User login

Conservative or surgical management for that shoulder dislocation?

The shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, is the most commonly dislocated large joint; dislocation occurs at a rate of 23.9 per 100,000 person/years.1,2 There are 2 types of dislocation: traumatic anterior dislocation, which accounts for roughly 90% of dislocations, and posterior dislocation (10%).3 Anterior dislocation typically occurs when the patient’s shoulder is forcefully abducted and externally rotated.

The diagnosis is made after review of the history and mechanism of injury and performance of a complete physical exam with imaging studies—the most critical component of diagnosis.4 Standard radiographs (anteroposterior, axillary, and scapular Y) can confirm the presence of a dislocation; once the diagnosis is confirmed, closed reduction of the joint should be performed.1 (Methods of reduction are beyond the scope of this article but have been recently reviewed.5)

Risk for recurrence drives management choices

Following an initial shoulder dislocation, the risk of recurrence is high.6,7 Rates vary based on age, pathology after dislocation, activity level, type of immobilization, and whether surgery was performed. Overall, age is the strongest predictor of recurrence: 72% of patients ages 12 to 22 years, 56% of those ages 23 to 29 years, and 27% of those older than 30 years experience recurrence.6 Patients who have recurrent dislocations are at risk for arthropathy, fear of instability, and worsening surgical outcomes.6

Reducing the risk of a recurrent shoulder dislocation has been the focus of intense study. Proponents of surgical stabilization argue that surgery—rather than a trial of conservative treatment—is best when you consider the high risk of recurrence in young athletes (the population primarily studied), the soft-tissue and bony damage caused by recurrent instability, and the predictable improvement in quality of life following surgery.

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, there was evidence that, for first-time traumatic shoulder dislocations, early surgery led to fewer repeat shoulder dislocations (number needed to treat [NNT] = 2-4.7). However, a significant number of patients primarily treated nonoperatively did not experience a repeat shoulder dislocation within 2 years.2

The conflicting results from randomized trials comparing operative intervention to conservative management have led surgeons and physicians in other specialties to take different approaches to the management of shoulder dislocation.2 In this review, we aim to summarize considerations for conservative vs surgical management and provide clinical guidance for primary care physicians.

When to try conservative management

Although the initial treatment after a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation has been debated, a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that at least half of first-time dislocations are successfully treated with conservative management.2 Management can include immobilization for comfort and/or physical therapy. Age will play a role, as mentioned earlier; in general, patients older than 30 have a significant decrease in recurrence rate and are good candidates for conservative therapy.6 It should be noted that much of the research with regard to management of shoulder dislocations has been done in an athletic population.

Continue to: Immobilization may benefit some

Immobilization may benefit some

Recent evidence has determined that the duration of immobilization in internal rotation does not impact recurrent instability.8,9 In patients older than 30, the rate of repeat dislocation is lower, and early mobilization after 1 week is advocated to avoid joint stiffness and minimize the risk of adhesive capsulitis.10

Arm position during immobilization remains controversial.11 In a classic study by Itoi et al, immobilization for 3 weeks in internal rotation vs 10° of external rotation was associated with a recurrence rate of 42% vs 26%, respectively.12 In this study, immobilization in 10° of external rotation was especially beneficial for patients ages 30 years or younger.12

Cadaveric and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have shown external rotation may improve the odds of labral tear healing by positioning the damaged and intact parts of the glenoid labrum in closer proximity.13 While this is theoretically plausible, a recent Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to determine whether immobilization in external rotation has any benefits beyond those offered by internal rotation.14 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that immobilization in external rotation vs internal rotation after a first-time traumatic shoulder dislocation did not change outcomes.2 With that said, most would prefer to immobilize in the internal rotation position for ease.

More research is needed. A Cochrane review highlighted the need for continued research.14 Additionally, most of the available randomized controlled trials to date have consisted of young men, with the majority of dislocations related to sports activities. Women, nonathletes, and older patients have been understudied to date; extrapolating current research to those groups of patients may not be appropriate and should be a focus for future research.2

Physical therapy: The conservative standard of care

Rehabilitation after glenohumeral joint dislocation is the current standard of care in conservative management to reduce the risk for repeat dislocation.15 Depending on the specific characteristics of the instability pattern, the approach may be adapted to the patient. A recent review focused on the following 4 key points: (1) restoration of rotator cuff strength, focusing on the eccentric capacity of the external rotators, (2) normalization of rotational range of motion with particular focus on internal range of motion, (3) optimization of the flexibility and muscle performance of the scapular muscles, and (4) increasing the functional sport-specific load on the shoulder girdle.

Continue to: A common approach to the care of...

A common approach to the care of a patient after a glenohumeral joint dislocation is to place the patient’s shoulder in a sling for comfort, with permitted pain-free isometric exercise along with passive and assisted elevation up to 100°.16 This is followed by a nonaggressive rehabilitation protocol for 2 months until full recovery, which includes progressive range of motion, strength, proprioception, and return to functional activities.16

More aggressive return-to-play protocols with accelerated timelines and functional progression have been studied, including in a multicenter observational study that followed 45 contact intercollegiate athletes prospectively after in-season anterior glenohumeral instability. Thirty-three of 45 (73%) athletes returned to sport for either all or part of the season after a median 5 days lost from competition, with 12 athletes (27%) successfully completing the season without recurrence. Athletes with a subluxation event were 5.3 times more likely to return to sport during the same season, compared with those with dislocations.17

Dynamic bracing may also allow for a safe and quicker return to sport in athletes18 but recently was shown to not impact recurrent dislocation risk.19

Return to play should be based on subjective assessment as well as objective measurements of range of motion, strength, and dynamic function.15 Patients who continue to have significant weakness and pain at 2 to 3 weeks post injury despite physical therapy should be re-evaluated with an MRI for concomitant rotator cuff tears and need for surgical referral.20

When to consider surgical intervention

In a recent meta-analysis, recurrent dislocation and instability occurred at a rate of 52.9% following nonsurgical treatment.2 The decision to perform surgical intervention is typically made following failure of conservative management. Other considerations include age, gender, bone loss, and cartilage defect.21,22 Age younger than 30 years, participation in competition, contact sports, and male gender have been associated with an increased risk of recurrence.23-25 For this reason, obtaining an MRI at time of first dislocation can help facilitate surgical decisions if the patient is at high risk for surgical need.26

Continue to: An increasing number...

An increasing number of dislocations portends a poor outcome with nonoperative treatment. Kao et al demonstrated a second dislocation leads to another dislocation in 19.6% of cases, while 44.3% of those with a third dislocation event will sustain another dislocation.24 Surgery should be considered for patients with recurrent instability events to prevent persistent instability and decrease the amount of bone loss that can occur with repetitive dislocations.

What are the surgical options?

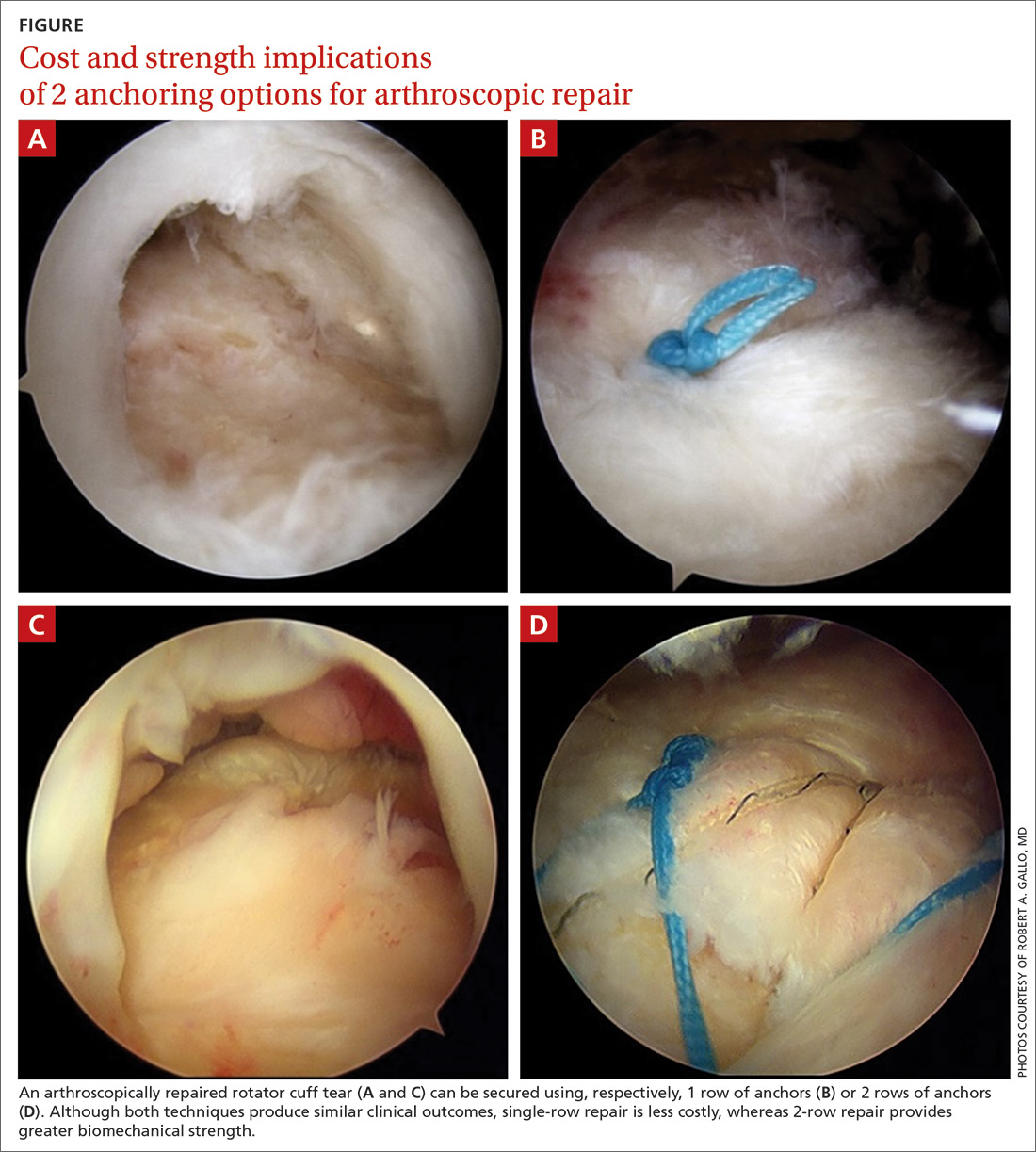

Several surgical options exist to remedy the unstable shoulder. Procedures can range from an arthroscopic repair to an open stabilization combined with structural bone graft to replace a bone defect caused by repetitive dislocations.

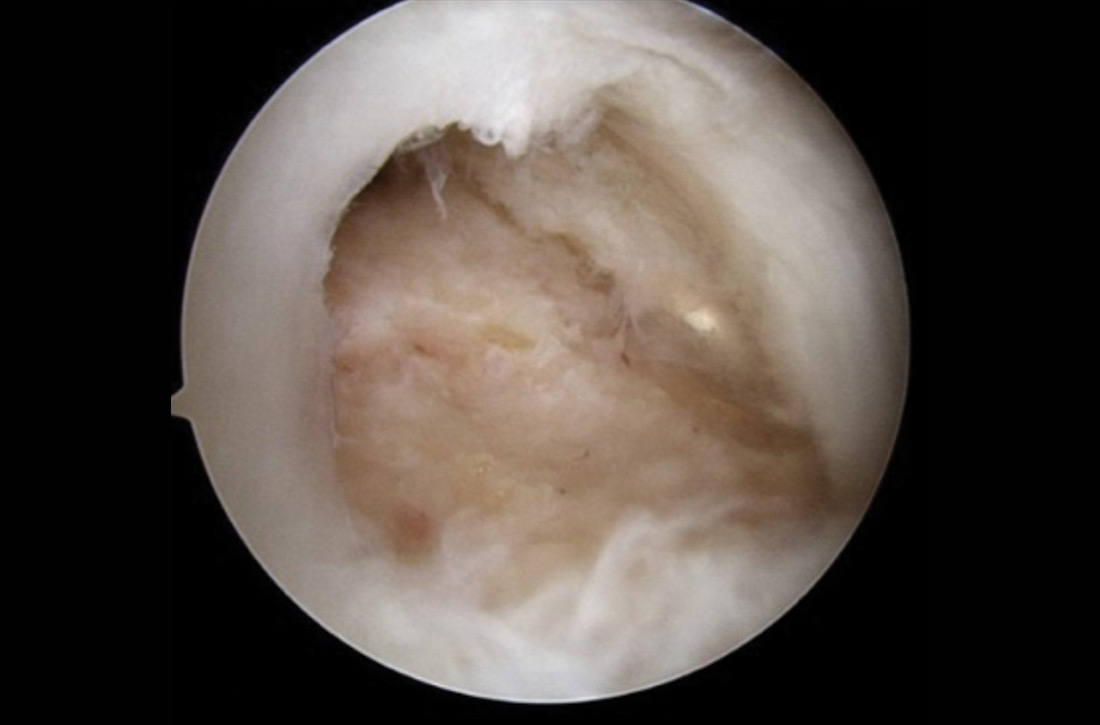

Arthroscopic techniques have become the mainstay of treatment and account for 71% of stabilization procedures performed.21 These techniques cause less pain in the early postoperative period and provide for a faster return to work.27 Arthroscopy has the additional advantage of allowing for complete visualization of the glenohumeral joint to identify and address concomitant pathology, such as intra-articular loose bodies or rotator cuff tears.

