User login

Are Text Pages an Effective Nudge to Increase Attendance at Internal Medicine Morning Report Conferences? A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

Regularly scheduled educational conferences, such as case-based morning reports, have been a standard part of internal medicine residencies for decades.1-4 In addition to better patient care from the knowledge gained at educational conferences, attendance by interns and residents (collectively called house staff) may be associated with higher in-service examination scores.5 Unfortunately, competing priorities, including patient care and trainee supervision, may contribute to an action-intention gap among house staff that reduces attendance.6-8 Low attendance at morning reports represents wasted effort and lost educational opportunities; therefore, strategies to increase attendance are needed. Of several methods studied, more resource-intensive interventions (eg, providing food) were the most successful.6,9-12

Using the behavioral economics framework of nudge strategies, we hypothesized that a less intensive intervention of a daily reminder text page would encourage medical students, interns, and residents (collectively called learners) to attend the morning report conference.8,13 However, given the high cognitive load created by frequent task switching, a reminder text page could disrupt workflow and patient care without promoting the intended behavior change.14-17 Because of this uncertainty, our objective was to determine whether a preconference text page increased learner attendance at morning report conferences.

Methods

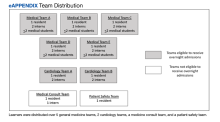

This study was a single-center, multiple-crossover cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at the Veteran Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts. Study participants included house staff rotating on daytime inpatient rotations from 4 residency programs and students from 2 medical schools. The setting was the morning report, an in-person, interactive, case-based conference held Monday through Thursday, from 8:00

Learners assigned to rotate on the inpatient medicine, cardiology, medicine consultation, and patient safety rotations were eligible to attend these conferences and for inclusion in the study. Learners rotating in the medical intensive care unit, on night float, or on day float (an admitting shift for which residents are not on-site until late afternoon) were excluded. Additional details of the study population are available in the supplement (eAppendix). The study period was originally planned for September 30, 2019, to March 31, 2020, but data collection was stopped on March 12, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and suspension of in-person conferences. We chose the study period, which determined our sample size, to exclude the first 3 months of the academic year (July-September) because during that time learners acclimate to the inpatient workflow. We also chose not to include the last 3 months of the academic year to provide time for data analysis and preparation of the manuscript within the academic year.

Intervention and Outcome Assessment

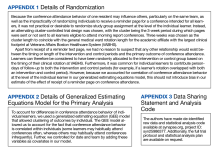

Each intervention and control period was 3 weeks long; the first period was randomly determined by coin flip and alternated thereafter. Additional details of randomization are available in the supplement (Appendix 1). During intervention periods, all house staff received a page at 7:55

A daily facesheet (a roster of house staff names and photos) was used to identify learners for conference attendance. This facesheet was already used for other purposes at VABHS. At 8:00

During control periods, no text page reminder of upcoming conferences was sent, but the attendance of total learners at 8:00

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the proportion of eligible learners present at 8:10

To estimate the primary outcome, we modeled the risk difference adjusted for covariates using a generalized estimating equation accounting for the clustering of attendance behavior within individuals and controlling for date and team. Secondary outcomes were estimated similarly. To evaluate the robustness of the primary outcome, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a multilevel generalized linear model with clustering by individual learner and team. Additional details on our statistical analysis plan, including accessing our raw data and analysis code, are available in Appendices 2 and 3. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. All P values were 2-sided, and a significance level of ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed in Stata v16.1. Our study was deemed exempt by the VABHS Institutional Review Board, and this article was prepared following the CONSORT reporting guidelines. The trial protocol has been registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number registry

Results

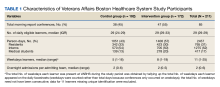

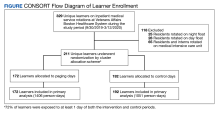

Over the study period, 329 unique learners rotated on inpatient medical services at the VABHS and 211 were eligible to attend 85 morning report conferences and 22 Jeopardy conferences (Figure). Outcomes data were available for 100% of eligible participants. Forty-seven (55%) of the morning report conferences occurred during the intervention period (Table 1).

