User login

The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among male US veterans is higher than in the general population.1 Veterans with COPD have higher rates of comorbidities and increased respiratory-related and all-cause health care use, including the use of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT).2-5 It has been well established that LTOT reduces all-cause mortality in patients with COPD and

Delivery of domiciliary LTOT entails placing a nasal cannula into both nostrils and loosely securing it around both ears throughout the wake-sleep cycle. Several veterans with hypoxemic CRF due to COPD at the Jesse Brown Veterans Affairs Medical Center (JBVAMC) in Chicago, Illinois, who were receiving LTOT reported nasal cannula dislodgement (NCD) while they slept. However, the clinical significance and impact of these repeated episodes on respiratory-related health care utilization, such as frequent COPD exacerbations with hospitalization, were not recognized.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether veterans with hypoxemic CRF due to COPD and receiving 24-hour LTOT at JBVAMC were experiencing NCD during sleep and, if so, its impact on

METHODS

We reviewed electronic health records (EHRs) of veterans with hypoxemic CRF from COPD who received 24-hour LTOT administered through nasal cannula and were followed

Pertinent patient demographics, clinical and physiologic variables, and hospitalizations with length of JBVAMC stay for each physician-diagnosed COPD exacerbation in the preceding year from the date last seen in the clinic were abstracted from EHRs. Overall hospital cost, defined as a veteran overnight stay in either the medical intensive care unit (MICU) or a general acute medicine bed in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facility, was calculated for each hospitalization for physician-diagnosed COPD exacerbation using VA Managerial Cost Accounting System National Cost Extracts for inpatient encounters.15 We then contacted each veteran by telephone and asked whether they had experienced NCD and, if so, its weekly frequency ranging from once to nightly.

Data Analysis

Data were reported as mean (SD) where appropriate. The t test and Fisher exact test were used as indicated. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The study protocol

RESULTS

During the study period,

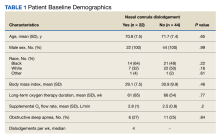

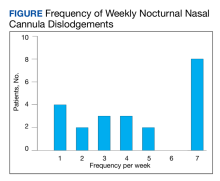

Of the 75 patients, 66 (88%) responded to the telephone survey and 22 patients (33%) reported weekly episodes of NCD while they slept (median, 4 dislodgments per week). (Table 1). Eight patients (36%) reported nightly NCDs (Figure). All 66 respondents were male and 14 of 22 in the NCD group as well as 21 of 44 in the no NCD group were Black veterans. The mean age was similar in both groups: 71 years in the NCD group and 72 years in the no NCD group. There were no statistically significant differences in demographics, including prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), supplemental oxygen flow rate, and duration of LTOT, or in pulmonary function test results between patients who did and did not experience NCD while sleeping (Table 2).

Ten of 22 patients (45%) with NCD and 9 of 44 patients (20%) without NCD were hospitalized at the JBVAMC for ≥ 1 COPD exacerbation in the preceding year that was diagnosed by a physician (P = .045). Three of 22 patients (14%) with NCD and no patients in the no NCD group were admitted to the MICU. No patients required intubation and mechanical ventilation during hospitalization, and no patients died. Overall hospital costs were 25% ($64,342) higher in NCD group compared with the no NCD group and were attributed to the MICU admissions in the NCD group (Table 3). Nine veterans did not respond to repeated telephone calls. One physician-diagnosed COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization was documented in the nonresponder group; the patient was hospitalized for 2 days. One veteran died before being contacted.

DISCUSSION

There are 3 new findings in this study.

Nocturnal arterial oxygen desaturation in patients with COPD without evidence of OSA may contribute to the frequency of exacerbations.16 Although the mechanism(s) underlying this phenomenon is uncertain, we posit that prolonged nocturnal airway wall hypoxia could amplify underlying chronic inflammation through local generation of reactive oxygen species, thereby predisposing patients to exacerbations. Frequent COPD exacerbations promote disease progression and health status decline and are associated with increased mortality.11,13 Moreover, hospitalization of patients with COPD is the largest contributor to the annual direct cost of COPD per patient.10,12 The higher hospitalization rate observed in the NCD group in our study suggests that interruption of supplemental oxygen delivery while asleep may be a risk factor for COPD exacerbation. Alternatively, an independent factor or factors may have contributed to both NCD during sleep and COPD exacerbation in these patients or an impending exacerbation resulted in sleep disturbances that led to NCD. Additional research is warranted on veterans with hypoxemic CRF from COPD who are receiving LTOT and report frequent NCD during sleep that may support or refute these hypotheses.

