User login

A 32-year-old woman comes to your office for help with her recurrent migraines, which she’s had since her early 20s. She is otherwise healthy and active. She is frustrated by the frequency of her migraines and the resulting debilitation. She has tried prophylactic medications in the past but stopped taking them because of the adverse effects. What do you recommend for treatment?

Daily preventive medication can be helpful for patients whose chronic migraines have a significant impact on their lives. Many have a goal of reducing headache frequency, severity, and/or disability, while avoiding acute medication escalation.2 An estimated 38% of patients with migraine are appropriate candidates for prophylactic therapy, but only 3% to 13% are taking preventive medications.3

Evidence-based guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society state that antiepileptic drugs (divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate) and many ß-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, timolol) are effective and should be recommended for migraine prevention.2 Medications such as antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine) and other ß-blockers (atenolol, nadolol) are probably effective and can be considered.2 However, adverse effects—including somnolence—are listed as “frequent” with amitriptyline and “occasional to frequent” with topiramate.4

Researchers have investigated melatonin before. But a 2010 double-blind, crossover RCT of 46 patients with two to seven migraine attacks per month found no significant difference in reduction of headache frequency between extended-release melatonin (2 mg taken 1 h before bed) and placebo over an eight-week period.5

STUDY SUMMARY

More than 50% reduction in headache frequency

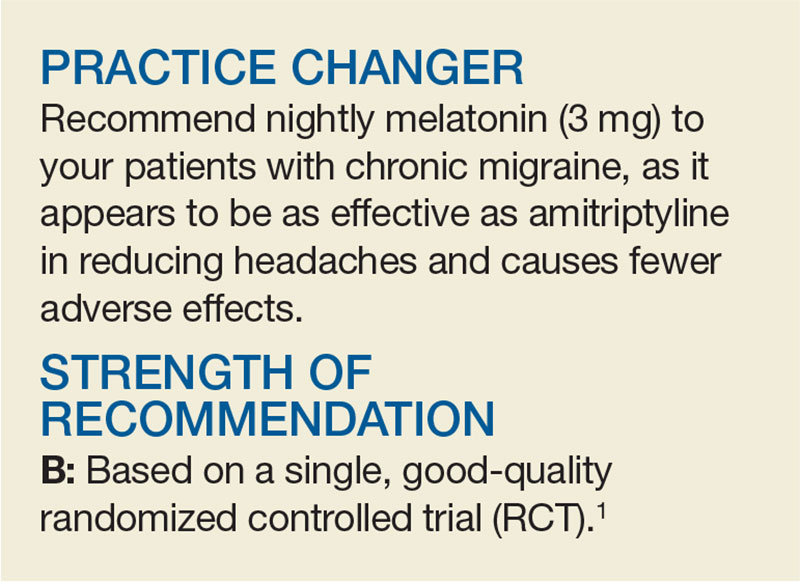

This RCT, conducted in Brazil, compared the effectiveness of melatonin to amitriptyline and placebo for migraine prevention in 196 adults (ages 18 to 65) with chronic migraine.1 Eligible patients had a history of at least three migraine attacks or four migraine headache days per month. Patients were randomized to take identical-appearing melatonin (3 mg), amitriptyline (25 mg), or placebo nightly. The investigators appear to have concealed allocation adequately and used double-blinding.

The primary outcome was the number of headache days per month, compared to baseline. Secondary endpoints included reduction in migraine intensity, duration, number of analgesics used, and percentage of patients with more than 50% reduction in migraine headache days.

Compared to placebo, headache days per month were reduced in both the melatonin group (6.2 d vs 4.6 d, respectively; mean difference [MD], –1.6) and the amitriptyline group (6.2 d vs 5 d, respectively; MD, –1.2) at 12 weeks, based on intention-to-treat analysis. Mean headache intensity (0-10 pain scale) was also lower at 12 weeks in the melatonin group (4.8 vs 3.6; MD, –1.2) and in the amitriptyline group (4.8 vs 3.5; MD, –1.3), compared to placebo.

