User login

Rotator cuff disease accounts for as many as 65% of shoulder-related visits to physicians’ offices,1 yet the natural course of rotator cuff tears is still not well understood.2 Treatment options are controversial because both conservative and surgical management have been successful. Physical therapy is a durable and reliable treatment option, but there are concerns about long-term progression of the tear.3 Surgical arthroscopic techniques, which result in less morbidity than open surgery, have improved overall surgical care; as such, the rate of rotator cuff procedures has increased significantly.4

Our goal in this article is to provide clinical guidance to the primary care provider. We review management options for rotator cuff injury; summarize considerations for proceeding with conservative or surgical management; and discuss surgical risks and complications.

Conservative management: Who is most likely to benefit?

The choice of treatment for rotator cuff injury depends on a host of variables, including shoulder dominance, duration of symptoms, type of tear (partial or full), age, demands (activity level, occupation, sport), and comorbidities (diabetes, tobacco use). Treatment goals include resolution of pain, normalized range of motion and strength, and restored arm and shoulder function.5

Initial nonoperative management is indicated in patients who

- have a partial-thickness tear (a notable exception is young patients with traumatic injury),6

- have lower functional demands and moderate symptoms, or

- refuse surgery.7

Patients who respond to nonoperative management will, typically, do so within 6 to 12 weeks.5,8

Few randomized, controlled trials have compared conservative and surgical management of rotator cuff tears; furthermore, the findings of these studies have been mixed. Nonoperative management has been shown to be the favored initial treatment for isolated, symptomatic, nontraumatic, supraspinatus tears in older patients.9 In a recent study,10 5-year outcomes were examined in a prospective cohort enrolled in a rotator cuff treatment program: Approximately 75% of patients remained successfully treated with nonoperative management, and clinical outcomes of the operative and nonoperative groups were not significantly different at 5-year follow-up. Investigators concluded that nonoperative treatment is effective for many patients who have a chronic, full-thickness rotator cuff tear.

In a study investigating the treatment of degenerative rotator cuff tear, patients were randomly treated using an operative or nonoperative protocol. No differences in functional outcomes were observed at 1 year after treatment; however, surgical treatment significantly improved subjective parameters of pain and disability.11 A similar study suggested statistically significant improvement in outcomes for patients managed operatively, compared with those treated nonoperatively, but differences in shoulder outcome and the visual analog pain score were small and failed to meet thresholds considered clinically significant. Larger studies, with longer follow-up, are required to determine whether clinical differences between these types of treatment become more evident over time.12

Continue to: A look at nonoperative options and outcomes

A look at nonoperative options and outcomes

Surveillance. Rotator cuff disease of the supraspinatus tendon often results from a degenerative process that progresses to partial and, eventually, full-thickness tearing.8 Once a tear develops, progression is difficult to predict. Many rotator cuff tears grow larger over time; this progression is commonly associated with new or increased pain and weakness, or both. Although asymptomatic progression of a tear is uncommon, many patients—and physicians—are apprehensive about proceeding with nonoperative treatment for a full-thickness tear.8

To diminish such fears, surveillance can include regular assessment of shoulder motion and strength, with consideration of repeat imaging until surgery is performed or the patient is no longer a surgical candidate or interested in surgical treatment.7 Patients and providers need to remain vigilant because tears that are initially graded as repairable can become irreparable if the tendon retracts or there is fatty infiltration of the muscle belly. Results of secondary surgical repair following failed prolonged nonoperative treatment tend to be inferior to results seen in patients who undergo primary tendon repair.7

Analgesics. Simple analgesics, such as acetaminophen, are a low-risk first-line option for pain relief; however, there are limited data on the efficacy of acetaminophen in rotator cuff disease. A topical or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), or both, can be considered, but potential contraindications, such as gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular risks, should be monitored.13 Avoid opioids, given the potential for abuse, except during the immediate postoperative period.5

Glucocorticoid injection. Injection of a glucocorticoid drug into the subacromial space should be considered in patients whose pain interferes with sleep, limits activities of daily living, or hinders the ability to participate in physical therapy.5 A recent systematic review demonstrated that NSAIDs and glucocorticoids brought similar pain relief and active abduction at 4 to 6 weeks, but that glucocorticoids were significantly better at achieving remission of symptoms.14 There are no data comparing glucocorticoid preparations (ie, different glucocorticoids or anesthetics, dosages, volumes), and ultrasound guidance does not appear to be necessary for short-term pain relief.15 Note: Repeated injection has been shown to decrease the durability of surgically repaired tendons16; if a patient is a candidate for surgery, repeat injections should be carefully considered—and avoided if possible.

Physical therapy. The goals of physical therapy are activity modification, stretching the shoulder capsule, and strengthening the surrounding musculature (periscapular, rotator cuff, and deltoid). Patients advance through 3 phases of recovery: shoulder mobility, strengthening, and function (ie, joint reactivation to improve shoulder proprioception and coordination).

Continue to: A recent meta-analysis...

A recent meta-analysis17 found comparative evidence on treating rotator cuff tears with physical therapy to be inconclusive. At 1-year follow-up, there was no clinically significant difference between surgery and active physical therapy in either improving the Constant Shoulder Score (an assessment of function) or reducing pain caused by a rotator cuff tear. Therefore, the authors proposed, given the low risk of harm, a conservative approach should be the initial treatment modality for a tear.

A Cochrane review18 examined 60 eligible trials, in which the mean age of patients was 51 years and the mean duration of symptoms, 11 months. Overall, the review concluded that the effects of manual therapy and exercise might be similar to those of glucocorticoid injection and arthroscopic subacromial decompression. The authors noted that this conclusion is based on low-quality evidence, with only 1 study in the review that compared the combination of manual therapy and exercise to placebo.

Other conservative options. Ultrasound, topical nitroglycerin, topical lidocaine, glucocorticoid iontophoresis, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, massage, acupuncture, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, hyaluronic acid, and platelet-rich plasma have been used to treat rotator cuff disease. These modalities require further study, however, to determine their effectiveness for this indication.7,19

Who is a candidate for surgical management?

Although nonoperative treatment is preferred for rotator cuff tendinitis or tendinosis and partial-thickness tears, appropriate management of full-thickness tears is debatable.20 Some surgeons advocate early operative intervention of repairable full-thickness tears to prevent further progression and reduce the risk of long-term dysfunction.

The decision to pursue operative repair depends on

- patient characteristics (age, activity level, comorbidities),

- patient function (amount of disability caused by the tear),

- characteristics of the tear (length, depth, retraction), and

- chronicity of the tear (acuity).

Continue to: TABLE 1...

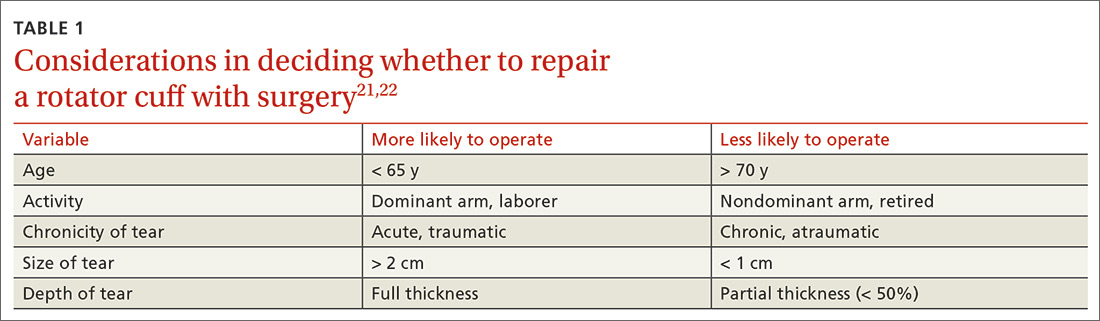

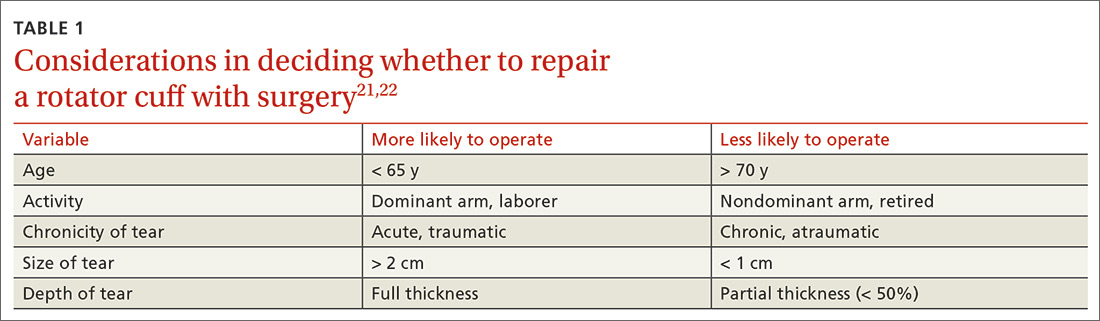

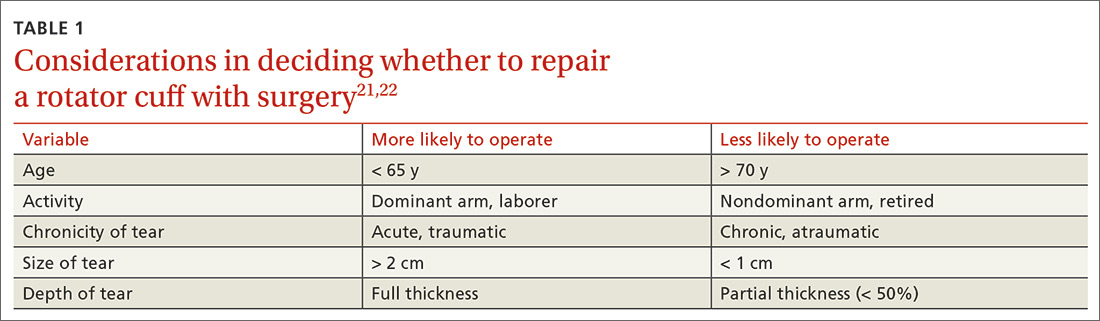

TABLE 121,22 highlights variables that influence the decision to proceed, or not to proceed, with operative intervention. Because enlargement of a tear usually exacerbates symptoms,23 patients with a tear who are successfully managed nonoperatively should be counseled on the potential of the tear to progress.

