User login

When tasked with outlining updated therapy regimens for rosacea, specific patient vignettes come to mind.

A 53-year-old male golfer presents with years of central facial flushing, prominent telangiectases, erythema, and scattered pink papules. He attempted various over-the-counter topical products indicated for acne, such as salicylic acid scrub and benzoyl peroxide cream, with no improvement and much irritation. Recently, his wife has been helping him apply redness-concealing makeup in the morning and over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream in the evening, which has been slightly helpful.

This patient’s rosacea could conceivably be labeled under the papulopustular rosacea subtype; however, the conventional categories are fluid with subtype overlap and imprecise diagnostic criteria. He also seemed to display features of the erythematotelangiectatic subtype, perhaps with underlying photodamage as well as steroid rebound erythema and/or atrophy.1 Nevertheless, it is a common presentation, and certain baseline tenets should be applied. First, all steroid products and irritants (eg, benzoyl peroxide and salicylic acid ingredients, any scrub vehicle) should be discontinued. Education about avoidance of triggers (ie, sun, heat, spicy food, alcohol, stress is paramount. Because barrier inadequacy is a recent insight into rosacea pathogenesis, mild syndet- or lipid-free cleansers, daily sunscreen, and evening emollients dictate baseline skin care, as does meticulous situation-specific sun protection.2,3 The papular component and immediate erythema in and around the papules can be managed topically (prior to sunscreen or emollient application) with metronidazole gel or cream up to twice daily, ivermectin cream once daily, or azelaic acid gel or foam up to twice daily. Oral doxycycline 40 mg (delayed release) on an empty stomach or 50 mg (immediate release) with food to avert antimicrobial dosing and antibiotic resistance also could be considered if topical therapy is inadequate or irritating, though gastrointestinal comorbidities with rosacea also should be delineated before initiating oral antibiotics.4-6 (Management of this patient’s nonlesional fixed erythema, telangiectases, and flushing is discussed after the next vignette.)

What if a woman presented in a similar fashion as above, only without papules? Her family physician prescribed metronidazole gel twice daily for years with no improvement in flushing, redness, or telangiectases.

Background erythema in rosacea often is persistent with trigger-specific intensification, with or without episodic facial flushing; undoubtedly, these symptoms can be difficult to compartmentalize depending on the clarity of the patient’s history and frequency of clinic visits. The aforementioned baseline skin care and sun-protection regimen applies, and newer topical agents such as α-adrenergics (daily oxymetazoline cream or brimonidine gel) may be considered for persistent erythema; however, irritant potential and rebound erythema are common.7-9 Topical therapies such as metronidazole gel, as in this case, are inadequate for persistent background erythema or flushing. Persistent erythema and telangiectases can be reduced with pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light modalities, particularly following conservative management of acute inflammation.5 Episodic flushing is poorly controlled with the above tactics, but anecdotally, topical or oral α-adrenergics or oral nonselective beta-blockers could be considered; the latter is also applicable to migraine therapy, which is perhaps comorbid with rosacea.5,10

A 35-year-old Hispanic woman states that the scalp, forehead, and cheeks have been flaky, pink, and pruritic for years. She saw several aestheticians for it and the admixed “acne” on the face, receiving salicylic acid chemical peels with no improvement and much dyspigmentation.

Although underreported, the commingling of rosacea with seborrheic dermatitis is common, perhaps with mutual Demodex mite overpopulation, assigning topical therapies to its management such as daily ivermectin cream or steroid-sparing pimecrolimus cream for inflammatory papules and scaly regions of the face and scalp.11-13 Further, this case exemplifies the increasing incidence and awareness of rosacea in darker skin types, along with its postinflammatory pigmentary perturbations, which necessitate repeated education about barrier control and sun protection.14

A 72-year-old male farmer presents with his wife whoinsists that his nose has been increasing in size for years; she procures a prior driver’s license photograph as proof. She also notes that he has been snoring at night and having more trouble breathing while working outdoors. The patient had not noticed.

