User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

A medication change, then involuntary lip smacking and tongue rolling

CASE Insurer denies drug coverage

Ms. X, age 65, has a 35-year history of bipolar I disorder (BD I) characterized by psychotic mania and severe suicidal depression. For the past year, her symptoms have been well controlled with aripiprazole, 5 mg/d; trazodone, 50 mg at bedtime; and citalopram, 20 mg/d. Because her health insurance has changed, Ms. X asks to be switched to an alternative antipsychotic because the new provider denied coverage of aripiprazole.

While taking aripiprazole, Ms. X did not report any extrapyramidal side effects, including tardive dyskinesia. Her Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) score is 4. No significant abnormal movements were noted on examination during previous medication management sessions.

We decide to replace aripiprazole with quetiapine, 50 mg/d. At a 2-week follow-up visit, Ms. X is noted to have euphoric mood and reduced need to sleep, flight of ideas, increased talkativeness, and paranoia. We also notice that she has significant tongue rolling and lip smacking, which she says started 10 days after changing from aripiprazole to quetiapine. Her AIMS score is 17.

What could be causing Ms. X’s tongue rolling and lip smacking?

a) an irreversible syndrome usually starting after 1 or 2 years of continuous exposure to antipsychotics

b) a self-limited condition expected to resolve completely within 12 weeks

c) an acute manifestation of an antipsychotic that can respond to an anticholinergic agent

d) none of the above

The authors’ observations

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) refers to at least moderate abnormal involuntary movements in ≥1 areas of the body or at least mild movements in ≥2 areas of the body, developing after ≥3 months of cumulative exposure (continuous or discontinuous) to dopamine D2 receptor-blocking agents.1 AIMS is a 14-item, clinician-administered questionnaire designed to evaluate such movements and track their severity over time. The first 10 items are rated on 5-point scale (0 = none; 1 = minimal; 2 = mild; 3 = moderate; 4 = severe), with items 1 to 4 assessing orofacial movements, 5 to 7 assessing extremity and truncal movements, and 8 to 10 assessing overall severity, impairment, and subjective distress. Items 11 to 13 assess dental status because lack of teeth can result in oral movements mimicking TDs. The last item assesses whether these movements disappear during sleep.

HISTORY Poor response

Ms. X was given a diagnosis of BD I at age 30; she first started taking antipsychotics 10 years later. Previous psychotropic trials included lamotrigine, divalproex sodium, risperidone, and ziprasidone, which were ineffective or poorly tolerated. Her medical history includes obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, fibromyalgia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and hypothyroidism. She takes metformin, omeprazole, pravastatin, carvedilol, insulin, levothyroxine, methylphenidate (for hypersomnia), and enalapril.

What is the next best step in management?

a) discontinue quetiapine

b) replace quetiapine with clozapine

c) increase quetiapine to target manic symptoms and reassess in a few weeks

d) continue quetiapine and treat abnormal movements with benztropine

TREATMENT Increase dosage

We increase quetiapine to 150 mg/d to target Ms. X’s manic symptoms. She is scheduled for a follow-up visit in 4 weeks but is instructed to return to the clinic earlier if her manic symptoms do not improve. At the 4-week follow-up visit, Ms. X does not have any abnormal movements and her manic symptoms have resolved. Her AIMS score is 4. Her husband reports that her abnormal movements resolved 4 days after increasing quetiapine to 150 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

Second-generation antipsychotics are known to have a lower risk of extrapyramidal adverse reactions compared with older first-generation antipsychotics.2,3 TD differs from other extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) because of its delayed onset. Risk factors for TD include:

• female sex

• age >50

• history of brain damage

• long-term antipsychotic use

• diagnosis of a mood disorder.

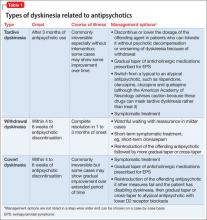

Gardos et al4 described 2 other forms of delayed dyskinesias related to antipsychotic use but resulting from antipsychotic discontinuation: withdrawal dyskinesia and covert dyskinesia. Evidence for these types of antipsychotic discontinuation syndromes mostly is anecdotal.5,6Table 1 highlights 3 different types of dyskinesias and their management.

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been described as a syndrome resembling TD that appears after discontinuation or dosage reduction of an antipsychotic in a patient who does not have an earlier TD diagnosis.7 The prevalence of withdrawal dyskinesia among patients undergoing antipsychotic discontinuation is approximately 30%.8 Cases of withdrawal dyskinesia are self-limited and resolve in 1 to 3 months.9,10 We believe that Ms. X’s movement disorder was withdrawal dyskinesia from aripiprazole because her symptoms started 10 days after the drug was discontinued, and was self-limited and reversible.

Similar to TD, withdrawal dyskinesia can present in different forms:

• tongue protrusion movements

• facial grimacing

• ticks

• chorea

• tremors

• athetosis

• involuntary vocalizations

• abnormal movements of hands and legs

• “dyspnea” due to involvement of respiratory musculature.5,11

There may be a sex difference in duration of withdrawal dyskinesias, because symptoms persist longer in females.9

Although covert dyskinesia also develops after discontinuation or dosage reduction of a dopamine-blocking agent, the symptoms usually are permanent, and could require reintroducing the antipsychotic or management with evidence-based treatments for TD, such as tetrabenazine or amantadine.6,12

What is the cause of Ms. X’s abnormal involuntary movements?

a) quetiapine-induced D2 receptor hypersensitivity

b) aripiprazole-induced cholinergic overactivity

c) quetiapine-induced cholinergic overactivity

d) aripiprazole-induced D2 receptor hypersensitivity

The authors’ observations

Pathophysiology of this condition is unknown but different theories have been proposed. D2 receptor up-regulation and hypersensitivity to compensate for chronic D2 receptor blockade by antipsychotics is a commonly cited theory.7,13 Discontinuation of an antipsychotic can make this D2 receptor up-regulation and hypersensitivity manifest as withdrawal dyskinesia by creating a temporary hyperdopaminergic state in basal ganglia. Other theories implicate decrease of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the globus pallidus (GP) and substantia nigra (SN) regions of the brain, and oxidative damage to GABAergic interneurons in GP and SN from excess production of catecholamines in response to chronic dopamine blockade.14

It has been proposed that patients with withdrawal dyskinesia might be in an early phase of D2 receptor modulation that, if continued because of use of the antipsychotic implicated in withdrawal dyskinesia, can lead to development of TD.4,7,8 A feature of withdrawal dyskinesia that differentiates it from TD is that it usually remits spontaneously within several weeks to a few months.4,7 Because of this characteristic, Schultz et al8 propose that, if withdrawal dyskinesia is identified early in treatment, it may be possible to prevent development of persistent TD.

Look carefully for dyskinetic movements in patients who have recently discontinued or decreased the dosage of their antipsychotic. Non-compliance and partial compliance are common problems among patients taking an antipsychotic.15 Therefore, careful watchfulness for withdrawal dyskinesias at all times can be beneficial. Inquiring about recent history of these dyskinesias in such patients is probably more useful than an exam because the dyskinesias may not be evident on exam when these patients show up for their follow-up visit, because of their self-limited nature.8

Treatment options

If a patient is noted to have a withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia, a clinician has options to prevent TD, including:

• decreasing the dosage of the antipsychotic

• switching from a typical antipsychotic to an atypical antipsychotic

• switching from one atypical to another with lesser affinity for striatal D2 receptor, such as clozapine or quetiapine.16,17

In addition, researchers are investigating the use of vitamin B6, Ginkgo biloba, amantadine, levetiracetam, melatonin, tetrabenazine, zonisamide, branched chain amino acids, clonazepam, and vitamin E as treatment alternatives for TD.

