User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

‘Appreciate the editorials’

I appreciate Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial on the so-called abdominal brain (Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):10- 11 [http://bit.ly/1PcxFNP]). Current Psychiatry is a journal with useful reports of advances, reviews, and opinion of research and treatment in our specialty. The selections and editing are always pertinent and thoughtful.

I appreciate Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial on the so-called abdominal brain (Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):10- 11 [http://bit.ly/1PcxFNP]). Current Psychiatry is a journal with useful reports of advances, reviews, and opinion of research and treatment in our specialty. The selections and editing are always pertinent and thoughtful.

I appreciate Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial on the so-called abdominal brain (Current Psychiatry. 2015;14(5):10- 11 [http://bit.ly/1PcxFNP]). Current Psychiatry is a journal with useful reports of advances, reviews, and opinion of research and treatment in our specialty. The selections and editing are always pertinent and thoughtful.

Practical approaches to promoting brain health

More than once in his Current Psychiatry essays, Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, has stressed the seismic paradigmatic shifts in our understanding of mental illness and brain disease. He has highlighted the critical significance of processes of neurogenesis and neuroinflammation, yet little has been offered to practitioners in terms of practical approaches to promoting the brain health that he encourages.

Two of the most potent modalities for maintaining brain wellness and facilitating ongoing neurogenesis and synaptogenesis are exercise and nutrition—specifically, high-intensity interval training and a diet heavily, if not entirely, plant-based. The neuroprotective capabilities of mindfulness practice and its impact on prefrontal cortical regions also are relevant.

In society at large, it strikes me that physicians have not fared any better than the general population when it comes to maintaining a healthy diet and engaging in physical exercise. I encourage Dr. Nasrallah to continue addressing these themes, and to remind his audience of physicians to “heal thyself.”

More than once in his Current Psychiatry essays, Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, has stressed the seismic paradigmatic shifts in our understanding of mental illness and brain disease. He has highlighted the critical significance of processes of neurogenesis and neuroinflammation, yet little has been offered to practitioners in terms of practical approaches to promoting the brain health that he encourages.

Two of the most potent modalities for maintaining brain wellness and facilitating ongoing neurogenesis and synaptogenesis are exercise and nutrition—specifically, high-intensity interval training and a diet heavily, if not entirely, plant-based. The neuroprotective capabilities of mindfulness practice and its impact on prefrontal cortical regions also are relevant.

In society at large, it strikes me that physicians have not fared any better than the general population when it comes to maintaining a healthy diet and engaging in physical exercise. I encourage Dr. Nasrallah to continue addressing these themes, and to remind his audience of physicians to “heal thyself.”

More than once in his Current Psychiatry essays, Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, has stressed the seismic paradigmatic shifts in our understanding of mental illness and brain disease. He has highlighted the critical significance of processes of neurogenesis and neuroinflammation, yet little has been offered to practitioners in terms of practical approaches to promoting the brain health that he encourages.

Two of the most potent modalities for maintaining brain wellness and facilitating ongoing neurogenesis and synaptogenesis are exercise and nutrition—specifically, high-intensity interval training and a diet heavily, if not entirely, plant-based. The neuroprotective capabilities of mindfulness practice and its impact on prefrontal cortical regions also are relevant.

In society at large, it strikes me that physicians have not fared any better than the general population when it comes to maintaining a healthy diet and engaging in physical exercise. I encourage Dr. Nasrallah to continue addressing these themes, and to remind his audience of physicians to “heal thyself.”

Urine drug screens: When might a test result be false-positive?

Mr. L, age 35, has an appointment at a mental health clinic for ongoing treatment of depression. His medication list includes atorvastatin, bupropion, lisinopril, and cranberry capsules for non-descriptive urinary issues. He has been treated for some time at a different outpatient facility; however he recently moved and changed clinics.

At this visit, his first, Mr. L receives a full physical exam, including a urine drug screen point-of-care (POC) test. He informs the nurse that he has an extensive history of drug abuse: “You name it, I’ve done it.” Although he experimented with many illicit substances, he acknowledges that “downers” were his favorite. He believes that his drug abuse could have caused his depression, but is proud to declare that he has been “clean” for 12 months and his depression is approaching remission.

However, the urine drug screen is positive for amphetamines. Mr. L vehemently swears that the test must be wrong, restating that he has been clean for 12 months. “Besides, I don’t even like ‘uppers’!” Because of Mr. L’s insistence, the clinician does a brief literature search about false-positive results in urine drug screening, which shows that, rarely, bupropion can trigger a false positive in the amphetamine immunoassay.

Could this be a false-positive result? Or is Mr. L not telling the truth?

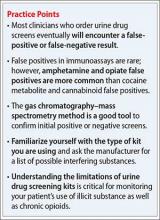

Because no clinical lab test is perfect, any clinician who runs urine drug screens will encounter a false-positive result. (See the Box,1-3 for discussion of false negatives.) Understanding how each test works—and potential sources of error— can help you evaluate test results and determine the best course of action.

There are 2 main methods involved in urine drug testing: in-office (POC) urine testing and laboratory-based testing. This article describes the differences between these tests and summarizes the potential for false-positive results.

In-office urine testing

POC tests in urine drug screens use a technique called “immunoassay,” which is quantitative and generally will detect the agent in urine for only 3 to 7 days after ingestion.4 This test relies on the principle of competitive binding: If a parent drug or metabolite is present in urine, it will bind to a specific antibody site on the test strip and produce a positive result.5 Other compounds that are similarly “shaped” on a molecular level also can bind to these antibody sites when present in sufficient quantity, producing a “cross reaction,” also called a “false-positive” result. The Table6 lists agents that can cross-react with immunoassay tests. In addition to the cross-reaction, false positives also can occur because of technician or clerical error— making it important to review the process by which the specimen was obtained and tested if a false-positive result is suspected, as in the case described here.7

Different POC tests can have varying cross-reactivity patterns, based on the antibody used.8 In general, false positives in immunoassays are rare, but amphetamine and opiate false positives are more common than cocaine metabolite and cannabinoid false positives.9 The odds of a false positive vary, depending on the specificity of the immunoassay used and the substance under detection.6

A study that analyzed 10,000 POC urine drug screens found that 362 specimens tested positive for amphetamines, but that 128 of those did not test positive for amphetamines using more sensitive tests.10 Of these 128 false positives reported, 53 patients were taking bupropion at the time of the test.10 Therefore, clinicians should do a thorough patient medication review at the time of POC urine drug testing. In addition, consider identifying which type of test you are using at your practice site, and ask the manufacturer or lab to provide a list of known possible false positives.

Laboratory-based GC–MS testing

If a false positive is suspected on a POC immunoassay-based urine drug screen, results can be confirmed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Although GC–MS is more accurate than an immunoassay, it also is more expensive and time-consuming.9

GC–MS breaks down a specimen into ionized fragments and separates them based on their mass–charge ratio. Because of this, GC–MS is able to identify the presence of a specific drug (eg, oxycodone) instead of a broad class (eg, opioid). The GC–MS method is a good tool to confirm initial positive screens when their integrity is in question because, unlike POC tests used during an office visit, GC–MS is not influenced by cross-reacting compounds.11-13

GC–MS is not error-free, however. For example, heroin and hydrocodone are metabolized into morphine and hydromorphone, respectively. Depending on when the specimen was collected, the metabolites, not the parents, might be the compounds identified, which might produce confusing results.

