User login

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

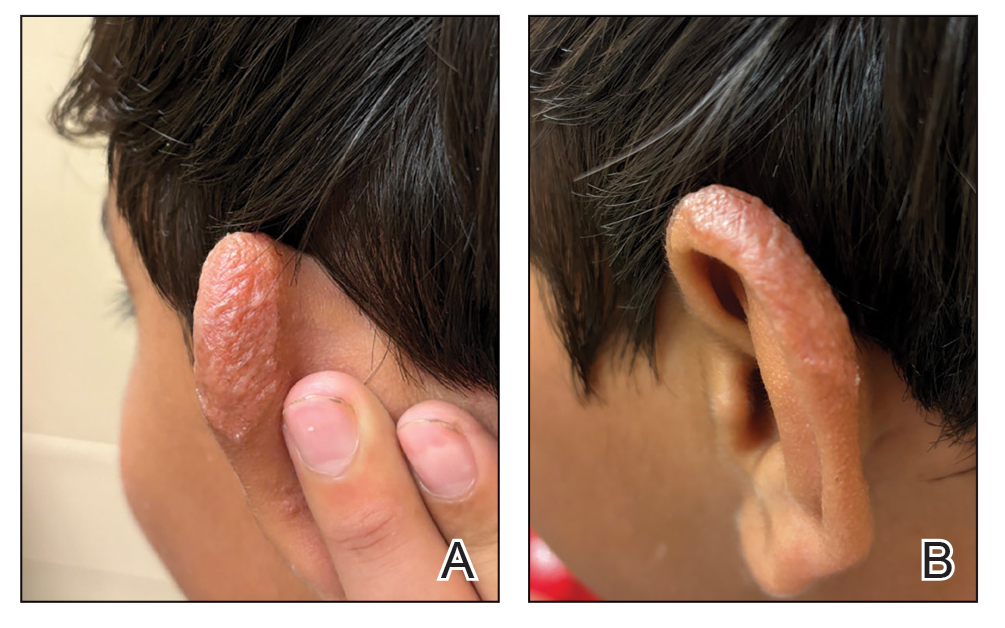

The biopsy results demonstrated a nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, including few multinucleated histiocytes, a surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate, mostly mature lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and fragmented neutrophils. A special stain panel was negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff for fungi. Bacterial cultures from biopsy tissue grew normal skin flora, and both fungal and AFB cultures were negative. A second punch biopsy was recommended by infectious disease due to clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Histopathology showed nonnecrotizing granulomas with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and negative Giemsa staining for Leishmania amastigotes; however, it was concluded by pathology that the reason for the negative Leishmania staining was the late stage of the disease, indicated by the presence of granulomas, which can make visualization of organisms difficult. Nonetheless, universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was positive for Leishmania tropica. Thus, although microscopic analysis was negative for visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, molecular analysis via PCR ultimately demonstrated a positive result and confirmed the diagnosis of CL (Figure 1). The variance in diagnostic accuracy exemplified in our case reinforces the need for multimodal diagnosis.

