User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Masters of American Psychiatry: Eric R. Kandel, MD

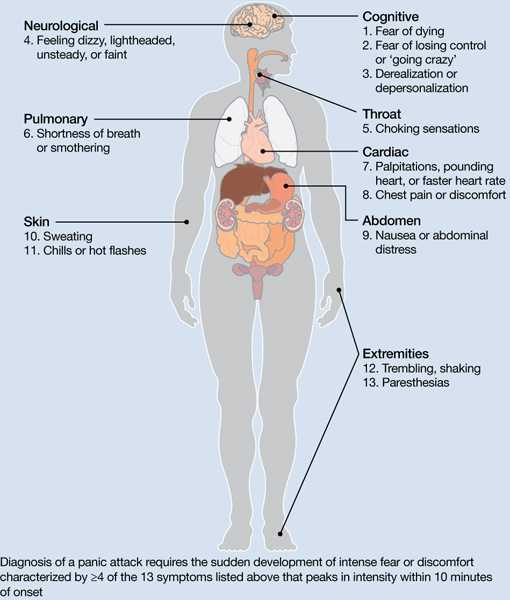

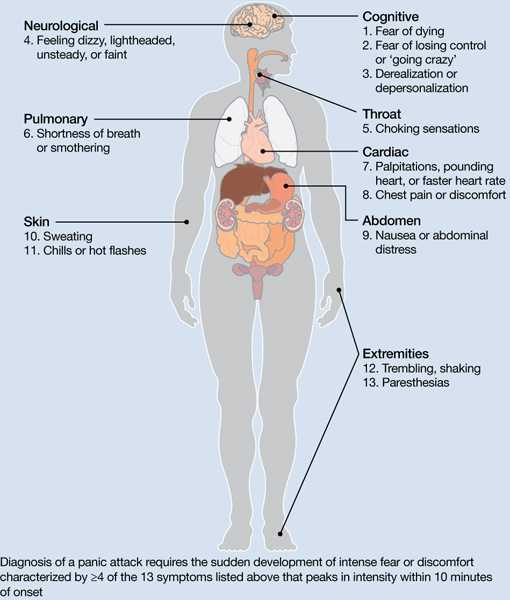

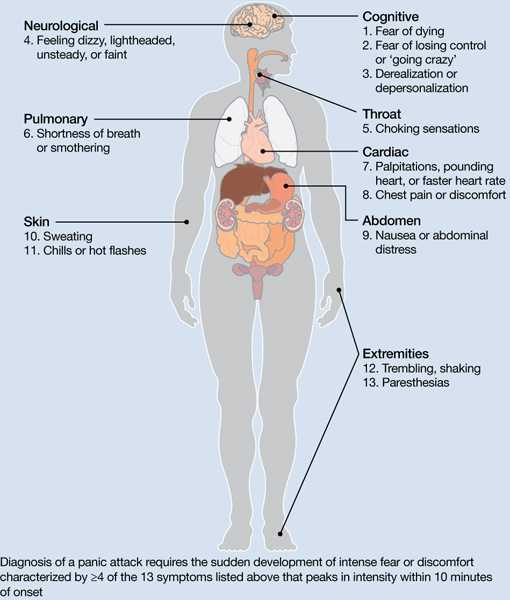

Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment options for panic disorder

Something smells different

CASE: Depressed and hopeless

Ms. D, age 69, has a 20-year history of bipolar II disorder, for which she is taking citalopram, 30 mg/d. She presents to her outpatient psychotherapist with a chief complaint of depressed mood. The therapist refers her for psychiatric hospitalization and electroconvulsive therapy consultation. Upon admission, Ms. D reports that her depressed mood has worsened over the past 5 weeks after a trip to the Dominican Republic. Ms. D had a negative encounter with airport security that she attributed to her 2 artificial knees and caused her to miss her flight. She endorses poor appetite, loss of energy, anhedonia, difficulty concentrating, poor memory, and feelings of hopelessness.

Ms. D reports increasingly frequent panic attacks as well as intermittent right-sided discomfort, unusual noxious smells, and increased falls. She says the falls likely are a result of new bilateral lower extremity weakness coupled with long-standing imbalance. Ms. D says she has experienced brief occasions of foul-smelling odors while showering without evidence of an offending substance. She also reports a mild, occipitally located headache.

Four years ago, Ms. D was hospitalized for a depressive episode without psychotic features and diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, for which she is taking clonazepam, 1.5 mg/d. Her last hypomanic episode was several years ago, and was characterized by increased energy with decreased need for sleep, flight of ideas, increased productivity, and impulsivity. Her medical history includes non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, chronic low back pain, hyperlipidemia, arthritis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease; her medications include pioglitazone, 30 mg/d, oxybutynin, 15 mg/d, rosuvastatin, 20 mg/d, losartan, 50 mg/d, and omeprazole, 20 mg/d. She also had bilateral knee replacements 9 years ago and an L4-S1 spinal fusion 11 years ago. She has no history of head injuries or seizures. Ms. D’s father had major depressive disorder, her mother died of a cerebrovascular accident at an unknown age, and her brother died of a myocardial infarction at age 52.

The authors’ observations

A striking aspect of Ms. D’s presenting complaints was her intermittent experience of foul smells. Although olfactory hallucinations can occur with psychotic and affective states, they also may be harbingers of an organic etiology involving the temporal lobe.1 Olfactory hallucinations associated with a psychiatric disorder often have an accompanying delusional belief regarding the cause of the smell.2

Olfactory hallucinations have been associated with migraines, epilepsy, and Parkinson’s disease.1-3 Neoplasms, cerebrovascular events, or traumatic brain injuries that result in focal mesial temporal lobe lesions can present as a partial complex seizure with olfactory or gustatory hallucinations and progress to automatisms.4 Characteristic odors in these hallucinations are unpleasant; patients with temporal lobe epilepsy describe the smells as “bad,” “rotten,” “sickening,” and “like burning food.”2 Ms. D’s report of unusual smells warranted consideration of an organic etiology for her mood change and a thorough neurologic examination.

EVALUATION: Neurologic signs

At the time of admission, Ms. D has a blood pressure of 127/68 mm Hg, heart rate of 74 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and temperature of 36.5°C. Neurologic examination reveals a left facial droop of unknown duration. Motor strength is weak throughout with left-sided focal weakness. Ms. D’s daughter notes that her mother’s smile appears “funny” in her admission photograph but is unsure when the asymmetry in her facial appearance began. Ms. D had been ambulatory before admission. Nursing staff observes Ms. D leans toward her left side and exhibits possible left-sided neglect during the first 12 hours of hospitalization.

When asked about her facial droop, Ms. D replies that she had not noticed any change in her appearance lately. She does not appear to be concerned about her worsening ambulation. On hospital day 2, Ms. D seems to have difficulty using utensils to eat breakfast. Ms. D is dismissive of her worsening motor function and asks to be left alone to finish her meal.

The authors’ observations

Ms. D’s focal neurologic deficits and complaint of a headache on admission were concerning because they could be caused by a cerebrovascular event or space-occupying brain lesion with potential for increased intracranial pressure. Neurologic examination with evaluation for papilledema is indicated, followed by medical transport to the closest medical center for emergent brain imaging. Neither Ms. D nor her daughter could pinpoint the onset of Ms. D’s left-sided facial droop, which precluded administering tissue plasminogen activator for a potential acute ischemic stroke.5

Ms. D’s case prompted us to consider what constitutes timely brain imaging in a patient who presents with psychiatric symptoms. Several neurologic conditions may present first with neurobehavioral symptoms before findings on physical exam. Two series of autopsies conducted >70 years ago at psychiatric hospitals found incidences of brain tumors of 3.45%6 and 13.5%.7 In a 5-year retrospective study, 21% of meningioma cases presented with psychiatric symptoms alone.8 These historical cases suggest that affective, behavioral, and psychotic symptoms may be the only clinical indicators of brain lesions that merit surgery.9-11

Imaging and radiation exposure

With the advent of CT scans in the 1970s, psychiatrists gained a new method of investigating potential structural CNS pathology in patients presenting with psychiatric symptoms. The dramatic increase in CT scan use in recent years and resulting radiation exposure is responsible for 1.5% to 2% of all cancers in the United States.12,13 Certainly, physicians must balance the advantage of early detection of brain lesions with cost-effectiveness and exposure to radiation.14

There is no consensus regarding use of brain imaging in a patient who presents with new-onset psychiatric symptoms. Certainly, patients with localizing neurologic deficits or symptoms of increased intracranial pressure should undergo brain imaging. As for psychiatric patients without neurologic findings, Filley and Kleinschmidt-DeMasters15 provide recommendations based on their 1995 case series, and other authors have recommended imaging for patients age ≥4016 vs ≥5017,18 who present with atypical mental status changes.