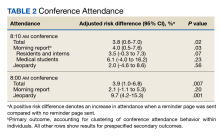

Morning report attendance observed at 8:10

On-time attendance was lower than at 8:10

To estimate the impact of rotating on teams with lighter clinical workloads on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we repeated our primary analysis with a test of interaction between team assignment and the intervention, which was not significant (P = .90). To estimate the impact of morning workload on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we performed a subgroup analysis limited to learners rotating on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and included the number of overnight admissions as a covariate in our regression model. A test of interaction between the intervention and the number of overnight admissions on conference attendance was not significant (P = .73).

In a subgroup analysis limited to learners on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and controlling for the number of overnight admissions (a proxy for morning workload), no significant interaction between the intervention and admissions was observed. We also assessed for interaction between learner type and receipt of a reminder page on conference attendance and found no evidence of such an effect.

Discussion

Among a diverse population of learners from multiple academic institutions rotating at a single, large, urban VA medical center, a nudge strategy of sending a reminder text page before morning report conferences was associated with a 4.0% absolute increase in attendance measured 10 minutes after the conference started compared with not sending a reminder page. Overall, only one-quarter of learners attended the morning report at the start at 8:00

We designed our analysis to overcome several limitations of prior studies on the effect of reminder text pages on conference attendance. First, to account for differences in conference attendance behavior of individual learners, we used a generalized estimating equation model that allowed clustering of outcomes by individual. Second, we controlled for the date to account for secular trends in conference attendance over the academic year. Finally, we controlled for the team to account for the possibility that the conference attendance behavior of one learner on a team influences the behavior of other learners on the same team.

We also evaluated the effect of a reminder page on attendance at a weekly Jeopardy conference. Interestingly, reminder pages seemed to increase on-time Jeopardy attendance, although this effect was no longer statistically significant at 8:10

We also assessed the interaction between sending a reminder page and learner type and its effect on conference attendance and found no evidence to support such an effect. Because medical students do not receive reminder pages, their conference attendance behavior can be thought of as indicative of clustering within teams. Though there was no evidence of a significant interaction, given the small number of students, our study may be underpowered to find a benefit for this group.

The results of this study differ from Smith and colleagues, who found that reminder pages had no overall effect on conference attendance for fellows; however, no sample size justification was provided in that study, making it difficult to evaluate the likelihood of a false-negative finding.7 Our study differs in several ways: the timing of the reminder page (5 minutes vs 30 minutes prior to the conference), the method by which attendance was recorded (by an independent observer vs learner sign-in), and the time that attendance was recorded (2 prespecified times vs continuously). As far as we know, our study is the first to evaluate the nudge effect of reminder text pages on internal medicine resident attendance at conferences, with attendance taken by an observer.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it was conducted at a single VA medical center. An additional limitation was our decision to classify learners who arrived after 8:10

Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the suspension of in-person conferences, our study ended earlier than anticipated. This resulted in an imbalance of morning report conferences that occurred during each period: 55% during the intervention period, and 45% during the control period. However, because we accounted for the clustering of conference attendance behavior within individuals in our model, this imbalance is unlikely to introduce bias in our estimation of the effect of the intervention.

Another limitation relates to the evolving landscape of educational conferences in the postpandemic era.18 Whether our results can be generalized to increase virtual conference attendance is unknown. Finally, it is not clear whether a 4% absolute increase in conference attendance is educationally meaningful or justifies the effort of sending a reminder page.

Conclusions

In this cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at a single VA medical center, reminder pages sent 5 minutes before the start of morning report conferences resulted in a 4% increase in conference attendance. Our results suggest that reminder pages are one strategy that may result in a small increase in conference attendance, but whether this small increase is educationally significant will vary across training programs applying this strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Kenneth J. Mukamal and Katharine A. Robb, who provided invaluable guidance in data analysis. Todd Reese assisted in data organization and presentation of data, and Mark Tuttle designed the facesheet. None of these individuals received compensation for their assistance.