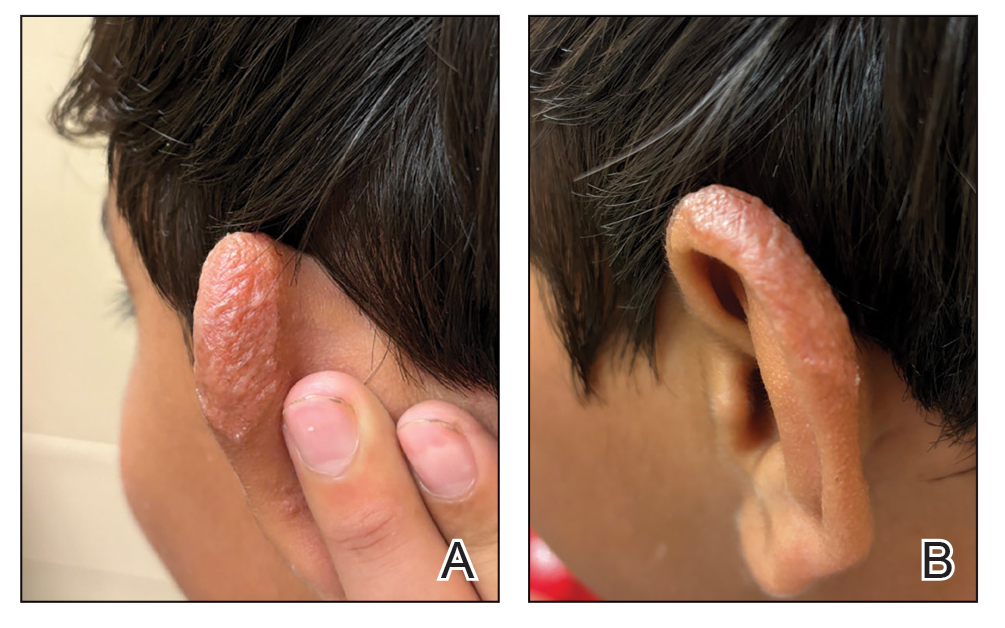

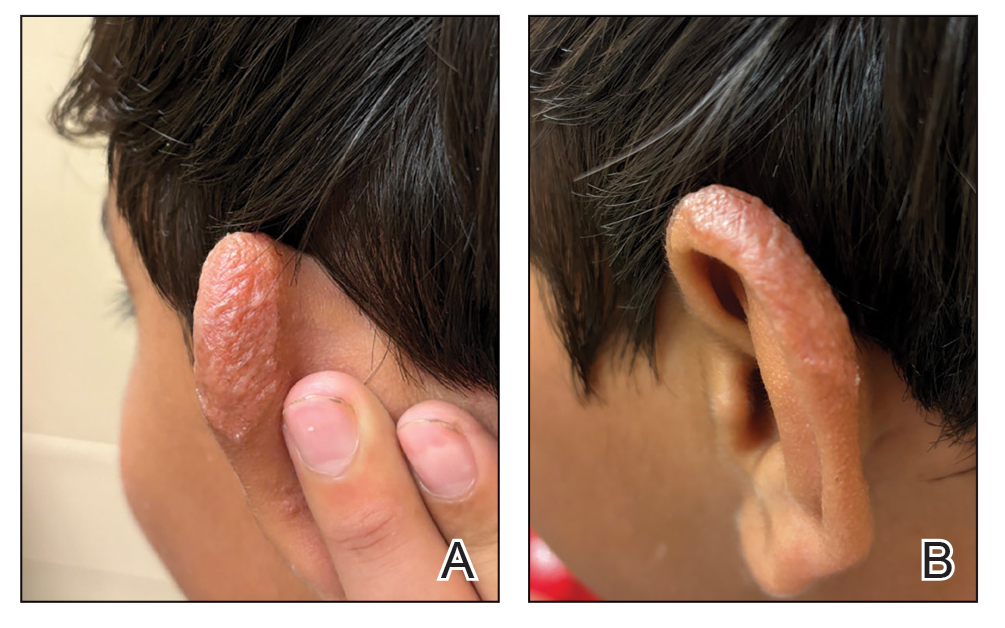

Multiple factors needed to be considered with regard to treatment in our patient, including but not limited to the location of the lesion on a slow-healing cartilaginous surface and the patient’s age. Considering the recalcitrant nature of the lesion and the L tropica strain exhibiting resistance to topical treatments, systemic therapies were the only option. Furthermore, parenteral routes of administration were confounded by the patient’s age, decreasing the likelihood of compliance with therapy. With these variables in mind and recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the best treatment for our patient was deemed to be a 28-day course of oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily. Compared to the initial presentation, a 1-month follow-up visit after completing the 28-day course of treatment demonstrated flattening of the lesion (Figure 2).

