape was unpleasant and irritating,2 which suggests these same complaints may apply to use of a waterproof bandage, another potential option for coverage of the wound dressing. As an alternative, we propose the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector following nail surgery that allows patients to continue their regular activities while keeping the dressing dry and intact to allow for optimal wound healing.

The Technique

Our technique involves the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector that is sealed with a thick rubber cuff, allowing patients to perform regular daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, cleaning, and doing laundry without the wound dressing underneath becoming wet (Figure). Cast protectors made of flexible latex-free plastic are readily available and can slide on and off the arm as needed. We recommend that patients purchase the cast protector prior to undergoing surgery. There are options to fit most adults, with the opening generally accommodating arm diameters of 2 to 7 inches. These reusable cast protectors are available via popular online retailers and typically cost patients $10 to $15.

Practice Implications

In our experience, using a reusable waterproof cast protector following nail surgery is effective at keeping wound dressings dry and provides a practical solution for bathing and other activities involving water exposure. It is durable and easy to use, especially when compared to a plastic bag and waterproof tape. However, some patients find the waterproof seal uncomfortable, especially when worn for extended periods of time. According to online product feedback, limitations of the cast protector include potential leakage with prolonged immersion in water, swimming, or high-pressure water exposure. The cast protector should not be worn for more than 30 minutes, as it can restrict blood flow, and condensation from prolonged use may dampen the dressing. While we have not encountered allergic contact dermatitis associated with the use of cast protectors for this purpose in our practice, patients should be cautioned of this potential risk. While these cast protectors generally can accommodate a range of arm diameters, they may not fit all hand sizes or shapes and may reduce dexterity for motor tasks. Additionally, the patient must purchase the protector ahead of surgery.

Our technique involving the use of a waterproof arm cast protector is an affordable solution that allows patients to keep their wound dressing dry while continuing to perform regular daily activities. The cast protector also can be used following other dermatologic procedures (eg, biopsy, Mohs micrographic surgery) that involve the hand and lower arm when waterproof protection may be necessary.

Practice Gap

Postoperative care after nail biopsies can be challenging for patients due to the bulky dressing that must remain in place for 48 hours.1 The dressing can restrict daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, and other household tasks. A common solution is to cover the hand with a plastic bag secured with tape during water-related activities, but efficacy is variable. In one study, 23 participants tested this method by holding a paper towel with their hand covered by a plastic bag and measuring the weight of the paper towel before and after submersion of the hand in water.2 Any saturation of the paper towel was defined as failure; the failure rate was 52.2% (12/23) with motion (rotating the arm at the elbow for 30 seconds clockwise, counterclockwise, and left to right) and 60.9% (14/23) without motion. There was an average of 5.50 g of moisture accumulation without motion and 4.51 g with motion, with failure occurring most often immediately following submersion of the hand. Furthermore, the plastic bag with tape method was rated poorly by all 23 participants based on efficacy and comfort.2

In the same study, participants also reported that removal of the adhesive tape was unpleasant and irritating,2 which suggests these same complaints may apply to use of a waterproof bandage, another potential option for coverage of the wound dressing. As an alternative, we propose the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector following nail surgery that allows patients to continue their regular activities while keeping the dressing dry and intact to allow for optimal wound healing.

The Technique

Our technique involves the use of a removable waterproof arm cast protector that is sealed with a thick rubber cuff, allowing patients to perform regular daily activities such as bathing, washing dishes, cleaning, and doing laundry without the wound dressing underneath becoming wet (Figure). Cast protectors made of flexible latex-free plastic are readily available and can slide on and off the arm as needed. We recommend that patients purchase the cast protector prior to undergoing surgery. There are options to fit most adults, with the opening generally accommodating arm diameters of 2 to 7 inches. These reusable cast protectors are available via popular online retailers and typically cost patients $10 to $15.

Practice Implications

In our experience, using a reusable waterproof cast protector following nail surgery is effective at keeping wound dressings dry and provides a practical solution for bathing and other activities involving water exposure. It is durable and easy to use, especially when compared to a plastic bag and waterproof tape. However, some patients find the waterproof seal uncomfortable, especially when worn for extended periods of time. According to online product feedback, limitations of the cast protector include potential leakage with prolonged immersion in water, swimming, or high-pressure water exposure. The cast protector should not be worn for more than 30 minutes, as it can restrict blood flow, and condensation from prolonged use may dampen the dressing. While we have not encountered allergic contact dermatitis associated with the use of cast protectors for this purpose in our practice, patients should be cautioned of this potential risk. While these cast protectors generally can accommodate a range of arm diameters, they may not fit all hand sizes or shapes and may reduce dexterity for motor tasks. Additionally, the patient must purchase the protector ahead of surgery.

Our technique involving the use of a waterproof arm cast protector is an affordable solution that allows patients to keep their wound dressing dry while continuing to perform regular daily activities. The cast protector also can be used following other dermatologic procedures (eg, biopsy, Mohs micrographic surgery) that involve the hand and lower arm when waterproof protection may be necessary.

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. How we do it: pressure-padded dressing with self-adherent elastic wrap for wound care after nail surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:442–444. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002371

- Kwan S, Santoro A, Cheesman Q, et al. Efficacy of waterproof cast protectors and their ability to keep casts dry. J Hand Surg Am. 2023;48:803–809. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.05.006

- Ricardo JW, Lipner SR. How we do it: pressure-padded dressing with self-adherent elastic wrap for wound care after nail surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2021;47:442–444. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002371

- Kwan S, Santoro A, Cheesman Q, et al. Efficacy of waterproof cast protectors and their ability to keep casts dry. J Hand Surg Am. 2023;48:803–809. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2022.05.006

Waterproof Cast Protector Keeps Wound Dressing Intact Following Nail Surgery

Waterproof Cast Protector Keeps Wound Dressing Intact Following Nail Surgery

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Practice Gap

Tissue processing and complete margin assessment in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) are challenging concepts for residents, yet they are essential components of the dermatology residency curriculum. We propose a hands-on active teaching method using craft foam blocks to help residents master these techniques. Prior educational tools have included instructional videos1 as well as the peanut butter–cup and cantaloupe analogies.2,3 Specifically, our method utilizes inexpensive, readily available supplies that allow for repeated practice in a low-stakes environment without limitation of resources. This method provides an immersive, hands-on experience that allows residents to perform multiple practice excisions and simulate positive peripheral or deep margins, unlike tools that offer only fixed-depth or purely visual representations. Additionally, our learning model uniquely enables residents to flatten the simulated tissue, providing a clearer understanding of how a 3-dimensional specimen is transformed on a slide during histologic preparation. This step is particularly important, as tissue architecture can shift during processing, making it one of the most difficult concepts to grasp without hands-on experience. Having a multitude of teaching methods is crucial to accommodate various learning styles, and active learning has been shown to enhance retention for dermatology residents.4