To the best of our knowledge, NCD during sleep has not been previously reported in patients

Limitations

This was a small, single-site study, comprised entirely of male patients who are predominantly Black veterans. The telephone interviews with veterans self-reporting NCD during their sleep are prone to recall bias. In addition, the validity and reproducibility of NCD during sleep were not addressed in this study. Missing data from 9 nonresponders may have introduced a nonresponse bias in data analysis and interpretation. The overall hospital cost for a COPD exacerbation at JBVAMC was derived from VA data; US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services or commercial carrier data may be different.15,21 Lastly, access to LTOT for veterans with hypoxemic CRF from COPD is regulated and supervised at VA medical facilities.14 This process may be different for patients outside the VA. Taken together, it is difficult to generalize our initial observations to non-VA patients with hypoxemic CRF from COPD who are receiving LTOT. We suggest a large, prospective study of veterans be conducted to determine the prevalence of NCD during sleep and its relationship with COPD exacerbations in veterans receiving LTOT with hypoxemic CRF due to COPD.

CONCLUSIONS

Acknowledgments

We thank Yolanda Davis, RRT, and George Adam for their assistance with this project.

1. Boersma P, Cohen RA, Zelaya CE, Moy E. Multiple chronic conditions among veterans and nonveterans: United States, 2015-2018. Natl Health Stat Report. 2021;(153):1-13. doi:10.15620/cdc:101659

2. Sharafkhaneh A, Petersen NJ, Yu H-J, Dalal AA, Johnson ML, Hanania NA. Burden of COPD in a government health care system: a retrospective observational study using data from the US Veterans Affairs population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:125-132. doi:10.2147/copd.s8047

3. LaBedz SL, Krishnan JA, Chung Y-C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease outcomes at Veterans Affairs versus non-Veterans Affairs hospitals. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2021;8(3):306-313. doi:10.15326/jcopdf.2021.0201

4. Darnell K, Dwivedi AK, Weng Z, Panos RJ. Disproportionate utilization of healthcare resources among veterans with COPD: a retrospective analysis of factors associated with COPD healthcare cost. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2013;11:13. doi:10.1186/1478-7547-11-13

5. Bamonti PM, Robinson SA, Wan ES, Moy ML. Improving physiological, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a narrative review in US Veterans with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

6. Cranston JM, Crockett AJ, Moss JR, Alpers JH. Domiciliary oxygen for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2005(4):CD001744. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001744.pub2

7. Lacasse Y, Tan AM, Maltais F, Krishnan JA. Home oxygen in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(10):1254-1264. doi:10.1164/rccm.201802-0382CI

8. Jacobs SS, Krishnan JA, Lederer DJ, et al. Home oxygen therapy for adults with chronic lung disease. An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(10):e121-e141. doi:10.1164/rccm.202009-3608ST

9. AARC. AARC clinical practice guideline. Oxygen therapy in the home or alternate site health care facility--2007 revision & update. Respir Care. 2007;52(8):1063-1068.

10. Foo J, Landis SH, Maskell J, et al. Continuing to confront COPD international patient survey: economic impact of COPD in 12 countries. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152618. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152618

11. Rothnie KJ, Müllerová H, Smeeth L, Quint JK. Natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in a general practice-based population with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(4):464-471. doi:10.1164/rccm.201710-2029OC

12. Stanford RH, Engel-Nitz NM, Bancroft T, Essoi B. The identification and cost of acute chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in a United States population healthcare claims database. COPD. 2020;17(5):499-508. doi:10.1080/15412555.2020.1817357

13. Hurst JR, Han MK, Singh B, et al. Prognostic risk factors for moderate-to-severe exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic literature review. Respir Res. 2022;23(1):213. doi:10.1186/s12931-022-02123-5

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Home oxygen program. VHA Directive 1173.13(1). Published August 5, 2020. Accessed February 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=8947