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by a protozoan parasite of the Leishmania genus, spread via inoculation from the bite of sandfly vectors.1 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common clinical manifestation of leishmaniasis. Other clinical manifestations include mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis.1,2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis typically manifests as open wounds on areas of skin that may have been exposed to sandfly bites.3 The lesion may not appear until weeks to months or even years after the initial inoculation.2 Initially, CL manifests as papules that may progress to nodular plaques, with eventual evolution to volcanic ulcerations with raised borders and central crateriform indentations covered by scabs or crusting.2,3 The infection may be localized or diffuse—in either case, development of satellite lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and/or nodular lymphangitis is not uncommon. Generally, CL is not lethal, but the severity of the lesions may vary and can lead to permanent scarring and atrophy.2 Many cases of CL remain undiagnosed because of its appearance as a nonspecific ulcer that can mimic many other cutaneous lesions and because it generally heals spontaneously, leaving only scarring as an indicator of prior infection.4 Thus, CL requires a high diagnostic suspicion, as it can have a nonspecific presentation and is rare in nonendemic regions.

Diagnosis of CL is accomplished via microscopy, isoenzyme analysis, or serology or is made molecularly.3 Microscopic diagnosis includes visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, the stage of replication that occurs after the promastigote stage is phagocytosed by macrophages.3 Amastigote is the only stage that can be visualized in human tissue and is stained via Giemsa and/or hematoxylin and eosin.3 However, Leishmania amastigotes are morphologically indistinguishable from Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes on microscopy, thus limiting diagnostic accuracy.3 Moreover, there is potential for missed diagnosis of persistent CL caused by L tropica due to fewer parasites being present, further complicating the diagnosis.5 In these cases, molecular diagnostics are helpful as they have higher sensitivity and quicker results. Additionally, DNA technologies can differentiate strains, which is beneficial for guiding treatment. Isoenzyme analysis also can help identify Leishmania species, although results can take weeks to return.3 Serologic testing is useful for suspected visceral leishmaniasis despite negative definitive diagnoses or conflicts with conducting definitive studies; however, there is not a strong antibody response in CL, thus serology is ineffective.3,5 Furthermore, serology can have cross-reactivity with T cruzi and cannot be used to assess for treatment response.3,5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis of leishmaniasis recommend using multiple methods to ensure a positive result, with molecular assays being the most sensitive.5

Differential diagnoses include any cause of cutaneous ulcerated lesions, including but not limited to mycobacterial or fungal infections. Leprosy often initially manifests with a hypopigmented macule with a raised border, although there often are associated neuropathic symptoms.6 Cutaneous tuberculosis is an extremely rare manifestation that occurs via direct inoculation of the mycobacterium, occurring primarily in children. Initially, it may manifest as a firm red papule that progresses to a painless shallow ulcer with a granular base.7 Cutaneous chromoblastomycosis is a fungal infection resulting from an initial cutaneous injury, similar to our patient, followed by a slow-developing warty lesion that may heal into ivory scars or spread as plaques on normal skin.8 The verrucous lesions seen in cutaneous chromoblastomycosis tend to manifest on the lower extremities and are unlikely to manifest on the head. Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous skin eruption that can be clinically nonspecific.9 Histologically, lesions may demonstrate noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, as seen with cutaneous leishmaniasis, with a broad presentation; for example, lupus pernio, a sarcoid variant, manifests as large blue-red dusky nodules/plaques on the face, ears, or digits.9 Other sarcoid lesions include red/brown, thickened, circular plaques; variably discolored papulonodular lesions; or mucosal involvement.9 Ultimately, it is important to differentiate these nonspecific and similarly appearing lesions through diagnostic techniques such as AFB culture and smear, fungal staining, tuberculosis testing, and PCR in more challenging cases.