Phymatous rosacea may exist as an additional feature of any rosacea subtype or as a singular finding, presenting as actively inflamed, fibrotic/noninflamed, or both. Management, particularly if inflamed, involves baseline gentle skin care and sun protection, avoidance of rosacea triggers, and implementation of oral therapy such as doxycycline or isotretinoin. Many cases, particularly those with a fibrotic component, warrant surgical methods such as fractionated CO2 laser or Shaw scalpel surgical sculpting. These cases frequently demonstrate varying degrees of airway compromise, validating surgery as a legitimate medical, not merely cosmetic, presentation.5,15

Final Thoughts

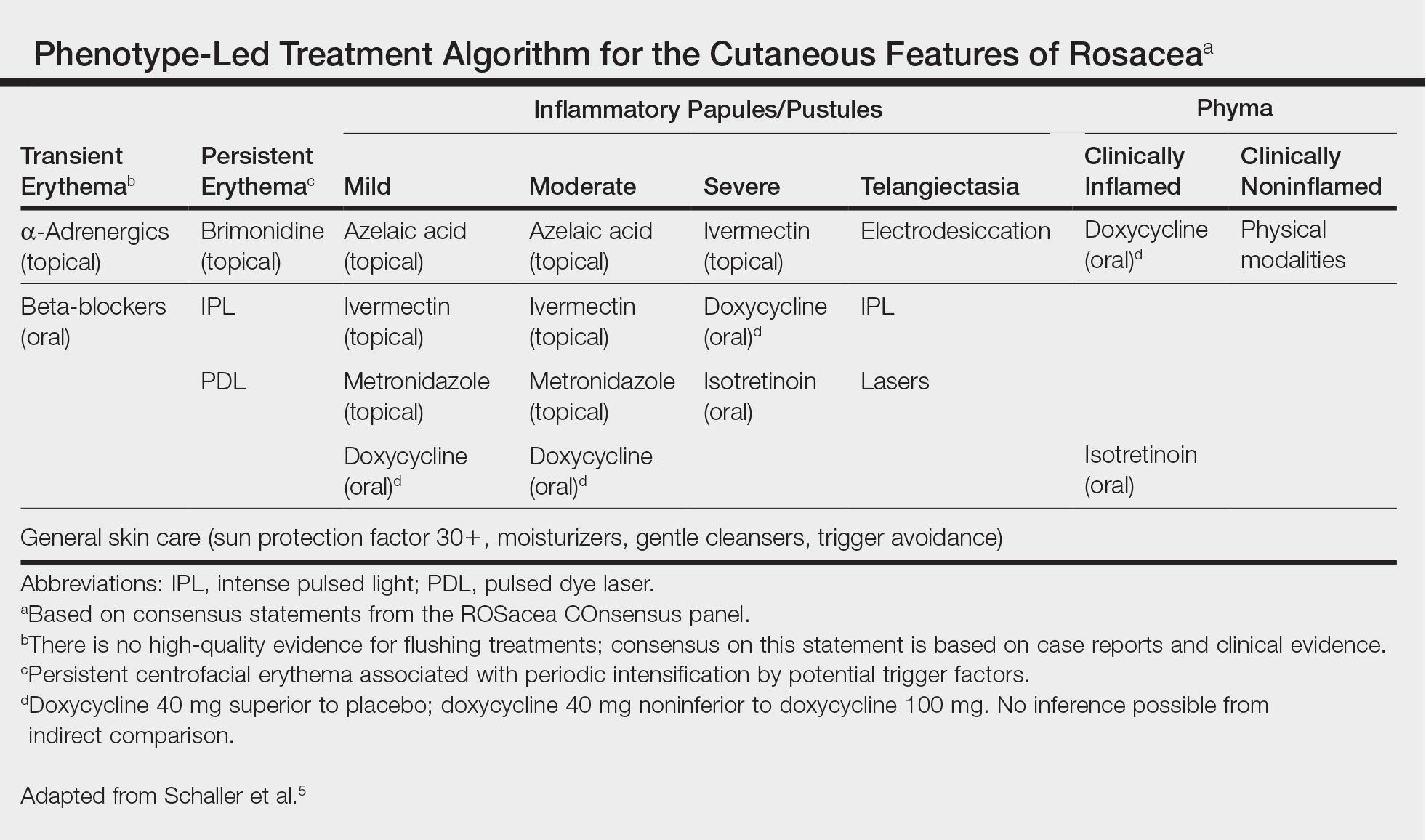

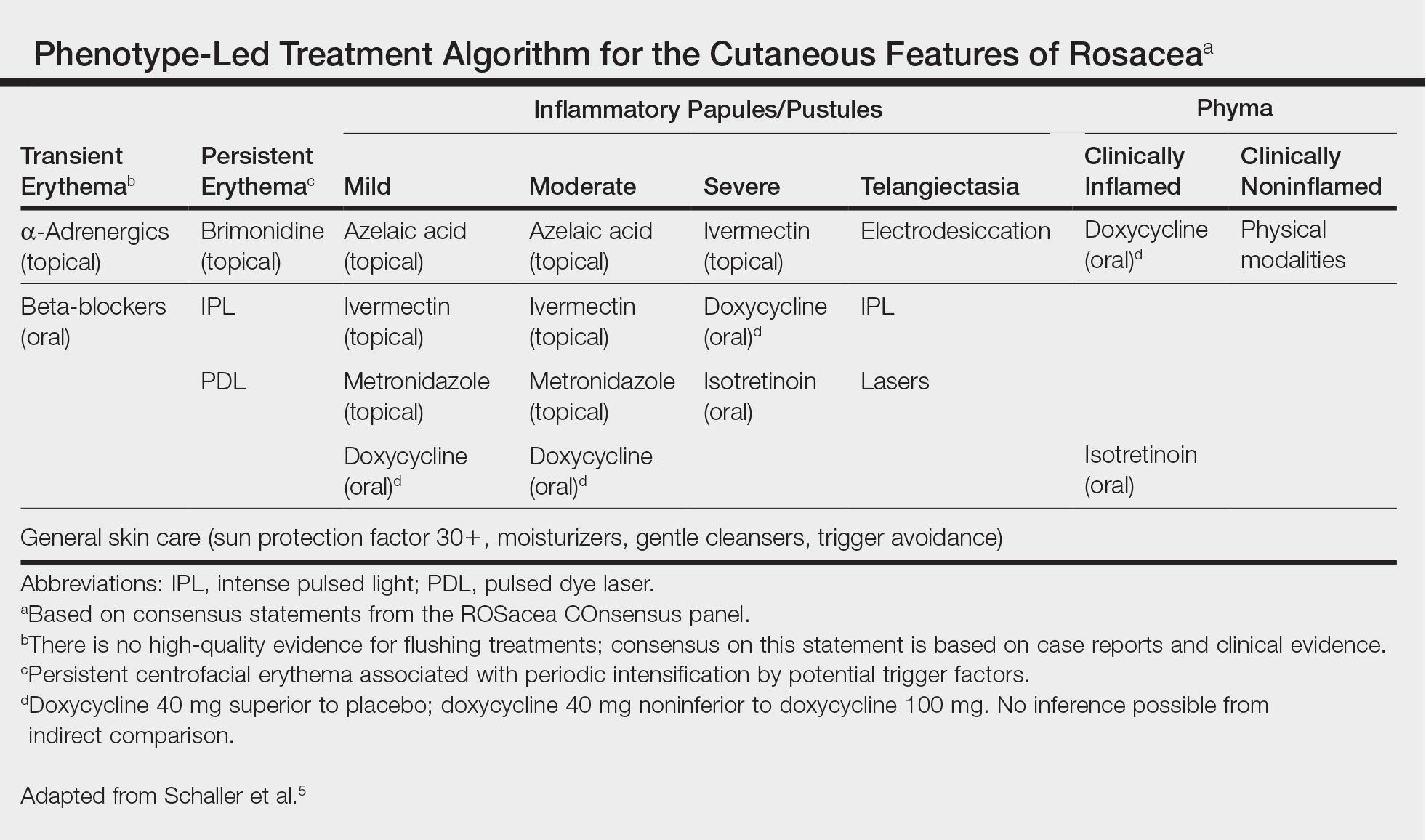

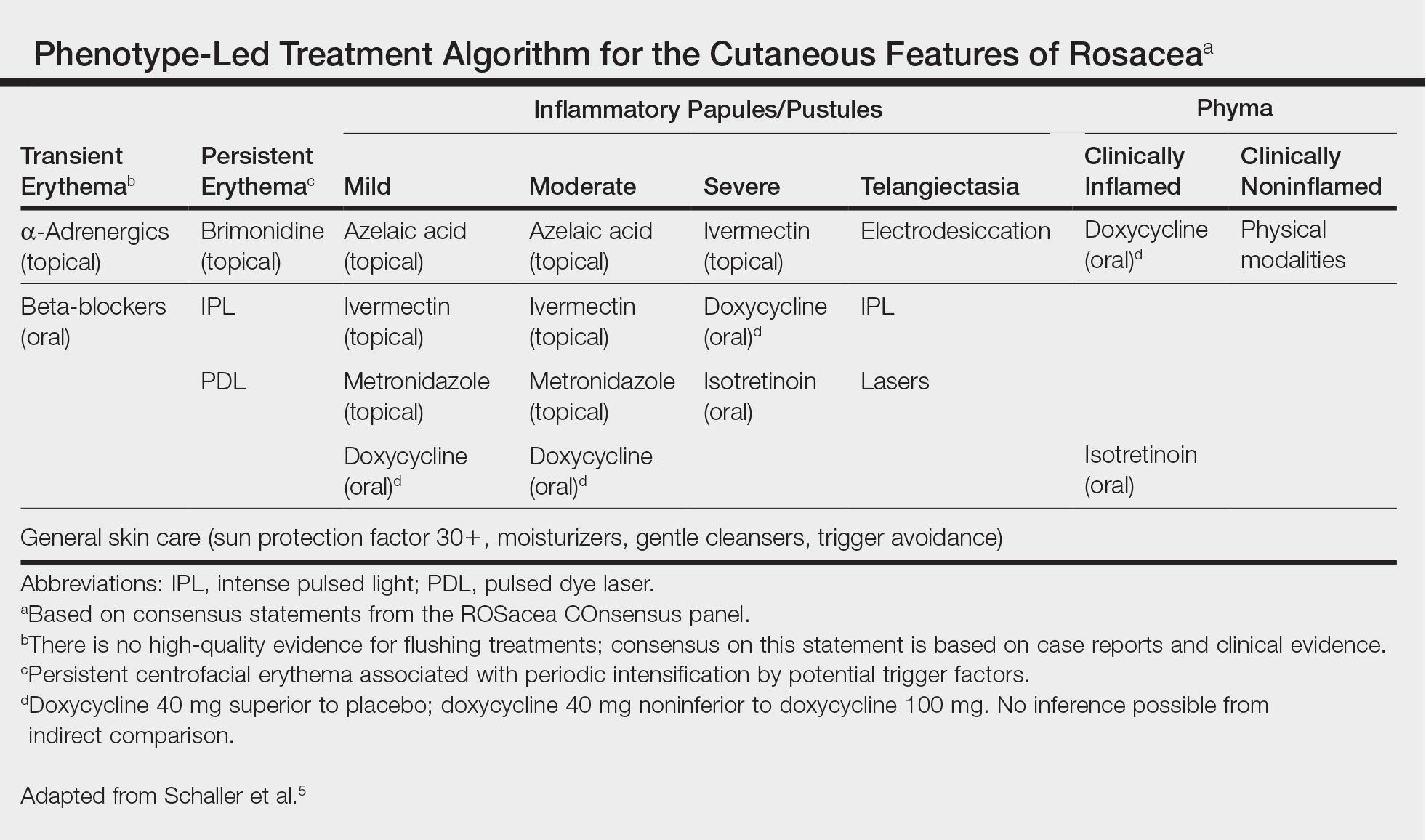

The Table, constructed as a concise therapy compendium by the ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) international panel of dermatologists and ophthalmologists, outlines data-driven and expert experience-based therapies for rosacea.5 This panel asserts that phenotypical features, not rigid subtypes, oblige patient-specific treatment schema. Also, as these cases outline, an evolving understanding of rosacea’s multifaceted pathogenesis, assorted presentations, and frequent pitfalls in daily skin care and initial management require individualized care.

- Tan J, Steinhoff M, Berg M, et al; Rosacea International Study Group. Shortcomings in rosacea diagnosis and classification. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:197-199.