1. Daniels VJ, Goldstein CE. Changing morning report: an educational intervention to address curricular needs. J Biomed Educ. 2014;2014:1-5. doi:10.1155/2014/830701

2. Parrino TA, Villanueva AG. The principles and practice of morning report. JAMA. 1986;256(6):730-733. doi:10.1001/jama.1986.03380060056025

3. Wenger NS, Shpiner RB. An analysis of morning report: implications for internal medicine education. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(5):395-399. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-5-199309010-00008

4. Ways M, Kroenke K, Umali J, Buchwald D. Morning report. A survey of resident attitudes. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(13):1433-1437. doi:10.1001/archinte.155.13.1433

5. McDonald FS, Zeger SL, Kolars JC. Associations of conference attendance with internal medicine in-training examination scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(4):449-453. doi:10.4065/83.4.449

6. FitzGerald JD, Wenger NS. Didactic teaching conferences for IM residents: who attends, and is attendance related to medical certifying examination scores? Acad Med. 2003;78(1):84-89. doi:10.1097/00001888-200301000-00015

7. Smith J, Zaffiri L, Clary J, Davis T, Bosslet GT. The effect of paging reminders on fellowship conference attendance: a multi-program randomized crossover study. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):372-377. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00487.1

8. Sheeran P, Webb TL. The intention-behavior gap. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2016;10(9):503-518. doi:10.1111/spc3.12265

9. McDonald RJ, Luetmer PH, Kallmes DF. If you starve them, will they still come? Do complementary food provisions affect faculty meeting attendance in academic radiology? J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8(11):809-810. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.06.003

10. Segovis CM, Mueller PS, Rethlefsen ML, et al. If you feed them, they will come: a prospective study of the effects of complimentary food on attendance and physician attitudes at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:22. Published 2007 Jul 12. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-7-22

11. Mueller PS, Litin SC, Sowden ML, Habermann TM, LaRusso NF. Strategies for improving attendance at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(5):549-553. doi:10.4065/78.5.549

12. Tarabichi S, DeLeon M, Krumrei N, Hanna J, Maloney Patel N. Competition as a means for improving academic scores and attendance at education conference. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):1437-1440. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.04.020

13. Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Rev. and Expanded Ed. Penguin Books; 2009.

14. Weijers RJ, de Koning BB, Paas F. Nudging in education: from theory towards guidelines for successful implementation. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2021;36:883-902. Published 2020 Aug 24. doi:10.1007/s10212-020-00495-0

15. Wieland ML, Loertscher LL, Nelson DR, Szostek JH, Ficalora RD. A strategy to reduce interruptions at hospital morning report. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(1):83-84. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-09-00084.1

16. Witherspoon L, Nham E, Abdi H, et al. Is it time to rethink how we page physicians? Understanding paging patterns in a tertiary care hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):992. Published 2019 Dec 23. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4844-0

17. Fargen KM, O’Connor T, Raymond S, Sporrer JM, Friedman WA. An observational study of hospital paging practices and workflow interruption among on-call junior neurological surgery residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):467-471. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00306.1

18. Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, et al. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):729-732. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

Regularly scheduled educational conferences, such as case-based morning reports, have been a standard part of internal medicine residencies for decades.1-4 In addition to better patient care from the knowledge gained at educational conferences, attendance by interns and residents (collectively called house staff) may be associated with higher in-service examination scores.5 Unfortunately, competing priorities, including patient care and trainee supervision, may contribute to an action-intention gap among house staff that reduces attendance.6-8 Low attendance at morning reports represents wasted effort and lost educational opportunities; therefore, strategies to increase attendance are needed. Of several methods studied, more resource-intensive interventions (eg, providing food) were the most successful.6,9-12

Using the behavioral economics framework of nudge strategies, we hypothesized that a less intensive intervention of a daily reminder text page would encourage medical students, interns, and residents (collectively called learners) to attend the morning report conference.8,13 However, given the high cognitive load created by frequent task switching, a reminder text page could disrupt workflow and patient care without promoting the intended behavior change.14-17 Because of this uncertainty, our objective was to determine whether a preconference text page increased learner attendance at morning report conferences.