OUTCOME: Scan, then surgery

Ms. D’s head CT reveals a large right-sided temporoparietal low-density lesion with 8-mm left lower midline shift (Figure). She undergoes a right temporal craniotomy with resection of the mass, which is confirmed by surgical pathology to be a glioblastoma multiforme World Health Organization grade 4 tumor. Postoperative MRI shows evidence of infarction in the right posterior cerebral artery distribution and residual tumor is identified on follow-up imaging. Ms. D is referred to radiation oncology, where she receives a prognostic median life expectancy of 14 months with radiation and temozolomide treatment.19

Figure: Ms. D’s MRI results

MRI with contrast shows a large right temporal heterogeneous mass consistent with glioblastoma multiforme

The authors’ observations

Glioblastoma is a rare cancer that comprises 25% of all malignant nervous system tumors.20 It is associated with a poor prognosis, with a <30% relative survival rate for adults at 1 year and 3% at 5 years.20 Headaches, seizures, motor weakness, and progressive neurologic deficits are common symptoms of glioblastoma at diagnosis.20 Ms. D was offered the standard of care treatment for a high-grade glioma, including surgical resection followed by concomitant external-beam radiotherapy and chemotherapy.21

Consider structural brain lesions in patients who present with neurobehavioral symptoms, although most of these patients will be diagnosed with a primary psychiatric disorder. Ms. D had a known psychiatric disorder that predated the onset of neurologic symptoms and diagnosis of a rare brain cancer. Before she developed neurologic signs, Ms. D experienced symptoms uncharacteristic of her previous depressive episodes, including olfactory hallucinations, that provided an early indicator of a CNS lesion. Consider brain imaging in patients of any age who do not respond to medications targeting the presumed psychiatric diagnosis to ensure that insidious brain tumors are not missed (Table 1).15

Table 1

When to order neuroimaging for psychiatric patients

| Patient’s age | Most common types of brain tumor | MRI vs CT | Indications to image |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥40 years | Metastases High-grade gliomas Meningiomas | Roughly equivalent for imaging common tumor types. Base on cost, availability, and relative patient contraindications | New-onset cognitive or emotional dysfunction. Patient is not responding to appropriate pharmacotherapy for psychiatric diagnosis |

| <40 years | Low-grade astrocytomas Oligodendrogliomas | MRI preferred | New-onset cognitive or emotional dysfunction with associated somatic symptoms (headache, nausea, vomiting, papilledema, seizures, or focal deficits). Patient is not responding to appropriate pharmacotherapy for the psychiatric diagnosis |

| Source: Reference 15 | |||

Compared with cerebrovascular lesions, neoplasms are more difficult to clinically correlate with their anatomic location. Neurobehavioral symptoms are more frequently associated with tumors originating in the frontal lobe or temporolimbic regions of the brain. The 3 types of frontal lobe syndromes are dorsolateral, orbitofrontal, and medial-frontal (Table 2).15 Temporolimbic tumors may present with hallucinations, mania, panic attacks, or amnesia. A meta-analysis found a statistically significant association between anorexia and hypothalamic tumors.22 Reports of neuropsychiatric symptoms that respond to pharmacologic treatment further confound the clinical picture.16

Table 2

Frontal lobe syndromes

| Syndrome | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Dorsolateral | Deficits in executive functioning, including organization and behavior planning |

| Orbitofrontal | Prominent disinhibition |

| Medial-frontal | Apathy, abulia |

| Source: Reference 15 | |

It is uncommon for a patient with a long-standing mood disorder to develop a primary brain cancer. However, Ms. D’s case serves as an important reminder to consider medical comorbidities in our aging psychiatric population. In particular, a patient who develops unusual symptoms or does not respond to previously effective treatments should be more closely examined and the differential diagnosis broadened.

Related Resources

- MD Anderson Cancer Center. Brain tumor videos and podcasts. www.mdanderson.org/patient-and-cancer-information/cancer-information/cancer-types/brain-tumor/videos-and-podcasts/index.html.

- Braun CM, Dumont M, Duval J, et al. Brain modules of hallucination: an analysis of multiple patients with brain lesions. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003;28(6):432-449.

Drug Brand Names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Losartan • Cozaar

- Omeprazole • Prilosec

- Oxybutynin • Ditropan

- Pioglitazone • Actos

- Rosuvastatin • Crestor

- Temozolomide • Temodar

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Assad G, Shapiro B. Hallucinations: theoretical and clinical overview. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(9):1088-1097.

2. Carter JL. Visual somatosensory, olfactory, and gustatory hallucinations. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15(2):347-358.

3. Fuller GN, Guiloff RJ. Migrainous olfactory hallucinations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50(12):1688-1690.

4. Chang BS, Lowenstein DH. Mechanisms of disease: epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(13):1257-1266.

5. Lansberg MG, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN. Efficacy and safety of tissue plasminogen activator 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke: a metaanalysis. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2438-2441.

6. Hoffman JL. Intracranial neoplasms: their incidence and mental manifestations. Psychiatr Q. 1937;11(4):561-575.

7. Larson CP. Intracranial tumors in mental hospital patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1940;97(1):49-58.

8. Gupta RK, Kumar R. Benign brain tumours and psychiatric morbidity: a 5-years retrospective data analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38(5):316-319.

9. Chambers WR. Neurosurgical conditions masquerading as psychiatric diseases. Am J Psychiatry. 1955;112(5):387-389.

10. Trimble MR, Mendez MF, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric symptoms from the temporolimbic lobes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9(3):429-438.

11. Uribe VM. Psychiatric symptoms and brain tumor. Am Fam Physician. 1986;34(2):95-98.

12. Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(2):2277-2284.

13. Berrington de González A, Mahesh M, Kim KP, et al. Projected cancer risks from computed tomographic scans performed in the United States in 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2071-2077.

14. Weinberger DR. Brain disease and psychiatric illness: when should a psychiatrist order a CAT scan? Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(12):1521-1526.

15. Filley CM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Neurobehavioral presentations of brain neoplasms. West J Med. 1995;163(1):19-25.

16. Moise D, Madhusoodanan S. Psychiatric symptoms associated with brain tumors: a clinical engima. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(1):28-31.

17. Bunevicius A, Deltuva VP, Deltuviene D, et al. Brain lesions manifesting as psychiatric disorders: eight cases. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):950-958.

18. Hollister LE, Boutros N. Clinical use of CT and MR scans in psychiatric patients. J Psychiatr Neurosci. 1991;16(4):194-198.

19. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987-996.

20. Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Franceschi E, et al. Glioblastoma in adults. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;67(2):139-152.

21. Chandana SR, Movva S, Arora M, et al. Primary brain tumors in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(10):1423-1430.

22. Madhusoodanan S, Opler MG, Moise D, et al. Brain tumor location and psychiatric symptoms: is there any association? A meta-analysis of published case studies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(10):1529-1536.

CASE: Depressed and hopeless

Ms. D, age 69, has a 20-year history of bipolar II disorder, for which she is taking citalopram, 30 mg/d. She presents to her outpatient psychotherapist with a chief complaint of depressed mood. The therapist refers her for psychiatric hospitalization and electroconvulsive therapy consultation. Upon admission, Ms. D reports that her depressed mood has worsened over the past 5 weeks after a trip to the Dominican Republic. Ms. D had a negative encounter with airport security that she attributed to her 2 artificial knees and caused her to miss her flight. She endorses poor appetite, loss of energy, anhedonia, difficulty concentrating, poor memory, and feelings of hopelessness.

Ms. D reports increasingly frequent panic attacks as well as intermittent right-sided discomfort, unusual noxious smells, and increased falls. She says the falls likely are a result of new bilateral lower extremity weakness coupled with long-standing imbalance. Ms. D says she has experienced brief occasions of foul-smelling odors while showering without evidence of an offending substance. She also reports a mild, occipitally located headache.