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis should be individualized to each case.5 A more than 50% reduction in lesion size within 4 to 6 weeks indicates successful treatment. Ulcerated lesions should be fully re-epithelialized and healed by 3 months posttreatment. Treatment failure is categorized by failure of reepithelization, incomplete healing by 3 months, or worsening of the lesion at any time, each necessitating additional treatment, such as a second course of miltefosine or a different medication regimen.5 Careful monitoring is required throughout treatment, assessing for treatment failure, adding to the challenges of leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, CL requires a high index of suspicion in nonendemic areas to ensure successful diagnosis and treatment. Our case highlights the importance of using multimodal diagnostic techniques for CL, as a single modality may not exhibit a positive result due to variations in diagnostic accuracy. Our case also exhibits the complex treatment of CL, and the considerations that should be made when choosing a treatment modality.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Clinical overview of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/leishmaniasis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- CDC DPDx Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

- Stark CG. Leishmaniasis differential diagnoses. Medscape. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/220298-differential

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:E202-E264. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw670

- Lewis FS. Dermatologic manifestations of leprosy. Medscape. June 19, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104977-overview

- Ngan V. Cutaneous tuberculosis. DermNet. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis

- Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis. Medscape. May 13, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-overview#a4

- Elyoussfi S, Coulson I. Sarcoidosis. DermNet. May 31, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sarcoidosis

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results demonstrated a nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, including few multinucleated histiocytes, a surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate, mostly mature lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and fragmented neutrophils. A special stain panel was negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff for fungi. Bacterial cultures from biopsy tissue grew normal skin flora, and both fungal and AFB cultures were negative. A second punch biopsy was recommended by infectious disease due to clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Histopathology showed nonnecrotizing granulomas with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and negative Giemsa staining for Leishmania amastigotes; however, it was concluded by pathology that the reason for the negative Leishmania staining was the late stage of the disease, indicated by the presence of granulomas, which can make visualization of organisms difficult. Nonetheless, universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was positive for Leishmania tropica. Thus, although microscopic analysis was negative for visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, molecular analysis via PCR ultimately demonstrated a positive result and confirmed the diagnosis of CL (Figure 1). The variance in diagnostic accuracy exemplified in our case reinforces the need for multimodal diagnosis.

Multiple factors needed to be considered with regard to treatment in our patient, including but not limited to the location of the lesion on a slow-healing cartilaginous surface and the patient’s age. Considering the recalcitrant nature of the lesion and the L tropica strain exhibiting resistance to topical treatments, systemic therapies were the only option. Furthermore, parenteral routes of administration were confounded by the patient’s age, decreasing the likelihood of compliance with therapy. With these variables in mind and recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the best treatment for our patient was deemed to be a 28-day course of oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily. Compared to the initial presentation, a 1-month follow-up visit after completing the 28-day course of treatment demonstrated flattening of the lesion (Figure 2).

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by a protozoan parasite of the Leishmania genus, spread via inoculation from the bite of sandfly vectors.1 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common clinical manifestation of leishmaniasis. Other clinical manifestations include mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis.1,2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis typically manifests as open wounds on areas of skin that may have been exposed to sandfly bites.3 The lesion may not appear until weeks to months or even years after the initial inoculation.2 Initially, CL manifests as papules that may progress to nodular plaques, with eventual evolution to volcanic ulcerations with raised borders and central crateriform indentations covered by scabs or crusting.2,3 The infection may be localized or diffuse—in either case, development of satellite lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and/or nodular lymphangitis is not uncommon. Generally, CL is not lethal, but the severity of the lesions may vary and can lead to permanent scarring and atrophy.2 Many cases of CL remain undiagnosed because of its appearance as a nonspecific ulcer that can mimic many other cutaneous lesions and because it generally heals spontaneously, leaving only scarring as an indicator of prior infection.4 Thus, CL requires a high diagnostic suspicion, as it can have a nonspecific presentation and is rare in nonendemic regions.

Diagnosis of CL is accomplished via microscopy, isoenzyme analysis, or serology or is made molecularly.3 Microscopic diagnosis includes visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, the stage of replication that occurs after the promastigote stage is phagocytosed by macrophages.3 Amastigote is the only stage that can be visualized in human tissue and is stained via Giemsa and/or hematoxylin and eosin.3 However, Leishmania amastigotes are morphologically indistinguishable from Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes on microscopy, thus limiting diagnostic accuracy.3 Moreover, there is potential for missed diagnosis of persistent CL caused by L tropica due to fewer parasites being present, further complicating the diagnosis.5 In these cases, molecular diagnostics are helpful as they have higher sensitivity and quicker results. Additionally, DNA technologies can differentiate strains, which is beneficial for guiding treatment. Isoenzyme analysis also can help identify Leishmania species, although results can take weeks to return.3 Serologic testing is useful for suspected visceral leishmaniasis despite negative definitive diagnoses or conflicts with conducting definitive studies; however, there is not a strong antibody response in CL, thus serology is ineffective.3,5 Furthermore, serology can have cross-reactivity with T cruzi and cannot be used to assess for treatment response.3,5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis of leishmaniasis recommend using multiple methods to ensure a positive result, with molecular assays being the most sensitive.5