15. Phibbs CS, Barnett PG, Fan A, Harden C, King SS, Scott JY. Research guide to decision support system national cost extracts. Health Economics Resource Center of Health Service R&D Services, US Department of Veterans Affairs. September 2010. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.herc.research.va.gov/files/book_621.pdf

16. Agusti A, Hedner J, Marin JM, Barbé F, Cazzola M, Rennard S. Night-time symptoms: a forgotten dimension of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20(121):183-194. doi:10.1183/09059180.00004311

17. Croxton TL, Bailey WC. Long-term oxygen treatment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: recommendations for future research: an NHLBI workshop report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(4):373-378. doi:10.1164/rccm.200507-1161WS

18. Melani AS, Sestini P, Rottoli P. Home oxygen therapy: re-thinking the role of devices. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11(3):279-289. doi:10.1080/17512433.2018.1421457

19. Sculley JA, Corbridge SJ, Prieto-Centurion V, et al. Home oxygen therapy for patients with COPD: time for a reboot. Respir Care. 2019;64(12):1574-1585. doi:10.4187/respcare.07135

20. Jacobs SS, Lindell KO, Collins EG, et al. Patient perceptions of the adequacy of supplemental oxygen therapy. Results of the American Thoracic Society Nursing Assembly Oxygen Working Group Survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:24-32. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-209OC

21. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Home use of oxygen. Publication number 100-3. January 3, 2023. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=169

The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among male US veterans is higher than in the general population.1 Veterans with COPD have higher rates of comorbidities and increased respiratory-related and all-cause health care use, including the use of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT).2-5 It has been well established that LTOT reduces all-cause mortality in patients with COPD and

Delivery of domiciliary LTOT entails placing a nasal cannula into both nostrils and loosely securing it around both ears throughout the wake-sleep cycle. Several veterans with hypoxemic CRF due to COPD at the Jesse Brown Veterans Affairs Medical Center (JBVAMC) in Chicago, Illinois, who were receiving LTOT reported nasal cannula dislodgement (NCD) while they slept. However, the clinical significance and impact of these repeated episodes on respiratory-related health care utilization, such as frequent COPD exacerbations with hospitalization, were not recognized.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether veterans with hypoxemic CRF due to COPD and receiving 24-hour LTOT at JBVAMC were experiencing NCD during sleep and, if so, its impact on

METHODS

We reviewed electronic health records (EHRs) of veterans with hypoxemic CRF from COPD who received 24-hour LTOT administered through nasal cannula and were followed

Pertinent patient demographics, clinical and physiologic variables, and hospitalizations with length of JBVAMC stay for each physician-diagnosed COPD exacerbation in the preceding year from the date last seen in the clinic were abstracted from EHRs. Overall hospital cost, defined as a veteran overnight stay in either the medical intensive care unit (MICU) or a general acute medicine bed in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facility, was calculated for each hospitalization for physician-diagnosed COPD exacerbation using VA Managerial Cost Accounting System National Cost Extracts for inpatient encounters.15 We then contacted each veteran by telephone and asked whether they had experienced NCD and, if so, its weekly frequency ranging from once to nightly.

Data Analysis

Data were reported as mean (SD) where appropriate. The t test and Fisher exact test were used as indicated. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The study protocol

RESULTS

During the study period,

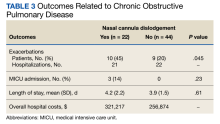

Of the 75 patients, 66 (88%) responded to the telephone survey and 22 patients (33%) reported weekly episodes of NCD while they slept (median, 4 dislodgments per week). (Table 1). Eight patients (36%) reported nightly NCDs (Figure). All 66 respondents were male and 14 of 22 in the NCD group as well as 21 of 44 in the no NCD group were Black veterans. The mean age was similar in both groups: 71 years in the NCD group and 72 years in the no NCD group. There were no statistically significant differences in demographics, including prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), supplemental oxygen flow rate, and duration of LTOT, or in pulmonary function test results between patients who did and did not experience NCD while sleeping (Table 2).