Headache duration (hours/month) at 12 weeks was reduced in both groups (MD, –4.4 h for amitriptyline and –4.8 h for melatonin), as was the number of analgesics used (MD for amitriptyline and for melatonin, –1) when compared to placebo. There was no significant difference between the melatonin and amitriptyline groups for these outcomes.

Patients taking melatonin were more likely to have more than 50% improvement in headache frequency compared to those taking amitriptyline (54% vs 39%; number needed to treat [NNT], 7). Melatonin worked much better than placebo (54% vs 20%; NNT, 3).

Adverse events were reported more often in the amitriptyline group than in the melatonin group (46 vs 16), with daytime sleepiness being the most frequent complaint (41% of patients in the amitriptyline group vs 18% of the melatonin group; number needed to harm [NNH], 5). There was no significant difference in adverse events between melatonin and placebo (16 vs 17). Melatonin resulted in weight loss (mean, –0.14 kg), whereas those taking amitriptyline gained weight (+0.97 kg).

WHAT’S NEW

Effective alternative with minimal adverse effects

Melatonin is an accessible and affordable option for prevention of migraine. The 3-mg dosing reduces headache frequency—measured by both the number of migraine headache days per month and the percentage of patients with a more than 50% reduction in headache events—as well as headache intensity, with minimal adverse effects.

CAVEATS

Product consistency, missing study data

This trial used 3-mg dosing, so it is not clear if other doses are also effective. In addition, melatonin’s OTC status means there could be a lack of consistency in quality/actual doses between brands.

Furthermore, in this trial, neither the amitriptyline nor the melatonin dose was titrated according to patient response or adverse effects, as it might be in clinical practice. As a result, we are not sure of the actual lowest effective dose or if greater effect (with continued minimal adverse effects) could be achieved with higher doses.

Lastly, 69% to 75% of patients in the treatment groups completed the 16-week trial, and the researchers reported using three different analytic techniques to estimate missing data. (For example, the primary endpoint analysis included data for 90.8% of randomized patients [178 of 196], and the authors treated all missing data as nonheadache days.) It is unclear how the missing data would affect the outcome—although in this type of analysis, it would tend toward a null effect.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Challenges are negligible

There are really no challenges to implementing this practice changer; melatonin is readily available and is affordable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[5]:320-322).

1. Gonçalves AL, Martini Ferreira A, Ribeiro RT, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg and placebo for migraine prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:1127-1132.

2. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

3. Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al; The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343-349.

4. Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55:754-762.

5. Alstadhaug KB, Odeh F, Salvesen R, et al. Prophylaxis of migraine with melatonin: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2010;75:1527-1532.

A 32-year-old woman comes to your office for help with her recurrent migraines, which she’s had since her early 20s. She is otherwise healthy and active. She is frustrated by the frequency of her migraines and the resulting debilitation. She has tried prophylactic medications in the past but stopped taking them because of the adverse effects. What do you recommend for treatment?

Daily preventive medication can be helpful for patients whose chronic migraines have a significant impact on their lives. Many have a goal of reducing headache frequency, severity, and/or disability, while avoiding acute medication escalation.2 An estimated 38% of patients with migraine are appropriate candidates for prophylactic therapy, but only 3% to 13% are taking preventive medications.3

Evidence-based guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society state that antiepileptic drugs (divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate) and many ß-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, timolol) are effective and should be recommended for migraine prevention.2 Medications such as antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine) and other ß-blockers (atenolol, nadolol) are probably effective and can be considered.2 However, adverse effects—including somnolence—are listed as “frequent” with amitriptyline and “occasional to frequent” with topiramate.4

Researchers have investigated melatonin before. But a 2010 double-blind, crossover RCT of 46 patients with two to seven migraine attacks per month found no significant difference in reduction of headache frequency between extended-release melatonin (2 mg taken 1 h before bed) and placebo over an eight-week period.5