What are the surgical options?

Little clinical evidence favors one exposure technique over another. This equivalency has been demonstrated by a systematic review of randomized controlled trials comparing arthroscopic and mini-open rotator cuff repair, which showed no difference in function, pain, or range of motion.24 That conclusion notwithstanding, arthroscopic repair is increasingly popular because it results in less pain, initially, and faster return to work.20

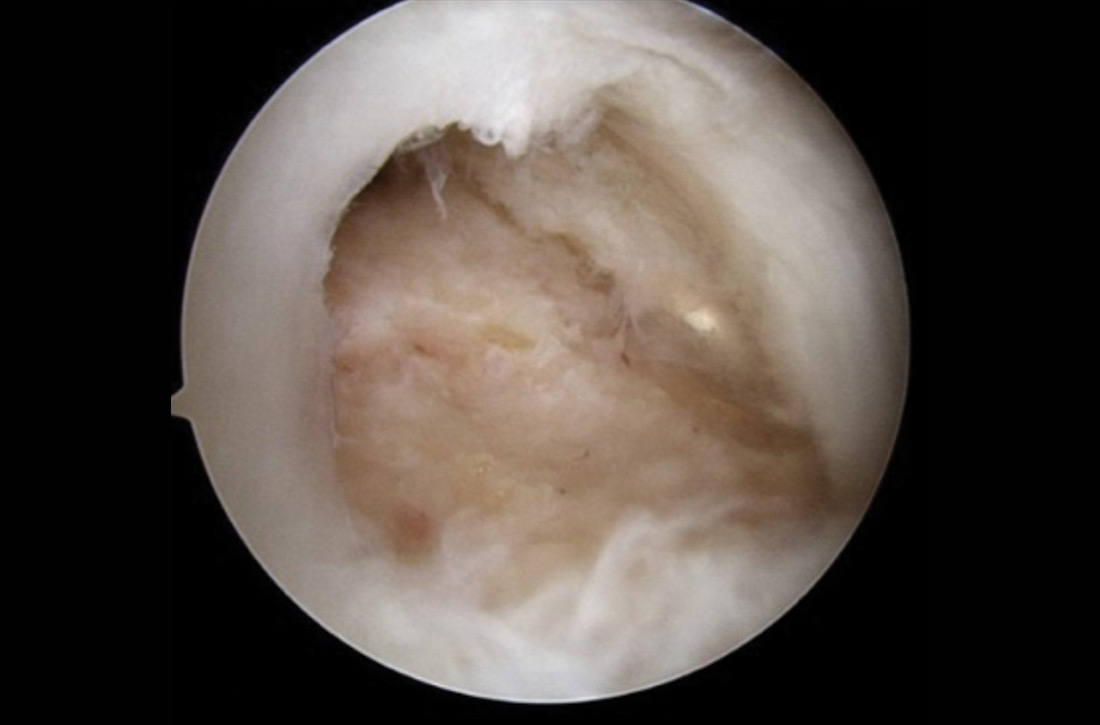

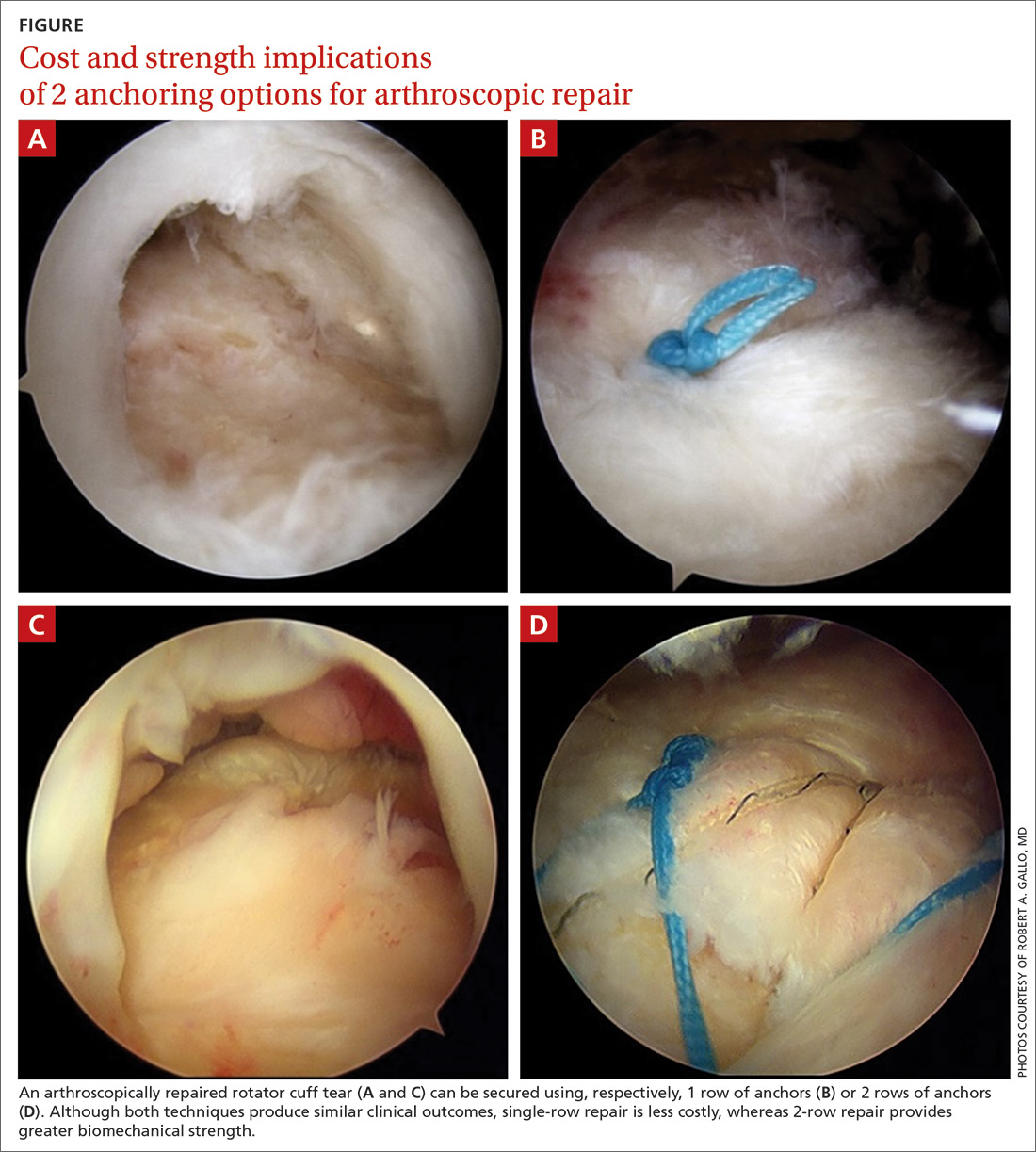

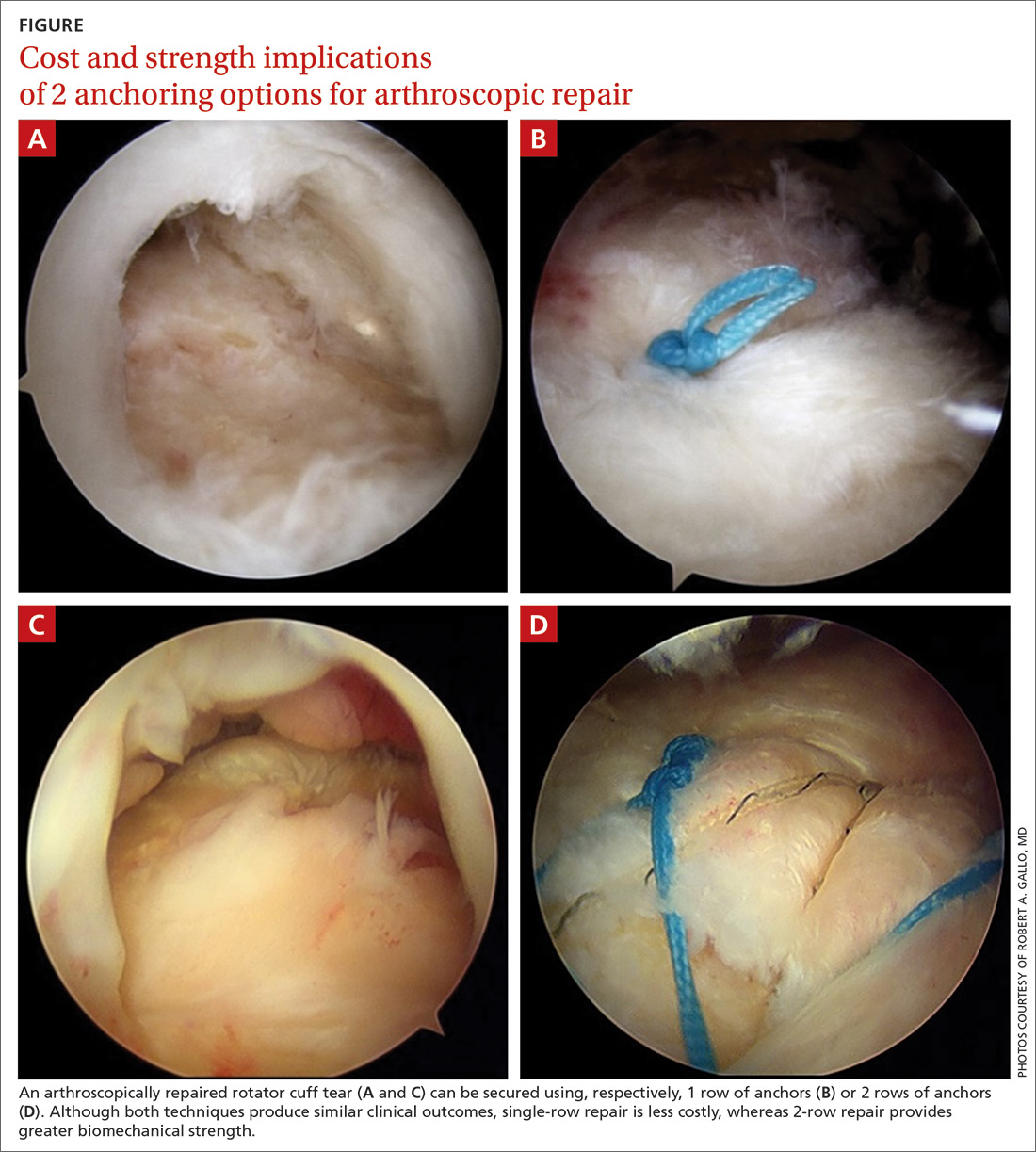

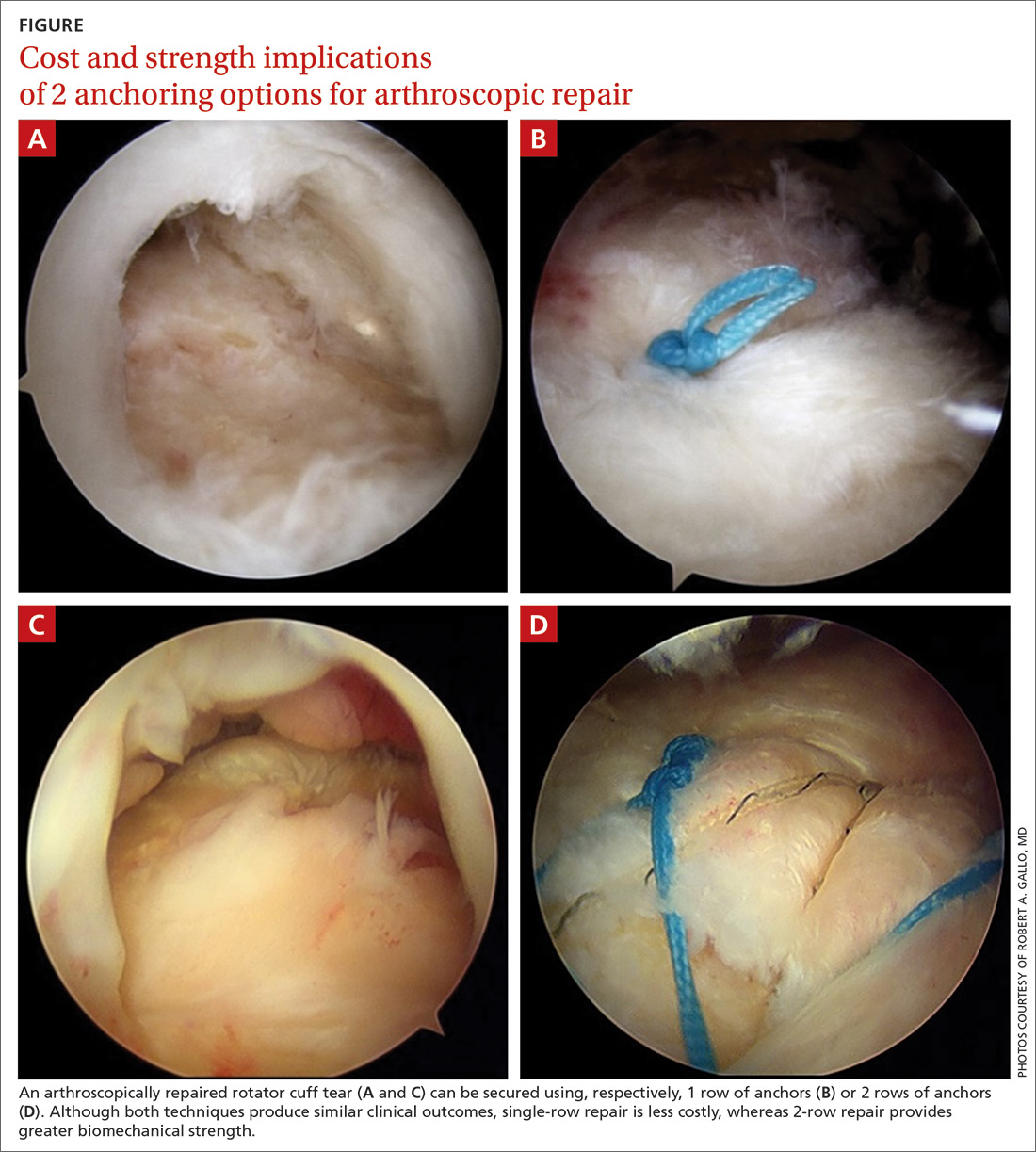

There is controversy among surgeons regarding the choice of fixation technique: Tendons can be secured using 1 or 2 rows of anchors (FIGURE). Advocates of single-row repair cite shorter surgical time, decreased cost, and equivalent outcomes; surgeons who favor double-row, or so-called transosseous-equivalent, repair claim that it provides better restoration of normal anatomy and biomechanical superiority.25,26

Regardless of technique, most patients are immobilized for 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively.27 Physical therapy usually commences within the first week or 2 postop, limited to passive motion for 6 to 12 weeks. Active motion and strengthening of rotator-cuff muscles often is initiated by 3 months postop, although this phase is sometimes delayed because of concern over slow tendon healing. Typically, patients make a full return to sports and manual work at 6 months postop. Patients experience most symptomatic improvement during the first 6 months following surgery, although functional gains can be realized for as long as 2 years after surgery.28

