User login

Sexual harassment is one of the most insidious and caustic evils in the US workplace—and it knows no bounds, judging by the rampant allegations throughout 2017 and into 2018. While sexual harassment affects both sexes, the majority of cases target women.

In a recent survey, the New York Times asked 615 men about objectionable behavior toward colleagues, including whether they have made uninvited attempts to stroke, fondle, or kiss a coworker. Twenty-five percent admitted to telling crude jokes or sharing inappropriate videos. Two percent said they had pressured people into sexual acts by offering rewards or threatening retaliation—that means 12 men admitted to this.1

Sadly, the health care industry is not immune from this corruption. In fact, sexual harassment is a major problem in health care—one that is particularly prevalent in nursing, according to Fiedler and Hamby.2 More than 50% of female nurses, physicians, and students report experiencing sexual harassment.3 And even that, I believe, is an underreported percentage.

Sexual harassment in the workplace includes any situation in which there is a demand for sexual favors in exchange for a job benefit or where an unwanted condition on any person’s employment is imposed because of that person’s sex. Since 1964, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (42 USC Sec.2000e-2[a]) has prohibited discrimination in places of employment based on an individual’s sex.4 In 1976, it was acknowledged that this also prohibits sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination. In 1991, amendments (42 USC Sec.1981 [a][1]) authorized compensatory and punitive damages as well as jury trials.5

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal agency that enforces Title VII, stipulates that

- Harassment can include unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment—but it does not have to be sexual in nature (eg, making offensive comments about women in general).

- Both women and men can be victims and harassers—and the victim and harasser can be the same sex.

- Harassment is illegal when it is so frequent or severe that it creates a hostile or offensive work environment, or when it results in an adverse employment decision (eg, the victim being fired or demoted).6

Although the EEOC guidelines are not law, they do guide the judicial interpretation of what constitutes sexual harassment. Sexual harassment is an increasing source of workplace lawsuits that often result in large judgments against employers. Clinicians can file class-action suits against hospitals and other institutions, and juries may render verdicts on harassment complaints to the tune of millions of dollars.

Unfortunately, it is common for workplace harassment to go unreported. According to the EEOC, standard responses to workplace sexual harassment include avoiding the harasser, denying or downplaying the gravity of the situation, or attempting to ignore, forget, or endure the behavior. The least common response is to take formal action—either by reporting it internally or filing a legal complaint. Further, roughly three of four individuals who experience harassment in the workplace never tell a supervisor, manager, or union representative due to fear of disbelief, inaction, blame, or social or professional retaliation.7

How can we, as clinicians, protect ourselves and others from this type of harassment? Establishing a strong zero-tolerance policy on sexual harassment and reporting unacceptable behavior is the only answer. I realize this is no easy issue, but we must be firm in our resolve. Although 2017 was a watershed year with “Silence Breaker” or “#MeToo,” there are still many voices not being heard.8

So, here is my request: If you have been directly affected by, or have observed, objectionable behavior that violates your organization’s policy or code of conduct (or your personal sense of decency), document the incident and report it. You may be hesitant; maybe you think the behavior is an isolated act, or maybe the offender is a well-liked colleague who usually acts professionally. But your role is not to decide whether this behavior is acute or chronic—the human resources department will determine that. Maybe you are reluctant to report harassment because you fear reprisal. This is understandable, but remember that intimidation allows the behavior to persist. If the incident was upsetting and objectionable, it needs to be reported—no matter what.