Tetrabenazine acts by blocking vesicular monoamine transporter type 2, thereby inhibiting release of monoamines, including dopamine into synaptic cleft area in basal ganglia.18 Clonazepam’s benefit for TD relates to its facilitation of GABAergic neurotransmission, because reduced GABAergic transmission in GP and SN has been associ ated with hyperkinetic movements, including TD.14Ginkgo biloba and melatonin exert their beneficial effects in TD through their antioxidant function.14

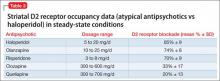

The agents listed in Table 219 could be used on a short-term basis for symptomatic treatment of withdrawal dyskinesias.1,18,20

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been reported with aripiprazole discontinuation and is thought to be related to aripiprazole’s strong affinity for D2 receptors.21 Aripiprazole at dosages of 15 to 30 mg/d can occupy more than 80% of the striatal D2 dopamine receptors. The dosage of ≥30 mg/d can lead to receptor occupancy of >90%.22 Studies have shown that EPS correlate with D2 receptor occupancy in steady-state conditions, and occupancy exceeding 80% results in these symptoms.22

Compared with aripiprazole, quetiapine has weak affinity for D2 receptors (Table 3), making it an unlikely culprit if dyskinesia emerges within 2 weeks of initation.22 We believe that, in Ms. X’s case, quetiapine might have masked the severity of aripiprazole withdrawal dyskinesia by causing some degree of D2 receptor blockade. It may have decreased the duration of withdrawal dyskinesia by the same effect on D2 receptors. It may have lasted longer if aripiprazole was not replaced by another antipsychotic. This is particularly evident because dyskinesia improved quickly when quetiapine was titrated to 150 mg/d. The higher quetiapine dosage of 150 mg/d is closer to 5 mg/d of aripiprazole in terms of D2 receptor occupancy and affinity. However, quetiapine is weaker than aripiprazole in terms of D2 receptor occupancy at all dosages, and therefore less likely to cause EPS.16

Summing up

Withdrawal dyskinesia in the absence of a history of TD is a common symptom of antipsychotic discontinuation or dosage reduction after long-term use of an antipsychotic. It is more commonly seen with antipsychotics with high D2 receptor occupancy, and has been hypothesized to be related to D2 receptor supersensitivity to ambient dopamine, resulting as a compensatory response to chronic D2 blockade by this class of medication.

Evidence suggests that reversible withdrawal dyskinesia could represent a prodrome to irreversible TD. Therefore, keeping a watchful eye for these movements during the exam, along with specific inquiry about withdrawal dyskinesias while taking a history at every follow-up visit, is important because doing so can:

• inform the clinician about partial compliance or noncompliance to these medications, which could lead to treatment failure

• help prevent development of irreversible TD syndrome.

Ms. X’s case reminds clinicians (1) to be aware of this unexpected side effect occurring even with second-generation antipsychotics and (2) that they should consider EPS in patients while they are discontinuing their drugs. Furthermore, it is important for clinical and medicolegal reasons to inform our patients that different forms of dyskinesias can be potential side effects of antipsychotics.

Bottom Line

Dyskinesias can result from withdrawal of both typical and atypical antipsychotics, and usually are self-limited. Withdrawal dyskinesia may represent a prodrome to tardive dyskinesia; early recognition may aid in preventing development of persistent tardive dyskinesia.

Related Resources

• Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. http://www.cqaimh.org/pdf/toolaims.pdf.

• Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2012.

• Tarsay D. Tardive dyskinesia: prevention and treatment. http:// www.uptodate.com/contents/tardive-dyskinesia-prevention-and-treatment?topicKey=NEURO%2F4908&elapsedTimeMs=3 &view=print&displayedView=full#.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Benztropine • Cogentin

Carvedilol • Coreg

Citalopram • Celexa

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Donepezil • Aricept

Enalapril • Vasotec

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthroid

Metformin • Glucophage

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Omeprazole • Prilosec

Pravastatin • Pravachol

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tetrabenazine • Xenazine

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zonisamide • Zonegran

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bhidayasiri R1, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

2. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

3. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):414-425.

4. Gardos G, Cole JO, Tarsy D. Withdrawal syndromes associated with antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135(11):1321-1324.

5. Salomon C, Hamilton B. Antipsychotic discontinuation syndromes: a narrative review of the evidence and its integration into Australian mental health nursing textbooks. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2014;23(1):69-78.

6. Moseley CN, Simpson-Khanna HA, Catalano G, et al. Covert dyskinesia associated with aripiprazole: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36(4):128-130.

7. Anand VS, Dewan MJ. Withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia in a patient on risperidone undergoing dosage reduction. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1996;8(3):179-182.

8. Schultz SK, Miller DD, Arndt S, et al. Withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia during antipsychotic discontinuation. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38(11):713-719.

9. Degkwitz R, Bauer MP, Gruber M, et al. Time relationship between the appearance of persisting extrapyramidal hyperkineses and psychotic recurrences following sudden interruption of prolonged neuroleptic therapy of chronic schizophrenic patients [in German]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1970;20(7):890-893.

10. Sethi KD. Tardive dyskinesias. In: Adler CH, Ahlskog JE, eds. Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders: diagnosis and treatment guidelines for the practicing physician. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2000:331-338.

11. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

12. Horváth K, Aschermann Z, Komoly S, et al. Treatment of tardive syndromes [in Hungarian]. Psychiatr Hung. 2014;29(2):214-224.

13. Samaha AN, Seeman P, Stewart J, et al. “Breakthrough” dopamine supersensitivity during ongoing antipsychotic treatment leads to treatment failure over time. J Neurosci. 2007;27(11):2979-2986.

14. Thelma B, Srivastava V, Tiwari AK. Genetic underpinnings of tardive dyskinesia: passing the baton to pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9(9):1285-1306.

15. Keith SJ, Kane JM. Partial compliance and patient consequences in schizophrenia: our patients can do better. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1308-1315.

16. Lieberman JA, Saltz BL, Johns CA, et al. The effects of clozapine on tardive dyskinesia. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:503-510.

17. Farah A. Atypicality of atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(6):268-274.

18. Rana AQ, Chaudry ZM, Blanchet PJ. New and emerging treatments for symptomatic tardive dyskinesia. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:1329-1340.

19. Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, et al. Developing clinical guidelines. West J Med. 1999;170(6):348-351.

20. Cloud LJ, Zutshi D, Factor SA. Tardive dyskinesia: therapeutic options for an increasingly common disorder. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(1):166-176.

21. Urbano M, Spiegel D, Rai A. Atypical antipsychotic withdrawal dyskinesia in 4 patients with mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):705-707.

22. Pani L, Pira L, Marchese G. Antipsychotic efficacy: relationship to optimal D2-receptor occupancy. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(5):267-275.

CASE Insurer denies drug coverage

Ms. X, age 65, has a 35-year history of bipolar I disorder (BD I) characterized by psychotic mania and severe suicidal depression. For the past year, her symptoms have been well controlled with aripiprazole, 5 mg/d; trazodone, 50 mg at bedtime; and citalopram, 20 mg/d. Because her health insurance has changed, Ms. X asks to be switched to an alternative antipsychotic because the new provider denied coverage of aripiprazole.

While taking aripiprazole, Ms. X did not report any extrapyramidal side effects, including tardive dyskinesia. Her Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) score is 4. No significant abnormal movements were noted on examination during previous medication management sessions.

We decide to replace aripiprazole with quetiapine, 50 mg/d. At a 2-week follow-up visit, Ms. X is noted to have euphoric mood and reduced need to sleep, flight of ideas, increased talkativeness, and paranoia. We also notice that she has significant tongue rolling and lip smacking, which she says started 10 days after changing from aripiprazole to quetiapine. Her AIMS score is 17.

What could be causing Ms. X’s tongue rolling and lip smacking?

a) an irreversible syndrome usually starting after 1 or 2 years of continuous exposure to antipsychotics

b) a self-limited condition expected to resolve completely within 12 weeks

c) an acute manifestation of an antipsychotic that can respond to an anticholinergic agent

d) none of the above

The authors’ observations

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) refers to at least moderate abnormal involuntary movements in ≥1 areas of the body or at least mild movements in ≥2 areas of the body, developing after ≥3 months of cumulative exposure (continuous or discontinuous) to dopamine D2 receptor-blocking agents.1 AIMS is a 14-item, clinician-administered questionnaire designed to evaluate such movements and track their severity over time. The first 10 items are rated on 5-point scale (0 = none; 1 = minimal; 2 = mild; 3 = moderate; 4 = severe), with items 1 to 4 assessing orofacial movements, 5 to 7 assessing extremity and truncal movements, and 8 to 10 assessing overall severity, impairment, and subjective distress. Items 11 to 13 assess dental status because lack of teeth can result in oral movements mimicking TDs. The last item assesses whether these movements disappear during sleep.