Most torn rotator cuffs can be fixed back to the greater tuberosity, but some chronic, massive, retracted tears lack the mobility to be repaired, or re-tear shortly after repair. Over time, the humeral head in a rotator cuff–deficient shoulder can migrate superiorly to abut the undersurface of the acromion, which can lead to significant glenohumeral osteoarthritis. To prevent or remedy elevation of the humeral head, salvage procedures—debridement, partial repair, spanning graft, tendon transfer, superior capsule reconstruction, balloon arthroplasty, reverse total shoulder replacement—can be used to alleviate pain and restore function. These procedures have significant limitations, however, and usually provide less favorable outcomes than standard repair.29-35

Continue to: Surgical outcomes

Surgical outcomes

Pain, function, and patient satisfaction outcomes following rotator cuff repair are generally favorable: 90% of patients are “happy” 6 months postop.28 Younger populations often have traumatic rotator cuff tears; they generally are interested in returning to sporting activities following their injury. Nearly 85% of younger patients who undergo rotator cuff repair return to sports, and 65.9% return to an equivalent level of play.36

Variables associated with an unfavorable outcome include increasing age, smoking, increased size of the tear, poor tendon quality, hyperlipidemia, workers’ compensation status, fatty infiltration of muscle, obesity, diabetes, and additional procedures to the biceps tendon and acromioclavicular joint performed at the time of rotator cuff repair.37-39 Interestingly, a study concluded that, if a patient expects a good surgical outcome, they are more likely to go on to report a favorable outcome—suggesting that a patient’s expectations might influence their actual outcome.40

Risks and complications

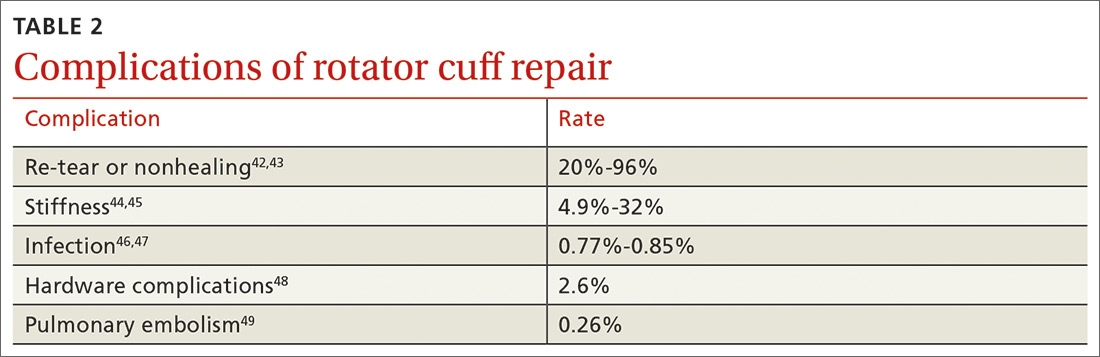

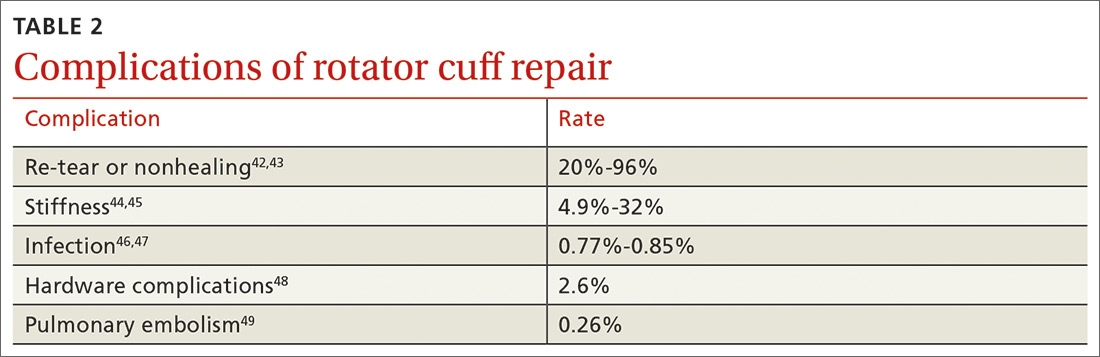

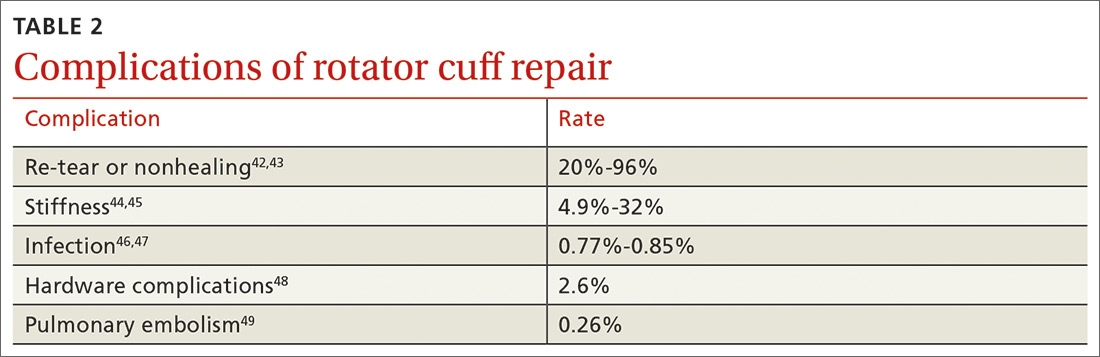

Although rotator cuff surgery has much lower morbidity than other orthopedic surgeries, it is not without risk of complications. If re-tears are excluded, postop complications have been reported in approximately 10% of patients.41 Common complications and their anticipated rate of occurrence are listed in TABLE 2.42-49