Methods

This study was a single-center, multiple-crossover cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at the Veteran Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts. Study participants included house staff rotating on daytime inpatient rotations from 4 residency programs and students from 2 medical schools. The setting was the morning report, an in-person, interactive, case-based conference held Monday through Thursday, from 8:00

Learners assigned to rotate on the inpatient medicine, cardiology, medicine consultation, and patient safety rotations were eligible to attend these conferences and for inclusion in the study. Learners rotating in the medical intensive care unit, on night float, or on day float (an admitting shift for which residents are not on-site until late afternoon) were excluded. Additional details of the study population are available in the supplement (eAppendix). The study period was originally planned for September 30, 2019, to March 31, 2020, but data collection was stopped on March 12, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and suspension of in-person conferences. We chose the study period, which determined our sample size, to exclude the first 3 months of the academic year (July-September) because during that time learners acclimate to the inpatient workflow. We also chose not to include the last 3 months of the academic year to provide time for data analysis and preparation of the manuscript within the academic year.

Intervention and Outcome Assessment

Each intervention and control period was 3 weeks long; the first period was randomly determined by coin flip and alternated thereafter. Additional details of randomization are available in the supplement (Appendix 1). During intervention periods, all house staff received a page at 7:55

A daily facesheet (a roster of house staff names and photos) was used to identify learners for conference attendance. This facesheet was already used for other purposes at VABHS. At 8:00

During control periods, no text page reminder of upcoming conferences was sent, but the attendance of total learners at 8:00

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the proportion of eligible learners present at 8:10

To estimate the primary outcome, we modeled the risk difference adjusted for covariates using a generalized estimating equation accounting for the clustering of attendance behavior within individuals and controlling for date and team. Secondary outcomes were estimated similarly. To evaluate the robustness of the primary outcome, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a multilevel generalized linear model with clustering by individual learner and team. Additional details on our statistical analysis plan, including accessing our raw data and analysis code, are available in Appendices 2 and 3. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. All P values were 2-sided, and a significance level of ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed in Stata v16.1. Our study was deemed exempt by the VABHS Institutional Review Board, and this article was prepared following the CONSORT reporting guidelines. The trial protocol has been registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number registry

Results

Over the study period, 329 unique learners rotated on inpatient medical services at the VABHS and 211 were eligible to attend 85 morning report conferences and 22 Jeopardy conferences (Figure). Outcomes data were available for 100% of eligible participants. Forty-seven (55%) of the morning report conferences occurred during the intervention period (Table 1).

Morning report attendance observed at 8:10

On-time attendance was lower than at 8:10

To estimate the impact of rotating on teams with lighter clinical workloads on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we repeated our primary analysis with a test of interaction between team assignment and the intervention, which was not significant (P = .90). To estimate the impact of morning workload on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we performed a subgroup analysis limited to learners rotating on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and included the number of overnight admissions as a covariate in our regression model. A test of interaction between the intervention and the number of overnight admissions on conference attendance was not significant (P = .73).

In a subgroup analysis limited to learners on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and controlling for the number of overnight admissions (a proxy for morning workload), no significant interaction between the intervention and admissions was observed. We also assessed for interaction between learner type and receipt of a reminder page on conference attendance and found no evidence of such an effect.

Discussion

Among a diverse population of learners from multiple academic institutions rotating at a single, large, urban VA medical center, a nudge strategy of sending a reminder text page before morning report conferences was associated with a 4.0% absolute increase in attendance measured 10 minutes after the conference started compared with not sending a reminder page. Overall, only one-quarter of learners attended the morning report at the start at 8:00

We designed our analysis to overcome several limitations of prior studies on the effect of reminder text pages on conference attendance. First, to account for differences in conference attendance behavior of individual learners, we used a generalized estimating equation model that allowed clustering of outcomes by individual. Second, we controlled for the date to account for secular trends in conference attendance over the academic year. Finally, we controlled for the team to account for the possibility that the conference attendance behavior of one learner on a team influences the behavior of other learners on the same team.