HISTORY Poor response

Ms. X was given a diagnosis of BD I at age 30; she first started taking antipsychotics 10 years later. Previous psychotropic trials included lamotrigine, divalproex sodium, risperidone, and ziprasidone, which were ineffective or poorly tolerated. Her medical history includes obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, fibromyalgia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and hypothyroidism. She takes metformin, omeprazole, pravastatin, carvedilol, insulin, levothyroxine, methylphenidate (for hypersomnia), and enalapril.

What is the next best step in management?

a) discontinue quetiapine

b) replace quetiapine with clozapine

c) increase quetiapine to target manic symptoms and reassess in a few weeks

d) continue quetiapine and treat abnormal movements with benztropine

TREATMENT Increase dosage

We increase quetiapine to 150 mg/d to target Ms. X’s manic symptoms. She is scheduled for a follow-up visit in 4 weeks but is instructed to return to the clinic earlier if her manic symptoms do not improve. At the 4-week follow-up visit, Ms. X does not have any abnormal movements and her manic symptoms have resolved. Her AIMS score is 4. Her husband reports that her abnormal movements resolved 4 days after increasing quetiapine to 150 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

Second-generation antipsychotics are known to have a lower risk of extrapyramidal adverse reactions compared with older first-generation antipsychotics.2,3 TD differs from other extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) because of its delayed onset. Risk factors for TD include:

• female sex

• age >50

• history of brain damage

• long-term antipsychotic use

• diagnosis of a mood disorder.

Gardos et al4 described 2 other forms of delayed dyskinesias related to antipsychotic use but resulting from antipsychotic discontinuation: withdrawal dyskinesia and covert dyskinesia. Evidence for these types of antipsychotic discontinuation syndromes mostly is anecdotal.5,6Table 1 highlights 3 different types of dyskinesias and their management.

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been described as a syndrome resembling TD that appears after discontinuation or dosage reduction of an antipsychotic in a patient who does not have an earlier TD diagnosis.7 The prevalence of withdrawal dyskinesia among patients undergoing antipsychotic discontinuation is approximately 30%.8 Cases of withdrawal dyskinesia are self-limited and resolve in 1 to 3 months.9,10 We believe that Ms. X’s movement disorder was withdrawal dyskinesia from aripiprazole because her symptoms started 10 days after the drug was discontinued, and was self-limited and reversible.

Similar to TD, withdrawal dyskinesia can present in different forms:

• tongue protrusion movements

• facial grimacing

• ticks

• chorea

• tremors

• athetosis

• involuntary vocalizations

• abnormal movements of hands and legs

• “dyspnea” due to involvement of respiratory musculature.5,11

There may be a sex difference in duration of withdrawal dyskinesias, because symptoms persist longer in females.9

Although covert dyskinesia also develops after discontinuation or dosage reduction of a dopamine-blocking agent, the symptoms usually are permanent, and could require reintroducing the antipsychotic or management with evidence-based treatments for TD, such as tetrabenazine or amantadine.6,12

What is the cause of Ms. X’s abnormal involuntary movements?

a) quetiapine-induced D2 receptor hypersensitivity

b) aripiprazole-induced cholinergic overactivity

c) quetiapine-induced cholinergic overactivity

d) aripiprazole-induced D2 receptor hypersensitivity

The authors’ observations

Pathophysiology of this condition is unknown but different theories have been proposed. D2 receptor up-regulation and hypersensitivity to compensate for chronic D2 receptor blockade by antipsychotics is a commonly cited theory.7,13 Discontinuation of an antipsychotic can make this D2 receptor up-regulation and hypersensitivity manifest as withdrawal dyskinesia by creating a temporary hyperdopaminergic state in basal ganglia. Other theories implicate decrease of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the globus pallidus (GP) and substantia nigra (SN) regions of the brain, and oxidative damage to GABAergic interneurons in GP and SN from excess production of catecholamines in response to chronic dopamine blockade.14

It has been proposed that patients with withdrawal dyskinesia might be in an early phase of D2 receptor modulation that, if continued because of use of the antipsychotic implicated in withdrawal dyskinesia, can lead to development of TD.4,7,8 A feature of withdrawal dyskinesia that differentiates it from TD is that it usually remits spontaneously within several weeks to a few months.4,7 Because of this characteristic, Schultz et al8 propose that, if withdrawal dyskinesia is identified early in treatment, it may be possible to prevent development of persistent TD.

Look carefully for dyskinetic movements in patients who have recently discontinued or decreased the dosage of their antipsychotic. Non-compliance and partial compliance are common problems among patients taking an antipsychotic.15 Therefore, careful watchfulness for withdrawal dyskinesias at all times can be beneficial. Inquiring about recent history of these dyskinesias in such patients is probably more useful than an exam because the dyskinesias may not be evident on exam when these patients show up for their follow-up visit, because of their self-limited nature.8

Treatment options

If a patient is noted to have a withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia, a clinician has options to prevent TD, including:

• decreasing the dosage of the antipsychotic

• switching from a typical antipsychotic to an atypical antipsychotic

• switching from one atypical to another with lesser affinity for striatal D2 receptor, such as clozapine or quetiapine.16,17

In addition, researchers are investigating the use of vitamin B6, Ginkgo biloba, amantadine, levetiracetam, melatonin, tetrabenazine, zonisamide, branched chain amino acids, clonazepam, and vitamin E as treatment alternatives for TD.

Tetrabenazine acts by blocking vesicular monoamine transporter type 2, thereby inhibiting release of monoamines, including dopamine into synaptic cleft area in basal ganglia.18 Clonazepam’s benefit for TD relates to its facilitation of GABAergic neurotransmission, because reduced GABAergic transmission in GP and SN has been associ ated with hyperkinetic movements, including TD.14Ginkgo biloba and melatonin exert their beneficial effects in TD through their antioxidant function.14

The agents listed in Table 219 could be used on a short-term basis for symptomatic treatment of withdrawal dyskinesias.1,18,20

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been reported with aripiprazole discontinuation and is thought to be related to aripiprazole’s strong affinity for D2 receptors.21 Aripiprazole at dosages of 15 to 30 mg/d can occupy more than 80% of the striatal D2 dopamine receptors. The dosage of ≥30 mg/d can lead to receptor occupancy of >90%.22 Studies have shown that EPS correlate with D2 receptor occupancy in steady-state conditions, and occupancy exceeding 80% results in these symptoms.22

Compared with aripiprazole, quetiapine has weak affinity for D2 receptors (Table 3), making it an unlikely culprit if dyskinesia emerges within 2 weeks of initation.22 We believe that, in Ms. X’s case, quetiapine might have masked the severity of aripiprazole withdrawal dyskinesia by causing some degree of D2 receptor blockade. It may have decreased the duration of withdrawal dyskinesia by the same effect on D2 receptors. It may have lasted longer if aripiprazole was not replaced by another antipsychotic. This is particularly evident because dyskinesia improved quickly when quetiapine was titrated to 150 mg/d. The higher quetiapine dosage of 150 mg/d is closer to 5 mg/d of aripiprazole in terms of D2 receptor occupancy and affinity. However, quetiapine is weaker than aripiprazole in terms of D2 receptor occupancy at all dosages, and therefore less likely to cause EPS.16

Summing up

Withdrawal dyskinesia in the absence of a history of TD is a common symptom of antipsychotic discontinuation or dosage reduction after long-term use of an antipsychotic. It is more commonly seen with antipsychotics with high D2 receptor occupancy, and has been hypothesized to be related to D2 receptor supersensitivity to ambient dopamine, resulting as a compensatory response to chronic D2 blockade by this class of medication.