The Technique

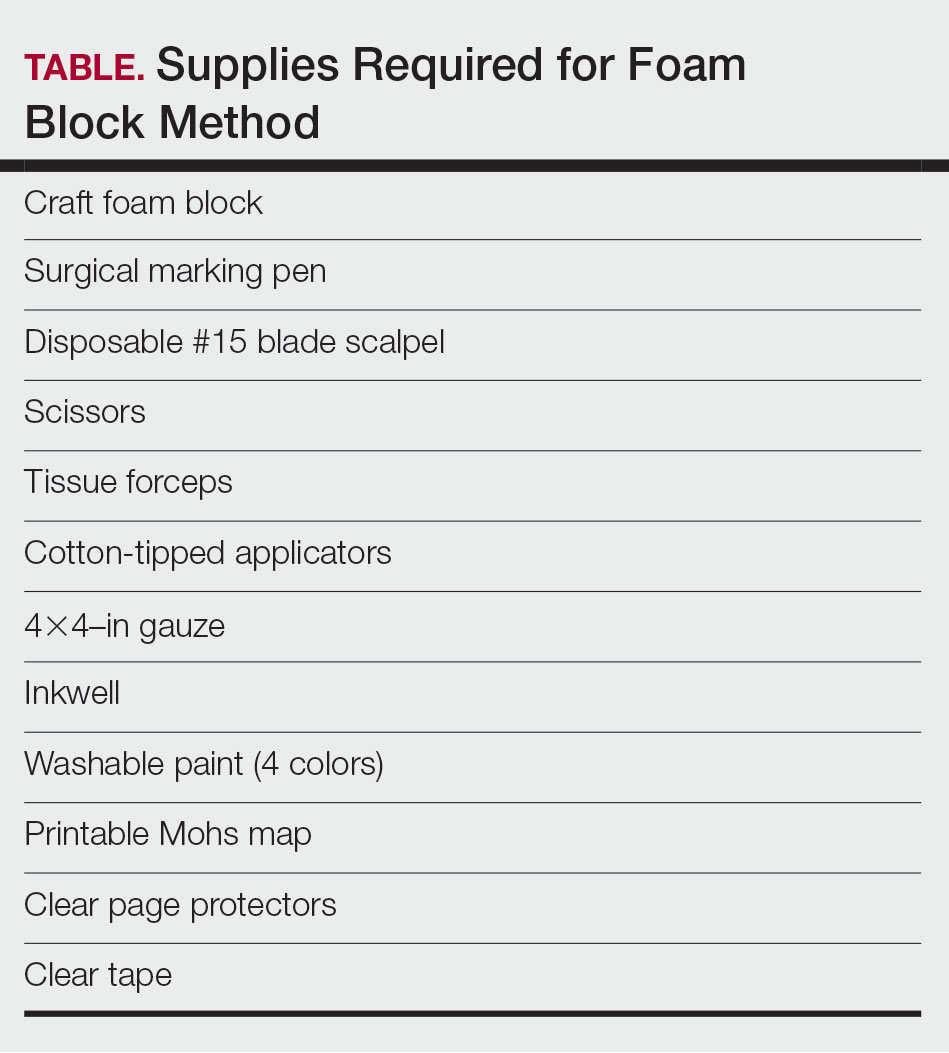

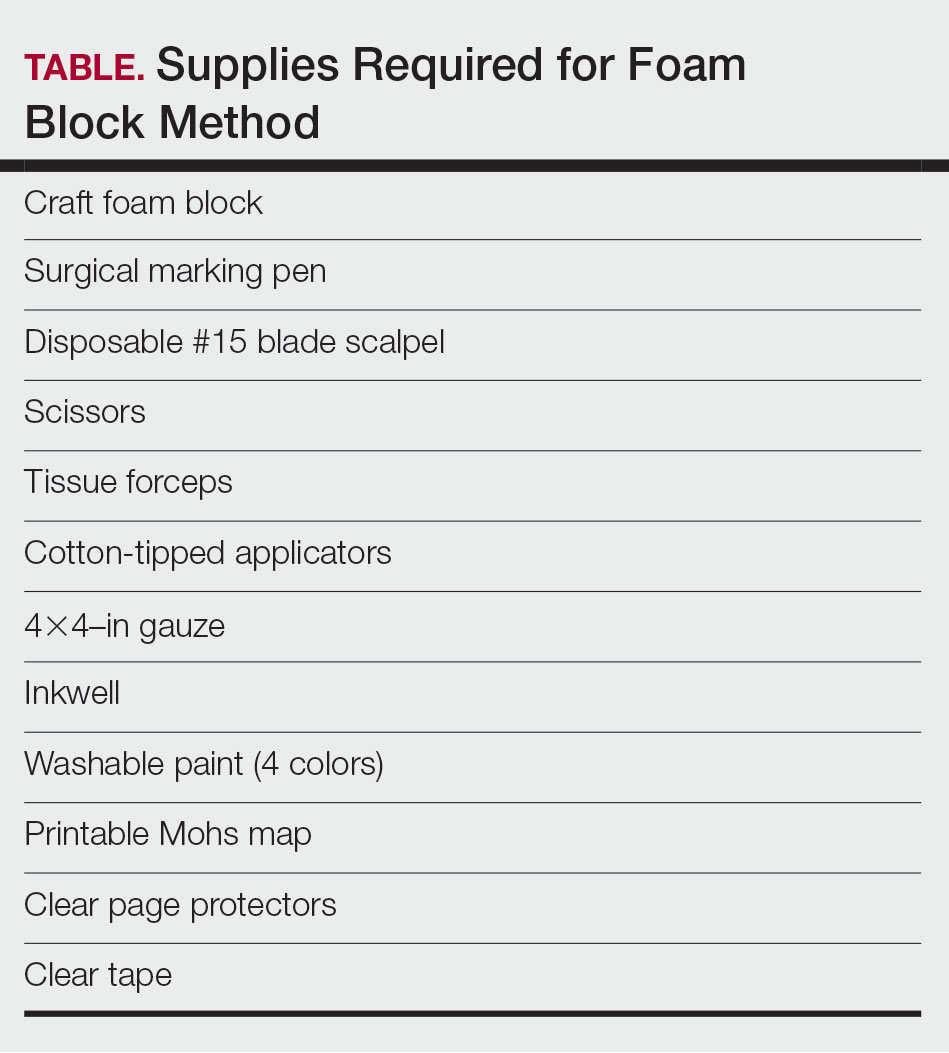

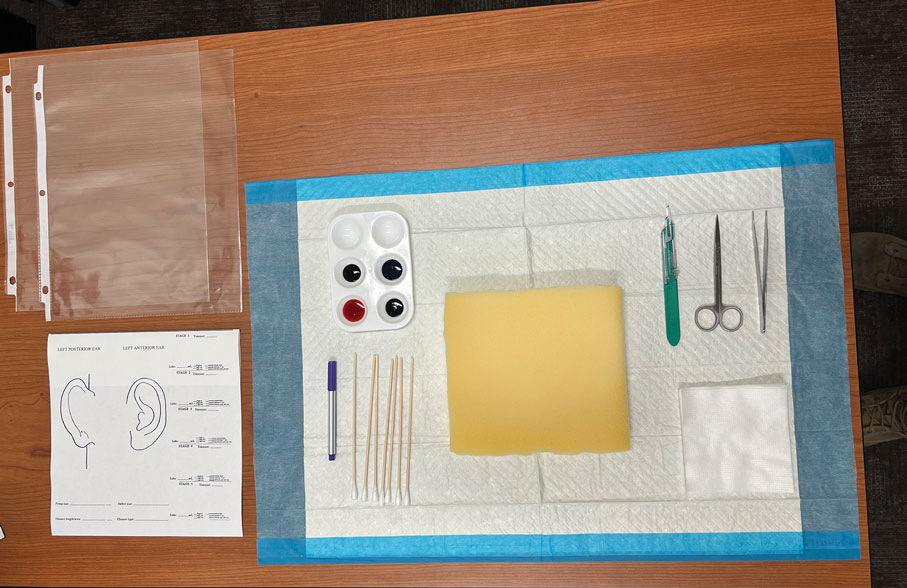

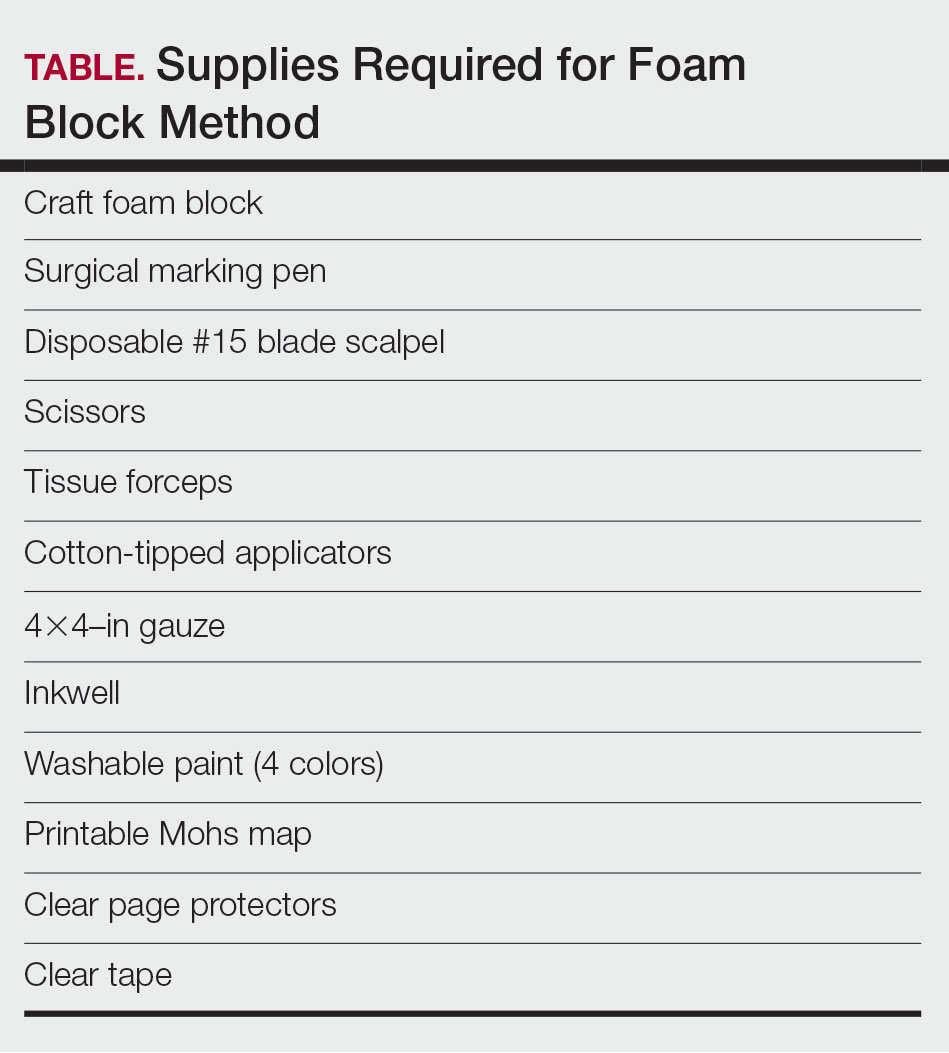

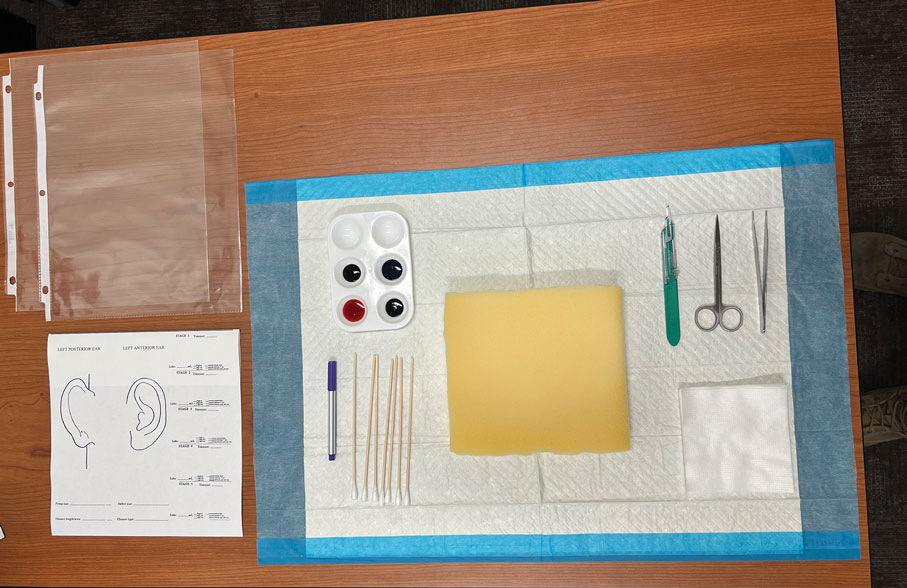

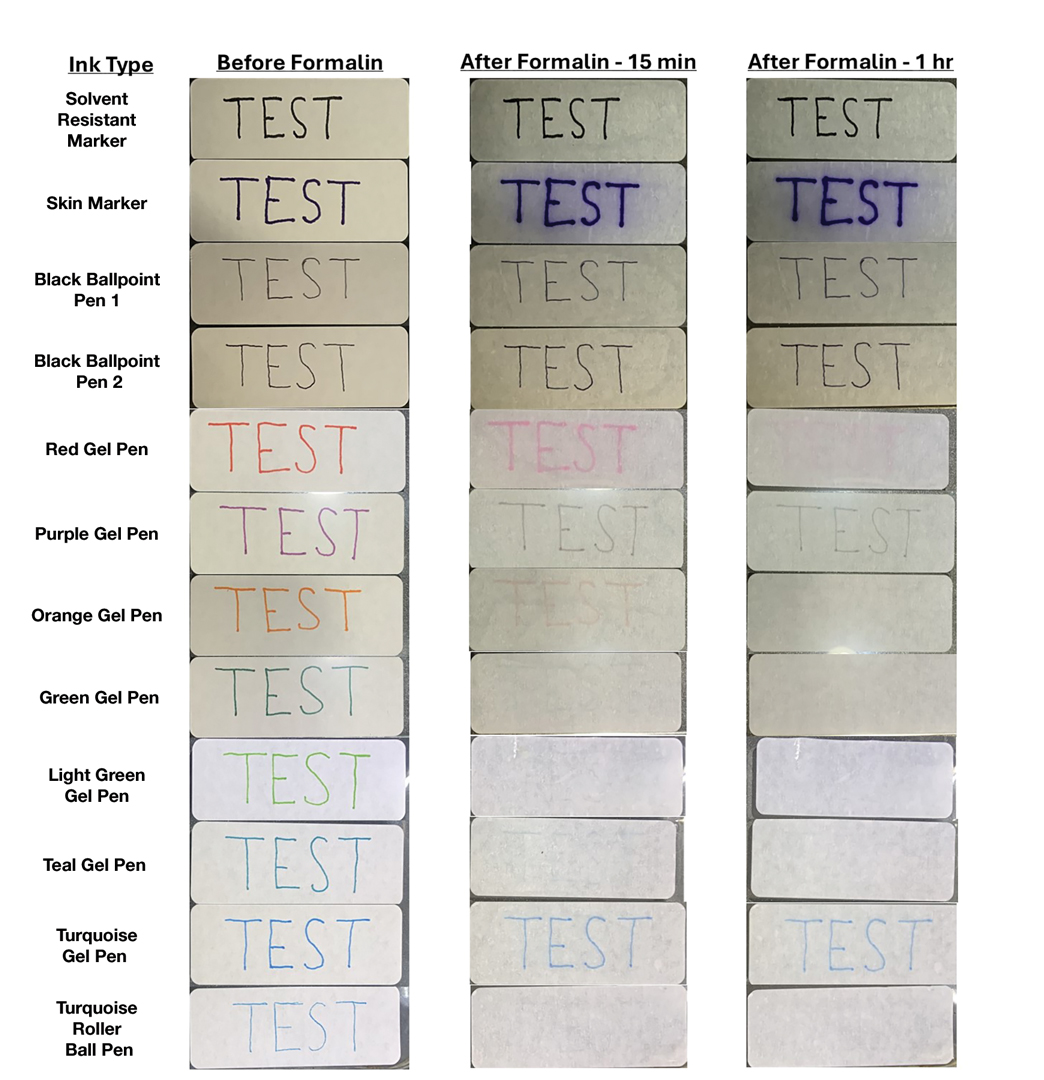

Residents use simple art supplies (including craft foam blocks and ink) and inexpensive, readily available surgical tools to simulate MMS (Table)(Figure 1). If desired, the resident can follow along with the comprehensive, stepwise textbook description of MMS, outlined by Benedetto et al5 to contextualize this hands-on exercise within a standardized didactic framework.

The foam block, which represents patient tissue, serves as the specimen. The resident begins by freehand drawing a simulated cutaneous tumor directly onto the foam using a surgical marking pen. At this point, the instructor discusses the advantages and limitations of tumor debulking with a sharp blade or curette. Residents then mark appropriate margins (1-3 mm) of normal-appearing “epidermis” on the foam block and add hash marks for orientation. This is another opportunity for the instructor to discuss common methods for marking tissue in vivo and to review situations when larger or smaller margins might be appropriate.

Next, the resident removes the first layer of simulated tissue using a disposable #15 blade scalpel at a 45° angle circumferentially and deep around the representative tumor. The resident also may use scissors and tissue forceps to remove the representative tumor. Next, the excised foam layer (the simulated “specimen”) is transferred to gauze. To demonstrate a positive margin, the resident or instructor marks the deep or peripheral foam block with a surgical marking pen, indicating residual tumor (Figure 2). This allows for multiple sequential layers of foam to be removed, demonstrating successive stages of MMS.

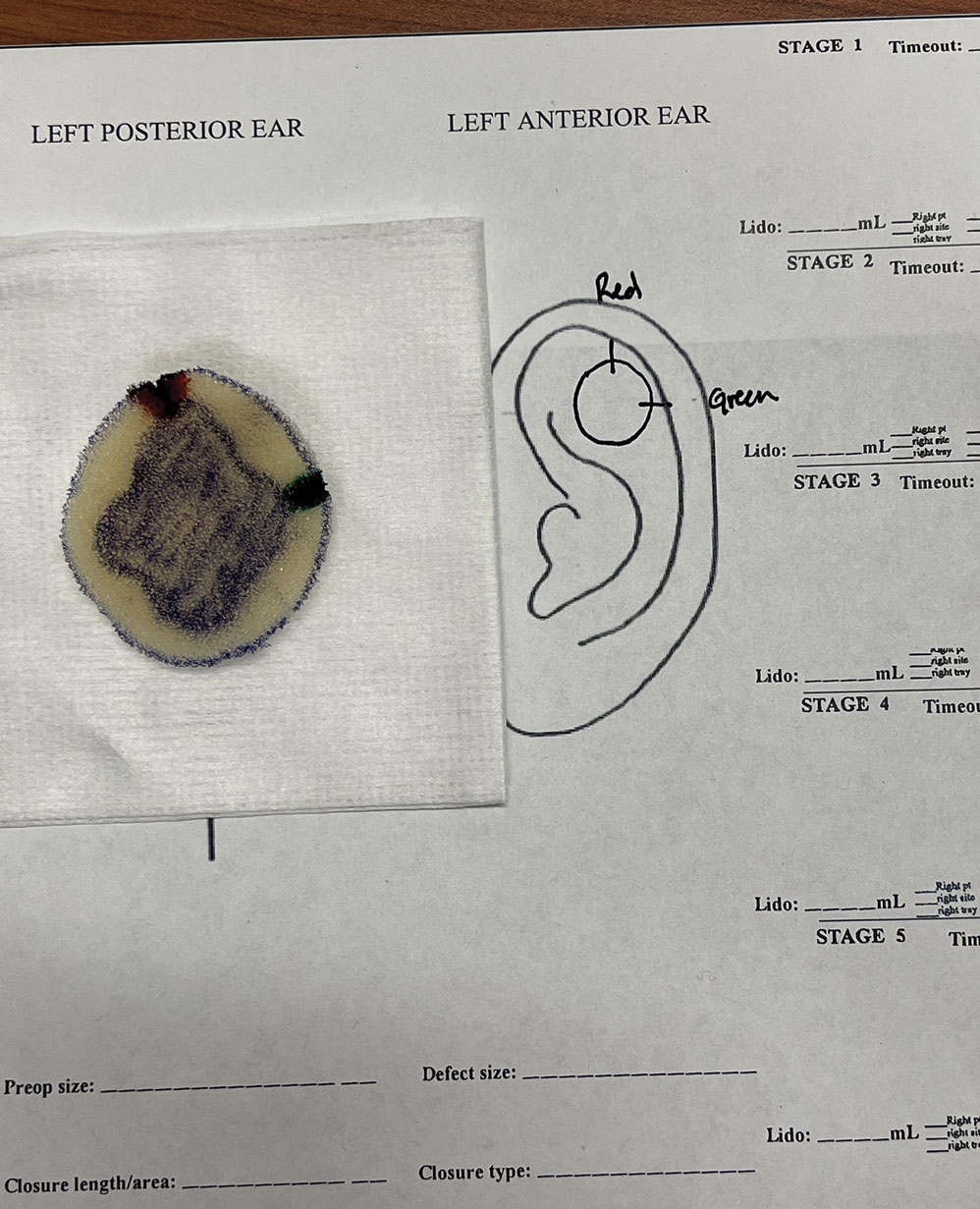

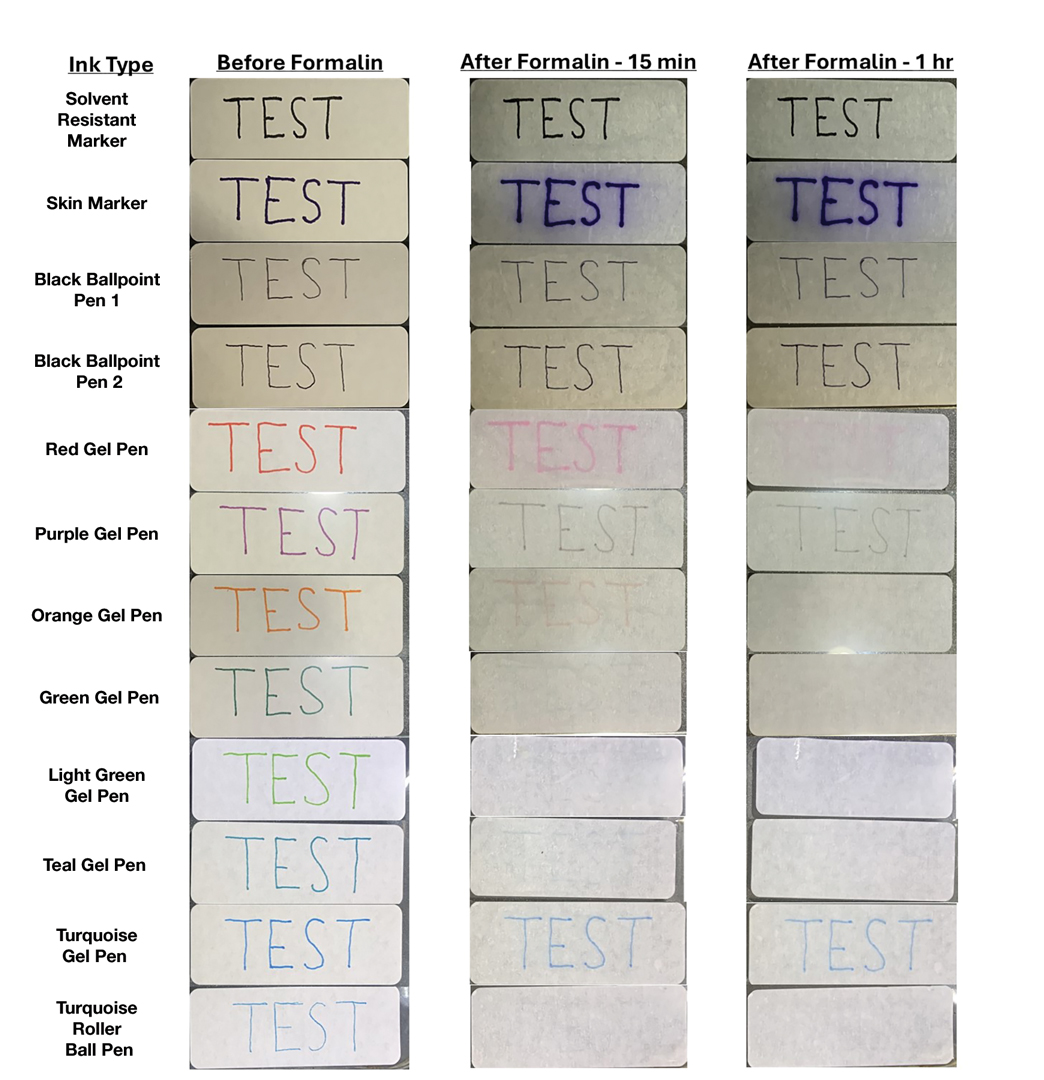

An inkwell holds different colors of washable paint to simulate tissue inking. After excision, the resident uses cotton-tipped applicators to apply different paint colors to the edges of the excised foam specimen at designated orientation points (eg, 3 o'clock and 12 o'clock). The resident then records the location of the excised sample by hand-drawing it on a printable Mohs map, labeling the corresponding paint colors to indicate orientation (Figure 3).