Four years ago, Ms. D was hospitalized for a depressive episode without psychotic features and diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, for which she is taking clonazepam, 1.5 mg/d. Her last hypomanic episode was several years ago, and was characterized by increased energy with decreased need for sleep, flight of ideas, increased productivity, and impulsivity. Her medical history includes non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, chronic low back pain, hyperlipidemia, arthritis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease; her medications include pioglitazone, 30 mg/d, oxybutynin, 15 mg/d, rosuvastatin, 20 mg/d, losartan, 50 mg/d, and omeprazole, 20 mg/d. She also had bilateral knee replacements 9 years ago and an L4-S1 spinal fusion 11 years ago. She has no history of head injuries or seizures. Ms. D’s father had major depressive disorder, her mother died of a cerebrovascular accident at an unknown age, and her brother died of a myocardial infarction at age 52.

The authors’ observations

A striking aspect of Ms. D’s presenting complaints was her intermittent experience of foul smells. Although olfactory hallucinations can occur with psychotic and affective states, they also may be harbingers of an organic etiology involving the temporal lobe.1 Olfactory hallucinations associated with a psychiatric disorder often have an accompanying delusional belief regarding the cause of the smell.2

Olfactory hallucinations have been associated with migraines, epilepsy, and Parkinson’s disease.1-3 Neoplasms, cerebrovascular events, or traumatic brain injuries that result in focal mesial temporal lobe lesions can present as a partial complex seizure with olfactory or gustatory hallucinations and progress to automatisms.4 Characteristic odors in these hallucinations are unpleasant; patients with temporal lobe epilepsy describe the smells as “bad,” “rotten,” “sickening,” and “like burning food.”2 Ms. D’s report of unusual smells warranted consideration of an organic etiology for her mood change and a thorough neurologic examination.

EVALUATION: Neurologic signs

At the time of admission, Ms. D has a blood pressure of 127/68 mm Hg, heart rate of 74 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and temperature of 36.5°C. Neurologic examination reveals a left facial droop of unknown duration. Motor strength is weak throughout with left-sided focal weakness. Ms. D’s daughter notes that her mother’s smile appears “funny” in her admission photograph but is unsure when the asymmetry in her facial appearance began. Ms. D had been ambulatory before admission. Nursing staff observes Ms. D leans toward her left side and exhibits possible left-sided neglect during the first 12 hours of hospitalization.

When asked about her facial droop, Ms. D replies that she had not noticed any change in her appearance lately. She does not appear to be concerned about her worsening ambulation. On hospital day 2, Ms. D seems to have difficulty using utensils to eat breakfast. Ms. D is dismissive of her worsening motor function and asks to be left alone to finish her meal.

The authors’ observations

Ms. D’s focal neurologic deficits and complaint of a headache on admission were concerning because they could be caused by a cerebrovascular event or space-occupying brain lesion with potential for increased intracranial pressure. Neurologic examination with evaluation for papilledema is indicated, followed by medical transport to the closest medical center for emergent brain imaging. Neither Ms. D nor her daughter could pinpoint the onset of Ms. D’s left-sided facial droop, which precluded administering tissue plasminogen activator for a potential acute ischemic stroke.5

Ms. D’s case prompted us to consider what constitutes timely brain imaging in a patient who presents with psychiatric symptoms. Several neurologic conditions may present first with neurobehavioral symptoms before findings on physical exam. Two series of autopsies conducted >70 years ago at psychiatric hospitals found incidences of brain tumors of 3.45%6 and 13.5%.7 In a 5-year retrospective study, 21% of meningioma cases presented with psychiatric symptoms alone.8 These historical cases suggest that affective, behavioral, and psychotic symptoms may be the only clinical indicators of brain lesions that merit surgery.9-11

Imaging and radiation exposure

With the advent of CT scans in the 1970s, psychiatrists gained a new method of investigating potential structural CNS pathology in patients presenting with psychiatric symptoms. The dramatic increase in CT scan use in recent years and resulting radiation exposure is responsible for 1.5% to 2% of all cancers in the United States.12,13 Certainly, physicians must balance the advantage of early detection of brain lesions with cost-effectiveness and exposure to radiation.14

There is no consensus regarding use of brain imaging in a patient who presents with new-onset psychiatric symptoms. Certainly, patients with localizing neurologic deficits or symptoms of increased intracranial pressure should undergo brain imaging. As for psychiatric patients without neurologic findings, Filley and Kleinschmidt-DeMasters15 provide recommendations based on their 1995 case series, and other authors have recommended imaging for patients age ≥4016 vs ≥5017,18 who present with atypical mental status changes.

OUTCOME: Scan, then surgery

Ms. D’s head CT reveals a large right-sided temporoparietal low-density lesion with 8-mm left lower midline shift (Figure). She undergoes a right temporal craniotomy with resection of the mass, which is confirmed by surgical pathology to be a glioblastoma multiforme World Health Organization grade 4 tumor. Postoperative MRI shows evidence of infarction in the right posterior cerebral artery distribution and residual tumor is identified on follow-up imaging. Ms. D is referred to radiation oncology, where she receives a prognostic median life expectancy of 14 months with radiation and temozolomide treatment.19

Figure: Ms. D’s MRI results

MRI with contrast shows a large right temporal heterogeneous mass consistent with glioblastoma multiforme

The authors’ observations

Glioblastoma is a rare cancer that comprises 25% of all malignant nervous system tumors.20 It is associated with a poor prognosis, with a <30% relative survival rate for adults at 1 year and 3% at 5 years.20 Headaches, seizures, motor weakness, and progressive neurologic deficits are common symptoms of glioblastoma at diagnosis.20 Ms. D was offered the standard of care treatment for a high-grade glioma, including surgical resection followed by concomitant external-beam radiotherapy and chemotherapy.21

Consider structural brain lesions in patients who present with neurobehavioral symptoms, although most of these patients will be diagnosed with a primary psychiatric disorder. Ms. D had a known psychiatric disorder that predated the onset of neurologic symptoms and diagnosis of a rare brain cancer. Before she developed neurologic signs, Ms. D experienced symptoms uncharacteristic of her previous depressive episodes, including olfactory hallucinations, that provided an early indicator of a CNS lesion. Consider brain imaging in patients of any age who do not respond to medications targeting the presumed psychiatric diagnosis to ensure that insidious brain tumors are not missed (Table 1).15

Table 1

When to order neuroimaging for psychiatric patients

| Patient’s age | Most common types of brain tumor | MRI vs CT | Indications to image |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥40 years | Metastases High-grade gliomas Meningiomas | Roughly equivalent for imaging common tumor types. Base on cost, availability, and relative patient contraindications | New-onset cognitive or emotional dysfunction. Patient is not responding to appropriate pharmacotherapy for psychiatric diagnosis |

| <40 years | Low-grade astrocytomas Oligodendrogliomas | MRI preferred | New-onset cognitive or emotional dysfunction with associated somatic symptoms (headache, nausea, vomiting, papilledema, seizures, or focal deficits). Patient is not responding to appropriate pharmacotherapy for the psychiatric diagnosis |

| Source: Reference 15 | |||

Compared with cerebrovascular lesions, neoplasms are more difficult to clinically correlate with their anatomic location. Neurobehavioral symptoms are more frequently associated with tumors originating in the frontal lobe or temporolimbic regions of the brain. The 3 types of frontal lobe syndromes are dorsolateral, orbitofrontal, and medial-frontal (Table 2).15 Temporolimbic tumors may present with hallucinations, mania, panic attacks, or amnesia. A meta-analysis found a statistically significant association between anorexia and hypothalamic tumors.22 Reports of neuropsychiatric symptoms that respond to pharmacologic treatment further confound the clinical picture.16

Table 2

Frontal lobe syndromes

| Syndrome | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Dorsolateral | Deficits in executive functioning, including organization and behavior planning |

| Orbitofrontal | Prominent disinhibition |

| Medial-frontal | Apathy, abulia |

| Source: Reference 15 | |

It is uncommon for a patient with a long-standing mood disorder to develop a primary brain cancer. However, Ms. D’s case serves as an important reminder to consider medical comorbidities in our aging psychiatric population. In particular, a patient who develops unusual symptoms or does not respond to previously effective treatments should be more closely examined and the differential diagnosis broadened.