Differential diagnoses include any cause of cutaneous ulcerated lesions, including but not limited to mycobacterial or fungal infections. Leprosy often initially manifests with a hypopigmented macule with a raised border, although there often are associated neuropathic symptoms.6 Cutaneous tuberculosis is an extremely rare manifestation that occurs via direct inoculation of the mycobacterium, occurring primarily in children. Initially, it may manifest as a firm red papule that progresses to a painless shallow ulcer with a granular base.7 Cutaneous chromoblastomycosis is a fungal infection resulting from an initial cutaneous injury, similar to our patient, followed by a slow-developing warty lesion that may heal into ivory scars or spread as plaques on normal skin.8 The verrucous lesions seen in cutaneous chromoblastomycosis tend to manifest on the lower extremities and are unlikely to manifest on the head. Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous skin eruption that can be clinically nonspecific.9 Histologically, lesions may demonstrate noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, as seen with cutaneous leishmaniasis, with a broad presentation; for example, lupus pernio, a sarcoid variant, manifests as large blue-red dusky nodules/plaques on the face, ears, or digits.9 Other sarcoid lesions include red/brown, thickened, circular plaques; variably discolored papulonodular lesions; or mucosal involvement.9 Ultimately, it is important to differentiate these nonspecific and similarly appearing lesions through diagnostic techniques such as AFB culture and smear, fungal staining, tuberculosis testing, and PCR in more challenging cases.

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis should be individualized to each case.5 A more than 50% reduction in lesion size within 4 to 6 weeks indicates successful treatment. Ulcerated lesions should be fully re-epithelialized and healed by 3 months posttreatment. Treatment failure is categorized by failure of reepithelization, incomplete healing by 3 months, or worsening of the lesion at any time, each necessitating additional treatment, such as a second course of miltefosine or a different medication regimen.5 Careful monitoring is required throughout treatment, assessing for treatment failure, adding to the challenges of leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, CL requires a high index of suspicion in nonendemic areas to ensure successful diagnosis and treatment. Our case highlights the importance of using multimodal diagnostic techniques for CL, as a single modality may not exhibit a positive result due to variations in diagnostic accuracy. Our case also exhibits the complex treatment of CL, and the considerations that should be made when choosing a treatment modality.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Leishmaniasis

The biopsy results demonstrated a nonspecific chronic granulomatous inflammatory infiltrate, including few multinucleated histiocytes, a surrounding mixed inflammatory infiltrate, mostly mature lymphocytes, few plasma cells, and fragmented neutrophils. A special stain panel was negative for acid-fast bacilli (AFB), Fite, and periodic acid–Schiff for fungi. Bacterial cultures from biopsy tissue grew normal skin flora, and both fungal and AFB cultures were negative. A second punch biopsy was recommended by infectious disease due to clinical suspicion of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL). Histopathology showed nonnecrotizing granulomas with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation and negative Giemsa staining for Leishmania amastigotes; however, it was concluded by pathology that the reason for the negative Leishmania staining was the late stage of the disease, indicated by the presence of granulomas, which can make visualization of organisms difficult. Nonetheless, universal polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing was positive for Leishmania tropica. Thus, although microscopic analysis was negative for visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, molecular analysis via PCR ultimately demonstrated a positive result and confirmed the diagnosis of CL (Figure 1). The variance in diagnostic accuracy exemplified in our case reinforces the need for multimodal diagnosis.

