User login

PRACTICE CHANGER

Stop using low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) for surgical procedures to “bridge” low- to moderate-risk patients with atrial fibrillation (CHADS2 score ≤ 4) who are receiving warfarin. The risks outweigh the benefits.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single good-quality randomized controlled trial.1

CASE A 75-year-old man comes to your office for surgical clearance before right knee replacement surgery. He has diabetes and high blood pressure and is taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation. He is scheduled for surgery in a week. What is the safest way to manage his warfarin in the perioperative period?

More than 2 million people are being treated with oral anticoagulation in North America to prevent stroke or to prevent or treat venous thromboembolism.2 Since 2010, several new oral anticoagulants have been approved, including dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban. These new medications have a shorter half-life than older anticoagulants, which enables them to be stopped one to two days before surgery.

On the other hand, warfarin—which remains a common choice for anticoagulation—has a three- to seven-day onset and elimination.3,4 This long clinical half-life presents a special challenge during the perioperative period. To reduce the risk for operative bleeding, the warfarin must be stopped days prior to the procedure, but clinicians often worry that this will increase the risk for arterial or venous thromboembolism, including stroke.

An estimated 250,000 patients need perioperative management of their anticoagulation each year.5 As the US population continues to age and the incidence of conditions requiring anticoagulation (particularly atrial fibrillation) increases, this number is only going to rise.6

Current guidelines on bridging. American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines recommend transition to “a short-acting anticoagulant, consisting of subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or intravenous unfractionated heparin, for a 10- to 12-day period during interruption of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy.”5Furthermore, for an appropriate bridging regimen, the ACCP guidelines recommend stopping VKA therapy five days prior to the procedure and utilizing LMWH from within 24 to 48 hours of stopping VKA therapy until up to 24 hours before surgery.5 Postoperatively, VKA or LMWH therapy should be reinitiated within 24 hours and 24 to 72 hours, respectively, depending on the patient’s risk for bleeding during surgery.5

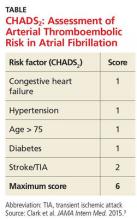

These guidelines recommend using CHADS2 scoring (see the table) to determine arterial thromboembolism (ATE) risk in atrial fibrillation.3,5 Patients at low risk for ATE (CHADS2 score, 0-2) should not be bridged, and patients at high risk (CHADS2 score, 5-6) should always be bridged.5 These guidelines are less clear about bridging recommendations for patients considered to be at moderate risk (CHADS2 score, 3-4).

Previous evidence on bridging. A 2012 meta-analysis of 34 studies evaluated the safety and efficacy of perioperative bridging with heparin in patients receiving VKA.7Researchers found no difference in ATE events in eight studies that compared groups that received bridging vs groups that simply stopped anticoagulation (odds ratio [OR], 0.80).7 The group that received bridging had an increased risk for overall bleeding in 13 studies and of major bleeding in five studies.7This meta-analysis was limited by poor study quality and variation in the indication for VKA therapy.

A 2015 subgroup analysis of a larger cohort study of patients receiving anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation found an increased risk for bleeding when their anticoagulation was interrupted for procedures (OR for major bleeding, 3.84).8

Douketis et al1 conducted a randomized trial to clarify the need for and safety of bridging anticoagulation for ATE in patients with atrial fibrillation who were receiving warfarin.

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

When it comes to stroke/TIA, there’s no advantage to bridging

This double-blind, placebo-controlled trial compared bridging with dalteparin, a form of LMWH, to placebo among 1,884 patients with atrial fibrillation who were taking warfarin and whose anticoagulation therapy needed to be interrupted for an elective procedure. Patients were included if they were receiving warfarin to prevent stroke and had been taking it for at least 12 weeks, with a goal International Normalized Ratio (INR) of 2.0 to 3.0. Exclusion criteria included having a mechanical heart valve or having a stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA; 12 weeks prior) or major bleeding (six weeks prior). Patients undergoing cardiac, intracranial, and intraspinal surgeries were also excluded from the study.

The mean CHADS2 score was 2.3; 38.3% of patients had a CHADS2 score ≥ 3, and 9.4% of patients had a history of stroke. Forty-four percent of patients underwent a gastrointestinal procedure, 17.2% underwent a cardiothoracic procedure, and 9.2% underwent an orthopedic procedure.