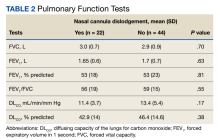

Ten of 22 patients (45%) with NCD and 9 of 44 patients (20%) without NCD were hospitalized at the JBVAMC for ≥ 1 COPD exacerbation in the preceding year that was diagnosed by a physician (P = .045). Three of 22 patients (14%) with NCD and no patients in the no NCD group were admitted to the MICU. No patients required intubation and mechanical ventilation during hospitalization, and no patients died. Overall hospital costs were 25% ($64,342) higher in NCD group compared with the no NCD group and were attributed to the MICU admissions in the NCD group (Table 3). Nine veterans did not respond to repeated telephone calls. One physician-diagnosed COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization was documented in the nonresponder group; the patient was hospitalized for 2 days. One veteran died before being contacted.

DISCUSSION

There are 3 new findings in this study.

Nocturnal arterial oxygen desaturation in patients with COPD without evidence of OSA may contribute to the frequency of exacerbations.16 Although the mechanism(s) underlying this phenomenon is uncertain, we posit that prolonged nocturnal airway wall hypoxia could amplify underlying chronic inflammation through local generation of reactive oxygen species, thereby predisposing patients to exacerbations. Frequent COPD exacerbations promote disease progression and health status decline and are associated with increased mortality.11,13 Moreover, hospitalization of patients with COPD is the largest contributor to the annual direct cost of COPD per patient.10,12 The higher hospitalization rate observed in the NCD group in our study suggests that interruption of supplemental oxygen delivery while asleep may be a risk factor for COPD exacerbation. Alternatively, an independent factor or factors may have contributed to both NCD during sleep and COPD exacerbation in these patients or an impending exacerbation resulted in sleep disturbances that led to NCD. Additional research is warranted on veterans with hypoxemic CRF from COPD who are receiving LTOT and report frequent NCD during sleep that may support or refute these hypotheses.

To the best of our knowledge, NCD during sleep has not been previously reported in patients

Limitations

This was a small, single-site study, comprised entirely of male patients who are predominantly Black veterans. The telephone interviews with veterans self-reporting NCD during their sleep are prone to recall bias. In addition, the validity and reproducibility of NCD during sleep were not addressed in this study. Missing data from 9 nonresponders may have introduced a nonresponse bias in data analysis and interpretation. The overall hospital cost for a COPD exacerbation at JBVAMC was derived from VA data; US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services or commercial carrier data may be different.15,21 Lastly, access to LTOT for veterans with hypoxemic CRF from COPD is regulated and supervised at VA medical facilities.14 This process may be different for patients outside the VA. Taken together, it is difficult to generalize our initial observations to non-VA patients with hypoxemic CRF from COPD who are receiving LTOT. We suggest a large, prospective study of veterans be conducted to determine the prevalence of NCD during sleep and its relationship with COPD exacerbations in veterans receiving LTOT with hypoxemic CRF due to COPD.

CONCLUSIONS

Acknowledgments

We thank Yolanda Davis, RRT, and George Adam for their assistance with this project.

The prevalence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) among male US veterans is higher than in the general population.1 Veterans with COPD have higher rates of comorbidities and increased respiratory-related and all-cause health care use, including the use of long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT).2-5 It has been well established that LTOT reduces all-cause mortality in patients with COPD and

Delivery of domiciliary LTOT entails placing a nasal cannula into both nostrils and loosely securing it around both ears throughout the wake-sleep cycle. Several veterans with hypoxemic CRF due to COPD at the Jesse Brown Veterans Affairs Medical Center (JBVAMC) in Chicago, Illinois, who were receiving LTOT reported nasal cannula dislodgement (NCD) while they slept. However, the clinical significance and impact of these repeated episodes on respiratory-related health care utilization, such as frequent COPD exacerbations with hospitalization, were not recognized.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether veterans with hypoxemic CRF due to COPD and receiving 24-hour LTOT at JBVAMC were experiencing NCD during sleep and, if so, its impact on

METHODS

We reviewed electronic health records (EHRs) of veterans with hypoxemic CRF from COPD who received 24-hour LTOT administered through nasal cannula and were followed

Pertinent patient demographics, clinical and physiologic variables, and hospitalizations with length of JBVAMC stay for each physician-diagnosed COPD exacerbation in the preceding year from the date last seen in the clinic were abstracted from EHRs. Overall hospital cost, defined as a veteran overnight stay in either the medical intensive care unit (MICU) or a general acute medicine bed in a US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) facility, was calculated for each hospitalization for physician-diagnosed COPD exacerbation using VA Managerial Cost Accounting System National Cost Extracts for inpatient encounters.15 We then contacted each veteran by telephone and asked whether they had experienced NCD and, if so, its weekly frequency ranging from once to nightly.