Re-tear of the surgically repaired tendon is the most common postop complication. Published re-tear rates range from 20% to 96%42,43 and generally correlate with initial tear size: A small tear is twice as likely to heal as a massive tear.50 That large range—a span of 76%—results from using a variety of methods to measure re-tear and might not have clinical meaning. A meta-analysis that examined more than 8000 shoulder surgeries reported an overall re-tear rate of 26.6%; however, both patients whose tendons healed and those who re-tore demonstrated clinical improvement.51 In a separate study, patients reported improvement in pain, function, range of motion, and satisfaction regardless of the integrity of the tendon; however, significant improvement in strength was seen only in those whose repair had healed.52

Postop stiffness is more common with arthroscopic repair than with open surgery, and with smaller rather than larger tears.53 Patient variables associated with an increased risk of postop adhesive capsulitis include workers’ compensation insurance, age < 50 years, and preoperative calcific tendonitis or adhesive capsulitis.53 Stiffness generally responds to physical therapy and rarely requires surgical lysis of adhesions or capsular release.

Continue to: Significant injury...

Significant injury to the deltoid muscle has become increasingly uncommon with the advancement of arthroscopic surgery. In traditional open surgery, detachment of the deltoid (and subsequent repair) is required to improve visualization; however, doing so can lead to atrophy and muscle rupture and dehiscence. Deltoid damage occurs in ≤ 60% of open surgeries but is negligible in arthroscopic and mini-open repairs, which involve splitting deltoid fibers to gain exposure of the underlying rotator cuff.54

SIDEBAR

Key takeaways in the management of rotator cuff injury

- Chronic, nontraumatic, and partial-thickness tears respond well to conservative management as first-line treatment. Poor surgical candidates should also be offered a trial of conservative therapy.

- Consider referral for surgical consultation if the patient does not respond to conservative therapy in 6 to 12 weeks; also, patients who have a full-thickness tear and young patients with traumatic injury should be referred for surgical consultation.

- Arthroscopy has become the preferred approach to rotator cuff repair because it is associated with less pain, fewer complications, and faster recovery.

- Patients should be counseled that recovery from surgical repair of a torn rotator cuff takes, on average, 6 months. Some massive or retracted rotator cuff injuries require more extensive procedures that increase healing time.

- Overall, patients are “happy” with rotator cuff repair at 6 months; clinical complications are uncommon, making surgery a suitable option in appropriately selected patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Cayce Onks, DO, MS, ATC, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine, Family and Community Medicine H154, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-0850; [email protected].

1. Vecchio P, Kavanagh R, Hazleman BL, et al. Shoulder pain in a community-based rheumatology clinic. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:440-442.

2. Eljabu W, Klinger HM, von Knoch M. The natural history of rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135:1055-1061.

3. Dunn WR, Kuhn JE, Sanders R, et al; MOON Shoulder Group. 2013 Neer Award: predictors of failure of nonoperative treatment of chronic, symptomatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:1303-1311.

4. Colvin AC, Egorova N, Harrison AK, et al. National trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:227-233.

5. Whittle S, Buchbinder R. In the clinic. Rotator cuff disease. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:ITC1-ITC15.

6. Lazarides AL, Alentorn-Geli E, Choi JHJ, et al. Rotator cuff tears in young patients: a different disease than rotator cuff tears in elderly patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1834-1843.

7. Petri M, Ettinger M, Brand S, et al. Non-operative management of rotator cuff tears. Open Orthop J. 2016;10:349-356.

8. Schmidt CC, Jarrett CD, Brown BT. Management of rotator cuff tears. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:399-408.

9. Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, et al. Treatment of nontraumatic rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial with two years of clinical and imaging follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1729-1737.

10. Boorman RS, More KD, Hollinshead RM, et al. What happens to patients when we do not repair their cuff tears? Five-year rotator cuff quality-of-life index outcomes following nonoperative treatment of patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:444-448.

11. Lambers Heerspink FO, van Raay JJ, Koorevaar RCT, et al. Comparing surgical repair with conservative treatment for degenerative rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1274-1281.

12. Piper CC, Hughes AJ, Ma Y, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for the management of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:572-576.

13. Boudreault J, Desmeules F, Roy J-S, et al. The efficacy of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:294-306.

14. Zheng X-Q, Li K, Wei Y-D, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus corticosteroid for treatment of shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:1824-1831.

15. Bloom JE, Rischin A, Johnston RV, et al. Image-guided versus blind glucocorticoid injection for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(8):CD009147.

16. Wiggins ME, Fadale PD, Ehrlich MG, et al. Effects of local injection of corticosteroids on the healing of ligaments. A follow-up report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1682-1691.

17. Ryösä A, Laimi K, Äärimaa V, et al. Surgery or conservative treatment for rotator cuff tear: a meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:1357-1363.

18. Page MJ, Green S, McBain B, et al. Manual therapy and exercise for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD012224.

19. Page MJ, Green S, Mrocki MA, et al. Electrotherapy modalities for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD012225.

20. Acevedo DC, Paxton ES, Williams GR, et al. A survey of expert opinion regarding rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e123.

21. Pedowitz RA, Yamaguchi K, Ahmad CS, et al. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline on: optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:163-167.

22. Thorpe A, Hurworth M, O’Sullivan P, et al. Rotator cuff disease: opinion regarding surgical criteria and likely outcome. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:291-295.

23. Mall NA, Kim HM, Keener JD, et al. Symptomatic progression of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective study of clinical and sonographic variables. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2623-2633.

24. Ji X, Bi C, Wang F, et al. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: an up-to-date meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:118-124.

25. Duquin TR, Buyea C, Bisson LJ. Which method of rotator cuff repair leads to the highest rate of structural healing? A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:835-841.

26. Choi S, Kim MK, Kim GM, et al. Factors associated with clinical and structural outcomes after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with a suture bridge technique in medium, large, and massive tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1675-1681.

27. Shen C, Tang Z-H, Hu J-Z, et al. Does immobilization after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair increase tendon healing? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134:1279-1285.

28. Gulotta LV, Nho SJ, Dodson CC, et al; . Prospective evaluation of arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs at 5 years: part I. Functional outcomes and radiographic healing rates. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:934-940.

29. Liem D, Lengers N, Dedy N, et al. Arthroscopic debridement of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:743-748.

30. Weber SC. Partial rotator cuff repair in massive rotator cuff tears: long-term follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:e171.

31. Lewington MR, Ferguson DP, Smith TD, et al. Graft utilization in the bridging reconstruction of irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:3149-3157.

32. Longo UG, Franceschetti E, Petrillo S, et al. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19:428-437.

33. Noyes MP, Denard PJ. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction: indications and outcomes. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2018;26:29-34.

34. Piekaar RSM, Bouman ICE, van Kampen PM, et al. Early promising outcome following arthroscopic implantation of the subacromial balloon spacer for treating massive rotator cuff tear. Musculoskeletal Surg. 2018;102:247-255.

35. Ek ETH, Neukom L, Catanzaro S, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears in patients younger than 65 years old: results after five to fifteen years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:1199-1208.

36. Klouche S, Lefevre N, Herman S, et al. Return to sport after rotator cuff tear repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:1877-1887.

37. Garcia GH, Liu JN, Wong A, et al. Hyperlipidemia increases the risk of retear after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:2086-2090.

38. Khair MM, Lehman J, Tsouris N, et al. A systematic review of preoperative fatty infiltration and rotator cuff outcomes. HSS J. 2016;12:170-176.

39. Lambers Heerspink FO, Dorrestijn O, van Raay JJAM, et al. Specific patient-related prognostic factors for rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1073-1080.

40. Henn RF 3rd, Kang L, Tashjian RZ, et al. Patients’ preoperative expectations predict the outcome of rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1913-1919.

41. Mansat P, Cofield RH, Kersten TE, et al. Complications of rotator cuff repair. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28:205-213.

42. Boileau P, Brassart N, Watkinson DJ, et al. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the supraspinatus: does the tendon really heal? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1229-1240.

43. Galatz LM, Ball CM, Teefey SA, et al. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:219-224.

44. Aydin N, Kocaoglu B, Guven O. Single-row versus double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in small- to medium-sized tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:722-725.

45. Peltz CD, Dourte LM, Kuntz AF, et al. The effect of postoperative passive motion on rotator cuff healing in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2421-2429.

46. Vopat BG, Lee BJ, DeStefano S, et al. Risk factors for infection after rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:428-434.

47. Pauzenberger L, Grieb A, Hexel M, et al. Infections following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: incidence, risk factors, and prophylaxis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:595-601.

48. Randelli P, Spennacchio P, Ragone V, et al. Complications associated with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a literature review. Musculoskelet Surg. 2012;96:9-16.