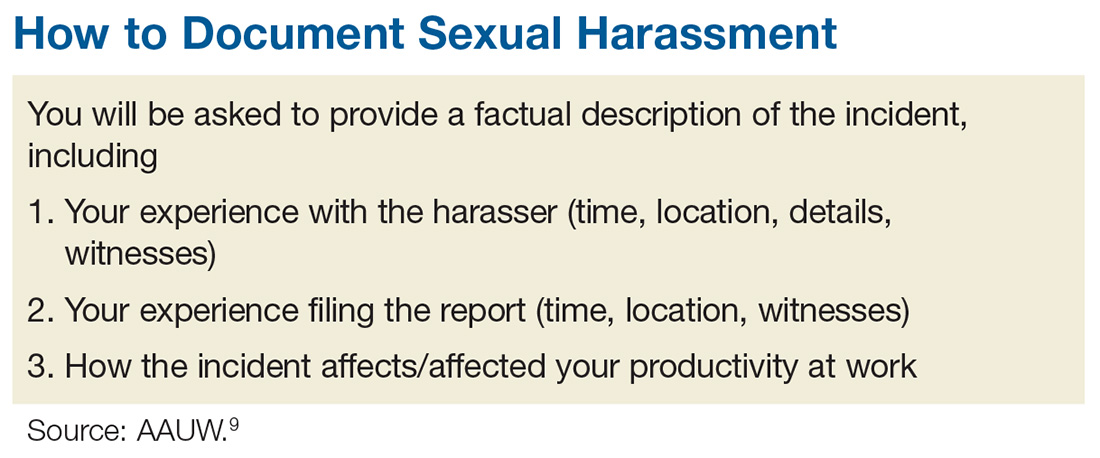

The process of documenting and reporting varies depending on your institution’s policy but typically involves writing a factual description of the incident, including the time, place, and a list of any witnesses (including patients). Make sure your report is objective, and include any effect the behavior has had on patient care. Document any verbal exchanges verbatim, if possible. File the report as soon as possible, and remember to document everything. Nothing is trivial when it comes to building a case against sexual harassment. After you document and report the incident, continue to act professionally.9

If you are unable to resolve a harassment-related issue through your employer’s internal procedure, you may need to pursue the matter via the EEOC or your state’s human rights or civil rights enforcement agency.10 But know that any time and effort you put into reporting this is worthwhile; predatory behavior often crosses the workplace to other social realms. The other people being affected will be grateful that you came forward.

Some of you may be reading this and thinking, “Easy for you to say, Randy. You are not the one being harassed!” I know. This is not an easy topic for anyone. I have been shocked and appalled by the level and prevalence of sexual harassment in the workplace. I was always taught (by my grandmother—thank you!) to respect women. My hope is that by introducing this sensitive topic, we can open the discussion and encourage everyone to speak up. Please share your thoughts, comments, and ideas with me at [email protected]—let’s start a conversation.

1. Patel JK, Griggs T, Cain Miller C. The UpShot: We asked 615 men about how they conduct themselves at work. The New York Times. December 28, 2017. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/12/28/upshot/sexual-harassment-survey-600-men.html. Accessed January 16, 2018.

2. Fiedler A, Hamby E. Sexual harassment in the workplace: nurses’ perceptions. J Nurs Adm. 2000;30(10):497-503.

3. Lockwood W. Sexual harassment in healthcare. www.rn.org/courses/coursematerial-236.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2018.

4. Legal Information Institute. 42 U.S. Code § 2000e–2 - Unlawful employment practices. www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/2000e-2. Accessed January 16, 2018.

5. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The Civil Rights Act of 1991. www.eeoc.gov/laws/statutes/cra-1991.cfm. Accessed January 16, 2018.

6. US EEOC. Sexual harassment. www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/sexual_harassment.cfm. Accessed January 16, 2018.

7. US EEOC. Select task force on the study of harassment in the workplace. June 2016. www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/task_force/harassment/report.cfm. Accessed January 16, 2018.

8. O’Brien SA, Carpenter J. 2017 was the year of (certain) women’s voices. December 28, 2017. www.ozarksfirst.com/news/business/2017-was-the-year-of-certain-womens-voices/889901636. Accessed January 16, 2018.

9. AAUW. Know your rights at work. www.aauw.org/what-we-do/legal-resources/know-your-rights-at-work/workplace-sexual-harassment/. Accessed January 16, 2018.

10. EEOC’s Charge Processing Procedures. http://employment.findlaw.com/employment-discrimination/eeoc-s-charge-processing-procedures.html. Accessed January 16, 2018.