Open repair was the mainstay of treatment prior to development of arthroscopic techniques. Some surgeons still prefer this method—especially in high-risk groups—because of a lower risk of recurrent disloca-tion.28 Open techniques often involve detachment and repair of the upper subscapularis tendon and are more likely to produce long-term losses in external rotation range of motion.28

Which one is appropriate for your patient? The decision to pursue an open or arthroscopic procedure and to augment with bone graft depends on the amount of glenoid and humeral head bone loss, patient activity level, risk of recurrent dislocation, and surgeon preference.

Continue to: For the nonathletic population...

For the nonathletic population, the timing of injury is less critical and surgery is typically recommended after conservative treatment has failed. In an athletic population, the timing of injury is a necessary consideration. An injury midseason may be “rehabbed” in hopes of returning to play. Individuals with injuries occurring at the end of a season, who are unable to regain desired function, and/or with peri-articular fractures or associated full-thickness rotator cuff tears may benefit from sooner surgical intervention.21

Owens et al have described appropriate surgical indications and recommendations for an in-season athlete.21 In this particular algorithm, the authors suggest obtaining an MRI for decision making, but this is specific to in-season athletes wishing to return to play. In general, an MRI is not always indicated for patients who wish to receive conservative therapy but would be indicated for surgical considerations. The algorithm otherwise uses bone and soft-tissue injury, recurrent instability, and timing in the season to help determine management.21

Outcomes: Surgery has advantages …

Recurrence rates following surgical intervention are considerably lower than with conservative management, especially among young, active individuals. A recent systematic review by Donohue et al demonstrated recurrent instability rates following surgical intervention as low as 2.4%.29 One study comparing the outcome of arthroscopic repair vs conservative management showed that the risk of postoperative instability was reduced by 20% compared to other treatments.7 Furthermore, early surgical fixation can improve quality of life, produce better functional outcomes, decrease time away from activity, increase patient satisfaction, and slow the development of glenohumeral osteoarthritis produced from recurrent instability.2,7

Complications. Surgery does carry inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, surgical complications, and surgical failure. Recurrent instability is the most common complication following surgical shoulder stabilization. Rates of recurrent instability after surgical stabilization depend on patient age, activity level, and amount of bone loss: males younger than 18 years who participate in contact competitive sports and have significant bone loss are more likely to have recurrent dislocation after surgery.23 The type of surgical procedure selected may decrease this risk.

While the open procedures decrease risk of postoperative instability, these surgeries can pose a significant risk of complications. Major complications for specific open techniques have been reported in up to 30% of patients30 and are associated with lower levels of surgeon experience.31 While the healing of bones and ligaments is always a concern, 1 of the most feared complications following stabilization surgery is iatrogenic nerve injury. Because of the axillary nerve’s close proximity to the inferior glenoid, this nerve can be injured without meticulous care and can result in paralysis of the deltoid muscle. This injury poses a major impediment to normal shoulder function. Some procedures may cause nerve injuries in up to 10% of patients, although most injuries are transient.32

Continue to: Bottom line

Bottom line

Due to the void of evidence-based guidelines for conservative vs surgical management of primary shoulder dislocation, it would be prudent to have a risk-benefit discussion with patients regarding treatment options.

Patients older than 30 years and those with uncomplicated injuries are best suited for conservative management of primary shoulder dislocations. Immobilization is debated and may not change outcomes, but a progressive rehabilitative program after the initial acute injury is helpful. Risk factors for failing conservative management include recurrent dislocation, subsequent arthropathy, and additional concomitant bone or soft-tissue injuries.

Patients younger than 30 years who have complicated injuries with bone or cartilage loss, rotator cuff tears, or recurrent instability, and highly physically active individuals are best suited for surgical management. Shoulder arthroscopy has become the mainstay of surgical treatment for shoulder dislocations. Outcomes are favorable and dislocation recurrence is low after surgical repair. Surgery does carry its own inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, complications during surgery, and surgical failure leading to recurrent instability.

Cayce Onks, DO, MS, ATC, Penn State Hershey, Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine, Family and Community Medicine H154, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-0850; [email protected]

1. Lin K, James E, Spitzer E, et al. Pediatric and adolescent anterior shoulder instability: clinical management of first time dislocators. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30:49-56.

2. Kavaja L, Lähdeoja T, Malmivaara A, et al. Treatment after traumatic shoulder dislocation: a systematic review with a network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:1498-1506.

3. Brelin A, Dickens JF. Posterior shoulder instability. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2017;25:136-143.

4. Galvin JW, Ernat JJ, Waterman BR, et al. The epidemiology and natural history of anterior shoulder dislocation. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10:411-424.

5. Rozzi SL, Anderson JM, Doberstein ST, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: immediate management of appendicular joint dislocations. J Athl Train. 2018;53:1117-1128.

6. Hovelius L, Saeboe M. Arthropathy after primary anterior shoulder dislocation: 223 shoulders prospectively followed up for twenty-five years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:339-347.

7. Polyzois I, Dattani R, Gupta R, et al. Traumatic first time shoulder dislocation: surgery vs non-operative treatment. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2016;4:104-108.

8. Cox CL, Kuhn JE. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of acute shoulder dislocation in the athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008;7:263-268.

9. Kuhn JE. Treating the initial anterior shoulder dislocation—an evidence-based medicine approach. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2006;14:192-198.

10. Smith TO. Immobilization following traumatic anterior glenohumeral joint dislocation: a literature review. Injury. 2006;37:228-237.

11. Liavaag S, Brox JI, Pripp AH, et al. Immobilization in external rotation after primary shoulder dislocation did not reduce the risk of recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:897-904.

12. Itoi E, Hatakeyama Y, Sato T, et al. Immobilization in external rotation after shoulder dislocation reduces the risk of recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2124-2131.

13. Miller BS, Sonnabend DH, Hatrick C, et al. Should acute anterior dislocations of the shoulder be immobilized in external rotation? A cadaveric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:589-592.

14. Hanchard NCA, Goodchild LM, Kottam L. Conservative management following closed reduction of traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD004962.

15. Cools AM, Borms D, Castelein B, et al. Evidence-based rehabilitation of athletes with glenohumeral instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:382-389.

16. Lafuente JLA, Marco SM, Pequerul JMG. Controversies in the management of the first time shoulder dislocation. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:1001-1010.

17. Dickens JF, Owens BD, Cameron KL, et al. Return to play and recurrent instability after in-season anterior shoulder instability: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2842-2850.

18. Conti M, Garofalo R, Castagna A, et al. Dynamic brace is a good option to treat first anterior shoulder dislocation in season. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101(suppl 2):169-173.

19. Shanley E, Thigpen C, Brooks J, et al. Return to sport as an outcome measure for shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1062-1067.

20. Gombera MM, Sekiya JK. Rotator cuff tear and glenohumeral instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2448-2456.

21. Owens BD, Dickens JF, Kilcoyne KG, et al. Management of mid-season traumatic anterior shoulder instability in athletes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:518-526.

22. Ozturk BY, Maak TG, Fabricant P, et al. Return to sports after arthroscopic anterior stabilization in patients aged younger than 25 years. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:1922-1931.

23. Balg F, Boileau P. The instability severity index score. A simple preoperative score to select patients for arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1470-1477.

24. Kao J-T, Chang C-L, Su W-R, et al. Incidence of recurrence after shoulder dislocation: a nationwide database study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:1519-1525.

25. Porcillini G, Campi F, Pegreffi F, et al. Predisposing factors for recurrent shoulder dislocation after arthroscopic treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2537-2542.

26. Magee T. 3T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:86-92.

27. Green MR, Christensen KP. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart procedures: a comparison of early morbidity and complications. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:371-374.

28. Khatri K, Arora H, Chaudhary S, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials involving anterior shoulder instability. Open Orthop J. 2018;12:411-418.

29. Donohue MA, Owens BD, Dickens JF. Return to play following anterior shoulder dislocations and stabilization surgery. Clin Sports Med. 2016;35:545-561.

30. Griesser MJ, Harris JD, McCoy BW, et al. Complications and re-operations after Bristow-Latarjet shoulder stabilization: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:286-292.

31. Ekhtiari S, Horner NS, Bedi A, et al. The learning curve for the Latarjet procedure: a systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6:2325967118786930.

32. Shah AA, Butler RB, Romanowski J, et al. Short-term complications of the Latarjet procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:495-501.

The shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, is the most commonly dislocated large joint; dislocation occurs at a rate of 23.9 per 100,000 person/years.1,2 There are 2 types of dislocation: traumatic anterior dislocation, which accounts for roughly 90% of dislocations, and posterior dislocation (10%).3 Anterior dislocation typically occurs when the patient’s shoulder is forcefully abducted and externally rotated.

The diagnosis is made after review of the history and mechanism of injury and performance of a complete physical exam with imaging studies—the most critical component of diagnosis.4 Standard radiographs (anteroposterior, axillary, and scapular Y) can confirm the presence of a dislocation; once the diagnosis is confirmed, closed reduction of the joint should be performed.1 (Methods of reduction are beyond the scope of this article but have been recently reviewed.5)

Risk for recurrence drives management choices

Following an initial shoulder dislocation, the risk of recurrence is high.6,7 Rates vary based on age, pathology after dislocation, activity level, type of immobilization, and whether surgery was performed. Overall, age is the strongest predictor of recurrence: 72% of patients ages 12 to 22 years, 56% of those ages 23 to 29 years, and 27% of those older than 30 years experience recurrence.6 Patients who have recurrent dislocations are at risk for arthropathy, fear of instability, and worsening surgical outcomes.6

Reducing the risk of a recurrent shoulder dislocation has been the focus of intense study. Proponents of surgical stabilization argue that surgery—rather than a trial of conservative treatment—is best when you consider the high risk of recurrence in young athletes (the population primarily studied), the soft-tissue and bony damage caused by recurrent instability, and the predictable improvement in quality of life following surgery.

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, there was evidence that, for first-time traumatic shoulder dislocations, early surgery led to fewer repeat shoulder dislocations (number needed to treat [NNT] = 2-4.7). However, a significant number of patients primarily treated nonoperatively did not experience a repeat shoulder dislocation within 2 years.2

The conflicting results from randomized trials comparing operative intervention to conservative management have led surgeons and physicians in other specialties to take different approaches to the management of shoulder dislocation.2 In this review, we aim to summarize considerations for conservative vs surgical management and provide clinical guidance for primary care physicians.

When to try conservative management

Although the initial treatment after a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation has been debated, a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that at least half of first-time dislocations are successfully treated with conservative management.2 Management can include immobilization for comfort and/or physical therapy. Age will play a role, as mentioned earlier; in general, patients older than 30 have a significant decrease in recurrence rate and are good candidates for conservative therapy.6 It should be noted that much of the research with regard to management of shoulder dislocations has been done in an athletic population.