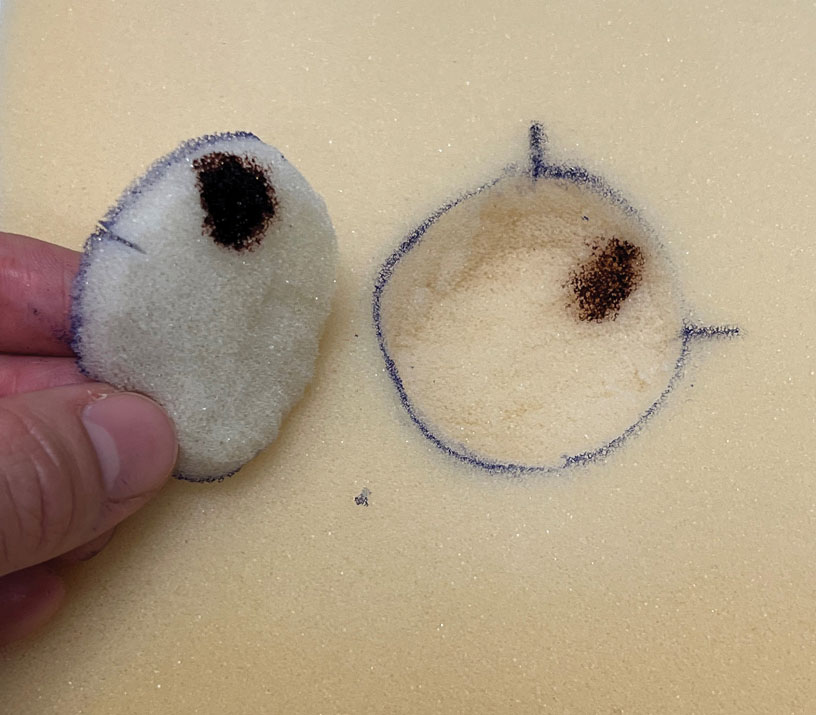

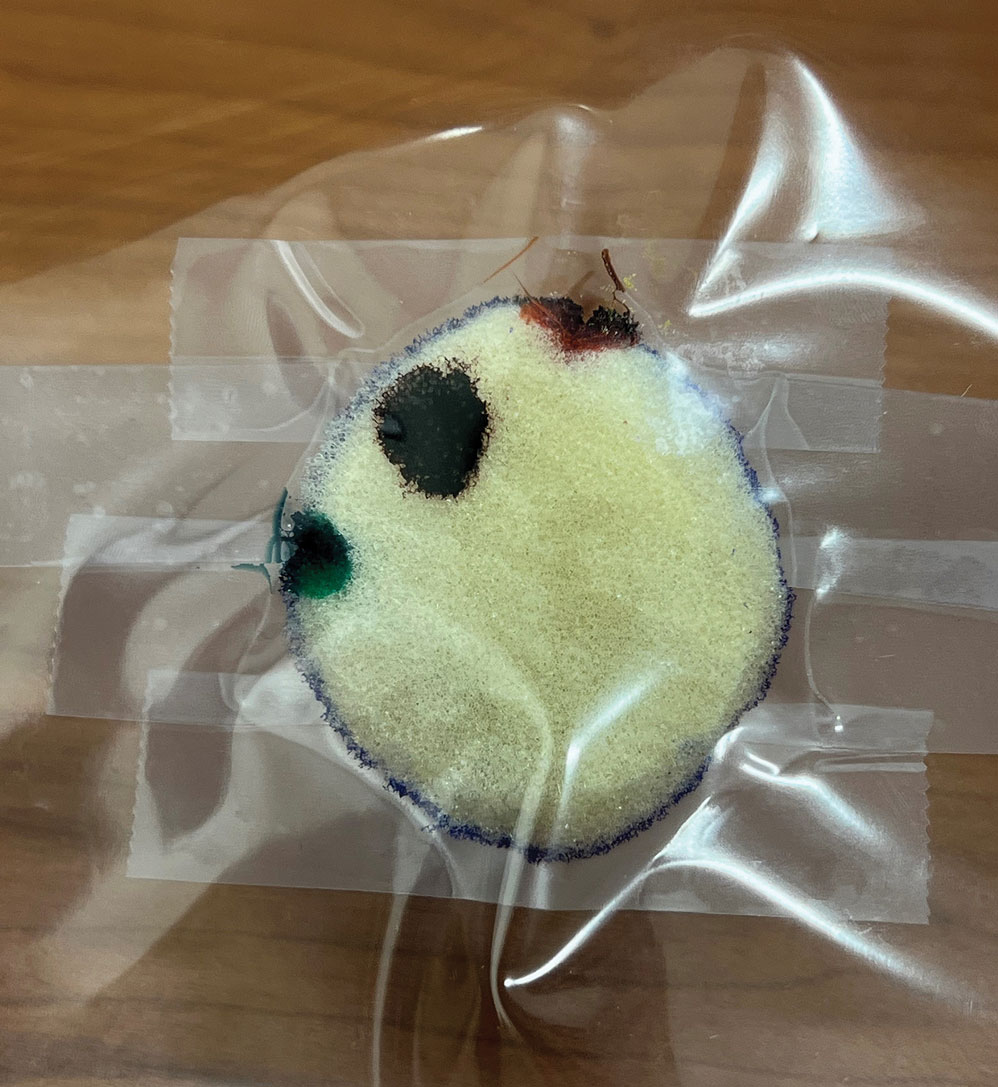

The resident then places the specimen between 2 plastic page protectors mimicking a glass slide and cover slip. Clear tape can be used to help flatten the specimen (Figure 4). The tissue is compressed between the page protector so that the simulated epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat are all in the same plane. At this stage, the instructor may discuss the use of relaxing incisions, especially for deeper tissue specimens or when excision at a 45° bevel is not achieved.5 The view from the underside of the page protector reveals 100% of the specimen’s margin and mimics the first cut off the tissue block. The resident can visualize the complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep margins and can easily identify any positive margins. At this point, the exercise can conclude, or the resident can explore further stages for positive margins, bisected specimens, or other tissue preparation variations.

Practice Implications

By individually designing and removing a representative tumor with margins, creating hash marks, and preparing a tissue specimen for histologic analysis, our interactive teaching method provides dermatology residents with a relatively simple, effective, and active learning experience for MMS outside the surgical setting. Using a piece of craft foam allows the representative tissue to be manipulated and flattened, similar to cutaneous tissue. This method was implemented and refined across 3 separate teaching sessions held by teaching faculty (E.I.P and E.B.W.) at the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium Dermatology Residency Program (San Antonio, Texas). This method has consistently generated strong resident engagement and prompted insightful questions and discussions. Program directors at other residency programs can readily incorporate this method in their surgical curriculum by allocating a brief didactic period to the exercise and facilitating the discussion with a dermatologic surgeon. Its simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness make the foam block model an easily adoptable teaching tool for dermatology residency programs seeking to provide a comprehensive, hands-on understanding of MMS.

- McNeil E, Reich H, Hurliman E. Educational video improves dermatology residents’ understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery: a surveybased matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:926-927. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.013

- Lee E, Wolverton JE, Somani AK. A simple, effective analogy to elucidate the Mohs micrographic surgery procedure—the peanut butter cup. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:743-744. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0614

- Vassantachart JM, Guccione J, Seeburger J. Clinical pearl: Mohs cantaloupe analogy for the dermatology resident. Cutis. 2018; 102:65-66.

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425. doi:10.1080/01421590801946988

- Benedetto PX, Poblete-Lopez C. Mohs micrographic surgery technique. Dermatol Clinics. 2011;29:141-151. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.02.002

Practice Gap

Tissue processing and complete margin assessment in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) are challenging concepts for residents, yet they are essential components of the dermatology residency curriculum. We propose a hands-on active teaching method using craft foam blocks to help residents master these techniques. Prior educational tools have included instructional videos1 as well as the peanut butter–cup and cantaloupe analogies.2,3 Specifically, our method utilizes inexpensive, readily available supplies that allow for repeated practice in a low-stakes environment without limitation of resources. This method provides an immersive, hands-on experience that allows residents to perform multiple practice excisions and simulate positive peripheral or deep margins, unlike tools that offer only fixed-depth or purely visual representations. Additionally, our learning model uniquely enables residents to flatten the simulated tissue, providing a clearer understanding of how a 3-dimensional specimen is transformed on a slide during histologic preparation. This step is particularly important, as tissue architecture can shift during processing, making it one of the most difficult concepts to grasp without hands-on experience. Having a multitude of teaching methods is crucial to accommodate various learning styles, and active learning has been shown to enhance retention for dermatology residents.4

The Technique

Residents use simple art supplies (including craft foam blocks and ink) and inexpensive, readily available surgical tools to simulate MMS (Table)(Figure 1). If desired, the resident can follow along with the comprehensive, stepwise textbook description of MMS, outlined by Benedetto et al5 to contextualize this hands-on exercise within a standardized didactic framework.

The foam block, which represents patient tissue, serves as the specimen. The resident begins by freehand drawing a simulated cutaneous tumor directly onto the foam using a surgical marking pen. At this point, the instructor discusses the advantages and limitations of tumor debulking with a sharp blade or curette. Residents then mark appropriate margins (1-3 mm) of normal-appearing “epidermis” on the foam block and add hash marks for orientation. This is another opportunity for the instructor to discuss common methods for marking tissue in vivo and to review situations when larger or smaller margins might be appropriate.