Related Resources

- MD Anderson Cancer Center. Brain tumor videos and podcasts. www.mdanderson.org/patient-and-cancer-information/cancer-information/cancer-types/brain-tumor/videos-and-podcasts/index.html.

- Braun CM, Dumont M, Duval J, et al. Brain modules of hallucination: an analysis of multiple patients with brain lesions. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003;28(6):432-449.

Drug Brand Names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Losartan • Cozaar

- Omeprazole • Prilosec

- Oxybutynin • Ditropan

- Pioglitazone • Actos

- Rosuvastatin • Crestor

- Temozolomide • Temodar

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE: Depressed and hopeless

Ms. D, age 69, has a 20-year history of bipolar II disorder, for which she is taking citalopram, 30 mg/d. She presents to her outpatient psychotherapist with a chief complaint of depressed mood. The therapist refers her for psychiatric hospitalization and electroconvulsive therapy consultation. Upon admission, Ms. D reports that her depressed mood has worsened over the past 5 weeks after a trip to the Dominican Republic. Ms. D had a negative encounter with airport security that she attributed to her 2 artificial knees and caused her to miss her flight. She endorses poor appetite, loss of energy, anhedonia, difficulty concentrating, poor memory, and feelings of hopelessness.

Ms. D reports increasingly frequent panic attacks as well as intermittent right-sided discomfort, unusual noxious smells, and increased falls. She says the falls likely are a result of new bilateral lower extremity weakness coupled with long-standing imbalance. Ms. D says she has experienced brief occasions of foul-smelling odors while showering without evidence of an offending substance. She also reports a mild, occipitally located headache.

Four years ago, Ms. D was hospitalized for a depressive episode without psychotic features and diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, for which she is taking clonazepam, 1.5 mg/d. Her last hypomanic episode was several years ago, and was characterized by increased energy with decreased need for sleep, flight of ideas, increased productivity, and impulsivity. Her medical history includes non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, chronic low back pain, hyperlipidemia, arthritis, and gastroesophageal reflux disease; her medications include pioglitazone, 30 mg/d, oxybutynin, 15 mg/d, rosuvastatin, 20 mg/d, losartan, 50 mg/d, and omeprazole, 20 mg/d. She also had bilateral knee replacements 9 years ago and an L4-S1 spinal fusion 11 years ago. She has no history of head injuries or seizures. Ms. D’s father had major depressive disorder, her mother died of a cerebrovascular accident at an unknown age, and her brother died of a myocardial infarction at age 52.

The authors’ observations

A striking aspect of Ms. D’s presenting complaints was her intermittent experience of foul smells. Although olfactory hallucinations can occur with psychotic and affective states, they also may be harbingers of an organic etiology involving the temporal lobe.1 Olfactory hallucinations associated with a psychiatric disorder often have an accompanying delusional belief regarding the cause of the smell.2

Olfactory hallucinations have been associated with migraines, epilepsy, and Parkinson’s disease.1-3 Neoplasms, cerebrovascular events, or traumatic brain injuries that result in focal mesial temporal lobe lesions can present as a partial complex seizure with olfactory or gustatory hallucinations and progress to automatisms.4 Characteristic odors in these hallucinations are unpleasant; patients with temporal lobe epilepsy describe the smells as “bad,” “rotten,” “sickening,” and “like burning food.”2 Ms. D’s report of unusual smells warranted consideration of an organic etiology for her mood change and a thorough neurologic examination.

EVALUATION: Neurologic signs

At the time of admission, Ms. D has a blood pressure of 127/68 mm Hg, heart rate of 74 beats per minute, respiratory rate of 16 breaths per minute, and temperature of 36.5°C. Neurologic examination reveals a left facial droop of unknown duration. Motor strength is weak throughout with left-sided focal weakness. Ms. D’s daughter notes that her mother’s smile appears “funny” in her admission photograph but is unsure when the asymmetry in her facial appearance began. Ms. D had been ambulatory before admission. Nursing staff observes Ms. D leans toward her left side and exhibits possible left-sided neglect during the first 12 hours of hospitalization.

When asked about her facial droop, Ms. D replies that she had not noticed any change in her appearance lately. She does not appear to be concerned about her worsening ambulation. On hospital day 2, Ms. D seems to have difficulty using utensils to eat breakfast. Ms. D is dismissive of her worsening motor function and asks to be left alone to finish her meal.

The authors’ observations

Ms. D’s focal neurologic deficits and complaint of a headache on admission were concerning because they could be caused by a cerebrovascular event or space-occupying brain lesion with potential for increased intracranial pressure. Neurologic examination with evaluation for papilledema is indicated, followed by medical transport to the closest medical center for emergent brain imaging. Neither Ms. D nor her daughter could pinpoint the onset of Ms. D’s left-sided facial droop, which precluded administering tissue plasminogen activator for a potential acute ischemic stroke.5

Ms. D’s case prompted us to consider what constitutes timely brain imaging in a patient who presents with psychiatric symptoms. Several neurologic conditions may present first with neurobehavioral symptoms before findings on physical exam. Two series of autopsies conducted >70 years ago at psychiatric hospitals found incidences of brain tumors of 3.45%6 and 13.5%.7 In a 5-year retrospective study, 21% of meningioma cases presented with psychiatric symptoms alone.8 These historical cases suggest that affective, behavioral, and psychotic symptoms may be the only clinical indicators of brain lesions that merit surgery.9-11

Imaging and radiation exposure

With the advent of CT scans in the 1970s, psychiatrists gained a new method of investigating potential structural CNS pathology in patients presenting with psychiatric symptoms. The dramatic increase in CT scan use in recent years and resulting radiation exposure is responsible for 1.5% to 2% of all cancers in the United States.12,13 Certainly, physicians must balance the advantage of early detection of brain lesions with cost-effectiveness and exposure to radiation.14

There is no consensus regarding use of brain imaging in a patient who presents with new-onset psychiatric symptoms. Certainly, patients with localizing neurologic deficits or symptoms of increased intracranial pressure should undergo brain imaging. As for psychiatric patients without neurologic findings, Filley and Kleinschmidt-DeMasters15 provide recommendations based on their 1995 case series, and other authors have recommended imaging for patients age ≥4016 vs ≥5017,18 who present with atypical mental status changes.

OUTCOME: Scan, then surgery

Ms. D’s head CT reveals a large right-sided temporoparietal low-density lesion with 8-mm left lower midline shift (Figure). She undergoes a right temporal craniotomy with resection of the mass, which is confirmed by surgical pathology to be a glioblastoma multiforme World Health Organization grade 4 tumor. Postoperative MRI shows evidence of infarction in the right posterior cerebral artery distribution and residual tumor is identified on follow-up imaging. Ms. D is referred to radiation oncology, where she receives a prognostic median life expectancy of 14 months with radiation and temozolomide treatment.19

Figure: Ms. D’s MRI results

MRI with contrast shows a large right temporal heterogeneous mass consistent with glioblastoma multiforme

The authors’ observations

Glioblastoma is a rare cancer that comprises 25% of all malignant nervous system tumors.20 It is associated with a poor prognosis, with a <30% relative survival rate for adults at 1 year and 3% at 5 years.20 Headaches, seizures, motor weakness, and progressive neurologic deficits are common symptoms of glioblastoma at diagnosis.20 Ms. D was offered the standard of care treatment for a high-grade glioma, including surgical resection followed by concomitant external-beam radiotherapy and chemotherapy.21

Consider structural brain lesions in patients who present with neurobehavioral symptoms, although most of these patients will be diagnosed with a primary psychiatric disorder. Ms. D had a known psychiatric disorder that predated the onset of neurologic symptoms and diagnosis of a rare brain cancer. Before she developed neurologic signs, Ms. D experienced symptoms uncharacteristic of her previous depressive episodes, including olfactory hallucinations, that provided an early indicator of a CNS lesion. Consider brain imaging in patients of any age who do not respond to medications targeting the presumed psychiatric diagnosis to ensure that insidious brain tumors are not missed (Table 1).15