Continue to: Immobilization may benefit some

Immobilization may benefit some

Recent evidence has determined that the duration of immobilization in internal rotation does not impact recurrent instability.8,9 In patients older than 30, the rate of repeat dislocation is lower, and early mobilization after 1 week is advocated to avoid joint stiffness and minimize the risk of adhesive capsulitis.10

Arm position during immobilization remains controversial.11 In a classic study by Itoi et al, immobilization for 3 weeks in internal rotation vs 10° of external rotation was associated with a recurrence rate of 42% vs 26%, respectively.12 In this study, immobilization in 10° of external rotation was especially beneficial for patients ages 30 years or younger.12

Cadaveric and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have shown external rotation may improve the odds of labral tear healing by positioning the damaged and intact parts of the glenoid labrum in closer proximity.13 While this is theoretically plausible, a recent Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to determine whether immobilization in external rotation has any benefits beyond those offered by internal rotation.14 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that immobilization in external rotation vs internal rotation after a first-time traumatic shoulder dislocation did not change outcomes.2 With that said, most would prefer to immobilize in the internal rotation position for ease.

More research is needed. A Cochrane review highlighted the need for continued research.14 Additionally, most of the available randomized controlled trials to date have consisted of young men, with the majority of dislocations related to sports activities. Women, nonathletes, and older patients have been understudied to date; extrapolating current research to those groups of patients may not be appropriate and should be a focus for future research.2

Physical therapy: The conservative standard of care

Rehabilitation after glenohumeral joint dislocation is the current standard of care in conservative management to reduce the risk for repeat dislocation.15 Depending on the specific characteristics of the instability pattern, the approach may be adapted to the patient. A recent review focused on the following 4 key points: (1) restoration of rotator cuff strength, focusing on the eccentric capacity of the external rotators, (2) normalization of rotational range of motion with particular focus on internal range of motion, (3) optimization of the flexibility and muscle performance of the scapular muscles, and (4) increasing the functional sport-specific load on the shoulder girdle.

Continue to: A common approach to the care of...

A common approach to the care of a patient after a glenohumeral joint dislocation is to place the patient’s shoulder in a sling for comfort, with permitted pain-free isometric exercise along with passive and assisted elevation up to 100°.16 This is followed by a nonaggressive rehabilitation protocol for 2 months until full recovery, which includes progressive range of motion, strength, proprioception, and return to functional activities.16

More aggressive return-to-play protocols with accelerated timelines and functional progression have been studied, including in a multicenter observational study that followed 45 contact intercollegiate athletes prospectively after in-season anterior glenohumeral instability. Thirty-three of 45 (73%) athletes returned to sport for either all or part of the season after a median 5 days lost from competition, with 12 athletes (27%) successfully completing the season without recurrence. Athletes with a subluxation event were 5.3 times more likely to return to sport during the same season, compared with those with dislocations.17

Dynamic bracing may also allow for a safe and quicker return to sport in athletes18 but recently was shown to not impact recurrent dislocation risk.19

Return to play should be based on subjective assessment as well as objective measurements of range of motion, strength, and dynamic function.15 Patients who continue to have significant weakness and pain at 2 to 3 weeks post injury despite physical therapy should be re-evaluated with an MRI for concomitant rotator cuff tears and need for surgical referral.20

When to consider surgical intervention

In a recent meta-analysis, recurrent dislocation and instability occurred at a rate of 52.9% following nonsurgical treatment.2 The decision to perform surgical intervention is typically made following failure of conservative management. Other considerations include age, gender, bone loss, and cartilage defect.21,22 Age younger than 30 years, participation in competition, contact sports, and male gender have been associated with an increased risk of recurrence.23-25 For this reason, obtaining an MRI at time of first dislocation can help facilitate surgical decisions if the patient is at high risk for surgical need.26

Continue to: An increasing number...

An increasing number of dislocations portends a poor outcome with nonoperative treatment. Kao et al demonstrated a second dislocation leads to another dislocation in 19.6% of cases, while 44.3% of those with a third dislocation event will sustain another dislocation.24 Surgery should be considered for patients with recurrent instability events to prevent persistent instability and decrease the amount of bone loss that can occur with repetitive dislocations.

What are the surgical options?

Several surgical options exist to remedy the unstable shoulder. Procedures can range from an arthroscopic repair to an open stabilization combined with structural bone graft to replace a bone defect caused by repetitive dislocations.

Arthroscopic techniques have become the mainstay of treatment and account for 71% of stabilization procedures performed.21 These techniques cause less pain in the early postoperative period and provide for a faster return to work.27 Arthroscopy has the additional advantage of allowing for complete visualization of the glenohumeral joint to identify and address concomitant pathology, such as intra-articular loose bodies or rotator cuff tears.

Open repair was the mainstay of treatment prior to development of arthroscopic techniques. Some surgeons still prefer this method—especially in high-risk groups—because of a lower risk of recurrent disloca-tion.28 Open techniques often involve detachment and repair of the upper subscapularis tendon and are more likely to produce long-term losses in external rotation range of motion.28

Which one is appropriate for your patient? The decision to pursue an open or arthroscopic procedure and to augment with bone graft depends on the amount of glenoid and humeral head bone loss, patient activity level, risk of recurrent dislocation, and surgeon preference.

Continue to: For the nonathletic population...

For the nonathletic population, the timing of injury is less critical and surgery is typically recommended after conservative treatment has failed. In an athletic population, the timing of injury is a necessary consideration. An injury midseason may be “rehabbed” in hopes of returning to play. Individuals with injuries occurring at the end of a season, who are unable to regain desired function, and/or with peri-articular fractures or associated full-thickness rotator cuff tears may benefit from sooner surgical intervention.21

Owens et al have described appropriate surgical indications and recommendations for an in-season athlete.21 In this particular algorithm, the authors suggest obtaining an MRI for decision making, but this is specific to in-season athletes wishing to return to play. In general, an MRI is not always indicated for patients who wish to receive conservative therapy but would be indicated for surgical considerations. The algorithm otherwise uses bone and soft-tissue injury, recurrent instability, and timing in the season to help determine management.21

Outcomes: Surgery has advantages …

Recurrence rates following surgical intervention are considerably lower than with conservative management, especially among young, active individuals. A recent systematic review by Donohue et al demonstrated recurrent instability rates following surgical intervention as low as 2.4%.29 One study comparing the outcome of arthroscopic repair vs conservative management showed that the risk of postoperative instability was reduced by 20% compared to other treatments.7 Furthermore, early surgical fixation can improve quality of life, produce better functional outcomes, decrease time away from activity, increase patient satisfaction, and slow the development of glenohumeral osteoarthritis produced from recurrent instability.2,7

Complications. Surgery does carry inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, surgical complications, and surgical failure. Recurrent instability is the most common complication following surgical shoulder stabilization. Rates of recurrent instability after surgical stabilization depend on patient age, activity level, and amount of bone loss: males younger than 18 years who participate in contact competitive sports and have significant bone loss are more likely to have recurrent dislocation after surgery.23 The type of surgical procedure selected may decrease this risk.

While the open procedures decrease risk of postoperative instability, these surgeries can pose a significant risk of complications. Major complications for specific open techniques have been reported in up to 30% of patients30 and are associated with lower levels of surgeon experience.31 While the healing of bones and ligaments is always a concern, 1 of the most feared complications following stabilization surgery is iatrogenic nerve injury. Because of the axillary nerve’s close proximity to the inferior glenoid, this nerve can be injured without meticulous care and can result in paralysis of the deltoid muscle. This injury poses a major impediment to normal shoulder function. Some procedures may cause nerve injuries in up to 10% of patients, although most injuries are transient.32

Continue to: Bottom line

Bottom line

Due to the void of evidence-based guidelines for conservative vs surgical management of primary shoulder dislocation, it would be prudent to have a risk-benefit discussion with patients regarding treatment options.

Patients older than 30 years and those with uncomplicated injuries are best suited for conservative management of primary shoulder dislocations. Immobilization is debated and may not change outcomes, but a progressive rehabilitative program after the initial acute injury is helpful. Risk factors for failing conservative management include recurrent dislocation, subsequent arthropathy, and additional concomitant bone or soft-tissue injuries.

Patients younger than 30 years who have complicated injuries with bone or cartilage loss, rotator cuff tears, or recurrent instability, and highly physically active individuals are best suited for surgical management. Shoulder arthroscopy has become the mainstay of surgical treatment for shoulder dislocations. Outcomes are favorable and dislocation recurrence is low after surgical repair. Surgery does carry its own inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, complications during surgery, and surgical failure leading to recurrent instability.

Cayce Onks, DO, MS, ATC, Penn State Hershey, Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine, Family and Community Medicine H154, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-0850; [email protected]

The shoulder, or glenohumeral joint, is the most commonly dislocated large joint; dislocation occurs at a rate of 23.9 per 100,000 person/years.1,2 There are 2 types of dislocation: traumatic anterior dislocation, which accounts for roughly 90% of dislocations, and posterior dislocation (10%).3 Anterior dislocation typically occurs when the patient’s shoulder is forcefully abducted and externally rotated.

The diagnosis is made after review of the history and mechanism of injury and performance of a complete physical exam with imaging studies—the most critical component of diagnosis.4 Standard radiographs (anteroposterior, axillary, and scapular Y) can confirm the presence of a dislocation; once the diagnosis is confirmed, closed reduction of the joint should be performed.1 (Methods of reduction are beyond the scope of this article but have been recently reviewed.5)

Risk for recurrence drives management choices

Following an initial shoulder dislocation, the risk of recurrence is high.6,7 Rates vary based on age, pathology after dislocation, activity level, type of immobilization, and whether surgery was performed. Overall, age is the strongest predictor of recurrence: 72% of patients ages 12 to 22 years, 56% of those ages 23 to 29 years, and 27% of those older than 30 years experience recurrence.6 Patients who have recurrent dislocations are at risk for arthropathy, fear of instability, and worsening surgical outcomes.6

Reducing the risk of a recurrent shoulder dislocation has been the focus of intense study. Proponents of surgical stabilization argue that surgery—rather than a trial of conservative treatment—is best when you consider the high risk of recurrence in young athletes (the population primarily studied), the soft-tissue and bony damage caused by recurrent instability, and the predictable improvement in quality of life following surgery.

In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, there was evidence that, for first-time traumatic shoulder dislocations, early surgery led to fewer repeat shoulder dislocations (number needed to treat [NNT] = 2-4.7). However, a significant number of patients primarily treated nonoperatively did not experience a repeat shoulder dislocation within 2 years.2

The conflicting results from randomized trials comparing operative intervention to conservative management have led surgeons and physicians in other specialties to take different approaches to the management of shoulder dislocation.2 In this review, we aim to summarize considerations for conservative vs surgical management and provide clinical guidance for primary care physicians.

When to try conservative management

Although the initial treatment after a traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation has been debated, a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials showed that at least half of first-time dislocations are successfully treated with conservative management.2 Management can include immobilization for comfort and/or physical therapy. Age will play a role, as mentioned earlier; in general, patients older than 30 have a significant decrease in recurrence rate and are good candidates for conservative therapy.6 It should be noted that much of the research with regard to management of shoulder dislocations has been done in an athletic population.

Continue to: Immobilization may benefit some

Immobilization may benefit some

Recent evidence has determined that the duration of immobilization in internal rotation does not impact recurrent instability.8,9 In patients older than 30, the rate of repeat dislocation is lower, and early mobilization after 1 week is advocated to avoid joint stiffness and minimize the risk of adhesive capsulitis.10

Arm position during immobilization remains controversial.11 In a classic study by Itoi et al, immobilization for 3 weeks in internal rotation vs 10° of external rotation was associated with a recurrence rate of 42% vs 26%, respectively.12 In this study, immobilization in 10° of external rotation was especially beneficial for patients ages 30 years or younger.12

Cadaveric and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have shown external rotation may improve the odds of labral tear healing by positioning the damaged and intact parts of the glenoid labrum in closer proximity.13 While this is theoretically plausible, a recent Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to determine whether immobilization in external rotation has any benefits beyond those offered by internal rotation.14 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that immobilization in external rotation vs internal rotation after a first-time traumatic shoulder dislocation did not change outcomes.2 With that said, most would prefer to immobilize in the internal rotation position for ease.