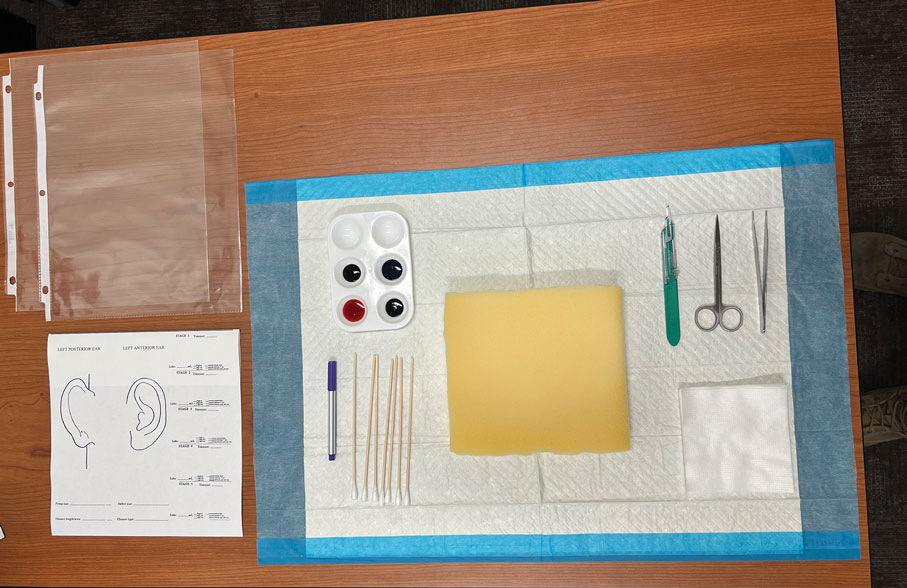

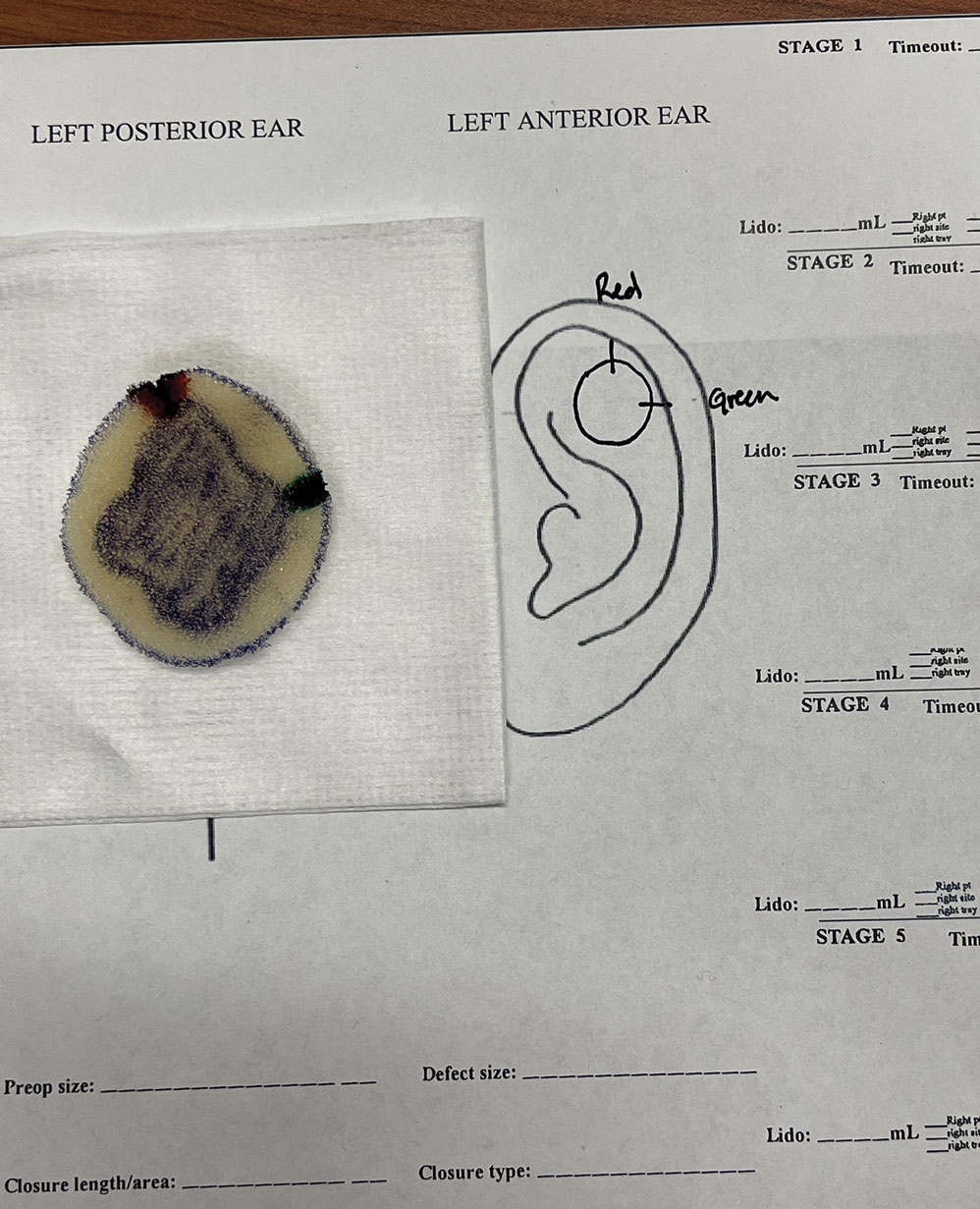

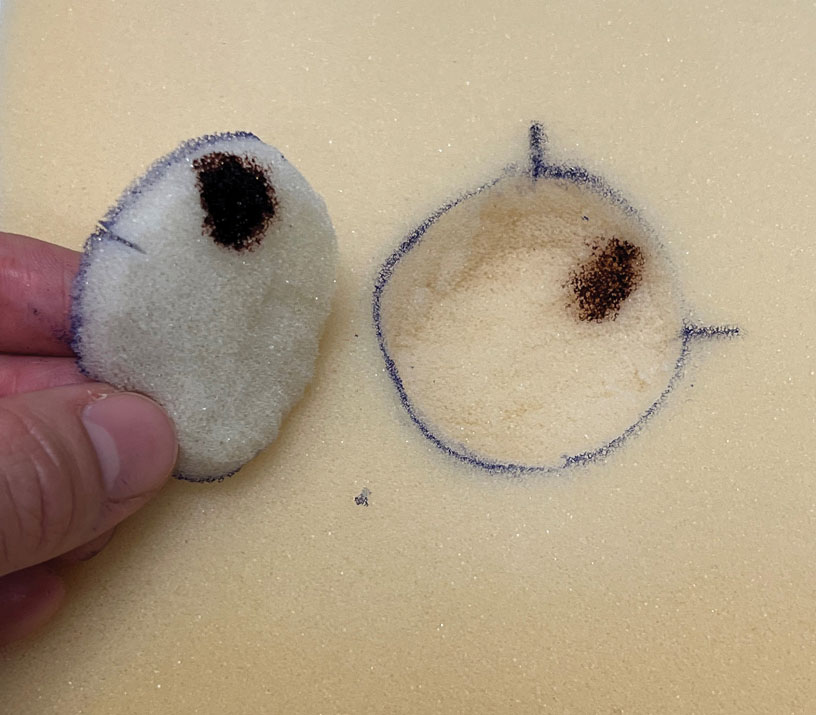

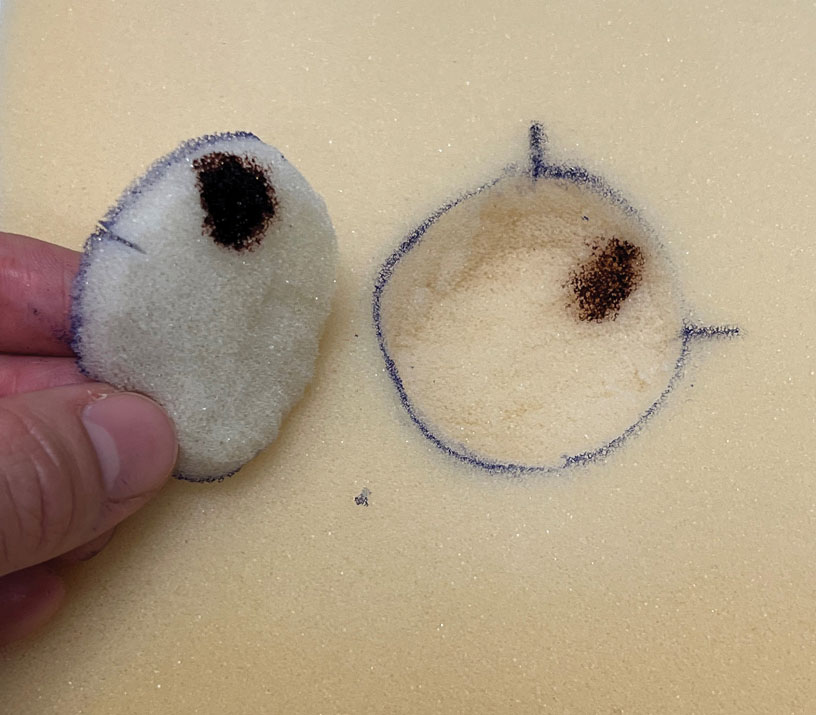

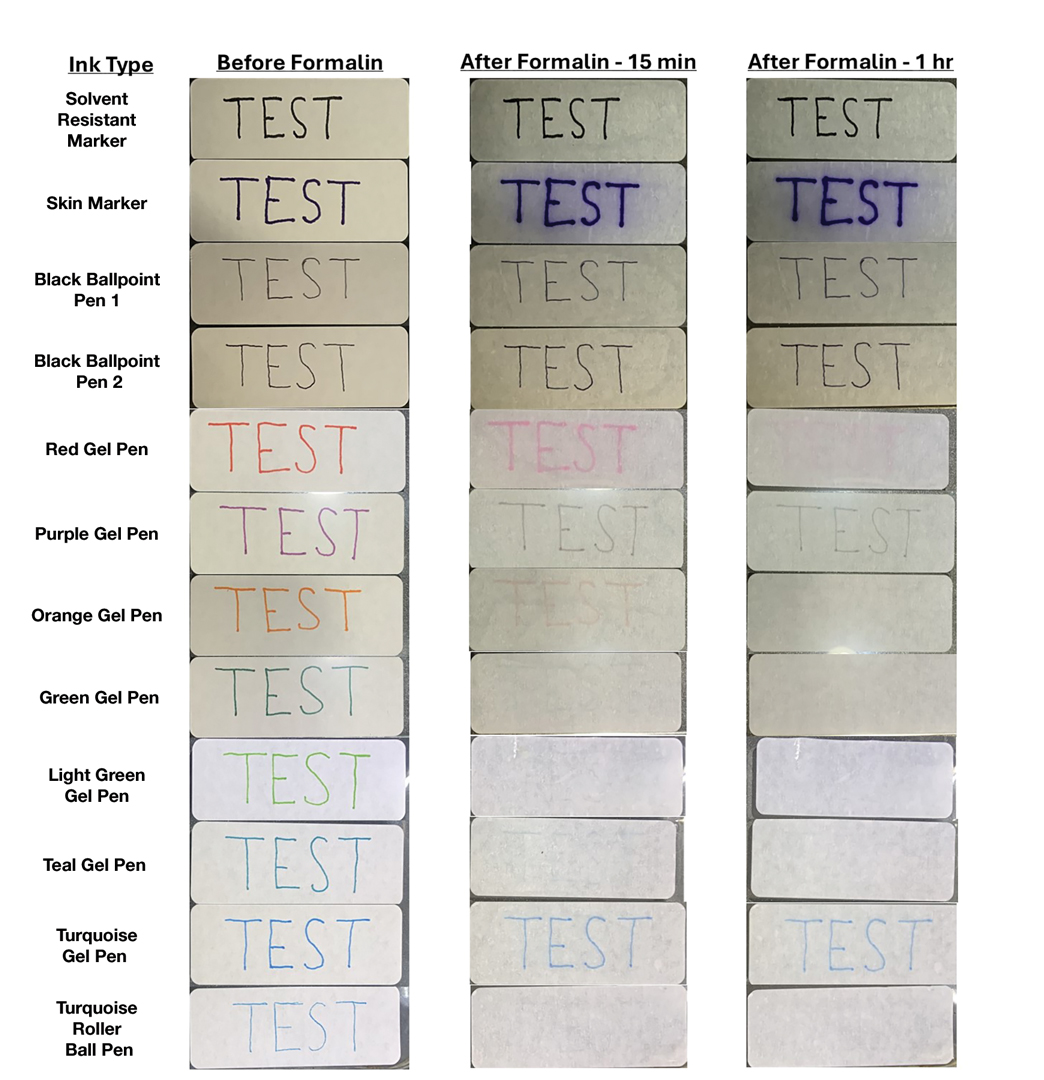

Next, the resident removes the first layer of simulated tissue using a disposable #15 blade scalpel at a 45° angle circumferentially and deep around the representative tumor. The resident also may use scissors and tissue forceps to remove the representative tumor. Next, the excised foam layer (the simulated “specimen”) is transferred to gauze. To demonstrate a positive margin, the resident or instructor marks the deep or peripheral foam block with a surgical marking pen, indicating residual tumor (Figure 2). This allows for multiple sequential layers of foam to be removed, demonstrating successive stages of MMS.

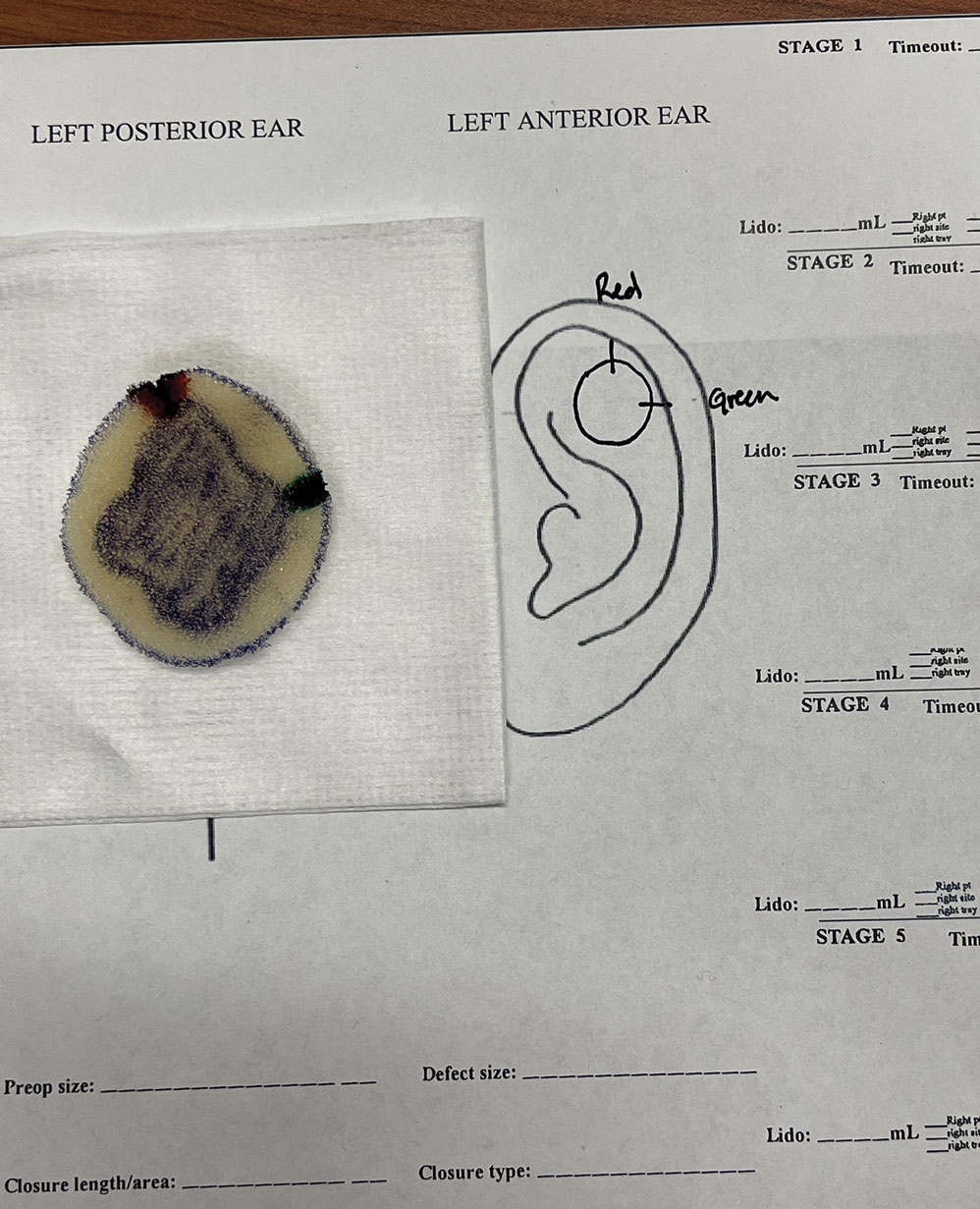

An inkwell holds different colors of washable paint to simulate tissue inking. After excision, the resident uses cotton-tipped applicators to apply different paint colors to the edges of the excised foam specimen at designated orientation points (eg, 3 o'clock and 12 o'clock). The resident then records the location of the excised sample by hand-drawing it on a printable Mohs map, labeling the corresponding paint colors to indicate orientation (Figure 3).

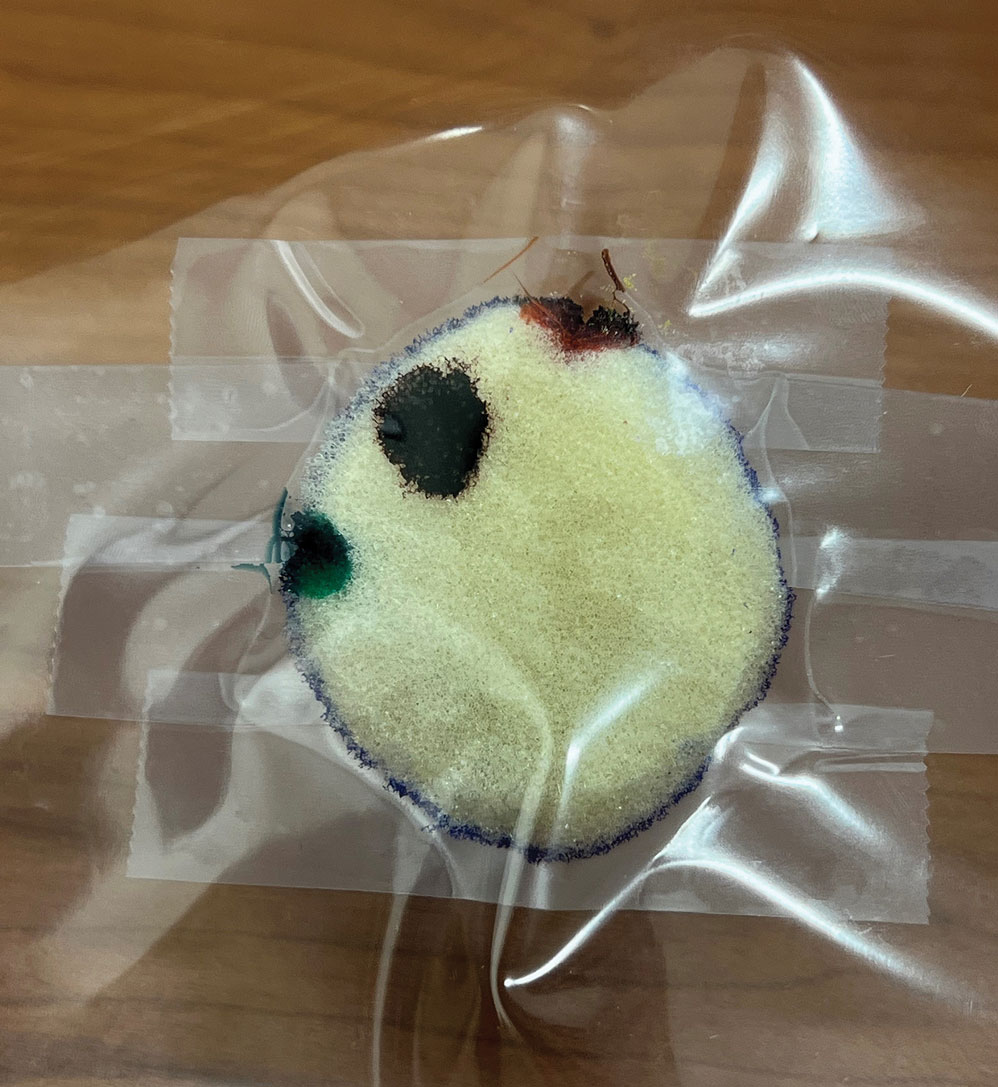

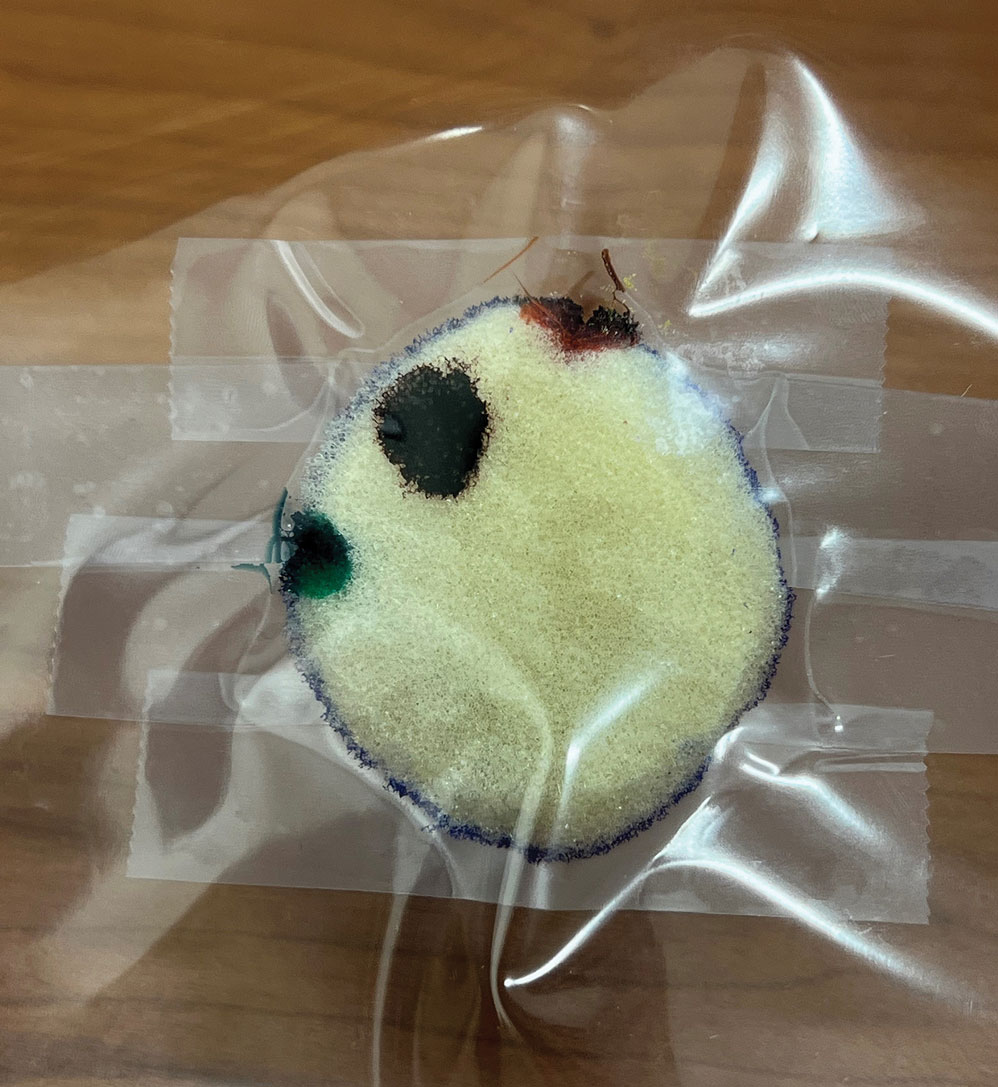

The resident then places the specimen between 2 plastic page protectors mimicking a glass slide and cover slip. Clear tape can be used to help flatten the specimen (Figure 4). The tissue is compressed between the page protector so that the simulated epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat are all in the same plane. At this stage, the instructor may discuss the use of relaxing incisions, especially for deeper tissue specimens or when excision at a 45° bevel is not achieved.5 The view from the underside of the page protector reveals 100% of the specimen’s margin and mimics the first cut off the tissue block. The resident can visualize the complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep margins and can easily identify any positive margins. At this point, the exercise can conclude, or the resident can explore further stages for positive margins, bisected specimens, or other tissue preparation variations.