- Levin J, Miller R. A guide to the ingredients and potential benefits of over-the-counter cleansers and moisturizers for rosacea patients. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:31-49.

- Del Rosso JQ. Adjunctive skin care in the management of rosacea: cleansers, moisturizers, and photoprotectants. Cutis. 2005;75(suppl 3):17-21;discussion 33-36.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Interventions for rosacea: abridged updated Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments [published online August 30, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:651-662.

- Schaller M, Almeida LM, Bewley A, et al. Rosacea treatment update: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:465-471.

- Egeberg A, Weinstock LB, Thvssen EP, et al. Rosacea and gastrointestinal disorders: a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:100-106.

- Layton AM, Schaller M, Homey B, et al. Brimonidine gel 0.33% rapidly improves patient-reported outcomes by controlling facial erythema of rosacea: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2405-2410.

- Docherty JR, Steinhoff M, Lorton D, et al. Multidisciplinary consideration of potential pathophysiologic mechanisms of paradoxical erythema with topical brimonidine therapy [published online August 25, 2016]. Adv Ther. 2016;33:1885-1895.

- Shanler SD, Ondo AL. Successful treatment of the erythema and flushing of rosacea using a topically applied selective alpha1-adrenergic receptor agonist, oxymetazoline. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1369-1371.

- Egeberg A, Ashina M, Gaist D, et al. Prevalence and risk of migraine in patients with rosacea: a population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:454-458.

- Zhao YE, Peng Y, Wang XL, et al. Facial dermatosis associated with Demodex: a case-control study. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:1008-1015.

- Siddiqui K, Stein Gold L, Gill J. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ivermectin compared with current topical treatments for the inflammatory lesions of rosacea: a network meta-analysis. Springerplus. 2016;5:1151. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2819-8.

- Kim MB, Kim GW, Park HJ, et al. Pimecrolimus 1% cream for the treatment of rosacea. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1135-1139.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, et al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Little SC, Stucker FJ, Compton A, et al. Nuances in the management of rhinophyma. Facial Plast Surg. 2012;28:231-237.

When tasked with outlining updated therapy regimens for rosacea, specific patient vignettes come to mind.

A 53-year-old male golfer presents with years of central facial flushing, prominent telangiectases, erythema, and scattered pink papules. He attempted various over-the-counter topical products indicated for acne, such as salicylic acid scrub and benzoyl peroxide cream, with no improvement and much irritation. Recently, his wife has been helping him apply redness-concealing makeup in the morning and over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream in the evening, which has been slightly helpful.

This patient’s rosacea could conceivably be labeled under the papulopustular rosacea subtype; however, the conventional categories are fluid with subtype overlap and imprecise diagnostic criteria. He also seemed to display features of the erythematotelangiectatic subtype, perhaps with underlying photodamage as well as steroid rebound erythema and/or atrophy.1 Nevertheless, it is a common presentation, and certain baseline tenets should be applied. First, all steroid products and irritants (eg, benzoyl peroxide and salicylic acid ingredients, any scrub vehicle) should be discontinued. Education about avoidance of triggers (ie, sun, heat, spicy food, alcohol, stress is paramount. Because barrier inadequacy is a recent insight into rosacea pathogenesis, mild syndet- or lipid-free cleansers, daily sunscreen, and evening emollients dictate baseline skin care, as does meticulous situation-specific sun protection.2,3 The papular component and immediate erythema in and around the papules can be managed topically (prior to sunscreen or emollient application) with metronidazole gel or cream up to twice daily, ivermectin cream once daily, or azelaic acid gel or foam up to twice daily. Oral doxycycline 40 mg (delayed release) on an empty stomach or 50 mg (immediate release) with food to avert antimicrobial dosing and antibiotic resistance also could be considered if topical therapy is inadequate or irritating, though gastrointestinal comorbidities with rosacea also should be delineated before initiating oral antibiotics.4-6 (Management of this patient’s nonlesional fixed erythema, telangiectases, and flushing is discussed after the next vignette.)

What if a woman presented in a similar fashion as above, only without papules? Her family physician prescribed metronidazole gel twice daily for years with no improvement in flushing, redness, or telangiectases.