More research is needed. A Cochrane review highlighted the need for continued research.14 Additionally, most of the available randomized controlled trials to date have consisted of young men, with the majority of dislocations related to sports activities. Women, nonathletes, and older patients have been understudied to date; extrapolating current research to those groups of patients may not be appropriate and should be a focus for future research.2

Physical therapy: The conservative standard of care

Rehabilitation after glenohumeral joint dislocation is the current standard of care in conservative management to reduce the risk for repeat dislocation.15 Depending on the specific characteristics of the instability pattern, the approach may be adapted to the patient. A recent review focused on the following 4 key points: (1) restoration of rotator cuff strength, focusing on the eccentric capacity of the external rotators, (2) normalization of rotational range of motion with particular focus on internal range of motion, (3) optimization of the flexibility and muscle performance of the scapular muscles, and (4) increasing the functional sport-specific load on the shoulder girdle.

Continue to: A common approach to the care of...

A common approach to the care of a patient after a glenohumeral joint dislocation is to place the patient’s shoulder in a sling for comfort, with permitted pain-free isometric exercise along with passive and assisted elevation up to 100°.16 This is followed by a nonaggressive rehabilitation protocol for 2 months until full recovery, which includes progressive range of motion, strength, proprioception, and return to functional activities.16

More aggressive return-to-play protocols with accelerated timelines and functional progression have been studied, including in a multicenter observational study that followed 45 contact intercollegiate athletes prospectively after in-season anterior glenohumeral instability. Thirty-three of 45 (73%) athletes returned to sport for either all or part of the season after a median 5 days lost from competition, with 12 athletes (27%) successfully completing the season without recurrence. Athletes with a subluxation event were 5.3 times more likely to return to sport during the same season, compared with those with dislocations.17

Dynamic bracing may also allow for a safe and quicker return to sport in athletes18 but recently was shown to not impact recurrent dislocation risk.19

Return to play should be based on subjective assessment as well as objective measurements of range of motion, strength, and dynamic function.15 Patients who continue to have significant weakness and pain at 2 to 3 weeks post injury despite physical therapy should be re-evaluated with an MRI for concomitant rotator cuff tears and need for surgical referral.20

When to consider surgical intervention

In a recent meta-analysis, recurrent dislocation and instability occurred at a rate of 52.9% following nonsurgical treatment.2 The decision to perform surgical intervention is typically made following failure of conservative management. Other considerations include age, gender, bone loss, and cartilage defect.21,22 Age younger than 30 years, participation in competition, contact sports, and male gender have been associated with an increased risk of recurrence.23-25 For this reason, obtaining an MRI at time of first dislocation can help facilitate surgical decisions if the patient is at high risk for surgical need.26

Continue to: An increasing number...

An increasing number of dislocations portends a poor outcome with nonoperative treatment. Kao et al demonstrated a second dislocation leads to another dislocation in 19.6% of cases, while 44.3% of those with a third dislocation event will sustain another dislocation.24 Surgery should be considered for patients with recurrent instability events to prevent persistent instability and decrease the amount of bone loss that can occur with repetitive dislocations.

What are the surgical options?

Several surgical options exist to remedy the unstable shoulder. Procedures can range from an arthroscopic repair to an open stabilization combined with structural bone graft to replace a bone defect caused by repetitive dislocations.

Arthroscopic techniques have become the mainstay of treatment and account for 71% of stabilization procedures performed.21 These techniques cause less pain in the early postoperative period and provide for a faster return to work.27 Arthroscopy has the additional advantage of allowing for complete visualization of the glenohumeral joint to identify and address concomitant pathology, such as intra-articular loose bodies or rotator cuff tears.

Open repair was the mainstay of treatment prior to development of arthroscopic techniques. Some surgeons still prefer this method—especially in high-risk groups—because of a lower risk of recurrent disloca-tion.28 Open techniques often involve detachment and repair of the upper subscapularis tendon and are more likely to produce long-term losses in external rotation range of motion.28

Which one is appropriate for your patient? The decision to pursue an open or arthroscopic procedure and to augment with bone graft depends on the amount of glenoid and humeral head bone loss, patient activity level, risk of recurrent dislocation, and surgeon preference.

Continue to: For the nonathletic population...

For the nonathletic population, the timing of injury is less critical and surgery is typically recommended after conservative treatment has failed. In an athletic population, the timing of injury is a necessary consideration. An injury midseason may be “rehabbed” in hopes of returning to play. Individuals with injuries occurring at the end of a season, who are unable to regain desired function, and/or with peri-articular fractures or associated full-thickness rotator cuff tears may benefit from sooner surgical intervention.21

Owens et al have described appropriate surgical indications and recommendations for an in-season athlete.21 In this particular algorithm, the authors suggest obtaining an MRI for decision making, but this is specific to in-season athletes wishing to return to play. In general, an MRI is not always indicated for patients who wish to receive conservative therapy but would be indicated for surgical considerations. The algorithm otherwise uses bone and soft-tissue injury, recurrent instability, and timing in the season to help determine management.21

Outcomes: Surgery has advantages …

Recurrence rates following surgical intervention are considerably lower than with conservative management, especially among young, active individuals. A recent systematic review by Donohue et al demonstrated recurrent instability rates following surgical intervention as low as 2.4%.29 One study comparing the outcome of arthroscopic repair vs conservative management showed that the risk of postoperative instability was reduced by 20% compared to other treatments.7 Furthermore, early surgical fixation can improve quality of life, produce better functional outcomes, decrease time away from activity, increase patient satisfaction, and slow the development of glenohumeral osteoarthritis produced from recurrent instability.2,7

Complications. Surgery does carry inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, surgical complications, and surgical failure. Recurrent instability is the most common complication following surgical shoulder stabilization. Rates of recurrent instability after surgical stabilization depend on patient age, activity level, and amount of bone loss: males younger than 18 years who participate in contact competitive sports and have significant bone loss are more likely to have recurrent dislocation after surgery.23 The type of surgical procedure selected may decrease this risk.

While the open procedures decrease risk of postoperative instability, these surgeries can pose a significant risk of complications. Major complications for specific open techniques have been reported in up to 30% of patients30 and are associated with lower levels of surgeon experience.31 While the healing of bones and ligaments is always a concern, 1 of the most feared complications following stabilization surgery is iatrogenic nerve injury. Because of the axillary nerve’s close proximity to the inferior glenoid, this nerve can be injured without meticulous care and can result in paralysis of the deltoid muscle. This injury poses a major impediment to normal shoulder function. Some procedures may cause nerve injuries in up to 10% of patients, although most injuries are transient.32

Continue to: Bottom line

Bottom line

Due to the void of evidence-based guidelines for conservative vs surgical management of primary shoulder dislocation, it would be prudent to have a risk-benefit discussion with patients regarding treatment options.

Patients older than 30 years and those with uncomplicated injuries are best suited for conservative management of primary shoulder dislocations. Immobilization is debated and may not change outcomes, but a progressive rehabilitative program after the initial acute injury is helpful. Risk factors for failing conservative management include recurrent dislocation, subsequent arthropathy, and additional concomitant bone or soft-tissue injuries.

Patients younger than 30 years who have complicated injuries with bone or cartilage loss, rotator cuff tears, or recurrent instability, and highly physically active individuals are best suited for surgical management. Shoulder arthroscopy has become the mainstay of surgical treatment for shoulder dislocations. Outcomes are favorable and dislocation recurrence is low after surgical repair. Surgery does carry its own inherent risks of infection, anesthesia effects, complications during surgery, and surgical failure leading to recurrent instability.

Cayce Onks, DO, MS, ATC, Penn State Hershey, Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Penn State College of Medicine, Family and Community Medicine H154, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey, PA 17033-0850; [email protected]

1. Lin K, James E, Spitzer E, et al. Pediatric and adolescent anterior shoulder instability: clinical management of first time dislocators. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30:49-56.

2. Kavaja L, Lähdeoja T, Malmivaara A, et al. Treatment after traumatic shoulder dislocation: a systematic review with a network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:1498-1506.

3. Brelin A, Dickens JF. Posterior shoulder instability. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2017;25:136-143.

4. Galvin JW, Ernat JJ, Waterman BR, et al. The epidemiology and natural history of anterior shoulder dislocation. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10:411-424.

5. Rozzi SL, Anderson JM, Doberstein ST, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: immediate management of appendicular joint dislocations. J Athl Train. 2018;53:1117-1128.

6. Hovelius L, Saeboe M. Arthropathy after primary anterior shoulder dislocation: 223 shoulders prospectively followed up for twenty-five years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:339-347.

7. Polyzois I, Dattani R, Gupta R, et al. Traumatic first time shoulder dislocation: surgery vs non-operative treatment. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2016;4:104-108.

8. Cox CL, Kuhn JE. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of acute shoulder dislocation in the athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008;7:263-268.

9. Kuhn JE. Treating the initial anterior shoulder dislocation—an evidence-based medicine approach. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2006;14:192-198.

10. Smith TO. Immobilization following traumatic anterior glenohumeral joint dislocation: a literature review. Injury. 2006;37:228-237.

11. Liavaag S, Brox JI, Pripp AH, et al. Immobilization in external rotation after primary shoulder dislocation did not reduce the risk of recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:897-904.

12. Itoi E, Hatakeyama Y, Sato T, et al. Immobilization in external rotation after shoulder dislocation reduces the risk of recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2124-2131.

13. Miller BS, Sonnabend DH, Hatrick C, et al. Should acute anterior dislocations of the shoulder be immobilized in external rotation? A cadaveric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:589-592.

14. Hanchard NCA, Goodchild LM, Kottam L. Conservative management following closed reduction of traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD004962.

15. Cools AM, Borms D, Castelein B, et al. Evidence-based rehabilitation of athletes with glenohumeral instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:382-389.

16. Lafuente JLA, Marco SM, Pequerul JMG. Controversies in the management of the first time shoulder dislocation. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:1001-1010.

17. Dickens JF, Owens BD, Cameron KL, et al. Return to play and recurrent instability after in-season anterior shoulder instability: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2842-2850.

18. Conti M, Garofalo R, Castagna A, et al. Dynamic brace is a good option to treat first anterior shoulder dislocation in season. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101(suppl 2):169-173.

19. Shanley E, Thigpen C, Brooks J, et al. Return to sport as an outcome measure for shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1062-1067.

20. Gombera MM, Sekiya JK. Rotator cuff tear and glenohumeral instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2448-2456.

21. Owens BD, Dickens JF, Kilcoyne KG, et al. Management of mid-season traumatic anterior shoulder instability in athletes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:518-526.

22. Ozturk BY, Maak TG, Fabricant P, et al. Return to sports after arthroscopic anterior stabilization in patients aged younger than 25 years. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:1922-1931.

23. Balg F, Boileau P. The instability severity index score. A simple preoperative score to select patients for arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1470-1477.

24. Kao J-T, Chang C-L, Su W-R, et al. Incidence of recurrence after shoulder dislocation: a nationwide database study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:1519-1525.

25. Porcillini G, Campi F, Pegreffi F, et al. Predisposing factors for recurrent shoulder dislocation after arthroscopic treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2537-2542.

26. Magee T. 3T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:86-92.

27. Green MR, Christensen KP. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart procedures: a comparison of early morbidity and complications. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:371-374.

28. Khatri K, Arora H, Chaudhary S, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials involving anterior shoulder instability. Open Orthop J. 2018;12:411-418.

29. Donohue MA, Owens BD, Dickens JF. Return to play following anterior shoulder dislocations and stabilization surgery. Clin Sports Med. 2016;35:545-561.

30. Griesser MJ, Harris JD, McCoy BW, et al. Complications and re-operations after Bristow-Latarjet shoulder stabilization: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:286-292.

31. Ekhtiari S, Horner NS, Bedi A, et al. The learning curve for the Latarjet procedure: a systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6:2325967118786930.

32. Shah AA, Butler RB, Romanowski J, et al. Short-term complications of the Latarjet procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:495-501.

1. Lin K, James E, Spitzer E, et al. Pediatric and adolescent anterior shoulder instability: clinical management of first time dislocators. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2018;30:49-56.

2. Kavaja L, Lähdeoja T, Malmivaara A, et al. Treatment after traumatic shoulder dislocation: a systematic review with a network meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52:1498-1506.

3. Brelin A, Dickens JF. Posterior shoulder instability. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2017;25:136-143.

4. Galvin JW, Ernat JJ, Waterman BR, et al. The epidemiology and natural history of anterior shoulder dislocation. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2017;10:411-424.

5. Rozzi SL, Anderson JM, Doberstein ST, et al. National Athletic Trainers’ Association position statement: immediate management of appendicular joint dislocations. J Athl Train. 2018;53:1117-1128.