Evidence suggests that reversible withdrawal dyskinesia could represent a prodrome to irreversible TD. Therefore, keeping a watchful eye for these movements during the exam, along with specific inquiry about withdrawal dyskinesias while taking a history at every follow-up visit, is important because doing so can:

• inform the clinician about partial compliance or noncompliance to these medications, which could lead to treatment failure

• help prevent development of irreversible TD syndrome.

Ms. X’s case reminds clinicians (1) to be aware of this unexpected side effect occurring even with second-generation antipsychotics and (2) that they should consider EPS in patients while they are discontinuing their drugs. Furthermore, it is important for clinical and medicolegal reasons to inform our patients that different forms of dyskinesias can be potential side effects of antipsychotics.

Bottom Line

Dyskinesias can result from withdrawal of both typical and atypical antipsychotics, and usually are self-limited. Withdrawal dyskinesia may represent a prodrome to tardive dyskinesia; early recognition may aid in preventing development of persistent tardive dyskinesia.

Related Resources

• Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. http://www.cqaimh.org/pdf/toolaims.pdf.

• Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2012.

• Tarsay D. Tardive dyskinesia: prevention and treatment. http:// www.uptodate.com/contents/tardive-dyskinesia-prevention-and-treatment?topicKey=NEURO%2F4908&elapsedTimeMs=3 &view=print&displayedView=full#.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Benztropine • Cogentin

Carvedilol • Coreg

Citalopram • Celexa

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Donepezil • Aricept

Enalapril • Vasotec

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthroid

Metformin • Glucophage

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Omeprazole • Prilosec

Pravastatin • Pravachol

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tetrabenazine • Xenazine

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zonisamide • Zonegran

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Insurer denies drug coverage

Ms. X, age 65, has a 35-year history of bipolar I disorder (BD I) characterized by psychotic mania and severe suicidal depression. For the past year, her symptoms have been well controlled with aripiprazole, 5 mg/d; trazodone, 50 mg at bedtime; and citalopram, 20 mg/d. Because her health insurance has changed, Ms. X asks to be switched to an alternative antipsychotic because the new provider denied coverage of aripiprazole.

While taking aripiprazole, Ms. X did not report any extrapyramidal side effects, including tardive dyskinesia. Her Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS) score is 4. No significant abnormal movements were noted on examination during previous medication management sessions.

We decide to replace aripiprazole with quetiapine, 50 mg/d. At a 2-week follow-up visit, Ms. X is noted to have euphoric mood and reduced need to sleep, flight of ideas, increased talkativeness, and paranoia. We also notice that she has significant tongue rolling and lip smacking, which she says started 10 days after changing from aripiprazole to quetiapine. Her AIMS score is 17.

What could be causing Ms. X’s tongue rolling and lip smacking?

a) an irreversible syndrome usually starting after 1 or 2 years of continuous exposure to antipsychotics

b) a self-limited condition expected to resolve completely within 12 weeks

c) an acute manifestation of an antipsychotic that can respond to an anticholinergic agent

d) none of the above

The authors’ observations

Tardive dyskinesia (TD) refers to at least moderate abnormal involuntary movements in ≥1 areas of the body or at least mild movements in ≥2 areas of the body, developing after ≥3 months of cumulative exposure (continuous or discontinuous) to dopamine D2 receptor-blocking agents.1 AIMS is a 14-item, clinician-administered questionnaire designed to evaluate such movements and track their severity over time. The first 10 items are rated on 5-point scale (0 = none; 1 = minimal; 2 = mild; 3 = moderate; 4 = severe), with items 1 to 4 assessing orofacial movements, 5 to 7 assessing extremity and truncal movements, and 8 to 10 assessing overall severity, impairment, and subjective distress. Items 11 to 13 assess dental status because lack of teeth can result in oral movements mimicking TDs. The last item assesses whether these movements disappear during sleep.

HISTORY Poor response

Ms. X was given a diagnosis of BD I at age 30; she first started taking antipsychotics 10 years later. Previous psychotropic trials included lamotrigine, divalproex sodium, risperidone, and ziprasidone, which were ineffective or poorly tolerated. Her medical history includes obstructive sleep apnea, narcolepsy, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, fibromyalgia, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and hypothyroidism. She takes metformin, omeprazole, pravastatin, carvedilol, insulin, levothyroxine, methylphenidate (for hypersomnia), and enalapril.

What is the next best step in management?

a) discontinue quetiapine

b) replace quetiapine with clozapine

c) increase quetiapine to target manic symptoms and reassess in a few weeks

d) continue quetiapine and treat abnormal movements with benztropine

TREATMENT Increase dosage

We increase quetiapine to 150 mg/d to target Ms. X’s manic symptoms. She is scheduled for a follow-up visit in 4 weeks but is instructed to return to the clinic earlier if her manic symptoms do not improve. At the 4-week follow-up visit, Ms. X does not have any abnormal movements and her manic symptoms have resolved. Her AIMS score is 4. Her husband reports that her abnormal movements resolved 4 days after increasing quetiapine to 150 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

Second-generation antipsychotics are known to have a lower risk of extrapyramidal adverse reactions compared with older first-generation antipsychotics.2,3 TD differs from other extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) because of its delayed onset. Risk factors for TD include:

• female sex

• age >50

• history of brain damage

• long-term antipsychotic use

• diagnosis of a mood disorder.

Gardos et al4 described 2 other forms of delayed dyskinesias related to antipsychotic use but resulting from antipsychotic discontinuation: withdrawal dyskinesia and covert dyskinesia. Evidence for these types of antipsychotic discontinuation syndromes mostly is anecdotal.5,6Table 1 highlights 3 different types of dyskinesias and their management.

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been described as a syndrome resembling TD that appears after discontinuation or dosage reduction of an antipsychotic in a patient who does not have an earlier TD diagnosis.7 The prevalence of withdrawal dyskinesia among patients undergoing antipsychotic discontinuation is approximately 30%.8 Cases of withdrawal dyskinesia are self-limited and resolve in 1 to 3 months.9,10 We believe that Ms. X’s movement disorder was withdrawal dyskinesia from aripiprazole because her symptoms started 10 days after the drug was discontinued, and was self-limited and reversible.

Similar to TD, withdrawal dyskinesia can present in different forms:

• tongue protrusion movements

• facial grimacing

• ticks

• chorea

• tremors

• athetosis

• involuntary vocalizations

• abnormal movements of hands and legs

• “dyspnea” due to involvement of respiratory musculature.5,11

There may be a sex difference in duration of withdrawal dyskinesias, because symptoms persist longer in females.9

Although covert dyskinesia also develops after discontinuation or dosage reduction of a dopamine-blocking agent, the symptoms usually are permanent, and could require reintroducing the antipsychotic or management with evidence-based treatments for TD, such as tetrabenazine or amantadine.6,12

What is the cause of Ms. X’s abnormal involuntary movements?

a) quetiapine-induced D2 receptor hypersensitivity

b) aripiprazole-induced cholinergic overactivity

c) quetiapine-induced cholinergic overactivity

d) aripiprazole-induced D2 receptor hypersensitivity

The authors’ observations

Pathophysiology of this condition is unknown but different theories have been proposed. D2 receptor up-regulation and hypersensitivity to compensate for chronic D2 receptor blockade by antipsychotics is a commonly cited theory.7,13 Discontinuation of an antipsychotic can make this D2 receptor up-regulation and hypersensitivity manifest as withdrawal dyskinesia by creating a temporary hyperdopaminergic state in basal ganglia. Other theories implicate decrease of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the globus pallidus (GP) and substantia nigra (SN) regions of the brain, and oxidative damage to GABAergic interneurons in GP and SN from excess production of catecholamines in response to chronic dopamine blockade.14

It has been proposed that patients with withdrawal dyskinesia might be in an early phase of D2 receptor modulation that, if continued because of use of the antipsychotic implicated in withdrawal dyskinesia, can lead to development of TD.4,7,8 A feature of withdrawal dyskinesia that differentiates it from TD is that it usually remits spontaneously within several weeks to a few months.4,7 Because of this characteristic, Schultz et al8 propose that, if withdrawal dyskinesia is identified early in treatment, it may be possible to prevent development of persistent TD.