Background erythema in rosacea often is persistent with trigger-specific intensification, with or without episodic facial flushing; undoubtedly, these symptoms can be difficult to compartmentalize depending on the clarity of the patient’s history and frequency of clinic visits. The aforementioned baseline skin care and sun-protection regimen applies, and newer topical agents such as α-adrenergics (daily oxymetazoline cream or brimonidine gel) may be considered for persistent erythema; however, irritant potential and rebound erythema are common.7-9 Topical therapies such as metronidazole gel, as in this case, are inadequate for persistent background erythema or flushing. Persistent erythema and telangiectases can be reduced with pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light modalities, particularly following conservative management of acute inflammation.5 Episodic flushing is poorly controlled with the above tactics, but anecdotally, topical or oral α-adrenergics or oral nonselective beta-blockers could be considered; the latter is also applicable to migraine therapy, which is perhaps comorbid with rosacea.5,10

A 35-year-old Hispanic woman states that the scalp, forehead, and cheeks have been flaky, pink, and pruritic for years. She saw several aestheticians for it and the admixed “acne” on the face, receiving salicylic acid chemical peels with no improvement and much dyspigmentation.

Although underreported, the commingling of rosacea with seborrheic dermatitis is common, perhaps with mutual Demodex mite overpopulation, assigning topical therapies to its management such as daily ivermectin cream or steroid-sparing pimecrolimus cream for inflammatory papules and scaly regions of the face and scalp.11-13 Further, this case exemplifies the increasing incidence and awareness of rosacea in darker skin types, along with its postinflammatory pigmentary perturbations, which necessitate repeated education about barrier control and sun protection.14

A 72-year-old male farmer presents with his wife whoinsists that his nose has been increasing in size for years; she procures a prior driver’s license photograph as proof. She also notes that he has been snoring at night and having more trouble breathing while working outdoors. The patient had not noticed.

Phymatous rosacea may exist as an additional feature of any rosacea subtype or as a singular finding, presenting as actively inflamed, fibrotic/noninflamed, or both. Management, particularly if inflamed, involves baseline gentle skin care and sun protection, avoidance of rosacea triggers, and implementation of oral therapy such as doxycycline or isotretinoin. Many cases, particularly those with a fibrotic component, warrant surgical methods such as fractionated CO2 laser or Shaw scalpel surgical sculpting. These cases frequently demonstrate varying degrees of airway compromise, validating surgery as a legitimate medical, not merely cosmetic, presentation.5,15

Final Thoughts

The Table, constructed as a concise therapy compendium by the ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) international panel of dermatologists and ophthalmologists, outlines data-driven and expert experience-based therapies for rosacea.5 This panel asserts that phenotypical features, not rigid subtypes, oblige patient-specific treatment schema. Also, as these cases outline, an evolving understanding of rosacea’s multifaceted pathogenesis, assorted presentations, and frequent pitfalls in daily skin care and initial management require individualized care.

When tasked with outlining updated therapy regimens for rosacea, specific patient vignettes come to mind.

A 53-year-old male golfer presents with years of central facial flushing, prominent telangiectases, erythema, and scattered pink papules. He attempted various over-the-counter topical products indicated for acne, such as salicylic acid scrub and benzoyl peroxide cream, with no improvement and much irritation. Recently, his wife has been helping him apply redness-concealing makeup in the morning and over-the-counter hydrocortisone cream in the evening, which has been slightly helpful.

This patient’s rosacea could conceivably be labeled under the papulopustular rosacea subtype; however, the conventional categories are fluid with subtype overlap and imprecise diagnostic criteria. He also seemed to display features of the erythematotelangiectatic subtype, perhaps with underlying photodamage as well as steroid rebound erythema and/or atrophy.1 Nevertheless, it is a common presentation, and certain baseline tenets should be applied. First, all steroid products and irritants (eg, benzoyl peroxide and salicylic acid ingredients, any scrub vehicle) should be discontinued. Education about avoidance of triggers (ie, sun, heat, spicy food, alcohol, stress is paramount. Because barrier inadequacy is a recent insight into rosacea pathogenesis, mild syndet- or lipid-free cleansers, daily sunscreen, and evening emollients dictate baseline skin care, as does meticulous situation-specific sun protection.2,3 The papular component and immediate erythema in and around the papules can be managed topically (prior to sunscreen or emollient application) with metronidazole gel or cream up to twice daily, ivermectin cream once daily, or azelaic acid gel or foam up to twice daily. Oral doxycycline 40 mg (delayed release) on an empty stomach or 50 mg (immediate release) with food to avert antimicrobial dosing and antibiotic resistance also could be considered if topical therapy is inadequate or irritating, though gastrointestinal comorbidities with rosacea also should be delineated before initiating oral antibiotics.4-6 (Management of this patient’s nonlesional fixed erythema, telangiectases, and flushing is discussed after the next vignette.)