Clinical recommendations

When a POC drug screen is positive, confirming the result with GC–MS is good clinical practice. False positives can strain the relationship between patient and provider, thus compromising care. Examining the procedures that were used to obtain the specimen, as well as double-checking POC test results, is, when appropriate, good medicine.

CASE CONTINUED

Because Mr. L is adamant about his sobriety and the fact that his drugs of choice were sedatives, not stimulants, the clinician orders a second drug screen by GC–MS. The second screen is negative for substances of abuse; Mr. L’s clinician concludes that bupropion produced a false-positive result on the POC urine drug screen, confirming Mr. L’s assertions.

Related Resources

• Saitman A, Park HD, Fitzgerald RL. False-positive interferences of common urine drug screen immunoassays: a review. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38(7):387-396.

• Tenore PL. Advanced urine toxicology testing. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(4):436-448.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symadine, Symmetrel

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Brompheniramine • Dimetane

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Cyclobenzaprine • Amrix, Flexeril

Cyproheptadine • Periactin

Desipramine • Nopramin

Desoxyephedrine • Desoxyn

Dextromethorphan • Delsym, Robitussin

Dicyclomine • Bentyl, Dicyclocot

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl, Unisom

Doxylamine • Robitussin, NyQuil

Dronabinol • Marinol

Efavirenz • Sustiva

Ephedrine • Mistol, Va-Tro-Nol

Ergotamine • Ergomar, Cafergot

Hydrocodone • Vicodin

Hydromophone • Dilaudid, Palladone

Hydroxyzine • Atarax, Vistaril

Isometheptene • Amidrine, Migrend

Isoxsuprine • Vasodilan, Vasoprine

Ketoprofen • Orudis, Oruvail

Labetalol • Normodyne, Trandate

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Meperidine • Demerol

Naproxen • Aleve, Naprosyn

Oxaprozin • Daypro

Oxycodone • Oxycontin, Percocet, Percodan, Roxicodone

Phentermine • Adipex, Phentrol

Phenylephrine • Sudafed PE, Neo-Synephrine

Piroxicam • Feldene

Promethazine • Phenergan

Pseudoephedrine • Sudafed, Dimetapp

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Ranitidine • Zantac

Rifampin • Rifadin, Rimactane

Selegiline • EMSAM

Sertraline • Zoloft

Sulindac • Clinoril

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Tolmetin • Tolectin

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Trimethobenzamide • Benzacot, Tigan

Trimipramine • Surmontil

Verapamil • Calan, Isoptin

1. Cobaugh DJ, Gainor C, Gaston CL, et al. The opioid abuse and misuse epidemic: implications for pharmacists in hospitals and health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(18):1539-1554.

2. Gilbert JW, Wheeler GR, Mick GE, et al. Importance of urine drug testing in the treatment of chronic noncancer pain: implications of recent medicare policy changes in Kentucky. Pain Physician. 2010;13(2):167-186.

3. Michna E, Jamison RN, Pham LD, et al. Urine toxicology screening among chronic pain patients on opioid therapy: frequency and predictability of abnormal findings. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(2):173-179.

4. U.S. Department of Justice. Fact sheet: drug testing in the criminal justice system. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/dtest. pdf. Published March 1992. Accessed July 29, 2015.

5. Australian Diagnostic Services. Technical information: testing principle’s. http://www.australiandrugtesting. com/#!technical-info/c14h4. Accessed November 5, 2014.

6. University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy. What drugs are likely to interfere with urine drug screens? http://dig.pharm.uic.edu/faq/2011/Feb/faq1.aspx. Accessed November 5, 2014.

7. Wolff K, Farrell M, Marsden J, et al. A review of biological indicators of illicit drug use, practical considerations and clinical usefulness. Addiction. 1999;94(9):1279-1298.

8. Gourlay D, Heit H, Caplan YH. Urine drug testing in primary care – dispelling the myths & designing strategies. PharmaCom Group. http://www.mc.uky.edu/equip-4-pcps/documents/ section8/urine%20drug%20testing%20in%20clinical%20 practice.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2015.

9. Standridge JB, Adams SM, Zotos AP. Urine drug screen: a valuable office procedure. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(5): 635-640.

10. Casey ER, Scott MG, Tang S, et al. Frequency of false positive amphetamine screens due to bupropion using the Syva EMIT II immunoassay. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7(2):105-108.

11. Casavant MJ. Urine drug screening in adolescents. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2002;49(2):317-327.

12. Shults TF. The medical review officer handbook. 7th ed. Chapel Hill, NC: Quadrangle Research; 1999.

13. Baden LR, Horowitz G, Jacoby H, et al. Quinolones and false-positive urine screening for opiates by immunoassay technology. JAMA. 2001;286(24):3115-3119.

Mr. L, age 35, has an appointment at a mental health clinic for ongoing treatment of depression. His medication list includes atorvastatin, bupropion, lisinopril, and cranberry capsules for non-descriptive urinary issues. He has been treated for some time at a different outpatient facility; however he recently moved and changed clinics.

At this visit, his first, Mr. L receives a full physical exam, including a urine drug screen point-of-care (POC) test. He informs the nurse that he has an extensive history of drug abuse: “You name it, I’ve done it.” Although he experimented with many illicit substances, he acknowledges that “downers” were his favorite. He believes that his drug abuse could have caused his depression, but is proud to declare that he has been “clean” for 12 months and his depression is approaching remission.

However, the urine drug screen is positive for amphetamines. Mr. L vehemently swears that the test must be wrong, restating that he has been clean for 12 months. “Besides, I don’t even like ‘uppers’!” Because of Mr. L’s insistence, the clinician does a brief literature search about false-positive results in urine drug screening, which shows that, rarely, bupropion can trigger a false positive in the amphetamine immunoassay.

Could this be a false-positive result? Or is Mr. L not telling the truth?

Because no clinical lab test is perfect, any clinician who runs urine drug screens will encounter a false-positive result. (See the Box,1-3 for discussion of false negatives.) Understanding how each test works—and potential sources of error— can help you evaluate test results and determine the best course of action.

There are 2 main methods involved in urine drug testing: in-office (POC) urine testing and laboratory-based testing. This article describes the differences between these tests and summarizes the potential for false-positive results.

In-office urine testing

POC tests in urine drug screens use a technique called “immunoassay,” which is quantitative and generally will detect the agent in urine for only 3 to 7 days after ingestion.4 This test relies on the principle of competitive binding: If a parent drug or metabolite is present in urine, it will bind to a specific antibody site on the test strip and produce a positive result.5 Other compounds that are similarly “shaped” on a molecular level also can bind to these antibody sites when present in sufficient quantity, producing a “cross reaction,” also called a “false-positive” result. The Table6 lists agents that can cross-react with immunoassay tests. In addition to the cross-reaction, false positives also can occur because of technician or clerical error— making it important to review the process by which the specimen was obtained and tested if a false-positive result is suspected, as in the case described here.7

Different POC tests can have varying cross-reactivity patterns, based on the antibody used.8 In general, false positives in immunoassays are rare, but amphetamine and opiate false positives are more common than cocaine metabolite and cannabinoid false positives.9 The odds of a false positive vary, depending on the specificity of the immunoassay used and the substance under detection.6

A study that analyzed 10,000 POC urine drug screens found that 362 specimens tested positive for amphetamines, but that 128 of those did not test positive for amphetamines using more sensitive tests.10 Of these 128 false positives reported, 53 patients were taking bupropion at the time of the test.10 Therefore, clinicians should do a thorough patient medication review at the time of POC urine drug testing. In addition, consider identifying which type of test you are using at your practice site, and ask the manufacturer or lab to provide a list of known possible false positives.