We also evaluated the effect of a reminder page on attendance at a weekly Jeopardy conference. Interestingly, reminder pages seemed to increase on-time Jeopardy attendance, although this effect was no longer statistically significant at 8:10

We also assessed the interaction between sending a reminder page and learner type and its effect on conference attendance and found no evidence to support such an effect. Because medical students do not receive reminder pages, their conference attendance behavior can be thought of as indicative of clustering within teams. Though there was no evidence of a significant interaction, given the small number of students, our study may be underpowered to find a benefit for this group.

The results of this study differ from Smith and colleagues, who found that reminder pages had no overall effect on conference attendance for fellows; however, no sample size justification was provided in that study, making it difficult to evaluate the likelihood of a false-negative finding.7 Our study differs in several ways: the timing of the reminder page (5 minutes vs 30 minutes prior to the conference), the method by which attendance was recorded (by an independent observer vs learner sign-in), and the time that attendance was recorded (2 prespecified times vs continuously). As far as we know, our study is the first to evaluate the nudge effect of reminder text pages on internal medicine resident attendance at conferences, with attendance taken by an observer.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it was conducted at a single VA medical center. An additional limitation was our decision to classify learners who arrived after 8:10

Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the suspension of in-person conferences, our study ended earlier than anticipated. This resulted in an imbalance of morning report conferences that occurred during each period: 55% during the intervention period, and 45% during the control period. However, because we accounted for the clustering of conference attendance behavior within individuals in our model, this imbalance is unlikely to introduce bias in our estimation of the effect of the intervention.

Another limitation relates to the evolving landscape of educational conferences in the postpandemic era.18 Whether our results can be generalized to increase virtual conference attendance is unknown. Finally, it is not clear whether a 4% absolute increase in conference attendance is educationally meaningful or justifies the effort of sending a reminder page.

Conclusions

In this cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at a single VA medical center, reminder pages sent 5 minutes before the start of morning report conferences resulted in a 4% increase in conference attendance. Our results suggest that reminder pages are one strategy that may result in a small increase in conference attendance, but whether this small increase is educationally significant will vary across training programs applying this strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Kenneth J. Mukamal and Katharine A. Robb, who provided invaluable guidance in data analysis. Todd Reese assisted in data organization and presentation of data, and Mark Tuttle designed the facesheet. None of these individuals received compensation for their assistance.

Regularly scheduled educational conferences, such as case-based morning reports, have been a standard part of internal medicine residencies for decades.1-4 In addition to better patient care from the knowledge gained at educational conferences, attendance by interns and residents (collectively called house staff) may be associated with higher in-service examination scores.5 Unfortunately, competing priorities, including patient care and trainee supervision, may contribute to an action-intention gap among house staff that reduces attendance.6-8 Low attendance at morning reports represents wasted effort and lost educational opportunities; therefore, strategies to increase attendance are needed. Of several methods studied, more resource-intensive interventions (eg, providing food) were the most successful.6,9-12

Using the behavioral economics framework of nudge strategies, we hypothesized that a less intensive intervention of a daily reminder text page would encourage medical students, interns, and residents (collectively called learners) to attend the morning report conference.8,13 However, given the high cognitive load created by frequent task switching, a reminder text page could disrupt workflow and patient care without promoting the intended behavior change.14-17 Because of this uncertainty, our objective was to determine whether a preconference text page increased learner attendance at morning report conferences.

Methods

This study was a single-center, multiple-crossover cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at the Veteran Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) in Massachusetts. Study participants included house staff rotating on daytime inpatient rotations from 4 residency programs and students from 2 medical schools. The setting was the morning report, an in-person, interactive, case-based conference held Monday through Thursday, from 8:00

Learners assigned to rotate on the inpatient medicine, cardiology, medicine consultation, and patient safety rotations were eligible to attend these conferences and for inclusion in the study. Learners rotating in the medical intensive care unit, on night float, or on day float (an admitting shift for which residents are not on-site until late afternoon) were excluded. Additional details of the study population are available in the supplement (eAppendix). The study period was originally planned for September 30, 2019, to March 31, 2020, but data collection was stopped on March 12, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and suspension of in-person conferences. We chose the study period, which determined our sample size, to exclude the first 3 months of the academic year (July-September) because during that time learners acclimate to the inpatient workflow. We also chose not to include the last 3 months of the academic year to provide time for data analysis and preparation of the manuscript within the academic year.