What if a woman presented in a similar fashion as above, only without papules? Her family physician prescribed metronidazole gel twice daily for years with no improvement in flushing, redness, or telangiectases.

Background erythema in rosacea often is persistent with trigger-specific intensification, with or without episodic facial flushing; undoubtedly, these symptoms can be difficult to compartmentalize depending on the clarity of the patient’s history and frequency of clinic visits. The aforementioned baseline skin care and sun-protection regimen applies, and newer topical agents such as α-adrenergics (daily oxymetazoline cream or brimonidine gel) may be considered for persistent erythema; however, irritant potential and rebound erythema are common.7-9 Topical therapies such as metronidazole gel, as in this case, are inadequate for persistent background erythema or flushing. Persistent erythema and telangiectases can be reduced with pulsed dye laser or intense pulsed light modalities, particularly following conservative management of acute inflammation.5 Episodic flushing is poorly controlled with the above tactics, but anecdotally, topical or oral α-adrenergics or oral nonselective beta-blockers could be considered; the latter is also applicable to migraine therapy, which is perhaps comorbid with rosacea.5,10

A 35-year-old Hispanic woman states that the scalp, forehead, and cheeks have been flaky, pink, and pruritic for years. She saw several aestheticians for it and the admixed “acne” on the face, receiving salicylic acid chemical peels with no improvement and much dyspigmentation.

Although underreported, the commingling of rosacea with seborrheic dermatitis is common, perhaps with mutual Demodex mite overpopulation, assigning topical therapies to its management such as daily ivermectin cream or steroid-sparing pimecrolimus cream for inflammatory papules and scaly regions of the face and scalp.11-13 Further, this case exemplifies the increasing incidence and awareness of rosacea in darker skin types, along with its postinflammatory pigmentary perturbations, which necessitate repeated education about barrier control and sun protection.14

A 72-year-old male farmer presents with his wife whoinsists that his nose has been increasing in size for years; she procures a prior driver’s license photograph as proof. She also notes that he has been snoring at night and having more trouble breathing while working outdoors. The patient had not noticed.

Phymatous rosacea may exist as an additional feature of any rosacea subtype or as a singular finding, presenting as actively inflamed, fibrotic/noninflamed, or both. Management, particularly if inflamed, involves baseline gentle skin care and sun protection, avoidance of rosacea triggers, and implementation of oral therapy such as doxycycline or isotretinoin. Many cases, particularly those with a fibrotic component, warrant surgical methods such as fractionated CO2 laser or Shaw scalpel surgical sculpting. These cases frequently demonstrate varying degrees of airway compromise, validating surgery as a legitimate medical, not merely cosmetic, presentation.5,15

Final Thoughts

The Table, constructed as a concise therapy compendium by the ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) international panel of dermatologists and ophthalmologists, outlines data-driven and expert experience-based therapies for rosacea.5 This panel asserts that phenotypical features, not rigid subtypes, oblige patient-specific treatment schema. Also, as these cases outline, an evolving understanding of rosacea’s multifaceted pathogenesis, assorted presentations, and frequent pitfalls in daily skin care and initial management require individualized care.

- Tan J, Steinhoff M, Berg M, et al; Rosacea International Study Group. Shortcomings in rosacea diagnosis and classification. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:197-199.

- Levin J, Miller R. A guide to the ingredients and potential benefits of over-the-counter cleansers and moisturizers for rosacea patients. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:31-49.