Patients stopped taking warfarin five days before their procedure and began subcutaneous dalteparin (100 IU/kg) or an identical placebo three days before the procedure. The dalteparin/placebo was stopped 24 hours before the procedure and restarted after the procedure, until the patient’s INR was in the therapeutic range. Warfarin was resumed on the evening of the procedure or the following day.

The primary efficacy outcome was ATE, including stroke, TIA, or systemic embolism. The primary safety endpoint was major bleeding (defined as bleeding at a critical anatomic site, symptomatic or clinically overt bleeding, or a decrease in hemoglobin > 2 g/dL). Secondary efficacy and safety outcomes included minor bleeding, acute myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and death. Outcomes were assessed within 37 days of the procedure.

The incidence of ATE was 0.4% (four events) in the no-bridging group vs 0.3% (three events) in the bridging group. Major bleeding occurred in 1.3% of the no-bridging group (12 events) and in 3.2% of the bridging group (29 events), indicating that no bridging was superior in terms of the major bleeding outcome (number needed to harm [NNH], 53; relative risk [RR], 0.41).

The no-bridging group also had significantly fewer minor bleeds in comparison to the bridging group (NNH, 11; 12% vs 20.9%). There were no differences between groups in other secondary outcomes.

Continue for what's new >>

WHAT’S NEW

High-quality evidence suggests it’s OK to stop warfarin before surgery

This is the largest good-quality study to evaluate perioperative bridging in patients with atrial fibrillation who were at low or moderate risk for ATE (CHADS2 score, 0-4). Previous studies suggested bridging increased bleeding and offered limited benefit for reducing the risk for ATE. However, this is the first study to include a large group of moderate-risk patients (CHADS2 score, 3-4). This trial provides high-quality evidence to support the practice of simply stopping warfarin in the perioperative period, rather than bridging with LMWH.

CAVEATS

Findings might not apply to patients at highest risk

Most patients in this study had a CHADS2 score ≤ 3. About 3% had a CHADS2 score ≥ 5. It’s not clear whether these findings apply to patients with a CHADS2 score of 5 or 6.

This trial categorized ATE risk using the CHADS2 score, rather than the CHA2DS2-VASc, which includes additional risk factors and may more accurately predict stroke risk. Both patients who received bridging therapy and those who did not had a lower rate of stroke than predicted by CHADS2. This may reflect a limit of the predictive value of CHADS2 but should not have affected the rate of bleeding or ATE outcomes in this study.

Continue for challenges to implementation >>

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Providers may hesitate to disregard current guidelines

Strokes are devastating events for patients, families, and clinicians, and they pose a greater risk for morbidity and mortality compared to bleeding. However, this study suggests patients who receive bridging have a higher risk for bleeding than stroke, which is in contrast to some providers’ experience and current recommendations.

A clinician caring for a patient who’s had a stroke may be inclined to recommend bridging despite the lack of efficacy and evidence of bleeding risk. Additionally, until guidelines reflect the most current research, clinicians may be reluctant to provide care in contrast to these recommendations.

REFERENCES

1. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:823-833.

2. Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, et al; American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:7S-47S.

3. Clark NP, Witt DM, Davies LE, et al. Bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism and mortality risks during warfarin interruption for invasive procedures. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175:1163-1168.

4. Lip GY, Lane DA. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review.JAMA. 2015;313:1950-1962.

5. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e326S-e350S.

6. Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence.Circulation. 2006;114:119-125.

7. Siegal D, Yudin J, Kaatz S, et al. Periprocedural heparin bridging in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists: systematic review and meta-analysis of bleeding and thromboembolic rates.Circulation. 2012;126:1630-1639.

8. Steinberg B, Peterson E, Kim S, et al; Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators and Patients. Use and outcomes associated with bridging during anticoagulation interruptions in patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF).Circulation. 2015;131:488-494.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2015. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2015;64(12):794-795, 800.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Stop using low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) for surgical procedures to “bridge” low- to moderate-risk patients with atrial fibrillation (CHADS2 score ≤ 4) who are receiving warfarin. The risks outweigh the benefits.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single good-quality randomized controlled trial.1

CASE A 75-year-old man comes to your office for surgical clearance before right knee replacement surgery. He has diabetes and high blood pressure and is taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation. He is scheduled for surgery in a week. What is the safest way to manage his warfarin in the perioperative period?