Data Analysis

Data were reported as mean (SD) where appropriate. The t test and Fisher exact test were used as indicated. P < .05 was considered statistically significant. The study protocol

RESULTS

During the study period,

Of the 75 patients, 66 (88%) responded to the telephone survey and 22 patients (33%) reported weekly episodes of NCD while they slept (median, 4 dislodgments per week). (Table 1). Eight patients (36%) reported nightly NCDs (Figure). All 66 respondents were male and 14 of 22 in the NCD group as well as 21 of 44 in the no NCD group were Black veterans. The mean age was similar in both groups: 71 years in the NCD group and 72 years in the no NCD group. There were no statistically significant differences in demographics, including prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), supplemental oxygen flow rate, and duration of LTOT, or in pulmonary function test results between patients who did and did not experience NCD while sleeping (Table 2).

Ten of 22 patients (45%) with NCD and 9 of 44 patients (20%) without NCD were hospitalized at the JBVAMC for ≥ 1 COPD exacerbation in the preceding year that was diagnosed by a physician (P = .045). Three of 22 patients (14%) with NCD and no patients in the no NCD group were admitted to the MICU. No patients required intubation and mechanical ventilation during hospitalization, and no patients died. Overall hospital costs were 25% ($64,342) higher in NCD group compared with the no NCD group and were attributed to the MICU admissions in the NCD group (Table 3). Nine veterans did not respond to repeated telephone calls. One physician-diagnosed COPD exacerbation requiring hospitalization was documented in the nonresponder group; the patient was hospitalized for 2 days. One veteran died before being contacted.

DISCUSSION

There are 3 new findings in this study.

Nocturnal arterial oxygen desaturation in patients with COPD without evidence of OSA may contribute to the frequency of exacerbations.16 Although the mechanism(s) underlying this phenomenon is uncertain, we posit that prolonged nocturnal airway wall hypoxia could amplify underlying chronic inflammation through local generation of reactive oxygen species, thereby predisposing patients to exacerbations. Frequent COPD exacerbations promote disease progression and health status decline and are associated with increased mortality.11,13 Moreover, hospitalization of patients with COPD is the largest contributor to the annual direct cost of COPD per patient.10,12 The higher hospitalization rate observed in the NCD group in our study suggests that interruption of supplemental oxygen delivery while asleep may be a risk factor for COPD exacerbation. Alternatively, an independent factor or factors may have contributed to both NCD during sleep and COPD exacerbation in these patients or an impending exacerbation resulted in sleep disturbances that led to NCD. Additional research is warranted on veterans with hypoxemic CRF from COPD who are receiving LTOT and report frequent NCD during sleep that may support or refute these hypotheses.

To the best of our knowledge, NCD during sleep has not been previously reported in patients

Limitations

This was a small, single-site study, comprised entirely of male patients who are predominantly Black veterans. The telephone interviews with veterans self-reporting NCD during their sleep are prone to recall bias. In addition, the validity and reproducibility of NCD during sleep were not addressed in this study. Missing data from 9 nonresponders may have introduced a nonresponse bias in data analysis and interpretation. The overall hospital cost for a COPD exacerbation at JBVAMC was derived from VA data; US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services or commercial carrier data may be different.15,21 Lastly, access to LTOT for veterans with hypoxemic CRF from COPD is regulated and supervised at VA medical facilities.14 This process may be different for patients outside the VA. Taken together, it is difficult to generalize our initial observations to non-VA patients with hypoxemic CRF from COPD who are receiving LTOT. We suggest a large, prospective study of veterans be conducted to determine the prevalence of NCD during sleep and its relationship with COPD exacerbations in veterans receiving LTOT with hypoxemic CRF due to COPD.

CONCLUSIONS

Acknowledgments

We thank Yolanda Davis, RRT, and George Adam for their assistance with this project.

