User login

Does Patient Experience Predict 30-Day Readmission? A Patient-Level Analysis of HCAHPS Data

Patient experience and 30-day readmission are important measures of quality of care for hospitalized patients. Performance on both of these measures impact hospitals financially. Performance on the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Systems and Providers (HCAHPS) survey is linked to 25% of the incentive payment under Value Based Purchasing (VBP) Program.1 Starting in 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced the Readmission Reduction Program, penalizing hospitals financially for excessive readmissions.2

A relationship between patient experience and readmissions has been explored at the hospital level. Studies have mostly found that higher patient experience scores are associated with lower 30-day readmission rates. In a study of the relationship between 30-day risk-standardized readmission rates for three medical conditions (acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia) and patient experience, the authors noted that higher experience scores for overall care and discharge planning were associated with lower readmission rates for these conditions. They also concluded that patient experience scores were more predictive of 30-day readmission than clinical performance measures. Additionally, the authors predicted that if a hospital increased its total experience scores from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile, there would be an associated decrease in readmissions by at least 2.3% for each of these conditions.3 Practice management companies and the media have cited this finding to conclude that higher patient experience drives clinical outcomes such as 30-day readmission and that patients are often the best judges of the quality of care delivered.4,5

Other hospital-level studies have found that high 30-day readmission rates are associated with lower overall experience scores in a mixed surgical patient population; worse reports of pain control and overall care in the colorectal surgery population; lower experience scores with discharge preparedness in vascular surgery patients; and lower experience scores with physician communication, nurse communication, and discharge preparedness.6-9 A patient-level study noted higher readmissions are associated with worse experience with physician and nursing communication along with a paradoxically better experience with discharge information.10

Because these studies used an observational design, they demonstrated associations rather than causality. An alternative hypothesis is that readmitted patients complete their patient experience survey after readmission and the low experience is the result, rather than the cause, of their readmission. For patients who are readmitted, it is unclear whether there is an opportunity to complete the survey prior to readmission and whether being readmitted may impact patient perception of quality of care. Using patient-level data, we sought to assess HCAHPS patient-experience responses linked to the index admission of the patients who were readmitted in 30 days and compare it with those patients who were not readmitted during this time period. We paid particular attention to when the surveys were returned.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected 10-year HCAHPS and Press Ganey patient survey data for a single tertiary care academic hospital.

Participants

All adult patients discharged from the hospital and who responded to the routinely sent patient-experience survey were included. Surveys were sent to a random sample of 50% of the discharged patients.

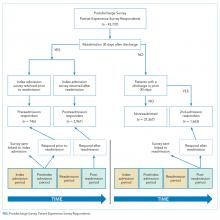

The exposure group was comprised of patients who responded to the survey and were readmitted within 30 days of discharge. After subtracting 5 days from the survey receipt date for expected delays related to mail delivery time and processing time, survey response date was calculated. The exposure group was further divided into patients who responded to the survey prior to their 30-day readmission (“Pre-readmission responders”) and those that responded to the survey after their readmission (“Postreadmission responders”). A sensitivity analysis was performed by changing the number of days subtracted from the survey receipt date by 2 days in either direction. This approach did not result in any significant changes in the results.

The control group comprised patients who were not readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge and who did not have an admission in the previous 30 days as well (“Not readmitted” group). An additional comparison group for exploratory analysis included patients who had experienced an admission in the prior 30 days but were not readmitted after the admission linked to the survey. These patients responded to the patient-experience surveys that were linked to their second admission in 30 days (“2nd-admission responders” group; Figure).

Time Periods

All survey responders from the third quarter of 2006 to the first quarter of 2016 were included in the study. Additionally, administrative data on non-responders were available from 7/2006 to 8/2012. These data were used to estimate response rates. Patient level experience and administrative data were obtained in a linked fashion for these time periods.

Instruments

Press Ganey and HCAHPS surveys were sent via mail in the same envelope. Fifty percent of the discharged patients were randomized to receive the surveys. The Press Ganey survey contained 33 items encompassing several subdomains, including room, meal, nursing, physician, ancillary staff, visitor, discharge, and overall experience.

The HCAHPS survey contained 29 CMS-mandated items, of which 21 are related to patient experience. The development, testing, and methods for administration and reporting of the HCAHPS survey have been previously described and studies using this instrument have been reported in the literature.11 Press Ganey patient satisfaction survey results have also been reported in the literature.12

Outcome Variables and Covariates

HCAHPS and Press Ganey experience survey individual item responses were the primary outcome variables of this study. Age, self-reported health status, education, primary language spoken, service line, and time taken to respond to the surveys served as the covariates. These variables are used by CMS for patient-mix adjustment and are collected on the HCAHPS survey. Additionally, the number of days to respond to the survey were included in all regression analysis to adjust for early responder effect.13-15

Statistical Analysis

“Percent top-box” scores were calculated for each survey item for patients in each group. The percent top-box scores were calculated as the percent of patients who responded “very good” for a given item on Press Ganey survey items and “always” or “definitely yes” or “yes” or “9” or “10” on HCAHPS survey items. CMS utilizes “percent top-box scores” to calculate payments under the VBP program and to report the results publicly. Numerous studies have also reported percent top-box scores for HCAHPS survey results.12

We hypothesized that whether patients complete the HCAHPS survey before or after the readmission influences their reporting of experience. To test this hypothesis, HCAHPS and Press Ganey item top-box scores of “Pre-readmission responders” and “Postreadmission responders” were compared with those of the control group using multivariate logistic regression. “Pre-readmission responders” were also compared with “Postreadmission responders”.

“2nd-admission responders” were similarly compared with the control group for an exploratory analysis. Finally, “Postreadmission responders” and “2nd-admission responders” were compared in another exploratory analysis since both these groups responded to the survey after being exposed to the readmission, even though the “Postreadmission responders” group is administratively linked to the index admission.

The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

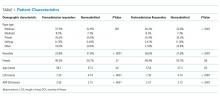

There were 43,737 survey responders, among whom 4,707 were subsequently readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Among the readmitted patients who responded to the surveys linked to their index admission, only 15.8% returned the survey before readmission (pre-readmission responders’) and 84.2% returned the survey after readmission (postreadmission responders). Additionally, 1,663 patients responded to experience surveys linked to their readmission. There were 37,365 patients in the control arm (ie, patients who responded to the survey and were not readmitted within 30 days of discharge or in the prior 30 days; Figure 1). The readmission rate among survey responders was 10.6%. Among the readmitted patients, the median number of days to readmission was 10 days while the median number of days to respond to the survey for this group was 33 days. Among the nonreadmitted patients, the median number of days to return the survey was 29 days.