Intervention and Outcome Assessment

Each intervention and control period was 3 weeks long; the first period was randomly determined by coin flip and alternated thereafter. Additional details of randomization are available in the supplement (Appendix 1). During intervention periods, all house staff received a page at 7:55

A daily facesheet (a roster of house staff names and photos) was used to identify learners for conference attendance. This facesheet was already used for other purposes at VABHS. At 8:00

During control periods, no text page reminder of upcoming conferences was sent, but the attendance of total learners at 8:00

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was the proportion of eligible learners present at 8:10

To estimate the primary outcome, we modeled the risk difference adjusted for covariates using a generalized estimating equation accounting for the clustering of attendance behavior within individuals and controlling for date and team. Secondary outcomes were estimated similarly. To evaluate the robustness of the primary outcome, we performed a sensitivity analysis using a multilevel generalized linear model with clustering by individual learner and team. Additional details on our statistical analysis plan, including accessing our raw data and analysis code, are available in Appendices 2 and 3. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 or Fisher exact test. Continuous variables were compared using the t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. All P values were 2-sided, and a significance level of ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed in Stata v16.1. Our study was deemed exempt by the VABHS Institutional Review Board, and this article was prepared following the CONSORT reporting guidelines. The trial protocol has been registered with the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number registry

Results

Over the study period, 329 unique learners rotated on inpatient medical services at the VABHS and 211 were eligible to attend 85 morning report conferences and 22 Jeopardy conferences (Figure). Outcomes data were available for 100% of eligible participants. Forty-seven (55%) of the morning report conferences occurred during the intervention period (Table 1).

Morning report attendance observed at 8:10

On-time attendance was lower than at 8:10

To estimate the impact of rotating on teams with lighter clinical workloads on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we repeated our primary analysis with a test of interaction between team assignment and the intervention, which was not significant (P = .90). To estimate the impact of morning workload on the association between receipt of a reminder page and conference attendance, we performed a subgroup analysis limited to learners rotating on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and included the number of overnight admissions as a covariate in our regression model. A test of interaction between the intervention and the number of overnight admissions on conference attendance was not significant (P = .73).

In a subgroup analysis limited to learners on teams eligible to receive overnight admissions and controlling for the number of overnight admissions (a proxy for morning workload), no significant interaction between the intervention and admissions was observed. We also assessed for interaction between learner type and receipt of a reminder page on conference attendance and found no evidence of such an effect.

Discussion

Among a diverse population of learners from multiple academic institutions rotating at a single, large, urban VA medical center, a nudge strategy of sending a reminder text page before morning report conferences was associated with a 4.0% absolute increase in attendance measured 10 minutes after the conference started compared with not sending a reminder page. Overall, only one-quarter of learners attended the morning report at the start at 8:00

We designed our analysis to overcome several limitations of prior studies on the effect of reminder text pages on conference attendance. First, to account for differences in conference attendance behavior of individual learners, we used a generalized estimating equation model that allowed clustering of outcomes by individual. Second, we controlled for the date to account for secular trends in conference attendance over the academic year. Finally, we controlled for the team to account for the possibility that the conference attendance behavior of one learner on a team influences the behavior of other learners on the same team.

We also evaluated the effect of a reminder page on attendance at a weekly Jeopardy conference. Interestingly, reminder pages seemed to increase on-time Jeopardy attendance, although this effect was no longer statistically significant at 8:10

We also assessed the interaction between sending a reminder page and learner type and its effect on conference attendance and found no evidence to support such an effect. Because medical students do not receive reminder pages, their conference attendance behavior can be thought of as indicative of clustering within teams. Though there was no evidence of a significant interaction, given the small number of students, our study may be underpowered to find a benefit for this group.