STUDY SUMMARY

More than 50% reduction in headache frequency

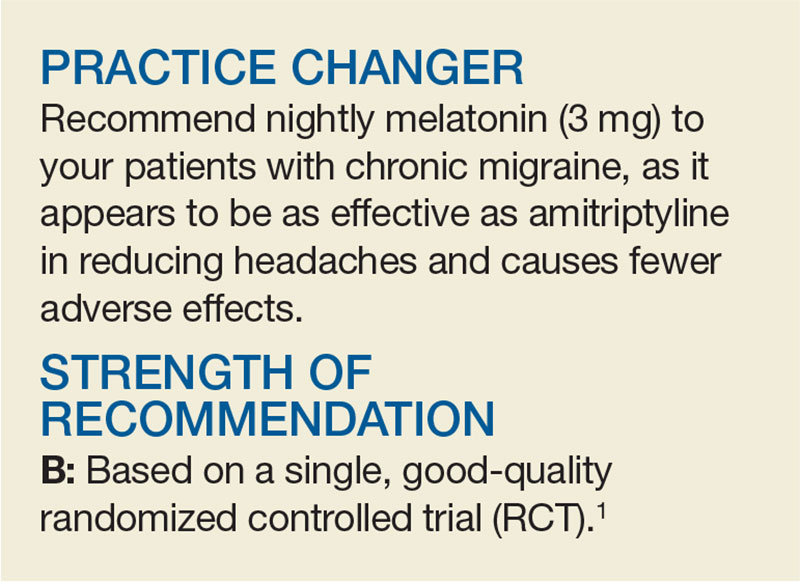

This RCT, conducted in Brazil, compared the effectiveness of melatonin to amitriptyline and placebo for migraine prevention in 196 adults (ages 18 to 65) with chronic migraine.1 Eligible patients had a history of at least three migraine attacks or four migraine headache days per month. Patients were randomized to take identical-appearing melatonin (3 mg), amitriptyline (25 mg), or placebo nightly. The investigators appear to have concealed allocation adequately and used double-blinding.

The primary outcome was the number of headache days per month, compared to baseline. Secondary endpoints included reduction in migraine intensity, duration, number of analgesics used, and percentage of patients with more than 50% reduction in migraine headache days.

Compared to placebo, headache days per month were reduced in both the melatonin group (6.2 d vs 4.6 d, respectively; mean difference [MD], –1.6) and the amitriptyline group (6.2 d vs 5 d, respectively; MD, –1.2) at 12 weeks, based on intention-to-treat analysis. Mean headache intensity (0-10 pain scale) was also lower at 12 weeks in the melatonin group (4.8 vs 3.6; MD, –1.2) and in the amitriptyline group (4.8 vs 3.5; MD, –1.3), compared to placebo.

Headache duration (hours/month) at 12 weeks was reduced in both groups (MD, –4.4 h for amitriptyline and –4.8 h for melatonin), as was the number of analgesics used (MD for amitriptyline and for melatonin, –1) when compared to placebo. There was no significant difference between the melatonin and amitriptyline groups for these outcomes.

Patients taking melatonin were more likely to have more than 50% improvement in headache frequency compared to those taking amitriptyline (54% vs 39%; number needed to treat [NNT], 7). Melatonin worked much better than placebo (54% vs 20%; NNT, 3).

Adverse events were reported more often in the amitriptyline group than in the melatonin group (46 vs 16), with daytime sleepiness being the most frequent complaint (41% of patients in the amitriptyline group vs 18% of the melatonin group; number needed to harm [NNH], 5). There was no significant difference in adverse events between melatonin and placebo (16 vs 17). Melatonin resulted in weight loss (mean, –0.14 kg), whereas those taking amitriptyline gained weight (+0.97 kg).

WHAT’S NEW

Effective alternative with minimal adverse effects

Melatonin is an accessible and affordable option for prevention of migraine. The 3-mg dosing reduces headache frequency—measured by both the number of migraine headache days per month and the percentage of patients with a more than 50% reduction in headache events—as well as headache intensity, with minimal adverse effects.

CAVEATS

Product consistency, missing study data

This trial used 3-mg dosing, so it is not clear if other doses are also effective. In addition, melatonin’s OTC status means there could be a lack of consistency in quality/actual doses between brands.