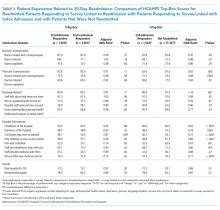

We also conducted an exploratory analysis of the postreadmission responders, comparing them with patients who received patient-experience surveys linked to their second admission in 30 days. Both of these groups were exposed to a readmission before they completed the surveys. There were no significant differences between these two groups on patient experience scores. Additionally, the patients who received the survey linked to their readmission had a broad dissatisfaction pattern on HCAHPS survey items that appeared similar to that of the postreadmission group when compared to the non-readmitted group (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis of prospectively collected Press Ganey and HCAHPS patient-experience survey data, we found that the overwhelming majority of patients readmitted within 30 days of discharge respond to HCAHPS surveys after readmission even though the survey is sent linked to the first admission. This is not unexpected since the median time to survey response is 33 days for this group, while median time to readmission is 10 days. The dissatisfaction pattern of Postreadmission responders was similar to those who responded to the survey linked to the readmission. When a patient is readmitted prior to completing the survey, their responses appear to reflect the cumulative experience of the index admission and the readmission. The lower scores of those who respond to the survey after their readmission appear to be a driver for lower patient-experience scores related to readmissions. Overall, readmission was associated with lower scores on items in five of the nine domains used to calculate patient experience related payments under VBP.16

These findings have important implications in inferring the direction of potential causal relationship between readmissions and patient experience at the hospital level. Additionally, these patients show broad dissatisfaction with areas beyond physician communication and discharge planning. These include staff responsiveness, phlebotomy, meals, hospital cleanliness, and noise level. This pattern of dissatisfaction may represent impatience and frustration with spending additional time in the hospital environment.

Our results are consistent with findings of many of the earlier studies, but our study goes a step further by using patient-level data and incorporating survey response time in our analysis.3,7,9,10 By separating out the readmitted patients who responded to the survey prior to admission, we attempted to address the ability of patients’ perception of care to predict future readmissions. Our results do not support this idea, since pre-readmission responders had similar experience scores to non-readmitted patients. However, because of the low numbers of pre-readmission responders, the comparison lacks precision. Current HCAHPS and Press Ganey questions may lack the ability to predict future readmissions because of the timing of the survey (postdischarge) or the questions themselves.

Overall, postreadmission responders are dissatisfied with multiple domains of hospital care. Many of these survey responses may simply be related to general frustration. Alternatively, they may represent a patient population with a high degree of needs that are not as easily met by a hospital’s routine processes of care. Even though the readmission rates were 10.6% among survey responders, 14.6% of the survey responses were associated with readmissions after accounting for those who respond to surveys linked to readmission. These patients could have significant impact on cumulative experience scores.

Our study has a few limitations. First, it involves a single tertiary care academic center study, and our results may not be generalizable. Second, we did not adjust for some of the patient characteristics associated with readmissions. Patients who were admitted within 30 days are different than those not readmitted based on payor, race, length of stay, and severity of illness, and we did not adjust for these factors in our analysis. This was intentional, however. Our goal was to better understand the relationship between 30-day readmission and patient experience scores as they are used for hospital-level studies, VBP, and public reporting. For these purposes, the scores are not adjusted for factors, such as payor and length of stay. We did adjust for patient-mix adjustment factors used by CMS. Third, the response rates to the HCAHPS were low and may have biased the scores. However, HCAHPS is widely used for comparisons between hospitals has been validated, and our study results have implications with regard to comparing hospital-level performance. HCAHPS results are relevant to policy and have financial consequences.17 Fourth, our study did not directly compare whether the relationship between patient experience for the postreadmission group and nonreadmitted group was different from the relationship between the pre-readmission group and postreadmission group. It is possible that there is no difference in relationship between the groups. However, despite the small number of pre-readmission responders, these patients tended to have more favorable experience responses than those who responded after being readmitted, even after adjusting for response time. Although the P values are nonsignificant for many comparisons, the directionality of the effect is relatively consistent. Also, the vast majority of the patients fall in the postreadmission group, and these patients appear to drive the overall experience related to readmissions. Finally, since relatively few patients turned in surveys prior to readmission, we had limited power to detect a significant difference between these pre-readmission responders and nonreadmitted patients.

Our study has implications for policy makers, researchers, and providers. The HCAHPS scores of patients who are readmitted and completed the survey after being readmitted reflects their experience of both the index admission and the readmission. We did not find evidence to support that HCAHPS survey responses predict future readmissions at the patient level. Our findings do support the concept that lower readmissions rates (whether due to the patient population or processes of care that decrease readmission rates) may improve HCAHPS scores. We suggest caution in assuming that improving patient experience is likely to reduce readmission rates.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1. Hospital value-based purchasing. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/Hospital_VBPurchasing_Fact_Sheet_ICN907664.pdf. Accessed June 25, 2016.

2. Readmissions reduction program (HRRP). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed June 25, 2016.

3. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-48. PubMed

4. Buum HA, Duran-Nelson AM, Menk J, Nixon LJ. Duty-hours monitoring revisited: self-report may not be adequate. Am J Med. 2013;126(4):362-365. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.12.003 PubMed

5. Choma NN, Vasilevskis EE, Sponsler KC, Hathaway J, Kripalani S. Effect of the ACGME 16-hour rule on efficiency and quality of care: duty hours 2.0. JAMA Int Med. 2013;173(9):819-821. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3014 PubMed

6. Brooke BS, Samourjian E, Sarfati MR, Nguyen TT, Greer D, Kraiss LW. RR3. Patient-reported readiness at time of discharge predicts readmission following vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(6):188S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.04.356

7. Duraes LC, Merlino J, Stocchi L, et al. 756 readmission decreases patient satisfaction in colorectal surgery. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):S-1029. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(14)63751-3

8. Mitchell JP. Association of provider communication and discharge instructions on lower readmissions. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):33-40. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460126.88382.13 PubMed

9. Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient satisfaction and quality of surgical care in US hospitals. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):2-8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000765 PubMed

10. Hachem F, Canar J, Fullam M, Andrew S, Hohmann S, Johnson C. The relationships between HCAHPS communication and discharge satisfaction items and hospital readmissions. Patient Exp J. 2014;1(2):71-77.

11. Irby DM, Cooke M, Lowenstein D, Richards B. The academy movement: a structural approach to reinvigorating the educational mission. Acad Med. 2004;79(8):729-736. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200408000-00003 PubMed

12. Siddiqui ZK, Zuccarelli R, Durkin N, Wu AW, Brotman DJ. Changes in patient satisfaction related to hospital renovation: experience with a new clinical building. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):165-171. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2297 PubMed

13. Nair BR, Coughlan JL, Hensley MJ. Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching. Med Educ. 1997;31(5):341-346. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1997.00673.x PubMed

14. Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, Goldstein E, et al. Effects of survey mode, patient mix, and nonresponse on CAHPS® hospital survey scores. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;44(2p1):501-518. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00914.x PubMed

15. Saunders CL, Elliott MN, Lyratzopoulos G, Abel GA. Do differential response rates to patient surveys between organizations lead to unfair performance comparisons?: evidence from the English Cancer Patient Experience Survey. Medical care. 2016;54(1):45. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000457 PubMed

16. Sabel E, Archer J. “Medical education is the ugly duckling of the medical world” and other challenges to medical educators’ identity construction: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1474-1480. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000420 PubMed

17. O’Malley AJ, Zaslavsky AM, Elliott MN, Zaborski L, Cleary PD. Case‐Mix adjustment of the CAHPS® Hospital Survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6p2):2162-2181. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00470.x

Patient experience and 30-day readmission are important measures of quality of care for hospitalized patients. Performance on both of these measures impact hospitals financially. Performance on the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Systems and Providers (HCAHPS) survey is linked to 25% of the incentive payment under Value Based Purchasing (VBP) Program.1 Starting in 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced the Readmission Reduction Program, penalizing hospitals financially for excessive readmissions.2