The results of this study differ from Smith and colleagues, who found that reminder pages had no overall effect on conference attendance for fellows; however, no sample size justification was provided in that study, making it difficult to evaluate the likelihood of a false-negative finding.7 Our study differs in several ways: the timing of the reminder page (5 minutes vs 30 minutes prior to the conference), the method by which attendance was recorded (by an independent observer vs learner sign-in), and the time that attendance was recorded (2 prespecified times vs continuously). As far as we know, our study is the first to evaluate the nudge effect of reminder text pages on internal medicine resident attendance at conferences, with attendance taken by an observer.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it was conducted at a single VA medical center. An additional limitation was our decision to classify learners who arrived after 8:10

Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the suspension of in-person conferences, our study ended earlier than anticipated. This resulted in an imbalance of morning report conferences that occurred during each period: 55% during the intervention period, and 45% during the control period. However, because we accounted for the clustering of conference attendance behavior within individuals in our model, this imbalance is unlikely to introduce bias in our estimation of the effect of the intervention.

Another limitation relates to the evolving landscape of educational conferences in the postpandemic era.18 Whether our results can be generalized to increase virtual conference attendance is unknown. Finally, it is not clear whether a 4% absolute increase in conference attendance is educationally meaningful or justifies the effort of sending a reminder page.

Conclusions

In this cluster randomized controlled trial conducted at a single VA medical center, reminder pages sent 5 minutes before the start of morning report conferences resulted in a 4% increase in conference attendance. Our results suggest that reminder pages are one strategy that may result in a small increase in conference attendance, but whether this small increase is educationally significant will vary across training programs applying this strategy.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to Kenneth J. Mukamal and Katharine A. Robb, who provided invaluable guidance in data analysis. Todd Reese assisted in data organization and presentation of data, and Mark Tuttle designed the facesheet. None of these individuals received compensation for their assistance.

1. Daniels VJ, Goldstein CE. Changing morning report: an educational intervention to address curricular needs. J Biomed Educ. 2014;2014:1-5. doi:10.1155/2014/830701

2. Parrino TA, Villanueva AG. The principles and practice of morning report. JAMA. 1986;256(6):730-733. doi:10.1001/jama.1986.03380060056025

3. Wenger NS, Shpiner RB. An analysis of morning report: implications for internal medicine education. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(5):395-399. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-5-199309010-00008

4. Ways M, Kroenke K, Umali J, Buchwald D. Morning report. A survey of resident attitudes. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(13):1433-1437. doi:10.1001/archinte.155.13.1433

5. McDonald FS, Zeger SL, Kolars JC. Associations of conference attendance with internal medicine in-training examination scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(4):449-453. doi:10.4065/83.4.449

6. FitzGerald JD, Wenger NS. Didactic teaching conferences for IM residents: who attends, and is attendance related to medical certifying examination scores? Acad Med. 2003;78(1):84-89. doi:10.1097/00001888-200301000-00015

7. Smith J, Zaffiri L, Clary J, Davis T, Bosslet GT. The effect of paging reminders on fellowship conference attendance: a multi-program randomized crossover study. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):372-377. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00487.1

8. Sheeran P, Webb TL. The intention-behavior gap. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2016;10(9):503-518. doi:10.1111/spc3.12265

9. McDonald RJ, Luetmer PH, Kallmes DF. If you starve them, will they still come? Do complementary food provisions affect faculty meeting attendance in academic radiology? J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8(11):809-810. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.06.003

10. Segovis CM, Mueller PS, Rethlefsen ML, et al. If you feed them, they will come: a prospective study of the effects of complimentary food on attendance and physician attitudes at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:22. Published 2007 Jul 12. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-7-22

11. Mueller PS, Litin SC, Sowden ML, Habermann TM, LaRusso NF. Strategies for improving attendance at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(5):549-553. doi:10.4065/78.5.549

12. Tarabichi S, DeLeon M, Krumrei N, Hanna J, Maloney Patel N. Competition as a means for improving academic scores and attendance at education conference. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):1437-1440. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.04.020

13. Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Rev. and Expanded Ed. Penguin Books; 2009.