Table 1

When to order neuroimaging for psychiatric patients

| Patient’s age | Most common types of brain tumor | MRI vs CT | Indications to image |

|---|---|---|---|

| ≥40 years | Metastases High-grade gliomas Meningiomas | Roughly equivalent for imaging common tumor types. Base on cost, availability, and relative patient contraindications | New-onset cognitive or emotional dysfunction. Patient is not responding to appropriate pharmacotherapy for psychiatric diagnosis |

| <40 years | Low-grade astrocytomas Oligodendrogliomas | MRI preferred | New-onset cognitive or emotional dysfunction with associated somatic symptoms (headache, nausea, vomiting, papilledema, seizures, or focal deficits). Patient is not responding to appropriate pharmacotherapy for the psychiatric diagnosis |

| Source: Reference 15 | |||

Compared with cerebrovascular lesions, neoplasms are more difficult to clinically correlate with their anatomic location. Neurobehavioral symptoms are more frequently associated with tumors originating in the frontal lobe or temporolimbic regions of the brain. The 3 types of frontal lobe syndromes are dorsolateral, orbitofrontal, and medial-frontal (Table 2).15 Temporolimbic tumors may present with hallucinations, mania, panic attacks, or amnesia. A meta-analysis found a statistically significant association between anorexia and hypothalamic tumors.22 Reports of neuropsychiatric symptoms that respond to pharmacologic treatment further confound the clinical picture.16

Table 2

Frontal lobe syndromes

| Syndrome | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Dorsolateral | Deficits in executive functioning, including organization and behavior planning |

| Orbitofrontal | Prominent disinhibition |

| Medial-frontal | Apathy, abulia |

| Source: Reference 15 | |

It is uncommon for a patient with a long-standing mood disorder to develop a primary brain cancer. However, Ms. D’s case serves as an important reminder to consider medical comorbidities in our aging psychiatric population. In particular, a patient who develops unusual symptoms or does not respond to previously effective treatments should be more closely examined and the differential diagnosis broadened.

Related Resources

- MD Anderson Cancer Center. Brain tumor videos and podcasts. www.mdanderson.org/patient-and-cancer-information/cancer-information/cancer-types/brain-tumor/videos-and-podcasts/index.html.

- Braun CM, Dumont M, Duval J, et al. Brain modules of hallucination: an analysis of multiple patients with brain lesions. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003;28(6):432-449.

Drug Brand Names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Losartan • Cozaar

- Omeprazole • Prilosec

- Oxybutynin • Ditropan

- Pioglitazone • Actos

- Rosuvastatin • Crestor

- Temozolomide • Temodar

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Assad G, Shapiro B. Hallucinations: theoretical and clinical overview. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(9):1088-1097.

2. Carter JL. Visual somatosensory, olfactory, and gustatory hallucinations. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15(2):347-358.

3. Fuller GN, Guiloff RJ. Migrainous olfactory hallucinations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50(12):1688-1690.

4. Chang BS, Lowenstein DH. Mechanisms of disease: epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(13):1257-1266.

5. Lansberg MG, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN. Efficacy and safety of tissue plasminogen activator 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke: a metaanalysis. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2438-2441.

6. Hoffman JL. Intracranial neoplasms: their incidence and mental manifestations. Psychiatr Q. 1937;11(4):561-575.

7. Larson CP. Intracranial tumors in mental hospital patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1940;97(1):49-58.

8. Gupta RK, Kumar R. Benign brain tumours and psychiatric morbidity: a 5-years retrospective data analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38(5):316-319.

9. Chambers WR. Neurosurgical conditions masquerading as psychiatric diseases. Am J Psychiatry. 1955;112(5):387-389.

10. Trimble MR, Mendez MF, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric symptoms from the temporolimbic lobes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9(3):429-438.

11. Uribe VM. Psychiatric symptoms and brain tumor. Am Fam Physician. 1986;34(2):95-98.

12. Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(2):2277-2284.

13. Berrington de González A, Mahesh M, Kim KP, et al. Projected cancer risks from computed tomographic scans performed in the United States in 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2071-2077.

14. Weinberger DR. Brain disease and psychiatric illness: when should a psychiatrist order a CAT scan? Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(12):1521-1526.

15. Filley CM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Neurobehavioral presentations of brain neoplasms. West J Med. 1995;163(1):19-25.

16. Moise D, Madhusoodanan S. Psychiatric symptoms associated with brain tumors: a clinical engima. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(1):28-31.

17. Bunevicius A, Deltuva VP, Deltuviene D, et al. Brain lesions manifesting as psychiatric disorders: eight cases. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):950-958.

18. Hollister LE, Boutros N. Clinical use of CT and MR scans in psychiatric patients. J Psychiatr Neurosci. 1991;16(4):194-198.

19. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987-996.

20. Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Franceschi E, et al. Glioblastoma in adults. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;67(2):139-152.

21. Chandana SR, Movva S, Arora M, et al. Primary brain tumors in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(10):1423-1430.

22. Madhusoodanan S, Opler MG, Moise D, et al. Brain tumor location and psychiatric symptoms: is there any association? A meta-analysis of published case studies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(10):1529-1536.

1. Assad G, Shapiro B. Hallucinations: theoretical and clinical overview. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(9):1088-1097.

2. Carter JL. Visual somatosensory, olfactory, and gustatory hallucinations. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1992;15(2):347-358.

3. Fuller GN, Guiloff RJ. Migrainous olfactory hallucinations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50(12):1688-1690.

4. Chang BS, Lowenstein DH. Mechanisms of disease: epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(13):1257-1266.

5. Lansberg MG, Bluhmki E, Thijs VN. Efficacy and safety of tissue plasminogen activator 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke: a metaanalysis. Stroke. 2009;40(7):2438-2441.

6. Hoffman JL. Intracranial neoplasms: their incidence and mental manifestations. Psychiatr Q. 1937;11(4):561-575.

7. Larson CP. Intracranial tumors in mental hospital patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1940;97(1):49-58.

8. Gupta RK, Kumar R. Benign brain tumours and psychiatric morbidity: a 5-years retrospective data analysis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38(5):316-319.

9. Chambers WR. Neurosurgical conditions masquerading as psychiatric diseases. Am J Psychiatry. 1955;112(5):387-389.

10. Trimble MR, Mendez MF, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric symptoms from the temporolimbic lobes. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9(3):429-438.

11. Uribe VM. Psychiatric symptoms and brain tumor. Am Fam Physician. 1986;34(2):95-98.

12. Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. Computed tomography—an increasing source of radiation exposure. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(2):2277-2284.

13. Berrington de González A, Mahesh M, Kim KP, et al. Projected cancer risks from computed tomographic scans performed in the United States in 2007. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(22):2071-2077.

14. Weinberger DR. Brain disease and psychiatric illness: when should a psychiatrist order a CAT scan? Am J Psychiatry. 1984;141(12):1521-1526.

15. Filley CM, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Neurobehavioral presentations of brain neoplasms. West J Med. 1995;163(1):19-25.

16. Moise D, Madhusoodanan S. Psychiatric symptoms associated with brain tumors: a clinical engima. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(1):28-31.

17. Bunevicius A, Deltuva VP, Deltuviene D, et al. Brain lesions manifesting as psychiatric disorders: eight cases. CNS Spectr. 2008;13(11):950-958.

18. Hollister LE, Boutros N. Clinical use of CT and MR scans in psychiatric patients. J Psychiatr Neurosci. 1991;16(4):194-198.

19. Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):987-996.

20. Brandes AA, Tosoni A, Franceschi E, et al. Glioblastoma in adults. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;67(2):139-152.

21. Chandana SR, Movva S, Arora M, et al. Primary brain tumors in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(10):1423-1430.

22. Madhusoodanan S, Opler MG, Moise D, et al. Brain tumor location and psychiatric symptoms: is there any association? A meta-analysis of published case studies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(10):1529-1536.

Taking an extended leave: What to do before you go

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Arranging coverage and adjusting workload duties before taking an extended leave of absence from clinical practice—eg, for vacation, family leave, medical illness—can be challenging. During extended absences, clinicians depend on colleagues for assistance. In clinical settings such as residency training programs, arranging coverage for a maternity leave could be complicated by differences in attitudes toward pregnancy.1 However, an anticipated leave allows for advanced planning that can help ease transfer of care.