Multiple factors needed to be considered with regard to treatment in our patient, including but not limited to the location of the lesion on a slow-healing cartilaginous surface and the patient’s age. Considering the recalcitrant nature of the lesion and the L tropica strain exhibiting resistance to topical treatments, systemic therapies were the only option. Furthermore, parenteral routes of administration were confounded by the patient’s age, decreasing the likelihood of compliance with therapy. With these variables in mind and recommendations from the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the best treatment for our patient was deemed to be a 28-day course of oral miltefosine 50 mg twice daily. Compared to the initial presentation, a 1-month follow-up visit after completing the 28-day course of treatment demonstrated flattening of the lesion (Figure 2).

Leishmaniasis is a disease caused by a protozoan parasite of the Leishmania genus, spread via inoculation from the bite of sandfly vectors.1 Cutaneous leishmaniasis is the most common clinical manifestation of leishmaniasis. Other clinical manifestations include mucocutaneous leishmaniasis and visceral leishmaniasis.1,2 Cutaneous leishmaniasis typically manifests as open wounds on areas of skin that may have been exposed to sandfly bites.3 The lesion may not appear until weeks to months or even years after the initial inoculation.2 Initially, CL manifests as papules that may progress to nodular plaques, with eventual evolution to volcanic ulcerations with raised borders and central crateriform indentations covered by scabs or crusting.2,3 The infection may be localized or diffuse—in either case, development of satellite lesions, regional lymphadenopathy, and/or nodular lymphangitis is not uncommon. Generally, CL is not lethal, but the severity of the lesions may vary and can lead to permanent scarring and atrophy.2 Many cases of CL remain undiagnosed because of its appearance as a nonspecific ulcer that can mimic many other cutaneous lesions and because it generally heals spontaneously, leaving only scarring as an indicator of prior infection.4 Thus, CL requires a high diagnostic suspicion, as it can have a nonspecific presentation and is rare in nonendemic regions.

Diagnosis of CL is accomplished via microscopy, isoenzyme analysis, or serology or is made molecularly.3 Microscopic diagnosis includes visualization of Leishmania amastigotes, the stage of replication that occurs after the promastigote stage is phagocytosed by macrophages.3 Amastigote is the only stage that can be visualized in human tissue and is stained via Giemsa and/or hematoxylin and eosin.3 However, Leishmania amastigotes are morphologically indistinguishable from Trypanosoma cruzi amastigotes on microscopy, thus limiting diagnostic accuracy.3 Moreover, there is potential for missed diagnosis of persistent CL caused by L tropica due to fewer parasites being present, further complicating the diagnosis.5 In these cases, molecular diagnostics are helpful as they have higher sensitivity and quicker results. Additionally, DNA technologies can differentiate strains, which is beneficial for guiding treatment. Isoenzyme analysis also can help identify Leishmania species, although results can take weeks to return.3 Serologic testing is useful for suspected visceral leishmaniasis despite negative definitive diagnoses or conflicts with conducting definitive studies; however, there is not a strong antibody response in CL, thus serology is ineffective.3,5 Furthermore, serology can have cross-reactivity with T cruzi and cannot be used to assess for treatment response.3,5 The Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for diagnosis of leishmaniasis recommend using multiple methods to ensure a positive result, with molecular assays being the most sensitive.5

Differential diagnoses include any cause of cutaneous ulcerated lesions, including but not limited to mycobacterial or fungal infections. Leprosy often initially manifests with a hypopigmented macule with a raised border, although there often are associated neuropathic symptoms.6 Cutaneous tuberculosis is an extremely rare manifestation that occurs via direct inoculation of the mycobacterium, occurring primarily in children. Initially, it may manifest as a firm red papule that progresses to a painless shallow ulcer with a granular base.7 Cutaneous chromoblastomycosis is a fungal infection resulting from an initial cutaneous injury, similar to our patient, followed by a slow-developing warty lesion that may heal into ivory scars or spread as plaques on normal skin.8 The verrucous lesions seen in cutaneous chromoblastomycosis tend to manifest on the lower extremities and are unlikely to manifest on the head. Sarcoidosis is another granulomatous skin eruption that can be clinically nonspecific.9 Histologically, lesions may demonstrate noncaseating granulomatous inflammation, as seen with cutaneous leishmaniasis, with a broad presentation; for example, lupus pernio, a sarcoid variant, manifests as large blue-red dusky nodules/plaques on the face, ears, or digits.9 Other sarcoid lesions include red/brown, thickened, circular plaques; variably discolored papulonodular lesions; or mucosal involvement.9 Ultimately, it is important to differentiate these nonspecific and similarly appearing lesions through diagnostic techniques such as AFB culture and smear, fungal staining, tuberculosis testing, and PCR in more challenging cases.