Laboratory-based GC–MS testing

If a false positive is suspected on a POC immunoassay-based urine drug screen, results can be confirmed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Although GC–MS is more accurate than an immunoassay, it also is more expensive and time-consuming.9

GC–MS breaks down a specimen into ionized fragments and separates them based on their mass–charge ratio. Because of this, GC–MS is able to identify the presence of a specific drug (eg, oxycodone) instead of a broad class (eg, opioid). The GC–MS method is a good tool to confirm initial positive screens when their integrity is in question because, unlike POC tests used during an office visit, GC–MS is not influenced by cross-reacting compounds.11-13

GC–MS is not error-free, however. For example, heroin and hydrocodone are metabolized into morphine and hydromorphone, respectively. Depending on when the specimen was collected, the metabolites, not the parents, might be the compounds identified, which might produce confusing results.

Clinical recommendations

When a POC drug screen is positive, confirming the result with GC–MS is good clinical practice. False positives can strain the relationship between patient and provider, thus compromising care. Examining the procedures that were used to obtain the specimen, as well as double-checking POC test results, is, when appropriate, good medicine.

CASE CONTINUED

Because Mr. L is adamant about his sobriety and the fact that his drugs of choice were sedatives, not stimulants, the clinician orders a second drug screen by GC–MS. The second screen is negative for substances of abuse; Mr. L’s clinician concludes that bupropion produced a false-positive result on the POC urine drug screen, confirming Mr. L’s assertions.

Related Resources

• Saitman A, Park HD, Fitzgerald RL. False-positive interferences of common urine drug screen immunoassays: a review. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38(7):387-396.

• Tenore PL. Advanced urine toxicology testing. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(4):436-448.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symadine, Symmetrel

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Brompheniramine • Dimetane

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Cyclobenzaprine • Amrix, Flexeril

Cyproheptadine • Periactin

Desipramine • Nopramin

Desoxyephedrine • Desoxyn

Dextromethorphan • Delsym, Robitussin

Dicyclomine • Bentyl, Dicyclocot

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl, Unisom

Doxylamine • Robitussin, NyQuil

Dronabinol • Marinol

Efavirenz • Sustiva

Ephedrine • Mistol, Va-Tro-Nol

Ergotamine • Ergomar, Cafergot

Hydrocodone • Vicodin

Hydromophone • Dilaudid, Palladone

Hydroxyzine • Atarax, Vistaril

Isometheptene • Amidrine, Migrend

Isoxsuprine • Vasodilan, Vasoprine

Ketoprofen • Orudis, Oruvail

Labetalol • Normodyne, Trandate

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Meperidine • Demerol

Naproxen • Aleve, Naprosyn

Oxaprozin • Daypro

Oxycodone • Oxycontin, Percocet, Percodan, Roxicodone

Phentermine • Adipex, Phentrol

Phenylephrine • Sudafed PE, Neo-Synephrine

Piroxicam • Feldene

Promethazine • Phenergan

Pseudoephedrine • Sudafed, Dimetapp

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Ranitidine • Zantac

Rifampin • Rifadin, Rimactane

Selegiline • EMSAM

Sertraline • Zoloft

Sulindac • Clinoril

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Tolmetin • Tolectin

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Trimethobenzamide • Benzacot, Tigan

Trimipramine • Surmontil

Verapamil • Calan, Isoptin

Mr. L, age 35, has an appointment at a mental health clinic for ongoing treatment of depression. His medication list includes atorvastatin, bupropion, lisinopril, and cranberry capsules for non-descriptive urinary issues. He has been treated for some time at a different outpatient facility; however he recently moved and changed clinics.

At this visit, his first, Mr. L receives a full physical exam, including a urine drug screen point-of-care (POC) test. He informs the nurse that he has an extensive history of drug abuse: “You name it, I’ve done it.” Although he experimented with many illicit substances, he acknowledges that “downers” were his favorite. He believes that his drug abuse could have caused his depression, but is proud to declare that he has been “clean” for 12 months and his depression is approaching remission.

However, the urine drug screen is positive for amphetamines. Mr. L vehemently swears that the test must be wrong, restating that he has been clean for 12 months. “Besides, I don’t even like ‘uppers’!” Because of Mr. L’s insistence, the clinician does a brief literature search about false-positive results in urine drug screening, which shows that, rarely, bupropion can trigger a false positive in the amphetamine immunoassay.

Could this be a false-positive result? Or is Mr. L not telling the truth?

Because no clinical lab test is perfect, any clinician who runs urine drug screens will encounter a false-positive result. (See the Box,1-3 for discussion of false negatives.) Understanding how each test works—and potential sources of error— can help you evaluate test results and determine the best course of action.

There are 2 main methods involved in urine drug testing: in-office (POC) urine testing and laboratory-based testing. This article describes the differences between these tests and summarizes the potential for false-positive results.

In-office urine testing

POC tests in urine drug screens use a technique called “immunoassay,” which is quantitative and generally will detect the agent in urine for only 3 to 7 days after ingestion.4 This test relies on the principle of competitive binding: If a parent drug or metabolite is present in urine, it will bind to a specific antibody site on the test strip and produce a positive result.5 Other compounds that are similarly “shaped” on a molecular level also can bind to these antibody sites when present in sufficient quantity, producing a “cross reaction,” also called a “false-positive” result. The Table6 lists agents that can cross-react with immunoassay tests. In addition to the cross-reaction, false positives also can occur because of technician or clerical error— making it important to review the process by which the specimen was obtained and tested if a false-positive result is suspected, as in the case described here.7

Different POC tests can have varying cross-reactivity patterns, based on the antibody used.8 In general, false positives in immunoassays are rare, but amphetamine and opiate false positives are more common than cocaine metabolite and cannabinoid false positives.9 The odds of a false positive vary, depending on the specificity of the immunoassay used and the substance under detection.6

A study that analyzed 10,000 POC urine drug screens found that 362 specimens tested positive for amphetamines, but that 128 of those did not test positive for amphetamines using more sensitive tests.10 Of these 128 false positives reported, 53 patients were taking bupropion at the time of the test.10 Therefore, clinicians should do a thorough patient medication review at the time of POC urine drug testing. In addition, consider identifying which type of test you are using at your practice site, and ask the manufacturer or lab to provide a list of known possible false positives.

Laboratory-based GC–MS testing

If a false positive is suspected on a POC immunoassay-based urine drug screen, results can be confirmed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). Although GC–MS is more accurate than an immunoassay, it also is more expensive and time-consuming.9

GC–MS breaks down a specimen into ionized fragments and separates them based on their mass–charge ratio. Because of this, GC–MS is able to identify the presence of a specific drug (eg, oxycodone) instead of a broad class (eg, opioid). The GC–MS method is a good tool to confirm initial positive screens when their integrity is in question because, unlike POC tests used during an office visit, GC–MS is not influenced by cross-reacting compounds.11-13

GC–MS is not error-free, however. For example, heroin and hydrocodone are metabolized into morphine and hydromorphone, respectively. Depending on when the specimen was collected, the metabolites, not the parents, might be the compounds identified, which might produce confusing results.

Clinical recommendations

When a POC drug screen is positive, confirming the result with GC–MS is good clinical practice. False positives can strain the relationship between patient and provider, thus compromising care. Examining the procedures that were used to obtain the specimen, as well as double-checking POC test results, is, when appropriate, good medicine.