A smooth transition

Begin planning far in advance of your leave date because complications may necessitate a sudden, early departure. All clinical documentation, such as progress notes, should be completed so that a covering colleague can seamlessly assume patient care. It may be helpful to create a spreadsheet of all patients’ information, including name, contact number, diagnoses, medications, and a risk category (eg, low to high), along with notes—eg, lab results that need to be followed up on or labs to be ordered. This spreadsheet can be updated weekly and kept in a secure location so colleagues can access it in case your leave begins earlier than anticipated. To reduce workload burden on covering colleagues, it may be helpful to see as many stable, medication-only patients as possible before you leave to ensure that you have provided enough refills to cover the duration of your leave, assuming these patients typically are seen every other month or less.

It may be helpful to arrange for colleagues to take on a greater proportion of new consultations within the practice as the leave draws closer, because usually this is not a good time to begin treating new patients. However, it may be desirable for you to see a greater proportion of 1-time consultations, such as pre-surgical evaluations and second-opinion consultations. If time allows, arrange meetings among yourself, the colleague who will be covering for you, and high-risk patients before your leave. This can help promote familiarity and comfort between patients and the covering physician and increase the likelihood that patients in crisis will reach out to the covering physician. In some cases it may be advisable to consider a patient’s diagnosis, treatment history, and past experiences when selecting which colleague will provide care, assuming a choice is available—ie, female patients with a history of sexual trauma may feel more comfortable with a female physician.

Although taking an extended leave of absence from clinical practice can present many practical challenges, working with colleagues in advance can help promote a smoother transition of care and decrease workload burden.

Disclosure

Dr. Troy reports no financial, relationship with any company whose, products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing, products.

Reference

1. Tamburrino MB, Evans CL, Campbell NB, et al. Physician pregnancy: male and female colleagues’ attitudes. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1992;47(3):82-84.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Arranging coverage and adjusting workload duties before taking an extended leave of absence from clinical practice—eg, for vacation, family leave, medical illness—can be challenging. During extended absences, clinicians depend on colleagues for assistance. In clinical settings such as residency training programs, arranging coverage for a maternity leave could be complicated by differences in attitudes toward pregnancy.1 However, an anticipated leave allows for advanced planning that can help ease transfer of care.

A smooth transition

Begin planning far in advance of your leave date because complications may necessitate a sudden, early departure. All clinical documentation, such as progress notes, should be completed so that a covering colleague can seamlessly assume patient care. It may be helpful to create a spreadsheet of all patients’ information, including name, contact number, diagnoses, medications, and a risk category (eg, low to high), along with notes—eg, lab results that need to be followed up on or labs to be ordered. This spreadsheet can be updated weekly and kept in a secure location so colleagues can access it in case your leave begins earlier than anticipated. To reduce workload burden on covering colleagues, it may be helpful to see as many stable, medication-only patients as possible before you leave to ensure that you have provided enough refills to cover the duration of your leave, assuming these patients typically are seen every other month or less.

It may be helpful to arrange for colleagues to take on a greater proportion of new consultations within the practice as the leave draws closer, because usually this is not a good time to begin treating new patients. However, it may be desirable for you to see a greater proportion of 1-time consultations, such as pre-surgical evaluations and second-opinion consultations. If time allows, arrange meetings among yourself, the colleague who will be covering for you, and high-risk patients before your leave. This can help promote familiarity and comfort between patients and the covering physician and increase the likelihood that patients in crisis will reach out to the covering physician. In some cases it may be advisable to consider a patient’s diagnosis, treatment history, and past experiences when selecting which colleague will provide care, assuming a choice is available—ie, female patients with a history of sexual trauma may feel more comfortable with a female physician.

Although taking an extended leave of absence from clinical practice can present many practical challenges, working with colleagues in advance can help promote a smoother transition of care and decrease workload burden.

Disclosure

Dr. Troy reports no financial, relationship with any company whose, products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing, products.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Arranging coverage and adjusting workload duties before taking an extended leave of absence from clinical practice—eg, for vacation, family leave, medical illness—can be challenging. During extended absences, clinicians depend on colleagues for assistance. In clinical settings such as residency training programs, arranging coverage for a maternity leave could be complicated by differences in attitudes toward pregnancy.1 However, an anticipated leave allows for advanced planning that can help ease transfer of care.

A smooth transition

Begin planning far in advance of your leave date because complications may necessitate a sudden, early departure. All clinical documentation, such as progress notes, should be completed so that a covering colleague can seamlessly assume patient care. It may be helpful to create a spreadsheet of all patients’ information, including name, contact number, diagnoses, medications, and a risk category (eg, low to high), along with notes—eg, lab results that need to be followed up on or labs to be ordered. This spreadsheet can be updated weekly and kept in a secure location so colleagues can access it in case your leave begins earlier than anticipated. To reduce workload burden on covering colleagues, it may be helpful to see as many stable, medication-only patients as possible before you leave to ensure that you have provided enough refills to cover the duration of your leave, assuming these patients typically are seen every other month or less.

It may be helpful to arrange for colleagues to take on a greater proportion of new consultations within the practice as the leave draws closer, because usually this is not a good time to begin treating new patients. However, it may be desirable for you to see a greater proportion of 1-time consultations, such as pre-surgical evaluations and second-opinion consultations. If time allows, arrange meetings among yourself, the colleague who will be covering for you, and high-risk patients before your leave. This can help promote familiarity and comfort between patients and the covering physician and increase the likelihood that patients in crisis will reach out to the covering physician. In some cases it may be advisable to consider a patient’s diagnosis, treatment history, and past experiences when selecting which colleague will provide care, assuming a choice is available—ie, female patients with a history of sexual trauma may feel more comfortable with a female physician.

Although taking an extended leave of absence from clinical practice can present many practical challenges, working with colleagues in advance can help promote a smoother transition of care and decrease workload burden.

Disclosure

Dr. Troy reports no financial, relationship with any company whose, products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing, products.

Reference

1. Tamburrino MB, Evans CL, Campbell NB, et al. Physician pregnancy: male and female colleagues’ attitudes. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1992;47(3):82-84.

Reference

1. Tamburrino MB, Evans CL, Campbell NB, et al. Physician pregnancy: male and female colleagues’ attitudes. J Am Med Womens Assoc. 1992;47(3):82-84.

Vitamin D deficiency in older adults

Low vitamin D levels can impact cognitive functioning in older adults.1 As vitamin D levels decrease, cognitive impairment increases.

Vitamin D deficiency can occur because few foods contain this nutrient2 and patients have limited exposure to sunlight—vitamin D is produced when sunlight strikes the skin.2 In addition to rickets, low levels of vitamin D have been linked to slower information processing in middle age and older men, cognitive decline, mood disorders, and altered brain development and function resulting in neurodegenerative diseases and other medical disorders.3

One study suggested that one-half of adults age >60 do not get sufficient vitamin D, with an even higher rate among women with Alzheimer’s disease.4 Patients in dementia units typically are not tested for vitamin D levels. These patients rarely leave the unit, which leaves them deprived of the vitamin D provided by sunlight. Even patients exposed to sunlight may receive minimal vitamin D because they use sunscreen.

The following protocol can help patients who may benefit from vitamin D supplementation and increased sun exposure.

Obtain and assess vitamin D levels. Evaluate your patient’s level in the context of physical or cognitive symptoms and other lab values:

- deficient: <12 ng/mL

- inadequate: 12 to 20 ng/mL

- adequate: ≥20 ng/mL.2

Order dietary assessment to identify foods that may increase vitamin D levels. The best sources are fish—salmon, tuna, and mackerel—fish oils, beef, liver, cheese, and egg yolks.2 Several food products, including milk and orange juice, are fortified with vitamin D.

Suggest a daily vitamin D supplement ranging from 400 IU/d to 1,000 IU/d. The Institute of Medicine suggests 600 IU/d for patients age 60 to 70 and 800 IU/d for those age ≥71. For vitamin D deficient patients, recommend >1,000 IU/d.1

Recommend 15 minutes per day in the sun without sunscreen from spring to autumn; late summer to fall is ideal because vitamin D’s half-life is 30 days. Midday is the best time to produce vitamin D.5

Recheck the patient’s Mini-Mental State Examination score every 4 months. Vitamin D supplementation is correlated with cognitive functioning.6

Disclosure

Dr. LaFerney reports no financial, relationship with any company whose, products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing, products.

1. Mayo Clinic. Vitamin D. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/vitamin-d/NS_patient-vitamind/DSECTION=dosing. Updated October 1 2011. Accessed September 26, 2012.