Look carefully for dyskinetic movements in patients who have recently discontinued or decreased the dosage of their antipsychotic. Non-compliance and partial compliance are common problems among patients taking an antipsychotic.15 Therefore, careful watchfulness for withdrawal dyskinesias at all times can be beneficial. Inquiring about recent history of these dyskinesias in such patients is probably more useful than an exam because the dyskinesias may not be evident on exam when these patients show up for their follow-up visit, because of their self-limited nature.8

Treatment options

If a patient is noted to have a withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia, a clinician has options to prevent TD, including:

• decreasing the dosage of the antipsychotic

• switching from a typical antipsychotic to an atypical antipsychotic

• switching from one atypical to another with lesser affinity for striatal D2 receptor, such as clozapine or quetiapine.16,17

In addition, researchers are investigating the use of vitamin B6, Ginkgo biloba, amantadine, levetiracetam, melatonin, tetrabenazine, zonisamide, branched chain amino acids, clonazepam, and vitamin E as treatment alternatives for TD.

Tetrabenazine acts by blocking vesicular monoamine transporter type 2, thereby inhibiting release of monoamines, including dopamine into synaptic cleft area in basal ganglia.18 Clonazepam’s benefit for TD relates to its facilitation of GABAergic neurotransmission, because reduced GABAergic transmission in GP and SN has been associ ated with hyperkinetic movements, including TD.14Ginkgo biloba and melatonin exert their beneficial effects in TD through their antioxidant function.14

The agents listed in Table 219 could be used on a short-term basis for symptomatic treatment of withdrawal dyskinesias.1,18,20

Withdrawal dyskinesia has been reported with aripiprazole discontinuation and is thought to be related to aripiprazole’s strong affinity for D2 receptors.21 Aripiprazole at dosages of 15 to 30 mg/d can occupy more than 80% of the striatal D2 dopamine receptors. The dosage of ≥30 mg/d can lead to receptor occupancy of >90%.22 Studies have shown that EPS correlate with D2 receptor occupancy in steady-state conditions, and occupancy exceeding 80% results in these symptoms.22

Compared with aripiprazole, quetiapine has weak affinity for D2 receptors (Table 3), making it an unlikely culprit if dyskinesia emerges within 2 weeks of initation.22 We believe that, in Ms. X’s case, quetiapine might have masked the severity of aripiprazole withdrawal dyskinesia by causing some degree of D2 receptor blockade. It may have decreased the duration of withdrawal dyskinesia by the same effect on D2 receptors. It may have lasted longer if aripiprazole was not replaced by another antipsychotic. This is particularly evident because dyskinesia improved quickly when quetiapine was titrated to 150 mg/d. The higher quetiapine dosage of 150 mg/d is closer to 5 mg/d of aripiprazole in terms of D2 receptor occupancy and affinity. However, quetiapine is weaker than aripiprazole in terms of D2 receptor occupancy at all dosages, and therefore less likely to cause EPS.16

Summing up

Withdrawal dyskinesia in the absence of a history of TD is a common symptom of antipsychotic discontinuation or dosage reduction after long-term use of an antipsychotic. It is more commonly seen with antipsychotics with high D2 receptor occupancy, and has been hypothesized to be related to D2 receptor supersensitivity to ambient dopamine, resulting as a compensatory response to chronic D2 blockade by this class of medication.

Evidence suggests that reversible withdrawal dyskinesia could represent a prodrome to irreversible TD. Therefore, keeping a watchful eye for these movements during the exam, along with specific inquiry about withdrawal dyskinesias while taking a history at every follow-up visit, is important because doing so can:

• inform the clinician about partial compliance or noncompliance to these medications, which could lead to treatment failure

• help prevent development of irreversible TD syndrome.

Ms. X’s case reminds clinicians (1) to be aware of this unexpected side effect occurring even with second-generation antipsychotics and (2) that they should consider EPS in patients while they are discontinuing their drugs. Furthermore, it is important for clinical and medicolegal reasons to inform our patients that different forms of dyskinesias can be potential side effects of antipsychotics.

Bottom Line

Dyskinesias can result from withdrawal of both typical and atypical antipsychotics, and usually are self-limited. Withdrawal dyskinesia may represent a prodrome to tardive dyskinesia; early recognition may aid in preventing development of persistent tardive dyskinesia.

Related Resources

• Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. http://www.cqaimh.org/pdf/toolaims.pdf.

• Goldberg JF, Ernst CL. Managing the side effects of psychotropic medications. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2012.

• Tarsay D. Tardive dyskinesia: prevention and treatment. http:// www.uptodate.com/contents/tardive-dyskinesia-prevention-and-treatment?topicKey=NEURO%2F4908&elapsedTimeMs=3 &view=print&displayedView=full#.

Drug Brand Names

Amantadine • Symmetrel

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Benztropine • Cogentin

Carvedilol • Coreg

Citalopram • Celexa

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Clozapine • Clozaril

Divalproex sodium • Depakote

Donepezil • Aricept

Enalapril • Vasotec

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Levetiracetam • Keppra

Levothyroxine • Levoxyl, Synthroid

Metformin • Glucophage

Methylphenidate • Ritalin

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Omeprazole • Prilosec

Pravastatin • Pravachol

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tetrabenazine • Xenazine

Trazodone • Desyrel, Oleptro

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zonisamide • Zonegran

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bhidayasiri R1, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

2. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

3. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):414-425.

4. Gardos G, Cole JO, Tarsy D. Withdrawal syndromes associated with antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135(11):1321-1324.

5. Salomon C, Hamilton B. Antipsychotic discontinuation syndromes: a narrative review of the evidence and its integration into Australian mental health nursing textbooks. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2014;23(1):69-78.

6. Moseley CN, Simpson-Khanna HA, Catalano G, et al. Covert dyskinesia associated with aripiprazole: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36(4):128-130.

7. Anand VS, Dewan MJ. Withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia in a patient on risperidone undergoing dosage reduction. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1996;8(3):179-182.

8. Schultz SK, Miller DD, Arndt S, et al. Withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia during antipsychotic discontinuation. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38(11):713-719.

9. Degkwitz R, Bauer MP, Gruber M, et al. Time relationship between the appearance of persisting extrapyramidal hyperkineses and psychotic recurrences following sudden interruption of prolonged neuroleptic therapy of chronic schizophrenic patients [in German]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1970;20(7):890-893.

10. Sethi KD. Tardive dyskinesias. In: Adler CH, Ahlskog JE, eds. Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders: diagnosis and treatment guidelines for the practicing physician. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2000:331-338.

11. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

12. Horváth K, Aschermann Z, Komoly S, et al. Treatment of tardive syndromes [in Hungarian]. Psychiatr Hung. 2014;29(2):214-224.

13. Samaha AN, Seeman P, Stewart J, et al. “Breakthrough” dopamine supersensitivity during ongoing antipsychotic treatment leads to treatment failure over time. J Neurosci. 2007;27(11):2979-2986.

14. Thelma B, Srivastava V, Tiwari AK. Genetic underpinnings of tardive dyskinesia: passing the baton to pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9(9):1285-1306.

15. Keith SJ, Kane JM. Partial compliance and patient consequences in schizophrenia: our patients can do better. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1308-1315.

16. Lieberman JA, Saltz BL, Johns CA, et al. The effects of clozapine on tardive dyskinesia. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:503-510.

17. Farah A. Atypicality of atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(6):268-274.

18. Rana AQ, Chaudry ZM, Blanchet PJ. New and emerging treatments for symptomatic tardive dyskinesia. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:1329-1340.

19. Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, et al. Developing clinical guidelines. West J Med. 1999;170(6):348-351.

20. Cloud LJ, Zutshi D, Factor SA. Tardive dyskinesia: therapeutic options for an increasingly common disorder. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(1):166-176.