Practice Implications

By individually designing and removing a representative tumor with margins, creating hash marks, and preparing a tissue specimen for histologic analysis, our interactive teaching method provides dermatology residents with a relatively simple, effective, and active learning experience for MMS outside the surgical setting. Using a piece of craft foam allows the representative tissue to be manipulated and flattened, similar to cutaneous tissue. This method was implemented and refined across 3 separate teaching sessions held by teaching faculty (E.I.P and E.B.W.) at the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium Dermatology Residency Program (San Antonio, Texas). This method has consistently generated strong resident engagement and prompted insightful questions and discussions. Program directors at other residency programs can readily incorporate this method in their surgical curriculum by allocating a brief didactic period to the exercise and facilitating the discussion with a dermatologic surgeon. Its simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness make the foam block model an easily adoptable teaching tool for dermatology residency programs seeking to provide a comprehensive, hands-on understanding of MMS.

Practice Gap

Tissue processing and complete margin assessment in Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) are challenging concepts for residents, yet they are essential components of the dermatology residency curriculum. We propose a hands-on active teaching method using craft foam blocks to help residents master these techniques. Prior educational tools have included instructional videos1 as well as the peanut butter–cup and cantaloupe analogies.2,3 Specifically, our method utilizes inexpensive, readily available supplies that allow for repeated practice in a low-stakes environment without limitation of resources. This method provides an immersive, hands-on experience that allows residents to perform multiple practice excisions and simulate positive peripheral or deep margins, unlike tools that offer only fixed-depth or purely visual representations. Additionally, our learning model uniquely enables residents to flatten the simulated tissue, providing a clearer understanding of how a 3-dimensional specimen is transformed on a slide during histologic preparation. This step is particularly important, as tissue architecture can shift during processing, making it one of the most difficult concepts to grasp without hands-on experience. Having a multitude of teaching methods is crucial to accommodate various learning styles, and active learning has been shown to enhance retention for dermatology residents.4

The Technique

Residents use simple art supplies (including craft foam blocks and ink) and inexpensive, readily available surgical tools to simulate MMS (Table)(Figure 1). If desired, the resident can follow along with the comprehensive, stepwise textbook description of MMS, outlined by Benedetto et al5 to contextualize this hands-on exercise within a standardized didactic framework.

The foam block, which represents patient tissue, serves as the specimen. The resident begins by freehand drawing a simulated cutaneous tumor directly onto the foam using a surgical marking pen. At this point, the instructor discusses the advantages and limitations of tumor debulking with a sharp blade or curette. Residents then mark appropriate margins (1-3 mm) of normal-appearing “epidermis” on the foam block and add hash marks for orientation. This is another opportunity for the instructor to discuss common methods for marking tissue in vivo and to review situations when larger or smaller margins might be appropriate.

Next, the resident removes the first layer of simulated tissue using a disposable #15 blade scalpel at a 45° angle circumferentially and deep around the representative tumor. The resident also may use scissors and tissue forceps to remove the representative tumor. Next, the excised foam layer (the simulated “specimen”) is transferred to gauze. To demonstrate a positive margin, the resident or instructor marks the deep or peripheral foam block with a surgical marking pen, indicating residual tumor (Figure 2). This allows for multiple sequential layers of foam to be removed, demonstrating successive stages of MMS.

An inkwell holds different colors of washable paint to simulate tissue inking. After excision, the resident uses cotton-tipped applicators to apply different paint colors to the edges of the excised foam specimen at designated orientation points (eg, 3 o'clock and 12 o'clock). The resident then records the location of the excised sample by hand-drawing it on a printable Mohs map, labeling the corresponding paint colors to indicate orientation (Figure 3).

The resident then places the specimen between 2 plastic page protectors mimicking a glass slide and cover slip. Clear tape can be used to help flatten the specimen (Figure 4). The tissue is compressed between the page protector so that the simulated epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous fat are all in the same plane. At this stage, the instructor may discuss the use of relaxing incisions, especially for deeper tissue specimens or when excision at a 45° bevel is not achieved.5 The view from the underside of the page protector reveals 100% of the specimen’s margin and mimics the first cut off the tissue block. The resident can visualize the complete circumferential, peripheral, and deep margins and can easily identify any positive margins. At this point, the exercise can conclude, or the resident can explore further stages for positive margins, bisected specimens, or other tissue preparation variations.

Practice Implications

By individually designing and removing a representative tumor with margins, creating hash marks, and preparing a tissue specimen for histologic analysis, our interactive teaching method provides dermatology residents with a relatively simple, effective, and active learning experience for MMS outside the surgical setting. Using a piece of craft foam allows the representative tissue to be manipulated and flattened, similar to cutaneous tissue. This method was implemented and refined across 3 separate teaching sessions held by teaching faculty (E.I.P and E.B.W.) at the San Antonio Uniformed Services Health Education Consortium Dermatology Residency Program (San Antonio, Texas). This method has consistently generated strong resident engagement and prompted insightful questions and discussions. Program directors at other residency programs can readily incorporate this method in their surgical curriculum by allocating a brief didactic period to the exercise and facilitating the discussion with a dermatologic surgeon. Its simplicity, low cost, and effectiveness make the foam block model an easily adoptable teaching tool for dermatology residency programs seeking to provide a comprehensive, hands-on understanding of MMS.

- McNeil E, Reich H, Hurliman E. Educational video improves dermatology residents’ understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery: a surveybased matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:926-927. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.013

- Lee E, Wolverton JE, Somani AK. A simple, effective analogy to elucidate the Mohs micrographic surgery procedure—the peanut butter cup. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:743-744. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0614

- Vassantachart JM, Guccione J, Seeburger J. Clinical pearl: Mohs cantaloupe analogy for the dermatology resident. Cutis. 2018; 102:65-66.

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425. doi:10.1080/01421590801946988

- Benedetto PX, Poblete-Lopez C. Mohs micrographic surgery technique. Dermatol Clinics. 2011;29:141-151. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.02.002

- McNeil E, Reich H, Hurliman E. Educational video improves dermatology residents’ understanding of Mohs micrographic surgery: a surveybased matched cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:926-927. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2020.01.013

- Lee E, Wolverton JE, Somani AK. A simple, effective analogy to elucidate the Mohs micrographic surgery procedure—the peanut butter cup. JAMA Dermatol. 2017;153:743-744. doi:10.1001 /jamadermatol.2017.0614

- Vassantachart JM, Guccione J, Seeburger J. Clinical pearl: Mohs cantaloupe analogy for the dermatology resident. Cutis. 2018; 102:65-66.

- Stratman EJ, Vogel CA, Reck SJ, et al. Analysis of dermatology resident self-reported successful learning styles and implications for core competency curriculum development. Med Teach. 2008;30:420-425. doi:10.1080/01421590801946988

- Benedetto PX, Poblete-Lopez C. Mohs micrographic surgery technique. Dermatol Clinics. 2011;29:141-151. doi:10.1016/j.det.2011.02.002

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Interactive Approach to Teaching Mohs Micrographic Surgery to Dermatology Residents

Poly-L-Lactic Acid Reconstitution Technique to Reduce Needle Obstruction

Poly-L-Lactic Acid Reconstitution Technique to Reduce Needle Obstruction

Practice Gap

Poly-L-lactic acid is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for addressing fat loss due to HAART in patients with HIV.2,3 When used as a dermal filler for correction of facial lipoatrophy, PLLA is well tolerated and has been shown to improve quality of life.2,3 Poly-L-lactic acid is available for clinical use as microparticles of lyophilized alpha hydroxy acid polymers. Once injected (after the carrier substance is absorbed), PLLA induces an inflammatory response that ultimately leads to the production of new collagen.3 Unfortunately, PLLA microparticles often obstruct needles and make the product difficult to use, potentially hindering effective injection; thus, it is in the best interest of the patient to mitigate needle obstruction during this procedure. In this article, we describe a simple and effective way to mitigate this problem by utilizing a water bath to warm the filler prior to injection.

Technique

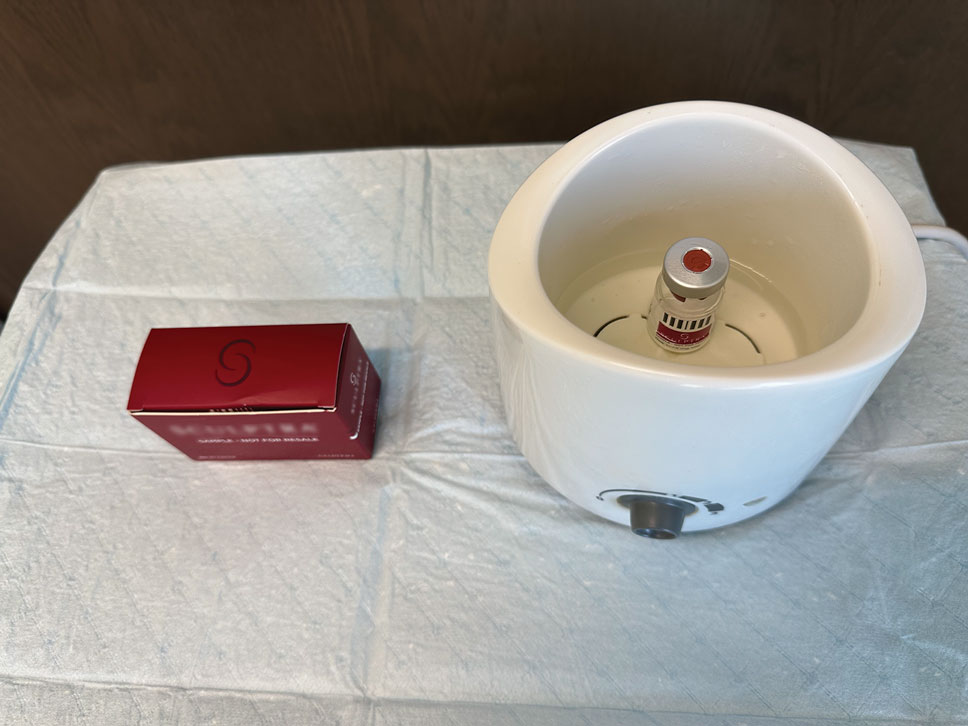

The required supplies include a thermostatic water bath, reconstituted PLLA, a syringe, and a 26-gauge injection needle. Because laboratory-grade heated water baths typically cost between $300 and $3000,4 we recommend using a more affordable, commercially available thermostatic water bath (eg, baby bottle warmer)(Figure 1) to warm the filler prior to injection, as the optimal temperature for this technique can still be achieved while remaining cost effective. Vials of PLLA reconstituted with 7 mL of sterile water and 2 mL lidocaine hydrochloride 1% should be labeled with the date of reconstitution and manually agitated for 30 seconds. The reconstituted product should be stored for 24 hours to ensure even suspension and powder saturation.5 On the day of the procedure, the vial should be placed into the water bath (heated to 100 °C) for 10 minutes prior to injection (Figure 2) and agitated again immediately before withdrawal into the syringe. The clinician then should sterilize the rubber top and draw the product from the warmed vial using the same size needle that will be used for injection. Although a larger gauge needle may make drawing up the product easier in typical practice, drawing and injecting with the same gauge needle helps prevent larger particles from clogging a smaller injection needle. Using a 26-gauge injection needle for withdrawal further reduces clogging by serving as a filter to prevent larger product particles from entering the injection syringe. The vials of PLLA can be kept in the water bath throughout the procedure between uses to keep the filler at a consistent temperature.

Practice Implications

Although many clinicians reduce needle obstructions by warming PLLA before injection, a published protocol currently is not available. One consideration when utilizing this technique is the limited data on the clinical stability and efficacy of PLLA at varying temperatures. Two studies recommend bringing the reconstituted vial to room temperature prior to injection, while others have documented an endothermic melting point in the range of 120 °C to 180

- James J, Carruthers A, Carruthers J. HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:979-986. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02099.x

- Duracinsky M, Leclercq P, Herrmann S, et al. Safety of poly-L-lactic acid (New-Fill®) in the treatment of facial lipoatrophy: a large observational study among HIV-positive patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:474. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-474

- Sickles CK, Nassereddin A, Patel P, et al. Poly-L-lactic acid. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 28, 2024. Accessed October 31, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507871/

- Laboratory equipment: Water bath. Global Lab Supply. (n.d.). http://www.globallabsupply.com/Water-Bath-s/2122.htm

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, et al. Practices in the usage and reconstitution of poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:880-886.

- Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R, Lorenc ZP, et al. Consensus recommendations on the use of injectable poly-L-lactic acid for facial and nonfacial volumization. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:s44-51.

- Sedush NG, Kalinin KT, Azarkevich PN, et al. Physicochemical characteristics and hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid dermal fillers: a comparative study. Cosmetics. 2023;10:110. doi:10.3390/cosmetics10040110

Practice Gap

Poly-L-lactic acid is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for addressing fat loss due to HAART in patients with HIV.2,3 When used as a dermal filler for correction of facial lipoatrophy, PLLA is well tolerated and has been shown to improve quality of life.2,3 Poly-L-lactic acid is available for clinical use as microparticles of lyophilized alpha hydroxy acid polymers. Once injected (after the carrier substance is absorbed), PLLA induces an inflammatory response that ultimately leads to the production of new collagen.3 Unfortunately, PLLA microparticles often obstruct needles and make the product difficult to use, potentially hindering effective injection; thus, it is in the best interest of the patient to mitigate needle obstruction during this procedure. In this article, we describe a simple and effective way to mitigate this problem by utilizing a water bath to warm the filler prior to injection.

Technique

The required supplies include a thermostatic water bath, reconstituted PLLA, a syringe, and a 26-gauge injection needle. Because laboratory-grade heated water baths typically cost between $300 and $3000,4 we recommend using a more affordable, commercially available thermostatic water bath (eg, baby bottle warmer)(Figure 1) to warm the filler prior to injection, as the optimal temperature for this technique can still be achieved while remaining cost effective. Vials of PLLA reconstituted with 7 mL of sterile water and 2 mL lidocaine hydrochloride 1% should be labeled with the date of reconstitution and manually agitated for 30 seconds. The reconstituted product should be stored for 24 hours to ensure even suspension and powder saturation.5 On the day of the procedure, the vial should be placed into the water bath (heated to 100 °C) for 10 minutes prior to injection (Figure 2) and agitated again immediately before withdrawal into the syringe. The clinician then should sterilize the rubber top and draw the product from the warmed vial using the same size needle that will be used for injection. Although a larger gauge needle may make drawing up the product easier in typical practice, drawing and injecting with the same gauge needle helps prevent larger particles from clogging a smaller injection needle. Using a 26-gauge injection needle for withdrawal further reduces clogging by serving as a filter to prevent larger product particles from entering the injection syringe. The vials of PLLA can be kept in the water bath throughout the procedure between uses to keep the filler at a consistent temperature.

Practice Implications

Although many clinicians reduce needle obstructions by warming PLLA before injection, a published protocol currently is not available. One consideration when utilizing this technique is the limited data on the clinical stability and efficacy of PLLA at varying temperatures. Two studies recommend bringing the reconstituted vial to room temperature prior to injection, while others have documented an endothermic melting point in the range of 120 °C to 180

Practice Gap

Poly-L-lactic acid is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for addressing fat loss due to HAART in patients with HIV.2,3 When used as a dermal filler for correction of facial lipoatrophy, PLLA is well tolerated and has been shown to improve quality of life.2,3 Poly-L-lactic acid is available for clinical use as microparticles of lyophilized alpha hydroxy acid polymers. Once injected (after the carrier substance is absorbed), PLLA induces an inflammatory response that ultimately leads to the production of new collagen.3 Unfortunately, PLLA microparticles often obstruct needles and make the product difficult to use, potentially hindering effective injection; thus, it is in the best interest of the patient to mitigate needle obstruction during this procedure. In this article, we describe a simple and effective way to mitigate this problem by utilizing a water bath to warm the filler prior to injection.