A relationship between patient experience and readmissions has been explored at the hospital level. Studies have mostly found that higher patient experience scores are associated with lower 30-day readmission rates. In a study of the relationship between 30-day risk-standardized readmission rates for three medical conditions (acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia) and patient experience, the authors noted that higher experience scores for overall care and discharge planning were associated with lower readmission rates for these conditions. They also concluded that patient experience scores were more predictive of 30-day readmission than clinical performance measures. Additionally, the authors predicted that if a hospital increased its total experience scores from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile, there would be an associated decrease in readmissions by at least 2.3% for each of these conditions.3 Practice management companies and the media have cited this finding to conclude that higher patient experience drives clinical outcomes such as 30-day readmission and that patients are often the best judges of the quality of care delivered.4,5

Other hospital-level studies have found that high 30-day readmission rates are associated with lower overall experience scores in a mixed surgical patient population; worse reports of pain control and overall care in the colorectal surgery population; lower experience scores with discharge preparedness in vascular surgery patients; and lower experience scores with physician communication, nurse communication, and discharge preparedness.6-9 A patient-level study noted higher readmissions are associated with worse experience with physician and nursing communication along with a paradoxically better experience with discharge information.10

Because these studies used an observational design, they demonstrated associations rather than causality. An alternative hypothesis is that readmitted patients complete their patient experience survey after readmission and the low experience is the result, rather than the cause, of their readmission. For patients who are readmitted, it is unclear whether there is an opportunity to complete the survey prior to readmission and whether being readmitted may impact patient perception of quality of care. Using patient-level data, we sought to assess HCAHPS patient-experience responses linked to the index admission of the patients who were readmitted in 30 days and compare it with those patients who were not readmitted during this time period. We paid particular attention to when the surveys were returned.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected 10-year HCAHPS and Press Ganey patient survey data for a single tertiary care academic hospital.

Participants

All adult patients discharged from the hospital and who responded to the routinely sent patient-experience survey were included. Surveys were sent to a random sample of 50% of the discharged patients.

The exposure group was comprised of patients who responded to the survey and were readmitted within 30 days of discharge. After subtracting 5 days from the survey receipt date for expected delays related to mail delivery time and processing time, survey response date was calculated. The exposure group was further divided into patients who responded to the survey prior to their 30-day readmission (“Pre-readmission responders”) and those that responded to the survey after their readmission (“Postreadmission responders”). A sensitivity analysis was performed by changing the number of days subtracted from the survey receipt date by 2 days in either direction. This approach did not result in any significant changes in the results.

The control group comprised patients who were not readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge and who did not have an admission in the previous 30 days as well (“Not readmitted” group). An additional comparison group for exploratory analysis included patients who had experienced an admission in the prior 30 days but were not readmitted after the admission linked to the survey. These patients responded to the patient-experience surveys that were linked to their second admission in 30 days (“2nd-admission responders” group; Figure).

Time Periods

All survey responders from the third quarter of 2006 to the first quarter of 2016 were included in the study. Additionally, administrative data on non-responders were available from 7/2006 to 8/2012. These data were used to estimate response rates. Patient level experience and administrative data were obtained in a linked fashion for these time periods.

Instruments

Press Ganey and HCAHPS surveys were sent via mail in the same envelope. Fifty percent of the discharged patients were randomized to receive the surveys. The Press Ganey survey contained 33 items encompassing several subdomains, including room, meal, nursing, physician, ancillary staff, visitor, discharge, and overall experience.

The HCAHPS survey contained 29 CMS-mandated items, of which 21 are related to patient experience. The development, testing, and methods for administration and reporting of the HCAHPS survey have been previously described and studies using this instrument have been reported in the literature.11 Press Ganey patient satisfaction survey results have also been reported in the literature.12

Outcome Variables and Covariates

HCAHPS and Press Ganey experience survey individual item responses were the primary outcome variables of this study. Age, self-reported health status, education, primary language spoken, service line, and time taken to respond to the surveys served as the covariates. These variables are used by CMS for patient-mix adjustment and are collected on the HCAHPS survey. Additionally, the number of days to respond to the survey were included in all regression analysis to adjust for early responder effect.13-15

Statistical Analysis

“Percent top-box” scores were calculated for each survey item for patients in each group. The percent top-box scores were calculated as the percent of patients who responded “very good” for a given item on Press Ganey survey items and “always” or “definitely yes” or “yes” or “9” or “10” on HCAHPS survey items. CMS utilizes “percent top-box scores” to calculate payments under the VBP program and to report the results publicly. Numerous studies have also reported percent top-box scores for HCAHPS survey results.12

We hypothesized that whether patients complete the HCAHPS survey before or after the readmission influences their reporting of experience. To test this hypothesis, HCAHPS and Press Ganey item top-box scores of “Pre-readmission responders” and “Postreadmission responders” were compared with those of the control group using multivariate logistic regression. “Pre-readmission responders” were also compared with “Postreadmission responders”.

“2nd-admission responders” were similarly compared with the control group for an exploratory analysis. Finally, “Postreadmission responders” and “2nd-admission responders” were compared in another exploratory analysis since both these groups responded to the survey after being exposed to the readmission, even though the “Postreadmission responders” group is administratively linked to the index admission.

The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

There were 43,737 survey responders, among whom 4,707 were subsequently readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Among the readmitted patients who responded to the surveys linked to their index admission, only 15.8% returned the survey before readmission (pre-readmission responders’) and 84.2% returned the survey after readmission (postreadmission responders). Additionally, 1,663 patients responded to experience surveys linked to their readmission. There were 37,365 patients in the control arm (ie, patients who responded to the survey and were not readmitted within 30 days of discharge or in the prior 30 days; Figure 1). The readmission rate among survey responders was 10.6%. Among the readmitted patients, the median number of days to readmission was 10 days while the median number of days to respond to the survey for this group was 33 days. Among the nonreadmitted patients, the median number of days to return the survey was 29 days.

We also conducted an exploratory analysis of the postreadmission responders, comparing them with patients who received patient-experience surveys linked to their second admission in 30 days. Both of these groups were exposed to a readmission before they completed the surveys. There were no significant differences between these two groups on patient experience scores. Additionally, the patients who received the survey linked to their readmission had a broad dissatisfaction pattern on HCAHPS survey items that appeared similar to that of the postreadmission group when compared to the non-readmitted group (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis of prospectively collected Press Ganey and HCAHPS patient-experience survey data, we found that the overwhelming majority of patients readmitted within 30 days of discharge respond to HCAHPS surveys after readmission even though the survey is sent linked to the first admission. This is not unexpected since the median time to survey response is 33 days for this group, while median time to readmission is 10 days. The dissatisfaction pattern of Postreadmission responders was similar to those who responded to the survey linked to the readmission. When a patient is readmitted prior to completing the survey, their responses appear to reflect the cumulative experience of the index admission and the readmission. The lower scores of those who respond to the survey after their readmission appear to be a driver for lower patient-experience scores related to readmissions. Overall, readmission was associated with lower scores on items in five of the nine domains used to calculate patient experience related payments under VBP.16

These findings have important implications in inferring the direction of potential causal relationship between readmissions and patient experience at the hospital level. Additionally, these patients show broad dissatisfaction with areas beyond physician communication and discharge planning. These include staff responsiveness, phlebotomy, meals, hospital cleanliness, and noise level. This pattern of dissatisfaction may represent impatience and frustration with spending additional time in the hospital environment.