Sexual harassment is one of the most insidious and caustic evils in the US workplace—and it knows no bounds, judging by the rampant allegations throughout 2017 and into 2018. While sexual harassment affects both sexes, the majority of cases target women.

In a recent survey, the New York Times asked 615 men about objectionable behavior toward colleagues, including whether they have made uninvited attempts to stroke, fondle, or kiss a coworker. Twenty-five percent admitted to telling crude jokes or sharing inappropriate videos. Two percent said they had pressured people into sexual acts by offering rewards or threatening retaliation—that means 12 men admitted to this.1

Sadly, the health care industry is not immune from this corruption. In fact, sexual harassment is a major problem in health care—one that is particularly prevalent in nursing, according to Fiedler and Hamby.2 More than 50% of female nurses, physicians, and students report experiencing sexual harassment.3 And even that, I believe, is an underreported percentage.

Sexual harassment in the workplace includes any situation in which there is a demand for sexual favors in exchange for a job benefit or where an unwanted condition on any person’s employment is imposed because of that person’s sex. Since 1964, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (42 USC Sec.2000e-2[a]) has prohibited discrimination in places of employment based on an individual’s sex.4 In 1976, it was acknowledged that this also prohibits sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination. In 1991, amendments (42 USC Sec.1981 [a][1]) authorized compensatory and punitive damages as well as jury trials.5

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal agency that enforces Title VII, stipulates that

- Harassment can include unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment—but it does not have to be sexual in nature (eg, making offensive comments about women in general).

- Both women and men can be victims and harassers—and the victim and harasser can be the same sex.

- Harassment is illegal when it is so frequent or severe that it creates a hostile or offensive work environment, or when it results in an adverse employment decision (eg, the victim being fired or demoted).6

Although the EEOC guidelines are not law, they do guide the judicial interpretation of what constitutes sexual harassment. Sexual harassment is an increasing source of workplace lawsuits that often result in large judgments against employers. Clinicians can file class-action suits against hospitals and other institutions, and juries may render verdicts on harassment complaints to the tune of millions of dollars.

Unfortunately, it is common for workplace harassment to go unreported. According to the EEOC, standard responses to workplace sexual harassment include avoiding the harasser, denying or downplaying the gravity of the situation, or attempting to ignore, forget, or endure the behavior. The least common response is to take formal action—either by reporting it internally or filing a legal complaint. Further, roughly three of four individuals who experience harassment in the workplace never tell a supervisor, manager, or union representative due to fear of disbelief, inaction, blame, or social or professional retaliation.7

How can we, as clinicians, protect ourselves and others from this type of harassment? Establishing a strong zero-tolerance policy on sexual harassment and reporting unacceptable behavior is the only answer. I realize this is no easy issue, but we must be firm in our resolve. Although 2017 was a watershed year with “Silence Breaker” or “#MeToo,” there are still many voices not being heard.8

So, here is my request: If you have been directly affected by, or have observed, objectionable behavior that violates your organization’s policy or code of conduct (or your personal sense of decency), document the incident and report it. You may be hesitant; maybe you think the behavior is an isolated act, or maybe the offender is a well-liked colleague who usually acts professionally. But your role is not to decide whether this behavior is acute or chronic—the human resources department will determine that. Maybe you are reluctant to report harassment because you fear reprisal. This is understandable, but remember that intimidation allows the behavior to persist. If the incident was upsetting and objectionable, it needs to be reported—no matter what.