49. Hoxie SC, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Pulmonary embolism following rotator cuff repair. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2008;2:49-51.

50. Wu XL, Briggs L, Murrell GAC. Intraoperative determinants of rotator cuff repair integrity: an analysis of 500 consecutive repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2771-2776.

51. McElvany MD, McGoldrick E, Gee AO, et al. Rotator cuff repair: published evidence on factors associated with repair integrity and clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:491-500.

52. Yoo JH, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of postoperative repair integrity on health-related quality of life after rotator cuff repair: healed versus retear group. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41;2637-2644.

53. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, et al. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:880-890.

54. Cho NS, Cha SW, Rhee YG. Alterations of the deltoid muscle after open versus arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2927-2934.

Rotator cuff disease accounts for as many as 65% of shoulder-related visits to physicians’ offices,1 yet the natural course of rotator cuff tears is still not well understood.2 Treatment options are controversial because both conservative and surgical management have been successful. Physical therapy is a durable and reliable treatment option, but there are concerns about long-term progression of the tear.3 Surgical arthroscopic techniques, which result in less morbidity than open surgery, have improved overall surgical care; as such, the rate of rotator cuff procedures has increased significantly.4

Our goal in this article is to provide clinical guidance to the primary care provider. We review management options for rotator cuff injury; summarize considerations for proceeding with conservative or surgical management; and discuss surgical risks and complications.

Conservative management: Who is most likely to benefit?

The choice of treatment for rotator cuff injury depends on a host of variables, including shoulder dominance, duration of symptoms, type of tear (partial or full), age, demands (activity level, occupation, sport), and comorbidities (diabetes, tobacco use). Treatment goals include resolution of pain, normalized range of motion and strength, and restored arm and shoulder function.5

Initial nonoperative management is indicated in patients who

- have a partial-thickness tear (a notable exception is young patients with traumatic injury),6

- have lower functional demands and moderate symptoms, or

- refuse surgery.7

Patients who respond to nonoperative management will, typically, do so within 6 to 12 weeks.5,8

Few randomized, controlled trials have compared conservative and surgical management of rotator cuff tears; furthermore, the findings of these studies have been mixed. Nonoperative management has been shown to be the favored initial treatment for isolated, symptomatic, nontraumatic, supraspinatus tears in older patients.9 In a recent study,10 5-year outcomes were examined in a prospective cohort enrolled in a rotator cuff treatment program: Approximately 75% of patients remained successfully treated with nonoperative management, and clinical outcomes of the operative and nonoperative groups were not significantly different at 5-year follow-up. Investigators concluded that nonoperative treatment is effective for many patients who have a chronic, full-thickness rotator cuff tear.

In a study investigating the treatment of degenerative rotator cuff tear, patients were randomly treated using an operative or nonoperative protocol. No differences in functional outcomes were observed at 1 year after treatment; however, surgical treatment significantly improved subjective parameters of pain and disability.11 A similar study suggested statistically significant improvement in outcomes for patients managed operatively, compared with those treated nonoperatively, but differences in shoulder outcome and the visual analog pain score were small and failed to meet thresholds considered clinically significant. Larger studies, with longer follow-up, are required to determine whether clinical differences between these types of treatment become more evident over time.12

Continue to: A look at nonoperative options and outcomes

A look at nonoperative options and outcomes

Surveillance. Rotator cuff disease of the supraspinatus tendon often results from a degenerative process that progresses to partial and, eventually, full-thickness tearing.8 Once a tear develops, progression is difficult to predict. Many rotator cuff tears grow larger over time; this progression is commonly associated with new or increased pain and weakness, or both. Although asymptomatic progression of a tear is uncommon, many patients—and physicians—are apprehensive about proceeding with nonoperative treatment for a full-thickness tear.8

To diminish such fears, surveillance can include regular assessment of shoulder motion and strength, with consideration of repeat imaging until surgery is performed or the patient is no longer a surgical candidate or interested in surgical treatment.7 Patients and providers need to remain vigilant because tears that are initially graded as repairable can become irreparable if the tendon retracts or there is fatty infiltration of the muscle belly. Results of secondary surgical repair following failed prolonged nonoperative treatment tend to be inferior to results seen in patients who undergo primary tendon repair.7

Analgesics. Simple analgesics, such as acetaminophen, are a low-risk first-line option for pain relief; however, there are limited data on the efficacy of acetaminophen in rotator cuff disease. A topical or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), or both, can be considered, but potential contraindications, such as gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular risks, should be monitored.13 Avoid opioids, given the potential for abuse, except during the immediate postoperative period.5

Glucocorticoid injection. Injection of a glucocorticoid drug into the subacromial space should be considered in patients whose pain interferes with sleep, limits activities of daily living, or hinders the ability to participate in physical therapy.5 A recent systematic review demonstrated that NSAIDs and glucocorticoids brought similar pain relief and active abduction at 4 to 6 weeks, but that glucocorticoids were significantly better at achieving remission of symptoms.14 There are no data comparing glucocorticoid preparations (ie, different glucocorticoids or anesthetics, dosages, volumes), and ultrasound guidance does not appear to be necessary for short-term pain relief.15 Note: Repeated injection has been shown to decrease the durability of surgically repaired tendons16; if a patient is a candidate for surgery, repeat injections should be carefully considered—and avoided if possible.

Physical therapy. The goals of physical therapy are activity modification, stretching the shoulder capsule, and strengthening the surrounding musculature (periscapular, rotator cuff, and deltoid). Patients advance through 3 phases of recovery: shoulder mobility, strengthening, and function (ie, joint reactivation to improve shoulder proprioception and coordination).

Continue to: A recent meta-analysis...

A recent meta-analysis17 found comparative evidence on treating rotator cuff tears with physical therapy to be inconclusive. At 1-year follow-up, there was no clinically significant difference between surgery and active physical therapy in either improving the Constant Shoulder Score (an assessment of function) or reducing pain caused by a rotator cuff tear. Therefore, the authors proposed, given the low risk of harm, a conservative approach should be the initial treatment modality for a tear.

A Cochrane review18 examined 60 eligible trials, in which the mean age of patients was 51 years and the mean duration of symptoms, 11 months. Overall, the review concluded that the effects of manual therapy and exercise might be similar to those of glucocorticoid injection and arthroscopic subacromial decompression. The authors noted that this conclusion is based on low-quality evidence, with only 1 study in the review that compared the combination of manual therapy and exercise to placebo.

Other conservative options. Ultrasound, topical nitroglycerin, topical lidocaine, glucocorticoid iontophoresis, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, massage, acupuncture, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, hyaluronic acid, and platelet-rich plasma have been used to treat rotator cuff disease. These modalities require further study, however, to determine their effectiveness for this indication.7,19

Who is a candidate for surgical management?

Although nonoperative treatment is preferred for rotator cuff tendinitis or tendinosis and partial-thickness tears, appropriate management of full-thickness tears is debatable.20 Some surgeons advocate early operative intervention of repairable full-thickness tears to prevent further progression and reduce the risk of long-term dysfunction.

The decision to pursue operative repair depends on

- patient characteristics (age, activity level, comorbidities),

- patient function (amount of disability caused by the tear),

- characteristics of the tear (length, depth, retraction), and

- chronicity of the tear (acuity).

Continue to: TABLE 1...

TABLE 121,22 highlights variables that influence the decision to proceed, or not to proceed, with operative intervention. Because enlargement of a tear usually exacerbates symptoms,23 patients with a tear who are successfully managed nonoperatively should be counseled on the potential of the tear to progress.

What are the surgical options?

Little clinical evidence favors one exposure technique over another. This equivalency has been demonstrated by a systematic review of randomized controlled trials comparing arthroscopic and mini-open rotator cuff repair, which showed no difference in function, pain, or range of motion.24 That conclusion notwithstanding, arthroscopic repair is increasingly popular because it results in less pain, initially, and faster return to work.20

There is controversy among surgeons regarding the choice of fixation technique: Tendons can be secured using 1 or 2 rows of anchors (FIGURE). Advocates of single-row repair cite shorter surgical time, decreased cost, and equivalent outcomes; surgeons who favor double-row, or so-called transosseous-equivalent, repair claim that it provides better restoration of normal anatomy and biomechanical superiority.25,26

Regardless of technique, most patients are immobilized for 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively.27 Physical therapy usually commences within the first week or 2 postop, limited to passive motion for 6 to 12 weeks. Active motion and strengthening of rotator-cuff muscles often is initiated by 3 months postop, although this phase is sometimes delayed because of concern over slow tendon healing. Typically, patients make a full return to sports and manual work at 6 months postop. Patients experience most symptomatic improvement during the first 6 months following surgery, although functional gains can be realized for as long as 2 years after surgery.28

Most torn rotator cuffs can be fixed back to the greater tuberosity, but some chronic, massive, retracted tears lack the mobility to be repaired, or re-tear shortly after repair. Over time, the humeral head in a rotator cuff–deficient shoulder can migrate superiorly to abut the undersurface of the acromion, which can lead to significant glenohumeral osteoarthritis. To prevent or remedy elevation of the humeral head, salvage procedures—debridement, partial repair, spanning graft, tendon transfer, superior capsule reconstruction, balloon arthroplasty, reverse total shoulder replacement—can be used to alleviate pain and restore function. These procedures have significant limitations, however, and usually provide less favorable outcomes than standard repair.29-35

Continue to: Surgical outcomes

Surgical outcomes

Pain, function, and patient satisfaction outcomes following rotator cuff repair are generally favorable: 90% of patients are “happy” 6 months postop.28 Younger populations often have traumatic rotator cuff tears; they generally are interested in returning to sporting activities following their injury. Nearly 85% of younger patients who undergo rotator cuff repair return to sports, and 65.9% return to an equivalent level of play.36

Variables associated with an unfavorable outcome include increasing age, smoking, increased size of the tear, poor tendon quality, hyperlipidemia, workers’ compensation status, fatty infiltration of muscle, obesity, diabetes, and additional procedures to the biceps tendon and acromioclavicular joint performed at the time of rotator cuff repair.37-39 Interestingly, a study concluded that, if a patient expects a good surgical outcome, they are more likely to go on to report a favorable outcome—suggesting that a patient’s expectations might influence their actual outcome.40

Risks and complications

Although rotator cuff surgery has much lower morbidity than other orthopedic surgeries, it is not without risk of complications. If re-tears are excluded, postop complications have been reported in approximately 10% of patients.41 Common complications and their anticipated rate of occurrence are listed in TABLE 2.42-49

Re-tear of the surgically repaired tendon is the most common postop complication. Published re-tear rates range from 20% to 96%42,43 and generally correlate with initial tear size: A small tear is twice as likely to heal as a massive tear.50 That large range—a span of 76%—results from using a variety of methods to measure re-tear and might not have clinical meaning. A meta-analysis that examined more than 8000 shoulder surgeries reported an overall re-tear rate of 26.6%; however, both patients whose tendons healed and those who re-tore demonstrated clinical improvement.51 In a separate study, patients reported improvement in pain, function, range of motion, and satisfaction regardless of the integrity of the tendon; however, significant improvement in strength was seen only in those whose repair had healed.52

Postop stiffness is more common with arthroscopic repair than with open surgery, and with smaller rather than larger tears.53 Patient variables associated with an increased risk of postop adhesive capsulitis include workers’ compensation insurance, age < 50 years, and preoperative calcific tendonitis or adhesive capsulitis.53 Stiffness generally responds to physical therapy and rarely requires surgical lysis of adhesions or capsular release.