Our results are consistent with findings of many of the earlier studies, but our study goes a step further by using patient-level data and incorporating survey response time in our analysis.3,7,9,10 By separating out the readmitted patients who responded to the survey prior to admission, we attempted to address the ability of patients’ perception of care to predict future readmissions. Our results do not support this idea, since pre-readmission responders had similar experience scores to non-readmitted patients. However, because of the low numbers of pre-readmission responders, the comparison lacks precision. Current HCAHPS and Press Ganey questions may lack the ability to predict future readmissions because of the timing of the survey (postdischarge) or the questions themselves.

Overall, postreadmission responders are dissatisfied with multiple domains of hospital care. Many of these survey responses may simply be related to general frustration. Alternatively, they may represent a patient population with a high degree of needs that are not as easily met by a hospital’s routine processes of care. Even though the readmission rates were 10.6% among survey responders, 14.6% of the survey responses were associated with readmissions after accounting for those who respond to surveys linked to readmission. These patients could have significant impact on cumulative experience scores.

Our study has a few limitations. First, it involves a single tertiary care academic center study, and our results may not be generalizable. Second, we did not adjust for some of the patient characteristics associated with readmissions. Patients who were admitted within 30 days are different than those not readmitted based on payor, race, length of stay, and severity of illness, and we did not adjust for these factors in our analysis. This was intentional, however. Our goal was to better understand the relationship between 30-day readmission and patient experience scores as they are used for hospital-level studies, VBP, and public reporting. For these purposes, the scores are not adjusted for factors, such as payor and length of stay. We did adjust for patient-mix adjustment factors used by CMS. Third, the response rates to the HCAHPS were low and may have biased the scores. However, HCAHPS is widely used for comparisons between hospitals has been validated, and our study results have implications with regard to comparing hospital-level performance. HCAHPS results are relevant to policy and have financial consequences.17 Fourth, our study did not directly compare whether the relationship between patient experience for the postreadmission group and nonreadmitted group was different from the relationship between the pre-readmission group and postreadmission group. It is possible that there is no difference in relationship between the groups. However, despite the small number of pre-readmission responders, these patients tended to have more favorable experience responses than those who responded after being readmitted, even after adjusting for response time. Although the P values are nonsignificant for many comparisons, the directionality of the effect is relatively consistent. Also, the vast majority of the patients fall in the postreadmission group, and these patients appear to drive the overall experience related to readmissions. Finally, since relatively few patients turned in surveys prior to readmission, we had limited power to detect a significant difference between these pre-readmission responders and nonreadmitted patients.

Our study has implications for policy makers, researchers, and providers. The HCAHPS scores of patients who are readmitted and completed the survey after being readmitted reflects their experience of both the index admission and the readmission. We did not find evidence to support that HCAHPS survey responses predict future readmissions at the patient level. Our findings do support the concept that lower readmissions rates (whether due to the patient population or processes of care that decrease readmission rates) may improve HCAHPS scores. We suggest caution in assuming that improving patient experience is likely to reduce readmission rates.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Patient experience and 30-day readmission are important measures of quality of care for hospitalized patients. Performance on both of these measures impact hospitals financially. Performance on the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Systems and Providers (HCAHPS) survey is linked to 25% of the incentive payment under Value Based Purchasing (VBP) Program.1 Starting in 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced the Readmission Reduction Program, penalizing hospitals financially for excessive readmissions.2

A relationship between patient experience and readmissions has been explored at the hospital level. Studies have mostly found that higher patient experience scores are associated with lower 30-day readmission rates. In a study of the relationship between 30-day risk-standardized readmission rates for three medical conditions (acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, and pneumonia) and patient experience, the authors noted that higher experience scores for overall care and discharge planning were associated with lower readmission rates for these conditions. They also concluded that patient experience scores were more predictive of 30-day readmission than clinical performance measures. Additionally, the authors predicted that if a hospital increased its total experience scores from the 25th percentile to the 75th percentile, there would be an associated decrease in readmissions by at least 2.3% for each of these conditions.3 Practice management companies and the media have cited this finding to conclude that higher patient experience drives clinical outcomes such as 30-day readmission and that patients are often the best judges of the quality of care delivered.4,5

Other hospital-level studies have found that high 30-day readmission rates are associated with lower overall experience scores in a mixed surgical patient population; worse reports of pain control and overall care in the colorectal surgery population; lower experience scores with discharge preparedness in vascular surgery patients; and lower experience scores with physician communication, nurse communication, and discharge preparedness.6-9 A patient-level study noted higher readmissions are associated with worse experience with physician and nursing communication along with a paradoxically better experience with discharge information.10

Because these studies used an observational design, they demonstrated associations rather than causality. An alternative hypothesis is that readmitted patients complete their patient experience survey after readmission and the low experience is the result, rather than the cause, of their readmission. For patients who are readmitted, it is unclear whether there is an opportunity to complete the survey prior to readmission and whether being readmitted may impact patient perception of quality of care. Using patient-level data, we sought to assess HCAHPS patient-experience responses linked to the index admission of the patients who were readmitted in 30 days and compare it with those patients who were not readmitted during this time period. We paid particular attention to when the surveys were returned.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected 10-year HCAHPS and Press Ganey patient survey data for a single tertiary care academic hospital.

Participants

All adult patients discharged from the hospital and who responded to the routinely sent patient-experience survey were included. Surveys were sent to a random sample of 50% of the discharged patients.

The exposure group was comprised of patients who responded to the survey and were readmitted within 30 days of discharge. After subtracting 5 days from the survey receipt date for expected delays related to mail delivery time and processing time, survey response date was calculated. The exposure group was further divided into patients who responded to the survey prior to their 30-day readmission (“Pre-readmission responders”) and those that responded to the survey after their readmission (“Postreadmission responders”). A sensitivity analysis was performed by changing the number of days subtracted from the survey receipt date by 2 days in either direction. This approach did not result in any significant changes in the results.

The control group comprised patients who were not readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge and who did not have an admission in the previous 30 days as well (“Not readmitted” group). An additional comparison group for exploratory analysis included patients who had experienced an admission in the prior 30 days but were not readmitted after the admission linked to the survey. These patients responded to the patient-experience surveys that were linked to their second admission in 30 days (“2nd-admission responders” group; Figure).

Time Periods

All survey responders from the third quarter of 2006 to the first quarter of 2016 were included in the study. Additionally, administrative data on non-responders were available from 7/2006 to 8/2012. These data were used to estimate response rates. Patient level experience and administrative data were obtained in a linked fashion for these time periods.

Instruments

Press Ganey and HCAHPS surveys were sent via mail in the same envelope. Fifty percent of the discharged patients were randomized to receive the surveys. The Press Ganey survey contained 33 items encompassing several subdomains, including room, meal, nursing, physician, ancillary staff, visitor, discharge, and overall experience.