Treatment of cutaneous leishmaniasis should be individualized to each case.5 A more than 50% reduction in lesion size within 4 to 6 weeks indicates successful treatment. Ulcerated lesions should be fully re-epithelialized and healed by 3 months posttreatment. Treatment failure is categorized by failure of reepithelization, incomplete healing by 3 months, or worsening of the lesion at any time, each necessitating additional treatment, such as a second course of miltefosine or a different medication regimen.5 Careful monitoring is required throughout treatment, assessing for treatment failure, adding to the challenges of leishmaniasis.

In conclusion, CL requires a high index of suspicion in nonendemic areas to ensure successful diagnosis and treatment. Our case highlights the importance of using multimodal diagnostic techniques for CL, as a single modality may not exhibit a positive result due to variations in diagnostic accuracy. Our case also exhibits the complex treatment of CL, and the considerations that should be made when choosing a treatment modality.

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Clinical overview of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/leishmaniasis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- CDC DPDx Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

- Stark CG. Leishmaniasis differential diagnoses. Medscape. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/220298-differential

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:E202-E264. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw670

- Lewis FS. Dermatologic manifestations of leprosy. Medscape. June 19, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104977-overview

- Ngan V. Cutaneous tuberculosis. DermNet. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis

- Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis. Medscape. May 13, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-overview#a4

- Elyoussfi S, Coulson I. Sarcoidosis. DermNet. May 31, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sarcoidosis

- Leishmaniasis. World Health Organization. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis

- Clinical overview of leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 14, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/leishmaniasis/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

- CDC DPDx Leishmaniasis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/leishmaniasis/index.html

- Stark CG. Leishmaniasis differential diagnoses. Medscape. March 21, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/220298-differential

- Aronson N, Herwaldt BL, Libman M, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of leishmaniasis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH). Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:E202-E264. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw670

- Lewis FS. Dermatologic manifestations of leprosy. Medscape. June 19, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104977-overview

- Ngan V. Cutaneous tuberculosis. DermNet. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cutaneous-tuberculosis

- Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis. Medscape. May 13, 2023. Accessed October 12, 2024. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-overview#a4

- Elyoussfi S, Coulson I. Sarcoidosis. DermNet. May 31, 2024. Accessed October 25, 2024. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/sarcoidosis

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

Nonhealing Lesion on the Ear in a Child

A 10-year-old boy who recently emigrated from Afghanistan presented to his pediatrician for evaluation of a painless nonhealing plaque on the posterior left pinna of more than 1 year's duration. The lesion reportedly started as a small scratch following an ear injury, initially improved with an unknown topical treatment administered in Afghanistan, and then recurred with no other associated lesions and no known insect bite. The lesion persisted for more than 1 year postemigration before the patient presented to his pediatrician, who noted signs of excoriation, which was confirmed by the patient's father. The patient was started on a 7-day course of cephalexin oral suspension and topical mupirocin 2%. After 2 months without improvement, a 2-week course of oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was initiated; however, the lesion continued to grow with no signs of healing, and he was referred to dermatology.

The patient presented to pediatric dermatology 3 months after the initial presentation to his pediatrician and 2 weeks after he completed the course of oral trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. Physical examination demonstrated a papulosquamous eruption with swelling and blistering on the helix of the left ear. Based on these findings, the patient was started on a 1-month trial of topical triamcinolone 1% followed by the addition of topical pimecrolimus 1%. Due to no improvement of the lesion and subsequent progression to ulceration, a punch biopsy was performed.