1. Boersma P, Cohen RA, Zelaya CE, Moy E. Multiple chronic conditions among veterans and nonveterans: United States, 2015-2018. Natl Health Stat Report. 2021;(153):1-13. doi:10.15620/cdc:101659

2. Sharafkhaneh A, Petersen NJ, Yu H-J, Dalal AA, Johnson ML, Hanania NA. Burden of COPD in a government health care system: a retrospective observational study using data from the US Veterans Affairs population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:125-132. doi:10.2147/copd.s8047

3. LaBedz SL, Krishnan JA, Chung Y-C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease outcomes at Veterans Affairs versus non-Veterans Affairs hospitals. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2021;8(3):306-313. doi:10.15326/jcopdf.2021.0201

4. Darnell K, Dwivedi AK, Weng Z, Panos RJ. Disproportionate utilization of healthcare resources among veterans with COPD: a retrospective analysis of factors associated with COPD healthcare cost. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2013;11:13. doi:10.1186/1478-7547-11-13

5. Bamonti PM, Robinson SA, Wan ES, Moy ML. Improving physiological, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a narrative review in US Veterans with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

6. Cranston JM, Crockett AJ, Moss JR, Alpers JH. Domiciliary oxygen for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2005(4):CD001744. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001744.pub2

7. Lacasse Y, Tan AM, Maltais F, Krishnan JA. Home oxygen in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(10):1254-1264. doi:10.1164/rccm.201802-0382CI

8. Jacobs SS, Krishnan JA, Lederer DJ, et al. Home oxygen therapy for adults with chronic lung disease. An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(10):e121-e141. doi:10.1164/rccm.202009-3608ST

9. AARC. AARC clinical practice guideline. Oxygen therapy in the home or alternate site health care facility--2007 revision & update. Respir Care. 2007;52(8):1063-1068.

10. Foo J, Landis SH, Maskell J, et al. Continuing to confront COPD international patient survey: economic impact of COPD in 12 countries. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152618. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152618

11. Rothnie KJ, Müllerová H, Smeeth L, Quint JK. Natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in a general practice-based population with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(4):464-471. doi:10.1164/rccm.201710-2029OC

12. Stanford RH, Engel-Nitz NM, Bancroft T, Essoi B. The identification and cost of acute chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in a United States population healthcare claims database. COPD. 2020;17(5):499-508. doi:10.1080/15412555.2020.1817357

13. Hurst JR, Han MK, Singh B, et al. Prognostic risk factors for moderate-to-severe exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic literature review. Respir Res. 2022;23(1):213. doi:10.1186/s12931-022-02123-5

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Home oxygen program. VHA Directive 1173.13(1). Published August 5, 2020. Accessed February 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=8947

15. Phibbs CS, Barnett PG, Fan A, Harden C, King SS, Scott JY. Research guide to decision support system national cost extracts. Health Economics Resource Center of Health Service R&D Services, US Department of Veterans Affairs. September 2010. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.herc.research.va.gov/files/book_621.pdf

16. Agusti A, Hedner J, Marin JM, Barbé F, Cazzola M, Rennard S. Night-time symptoms: a forgotten dimension of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20(121):183-194. doi:10.1183/09059180.00004311

17. Croxton TL, Bailey WC. Long-term oxygen treatment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: recommendations for future research: an NHLBI workshop report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(4):373-378. doi:10.1164/rccm.200507-1161WS

18. Melani AS, Sestini P, Rottoli P. Home oxygen therapy: re-thinking the role of devices. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11(3):279-289. doi:10.1080/17512433.2018.1421457

19. Sculley JA, Corbridge SJ, Prieto-Centurion V, et al. Home oxygen therapy for patients with COPD: time for a reboot. Respir Care. 2019;64(12):1574-1585. doi:10.4187/respcare.07135

20. Jacobs SS, Lindell KO, Collins EG, et al. Patient perceptions of the adequacy of supplemental oxygen therapy. Results of the American Thoracic Society Nursing Assembly Oxygen Working Group Survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:24-32. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-209OC

21. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Home use of oxygen. Publication number 100-3. January 3, 2023. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=169

1. Boersma P, Cohen RA, Zelaya CE, Moy E. Multiple chronic conditions among veterans and nonveterans: United States, 2015-2018. Natl Health Stat Report. 2021;(153):1-13. doi:10.15620/cdc:101659