The HCAHPS survey contained 29 CMS-mandated items, of which 21 are related to patient experience. The development, testing, and methods for administration and reporting of the HCAHPS survey have been previously described and studies using this instrument have been reported in the literature.11 Press Ganey patient satisfaction survey results have also been reported in the literature.12

Outcome Variables and Covariates

HCAHPS and Press Ganey experience survey individual item responses were the primary outcome variables of this study. Age, self-reported health status, education, primary language spoken, service line, and time taken to respond to the surveys served as the covariates. These variables are used by CMS for patient-mix adjustment and are collected on the HCAHPS survey. Additionally, the number of days to respond to the survey were included in all regression analysis to adjust for early responder effect.13-15

Statistical Analysis

“Percent top-box” scores were calculated for each survey item for patients in each group. The percent top-box scores were calculated as the percent of patients who responded “very good” for a given item on Press Ganey survey items and “always” or “definitely yes” or “yes” or “9” or “10” on HCAHPS survey items. CMS utilizes “percent top-box scores” to calculate payments under the VBP program and to report the results publicly. Numerous studies have also reported percent top-box scores for HCAHPS survey results.12

We hypothesized that whether patients complete the HCAHPS survey before or after the readmission influences their reporting of experience. To test this hypothesis, HCAHPS and Press Ganey item top-box scores of “Pre-readmission responders” and “Postreadmission responders” were compared with those of the control group using multivariate logistic regression. “Pre-readmission responders” were also compared with “Postreadmission responders”.

“2nd-admission responders” were similarly compared with the control group for an exploratory analysis. Finally, “Postreadmission responders” and “2nd-admission responders” were compared in another exploratory analysis since both these groups responded to the survey after being exposed to the readmission, even though the “Postreadmission responders” group is administratively linked to the index admission.

The Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

There were 43,737 survey responders, among whom 4,707 were subsequently readmitted within 30 days of discharge. Among the readmitted patients who responded to the surveys linked to their index admission, only 15.8% returned the survey before readmission (pre-readmission responders’) and 84.2% returned the survey after readmission (postreadmission responders). Additionally, 1,663 patients responded to experience surveys linked to their readmission. There were 37,365 patients in the control arm (ie, patients who responded to the survey and were not readmitted within 30 days of discharge or in the prior 30 days; Figure 1). The readmission rate among survey responders was 10.6%. Among the readmitted patients, the median number of days to readmission was 10 days while the median number of days to respond to the survey for this group was 33 days. Among the nonreadmitted patients, the median number of days to return the survey was 29 days.

We also conducted an exploratory analysis of the postreadmission responders, comparing them with patients who received patient-experience surveys linked to their second admission in 30 days. Both of these groups were exposed to a readmission before they completed the surveys. There were no significant differences between these two groups on patient experience scores. Additionally, the patients who received the survey linked to their readmission had a broad dissatisfaction pattern on HCAHPS survey items that appeared similar to that of the postreadmission group when compared to the non-readmitted group (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this retrospective analysis of prospectively collected Press Ganey and HCAHPS patient-experience survey data, we found that the overwhelming majority of patients readmitted within 30 days of discharge respond to HCAHPS surveys after readmission even though the survey is sent linked to the first admission. This is not unexpected since the median time to survey response is 33 days for this group, while median time to readmission is 10 days. The dissatisfaction pattern of Postreadmission responders was similar to those who responded to the survey linked to the readmission. When a patient is readmitted prior to completing the survey, their responses appear to reflect the cumulative experience of the index admission and the readmission. The lower scores of those who respond to the survey after their readmission appear to be a driver for lower patient-experience scores related to readmissions. Overall, readmission was associated with lower scores on items in five of the nine domains used to calculate patient experience related payments under VBP.16

These findings have important implications in inferring the direction of potential causal relationship between readmissions and patient experience at the hospital level. Additionally, these patients show broad dissatisfaction with areas beyond physician communication and discharge planning. These include staff responsiveness, phlebotomy, meals, hospital cleanliness, and noise level. This pattern of dissatisfaction may represent impatience and frustration with spending additional time in the hospital environment.

Our results are consistent with findings of many of the earlier studies, but our study goes a step further by using patient-level data and incorporating survey response time in our analysis.3,7,9,10 By separating out the readmitted patients who responded to the survey prior to admission, we attempted to address the ability of patients’ perception of care to predict future readmissions. Our results do not support this idea, since pre-readmission responders had similar experience scores to non-readmitted patients. However, because of the low numbers of pre-readmission responders, the comparison lacks precision. Current HCAHPS and Press Ganey questions may lack the ability to predict future readmissions because of the timing of the survey (postdischarge) or the questions themselves.

Overall, postreadmission responders are dissatisfied with multiple domains of hospital care. Many of these survey responses may simply be related to general frustration. Alternatively, they may represent a patient population with a high degree of needs that are not as easily met by a hospital’s routine processes of care. Even though the readmission rates were 10.6% among survey responders, 14.6% of the survey responses were associated with readmissions after accounting for those who respond to surveys linked to readmission. These patients could have significant impact on cumulative experience scores.

Our study has a few limitations. First, it involves a single tertiary care academic center study, and our results may not be generalizable. Second, we did not adjust for some of the patient characteristics associated with readmissions. Patients who were admitted within 30 days are different than those not readmitted based on payor, race, length of stay, and severity of illness, and we did not adjust for these factors in our analysis. This was intentional, however. Our goal was to better understand the relationship between 30-day readmission and patient experience scores as they are used for hospital-level studies, VBP, and public reporting. For these purposes, the scores are not adjusted for factors, such as payor and length of stay. We did adjust for patient-mix adjustment factors used by CMS. Third, the response rates to the HCAHPS were low and may have biased the scores. However, HCAHPS is widely used for comparisons between hospitals has been validated, and our study results have implications with regard to comparing hospital-level performance. HCAHPS results are relevant to policy and have financial consequences.17 Fourth, our study did not directly compare whether the relationship between patient experience for the postreadmission group and nonreadmitted group was different from the relationship between the pre-readmission group and postreadmission group. It is possible that there is no difference in relationship between the groups. However, despite the small number of pre-readmission responders, these patients tended to have more favorable experience responses than those who responded after being readmitted, even after adjusting for response time. Although the P values are nonsignificant for many comparisons, the directionality of the effect is relatively consistent. Also, the vast majority of the patients fall in the postreadmission group, and these patients appear to drive the overall experience related to readmissions. Finally, since relatively few patients turned in surveys prior to readmission, we had limited power to detect a significant difference between these pre-readmission responders and nonreadmitted patients.

Our study has implications for policy makers, researchers, and providers. The HCAHPS scores of patients who are readmitted and completed the survey after being readmitted reflects their experience of both the index admission and the readmission. We did not find evidence to support that HCAHPS survey responses predict future readmissions at the patient level. Our findings do support the concept that lower readmissions rates (whether due to the patient population or processes of care that decrease readmission rates) may improve HCAHPS scores. We suggest caution in assuming that improving patient experience is likely to reduce readmission rates.

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1. Hospital value-based purchasing. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/Hospital_VBPurchasing_Fact_Sheet_ICN907664.pdf. Accessed June 25, 2016.

2. Readmissions reduction program (HRRP). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed June 25, 2016.

3. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-48. PubMed

4. Buum HA, Duran-Nelson AM, Menk J, Nixon LJ. Duty-hours monitoring revisited: self-report may not be adequate. Am J Med. 2013;126(4):362-365. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.12.003 PubMed

5. Choma NN, Vasilevskis EE, Sponsler KC, Hathaway J, Kripalani S. Effect of the ACGME 16-hour rule on efficiency and quality of care: duty hours 2.0. JAMA Int Med. 2013;173(9):819-821. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3014 PubMed

6. Brooke BS, Samourjian E, Sarfati MR, Nguyen TT, Greer D, Kraiss LW. RR3. Patient-reported readiness at time of discharge predicts readmission following vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(6):188S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.04.356

7. Duraes LC, Merlino J, Stocchi L, et al. 756 readmission decreases patient satisfaction in colorectal surgery. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):S-1029. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(14)63751-3

8. Mitchell JP. Association of provider communication and discharge instructions on lower readmissions. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):33-40. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460126.88382.13 PubMed

9. Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient satisfaction and quality of surgical care in US hospitals. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):2-8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000765 PubMed

10. Hachem F, Canar J, Fullam M, Andrew S, Hohmann S, Johnson C. The relationships between HCAHPS communication and discharge satisfaction items and hospital readmissions. Patient Exp J. 2014;1(2):71-77.