21. Urbano M, Spiegel D, Rai A. Atypical antipsychotic withdrawal dyskinesia in 4 patients with mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):705-707.

22. Pani L, Pira L, Marchese G. Antipsychotic efficacy: relationship to optimal D2-receptor occupancy. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(5):267-275.

1. Bhidayasiri R1, Fahn S, Weiner WJ, et al; American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: treatment of tardive syndromes: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;81(5):463-469.

2. Dolder CR, Jeste DV. Incidence of tardive dyskinesia with typical versus atypical antipsychotics in very high risk patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(12):1142-1145.

3. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):414-425.

4. Gardos G, Cole JO, Tarsy D. Withdrawal syndromes associated with antipsychotic drugs. Am J Psychiatry. 1978;135(11):1321-1324.

5. Salomon C, Hamilton B. Antipsychotic discontinuation syndromes: a narrative review of the evidence and its integration into Australian mental health nursing textbooks. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2014;23(1):69-78.

6. Moseley CN, Simpson-Khanna HA, Catalano G, et al. Covert dyskinesia associated with aripiprazole: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2013;36(4):128-130.

7. Anand VS, Dewan MJ. Withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia in a patient on risperidone undergoing dosage reduction. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1996;8(3):179-182.

8. Schultz SK, Miller DD, Arndt S, et al. Withdrawal-emergent dyskinesia in patients with schizophrenia during antipsychotic discontinuation. Biol Psychiatry. 1995;38(11):713-719.

9. Degkwitz R, Bauer MP, Gruber M, et al. Time relationship between the appearance of persisting extrapyramidal hyperkineses and psychotic recurrences following sudden interruption of prolonged neuroleptic therapy of chronic schizophrenic patients [in German]. Arzneimittelforschung. 1970;20(7):890-893.

10. Sethi KD. Tardive dyskinesias. In: Adler CH, Ahlskog JE, eds. Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders: diagnosis and treatment guidelines for the practicing physician. New York, NY: Humana Press; 2000:331-338.

11. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

12. Horváth K, Aschermann Z, Komoly S, et al. Treatment of tardive syndromes [in Hungarian]. Psychiatr Hung. 2014;29(2):214-224.

13. Samaha AN, Seeman P, Stewart J, et al. “Breakthrough” dopamine supersensitivity during ongoing antipsychotic treatment leads to treatment failure over time. J Neurosci. 2007;27(11):2979-2986.

14. Thelma B, Srivastava V, Tiwari AK. Genetic underpinnings of tardive dyskinesia: passing the baton to pharmacogenetics. Pharmacogenomics. 2008;9(9):1285-1306.

15. Keith SJ, Kane JM. Partial compliance and patient consequences in schizophrenia: our patients can do better. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1308-1315.

16. Lieberman JA, Saltz BL, Johns CA, et al. The effects of clozapine on tardive dyskinesia. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;158:503-510.

17. Farah A. Atypicality of atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(6):268-274.

18. Rana AQ, Chaudry ZM, Blanchet PJ. New and emerging treatments for symptomatic tardive dyskinesia. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2013;7:1329-1340.

19. Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, et al. Developing clinical guidelines. West J Med. 1999;170(6):348-351.

20. Cloud LJ, Zutshi D, Factor SA. Tardive dyskinesia: therapeutic options for an increasingly common disorder. Neurotherapeutics. 2014;11(1):166-176.

21. Urbano M, Spiegel D, Rai A. Atypical antipsychotic withdrawal dyskinesia in 4 patients with mood disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):705-707.

22. Pani L, Pira L, Marchese G. Antipsychotic efficacy: relationship to optimal D2-receptor occupancy. Eur Psychiatry. 2007;22(5):267-275.

What does molecular imaging reveal about the causes of ADHD and the potential for better management?

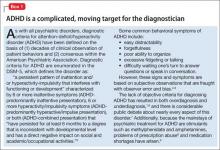

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common pediatric psychiatric disorders, occurring in approximately 5% of children.1 The disorder persists into adulthood in about one-half of those who are affected in childhood.2 In adults and children, diagnosis continues to be based on the examiner’s subjective assessment. (Box 13-9 describes how ADHD presents a complicated, moving target for the diagnostician.)

Patients who have ADHD are rarely studied with imaging; there are no established imaging findings associated with an ADHD diagnosis. Over the past 20 years, however, significant research has shown that molecular alterations along the dopaminergic−frontostriatal pathways occur in association with the behavioral constellation of ADHD symptoms—suggesting a pathophysiologic mechanism for this disorder.

In this article, we describe molecular findings from nuclear medicine imaging in ADHD. We also summarize imaging evidence for dysfunction of the dopaminergic-frontostriatal neural circuits as central in the pathophysiology of ADHD, with special focus on the dopamine reuptake transporter (DaT). Box 210,11 reviews our key observations and looks at the future of imaging in the management of ADHD.

Dopaminergic theory of ADHD

The executive functions that are disordered in ADHD (impulse control, judgment, maintaining attention) are thought to be centered in the infraorbital, dorsolateral, and medial frontal lobes. Neurotransmitters that have been implicated in the pathophysiology of ADHD include norepinephrine12 and dopamine13; medications that selectively block reuptake of these neurotransmitters are used to treat ADHD.14,15 Only the dopamine system has been extensively evaluated with molecular imaging techniques.

Because methylphenidate, a potent selective dopamine reuptake inhibitor, has been shown to reduce disordered executive functional behaviors in ADHD, considerable imaging research has focused on the dopaminergic neural circuits in the frontostriatal regions of the brain. The dopaminergic theory of ADHD is based on the hypothesis that alterations in the density or function of these circuits are responsible for behaviors that constitute ADHD.

Despite decades of efforts to delineate the underlying pathophysiology and neurochemistry of ADHD, no single unifying theory accounts for all imaging findings in all patients. This might be in part because of imprecision inherent in psychiatric diagnoses that are based on subjective observations. The behavioral criteria for ADHD can manifest in several disorders. For example, anxiety-related symptoms seen in posttraumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, and panic disorder also present as behaviors similar to those in ADHD diagnostic criteria.

Molecular imaging might provide a window into the underlying pathophysiology of ADHD and, by identifying objective findings, (1) allow for patient stratification based on underlying physiologic subtypes, (2) refine diagnostic criteria, and (3) predict treatment response.

Nuclear medicine findings

In general, nuclear medicine investigations of ADHD can be divided into studies of changes in regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) or glucose metabolism (rCGM) and those that have assessed the concentration of synaptic structures, using highly specific radiolabeled ligands. Both kinds of studies provide limited anatomic resolution, unless co-registered with MRI or CT scans and either single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) or positron emission tomography (PET).

Synaptic imaging using radiolabeled ligands with high biologic specificity for synaptic structures has high molecular resolution—that is, radiolabeled ligands used for selective imaging of the dopamine transporter or receptor do not identify serotonin transporters or receptors, and vice versa. (Details of SPECT and PET techniques are beyond the scope of this article but can be found in standard nuclear medicine textbooks.)

SPECT and PET of rCBF

Early investigations of rCBF in ADHD were performed using inhaled radioactive xenon-133 gas.16 Later, rCBF was assessed using fat-soluble radiolabeled ligands that rapidly distribute in the brain in proportion to blood flow by crossing the blood−brain barrier. Labeled with radioactive 99m-technetium, these ligands cross rapidly into brain cells after IV injection. Once intracellular, covalent bonds within the ligands cleave into 2 charged particles that do not easily recross the cell membrane. There is little redistribution of tracer after initial uptake.

The imaging data set that results can be reconstructed as (1) surface images, on which defects indicate areas of reduced rCBF, or (2) tomographic slices on which color scales indicate relative rCBF values (Figure 1). Because of the minimal redistribution of the tracer, SPECT images obtained 1 or 2 hours after injection provide a snapshot of rCBF at the time tracer is injected. Patients can be injected under various conditions, such as at rest with eyes and ears open in a dimly lit, quiet room, and then under cognitive stress (Figure 2), such as performing a computer-based attention and impulse control task, or during stimulant treatment.