Technique

The required supplies include a thermostatic water bath, reconstituted PLLA, a syringe, and a 26-gauge injection needle. Because laboratory-grade heated water baths typically cost between $300 and $3000,4 we recommend using a more affordable, commercially available thermostatic water bath (eg, baby bottle warmer)(Figure 1) to warm the filler prior to injection, as the optimal temperature for this technique can still be achieved while remaining cost effective. Vials of PLLA reconstituted with 7 mL of sterile water and 2 mL lidocaine hydrochloride 1% should be labeled with the date of reconstitution and manually agitated for 30 seconds. The reconstituted product should be stored for 24 hours to ensure even suspension and powder saturation.5 On the day of the procedure, the vial should be placed into the water bath (heated to 100 °C) for 10 minutes prior to injection (Figure 2) and agitated again immediately before withdrawal into the syringe. The clinician then should sterilize the rubber top and draw the product from the warmed vial using the same size needle that will be used for injection. Although a larger gauge needle may make drawing up the product easier in typical practice, drawing and injecting with the same gauge needle helps prevent larger particles from clogging a smaller injection needle. Using a 26-gauge injection needle for withdrawal further reduces clogging by serving as a filter to prevent larger product particles from entering the injection syringe. The vials of PLLA can be kept in the water bath throughout the procedure between uses to keep the filler at a consistent temperature.

Practice Implications

Although many clinicians reduce needle obstructions by warming PLLA before injection, a published protocol currently is not available. One consideration when utilizing this technique is the limited data on the clinical stability and efficacy of PLLA at varying temperatures. Two studies recommend bringing the reconstituted vial to room temperature prior to injection, while others have documented an endothermic melting point in the range of 120 °C to 180

- James J, Carruthers A, Carruthers J. HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:979-986. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02099.x

- Duracinsky M, Leclercq P, Herrmann S, et al. Safety of poly-L-lactic acid (New-Fill®) in the treatment of facial lipoatrophy: a large observational study among HIV-positive patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:474. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-474

- Sickles CK, Nassereddin A, Patel P, et al. Poly-L-lactic acid. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 28, 2024. Accessed October 31, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507871/

- Laboratory equipment: Water bath. Global Lab Supply. (n.d.). http://www.globallabsupply.com/Water-Bath-s/2122.htm

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, et al. Practices in the usage and reconstitution of poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:880-886.

- Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R, Lorenc ZP, et al. Consensus recommendations on the use of injectable poly-L-lactic acid for facial and nonfacial volumization. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:s44-51.

- Sedush NG, Kalinin KT, Azarkevich PN, et al. Physicochemical characteristics and hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid dermal fillers: a comparative study. Cosmetics. 2023;10:110. doi:10.3390/cosmetics10040110

- James J, Carruthers A, Carruthers J. HIV-associated facial lipoatrophy. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:979-986. doi:10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.02099.x

- Duracinsky M, Leclercq P, Herrmann S, et al. Safety of poly-L-lactic acid (New-Fill®) in the treatment of facial lipoatrophy: a large observational study among HIV-positive patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:474. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-14-474

- Sickles CK, Nassereddin A, Patel P, et al. Poly-L-lactic acid. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated February 28, 2024. Accessed October 31, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507871/

- Laboratory equipment: Water bath. Global Lab Supply. (n.d.). http://www.globallabsupply.com/Water-Bath-s/2122.htm

- Lin MJ, Dubin DP, Goldberg DJ, et al. Practices in the usage and reconstitution of poly-L-lactic acid. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:880-886.

- Vleggaar D, Fitzgerald R, Lorenc ZP, et al. Consensus recommendations on the use of injectable poly-L-lactic acid for facial and nonfacial volumization. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:s44-51.

- Sedush NG, Kalinin KT, Azarkevich PN, et al. Physicochemical characteristics and hydrolytic degradation of polylactic acid dermal fillers: a comparative study. Cosmetics. 2023;10:110. doi:10.3390/cosmetics10040110

Poly-L-Lactic Acid Reconstitution Technique to Reduce Needle Obstruction

Poly-L-Lactic Acid Reconstitution Technique to Reduce Needle Obstruction

Conservative Thickness Layers to Preserve Tattoo Appearance During Excisional Procedures

Conservative Thickness Layers to Preserve Tattoo Appearance During Excisional Procedures

Practice Gap

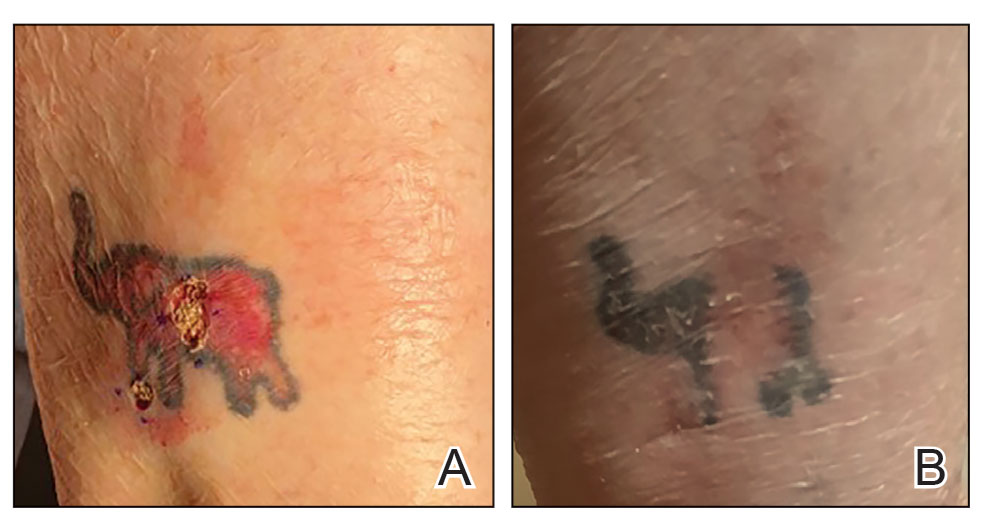

Tattoos have become increasingly prevalent in Western culture, with approximately 1 in 4 Americans having at least 1 tattoo. Individuals invest money, time, and even pain in getting tattoos, many of which hold special personal, family, or religious significance.1 Various cutaneous pathologies may arise in areas of the skin with tattoos, including malignancies and inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigment, and in these cases, surgical management may be indicated.2,3

Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) such as superficial basal cell carcinomas on broadly sun-damaged areas (eg, trunk, torso), squamous cell carcinomas, reactive keratoacanthomas, and reactive pseudoepitheliomatous squamous hyperplasia diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma have been reported to occur in or near areas of the skin with tattoos.2 Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is the standard of care for removing NMSCs, particularly when they manifest in cosmetically sensitive areas.4 This treatment option allows for careful guided resection of tumors to minimize the risk for recurrence; it also preserves healthy tissue, which typically results in a smaller radial defect after the procedure is complete.

Chronic reactions to tattoo pigment may include granulomatous tattoo reactions and pseudolymphomas.3 Treatment options may include immunosuppressives such as intralesional triamcinolone as well as pigment destruction via lasers5; however, not all tattoos are responsive to these treatments. Surgical excision is an effective and definitive treatment in this context, as tattoo pigment resides in or above the mid dermis to a depth of approximately 400 μm. Intradermal excision effectively removes the antigenic pigment.5

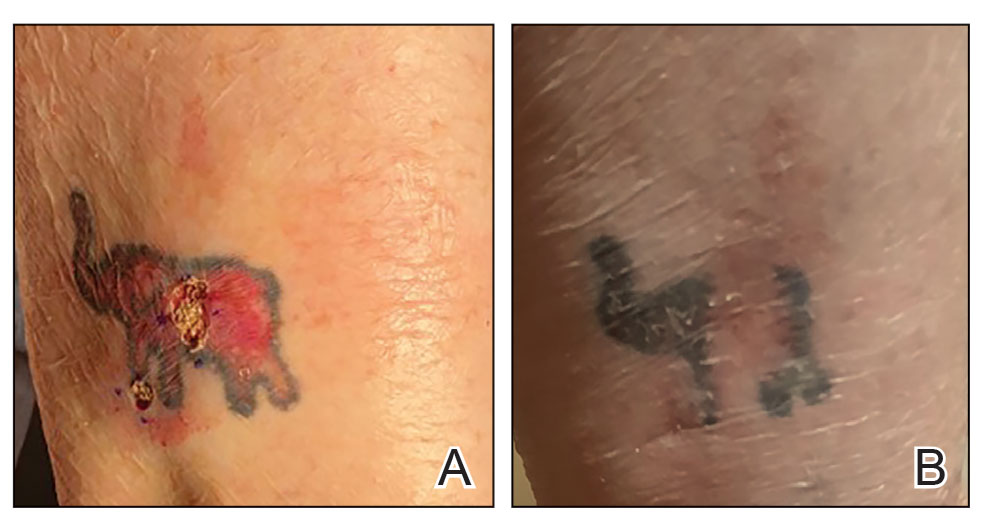

In these clinical scenarios, patients may be hesitant to pursue surgical treatment due to concerns that it may alter tattoo appearance. Many clinicians and surgeons may consider definitive treatment and tattoo preservation to be mutually exclusive, but this is not always the case. We propose a technique that utilizes conservative thickness layers (CTL) to minimize disruption to the appearance of tattoos in MMS for treatment of cutaneous malignancies as well as intradermal excision of tattoo pigment in the setting of chronic inflammatory tattoo reactions.

The Technique

In the appropriate clinical context, CTL can effectively result in defects that heal well by secondary intention and minimize collateral tissue distortion.4 Lesions manifesting in or near tattooed skin often are responsive to treatment with CTL; furthermore, CTL may preserve some deeper tattoo pigment, resulting in only partial loss of the tattooed skin.