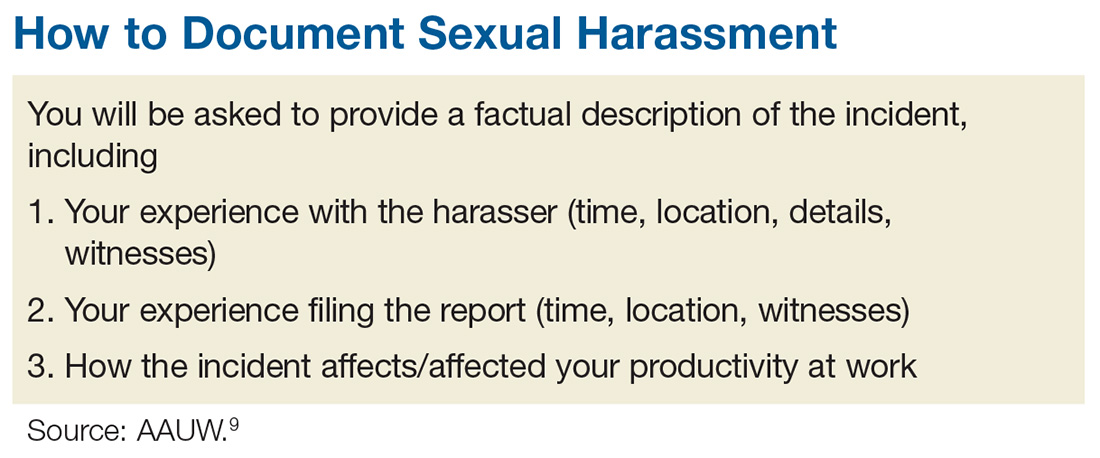

The process of documenting and reporting varies depending on your institution’s policy but typically involves writing a factual description of the incident, including the time, place, and a list of any witnesses (including patients). Make sure your report is objective, and include any effect the behavior has had on patient care. Document any verbal exchanges verbatim, if possible. File the report as soon as possible, and remember to document everything. Nothing is trivial when it comes to building a case against sexual harassment. After you document and report the incident, continue to act professionally.9

If you are unable to resolve a harassment-related issue through your employer’s internal procedure, you may need to pursue the matter via the EEOC or your state’s human rights or civil rights enforcement agency.10 But know that any time and effort you put into reporting this is worthwhile; predatory behavior often crosses the workplace to other social realms. The other people being affected will be grateful that you came forward.

Some of you may be reading this and thinking, “Easy for you to say, Randy. You are not the one being harassed!” I know. This is not an easy topic for anyone. I have been shocked and appalled by the level and prevalence of sexual harassment in the workplace. I was always taught (by my grandmother—thank you!) to respect women. My hope is that by introducing this sensitive topic, we can open the discussion and encourage everyone to speak up. Please share your thoughts, comments, and ideas with me at [email protected]—let’s start a conversation.

Sexual harassment is one of the most insidious and caustic evils in the US workplace—and it knows no bounds, judging by the rampant allegations throughout 2017 and into 2018. While sexual harassment affects both sexes, the majority of cases target women.

In a recent survey, the New York Times asked 615 men about objectionable behavior toward colleagues, including whether they have made uninvited attempts to stroke, fondle, or kiss a coworker. Twenty-five percent admitted to telling crude jokes or sharing inappropriate videos. Two percent said they had pressured people into sexual acts by offering rewards or threatening retaliation—that means 12 men admitted to this.1

Sadly, the health care industry is not immune from this corruption. In fact, sexual harassment is a major problem in health care—one that is particularly prevalent in nursing, according to Fiedler and Hamby.2 More than 50% of female nurses, physicians, and students report experiencing sexual harassment.3 And even that, I believe, is an underreported percentage.

Sexual harassment in the workplace includes any situation in which there is a demand for sexual favors in exchange for a job benefit or where an unwanted condition on any person’s employment is imposed because of that person’s sex. Since 1964, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act (42 USC Sec.2000e-2[a]) has prohibited discrimination in places of employment based on an individual’s sex.4 In 1976, it was acknowledged that this also prohibits sexual harassment as a form of sex discrimination. In 1991, amendments (42 USC Sec.1981 [a][1]) authorized compensatory and punitive damages as well as jury trials.5

The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), the federal agency that enforces Title VII, stipulates that

- Harassment can include unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical harassment—but it does not have to be sexual in nature (eg, making offensive comments about women in general).

- Both women and men can be victims and harassers—and the victim and harasser can be the same sex.