Continue to: Significant injury...

Significant injury to the deltoid muscle has become increasingly uncommon with the advancement of arthroscopic surgery. In traditional open surgery, detachment of the deltoid (and subsequent repair) is required to improve visualization; however, doing so can lead to atrophy and muscle rupture and dehiscence. Deltoid damage occurs in ≤ 60% of open surgeries but is negligible in arthroscopic and mini-open repairs, which involve splitting deltoid fibers to gain exposure of the underlying rotator cuff.54

SIDEBAR

Key takeaways in the management of rotator cuff injury

- Chronic, nontraumatic, and partial-thickness tears respond well to conservative management as first-line treatment. Poor surgical candidates should also be offered a trial of conservative therapy.

- Consider referral for surgical consultation if the patient does not respond to conservative therapy in 6 to 12 weeks; also, patients who have a full-thickness tear and young patients with traumatic injury should be referred for surgical consultation.

- Arthroscopy has become the preferred approach to rotator cuff repair because it is associated with less pain, fewer complications, and faster recovery.

- Patients should be counseled that recovery from surgical repair of a torn rotator cuff takes, on average, 6 months. Some massive or retracted rotator cuff injuries require more extensive procedures that increase healing time.

- Overall, patients are “happy” with rotator cuff repair at 6 months; clinical complications are uncommon, making surgery a suitable option in appropriately selected patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Cayce Onks, DO, MS, ATC, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine, Family and Community Medicine H154, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-0850; [email protected].

Rotator cuff disease accounts for as many as 65% of shoulder-related visits to physicians’ offices,1 yet the natural course of rotator cuff tears is still not well understood.2 Treatment options are controversial because both conservative and surgical management have been successful. Physical therapy is a durable and reliable treatment option, but there are concerns about long-term progression of the tear.3 Surgical arthroscopic techniques, which result in less morbidity than open surgery, have improved overall surgical care; as such, the rate of rotator cuff procedures has increased significantly.4

Our goal in this article is to provide clinical guidance to the primary care provider. We review management options for rotator cuff injury; summarize considerations for proceeding with conservative or surgical management; and discuss surgical risks and complications.

Conservative management: Who is most likely to benefit?

The choice of treatment for rotator cuff injury depends on a host of variables, including shoulder dominance, duration of symptoms, type of tear (partial or full), age, demands (activity level, occupation, sport), and comorbidities (diabetes, tobacco use). Treatment goals include resolution of pain, normalized range of motion and strength, and restored arm and shoulder function.5

Initial nonoperative management is indicated in patients who

- have a partial-thickness tear (a notable exception is young patients with traumatic injury),6

- have lower functional demands and moderate symptoms, or

- refuse surgery.7

Patients who respond to nonoperative management will, typically, do so within 6 to 12 weeks.5,8

Few randomized, controlled trials have compared conservative and surgical management of rotator cuff tears; furthermore, the findings of these studies have been mixed. Nonoperative management has been shown to be the favored initial treatment for isolated, symptomatic, nontraumatic, supraspinatus tears in older patients.9 In a recent study,10 5-year outcomes were examined in a prospective cohort enrolled in a rotator cuff treatment program: Approximately 75% of patients remained successfully treated with nonoperative management, and clinical outcomes of the operative and nonoperative groups were not significantly different at 5-year follow-up. Investigators concluded that nonoperative treatment is effective for many patients who have a chronic, full-thickness rotator cuff tear.

In a study investigating the treatment of degenerative rotator cuff tear, patients were randomly treated using an operative or nonoperative protocol. No differences in functional outcomes were observed at 1 year after treatment; however, surgical treatment significantly improved subjective parameters of pain and disability.11 A similar study suggested statistically significant improvement in outcomes for patients managed operatively, compared with those treated nonoperatively, but differences in shoulder outcome and the visual analog pain score were small and failed to meet thresholds considered clinically significant. Larger studies, with longer follow-up, are required to determine whether clinical differences between these types of treatment become more evident over time.12

Continue to: A look at nonoperative options and outcomes

A look at nonoperative options and outcomes

Surveillance. Rotator cuff disease of the supraspinatus tendon often results from a degenerative process that progresses to partial and, eventually, full-thickness tearing.8 Once a tear develops, progression is difficult to predict. Many rotator cuff tears grow larger over time; this progression is commonly associated with new or increased pain and weakness, or both. Although asymptomatic progression of a tear is uncommon, many patients—and physicians—are apprehensive about proceeding with nonoperative treatment for a full-thickness tear.8

To diminish such fears, surveillance can include regular assessment of shoulder motion and strength, with consideration of repeat imaging until surgery is performed or the patient is no longer a surgical candidate or interested in surgical treatment.7 Patients and providers need to remain vigilant because tears that are initially graded as repairable can become irreparable if the tendon retracts or there is fatty infiltration of the muscle belly. Results of secondary surgical repair following failed prolonged nonoperative treatment tend to be inferior to results seen in patients who undergo primary tendon repair.7

Analgesics. Simple analgesics, such as acetaminophen, are a low-risk first-line option for pain relief; however, there are limited data on the efficacy of acetaminophen in rotator cuff disease. A topical or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), or both, can be considered, but potential contraindications, such as gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular risks, should be monitored.13 Avoid opioids, given the potential for abuse, except during the immediate postoperative period.5

Glucocorticoid injection. Injection of a glucocorticoid drug into the subacromial space should be considered in patients whose pain interferes with sleep, limits activities of daily living, or hinders the ability to participate in physical therapy.5 A recent systematic review demonstrated that NSAIDs and glucocorticoids brought similar pain relief and active abduction at 4 to 6 weeks, but that glucocorticoids were significantly better at achieving remission of symptoms.14 There are no data comparing glucocorticoid preparations (ie, different glucocorticoids or anesthetics, dosages, volumes), and ultrasound guidance does not appear to be necessary for short-term pain relief.15 Note: Repeated injection has been shown to decrease the durability of surgically repaired tendons16; if a patient is a candidate for surgery, repeat injections should be carefully considered—and avoided if possible.

Physical therapy. The goals of physical therapy are activity modification, stretching the shoulder capsule, and strengthening the surrounding musculature (periscapular, rotator cuff, and deltoid). Patients advance through 3 phases of recovery: shoulder mobility, strengthening, and function (ie, joint reactivation to improve shoulder proprioception and coordination).

Continue to: A recent meta-analysis...

A recent meta-analysis17 found comparative evidence on treating rotator cuff tears with physical therapy to be inconclusive. At 1-year follow-up, there was no clinically significant difference between surgery and active physical therapy in either improving the Constant Shoulder Score (an assessment of function) or reducing pain caused by a rotator cuff tear. Therefore, the authors proposed, given the low risk of harm, a conservative approach should be the initial treatment modality for a tear.

A Cochrane review18 examined 60 eligible trials, in which the mean age of patients was 51 years and the mean duration of symptoms, 11 months. Overall, the review concluded that the effects of manual therapy and exercise might be similar to those of glucocorticoid injection and arthroscopic subacromial decompression. The authors noted that this conclusion is based on low-quality evidence, with only 1 study in the review that compared the combination of manual therapy and exercise to placebo.

Other conservative options. Ultrasound, topical nitroglycerin, topical lidocaine, glucocorticoid iontophoresis, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, massage, acupuncture, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, hyaluronic acid, and platelet-rich plasma have been used to treat rotator cuff disease. These modalities require further study, however, to determine their effectiveness for this indication.7,19

Who is a candidate for surgical management?

Although nonoperative treatment is preferred for rotator cuff tendinitis or tendinosis and partial-thickness tears, appropriate management of full-thickness tears is debatable.20 Some surgeons advocate early operative intervention of repairable full-thickness tears to prevent further progression and reduce the risk of long-term dysfunction.

The decision to pursue operative repair depends on

- patient characteristics (age, activity level, comorbidities),

- patient function (amount of disability caused by the tear),

- characteristics of the tear (length, depth, retraction), and

- chronicity of the tear (acuity).

Continue to: TABLE 1...

TABLE 121,22 highlights variables that influence the decision to proceed, or not to proceed, with operative intervention. Because enlargement of a tear usually exacerbates symptoms,23 patients with a tear who are successfully managed nonoperatively should be counseled on the potential of the tear to progress.

What are the surgical options?