2. Sharafkhaneh A, Petersen NJ, Yu H-J, Dalal AA, Johnson ML, Hanania NA. Burden of COPD in a government health care system: a retrospective observational study using data from the US Veterans Affairs population. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:125-132. doi:10.2147/copd.s8047

3. LaBedz SL, Krishnan JA, Chung Y-C, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease outcomes at Veterans Affairs versus non-Veterans Affairs hospitals. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis. 2021;8(3):306-313. doi:10.15326/jcopdf.2021.0201

4. Darnell K, Dwivedi AK, Weng Z, Panos RJ. Disproportionate utilization of healthcare resources among veterans with COPD: a retrospective analysis of factors associated with COPD healthcare cost. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2013;11:13. doi:10.1186/1478-7547-11-13

5. Bamonti PM, Robinson SA, Wan ES, Moy ML. Improving physiological, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a narrative review in US Veterans with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2022;17:1269-1283. doi:10.2147/COPD.S339323

6. Cranston JM, Crockett AJ, Moss JR, Alpers JH. Domiciliary oxygen for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2005(4):CD001744. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001744.pub2

7. Lacasse Y, Tan AM, Maltais F, Krishnan JA. Home oxygen in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(10):1254-1264. doi:10.1164/rccm.201802-0382CI

8. Jacobs SS, Krishnan JA, Lederer DJ, et al. Home oxygen therapy for adults with chronic lung disease. An official American Thoracic Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(10):e121-e141. doi:10.1164/rccm.202009-3608ST

9. AARC. AARC clinical practice guideline. Oxygen therapy in the home or alternate site health care facility--2007 revision & update. Respir Care. 2007;52(8):1063-1068.

10. Foo J, Landis SH, Maskell J, et al. Continuing to confront COPD international patient survey: economic impact of COPD in 12 countries. PLoS One. 2016;11(4):e0152618. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152618

11. Rothnie KJ, Müllerová H, Smeeth L, Quint JK. Natural history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in a general practice-based population with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198(4):464-471. doi:10.1164/rccm.201710-2029OC

12. Stanford RH, Engel-Nitz NM, Bancroft T, Essoi B. The identification and cost of acute chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations in a United States population healthcare claims database. COPD. 2020;17(5):499-508. doi:10.1080/15412555.2020.1817357

13. Hurst JR, Han MK, Singh B, et al. Prognostic risk factors for moderate-to-severe exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic literature review. Respir Res. 2022;23(1):213. doi:10.1186/s12931-022-02123-5

14. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration. Home oxygen program. VHA Directive 1173.13(1). Published August 5, 2020. Accessed February 28, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=8947

15. Phibbs CS, Barnett PG, Fan A, Harden C, King SS, Scott JY. Research guide to decision support system national cost extracts. Health Economics Resource Center of Health Service R&D Services, US Department of Veterans Affairs. September 2010. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.herc.research.va.gov/files/book_621.pdf

16. Agusti A, Hedner J, Marin JM, Barbé F, Cazzola M, Rennard S. Night-time symptoms: a forgotten dimension of COPD. Eur Respir Rev. 2011;20(121):183-194. doi:10.1183/09059180.00004311

17. Croxton TL, Bailey WC. Long-term oxygen treatment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: recommendations for future research: an NHLBI workshop report. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(4):373-378. doi:10.1164/rccm.200507-1161WS

18. Melani AS, Sestini P, Rottoli P. Home oxygen therapy: re-thinking the role of devices. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2018;11(3):279-289. doi:10.1080/17512433.2018.1421457

19. Sculley JA, Corbridge SJ, Prieto-Centurion V, et al. Home oxygen therapy for patients with COPD: time for a reboot. Respir Care. 2019;64(12):1574-1585. doi:10.4187/respcare.07135

20. Jacobs SS, Lindell KO, Collins EG, et al. Patient perceptions of the adequacy of supplemental oxygen therapy. Results of the American Thoracic Society Nursing Assembly Oxygen Working Group Survey. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15:24-32. doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201703-209OC

21. US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Home use of oxygen. Publication number 100-3. January 3, 2023. Accessed February 14, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/ncd.aspx?NCDId=169