- Harassment is illegal when it is so frequent or severe that it creates a hostile or offensive work environment, or when it results in an adverse employment decision (eg, the victim being fired or demoted).6

Although the EEOC guidelines are not law, they do guide the judicial interpretation of what constitutes sexual harassment. Sexual harassment is an increasing source of workplace lawsuits that often result in large judgments against employers. Clinicians can file class-action suits against hospitals and other institutions, and juries may render verdicts on harassment complaints to the tune of millions of dollars.

Unfortunately, it is common for workplace harassment to go unreported. According to the EEOC, standard responses to workplace sexual harassment include avoiding the harasser, denying or downplaying the gravity of the situation, or attempting to ignore, forget, or endure the behavior. The least common response is to take formal action—either by reporting it internally or filing a legal complaint. Further, roughly three of four individuals who experience harassment in the workplace never tell a supervisor, manager, or union representative due to fear of disbelief, inaction, blame, or social or professional retaliation.7

How can we, as clinicians, protect ourselves and others from this type of harassment? Establishing a strong zero-tolerance policy on sexual harassment and reporting unacceptable behavior is the only answer. I realize this is no easy issue, but we must be firm in our resolve. Although 2017 was a watershed year with “Silence Breaker” or “#MeToo,” there are still many voices not being heard.8

So, here is my request: If you have been directly affected by, or have observed, objectionable behavior that violates your organization’s policy or code of conduct (or your personal sense of decency), document the incident and report it. You may be hesitant; maybe you think the behavior is an isolated act, or maybe the offender is a well-liked colleague who usually acts professionally. But your role is not to decide whether this behavior is acute or chronic—the human resources department will determine that. Maybe you are reluctant to report harassment because you fear reprisal. This is understandable, but remember that intimidation allows the behavior to persist. If the incident was upsetting and objectionable, it needs to be reported—no matter what.

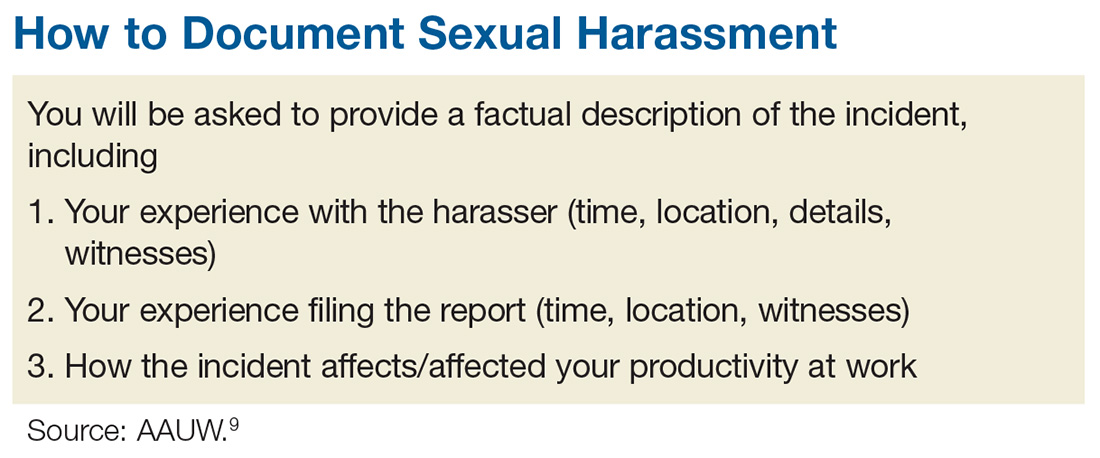

The process of documenting and reporting varies depending on your institution’s policy but typically involves writing a factual description of the incident, including the time, place, and a list of any witnesses (including patients). Make sure your report is objective, and include any effect the behavior has had on patient care. Document any verbal exchanges verbatim, if possible. File the report as soon as possible, and remember to document everything. Nothing is trivial when it comes to building a case against sexual harassment. After you document and report the incident, continue to act professionally.9

If you are unable to resolve a harassment-related issue through your employer’s internal procedure, you may need to pursue the matter via the EEOC or your state’s human rights or civil rights enforcement agency.10 But know that any time and effort you put into reporting this is worthwhile; predatory behavior often crosses the workplace to other social realms. The other people being affected will be grateful that you came forward.