More than 2 million people are being treated with oral anticoagulation in North America to prevent stroke or to prevent or treat venous thromboembolism.2 Since 2010, several new oral anticoagulants have been approved, including dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban. These new medications have a shorter half-life than older anticoagulants, which enables them to be stopped one to two days before surgery.

On the other hand, warfarin—which remains a common choice for anticoagulation—has a three- to seven-day onset and elimination.3,4 This long clinical half-life presents a special challenge during the perioperative period. To reduce the risk for operative bleeding, the warfarin must be stopped days prior to the procedure, but clinicians often worry that this will increase the risk for arterial or venous thromboembolism, including stroke.

An estimated 250,000 patients need perioperative management of their anticoagulation each year.5 As the US population continues to age and the incidence of conditions requiring anticoagulation (particularly atrial fibrillation) increases, this number is only going to rise.6

Current guidelines on bridging. American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines recommend transition to “a short-acting anticoagulant, consisting of subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or intravenous unfractionated heparin, for a 10- to 12-day period during interruption of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy.”5Furthermore, for an appropriate bridging regimen, the ACCP guidelines recommend stopping VKA therapy five days prior to the procedure and utilizing LMWH from within 24 to 48 hours of stopping VKA therapy until up to 24 hours before surgery.5 Postoperatively, VKA or LMWH therapy should be reinitiated within 24 hours and 24 to 72 hours, respectively, depending on the patient’s risk for bleeding during surgery.5

These guidelines recommend using CHADS2 scoring (see the table) to determine arterial thromboembolism (ATE) risk in atrial fibrillation.3,5 Patients at low risk for ATE (CHADS2 score, 0-2) should not be bridged, and patients at high risk (CHADS2 score, 5-6) should always be bridged.5 These guidelines are less clear about bridging recommendations for patients considered to be at moderate risk (CHADS2 score, 3-4).

Previous evidence on bridging. A 2012 meta-analysis of 34 studies evaluated the safety and efficacy of perioperative bridging with heparin in patients receiving VKA.7Researchers found no difference in ATE events in eight studies that compared groups that received bridging vs groups that simply stopped anticoagulation (odds ratio [OR], 0.80).7 The group that received bridging had an increased risk for overall bleeding in 13 studies and of major bleeding in five studies.7This meta-analysis was limited by poor study quality and variation in the indication for VKA therapy.

A 2015 subgroup analysis of a larger cohort study of patients receiving anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation found an increased risk for bleeding when their anticoagulation was interrupted for procedures (OR for major bleeding, 3.84).8

Douketis et al1 conducted a randomized trial to clarify the need for and safety of bridging anticoagulation for ATE in patients with atrial fibrillation who were receiving warfarin.

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

When it comes to stroke/TIA, there’s no advantage to bridging

This double-blind, placebo-controlled trial compared bridging with dalteparin, a form of LMWH, to placebo among 1,884 patients with atrial fibrillation who were taking warfarin and whose anticoagulation therapy needed to be interrupted for an elective procedure. Patients were included if they were receiving warfarin to prevent stroke and had been taking it for at least 12 weeks, with a goal International Normalized Ratio (INR) of 2.0 to 3.0. Exclusion criteria included having a mechanical heart valve or having a stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA; 12 weeks prior) or major bleeding (six weeks prior). Patients undergoing cardiac, intracranial, and intraspinal surgeries were also excluded from the study.

The mean CHADS2 score was 2.3; 38.3% of patients had a CHADS2 score ≥ 3, and 9.4% of patients had a history of stroke. Forty-four percent of patients underwent a gastrointestinal procedure, 17.2% underwent a cardiothoracic procedure, and 9.2% underwent an orthopedic procedure.

Patients stopped taking warfarin five days before their procedure and began subcutaneous dalteparin (100 IU/kg) or an identical placebo three days before the procedure. The dalteparin/placebo was stopped 24 hours before the procedure and restarted after the procedure, until the patient’s INR was in the therapeutic range. Warfarin was resumed on the evening of the procedure or the following day.