CASE CONTINUED

Because Mr. L is adamant about his sobriety and the fact that his drugs of choice were sedatives, not stimulants, the clinician orders a second drug screen by GC–MS. The second screen is negative for substances of abuse; Mr. L’s clinician concludes that bupropion produced a false-positive result on the POC urine drug screen, confirming Mr. L’s assertions.

Related Resources

• Saitman A, Park HD, Fitzgerald RL. False-positive interferences of common urine drug screen immunoassays: a review. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38(7):387-396.

• Tenore PL. Advanced urine toxicology testing. J Addict Dis. 2010;29(4):436-448.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symadine, Symmetrel

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Brompheniramine • Dimetane

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Cyclobenzaprine • Amrix, Flexeril

Cyproheptadine • Periactin

Desipramine • Nopramin

Desoxyephedrine • Desoxyn

Dextromethorphan • Delsym, Robitussin

Dicyclomine • Bentyl, Dicyclocot

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl, Unisom

Doxylamine • Robitussin, NyQuil

Dronabinol • Marinol

Efavirenz • Sustiva

Ephedrine • Mistol, Va-Tro-Nol

Ergotamine • Ergomar, Cafergot

Hydrocodone • Vicodin

Hydromophone • Dilaudid, Palladone

Hydroxyzine • Atarax, Vistaril

Isometheptene • Amidrine, Migrend

Isoxsuprine • Vasodilan, Vasoprine

Ketoprofen • Orudis, Oruvail

Labetalol • Normodyne, Trandate

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Meperidine • Demerol

Naproxen • Aleve, Naprosyn

Oxaprozin • Daypro

Oxycodone • Oxycontin, Percocet, Percodan, Roxicodone

Phentermine • Adipex, Phentrol

Phenylephrine • Sudafed PE, Neo-Synephrine

Piroxicam • Feldene

Promethazine • Phenergan

Pseudoephedrine • Sudafed, Dimetapp

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Ranitidine • Zantac

Rifampin • Rifadin, Rimactane

Selegiline • EMSAM

Sertraline • Zoloft

Sulindac • Clinoril

Sumatriptan • Imitrex

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Tolmetin • Tolectin

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Trimethobenzamide • Benzacot, Tigan

Trimipramine • Surmontil

Verapamil • Calan, Isoptin

1. Cobaugh DJ, Gainor C, Gaston CL, et al. The opioid abuse and misuse epidemic: implications for pharmacists in hospitals and health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(18):1539-1554.

2. Gilbert JW, Wheeler GR, Mick GE, et al. Importance of urine drug testing in the treatment of chronic noncancer pain: implications of recent medicare policy changes in Kentucky. Pain Physician. 2010;13(2):167-186.

3. Michna E, Jamison RN, Pham LD, et al. Urine toxicology screening among chronic pain patients on opioid therapy: frequency and predictability of abnormal findings. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(2):173-179.

4. U.S. Department of Justice. Fact sheet: drug testing in the criminal justice system. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/dtest. pdf. Published March 1992. Accessed July 29, 2015.

5. Australian Diagnostic Services. Technical information: testing principle’s. http://www.australiandrugtesting. com/#!technical-info/c14h4. Accessed November 5, 2014.

6. University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy. What drugs are likely to interfere with urine drug screens? http://dig.pharm.uic.edu/faq/2011/Feb/faq1.aspx. Accessed November 5, 2014.

7. Wolff K, Farrell M, Marsden J, et al. A review of biological indicators of illicit drug use, practical considerations and clinical usefulness. Addiction. 1999;94(9):1279-1298.

8. Gourlay D, Heit H, Caplan YH. Urine drug testing in primary care – dispelling the myths & designing strategies. PharmaCom Group. http://www.mc.uky.edu/equip-4-pcps/documents/ section8/urine%20drug%20testing%20in%20clinical%20 practice.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2015.

9. Standridge JB, Adams SM, Zotos AP. Urine drug screen: a valuable office procedure. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(5): 635-640.

10. Casey ER, Scott MG, Tang S, et al. Frequency of false positive amphetamine screens due to bupropion using the Syva EMIT II immunoassay. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7(2):105-108.

11. Casavant MJ. Urine drug screening in adolescents. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2002;49(2):317-327.

12. Shults TF. The medical review officer handbook. 7th ed. Chapel Hill, NC: Quadrangle Research; 1999.

13. Baden LR, Horowitz G, Jacoby H, et al. Quinolones and false-positive urine screening for opiates by immunoassay technology. JAMA. 2001;286(24):3115-3119.

1. Cobaugh DJ, Gainor C, Gaston CL, et al. The opioid abuse and misuse epidemic: implications for pharmacists in hospitals and health systems. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2014;71(18):1539-1554.

2. Gilbert JW, Wheeler GR, Mick GE, et al. Importance of urine drug testing in the treatment of chronic noncancer pain: implications of recent medicare policy changes in Kentucky. Pain Physician. 2010;13(2):167-186.

3. Michna E, Jamison RN, Pham LD, et al. Urine toxicology screening among chronic pain patients on opioid therapy: frequency and predictability of abnormal findings. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(2):173-179.

4. U.S. Department of Justice. Fact sheet: drug testing in the criminal justice system. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/dtest. pdf. Published March 1992. Accessed July 29, 2015.

5. Australian Diagnostic Services. Technical information: testing principle’s. http://www.australiandrugtesting. com/#!technical-info/c14h4. Accessed November 5, 2014.

6. University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy. What drugs are likely to interfere with urine drug screens? http://dig.pharm.uic.edu/faq/2011/Feb/faq1.aspx. Accessed November 5, 2014.

7. Wolff K, Farrell M, Marsden J, et al. A review of biological indicators of illicit drug use, practical considerations and clinical usefulness. Addiction. 1999;94(9):1279-1298.

8. Gourlay D, Heit H, Caplan YH. Urine drug testing in primary care – dispelling the myths & designing strategies. PharmaCom Group. http://www.mc.uky.edu/equip-4-pcps/documents/ section8/urine%20drug%20testing%20in%20clinical%20 practice.pdf. Accessed August 6, 2015.

9. Standridge JB, Adams SM, Zotos AP. Urine drug screen: a valuable office procedure. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(5): 635-640.

10. Casey ER, Scott MG, Tang S, et al. Frequency of false positive amphetamine screens due to bupropion using the Syva EMIT II immunoassay. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7(2):105-108.

11. Casavant MJ. Urine drug screening in adolescents. Pediatr Clin N Am. 2002;49(2):317-327.

12. Shults TF. The medical review officer handbook. 7th ed. Chapel Hill, NC: Quadrangle Research; 1999.

13. Baden LR, Horowitz G, Jacoby H, et al. Quinolones and false-positive urine screening for opiates by immunoassay technology. JAMA. 2001;286(24):3115-3119.

Needed: A biopsychosocial ‘therapeutic placenta’ for people with schizophrenia

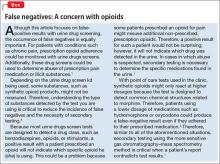

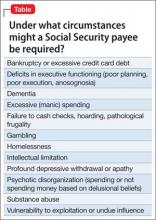

Consider stroke. Guidelines for acute treatment, access, intervention, prevention of post-hospitalization relapse, and rehabilitation are extensively spelled out and implemented.1 (The Box outlines Mayo Clinic guidelines for stroke management, as a demonstration of the comprehensiveness of the approach.)

Schizophrenia and related severe mental illnesses (SMI) need a similar all-inclusive system that seamlessly provides the myriad components of care needed for this vulnerable population. I propose the term “therapeutic placenta” to describe what people with a disabling SMI brain disorder deserve, just as stroke patients do.