Some of you may be reading this and thinking, “Easy for you to say, Randy. You are not the one being harassed!” I know. This is not an easy topic for anyone. I have been shocked and appalled by the level and prevalence of sexual harassment in the workplace. I was always taught (by my grandmother—thank you!) to respect women. My hope is that by introducing this sensitive topic, we can open the discussion and encourage everyone to speak up. Please share your thoughts, comments, and ideas with me at [email protected]—let’s start a conversation.

1. Patel JK, Griggs T, Cain Miller C. The UpShot: We asked 615 men about how they conduct themselves at work. The New York Times. December 28, 2017. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/12/28/upshot/sexual-harassment-survey-600-men.html. Accessed January 16, 2018.

2. Fiedler A, Hamby E. Sexual harassment in the workplace: nurses’ perceptions. J Nurs Adm. 2000;30(10):497-503.

3. Lockwood W. Sexual harassment in healthcare. www.rn.org/courses/coursematerial-236.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2018.

4. Legal Information Institute. 42 U.S. Code § 2000e–2 - Unlawful employment practices. www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/2000e-2. Accessed January 16, 2018.

5. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The Civil Rights Act of 1991. www.eeoc.gov/laws/statutes/cra-1991.cfm. Accessed January 16, 2018.

6. US EEOC. Sexual harassment. www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/sexual_harassment.cfm. Accessed January 16, 2018.

7. US EEOC. Select task force on the study of harassment in the workplace. June 2016. www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/task_force/harassment/report.cfm. Accessed January 16, 2018.

8. O’Brien SA, Carpenter J. 2017 was the year of (certain) women’s voices. December 28, 2017. www.ozarksfirst.com/news/business/2017-was-the-year-of-certain-womens-voices/889901636. Accessed January 16, 2018.

9. AAUW. Know your rights at work. www.aauw.org/what-we-do/legal-resources/know-your-rights-at-work/workplace-sexual-harassment/. Accessed January 16, 2018.

10. EEOC’s Charge Processing Procedures. http://employment.findlaw.com/employment-discrimination/eeoc-s-charge-processing-procedures.html. Accessed January 16, 2018.

1. Patel JK, Griggs T, Cain Miller C. The UpShot: We asked 615 men about how they conduct themselves at work. The New York Times. December 28, 2017. www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/12/28/upshot/sexual-harassment-survey-600-men.html. Accessed January 16, 2018.

2. Fiedler A, Hamby E. Sexual harassment in the workplace: nurses’ perceptions. J Nurs Adm. 2000;30(10):497-503.

3. Lockwood W. Sexual harassment in healthcare. www.rn.org/courses/coursematerial-236.pdf. Accessed January 16, 2018.

4. Legal Information Institute. 42 U.S. Code § 2000e–2 - Unlawful employment practices. www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/2000e-2. Accessed January 16, 2018.

5. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). The Civil Rights Act of 1991. www.eeoc.gov/laws/statutes/cra-1991.cfm. Accessed January 16, 2018.

6. US EEOC. Sexual harassment. www.eeoc.gov/laws/types/sexual_harassment.cfm. Accessed January 16, 2018.

7. US EEOC. Select task force on the study of harassment in the workplace. June 2016. www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/task_force/harassment/report.cfm. Accessed January 16, 2018.

8. O’Brien SA, Carpenter J. 2017 was the year of (certain) women’s voices. December 28, 2017. www.ozarksfirst.com/news/business/2017-was-the-year-of-certain-womens-voices/889901636. Accessed January 16, 2018.

9. AAUW. Know your rights at work. www.aauw.org/what-we-do/legal-resources/know-your-rights-at-work/workplace-sexual-harassment/. Accessed January 16, 2018.

10. EEOC’s Charge Processing Procedures. http://employment.findlaw.com/employment-discrimination/eeoc-s-charge-processing-procedures.html. Accessed January 16, 2018.