6. Hovelius L, Saeboe M. Arthropathy after primary anterior shoulder dislocation: 223 shoulders prospectively followed up for twenty-five years. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18:339-347.

7. Polyzois I, Dattani R, Gupta R, et al. Traumatic first time shoulder dislocation: surgery vs non-operative treatment. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2016;4:104-108.

8. Cox CL, Kuhn JE. Operative versus nonoperative treatment of acute shoulder dislocation in the athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008;7:263-268.

9. Kuhn JE. Treating the initial anterior shoulder dislocation—an evidence-based medicine approach. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2006;14:192-198.

10. Smith TO. Immobilization following traumatic anterior glenohumeral joint dislocation: a literature review. Injury. 2006;37:228-237.

11. Liavaag S, Brox JI, Pripp AH, et al. Immobilization in external rotation after primary shoulder dislocation did not reduce the risk of recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93:897-904.

12. Itoi E, Hatakeyama Y, Sato T, et al. Immobilization in external rotation after shoulder dislocation reduces the risk of recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:2124-2131.

13. Miller BS, Sonnabend DH, Hatrick C, et al. Should acute anterior dislocations of the shoulder be immobilized in external rotation? A cadaveric study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13:589-592.

14. Hanchard NCA, Goodchild LM, Kottam L. Conservative management following closed reduction of traumatic anterior dislocation of the shoulder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(4):CD004962.

15. Cools AM, Borms D, Castelein B, et al. Evidence-based rehabilitation of athletes with glenohumeral instability. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24:382-389.

16. Lafuente JLA, Marco SM, Pequerul JMG. Controversies in the management of the first time shoulder dislocation. Open Orthop J. 2017;11:1001-1010.

17. Dickens JF, Owens BD, Cameron KL, et al. Return to play and recurrent instability after in-season anterior shoulder instability: a prospective multicenter study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:2842-2850.

18. Conti M, Garofalo R, Castagna A, et al. Dynamic brace is a good option to treat first anterior shoulder dislocation in season. Musculoskelet Surg. 2017;101(suppl 2):169-173.

19. Shanley E, Thigpen C, Brooks J, et al. Return to sport as an outcome measure for shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med. 2019;47:1062-1067.

20. Gombera MM, Sekiya JK. Rotator cuff tear and glenohumeral instability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2448-2456.

21. Owens BD, Dickens JF, Kilcoyne KG, et al. Management of mid-season traumatic anterior shoulder instability in athletes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20:518-526.

22. Ozturk BY, Maak TG, Fabricant P, et al. Return to sports after arthroscopic anterior stabilization in patients aged younger than 25 years. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:1922-1931.

23. Balg F, Boileau P. The instability severity index score. A simple preoperative score to select patients for arthroscopic or open shoulder stabilisation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:1470-1477.

24. Kao J-T, Chang C-L, Su W-R, et al. Incidence of recurrence after shoulder dislocation: a nationwide database study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:1519-1525.

25. Porcillini G, Campi F, Pegreffi F, et al. Predisposing factors for recurrent shoulder dislocation after arthroscopic treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2537-2542.

26. Magee T. 3T MRI of the shoulder: is MR arthrography necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:86-92.

27. Green MR, Christensen KP. Arthroscopic versus open Bankart procedures: a comparison of early morbidity and complications. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:371-374.

28. Khatri K, Arora H, Chaudhary S, et al. Meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials involving anterior shoulder instability. Open Orthop J. 2018;12:411-418.

29. Donohue MA, Owens BD, Dickens JF. Return to play following anterior shoulder dislocations and stabilization surgery. Clin Sports Med. 2016;35:545-561.

30. Griesser MJ, Harris JD, McCoy BW, et al. Complications and re-operations after Bristow-Latarjet shoulder stabilization: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:286-292.

31. Ekhtiari S, Horner NS, Bedi A, et al. The learning curve for the Latarjet procedure: a systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6:2325967118786930.

32. Shah AA, Butler RB, Romanowski J, et al. Short-term complications of the Latarjet procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:495-501.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Start with conservative management of shoulder dislocation in patients older than 30 years and those with uncomplicated injuries. B

› Discourage strict immobilization; its utility is debated and it may not change outcomes. B

› Recommend a progressive rehabilitative program after the initial acute shoulder injury. B

› Consider surgical management for patients younger than 30 years who have complicated injuries with bone or cartilage loss, rotator cuff tears, or recurrent instability or for the highly physically active individual. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Low back pain in youth: Recognizing red flags

Low back pain in not uncommon in children and adolescents.1-3 Although the prevalence of low back pain in children < 7 years is low, it increases with age, with studies reporting lifetime prevalence at age 12 years between 16% and 18% and rates as high as 66% by 16 years of age.4,5 Although children and adolescents usually have pain that is transient and benign without a defined cause, structural causes of low back pain should be considered in school-aged children with pain that persists for > 3 to 6 weeks. 4 The most common structural causes of adolescent low back pain are reviewed here.

Etiology: A mixed bag

Back pain in school-aged children is most commonly due to muscular strain, overuse, or poor posture. The pain is often transient in nature and responds to rest and postural education.4,6 A herniated disc is an uncommon finding in younger school-aged children, but incidence increases slightly among older adolescents, particularly those who are active in collision sports and/or weight-lifting.7,8 Pain caused by a herniated disc often radiates along the distribution of the sciatic nerve and worsens during lumbar flexion.

Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis are important causes of back pain in children. Spondylolysis is defined as a defect or abnormality of the pars interarticularis and surrounding lamina and pedicle. Spondylolisthesis, which is less common, is defined as the translation or “slippage” of one vertebral segment in relation to the next caudal segment. These conditions commonly occur as a result of repetitive stress.

In a prospective study of adolescents < 19 years with low back pain for > 2 weeks, the prevalence of spondylolysis was 39.7%.9 Adolescent athletes with symptomatic low back pain are more likely to have spondylolysis than nonathletes (32% vs 2%, respectively).2,10 Pain is often made worse by extension of the spine. Spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis can be congenital or acquired, and both can be asymptomatic. Children and teens who are athletes are at higher risk for symptomatic spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis.10-12 This is especially true for those involved in gymnastics, dance, football, and/or volleyball, where a repetitive load is placed onto an extended spine.

Idiopathic scoliosis is an abnormal lateral curvature of the spine that usually develops during adolescence and worsens with growth. Historically, painful scoliosis was considered rare, but more recently researchers determined that children with scoliosis have a higher rate of pain compared to their peers.13,14 School-aged children with scoliosis were found to be at 2 times the risk of low back pain compared to those without scoliosis.13 It is important to identify scoliosis in adolescents so that progression can be monitored.

Screening for scoliosis in primary care is somewhat controversial. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) finds insufficient evidence for screening asymptomatic adolescents for scoliosis.15 This recommendation is based on the fact that there is little evidence on the effect of screening on long-term outcomes. Screening may also lead to unnecessary radiation. Conversely, a position statement released by the Scoliosis Research Society, the Pediatric Orthopedic Society of North America, the American Association of Orthopedic Surgeons, and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends scoliosis screening during routine pediatric office visits.16 Screening for girls is recommended at ages 10 and 12 years, and for boys, once between ages 13 and 14 years. The statement highlights evidence showing that focused screening by appropriate personnel has value in detecting a clinically significant curve (> 20°).