2. National Institutes of Health. Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary supplement fact sheet: vitamin D. http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional. Accessed September 26, 2012.

3. Lee DM, Tajar A, Ulubaev A, et al. Association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and cognitive performance in middle-aged and older European men. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(7):722-729.

4. Wilkins CH, Sheline YI, Roe CM, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low mood and worse cognitive performance in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(12):1032-1040.

5. Webb AR, Engelsen O. Calculated ultraviolet exposure levels for a healthy vitamin D status. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82(6):1697-1703.

6. Przybelski RJ, Binkley NC. Is vitamin D important for preserving cognition? A positive correlation of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration with cognitive function. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460(2):202-205.

Low vitamin D levels can impact cognitive functioning in older adults.1 As vitamin D levels decrease, cognitive impairment increases.

Vitamin D deficiency can occur because few foods contain this nutrient2 and patients have limited exposure to sunlight—vitamin D is produced when sunlight strikes the skin.2 In addition to rickets, low levels of vitamin D have been linked to slower information processing in middle age and older men, cognitive decline, mood disorders, and altered brain development and function resulting in neurodegenerative diseases and other medical disorders.3

One study suggested that one-half of adults age >60 do not get sufficient vitamin D, with an even higher rate among women with Alzheimer’s disease.4 Patients in dementia units typically are not tested for vitamin D levels. These patients rarely leave the unit, which leaves them deprived of the vitamin D provided by sunlight. Even patients exposed to sunlight may receive minimal vitamin D because they use sunscreen.

The following protocol can help patients who may benefit from vitamin D supplementation and increased sun exposure.

Obtain and assess vitamin D levels. Evaluate your patient’s level in the context of physical or cognitive symptoms and other lab values:

- deficient: <12 ng/mL

- inadequate: 12 to 20 ng/mL

- adequate: ≥20 ng/mL.2

Order dietary assessment to identify foods that may increase vitamin D levels. The best sources are fish—salmon, tuna, and mackerel—fish oils, beef, liver, cheese, and egg yolks.2 Several food products, including milk and orange juice, are fortified with vitamin D.

Suggest a daily vitamin D supplement ranging from 400 IU/d to 1,000 IU/d. The Institute of Medicine suggests 600 IU/d for patients age 60 to 70 and 800 IU/d for those age ≥71. For vitamin D deficient patients, recommend >1,000 IU/d.1

Recommend 15 minutes per day in the sun without sunscreen from spring to autumn; late summer to fall is ideal because vitamin D’s half-life is 30 days. Midday is the best time to produce vitamin D.5

Recheck the patient’s Mini-Mental State Examination score every 4 months. Vitamin D supplementation is correlated with cognitive functioning.6

Disclosure

Dr. LaFerney reports no financial, relationship with any company whose, products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing, products.

Low vitamin D levels can impact cognitive functioning in older adults.1 As vitamin D levels decrease, cognitive impairment increases.

Vitamin D deficiency can occur because few foods contain this nutrient2 and patients have limited exposure to sunlight—vitamin D is produced when sunlight strikes the skin.2 In addition to rickets, low levels of vitamin D have been linked to slower information processing in middle age and older men, cognitive decline, mood disorders, and altered brain development and function resulting in neurodegenerative diseases and other medical disorders.3

One study suggested that one-half of adults age >60 do not get sufficient vitamin D, with an even higher rate among women with Alzheimer’s disease.4 Patients in dementia units typically are not tested for vitamin D levels. These patients rarely leave the unit, which leaves them deprived of the vitamin D provided by sunlight. Even patients exposed to sunlight may receive minimal vitamin D because they use sunscreen.

The following protocol can help patients who may benefit from vitamin D supplementation and increased sun exposure.

Obtain and assess vitamin D levels. Evaluate your patient’s level in the context of physical or cognitive symptoms and other lab values:

- deficient: <12 ng/mL

- inadequate: 12 to 20 ng/mL

- adequate: ≥20 ng/mL.2

Order dietary assessment to identify foods that may increase vitamin D levels. The best sources are fish—salmon, tuna, and mackerel—fish oils, beef, liver, cheese, and egg yolks.2 Several food products, including milk and orange juice, are fortified with vitamin D.

Suggest a daily vitamin D supplement ranging from 400 IU/d to 1,000 IU/d. The Institute of Medicine suggests 600 IU/d for patients age 60 to 70 and 800 IU/d for those age ≥71. For vitamin D deficient patients, recommend >1,000 IU/d.1

Recommend 15 minutes per day in the sun without sunscreen from spring to autumn; late summer to fall is ideal because vitamin D’s half-life is 30 days. Midday is the best time to produce vitamin D.5

Recheck the patient’s Mini-Mental State Examination score every 4 months. Vitamin D supplementation is correlated with cognitive functioning.6

Disclosure

Dr. LaFerney reports no financial, relationship with any company whose, products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing, products.

1. Mayo Clinic. Vitamin D. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/vitamin-d/NS_patient-vitamind/DSECTION=dosing. Updated October 1 2011. Accessed September 26, 2012.

2. National Institutes of Health. Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary supplement fact sheet: vitamin D. http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional. Accessed September 26, 2012.

3. Lee DM, Tajar A, Ulubaev A, et al. Association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and cognitive performance in middle-aged and older European men. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(7):722-729.

4. Wilkins CH, Sheline YI, Roe CM, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low mood and worse cognitive performance in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(12):1032-1040.

5. Webb AR, Engelsen O. Calculated ultraviolet exposure levels for a healthy vitamin D status. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82(6):1697-1703.

6. Przybelski RJ, Binkley NC. Is vitamin D important for preserving cognition? A positive correlation of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration with cognitive function. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460(2):202-205.

1. Mayo Clinic. Vitamin D. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/vitamin-d/NS_patient-vitamind/DSECTION=dosing. Updated October 1 2011. Accessed September 26, 2012.

2. National Institutes of Health. Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary supplement fact sheet: vitamin D. http://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional. Accessed September 26, 2012.

3. Lee DM, Tajar A, Ulubaev A, et al. Association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and cognitive performance in middle-aged and older European men. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(7):722-729.

4. Wilkins CH, Sheline YI, Roe CM, et al. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low mood and worse cognitive performance in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(12):1032-1040.

5. Webb AR, Engelsen O. Calculated ultraviolet exposure levels for a healthy vitamin D status. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82(6):1697-1703.

6. Przybelski RJ, Binkley NC. Is vitamin D important for preserving cognition? A positive correlation of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration with cognitive function. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460(2):202-205.

Omega-3s for BPD

As a psychiatrist who incorporates diet and dietary supplements in my practice, I appreciated the excellent review of omega-3 fatty acids for psychiatric illness (Current Psychiatry, September 2012, p. 40-45; http://bit.ly/1ApTrXC). It’s far better to support normal biochemistry and avoid side effects whenever possible.

However, regarding treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD), the author stated that omega-3 fatty acids are ineffective. I have found them clinically useful for BPD. In the 2003 study the author cited, Zanarini et al1 concluded “E-EPA [ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid] is a nutriceutical agent that is both well tolerated and may be efficacious for the treatment of moderately disturbed women with borderline personality disorder. Ninety percent of those taking this compound were able to complete the entire 8-week trial and reported no clinically relevant side effects. Those treated with this compound also experienced a significantly greater reduction in their overall aggression as well as their depressive symptoms than those treated with placebo.” These results suggest that omega-3 fatty acids may be an effective monotherapy for women with moderately severe BPD.

Hyla Cass, MD

Private Practice

Pacific Palisades, CA

The author responds

Dr. Cass is correct. Zanarini et al did suggest that omega-3 fatty acids are beneficial in reducing aggression and depressive symptoms in women with moderate borderline personality disorder who were not prescribed other psychotropics. However, the study was small (N = 30), and further research is needed to support these findings.

Mary Morreale, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry

Wayne State University

Detroit, MI

As a psychiatrist who incorporates diet and dietary supplements in my practice, I appreciated the excellent review of omega-3 fatty acids for psychiatric illness (Current Psychiatry, September 2012, p. 40-45; http://bit.ly/1ApTrXC). It’s far better to support normal biochemistry and avoid side effects whenever possible.