- Del Rosso JQ. Adjunctive skin care in the management of rosacea: cleansers, moisturizers, and photoprotectants. Cutis. 2005;75(suppl 3):17-21;discussion 33-36.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Interventions for rosacea: abridged updated Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments [published online August 30, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:651-662.

- Schaller M, Almeida LM, Bewley A, et al. Rosacea treatment update: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:465-471.

- Egeberg A, Weinstock LB, Thvssen EP, et al. Rosacea and gastrointestinal disorders: a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:100-106.

- Layton AM, Schaller M, Homey B, et al. Brimonidine gel 0.33% rapidly improves patient-reported outcomes by controlling facial erythema of rosacea: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2405-2410.

- Docherty JR, Steinhoff M, Lorton D, et al. Multidisciplinary consideration of potential pathophysiologic mechanisms of paradoxical erythema with topical brimonidine therapy [published online August 25, 2016]. Adv Ther. 2016;33:1885-1895.

- Shanler SD, Ondo AL. Successful treatment of the erythema and flushing of rosacea using a topically applied selective alpha1-adrenergic receptor agonist, oxymetazoline. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1369-1371.

- Egeberg A, Ashina M, Gaist D, et al. Prevalence and risk of migraine in patients with rosacea: a population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:454-458.

- Zhao YE, Peng Y, Wang XL, et al. Facial dermatosis associated with Demodex: a case-control study. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:1008-1015.

- Siddiqui K, Stein Gold L, Gill J. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ivermectin compared with current topical treatments for the inflammatory lesions of rosacea: a network meta-analysis. Springerplus. 2016;5:1151. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2819-8.

- Kim MB, Kim GW, Park HJ, et al. Pimecrolimus 1% cream for the treatment of rosacea. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1135-1139.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, et al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Little SC, Stucker FJ, Compton A, et al. Nuances in the management of rhinophyma. Facial Plast Surg. 2012;28:231-237.

- Tan J, Steinhoff M, Berg M, et al; Rosacea International Study Group. Shortcomings in rosacea diagnosis and classification. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:197-199.

- Levin J, Miller R. A guide to the ingredients and potential benefits of over-the-counter cleansers and moisturizers for rosacea patients. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2011;4:31-49.

- Del Rosso JQ. Adjunctive skin care in the management of rosacea: cleansers, moisturizers, and photoprotectants. Cutis. 2005;75(suppl 3):17-21;discussion 33-36.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z. Interventions for rosacea: abridged updated Cochrane systematic review including GRADE assessments [published online August 30, 2015]. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:651-662.

- Schaller M, Almeida LM, Bewley A, et al. Rosacea treatment update: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:465-471.

- Egeberg A, Weinstock LB, Thvssen EP, et al. Rosacea and gastrointestinal disorders: a population-based cohort study. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:100-106.

- Layton AM, Schaller M, Homey B, et al. Brimonidine gel 0.33% rapidly improves patient-reported outcomes by controlling facial erythema of rosacea: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2405-2410.

- Docherty JR, Steinhoff M, Lorton D, et al. Multidisciplinary consideration of potential pathophysiologic mechanisms of paradoxical erythema with topical brimonidine therapy [published online August 25, 2016]. Adv Ther. 2016;33:1885-1895.

- Shanler SD, Ondo AL. Successful treatment of the erythema and flushing of rosacea using a topically applied selective alpha1-adrenergic receptor agonist, oxymetazoline. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:1369-1371.

- Egeberg A, Ashina M, Gaist D, et al. Prevalence and risk of migraine in patients with rosacea: a population-based cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:454-458.

- Zhao YE, Peng Y, Wang XL, et al. Facial dermatosis associated with Demodex: a case-control study. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2011;12:1008-1015.

- Siddiqui K, Stein Gold L, Gill J. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ivermectin compared with current topical treatments for the inflammatory lesions of rosacea: a network meta-analysis. Springerplus. 2016;5:1151. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2819-8.

- Kim MB, Kim GW, Park HJ, et al. Pimecrolimus 1% cream for the treatment of rosacea. J Dermatol. 2011;38:1135-1139.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, et al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20. pii:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Little SC, Stucker FJ, Compton A, et al. Nuances in the management of rhinophyma. Facial Plast Surg. 2012;28:231-237.