11. Irby DM, Cooke M, Lowenstein D, Richards B. The academy movement: a structural approach to reinvigorating the educational mission. Acad Med. 2004;79(8):729-736. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200408000-00003 PubMed

12. Siddiqui ZK, Zuccarelli R, Durkin N, Wu AW, Brotman DJ. Changes in patient satisfaction related to hospital renovation: experience with a new clinical building. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):165-171. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2297 PubMed

13. Nair BR, Coughlan JL, Hensley MJ. Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching. Med Educ. 1997;31(5):341-346. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1997.00673.x PubMed

14. Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, Goldstein E, et al. Effects of survey mode, patient mix, and nonresponse on CAHPS® hospital survey scores. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;44(2p1):501-518. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00914.x PubMed

15. Saunders CL, Elliott MN, Lyratzopoulos G, Abel GA. Do differential response rates to patient surveys between organizations lead to unfair performance comparisons?: evidence from the English Cancer Patient Experience Survey. Medical care. 2016;54(1):45. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000457 PubMed

16. Sabel E, Archer J. “Medical education is the ugly duckling of the medical world” and other challenges to medical educators’ identity construction: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1474-1480. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000420 PubMed

17. O’Malley AJ, Zaslavsky AM, Elliott MN, Zaborski L, Cleary PD. Case‐Mix adjustment of the CAHPS® Hospital Survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6p2):2162-2181. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00470.x

1. Hospital value-based purchasing. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/Hospital_VBPurchasing_Fact_Sheet_ICN907664.pdf. Accessed June 25, 2016.

2. Readmissions reduction program (HRRP). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.html. Accessed June 25, 2016.

3. Boulding W, Glickman SW, Manary MP, Schulman KA, Staelin R. Relationship between patient satisfaction with inpatient care and hospital readmission within 30 days. Am J Manag Care. 2011;17(1):41-48. PubMed

4. Buum HA, Duran-Nelson AM, Menk J, Nixon LJ. Duty-hours monitoring revisited: self-report may not be adequate. Am J Med. 2013;126(4):362-365. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2012.12.003 PubMed

5. Choma NN, Vasilevskis EE, Sponsler KC, Hathaway J, Kripalani S. Effect of the ACGME 16-hour rule on efficiency and quality of care: duty hours 2.0. JAMA Int Med. 2013;173(9):819-821. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3014 PubMed

6. Brooke BS, Samourjian E, Sarfati MR, Nguyen TT, Greer D, Kraiss LW. RR3. Patient-reported readiness at time of discharge predicts readmission following vascular surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2015;61(6):188S. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2015.04.356

7. Duraes LC, Merlino J, Stocchi L, et al. 756 readmission decreases patient satisfaction in colorectal surgery. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):S-1029. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(14)63751-3

8. Mitchell JP. Association of provider communication and discharge instructions on lower readmissions. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):33-40. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460126.88382.13 PubMed

9. Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient satisfaction and quality of surgical care in US hospitals. Ann Surg. 2015;261(1):2-8. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000765 PubMed

10. Hachem F, Canar J, Fullam M, Andrew S, Hohmann S, Johnson C. The relationships between HCAHPS communication and discharge satisfaction items and hospital readmissions. Patient Exp J. 2014;1(2):71-77.

11. Irby DM, Cooke M, Lowenstein D, Richards B. The academy movement: a structural approach to reinvigorating the educational mission. Acad Med. 2004;79(8):729-736. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200408000-00003 PubMed

12. Siddiqui ZK, Zuccarelli R, Durkin N, Wu AW, Brotman DJ. Changes in patient satisfaction related to hospital renovation: experience with a new clinical building. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(3):165-171. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2297 PubMed

13. Nair BR, Coughlan JL, Hensley MJ. Student and patient perspectives on bedside teaching. Med Educ. 1997;31(5):341-346. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1997.00673.x PubMed

14. Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, Goldstein E, et al. Effects of survey mode, patient mix, and nonresponse on CAHPS® hospital survey scores. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;44(2p1):501-518. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00914.x PubMed

15. Saunders CL, Elliott MN, Lyratzopoulos G, Abel GA. Do differential response rates to patient surveys between organizations lead to unfair performance comparisons?: evidence from the English Cancer Patient Experience Survey. Medical care. 2016;54(1):45. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000457 PubMed

16. Sabel E, Archer J. “Medical education is the ugly duckling of the medical world” and other challenges to medical educators’ identity construction: a qualitative study. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1474-1480. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000420 PubMed

17. O’Malley AJ, Zaslavsky AM, Elliott MN, Zaborski L, Cleary PD. Case‐Mix adjustment of the CAHPS® Hospital Survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6p2):2162-2181. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00470.x

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

Does provider self-reporting of etiquette behaviors improve patient experience? A randomized controlled trial

Physicians have historically had limited adoption of strategies to improve patient experience and often cite suboptimal data and lack of evidence-driven strategies. 1,2 However, public reporting of hospital-level physician domain Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) experience scores, and more recent linking of payments to performance on patient experience metrics, have been associated with significant increases in physician domain scores for most of the hospitals. 3 Hospitals and healthcare organizations have deployed a broad range of strategies to engage physicians. These include emphasizing the relationship between patient experience and patient compliance, complaints, and malpractice lawsuits; appealing to physicians’ sense of competitiveness by publishing individual provider experience scores; educating physicians on HCAHPS and providing them with regularly updated data; and development of specific techniques for improving patient-physician interaction. 4-8

Studies show that educational curricula on improving etiquette and communication skills for physicians lead to improvement in patient experience, and many such training programs are available to hospitals for a significant cost.9-15 Other studies that have focused on providing timely and individual feedback to physicians using tools other than HCAHPS have shown improvement in experience in some instances. 16,17 However, these strategies are resource intensive, require the presence of an independent observer in each patient room, and may not be practical in many settings. Further, long-term sustainability may be problematic.

Since the goal of any educational intervention targeting physicians is routinizing best practices, and since resource-intensive strategies of continuous assessment and feedback may not be practical, we sought to test the impact of periodic physician self-reporting of their etiquette-based behavior on their patient experience scores.

METHODS

Subjects

Hospitalists from 4 hospitals (2 community and 2 academic) that are part of the same healthcare system were the study subjects. Hospitalists who had at least 15 unique patients responding to the routinely administered Press Ganey experience survey during the baseline period were considered eligible. Eligible hospitalists were invited to enroll in the study if their site director confirmed that the provider was likely to stay with the group for the subsequent 12-month study period.