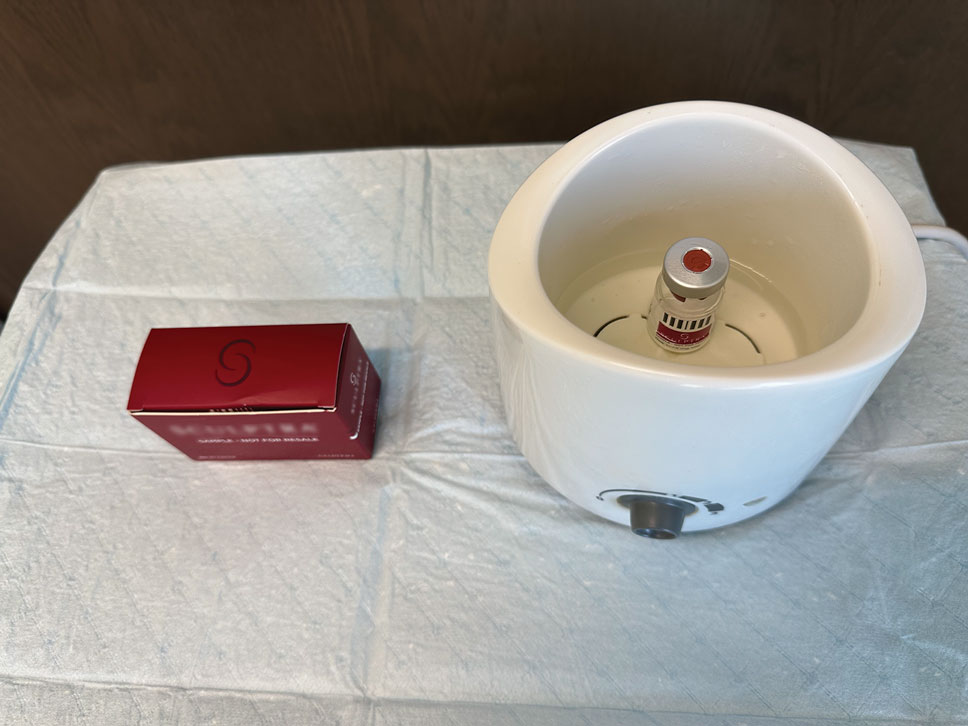

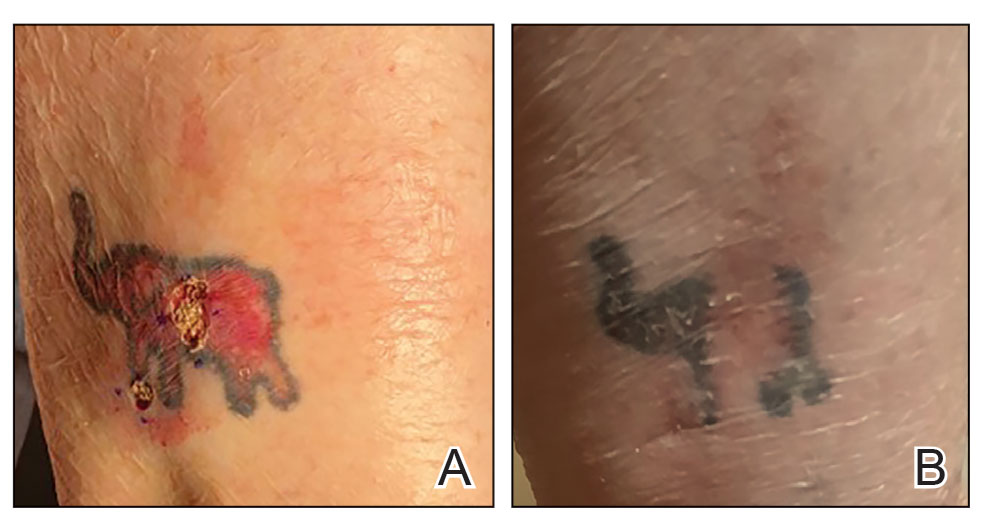

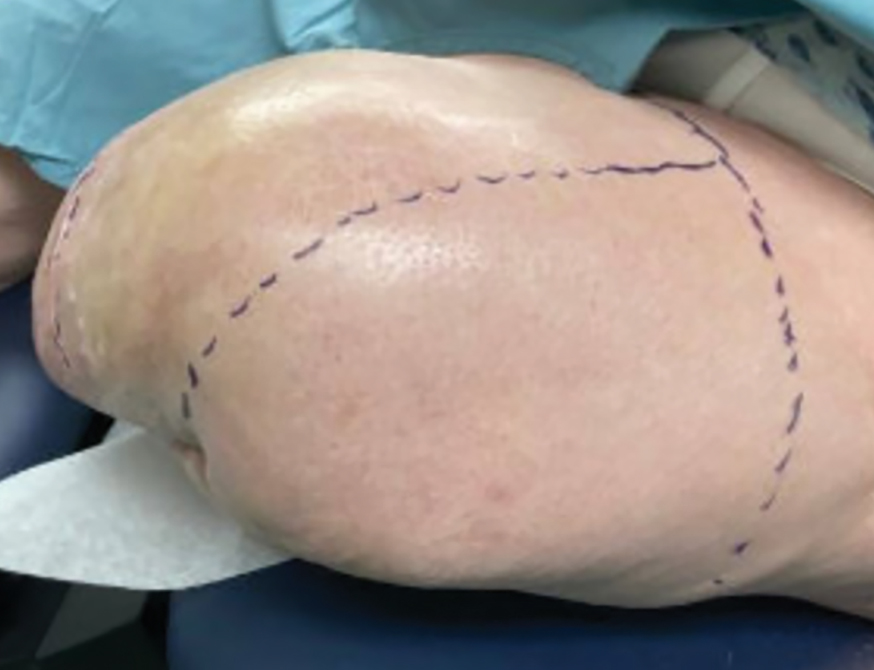

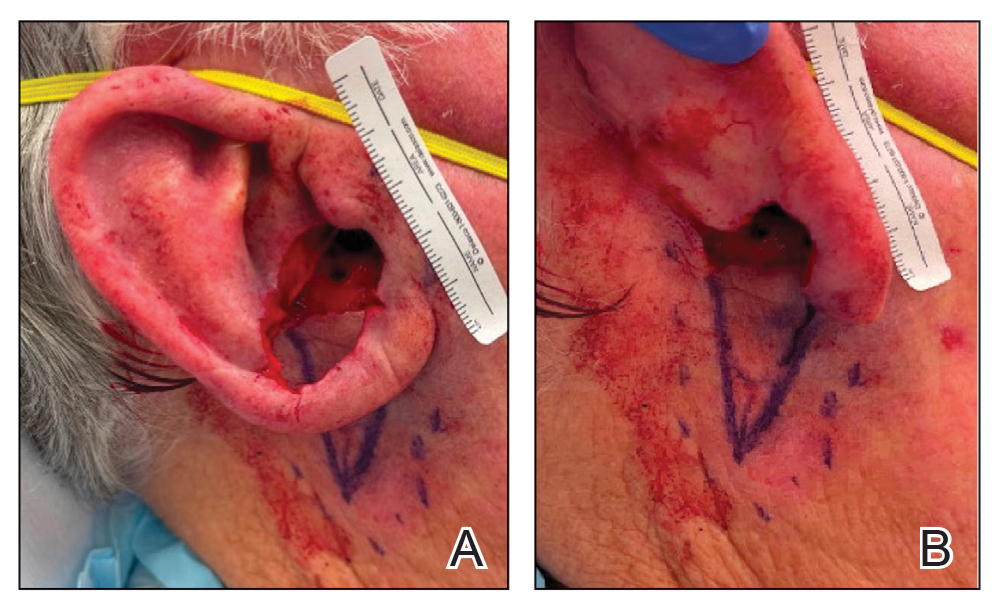

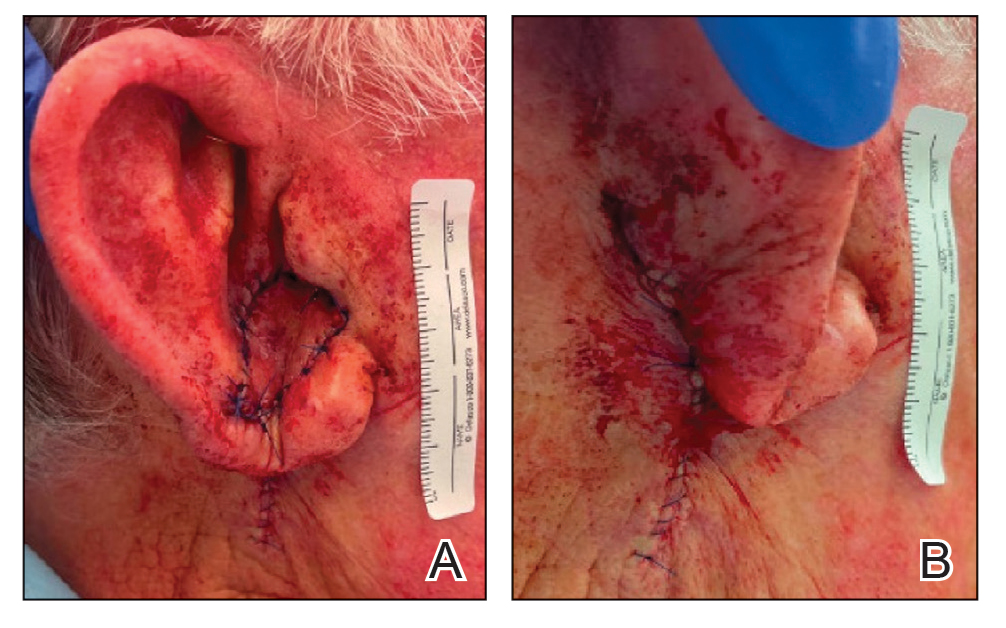

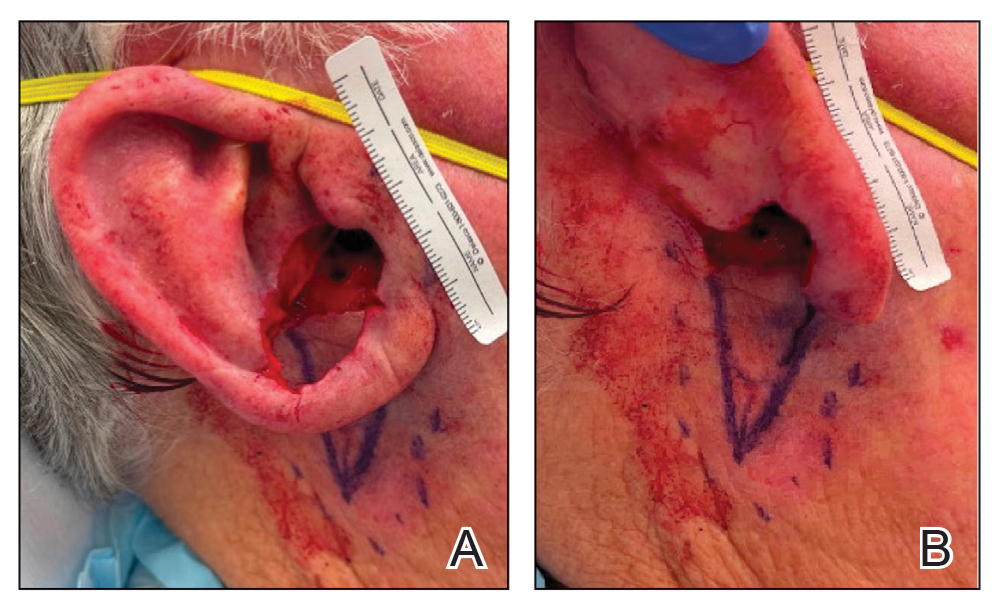

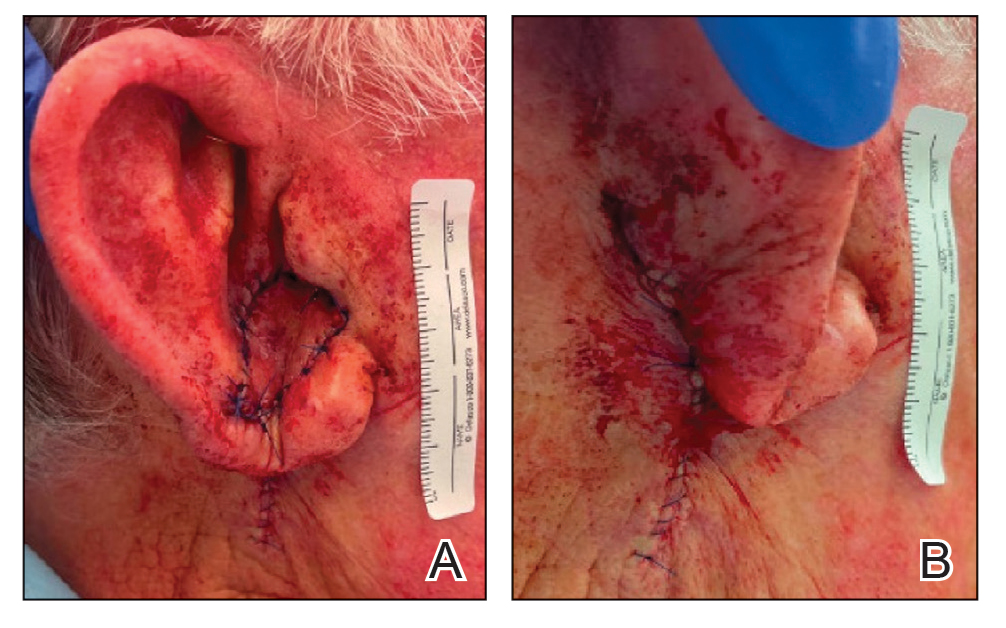

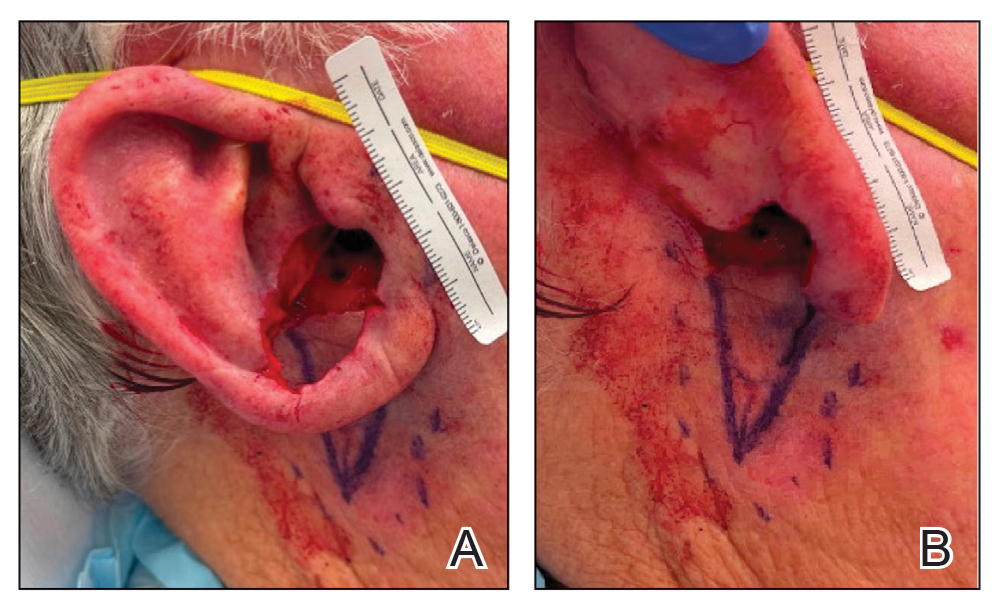

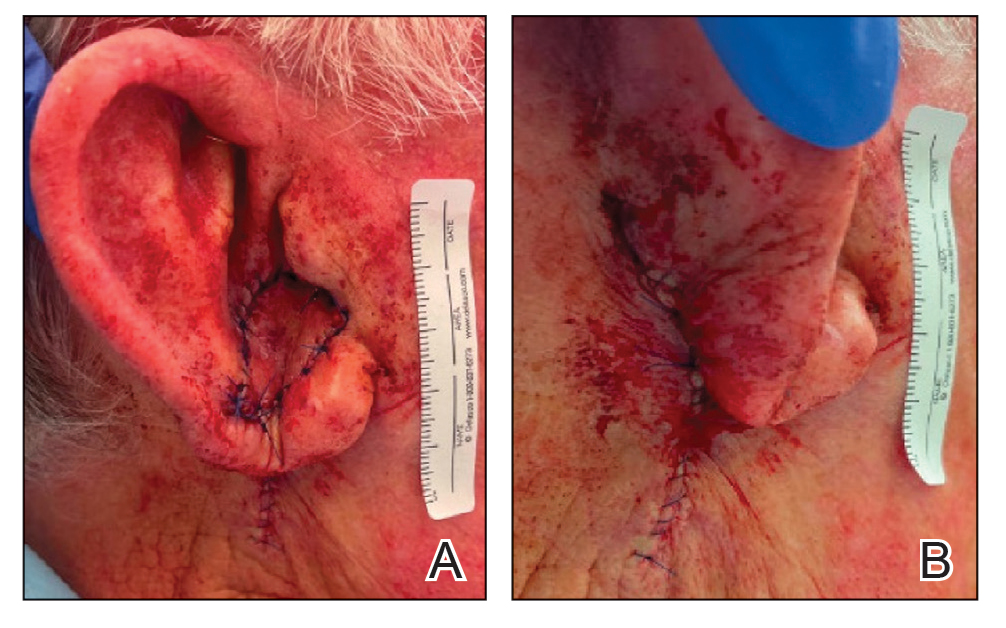

Conservative thickness layers are performed intradermally, similar to removing traditional layers in MMS. For treatment of NMSCs, a margin is scored around the lesion, and then the blade is passed carefully under the lesion nearly parallel to the skin through an intradermal plane. It is important to avoid entering the subcuticular fat (Figure 1). The tissue then is processed normally in the Mohs laboratory for complete circumferential margin evaluation. If necessary and possible, subsequent layers also can be performed in the intradermal plane. Once total circumferential margin control is obtained, the wound is allowed to granulate and heal by secondary intention. As these processes occur, we have found that wound contraction is less likely with the dermis intact, resulting in less impact on the overall appearance of the tattoo (Figures 1 and 2). For very thin lesions, resultant defects may retain some residual tattoo pigment. The residual scars also may be responsive to tattoo revision, although a period of monitoring for recurrence should be considered if there is concern that revising the tattoo could obscure early recurrent tumors. From our experience, utilizing CTL for NMSCs that arise within or near tattoos results in favorable preservation of the tattoo appearance and high patient satisfaction.

The procedure is performed similarly for removal of allergenic tattoo pigment, with careful excision to the mid dermis. Since the areas affected by the cutaneous reaction may be relatively large, surgical precision is required to maintain a uniform depth to remove the tattoo pigment and preserve the deep dermis (Figure 2). Once removed, the defect can be left to granulate and heal by secondary intention. If the patient wants to have the tattoo revised in the future, it would be prudent to utilize pigment that the patient has responded favorably to. In our experience, this approach is effective and yields high patient satisfaction and minimizes morbidity.

Practice Implications

Tattoos often hold special meaning for patients; therefore, treatment of pathologies arising in or near tattooed skin should emphasize maintaining the appearance of the tattoo while still being effective. Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions for allergic reactions to tattoo pigment are an effective treatment strategy that clinicians may consider.

One shortcoming of using CTL for MMS is the need for subsequent layers to clear the tumor; however, data suggest that first-stage cure rates are extremely high even with CTL for appropriately selected patients, with clearance of nearly 80% of tumors on the first stage. Tumors that may be most responsive to CTL include exophytic NMSCs and those arising in areas with a thicker dermis, including the back, legs, and scalp, although other locations including the face, hands, shins, ankles, and feet also may be well suited for CTL.4 Another shortcoming of CTL is that skin cancers arising in tattoos may not be considered appropriate for MMS based on the 2012

Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions of tattoo pigment are both effective techniques of minimizing disruption of tattoos while effectively treating patients.

- Roggenkamp H, Nicholls A, Pierre JM. Tattoos as a window to the psyche: how talking about skin art can inform psychiatric practice. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7:148-158. doi:10.5498/wjp.v7.i3.148

- Rubatto M, Gelato F, Mastorino L, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer arising on tattoos. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E155-E156. doi:10.1111/ijd.16381

- Atwater AR, Bembry R, Reeder M. Tattoo hypersensitivity reactions: inky business. Cutis. 2020;106:64-67. doi:10.12788/cutis.0028

- Tolkachjov SN, Cappel JA, Bryant EA, et al. Conservative thickness layers in Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1128-1134. doi:10.1111/ijd.14043

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.155068

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009.

- Amthor Croley JA. Current controversies in mohs micrographic surgery. Cutis. 2019;104:E29-E31.

Practice Gap

Tattoos have become increasingly prevalent in Western culture, with approximately 1 in 4 Americans having at least 1 tattoo. Individuals invest money, time, and even pain in getting tattoos, many of which hold special personal, family, or religious significance.1 Various cutaneous pathologies may arise in areas of the skin with tattoos, including malignancies and inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigment, and in these cases, surgical management may be indicated.2,3

Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) such as superficial basal cell carcinomas on broadly sun-damaged areas (eg, trunk, torso), squamous cell carcinomas, reactive keratoacanthomas, and reactive pseudoepitheliomatous squamous hyperplasia diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma have been reported to occur in or near areas of the skin with tattoos.2 Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is the standard of care for removing NMSCs, particularly when they manifest in cosmetically sensitive areas.4 This treatment option allows for careful guided resection of tumors to minimize the risk for recurrence; it also preserves healthy tissue, which typically results in a smaller radial defect after the procedure is complete.

Chronic reactions to tattoo pigment may include granulomatous tattoo reactions and pseudolymphomas.3 Treatment options may include immunosuppressives such as intralesional triamcinolone as well as pigment destruction via lasers5; however, not all tattoos are responsive to these treatments. Surgical excision is an effective and definitive treatment in this context, as tattoo pigment resides in or above the mid dermis to a depth of approximately 400 μm. Intradermal excision effectively removes the antigenic pigment.5

In these clinical scenarios, patients may be hesitant to pursue surgical treatment due to concerns that it may alter tattoo appearance. Many clinicians and surgeons may consider definitive treatment and tattoo preservation to be mutually exclusive, but this is not always the case. We propose a technique that utilizes conservative thickness layers (CTL) to minimize disruption to the appearance of tattoos in MMS for treatment of cutaneous malignancies as well as intradermal excision of tattoo pigment in the setting of chronic inflammatory tattoo reactions.

The Technique

In the appropriate clinical context, CTL can effectively result in defects that heal well by secondary intention and minimize collateral tissue distortion.4 Lesions manifesting in or near tattooed skin often are responsive to treatment with CTL; furthermore, CTL may preserve some deeper tattoo pigment, resulting in only partial loss of the tattooed skin.

Conservative thickness layers are performed intradermally, similar to removing traditional layers in MMS. For treatment of NMSCs, a margin is scored around the lesion, and then the blade is passed carefully under the lesion nearly parallel to the skin through an intradermal plane. It is important to avoid entering the subcuticular fat (Figure 1). The tissue then is processed normally in the Mohs laboratory for complete circumferential margin evaluation. If necessary and possible, subsequent layers also can be performed in the intradermal plane. Once total circumferential margin control is obtained, the wound is allowed to granulate and heal by secondary intention. As these processes occur, we have found that wound contraction is less likely with the dermis intact, resulting in less impact on the overall appearance of the tattoo (Figures 1 and 2). For very thin lesions, resultant defects may retain some residual tattoo pigment. The residual scars also may be responsive to tattoo revision, although a period of monitoring for recurrence should be considered if there is concern that revising the tattoo could obscure early recurrent tumors. From our experience, utilizing CTL for NMSCs that arise within or near tattoos results in favorable preservation of the tattoo appearance and high patient satisfaction.