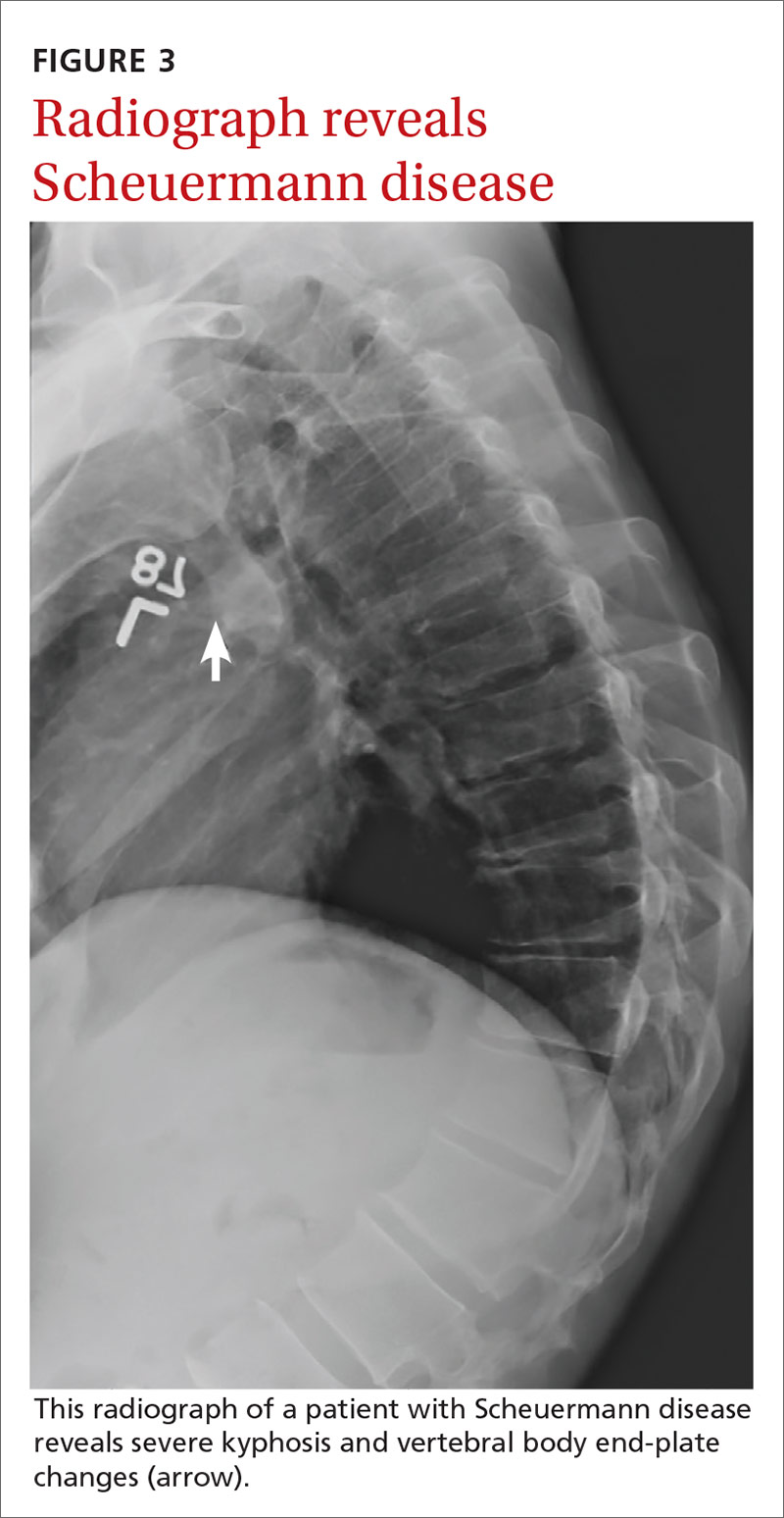

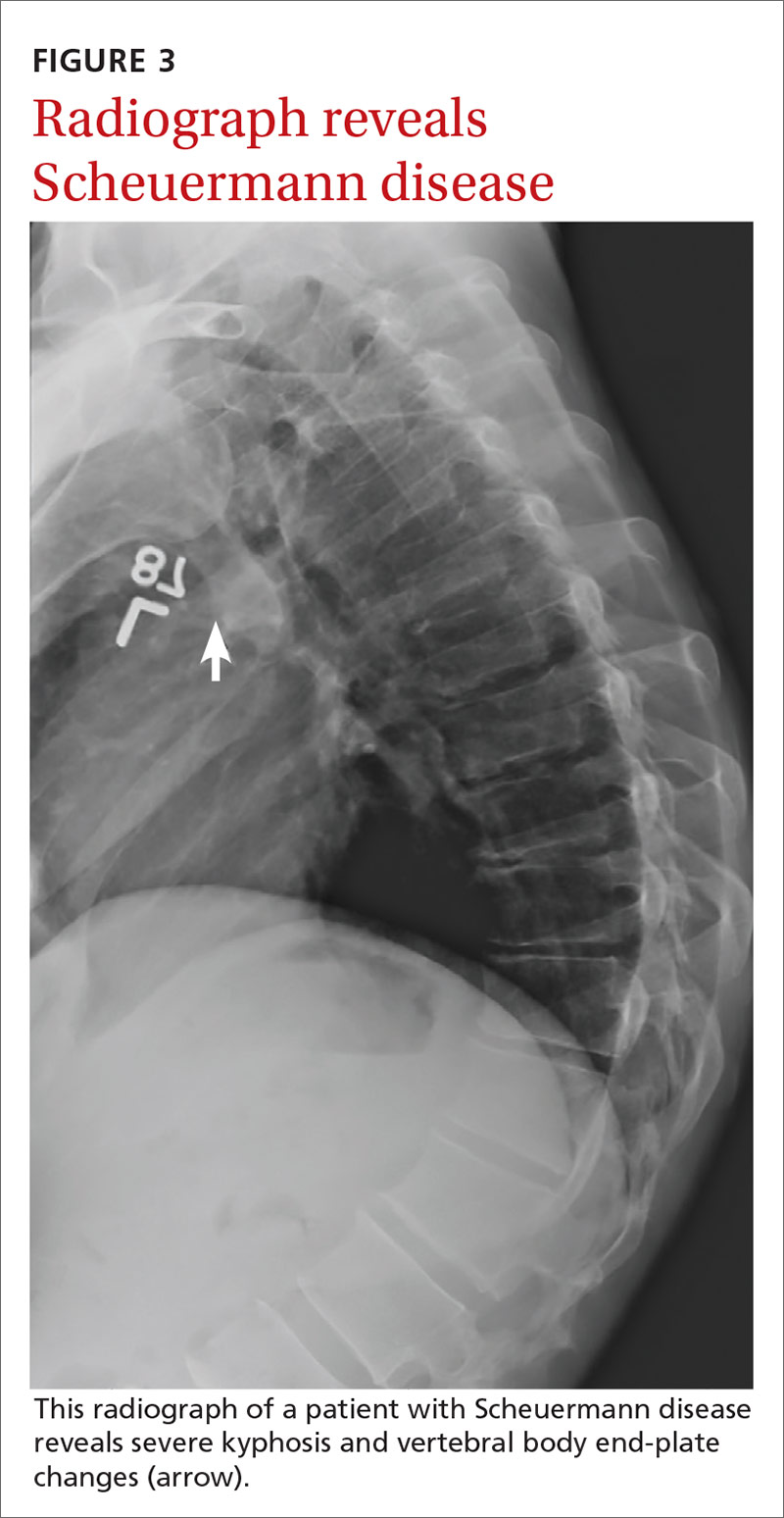

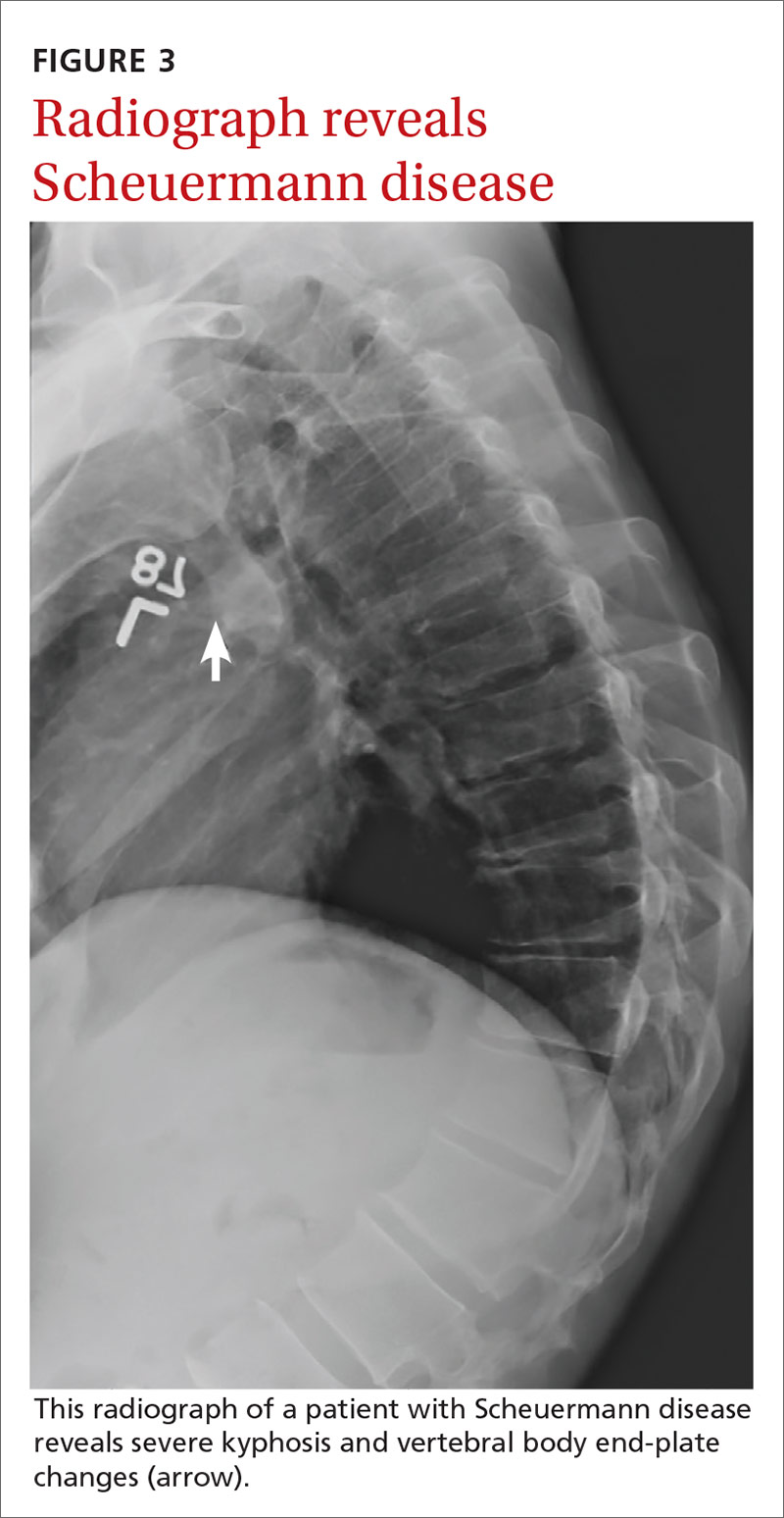

Scheuermann disease is a rare cause of back pain in children that usually develops during adolescence and results in increasing thoracic kyphosis. An autosomal dominant mutation plays a role in this disease of the growth cartilage endplate; repetitive strain on the growth cartilage is also a contributing factor.17,18 An atypical variant manifests with kyphosis in the thoracolumbar region.17

Continue to: Other causes of low back pain

Other causes of low back pain—including inflammatory arthritis, infection (eg, discitis), and tumor—are rare in children but must always be considered, especially in the setting of persistent symptoms.4,19-21 More on the features of these conditions is listed in TABLE 1.1-7,13-15,17-30

History: Focus on onset, timing, and duration of symptoms

As with adults, obtaining a history that includes the onset, timing, and duration of symptoms is key in the evaluation of low back pain in children, as is obtaining a history of the patient’s activities; sports that repetitively load the lumbar spine in an extended position increase the risk of injury.10

Specific risk factors for low back pain in children and adolescents are poorly understood.4,9,31 Pain can be associated with trauma, or it can have a more progressive or insidious onset. Generally, pain that is present for up to 6 weeks and is intermittent or improving has a self-limited course. Pain that persists beyond 3 to 6 weeks or is worsening is more likely to have an anatomical cause that needs further evaluation.2,3,10,21