The primary efficacy outcome was ATE, including stroke, TIA, or systemic embolism. The primary safety endpoint was major bleeding (defined as bleeding at a critical anatomic site, symptomatic or clinically overt bleeding, or a decrease in hemoglobin > 2 g/dL). Secondary efficacy and safety outcomes included minor bleeding, acute myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and death. Outcomes were assessed within 37 days of the procedure.

The incidence of ATE was 0.4% (four events) in the no-bridging group vs 0.3% (three events) in the bridging group. Major bleeding occurred in 1.3% of the no-bridging group (12 events) and in 3.2% of the bridging group (29 events), indicating that no bridging was superior in terms of the major bleeding outcome (number needed to harm [NNH], 53; relative risk [RR], 0.41).

The no-bridging group also had significantly fewer minor bleeds in comparison to the bridging group (NNH, 11; 12% vs 20.9%). There were no differences between groups in other secondary outcomes.

Continue for what's new >>

WHAT’S NEW

High-quality evidence suggests it’s OK to stop warfarin before surgery

This is the largest good-quality study to evaluate perioperative bridging in patients with atrial fibrillation who were at low or moderate risk for ATE (CHADS2 score, 0-4). Previous studies suggested bridging increased bleeding and offered limited benefit for reducing the risk for ATE. However, this is the first study to include a large group of moderate-risk patients (CHADS2 score, 3-4). This trial provides high-quality evidence to support the practice of simply stopping warfarin in the perioperative period, rather than bridging with LMWH.

CAVEATS

Findings might not apply to patients at highest risk

Most patients in this study had a CHADS2 score ≤ 3. About 3% had a CHADS2 score ≥ 5. It’s not clear whether these findings apply to patients with a CHADS2 score of 5 or 6.

This trial categorized ATE risk using the CHADS2 score, rather than the CHA2DS2-VASc, which includes additional risk factors and may more accurately predict stroke risk. Both patients who received bridging therapy and those who did not had a lower rate of stroke than predicted by CHADS2. This may reflect a limit of the predictive value of CHADS2 but should not have affected the rate of bleeding or ATE outcomes in this study.

Continue for challenges to implementation >>

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Providers may hesitate to disregard current guidelines

Strokes are devastating events for patients, families, and clinicians, and they pose a greater risk for morbidity and mortality compared to bleeding. However, this study suggests patients who receive bridging have a higher risk for bleeding than stroke, which is in contrast to some providers’ experience and current recommendations.

A clinician caring for a patient who’s had a stroke may be inclined to recommend bridging despite the lack of efficacy and evidence of bleeding risk. Additionally, until guidelines reflect the most current research, clinicians may be reluctant to provide care in contrast to these recommendations.

REFERENCES

1. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:823-833.

2. Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, et al; American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:7S-47S.

3. Clark NP, Witt DM, Davies LE, et al. Bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism and mortality risks during warfarin interruption for invasive procedures. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175:1163-1168.

4. Lip GY, Lane DA. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review.JAMA. 2015;313:1950-1962.

5. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e326S-e350S.

6. Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence.Circulation. 2006;114:119-125.

7. Siegal D, Yudin J, Kaatz S, et al. Periprocedural heparin bridging in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists: systematic review and meta-analysis of bleeding and thromboembolic rates.Circulation. 2012;126:1630-1639.

8. Steinberg B, Peterson E, Kim S, et al; Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators and Patients. Use and outcomes associated with bridging during anticoagulation interruptions in patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF).Circulation. 2015;131:488-494.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2015. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2015;64(12):794-795, 800.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Stop using low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) for surgical procedures to “bridge” low- to moderate-risk patients with atrial fibrillation (CHADS2 score ≤ 4) who are receiving warfarin. The risks outweigh the benefits.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on a single good-quality randomized controlled trial.1

CASE A 75-year-old man comes to your office for surgical clearance before right knee replacement surgery. He has diabetes and high blood pressure and is taking warfarin for atrial fibrillation. He is scheduled for surgery in a week. What is the safest way to manage his warfarin in the perioperative period?