Closing asylums: Psychosocial abruptio placentae

In a past Editorial,2 I described the appalling consequences of eliminating the asylum, an entity that I believe must be a key component of the SMI therapeutic placenta. The asylum is to schizophrenia as the skilled nursing home is to stroke. SMI patients suffered extensively when asylums were shut down; they lost a medical refuge with psychiatric and primary care, nursing and social work support, occupational and recreational therapies, and work therapy (farming, carpentry shop, cafeteria, laundry, etc.). For SMI, these services are the psychosocial counterpart of various physical rehabilitation therapies for stroke patients that no one would ever dare to eliminate.

Persons with schizophrenia and other SMI have suffered tragically with rupture of the main components of the therapeutic placenta that existed for decades before the advent of medications. The massive homelessness, widespread incarceration, persistent poverty, rampant access to alcohol and drugs of abuse, early death due to lack of primary care, and absence of meaningful opportunities for vocational rehabilitation are all consequences of a neglectful society that refuses to fund a therapeutic placenta for the SMI population.

The public mental health system in charge of SMI patients is broken, disconnected, and failing to provide the necessary components of a therapeutic placenta. It should not be surprising to witness the terribly stressful life and premature mortality of SMI patients, who are modern-day les misérables.

The Table lists what I consider to be the necessary spectrum of health care services through the life of an SMI patient that an optimal therapeutic placenta must provide until an effective prevention or a cure for SMI is discovered.

Reasons to be hopeful

Admittedly, encouraging steps are being made toward establishing a therapeutic placenta for SMI:

The RAISE Study3and Navigate Program4 demonstrate that implementing a comprehensive program of acute treatment and psychosocial interventions and rehabilitation yields better outcomes in SMI.

The Institute of Medicine released a landmark report on psychosocial interventions for mental illness and substance abuse disorders. It outlines a new model for establishing the effectiveness of intervention and the implementation of psychosocial strategies in clinical practice.5

The 21st Century Cures Act, if passed by Congress and signed by the President, will increase funding for the National Institutes of Health, which in turn will bolster the budgets of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and enhance the chances of discovering better treatments and prevention of SMI.

The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, more directly relevant to mental health and psychiatry, proposes, if passed, to:

• enhance evidence-based and scientifically validated interventions in the public sector

• raise the profile of mental health within the federal government by creating a position of Assistant Secretary for Mental Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, who will have oversight of both research and mental health care within the federal government.

Unacceptable disparity must be remedied

Planning an effective therapeutic placenta is imperative if health care for SMI patients is to approach the comprehensive spectrum of treatment, rehabilitation, and prevention available to stroke patients. Although stroke is regarded as a sensory-motor brain disorder, it is also associated with mental symptoms, just as schizophrenia is associated with sensory-motor symptoms. Both are disabling brain disorders: one, physically and cognitively; the other, mentally and socially. Both require a therapeutic placenta: Stroke is supported by one; schizophrenia is not. This is an unacceptable disparity that must be addressed—soon.

1. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bring back the asylums? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):19-20.

3. Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. The RAISE early treatment program for first-episode psychosis: background, rationale, and study design. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):240-246.

4. Mueser KT, Penn DL, Addington J, et al. The NAVIGATE program for first-episode psychosis: rationale, overview, and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):680-690.

5. The National Academy of Sciences. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, DC. http:// iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2015/ Psychosocial-Interventions-Mental-Substance- Abuse-Disorders.aspx. Published July 14, 2015. Accessed September 3, 2015.

Consider stroke. Guidelines for acute treatment, access, intervention, prevention of post-hospitalization relapse, and rehabilitation are extensively spelled out and implemented.1 (The Box outlines Mayo Clinic guidelines for stroke management, as a demonstration of the comprehensiveness of the approach.)

Schizophrenia and related severe mental illnesses (SMI) need a similar all-inclusive system that seamlessly provides the myriad components of care needed for this vulnerable population. I propose the term “therapeutic placenta” to describe what people with a disabling SMI brain disorder deserve, just as stroke patients do.

Closing asylums: Psychosocial abruptio placentae

In a past Editorial,2 I described the appalling consequences of eliminating the asylum, an entity that I believe must be a key component of the SMI therapeutic placenta. The asylum is to schizophrenia as the skilled nursing home is to stroke. SMI patients suffered extensively when asylums were shut down; they lost a medical refuge with psychiatric and primary care, nursing and social work support, occupational and recreational therapies, and work therapy (farming, carpentry shop, cafeteria, laundry, etc.). For SMI, these services are the psychosocial counterpart of various physical rehabilitation therapies for stroke patients that no one would ever dare to eliminate.

Persons with schizophrenia and other SMI have suffered tragically with rupture of the main components of the therapeutic placenta that existed for decades before the advent of medications. The massive homelessness, widespread incarceration, persistent poverty, rampant access to alcohol and drugs of abuse, early death due to lack of primary care, and absence of meaningful opportunities for vocational rehabilitation are all consequences of a neglectful society that refuses to fund a therapeutic placenta for the SMI population.

The public mental health system in charge of SMI patients is broken, disconnected, and failing to provide the necessary components of a therapeutic placenta. It should not be surprising to witness the terribly stressful life and premature mortality of SMI patients, who are modern-day les misérables.

The Table lists what I consider to be the necessary spectrum of health care services through the life of an SMI patient that an optimal therapeutic placenta must provide until an effective prevention or a cure for SMI is discovered.

Reasons to be hopeful

Admittedly, encouraging steps are being made toward establishing a therapeutic placenta for SMI:

The RAISE Study3and Navigate Program4 demonstrate that implementing a comprehensive program of acute treatment and psychosocial interventions and rehabilitation yields better outcomes in SMI.

The Institute of Medicine released a landmark report on psychosocial interventions for mental illness and substance abuse disorders. It outlines a new model for establishing the effectiveness of intervention and the implementation of psychosocial strategies in clinical practice.5

The 21st Century Cures Act, if passed by Congress and signed by the President, will increase funding for the National Institutes of Health, which in turn will bolster the budgets of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and enhance the chances of discovering better treatments and prevention of SMI.

The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, more directly relevant to mental health and psychiatry, proposes, if passed, to:

• enhance evidence-based and scientifically validated interventions in the public sector

• raise the profile of mental health within the federal government by creating a position of Assistant Secretary for Mental Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, who will have oversight of both research and mental health care within the federal government.

Unacceptable disparity must be remedied

Planning an effective therapeutic placenta is imperative if health care for SMI patients is to approach the comprehensive spectrum of treatment, rehabilitation, and prevention available to stroke patients. Although stroke is regarded as a sensory-motor brain disorder, it is also associated with mental symptoms, just as schizophrenia is associated with sensory-motor symptoms. Both are disabling brain disorders: one, physically and cognitively; the other, mentally and socially. Both require a therapeutic placenta: Stroke is supported by one; schizophrenia is not. This is an unacceptable disparity that must be addressed—soon.

Consider stroke. Guidelines for acute treatment, access, intervention, prevention of post-hospitalization relapse, and rehabilitation are extensively spelled out and implemented.1 (The Box outlines Mayo Clinic guidelines for stroke management, as a demonstration of the comprehensiveness of the approach.)

Schizophrenia and related severe mental illnesses (SMI) need a similar all-inclusive system that seamlessly provides the myriad components of care needed for this vulnerable population. I propose the term “therapeutic placenta” to describe what people with a disabling SMI brain disorder deserve, just as stroke patients do.