Numerous investigators have found reduced frontal or striatal rCBF, or both, in patients with ADHD, unilaterally on the right17 or left,18,19 or bilaterally.20 Additionally, with stimulant therapy, normalization of striatal and frontal rCBF has been demonstrated14,19—changes that correlate with resolution of behavioral symptoms of ADHD with stimulant treatment.21

SPECT of 32 boys with previously untreated ADHD. Kim et al21 found that the presence of reduced right or left, or both, frontal rCBF, which normalized with 8 weeks of stimulant therapy, predicted symptom improvement in 85% of patients. Absence of improvement of reduced frontal rCBF had a 75% negative predictive value for treatment response. (Additionally, hyperperfusion of the somatosensory cortex has been demonstrated in children with ADHD,16,22 suggesting increased responsiveness to extraneous environmental input.)

SPECT of 40 untreated pediatric patients compared with 17 age-matched controls. Using SPECT, Lee et al23 reported rCBF reductions in the orbitofrontal cortex and the medial temporal gyrus of participants; reductions corresponded to areas of motor and impulsivity control. The researchers also demonstrated increased rCBF in the somatosensory area.

After methylphenidate treatment, blood flow to these areas normalized, and rCBF to higher visual and superior prefrontal areas decreased. Substantial clinical improvement occurred in 64% of patients—suggesting methylphenidate treatment of ADHD works by (1) increasing function of areas of the brain that control impulses, motor activity, and attention, and (2) reducing function to sensory areas that lead to distraction by extraneous environmental sensory input.

O-15-labeled water PET of 10 adults with ADHD. Schweitzer et al24 found that participants who demonstrated improvement in behavioral symptoms with chronic stimulant therapy had reduced rCBF in the striata at baseline—again, suggesting that baseline hypometabolism in the striata is associated with ADHD.

PET of regional cerebral glucose metabolism

Cerebral metabolism requires a constant supply of glucose; regional differences in cerebral glucose metabolism can be assessed directly with positron-emitting F-18-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose. Although metabolically inert, this agent is transported intracellularly similar to glucose; once phosphorylated within brain cells, however, it can no longer undergo further metabolism or redistribution.

Studies using PET to assess rCGM were some of the earliest molecular imaging applications in ADHD. Zametkin et al25 reported low global cerebral glucose utilization in adults, but not adolescents,26 with ADHD. However, further study, with normalization of the PET data, confirmed reduced rCGM in the left prefrontal cortex in both adolescents26 and adults,27 indicating hypometabolism of cortical areas associated with impulse control and attention in ADHD. In adolescents, symptom severity was inversely related to rCBF in the left anterior frontal cortex.

Synaptic imaging

Nuclear imaging has been used to study several components of the striatal dopaminergic synapse, including:

• dopamine substrates, using fluorine- 18-labeled dopa or carbon-11-labeled dopa

• dopamine receptors, using carbon- 11-labeled raclopride or iodine-123 iodobenzamide

• the tDaT, using iodine-123 ioflupane, 99m-technetium TRODAT, or carbon-11 cocaine (Figure 3).

All of these synaptic imaging agents were used mainly as research tools until 2011, when the FDA approved the SPECT imaging agent iodine-123 ioflupane (DaTscan) for clinical use in assessment of Parkinson’s disease.28 This commercially available agent has high specificity for the DaT, with little background activity noted on SPECT imaging (Figure 4).

Dopamine transporter imaging

Because the site of action of methylphenidate is the DaT, imaging this component of the striatal dopaminergic synapse has been an area of intense investigation in ADHD. Located almost exclusively in the striata, DaT reduces synaptic concentrations of dopamine by means of reuptake channels in the cell membrane.29 By reversibly binding to, and occupying sites on, the DaT, methylphenidate impedes dopamine reuptake, which results in increased availability of dopamine at the synapse.30

By demonstrating an increase in striatal DaT density in patients with ADHD— first reported by Dougherty et al31 using iodine-123 altropane (a dopaminergic uptake inhibitor) in 6 adults with ADHD—investigators have hypothesized that excessive expression of the DaT protein in the striata, which may result from genetic or environmental factors, is a central causative agent of ADHD.32 Subsequent studies, however, have yielded contradictory findings: Hesse et al,33 using SPECT imaging, and Volkow et al,34 using carbon-11 cocaine PET imaging, found reduced DaT density in, respectively, 9 and 26 patients with ADHD.

To clarify the role of DaT levels in the etiology of ADHD and to explain discrepant results, Fusar-Poli et al35 performed a meta-analysis of 9 published papers that reported the results of DaT imaging in a total of 169 ADHD patients and 129 controls. They noted that these studies included 6 different imaging agents and protocols. Patients were stimulant therapy-naïve (n = 137) or drug-free (refrained from stimulant therapy for a time [n = 32]). The team found that the degree of elevation of the striatal DaT concentration correlated with a history of stimulant exposure, and that the drug-naïve group had a reduced DaT level.

Fusar-Poli’s hypothesis? Elevated DaT levels result from up-regulation in the presence of chronic methylphenidate therapy, which accounts for early reports that demonstrated increased striatal DaT density. Clinically, up-regulation might explain the lack of sustained relief of behavioral symptoms with stimulant therapy in 20% of patients with ADHD who showed clinical improvement initially.36

Only limited conclusions can be drawn about the role of DaT levels in ADHD, given the small number of patients studied in published reports. In addition, the Fusar-Poli meta-analysis has come under strong criticism because of methodological errors with improper patient inclusion and characterization of treatment status,37 calling into question the investigators’ conclusions.

Does the DaT level hold promise for practice? Despite a lack of clarity about the significance of DaT level in the etiology of ADHD, knowledge of a patient’s level might prove useful in predicting which patients will respond to methylphenidate. Namely, several researchers have found that:

• an elevated baseline level of DaT (before stimulant therapy) correlates with robust clinical response

• absence of an elevated baseline DaT level suggests that symptomatic improvement with stimulant therapy in unlikely.38-40

Dresel et al38 evaluated 17 drug-naïve adults, newly diagnosed with ADHD, using 99m-technetium TRODAT SPECT before and after methylphenidate therapy. They found a 15% increase in specific DaT binding in patients with ADHD, compared with controls, at baseline. After treatment, the researchers observed a 28% reduction in specific DaT binding—a significant change from baseline that correlated with behavioral response.

Study: SPECT in 18 adults with ADHD given methylphenidate. Krause39 used the same SPECT agent to study 18 adults before they received methylphenidate and 10 weeks after treatment. Participants were categorized as responders or nonresponders based on clinical assessment of ADHD symptoms after those 10 weeks. All 12 responders had an elevated striatal DaT concentration at baseline. Of the 6 nonresponders, 5 had a normal level of striatal DaT compared with age-matched controls.

Study: 22 Adult ADHD patients evaluated with 99m-technetium TRODAT SPECT. The same group of investigators40 presented imaging findings in 22 additional adult patients. Seventeen had an elevated striatal DaT level, 16 of whom responded to stimulant therapy. The remaining 5 patients had reduced striatal DaT at baseline; none had a good clinical response to methylphenidate.

The positive clinical response to methylphenidate in 67%37 and 77%40 of patients is in good agreement with results from larger studies, which reported that approximately 75% of patients with ADHD show prompt clinical improvement with stimulants.41 Improvement might be related to an increase in functioning of the frontostriatal dopaminergic circuit that is seen with stimulant therapy. Increased availability of dopamine at the synapse, resulting from stimulant blockade of the dopamine reuptake transporter, produces increased dopamine neurotransmission and increased activation of frontostriatal circuits.

In another study, rCBF in frontostriatal circuits was determined to be inversely proportional to DaT density; rCBF normalized with stimulant therapy.42

Will imaging pave the way for therapeutic stratification? Baseline determinations of striatal DaT concentration with SPECT imaging might make it possible to stratify patients with ADHD symptoms into those likely to show significant behavioral symptom response to methylphenidate and those who are not likely to respond. There might be an objective imaging finding—striatal DaT density—that allows clinicians to distinguish stimulant-responsive ADHD from stimulant-unresponsive ADHD.