More than 2 million people are being treated with oral anticoagulation in North America to prevent stroke or to prevent or treat venous thromboembolism.2 Since 2010, several new oral anticoagulants have been approved, including dabigatran, apixaban, and rivaroxaban. These new medications have a shorter half-life than older anticoagulants, which enables them to be stopped one to two days before surgery.

On the other hand, warfarin—which remains a common choice for anticoagulation—has a three- to seven-day onset and elimination.3,4 This long clinical half-life presents a special challenge during the perioperative period. To reduce the risk for operative bleeding, the warfarin must be stopped days prior to the procedure, but clinicians often worry that this will increase the risk for arterial or venous thromboembolism, including stroke.

An estimated 250,000 patients need perioperative management of their anticoagulation each year.5 As the US population continues to age and the incidence of conditions requiring anticoagulation (particularly atrial fibrillation) increases, this number is only going to rise.6

Current guidelines on bridging. American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guidelines recommend transition to “a short-acting anticoagulant, consisting of subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) or intravenous unfractionated heparin, for a 10- to 12-day period during interruption of vitamin K antagonist (VKA) therapy.”5Furthermore, for an appropriate bridging regimen, the ACCP guidelines recommend stopping VKA therapy five days prior to the procedure and utilizing LMWH from within 24 to 48 hours of stopping VKA therapy until up to 24 hours before surgery.5 Postoperatively, VKA or LMWH therapy should be reinitiated within 24 hours and 24 to 72 hours, respectively, depending on the patient’s risk for bleeding during surgery.5

These guidelines recommend using CHADS2 scoring (see the table) to determine arterial thromboembolism (ATE) risk in atrial fibrillation.3,5 Patients at low risk for ATE (CHADS2 score, 0-2) should not be bridged, and patients at high risk (CHADS2 score, 5-6) should always be bridged.5 These guidelines are less clear about bridging recommendations for patients considered to be at moderate risk (CHADS2 score, 3-4).

Previous evidence on bridging. A 2012 meta-analysis of 34 studies evaluated the safety and efficacy of perioperative bridging with heparin in patients receiving VKA.7Researchers found no difference in ATE events in eight studies that compared groups that received bridging vs groups that simply stopped anticoagulation (odds ratio [OR], 0.80).7 The group that received bridging had an increased risk for overall bleeding in 13 studies and of major bleeding in five studies.7This meta-analysis was limited by poor study quality and variation in the indication for VKA therapy.

A 2015 subgroup analysis of a larger cohort study of patients receiving anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation found an increased risk for bleeding when their anticoagulation was interrupted for procedures (OR for major bleeding, 3.84).8

Douketis et al1 conducted a randomized trial to clarify the need for and safety of bridging anticoagulation for ATE in patients with atrial fibrillation who were receiving warfarin.

Continue for study summary >>

STUDY SUMMARY

When it comes to stroke/TIA, there’s no advantage to bridging

This double-blind, placebo-controlled trial compared bridging with dalteparin, a form of LMWH, to placebo among 1,884 patients with atrial fibrillation who were taking warfarin and whose anticoagulation therapy needed to be interrupted for an elective procedure. Patients were included if they were receiving warfarin to prevent stroke and had been taking it for at least 12 weeks, with a goal International Normalized Ratio (INR) of 2.0 to 3.0. Exclusion criteria included having a mechanical heart valve or having a stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA; 12 weeks prior) or major bleeding (six weeks prior). Patients undergoing cardiac, intracranial, and intraspinal surgeries were also excluded from the study.

The mean CHADS2 score was 2.3; 38.3% of patients had a CHADS2 score ≥ 3, and 9.4% of patients had a history of stroke. Forty-four percent of patients underwent a gastrointestinal procedure, 17.2% underwent a cardiothoracic procedure, and 9.2% underwent an orthopedic procedure.

Patients stopped taking warfarin five days before their procedure and began subcutaneous dalteparin (100 IU/kg) or an identical placebo three days before the procedure. The dalteparin/placebo was stopped 24 hours before the procedure and restarted after the procedure, until the patient’s INR was in the therapeutic range. Warfarin was resumed on the evening of the procedure or the following day.