Furthermore, in this trial, neither the amitriptyline nor the melatonin dose was titrated according to patient response or adverse effects, as it might be in clinical practice. As a result, we are not sure of the actual lowest effective dose or if greater effect (with continued minimal adverse effects) could be achieved with higher doses.

Lastly, 69% to 75% of patients in the treatment groups completed the 16-week trial, and the researchers reported using three different analytic techniques to estimate missing data. (For example, the primary endpoint analysis included data for 90.8% of randomized patients [178 of 196], and the authors treated all missing data as nonheadache days.) It is unclear how the missing data would affect the outcome—although in this type of analysis, it would tend toward a null effect.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Challenges are negligible

There are really no challenges to implementing this practice changer; melatonin is readily available and is affordable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[5]:320-322).

A 32-year-old woman comes to your office for help with her recurrent migraines, which she’s had since her early 20s. She is otherwise healthy and active. She is frustrated by the frequency of her migraines and the resulting debilitation. She has tried prophylactic medications in the past but stopped taking them because of the adverse effects. What do you recommend for treatment?

Daily preventive medication can be helpful for patients whose chronic migraines have a significant impact on their lives. Many have a goal of reducing headache frequency, severity, and/or disability, while avoiding acute medication escalation.2 An estimated 38% of patients with migraine are appropriate candidates for prophylactic therapy, but only 3% to 13% are taking preventive medications.3

Evidence-based guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society state that antiepileptic drugs (divalproex sodium, sodium valproate, topiramate) and many ß-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, timolol) are effective and should be recommended for migraine prevention.2 Medications such as antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine) and other ß-blockers (atenolol, nadolol) are probably effective and can be considered.2 However, adverse effects—including somnolence—are listed as “frequent” with amitriptyline and “occasional to frequent” with topiramate.4

Researchers have investigated melatonin before. But a 2010 double-blind, crossover RCT of 46 patients with two to seven migraine attacks per month found no significant difference in reduction of headache frequency between extended-release melatonin (2 mg taken 1 h before bed) and placebo over an eight-week period.5

STUDY SUMMARY

More than 50% reduction in headache frequency

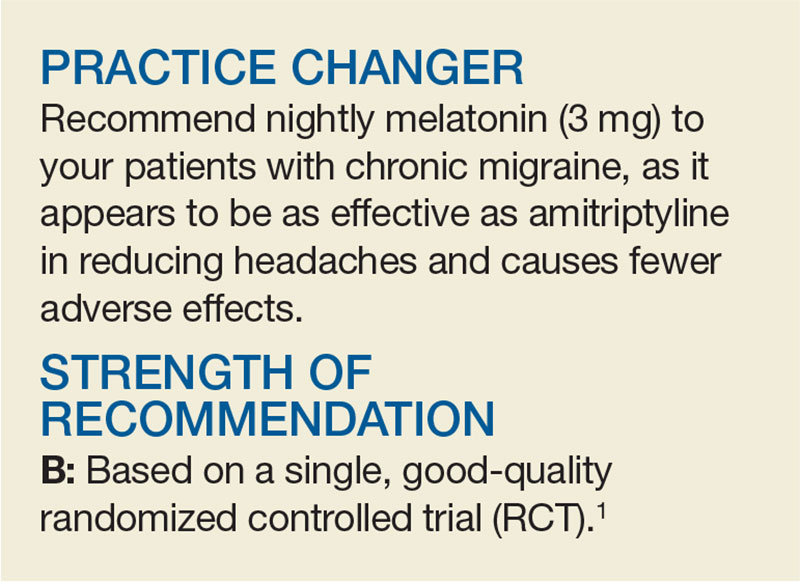

This RCT, conducted in Brazil, compared the effectiveness of melatonin to amitriptyline and placebo for migraine prevention in 196 adults (ages 18 to 65) with chronic migraine.1 Eligible patients had a history of at least three migraine attacks or four migraine headache days per month. Patients were randomized to take identical-appearing melatonin (3 mg), amitriptyline (25 mg), or placebo nightly. The investigators appear to have concealed allocation adequately and used double-blinding.