However, regarding treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD), the author stated that omega-3 fatty acids are ineffective. I have found them clinically useful for BPD. In the 2003 study the author cited, Zanarini et al1 concluded “E-EPA [ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid] is a nutriceutical agent that is both well tolerated and may be efficacious for the treatment of moderately disturbed women with borderline personality disorder. Ninety percent of those taking this compound were able to complete the entire 8-week trial and reported no clinically relevant side effects. Those treated with this compound also experienced a significantly greater reduction in their overall aggression as well as their depressive symptoms than those treated with placebo.” These results suggest that omega-3 fatty acids may be an effective monotherapy for women with moderately severe BPD.

Hyla Cass, MD

Private Practice

Pacific Palisades, CA

The author responds

Dr. Cass is correct. Zanarini et al did suggest that omega-3 fatty acids are beneficial in reducing aggression and depressive symptoms in women with moderate borderline personality disorder who were not prescribed other psychotropics. However, the study was small (N = 30), and further research is needed to support these findings.

Mary Morreale, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry

Wayne State University

Detroit, MI

As a psychiatrist who incorporates diet and dietary supplements in my practice, I appreciated the excellent review of omega-3 fatty acids for psychiatric illness (Current Psychiatry, September 2012, p. 40-45; http://bit.ly/1ApTrXC). It’s far better to support normal biochemistry and avoid side effects whenever possible.

However, regarding treatment of borderline personality disorder (BPD), the author stated that omega-3 fatty acids are ineffective. I have found them clinically useful for BPD. In the 2003 study the author cited, Zanarini et al1 concluded “E-EPA [ethyl-eicosapentaenoic acid] is a nutriceutical agent that is both well tolerated and may be efficacious for the treatment of moderately disturbed women with borderline personality disorder. Ninety percent of those taking this compound were able to complete the entire 8-week trial and reported no clinically relevant side effects. Those treated with this compound also experienced a significantly greater reduction in their overall aggression as well as their depressive symptoms than those treated with placebo.” These results suggest that omega-3 fatty acids may be an effective monotherapy for women with moderately severe BPD.

Hyla Cass, MD

Private Practice

Pacific Palisades, CA

The author responds

Dr. Cass is correct. Zanarini et al did suggest that omega-3 fatty acids are beneficial in reducing aggression and depressive symptoms in women with moderate borderline personality disorder who were not prescribed other psychotropics. However, the study was small (N = 30), and further research is needed to support these findings.

Mary Morreale, MD

Assistant Professor

Department of Psychiatry

Wayne State University

Detroit, MI

Psychiatry’s ‘swords of Damocles’

Beneath the current haze of the election buzz, a national anticipatory panic is building up because of the looming “fiscal cliff,” when massive government budget cuts are expected to have grave ramifications and bleak economic and existential repercussions.

Individuals from all political affiliations are frantically demanding that lawmakers do something to avoid a disastrous plunge into chaos for government institutions.

Paradoxically and inexplicably, nothing is being done so far to circumvent this impending doom scenario. A sword of Damocles is hanging over the nation, held, as the legend goes, at the pommel by a single hair of a horse’s tail!

I often feel that’s also what is happening in psychiatry. We are facing not 1, but multiple serious and disruptive challenges, crises, and threats to our profession and our patients. It evokes a grim image of multiple Damocles’ swords hanging over us. We do not seem to be doing anything tangible to avoid these dangerous and injurious swords. I quietly fear that living in imminent danger has become the “new normal” for psychiatry. That’s actually a euphemism for “massive denial.” We all seem to be going on with our lives as if we are not heading to our own version of a “fiscal cliff.” The apathy, inaction, and lack of a sense of urgency by “organized psychiatry” are astonishing, given the critical need for urgent action.

Consider the following swords of Damocles hanging over psychiatry:

- Down-to-the-bone budget cuts in public psychiatry with inadequate resources in community mental health and public hospitals.

- Severe bed shortages: psychiatry has dropped from the most overbedded medical specialty in the 1960s to the most underbedded one, with devastating adverse effects on acutely ill patients who need inpatient treatment.

- Unabating incarceration and criminalization of seriously mentally ill patients as a substitute for hospitalization or care at residential facilities.

- A chronic shortage of psychiatrists, which is fueling the argument by some mental health professions with no medical or advanced nursing background that they should be permitted to “acquire” prescription privileges, as if prescribing is a skill independent from the extensive training of 4 years of medical school plus 4 years of psychiatric training. The consequences for disabled patients will be low-quality, even dangerous care.

- The low rate of medical students choosing psychiatry as a career. The shortage of psychiatrists will worsen if attrition from retirement or mortality is not offset by substantial annual infusions of newly minted psychiatrists.

- The deplorably short life span of patients with severe mental illness—25 years less than non-mentally ill individuals—mainly attributable to excess cardiovascular risk and lack of access to adequate primary care as part of community mental health management.

- An anemic pipeline of psychiatric residents choosing careers as teachers or researchers. Huge student loans and lack of mentorship are only some of the reasons residents select clinical work over academic careers.

- Withdrawal of several major pharmaceutical companies from research and development to discover new psychiatric drugs. It would be more judicious to engage and partner with them instead of demonizing them simply because they are the only entities that design, develop, test, and produce psychiatric medications. The unmet needs in psychiatry are enormous, especially because 80% of DSM-IV-TR psychiatric disorders have no FDA-approved medication.

- A lack of coalescence and cohesiveness of psychiatrists in the United States. We have fragmented into small organizations and factions, speaking with several faint voices instead of one powerful voice. Other disciplines are far better organized and can lobby more effectively for their causes.

- A lack of participation by psychiatrists in their professional organizations and low support for political action committees to navigate the agenda of psychiatry at the local, state, and national levels. The image and influence of psychiatry can be bolstered only by ongoing member donations and the reverse will occur without consistent member support.

- The persistent stigma of mental illness that continues to haunt our patients, inhibits treatment-seeking, and undermines treatment adherence. Despite magnificent advances in the medical basis of mental disorders, psychiatric illnesses are not regarded with the same acceptance and understanding as other medical disorders.

- A frustrating lag in translating the veritable explosion in basic neuroscience discoveries into clinical applications for diagnosis or therapeutics. Psychiatry could benefit greatly if a sufficient number of well-funded translational researchers get involved. A partnership between the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)and the pharmaceutical industry can expedite this translation, but has yet to happen.

This list of “dangling swords” may appear daunting and overwhelming but if we shed our apathy and unite, we can parry their threats and emerge stronger. I do not claim to have the answers but I do have an abiding faith in the collective wisdom and abilities of my fellow psychiatrists, if they decide to mobilize. The root of our “fiscal cliff” is our chronic inaction, passivity, and lack of cohesiveness and a passionate pursuit of our shared goals. We better wake up and act soon before these Damocles’ swords start falling and inflicting their exquisite pain.

Beneath the current haze of the election buzz, a national anticipatory panic is building up because of the looming “fiscal cliff,” when massive government budget cuts are expected to have grave ramifications and bleak economic and existential repercussions.

Individuals from all political affiliations are frantically demanding that lawmakers do something to avoid a disastrous plunge into chaos for government institutions.

Paradoxically and inexplicably, nothing is being done so far to circumvent this impending doom scenario. A sword of Damocles is hanging over the nation, held, as the legend goes, at the pommel by a single hair of a horse’s tail!

I often feel that’s also what is happening in psychiatry. We are facing not 1, but multiple serious and disruptive challenges, crises, and threats to our profession and our patients. It evokes a grim image of multiple Damocles’ swords hanging over us. We do not seem to be doing anything tangible to avoid these dangerous and injurious swords. I quietly fear that living in imminent danger has become the “new normal” for psychiatry. That’s actually a euphemism for “massive denial.” We all seem to be going on with our lives as if we are not heading to our own version of a “fiscal cliff.” The apathy, inaction, and lack of a sense of urgency by “organized psychiatry” are astonishing, given the critical need for urgent action.

Consider the following swords of Damocles hanging over psychiatry:

- Down-to-the-bone budget cuts in public psychiatry with inadequate resources in community mental health and public hospitals.

- Severe bed shortages: psychiatry has dropped from the most overbedded medical specialty in the 1960s to the most underbedded one, with devastating adverse effects on acutely ill patients who need inpatient treatment.