14. Weijers RJ, de Koning BB, Paas F. Nudging in education: from theory towards guidelines for successful implementation. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2021;36:883-902. Published 2020 Aug 24. doi:10.1007/s10212-020-00495-0

15. Wieland ML, Loertscher LL, Nelson DR, Szostek JH, Ficalora RD. A strategy to reduce interruptions at hospital morning report. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(1):83-84. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-09-00084.1

16. Witherspoon L, Nham E, Abdi H, et al. Is it time to rethink how we page physicians? Understanding paging patterns in a tertiary care hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):992. Published 2019 Dec 23. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4844-0

17. Fargen KM, O’Connor T, Raymond S, Sporrer JM, Friedman WA. An observational study of hospital paging practices and workflow interruption among on-call junior neurological surgery residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):467-471. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00306.1

18. Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, et al. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):729-732. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018

1. Daniels VJ, Goldstein CE. Changing morning report: an educational intervention to address curricular needs. J Biomed Educ. 2014;2014:1-5. doi:10.1155/2014/830701

2. Parrino TA, Villanueva AG. The principles and practice of morning report. JAMA. 1986;256(6):730-733. doi:10.1001/jama.1986.03380060056025

3. Wenger NS, Shpiner RB. An analysis of morning report: implications for internal medicine education. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(5):395-399. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-119-5-199309010-00008

4. Ways M, Kroenke K, Umali J, Buchwald D. Morning report. A survey of resident attitudes. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(13):1433-1437. doi:10.1001/archinte.155.13.1433

5. McDonald FS, Zeger SL, Kolars JC. Associations of conference attendance with internal medicine in-training examination scores. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(4):449-453. doi:10.4065/83.4.449

6. FitzGerald JD, Wenger NS. Didactic teaching conferences for IM residents: who attends, and is attendance related to medical certifying examination scores? Acad Med. 2003;78(1):84-89. doi:10.1097/00001888-200301000-00015

7. Smith J, Zaffiri L, Clary J, Davis T, Bosslet GT. The effect of paging reminders on fellowship conference attendance: a multi-program randomized crossover study. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(3):372-377. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-15-00487.1

8. Sheeran P, Webb TL. The intention-behavior gap. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2016;10(9):503-518. doi:10.1111/spc3.12265

9. McDonald RJ, Luetmer PH, Kallmes DF. If you starve them, will they still come? Do complementary food provisions affect faculty meeting attendance in academic radiology? J Am Coll Radiol. 2011;8(11):809-810. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2011.06.003

10. Segovis CM, Mueller PS, Rethlefsen ML, et al. If you feed them, they will come: a prospective study of the effects of complimentary food on attendance and physician attitudes at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:22. Published 2007 Jul 12. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-7-22

11. Mueller PS, Litin SC, Sowden ML, Habermann TM, LaRusso NF. Strategies for improving attendance at medical grand rounds at an academic medical center. Mayo Clin Proc. 2003;78(5):549-553. doi:10.4065/78.5.549

12. Tarabichi S, DeLeon M, Krumrei N, Hanna J, Maloney Patel N. Competition as a means for improving academic scores and attendance at education conference. J Surg Educ. 2018;75(6):1437-1440. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.04.020

13. Thaler RH, Sunstein CR. Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Rev. and Expanded Ed. Penguin Books; 2009.

14. Weijers RJ, de Koning BB, Paas F. Nudging in education: from theory towards guidelines for successful implementation. Eur J Psychol Educ. 2021;36:883-902. Published 2020 Aug 24. doi:10.1007/s10212-020-00495-0

15. Wieland ML, Loertscher LL, Nelson DR, Szostek JH, Ficalora RD. A strategy to reduce interruptions at hospital morning report. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(1):83-84. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-09-00084.1

16. Witherspoon L, Nham E, Abdi H, et al. Is it time to rethink how we page physicians? Understanding paging patterns in a tertiary care hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):992. Published 2019 Dec 23. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-4844-0

17. Fargen KM, O’Connor T, Raymond S, Sporrer JM, Friedman WA. An observational study of hospital paging practices and workflow interruption among on-call junior neurological surgery residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(4):467-471. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-11-00306.1

18. Chick RC, Clifton GT, Peace KM, et al. Using technology to maintain the education of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Surg Educ. 2020;77(4):729-732. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.03.018