Little clinical evidence favors one exposure technique over another. This equivalency has been demonstrated by a systematic review of randomized controlled trials comparing arthroscopic and mini-open rotator cuff repair, which showed no difference in function, pain, or range of motion.24 That conclusion notwithstanding, arthroscopic repair is increasingly popular because it results in less pain, initially, and faster return to work.20

There is controversy among surgeons regarding the choice of fixation technique: Tendons can be secured using 1 or 2 rows of anchors (FIGURE). Advocates of single-row repair cite shorter surgical time, decreased cost, and equivalent outcomes; surgeons who favor double-row, or so-called transosseous-equivalent, repair claim that it provides better restoration of normal anatomy and biomechanical superiority.25,26

Regardless of technique, most patients are immobilized for 4 to 6 weeks postoperatively.27 Physical therapy usually commences within the first week or 2 postop, limited to passive motion for 6 to 12 weeks. Active motion and strengthening of rotator-cuff muscles often is initiated by 3 months postop, although this phase is sometimes delayed because of concern over slow tendon healing. Typically, patients make a full return to sports and manual work at 6 months postop. Patients experience most symptomatic improvement during the first 6 months following surgery, although functional gains can be realized for as long as 2 years after surgery.28

Most torn rotator cuffs can be fixed back to the greater tuberosity, but some chronic, massive, retracted tears lack the mobility to be repaired, or re-tear shortly after repair. Over time, the humeral head in a rotator cuff–deficient shoulder can migrate superiorly to abut the undersurface of the acromion, which can lead to significant glenohumeral osteoarthritis. To prevent or remedy elevation of the humeral head, salvage procedures—debridement, partial repair, spanning graft, tendon transfer, superior capsule reconstruction, balloon arthroplasty, reverse total shoulder replacement—can be used to alleviate pain and restore function. These procedures have significant limitations, however, and usually provide less favorable outcomes than standard repair.29-35

Continue to: Surgical outcomes

Surgical outcomes

Pain, function, and patient satisfaction outcomes following rotator cuff repair are generally favorable: 90% of patients are “happy” 6 months postop.28 Younger populations often have traumatic rotator cuff tears; they generally are interested in returning to sporting activities following their injury. Nearly 85% of younger patients who undergo rotator cuff repair return to sports, and 65.9% return to an equivalent level of play.36

Variables associated with an unfavorable outcome include increasing age, smoking, increased size of the tear, poor tendon quality, hyperlipidemia, workers’ compensation status, fatty infiltration of muscle, obesity, diabetes, and additional procedures to the biceps tendon and acromioclavicular joint performed at the time of rotator cuff repair.37-39 Interestingly, a study concluded that, if a patient expects a good surgical outcome, they are more likely to go on to report a favorable outcome—suggesting that a patient’s expectations might influence their actual outcome.40

Risks and complications

Although rotator cuff surgery has much lower morbidity than other orthopedic surgeries, it is not without risk of complications. If re-tears are excluded, postop complications have been reported in approximately 10% of patients.41 Common complications and their anticipated rate of occurrence are listed in TABLE 2.42-49

Re-tear of the surgically repaired tendon is the most common postop complication. Published re-tear rates range from 20% to 96%42,43 and generally correlate with initial tear size: A small tear is twice as likely to heal as a massive tear.50 That large range—a span of 76%—results from using a variety of methods to measure re-tear and might not have clinical meaning. A meta-analysis that examined more than 8000 shoulder surgeries reported an overall re-tear rate of 26.6%; however, both patients whose tendons healed and those who re-tore demonstrated clinical improvement.51 In a separate study, patients reported improvement in pain, function, range of motion, and satisfaction regardless of the integrity of the tendon; however, significant improvement in strength was seen only in those whose repair had healed.52

Postop stiffness is more common with arthroscopic repair than with open surgery, and with smaller rather than larger tears.53 Patient variables associated with an increased risk of postop adhesive capsulitis include workers’ compensation insurance, age < 50 years, and preoperative calcific tendonitis or adhesive capsulitis.53 Stiffness generally responds to physical therapy and rarely requires surgical lysis of adhesions or capsular release.

Continue to: Significant injury...

Significant injury to the deltoid muscle has become increasingly uncommon with the advancement of arthroscopic surgery. In traditional open surgery, detachment of the deltoid (and subsequent repair) is required to improve visualization; however, doing so can lead to atrophy and muscle rupture and dehiscence. Deltoid damage occurs in ≤ 60% of open surgeries but is negligible in arthroscopic and mini-open repairs, which involve splitting deltoid fibers to gain exposure of the underlying rotator cuff.54

SIDEBAR

Key takeaways in the management of rotator cuff injury

- Chronic, nontraumatic, and partial-thickness tears respond well to conservative management as first-line treatment. Poor surgical candidates should also be offered a trial of conservative therapy.

- Consider referral for surgical consultation if the patient does not respond to conservative therapy in 6 to 12 weeks; also, patients who have a full-thickness tear and young patients with traumatic injury should be referred for surgical consultation.

- Arthroscopy has become the preferred approach to rotator cuff repair because it is associated with less pain, fewer complications, and faster recovery.

- Patients should be counseled that recovery from surgical repair of a torn rotator cuff takes, on average, 6 months. Some massive or retracted rotator cuff injuries require more extensive procedures that increase healing time.

- Overall, patients are “happy” with rotator cuff repair at 6 months; clinical complications are uncommon, making surgery a suitable option in appropriately selected patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Cayce Onks, DO, MS, ATC, Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine, Family and Community Medicine H154, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-0850; [email protected].

1. Vecchio P, Kavanagh R, Hazleman BL, et al. Shoulder pain in a community-based rheumatology clinic. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:440-442.

2. Eljabu W, Klinger HM, von Knoch M. The natural history of rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135:1055-1061.

3. Dunn WR, Kuhn JE, Sanders R, et al; MOON Shoulder Group. 2013 Neer Award: predictors of failure of nonoperative treatment of chronic, symptomatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:1303-1311.

4. Colvin AC, Egorova N, Harrison AK, et al. National trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:227-233.

5. Whittle S, Buchbinder R. In the clinic. Rotator cuff disease. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:ITC1-ITC15.

6. Lazarides AL, Alentorn-Geli E, Choi JHJ, et al. Rotator cuff tears in young patients: a different disease than rotator cuff tears in elderly patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1834-1843.

7. Petri M, Ettinger M, Brand S, et al. Non-operative management of rotator cuff tears. Open Orthop J. 2016;10:349-356.

8. Schmidt CC, Jarrett CD, Brown BT. Management of rotator cuff tears. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:399-408.

9. Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, et al. Treatment of nontraumatic rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial with two years of clinical and imaging follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1729-1737.

10. Boorman RS, More KD, Hollinshead RM, et al. What happens to patients when we do not repair their cuff tears? Five-year rotator cuff quality-of-life index outcomes following nonoperative treatment of patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:444-448.

11. Lambers Heerspink FO, van Raay JJ, Koorevaar RCT, et al. Comparing surgical repair with conservative treatment for degenerative rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1274-1281.

12. Piper CC, Hughes AJ, Ma Y, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for the management of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:572-576.

13. Boudreault J, Desmeules F, Roy J-S, et al. The efficacy of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:294-306.

14. Zheng X-Q, Li K, Wei Y-D, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus corticosteroid for treatment of shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:1824-1831.

15. Bloom JE, Rischin A, Johnston RV, et al. Image-guided versus blind glucocorticoid injection for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(8):CD009147.

16. Wiggins ME, Fadale PD, Ehrlich MG, et al. Effects of local injection of corticosteroids on the healing of ligaments. A follow-up report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1682-1691.

17. Ryösä A, Laimi K, Äärimaa V, et al. Surgery or conservative treatment for rotator cuff tear: a meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:1357-1363.

18. Page MJ, Green S, McBain B, et al. Manual therapy and exercise for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD012224.

19. Page MJ, Green S, Mrocki MA, et al. Electrotherapy modalities for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD012225.

20. Acevedo DC, Paxton ES, Williams GR, et al. A survey of expert opinion regarding rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e123.

21. Pedowitz RA, Yamaguchi K, Ahmad CS, et al. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline on: optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:163-167.

22. Thorpe A, Hurworth M, O’Sullivan P, et al. Rotator cuff disease: opinion regarding surgical criteria and likely outcome. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:291-295.

23. Mall NA, Kim HM, Keener JD, et al. Symptomatic progression of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective study of clinical and sonographic variables. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2623-2633.

24. Ji X, Bi C, Wang F, et al. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: an up-to-date meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:118-124.

25. Duquin TR, Buyea C, Bisson LJ. Which method of rotator cuff repair leads to the highest rate of structural healing? A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:835-841.

26. Choi S, Kim MK, Kim GM, et al. Factors associated with clinical and structural outcomes after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with a suture bridge technique in medium, large, and massive tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1675-1681.

27. Shen C, Tang Z-H, Hu J-Z, et al. Does immobilization after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair increase tendon healing? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134:1279-1285.

28. Gulotta LV, Nho SJ, Dodson CC, et al; . Prospective evaluation of arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs at 5 years: part I. Functional outcomes and radiographic healing rates. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:934-940.

29. Liem D, Lengers N, Dedy N, et al. Arthroscopic debridement of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:743-748.

30. Weber SC. Partial rotator cuff repair in massive rotator cuff tears: long-term follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:e171.

31. Lewington MR, Ferguson DP, Smith TD, et al. Graft utilization in the bridging reconstruction of irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:3149-3157.

32. Longo UG, Franceschetti E, Petrillo S, et al. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19:428-437.

33. Noyes MP, Denard PJ. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction: indications and outcomes. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2018;26:29-34.

34. Piekaar RSM, Bouman ICE, van Kampen PM, et al. Early promising outcome following arthroscopic implantation of the subacromial balloon spacer for treating massive rotator cuff tear. Musculoskeletal Surg. 2018;102:247-255.

35. Ek ETH, Neukom L, Catanzaro S, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears in patients younger than 65 years old: results after five to fifteen years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:1199-1208.

36. Klouche S, Lefevre N, Herman S, et al. Return to sport after rotator cuff tear repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:1877-1887.

37. Garcia GH, Liu JN, Wong A, et al. Hyperlipidemia increases the risk of retear after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:2086-2090.