The procedure is performed similarly for removal of allergenic tattoo pigment, with careful excision to the mid dermis. Since the areas affected by the cutaneous reaction may be relatively large, surgical precision is required to maintain a uniform depth to remove the tattoo pigment and preserve the deep dermis (Figure 2). Once removed, the defect can be left to granulate and heal by secondary intention. If the patient wants to have the tattoo revised in the future, it would be prudent to utilize pigment that the patient has responded favorably to. In our experience, this approach is effective and yields high patient satisfaction and minimizes morbidity.

Practice Implications

Tattoos often hold special meaning for patients; therefore, treatment of pathologies arising in or near tattooed skin should emphasize maintaining the appearance of the tattoo while still being effective. Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions for allergic reactions to tattoo pigment are an effective treatment strategy that clinicians may consider.

One shortcoming of using CTL for MMS is the need for subsequent layers to clear the tumor; however, data suggest that first-stage cure rates are extremely high even with CTL for appropriately selected patients, with clearance of nearly 80% of tumors on the first stage. Tumors that may be most responsive to CTL include exophytic NMSCs and those arising in areas with a thicker dermis, including the back, legs, and scalp, although other locations including the face, hands, shins, ankles, and feet also may be well suited for CTL.4 Another shortcoming of CTL is that skin cancers arising in tattoos may not be considered appropriate for MMS based on the 2012

Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions of tattoo pigment are both effective techniques of minimizing disruption of tattoos while effectively treating patients.

Practice Gap

Tattoos have become increasingly prevalent in Western culture, with approximately 1 in 4 Americans having at least 1 tattoo. Individuals invest money, time, and even pain in getting tattoos, many of which hold special personal, family, or religious significance.1 Various cutaneous pathologies may arise in areas of the skin with tattoos, including malignancies and inflammatory reactions to tattoo pigment, and in these cases, surgical management may be indicated.2,3

Nonmelanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) such as superficial basal cell carcinomas on broadly sun-damaged areas (eg, trunk, torso), squamous cell carcinomas, reactive keratoacanthomas, and reactive pseudoepitheliomatous squamous hyperplasia diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma have been reported to occur in or near areas of the skin with tattoos.2 Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is the standard of care for removing NMSCs, particularly when they manifest in cosmetically sensitive areas.4 This treatment option allows for careful guided resection of tumors to minimize the risk for recurrence; it also preserves healthy tissue, which typically results in a smaller radial defect after the procedure is complete.

Chronic reactions to tattoo pigment may include granulomatous tattoo reactions and pseudolymphomas.3 Treatment options may include immunosuppressives such as intralesional triamcinolone as well as pigment destruction via lasers5; however, not all tattoos are responsive to these treatments. Surgical excision is an effective and definitive treatment in this context, as tattoo pigment resides in or above the mid dermis to a depth of approximately 400 μm. Intradermal excision effectively removes the antigenic pigment.5

In these clinical scenarios, patients may be hesitant to pursue surgical treatment due to concerns that it may alter tattoo appearance. Many clinicians and surgeons may consider definitive treatment and tattoo preservation to be mutually exclusive, but this is not always the case. We propose a technique that utilizes conservative thickness layers (CTL) to minimize disruption to the appearance of tattoos in MMS for treatment of cutaneous malignancies as well as intradermal excision of tattoo pigment in the setting of chronic inflammatory tattoo reactions.

The Technique

In the appropriate clinical context, CTL can effectively result in defects that heal well by secondary intention and minimize collateral tissue distortion.4 Lesions manifesting in or near tattooed skin often are responsive to treatment with CTL; furthermore, CTL may preserve some deeper tattoo pigment, resulting in only partial loss of the tattooed skin.

Conservative thickness layers are performed intradermally, similar to removing traditional layers in MMS. For treatment of NMSCs, a margin is scored around the lesion, and then the blade is passed carefully under the lesion nearly parallel to the skin through an intradermal plane. It is important to avoid entering the subcuticular fat (Figure 1). The tissue then is processed normally in the Mohs laboratory for complete circumferential margin evaluation. If necessary and possible, subsequent layers also can be performed in the intradermal plane. Once total circumferential margin control is obtained, the wound is allowed to granulate and heal by secondary intention. As these processes occur, we have found that wound contraction is less likely with the dermis intact, resulting in less impact on the overall appearance of the tattoo (Figures 1 and 2). For very thin lesions, resultant defects may retain some residual tattoo pigment. The residual scars also may be responsive to tattoo revision, although a period of monitoring for recurrence should be considered if there is concern that revising the tattoo could obscure early recurrent tumors. From our experience, utilizing CTL for NMSCs that arise within or near tattoos results in favorable preservation of the tattoo appearance and high patient satisfaction.

The procedure is performed similarly for removal of allergenic tattoo pigment, with careful excision to the mid dermis. Since the areas affected by the cutaneous reaction may be relatively large, surgical precision is required to maintain a uniform depth to remove the tattoo pigment and preserve the deep dermis (Figure 2). Once removed, the defect can be left to granulate and heal by secondary intention. If the patient wants to have the tattoo revised in the future, it would be prudent to utilize pigment that the patient has responded favorably to. In our experience, this approach is effective and yields high patient satisfaction and minimizes morbidity.

Practice Implications

Tattoos often hold special meaning for patients; therefore, treatment of pathologies arising in or near tattooed skin should emphasize maintaining the appearance of the tattoo while still being effective. Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions for allergic reactions to tattoo pigment are an effective treatment strategy that clinicians may consider.

One shortcoming of using CTL for MMS is the need for subsequent layers to clear the tumor; however, data suggest that first-stage cure rates are extremely high even with CTL for appropriately selected patients, with clearance of nearly 80% of tumors on the first stage. Tumors that may be most responsive to CTL include exophytic NMSCs and those arising in areas with a thicker dermis, including the back, legs, and scalp, although other locations including the face, hands, shins, ankles, and feet also may be well suited for CTL.4 Another shortcoming of CTL is that skin cancers arising in tattoos may not be considered appropriate for MMS based on the 2012

Conservative thickness layers in MMS and intradermal excisions of tattoo pigment are both effective techniques of minimizing disruption of tattoos while effectively treating patients.

- Roggenkamp H, Nicholls A, Pierre JM. Tattoos as a window to the psyche: how talking about skin art can inform psychiatric practice. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7:148-158. doi:10.5498/wjp.v7.i3.148

- Rubatto M, Gelato F, Mastorino L, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer arising on tattoos. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E155-E156. doi:10.1111/ijd.16381

- Atwater AR, Bembry R, Reeder M. Tattoo hypersensitivity reactions: inky business. Cutis. 2020;106:64-67. doi:10.12788/cutis.0028

- Tolkachjov SN, Cappel JA, Bryant EA, et al. Conservative thickness layers in Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1128-1134. doi:10.1111/ijd.14043

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.155068

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009.

- Amthor Croley JA. Current controversies in mohs micrographic surgery. Cutis. 2019;104:E29-E31.

- Roggenkamp H, Nicholls A, Pierre JM. Tattoos as a window to the psyche: how talking about skin art can inform psychiatric practice. World J Psychiatry. 2017;7:148-158. doi:10.5498/wjp.v7.i3.148

- Rubatto M, Gelato F, Mastorino L, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer arising on tattoos. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:E155-E156. doi:10.1111/ijd.16381

- Atwater AR, Bembry R, Reeder M. Tattoo hypersensitivity reactions: inky business. Cutis. 2020;106:64-67. doi:10.12788/cutis.0028

- Tolkachjov SN, Cappel JA, Bryant EA, et al. Conservative thickness layers in Mohs micrographic surgery. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:1128-1134. doi:10.1111/ijd.14043

- Sardana K, Ranjan R, Ghunawat S. Optimising laser tattoo removal. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2015;8:16-24. doi:10.4103/0974-2077.155068

- Connolly SM, Baker DR, Coldiron BM, et al. AAD/ACMS/ASDSA/ASMS 2012 appropriate use criteria for Mohs micrographic surgery: a report of the American Academy of Dermatology, American College of Mohs Surgery, American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:531-550. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.009.

- Amthor Croley JA. Current controversies in mohs micrographic surgery. Cutis. 2019;104:E29-E31.

Conservative Thickness Layers to Preserve Tattoo Appearance During Excisional Procedures

Conservative Thickness Layers to Preserve Tattoo Appearance During Excisional Procedures

Botulinum Toxin as a Tool to Reduce Hyperhidrosis in Amputees

Botulinum Toxin as a Tool to Reduce Hyperhidrosis in Amputees

Practice Gap

Hyperhidrosis poses a considerable challenge for many amputees who use prosthetic devices, particularly at the interface between the residual limb and the prosthetic socket. The enclosed environment of the socket often leads to excessive sweating, which can compromise suction fit and increase the risk for skin chafing, irritation, and slippage. Persistent moisture also promotes bacterial and fungal growth, raising the likelihood of infections and foul odors within the socket. Research has shown that skin complications are highly prevalent among amputees, affecting up to 73.9% of this population in the United States.1 Commonly reported complications include wounds, abscesses, and blisters, many of which can be triggered or worsened by hyperhidrosis.2 Current treatment options for residual limb sweating include topical antiperspirants, botulinum toxin (BTX) injections, iontophoresis, and liner-liner socks.

While BTX commonly is used to treat hyperhidrosis in areas such as the palms and axillae, it typically is not considered as a first-line therapy for residual limb sweating; however, both BTX type A and type B have shown safety and effectiveness in managing hyperhidrosis in amputees, enhancing prosthetic use, and improving overall quality of life.3 Despite these benefits, BTX remains relatively underutilized for

Tools and Techniques

A 64-year-old man initially presented to our dermatology clinic after undergoing an above-the-knee amputation of the left leg 1 year prior. The amputation had been performed due to chronic prosthetic joint infections with Escherichia coli. He reported persistent sweating of the residual limb, which severely limited his use of a prosthesis and led to frequent falls.

During the initial visit, treatment options for primary hyperhidrosis including topical and injectable therapies were discussed. Due to a fear of needles, the patient chose topical treatment, with the option to pursue BTX injections later if better control was needed. An aluminum chloride hexahydrate prosthetic antiperspirant was prescribed for nightly application on the anterior and posterior

Botulinum toxin injections were administered in a grid-like pattern across the surface area where the residual limb made contact with the prosthetic. Using a surgical marker, the patient assisted the medical team in identifying the areas where sweating occurred most frequently. The area was divided into 4 equal sections, with each section treated per weekly interval sequentially over 4 weeks. The targeted areas included the left anterior (extending from the anterior tensor fasciae latae band to the lateral thigh) and left posterior residual limb (Figure 1 and eFigure 1, respectively).

The treated section was cleaned with an alcohol wipe prior to each injection, and 50 units of BTX (diluted to 2.5 units per 0.1 mL in bacteriostatic saline) were injected intradermally into each section (Figure 2 and eFigure 2). The injections were administered in rows, with the needle inserted at evenly spaced intervals approximately 1 inch apart. A total of 100 units were administered per section at each weekly appointment. The patient tolerated the procedure well, and no complications were observed.

Practice Implications

This staged approach to administering BTX ensures even distribution of the injections, optimizes hyperhidrosis control, minimizes the risk for complications, and allows for precise targeting of the affected areas to maximize therapeutic benefit. Following the initial procedure, our patient was scheduled for follow-ups approximately every 3 to 4 months starting from the first set of injections for each area. Over 9 months, the patient successfully completed 3 treatment sessions using this method. The patient reported improved quality of life after starting the BTX injections.

After evaluating the initial treatment outcomes with 100 units per section, the dosage was increased to 200 units per section to reduce the number of visits from 4 every 3 months to cover the entire area to 2 visits every 3 months. This adjustment aimed to optimize results and better manage the patient’s ongoing symptoms. At about 1 to 2 weeks after beginning treatment, the patient noticed decreased sweating and discomfort during his daily activities and reduced friction with his prosthetic leg. No adverse effects were noted with the increased dosage during a clinical visit.

Our case highlights the importance of ensuring equitable access to hyperhidrosis treatment. Dermatologists should prioritize patient-centered care by factoring in financial constraints when recommending therapies. In this patient’s case, offering a range of options including over-the-counter antiperspirants and prescription treatments allowed for a management plan tailored to his individual needs and circumstances.

DaxibotulinumtoxinA, known for its longer duration of action compared to other BTX formulations, presents a promising alternative for treating hyperhidrosis.4 However, a gap in care emerged for our patient when prescription antiperspirant was not covered by his insurance, and daxibotulinumtoxinA, which could have offered a more durable solution, was not yet available at our clinic for hyperhidrosis management. Expanding insurance coverage for effective prescription treatments and improving access to newer treatment options are crucial for enhancing patient outcomes and ensuring more equitable care.

Focusing dermatologic care on amputees presents distinct challenges and opportunities for improving their care and decreasing discomfort. Amputees, particularly those with residual limb hyperhidrosis, often experience additional discomfort and difficulty while using prosthetics, as excessive sweating can interfere with fit and function.5,6 Dermatologists should proactively address these specific needs by tailoring treatment accordingly. Incorporating targeted therapies, such as BTX injections, in addition to education on lifestyle modifications and managing treatment expectations, ensures comprehensive care that enhances both quality of life and functional outcomes. Engaging patients in discussions about all available options, including emerging therapies, is essential for improving care for this underserved population.

- Koc E, Tunca M, Akar A, et al. Skin problems in amputees: a descriptive study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:463–466. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2008.03604.x

- Bui KM, Raugi GJ, Nguyen VQ, et al. Skin problems in individuals with lower-limb loss: literature review and proposed classification system. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46:1085-1090. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.04.0052

- Rocha Melo J, Rodrigues MA, Caetano M, et al. Botulinum toxin in the treatment of residual limb hyperhidrosis: a systematic review. Rehabilitacion (Madr). 2023;57:100754. doi:10.1016/j.rh.2022.07.003

- Hansen C, Godfrey B, Wixom J, et al. Incidence, severity, and impact of hyperhidrosis in people with lower-limb amputation. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2015;52:31-40. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.04.0108

- Lannan FM, Powell J, Kim GM, et al. Hyperhidrosis of the residual limb: a narrative review of the measurement and treatment of excess perspiration affecting individuals with amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2021;45:477-486. doi:10.1097/PXR.0000000000000040

- Pace S, Kentosh J. Managing residual limb hyperhidrosis in wounded warriors. Cutis. 2016;97:401-403.

Practice Gap

Hyperhidrosis poses a considerable challenge for many amputees who use prosthetic devices, particularly at the interface between the residual limb and the prosthetic socket. The enclosed environment of the socket often leads to excessive sweating, which can compromise suction fit and increase the risk for skin chafing, irritation, and slippage. Persistent moisture also promotes bacterial and fungal growth, raising the likelihood of infections and foul odors within the socket. Research has shown that skin complications are highly prevalent among amputees, affecting up to 73.9% of this population in the United States.1 Commonly reported complications include wounds, abscesses, and blisters, many of which can be triggered or worsened by hyperhidrosis.2 Current treatment options for residual limb sweating include topical antiperspirants, botulinum toxin (BTX) injections, iontophoresis, and liner-liner socks.

While BTX commonly is used to treat hyperhidrosis in areas such as the palms and axillae, it typically is not considered as a first-line therapy for residual limb sweating; however, both BTX type A and type B have shown safety and effectiveness in managing hyperhidrosis in amputees, enhancing prosthetic use, and improving overall quality of life.3 Despite these benefits, BTX remains relatively underutilized for

Tools and Techniques

A 64-year-old man initially presented to our dermatology clinic after undergoing an above-the-knee amputation of the left leg 1 year prior. The amputation had been performed due to chronic prosthetic joint infections with Escherichia coli. He reported persistent sweating of the residual limb, which severely limited his use of a prosthesis and led to frequent falls.

During the initial visit, treatment options for primary hyperhidrosis including topical and injectable therapies were discussed. Due to a fear of needles, the patient chose topical treatment, with the option to pursue BTX injections later if better control was needed. An aluminum chloride hexahydrate prosthetic antiperspirant was prescribed for nightly application on the anterior and posterior

Botulinum toxin injections were administered in a grid-like pattern across the surface area where the residual limb made contact with the prosthetic. Using a surgical marker, the patient assisted the medical team in identifying the areas where sweating occurred most frequently. The area was divided into 4 equal sections, with each section treated per weekly interval sequentially over 4 weeks. The targeted areas included the left anterior (extending from the anterior tensor fasciae latae band to the lateral thigh) and left posterior residual limb (Figure 1 and eFigure 1, respectively).