Dopamine substrate imaging

Radiolabeled dopa (carbon-11 or fluorine-18) is transported into presynaptic dopaminergic neurons in the striatum, where it is decarboxylated, converted to radio-dopamine, and stored within vesicles until released in response to neuronal excitation. Semi-quantitative assessment is achieved with calculation of specific (striatal) to nonspecific (background) uptake ratios. Increased values are thought to indicate increased density of dopaminergic neurons.43

Ernst et al44 reported a 50% decrease in specific fluorine-18 dopa uptake in the left prefrontal cortex in 17 drug-naïve adults with ADHD, compared with 23 controls. The same team reported increased midbrain fluorine-18 dopa levels in 10 adolescents with ADHD—48% higher, overall, than what was seen in 10 controls.43 They hypothesized that these opposite results were the results of a reduction in the dopaminergic neuronal density in adults, which might be part of the natural history of ADHD, or a normal age-related reduction in neuronal density, or both. Increased dopa levels in the team’s adolescent group were hypothesized to reflect up-regulation in dopamine synthesis due to low synaptic dopamine concentrations that might result from increased dopamine reuptake.

Dopamine-receptor imaging

The 5 distinct dopamine receptors (D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5) can be grouped into 2 subtypes, based on their coupling with G proteins. D1 and D5 constitute a group; D2, D3, and D4, a second group.

The D1 receptor is the most common dopamine receptor in the brain and is widely distributed in the striatum and prefrontal cerebral cortex. D1 receptor knockout mice demonstrate hyperactivity and poorer performance on learning tasks and are used as an animal model for ADHD.45 D1 has been imaged using C-11 SCH 23390 PET46 in rats, but its role in ADHD has yet to be evaluated. D5 is the most recently cloned and most widely distributed of the known dopamine receptors; however, there are no imaging studies of the D5 receptor.13

D2 receptors are present in presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons47 in the neocortex, substantia nigra, nucleus accumbens, and olfactory tubercle, as well as in other structures.48 Presynaptic D2 receptors act as autoregulators, inhibiting dopaminergic synthesis, firing rate, and release.49

Using C-11 raclopride PET imaging, Lou et al50 reported high D2/3 receptor availability in adolescents who had a history of perinatal cerebral ischemia. They found that this availability is associated with an increase in the severity of ADHD symptoms. They proposed that the increase in “empty” receptor density might have been caused by perinatal ischemia-induced presynaptic dopaminergic neuronal loss or an increase in presynaptic dopamine reuptake (Figure 550). Either mechanism could result in up-regulation in postsynaptic D2/3 receptors.

Volkow et al51 reported that D2 receptor density correlated with methylphenidate-induced changes in rCBF in frontal and temporal lobes in humans. They postulated that the variable therapeutic effects of methylphenidate seen in ADHD patients might be related to variations in baseline D2 receptor availability.

Lou et al50 reported elevated D2 receptor density, demonstrated using carbon-11 raclopride, in children with ADHD, compared with normal adults.

Further support for a relationship between D2-receptor density and symptomatic improvement with methylphenidate in ADHD was presented by Ilgin et al52 using iodine-123 iodobenzamide SPECT. They found elevated D2 receptor levels in 9 drug-naïve children with ADHD, which is 20% to 60% above what is seen in unaffected children. They noted that these patients showed improvement in hyperactivity when treated with methylphenidate.

In a similar study of 20 drug-naïve adults, Volkow et al53 found that durable symptomatic improvement with methylphenidate therapy was associated with increased D2 receptor availability.

Summing up

Striatal DaT is the most likely synaptic target for stratifying patients with ADHD, now that a dopamine transporter imaging agent is available commercially. Stratification might allow for refinement in the diagnostic categorization of ADHD, with introduction of stimulant-responsive and stimulant-unresponsive subtypes that are based on DaT imaging findings.

Bottom Line

Given recent advances showing molecular alterations in the dopaminergic-frontostriatal pathway as central to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, molecular imaging might be useful as an objective study for diagnosis.

Related Resources

• Schweitzer JB, Lee DO, Hanford RB, et al. A positron emission tomography study of methylphenidate in adults with ADHD: alterations in resting blood flow and predicting treatment response. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28(5):967-973.

• Raz A. Brain imaging data of ADHD. Psychiatric Times. http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/adhd/brain-imaging-data-adhd.

Drug Brand Names

Iodine-123 ioflupane • Methylphenidate • Ritalin DaTscan

Acknowledgment

Kylee M. L. Unsdorfer, a medical student at Northeast Ohio Medical University, helped prepare the manuscript of this article.

Disclosures

Dr. Thacker reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dr. Binkovitz received 4 doses of ioflupane I123I (DaTscan) from General Electric for investigator-initiated research, used for animal imaging in 2012.

1. Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942-948.

2. Simon V, Czobor P, Bálint S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;194(3):204-211.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Berger I. Diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: much ado about something. Isr Med Assoc J. 2011;13(9):571-574.

5. Schonwald A, Lechner E. Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: complexities and controversies. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(2):189-195.

6. Rousseau C, Measham T, Bathiche-Suidan M. DSM IV, culture and child psychiatry. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;17(2):69-75.

7. Taylor-Klaus E. Bringing the ADHD debate into sharper focus: part 1. The Huffington Post. http:// www.huffingtonpost.com/elaine-taylorklaus/adhd-debate_b_4571097.html. Updated March 17, 2014. Accessed August 18, 2015.

8. Sweeney CT, Sembower MA, Ertischek MD, et al. Nonmedical use of prescription ADHD stimulants and preexisting patterns of drug abuse. J Addict Dis. 2013;32(1):1-10.

9. Hitt E. Multiple reports of ADHD drug shortages. Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/742686. Published May 13, 2011. Accessed June 4, 2015.

10. Rubia K, Alegria AA, Cubillo AI, et al. Effects of stimulants on brain function in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2014;76(8):616-628.

11. Cortese S, Kelly C, Chabernaud C, et al. Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(10):1038-1055.

12. Garnock-Jones KP, Keating GM. Atomoxetine: a review of its use in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Paediatr Drugs. 2009;11(3):203-226.

13. Wu J, Xiao H, Sun H, et al. Role of dopamine receptors in ADHD: a systematic meta-analysis. Mol Neurobiol. 2012; 45(3):605-620.

14. Del Campo N, Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ, et al. The roles of dopamine and noradrenaline in the pathophysiology and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(12):e145-e157.

15. Berridge CW, Devilbiss DM. Psychostimulants as cognitive enhancers: the prefrontal cortex, catecholamines, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69(12):e101-e111.

16. Lou HC, Henriksen L, Bruhn P. Focal cerebral hypoperfusion in children with dysphasia and/or attention deficit disorder. Arch Neurol. 1984;41(8):825-829.

17. Gustafsson P, Thernlund G, Ryding E, et al. Associations between cerebral blood-flow measured by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), electro-encephalogram (EEG), behaviour symptoms, cognition and neurological soft signs in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Acta Paediatr. 2000;89(7):830-835.

18. Sieg KG, Gaffney GR, Preston DF, et al. SPECT brain imaging abnormalities in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Clin Nucl Med. 1995;20(1):55-60.

19. Spalletta G, Pasini A, Pau F, et al. Prefrontal blood flow dysregulation in drug naive ADHD children without structural abnormalities. J Neural Transm. 2001;108(10):1203-1216.

20. Amen DG, Carmichael BD. High-resolution brain SPECT imaging in ADHD. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1997;9(2):81-86.

21. Kim BN, Lee JS, Cho SC, et al. Methylphenidate increased regional cerebral blood flow in subjects with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Yonsei Med J. 2001;42(1):19-29.

22. Lou HC, Henriksen L, Bruhn P, et al. Striatal dysfunction in attention deficit and hyperkinetic disorder. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(1):48-52.

23. Lee JS, Kim BN, Kang E, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: comparison before and after methylphenidate treatment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;24(3):157-164.