Randomization, Intervention and Control Group

Hospitalists were randomized to the study arm or control arm (1:1 randomization). Study arm participants received biweekly etiquette behavior (EB) surveys and were asked to report how frequently they performed 7 best-practice bedside etiquette behaviors during the previous 2-week period (Table 1). These behaviors were pre-defined by a consensus group of investigators as being amenable to self-report and commonly considered best practice as described in detail below. Control-arm participants received similarly worded survey on quality improvement behaviors (QIB) that would not be expected to impact patient experience (such as reviewing medications to ensure that antithrombotic prophylaxis was prescribed, Table 1).

Baseline and Study Periods

A 12-month period prior to the enrollment of each hospitalist was considered the baseline period for that individual. Hospitalist eligibility was assessed based on number of unique patients for each hospitalist who responded to the survey during this baseline period. Once enrolled, baseline provider-level patient experience scores were calculated based on the survey responses during this 12-month baseline period. Baseline etiquette behavior performance of the study was calculated from the first survey. After the initial survey, hospitalists received biweekly surveys (EB or QIB) for the 12-month study period for a total of 26 surveys (including the initial survey).

Survey Development, Nature of Survey, Survey Distribution Methods

The EB and QIB physician self-report surveys were developed through an iterative process by the study team. The EB survey included elements from an etiquette-based medicine checklist for hospitalized patients described by Kahn et al. 18 We conducted a review of literature to identify evidence-based practices.19-22 Research team members contributed items on best practices in etiquette-based medicine from their experience. Specifically, behaviors were selected if they met the following 4 criteria: 1) performing the behavior did not lead to significant increase in workload and was relatively easy to incorporate in the work flow; 2) occurrence of the behavior would be easy to note for any outside observer or the providers themselves; 3) the practice was considered to be either an evidence-based or consensus-based best-practice; 4) there was consensus among study team members on including the item. The survey was tested for understandability by hospitalists who were not eligible for the study.

The EB survey contained 7 items related to behaviors that were expected to impact patient experience. The QIB survey contained 4 items related to behaviors that were expected to improve quality (Table 1). The initial survey also included questions about demographic characteristics of the participants.

Survey questionnaires were sent via email every 2 weeks for a period of 12 months. The survey questionnaire became available every other week, between Friday morning and Tuesday midnight, during the study period. Hospitalists received daily email reminders on each of these days with a link to the survey website if they did not complete the survey. They had the opportunity to report that they were not on service in the prior week and opt out of the survey for the specific 2-week period. The survey questions were available online as well as on a mobile device format.

Provider Level Patient Experience Scores

Provider-level patient experience scores were calculated from the physician domain Press Ganey survey items, which included the time that the physician spent with patients, the physician addressed questions/worries, the physician kept patients informed, the friendliness/courtesy of physician, and the skill of physician. Press Ganey responses were scored from 1 to 5 based on the Likert scale responses on the survey such that a response “very good” was scored 5 and a response “very poor” was scored 1. Additionally, physician domain HCAHPS item (doctors treat with courtesy/respect, doctors listen carefully, doctors explain in way patients understand) responses were utilized to calculate another set of HCAHPS provider level experience scores. The responses were scored as 1 for “always” response and “0” for any other response, consistent with CMS dichotomization of these results for public reporting. Weighted scores were calculated for individual hospitalists based on the proportion of days each hospitalist billed for the hospitalization so that experience scores of patients who were cared for by multiple providers were assigned to each provider in proportion to the percent of care delivered.23 Separate composite physician scores were generated from the 5 Press Ganey and for the 3 HCAHPS physician items. Each item was weighted equally, with the maximum possible for Press Ganey composite score of 25 (sum of the maximum possible score of 5 on each of the 5 Press Ganey items) and the HCAHPS possible total was 3 (sum of the maximum possible score of 1 on each of the 3 HCAHPS items).

ANALYSIS AND STATISTICAL METHODS

We analyzed the data to assess for changes in frequency of self-reported behavior over the study period, changes in provider-level patient experience between baseline and study period, and the association between the these 2 outcomes. The self-reported etiquette-based behavior responses were scored as 1 for the lowest response (never) to 4 as the highest (always). With 7 questions, the maximum attainable score was 28. The maximum score was normalized to 100 for ease of interpretation (corresponding to percentage of time etiquette behaviors were employed, by self-report). Similarly, the maximum attainable self-reported QIB-related behavior score on the 4 questions was 16. This was also converted to 0-100 scale for ease of comparison.

Two additional sets of analyses were performed to evaluate changes in patient experience during the study period. First, the mean 12-month provider level patient experience composite score in the baseline period was compared with the 12-month composite score during the 12-month study period for the study group and the control group. These were assessed with and without adjusting for age, sex, race, and U.S. medical school graduate (USMG) status. In the second set of unadjusted and adjusted analyses, changes in biweekly composite scores during the study period were compared between the intervention and the control groups while accounting for correlation between observations from the same physician using mixed linear models. Linear mixed models were used to accommodate correlations among multiple observations made on the same physician by including random effects within each regression model. Furthermore, these models allowed us to account for unbalanced design in our data when not all physicians had an equal number of observations and data elements were collected asynchronously.24 Analyses were performed in R version 3.2.2 (The R Project for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria); linear mixed models were performed using the ‘nlme’ package.25

We hypothesized that self-reporting on biweekly surveys would result in increases in the frequency of the reported behavior in each arm. We also hypothesized that, because of biweekly reflection and self-reporting on etiquette-based bedside behavior, patient experience scores would increase in the study arm.

RESULTS

Of the 80 hospitalists approached to participate in the study, 64 elected to participate (80% participation rate). The mean response rate to the survey was 57.4% for the intervention arm and 85.7% for the control arm. Higher response rates were not associated with improved patient experience scores. Of the respondents, 43.1% were younger than 35 years of age, 51.5% practiced in academic settings, and 53.1% were female. There was no statistical difference between hospitalists’ baseline composite experience scores based on gender, age, academic hospitalist status, USMG status, and English as a second language status. Similarly, there were no differences in poststudy composite experience scores based on physician characteristics.

Physicians reported high rates of etiquette-based behavior at baseline (mean score, 83.9+/-3.3), and this showed moderate improvement over the study period (5.6 % [3.9%-7.3%, P < 0.0001]). Similarly, there was a moderate increase in frequency of self-reported behavior in the control arm (6.8% [3.5%-10.1%, P < 0.0001]). Hospitalists reported on 80.7% (77.6%-83.4%) of the biweekly surveys that they “almost always” wrapped up by asking, “Do you have any other questions or concerns” or something similar. In contrast, hospitalists reported on only 27.9% (24.7%-31.3%) of the biweekly survey that they “almost always” sat down in the patient room.

The composite physician domain Press Ganey experience scores were no different for the intervention arm and the control arm during the 12-month baseline period (21.8 vs. 21.7; P = 0.90) and the 12-month intervention period (21.6 vs. 21.5; P = 0.75). Baseline self-reported behaviors were not associated with baseline experience scores. Similarly, there were no differences between the arms on composite physician domain HCAHPS experience scores during baseline (2.1 vs. 2.3; P = 0.13) and intervention periods (2.2 vs. 2.1; P = 0.33).

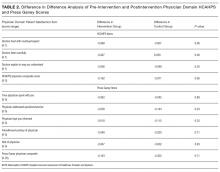

The difference in difference analysis of the baseline and postintervention composite between the intervention arm and the control arm was not statistically significant for Press Ganey composite physician experience scores (-0.163 vs. -0.322; P = 0.71) or HCAHPS composite physician scores (-0.162 vs. -0.071; P = 0.06). The results did not change when controlled for survey response rate (percentage biweekly surveys completed by the hospitalist), age, gender, USMG status, English as a second language status, or percent clinical effort. The difference in difference analysis of the individual Press Ganey and HCAHPS physician domain items that were used to calculate the composite score was also not statistically significant (Table 2).