The primary outcome was the number of headache days per month, compared to baseline. Secondary endpoints included reduction in migraine intensity, duration, number of analgesics used, and percentage of patients with more than 50% reduction in migraine headache days.

Compared to placebo, headache days per month were reduced in both the melatonin group (6.2 d vs 4.6 d, respectively; mean difference [MD], –1.6) and the amitriptyline group (6.2 d vs 5 d, respectively; MD, –1.2) at 12 weeks, based on intention-to-treat analysis. Mean headache intensity (0-10 pain scale) was also lower at 12 weeks in the melatonin group (4.8 vs 3.6; MD, –1.2) and in the amitriptyline group (4.8 vs 3.5; MD, –1.3), compared to placebo.

Headache duration (hours/month) at 12 weeks was reduced in both groups (MD, –4.4 h for amitriptyline and –4.8 h for melatonin), as was the number of analgesics used (MD for amitriptyline and for melatonin, –1) when compared to placebo. There was no significant difference between the melatonin and amitriptyline groups for these outcomes.

Patients taking melatonin were more likely to have more than 50% improvement in headache frequency compared to those taking amitriptyline (54% vs 39%; number needed to treat [NNT], 7). Melatonin worked much better than placebo (54% vs 20%; NNT, 3).

Adverse events were reported more often in the amitriptyline group than in the melatonin group (46 vs 16), with daytime sleepiness being the most frequent complaint (41% of patients in the amitriptyline group vs 18% of the melatonin group; number needed to harm [NNH], 5). There was no significant difference in adverse events between melatonin and placebo (16 vs 17). Melatonin resulted in weight loss (mean, –0.14 kg), whereas those taking amitriptyline gained weight (+0.97 kg).

WHAT’S NEW

Effective alternative with minimal adverse effects

Melatonin is an accessible and affordable option for prevention of migraine. The 3-mg dosing reduces headache frequency—measured by both the number of migraine headache days per month and the percentage of patients with a more than 50% reduction in headache events—as well as headache intensity, with minimal adverse effects.

CAVEATS

Product consistency, missing study data

This trial used 3-mg dosing, so it is not clear if other doses are also effective. In addition, melatonin’s OTC status means there could be a lack of consistency in quality/actual doses between brands.

Furthermore, in this trial, neither the amitriptyline nor the melatonin dose was titrated according to patient response or adverse effects, as it might be in clinical practice. As a result, we are not sure of the actual lowest effective dose or if greater effect (with continued minimal adverse effects) could be achieved with higher doses.

Lastly, 69% to 75% of patients in the treatment groups completed the 16-week trial, and the researchers reported using three different analytic techniques to estimate missing data. (For example, the primary endpoint analysis included data for 90.8% of randomized patients [178 of 196], and the authors treated all missing data as nonheadache days.) It is unclear how the missing data would affect the outcome—although in this type of analysis, it would tend toward a null effect.

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Challenges are negligible

There are really no challenges to implementing this practice changer; melatonin is readily available and is affordable.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[5]:320-322).

1. Gonçalves AL, Martini Ferreira A, Ribeiro RT, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg and placebo for migraine prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:1127-1132.

2. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

3. Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al; The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343-349.

4. Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55:754-762.

5. Alstadhaug KB, Odeh F, Salvesen R, et al. Prophylaxis of migraine with melatonin: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2010;75:1527-1532.

1. Gonçalves AL, Martini Ferreira A, Ribeiro RT, et al. Randomised clinical trial comparing melatonin 3 mg, amitriptyline 25 mg and placebo for migraine prevention. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:1127-1132.

2. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

3. Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al; The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention Advisory Group. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68:343-349.

4. Silberstein SD. Practice parameter: evidence-based guidelines for migraine headache (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2000;55:754-762.

5. Alstadhaug KB, Odeh F, Salvesen R, et al. Prophylaxis of migraine with melatonin: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology. 2010;75:1527-1532.