Closing asylums: Psychosocial abruptio placentae

In a past Editorial,2 I described the appalling consequences of eliminating the asylum, an entity that I believe must be a key component of the SMI therapeutic placenta. The asylum is to schizophrenia as the skilled nursing home is to stroke. SMI patients suffered extensively when asylums were shut down; they lost a medical refuge with psychiatric and primary care, nursing and social work support, occupational and recreational therapies, and work therapy (farming, carpentry shop, cafeteria, laundry, etc.). For SMI, these services are the psychosocial counterpart of various physical rehabilitation therapies for stroke patients that no one would ever dare to eliminate.

Persons with schizophrenia and other SMI have suffered tragically with rupture of the main components of the therapeutic placenta that existed for decades before the advent of medications. The massive homelessness, widespread incarceration, persistent poverty, rampant access to alcohol and drugs of abuse, early death due to lack of primary care, and absence of meaningful opportunities for vocational rehabilitation are all consequences of a neglectful society that refuses to fund a therapeutic placenta for the SMI population.

The public mental health system in charge of SMI patients is broken, disconnected, and failing to provide the necessary components of a therapeutic placenta. It should not be surprising to witness the terribly stressful life and premature mortality of SMI patients, who are modern-day les misérables.

The Table lists what I consider to be the necessary spectrum of health care services through the life of an SMI patient that an optimal therapeutic placenta must provide until an effective prevention or a cure for SMI is discovered.

Reasons to be hopeful

Admittedly, encouraging steps are being made toward establishing a therapeutic placenta for SMI:

The RAISE Study3and Navigate Program4 demonstrate that implementing a comprehensive program of acute treatment and psychosocial interventions and rehabilitation yields better outcomes in SMI.

The Institute of Medicine released a landmark report on psychosocial interventions for mental illness and substance abuse disorders. It outlines a new model for establishing the effectiveness of intervention and the implementation of psychosocial strategies in clinical practice.5

The 21st Century Cures Act, if passed by Congress and signed by the President, will increase funding for the National Institutes of Health, which in turn will bolster the budgets of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and enhance the chances of discovering better treatments and prevention of SMI.

The Helping Families in Mental Health Crisis Act, more directly relevant to mental health and psychiatry, proposes, if passed, to:

• enhance evidence-based and scientifically validated interventions in the public sector

• raise the profile of mental health within the federal government by creating a position of Assistant Secretary for Mental Health in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, who will have oversight of both research and mental health care within the federal government.

Unacceptable disparity must be remedied

Planning an effective therapeutic placenta is imperative if health care for SMI patients is to approach the comprehensive spectrum of treatment, rehabilitation, and prevention available to stroke patients. Although stroke is regarded as a sensory-motor brain disorder, it is also associated with mental symptoms, just as schizophrenia is associated with sensory-motor symptoms. Both are disabling brain disorders: one, physically and cognitively; the other, mentally and socially. Both require a therapeutic placenta: Stroke is supported by one; schizophrenia is not. This is an unacceptable disparity that must be addressed—soon.

1. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bring back the asylums? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):19-20.

3. Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. The RAISE early treatment program for first-episode psychosis: background, rationale, and study design. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):240-246.

4. Mueser KT, Penn DL, Addington J, et al. The NAVIGATE program for first-episode psychosis: rationale, overview, and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):680-690.

5. The National Academy of Sciences. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, DC. http:// iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2015/ Psychosocial-Interventions-Mental-Substance- Abuse-Disorders.aspx. Published July 14, 2015. Accessed September 3, 2015.

1. Jauch EC, Saver JL, Adams HP Jr, et al; American Heart Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease; Council on Clinical Cardiology. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2013;44(3):870-947.

2. Nasrallah HA. Bring back the asylums? Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(3):19-20.

3. Kane JM, Schooler NR, Marcy P, et al. The RAISE early treatment program for first-episode psychosis: background, rationale, and study design. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(3):240-246.

4. Mueser KT, Penn DL, Addington J, et al. The NAVIGATE program for first-episode psychosis: rationale, overview, and description of psychosocial components. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(7):680-690.

5. The National Academy of Sciences. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Washington, DC. http:// iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2015/ Psychosocial-Interventions-Mental-Substance- Abuse-Disorders.aspx. Published July 14, 2015. Accessed September 3, 2015.

The value and veracity of psychiatric themes depicted in modern cinema

Perhaps more than any other medical specialty, psychiatry enjoys a longstanding and, at times, complicated relationship with cinema. Recent award-winning films, such as Still Alice, Silver Linings Playbook, and Birdman: Or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) continue traditions rooted in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Martha Marcy May Marlene, Spellbound, and dozens of other films. Through these films, psychiatry is afforded exposure unavailable to most medical specialties. This exposure has proven to be a double-edged sword, however.

Exposure vs accurate portrayal

Relative benefits and disadvantages of psychiatry’s position in film and popular media are difficult to calculate. A film such as Still Alice can provide a vivid, concrete personal narrative of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease, equipping millions of viewers with knowledge that might otherwise remain esoteric and inaccessible. Martha Marcy May Marlene offers a similar stage for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as does Spellbound for dissociative amnesia.

Such exposure comes at a cost, inevitably, because information about psychiatry is incorporated into a dramatic storyline assembled by filmmakers who are not medical professionals and who are bound by conflicting pressures. At times, those pressures outweigh the desire to accurately portray psychiatric illness.

‘Magical realism’

Two of last year’s celebrated films, Birdman and Still Alice, have continued the longstanding tradition of portraying mental illness in film. Medicine often is touted as art and science; film likewise sits at this intersection. However, filmmakers are artists, primarily, and the nature of storytelling is to emphasize art over scientific accuracy.

The main character in Birdman, for example, manifests psychosis, but many of his presenting signs and symptoms are incongruent with any diagnosable form of psychosis. To tell its story, the film employs magical realism, a celebrated literary and film technique. Although magical realism might detract from the accuracy of the condition portrayed, it adds cinematic appeal to the film, likely creates more entertainment value, and, in turn, garners appreciation from a broader audience.

Expansion of medical information, accurate and otherwise

As in the 1970’s, we are, today, in the midst of rapidly evolving societal norms. One of the most rapid changes is in how the public acquires information. We are in the midst of the “Googlification” of medical knowledge and the expansion of online medical resources. These resources can, simultaneously, inform and mislead the public.

Popular films behave in much the same way. There is no motion picture-guild requirement that mentally ill characters in films such as Birdman meet any set of psychiatric criteria, from DSM-5 or elsewhere. Similarly, the fact that psychiatrists do not control the information in films that portray mental illness comes as no surprise.

‘One flew East, one flew West…’

The tension between engaging storytelling and medical accuracy certainly is not a new phenomenon, extending not only to representations of disease but to representations of treatment. Consider director Miloš Forman’s seminal 1975 film, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, whose chief importance for psychiatry rests not in its individualized representations of patients but in a portrayal of the environment in which they are treated. Louise Fletcher’s Academy Award-winning portrayal of cruel Nurse Ratched has lingered in the public consciousness, remaining a prominent image for many Americans when they think of a psychiatric institution.

When Cuckoo’s Nest was released, it was considered by critics to be an “exploration of society’s enforcement of conformism” that “almost willfully overlooked the realities of mental illness”1 so that it could vivify its protagonist’s struggle against tyrannical Nurse Ratched. The film’s primary intent might not have been to make a statement about the injustices of the time, but it has certainly had a lasting effect on the public’s perception of psychiatric illness and treatment.