Changes in self-reported etiquette-based behavior were not associated with any changes in composite Press Ganey and HCAHPS experience score or individual items of the composite experience scores between baseline and intervention period. Similarly, biweekly self-reported etiquette behaviors were not associated with composite and individual item experience scores derived from responses of the patients discharged during the same 2-week reporting period. The intra-class correlation between observations from the same physician was only 0.02%, suggesting that most of the variation in scores was likely due to patient factors and did not result from differences between physicians.

DISCUSSION

This 12-month randomized multicenter study of hospitalists showed that repeated self-reporting of etiquette-based behavior results in modest reported increases in performance of these behaviors. However, there was no associated increase in provider level patient experience scores at the end of the study period when compared to baseline scores of the same physicians or when compared to the scores of the control group. The study demonstrated feasibility of self-reporting of behaviors by physicians with high participation when provided modest incentives.

Educational and feedback strategies used to improve patient experience are very resource intensive. Training sessions provided at some hospitals may take hours, and sustained effects are unproved. The presence of an independent observer in patient rooms to generate feedback for providers is not scalable and sustainable outside of a research study environment.9-11,15,17,26-29 We attempted to use physician repeated self-reporting to reinforce the important and easy to adopt components of etiquette-based behavior to develop a more easily sustainable strategy. This may have failed for several reasons.

When combining “always” and “usually” responses, the physicians in our study reported a high level of etiquette behavior at baseline. If physicians believe that they are performing well at baseline, they would not consider this to be an area in need of improvement. Bigger changes in behavior may have been possible had the physicians rated themselves less favorably at baseline. Inflated or high baseline self-assessment of performance might also have led to limited success of other types of educational interventions had they been employed.

Studies published since the rollout of our study have shown that physicians significantly overestimate how frequently they perform these etiquette behaviors.30,31 It is likely that was the case in our study subjects. This may, at best, indicate that a much higher change in the level of self-reported performance would be needed to result in meaningful actual changes, or worse, may render self-reported etiquette behavior entirely unreliable. Interventions designed to improve etiquette-based behavior might need to provide feedback about performance.

A program that provides education on the importance of etiquette-based behaviors, obtains objective measures of performance of these behaviors, and offers individualized feedback may be more likely to increase the desired behaviors. This is a limitation of our study. However, we aimed to test a method that required limited resources. Additionally, our method for attributing HCAHPS scores to an individual physician, based on weighted scores that were calculated according to the proportion of days each hospitalist billed for the hospitalization, may be inaccurate. It is possible that each interaction does not contribute equally to the overall score. A team-based intervention and experience measurements could overcome this limitation.

CONCLUSION

This randomized trial demonstrated the feasibility of self-assessment of bedside etiquette behaviors by hospitalists but failed to demonstrate a meaningful impact on patient experience through self-report. These findings suggest that more intensive interventions, perhaps involving direct observation, peer-to-peer mentoring, or other techniques may be required to impact significantly physician etiquette behaviors.

Disclosure

Johns Hopkins Hospitalist Scholars Program provided funding support. Dr. Qayyum is a consultant for Sunovion. The other authors have nothing to report.

1. Blumenthal D, Kilo CM. A report card on continuous quality improvement. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):625-648. PubMed

2. Shortell SM, Bennett CL, Byck GR. Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: What it will take to accelerate progress. Milbank Q. 1998;76(4):593-624. PubMed

3. Mann RK, Siddiqui Z, Kurbanova N, Qayyum R. Effect of HCAHPS reporting on patient satisfaction with physician communication. J Hosp Med. 2015;11(2):105-110. PubMed

4. Rivers PA, Glover SH. Health care competition, strategic mission, and patient satisfaction: research model and propositions. J Health Organ Manag. 2008;22(6):627-641. PubMed

5. Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):237-251. PubMed

6. Stelfox HT, Gandhi TK, Orav EJ, Gustafson ML. The relation of patient satisfaction with complaints against physicians and malpractice lawsuits. Am J Med. 2005;118(10):1126-1133. PubMed

7. Rodriguez HP, Rodday AM, Marshall RE, Nelson KL, Rogers WH, Safran DG. Relation of patients’ experiences with individual physicians to malpractice risk. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20(1):5-12. PubMed

8. Cydulka RK, Tamayo-Sarver J, Gage A, Bagnoli D. Association of patient satisfaction with complaints and risk management among emergency physicians. J Emerg Med. 2011;41(4):405-411. PubMed

9. Windover AK, Boissy A, Rice TW, Gilligan T, Velez VJ, Merlino J. The REDE model of healthcare communication: Optimizing relationship as a therapeutic agent. Journal of Patient Experience. 2014;1(1):8-13.

10. Chou CL, Hirschmann K, Fortin AH 6th, Lichstein PR. The impact of a faculty learning community on professional and personal development: the facilitator training program of the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):1051-1056. PubMed

11. Kennedy M, Denise M, Fasolino M, John P, Gullen M, David J. Improving the patient experience through provider communication skills building. Patient Experience Journal. 2014;1(1):56-60.

12. Braverman AM, Kunkel EJ, Katz L, et al. Do I buy it? How AIDET™ training changes residents’ values about patient care. Journal of Patient Experience. 2015;2(1):13-20.

13. Riess H, Kelley JM, Bailey RW, Dunn EJ, Phillips M. Empathy training for resident physicians: a randomized controlled trial of a neuroscience-informed curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1280-1286. PubMed

14. Rothberg MB, Steele JR, Wheeler J, Arora A, Priya A, Lindenauer PK. The relationship between time spent communicating and communication outcomes on a hospital medicine service. J Gen Internl Med. 2012;27(2):185-189. PubMed

15. O’Leary KJ, Cyrus RM. Improving patient satisfaction: timely feedback to specific physicians is essential for success. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):555-556. PubMed

16. Indovina K, Keniston A, Reid M, et al. Real‐time patient experience surveys of hospitalized medical patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;10(8):497-502. PubMed

17. Banka G, Edgington S, Kyulo N, et al. Improving patient satisfaction through physician education, feedback, and incentives. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(8):497-502. PubMed

18. Kahn MW. Etiquette-based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1988-1989. PubMed

19. Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):199-201. PubMed

20. Francis JJ, Pankratz VS, Huddleston JM. Patient satisfaction associated with correct identification of physicians’ photographs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(6):604-608. PubMed

21. Strasser F, Palmer JL, Willey J, et al. Impact of physician sitting versus standing during inpatient oncology consultations: patients’ preference and perception of compassion and duration. A randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29(5):489-497. PubMed

22. Dudas RA, Lemerman H, Barone M, Serwint JR. PHACES (Photographs of Academic Clinicians and Their Educational Status): a tool to improve delivery of family-centered care. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(2):138-145. PubMed

23. Herzke C, Michtalik H, Durkin N, et al. A method for attributing patient-level metrics to rotating providers in an inpatient setting. J Hosp Med. Under revision.

24. Holden JE, Kelley K, Agarwal R. Analyzing change: a primer on multilevel models with applications to nephrology. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28(5):792-801. PubMed

25. Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D. Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models. R package version. 2007;3:57.