The primary efficacy outcome was ATE, including stroke, TIA, or systemic embolism. The primary safety endpoint was major bleeding (defined as bleeding at a critical anatomic site, symptomatic or clinically overt bleeding, or a decrease in hemoglobin > 2 g/dL). Secondary efficacy and safety outcomes included minor bleeding, acute myocardial infarction, deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and death. Outcomes were assessed within 37 days of the procedure.

The incidence of ATE was 0.4% (four events) in the no-bridging group vs 0.3% (three events) in the bridging group. Major bleeding occurred in 1.3% of the no-bridging group (12 events) and in 3.2% of the bridging group (29 events), indicating that no bridging was superior in terms of the major bleeding outcome (number needed to harm [NNH], 53; relative risk [RR], 0.41).

The no-bridging group also had significantly fewer minor bleeds in comparison to the bridging group (NNH, 11; 12% vs 20.9%). There were no differences between groups in other secondary outcomes.

Continue for what's new >>

WHAT’S NEW

High-quality evidence suggests it’s OK to stop warfarin before surgery

This is the largest good-quality study to evaluate perioperative bridging in patients with atrial fibrillation who were at low or moderate risk for ATE (CHADS2 score, 0-4). Previous studies suggested bridging increased bleeding and offered limited benefit for reducing the risk for ATE. However, this is the first study to include a large group of moderate-risk patients (CHADS2 score, 3-4). This trial provides high-quality evidence to support the practice of simply stopping warfarin in the perioperative period, rather than bridging with LMWH.

CAVEATS

Findings might not apply to patients at highest risk

Most patients in this study had a CHADS2 score ≤ 3. About 3% had a CHADS2 score ≥ 5. It’s not clear whether these findings apply to patients with a CHADS2 score of 5 or 6.

This trial categorized ATE risk using the CHADS2 score, rather than the CHA2DS2-VASc, which includes additional risk factors and may more accurately predict stroke risk. Both patients who received bridging therapy and those who did not had a lower rate of stroke than predicted by CHADS2. This may reflect a limit of the predictive value of CHADS2 but should not have affected the rate of bleeding or ATE outcomes in this study.

Continue for challenges to implementation >>

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Providers may hesitate to disregard current guidelines

Strokes are devastating events for patients, families, and clinicians, and they pose a greater risk for morbidity and mortality compared to bleeding. However, this study suggests patients who receive bridging have a higher risk for bleeding than stroke, which is in contrast to some providers’ experience and current recommendations.

A clinician caring for a patient who’s had a stroke may be inclined to recommend bridging despite the lack of efficacy and evidence of bleeding risk. Additionally, until guidelines reflect the most current research, clinicians may be reluctant to provide care in contrast to these recommendations.

REFERENCES

1. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Kaatz S, et al. Perioperative bridging anticoagulation in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:823-833.

2. Guyatt GH, Akl EA, Crowther M, et al; American College of Chest Physicians Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis Panel. Executive summary: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:7S-47S.

3. Clark NP, Witt DM, Davies LE, et al. Bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism and mortality risks during warfarin interruption for invasive procedures. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175:1163-1168.

4. Lip GY, Lane DA. Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: a systematic review.JAMA. 2015;313:1950-1962.

5. Douketis JD, Spyropoulos AC, Spencer FA, et al; American College of Chest Physicians. Perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141:e326S-e350S.

6. Miyasaka Y, Barnes ME, Gersh BJ, et al. Secular trends in incidence of atrial fibrillation in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1980 to 2000, and implications on the projections for future prevalence.Circulation. 2006;114:119-125.

7. Siegal D, Yudin J, Kaatz S, et al. Periprocedural heparin bridging in patients receiving vitamin K antagonists: systematic review and meta-analysis of bleeding and thromboembolic rates.Circulation. 2012;126:1630-1639.

8. Steinberg B, Peterson E, Kim S, et al; Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation Investigators and Patients. Use and outcomes associated with bridging during anticoagulation interruptions in patients with atrial fibrillation: findings from the Outcomes Registry for Better Informed Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (ORBIT-AF).Circulation. 2015;131:488-494.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2015. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice. 2015;64(12):794-795, 800.