Films offer an opportunity for discussion

Films on the theme of psychiatry and mental illness have long held a distinctive position in the canon of Western cinema. In this vein, films from the past year have made timely contributions to the genre. Although Still Alice and Birdman might prove to be ground-breaking in changing societal views over time, we must not expect them to do so.

Nevertheless, psychiatry ought to take advantage of popular films’ wide exposure and ability to destigmatize mental illness—rather than lament medical inaccuracies in these films.

Cinema is, first and foremost, an art. Although patients and the public might pick up misconceptions about psychosis, Alzheimer’s disease, or PTSD because popular films take artistic liberty about mental illness, psychiatrists are available to set the record straight. After all, psychiatry has long been about managing perceptions, and patient education is at the core of our specialty.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Ebert R. “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (review). http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-one-flew-overthe-cuckoos-nest-1975. February 2, 2003. Accessed September 9, 2015.

Perhaps more than any other medical specialty, psychiatry enjoys a longstanding and, at times, complicated relationship with cinema. Recent award-winning films, such as Still Alice, Silver Linings Playbook, and Birdman: Or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) continue traditions rooted in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Martha Marcy May Marlene, Spellbound, and dozens of other films. Through these films, psychiatry is afforded exposure unavailable to most medical specialties. This exposure has proven to be a double-edged sword, however.

Exposure vs accurate portrayal

Relative benefits and disadvantages of psychiatry’s position in film and popular media are difficult to calculate. A film such as Still Alice can provide a vivid, concrete personal narrative of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease, equipping millions of viewers with knowledge that might otherwise remain esoteric and inaccessible. Martha Marcy May Marlene offers a similar stage for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as does Spellbound for dissociative amnesia.

Such exposure comes at a cost, inevitably, because information about psychiatry is incorporated into a dramatic storyline assembled by filmmakers who are not medical professionals and who are bound by conflicting pressures. At times, those pressures outweigh the desire to accurately portray psychiatric illness.

‘Magical realism’

Two of last year’s celebrated films, Birdman and Still Alice, have continued the longstanding tradition of portraying mental illness in film. Medicine often is touted as art and science; film likewise sits at this intersection. However, filmmakers are artists, primarily, and the nature of storytelling is to emphasize art over scientific accuracy.

The main character in Birdman, for example, manifests psychosis, but many of his presenting signs and symptoms are incongruent with any diagnosable form of psychosis. To tell its story, the film employs magical realism, a celebrated literary and film technique. Although magical realism might detract from the accuracy of the condition portrayed, it adds cinematic appeal to the film, likely creates more entertainment value, and, in turn, garners appreciation from a broader audience.

Expansion of medical information, accurate and otherwise

As in the 1970’s, we are, today, in the midst of rapidly evolving societal norms. One of the most rapid changes is in how the public acquires information. We are in the midst of the “Googlification” of medical knowledge and the expansion of online medical resources. These resources can, simultaneously, inform and mislead the public.

Popular films behave in much the same way. There is no motion picture-guild requirement that mentally ill characters in films such as Birdman meet any set of psychiatric criteria, from DSM-5 or elsewhere. Similarly, the fact that psychiatrists do not control the information in films that portray mental illness comes as no surprise.

‘One flew East, one flew West…’

The tension between engaging storytelling and medical accuracy certainly is not a new phenomenon, extending not only to representations of disease but to representations of treatment. Consider director Miloš Forman’s seminal 1975 film, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, whose chief importance for psychiatry rests not in its individualized representations of patients but in a portrayal of the environment in which they are treated. Louise Fletcher’s Academy Award-winning portrayal of cruel Nurse Ratched has lingered in the public consciousness, remaining a prominent image for many Americans when they think of a psychiatric institution.

When Cuckoo’s Nest was released, it was considered by critics to be an “exploration of society’s enforcement of conformism” that “almost willfully overlooked the realities of mental illness”1 so that it could vivify its protagonist’s struggle against tyrannical Nurse Ratched. The film’s primary intent might not have been to make a statement about the injustices of the time, but it has certainly had a lasting effect on the public’s perception of psychiatric illness and treatment.

Films offer an opportunity for discussion

Films on the theme of psychiatry and mental illness have long held a distinctive position in the canon of Western cinema. In this vein, films from the past year have made timely contributions to the genre. Although Still Alice and Birdman might prove to be ground-breaking in changing societal views over time, we must not expect them to do so.

Nevertheless, psychiatry ought to take advantage of popular films’ wide exposure and ability to destigmatize mental illness—rather than lament medical inaccuracies in these films.

Cinema is, first and foremost, an art. Although patients and the public might pick up misconceptions about psychosis, Alzheimer’s disease, or PTSD because popular films take artistic liberty about mental illness, psychiatrists are available to set the record straight. After all, psychiatry has long been about managing perceptions, and patient education is at the core of our specialty.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Perhaps more than any other medical specialty, psychiatry enjoys a longstanding and, at times, complicated relationship with cinema. Recent award-winning films, such as Still Alice, Silver Linings Playbook, and Birdman: Or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance) continue traditions rooted in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Martha Marcy May Marlene, Spellbound, and dozens of other films. Through these films, psychiatry is afforded exposure unavailable to most medical specialties. This exposure has proven to be a double-edged sword, however.

Exposure vs accurate portrayal

Relative benefits and disadvantages of psychiatry’s position in film and popular media are difficult to calculate. A film such as Still Alice can provide a vivid, concrete personal narrative of a patient with Alzheimer’s disease, equipping millions of viewers with knowledge that might otherwise remain esoteric and inaccessible. Martha Marcy May Marlene offers a similar stage for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as does Spellbound for dissociative amnesia.

Such exposure comes at a cost, inevitably, because information about psychiatry is incorporated into a dramatic storyline assembled by filmmakers who are not medical professionals and who are bound by conflicting pressures. At times, those pressures outweigh the desire to accurately portray psychiatric illness.

‘Magical realism’

Two of last year’s celebrated films, Birdman and Still Alice, have continued the longstanding tradition of portraying mental illness in film. Medicine often is touted as art and science; film likewise sits at this intersection. However, filmmakers are artists, primarily, and the nature of storytelling is to emphasize art over scientific accuracy.

The main character in Birdman, for example, manifests psychosis, but many of his presenting signs and symptoms are incongruent with any diagnosable form of psychosis. To tell its story, the film employs magical realism, a celebrated literary and film technique. Although magical realism might detract from the accuracy of the condition portrayed, it adds cinematic appeal to the film, likely creates more entertainment value, and, in turn, garners appreciation from a broader audience.

Expansion of medical information, accurate and otherwise

As in the 1970’s, we are, today, in the midst of rapidly evolving societal norms. One of the most rapid changes is in how the public acquires information. We are in the midst of the “Googlification” of medical knowledge and the expansion of online medical resources. These resources can, simultaneously, inform and mislead the public.

Popular films behave in much the same way. There is no motion picture-guild requirement that mentally ill characters in films such as Birdman meet any set of psychiatric criteria, from DSM-5 or elsewhere. Similarly, the fact that psychiatrists do not control the information in films that portray mental illness comes as no surprise.

‘One flew East, one flew West…’

The tension between engaging storytelling and medical accuracy certainly is not a new phenomenon, extending not only to representations of disease but to representations of treatment. Consider director Miloš Forman’s seminal 1975 film, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, whose chief importance for psychiatry rests not in its individualized representations of patients but in a portrayal of the environment in which they are treated. Louise Fletcher’s Academy Award-winning portrayal of cruel Nurse Ratched has lingered in the public consciousness, remaining a prominent image for many Americans when they think of a psychiatric institution.