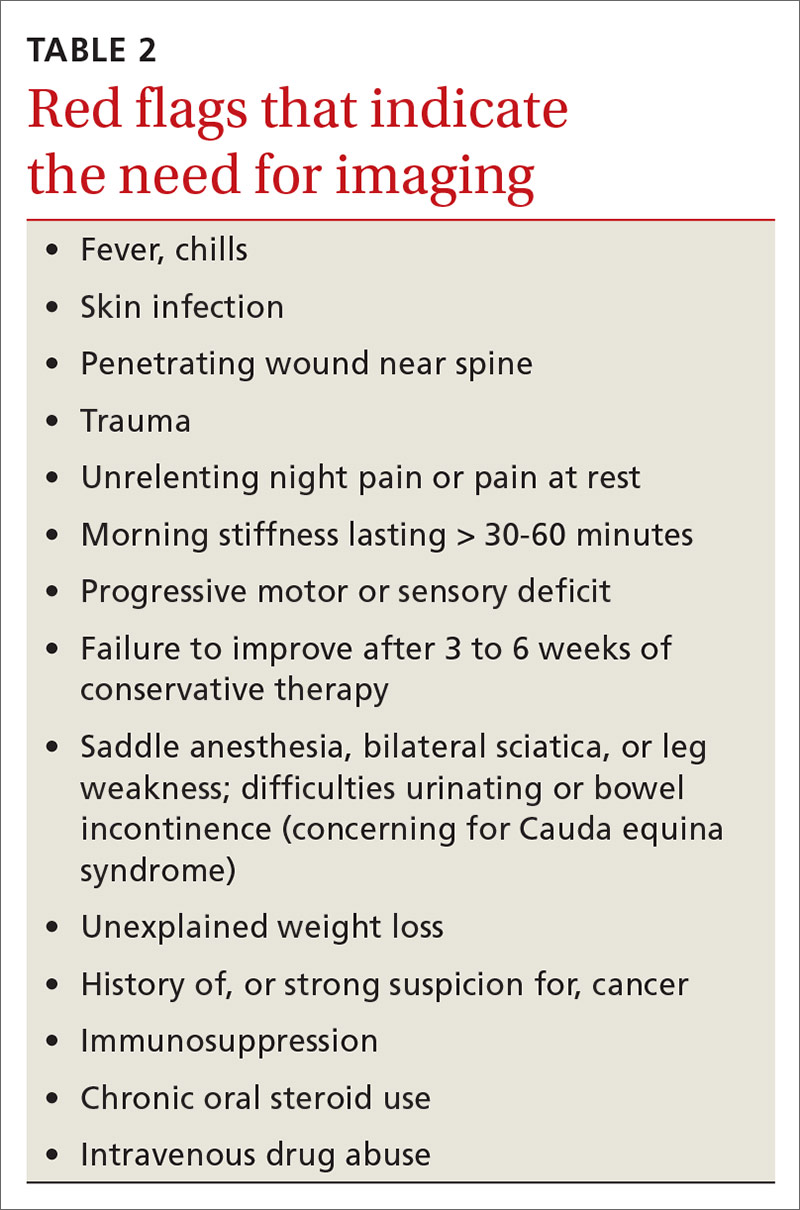

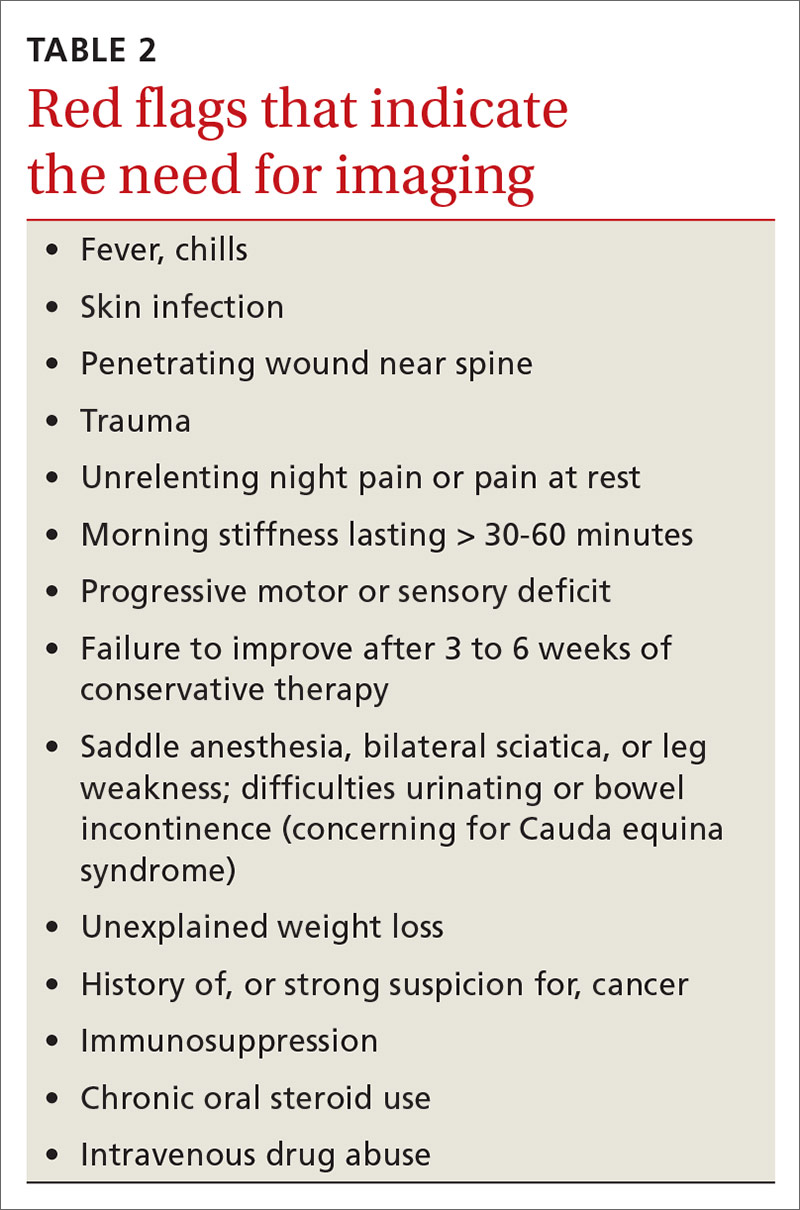

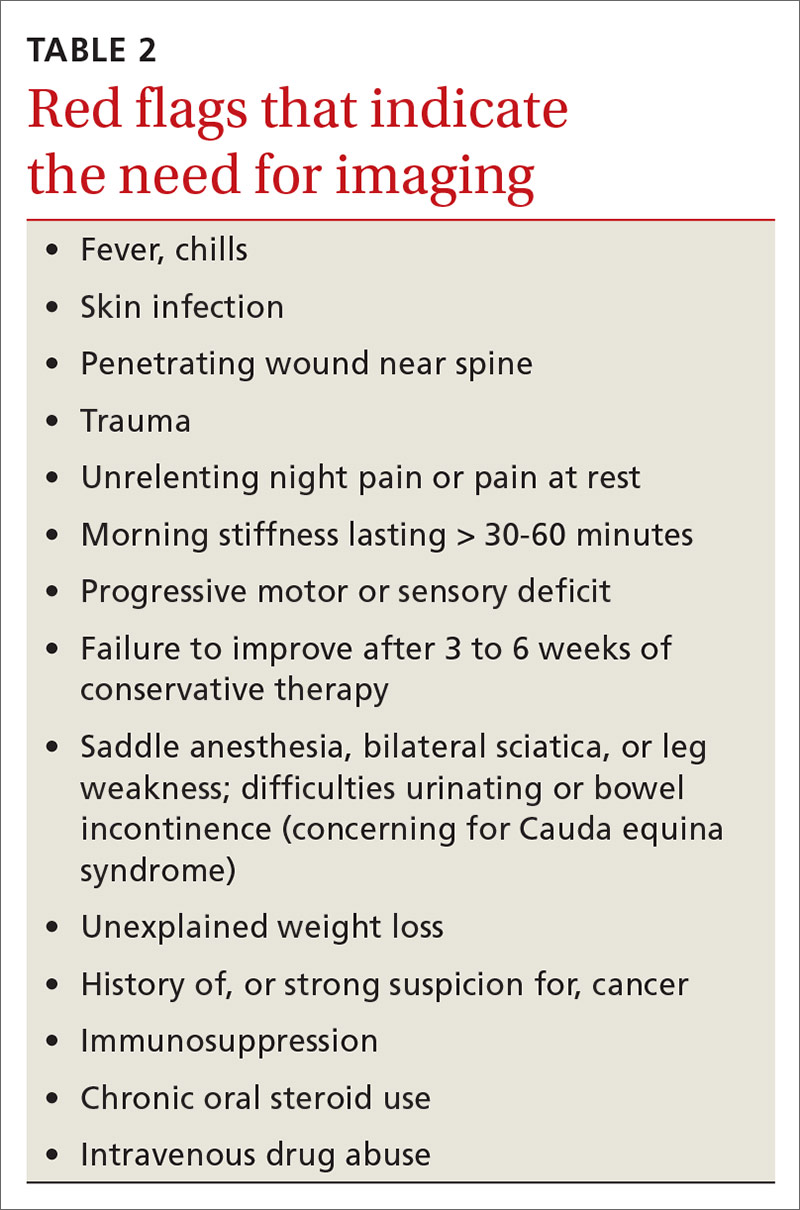

Identifying exacerbating and alleviating factors can provide useful information. Pain that is worse with lumbar flexion is more likely to come from muscular strain or disc pathology. Pain with extension is more likely due to a structural cause such as spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, or Scheuermann disease.2,4,10,17,18,21 See TABLE 2 for red flag symptoms that indicate the need for imaging and further work-up.

The physical exam: Visualize, assess range of motion, and reproduce pain

The physical examination of any patient with low back pain should include direct visualization and inspection of the back, spine, and pelvis; palpation of the spine and paraspinal regions; assessment of lumbar range of motion and of the lumbar nerve roots, including tests of sensation, strength, and deep tendon reflexes; and an evaluation of the patient’s posture, which can provide clues to underlying causes of pain.

Continue to: Increased thoracic kyphosis...

Increased thoracic kyphosis that is not reversible is concerning for Scheuermann disease.9,17,18 A significant elevation in one shoulder or side of the pelvis can be indicative of scoliosis. Increased lumbar lordosis may predispose a patient to spondylolysis.

In patients with spondylolysis, lumbar extension will usually reproduce pain, which is often unilateral. Hyperextension in a single-leg stance, commonly known as the Stork test, is positive for unilateral spondylolysis when it reproduces pain on the ipsilateral side. The sensitivity of the Stork test for unilateral spondylolysis is approximately 50%.32 (For more information on the Stork test, see www.physio-pedia.com/Stork_test.)

Pain reproduced with lumbar flexion is less concerning for bony pathology and is most often related to soft-tissue strain. Lumbar flexion with concomitant radicular pain is associated with disc pathology.8 Pain with a straight-leg raise is also associated with disk pathology, especially if raising the contralateral leg increases pain.8

Using a scoliometer. Evaluate the flexed spine for the presence of asymmetry, which can indicate scoliosis.33 If asymmetry is present, use a scoliometer to determine the degree of asymmetry. Zero to 5° is considered clinically insignificant; monitor and reevaluate these patients at subsequent visits.34,35 Ten degrees or more of asymmetry with a scoliometer should prompt you to order radiographs.35,36 A smartphone-based scoliometer for iPhones was evaluated in 1 study and was shown to have reasonable reliability and validity for clinical use.37

Deformity of the lower extremities. Because low back pain may be caused by biomechanical or structural deformity of the lower extremities, examine the flexibility of the hip flexors, gluteal musculature, hamstrings, and the iliotibial band.38 In addition, evaluate for leg-length discrepancy and lower-extremity malalignment, such as femoral anteversion, tibial torsion, or pes planus.

Continue to: Imaging

Imaging: Know when it’s needed

Although imaging of the lumbar spine is often unnecessary in the presence of acute low back pain in children, always consider imaging in the setting of bony tenderness, pain that wakes a patient from sleep, and in the setting of other red flag symptoms (see TABLE 2). Low back pain in children that is reproducible with lumbar extension is concerning for spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis. If the pain with extension persists beyond 3 to 6 weeks, order imaging starting with radiographs.2,39

Traditionally, 4 views of the spine—anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique (one right and one left)—were obtained, but recent evidence indicates that 2 views (AP and lateral) have similar sensitivity and specificity to 4 views with significantly reduced radiation exposure.2,39 Because the sensitivity of plain films is relatively low, consider more advanced imaging if spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis is strongly suspected. Recent studies indicate that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be as effective as computed tomography (CT) or bone scan and has the advantage of lower radiation (FIGURE 1).2,22