38. Khair MM, Lehman J, Tsouris N, et al. A systematic review of preoperative fatty infiltration and rotator cuff outcomes. HSS J. 2016;12:170-176.

39. Lambers Heerspink FO, Dorrestijn O, van Raay JJAM, et al. Specific patient-related prognostic factors for rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1073-1080.

40. Henn RF 3rd, Kang L, Tashjian RZ, et al. Patients’ preoperative expectations predict the outcome of rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1913-1919.

41. Mansat P, Cofield RH, Kersten TE, et al. Complications of rotator cuff repair. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28:205-213.

42. Boileau P, Brassart N, Watkinson DJ, et al. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the supraspinatus: does the tendon really heal? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1229-1240.

43. Galatz LM, Ball CM, Teefey SA, et al. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:219-224.

44. Aydin N, Kocaoglu B, Guven O. Single-row versus double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in small- to medium-sized tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:722-725.

45. Peltz CD, Dourte LM, Kuntz AF, et al. The effect of postoperative passive motion on rotator cuff healing in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2421-2429.

46. Vopat BG, Lee BJ, DeStefano S, et al. Risk factors for infection after rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:428-434.

47. Pauzenberger L, Grieb A, Hexel M, et al. Infections following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: incidence, risk factors, and prophylaxis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:595-601.

48. Randelli P, Spennacchio P, Ragone V, et al. Complications associated with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a literature review. Musculoskelet Surg. 2012;96:9-16.

49. Hoxie SC, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Pulmonary embolism following rotator cuff repair. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2008;2:49-51.

50. Wu XL, Briggs L, Murrell GAC. Intraoperative determinants of rotator cuff repair integrity: an analysis of 500 consecutive repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2771-2776.

51. McElvany MD, McGoldrick E, Gee AO, et al. Rotator cuff repair: published evidence on factors associated with repair integrity and clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:491-500.

52. Yoo JH, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of postoperative repair integrity on health-related quality of life after rotator cuff repair: healed versus retear group. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41;2637-2644.

53. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, et al. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:880-890.

54. Cho NS, Cha SW, Rhee YG. Alterations of the deltoid muscle after open versus arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2927-2934.

1. Vecchio P, Kavanagh R, Hazleman BL, et al. Shoulder pain in a community-based rheumatology clinic. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34:440-442.

2. Eljabu W, Klinger HM, von Knoch M. The natural history of rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2015;135:1055-1061.

3. Dunn WR, Kuhn JE, Sanders R, et al; MOON Shoulder Group. 2013 Neer Award: predictors of failure of nonoperative treatment of chronic, symptomatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:1303-1311.

4. Colvin AC, Egorova N, Harrison AK, et al. National trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:227-233.

5. Whittle S, Buchbinder R. In the clinic. Rotator cuff disease. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:ITC1-ITC15.

6. Lazarides AL, Alentorn-Geli E, Choi JHJ, et al. Rotator cuff tears in young patients: a different disease than rotator cuff tears in elderly patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1834-1843.

7. Petri M, Ettinger M, Brand S, et al. Non-operative management of rotator cuff tears. Open Orthop J. 2016;10:349-356.

8. Schmidt CC, Jarrett CD, Brown BT. Management of rotator cuff tears. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40:399-408.

9. Kukkonen J, Joukainen A, Lehtinen J, et al. Treatment of nontraumatic rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial with two years of clinical and imaging follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:1729-1737.

10. Boorman RS, More KD, Hollinshead RM, et al. What happens to patients when we do not repair their cuff tears? Five-year rotator cuff quality-of-life index outcomes following nonoperative treatment of patients with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:444-448.

11. Lambers Heerspink FO, van Raay JJ, Koorevaar RCT, et al. Comparing surgical repair with conservative treatment for degenerative rotator cuff tears: a randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:1274-1281.

12. Piper CC, Hughes AJ, Ma Y, et al. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for the management of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:572-576.

13. Boudreault J, Desmeules F, Roy J-S, et al. The efficacy of oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:294-306.

14. Zheng X-Q, Li K, Wei Y-D, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs versus corticosteroid for treatment of shoulder pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95:1824-1831.

15. Bloom JE, Rischin A, Johnston RV, et al. Image-guided versus blind glucocorticoid injection for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(8):CD009147.

16. Wiggins ME, Fadale PD, Ehrlich MG, et al. Effects of local injection of corticosteroids on the healing of ligaments. A follow-up report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1682-1691.

17. Ryösä A, Laimi K, Äärimaa V, et al. Surgery or conservative treatment for rotator cuff tear: a meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39:1357-1363.

18. Page MJ, Green S, McBain B, et al. Manual therapy and exercise for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD012224.

19. Page MJ, Green S, Mrocki MA, et al. Electrotherapy modalities for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD012225.

20. Acevedo DC, Paxton ES, Williams GR, et al. A survey of expert opinion regarding rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96:e123.

21. Pedowitz RA, Yamaguchi K, Ahmad CS, et al. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons Clinical Practice Guideline on: optimizing the management of rotator cuff problems. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:163-167.

22. Thorpe A, Hurworth M, O’Sullivan P, et al. Rotator cuff disease: opinion regarding surgical criteria and likely outcome. ANZ J Surg. 2017;87:291-295.

23. Mall NA, Kim HM, Keener JD, et al. Symptomatic progression of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a prospective study of clinical and sonographic variables. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:2623-2633.

24. Ji X, Bi C, Wang F, et al. Arthroscopic versus mini-open rotator cuff repair: an up-to-date meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2015;31:118-124.

25. Duquin TR, Buyea C, Bisson LJ. Which method of rotator cuff repair leads to the highest rate of structural healing? A systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38:835-841.

26. Choi S, Kim MK, Kim GM, et al. Factors associated with clinical and structural outcomes after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with a suture bridge technique in medium, large, and massive tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1675-1681.

27. Shen C, Tang Z-H, Hu J-Z, et al. Does immobilization after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair increase tendon healing? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2014;134:1279-1285.

28. Gulotta LV, Nho SJ, Dodson CC, et al; . Prospective evaluation of arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs at 5 years: part I. Functional outcomes and radiographic healing rates. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:934-940.

29. Liem D, Lengers N, Dedy N, et al. Arthroscopic debridement of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:743-748.

30. Weber SC. Partial rotator cuff repair in massive rotator cuff tears: long-term follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:e171.

31. Lewington MR, Ferguson DP, Smith TD, et al. Graft utilization in the bridging reconstruction of irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Am J Sports Med. 2017;45:3149-3157.

32. Longo UG, Franceschetti E, Petrillo S, et al. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: a systematic review. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2011;19:428-437.

33. Noyes MP, Denard PJ. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction: indications and outcomes. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2018;26:29-34.

34. Piekaar RSM, Bouman ICE, van Kampen PM, et al. Early promising outcome following arthroscopic implantation of the subacromial balloon spacer for treating massive rotator cuff tear. Musculoskeletal Surg. 2018;102:247-255.

35. Ek ETH, Neukom L, Catanzaro S, et al. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty for massive irreparable rotator cuff tears in patients younger than 65 years old: results after five to fifteen years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:1199-1208.

36. Klouche S, Lefevre N, Herman S, et al. Return to sport after rotator cuff tear repair: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:1877-1887.

37. Garcia GH, Liu JN, Wong A, et al. Hyperlipidemia increases the risk of retear after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26:2086-2090.

38. Khair MM, Lehman J, Tsouris N, et al. A systematic review of preoperative fatty infiltration and rotator cuff outcomes. HSS J. 2016;12:170-176.

39. Lambers Heerspink FO, Dorrestijn O, van Raay JJAM, et al. Specific patient-related prognostic factors for rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23:1073-1080.

40. Henn RF 3rd, Kang L, Tashjian RZ, et al. Patients’ preoperative expectations predict the outcome of rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1913-1919.

41. Mansat P, Cofield RH, Kersten TE, et al. Complications of rotator cuff repair. Orthop Clin North Am. 1997;28:205-213.

42. Boileau P, Brassart N, Watkinson DJ, et al. Arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the supraspinatus: does the tendon really heal? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1229-1240.

43. Galatz LM, Ball CM, Teefey SA, et al. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:219-224.

44. Aydin N, Kocaoglu B, Guven O. Single-row versus double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in small- to medium-sized tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:722-725.

45. Peltz CD, Dourte LM, Kuntz AF, et al. The effect of postoperative passive motion on rotator cuff healing in a rat model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2421-2429.

46. Vopat BG, Lee BJ, DeStefano S, et al. Risk factors for infection after rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2016;32:428-434.

47. Pauzenberger L, Grieb A, Hexel M, et al. Infections following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: incidence, risk factors, and prophylaxis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:595-601.

48. Randelli P, Spennacchio P, Ragone V, et al. Complications associated with arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a literature review. Musculoskelet Surg. 2012;96:9-16.

49. Hoxie SC, Sperling JW, Cofield RH. Pulmonary embolism following rotator cuff repair. Int J Shoulder Surg. 2008;2:49-51.

50. Wu XL, Briggs L, Murrell GAC. Intraoperative determinants of rotator cuff repair integrity: an analysis of 500 consecutive repairs. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2771-2776.

51. McElvany MD, McGoldrick E, Gee AO, et al. Rotator cuff repair: published evidence on factors associated with repair integrity and clinical outcome. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:491-500.

52. Yoo JH, Cho NS, Rhee YG. Effect of postoperative repair integrity on health-related quality of life after rotator cuff repair: healed versus retear group. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41;2637-2644.

53. Huberty DP, Schoolfield JD, Brady PC, et al. Incidence and treatment of postoperative stiffness following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:880-890.

54. Cho NS, Cha SW, Rhee YG. Alterations of the deltoid muscle after open versus arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2927-2934.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Offer a trial of conservative management to patients with chronic, nontraumatic, or partial-thickness rotator cuff injury and to those who are poor surgical candidates. B

› Counsel patients that the rate of surgical complications is low and outcomes are favorable in properly selected patients for operative repair of rotator cuff tear. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series