When Cuckoo’s Nest was released, it was considered by critics to be an “exploration of society’s enforcement of conformism” that “almost willfully overlooked the realities of mental illness”1 so that it could vivify its protagonist’s struggle against tyrannical Nurse Ratched. The film’s primary intent might not have been to make a statement about the injustices of the time, but it has certainly had a lasting effect on the public’s perception of psychiatric illness and treatment.

Films offer an opportunity for discussion

Films on the theme of psychiatry and mental illness have long held a distinctive position in the canon of Western cinema. In this vein, films from the past year have made timely contributions to the genre. Although Still Alice and Birdman might prove to be ground-breaking in changing societal views over time, we must not expect them to do so.

Nevertheless, psychiatry ought to take advantage of popular films’ wide exposure and ability to destigmatize mental illness—rather than lament medical inaccuracies in these films.

Cinema is, first and foremost, an art. Although patients and the public might pick up misconceptions about psychosis, Alzheimer’s disease, or PTSD because popular films take artistic liberty about mental illness, psychiatrists are available to set the record straight. After all, psychiatry has long been about managing perceptions, and patient education is at the core of our specialty.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Ebert R. “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (review). http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-one-flew-overthe-cuckoos-nest-1975. February 2, 2003. Accessed September 9, 2015.

Reference

1. Ebert R. “One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest (review). http://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-one-flew-overthe-cuckoos-nest-1975. February 2, 2003. Accessed September 9, 2015.

Managing borderline personality disorder

Assessing head pain

CUT DOWNTIME: The Lean way for a busy practitioner to improve efficiency

The mnemonic CUT DOWNTIME, which I have adapted and modified from the book Lean Healthcare Deployment and Sustainability,1 breaks down waste in health care—an activity that adds no value to a service—into 11 major categories (Table). This mnemonic provides the busy practitioner a simple framework for improving quality and efficiency of services by identifying and eliminating wastes the Lean way.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Dean ML. Lean healthcare deployment and sustainability. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

The mnemonic CUT DOWNTIME, which I have adapted and modified from the book Lean Healthcare Deployment and Sustainability,1 breaks down waste in health care—an activity that adds no value to a service—into 11 major categories (Table). This mnemonic provides the busy practitioner a simple framework for improving quality and efficiency of services by identifying and eliminating wastes the Lean way.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The mnemonic CUT DOWNTIME, which I have adapted and modified from the book Lean Healthcare Deployment and Sustainability,1 breaks down waste in health care—an activity that adds no value to a service—into 11 major categories (Table). This mnemonic provides the busy practitioner a simple framework for improving quality and efficiency of services by identifying and eliminating wastes the Lean way.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Reference

1. Dean ML. Lean healthcare deployment and sustainability. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

Reference

1. Dean ML. Lean healthcare deployment and sustainability. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2013.

‘It’s my money, and I want it now!’ Clinical variables related to payeeship under Social Security

The Social Security Administration (SSA) does not provide much guidance on the contentious issue of determining payeeship for disability beneficiaries. The only description available is stated on the “Physician/medical officer’s statement of patient’s capability to manage benefits” (form SSA-787): “By capable we mean that the patient: Is able to understand and act on the ordinary affairs of life, such as providing for own adequate food, housing, etc., and is able, in spite of physical impairments, to manage funds or direct others how to manage them.”

Physicians will be asked to make a capability statement if they are performing a consultative examination for SSA or if their patient:

• is applying for benefits

• needs to have a payee.

Regrettably, the published literature on capability is scant.1,2 Based on decades of personal experience, here is the approach I have adopted to determine capability.

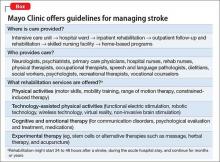

Diagnoses, circumstances, and clinical syndromes that strongly suggest the need for a payee include those listed in the Table.

The psychiatric rehabilitation agency I work at adheres to a recovery model. I consult with caseworkers on the issue of capability, but generally endorse a “team” recommendation for initiating or terminating payeeship. A number of factors are involved:

Adherence to recovery means that we encourage autonomy; we do not attempt to prevent every bad decision.

Demands for money from the patient and demands to terminate payeeship can be strident and potentially violent.

Confrontations over payeeship can be a safety risk for family or staff who have been acting as the payee.

Guardianship (or conservatorship) is a judicially determined restriction of financial decision-making.

Payeeship is an extrajudicial restriction of financial decision-making. Treating physicians, understandably, may feel uneasy restricting the rights of a patient. Additionally, there is ethical stress when a physician does anything that might compromise the primacy of the treatment relationship.

If all parties agree that payeeship should be terminated, I recommend the payee (whether the family or an institutional payee) begin a 3-month trial, during which the payee does not pay bills or keep a budget. The patient receives his (her) money in a lump sum at the beginning of the month, which begins a naturalistic trial of the patient’s capability to pay rent and budget adequately for all other necessities. If the patient demonstrates capability, I sign the SSA-787 form.

Offering a structured plan for restoring a patient’s benefits could defuse hostile demands.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Marson DC, Savage R, Phillips J. Financial capacity in persons with schizophrenia and serious mental illness: clinical and research ethics aspects. Schizophr Bull. 2006; 32(1):81-91.

2. Rosen MI. The ‘check effect’ reconsidered. Addiction. 2011;106(6):1071-1077.

The Social Security Administration (SSA) does not provide much guidance on the contentious issue of determining payeeship for disability beneficiaries. The only description available is stated on the “Physician/medical officer’s statement of patient’s capability to manage benefits” (form SSA-787): “By capable we mean that the patient: Is able to understand and act on the ordinary affairs of life, such as providing for own adequate food, housing, etc., and is able, in spite of physical impairments, to manage funds or direct others how to manage them.”

Physicians will be asked to make a capability statement if they are performing a consultative examination for SSA or if their patient:

• is applying for benefits

• needs to have a payee.

Regrettably, the published literature on capability is scant.1,2 Based on decades of personal experience, here is the approach I have adopted to determine capability.

Diagnoses, circumstances, and clinical syndromes that strongly suggest the need for a payee include those listed in the Table.

The psychiatric rehabilitation agency I work at adheres to a recovery model. I consult with caseworkers on the issue of capability, but generally endorse a “team” recommendation for initiating or terminating payeeship. A number of factors are involved:

Adherence to recovery means that we encourage autonomy; we do not attempt to prevent every bad decision.

Demands for money from the patient and demands to terminate payeeship can be strident and potentially violent.

Confrontations over payeeship can be a safety risk for family or staff who have been acting as the payee.

Guardianship (or conservatorship) is a judicially determined restriction of financial decision-making.

Payeeship is an extrajudicial restriction of financial decision-making. Treating physicians, understandably, may feel uneasy restricting the rights of a patient. Additionally, there is ethical stress when a physician does anything that might compromise the primacy of the treatment relationship.

If all parties agree that payeeship should be terminated, I recommend the payee (whether the family or an institutional payee) begin a 3-month trial, during which the payee does not pay bills or keep a budget. The patient receives his (her) money in a lump sum at the beginning of the month, which begins a naturalistic trial of the patient’s capability to pay rent and budget adequately for all other necessities. If the patient demonstrates capability, I sign the SSA-787 form.

Offering a structured plan for restoring a patient’s benefits could defuse hostile demands.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.