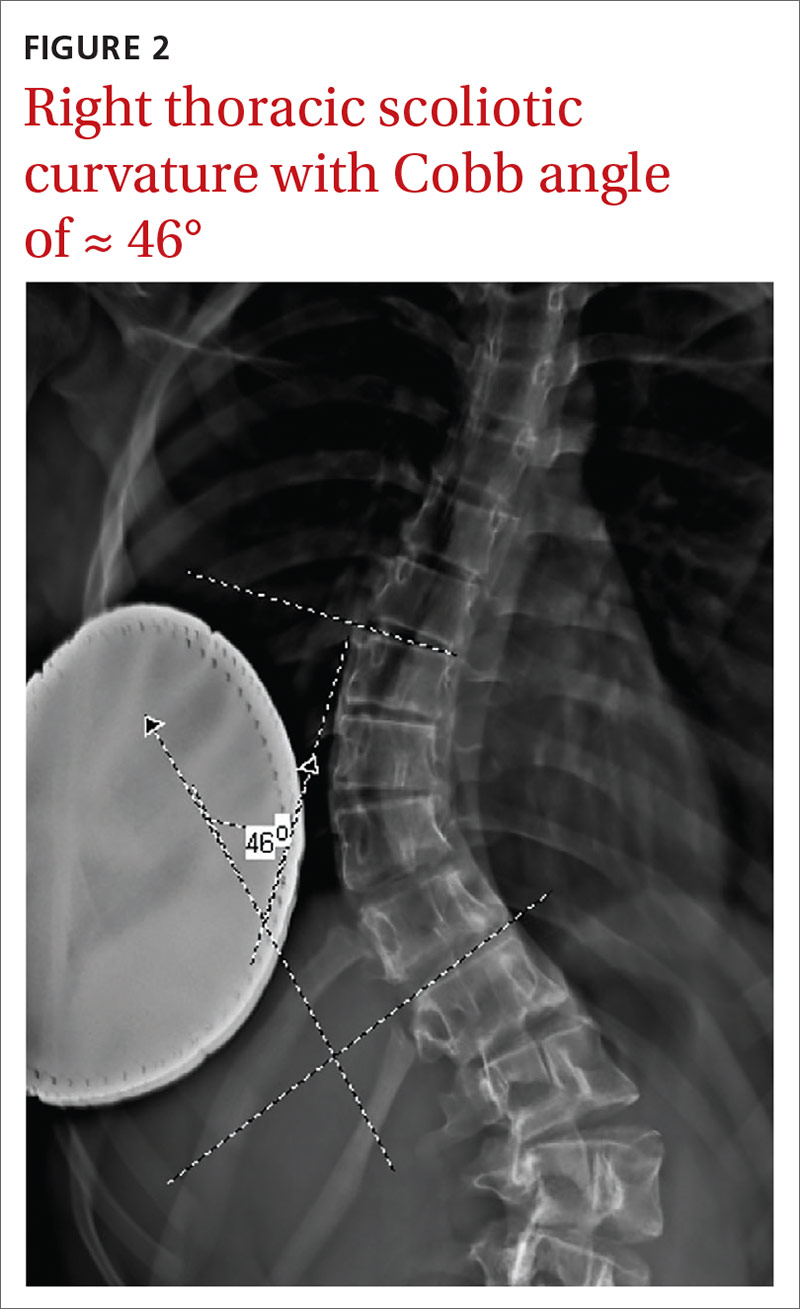

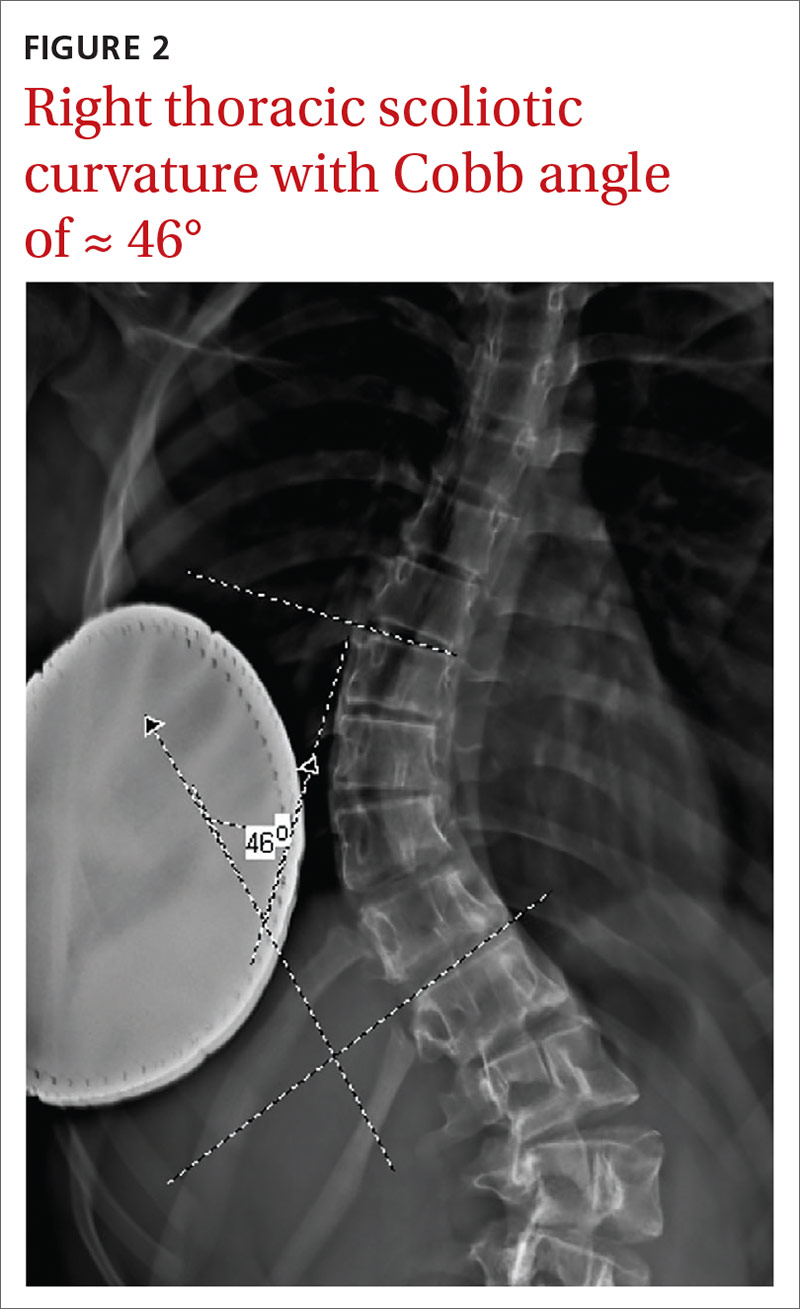

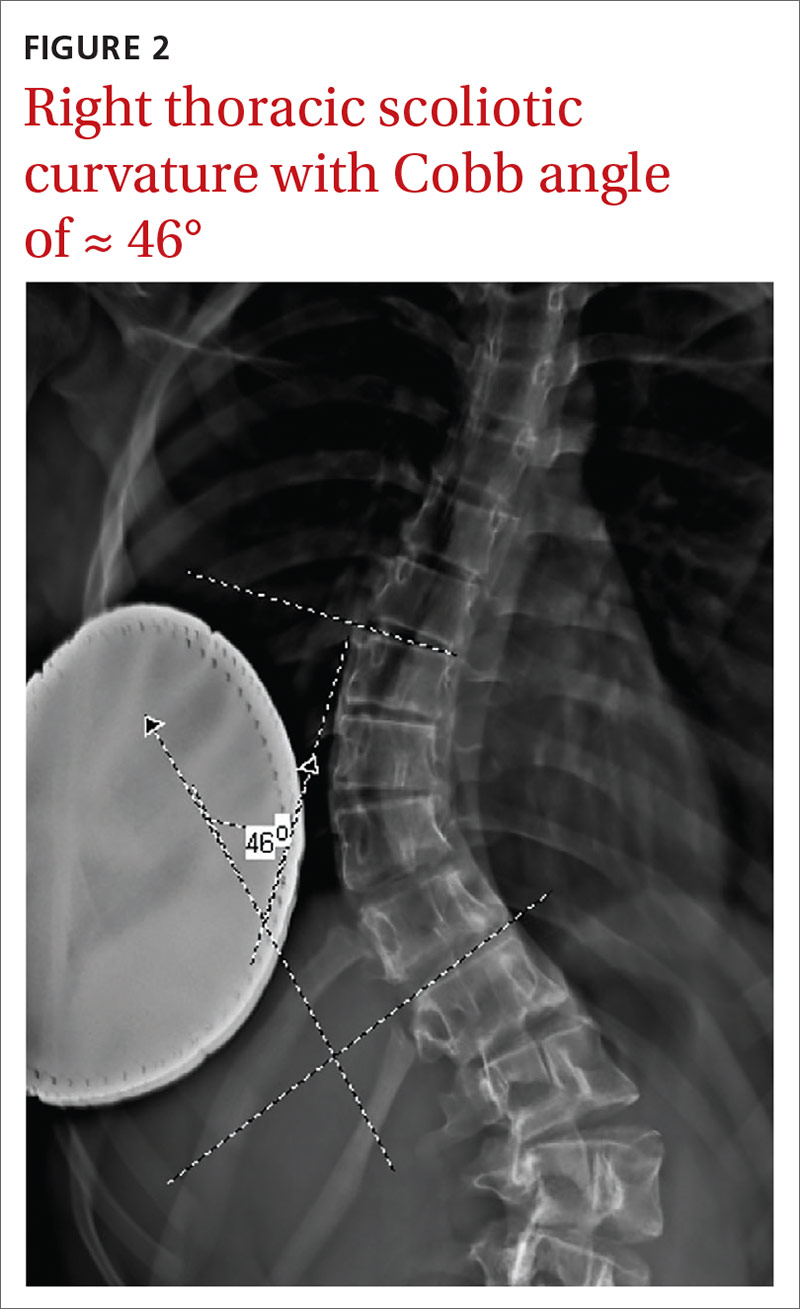

Similarly, order radiographs if there is > 10° of asymmetry noted on physical exam using a scoliometer.15,23 Calculate the Cobb angle to determine the severity of scoliosis. Refer patients with angles ≥ 20° to a pediatric orthopedist for monitoring of progression and consideration of bracing (FIGURE 2).23,34 For patients with curvatures between 10° and 19°, repeat imaging every 6 to 12 months. Because scoliosis is a risk factor for spondylolysis, evaluate radiographs in the setting of painful scoliosis for the presence of a spondylolysis.34,35

If excessive kyphosis is noted on exam, order radiographs to evaluate for Scheuermann disease. Classic imaging findings include Schmorl nodes, vertebral endplate changes, and anterior wedging (FIGURE 3).17,18

In the absence of the above concerns, defer imaging of the lumbar spine until after adequate rest and rehabilitation have been attempted.

Continue to: Treatment typically involves restor physical therapy

Treatment typically involves restor physical therapy

Most cases of low back pain in children and adolescents are benign and self-limited. Many children with low back pain can be treated with relative rest from the offending activity. For children with more persistent pain, physical therapy (PT) is often indicated. Similar to that for adults, there is little evidence for specific PT programs to help children with low back pain. Rehabilitation should be individualized based on the condition being treated.

Medications. There have been no high-quality studies on the benefit of medications to treat low back pain in children. Studies have shown nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have value in adults, and they are likely safe for use in children,40 but the risk of opiate abuse is significantly increased in adolescents who have been prescribed opiate pain medication prior to 12th grade.41

Lumbar disc herniation. Although still relatively rare, lumbar disc herniation is more common in older children and adolescents than in younger children and is treated similarly to that in adults.8 Range-of-motion exercise to restore lumbar motion is often first-line treatment. Research has shown that exercises that strengthen the abdominal or “core” musculature help prevent the return of low back pain.24,25

In the case of spondylolysis or spondylolisthesis, rest from activity is generally required for a minimum of 4 to 6 weeks. Rehabilitation in the form of range of motion, especially into the lumbar extension, and spinal stabilization exercises are effective for both reducing pain and restoring range-of-motion and strength.42 Have patients avoid heavy backpacks, which can reproduce pain. Children often benefit from leaving a second set of schoolbooks at home. For most patients with spondylolysis, conservative treatment with rehabilitation is equal to or better than surgical intervention in returning the patient to his/her pre-injury activity level.26,43,44 When returning athletes to their sport, aggressive PT, defined as rest for < 10 weeks prior to initiating PT, is superior to delaying PT beyond 10 weeks of rest.27

Idiopathic scoliosis. Much of the literature on the treatment of scoliosis is focused on limiting progression of the scoliotic curvature. Researchers thought that more severe curves were associated with more severe pain, but a recent systematic review showed that back pain can occur in patients with even small curvatures.28 Treatment for patients with smaller degrees of curvature is similar to that for mechanical low back pain. PT may have a role in the treatment of scoliosis, but there is little evidence in the literature of its effectiveness.

Continue to: A Cochrane review showed...

A Cochrane review showed that PT and exercise-based treatments had no effect on back pain or disability in patients with scoliosis.29 And outpatient PT alone, in the absence of bracing, does not arrest progression of the scoliotic curvature.35 One trial did demonstrate that an intensive inpatient treatment program of 4 to 6 weeks for patients with curvature of at least 40° reduced progression of curvature compared to an untreated control group at 1 year.34 The outcomes of functional mobility and pain were not measured. Follow-up data on curve progression beyond 1 year are not available. Unfortunately, intensive inpatient treatment is not readily available or cost-effective for most patients with scoliosis.

Scheuermann disease. The mainstay of treatment for mild Scheuermann disease is advising the patient to avoid repetitive loading of the spine. Patients should avoid sports such as competitive weight-lifting, gymnastics, and football. Lower impact athletics are encouraged. Refer patients with pain to PT to address posture and core stabilization. Patients with severe kyphosis may require surgery.17,18

Bracing: Rarely helpful for low back pain

The use of lumbar braces or corsets is rarely helpful for low back pain in children. Bracing in the setting of spondylolysis is controversial.One study indicated that bracing in combination with activity restriction and lumbar extension exercise is superior to activity restriction and lumbar flexion exercises alone.43 But a meta-analysis did not demonstrate a significant difference in recovery when bracing was added.44 Bracing may help to reduce pain initially in patients with spondylolysis who have pain at rest. Bracing is not recommended for patients with pain that abates with activity modification.

Scoliosis and Scheuermann kyphosis. Treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis usually consists of observation and periodic reevaluation. Bracing is a mainstay of the nonsurgical management of scoliosis and is appropriate for curves of 20° to 40°; studies have reported successful control of curve progression in > 70% of patients.36 According to 1 study, the number of cases of scoliosis needed to treat with bracing to prevent 1 surgery is 3.30 Surgery is often indicated for patients with curvatures > 40°, although this is also debated.33

Bracing is used rarely for Scheuermann kyphosis but may be helpful in more severe or painful cases.17

CORRESPONDENCE

Shawn F. Phillips, MD, MSPT, 500 University Drive H154, Hershey, PA, 17033; [email protected].

1. MacDonald J, Stuart E, Rodenberg R. Musculoskeletal low back pain in school-aged children: a review. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:280-287.

2. Tofte JN CarlLee TL, Holte AJ, et al. Imaging pediatric spondylolysis: a systematic review. Spine. 2017;42:777-782.

3. Sakai T, Sairyo K, Suzue N, et al. Incidence and etiology of lumbar spondylolysis: review of the literature. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15:281-288.

4. Calvo-Muñoz I, Gómez-Conesa A, Sánchez-Meca J. Prevalence of low back pain in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. BMC Pediatrics. 2013;13:14.

5. Bernstein RM, Cozen H. Evaluation of back pain in children and adolescents. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76:1669-1676.

6. Taxter AJ, Chauvin NA, Weiss PF. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain in the pediatric population. Phys Sportsmed. 2014;42:94-104.

7. Haus BM, Micheli LJ. Back pain in the pediatric and adolescent athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2012;31:423-440.

8. Lavelle WF, Bianco A, Mason R, et al. Pediatric disk herniation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19:649-656.

9. Taimela S, Kujala UM, Salminen JJ, et al. The prevalence of low back pain among children and adolescents: a nationwide, cohort-based questionnaire survey in Finland. Spine. 1997;22:1132-1136.

10. Schroeder GD, LaBella CR, Mendoza M, et al. The role of intense athletic activity on structural lumbar abnormalities in adolescent patients with symptomatic low back pain. Eur Spine J. 2016;25:2842-2848.